Abstract

Background

Inadequate sleep hygiene may result in difficulties in daily functioning; therefore, reliable scales for measuring sleep hygiene are important.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to assess the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI).

Materials and Methods

From April 2014 to May 2015, 1280 subjects, who were selected by cluster random sampling in Kermanshah province, filled out the SHI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI), Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS), and insomnia severity index (ISI). A subset of the participants (20%) repeated the SHI after a four to six-week interval to measure test–retest reliability. Then, we computed the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients of SHI against PSQI, ESS and ISI, to demonstrate the construct validity of the SHI. The factor structure of the SHI was evaluated by explanatory factor analysis.

Results

The interclass correlation coefficient was 0.89, and SHI was found to have good test–retest reliability (r = 0.89, P < 0.01). The SHI was positively correlated with the total score of the PSQI (r = 0.60, P < 0.01), ESS (r = 0.62, P < 0.01) and ISI (r = 0.60, P < 0.01). Exploratory factor analysis extracted three factors, namely “sleep–wake cycle behaviors” (four items), “bedroom factors” (three items), and “behaviors that affect sleep” (six items).

Conclusions

The Persian version of the SHI can be considered a reliable tool for evaluating sleep hygiene in the general population.

Keywords: Persian, Psychometric Properties, Reliability, SHI, Validity

1. Background

Sleep, a basic essential for human growth and development, is one of the most important processes for optimizing physical, emotional and cognitive functioning and to keep good quality of life (1, 2). Sleep is the best form of rest, and refreshment and good quality sleep is necessary for a healthy and good life (3).

It has been shown that maturational changes occur in adolescents sleep biology, including a circadian phase delay (4). In combination with multiple biological and psychosocial factors (such as later bedtime and increased technology use), humans’ sleep may face problems, including short sleep duration, decreased sleep quality, shifts in sleep–wake patterns, and differences in sleep duration at weekends versus weekdays (4-10).

Impaired sleep quality has been shown to cause mental and physical illness, poor concentration, reduced energy levels and increased risk of anxiety or depression (3). In recent decades, there has been increased attention to sleep quality and sleep hygiene. Sleep hygiene may be described as behavioral and environmental practices that promote sleep and avoiding behaviors that interfere with sleep (7, 11, 12). In the 2014-revised edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD), inadequate sleep hygiene was classified as a subtype of chronic insomnia. Inadequate sleep hygiene, as stated in the ICSD, is presumed to result from or be sustained by daily living activities that are inconsistent with the maintenance of good-quality sleep and normal daytime alertness (13).

The diagnostic criteria for Inadequate Sleep Hygiene in ICSD are as follows: the patient has persistent insomnia or excessive sleepiness for one month with at least one of the following evidences: i) improper sleep schedule (e.g. frequent daytime napping, highly variable bedtimes or rising times, or spending excessive time in bed; ii) routine use of alcohol, nicotine, or caffeine, especially preceding bedtime; iii) mentally stimulating, physically activating, or emotionally upsetting activities close to bedtimes; iv) frequent use of the bed for non-sleep activities (e.g. television watching, reading, studying, eating, thinking and planning); v) lack of a comfortable sleeping environment (13).

Three instruments designed to assess sleep hygiene are as follows; Sleep Hygiene Awareness and Practice Scale (SHAPS) (14), Sleep Hygiene Self-Test (SHST) (15), and Sleep Hygiene Index (SHI) (11). The first two instruments have been found to have relatively low internal consistency compared to the SHI (Cronbach’s alphas = 0.47 for the SHAPS, 0.54 for the SHST and 0.66 for the SHI). Moreover, SHAPS and SHST appear to have been developed with absence of clear rationale for item selection (11, 16), while the SHI was developed from the diagnostic criteria for inadequate sleep hygiene as described in the ICSD (12, 15). The SHI has shown moderate internal consistency and good two-week test-retest stability (r = 0.71, P < .001), and was associated with sleep quality and daytime sleepiness in a nonclinical sample (11). The SHI had adequate validity and reliability in a sample of patients with chronic pain in Korea (16) and also among clinical and non-clinical Turkish samples (3). However, there is a lack of measurement of reliability and validity of SHI in the Iranian population.

2. Objectives

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of SHI in the Iranian general population.

