Abstract

Neurovascular coupling supports brain metabolism by matching focal increases in neuronal activity with local arteriolar dilation. Previously, we demonstrated that an emergence of spontaneous endfoot high-amplitude Ca2+ signals (eHACSs) caused a pathologic shift in neurovascular coupling from vasodilation to vasoconstriction in brain slices obtained from subarachnoid hemorrhage model animals. Extracellular purine nucleotides (e.g., ATP) can trigger astrocyte Ca2+ oscillations and may be elevated following subarachnoid hemorrhage. Here, the role of purinergic signaling in subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced eHACSs and inversion of neurovascular coupling was examined by imaging parenchymal arteriolar diameter and astrocyte Ca2+ signals in rat brain slices using two-photon fluorescent and infrared-differential interference contrast microscopy. We report that broad-spectrum inhibition of purinergic (P2) receptors using suramin blocked eHACSs and restored vasodilatory neurovascular coupling after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Importantly, eHACSs were also abolished using a cocktail of inhibitors targeting Gq-coupled P2Y receptors. Further, activation of P2Y receptors in brain slices from un-operated animals triggered high-amplitude Ca2+ events resembling eHACSs and disrupted neurovascular coupling. Neither tetrodotoxin nor bafilomycin A1 affected eHACSs suggesting that purine nucleotides are not released by ongoing neurotransmission and/or vesicular release after subarachnoid hemorrhage. These results indicate that purinergic signaling via P2Y receptors contributes to subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced eHACSs and inversion of neurovascular coupling.

Keywords: Subarachnoid hemorrhage, neurovascular coupling, astrocyte endfeet, astrocyte Ca2+ signaling, purinergic receptors

Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality against which current therapeutic options have limited efficacy.1 Perfusion deficits within brain cortex are generally appreciated to contribute to the development of delayed neurological deficits that jeopardize the survival and long-term outcome of SAH patients.2,3 The occurrence of multifocal cortical infarcts in the days to weeks after the initial aneurysm rupture reflect this diffuse impact of SAH on the brain microcirculation.4–6 However, the signaling pathways linking SAH to decreased cortical blood flow are not fully understood.

Intra-cerebral (parenchymal) arterioles form a natural bottleneck to cortical perfusion, and as they enter the brain they become encased by astrocyte endfeet.7–9 In the healthy brain, neuronal activity-dependent elevation of endfoot Ca2+ can trigger parenchymal arteriolar dilation and enhanced local cerebral blood flow (CBF).10 Several studies have provided evidence that increased neuronal activity triggers a rise in astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ that may be associated with release of vasoactive substances (e.g., K+ ions) into the restricted perivascular space between the endfeet and vascular smooth muscle leading to vasodilation.11,12 However, increased CBF in response to neuronal activity may also be triggered by pathways independent of elevations in astrocyte Ca2+ (e.g., nitric oxide release from interneurons13,14).

The brain’s functional hyperemic response, also referred to as neurovascular coupling (NVC), ensures adequate delivery of O2 and other nutrients to areas of the brain with increased metabolic demand. In brain slices from SAH model animals, however, the polarity of the vascular response to neuronal activation is shifted from vasodilation to vasoconstriction.15,16 This inversion of NVC may contribute to the development of focal ischemia after SAH by restricting blood flow to active brain regions. Recent evidence indicates that altered astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in the form of the emergence of spontaneous endfoot high-amplitude Ca2+ signals (eHACSs) is associated with SAH-induced inversion of NVC.15,17 However, the cellular basis underlying the generation of eHACSs after SAH has not been determined.

The goal of this study was to determine whether enhanced purinergic signaling underlies the generation of eHACSs and inversion of NVC after SAH. Astrocytes broadly express both ionotropic (P2X) and metabotropic (P2Y) purinergic receptors that trigger a rise in intracellular Ca2+ when activated.18,19 Increased signaling via extracellular purine nucleotides (e.g., ATP) is common after brain injury, including aneurysmal SAH18,20 and elevated levels of ATP have been reported in cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) after SAH.20,21 Further, purinergic signaling has been reported to cause aberrant astrocyte Ca2+ elevations that are associated with vascular instability and disrupted NVC in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease.22,23

Here, using combined infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) and two-photon fluorescence microscopy, we report that inhibition of Gq-coupled P2Y purinergic receptors abolished eHACSs and restored vasodilatory NVC in brain slices obtained from SAH model animals. However, block of P2Y receptors did not affect astrocyte Ca2+ signaling in brain slices from control animals and inhibition of ionotropic P2X receptors did not alter Ca2+ signaling in either the control or SAH group. Further, we show that activation of P2Y receptors in brain slices from control animals mimicked SAH by causing the emergence of high-amplitude endfoot Ca2+ events resembling eHACSs and disrupting NVC responses. This work identifies astrocyte P2Y receptors as an important component of SAH pathology and a novel potential therapeutic target in the treatment of micro-vascular dysfunction following cerebral aneurysm rupture.

Materials and methods

Rat SAH model

The double-injection cisterna magna model was used to mimic aneurysmal SAH, as previously described.15,24 Briefly, autologous, unheparanized arterial blood (0.5 mL drawn from the tail artery) was injected into the cisterna magna of isoflurane-anesthetized Sprague-Dawley rats (male, 10–12 weeks old, Charles River Laboratories). This surgical procedure was repeated following a 24 h recovery period. Sham-operated animals underwent identical surgical procedures except that artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) was injected rather than whole blood. Sham and SAH model animals were euthanized at day 2 (48 h) following the first injection. Day 2 SAH was chosen because we previously found that at this time point, the vast majority of astrocyte endfeet (∼80%) exhibit eHACSs; defined as spontaneous (i.e., non-stimulated) events with endfoot Ca2+ exceeding 500 nM.17 Day 2 SAH also coincided with the highest percentage (100%) of brain slices exhibiting inversion of NVC. Un-operated animals served as the control group. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (eighth edition, 2011), ARRIVE (Animals in Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments) guidelines, and followed protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Vermont.

Simultaneous measurement of arteriolar diameter and astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ in cortical brain slices

Brain slice preparation

Animals were euthanized by decapitation while under deep anesthesia with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg). Coronal brain slices (160 µm thick) were cut in ice-cold, aerated (5% CO2/95% O2) aCSF using a Leica VT1000S vibratome. Brain slices were incubated with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, Fluo-4 AM (10 µM) for 1.5 h at 29℃ in aerated aCSF containing 0.04% pluronic acid. Under these conditions, Fluo-4 preferentially loads into astrocytes.25 After incubating with Fluo-4 AM, brain slices were rinsed and maintained in aerated aCSF at room temperature prior to imaging.

