Abstract

Identification, protection, and management of patellofemoral articular cartilage lesions continue to remain on the forefront of sports medicine rehabilitation. Due to high-level compression forces that are applied through the patellofemoral (PF) joint, managing articular cartilage lesions is challenging for sports medicine specialists. Articular cartilage damage may exist in a wide spectrum of injuries ranging from small, single areas of focal damage to wide spread osteoarthritis involving large chondral regions. Management of these conditions has evolved over the last two centuries, most recently using biogenetic materials and cartilage replacement modalities. The purpose of this clinical commentary is to discuss PF articular cartilage injuries, etiological variables, and investigate the evolution in management of articular cartilage lesions. Rehabilitation of these lesions will also be discussed with a focus on current trends and return to function criteria.

Level of Evidence

5

Keywords: Articular cartilage, anterior knee pain, osteochondral defect, osteochondritis dissecans, patellofemoral pain

INTRODUCTION

Although the patellofemoral (PF) articular cartilage is the thickest in the human body, it is not immune to breakdown and injury. When in healthy condition, this amazing anatomical structure is able to resist and disperse tremendous loads as well or better than any man-made material. The co-efficient of friction is almost zero, which allows articular cartilage to transmit forces with relative ease. Unfortunately, when breakdown occurs, there is little or no healing capacity of articular cartilage. Articular cartilage injuries may limit sporting activities as symptoms develop that limit peak performance and/or create the inability to maintain a healthy lifestyle of exercise. Factors that influence this breakdown may include: 1) articular cartilage injury during knee ligament disruption, 2) excessive body weight with sporting activity or exercise, 3) PF dislocation 4) knee arthrofibrosis 5) and joint geometry/ limb alignment.

Although exciting surgical techniques and rehabilitation advances have been developed, often simply gaining normal strength, flexibility, and modifying sporting activities may yield good results with this difficult to treat problem. When those efforts fail, thankfully surgical intervention techniques exist that have been developed to assist articular cartilage injury recovery. These procedures often require a prolonged rehabilitation process that commonly includes a period of non-weight bearing and gradual return to activity. Having expert knowledge of the biomechanics of the PF joint, articular cartilage, and muscle forces about this joint allows the sports medicine clinician to help patients focus their energy and efforts towards the most efficient pathway towards recovery. Far too often, patients waste time performing inappropriate and sometimes-harmful exercises and techniques that only retard their progress.

The purpose of this clinical commentary is to discuss PF articular cartilage injuries, etiological variables, and investigate the evolution in management of articular cartilage lesions. Rehabilitation of these lesions will also be discussed with a focus on current trends and return to function criteria. There are two main sub-focal points of this commentary, osteochodritis dessicans (Odessicans), and osteochondral defects (Odefect) of the PF joint. A general overview will be presented that will cover both maladies then specific information for each diagnosis.

HISTORICAL EVOLUTION OF THE TREATMENT APPROACHES FOR ARTICULAR CARTILAGE LESIONS

Articular cartilage lesions have been a dilemma for treating physicians dating back to the initial medical reports, in 1743, by Dr. William Hunter. Hunter described the appearance of an “ulcerated cartilage” in the knee. Of particular concern, Hunter described the lesion as lacking native regenerative potential. Dr. Paget echoed these concerns, reporting that there is no known intervention able to restore or completely repair injured cartilage due to a lack of substantial vascular response and the relative absence of undifferentiated cells available to respond to injury.1 Compounded by the large biomechanical forces seen by the PF joint during normal daily activities, articular cartilage lesions may become a debilitating problem.

Early Cartilage Procedures: Debridement and Reparative Procedures

Sixty years ago, in 1945, Haggart2 and Magnuson3 sought to reduce mechanical symptoms and pain in the knee caused by articular cartilage defects via cleaning the joint and joint surfaces. This open procedure involved joint lavage and simple debridement of the joint surfaces. Reports of short-term pain reduction were overshadowed by failure of the arthritic joint due to disease progression. Development of arthroscopic techniques sought to improve results, however never offering the possibility to actually promote articular cartilage repair. Arthroscopic debridement continues to be utilized today as a technique for diminishing mechanical symptoms and joint irritation, capable of producing success in short term pain management.4

Abrasion Drilling and Early Phase Microfracture

In 1946, Pridie5,6 revolutionized what would eventually become a hallmark of cartilage reparative treatment , ten years after Haggart and Magnusson, Pridie5,6with the assistance of Johnson,7 described the procedure of drilling into the defective cartilaginous area and penetrating the subchondral bone. This was theorized to stimulate mesenchyme bone marrow stem cells that would provide fibrocartilage structure to fill the defective zone. This new technique resulted in the development of three types of marrow-stimulating procedures each aimed to produce native fibrous cartilage in the defect. The three procedures were: 1) abrasion arthroplasty, 2) subchondral drilling, and 3) microfracture.

Modern Microfracture

Nineteen ninety-two marked a pivotal point in arthroscopic surgical techniques that addressed articular cartilage lesions. Steadman8 developed, a widely utilized technique, called the microfracture procedure. This technique utilizes a controlled drilling into, but not through, subchondral bone with careful focus on drilling using precise specifications. A major concern and overwhelming disadvantage with the microfracture procedure is the loss of structural integrity of the cartilage produced by the procedure. Furthermore, unlike hyaline cartilage found in native articular cartilage, microfracture produces fibrocartilage composed of primarily Type I collagen that has significantly different biomechanical properties than hyaline cartilage. This structural difference in tissue is the primary criticism and motivation for continued evolution of restorative and replacement cartilage procedures, throughout the body, most typically in the tibiofemoral and the PF joints. Although more advanced techniques and procedures have been developed, microfracture continues to be a popular technique due used to treat both retro-patellar and trochlear cartilage lesions.

Tibial Tubercle Osteotomy (Fulkerson) or AMZ: Realignment Techniques

Initially described by Fulkerson et al9,10 in 1983, antero-medialization (AMZ) of the tibial tubercle was designed to improve the biomechanical pathology related to abnormal wear patterns in the PF joint. The goal of this procedure is to decrease the Q-angle to a more normal central position via anteriorization of the tibial tubercle up to 15 mm, thereby decreasing the lateral facet contact pressure. Tibial tubercle osteotomies, and advancement or antero-medialization (AMZ) procedures, are often combined with cartilage restoration procedures in order to unload the treated lesion site in the PF region.9,10

Lateral Retinacular Release: Realignment Techniques

Isolated lateral retinacular release procedures are a controversial surgical option. This procedure involves incising and thus releasing part of the lateral retinaculum in an attempt to centralize the patella in the trochlea to decrease the lateral tilt of the patella, and enhance patellar tracking. Researchers have debated whether releasing the lateral patellar restraint actually leads to altered patellar contact pressures or aids in patellar stability.9-11 Short term data was encouraging initially, although research is sparse and inconsistent with respect to long-term outcomes and function. This procedure is not without complications, one being a too aggressive release creating hypermobility of the PF joint with increased instability, dysfunction, and pain. The only indication for such a procedure is the presence of a tight lateral retinaculum.9-11

Autologous Matrix Induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC)

The final phase of marrow stimulation, AMIC, was introduced in 2005, and was the next technological advancement following the microfracture procedure. AMIC utilized a collagen scaffold that was placed over the defect, which serves to hold the blood clot and mesenchymal stem cells in place following microfracture drilling.12 Current research seems to support the value of the AMIC procedure in retropatellar defects, when unresponsive to microfracture alone.13 Described below, various chondrocyte implantation procedures have evolved from this procedure.

Restorative and Reconstructive Procedures

With the start of the 21st Century, cartilage restorative, replacement, and stem cell propagation have become increasingly more popular and ultimately the forefront of research and intervention.

Autologous Cartilage Implantation (ACI) & Matrix-Induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI) : Restorative Techniques

A landmark animal study presented by Peterson et al14 in 1984 reported early positive outcomes of bioengineered tissue implantation for chondral defects that did not penetrate the subchondral bone. After a decade of research, the FDA approved the first cell therapy for use in restoring articular cartilage, Carticel, in 1997.

