Abstract

Viral vaccines have had remarkable positive impacts on human health as well as the health of domestic animal populations. Despite impressive vaccine successes, however, many infectious diseases cannot yet be efficiently controlled or eradicated through vaccination, often because it is impossible to vaccinate a sufficient proportion of the population. Recent advances in molecular biology suggest that the centuries-old method of individual-based vaccine delivery may be on the cusp of a major revolution. Specifically, genetic engineering brings to life the possibility of a live, transmissible vaccine. Unfortunately, releasing a highly transmissible vaccine poses substantial evolutionary risks, including reversion to high virulence as has been documented for the oral polio vaccine. An alternative, and far safer approach, is to rely on genetically engineered and weakly transmissible vaccines that have reduced scope for evolutionary reversion. Here, we use mathematical models to evaluate the potential efficacy of such weakly transmissible vaccines. Our results demonstrate that vaccines with even a modest ability to transmit can significantly lower the incidence of infectious disease and facilitate eradication efforts. Consequently, weakly transmissible vaccines could provide an important tool for controlling infectious disease in wild and domestic animal populations and for reducing the risks of emerging infectious disease in humans.

Keywords: disease, vaccine, herd immunity, genetic engineering, transmissible vaccine, self-disseminating vaccine

1. Introduction

The development of viral vaccines has had remarkable and long-lasting impacts on human health and on the health of domestic and wild animal populations. For instance, viral vaccines have been instrumental in the worldwide eradication of smallpox and rinderpest, the elimination of polio within much of the developed world, and the effective control of many other diseases [1–4]. Despite these impressive successes, many infectious diseases cannot yet be efficiently controlled or eradicated through vaccination programmes, either because an effective vaccine has not yet been developed (as with HIV) or because it is impossible to vaccinate a sufficient proportion of the population to guarantee herd immunity [5]. This problem is particularly acute for diseases of wildlife, including emerging infectious diseases such as Ebola, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and rabies where direct vaccination is impractical, cost-prohibitive or even impossible [6].

Recent advances in molecular biology suggest that the centuries-old method of individual-based vaccine delivery could be on the cusp of a major revolution. Specifically, genetic engineering brings to life the possibility of a transmissible or ‘self-disseminating’ vaccine [6,7]. Rather than directly vaccinating every individual within a population, a transmissible vaccine would allow large swaths of the population to be vaccinated effortlessly by releasing an infectious agent genetically engineered to be benign yet infectious. This concept may sound like science fiction, but the oral polio vaccine already does this to a limited extent [8], and transmissible vaccines have now been developed and deployed in wild animal populations [6]. For instance, recombinant transmissible vaccines have been developed to protect wild rabbit populations against myxomatosis [9] and to interrupt the transmission of Sin Nombre hantavirus in reservoir populations of deer mice [10,11]. In addition, a transmissible vaccine is currently being developed to control Ebola within wildlife reservoirs [12]. Given the current pace of technological advance in genetic engineering, it is only a matter of time before transmissible vaccines can be easily developed for a wide range of infectious diseases.

Although promising, transmissible vaccines are not without risks. The most obvious and significant risk posed by a live transmissible vaccine is the potential for increased virulence to evolve. For instance, if a transmissible vaccine is developed through attenuation involving only a few genetic substitutions, reversions to wild-type virulence may evolve rapidly, as has occurred repeatedly with the oral polio vaccine [8,13]. The risk of reversion to high virulence can be minimized by genetically engineering transmissible vaccines using techniques that impede evolution, such as inflicting a large number of mildly deleterious mutations, rearranging the genome or imposing deletions [7]. Still, even the best engineered transmissible vaccine may ultimately evolve elevated virulence if sufficiently long chains of transmission are allowed to occur. Thus, the safest implementation would also engineer the vaccine so that it can transmit only weakly (R0 < 1), such that chains of transmission are short and stutter to extinction without continuous reintroduction. Transmissible vaccines designed in this way would be much less likely to evolve increased virulence or self-sustaining epidemics [14]. What remains unknown, however, is whether these safe but only weakly transmissible vaccines would significantly enhance our ability to control and eradicate infectious disease.