Simultaneous recordings of arteriolar diameter and endfoot Ca2+

A BioRad Radiance multi-photon imaging system (excitation wavelength: 820 nm, fluorescent bandpass filter: 575/150 nm, sampling frequency ∼1 Hz) coupled to a Coherent Chameleon Ti-Sapphire laser was used to simultaneously obtain IR-DIC and fluorescent brain slice images (512 pixels × 512 pixels, 61 µm × 61 µm). Arteriolar segments (cortical layer 2/3, middle cerebral artery territory) that were surrounded by Fluo-4-loaded endfeet and at a depth of 20–50 µm into the cut surface of the brain slice were chosen for study. Spontaneous endfoot Ca2+signals were recorded in the absence of stimulation. NVC was initiated using electrical field stimulation (EFS; 50 Hz, 20 V, 0.3 ms alternating square pulse, 3 s duration) applied using a Grass Technologies 24 S stimulator to trigger neuronal action potentials.15,17,26 For EFS, a pair of platinum wire electrodes (2 mm apart) was lowered onto the edge of the slice surface. The electrodes were oriented such that the wires were on opposite sides of the arteriole, which was positioned directly between the two electrodes. We have previously shown that using these parameters, EFS-evoked endfoot Ca2+ elevations and associated changes in arteriolar diameter are abolished in the presence of tetrodotoxin15 indicating that these phenomena depend on the generation of neuronal action potentials. Throughout all recordings, brain slices were continually superfused with aerated aCSF (32–34℃) containing the thromboxane A2 analog, 9,11 di-dideoxy-11α,9α-epoxymethanoprostaglandin F2α (U46619, 100 nM) to induce a comparable intermediate level of arteriolar tone in brain slices from control and SAH animals.15,17 Ionomycin (10 µM) and CaCl2 (20 mM) were added to the bath at the end of each experiment to obtain maximal fluorescence.

Analysis of arteriolar diameter

Intraluminal arteriolar diameter was measured from IR-DIC images at three evenly spaced points along a 10 µm length of segment exhibiting the greatest diameter change to EFS. Diameter change is expressed as the percent increase or decrease from baseline (determined from 10 s prior to EFS and averaged for the 3 points of measurement). Diameters were measured manually using custom software, SparkAn, written by Dr Adrian D. Bonev at the University of Vermont (Burlington, VT).

Analysis of endfoot Ca2+

A region of interest (ROI, 1.2 µm × 1.2 µm) was placed within an endfoot that was either (1) adjacent to the arteriolar segment used to measure diameter during EFS or (2) exhibiting spontaneous Ca2+ events in the absence of stimulation. Spontaneous Ca2+ events were defined by the following criteria: (1) ≥ 30% increase in fluorescent intensity for at least two consecutive images and (2) multiple events during a 4-min recording period.17 The recording period of 4 min was chosen as it provides sufficient time to capture endfoot Ca2+ activity without the negative consequences of photo-bleaching, photo-damage, and/or gradual drift out of the focal plane. Endfoot Ca2+ concentrations were estimated using the maximal fluorescence method.12,27

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n: the number of observations, N: the number of animals). Analysis was performed by investigators that perform the studies, no blinding was done. Student’s two-tailed paired t test was used for comparisons between two groups.

Reagents

U46619 and ionomycin were obtained from Calbiochem (EMD Millipore, Chicago, IL). Fluo-4 AM and pluronic acid were obtained from Invitrogen (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR). All P2 receptor antagonists were obtained from Tocris (Bio-techne, Minneapolis, MN). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The composition of aCSF (in mM) was: 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 18 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 glucose, and 0.4 ascorbic acid.

