Abstract

Purpose

PI3K-pathway activation occurs in concomitance with RAS/BRAF mutations in colorectal cancer (CRC) limiting the sensitivity to targeted therapies. Several clinical studies are being conducted to test the tolerability and clinical activity of dual MEK and PI3K-pathway blockade in solid tumors.

Experimental design

In the present study we explored the efficacy of dual pathway blockade in CRC preclinical models harboring concomitant activation of the ERK- and PI3K-pathways. Moreover, we investigated if TP53 mutation impacts the response to this therapy.

Results

Dual MEK and mTORC1/2 blockade resulted in synergistic antiproliferative effects in cell lines bearing alterations in KRAS/BRAF and PIK3CA/PTEN. Although the on-treatment cell cycle effects were not impacted by the TP53 status, a marked proapoptotic response to therapy was observed exclusively in wild-type TP53 CRC models. We further interrogated two independent panels of KRAS/BRAF- and PIK3CA/PTEN-altered cell line- and patient-derived tumor xenografts for the antitumor response towards this combination of agents. A combination-response that resulted in substantial antitumor activity was exclusively observed among the wild-type TP53-models (two out of five, 40%), while there was no such response across the eight mutant TP53 models (0%). Interestingly, within a cohort of fourteen CRC patients treated with these agents for their metastatic disease, two patients with long-lasting responses (32 weeks) had TP53 wild-type tumors.

Conclusions

Our data supports that in wild-type TP53-CRC cells with ERK- and PI3K-pathway alterations MEK-blockade results in potent p21-induction preventing apoptosis to occur. In turn, mTORC1/2 inhibition blocks MEK-inhibitor-mediated p21-induction, unleashing apoptosis.

Keywords: combinatorial therapy, drug resistance, patient-derived tumor xenografts

INTRODUCTION

Metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Currently, the standard of care for metastatic CRC is chemotherapy (fluoropyrimidin and oxaliplatin/irinotecan combinations). Target-specific agents against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) -cetuximab and panitumumab-, or against the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-pathway -bevacizumab and aflibercept- as well as the multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor regorafenib are also approved for the treatment of metastatic CRC (1–3). However, the efficacy of anti-EGFR compounds is often limited by mutations that activate downstream signaling pathways, rendering targeted therapy ineffective (4–6).

The landscape of somatic mutations in colorectal cancer has been defined during the last years (7). According to The Cancer Genome Atlas Network (8), 42% of primary CRC display activating mutations of the KRAS oncogene, 10% in BRAF and an additional 10% in NRAS, being typically mutually exclusive mutations. Mutations in this pathway result in hyperactivation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 (MAP2K1 or MEK1) and the downstream mitogen-activated protein kinases p42/p44 (p42/p44 MAPK or ERKs) (9). Activation of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) pathway occurs in 22% of all the primary CRC either as PIK3CA mutations (the coding gene for the catalytic subunit of PI3K, p110α) or by mutation/homozygous deletion of the phosphatase and tensin homolog PTEN (encoding for the phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate 3-phosphatase) (8), resulting in activation of downstream targets such as Akt and mTOR. As a whole, mutations in RAS/BRAF and in PIK3CA/PTEN frequently coexist, resulting in activation of both cascades (10). Activating mutations in both pathways confer resistance to EGFR-targeting therapies (5, 11–13), providing a rationale for dual MEK and PI3K-pathway blockade in metastatic CRC. Mutations in TP53, the gene encoding for p53, are frequent within the CRC tumors bearing mutations in the ERK- and PI3K-pathways, accounting for 46% of this subset (8).

Combined inhibition of the MEK- and PI3K/Akt/mTOR-pathways has been preclinically tested in a variety of cancer models, such as lung (14), pancreatic (15), breast (16, 17) and colorectal cancer (18). The tolerability and preliminary efficacy of anti-MEK and anti-PI3K/Akt/mTOR complex 1/2 (mTORC1/2) therapy is being evaluated in several clinical trials, including patients with advanced CRC (19, 20). The overlapping/synergistic toxicities observed by dual targeting have hampered achieving full-maximal tolerated doses of the respective single-agents, therefore compromising pathway blockade (19, 21, 22). As a consequence, there is a need to identify which patients are more likely to benefit from these regimens, and to improve the therapeutic schedules to maximize exposure reducing side effects. In the present study, we elucidate the impact of TP53 mutation on the antitumor activity of combined MEK- and PI3K/mTORC1/2-inhibition in CRCs harboring concomitant mutations in both signaling pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents

All the CRC cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA), with the exception of LIM2405, which was obtained from the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (Switzerland). All cell lines were authenticated using DNA profiling by the ATCC/Ludwig archive. DLD-1 was maintained in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen, NY, USA), HT-29 and HCT116 in McCoy's 5A Medium Modified (Invitrogen), and SW948, RKO and LIM2405 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) all of them supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2mM L-glutamine (Life Technologies, Inc. Ltd, Paisley, UK) at 37 °C in 5% CO2. PD0325901 and MLN0128 were obtained from Takeda California (San Diego, CA). General laboratory supplies were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA), Invitrogen or Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

Western blots

Cells were grown in 60 mm dishes and treated with PD-0325901 (referred to as PD-901), MLN0128 (formerly known as INK-128) or a combination of both for the indicated concentrations and times. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and scraped into ice-cold lysis buffer (TRIS-HCl pH 7.8 20 mM, NaCl 137mM, EDTA pH 8.0 2mM, NP40 1%, glycerol 10%, supplemented with NaF 10 mM, Leupeptin 10μg/mL, Na2VO4 200 μmol/L, PMSF 5mM and Aprotinin (Sigma-Aldrich)). Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and supernatants removed and assayed for protein concentration using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, IL, USA). Thirty micrograms of total lysate was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were then hybridized using the following primary antibodies: pAkt (S473), Akt, pS6 (S240/244), pS6 (S235/236), p4EBP1 (S65), 4EBP1, pERK (T202/Y204), ERK, cleaved PARP, PARP, cleaved caspase 7 and p53 (Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA), tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), c-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), p21 (Neomarkers, ThermoFisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA) in 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) + 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma Aldrich) and GAPDH (Cell Signaling) in 1% nonfat dry milk in TBST. Mouse and rabbit horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences, NJ, USA) were used at 1:2000 in TBS-T 1% nonfat dry milk. Protein-antibody complexes were detected by chemiluminescence with the Immobilon Western HRP Substrate (Millipore, MA, USA) and images were captured with a FUJIFILM LASS-3000 camera system.