ACI is a staged procedure, which utilizes an arthroscopic biopsy of normal hyaline cartilage or bone marrow to be used to culture chondrocytes, in vitro, for implantation at a second staged surgery. These maturing cells are placed in the cartilage defect beneath an autologous periosteal patch, an evolution of the scaffolding patch described for use in the AMIC component of microfracture. Based on early success, ACI saw an increase in utilization, specifically in treatment for cartilage damage of the femoral condyles, trochlea, and patella. Since Peterson's original description, there have been several modifications of the technique of autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI).15

The 3rd generation in autologous cartilage implantation, matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI), has become more frequently used, especially in European medicine. MACI uses temporary, biodegradable scaffolds to enhance the implanted chondrocytes by reducing graft hypertrophy, lessening chondrocyte leakage, creating a more homogenous chondrocyte matrix, and an overall shorter operative time.

ACI is a common treatment approach for PF lesions considered too large for microfracture, however success in PF lesions remain inferior to those performed elsewhere in the tibiofemoral joint.16 Of note, ACI and MACI procedures combined with an unloading tibial tubercle osteotomy (AMZ) have produced significantly higher improvements in functional outcomes and overall patient satisfaction.16

Osteochondral Plug Autograft Procedures: Osetochondral Autograft Transfer System (OATS) & Mosaicplasty: Restorative Techniques

Osteochondral autograft transplantation (OATS) was initially described by Judet et al16 in 1908. OATS and, mosaicplasty, involve the harvesting of multiple individual osteochondral plugs from the patients' donor site, typically the non-weight-bearing area of the femoral condyle in the knee. The grafts are pressed into the debrided lesion in a “mosaic-like” fashion within the same-size drilled tunnels. The resultant surface consists of transplanted hyaline cartilage. Fibrocartilage arising from abrasion arthroplasty is theorized to act as a “grout” between the individual autografts. Consequently, this procedure is dependent on the availability of quality donor tissue for the transplant. Typically, harvest sites for the PF joint are the medial and lateral margins of the trochlea, the intercondylar notch, and the posterior femoral condyles. Garretson et al reported that the medial trochlea had the lowest contact pressures, followed by the distal lateral trochlea, and that these two areas could provide desirable donor grafts.17 Limited research exists regarding outcomes after OATS procedures for PF joint lesions. The procedure is considerably more challenging and complicated for patellar lesions (as compared to tibiofemoral lesions) in large part due to the difficulty of correctly matching the surface concavity and convexity of the PF articulation.

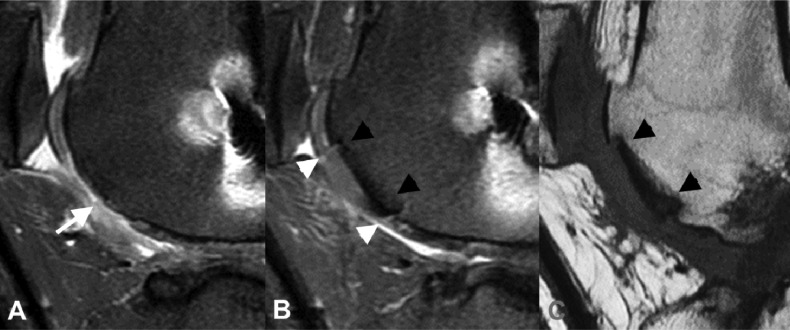

Osteochondral Allograft: Restorative Technique

Initially reported by Lexar18 in 1908, osteochondral allograft transplantation utilizes similar principles as the autograft procedures, OATS and mosaicplasty. Although the initial results seemed promising, the logistical problems of tissue acquisition (fresh, un-irradiated osteochondral grafts) compounded by the high risk of disease transmission, has limited the plausibility of these techniques throughout the century. Cryopreserved grafts allowed for appropriate processing and lowered the risk of disease transmission, however also decreased the viability of the chondrocytes in the transplant.

In the late 1990's, transplants were made commercially available in the United States with a change in the FDA's harvesting procedure techniques substantially increasing the utility of allografts. This innovation involved a type of refrigeration method that led to a significant increase in allograft implementation, more commonly on the femoral condyles. However, small utility does exist for trochlear cartilage lesions but is a more complicated procedure than tibiofemoral implantation.

Patellofemoral Arthroplasty: Replacement Techniques

Patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA) has been available for approximately 30 years, although outcomes and clinical indications are scattered.19 The procedure sought to correct an isolated PF compartment failure by replacing this compartment using low friction components. This was an intervention was ultimately designed for younger patients, with isolated PF lesions, and were too young for a complete total joint replacement. A thin metallic shield covers the trochlear groove and a dome-like plastic implant is placed on the retropatellar surface. Both components are held in place by bone cement. Unfortunately, in many cases, chondral changes eventually progressed to include the medial and lateral compartments. This led to controversy over outcomes, and ultimately PFA has become less popular in recent years.20

Biologic Agents: Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC's)

In 1994, the use of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MCS's), rather than chondrocytes, during the ACI procedure was described with the intention of producing a more homogenous hyaline cartilage state.21 This marked the first autologous implantation of stem cells for treatment of cartilage defects. Initial proposed successes of these procedures suggested the use of biologic agents as a medium to enhance or augment other procedures.

MSC's utility generically revolves around two criteria: the ability to self-replicate in the placed environment (proliferation), and ability to differentiate to suit the necessary tissue (maturation).21 Friedenstein et al22 first demonstrated that bone marrow cells (MSC's) could differentiate into bone and cartilage. Furthered by Johnstone et al23 and Pittenger et al24 respectively, it was determined that MSCs harvested from bone marrow could ultimately differentiate into bone, cartilage, tendon, ligament, fat, and other tissues of mesenchymal origin. MSC's can be harvested from a variety of sources, such as peripheral blood, or bone marrow and adipose (both of which being significantly more successful and higher concentration than blood based harvesting).

First-generation MSC's were used via direct implantation under a periosteal patch, similar to ACI procedures.25 Second-generation techniques removed and differentiated the MSCs in vitro, typically using a biotype matrix and were implanted into the affected lesion once matured.26-28 These procedures failed to succeed with evidence now suggesting that non-expanded MSC therapies are not effective to produce viable articular cartilage. New-generation techniques have begun that include implanting the cells and bio scaffolding in association with platelet rich plasma (PRP) fibrin glue into the lesion. Evidence has shown initial support, but cell differentiation, reproduction, mechanical integrity, and ultimately the longevity of the materials remains unknown. Despite a growing body of evidence, the use of MSC's continues to need further research. Most typically, MSC'S are used in procedures as a supplement to enhance success, such as meniscal repairs, cruciate ligament reconstructions, cartilage transplantation, primary restorative interventions, as well as agents to prevent graft-versus-host failures.21,25,29,30

Biologic Agents: Platelet Rich Plasma (PRP)

Reports of PRP utilization can be found as early as the 1970's, although the concepts of platelet count and volume are more recent evolutions. PRP is simply withdrawing peripheral blood and, by centrifugation, obtaining a highly concentrated sample of platelets to re-introduce as an inflammatory and growth factor supplement. Current research is related to improving platelet count, increasing concentration of growth factors, and examining mechanisms by which sustained activation of the mediating factors can be achieved.31

Current PRP trends have seen an exponential influx in use over the last decade for a variety of musculoskeletal pathologies, although literature is inconclusive at this time related to clinical outcomes and indications. PRP is relatively easy and convenient to extract, as well as relatively inexpensive when compared to other biologic stem cell agents, which makes it a viable option for first line treatment in non-surgically indicated pathologies, such as retro-patellar chondromalacia or small partial thickness defects.31,32

Future Trends

The use of autologous MSCs for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions is currently unproven, and its clinical efficacy and safety are yet to be determined, despite a proliferation of clinics offering and actively marketing MSCs for treatment of several musculoskeletal problems.33-36 Currently, evidence is lacking to recommend cell therapy over non-cell-based procedures, however both appear to be beneficial when indicated. Longitudinal data for non–stem cell therapies, such as ACI, mosaicplasty, and microfracture at present, far exceed the available data set for cell implantation, augmentation, and biologic agents..37,38 The future will likely see an increase in utilization of biologic agents, but most importantly in the criteria for use focusing on consistent preparation of the tissues and methods to better direct the implanted agents as to achieve a more suitable homogenous cartilage state.39-43

PATHOGENESIS

Articular cartilage is a viscoelastic compound of chondrocytes, water, and extra-cellular matrix containing no immediate vascularity, lymphatics, or nerves.44,45 Cartilage is present in three different forms: hyaline, elastic, and fibrocartilage. Hyaline cartilage, the most abundant cartilage in the body, is found primarily in joint surfaces surrounded and bathed by synovial fluid. As joint surfaces contact each other, the amazingly low coefficient of friction of the articular cartilage allows for normal joint movement and is able to resist incredible compressive loads. Articular cartilage is not as resistant to shear forces that may be present when normal joint biomechanics are changed due to ligament injuries. Thickness of the articular cartilage is dictated by the amount of joint compression forces applied to joint surfaces. This is evidenced in the patella, which contains the thickest articular cartilage in the body.44,45

Two distinct types of articular cartilage pathologies will be discussed in this article: Osteochondritis Dissecans (Odissecans) and Osteochondral Defects (Odefect) of the knee. Although these pathologies involve similar structural injury, significant etiological and pathogenic factors should be understood and appreciated.

