Abstract

The objective was to evaluate the efficacy of MP‐AzeFlu (Dymista®) vs fluticasone propionate (FP), (both 1 spray/nostril bid), in children with allergic rhinitis (AR). MP‐AzeFlu combines azelastine hydrochloride, FP and a novel formulation in a single spray. Children were randomized in a 3 : 1 ratio to MP‐AzeFlu or FP in this open‐label, 3‐month study. Efficacy was assessed in children aged ≥ 6 to <12 years (MP‐AzeFlu: n = 264; FP: n = 89), using a 4‐point symptom severity rating scale from 0 to 3 (0 = no symptoms; 3 = severe symptoms). Over the 3‐month period, MP‐AzeFlu‐treated children experienced significantly greater symptom relief than FP‐treated children (Diff: −0.14; 95% CI: −0.28, −0.01; P = 0.04), noted from the first day (particularly the first 7 days) and sustained for 90 days. More MP‐AzeFlu children achieved symptom‐free or mild symptom severity status, and did so up to 16 days faster than FP. MP‐AzeFlu provides significantly greater, more rapid and clinically relevant symptom relief than FP in children with AR.

Keywords: children, Dymista, fluticasone propionate, MP29‐02

Intranasal corticosteroids (INS) are recommended for the treatment of children with allergic rhinitis (AR) 1. However, they provide insufficient symptom control for many. Considering that AR is associated with poor asthma control 2, is a predictor of wheezing onset in school‐aged children 3 and poorer examination performance at school 4, it is important to get it under control. Unfortunately, AR is undiagnosed and undertreated in children 5.

MP‐AzeFlu (Dymista®, Meda, Solna, Sweden) comprises an intranasal antihistamine [azelastine hydrochloride (AZE)], an INS [fluticasone propionate (FP)] and a novel formulation in a single spray. Its efficacy and safety in adults and adolescent AR patients are well established 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, providing twice the overall nasal and ocular symptom relief as an INS or intranasal H1‐antihistamine, and more complete and rapid symptom control 6.

A lower treatment effect has been observed in paediatric allergy trials 11, 12, 13, possibly confounded by caregiver assessment 14, 15. The present study was primarily designed to assess the long‐term safety of MP‐AzeFlu (the results of which will be published in full elsewhere). Efficacy was assessed secondarily using a simple scoring system in an effort to minimize this confounder. The objective was to evaluate the efficacy of MP‐AzeFlu compared to FP in children aged ≥ 6 to <12 years, with AR.

Methods

Protocol

This was a prospective, randomized, active‐controlled, parallel‐group, 3‐month, open‐label safety trial in children with AR carried out at 42 investigational sites in the USA (March–October 2013). Ethics approval was obtained (Chesapeake Research Review Inc., Columbia, MD, USA), and the study conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice.

Participants

Male and female children aged ≥ 4 to <12 years (at screening visit), with a history of AR and who may benefit from treatment with MP‐AzeFlu, in the opinion of the investigator (based on medical history and physical examination), were included. These children were free of any disease or concomitant treatment that could have interfered with the interpretation of the study. Those with superficial or moderate nasal erosion, nasal mucosal ulceration or nasal septum perforation, who had nasal surgery within the last year, had significant pulmonary disease (excluding intermittent asthma), a hypersensitivity to AZE and/or FP or had used any investigation drug within 30 days prior to providing informed consent were excluded.

Planned interventions and timing

The study comprised a 2‐ to 30‐day lead‐in period, and a 3‐month treatment period, with study visits on Days, 1, 15, 30, 60 and 90. On Day 1, eligible children were randomized in a 3 : 1 ratio to either MP‐AzeFlu nasal spray (daily dose: AZE 548 μg, FP 200 μg) or FP nasal spray (Roxane; daily dose 200 μg), both administered as 1 spray/nostril bid.

Efficacy variables

Each child (or caregiver) completed a 24‐h reflective total symptom score (TSS) evaluation, scored daily in the morning during the lead‐in period and prior to the AM dose in the treatment period, in response to the question ‘how were your allergy symptoms over the past 24 h?'.

Allergy symptoms were scored from 0 (none/absent: no symptoms present), 1 (mild: symptoms clearly present, but minimal awareness and easily tolerated), 2 (moderate: definite awareness of symptoms that were bothersome but tolerable) to 3 (severe: hard to tolerate and caused interference with activities of daily living and/or sleeping).