Determination of inhibitory concentration 50 and combination index

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with 1:10 serial dilutions of PD-901 and MLN0128 within the 10 uM-1pM range) as single agents or in 1:1 combinations. After 4 days of treatment, cell proliferation was analyzed with CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, WI, USA) as described by the manufacturer. Proliferation curves were calculated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, CA, USA) and the combination index (CI) was determined using CompuSyn (ComboSyn Inc., NJ, USA) (23). CI < 1 indicates synergism, CI = 1 indicates additive effect and CI > 1 indicates antagonism. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Determination of cell cycle and apoptosis

Cell cycle and hypodiploid (sub-G1) cells were quantified by flow cytometry. Briefly, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in cold 70% ethanol, and then stained with propidium iodide while treating with RNase (Sigma-Aldrich). Quantitative analysis of sub-G1 cells was carried out in a FACScalibur cytometer using the Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences, NJ, USA). Annexin V positive cells were quantified using the Guava Nexin Reagent (Millipore) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, cells were harvested in 1% BSA/PBS and diluted 1:1 in the Guava Nexin Reagent. After 20 minutes at room temperature, cells were analyzed in the Guava System (Millipore).

RNA extraction and quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted using the PerfectPure RNA Tissue kit (5Prime, Hamburg Germany), according to manufacturer's instructions. QRT-PCR was performed using TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Reactions were carried out in an ABI7000 sequence detector (Perkin Elmer, MA, USA) and results were expressed as fold change calculated by the ΔCt method relative to the control sample. The β-glucuronidase gene GUSB mRNA was used as internal normalization control.

Overexpression of p53-R248W, p21 and RNA interference

p53-R248W was synthesized and cloned into a pBABE backbone vector (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ). The pINDUCER20-HA-p21Cip1 plasmid was kindly provided by Stephen J. Elledge (24). siRNAs against p21 and non-targeting siRNAs control were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich. Cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs at 50 nM during 24h using DharmaFECT1 transfection agent (Dharmacon Research, CO, USA) as described by the manufacturer. The shTP53 construct was obtained from The RNAi Consortium (Broad Institute, MA, USA).

Establishment of cell line derived tumor xenografts in nude mice

Mice were maintained and treated in accordance with institutional guidelines of Vall d'Hebron University Hospital Care and Use Committee. Six week old female athymic nude HsdCpb:NMRI-Foxn1nu mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Italy). Mice were housed in air-filtered laminar flow cabinets with a 12-h light cycle and food and water ad libitum. HT-29, HCT116 or LIM2405 cells were resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before subcutaneous injection at a final concentration of 2 × 106 cells / 100 μL per mouse.

Establishment of human colorectal cancer patient-derived tumor xenografts (CRC-patient-derived xenografts (PDXs))

Human colon carcinoma models were used and grown as described by Puig et al (25). Experiments were conducted following the European Union's animal care directive (86/609/EEC) and were approved by the Ethical Committee of Animal Experimentation of the Vall d'Hebron Research Institute and patient consent. PDX models from passage 5 to 8 were established by implantation of enzymatically digested surgical colon cancer biopsies in NOD-SCID mice (NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/NcrCrl). PDXs recapitulated the same histopathological and genetic features as the original patients' carcinomas. For drug efficacy studies, a total of 1 × 105 patient-derived tumor cells was obtained from an established tumor, suspended in PBS 1:1 with Matrigel (BD Bioscience) and injected subcutaneously into both flanks of NOD-SCID mice as described (26, 27). After 3 to 8 weeks, when palpable tumors matched 200 ± 50 mm3 treatments started and tumor size was evaluated twice weekly by caliper measurements.

PDXs from the Candiolo Cancer Institute (18) were established following procedures approved by the local Ethical Commission and by the Italian Ministry of Health. Briefly, 25mm3 matrigel-coated tumor material derived from liver metastectomies were implanted in the flank of NOD/SCID mice, as described (18). For treatment efficacy experiments, established tumors (~400mm3) were treated with 40mg/kg BEZ235 (Selleck Chemicals) or 25mg/kg AZD6244 (Sequoia Research Products). Tumor size was evaluated once weekly by caliper measurements.

In vivo treatment study

Animals were divided into 4 groups, consisting of 6-10 mice per group. Animals were treated with PD901 6QD/week (2 mg/kg in 5% NMP, 95% PEG in water, oral gavage) and/or MLN0128 6QD/week (0.3 mg/kg in 5% NMP, 15% PVP in water, oral gavage). Tumors were measured with digital calipers and tumor volumes were determined using the formula: (length × width2) × (π/6). At the end of the experiment, animals were euthanized using CO2 inhalation. Tumor volumes are plotted as mean ± SE of 6-10 mice. For western blotting, whole protein lysates from two-to-four different tumors derived from each treatment were processed as described above.

Patient selection and genotyping of tumor samples

All patients with pathologically confirmed metastatic CRC refractory to standard therapy referred to phase I clinical trials at the Molecular Therapeutic Research Unit of Vall d' Hebron Institute of Oncology had archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples analyzed for targeted molecular aberrations KRAS/NRAS/BRAF/PIK3CA mutations were identified using the TheraScreen® molecular diagnostic assay (DxS) or the OncoCarta Panel v1.0 Sequenom MassARRAY, by the Pathology Service from the Vall d'Hebron University Hospital or the Cancer Genomics Group at VHIO, respectively. For three patients KRAS was sequenced at the hospital of origin using the commercial PCR kit (DxS). PTEN expression by immunohistochemistry was determined by the Molecular Oncology Group at VHIO. The three laboratories are UNE-ISO 15189 accredited (28). Patient's informed consent was obtained at baseline. In total, from 2011 until 2013, fourteen patients with double pathway aberrations participated in early clinical trials with MEK-plus PI3K-pathway inhibitors based on the results of tumor profiling as well as logistic factors, including study availability and eligibility criteria (19). Patients achieved clinical benefit if their cancer was controlled for a minimum time of 16 weeks, time point for the second response evaluation by computerized tomography (28). Tumor specimens from primary CRC or metastasis and from the established PDX were subjected to capture-based massive parallel sequencing (MiSeq, Illumina, San Diego, CA). Briefly, to avoid false negatives, only tumor samples with a tumor area above 30% were analyzed. DNA was extracted from 5 × 10 μm slices using the Maxwell FFPE Tissue LEV DNA Purification Kit (Promega). An initial multiplex-PCR with a proofreading polymerase was performed on samples. An in-house developed panel of over 600 primer pairs targeting frequent mutations in oncogenes plus several tumor suppressors, totaling 57 genes, was applied (Supplementary Table S1 and primer pairs available upon request). The panel includes the entire coding sequence of TP53 (NM_00546). Indexed libraries were pooled and loaded onto a MiSeq instrument and paired-end 100bp-read-length sequencing performed (2×100bp). Initial alignment was performed with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) after primer sequence clipping and variant calling was done with the Genome Analysis Toolkit Unified Genotyper and VarScan2 followed by ANNOVAR annotation. Mutations were called at a minimum 3% allele frequency. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were filtered out with the single nucleotide polymorphism database (dbSNP) (29) and 1000 genome datasets (30). All detected variants were manually inspected.