ANATOMY & BIOMECHANICS

Articular cartilage is composed of a collagen fiber ultrastructure (mostly Type II) and a dense extracellular matrix (ECM). Ninety-five percent of the cartilage volume is made up of this ECM, 70-75% is water, and with the remainder being organic materials such as collagen, proteoglycans, and other proteins.46 The main purpose of these organic components is to retain the water within the ECM.

Collagen is the key protein providing the structural and mechanical properties of general connective tissue. The abundant proteoglycan molecules found in various concentrations throughout articular cartilage, due to their large size and immobility within the collagen fiber meshwork, act as the ‘pump’ of the highly pressurized system. This is the mechanism by which water (as well as the nutrients it carries) is introduced within the tissue.46,47

Articular cartilage is roughly 2-4 mm thick and contains four separate zones: superficial (tangential), middle (transitional), deep, and calcified.

The superficial zone makes up 10-20% of the cartilage thickness. This zone contains a high concentration of flattened chondrocytes, providing protection to the deeper layers. It is also responsible for absorption of the majority of the tensile and sheer forces applied to the tissue. This is due in large part to the tightly packed, high concentration of collagen fibrils aligned parallel to the joint surface.47

The middle zone of the articular cartilage provides a functional bridge between the superficial and deep zones. It is the largest of the zones, accounting for 40-60% of the total volume. It contains a higher concentration of proteoglycans as well as collagen fibrils thicker than those found within the superficial zone. These fibrils are arranged obliquely and account for the first line of resistance to compressive forces. The chondrocytes in the middle zone are more spherical and found in lower concentration.47

The deep zone makes up the final 30% of the articular cartilage, and gives the greatest resistance to compressive forces. This is due to the high concentration of proteoglycan within this zone as well as the collagen fibrils, which are larger here compared to the other zones, and are arranged perpendicularly to the joint surface. The chondrocytes in the deep zone are arranged columnar, and parallel to the collagen fibrils.47

The calcified zone anchors the collagen fibrils of the deep zone to the subchondral bone. The calcified and noncalcified collagen fibrils within these deep two layers are separated by a boundary called the tidemark.47

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Articular cartilage itself has no innervation or blood supply, therefore it requires motion for nutrition from joint fluid. The nearest pain receptors to the articular surface are located in the subchondral bone. The natural effects of aging on articular cartilage involve collagen framework damage due to the loss of proteoglycans. During the breakdown of the collagen framework, the arthritic a process begins with fibrillation, the formation of scar tissue-like fibrocartilage, poorly suited for managing compressive and shear forces.44,47 As earlier stated, articular cartilage exists without vascularity and lymphatics. Nutrition is supplied via the surrounding synovial fluid through diffusion, enhanced by joint loading and motion. When a load is applied across the joint, tissue compression occurs, displacing water molecules from within the tissue. When the load is removed, the proteoglycans are allowed to swell, drawing in new water molecules (and nutrients) and restoring equilibrium.48

Although the anatomy of articular cartilage provides resistance to wear and tear, breakdown will eventually occur. Many risk factors have been suggested to contribute to cartilage pathology including age, heredity, joint malalignment, obesity, metabolic diseases, and joint trauma.49 This commentary will focus on articular cartilage injury in the PF joint due to its relatively high incidence in sports.

It is important to note that lack of knee extension or flexion range of motion post-operatively can be a factor in the development of PF chondral injury. For example, lack of extension is most often caused by posterior joint tightness/stiffness or anterior interval impingement and patellar hypomobility. This lack of extension directly leads to a flexed-knee gait pattern that places the PF articular surfaces at risk. As the individual bears weight through a flexed knee, the PF joint reaction forces increase and lead to increased compression of the patella in the trochlear groove. These excessive compressive forces can lead to damage of the articular side of the patella.44,50

OSTEOCHONDRAL DEFECTS (ODEFECTS)

Within the athletic population, cartilage injury often occurs due to acute or chronic mechanical overloading, malalignment causing asymmetrical loading patterns, or chronic under loading leading to disuse atrophy. Injury to the articular cartilage most typically occurs due to a twisting injury or high impact forces sustained through the joint during sporting activities. In these cases, the area of injury is often localized and termed a focal articular cartilage, or chondral injury. Although the exact pathophysiology is not completely understood, it is widely speculated that focal injury causes damage to the chondrocytes, proteoglycans, and collagen fibrils located in the deeper layers of articular cartilage. When joint forces surpass the threshold of compressive or shear loading for this tissue, irreparable harm is done to the deep layers, which can include the subchondral bone. This insult to the subchondral bone can lead to the death of local chondrocytes and calcification of the involved hyaline cartilage, as well as fibrillation within the margins of the defect.49 Over time, these traumatic focal lesions can take the appearance of a progressively degenerative wear patterns.50

Due to its avascular qualities, articular cartilage injuries have low affinity for independent regeneration. Partial-thickness defects (those not penetrating through to the sub-chondral bone) may worsen over time as degeneration happens in addition to the focal damage. Full-thickness defects can potentially fill with a form of secondary scar tissue by way of native stem cell differentiation due to the vascularity of the underlying bone. This scar tissue is largely fibrocartilage, containing different load compliance than native hyaline cartilage, which originates from the marrow cavity and local stem cells.50 Because this Type I collagen is not as durable as the Type II hyaline cartilage that existed previously, the resulting surface of the bone is vulnerable to additional deterioration and pain.

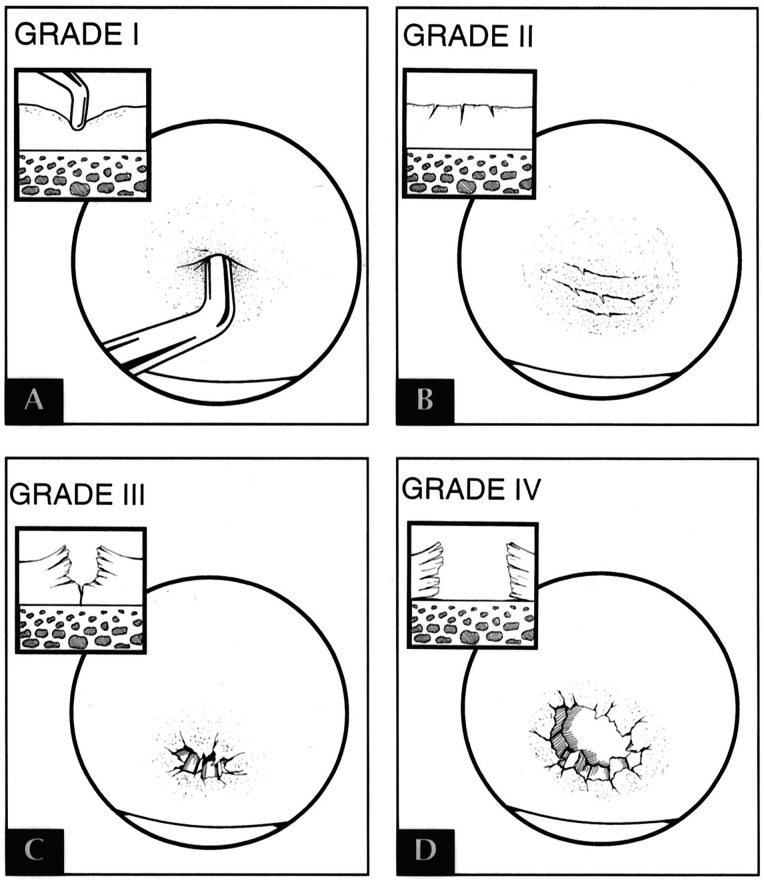

As the articular surfaces of a joint sustain injury and/or deteriorate, pain and functional limitations may increase. The severity of these symptoms depends on the scale of the damage to the chondral surface. This can be graded based on depth and size of the cartilaginous defect.48,50 The Outerbridge Classification51 is commonly used to describe the extent of chondral damage, and is scored as follows: 0 = Normal cartilage; I = Cartilage with softening and swelling; II = Fragmentation and fissuring in an area half and inch or smaller in diameter; III = Fragmentation and fissuring in an area larger than half an inch; IV = Erosion of cartilage down to subchondral bone. Typically, the higher the lesion, the more impact it has on a person's functional tolerance.