Safety variables

Adverse events, nasal examination findings and vital signs were assessed. These data will be published in full separately 16.

Statistical analyses

Because it was a safety study, no inferential efficacy analysis were predefined in the protocol. The development focus of the paediatric programme was in the age range of 6‐ to 11‐year‐olds with some exploration in 4‐ to 5‐year‐olds. The mean change in TSS from baseline to each clinic visit was analysed post hoc for all randomised children aged ≥ 6 to <12 years old who took the drug. These data were analysed with a mixed‐model ancova (baseline as covariate; age class, visit and treatment as fixed effects). Missing data were not replaced. Time to response was analysed by Kaplan–Meier estimates and log‐rank tests. Response was defined as change in TSS from a baseline of 2 or 3 (i.e. moderate to severe) to a maximum of 1 (i.e. mild at most). For symptomatic children (i.e. baseline value ≥ 2), this is equivalent to a 50% reduction from baseline in AM + PM reflective total nasal symptom score (rTNSS) assessed in other studies 6, 7. Mean % of days with none to mild symptoms (i.e. TSS 0 or 1) was also calculated for both groups.

Results

Child disposition

A total of 405 children were randomized to MP‐AzeFlu or FP treatment. A total of 51 children (aged ≤ 5 years) were excluded from the efficacy analysis, as per the statistical plan efficacy was assessed in those aged ≥ 6 to <12 years. One child was excluded from the FP group (did not receive medication), yielding n = 264 and n = 89 in the MP‐AzeFlu and FP treatment groups, respectively. Time‐to‐response analysis was performed for symptomatic children (i.e. TSS above 2 at baseline; MP‐AzeFlu: n = 124; FP: n = 44). Of these, 15 children (6%) did not complete the study in the MP‐AzeFlu group (n = 4 AE, n = 1 treatment failure, n = 1 protocol violation, n = 2 noncompliance, n = 3 withdrawal, n = 2 lost to follow‐up and n = 2 other) and eight children (9%) failed to complete from the FP group (n = 3 AE, n = 1 protocol violation, n = 1 withdrawal, n = 2 lost to follow‐up, n = 1 other).

Child baseline and demographic information

Similar baseline characteristics were observed in the MP‐AzeFlu and FP groups (Table 1). The proportion of children with concomitant asthma was 4.86% and 4.90% in the MP‐AzeFlu and FP groups, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics in children aged ≥ 6 to <12 years

| Characteristic | All patients | Symptomatic patients (baseline TSS ≥ 2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MP‐AzeFlu (n = 264) | FP (n = 89) | MP‐AzeFlu (n = 124) | FP (n = 44) | |

| Age, n (%) | ||||

| ≥6 to <9 years | 128 (48.5) | 44 (49.4) | 63 (50.8) | 21 (47.7) |

| ≥9 to <12 years | 136 (51.5) | 45 (50.6) | 61 (49.2) | 23 (52.3) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 158 (59.9) | 46 (41.7) | 81 (65.3) | 20 (45.5) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Black/African American | 41 (15.5) | 16 (18.0) | 20 (16.1) | 7 (15.9) |

| White | 200 (75.8) | 67 (75.3) | 99 (79.8) | 35 (79.5) |

| Other | 23 (8.7) | 6 (6.7) | 5 (4.0) | 2 (4.5) |

| TSS, mean (SD) | 1.72 ± 0.76 | 1.77 ± 0.73 | 2.40 ± 0.35 | 2.36 ± 0.35 |

| Range | 0–3 | 0–3 | ||

TSS, total symptom score; SD, standard deviation.

MP‐AzeFlu: novel intranasal formulation of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate (FP) in a single spray.