PDX from the Candiolo Cancer Institute were genotyped as described (18), by capillary electrophoresis (3730 ABI Applied Biosystems) using exon-specific and sequencing primers, which were designed with Primer3 software.

Immunohistochemistry

Xenograft tumors were fixed immediately after excision in 10% buffered formalin solution for a maximum of 24 h at room temperature before being dehydrated and paraffin-embedded under vacuum conditions (FFPE). Tissue micro-arrays (TMA) were constructed including duplicate cores from each tumor. TMA slides underwent deparaffinization and antigen retrieval using PT Link system (DAKO, Denmark) following manufacturer's instructions. Immunohistochemical staining against cleaved caspase 3 or p53 (DAKO) was performed as follows: 4 μm sections from FFPE material were deparaffinized and hydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed using a T/T Mega microwave system following manufacturer's instructions and DAKO reagents. After peroxide blocking, slides were incubated with primary antibody, secondary antibody and developed with freshly prepared 0.05% 30,3-diaminobenzidine and counterstained with hematoxylin. Positive and negative controls were run along with the tested slides per each marker. Images were acquired using Aperio ImageScope software (Aperio, CA, USA) and a pathologist blinded to the identity of the samples quantified the percentage of positively stained cells.

p53 status

We analyzed the p53 status of tumor samples from archival tissue primarily upon the TP53 mutation status (MiSeq). Only when tumor sample was scarce (tumor area <30%) or the coverage of the genomic assay was insufficient we used IHC to provide a surrogate of TP53 mutation. Those tumors that markedly stained for nuclear p53 (≥50% of tumor cell positivity) were considered p53-mutant (31).

Statistical analysis

Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad software, CA, USA). Error bars represent the SE. All experiments were repeated at least three times. A Log-rank test is performed with the clinical data (R software).

RESULTS

Combined MEK and mTORC1/2 inhibition synergistically suppresses colorectal cancer cell proliferation

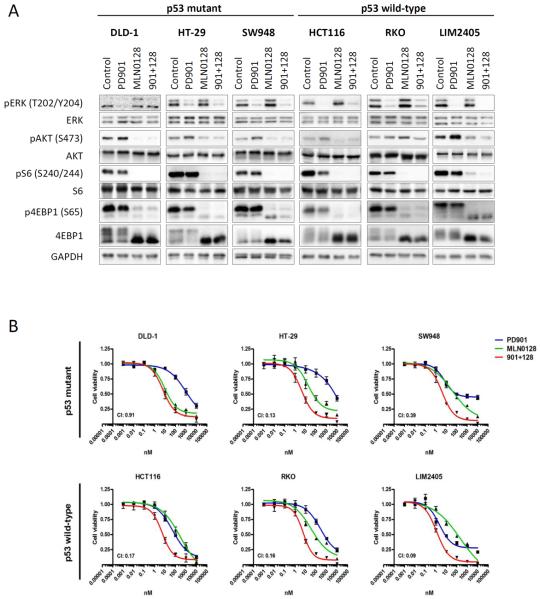

To test the biochemical effects of dual MEK and mTORC1/2 blockade in vitro, we treated six CRC cell lines bearing concomitant alterations in KRAS/BRAF and PIK3CA/PTEN (Supplementary Table S2), three of which were also harboring TP53 mutations, with the MEK inhibitor PD901, the catalytic mTOR inhibitor MLN0128, or the combination of both. After 24 h of treatment, PD901 markedly suppressed ERK phosphorylation (Fig. 1A). Treatment with MLN0128 resulted in a reduction of p-Akt-S473 and downstream mTORC1 targets phospho-S6 ribosomal protein, p-S6-S240/244, and phospho-4E binding protein-1, p-4EBP1-S65, accompanied by minor increases in ERK activation. As expected, the combination of PD901 and MLN0128 suppressed both ERK and PI3K pathways in all the cell lines.

Figure 1. MEK- and mTOR-inhibition suppress pathway activation and proliferation irrespective of p53 mutational status.

A. The indicated CRC cell lines were treated with DMSO (Control), 50 nM PD901, 50 nM MLN0128 or the combination of both inhibitors (901 + 128). Whole-cell protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. ERK antibody was used as loading control. Figures are representative of three independent experiments. B. The indicated CRC cell lines were treated with 1:10 serial dilutions of PD901, MLN0128 or the combination. Proliferation was measured after 4 days of treatment with a cell viability assay (Cell Titer-Glo, Promega). Proliferation curves were graphed using GraphPad Prism software. Combination index (CI) was calculated using CompuSyn computer software (Fa=0.5). Data are expressed as mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments.

The anti-proliferative response of combined PD901 and MLN0128 treatment was synergistic (Combination Index, CI < 1) in five out of six cell lines, irrespective of the TP53-mutational status (Fig. 1B). We next investigated if any cell responses were dependent on the TP53-mutational status.

When examining the cell cycle, we found that the TP53-mutational status did not discriminate the combination response (% of S-phase, Supplementary Fig. S1A). Moreover, cell cycle biomarkers were markedly reduced in all cell cycle-sensitive cell lines, independently of the TP53 mutational status (see Supplementary Fig. S1B, transcription factor E2F1 and the phosphorylation levels of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor, RB). Thus, the presence of a TP53 mutation did not affect the anti-proliferative activity of combined MEK and mTORC1/2 inhibition in colorectal cancer cells harboring activating RAS/BRAF and PI3K-pathway alterations.