Results

Purinergic receptor inhibition abolishes SAH-induced eHACSs

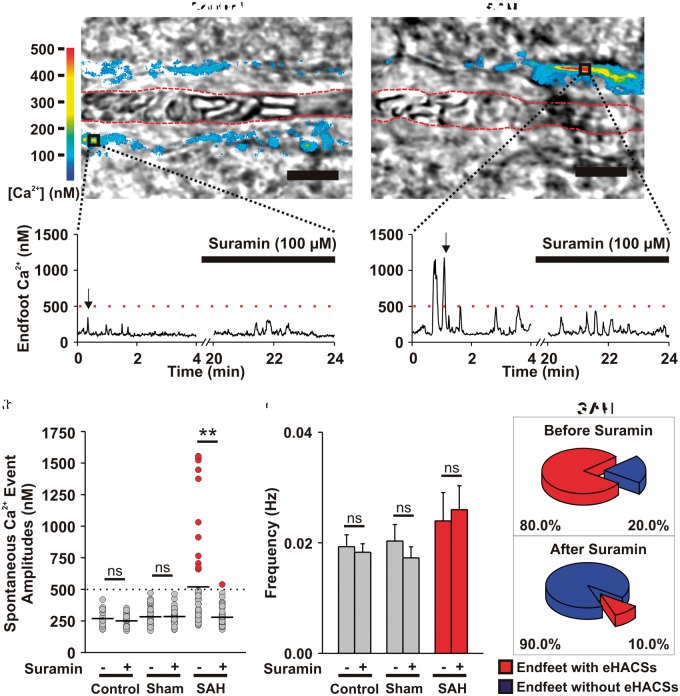

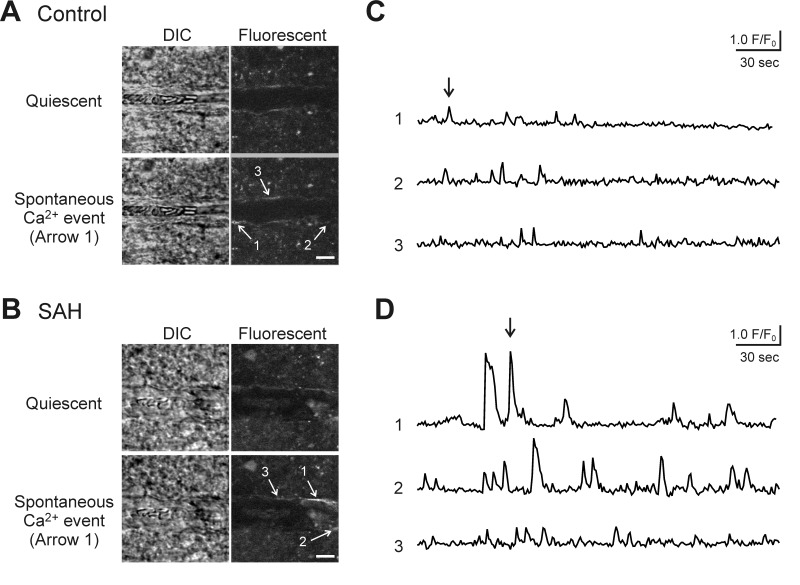

The role of purinergic signaling in the generation of SAH-induced astrocyte eHACSs was explored in brain slices using the broad-spectrum purinergic receptor antagonist, suramin (100 μM) (Figure 1). In brain slices from un-operated (control) and sham-operated animals, only spontaneous Ca2+ signals with amplitudes of less than 500 nM were observed in Fluo-4-loaded endfeet using two-photon imaging (Figure 1(a) and (b); Supplemental Figure 1). Suramin had no effect on the amplitude (Figure 1(b)) or frequency (Figure 1(c)) of endfoot Ca2+ signals in control (n = 8 endfeet from 5 brain slices, N = 4) and sham-operated animals (n = 8 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 3). In brain slices from SAH model animals, most endfeet exhibited a mix of “control-like” Ca2+ signals (amplitudes < 500 nM) and high-amplitude (>500 nM) Ca2+ signals “eHACSs” as previously described (Figure 1(d)).15,17 Suramin treatment nearly abolished SAH-induced eHACSs (Figure 1(b) and (c)), but did not affect lower amplitude “control-like” events or the overall frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ signals (n = 10 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5). As NVC responses15 and spontaneous Ca2+ event amplitudes were comparable between the control and sham-operated groups (268 ± 11 nM vs. 283 ± 12 nM, respectively; two-tailed unpaired t test, p = 0.367), un-operated animals served as controls for subsequent experiments. These results suggest that purinergic signaling is involved in SAH-induced eHACSs, but not in “control-like” endfoot Ca2+ events.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of purinergic signaling with suramin blocks SAH-induced eHACSs. (a) Upper panels: Brain slice images with parenchymal arterioles and overlapping pseudocolor-mapped fluorescent Ca2+ levels in surrounding astrocyte endfeet obtained using simultaneous IR-DIC and two photon microscopy. These images capture peak Ca2+ levels during a typical event in a brain slice from a control animal (<500 nM, left) and a high-amplitude “eHACS” in a brain slice from an SAH animal (≥500 nM, right). Red-dashed lines depict arteriolar lumen. Scale bar is 10 µm. Lower panels: spontaneous fluctuations in intracellular Ca2+ (i.e. spontaneous Ca2+ events) in the absence and presence of suramin recorded from the regions of interest corresponding to the black boxes in the upper panel images. Black arrows represent the time point when upper panel images were obtained. (b) Distribution of spontaneous Ca2+ event amplitudes recorded in brain slices from control (n = 8 endfeet from 5 brain slices, N = 4), sham-operated (n = 8 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 3), and SAH model animals (n = 10 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5) before and after treatment with suramin. Horizontal black lines represent the mean amplitudes of all events in the group. eHACSs (red dots, peaks ≥ 500 nM) are nearly abolished in brain slices from SAH animals treated with suramin. Two-tailed paired t test, **p < 0.01, ns: not significant. (c) Summary data showing the effect of suramin on the frequency of spontaneous endfoot Ca2+ events in brain slices from control, sham-operated, and SAH model animals. Two-tailed paired t test, ns: not significant. (d) Summary indicating the incidence of endfeet with eHACSs before and after treatment with suramin. These data were obtained from brain slices of SAH animals, as eHACSs were not observed in brain slices from control or sham-operated animals.

Suramin restores vasodilatory NVC after SAH

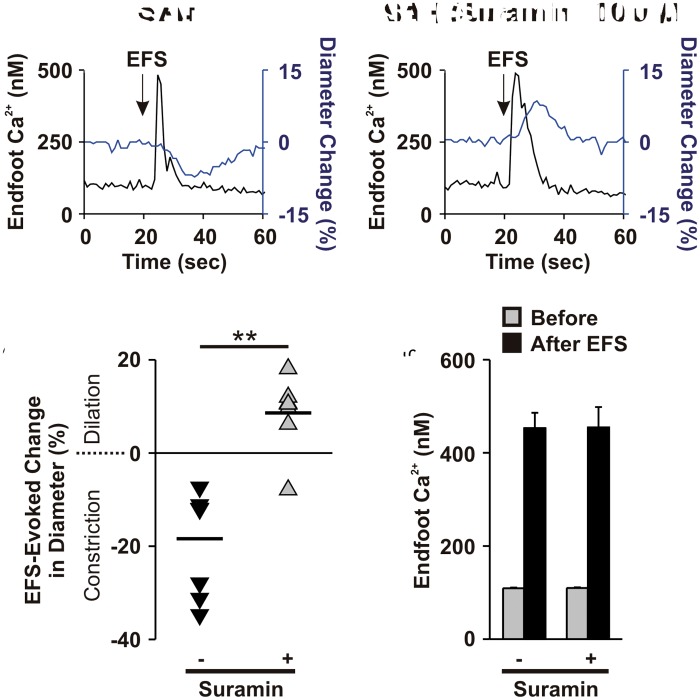

As the emergence of eHACSs has been linked to inversion of NVC after SAH,15,17 we examined whether disruption of eHACSs with suramin could restore vasodilatory NVC in brain slices from SAH animals. In the absence of suramin, generation of neuronal action potentials using EFS caused parenchymal arteriolar constriction in 100% of SAH brain slices (n = 7/7 brain slices, N = 6) (Figure 2(a)). Remarkably, suramin restored arteriolar dilation to EFS in the majority of brain slices (n = 6/7 brain slices, N = 6) (Figure 2(b)). Suramin, however, did not alter the amplitude of EFS-evoked endfoot Ca2+ transients (Figure 2(c)) or arteriolar diameter before EFS (6.5 ± 1.1 µm before suramin vs. 6.2 ± 1.0 µm after suramin, two-tailed paired t test, p = 0.53, n = 7 endfeet from 7 brain slices, N = 6). In time control studies, eHACSs were observed in 80% of (n = 4/5 endfeet from 3 brain slices, N = 3) endfeet in the initial recordings, and in 100% of endfeet (n = 5/5 endfeet from 3 brain slices, N = 3) after 20 min. Moreover, the mean amplitudes of all events were similar between groups (376 ± 42 nM initial vs. 390 ± 27 nM after 20 min), as well as the overall frequency of events (0.026 ± 0.006 initial vs. 0.032 ± 0.01 after 20 min, n = 5 endfeet from 3 brain slices, N = 3). These data demonstrate that both the inversion of NVC and the presence of eHACSs in astrocyte endfeet surrounding parenchymal arterioles after SAH are dependent upon purinergic signaling.

Figure 2.

Blocking eHACSs with suramin restores vasodilator NVC after SAH. (a) Representative traces showing EFS-induced elevation of endfoot Ca2+ (black lines) and subsequent changes in arteriolar diameter (blue lines). (b) Summary scatter plot demonstrating EFS-evoked changes in arteriolar diameter before (black triangles) and after (gray triangles) treatment with suramin (n = 7 brain slices, N = 6). Two-tailed paired t test, **p < 0.01. (c) Summary data showing EFS-evoked changes in endfoot Ca2+ in brain slices from SAH animals before and after treatment with suramin (n = 7 brain slices, N = 6).

