Abstract

NEAT1 has been reported to affect cancer progression, which was subsequently confirmed in multiple cancers. Hsa-miRNA-335-5p (miR-335-5p) has recently been identified as an anticancer agent in various organs. However, the relationship between NEAT1 and miR-335-5p remains poorly understood. In this study, we investigated the effects of NEAT1 and miR-335-5p on development of pancreatic cancer. The ectopic expression of miR-335-5p in pancreatic cancer cell lines significantly suppressed cell growth by inhibiting c-met. In addition, downregulating NEAT1 upregulates miR-335-5p. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the NEAT1/miR-335-5p/c-met axis plays a pivotal role in pancreatic cancer by regulating the proliferation, metastasis, and apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cells in vivo and in vitro.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, NEAT1, mircroRNA-335-5p, c-met

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer ranks among the most malignant of human cancers [1]. Its prognosis is extremely poor, with a 5-year relative survival rate of 5% [2] and a median survival of 3.5 months for non-resectable tumors [3]. Surgical resection is the only potentially curative therapy [4], but relapses are common even in these cases [5]. Therefore, the pathological mechanisms of pancreatic cancer urgently need to be understood to facilitate early diagnosis and advance therapeutic modalities and agents.

Recent evidence has suggested a relationship between several long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and metastasis, drug resistance and other clinical outcomes in several types of cancers [6-10]. NEAT1, a nuclear-restricted long non-coding RNA, is known as a transcriptional regulator for numerous genes. NEAT1 was first transcribed from the multiple endocrine neoplasia locus [11], suggesting that this lncRNA affects cancer progression, which was subsequently confirmed in multiple cancers and various studies [12-18]. However, the emerging potential role of NEAT1 in pancreatic cancer remains unclear.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small noncoding regulatory RNAs, which can broadly regulate target genes by binding to a complementary sequence in their 3’UTR [19,20]. miRNAs play important roles in tumor development by regulating the expression of various oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [21]. For example, miR-199a suppresses the tumorigenicity and multidrug resistance of ovarian cancer-initiating cells [22], whereas miR-27a reverses the multidrug resistance phenotype by regulating the expression of MDR1 and β-catenin [23]. Furthermore, miR-146b-5p suppresses the translation of EGFR, binds to the EGFR 3’UTR, and inhibits the migration of glioma cells [24]. Similarly, miR-335 activates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway to limit cell proliferation and neoplastic cell transformation [25]. miR-335 also targets Bcl-w and negatively regulates the invasiveness of ovarian cancer cells [26]. In addition, miR-335 inhibits the proliferation and migration of human mesenchymal stem cells by targeting RUNX2 [27] and is involved in regulating target genes in several oncogenic signal-pathways, such as p53, MAPK, TGF-β, Wnt, ERbB, mTOR, Toll-like receptor and FAK (focal adhesion kinase) [28]. However, the mechanism and the role of miR-335 in regulation of pancreatic cancer remain unknown.

The molecular targeting of oncogenes as a therapeutic approach is currently being intensively investigated. Specifically, the identification of deregulated oncogenic pathways in pancreatic cancer will lead to new therapeutic options. To this end, c-Met, a tyrosine kinase receptor, is overexpressed in a subset of human epithelial malignancies [29] including colorectal [30,31], gastric [32,33], ovarian [34,35], endometrial [36], breast [37,38], prostate [39] and hepatocellular [40] carcinomas. This overexpression may be the result of c-Met amplification [31].

In this study, we showed for the first time that miR-335-5p directly targets and regulates human c-met gene. Collectively, we discovered that NEAT1 promotes pancreatic cancer cell growth, migration and invasion while inhibiting cell apoptosis. Moreover, miR-335-5p also inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth, migration and invasion and promotes cell apoptosis by targeting the 3’-UTR of c-Met. Thus, we uncovered a pathway that is established by NEAT1/miRNAs/c-met axis, which promotes pancreatic cancer malignancy.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human pancreatic cancer cell lines (PANC-1, SW1990, CAPAN-1, JF305 and PC-3) and the nonmalignant HPC-Y5 cell line were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sijiqing biochemical, Hangzhou, China) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Clinical samples and RNA isolation

Fifteen paired human pancreatic cancer and matched adjacent normal tissue samples from the same patient were collected with patient consent at the time of surgery. The tumors were graded according to the WHO criteria (World Health Organization, 2008). The tissue specimens and clinical information were obtained as part of a study approved by the Institutional Review Board at Xinhua Hospital of Shanghai Jiaotong University, China. Total RNA was extracted from pancreatic cancer cells using TRIzol Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

Total RNA (5 µg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, USA) with specific primers. The cDNA was used as template to amplify either mature miR-335-5p or an endogenous control U6 snRNA by PCR. NEAT1 or an endogenous control, GAPDH, were also amplified. This PCR was followed by SYBR-Green real-time PCR (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The PCR procedure was as follows: 94°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s. The relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔct method using U6 snRNA or GAPDH mRNA as an internal control.

Plasmid construction and cell transfection

We commercially synthesized the 2’-O-methylmodified antisense oligonucleotides of miR-335-5p (ASO-miR-335-5p) to inhibit miR-335-5p. The 3’UTRs of c-met and NEAT1, which contain the miR-335-5p binding site, and the mutant 3’UTR fragment, which contains the mutant binding site of miR-335-5p, were obtained by annealing double-strand DNA and inserted into the pmirGLO vector at the BamHI and EcoRI sites.

The pSilencer/shR-NEAT1 plasmid, which expresses a siRNA that targets NEAT1 transcription, was constructed by annealing single-strand hairpin cDNA and inserting it into a pSilencer2.1-U6 neo vector (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) at the BamHI and HindIII sites. The full-length sequences of human NEAT1 and c-met cDNA deposited in Genbank were cloned into the EcoRI/Xhol restriction sites of pcDNA3. The resultant plasmids were named pcDNA3/NEAT1 and pcDNA3/c-met. The promoter of miR-101 was amplified from genomic DNA and cloned into the KpnI/EcoRI restriction sites of pGL3-Basic (Promega) upstream of the firefly luciferase gene. At 60% confluency, the cells were transfected with plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was measured using an MTT assay. Transiently transfected cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a cell density of 1.0 × 104 cells/well and then cultured for 12 h intervals for a total of 2 days. Subsequently, MTT solution (0.2 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h. The solution was then carefully aspirated, and 150 μL DMSO was added to each well to dissolve the crystal. The absorbance was determined at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA).