Here, we develop and analyse a mathematical model that allows us to quantify the extent to which a transmissible vaccine could facilitate efforts to eradicate infectious disease. Although our results apply to vaccines with arbitrary transmission rates, we will focus primarily on weakly transmissible vaccines (R0 < 1) because these represent the safest implementation. Our model is a straightforward extension of existing models of direct vaccination, differing only by including the potential for vaccine transmission among hosts. We use our model to answer two specific questions. First, how much does vaccine transmission facilitate disease eradication? Second, when eradication is impossible, how much does vaccine transmission reduce the incidence of infectious disease within the host population? Answering these questions provides an important first step in quantifying the potential gains that could accrue through the use of a transmissible vaccine.

2. The model

Our model assumes populations are large and well mixed, allowing us to capitalize on the well-developed SIR modelling framework [5]. Specifically, we assume hosts are either susceptible to the disease and vaccine (S), infected by the vaccine (V), infected by the disease (W) or immune/resistant to both vaccine and disease (R). Individuals are assumed to be born at a constant rate, b, which is independent of population size. A constant fraction of these newborn individuals, σ, are assumed to be vaccinated directly. Individuals infected with the live vaccine transmit the vaccine to susceptible individuals at rate, βV, and recover and become immune at rate, δV. Individuals infected with the disease transmit the disease to susceptible individuals at rate, βW, recover and become immune at rate, δW, and succumb to the disease at rate, v. Individuals in all classes are assumed to die at a constant background rate, d. Together, these assumptions lead to the following system of differential equations:

| 2.1a |

| 2.1b |

| 2.1c |

| 2.1d |

where all variables and parameters are described in table 1.

Table 1.

Model parameters.

| parameter | description |

|---|---|

| b | birth rate of susceptible individuals |

| σ | proportion of individuals directly vaccinated at birth |

| βV | rate of vaccine transmission |

| βW | rate of disease transmission |

| d | disease independent death rate of hosts |

| δV | recovery rate of vaccine infected individuals |

| δW | recovery rate of disease infected individuals |

| v | increase in death rate of infected hosts caused by disease |

3. Mathematical analyses

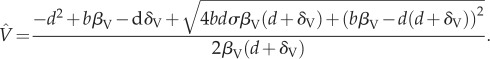

Employing a transmissible vaccine could make it possible to eradicate infectious diseases that have been recalcitrant to direct vaccination alone, and could be particularly useful for eliminating disease in domestic and wild animal populations. We explored this possibility by solving for the conditions under which a transmissible vaccine drives an infectious disease to extinction. Specifically, results derived in appendix A reveal that the fractional reduction in the vaccination threshold arising from use of a transmissible vaccine is given by

| 3.1 |

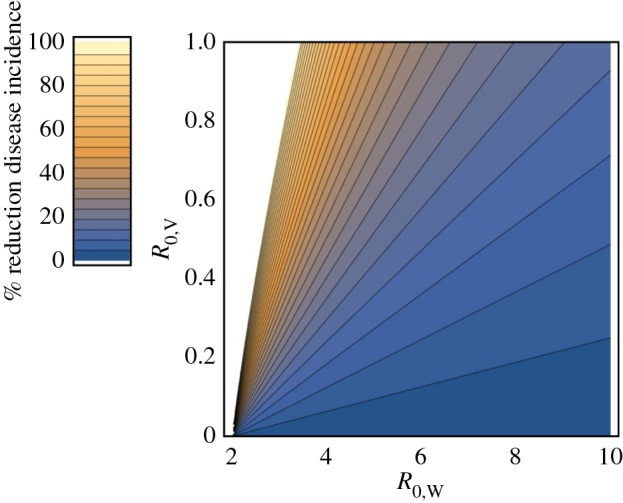

where the quantities R0,W and R0,V are the basic reproductive numbers for the infectious disease and vaccine, respectively. Result (3.1) reveals that the extent to which vaccine transmission facilitates eradication efforts depends on the relative R0 values of vaccine and disease (figure 1). Thus, the closer the R0 of the vaccine to that of the disease, the greater the reduction in direct vaccination effort required for disease eradication. For the particular class of weakly transmissible vaccines we focus on here (i.e. R0,V < 1), this result suggests a transmissible vaccine will have its most appreciable (more than 10%) impacts on the wide range of moderately infectious diseases with R0,W < 10 (e.g. those shown in table 2). Additional analyses performed in the electronic supplementary materials demonstrate that this result remains unchanged even when vaccination is imperfect such that vaccinated individuals return to the susceptible state at some fixed rate.