P2Y receptors mediate SAH-induced eHACSs

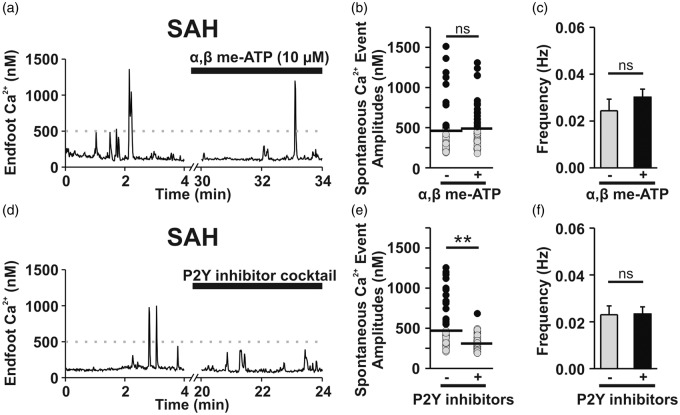

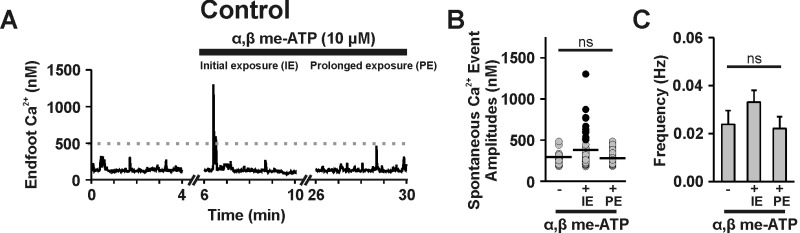

Purinergic (P2) receptors are broadly classified into two subtypes: ligand-gated, Ca2+-permeable ion channels (i.e., P2X receptors) and metabotropic G-protein coupled (P2Y) receptors.28 P2X receptors and P2Y receptors can be distinguished using α, β-methylene-ATP (α, β me-ATP), a selective P2X agonist that rapidly desensitizes P2X but not P2Y receptors.29 In brain slices from un-operated control animals, α, β me-ATP (10 μM) triggered an increase in endfoot Ca2+ signaling within the first 5 min of exposure, suggesting that functional P2X receptors are expressed on the endfeet (Supplemental Figure 2(a) to (c); n = 7 endfeet from 5 brain slices, N = 4). However, after 25 min, endfoot Ca2+ signals had normalized, indicating that P2X receptors had become desensitized (Supplemental Figure 2(a) to (c)). Under these conditions (i.e., 25 min treatment of α, β me-ATP) to desensitize P2X receptors, the incidence of eHACSs and the overall frequency of endfoot Ca2+ signals (Figure 3(a) to (c), n = 5 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 3) were unaltered, suggesting that P2X receptors are not involved in the generation of eHACSs after SAH.

Figure 3.

P2Y receptor activation mediates SAH-induced eHACSs. (a–c) P2X receptor desensitization did not alter the incidence of SAH-induced eHACSs. (a) Representative trace depicting spontaneous Ca2+ activity recorded from a brain slice of a SAH animal before and after treatment with, α, β-meATP (10 µM, 25 min), an ATP analogue that rapidly desensitizes P2X receptors. (b) Distribution of all spontaneous Ca2+ event amplitudes recorded in brain slices from SAH animals before and after treatment with α, β-meATP. Astrocyte endfeet still exhibited eHACSs (black dots) following desensitization of P2X receptors (n = 5 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 3). Horizontal black lines indicate the mean amplitudes of all events. (c) Summary data showing the frequency of endfoot Ca2+ events in the presence or absence of α, β-meATP (n = 5 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 3). (d–f) Blockade of P2Y receptors abolished SAH-induced e-HACSs. (d) Representative trace of spontaneous Ca2+ activity recorded from a SAH brain slice before and after treatment with a P2Y inhibitor cocktail containing MRS 2179 (30 µM, P2Y1 antagonist), AR-C 118925XX (10 µM, P2Y2 antagonist), MRS 2578 (30 µM, P2Y6 antagonist), and NF 340 (30 µM, P2Y11 antagonist). (e) Distribution of all spontaneous Ca2+ event amplitudes recorded from SAH animals before and after treatment with the P2Y inhibitor cocktail (n = 13 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5). Note that the P2Y inhibitor cocktail selectively abolished eHACSs (black dots). Horizontal black lines indicate the mean amplitudes of all events. Two-tailed paired t test, **p < 0.01. (f) Summary data showing the frequency of spontaneous endfoot Ca2+ events in the presence or absence of the P2Y inhibitor cocktail (n = 13 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5). Two-tailed paired t test, ns: not significant.

To examine the involvement of P2Y receptors in SAH-induced eHACSs, brain slices from SAH animals were treated with a cocktail of inhibitors targeting Gq-coupled P2Y receptors. This inhibitor cocktail contained MRS 2179 (30 µM, P2Y1 antagonist), AR-C 118925XX (10 µM, P2Y2 antagonist), MRS 2578 (30 µM, P2Y6 antagonist), and NF 340 (30 µM, P2Y11 antagonist).30–32 This combination of P2Y inhibitors blocked eHACSs, but did not alter “control-like” events or the overall frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ signals (Figure 3(d) to (f), n = 13 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5). Interestingly, treatment of SAH brain slices with the phospholipase C inhibitor, U73122 (30 μM, 30 min) abolished both SAH-induced eHACSs and all “control-like” events (0.026 ± 0.007 Hz to 0 Hz, n = 5 endfeet from 3 brain slices, N = 3). Spontaneous endfoot Ca2+ signals were also abolished by U73122 in brain slices from un-operated control animals (0.022 ± 0.004 Hz to 0 Hz, n = 7 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 3); however, the inactive analog, U73343 (30 μM, 30 min), was without effect (0.019 ± 0.004 Hz to 0.019 ± 0.04 Hz, n = 4 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 4). Together, these data indicate that Gq-coupled P2Y receptor signaling contributes to the generation of SAH-induced eHACSs and that non-purinergic Gq-coupled receptors mediate “control-like” endfoot Ca2+ signals.