3. Materials and Methods

This population-based study was conducted in Kermanshah, located in western Iran, between April 2014 and May 2015. All procedures were approved by the institutional ethics committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (KUMS) and written consent and/or assent were obtained from the study participants. Fifty random clusters from different areas of the city were selected according to the statistical information from the Kermanshah health center on the households in this area. From each cluster, 20 - 30 people aged > 20 years were included. If there was more than one individual in a family aged > 20 years, we included all those who were available in our study. The exclusion criteria were having underlying disease (e.g. diabetes and cardiovascular) and having psychiatric or mental disorders. Also, subjects were excluded if they did not speak Persian. For those who did not want to participate, we recruited individuals from the next household. Finally, 1280 subjects were enrolled in this study by cluster random sampling. From 1280 participants, 1242 filled out the questionnaire completely. Thirty-eight datasets were excluded due to skipped items or illegible handwriting.

After a brief explanation about the study goals, the study participants completed the questionnaires. Data were collected from the study participants using SHI, Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI), Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) and insomnia severity index (ISI). A subset of participants (20%) repeated SHI after a four to six-week interval to measure test–retest reliability.

3.1. Translation

A standard forward–backward translation method was used. Two physicians translated the English version of SHI into Persian (Iran’s official language). A fellowship student in sleep medicine compared these translations, and a single version of the translated SHI was obtained. Then, two professional translators who were blinded to the original questionnaire translated it back to English. These translations were assessed by a bilingual physician; only two mistakes were found in the translation, and ultimately, a single English version was finalized. Ten expert physicians in the sleep medicine and psychiatric departments evaluated the content validity. Twenty patients were asked to fill in the questionnaire, and a debriefing interview was performed to assess its face validity.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Sleep Hygiene Index

The SHI is a 13-item self-report index developed by Mastin et al. to assess the presence of sleep hygiene behaviors. Items constructing the Sleep Hygiene Index were derived from the diagnostic criteria for inadequate sleep hygiene in the ICSD. Participants were asked to show how frequently they engaged in specific behaviors (always, frequently, sometimes, rarely and never). Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 [never] to 4 [always]). The total scores ranged from 0 to 52, with higher scores revealing more maladaptive sleep hygiene status. The scale had an internal consistency of Cronbach’s α of 0.66, and good test-retest reliability of 0.71, P < 0.01 (11).

3.2.2. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

The PSQI is a self-report instrument with 28 items that can be used to assess sleep quality over a one-month period in clinical and nonclinical populations. The scores ranged from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. The PSQI has been confirmed to have good internal reliability, stability over time and adequate validity (17). We used an Iranian version of PSQI that has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity (18).

3.2.3. Epworth Sleepiness Scale

The ESS is a self-administered eight-item questionnaire. The total scores range from 0 to 24, with scores greater than 10 suggesting significant daytime sleepiness (19). We used an Iranian version of the ESS, which has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity (20).

3.2.4. Insomnia Severity Index

The ISI is a short, subjective instrument for measuring insomnia symptoms and consequences. This instrument comprises seven items, and each item is rated on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). The total scores ranged from 0 to 28, with higher scores indicating greater severity of insomnia (21, 22). It has been shown that Iranian version of ISI have adequate validity and reliability (23).

3.3. Statistical Analyses

After descriptive statistics, to explore the factor structure of the Persian version of SHI, we performed the varimax-rotated principal components analysis and confirmed the factor solution of the explanatory factor analysis (3). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were computed. Four to six weeks test-retest intra-class correlation coefficients between two repeated applications of the SHI in 20% (N = 248) of the participants were calculated for test-retest reliability. Then, we computed Pearson product–moment correlation coefficients for SHI with PSQI, ESS and ISI to demonstrate the construct validity of SHI. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 16.0) with a significance threshold of P < 0.05.

4. Results

Table 1 shows participants’ details (with a mean age of 31.6.27 ± 8.7 years, 63.3% males). Mean SHI score was 38.6 ± 6.2 with a range of 19 to 48.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants (N = 1242).

| Valuable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 455 (36.63) |

| Male | 787 (63.36) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 675 (54.34) |

| Single | 567 (45.66) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 54 (4.34) |

| Elementary | 110 (8.85) |

| High school | 482 (38.8) |

| College or higher | 596 (47.98) |

4.1. Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha for the SHI was 0.89. Twenty percent of the participants (total of 248, with mean age of 33.9 ± 8.2, 157 males) repeated the SHI after four to six weeks (median 31 days) to measure test–retest reliability. The results revealed an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.89, and SHI was found to have good test-retest reliability (r = 0.89, P < 0.01).