Figure 1.

The fractional reduction in vaccination effort required to eradicate an infectious disease as a function of vaccine and disease R0. The fractional reduction in vaccination effort increases with the R0 of the vaccine and decreases with the R0 of the disease.

Table 2.

Examples of important diseases with small R0.

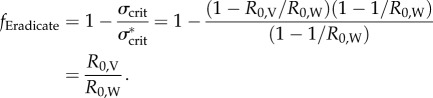

Even in cases where a transmissible vaccine does not allow an infectious disease to be eradicated, it may still reduce disease incidence substantially. We investigated this possibility by solving for the equilibrium incidence of the infectious disease in the absence and presence of vaccine transmission. By comparing these equilibria, we were able to quantify the proportional reduction in disease incidence attributable to vaccine transmission:

| 3.2 |

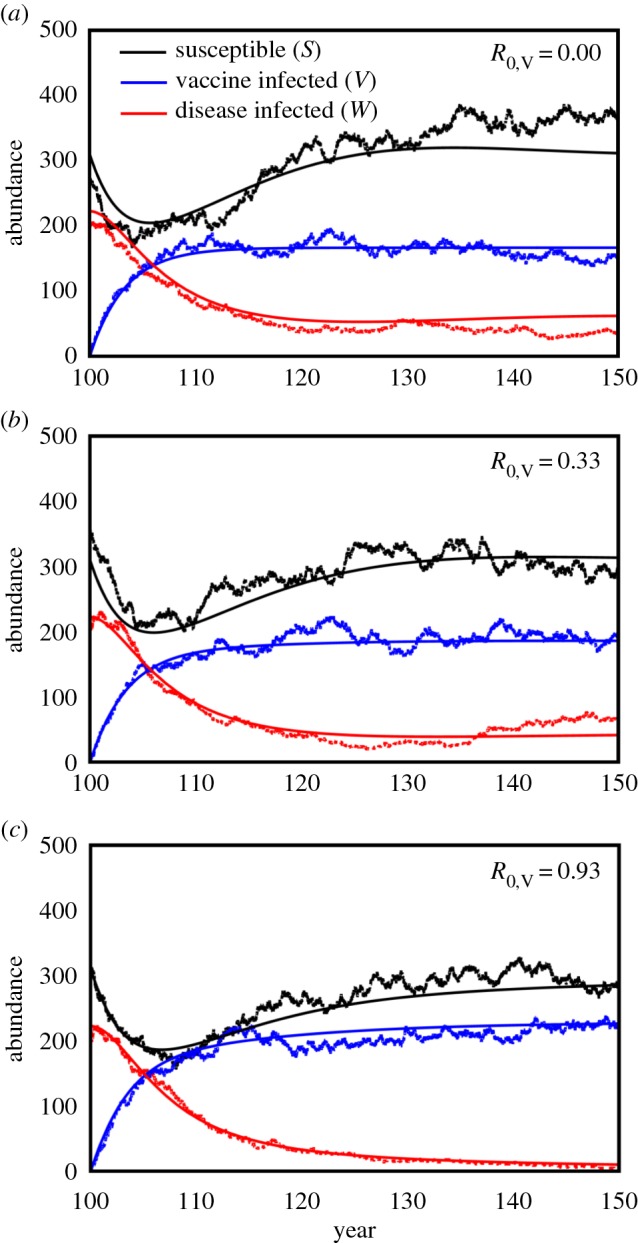

where σ is the fraction of newborns directly vaccinated and is less than the critical value guaranteeing disease eradication given by equation (A 5) (figure 2). The key implication of (3.2) is that even weakly transmissible vaccines can significantly reduce the incidence of an infectious disease, particularly in cases where the infectious disease is not excessively transmissible (e.g. those shown in table 2).