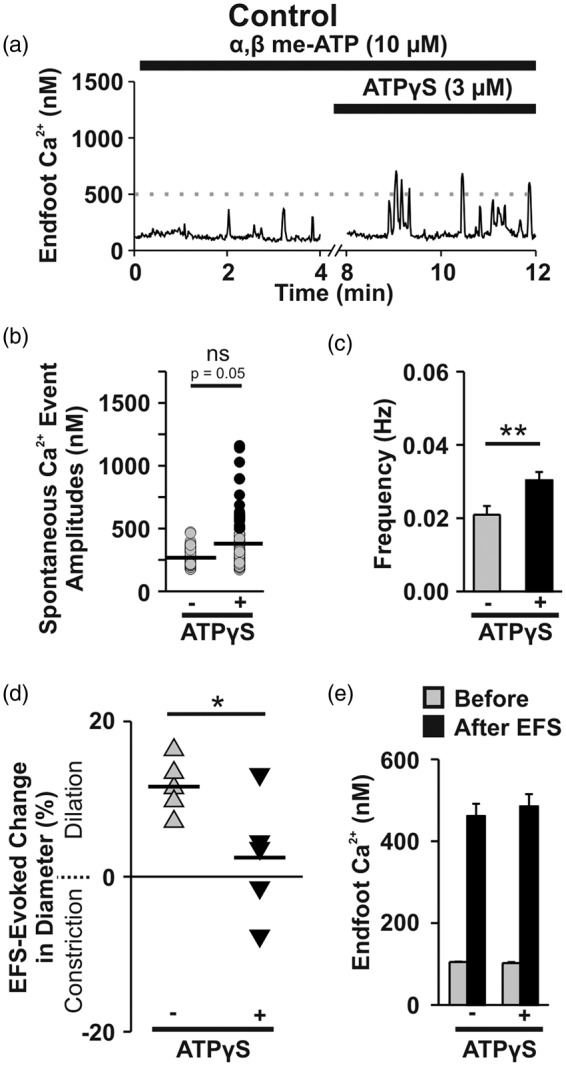

Activation of P2Y receptors in brain slices from control animals mimics SAH

We next sought to determine whether pharmacologic activation of P2Y receptors could mimic SAH in brain slices from un-operated animals. To obviate the potentially confounding effects mediated by P2X receptors, brain slices were pre-treated with α, β me-ATP (10 μM, 25 min) to desensitize P2X receptors. In the presence of α, β me-ATP, Ca2+ signals in endfeet from control animals were unaltered (i.e., all peaks <500 nM). Subsequent treatment of brain slices with the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog, ATPγS (3 μM), triggered an emergence of high-amplitude Ca2+ signals that were comparable to SAH-induced eHACSs (Figure 4(a) to (c), n = 13 endfeet from 8 brain slices, N = 5). In the absence of EFS, parenchymal arterioles in these brain slices typically exhibit minor fluctuations in diameter ( ± 1–2%, or < 1 µm). We attempted, but could not discern, a correlation between individual spontaneous Ca2+ events in endfeet and arteriolar diameter fluctuations either in the absence and presence of ATPγS. Further, there was no effect of ATPγS on arteriolar diameter prior to EFS (6.1 ± 0.9 µm before ATPγS vs. 6.2 ± 0.9 µm after ATPγS, two-tailed paired t test, p = 0.64, n = 5 brain slices, N = 4). However, activating P2Y receptors did cause a marked disruption of NVC in brain slices of control animals. In the presence of α, β me-ATP alone (10 μM, 25 min), focal activation of neurons using EFS caused the anticipated arteriolar dilation in 100% of brain slices (n = 5/5 brain slices, N = 4) (Figure 4(d)). However, subsequent treatment with ATPγS (3 μM, 10 min) to activate P2Y receptors caused inversion of NVC (i.e., EFS-induced vasoconstriction) in two of five brain slices and attenuated the vasodilatory responses in the other three brain slices (Figure 4(d)), with no effect on EFS-evoked endfoot Ca2+ transients (Figure 4(e)). In brain slices pretreated with α, β me-ATP and the P2 receptor antagonist, suramin, ATPγS failed to elicit an increase in endfoot Ca2+ signaling (Supplemental Figure 3(a) to (c), n = 7 endfeet from 5 brain slices, N = 4). These data suggest that functional P2Y receptors are present on astrocyte endfeet in healthy control animals and that activating these receptors generates Ca2+ signals resembling SAH-induced eHACSs that disrupt NVC.

Figure 4.

Activation of P2Y receptors in brain slices from control animals mimics SAH. (a) Representative trace showing the effect of ATPγS, a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog, on spontaneous Ca2+ activity in a brain slice obtained from an un-operated control animal. To desensitize P2X receptors, α, β-meATP was included in the superfusate for 25 min prior to the application of ATPγS and maintained throughout the depicted experimental protocol. (b) Distribution of all spontaneous Ca2+ event amplitudes recorded in brain slices from control animals before and after treatment with ATPγS (n = 13 endfeet from 8 brain slices, N = 5). Note that events mimicking SAH-induced eHACSs (black dots, peak Ca2+ ≥ 500 nM) emerged following treatment with ATPγS. Horizontal black lines indicate the mean amplitudes of all events. Two-tailed paired t test, ns: not significant (p = 0.05). (c) Summary data showing the frequency of endfoot Ca2+ events in the presence and absence of ATPγS (n = 13 endfeet from 8 brain slices, N = 5). Two-tailed paired t test, **p < 0.01. (d and e) Effect of P2Y receptor activation on NVC. Summary data of EFS-evoked changes in arteriolar diameter (d) and endfoot Ca2+ (e) in brain slices from healthy control animals before and after treatment with ATPγS (n = 5 brain slices, N = 4). α, β-meATP was included in the superfusate for 25 min prior to the application of ATPγS and maintained throughout the experiment. Two-tailed paired t test, *p < 0.05.

SAH-induced eHACSs occur independent of neurotransmitter release

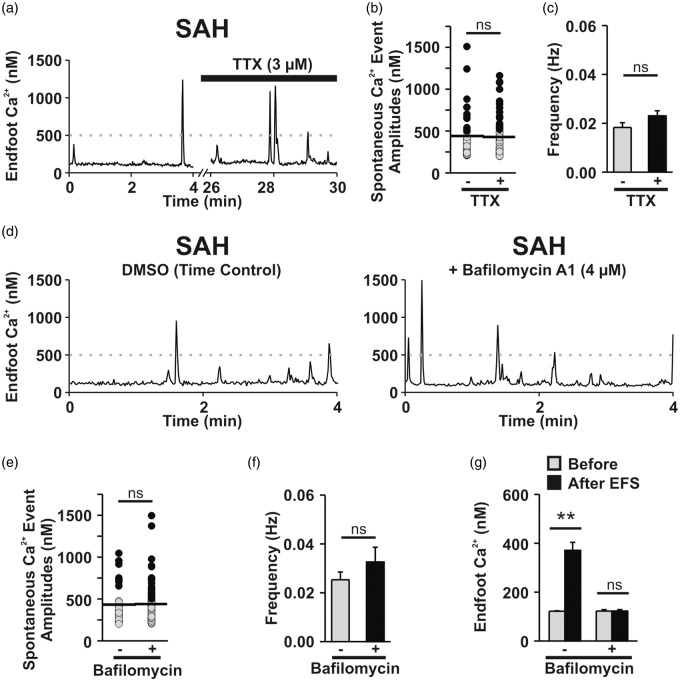

Neuronal release is one potential source of extracellular purine nucleotides (e.g., ATP) that could impact endfoot Ca2+ signaling after SAH.18 To assess the contribution of neurotransmitter release on eHACSs, tetrodotoxin (TTX, 3 μM, 20 min), an inhibitor of voltage-dependent Na+ channels, was used to block neuronal action potentials in brain slices from SAH animals.15 Tetrodotoxin had no effect on the occurrence of eHACSs, the mean amplitude of Ca2+ events, or the frequency of Ca2+ events (Figure 5(a) to (c)), suggesting that neuronal action potentials are not required for the generation of the P2Y receptor-mediated eHACSs (n = 12 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5). These results, however, do not rule out the possibility that quantal (i.e., action potential-independent) neurotransmitter release or vesicular-mediated gliotransmitter release underlies the emergence of eHACSs after SAH.