Chondral damage can result from various etiologies, but these generally fall into two categories: traumatic and insidious. In an orthopedic setting, traumatic injuries during athletic activities are among the most common causes of chondral lesions. A less common cause typically found in younger populations, is Odissecans.50 Odissecans have been found to be more commonly associated with structural abnormalities, including patellar malalignment or instability. These abnormalities must be corrected in order to provide the best possible outcomes following cartilage repair. Valgus or varus malalignment of the lower extremity is a good example of such an abnormality, and can result in overload of the medial or lateral compartment and lead to degeneration of the articular surface.

Ligamentous compromise (i.e. anterior cruciate ligament [ACL] injury) and/or meniscal insufficiency leads to increased sheer forces on the articular cartilage of the knee, and can result in subsequent chondral degeneration. This is an important consideration when evaluating the need for cartilage procedures. In the case of previous meniscal damage or meniscectomy, up to three times the joint forces can be placed on the involved compartment, leading to the advancement of arthritic changes. In certain patients with insufficient meniscal tissue, transplantation of allograft meniscal tissue can be used to allow for improved function and decreased pain.50

Noyes et al52 found an incidence rate for chondral damage of 6-20% in arthroscopic examinations of knees with acute hemarthrosis. They also found a higher incidence of chondral damage in knees that sustained a mechanism of injury consistent with those that produce ACL tears. These chondral lesions led to greater instances of long-term symptoms including pain, catching and swelling, especially with impact activities. Curl et al53 looked at the prevalence of chondral injuries in a review of over 31,000 knee arthroscopies. Not only did they find that 63% of patients had sustained hyaline cartilage lesions, but discovered a total of over 53,000 lesions, a number far larger than the observed knees indicating that many had multiple sites of damage. The most common sites reported were the medial femoral condyle and the patella.

In young athletes, traumatic hemarthrosis is associated with chondral defects in up to 10% of knee injuries. Due to the mechanism of injury, patellar dislocations are strongly associated with Odefects to the articular surface, and occur at a rate up to 95% of the time. Odissecans is estimated to occur in 30-60 cases per 100,000.50 Most of the time, these defects are initially found upon arthroscopic examination of the knee during meniscal or ligament reconstruction procedures. It is important to note that although this incidence may seem high, many of these defects are asymptomatic and found to be incidental.

OSTEOCHONDRITIS DISSECANS (ODISSECANS)

Odissecans describes the pathologic condition involving delamination and/or sequestration of the subchondral bone from the underlying tissue.32,45 It is important to understand this condition as a different and specialized chondral injury separate from that of an Odefect, which identifies any breakdown of the articular cartilage. Although the conditions can present symptomatically similar, treatment and management are notably different.

The initial reports of the condition date back to 1870 by Paget who deemed the condition “Quiet Necrosis”, only to be further expanded and coined Osteochondritis Dissecans by Konig in 1887, reporting the pathologic process as the result of inflammation of the subchondral bone and articular cartilage.32,45,54 Research and epidemiological studies over the last century have somewhat disproven this hypothesis and thus identified the term “chondritis” as incorrect, dispelling the condition as inflammatory. However, subsequent comprehensive research has failed to completely identify the etiology and natural history for the pathology.45,54,55 Areas of interest include: genetic predisposition, defective skeletal development, vascular insult, repeated trauma, and altered joint/cartilage loading mechanics. With respect to the disease process, the death of the subchondral bone as a primary or secondary factor eludes current understanding and leaves a large area of future focus.32,55

Statistically, the incidence of Odissecans has been reported by multiple sources to be around 15 to 29 per 100,000 patients, with the knee being the joint most affected.55 Odissecans pathology is most frequently seen in patients in the second decade of life, affecting males greater than females (5:3, respectively).55 There is reason to believe the incidence is a result of higher activity participation within the second decade, while statistical gender trends are shifting, with comparable female to male shifts due to the increasing sports participation in females.55,56 Risk factors, historical markers, and genetic identifiers are important to consider, although their exact contribution is unclear at this time.

The pathology is commonly associated with mechanical symptoms, joint effusion, pain, and significant functional limitation involving a spectrum of daily activities. Management is largely based on the combination of all of the above factors ranging from age and activity of the patient, to the type of injury, and ultimately the stability of the involved area. Odissecans pathology is often divided into juvenile Odissecans, occurring in an individual with open physes (average age 14 years) and reported as more common, or adult Odissecans, those with closed physes (average age 26 years).32 A shift in the average age has expanded in both directions as sports participation has seen a shift in early sports participation specialization as well as increases sport longevity and participation later through life.55-57

PF Odissecans, accounting for a large majority of the epidemiological Odissecans cases, varies in treatment recommendation due to the lack of empirical data and breadth of the etiological risk factors. Three distinct locations can be identified within this region: the retro-patellar region, the medial femoral condyle, and lateral femoral condyle. Although the general rehabilitation philosophy remains consistent, certain factors will be adjusted based on PF joint mechanics and loading patterns with exercise. The trochlear groove of the PF joint is the rarest location in the knee for Odissecans and accounts for 0.6% of all Odissecans in the knee.

EXAMINATION AND DIAGNOSIS

Physical Exam and Subjective Reports

Diagnosis of articular cartilage lesions of the knee can be a protracted process as symptoms are often vague and intermittent depending on the activity level of the patient, and at first, presentation can be mistaken for more innocuous PF instability or general dysfunction. Despite its challenges, prompt identification of these lesions is critical to successful management as earlier application of the most appropriate intervention provides superior clinical outcomes with prevention of continued joint degradation.58,59

Odissecans and Odefects have similar clinical presentations, and distinction between the two lesions is difficult to establish through physical examination alone. Diagnostic imaging, however, reveals clear distinctions between the two pathologies and requires varying surgical and rehabilitation protocols depending upon the type of lesion. As such, Odissecans and Odefects will be treated as one entity during the physical examination review but will be handled separately for the imaging discussion.

Individuals with cartilage lesions typically complain of activity-related pain, recalcitrant effusion, and catching or locking of the joint.58 Symptoms are usually exacerbated by weight-bearing and high-impact activities and alleviated by a period of rest. The clinical examination can assist with ruling out ligamentous instability and meniscal pathology, but it remains difficult to rule in chondral defects, as common clinical tests are unreliable (i.e. Wilson's Sign, Clark's Sign). Common findings include bony tenderness with palpation on or near the chondral lesion, antalgic gait pattern, and loss of range of motion secondary to effusion, prolonged guarding, or loose body entrapment.58,60

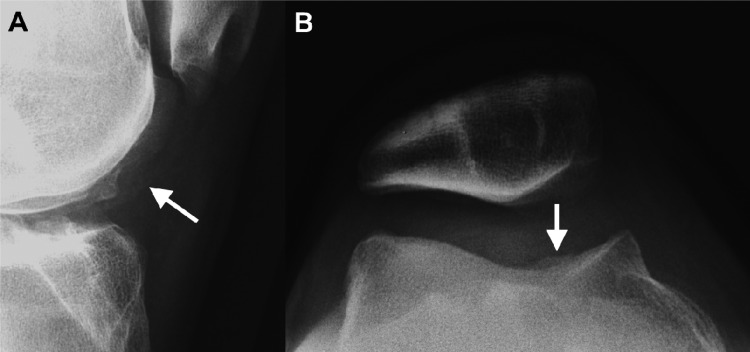

Imaging: Osteochondral Defects (Odefects)

The mainstay of clinical diagnosis remains with radiographic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies as these provide the most accurate insight to allow proper identification and staging of the cartilage lesion apart from arthroscopic investigation. Although with less diagnostic accuracy than MRI, plain radiographs are indispensable in early diagnostic work-up and are typically the first line of imaging ordered. For patellar lesions and assessment of PF articulation, sunrise or merchant views are of greatest utility, and weight-bearing anterior-posterior views can also be valuable. These primary images can rule out other bony pathology, reveal lesion location and extent of degradation, and guide decisions regarding further diagnostic workup.58