Cell apoptosis assay

The fraction of apoptotic cells was determined with the Annexin V-7-ADD apoptosis detection kit (Roche, Switzerland). Briefly, 48 hours (h) after transfection, the cells were collected and washed twice with cold PBS buffer, resuspended in 200 µl of binding buffer, and incubated with 20 µl of Annexin-V-R-PE for 20 minutes in a dark ice bath. Subsequently, 10 μl of 7-AAD was added, and the cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry. Cells treated with DMSO were used as the negative control.

Cell migration and invasion assays

For the migration assay, 1.0 × 105 cells were suspended in serum-free medium and plated in Transwell chambers chambers (Corning Costar, NY, USA). Briefly, medium containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After incubating the cells for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, they were fixed in methanol for 15 min and stained with 0.05% crystal violet in PBS for 15 min before being counted under a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Cells that had not invaded upper chamber were removed by wiping the surface with a cotton swab, and invasive cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS and subsequently stained with 1% crystal violet in 2% ethanol. The cells on the lower surface of the filter were photographed under a light microscope (100 × magnification).

These procedures were also followed for the invasion assay, but the filters were pre-coated with 100 µl of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, CA, USA) at a 1:4 dilution in DMEM to mimic a basement membrane.

DNA hybridizations

DNA fragments were transferred from agarose gels to nylon membranes (Amersham) by vacuum blotting. The probes were labeled by nick translation and hybridizations with [α-32P] dCTP (Amersham) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). The partial nucleotide fragments internal to the 16S rDNA (Accession No. AY509240.1) and cat gene (GenBank accession AJ132968.1) were used as probes in this work. The sequences were analyzed with the MEGALIGN program (DNA Star, Madison, WI).

Western blot analysis

Total cellular extracts were obtained using RIPA buffer on ice. Equal amounts of protein (30 μg protein per lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA). The immunoblots were blocked with 5% skim milk in TBS/Tween 20 (0.05%, v/v) at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was then probed primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-c-met, anti-actin and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were then developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence western blotting detection system (Amersham Bioscience, UK).

Target prediction and dual luciferase reporter assay

Based on bioinformatic predictions (TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/mamm_31/), miRDB (http://www.mirdb.org/miRDB/) and PicTar (http://www.pictar.org/)), c-met was selected as candidate target of miR-335-5p. The 3’UTR segments of c-met containing putative binding sites for miR-335-5p were obtained by annealing and inserted into the pmirGLO vector. The wild-type reporter construct pmirGLO/c-met-3’UTR and the mutant reporter construct pmirGLO/c-met-3’UTR mut, in which a site that perfectly complements miR-335-5p was mutated by annealing, were used for miRNA functional analysis. The wild-type and mutant insertions were confirmed by DNA sequencing. All primer information is available in Table 2. For the luciferase reporter experiments, PANC-1 and SW990 cells were co-transfected with the miR-335-5p in a 48-well plate followed by the pmirGLO/c-met-3’UTR reporter vector or the pmirGLO/c-met-3’UTR mut. The firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase levels were measured 48 h after transfection. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

In vivo metastatic assay and bioluminescent imaging

The animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of the Experiment Animal center of the Fourth Military Medical University. Athymic 4-week-old female nude mice were obtained from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center of China and housed under standard conditions. Each mouse was injected via the tail vein with 2 × 106 cells suspended in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline. To track cells in vivo, the cells were stably transfected with firefly luciferase. Pancreas metastases was quantitated in vivo by imaging based on bioluminescence. Mice to be imaged were injected with 150 mg/kg of D-luciferin (Xenogen, Hopkinton, MA) intraperitoneally in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline and then anesthetized with a continuous flow of pentobarbital. Ten minutes later, bioluminescence images of the mice were obtained with the IVIS Imaging System (Xenogen) and then analyzed using the IVIS Living Image software (Xenogen) software.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times. The quantitative data between groups were compared and analyzed by Student’s t-test (two tailed) or a one-way analysis of variance. The data are expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD), and P≤0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference using the Students-Newman-Keuls test.

Results

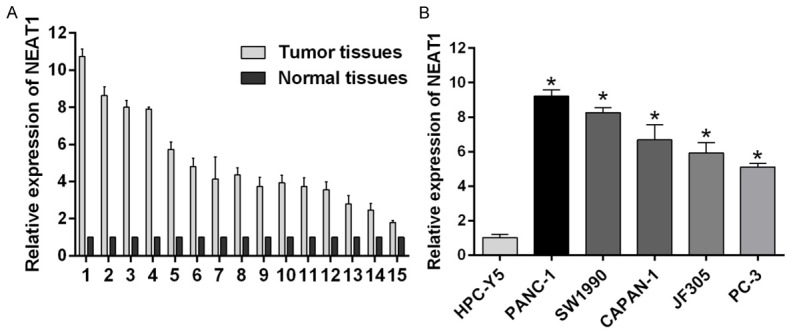

NEAT1 is up-regulated in pancreatic cancer

We used quantitative real time RT-PCR to determine the expression of NEAT1 in 15 human pancreatic cancer tissues and adjacent normal tissues (Figure 1A). Moreover, real-time PCR showed that NEAT1 expression was significantly overexpression in the pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1, SW1990, CAPAN-1, JF305 and PC-3 relative to the prostate cell line HPC-Y5 (Figure 1B). In general, NEAT1 expression was significantly upregulated in pancreatic cancer.

Figure 1.