Figure 5.

Vesicular purine/pyrimidine release is not involved in the generation of eHACSs after SAH. (a) Representative trace of spontaneous Ca2+ activity recorded from a SAH brain slice before and after treatment with tetrodotoxin (TTX), a fast Na+ channel inhibitor that blocks neuronal action potentials. Spontaneous Ca2+ event amplitudes (b) and frequency (c) recorded in brain slices from SAH animals before and after treatment with TTX (n = 12 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5). Note that eHACSs (black dots, peak Ca2+ ≥ 500 nM) are present following treatment with TTX. Horizontal black lines indicate the mean amplitudes of all events. (d) Representative traces of spontaneous Ca2+ activity recorded from SAH brain slices from either the vehicle (DMSO)-treated time control (left) or bafilomycin A1-treated (right) groups. Bafilomycin A1 depletes vesicular contents by inhibiting the vacuolar H+-ATPase. (e) Distribution of all spontaneous Ca2+ event amplitudes recorded in SAH brain slices from the vehicle-treated time control (-bafilomycin, n = 9 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 4) or bafilomycin A1-treated groups (n = 10 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5). Spontaneous Ca2+ events, including eHACSs, were not altered by bafilomycin A1 treatment. (f) Summary data showing the frequency of endfoot Ca2+ events in vehicle-treated time control (n = 9 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 4) or bafilomycin A1-treated brain slices from SAH animals (n = 10 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5). (g) EFS-evoked changes in endfoot Ca2+recorded from vehicle-treated time control (n = 5 brain slices, N = 3) or bafilomycin A1-treated brain slices from SAH animals (n = 5 brain slices, N = 4). EFS failed to elevate endfoot Ca2+ in bafilomycin A1-treated brain slices from SAH animals, confirming vesicle depletion. Two-tailed paired t test, **p < 0.01, ns: not significant.

To determine whether vesicular release of purine nucleotides mediates SAH-induced eHACSs, brain slices from SAH animals were treated with bafilomycin A1 (4 μM), a vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitor (Figure 5(d) to (g)). Bafilomycin depletes both neuronal and astroglial vesicles of transmitter and has been shown to inhibit Ca2+ signals in the fine processes of hippocampal astrocytes.33–35 Brain slices were exposed to bafilomycin for 4 h at room temperature prior to imaging. Vehicle-treated (DMSO: 1:1000 dilution in aCSF) brain slices served as time controls for these experiments. Bafilomycin had no effect on eHACSs, the mean amplitude of events, or frequency of events compared to time controls (Figure 5(d) to (f), Bafilomycin-treated: n = 10 endfeet from 6 brain slices, N = 5 vs. Time control: n = 9 endfeet from 4 brain slices, N = 4). However, bafilomycin-treated slices failed to respond to EFS with a rise in endfoot Ca2+ (Figure 5(g)) or a significant change in arteriolar diameter (6.0 ± 0.3 µm before EFS vs. 6.1 ± 0.3 µm after EFS, two-tailed paired t test, p = 0.77, n = 5 brain slices, N = 4) indicating vesicle depletion of neurotransmitter. Together, these results suggest that neither local neurotransmission nor astroglial vesicular release underlie purinergic receptor activation leading to SAH-induced eHACSs.

Discussion

This study provides evidence that Gq-coupled P2Y receptor signaling underlies the emergence of eHACSs and the inversion of NVC in brain slices from SAH animals. The following observations are consistent with this novel finding: (1) broad-spectrum inhibition of purinergic P2 receptors with suramin blocked eHACSs and restored vasodilatory NVC after SAH; (2) desensitization of Ca2+-permeable P2X receptors had no effect on the incidence of eHACSs; (3) SAH-induced eHACSs were abolished using a combination of inhibitors targeting Gq-coupled P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y6, and P2Y11 receptors; (4) activation of P2Y receptors in brain slices from un-operated control animals mimicked SAH by triggering high-amplitude endfoot Ca2+ events and disrupting NVC. These data identify astrocyte purinergic receptor signaling as an important contributor to SAH-induced micro-vascular dysfunction and impaired NVC.

In brain slices from SAH animals, the emergence of eHACSs has been linked to increased activity of endfoot large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels, increased perivascular K+, and inversion of NVC.15,17 Astrocytes express a variety of P2Y receptor subtypes that can be activated by multiple ligands found in purine/pyrimidine catabolic pathways (e.g., ATP, ADP, UTP, UDP).18,19 As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the broad-spectrum P2 receptor antagonist, suramin28, blocked eHACSs and restored NVC after SAH without affecting normal astrocyte Ca2+ signaling. Aside from its role as a purinergic antagonist, suramin has been shown to have a number of additional effects, including interference with receptor/G-protein coupling, inhibition of DNA and RNA polymerases, and inhibition of growth factor binding.28,36 Suramin has been used for nearly a century as a treatment for the initial phase of African trypanosomisis, commonly referred to as sleeping sickness37 and has been studied as a treatment of high-grade glioma38 and prostate cancer.39 Our data using a combination of reagents targeting P2Y1, P2Y2, P2Y6, and P2Y11 receptors (Figure 3) indicate that the beneficial effects of suramin after SAH (i.e., block of eHACSs and rescue of vasodilatory NVC) are due to inhibition of P2Y receptors, rather than off-target effects. Interestingly, Naviaux et al.40 have recently reported that suramin, through actions on purinergic signaling, can alleviate autism-like behaviors in a mouse model of autism spectrum disorder, and a clinical trial is currently testing the safety and efficacy of single dose i.v. suramin in autism spectrum disorder (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02508259). Further, P2Y receptor-mediated disruption of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and impaired NVC have been observed in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease.22,23 Considering the dire need for better therapeutic options for patients following aneurysmal SAH,1,41 future in vivo studies targeting P2Y receptors using SAH models are warranted.