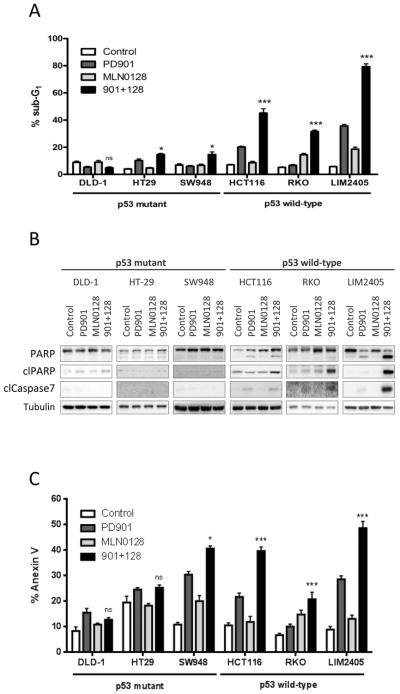

Combined MEK and mTORC1/2 blockade promotes apoptosis in TP53 wild-type but not in TP53 mutant colorectal cancer cell lines via activation of BAX

We next investigated whether combined PD901 and MLN0128 induced apoptosis in our panel of CRC cells. We observed a clear-cut difference in terms of apoptosis induction between CRC cell lines harboring wild-type or mutant TP53. In wild-type TP53 cell lines (HCT116, RKO and LIM2405), PD901 or MLN0128 treatment increased cell death, as measured by sub-G1 DNA accumulation (Fig. 2A). The combination treatment synergistically increased the sub-G1 population in all three models, reaching profound levels of cell death (45%, 32% and 79%, respectively) with concomitant caspase 7 and PARP cleavage (Fig. 2B). In contrast, TP53 mutant cell lines (DLD-1, HT-29 and SW948) showed only minor combination response compared to single agents, achieving relatively limited cell death (5%, 15% and 15%, respectively), with no detectable biochemical read outs of apoptosis. These results were supported by the significantly higher induction of Annexin V in TP53 wild-type vs mutant cells treated with the combination of agents (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. MEK- and mTOR-inhibition induces apoptosis in p53 wild-type CRC cells.

The indicated CRC cell lines were treated with DMSO (Control), 50 nM PD901, 50 nM MLN0128 or the combination of both inhibitors (901 + 128). A. Apoptosis was measured after 72 hours of treatment as the percentage of cells with sub-G1 DNA content by flow cytometry and analyzed with FCS Express 4 Flow software. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E from three independent experiments. B. Whole-cell protein extracts were analyzed after 24 hours of treatment by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Tubulin antibody was used as loading control. Figures are representative of three independent experiments. C. Apoptosis was measured after 72 hours of treatment quantification of the Annexin V positive cells (Guava Nexin Reagent, Millipore). n.s., not significant, *p<0.5, ***p<0.001.

We further studied which p53 targets are involved in the response to dual MEK- and mTORC1/2-blockade. We found that, while the levels of NOXA remained relatively stable across treatments, the levels of PUMA increased in all cell lines upon MEK and/or mTORC1/2 blockade, regardless of the p53 status (Supplementary Figure S1B,C). Interestingly, BAX levels increased following MEK inhibition exclusively in the p53 wild-type cell lines. These results suggest that BAX may be mediating apoptosis in p53 wild-type CRC treated with MEK- and mTORC1/2-inhibitors.

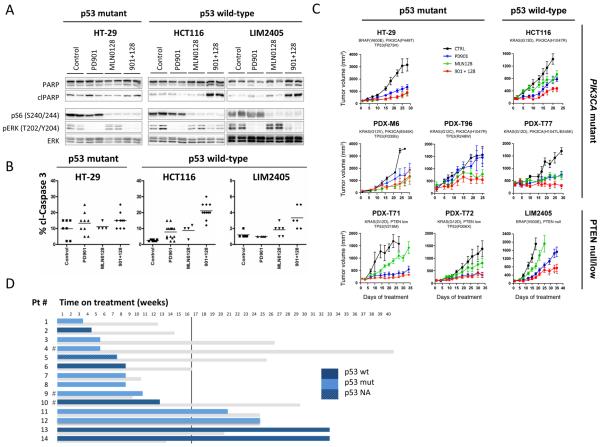

Combined MEK and mTORC1/2 suppression promotes antitumor responses in TP53 wild-type colorectal cancer xenografts

In vivo, xenografts derived from one mutant (HT-29), and two wild-type TP53 (HCC116, LIM2405) CRC cell lines exhibited biochemical ERK or PI3K/mTOR signal inhibition with PD901 and MLN0128, respectively, and inhibition of both pathways when treated with the combination of both agents (Fig. 3A). However, detection of PARP and caspase-3 cleavage was evident only in TP53 wild-type tumors upon combination treatment (Fig. 3A, 3B and Supplementary Fig. S1D). We then expanded our panel of models with five patient-derived tumor xenografts (PDXs) that harbored alterations in KRAS and PIK3CA/PTEN, in addition to the three cell line-derived models. Single agent antitumor activity was variable across the eight CRC models; yet the combination of PD901 and MLN128 resulted in tumor growth stabilization in one out of three TP53 wild-type CRC models (PDX-T77), and in none of the TP53 mutant ones (Fig. 3C). We confirmed our results with an independent sample set (18), namely five CRC PDX models that harbor hotspot mutations in KRAS and PIK3CA, using different MEK and PI3K/mTORC1/2 inhibitors. A combination-response of AZD6244 (MEK inhibitor) plus NVP-BEZ235 (PI3K/mTORC1/2 inhibitor) that resulted in tumor growth stabilization was observed in one of two wild-type TP53-PDX and in none of the three TP53-mutant ones (Supplementary Table S3). Altogether, an anti-tumor combination-response was observed in two out of five (40%) TP53-wild type CRC models, while there was no such response across the eight TP53-mutant models (0%). These data suggests that TP53 mutational status could impact the anti-tumor activity of combined MEK and mTORC1/2 inhibition in CRC.

Figure 3. p53 wild-type CRC tumors benefit from combined MEK- and mTOR- inhibition.

Mice bearing HT-29, HCT116 or LIM2405 tumors were treated with 3 consecutive doses of vehicle control (Control, C), PD901 (901, 2mg/kg, 6QD/W), MLN0128 (128, 0.3 mg/kg, 6QD/W) or the combination of both inhibitors (901+ 128). A. Tumors were collected and analyzed by western blot with the indicated antibodies. B. Tumors were collected and analyzed by immunohistochemistry with cleaved caspase 3 antibody. The images were quantified by a pathologist blinded to the identity of the samples. C. Mice bearing HT-29, HCT116, LIM2405, PDX-M6, PDX-T71, PDX-T72, PDX-T77, PDX-T96 were treated as indicated for 20–60 days. Measurements are displayed as mean ± S.E. D. Time on MEK- plus PI3K-therapy of 14 patients (blue) compared to the time on treatment for the previous chemotherapy-containing regimen (grey). The vertical line stands for the 16-week threshold (second response evaluation by computer tomography). The p53 status (sequencing and IHC) is provided in dark blue for wild-type p53, light blue for mutant p53 and shaded blue for non-available data. #, Patients exiting MEK- plus PI3K-therapeutic regimen because of toxicity.