NEAT1 is up-regulated in pancreatic cancer. A. Endogenous NEAT1 level in pancreatic cancer samples and pancreatic tissues as measured by real-time qRT-PCR. The expression of NEAT1 is normalized to GAPDH (*p < 0.05). B. The relative abundance of NEAT1 in the pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1, SW1990, CAPAN-1, JF305, and PC-3, and the normal prostate cell line HPC-Y5 (*p < 0.05).

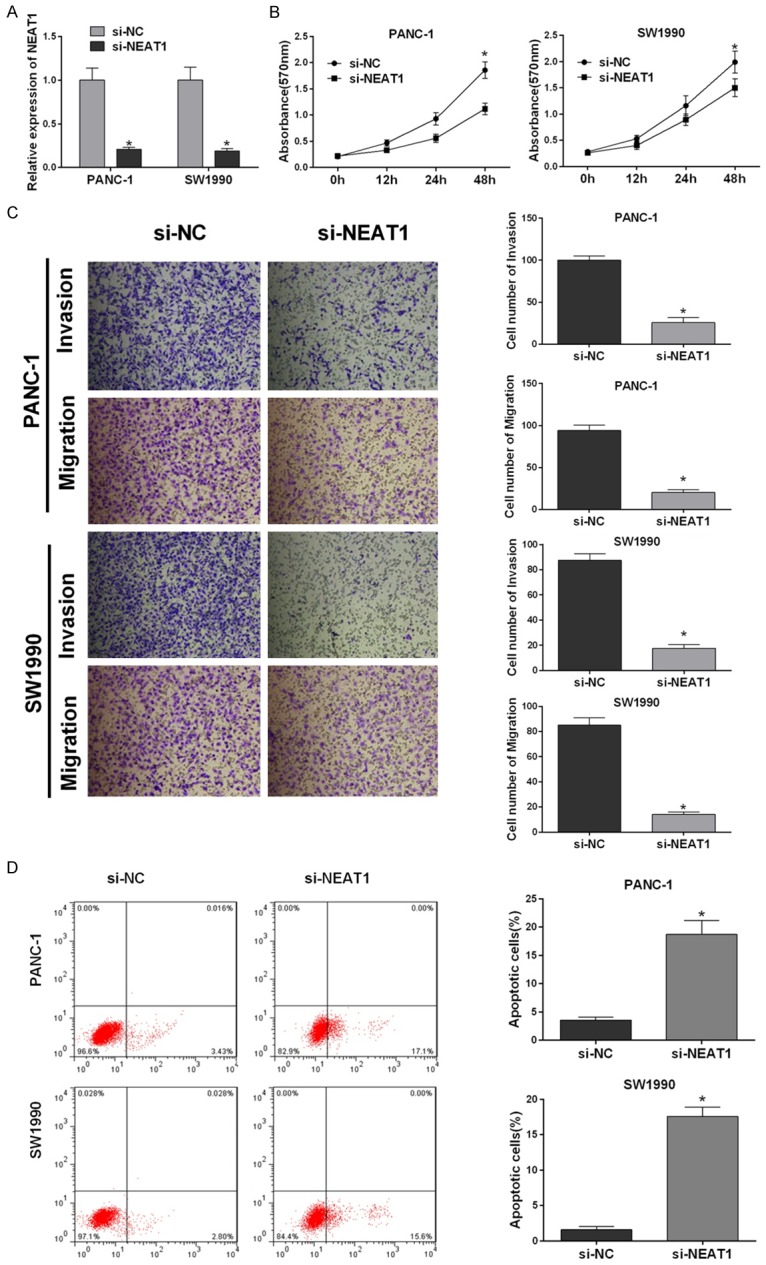

NEAT1 promotes the long-term proliferation and inhibits the apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cell lines

To research the function of NEAT1 in pancreatic cancer, we constructed si-NEAT1 to knock down its expression in pancreatic cancer cell lines. First, we measured the NEAT1 mRNA levels in PANC-1 and SW1990 cells transfected with si-NEAT1 or si-NC by real time RT-PCR. The expression of NEAT1 was significantly decreased in PANC-1 and SW1990 cells transfected with si-NEAT1 compared with NC cells (Figure 2A). The viability of pancreatic cancer cells transfected with si-NEAT1 was evaluated with the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl- tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay; si-NEAT1 reduced cell viability 12, 24 or 72 h after transfection (Figure 2B). In parallel, we analyzed the migration and invasiveness of the pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1 and SW1990. We examined the migration and invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells transfected with si-NEAT1 and found that cells transfected with si-NEAT1 migrated less and were less invasive than control cells (Figure 2C). These data demonstrated that NEAT1 might promote migration and invasion in pancreatic cancer. The fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis showed that reduced NEAT1 expression resulted in pancreatic cancer cell apoptosis. NEAT1 suppression significantly decreased the percentage of total apoptotic cells (early apoptotic + late apoptotic) compared with si-NC in PANC-1 and SW1990 cells (Figure 2D). These results indicated that NEAT1 promoted proliferation and decreased apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells.

Figure 2.

NEAT1 promotes long-term proliferation and inhibits the apoptosis of the pancreatic cancer cell lines. A. NEAT1 expression levels measured by real-time RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from PANC-1 and SW1990 cells transfected with si-NEAT1 or si-NC, and GAPDH served as an endogenous control. The relative NEAT1 expression level (mean ± SD) is shown (*P < 0.05). B. Cell proliferation was assessed with an MTT assay. After PANC-1 and SW1990 cells were transfected with the si-NEAT1 or si-NC, the MTT assay was used to determine relative cell growth 0, 12, 24 and 48 h after transfection. The relative cell growth was normalized to the growth activity of PANC-1 and SW1990 cells in the control groups (*P < 0.05). C. Transwell migration and Matrigel invasion assays were used to evaluate the migration and invasion of PANC-1 and SW1990 cells transfected with si-NEAT1 or si-NC. Representative fields of migrating or invasive cells on the membrane. The data represent three independent experiments (*P < 0.05). D. The incidence of apoptosis was studied by flow cytometry. The cells were stained with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and counterstained with 7-ADD. The data represent three independent experiments (*P < 0.05).