Figure 2.

The fractional reduction in abundance of disease infected hosts (W) as a function of vaccine and disease R0. The direct vaccination rate was set at σ = 0.5 in this figure. Areas shown in white result in disease eradication.

4. Simulations and numerical analyses

To evaluate the robustness of our analytical results to random variation in transmission, vaccination rate and population sizes, we conducted stochastic simulations of our model. Simulations used the Gillespie stochastic simulation algorithm [22] to study the probability of disease elimination with a transmissible vaccine. Simulations were run for three different vaccine transmission rates and initiated with the susceptible population at its disease and vaccine free equilibrium (1000 individuals) and an initial seed of 50 individuals infected with the wild-type disease; resistant hosts and vaccine infected hosts were initially absent. For each transmission rate, 1000 simulations were run for a 100-year burn-in period followed by introduction of a vaccination programme. Simulations were then run for an additional time period and the proportion of simulations in which the disease was eradicated recorded.

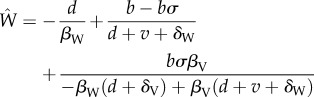

Overall, the results of the simulation runs provided strong support for our analytical solutions. Specifically, under conditions where our analytical results predict a traditional, non-transmissible vaccine would fail to eradicate the disease, eradication occurred in only 2.4% of simulations (24 of 1000 simulations; figure 3a). By contrast, a modestly transmissible vaccine (R0 = 0.93) resulted in the eradication of this disease in 99.9% of simulations (999 of 1000 simulations), in cases where our analytical results predicted eradication (figure 3c). In intermediate scenarios (R0 = 0.33) where our analytical results predicted vaccine transmission would reduce infection rates but fail to completely eradicate the disease, simulations showed vaccine transmission reduced the number of infected individuals by 61.8% relative to a non-transmissible vaccine and resulted in disease eradication in 39.2% of simulations (392 of 1000 simulations; figure 3b).

Figure 3.

The densities of susceptible host individuals (black lines), vaccine infected individuals (blue lines) and disease infected individuals (red lines) predicted by the stochastic simulations (jagged line showing one of the 100 runs) and deterministic model (smooth line) over the 50 years following initiation of the vaccination programme in year 100. Panel (a) shows results for a conventional, non-transmissible vaccine, (b) for a very weakly transmissible vaccine with R0 = 0.33 and (c) for a modestly transmissible vaccine with R0 = 0.93. In all cases, the disease had an R0 = 3.23. Individual parameters were as follows: σ = 0.5, δV = δW = 0.2, b = 100, d = 0.1, v = 0.01 and βW = 0.001 in all panels. The transmission rate of the vaccine was βV = 0 in (a), βV = 0.0001 in (b) and βV = 0.00028 in (c).

Additional simulations evaluated the probability of disease extinction as a function of vaccine R0, by conducting 1000 replicate simulations for values of vaccine R0 ranging from 0 to 1. These values of vaccine R0 bracketed the critical value for disease eradication predicted by equation (A 5), and show that reductions in disease incidence caused by the transmissible vaccine result in a high probability of disease eradication even before the critical threshold of vaccine transmission is reached (figure 4). The reason disease eradication occurs prior to reaching the eradication threshold is that vaccine transmission reduces the number of individuals infected with the disease sufficiently for stochastic extinction to become likely.

Figure 4.

The proportion of stochastic simulations resulting in disease eradication 150 years after vaccine introduction as a function of vaccine R0. In all cases, the disease had an R0 = 3.23. The black vertical line shows the value of vaccine R0 that should result in the deterministic eradication of the infectious disease as predicted by equation (A 5) in appendix A. Parameters are identical to figure 3 in the main text, with the exception of βV which varied from 0 to 0.003 in 0.000015 increments.