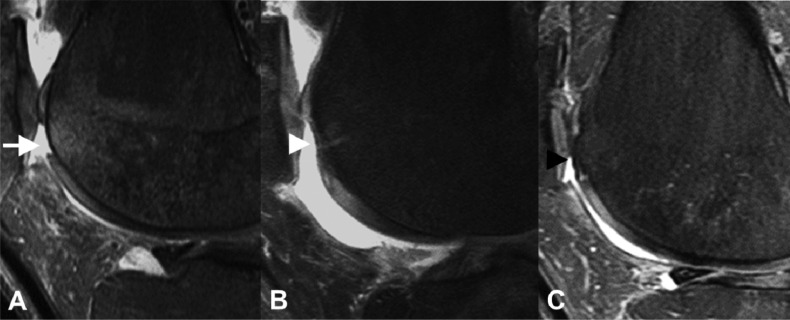

Secondary imaging via MRI is recommended to allow more accurate pre-operative classification of chondral lesions with regard to severity and size, which will then guide pre-operative decisions on which reparative or restorative surgical technique to implement. Additionally, for any articular cartilage pathology of traumatic origin, MRI can allow more complete assessment of the underlying subchondral bone and the osteochondral interface than arthroscopy alone, which can miss microtrabecular fractures (bone bruises).61

Once a diagnosis has been established, treatment recommendations can be made based on size, stability, and location of the lesion. Other prognostic and factors that must be included in the surgical decision-making process include age, skeletal maturity, BMI, and the patient's desired activity level; however, for most high-level athletes, surgical intervention is essential to enable unrestricted return to play.59

Imaging: Osteochondritis Dissecans (Odissecans)

As with Odefects, plain radiographs are typically the first diagnostic imaging ordered prior to advanced imaging via MRI. Lateral and tunnel (notch) profiles are best suited in visualization of Odissecans lesions. These primary radiographs allow for gross assessment of cartilage integrity, localization of larger lesions, staging of the lesion. These films also allow assessment of bone age in the youth population, which is of particular value in determining patient prognosis as younger individuals with open physes have a much stronger prognosis with conservative management alone.45,58

After plain films have been obtained, MRI is required for complete investigation of the lesion. Key imaging findings include distinct chondral fragments, discrete loose bodies, high T-2 signal intensity between parent and progeny bone, and disruption of the chondral surface.58 The value of MRI can be superior to that of direct visualization via arthroscopy as it allows more complete assessment of the underlying subchondral bone and the osteochondral interface, which can be missed intraoperatively with stable Odissecans lesions.58,59

SURGICAL INTERVENTION

Surgical management is generally considered after adequate nonoperative management has failed to provide acceptable pain relief or if after establishing that a patient's symptoms are secondary to a full thickness (Grade 3 or 4) cartilage defect. It is important to remember that one must view the management of PF cartilage injuries in a slightly different manner. The current literature unfortunately reveals that the PF compartment is a difficult location for cartilage repair and that all recognized techniques performed here have lower success rates than similar techniques performed on the femoral condyles. While microfracture, osteochondral autograft transfer, osteochondral allograft transplantation and ACI have shown good clinical outcomes in the femoral condyles, there exists a growing consensus that these procedures should all be used prudently in the PF compartment, except in certain specific situations.62 In one study, microfracture in the PF compartment demonstrated transient improvement, with worsening outcomes after eighteen to thirty six months.63 Osteochondral autograft transfer used in the PF joint has mixed results with one study showing only slightly worse results than that seen in the femoral condyle,64 yet another study demonstrated disastrous results with nearly universal failure with OATS performed for a defect in the patella.65 Osteochondral allografts performed in the PF compartment have shown good results, with 60% good to excellent outcomes reported by Jamali et al.66 ACI has recently demonstrated much improved outcomes with >80% success seen in the PF joint despite initial studies reporting disappointing results.67-70 While a defect in the patella remains an off-label indication for ACI, this repair option now represents the procedure of choice for all but the smallest defects in the PF joint. However, it remains crucially important to correct any malalignment and abnormal patellar tracking, regardless of which surgical repair option is used, as these predisposing conditions will likely lead to a universal failure of any procedure performed if not appropriately addressed.

Small and Medium Sized Cartilage Defects (<2-4 cm2)

The initial treatment for small to medium sized (<4 cm2) symptomatic cartilage lesions, after a patient fails nonoperative management, generally begins with an arthroscopic debridement and chondroplasty of the defect. This involves excising degenerative tissue around the defect and creating a mechanically stable lesion with the use of arthroscopic shavers, basket forceps and curettes. This can be the definitive treatment for the majority of patients or an initial procedure before contemplating more invasive repair options. Patients recover from this procedure quickly, can be made full weight bearing as tolerated and can return to full activity, including return to running and cutting sports when pain and swelling have disappeared.

Microfracture and OATS (speaking to Odefects specifically) are also viable options in the presence of slightly larger defects or having failed a previous debridement with chondroplasty. These procedures involved graduated weight bearing progression and long-term rehabilitation time frames. This will be discussed at more below.

Large Sized and Complex Cartilage Defects (>2-4 cm2)

When managing larger (3-4 cm2), full thickness focal chondral lesions in the trochlea (or femoral condyles), ACI is a good technique that is indicated for these more complex injuries. This is accomplished via a two staged procedure, first assessing the lesion arthroscopically to make sure it is contained and that the depth of the lesion does not exceed 8 to 10 mm, which would require bone grafting. The second stage of the operation, a limited or more extensive medial or lateral parapatellar arthrotomy is required because adequate exposure is paramount.

OATS in the PF joint is typically reserved for use in younger patients without signs of arthritic changes when revising a prior failed cartilage repair. This is done to implant a side and sized matched, fully developed cartilage that does not need to heal. The allograft bone requires healing, however, and acts as a scaffold, which incorporates over time. However, OATS at the trochlea or patella becomes challenging given the complex anatomy to be transplanted. A shell allograft, much like used when performing PF arthroplasty, can be used for more extensive lesions in the trochlea. Press fit cylindrical plugs are typically used for isolated patellar facet lesions or for more extensive patellar defects, patellar allograft resurfacing is a good option using double pitched screws placed from anterior to posterior. This procedure requires adequate visualization, so an open approach is performed. Contraindications to OATS include inflammatory arthropathies (rheumatoid or other systemic arthritis), advanced degenerative changes, corticosteroid induced osteonecrosis, knee instability or malalignment.

Odessicans is managed based on the pathoanatomy of each individual lesion. These are typically addressed arthroscopically. If the lesion demonstrates intact articular cartilage, it is best to drill the lesion in a retrograde fashion to not violate the articular cartilage. This promotes revascularization and healing. For separated lesions, these can be managed by curetting and drilling the base of the crater, followed by replacing the fragment and using a stabilizing fixation technique with compression screws, bone pegs or biodegradable pins. Excision is reserved for small fragments, which are not amenable to fixation.

MANAGEMENT: APPRECIATING PATELLOFEMORAL BIOMECHANICS

Having a working knowledge of the PF joint allows the clinician a distinct advantage when designing and implementing an appropriate rehabilitation program for those patients suffering from PF articular cartilage lesions. The goal of the following section is to merge current science to practical application of rehabilitation exercise and functional progression.

The primary function of the patella is to increase the efficacy of the quadriceps muscle via increasing the moment arm, thus producing greater knee extension torque. When the knee is extended in an non weight bearing (NWB) position, the patella is pushed forward by the trochlear groove of the femur.71 When extending the knee beyond 45 degrees, the lever arm function of the patella diminishes (height of the patella decreases as the patella begins to exit the trochlear groove). This has significant impact when considering contact forces during traditional exercise selection.71

Goodfellow et al72 described the various contact regions of the patella during various knee flexion angles. These angles were identified according to the articular facets viewed on the posterior surface of the patella. Initial contact of the patella was identified at 10 degrees of flexion. From full extension to 90 degrees flexion, the area of contact migrated consistently from the inferior articular portion to the superior portion of the patella. After greater than 90 degrees flexion, the odd medial facet began to experience consistent contact stress. And finally, at approximately 135 degrees of flexion, contact moves and is distributed on the patella's lateral and odd facets. Any imbalance in contact and compression stresses that has occurred can lead to articular degenerative changes.72

Appreciating the forces applied to the PF joint throughout biomechanical knee range of motion is important to understand the compressive loads and stresses sustained by the articular surfaces of the patella. As the knee articulates from terminal extension to flexion, the pull of the quadriceps tendon (either actively or passively) and the pull of the patellar tendon further compresses the patella into the femur. This patellofemoral joint reaction (PFJR) force is then expressed as the resultant vector force equal and opposite to the pull of the quadriceps and the patellar tendon. As knee flexion increases, the angle between the quadriceps tendon and the patellar tendon becomes less and thus increases the resultant vector force. Excessive compressive forces can produce damaging stresses on the articular cartilage of the patella, specifically when tissue healing is a priority.73-76