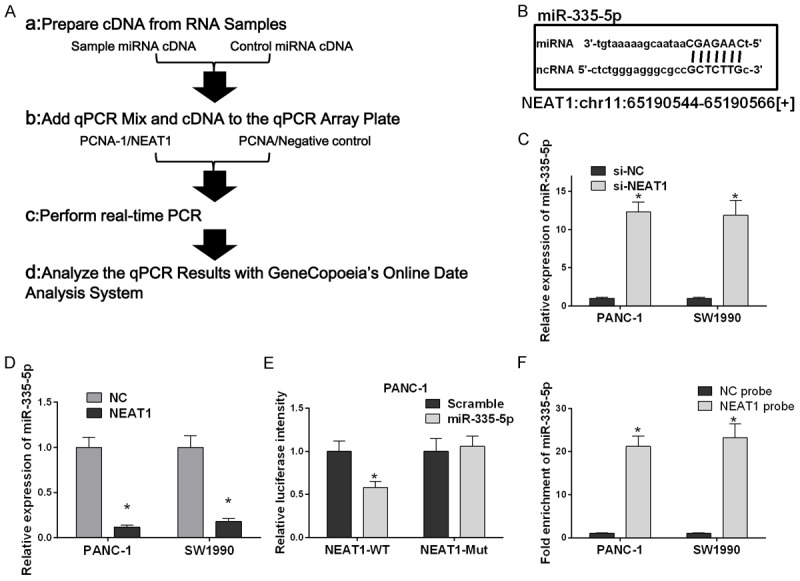

NEAT1 decreases the expression of miR-335-5p in the pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1 and SW1990

To study the mechanisms by which NEAT1 promotes the proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of the pancreatic cancer cells, we selected miR-335-5p as the research target. The expression level of miR-335-5p in PANC-1 or SW1990 cells transfected with pcDNA3/NEAT1 or control was measured in a validation experiment by qRT-PCR, which indicated a clear decrease in the level of miR-335-5p in transfected PANC-1 and SW1990 cells (Figure 3D). The RT-PCR relative quantification procedure and the miR-335-5p and ncRNA sequences are shown (Figure 3A and 3B). Moreover, the miR-335-5p expression level in PANC-1 and SW1990 cells transfected with si-NEAT1 or si-NC was measured, and this experiment showed that a decrease in NEAT1 expression resulted in to the upregulation of the NEAT1-targeting miRNA miR-335-5p (Figure 3C). Thus, we investigated the effect on miR-335-5p on NEAT1 expression. To this end, we transfected PANC-1 cells with the wild-type (WT) or mutated (Mut) version of the luciferase-NEAT1 3’-UTR reporter vector as well as the miR-335-5p or scramble. This experiment showed that miR-335-5p, but not the mutant, reduced the intensity of the luciferase-NEAT1 WT (Figure 3E). A Southern blot hybridizations assay was employed to further verify the relationship between NEAT1 and miR-335-5p, which indicated that NEAT1 was enriched more than 20-fold in miR-335-5p in PANC-1 or SW1990 cells (Figure 3F). These results show that miR-335-5p is suppressed by NEAT1 overexpression due to combination and interaction.

Figure 3.

NEAT1 decreases the expression level of miR-335-5p in the pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1 and SW1990. A. qRT-PCR relative quantification procedure. B. miR-335-5p and ncRNA sequences. C. Measurement of the miR-335-5p expression levels by Real-time quantitative PCR analysis. Small RNA was extracted from PANC-1 and SW1990 cells transfected with si-NEAT1 or si-NC, and U6 small nuclear RNA served as an endogenous control. The relative miR-335-5p expression level (mean ± SD) is shown (*P < 0.05). D. The relative abundance of miR-335-5p in the pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1 and SW1990 transfected with NEAT1 or NC (*p < 0.05). E. PANC-1 cells were transfected with the wild-type (WT) or mutant (Mut) luciferase-NEAT1 3’-UTR reporter vector as well as miR-335-5p or scramble siRNA. miR-335-5p reduced the intensity the luciferase-NEAT1 3’-UTR reporter signal, whereas the mutant luciferase-NEAT1 3’-UTR failed to alter the luciferase intensity (*P < 0.05). F. Southern blot hybridizations of miR-335-5p digested total DNA from different recombinant strains with a 500-bp probe internal to the cat gene. The relative fold enrichment of miR-335-5p (mean ± SD) is shown (*P < 0.05).

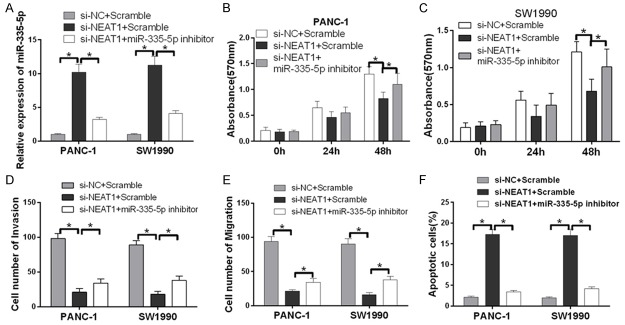

miR-335-5p inhibitor counteracts NEAT1 suppression

First, we detected the miR-335-5p expression level in PANC-1 and SW1990 cells transfected with either pSilencer NC, pSilencer/si-NEAT1, or pSilencer/si-NEAT1 together with miR-335-5p inhibitor by qRT-PCR. Transfecting cells with pSilencer/si-NEAT1 increased the expression of miR-335-5p compared with NC cells; miR-335-5p inhibitor reversed this effect (Figure 4A). An MTT assay was then used to characterize the effects of NEAT1 on tumor cell viability. The results of this assay indicated that knocking down NEAT1 inhibited the viability of PANC-1 and SW1990 cells, and this effect was counteracted by miR-335-5p inhibitor (Figure 4B and 4C). In parallel, cell invasion and migration assays were performed using Transwell chambers with or without Matrigel. Specifically, PANC-1 and SW1990 cells co-transfected with miR-335-5p inhibitor and pSilencer NC, pSilencer/si-NEAT1, or pSilencer/si-NEAT1 were seeded in Transwell chambers, and images were taken to count the number of cells. The data demonstrate that pSilencer/si-NEAT1 can suppress the migration and invasiveness of cells relative to the control, but this suppression is rescued by miR-335-5p inhibitor (Figure 4D and 4E). Next, we studied the effect of NEAT1 on apoptosis. The fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis showed that reduced NEAT1 expression resulted in pancreatic cancer cell apoptosis. Furthermore, miR-335-5p inhibitor counteracted the effect of si-NEAT1 (Figure 4F). Taken together, these data show that NEAT1 suppression inhibits the long-term proliferation and increases apoptosis of pancreatic cancer cell lines, and these effects are rescued by an miR-335-5p inhibitor.