Finally, to evaluate the sensitivity of a transmissible vaccine to reversion, we simulated a slightly modified model where individuals infected with the vaccine (V) were converted to individuals infected with wild-type virus (W) at a constant rate r (see the electronic supplementary material for details). Results of these simulations demonstrated that our qualitative result, that vaccine transmission facilitates disease eradication, is robust to reversion. Reversion does, however, reduce the benefits provided by vaccine transmission. Only when reversion becomes very frequent can vaccine transmission actually reduce the likelihood of disease eradication, and even then this only occurs for vaccines that transmit very, very weakly (electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

5. Discussion

Our results show that even a weakly transmissible vaccine can substantially facilitate efforts to control or eradicate infectious disease. There are two important consequences of this result. First, if it is impossible to directly vaccinate a sufficient fraction of a population for disease eradication, whether due to limitations of public health infrastructure or prohibitive cost, vaccine transmission can tip the balance in favour of eradication. Second, even modest amounts of vaccine transmission can substantially reduce the effort and cost required to achieve a target level of vaccination within a population. These results are important because they demonstrate that it may be feasible to engineer transmissible vaccines that are effective while maintaining the greater margin of safety that comes from being only weakly transmissible (R0 < 1).

Unfortunately, even a weakly transmissible vaccine has some potential to revert to wild-type virulence. This is particularly true for live, attenuated vaccines developed using traditional methods that adapted a virus to unnatural conditions in the hope that growth in the focal host would decline and pathogenesis would wane. Because these old methods were haphazard, vaccines developed in this way may require only a few genetic changes to revert to wild-type virulence, as has been observed for the oral polio vaccine [13]. Fortunately, recent developments in genetic engineering provide considerable improvements in attenuation methods and the promise of reduced scope for reversion. One especially promising method is attenuation by introducing many silent codon changes [7,23,24]. For reasons still not fully understood, some types of silent codon changes reduce fitness slightly, and when dozens to hundreds of such changes are combined in the same genome, fitness can be reduced to arbitrary levels. Deletions and genome rearrangements have similar attenuating effects and also appear to be suitable for different degrees of attenuation. When combined with weak transmission, the reduced probability of reversion provided by the new genetic technologies may make development of safe transmissible vaccines feasible.

Even if it becomes possible to genetically engineer transmissible vaccines that have very low probabilities of reversion, ethical and safety concerns will likely preclude using them directly within human populations except under extraordinary circumstances [25,26]. Instead, the real power of transmissible vaccines likely lies in their ability to improve vaccine coverage in populations of livestock and wildlife where direct vaccination of a significant proportion of the population is excessively costly or even impossible in many cases. Although transmissible vaccines have not yet been used in this capacity on a large scale, a recombinant transmissible vaccine has been developed to protect wild rabbit populations against myxomatosis [9] and to interrupt the transmission of Sin Nombre hantavirus in reservoir populations of deer mice [6]. Similar approaches could be used to develop transmissible vaccines against invasive wildlife diseases, such as West Nile virus [27], to protect threatened wildlife populations from infectious disease [28] or to eliminate diseases like rabies from wild reservoir populations.

The models we have studied here are obvious simplifications designed to make a first-pass estimate at the potential benefits that may be realized by using weakly transmissible vaccines. There are, of course, many ways in which our models could be generalized to evaluate the more nuanced biology of real populations, including spatial structure [29–31], heterogeneities in host populations [32–37], imperfect vaccines [38,39] and the potential for vaccine and disease evolution [14,40,41]. Circumscribing the conditions under which transmissible vaccines will provide benefits that exceed their potential risks will ultimately require exploration of these additional complexities.