p53 status in CRC patients treated with MEK plus PI3K/mTORC1/2 therapy

We next investigated whether the p53 status of tumors from CRC patients treated with the combination of MEK- and PI3K/mTORC1/2 could predict for response to therapy (Fig. 3D). Assessment of the p53 status was possible in thirteen cases using DNA sequencing or immunohistochemistry (when the genomic assay failed or when tumor tissue was scarce, Supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Among this cohort, three patients stopped therapy due to toxicity. For the remaining 10 cases we observed no significant correlation between p53 mutations and progression-free survival. This was not surprising given the small number of cases and the overall short time of response to therapy in these heavily pre-treated patients. However, we noticed that the two patients with the longest (32 weeks) responses to dual MEK- and mTORC1/2-blockade had tumors with wild type p53 (Fig. 3D). Intriguingly, the effects of the chemotherapy administered immediately before MEK- plus PI3K/mTORC1/2-inhibitors was not long lasting in these two patients, suggesting that these tumors were not indolent slow growing and/or overall sensitive to cytotoxic therapies. More data on larger cohorts of patients is required to make any conclusions about the value of wild type p53 in predicting response to this therapeutic strategy.

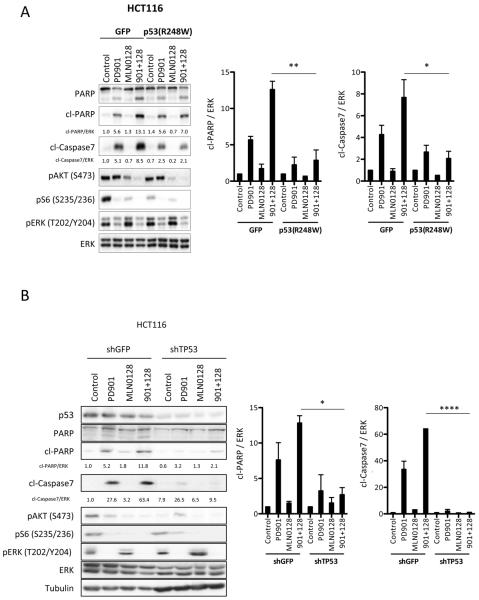

p53 function is necessary for apoptotic and anti-tumor effects of MEK and mTORC1/2 blockade in colorectal cancer cells

Since our results in multiple CRC models supported an association between TP53 mutation status and sensitivity to combined MEK and mTORC1/2 inhibition, we sought to further elucidate the role of p53 as a determinant of therapy response. We stably overexpressed a mutant variant of TP53 (p53-R248W) or GFP (control) in the TP53 wild-type cell lines HCT116 and LIM2405. The p53-R248W mutation has been described as a dominant negative variant that represses p53 transcriptional functions by interacting with the endogenous wild-type p53 (32, 33). Upon treatment, both cell line models exhibited the expected reduction in p-ERK and p-AKT / p-S6 upon PD901 and MLN0128, respectively, both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S3A,B). However, expression of p53-R248W suppressed caspase 3/7 and PARP cleavage induced by combined MEK and mTORC1/2 inhibition (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S3A,B). This resulted in reduced sensitivity to combined PD901 and MLN0128 in p53-R248W xenografts compared to p53 wild-type counterparts (Supplementary Fig. S3C). Similarly, knockdown of TP53 in HCT116 cells resulted in significant attenuation of the proapoptotic response upon combined treatment with PD901 and MLN128 (Fig. 4B). These data support the hypothesis that p53 function is necessary for the induction of apoptosis and anti-tumor response to combined MEK and mTORC1/2 inhibition in CRC.

Figure 4. p53 proficiency is required to induce apoptosis in CRC tumors upon anti MEK- and mTOR-inhibition.

A. Stable GFP or p53(R248W) HCT116 cells were treated with DMSO (Control), 50 nM PD901, 50 nM MLN0128 or both inhibitors (901 + 128) for 24 hours. Whole-cell protein extracts were analyzed with the indicated antibodies. Figures are representative of three independent experiments, and quantified by densitometry (Image J). B. Stable shGFP or shTP53 HCT116 cells were treated with DMSO (Control), 50 nM PD901, 50 nM MLN0128 or both inhibitors (901 + 128) for 24 hours and resolved as in panel 4A. Figures are representative of three independent experiments, and quantified. * p<0.05. **, p<0.01. ****, p<0.0001

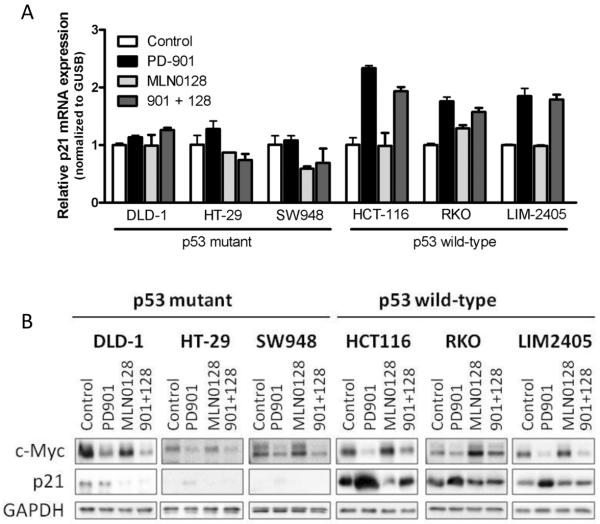

MEK blockade promotes p53-dependent upregulation of p21 in TP53 wild-type colorectal cancer

Given that the cell cycle and apoptosis inhibitor p21 is a downstream target of MEK, mTORC1/2 and p53, we hypothesized that expression of p21 could limit cell death mediated by the combination of PD901 and MLN128 (34, 35) in our preclinical models. As expected, p21 mRNA and protein levels were lower in TP53 mutant cells compared to TP53 wild-type cells (Fig. 5A and 5B and Supplementary Fig. S3D and S3E). Moreover, MEK blockade inhibited the expression of c-Myc and increased p21 mRNA and protein levels preferentially in p53 wild-type cells (HCT116, RKO and LIM2405). This effect was reverted (post-transcriptionally) by mTOR blockade (Fig. 5A and B). These data are in agreement with p21 being negatively regulated by c-Myc, a downstream target of MEK (36), and with mTORC1 regulating p21 stability at the translational level (34). In contrast, p21 mRNA and protein levels remained unaffected in the TP53 mutant models (DLD-1, HT-29 and SW948) treated equally.

Figure 5. MEK-inhibition induces p21 upregulation in p53 proficient CRC cells.