Figure 4.

miR-335-5p inhibitor counteracts NEAT1 suppression. A. miR-335-5p expression levels measured by real-time RT-PCR. PANC-1 and SW1990 cells were co-transfected with control siRNA, siNEAT1 or siNEAT1; miR-335-5p inhibitor rescued miR-335-5p protein levels compared with the siNEAT1 group. The relative miR-335-5p expression level (mean ± SD) is shown (*P < 0.05). B and C. Cell proliferation was detected with an MTT assay. After PANC-1 and SW1990 cells were transfected with the control, siNEAT1 or siNEAT1 together with the miR-335-5p inhibitor, an MTT assay was used to assess relative cell growth 0, 12, 24 and 48 h after transfection. The relative cell growth was normalized to the growth of PANC-1 and SW1990 cells in the control groups (*P < 0.05). D and E. Transwell migration and Matrigel invasion assays were used to evaluate the migration and invasion of PANC-1 and SW1990 cells transfected with the control, siNEAT1 or siNEAT1 together with the miR-335-5p inhibitor. The data represent three independent experiments (*P < 0.05). F. The incidence of apoptotic cells was studied by flow cytometry. The cells were stained with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and counterstained with 7-ADD. The data represent three independent experiments (*P < 0.05).

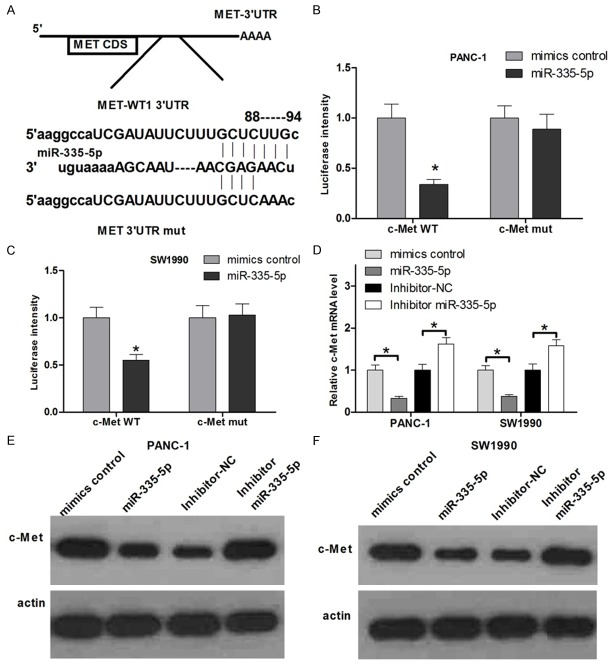

c-met is a direct target of miR-335-5p

Based on the above discussion, NEAT1 suppression upregulates the expression of miR-335-5p and simultaneously regulates long-term proliferation and increases apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cell lines. To determine the mechanism of miR-335-5p-mediated cell dysregulation in pancreatic cells, we next identified target genes that could be responsible for the effect of miR-335-5p. Potential target genes of miR-335-5p were predicted using miRanda, TargetScan and PicTar, which suggested that miR-335-5p targets c-met (Figure 5A). We performed luciferase reporter assays to examine whether miR-335-5p interacts directly with its target c-met. We constructed a series of 3’UTR fragments, including the wild-type c-Met 3’UTR and a binding site mutant (Figure 5A). These fragments were then inserted into the pmirGLO luciferase reporter plasmid. Co-transfecting miR-335-5p and the wild-type c-met 3’UTR into PANC-1 and SW1990 cells significantly decreased the luciferase signal compared with the controls. However, co-transfecting mutant c-met 3’UTR and miR-335-5p mimics failed to alter the luciferase intensity (Figure 5B and 5C). Furthermore, the overexpression of miR-335-5p reduced c-met mRNA and protein expression in PANC-1 and SW1990 cells, whereas miR-335-5p inhibitor increased the level of c-met (Figure 5D-F). Taken together, these results suggest that miR-335-5p binds directly to the 3’UTR of c-met, thereby repressing gene expression.

Figure 5.

c-met is a direct target of miR-335-5p. A. The predicted miR- miR-335-5p binding site on the c-met mRNA 3’-UTR and the missense mutation at the miR-378 “seed region” binding site on the c-met mRNA 3’-UTR are shown. B and C. PANC-1 and SW1990 cells were transfected with the wild-type (WT) or mutant (Mut) luciferase-c-met 3’-UTR reporter vector as well as the miR-335-5p mimic or mimic-NC. miR-335-5p reduced the intensity of the luciferase-c-met 3’-UTR reporter signal, whereas the mutant luciferase- c-met 3’-UTR failed to alter the luciferase intensity (*P < 0.05). D. PANC-1 and SW1990 cells were transfected with the mimic NC, miR-335-5p mimic, inhibitor-NC or inhibitor miR-335-5p. The mRNA expression level of c-met was measured by real-time RT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH (*P < 0.05). E and F. c-met expression levels measured with a Western blot. Protein was extracted from PANC-1 and SW1990 cells transfected with the mimic NC, miR-335-5p mimic, inhibitor-NC or inhibitor miR-335-5p. The endogenous expression levels of actin were used for normalization.

