Abstract

We introduce msVolcano, a web application for the visualization of label‐free mass spectrometric data. It is optimized for the output of the MaxQuant data analysis pipeline of interactomics experiments and generates volcano plots with lists of interacting proteins. The user can optimize the cutoff values to find meaningful significant interactors for the tagged protein of interest. Optionally, stoichiometries of interacting proteins can be calculated. Several customization options are provided to the user for flexibility, and publication‐quality outputs can also be downloaded (tabular and graphical). Availability: msVolcano is implemented in R Statistical language using Shiny. It can be accessed freely at http://projects.biotec.tu-dresden.de/msVolcano/

Keywords: Bioinformatics, Data visualization, Interaction proteomics, Label free quantification, Web Application

Abbreviations

- AE

affinity enrichment

- AP

affinity purification

- LFQ

label‐free quantification

- QC

quality control

quantile‐quantile

The analysis of protein–protein interactions and complex networks using affinity purification or affinity enrichment coupled to mass spectrometry (AP/MS, AE/MS) is a commonly used technique in proteomics. The technology produces high quality protein interaction data 1 and is scalable to proteome‐wide levels 2. Even though isotope‐labeling methods have been developed to detect and quantify protein–protein interactions 3, label‐free approaches are gaining momentum due to their simplicity and applicability 4. While different quantification strategies exist for label‐free data, such as those based on spectral counting, methods that make use of peptide intensities (also known as extracted ion currents) are regarded as the most accurate 5, 6. Such methods generate the quantitative profiles of peptides or proteins across samples, which can be analyzed by established statistical methods, e.g. by a modified t‐test across replicate experiments 7.

MaxQuant is an integrated suite of algorithms for the analysis of high‐resolution quantitative MS data 8. Its MaxLFQ module normalizes the contribution of individual peptide fractions and extracts the maximum available quantitative information to calculate highly reliable relative label‐free quantification (LFQ) intensity profiles 6, which are exported as tab‐limited text files for the downstream analysis. Though various post‐processing tools to analyze the output of MaxQuant exist 9, 10, Perseus 11 is the most widely used tool.

To identify interactors of a tagged protein of interest (termed the “bait”), in the presence of a vast number of background binding proteins, replicates of affinity‐enriched bait samples are compared to a set of negative control samples. Although our primary application is protein interaction experiments, the workflow is generalizable to any case and control scenario. A student's t‐test or Welch's test can be used to determine those proteins that are significantly enriched along with the specific baits. A volcano plot is a good way to visualize this kind of analysis 12. When the negative logarithmic p values derived from the statistical test are plotted against the differences between the logarithmized mean protein intensities between bait and the control samples, unspecific background binders center around zero. The enriched interactors appear on the right section of the plot, whereas ideally no protein should appear on the left section when compared to an empty control (because these would represent proteins depleted by the bait). The higher the difference between the group means (i.e. the enrichment) and the p‐value (i.e. the reproducibility), the more the interactors shift towards the upper right section of the plot, which represents the area of the highest confidence for an interaction.

In any quantitative workflow, determining a threshold is a crucial step. This threshold sepa‐rates statistically significant outliers, which are most likely to represent biological findings, from background proteins, which inevitably occur in any measurement. Threshold placement can be performed empirically, or automatically based on desired false discovery rates, and often benefits from some manual optimization.

Downstream analysis of proteomics data can be challenging for a non‐specialized users and a burden for mass spectrometry core facilities. To facilitate the analysis and presentation of AE‐MS data, we present msVolcano, which is a user modulated, freely accessible web application. It requires the MaxQuant output of an interaction dataset that was analysed using the MaxLFQ module. LFQ intensity profiles retain the absolute scale from the original summed‐up peptide intensities 6, serving as a proxy for absolute protein abundance. The purpose of msVolcano is to implement all steps of downstream data analysis into a simple and intuitive user interface that requires no bioinformatics knowledge or specialized software. To this end, msVolcano automatically extracts relevant data columns, filters out hits to the decoy database and potential contaminants. A visual quality control (QC) output is generated allowing the user to monitor the correlation between replicates, fraction of missing values and behavior of the population of imputed values as shown in Fig. 2. Quantile‐Quantile (QQ) plots are also provided.