A. CRC cell lines were treated with DMSO (Control), 50 nM PD901, 50 nM MLN0128 or the combination of both for 16 hours. p21 mRNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR, normalized to GUSB mRNA levels and expressed as fold change compared to control. B. CRC cell lines were treated with DMSO (Control), 50 nM PD901, 50 nM MLN0128 or the combination of both for 24 hours and whole-cell protein extracts were analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. GAPDH antibody was used as loading control. Figures are representative of three independent experiments.

To confirm the role of wild-type p53 in p21 modulation, we made use of the HCT116-GFP and HCT116-p53-R248W cell lines described above. In GFP transfected cells, treatment with PD901 resulted in induction of p21. In agreement with the previous data, expression of p53-R248W prevented p21 upregulation consequent to MEK inhibition (Supplementary Fig. S3F). We next confirmed that p21 upregulation upon MEK inhibition was p53 dependent by downregulating p53 in two TP53 wild-type cell lines, HCT116 and LIM2405 (Supplementary Fig. S3G). In both models, p53 knockdown counteracted PD901-induction of p21. In summary, we show that MEK blockade results in increased p21 mRNA and protein expression in TP53 wild-type CRC cells.

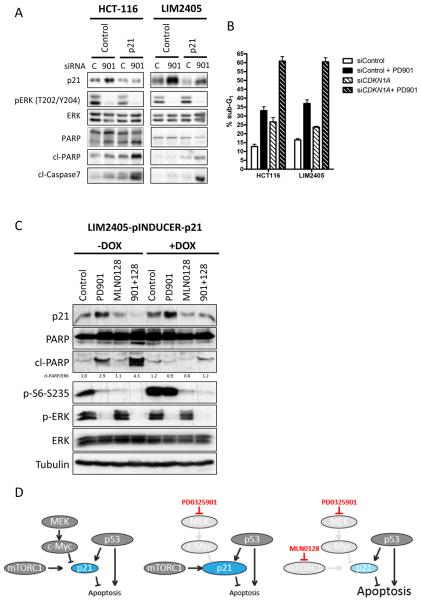

p21 upregulation prevents apoptosis mediated by MEK blockade in TP53 wild-type colorectal cancer cells

Finally, we sought to investigate whether p21 upregulation following treatment with PD901 alone precludes the induction of apoptosis in TP53 wild-type CRC cells. Specific downmodulation of CDKN1A (the gene encoding for p21) in two TP53 wild-type cell lines, HCT116 and LIM2405, resulted in increased induction of apoptosis by PD901, as shown by caspase 7 and PARP cleavage as well as accumulation of the sub-G1 cell fraction (Fig. 6A and 6B). In addition, overexpression of p21 in p53 wild-type cells mimicked the effect of MEK inhibition and prevented PARP cleavage upon the combination of PD901 and MLN0128 treatment (Fig. 6C). In summary, our results show that the apoptotic response following MEK and mTORC1/2 blockade in CRC models is p53-dependent. As a consequence of mTOR blockade, PD901-induced upregulation of p21 is blunted, which likely precipitates apoptosis.

Figure 6. Induction of p21 by MEK-inhibition inhibits apoptosis in p53 wild-type CRC cells.

A. HCT116 and LIM2405 cell lines cells were transfected with either a siRNA oligonucleotide targeting p21 (CDKN1A) or a control siRNA oligonucleotide as described. After 24 hours of treatment with DMSO (C) or 50 nM PD901 (901), whole-cell protein extracts were analyzed with the indicated antibodies. Figures are representative of three independent experiments. B. Apoptosis was measured after 72 hours of treatment as percentage of cells with sub-G1 DNA content by flow cytometry and analyzed with FCS Express 4 Flow software. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E from three independent experiments. C. LIM2405 cell line was stably transfected with an inducible p21 vector or with control EGFP. Cells were treated as indicated and after 24 h whole-cell protein extracts were analyzed with the indicated antibodies. D. Model depicting the proposed mechanism of action for the combination of anti-MEK and – mTOR therapy in KRAS/BRAF and PI3K/PTEN mutated CRC in p53 wild-type cells. In wild-type p53 backgrounds, p21 is under transcriptional and translational control of p53, c-Myc and mTORC1. PD0325901 blocks the negative transcriptional control of p21 by MEK/c-Myc and enhances the p21 levels, which inhibit apoptosis induction. Concomitant blockade of mTORC1 prevents translation of p21, thereby enabling apoptosis.

DISCUSSION

Agents targeting MEK have shown limited activity used as monotherapy in CRC (37), with PI3K-pathway activation being a potential by-pass mechanism (38, 39). Several clinical trials were initiated to ask if concomitant MEK- and PI3K/mTORC1/2-blockade was efficacious in various diseases (19, 20), including CRC. In this study we sought to investigate the effectiveness of these agents in CRC and whether TP53 mutational status impacted the antitumor response.

We focused on CRCs with concomitant alterations of RAS/BRAF and PIK3CA/PTEN, which entitles for ~8% of the overall CRC population (8), to show that wild-type TP53 is associated with preferential response to combined MEK- and PI3K/mTOR-inhibition. In our in vitro and in vivo models, wild-type TP53 mediates an apoptotic outcome following MEK plus mTORC1/2 blockade. These preclinical observations need to be validated in a larger cohort of patients.

The inhibition of MEK and mTORC1/2 has previously been explored in other settings, including lung (14), pancreatic (15), breast (16, 17) and colorectal tumors (18). However, the present study is the first one in which TP53 status has been associated to treatment outcome. Particularly, the study by Migliardi et al (18) highlighted the limitations of simultaneously targeting MEK- and PI3K/mTORC1/2 in CRC PDXs, with limited antitumor responses across a panel of 40 models. Our study focused on KRAS/BRAF and PIK3CA/PTEN double mutants and we similarly observed that minor response was the best therapeutic outcome in PDX, or resulted in disease stabilization in patients. In addition, our study identified TP53 as a potential predictive marker, providing a clinically relevant tool to maximize the efficacy from this therapeutic combination while avoiding unnecessary treatment of the patients. As suggested by Migliardi and others, we presume that triple therapy with approved anti-EGFR agents would provide further therapeutic advantage in BRAF mutant CRC harboring PI3K-pathway alterations (40).

Mechanistically, our data provide insight into the anti-apoptotic role of p21 in TP53 wild-type tumors. p21 upregulation precluded the induction of apoptosis upon MEK therapy, an effect that was reverted adding mTORC1/2 inhibitors (Fig. 6D).