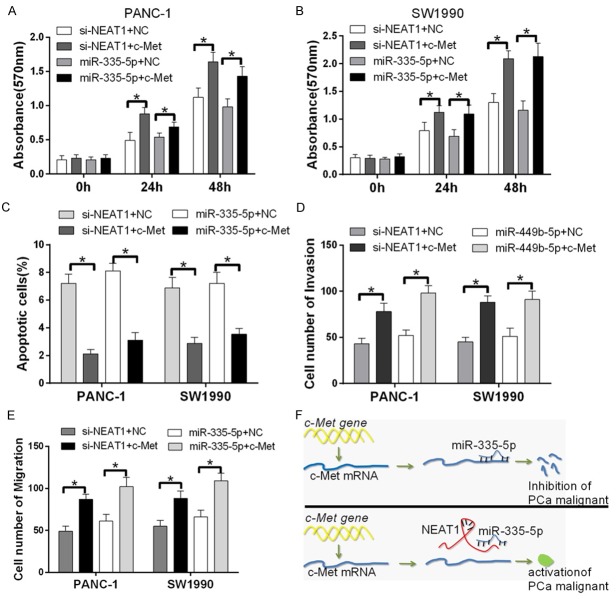

NEAT1 and miR-335-5p regulates pancreatic cancer cell growth, invasion and migration via c-met

Next, we explored the relationship between NEAT1, miR-335-5p and c-met. The activation of c-Met promotes tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion. Therefore, we transfected PANC-1 and SW1990 cells with pSilencer/shR-NEAT1, pSilencer/shR-NEAT1 and c-met, miR-335-5p mimic or miR-335-5p mimic and c-met. An MTT assay was used to assess cell growth at 0, 24 and 48 h after transfection. C-met increased cell proliferation relative to the pSilencer/shR-NEAT1 or miR-335-5p mimics group (Figure 6A and 6B). In addition, Colony formation assays were performed to confirm this tendency (Figure S1). Next, we studied the effect of c-met on apoptosis. The fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis showed that the forced expression of c-met inhibited pancreatic cancer cell apoptosis (Figure 6C). Moreover, Transwell migration and Matrigel invasion assays revealed that c-met overexpression increased the number of migrating cells (Figure 6D and 6E). Thus, the downregulation of miR-335-5p induces c-met expression to inhibit pancreatic cancer malignancy. Furthermore, NEAT1 suppresses miR-335-5p transcription, which increases c-met translation and consequently promotes pancreatic carcinogenesis (Figure 6F). The data demonstrate that NEAT1 and miR-335-5p regulate pancreatic cancer cell growth, invasion and migration via c-met in vitro.

Figure 6.

NEAT1 and miR-335-5p regulates pancreatic cancer cell growth, invasion and migration via c-met. A and B. Cell proliferation was detected with an MTT assay. After PANC-1 and SW1990 cells were transfected with si-NEAT1, si-NEAT1 and c-met, miR-335-5p mimic or miR-335-5p mimics and c-met, an MTT assay was used to assess relative cell growth 0, 24 h and 48 h after transfection (*P < 0.05). The relative cell growth was normalized to the growth of PANC-1 and SW1990 cells in the control groups. C. The incidence of apoptotic cells was studied by flow cytometry. The cells were stained with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and counterstained with 7-ADD. D and E. Transwell migration and Matrigel invasion assays were used to evaluate the migration and invasion of PANC-1 and SW1990 transfected with the si-NEAT1, si-NEAT1 and c-met, miR-335-5p mimic or miR-335-5p mimic and c-met. The data represent three independent experiments (*P < 0.05). F. Model of NEAT1-induced miR-335-5p regulates pancreatic cancer malignancy. The downregulation of miR-335-5p induces c-met expression and inhibits pancreatic cancer malignancy. Conversely, NEAT1 suppresses miR-335-5p transcription, which increases c-met translation and results in the activation of pancreatic cancer malignancy.

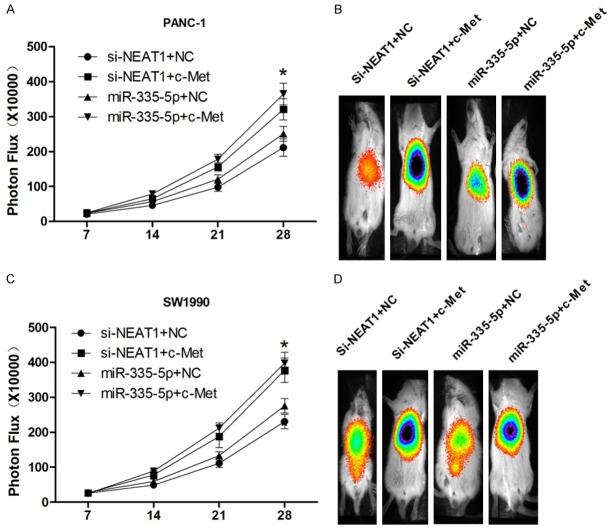

NEAT1 and miR-335-5p regulate pancreatic cancer cell tumor growth via c-met in vivo

To further confirm the above assumptions, we treated PANC-1 and SW1990 xenograft tumor-bearing nude mice stably transfected with Firefly luciferase with pSilencer/shR-NEAT1, pSilencer/shR-NEAT1 and c-met, miR-335-5p mimic or miR-335-5p mimic and c-met. Ten minutes later, bioluminescence images of the mice were obtained using the IVIS Imaging System (Xenogen) 10 min later and then analyzed the images using the IVIS Living Image (Xenogen) software. Compared with the controls, high-density signals were captured in the c-met group (Figure 7A-D). These data reveal that NEAT1 and miR-335-5p regulate pancreatic cancer cell tumor growth via c-met in vivo.

Figure 7.

NEAT1 and miR-335-5p regulate pancreatic cancer cell tumor growth via c-met in vivo. (B and D) PANC-1 and SW1990 cells were stably transfected with si-NEAT1, si-NEAT1 and c-met, miR-335-5p mimic or miR-335-5p mimic and c-met; different groups of cells were stably transfected with firefly luciferase to permit the bioluminescence imaging of mice (A and C) (*P < 0.05).