P2Y receptors are activated by a number of endogenous ligands, including ATP. Consistent with a possible role of extracellular ATP in the generation of SAH-induced eHACSs, elevated levels of ATP have been reported in CSF after SAH,20,21 and we have found that the non-hydrolyzable ATP analog, ATPγS, mimicked SAH by triggering high-amplitude endfoot Ca2+ events and causing inversion of NVC in a portion of brain slices from control animals (Figure 4). A number of sources could potentially contribute to elevated levels of extracellular ATP in brain parenchyma after SAH. For example, both neurons and astrocytes are capable of releasing ATP through vesicular-mediated exocytosis.33,42 However, it is unlikely that vesicular-mediated ATP release is involved in the generation of SAH-induced eHACSs, as neither tetrodotoxin nor bafilomycin impacted these events (Figure 5). Astrocytes, considered to be a main source of extracellular ATP in the brain,18 can also release ATP through connexin-based hemi-channels that are enriched in perivascular astrocyte endfeet.43,44 ATP can also be released from astrocytes via lysosomal-mediated exocytosis.45 Interestingly, our previous work demonstrated the presence of lysosomes within hypertrophic endfeet after SAH that could represent a supply of ATP.17

Extravascular red blood cells (RBCs) represent another potential source of elevated purine nucleotides in brain parenchyma after SAH.46 Autopsy studies of SAH patients and work using experimental SAH models have both demonstrated RBCs deposited along the wall of brain parenchymal arterioles following SAH.15,47 Further, we have found that saline-injected (sham-operated) animals failed to develop eHACSs (Figure 1) or inversion of NVC,15 suggesting the presence of subarachnoid blood is required to bring about these pathological events. It is conceivable that the gradual lysis of RBCs could impact local levels of ATP in the restricted perivascular space between astrocyte endfeet and parenchymal arteriolar myocytes. However, the appearance of eHACSs within 24 h of SAH17 does not readily fit with the reported time course (3–7 days) for the lysis of RBCs in CSF.48,49 Thus, further study will be required to determine the identity and source of P2Y receptor ligands involved in the generation of SAH-induced eHACSs.

Our data show that spontaneous endfoot Ca2+ events depend on phospholipase C activation and, presumably, the production of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). Although the majority of endfeet at two days post-SAH exhibited eHACSs (Figure 1(d)), the overall frequency of endfoot Ca2+ events was unchanged.15,17 Further, blocking SAH-induced eHACSs with either suramin or a cocktail of P2Y inhibitors did not lower the incidence of spontaneous Ca2+ events in subsequent recordings (Figures 1 and 3). These observations suggest that P2Y receptor signaling does not directly trigger eHACSs. Rather, P2Y receptor activity seems to amplify ongoing Ca2+ signals, converting some “control-like” events into eHACSs. It is possible that the aberrant activity of endfoot P2Y receptors after SAH transiently and modestly elevates local IP3 levels. This surplus of IP3 may combine with naturally fluctuating IP3 levels (i.e., the stimulus driving “control-like” events) leading to enhanced release of Ca2+ and the generation of an endfoot high-amplitude Ca2+ signal “eHACS”. Future work will be necessary to elucidate the mechanistic link between P2Y receptor activation and the emergence of eHACSs.

Aberrant purinergic signaling may also have direct implications for arteriolar dysfunction after SAH. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that purinergic signaling regulates basal arteriolar tone in the CNS.50–52 For example, Brayden et al. (2013) report that the Gq-coupled receptors, P2Y4 and P2Y6, contribute to the development of pressure-dependent myogenic tone in cortical arterioles isolated from the rat brain. In the present study, we found that targeting P2 receptors with either the broad-spectrum P2 receptor antagonist, suramin, or the broad-spectrum P2 receptor agonist, ATPγS had clear effects on astrocyte Ca2+ signaling (Figures 1 and 4), but did not impact parenchymal arteriolar diameter in the absence of EFS. It is possible that smooth muscle of the cortical arterioles in our brain slice preparation, which are an order of magnitude smaller than those examined in the report by Brayden et al. do not functionally express P2Y receptors. However, future in vivo studies should include consideration of the potential impact of targeting purinergic receptors throughout the cerebral vasculature.

In summary, a growing body of evidence indicates that pathological changes in astrocyte Ca2+ signaling occur during disease states such as Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy, and SAH.15,17,22,23,53 Further, astrocyte Ca2+ signaling profoundly impacts CBF regulation, including NVC.54–56 Here, we expand upon this knowledge by identifying a causal link between the activity of Gq-coupled P2Y receptors and the emergence of SAH-induced eHACSs and the inversion of NVC. Our observations are consistent with previous reports of P2Y receptor-mediated disruption of astrocyte Ca2+ signaling and impaired NVC in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease.22,23 Moving forward, targeting purinergic signaling in astrocytes may improve cortical blood flow in patients after SAH and provide additional benefits to individuals with other brain pathologies.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms S.R. Russell and Drs M.T. Nelson and A.D. Bonev for their assistance with this study. We acknowledge the University of Vermont Neuroscience Center for Biomedical Research Excellence imaging core facility.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health P01 HL095488, P01 HL095488 03S1, P30 RR032135, P30 GM103498, and S10 OD 010583; the American Heart Association 14SDG20150027; the Totman Medical Research Trust; and the Peter Martin Brain Aneurysm Endowment.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author contributions

GCW contributed to the conception and design of this research, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. ACP and MK contributed to the conception and design of this research, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this paper can be found at http://jcbfm.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data