TP53 mutations are amongst the most frequent mutations in CRC, and occur late during colorectal tumorigenesis (41). Although many studies have tried to elucidate the prognostic and predictive value of p53 alterations in CRC, it remains unclear whether its mutational status could impact outcome and therapy response (42–45). One potential drawback is the limited specificity or sensitivity of the techniques used to determine the p53 status. Two major assays have been used in the clinic for the determination of p53 status, namely mutations in the coding sequence of the TP53 gene (46) and elevated nuclear p53 protein, as assessed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (47). IHC has been generally used as a surrogate marker of TP53 mutations, but this assumption may not always be correct, since many genetic changes do not result in p53 overexpression, and positive immunohistochemistry analysis of p53 may occur in the absence of TP53 mutations (31). Nevertheless, when tissue is scarce or quality compromised, as in some of our specimens, IHC remains as the unique test available to assess p53 status. In CRC, the correlation between TP53 mutation and p53 protein levels is ~70% (46, 47).

Disappointingly, MEK- plus PI3K/Akt/mTORC1/2-inhibitor combinations have shown limited clinical activity even in retrospectively selected, molecularly defined populations (19, 20, 48). The overlapping dose-limiting toxicities of these combinations have prevented the achievement of single-agent maximum tolerated doses, which compromises pathway inhibition and precludes substantial clinical benefit over single-agent strategies (48). Alternative scheduling, with non-continuous/pulsatile dosing of either agent, might be an option to increase tolerability of these regimens and likely to induce a pro-apoptotic response (49). Currently, clinical trials explore further combinations, namely blockade of mutant BRAF with selective BRAF V600E inhibitors (± MEK inhibitors) and EGFR inhibitors in patients with CRC harboring BRAF V600E mutations or targeting MEK- in combination with anti-IGF-1R (in KRAS mutant CRC). It remains to be understood if these strategies will be efficacious in colorectal tumors with concomitant activation of the PI3K-pathway. Our work prompts to investigate if patients with wild-type p53 CRCs obtain higher benefit than those with mutant p53 tumors, in therapeutic combinations that directly or indirectly target Ras/Raf and PI3K. This interrogation should be feasible, as the institutions conducting these studies have implemented prescreening strategies that allow massive parallel assessment of the status of many cancer-related genes, including TP53.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

Targeted therapies' uttermost objective is achieving selective cancer cell death by specifically targeting the driver oncogenes. Equally important is the identification of potentially responding patients by means of biomarkers, in order to avoid overtreatment and to maximize response rate. A significant proportion of colorectal cancer patients carry mutations in both the ERK (Ras/Raf)- and PI3K-pathways, and are therefore potentially susceptible of dual pathway blockade. Nonetheless, half of the tumors harboring alterations in KRAS/BRAF and PIK3CA/PTEN have a TP53 mutation along. In this work, we show that mutant TP53 tumor cells are unable to engage apoptosis upon MEK- plus mTORC1/2-blockade. Our results are of interest for the design of future cancer therapies targeting the ERK/MEK- and PI3K/mTORC1/2 signaling cascades in colorectal cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stephen J. Elledge (Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School) for providing the pINDUCER20-HA-p21Cip1 plasmid. We acknowledge the Pathology Service (VHUH) for providing the statuses of KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA in various tumor specimens. The authors thank Cristina Cruz, José Manuel Pérez, Analía Azaro and Jordi Rodón (Phase I Unit oncologists) for valuable discussions and review of clinical histories. V. Serra, H. G. Palmer, A. Bertotti and L. Trusolino are members of the EuroPDX Consortium.

Financial support: J. Baselga was recipient of a FIS Grant Award (PI09/00623 and RD06/0020/0075), a 'Tumor Biomarkers Collaboration' supported by the Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA) Foundation and a private donation from the Orozco family through the Oncology Research Foundation (FERO). In addition this study was supported in part by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. V. Serra is recipient of an Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) grant FIS PI13/01714 and a GHD/FERO grant. This work was also supported by the FP7-HEALTH-2010 COLTHERES grant (to J. Tabernero); the PI11/00917 Instituto de Salud Carlos III grant (to J. Tabernero); the AIRC (Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro) Investigator Grant 14205 and AIRC 2010 Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology 5 × 1000, project 9970 (to L. Trusolino); the AACR, American Association for Cancer Research—Fight Colorectal Cancer Career Development Award (to A. Bertotti); the AIRC Investigator Grant 15571 (to A. Bertotti); and the unrestricted help of the Cellex Foundation. R. Dienstmann is a recipient of 'La Caixa International Program for Cancer Research & Education.