Discussion

Here, we identified a NEAT1/miR-335-5p/c-met axis that is involved in pancreatic cancer development and progression. We found that knocking down NEAT1 lncRNA significantly impaired the growth and migration of pancreatic cancer cells in vitro. These findings corroborated previous findings in NSCLC [14] and HCC [41], which showed that knocking down NEAT1 expression in vitro inhibited the migration and invasiveness of cancer cells. Moreover, we found that the expression of NEAT1 increased the level miR-335-5p. Conversely, aberrant miR-335-5p expression suppressed the intensity of the luciferase signal of NEAT1. Thus, the expression warrants further investigation with a dual luciferase reporter assay. The biological mechanisms of NEAT1 regulation in pancreatic cancer currently remain poorly understood.

To further investigate the mechanisms of NEAT1 in pancreatic cancer, we studied miR-335-5p and its target mRNA. First, we predicted putative targets of miR-335-5p using the prediction programs TargetScan, PicTar, and miRanda. Subsequently, the luciferase reporter assay identified c-met as the target because transfection with miR-335-5p reduced the luciferase activity of constructs carrying the target c-met fragment. Furthermore, the ectopic expression of miR-335-5p simultaneously reduced the mRNA and protein levels of c-met. Gao et al. also found that the oncogene c-met is a target gene of miR-335 in breast cancer cells [42]. MET can act as an oncogene, and its signaling plays essential roles in regulating tumorigenesis in various cancers, such as lung cancer [43], including NSCLC [44].

Next, we explored the relationship between NEAT1, miR-335-5p and c-met. By co-transfecting shR-NEAT1 and c-met or miR-335-5p mimic and c-met into PANC-1 and SW1990 cells, we found that c-met increased cell proliferation and inhibited pancreatic cancer cell apoptosis. Thus, miR-335-5p reduced c-met expression, and NEAT1 overexpression suppressed miR-335-5p transcription, leading to an increase in c-met translation, which promoted pancreatic cancer malignancy. Moreover, the xenograft tumor-bearing nude mice experiment revealed that NEAT1 and miR-335-5p regulate pancreatic cancer cell tumor growth via c-met in vivo.