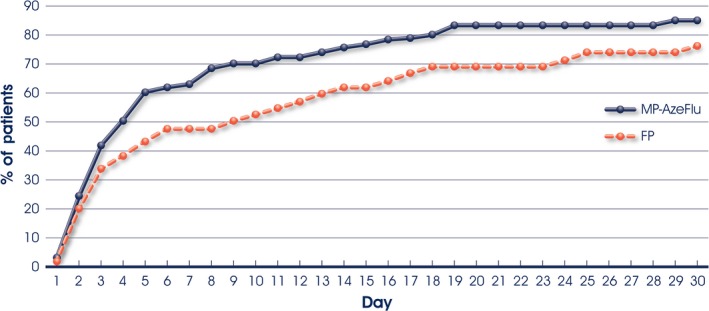

Reflective total symptom score

Children treated with MP‐AzeFlu experienced a −0.68 pt reduction in TSS, significantly greater than that afforded by FP (−0.54 pt reduction; Diff: −0.14; 95% CI: −0.28,−0.01; P = 0.0410). The superiority of MP‐AzeFlu was noted from the first day of assessment, particularly during the first 7 days of treatment, and sustained for 90 days. More children treated with MP‐AzeFlu (eight of 10 children) achieved symptom‐free or at most mild symptom severity in the first month of treatment, and did so up to 16 days faster than FP (Figure 1). More children treated with MP‐AzeFlu experienced none or mild symptoms during the 3‐month study period [73.4% (SD 28.8)] than those treated with FP [66.0% (SD 34.2)].

Figure 1.

Time to achieve at most mild allergic rhinitis symptom severity in children with moderate‐to‐severe symptoms at baseline during the first month of treatment with either MP‐AzeFlu (n = 124) or fluticasone propionate (FP: n = 44), both 1 spray/nostril bid, in children aged ≥6 to 12 years. Time to response was analysed by Kaplan–Meier estimates and log‐rank tests.

Discussion

MP‐AzeFlu provided significantly better AR symptom relief than FP in children aged ≥ 6 to <12 years, the first time the efficacy of INS has been exceeded in this population. Effect size was similar to that seen in adult and adolescent SAR patients 6. In the current study, MP‐AzeFlu induced a −0.68 point TSS reduction from baseline, a −0.14 point difference vs FP, corresponding to a −5.44 point reduction and −1.12 point difference, respectively, on the 24‐point rTNSS scale used in the adult/adolescent SAR trials 6, 7. Furthermore, approximately eight of 10 children treated with MP‐AzeFlu in the current study achieved symptom‐free or at most mild symptom severity in the first month of treatment, and did so up to 16 days faster than FP; comparable to the proportion of adult and adolescent patients with perennial AR over the same time period 8, which should positively influence concordance with MP‐AzeFlu therapy. Approximately three quarters of children treated with MP‐AzeFlu experienced no or only mild symptoms during the 3‐month treatment period. Achieving AR symptom control (and rapidly) is particularly important in children due to the negative impact of uncontrolled disease on school performance 4 and on asthma control 2.

Previously, MP‐AzeFlu has demonstrated statistical superiority over placebo in children (aged ≥ 6 to <12 years) with moderate/severe SAR 17, 18, and as the extent of child self‐rating increased, so too did the treatment difference between MP‐AzeFlu and placebo. However, efficacy was assessed using an endpoint designed for adolescent/adult populations (i.e. by rTNSS), in line with regulatory requirement, and could be rated by either children or caregivers. The present study was designed to minimize assessment effort and bias using a much simplified and child‐friendly efficacy assessment tool. Using this simple 4‐point rating scale significant superiority of MP‐AzeFlu was detected vs an active treatment.

Limitations of the current study include the open‐label design and that it was primarily a safety study, with no assessment of quality of life or inferential efficacy analysis predefined in the protocol. However, the applied statistical method used to assess efficacy is straightforward and standard. In addition, the low number of clinic visits and the simple method of efficacy assessment make this trial quite pragmatic in nature and representative of response achievable in real life. Use of the simple 4‐point severity scoring system was sensitive enough to detect difference in efficacy between two active treatments. MACVIA ARIA recommends another simple tool, the visual analogue scale, to assess disease control and guide treatment decisions 19. These tools should be strongly considered for inclusion in AR trials in children.

In conclusion, MP‐AzeFlu provides significantly greater, more complete and more rapid AR symptom control than FP in children (aged ≥ 6–12 years) and has been granted approval for use in this age group by the FDA. Efficacy assessment in AR trials in children might be improved by use of simple tools.

Conflict of interest

All authors are members of Meda's Dymista Paediatric Advisory Board.

Authors' contributions

All authors have contributed to acquisition of data and/or interpretation of data, drafting of the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and have provided final approval for this version to be published.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Ruth Murray (Ireland) for assistance in editing this manuscript.