Weight-Bearing Exercises and Patellar Function

PF compressive forces have been shown to increase as knee flexion increases during weight bearing exercises, such as the squat, leg press, and stationary bicycle, as well as normal daily activities such as stair climbing/descent and walking.73,74,77

Reilly and Martens76 calculated forces present with normal activities of daily living. Walking on level ground showed minimum PFJR force (PFJR = 0.5 × body weight [BW]) because minimum knee flexion is required. When knee flexion angles increase, such as squatting to 90 degrees, the PFJR forces increased to 2.5 to 3 times body weight. Descending stairs always is difficult for an individual with PF pain. During descent, the peak PFJR forces reach 3.3 × BW at 60 degrees of knee flexion. When descending stairs with articular cartilage lesions, maximum quadriceps force occurs near 30 degrees of flexion. This is the region where most lesions are present. When you combine large quadriceps eccentric loading with this “kissing lesion” position, pain is much more prevalent when descending stairs. The opposite is true with stair ascending. The maximum quadriceps compressive load occurs near 80 degrees of flexion during stair climbing where there is normally no PF articulation or a lesion. As the PF joint passes through the lesion of 30-40 degrees, there is very little compressive force being applied, thus less pain and discomfort with ascending stairs. Additionally, activities such as the leg press are much more comfortable than open chain knee extension. With closed kinetic chain activities such as this, PFJR force increases with increased flexion, and the area of contact also increases. This increased area of contact can respond effectively to disperse these forces.73,75

Nisell and Ekholm75,78 determined that squatting in flexion ranges greater than 90 degrees produces significant compressive forces between the quadriceps tendon and the intercondylar notch of the femur due to increased muscular recruitment of the quadriceps and hamstrings, however it also increased gluteal recruitment. It is important to note that the magnitude of force is affected by variables in squatting mechanics (positioning of the ankles, knees, and hips).79,80 As the knee migrates forward, beyond the toes, the PF joint will sustain higher loads compared to a more posteriorly oriented pattern; however this does transfer larger forces to the hip and low back regions, while decreasing the PFJR.81 The PF compressive forces are greatest at 70 °-120 ° of knee flexion,74,75 with the magnitude described by Thambyah et al82 to be as high as a 4 times body mass at 90 degrees and as high as a 5 times body mass at 120 degrees. Wrentenberg83 and associates studied the effects of low-bar and high-bar positioning during the squat. The high-bar position produced significantly greater PF compressive forces, as the high-bar position tended to produce a more upright trunk posture and required more knee extensor torque to complete the squat (and less hip extensor torque). For individuals with PF arthritic symptoms, limiting the magnitude of knee flexion to an appropriate symptom-free range can minimize PF stresses. Individuals with PF articular cartilage concerns may need to avoid squatting into angles greater than roughly 60 degrees as it increases the compressive force exposures.84-86

Non-Weight-Bearing Exercises and Patellar Function

Understanding the forces that act on the PF joint at different positions (weight bearing (WB) and NWB) allows the clinician to develop a program based on empirical evidence. Biomechanical knowledge in action is illustrated by the interaction between the PF contact area and the PFJR force during the leg press (and other WB exercises) and leg extension (NWB) exercises.

Steinkamp and coworkers77 showed mathematically that maximal PFJR forces during the leg press occur when contact between the PF surfaces is greatest (60 and 90 degrees), whereas the maximal PFJR forces during a leg extension occur when the PF contact is the least (0 and 30 degrees). Although compressive forces may be lower for leg extensions, patients with patellar articular degeneration and arthritic changes often experience pain during NWB extensions of 30 to 0 degrees as a result of the relatively large compressive forces being applied to minimal contact areas.

Steinkamp77 concluded that patients with PF joint arthritis may tolerate leg press exercises (or similar WB squatting exercises) better than leg extension exercises in the final 30 degrees of knee extension because of the lower PF joint stresses. These investigators also determined that the PFJR forces are less in open chain exercises than closed chain exercises from 90 to 60 degrees, which Brownstein and associates87 found to be the range in which the greatest vastus medialis EMG activity was registered.44

MANAGEMENT: POST-OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS AND PROTOCOL

Careful consideration should be taken post-operatively to protect the repaired lesion and promote tissue healing. The tenuous status of the tissue in conjunction with loads experienced throughout PF articulation make this area more difficult to manage. General healing timelines must be respected and are provided in most protocols, however, the timelines must also consider the variability in operative procedures and patient demographics as part of the rehabilitation continuum.

Appreciating this concept, the use of specific clinical tests or criteria in physical therapy, along with healing timelines, is prudent to assess the patient's progress towards beginning certain functional activities. For example, adequate knee range of motion and neuromuscular control of the quad are needed in order to begin walking without an assistive device and without compensation. Through the therapist's guidance (with approval from the surgeon), chondral graft healing times and evidence based criteria are used in each phase of the recovery to identify when the patient is ready to walk, run, perform agility drills, jump, cut and finally return to sport. The post-operative milestones provided contain the criteria and measurement tools needed for treating patients undergoing various chondral procedures. Modifications are necessary for patients who have undergone concomitant ligamentous repair or reconstruction as well as other procedures and/or injuries, which may influence or delay their recovery. The surgeon in these situations typically makes specific recommendations.

MANAGEMENT: POST-OPERATIVE HEALING TIMEFRAMES AND PHASES OF LOADING

The following tables represent post-operative recommendations, tissue-healing timeframes, and biomechanical loading literature based on surgeon collaboration (Table 1).

Table 1.

Procedure Specific Timeframe Considerations

| Microfracture | OATS / Mosaicplasty | Osteochondral Auto and Allograft Transplantation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight-Bearing Status | NWB Weeks 0 – 6 | NWB Weeks 0 – 6 | NWB 0 – 6 | |

| Brace | Locked in extension during ambulation, unlocked during PROM as indicated below | Locked in extension during ambulation, unlocked during PROM as indicated below | Locked in extension during ambulation, unlocked during PROM as indicated below | |

|

Unloaded PROM (i.e. CPM, heel slides) |

0-30° | Week 1 | Week 1 | Week 1 |

| 0-60° | Week 2-3 | Week 2-3 | Week 2-3 | |

|

> 60° progress as tolerated |

Week 4+ | Week 4+ | Week 4+ | |

| Loading in Flexion |

0-30°

(i.e. mini squats, 4-inch step ups) |

Week 6 | Week 6 | Week 6 |

|

>30° (i.e. chair squats, deeper leg press) |

Week 8 | Week 10 | Week 10 | |

| Post-Operative Progression Time Frames | ||||

|

Phase I: Unloading |

Weeks 0 – 6 | Weeks 0-8 | Weeks 0-8 | |

|

Phase II: Moderate Loading |

Weeks 6 – 12 | Weeks 8-20 | Weeks 8-24 | |

|

Phase III: Advanced Loading |

Weeks 12 – 24 | Weeks 20-32 | Weeks 24-36 | |

|

Phase IV: Return to Function |

Week 24+ | Week 32+ | Week 36+ | |

Progression should always involve the corresponding surgeon, as they will have perspective on the tissue quality and recovery expectation. Healing timeframes should always supersede criteria, regardless of the patients' level of function. Table 1 represents three distinct time frames based on the type of intervention performed.

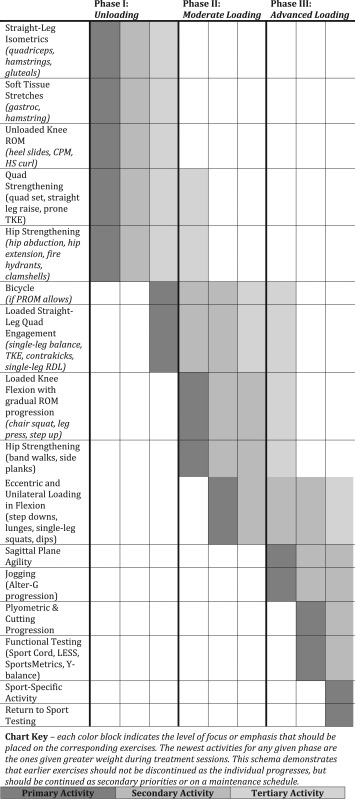

Biomechanical loading principles should also be incorporated into the rehabilitation progression as to promote protection or gradual tolerance of the involved region. Table 2 outlines three phases pertaining to PF joint load while also providing examples of these exercises for each phase.