6. Conclusion

The potential for a transmissible or self-disseminating vaccine to facilitate efforts to control and eradicate infectious disease has long been appreciated [42], but the oral polio vaccine and vaccines designed for wildlife remain the only well-documented examples [1,6,8–12]. Much of the reticence surrounding the development of transmissible vaccines stems from the justifiable concern that the potential for evolutionary reversion to wild-type virulence outweighs their potential benefits. Our results show, however, that even weakly transmissible vaccines can facilitate disease eradication and reduce disease incidence. When combined with new developments in genomic engineering that facilitate the development of transmissible vaccines that cannot easily evolve to be self-sustaining [7], these results suggest weakly transmissible vaccines may provide a safe and effective tool in the battle against infectious disease.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Analyses of equilibria and local stability

Mathematical analyses of equation (2.1a–d) reveals three possible equilibria, only two of which exist. The first equilibrium is given by

| A 1a |

|

A 1b |

| A 1c |

and the second equilibrium is given by

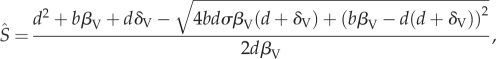

|

A 2a |

| A 2b |

and

|

A 2c |

Local stability analyses of (A 1) and (A 2) reveal that the equilibrium where the infectious disease is extinct (A 2) is stable if:

| A 3 |

When this stability condition holds, the alternative equilibrium where the infectious disease is present (A 1) is locally unstable. If local stability condition (A 3) does not hold, the situation reverses and only the equilibrium with a positive density of individuals infected by the disease is locally stable. Thus, condition (A 3) is sufficient to completely predict the qualitative dynamics of this system.

Defining the basic reproductive numbers of the vaccine and disease in the standard way as

| A 4a |

and

| A 4b |

allows condition (A 3) to be re-written in a more insightful form defining the critical level of direct vaccination required for disease eradication:

| A 5 |

In the absence of vaccine transmission, (A 5) reduces to the classical expression for the critical fraction of a population that must be vaccinated directly for disease eradication to occur

| A 6 |

To make the benefits of vaccine transmission more transparent, we calculate the percentage reduction in vaccination effort provided by a transmissible vaccine relative to a traditional, non-transmissible, vaccine

|

A 7 |

This is equation (3.1) of the text.

To quantify the reduction in disease incidence provided by vaccine transmission, we calculated the following quantity:

| A 8 |

where  is the equilibrium incidence of the infectious disease when confronted with a transmissible vaccine (equation (A 1b) with βV > 0), and

is the equilibrium incidence of the infectious disease when confronted with a transmissible vaccine (equation (A 1b) with βV > 0), and  is the equilibrium incidence of the infectious disease when confronted with a non-transmissible vaccine (equation (A 1b) with βV = 0). Making use of the previous definitions for R0,V and R0,W allows expression (A 8) to be simplified to the more intuitive expression (3.2) in the main text.

is the equilibrium incidence of the infectious disease when confronted with a non-transmissible vaccine (equation (A 1b) with βV = 0). Making use of the previous definitions for R0,V and R0,W allows expression (A 8) to be simplified to the more intuitive expression (3.2) in the main text.

Authors' contributions

J.J.B., R.A., B.M.A. and S.L.N. conceived of the study; R.A., R.M. and S.L.N. developed the model and derived analytical solutions; B.M.A. and S.L.N. performed stochastic simulations; J.J.B., R.A., S.L.N., B.M.A. and R.M. helped draft the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

Funding was provided by NSF grant nos. DEB 1118947 and DEB 1450653 (S.L.N.), NSF Cooperative Agreement No. DBI-0939454 (J.J.B. and S.L.N.), NIH grant GM57756 (J.J.B.), NIH grant nos. U54 GM111274 and U19 AI117891 (R.A.), NIH grant no. GM122079 (S.L.N. and J.J.B.) and from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the Global Good Fund, the Santa Fe Institute and the Omidyar Group (B.A.).