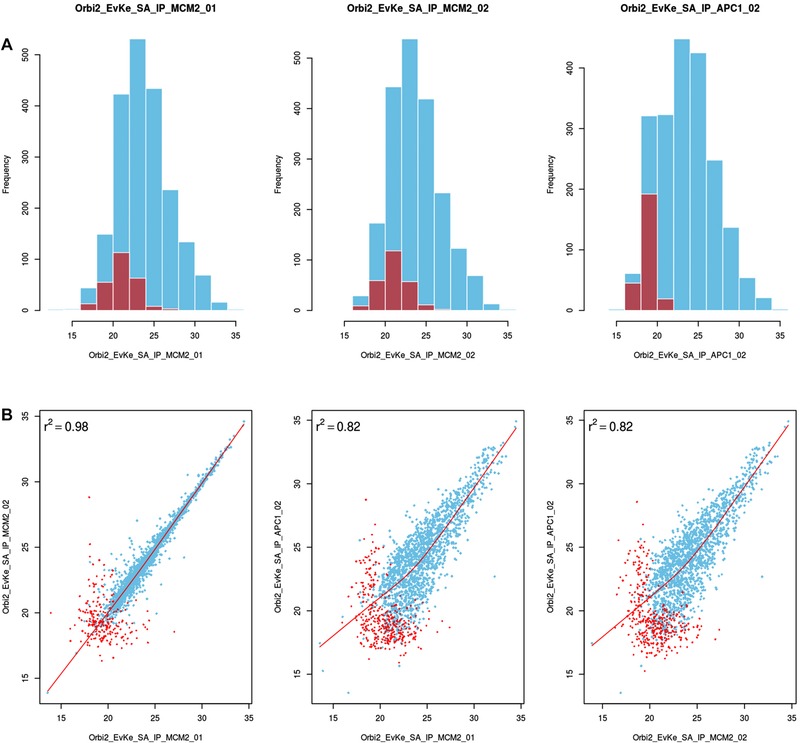

Figure 2.

QC plot using a dataset from budding yeast study (sample data in msVolcano) 14 (A) top row displaying the distribution of the raw values (LFQ intensites ‐ in blue) overlaid with the distribution of imputed values (in red) per LFQ column selected. For contrast, comparisons are done between unrelated sample replicates, which immediately become apparent in these plots and will also help the user to catch possible errors or sample mix‐ups. (B) 2×2 scatter plots between the chosen LFQ columns with local regression (lowess) displayed as a red line with Pearson's correlations coefficient. For the visual aestheticity, the number of scatter plots are restricted to the number of histograms displayed above them.

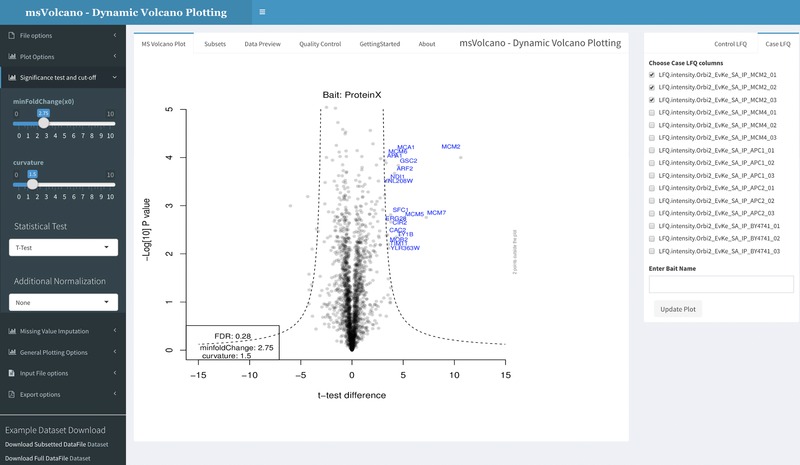

A user‐defined statistical test is then performed between selected bait and control samples and the tool generates a volcano plot as shown in Fig. 1. We implemented a recently introduced hyperbolic curve (dotted double lines in the volcano plot in Fig. 1) threshold 14, based on the given formula:

| (1) |

where c = curvature, x0 = minimum fold change, thus dividing enriched proteins into mildly and strongly enriched 14. The cutoff parameters can be adjusted by the user and monitored by the graphical output. The user has access to the plot aesthetics and can view the original input file and its subset for significant interactors in the inbuilt browser. A publication‐quality PDF plot can be generated and exported along with the subset of original data limited to the significant interactors. Next to the identities of interacting proteins, their stoichiometries relative to their bait are crucial for the understanding of the molecular function of protein complexes 2, 15. Thus, optional stoichiometry calculations have been implemented in the code. We use a modified version of intensity‐based absolute quantification (iBAQ) 16 for the estimation of protein abundance for stoichiometry calculations, where LFQ intensities are normalized by the number of theoretical tryptic peptides between seven and 30 amino acids, as described 2 (Fig. 1b). It has been shown that the number of theoretical peptides is a good and easily calculated proxy to control for the size and sequence properties of each protein that affect how much signal it can generate in the mass spectrometer. Theoretical peptides are pre‐calculated for the most commonly used proteomes of model organisms and are matched based on the proteins’ uniprot IDs. Stoichiometry calculations are based on the given formula

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where st = stoichiometry, sIp = size normalized protein intensity,

| (5) |

msVolcano provides a web‐platform for the quick visualization of label‐free mass spectrometric data and can be freely accessed globally. With the underlying hyperbolic curve parameters and other statistics, user can intuitively separate the true protein interaction partners from the false positives, without the need of writing code. With its ftp file input support, the user can quickly analyze and re‐analyse the results of the interactomics experiment present on their own cloud servers and along with the calculated optional stoichiometries, all the results can be exported in publication quality tabular or graphical format.