Table 2.

Exercise Selection Based on Tissue Loading

|

MANAGEMENT: PROGRESSION USING LOADING PHASES

The following describes the loading phases in more detail while providing insight into rationale pertaining to the protocol's progression.

Phase I: Acute or Unloading

The goal of the initial phase is protection of the surgical site, while promoting general joint nutrition and fluid dynamics within the protected ranges of motion and, most importantly, avoiding excessive compressive and sheer forces to the surgical site. Phase I exercises should utilize the biomechanical principles outlined above to mitigate any unnecessary force to the area. This includes avoidance of specific ranges of motion and/or strength exercises that involve joint load.

The acute post-operative phase of knee rehabilitation is the most essential to patient success, as early complications are commonly predictive of long-term impairments. The goals of the acute phase are to eliminate effusion, emphasize ambulation without asymmetries, obtain full knee extension, progress flexion range of motion, and restore normal quad activation. This terminal extension is extremely important to achieve as early as possible, as it may become increasingly difficult to obtain as time passes. Elevation of the involved extremity for the first few days will help control swelling. Cryotherapy can also be used up to 4-5 times per day for 10-20 minutes each time to help control pain and swelling. Quad sets are a staple of early post-operative rehabilitation. If performed correctly, they not only help with quad activation but can also provide terminal knee extension. Special attention should be paid to posterior capsule tightness in the knee and anterior interval mobility, in order to ensure the restoration of normal biomechanics of the joint. Open kinetic chain strengthening, such as short and long arc quadriceps should be avoided in this phase.

Towards the end of this phase, approximately 3-6 weeks post-operatively, gradual weight bearing is initiated with the release from the surgeon. It is recommended the patient progress weight bearing using crutches while avoiding stair negotiation and incline ramps in this phase.

Phase II: Moderate Loading

Phase II, approximately 6-12 weeks post-operatively, marks a continuation of joint protection, returning soft tissue flexibility and range of motion, and the beginning of the strengthening progression.

Progression of flexion range of motion is extremely important to prevent joint contracture. The patient should be educated on proper form and to avoid forced flexion if pain is felt. Strengthening should utilize closed chain strength modalities, such as leg press (with focus on the knee remaining posterior to the ankle joint), high table sit-to-stands (around 30 degrees initially), single leg balance, and minimal range open kinetic chain hamstring and gluteal exercises. Squatting to greater than 45 degrees should be closely monitored as this begins to place load on the joint. Bilateral strengthening should begin at less than the patients' body weight and progress to unilateral challenges as tolerated. It is recommended wall slides, heel slides, squats, step ups, lunges, and open kinetic chain knee extension exercises, be avoided in this phase. Cycling can be initiated in this phase with no resistance and controlled revolutions per min (RPM's).

Phase III: Advanced Loading

Advanced loading, occurring between 12 weeks to 24 weeks, represents the time frame focused on restoring normal kinematics. Focus is set on normalizing the patient's gait pattern, progression to full ranges of motion, and advancement of Phase II strengthening exercises. It is important to note that forced flexion should still be monitored throughout the rehabilitation process and reported to the surgeon if the patient continues to experience pain.

Due to the large forces placed on the joint during descending stairs, especially in the presence of muscular weakness, it is recommended the patient avoid stairs until adequate quadriceps strength is achieved. Continuation of cycling, now with resistance, and use of the elliptical trainer can be beneficial in improving joint nutrition, cardiovascular training, and movement patterning. Open kinetic chain quadriceps knee strengthening (pain free only) can be initiated in this phase, from 90 degrees to 30 degrees only. Progression of closed chain range of motion can progress, however squatting to greater than 90 degrees should be avoided until 20 weeks or clearance from the surgeon. Step up's and lunges (in progressive depths) are appropriate for this phase and should use assistance devices, like suspension straps and mirrors to teach and control form and diminish PF load. Wall sits and balance training are excellent interventions to enhance muscular endurance and proprioceptive control.

The overall goal of this phase is normalization of activities of daily living, gait, range of motion, and strength. Emphasis is directed to proper motor control during these tasks. Time should be taken to learn proper squatting mechanics, as this movement is the basis for improving functional mobility, such as the ability to rise from a seated position. Regaining and developing good quadriceps and hamstrings strength is essential to help improve the patient's ability to perform daily activities safely and with greater confidence. Further testing, such as functional movement screening, can be performed during this phase to assess for functional symmetry and impairments. Improving functional symmetry and attaining good control of the lower extremities and body is essential to progress to the “strengthening” phase of any rehabilitation program. Return to running progressions can begin in this phase, but should only be incorporated if this is required specifically for the patient's goals.

When attempting to return to higher-level activities such as running, initially alternating jogging/walking intervals should be performed, starting with one minute or one tenth of a mile intervals and progressing as tolerated. The time or distance should only be progressed when the patient can demonstrate normal gait pattern and when they can jog without any increase in pain or swelling in the involved knee. Straight-line running is recommended for the first few weeks, and treadmill or track surfaces are preferred over pavement, due to the decreased ground reaction forces. The treating physician will provide recommendations on the use of orthotics, as well as determine which activities these devices would be needed for.

Phase IV: Return to Function

It is important to keep in mind that individual patients will have a wide variety of outcome goals. For someone whose goal is to return to work activities and activities of daily living, the later power/agility and sport specific phases will be unnecessary.

Even for athletes, the time spent on each phase will be partially determined by a needs analysis (sport specific demands) for their specific sport. For example, volleyball or basketball players need to perform more explosive and higher impact movements than that of a cross-country runner. Although the general principles of exercise apply throughout the rehabilitation program, individualized programs are used to allow for return to activity at a high level, with minimized risk of re-injury.

Power and agility

The functional goals of this phase are to initiate dynamic agility, power and sport specific movements. These activities should be performed in a controlled manner and with proper body mechanics at all times. These programs typically begin with single plane movements (i.e. forwards, lateral) and progress to multidirectional and reactionary movements. Restoring power and strength in the involved lower extremity is essential to progressing to higher level sports specific activities in the next phase of the rehabilitation program. The primary variable throughout this phase is graded exposure of impact forces. Careful monitoring of the knee should be performed, in order to identify any effusion, pain or other adverse effects that may occur. Developing the patients' confidence and ability to perform higher-level movements safely and under control is paramount during this phase, as it has been shown to affect performance and risk of re-injury.

Sport-specific

During this phase, functional tests will be utilized for both training and assessment purposes. Functional testing, such as hop testing, functional movements screens, strength testing, and agility drills, is considered “best practice” to determine limb symmetry for strength and dynamic/agility movements. Athletes should be gradually transitioned from individual to team-based activities; and from practice to in-game competition. Movements should be progressed from anticipated to unanticipated to ensure the utilization of proper movement strategies. Towards the end of this phase, simulating sport-like activities is important in order to ensure the patient is comfortable with the demands of their sport.

Return to Sport Testing. For those patients wishing to return to athletic competition, our practice uses a cluster of tests to determine the readiness of the athlete to return to sport. The philosophy of these tests is to combine strength and functional assessments in order to gather an overall picture of the patients' athletic capacity. These tests include: The Y-balance anterior reach test, a single-leg hop for distance, the Landing Error Scoring System (LESS) test, a 40-yard Figure of 8 run, a 5-10-5 shuttle run, and an isokinetic test. The goal for clearance is less than a 10% deficit on the Y-balance, single-leg hop and isokinetic testing, and good body control and mechanics on the LESS, Figure of 8 run and shuttle run. Age-related norms are also used for the Figure of 8 and shuttle runs.88 The athlete should not have any symptoms throughout testing, and should have already achieved full range of motion and manual muscle testing values with no effusion or pain with activity. Typically, our physicians instruct our athletes to wear a functional brace until at least one-year post-operative. If the athlete fails to complete any phase of the return to sport testing, they are not cleared and should return to therapy until another test can be performed.

SUMMARY

The objective criteria outlined within this protocol were selected based on their known relationships with re-injury and complication rates after surgery. These progressions are undertaken with consideration of normal healing timelines and the procedures performed in surgery. Once completing the goals of each functional phase, the surgeon and therapist should give final approval prior to transition of the next phase.