References

- 1.Kew OM. 2012. Reaching the last one per cent: progress and challenges in global polio eradication. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2, 188–198. ( 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauring AS, Jones JO, Andino R. 2010. Rationalizing the development of live attenuated virus vaccines. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 573–579. ( 10.1038/nbt.1635) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathanson N, Kew OM. 2010. From emergence to eradication: the epidemiology of poliomyelitis deconstructed. Am. J. Epidemiol. 172, 1213–1229. ( 10.1093/aje/kwq320) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sánchez-Sampedro L, Perdiguero B, Mejías-Pérez E, García-Arriaza J, Di Pilato M, Esteban M. 2015. The evolution of poxvirus vaccines. Viruses 7, 1726–1803. ( 10.3390/v7041726) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson RM, May RM. 1991. Infectious diseases of humans: dynamics and control, 757 p. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy AA, Redwood AJ, Jarvis MA. 2016. Self-disseminating vaccines for emerging infectious diseases. Expert Rev. Vaccines 15, 31–39. ( 10.1586/14760584.2016.1106942) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bull JJ. 2015. Evolutionary reversion of live viral vaccines: can genetic engineering subdue it? Virus Evol. 1, vev005. ( 10.1093/ve/vev005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns CC, Diop OM, Sutter RW, Kew OM. 2014. Vaccine-derived polioviruses. J. Infect. Dis. 210(Suppl 1), S283–S293. ( 10.1093/infdis/jiu295) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bárcena J, et al. 2000. Horizontal transmissible protection against myxomatosis and rabbit hemorrhagic disease by using a recombinant myxoma virus. J. Virol. 74, 1114–1123. ( 10.1128/JVI.74.3.1114-1123.2000) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizvanov AA, Khaiboullina SF, van Geelen AGM, St Jeor SC. 2006. Replication and immunoactivity of the recombinant Peromyscus maniculatus cytomegalovirus expressing hantavirus G1 glycoprotein in vivo and in vitro. Vaccine 24, 327–334. ( 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.07.070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizvanov AA, van Geelen AGM, Morzunov S, Otteson EW, Bohlman C, Pari GS, St Jeor SC. 2003. Generation of a recombinant cytomegalovirus for expression of a hantavirus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 77, 12 203–12 210. ( 10.1128/jvi.77.22.12203-12210.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuda Y, et al. 2015. A cytomegalovirus-based vaccine provides long-lasting protection against lethal Ebola virus challenge after a single dose. Vaccine 33, 2261–2266. ( 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kew OM, Sutter RW, de Gourville EM, Dowdle WR, Pallansch MA. 2005. Vaccine-derived polioviruses and the endgame strategy for global polio eradication. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59, 587–635. ( 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123625) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antia R, Regoes RR, Koella JC, Bergstrom CT. 2003. The role of evolution in the emergence of infectious diseases. Nature 426, 658–661. ( 10.1038/nature02104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hampson K, Dushoff J, Cleaveland S, Haydon DT, Kaare M, Packer C, Dobson A. 2009. Transmission dynamics and prospects for the elimination of canine rabies. PLoS Biol. 7, 462–471. ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barlow ND. 1991. A spatially aggregated disease host model for bovine TB in New Zealand possum populations. J. Appl. Ecol. 28, 777–793. ( 10.2307/2404207) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Hare A, Orton RJ, Bessell PR, Kao RR. 2014. Estimating epidemiological parameters for bovine tuberculosis in British cattle using a Bayesian partial-likelihood approach. Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 20140248 ( 10.1098/rspb.2014.0248) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandit PS, Bunn DA, Pande SA, Aly SS. 2013. Modeling highly pathogenic avian influenza transmission in wild birds and poultry in West Bengal, India. Sci. Rep. 3, 2175 ( 10.1038/srep02175) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ward MP, Maftei D, Apostu C, Suru A. 2009. Estimation of the basic reproductive number (R-0) for epidemic, highly pathogenic avian influenza subtype H5N1 spread. Epidemiol. Infect. 137, 219–226. ( 10.1017/s0950268808000885) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orsel K, Dekker A, Bouma A, Stegeman JA, de Jong MCM. 2005. Vaccination against foot and mouth disease reduces virus transmission in groups of calves. Vaccine 23, 4887–4894. ( 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.05.