Berger W, Bousquet J, Fox AT, Just J, Muraro A, Nieto A, Valovirta E, Wickman M, Wahn U. MP‐AzeFlu is more effective than fluticasone propionate for the treatment of allergic rhinitis in children. Allergy 2016; 71: 1219–1222

Edited by: Wytske Fokkens

References

- 1. Brozek JL, Bousquet J, Baena‐Cagnani CE, Bonini S, Canonica GW, Casale TB et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines: 2010 revision. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:466–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Groot EP, Nijkamp A, Duiverman EJ, Brand PL. Allergic rhinitis is associated with poor asthma control in children with asthma. Thorax 2012;67:582–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rochat MK, Illi S, Ege MJ, Lau S, Keil T, Wahn U et al. Allergic rhinitis as a predictor for wheezing onset in school‐aged children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:1170–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walker S, Khan‐Wasti S, Fletcher M, Cullinan P, Harris J, Sheikh A. Seasonal allergic rhinitis is associated with a detrimental effect on examination performance in United Kingdom teenagers: case–control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:381–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruokonen M, Kaila M, Haataja R, Korppi M, Paassilta M. Allergic rhinitis in school‐aged children with asthma – still under‐diagnosed and under‐treated? A retrospective study in a children's hospital. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2010;21:e149–e154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meltzer E, Ratner P, Bachert C, Carr W, Berger W, Canonica GW et al. Clinically relevant effect of a new intranasal therapy (MP29‐02) in allergic rhinitis assessed by responder analysis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2013;161:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carr W, Bernstein J, Lieberman P, Meltzer E, Bachert C, Price D et al. A novel intranasal therapy of azelastine with fluticasone for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:1282–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Price D, Shah S, Bhatia S, Bachert C, Berger W, Bousquet J et al. A new therapy (MP29‐02) is effective for the long‐term treatment of chronic rhinitis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2013;23:495–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Klimek L, Bachert C, Mosges R, Munzel U, Price D, Virchow JC et al. Effectiveness of MP29‐02 for the treatment of allergic rhinitis in real‐life: results from a noninterventional study. Allergy Asthma Proc 2015;36:40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berger WE, Shah S, Lieberman P, Hadley J, Price D, Munzel U et al. Long‐term, randomized safety study of MP29‐02 (a novel intranasal formulation of azelastine hydrochloride and fluticasone propionate in an advanced delivery system) in subjects with chronic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014;2:179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meltzer EO, Lee J, Tripathy I, Lim J, Ellsworth A, Philpot E. Efficacy and safety of once‐daily fluticasone furoate nasal spray in children with seasonal allergic rhinitis treated for 2 wk. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009;20:279–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Storms WW, Segall N, Mansfield LE, Amar NJ, Kelley L, Ding Y et al. Efficacy and safety of beclomethasone dipropionate nasal aerosol in pediatric patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2013;111:408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maspero JF, Walters RD, Wu W, Philpot EE, Naclerio RM, Fokkens WJ. An integrated analysis of the efficacy of fluticasone furoate nasal spray on individual nasal and ocular symptoms of seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc 2010;31:483–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Danell CS, Bergstrom A, Wahlgren CF, Hallner E, Bohme M, Kull I. Parents and school children reported symptoms and treatment of allergic disease differently. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:783–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dahlen E, Almqvist C, Bergstrom A, Wettermark B, Kull I. Factors associated with concordance between parental‐reported use and dispensed asthma drugs in adolescents: findings from the BAMSE birth cohort. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2014;23:942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berger W, Ratner P, Soteres D. Randomized trial of the safety of MP29‐02* compared with fluticasone propionate nasal spray in children aged =4 years to <12 years with allergic rhinitis. Presented at the Paediatric Allergy & Asthma Congress, Berlin, Germany 15‐17 Oct 2015 Available at http://www.eaaci-paam2015.com/PAAM2015-Abstracts/abstracts/PAAM_2015_PP76.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berger W, Meltzer EO, Amar NJ, Muraro A, Wickman M, Just J et al. MP‐AzeFlu for nasal and ocular symptom relief in children with seasonal allergic rhinitis: importance of patient symptom assessment. Accepted by European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Congress 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18. Berger W, Meltzer EO, Amar NJ, Muraro A, Wickman M, Just J et al. MP‐AzeFlu and time to clinically‐meaningful response in the treatment of children with seasonal allergic rhinitis: importance of patient symptom assessment. Accepted by European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology Congress 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19. Bousquet J, Schunemann HJ, Fonseca J, Samolinski B, Bachert C, Canonica GW et al. MACVIA‐ARIA Sentinel NetworK for allergic rhinitis (MASK‐rhinitis): the new generation guideline implementation. Allergy 2015;70:1372–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]