Figure 1.

Interface is divided into three sections, sidebar, body panel and column selection panel (left to right). Sidebar provides an access to the file upload, plot aesthetics, cutoff parameters, missing data imputation13, stoichiometry and the export options. The body panel has six different tabs, where the default panel labeled as “MS Volcano Plot”' displays the volcano plot. Second tab, “Subsets” displays the filtered input data for the significant interactors. “Data Preview” tab displays the user‐defined data for scrutiny. “Quality Control” tab displays a series of overlayed histograms, scatter and QQ plots helpful in assessing the correlation between the replicates, examining the distribution of the missing values and the behavior of imputed value population. “GettingStarted” and “About” tab display the specific and general information about the web interface. When user uploads a file or enters an ftp link, all LFQ columns are scanned and displayed in the column selection tab on the right side. User now selects respective bait and control columns (minimum two) and optionally enters the name of bait in the provided text box. As the “Update Plot” button is pressed, the plot is generated simultaneously.

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Systems Biology of Stem Cells and Reprogramming (SYBOSS) project funded by EU 7th Framework integrated project under the Grant Agreement No. [FP7‐HEALTH‐F4‐2010‐242129] and an EMBO long‐term fellowship to M.Y.H. (EMBO ALTF 1193‐2015).

Colour Online: See the article online to view Figs. 1 and 2 in colour.

References

- 1. Royer, L. , Reimann, M. , Stewart, Ais. , Schroeder, M. , Network compression as a quality measure for protein interaction networks. PloS One 2012, 7, e35729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hein, M. Y. , Hubner, N. C. , Poser, I. , Cox, J. et al., A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell 2015, 163, 712–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ong, S.‐E. , Mann, M., A practical recipe for stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC). Nature Protocols 2006, 1, 2650–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tate, S. , Larsen, B. , Bonner, R. , Gingras, A.‐C. , Label‐free quantitative proteomics trends for protein–protein interactions. J. Proteomics 2013, 81, 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Choi, H. , Glatter, T. , Gstaiger, M. , Nesvizhskii, A. I. , Saint‐ms1: protein–protein interaction scoring using label‐free intensity data in affinity purification‐mass spectrometry experiments. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 2619–2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cox, J. , Hein, M. Y. , Luber, C. A. , Igor, P. et al., Accurate proteome‐wide label‐free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13, 2513–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tusher, V. G. , Tibshirani, R. , Chu, G. , Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 5116–5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cox, J. , Mann, M. , Maxquant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized ppb‐range mass accuracies and proteome‐wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 1367–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Choi, M. , Chang, C.‐Y. , Clough, T. , Broudy, D. et al., MSstats: an R package for statistical analysis of quantitative mass spectrometry‐based proteomic experiments. Bioinformatics, 2014, 30, 2524–2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lazar, C. , Giai‐Gianetto, Q. , Gatto, L. , Dorffer, A. et al., Dapar & prostar: software to perform statistical analyses in quantitative discovery proteomics. Bioinformatics, 2016. https://master.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/Prostar.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tyanova, S. , Temu, T. , Sinitcyn, P. , Carlson, A. et al., The perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nature Methods, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hubner, N. C. , Bird, A. W. , Cox, J. , Bianca, S., et al., Quantitative proteomics combined with bac transgeneomics reveals in vivo protein interactions. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 739–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eberl, H. C. , Spruijt, C. G. , Kelstrup, C. D. , Vermeulen, M. , Mann, M. , A map of general and specialized chromatin readers in mouse tissues generated by label‐free interaction proteomics. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 368–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Keilhauer, E. C. , Hein, M. Y. , Mann, M. , Accurate protein complex retrieval by affinity enrichment mass spectrometry (ae‐ms) rather than affinity purification mass spectrometry (ap‐ms). Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2015, 14, 120–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smits, A. H. , Jansen, P. W. T. C. , Poser, I. , Hyman, A. A. , Vermeulen, M. , Stoichiometry of chromatin‐associated protein complexes revealed by label‐free quantitative mass spectrometry‐based proteomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwanhäusser, B. , Busse, D. , Na, L. , Dittmar, G. et al., Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 2011, 473, 337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]