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbarossa MV, Denes A, Kiss G, Nakata Y, Rost G, Vizi Z. 2015. Transmission Dynamics and final epidemic size of Ebola virus disease outbreaks with varying interventions. PLoS ONE 10, 21 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0131398) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillespie DT. 1977. Exact stochastic simulation of coupled chemical reactions. J. Phys. Chem. 81, 2340–2361. ( 10.1021/j100540a008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns CC, Shaw J, Campagnoli R, Jorba J, Vincent A, Quay J, Kew O. 2006. Modulation of poliovirus replicative fitness in HeLa cells by deoptimization of synonymous codon usage in the capsid region. J. Virol. 80, 3259–3272. ( 10.1128/jvi.80.7.3259-3272.2006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller S, Papamichail D, Coleman JR, Skiena S, Wimmer E. 2006. Reduction of the rate of poliovirus protein synthesis through large-scale codon deoptimization causes attenuation of viral virulence by lowering specific infectivity. J. Virol. 80, 9687–9696. ( 10.1128/jvi.00738-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isaacs D, Kilham H, Leask J, Tobin B. 2009. Ethical issues in immunisation. Vaccine 27, 615–618. ( 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luyten J, Vandevelde A, Van Damme P, Beutels P. 2011. Vaccination policy and ethical challenges posed by herd immunity, suboptimal uptake and subgroup targeting. Public Health Ethics 4, 280–291. ( 10.1093/phe/phr032) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kilpatrick AM. 2011. Globalization, land use, and the invasion of West Nile virus. Science 334, 323–327. ( 10.1126/science.1201010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan SJ, Walsh PD. 2011. Consequences of non-intervention for infectious disease in African Great Apes. PLoS ONE 6, e29030 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0029030) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keeling MJ. 1999. The effects of local spatial structure on epidemiological invasions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 266, 859–867. ( 10.1098/rspb.1999.0716) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.May RM, Anderson RM. 1984. Spatial heterogeneity and the design of immunization programs. Math. Biosci. 72, 83–111. ( 10.1016/0025-5564(84)90063-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostfeld RS, Glass GE, Keesing F. 2005. Spatial epidemiology: an emerging (or re-emerging) discipline. Trends Ecol. Evol. 20, 328–336. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2005.03.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bansal S, Grenfell BT, Meyers LA. 2007. When individual behaviour matters: homogeneous and network models in epidemiology. J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 879–891. ( 10.1098/rsif.2007.1100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dwyer G, Elkinton JS, Buonaccorsi JP. 1997. Host heterogeneity in susceptibility and disease dynamics: tests of a mathematical model. Am. Nat. 150, 685–707. ( 10.1086/286089) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Regoes RR, Nowak MA, Bonhoeffer S. 2000. Evolution of virulence in a heterogeneous host population. Evolution 54, 64–71. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00008.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp PE, Getz WM. 2005. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 438, 355–359. ( 10.1038/nature04153) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Althouse BM, Hebert-Dufresne L. 2014. Epidemic cycles driven by host behaviour. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140575 ( 10.1098/rsif.2014.0575) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Althouse BM, Patterson-Lomba O, Goerg GM, Hebert-Dufresne L. 2013. The timing and targeting of treatment in influenza pandemics influences the emergence of resistance in structured populations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1002912 ( 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002912) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gandon S, Mackinnon M, Nee S, Read A. 2003. Imperfect vaccination: some epidemiological and evolutionary consequences. Proc. R. Soc. B 270, 1129–1136. ( 10.1098/rspb.2003.2370) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gandon S, Mackinnon MJ, Nee S, Read AF. 2001. Imperfect vaccines and the evolution of pathogen virulence. Nature 414, 751–756. ( 10.1038/414751a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grenfell BT, Pybus OG, Gog JR, Wood JLN, Daly JM, Mumford JA, Holmes EC. 2004. Unifying the epidemiological and evolutionary dynamics of pathogens. Science 303, 327–332. ( 10.1126/science.1090727) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levin BR, Lipsitch M, Bonhoeffer S. 1999. Evolution and disease—population biology, evolution, and infectious disease: convergence and synthesis. Science 283, 806–809. ( 10.1126/science.283.5403.806) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabin AB. 1985. Oral poliovirus vaccine: history of its development and use and current challenge to eliminate poliomyelitis from the world. J. Infect. Dis. 151, 420–436. ( 10.1093/infdis/151.3.420) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.