CONCLUSION

Despite advances in cartilage procedures and techniques, the PF joint remains a difficult area to protect and restore to its pre-injury condition. PF pain can be very debilitating to any athlete and may progress to a level that causes cessation of a particular sporting activity. If possible, modification of activities to an unloading sporting activity such as cycling or swimming will help preserve and extend the life of the articular cartilage. The goal as rehabilitation professionals is to educate and inform patients regarding their lesions, build strength and endurance via an appropriate unloading program, and gradually load the competitive athlete with stress so that their injury will be able to accommodate the building phases of activity. Lastly performing functional and strength measures to objectively determine readiness for play. Understanding the risk factors and identifying at-risk behavior may help decrease PF joint loading and extend articular cartilage longevity, This commentary has presented a spectrum of available interventions, as well as proposed timeframes for post-operative progression. Biogenetic materials continue to be used in managing PF articular cartilage lesions, and as science validates their efficacy, future interventions using these modalities will be more clearly evident. Managing patient expectations, selecting appropriate joint loading exercises, and collaborating with physician partners is vital to achieve the desired outcome – return to pre-injury activity. Unfortunately with PF articular cartilage lesions, some athletes are unable to return to the pre-injury activity. Helping these athletes choose a competitive sport or recreational endeavor to continue an active lifestyle completes the rehabilitation effort, and.to prevent a more rapid destruction of their disease.

Figure 1.

Outerbridge classification system. Used with permission of the Journal of Orthopedics.

Figure 2.

Trochlear chondromalacia on radiographs. Lateral (A) and merchant (B) radiographs of the knee demonstrate undulation of the articular surface of the medial trochlea (white arrows), representing reactive proliferation of the subchondral bone indicating overlying chondromalacia.

Figure 3.

Trochear microfracture. A) Preoperative sagittal proton density fat-saturated knee MR image shows a full-thickness cartilage defect at the superior aspect of the trochlea with mild subarticular marrow edema (white arrow). B) Post-operative sagittal proton density fat-saturated knee MR image performed 3 months after microfracture demonstrates partial fibrocartilage fill of the microfracture site with minimal residual subarticular marrow edema (white arrowhead). C) Follow-up sagittal proton density fat-saturated knee MR image performed almost 3 years after the microfracture shows near complete fill of the microfracture site with a combination of fibrocartilage and reactive subarticular bone proliferation (black arrowhead). There is complete resolution of the subarticular marrow edema.

Figure 4.

Trochlear osteochondral allograph. A) Pre-operative sagittal proton density fat-saturated knee MR image shows a large full-thickness cartilage defect in the inferior central trochlea with minimal reactive proliferation of the subchondral cortical bone (white arrow). B & C) Post-operative sagittal proton density fat-saturated (B) and T1 non-fat saturated (C) images of the same region demonstrates interval placement of osteochondral allograph in region of previous full-thickness cartilage loss. The osteochondral graph is flush to the native cartilage with small fluid clefts at the interface between the native and transplanted cartilage (white arrowheads). There is complete osseous incorporation of the graft with normal bone marrow signal within the graft and absence of linear fluid-like signal or cystic change at the interface between the graft and native bone (black arrowheads).

REFERENCES

- 1.Frisbie DD Oxford JT Southwood L, et al. Early events in cartilage repair after subchondral bone microfracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003(407):215-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haggart G. Surgical treatment of degenerative arthritis of the knee joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1940;22-B:717-729. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Magnuson P. Joint debridement: surgical treatment of degenerative arthritis. Surgical Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1941;73:1-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruger T Wohlrab D Birke A Hein W. Results of arthroscopic joint debridement in different stages of chondromalacia of the knee joint. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120(5-6):338-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pridie KH. A new method of treatment for severe fractures of the os calcis; a preliminary report. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1946;82:671-675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Insall J. The Pridie debridement operation for osteoarthritis of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974(101):61-67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson LL. Arthroscopic abrasion arthroplasty historical and pathologic perspective: present status. Arthroscopy. 1986;2(1):54-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steadman JR Rodkey WG Rodrigo JJ. Microfracture: surgical technique and rehabilitation to treat chondral defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001(391 Suppl):S362-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulkerson JP. Anteromedialization of the tibial tuberosity for patellofemoral malalignment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983(177):176-181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fulkerson JP Becker GJ Meaney JA Miranda M Folcik MA. Anteromedial tibial tubercle transfer without bone graft. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(5):490-496; discussion 496-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shea KP Fulkerson JP. Preoperative computed tomography scanning and arthroscopy in predicting outcome after lateral retinacular release. Arthroscopy. 1992;8(3):327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gille J Behrens P Volpi P, et al. Outcome of Autologous Matrix Induced Chondrogenesis (AMIC) in cartilage knee surgery: data of the AMIC Registry. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2013;133(1):87-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anders S Schaumburger J Schubert T Grifka J Behrens P. [Matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte transplantation (MACT). Minimally invasive technique in the knee]. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2008;20(3):208-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins GM Peterson T Wicomb WN Halasz NA. Experimental observations on the mode of action of “intracellular” flush solution. J Surg Res. 1984;36(1):1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobi M Villa V Magnussen RA Neyret P. MACI - a new era? Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2011;3(1):10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pascual-Garrido C Slabaugh MA L'Heureux DR Friel NA Cole BJ. Recommendations and treatment outcomes for patellofemoral articular cartilage defects with autologous chondrocyte implantation: prospective evaluation at average 4-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37 Suppl 1:33S-41S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garretson RB 3rd Katolik LI Verma N Beck PR Bach BR Cole BJ. Contact pressure at osteochondral donor sites in the patellofemoral joint. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):967-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lexar E. Substitution of whole or half joints from freshly amputated extremities by free plastic operation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1908;6:601-607. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lonner JH Mehta S Booth RE Jr. Ipsilateral patellofemoral arthroplasty and autogenous osteochondral femoral condylar transplantation. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(8):1130-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leadbetter WB Kolisek FR Levitt RL, et al. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: a multi-centre study with minimum 2-year follow-up. Int Orthop. 2009;33(6):1597-1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dave LY Nyland J McKee PB Caborn DN. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in the sports knee: where are we in 2011? Sports Health. 2012;4(3):252-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedenstein AJ Piatetzky S II Petrakova KV. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1966;16(3):381-390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnstone B Hering TM Caplan AI Goldberg VM Yoo JU. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238(1):265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pittenger MF Mackay AM Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284(5411):143-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nejadnik H Hui JH Feng Choong EP Tai BC Lee EH. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells versus autologous chondrocyte implantation: an observational cohort study. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(6):1110-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichinose S Yamagata K Sekiya I Muneta T Tagami M. Detailed examination of cartilage formation and endochondral ossification using human mesenchymal stem cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32(7):561-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barry FP. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in joint disease. Novartis Found Symp. 2003;249:86-96; discussion 96-102, 170-104, 239-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barry F Boynton RE Liu B Murphy JM. Chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow: differentiation-dependent gene expression of matrix components. Exp Cell Res. 2001;268(2):189-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng H Martin JA Duwayri Y Falcon G Buckwalter JA. Impact of aging on rat bone marrow-derived stem cell chondrogenesis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(2):136-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubio D Garcia-Castro J Martin MC, et al. Spontaneous human adult stem cell transformation. Cancer Res. 2005;65(8):3035-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulz V Kochsiek K Kostering H Walther C. [The preparation of platelet-rich plasma for platelet counts and tests of platelet function (author's transl)]. Z Klin Chem Klin Biochem. 1971;9(4):324-328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulz JF Chambers HG. Juvenile osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: current concepts in diagnosis and management. Instr Course Lect. 2013;62:455-467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau D Ogbogu U Taylor B Stafinski T Menon D Caulfield T. Stem cell clinics online: the direct-to-consumer portrayal of stem cell medicine. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(6):591-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLean AK Stewart C Kerridge I. The emergence and popularisation of autologous somatic cellular therapies in Australia: therapeutic innovation or regulatory failure? J Law Med. 2014;22(1):65-89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLean AK Stewart C Kerridge I. Untested, unproven, and unethical: the promotion and provision of autologous stem cell therapies in Australia. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munsie M Hyun I. A question of ethics: selling autologous stem cell therapies flaunts professional standards. Stem Cell Res. 2014;13(3 Pt B):647-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Counsel PD Bates D Boyd R Connell DA. Cell therapy in joint disorders. Sports Health. 2015;7(1):27-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandelbaum BR Browne JE Fu F, et al. Articular cartilage lesions of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(6):853-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]