Footnotes

Disclosures: KJ was full-time employee of Intellekine and Millenium/Takeda.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Diaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2013–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tol J, Koopman M, Cats A, Rodenburg CJ, Creemers GJ, Schrama JG, et al. Chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:563–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, Siena S, Falcone A, Ychou M, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:303–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61900-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benvenuti S, Sartore-Bianchi A, Di Nicolantonio F, Zanon C, Moroni M, Veronese S, et al. Oncogenic activation of the RAS/RAF signaling pathway impairs the response of metastatic colorectal cancers to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody therapies. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2643–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sartore-Bianchi A, Martini M, Molinari F, Veronese S, Nichelatti M, Artale S, et al. PIK3CA mutations in colorectal cancer are associated with clinical resistance to EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1851–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misale S, Yaeger R, Hobor S, Scala E, Janakiraman M, Liska D, et al. Emergence of KRAS mutations and acquired resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Nature. 2012;486:532–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, Lin J, Sjoblom T, Leary RJ, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–13. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh JJ, Routh ED, Rubinas T, Peacock J, Martin TD, Shen XJ, et al. KRAS/BRAF mutation status and ERK1/2 activation as biomarkers for MEK1/2 inhibitor therapy in colorectal cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:834–43. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janku F, Lee JJ, Tsimberidou AM, Hong DS, Naing A, Falchook GS, et al. PIK3CA mutations frequently coexist with RAS and BRAF mutations in patients with advanced cancers. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Nicolantonio F, Arena S, Tabernero J, Grosso S, Molinari F, Macarulla T, et al. Deregulation of the PI3K and KRAS signaling pathways in human cancer cells determines their response to everolimus. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2858–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI37539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jhawer M, Goel S, Wilson AJ, Montagna C, Ling YH, Byun DS, et al. PIK3CA mutation/PTEN expression status predicts response of colon cancer cells to the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1953–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douillard JY, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, et al. Panitumumab-FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1023–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan N, Wong M, Nannini MA, Hong R, Lee LB, Price S, et al. Bcl-2/Bcl-xL inhibition increases the efficacy of MEK inhibition alone and in combination with PI3 kinase inhibition in lung and pancreatic tumor models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:853–64. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carracedo A, Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Rojo F, Salmena L, Alimonti A, et al. Inhibition of mTORC1 leads to MAPK pathway activation through a PI3K-dependent feedback loop in human cancer. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3065–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI34739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoeflich KP, O'Brien C, Boyd Z, Cavet G, Guerrero S, Jung K, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of MEK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors in basal-like breast cancer models. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4649–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Migliardi G, Sassi F, Torti D, Galimi F, Zanella ER, Buscarino M, et al. Inhibition of MEK and PI3K/mTOR suppresses tumor growth but does not cause tumor regression in patient-derived xenografts of RAS-mutant colorectal carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2515–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juric D, Soria J-C, Sharma S, Banerji U, Azaro A, Desai J, et al. A phase 1b dose-escalation study of BYL719 plus binimetinib (MEK162) in patients with selected advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32 ASCO Meeting, abst 9051. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heist RS, Gandhi L, Shapiro G, Rizvi NA, Burris HA, Bendell JC, et al. Combination of a MEK inhibitor, pimasertib (MSC1936369B), and a PI3K/mTOR inhibitor, SAR245409, in patients with advanced solid tumors: Results of a phase Ib dose-escalation trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31 ASCO Meeting, abst 2530. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Speranza G, Kinders RJ, Khin S, Weil MK, Do KT, Horneffer Y, et al. Pharmacodynamic biomarker-driven trial of MK-2206, an AKT inhibitor, with AZD6244 (selumetinib), a MEK inhibitor, in patients with advanced colorectal carcinoma (CRC) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 ASCO Meeting, abst 3529. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juric D, Rodon J, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Burris HA, Bendell J, Berlin JD, et al. BYL719, a next generation PI3K alpha specific inhibitor: Preliminary safety, PK, and efficacy results from the first-in-human study. Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2012: Cancer Research; 2012. Abstract CT-01. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou TC. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:621–81. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meerbrey KL, Hu G, Kessler JD, Roarty K, Li MZ, Fang JE, et al. The pINDUCER lentiviral toolkit for inducible RNA interference in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3665–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019736108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puig I, Chicote I, Tenbaum SP, Arques O, Herance JR, Gispert JD, et al. A personalized preclinical model to evaluate the metastatic potential of patient-derived colon cancer initiating cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6787–801. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Todaro M, Alea MP, Di Stefano AB, Cammareri P, Vermeulen L, Iovino F, et al. Colon cancer stem cells dictate tumor growth and resist cell death by production of interleukin-4. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:389–402. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreso A, O'Brien CA. Colon cancer stem cells. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2008;Chapter 3(Unit 3):1. doi: 10.1002/9780470151808.sc0301s7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dienstmann R, Serpico D, Rodon J, Saura C, Macarulla T, Elez E, et al. Molecular profiling of patients with colorectal cancer and matched targeted therapy in phase I clinical trials. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2062–71. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Single Nucleotide Polymorfism Database. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/

- 30.1000 Genomes Database. Available from: http://www.1000genomes.org/

- 31.Yemelyanova A, Vang R, Kshirsagar M, Lu D, Marks MA, Shih Ie M, et al. Immunohistochemical staining patterns of p53 can serve as a surrogate marker for TP53 mutations in ovarian carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and nucleotide sequencing analysis. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2011;24:1248–53. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chudnovsky Y, Adams AE, Robbins PB, Lin Q, Khavari PA. Use of human tissue to assess the oncogenic activity of melanoma-associated mutations. Nat Genet. 2005;37:745–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson TM, Meade K, Pathak N, Marques MR, Attardi LD. Knockin mice expressing a chimeric p53 protein reveal mechanistic differences in how p53 triggers apoptosis and senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1215–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706764105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beuvink I, Boulay A, Fumagalli S, Zilbermann F, Ruetz S, O'Reilly T, et al. The mTOR inhibitor RAD001 sensitizes tumor cells to DNA-damaged induced apoptosis through inhibition of p21 translation. Cell. 2005;120:747–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbas T, Dutta A. p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:400–14. doi: 10.1038/nrc2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seoane J, Le HV, Massague J. Myc suppression of the p21(Cip1) Cdk inhibitor influences the outcome of the p53 response to DNA damage. Nature. 2002;419:729–34. doi: 10.1038/nature01119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinehart J, Adjei AA, Lorusso PM, Waterhouse D, Hecht JR, Natale RB, et al. Multicenter phase II study of the oral MEK inhibitor, CI-1040, in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung, breast, colon, and pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4456–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balmanno K, Chell SD, Gillings AS, Hayat S, Cook SJ. Intrinsic resistance to the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) is associated with weak ERK1/2 signalling and/or strong PI3K signalling in colorectal cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2332–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halilovic E, She QB, Ye Q, Pagliarini R, Sellers WR, Solit DB, et al. PIK3CA mutation uncouples tumor growth and cyclin D1 regulation from MEK/ERK and mutant KRAS signaling. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6804–14. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–3. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kressner U, Inganas M, Byding S, Blikstad I, Pahlman L, Glimelius B, et al. Prognostic value of p53 genetic changes in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:593–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.2.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allegra CJ, Paik S, Colangelo LH, Parr AL, Kirsch I, Kim G, et al. Prognostic value of thymidylate synthase, Ki-67, and p53 in patients with Dukes' B and C colon cancer: a National Cancer Institute-National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project collaborative study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:241–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Russo A, Bazan V, Iacopetta B, Kerr D, Soussi T, Gebbia N. The TP53 colorectal cancer international collaborative study on the prognostic and predictive significance of p53 mutation: influence of tumor site, type of mutation, and adjuvant treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7518–28. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walther A, Johnstone E, Swanton C, Midgley R, Tomlinson I, Kerr D. Genetic prognostic and predictive markers in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:489–99. doi: 10.1038/nrc2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris CC. p53 tumor suppressor gene: at the crossroads of molecular carcinogenesis, molecular epidemiology, and cancer risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(Suppl 3):435–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baas IO, Mulder JW, Offerhaus GJ, Vogelstein B, Hamilton SR. An evaluation of six antibodies for immunohistochemistry of mutant p53 gene product in archival colorectal neoplasms. J Pathol. 1994;172:5–12. doi: 10.1002/path.1711720104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shimizu T, Tolcher AW, Papadopoulos KP, Beeram M, Rasco DW, Smith LS, et al. The clinical effect of the dual-targeting strategy involving PI3K/AKT/mTOR and RAS/MEK/ERK pathways in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2316–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayat Khan K, Yan L, Mezynski J, Patnaik A, Moreno V, Papadopoulos KP, et al. A phase I dose escalation study of oral MK-2206 (allosteric Akt inhibitor) with oral selumetinib (AZD6244; ARRY-142866) (MEK 1/2 inhibitor) in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 ASCO Meeting, abst e13599. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.