References

- 1.Dabus G, Nogueira RG. Current options for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced cerebral vasospasm: a comprehensive review of the literature. Interv Neurol 2013; 2: 30–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostergaard L, Aamand R, Karabegovic S, et al. The role of the microcirculation in delayed cerebral ischemia and chronic degenerative changes after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 1825–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terpolilli NA, Brem C, Buhler D, et al. Are we barking up the wrong vessels? Cerebral microcirculation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2015; 46: 3014–3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Khindi T, Macdonald RL, Schweizer TA. Cognitive and functional outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2010; 41: e519–e536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rabinstein AA, Weigand S, Atkinson JL, et al. Patterns of cerebral infarction in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2005; 36: 992–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vergouwen MD, Ilodigwe D, Macdonald RL. Cerebral infarction after subarachnoid hemorrhage contributes to poor outcome by vasospasm-dependent and -independent effects. Stroke 2011; 42: 924–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathiisen TM, Lehre KP, Danbolt NC, et al. The perivascular astroglial sheath provides a complete covering of the brain microvessels: an electron microscopic 3D reconstruction. Glia 2010; 58: 1094–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCaslin AF, Chen BR, Radosevich AJ, et al. In vivo 3D morphology of astrocyte-vasculature interactions in the somatosensory cortex: implications for neurovascular coupling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 795–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Friedman B, et al. Penetrating arterioles are a bottleneck in the perfusion of neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iadecola C, Nedergaard M. Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat Neurosci 2007; 10: 1369–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filosa JA, Bonev AD, Straub SV, et al. Local potassium signaling couples neuronal activity to vasodilation in the brain. Nat Neurosci 2006; 9: 1397–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girouard H, Bonev AD, Hannah RM, et al. Astrocytic endfoot Ca2+ and BK channels determine both arteriolar dilation and constriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 3811–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institoris A, Rosenegger DG, Gordon GR. Arteriole dilation to synaptic activation that is sub-threshold to astrocyte endfoot Ca2+ transients. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 1411–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lecrux C, Kocharyan A, Sandoe CH, et al. Pyramidal cells and cytochrome P450 epoxygenase products in the neurovascular coupling response to basal forebrain cholinergic input. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 896–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koide M, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, et al. Inversion of neurovascular coupling by subarachnoid blood depends on large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: E1387–E1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koide M, Sukhotinsky I, Ayata C, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage, spreading depolarizations and impaired neurovascular coupling. Stroke Res Treat 2013; 2013: 819340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pappas AC, Koide M, Wellman GC. Astrocyte Ca2+ Signaling drives inversion of neurovascular coupling after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosci 2015; 35: 13375–13384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franke H, Verkhratsky A, Burnstock G, et al. Pathophysiology of astroglial purinergic signalling. Purinergic Signal 2012; 8: 629–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James G, Butt AM. P2Y and P2X purinoceptor mediated Ca2+ signalling in glial cell pathology in the central nervous system. Eur J Pharmacol 2002; 447: 247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasseckert SA, Shahzad T, Miqdad M, et al. The mechanisms of energy crisis in human astrocytes after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 2013; 72: 468–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macdonald RL, Weir BK, Marton LS, et al. Role of adenosine 5'-triphosphate in vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: human investigations. Neurosurgery 2001; 48: 854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delekate A, Fuchtemeier M, Schumacher T, et al. Metabotropic P2Y1 receptor signalling mediates astrocytic hyperactivity in vivo in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 5422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takano T, Han X, Deane R, et al. Two-photon imaging of astrocytic Ca2+ signaling and the microvasculature in experimental mice models of Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007; 1097: 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nystoriak MA, O'Connor KP, Sonkusare SK, et al. Fundamental increase in pressure-dependent constriction of brain parenchymal arterioles from subarachnoid hemorrhage model rats due to membrane depolarization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011; 300: H803–H812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parri HR, Gould TM, Crunelli V. Spontaneous astrocytic Ca2+ oscillations in situ drive NMDAR-mediated neuronal excitation. Nat Neurosci 2001; 4: 803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn KM, Hill-Eubanks DC, Liedtke WB, et al. TRPV4 channels stimulate Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in astrocytic endfeet and amplify neurovascular coupling responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 6157–6162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maravall M, Mainen ZF, Sabatini BL, et al. Estimating intracellular calcium concentrations and buffering without wavelength ratioing. Biophys J 2000; 78: 2655–2667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ralevic V, Burnstock G. Receptors for purines and pyrimidines. Pharmacol Rev 1998; 50: 413–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Elementary purinergic Ca2+ transients evoked by nerve stimulation in rat urinary bladder smooth muscle. J Physiol 2005; 564: 201–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barragan-Iglesias P, Pineda-Farias JB, Cervantes-Duran C, et al. Role of spinal P2Y6 and P2Y11 receptors in neuropathic pain in rats: possible involvement of glial cells. Mol Pain 2014; 10: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawamura M, Gachet C, Inoue K, et al. Direct excitation of inhibitory interneurons by extracellular ATP mediated by P2Y1 receptors in the hippocampal slice. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 10835–10845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim B, Jeong HK, Kim JH, et al. Uridine 5'-diphosphate induces chemokine expression in microglia and astrocytes through activation of the P2Y6 receptor. J Immunol 2011; 186: 3701–3709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowser DN, Khakh BS. Vesicular ATP is the predominant cause of intercellular calcium waves in astrocytes. J Gen Physiol 2007; 129: 485–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun MY, Devaraju P, Xie AX, et al. Astrocyte calcium microdomains are inhibited by bafilomycin A1 and cannot be replicated by low-level Schaffer collateral stimulation in situ. Cell Calcium 2014; 55: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Q, Petersen CC, Nicoll RA. Effects of reduced vesicular filling on synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal neurones. J Physiol 2000; 525: 195–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michel MC, Seifert R. Selectivity of pharmacological tools: implications for use in cell physiology. A review in the theme: cell signaling: proteins, pathways and mechanisms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2015; 308: C505–C520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neuberger A, Meltzer E, Leshem E, et al. The changing epidemiology of human African trypanosomiasis among patients from nonendemic countries – 1902–2012. PLoS One 2014; 19: e88647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grossman SA, Phuphanich S, Lesser G, et al. Toxicity, efficacy, and pharmacology of suramin in adults with recurrent high-grade gliomas. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3260–3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahles TA, Herndon JE, Small EJ, et al. Quality of life impact of three different doses of suramin in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate carcinoma: results of Intergroup O159/Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9480. Cancer 2004; 101: 2202–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naviaux JC, Schuchbauer MA, Li K, et al. Reversal of autism-like behaviors and metabolism in adult mice with single-dose antipurinergic therapy. Transl Psychiatry 2014; 4: e400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pluta RM, Hansen-Schwartz J, Dreier J, et al. Cerebral vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage: time for a new world of thought. Neurol Res 2009; 31: 151–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unsworth CD, Johnson RG. Acetylcholine and ATP are coreleased from the electromotor nerve terminals of Narcine brasiliensis by an exocytotic mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990; 87: 553–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cotrina ML, Lin JH, Alves-Rodrigues A, et al. Connexins regulate calcium signaling by controlling ATP release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 15735–15740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simard M, Arcuino G, Takano T, et al. Signaling at the gliovascular interface. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 9254–9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z, Chen G, Zhou W, et al. Regulated ATP release from astrocytes through lysosome exocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 2007; 9: 945–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miseta A, Bogner P, Berenyi E, et al. Relationship between cellular ATP, potassium, sodium and magnesium concentrations in mammalian and avian erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1993; 1175: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crompton MR. The Pathogenesis of cerebral infarction following the rupture of berry aneurysms. Brain 1964; 87: 491–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konno Y, Sato T, Suzuki K, et al. Sequential changes of oxyhemoglobin in drained fluid of cisternal irrigation therapy – reference to the effect of ascorbic acid. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2001; 77: 167–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pluta RM, Afshar JK, Boock RJ, et al. Temporal changes in perivascular concentrations of oxyhemoglobin, deoxyhemoglobin, and methemoglobin after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 1998; 88: 557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brayden JE, Li Y, Tavares MJ. Purinergic receptors regulate myogenic tone in cerebral parenchymal arterioles. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kur J, Newman EA. Purinergic control of vascular tone in the retina. J Physiol 2014; 592: 491–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y, Baylie RL, Tavares MJ, et al. TRPM4 channels couple purinergic receptor mechanoactivation and myogenic tone development in cerebral parenchymal arterioles. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 1706–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tian GF, Azmi H, Takano T, et al. An astrocytic basis of epilepsy. Nat Med 2005; 11: 973–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Anderson CM, Nedergaard M. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral microcirculation. Trends Neurosci 2003; 26: 340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Attwell D, Buchan AM, Charpak S, et al. Glial and neuronal control of brain blood flow. Nature 2010; 468: 232–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Straub SV, Nelson MT. Astrocytic calcium signaling: the information currency coupling neuronal activity to the cerebral microcirculation. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2007; 17: 183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.