In conclusion (Figure 6F), our findings suggest that NEAT1 regulates pancreatic cancer progression via the microRNA-335-5p/c-met axis. This axis can be triggered by other extrinsic signaling from the tumor microenvironment or cancer cell intrinsic signaling. Although many factors contribute to the development of pancreatic cancer, our study provides a new approach to delay the development of pancreatic cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China-81301826 (to Jia Cao) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China-81472844 (to Lei-ming Xu).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Long J, Zhang Z, Liu Z, Xu Y, Ge C. Identification of genes and pathways associated with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by bioinformatics analyses. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1391–1397. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, Rosso T, Rota M, Levi F, La Vecchia C, Negri E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2015: does lung cancer have the highest death rate in EU women? Ann Oncol. 2015;26:779–786. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilimoria KY, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, Talamonti MS. National failure to operate on early stage pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246:173–180. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180691579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2140–2141. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1412266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrido-Laguna I, Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer: from state-of-the-art treatments to promising novel therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:319–334. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao W, Chan JY, Wong TS. Long non-coding RNA deregulation in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:405860. doi: 10.1155/2014/405860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding C, Cheng S, Yang Z, Lv Z, Xiao H, Du C, Peng C, Xie H, Zhou L, Wu J, Zheng S. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR promotes cell migration and invasion via down-regulation of RNA binding motif protein 38 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:4060–4076. doi: 10.3390/ijms15034060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizrahi I, Mazeh H, Grinbaum R, Beglaibter N, Wilschanski M, Pavlov V, Adileh M, Stojadinovic A, Avital I, Gure AO, Halle D, Nissan A. Colon Cancer Associated Transcript-1 (CCAT1) Expression in Adenocarcinoma of the Stomach. J Cancer. 2015;6:105–110. doi: 10.7150/jca.10568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malek E, Jagannathan S, Driscoll JJ. Correlation of long non-coding RNA expression with metastasis, drug resistance and clinical outcome in cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:8027–8038. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Chen Z, Wang X, Huang Z, He Z, Chen Y. Long non-coding RNA: a new player in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2013;6:37. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guru SC, Agarwal SK, Manickam P, Olufemi SE, Crabtree JS, Weisemann JM, Kester MB, Kim YS, Wang Y, Emmert-Buck MR, Liotta LA, Spiegel AM, Boguski MS, Roe BA, Collins FS, Marx SJ, Burns L, Chandrasekharappa SC. A transcript map for the 2.8-Mb region containing the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 locus. Genome Res. 1997;7:725–735. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.7.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.You J, Zhang Y, Liu B, Li Y, Fang N, Zu L, Li X, Zhou Q. MicroRNA-449a inhibits cell growth in lung cancer and regulates long noncoding RNA nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51(Suppl 3):e77–81. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.154055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choudhry H, Albukhari A, Morotti M, Haider S, Moralli D, Smythies J, Schodel J, Green CM, Camps C, Buffa F, Ratcliffe P, Ragoussis J, Harris AL, Mole DR. Tumor hypoxia induces nuclear paraspeckle formation through HIF-2alpha dependent transcriptional activation of NEAT1 leading to cancer cell survival. Oncogene. 2015;34:4546. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan LJ, Zhong TF, Tang RX, Li P, Dang YW, Huang SN, Chen G. Upregulation and clinicopathological significance of long non-coding NEAT1 RNA in NSCLC tissues. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:2851–2855. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.7.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SY, Kong WS, Cho JY. Identification of differentially expressed genes in Flammulina velutipes with anti-tyrosinase activity. Curr Microbiol. 2011;62:452–457. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9728-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng C, Xu Y, Xu L, Yu X, Cheng J, Yang L, Chen S, Li Y. Inhibition of long non-coding RNA NEAT1 impairs myeloid differentiation in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:693. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakravarty D, Sboner A, Nair SS, Giannopoulou E, Li R, Hennig S, Mosquera JM, Pauwels J, Park K, Kossai M, MacDonald TY, Fontugne J, Erho N, Vergara IA, Ghadessi M, Davicioni E, Jenkins RB, Palanisamy N, Chen Z, Nakagawa S, Hirose T, Bander NH, Beltran H, Fox AH, Elemento O, Rubin MA. The oestrogen receptor alpha-regulated lncRNA NEAT1 is a critical modulator of prostate cancer. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5383. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Q, Sun S, Yu W, Jiang J, Zhuo F, Qiu G, Xu S, Jiang X. Altered expression of long non-coding RNAs during genotoxic stress-induced cell death in human glioma cells. J Neurooncol. 2015;122:283–292. doi: 10.1007/s11060-015-1718-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engels BM, Hutvagner G. Principles and effects of microRNA-mediated post-transcriptional gene regulation. Oncogene. 2006;25:6163–6169. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng W, Liu T, Wan X, Gao Y, Wang H. MicroRNA-199a targets CD44 to suppress the tumorigenicity and multidrug resistance of ovarian cancer-initiating cells. FEBS J. 2012;279:2047–2059. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen KD, Goto S, Hsu LW, Lin TY, Nakano T, Lai CY, Chang YC, Weng WT, Kuo YR, Wang CC, Cheng YF, Ma YY, Lin CC, Chen CL. Identification of miR-27b as a novel signature from the mRNA profiles of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells involved in the tolerogenic response. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katakowski M, Zheng X, Jiang F, Rogers T, Szalad A, Chopp M. MiR-146b-5p suppresses EGFR expression and reduces in vitro migration and invasion of glioma. Cancer Invest. 2010;28:1024–1030. doi: 10.3109/07357907.2010.512596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scarola M, Schoeftner S, Schneider C, Benetti R. miR-335 directly targets Rb1 (pRb/p105) in a proximal connection to p53-dependent stress response. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6925–6933. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao J, Cai J, Huang D, Han Q, Yang Q, Li T, Ding H, Wang Z. miR-335 represents an invasion suppressor gene in ovarian cancer by targeting Bcl-w. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:701–706. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tome M, Lopez-Romero P, Albo C, Sepulveda JC, Fernandez-Gutierrez B, Dopazo A, Bernad A, Gonzalez MA. miR-335 orchestrates cell proliferation, migration and differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:985–995. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan Z, Xiong Y, Xu W, Gao J, Cheng Y, Wang Z, Chen F, Zheng G. Identification of hsa-miR-335 as a prognostic signature in gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu X, Newton RC, Scherle PA. Developing c-MET pathway inhibitors for cancer therapy: progress and challenges. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun YL, Liu WD, Ma GY, Gao DW, Jiang YZ, Liu Q, Du JJ. Expression of HGF and Met in human tissues of colorectal cancers: biological and clinical implications for synchronous liver metastasis. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:548–559. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gayyed MF, Abd El-Maqsoud NM, El-Hameed El-Heeny AA, Mohammed MF. c-MET expression in colorectal adenomas and primary carcinomas with its corresponding metastases. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;6:618–627. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2015.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HE, Kim MA, Lee HS, Jung EJ, Yang HK, Lee BL, Bang YJ, Kim WH. MET in gastric carcinomas: comparison between protein expression and gene copy number and impact on clinical outcome. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:325–333. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inokuchi M, Otsuki S, Fujimori Y, Sato Y, Nakagawa M, Kojima K. Clinical significance of MET in gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015;7:317–327. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v7.i11.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Afkhami M, Pejovic T. MET/HGF Signaling Pathway in Ovarian Carcinoma: Clinical Implications and Future Direction. Patholog Res Int. 2012;2012:960327. doi: 10.1155/2012/960327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otte A, Rauprich F, von der Ohe J, Yang Y, Kommoss F, Feuerhake F, Hillemanns P, Hass R. c-Met inhibitors attenuate tumor growth of small cell hypercalcemic ovarian carcinoma (SCCOHT) populations. Oncotarget. 2015;6:31640–31658. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Felix AS, Edwards RP, Stone RA, Chivukula M, Parwani AV, Bowser R, Linkov F, Weissfeld JL. Associations between hepatocyte growth factor, c-Met, and basic fibroblast growth factor and survival in endometrial cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:2004–2009. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akl MR, Ayoub NM, Ebrahim HY, Mohyeldin MM, Orabi KY, Foudah AI, El Sayed KA. Araguspongine C induces autophagic death in breast cancer cells through suppression of c-Met and HER2 receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:288–311. doi: 10.3390/md13010288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho-Yen CM, Jones JL, Kermorgant S. The clinical and functional significance of c-Met in breast cancer: a review. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:52. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0547-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han Y, Luo Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, Li M, Jiang Y. Hepatocyte growth factor increases the invasive potential of PC-3 human prostate cancer cells via an ERK/MAPK and Zeb-1 signaling pathway. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:753–759. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu J, Che L, Li L, Pilo MG, Cigliano A, Ribback S, Li X, Latte G, Mela M, Evert M, Dombrowski F, Zheng G, Chen X, Calvisi DF. Co-activation of AKT and c-Met triggers rapid hepatocellular carcinoma development via the mTORC1/FASN pathway in mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20484. doi: 10.1038/srep20484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guo S, Chen W, Luo Y, Ren F, Zhong T, Rong M, Dang Y, Feng Z, Chen G. Clinical implication of long non-coding RNA NEAT1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:5395–5402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao Y, Zeng F, Wu JY, Li HY, Fan JJ, Mai L, Zhang J, Ma DM, Li Y, Song FZ. MiR-335 inhibits migration of breast cancer cells through targeting oncoprotein c-Met. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:2875–2883. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2917-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen QY, Jiao DM, Yan L, Wu YQ, Hu HZ, Song J, Yan J, Wu LJ, Xu LQ, Shi JG. Comprehensive gene and microRNA expression profiling reveals miR-206 inhibits MET in lung cancer metastasis. Mol Biosyst. 2015;11:2290–2302. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00734d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu X, Fu C, Zhang L, Xu G, Wang S. MiRNAs associated polymorphisms in the 3’UTR of MET promote the risk of non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:1159–1167. doi: 10.1159/000430239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.