4.2. Validity

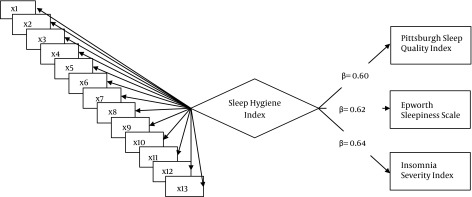

The SHI was positively correlated with all the components of PSQI scores (P < 0.05). Sleep Hygiene Index was positively correlated with the total score of PSQI (P < 0.01), and with ESS (P < 0.01) and ISI (P < 0.01). As shown in Figure 1, partial effects of the variance of latent variables in terms of sleep hygiene were significantly predictive for evaluation of PSQI (B = 0.60, P < 0.01), ESS (B = 0.62, P < 0.01) and ISI (B = 0.64, P < 0.01).

Figure 1. Partial Associations of Latent Variables, Sleep Hygiene, Poor Sleep Quality, Sleepiness and Insomnia.

All partial correlations in the diagram were significant at P < 0.01 level.

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analyses

We performed exploratory factor analyses to assess the construct validity of the Persian version of the SHI. Using computing item statistics, we evaluated the item characteristics from the exploratory factor analyses. All the item discrimination indices in terms of item-total correlation coefficients were greater than 0.02, with the exception of items 1 (“I take daytime naps lasting two or more hours”) and 9 (“I use my bed for things other than sleeping or sex”). Factor loadings for exploratory factor analyses are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Factor Loadings for Explanatory Factor Analysesa.

| Sleep Hygiene Index | Mean | SD | Item Total | φ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 (I take daytime naps lasting two or more hours) | 1.38 | 0.74 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Item 2 (I go to bed at different times each night) | 3.38 | 1.31 | 0.4 | 0.54 |

| Item 3 (I get out of bed at different times from day to day) | 1.94 | 1.27 | 0.35 | 0.48 |

| Item 4 (I exercise to the point of sweating within 1 hour of going to bed) | 1.68 | 1.02 | 0.27 | 0.37 |

| Item 5 (I stay in bed longer than I should two or three times a week) | 2.30 | 1.30 | 0.43 | 0.56 |

| Item 6 (I use alcohol, tobacco, or caffeine within 4 hours of going to bed or after going to bed) | 2.67 | 1.26 | 0.4 | 0.57 |

| Item 7 (I do something that may wake me up before bedtime (for example: play video games, use the internet, or clean) | 3.11 | 1.23 | 0.46 | 0.65 |

| Item 8 (I go to bed feeling stressed, angry, upset, or nervous.) | 3.00 | 1.11 | 0.44 | 0.64 |

| Item 9 (I use my bed for things other than sleeping or sex (for example, watching television, reading, eating, or studying)) | 2.33 | 1.34 | 0.18 | 0.26 |

| Item 10 (I sleep on an uncomfortable bed (for example: poor mattress or pillow, too much or not enough blankets)) | 2.55 | 1.39 | 0.32 | 0.45 |

| Item 11 (I sleep in an uncomfortable bedroom (for example: too bright, too stuffy, too hot, too cold, or too noisy)) | 1.91 | 1.01 | 0.24 | 0.34 |

| Item 12 (I do important work before bedtime (for example: pay bills, schedule, or study)) | 1.78 | 1.37 | 0.29 | 0.44 |

| Item 13 (I think, plan, or worry when I am in bed.) | 2.68 | 1.39 | 0.34 | 0.45 |

aφ = Unrotated item factor loading of explanatory factor analyses.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of the sampling adequacy was 0.89. We calculated a Bartlett’s chi square value of 855.930 (P < 0.01), which indicates appropriateness of the data for the analyses. The exploratory factor analyses of the SHI using the extraction method of principal components indicated that three factors with eigenvalues of > 1 should be retained because they accounted for 67% of the total sample variance (F1 = 44.52%, F2 = 14.69% and F3 = 7.96%). The first factor, namely “sleep-wake cycle behaviors,” was composed of four items 1, 2, 3 and 5; the second factor, namely “bedroom factors,” was composed of three items (8, 9 and 10); and the third factor, namely “behaviors that affect sleep,” was composed of six items (4, 6, 7, 11, 12 and 13), (Table 3).

Table 3. Percentage of Variance and Cumulative Variance, Eigenvalue and Cronbach’s alpha for Each Factor of Sleep Hygiene Index.

| Factors | Cronbach’s Alpha | Percentage Cumulative | Percentageof Variance | Eigenvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 a (Item 1,2,3,5) | /83 | 44/526 | 44/52 | 5/788 |

| 2 b (Item 8,9,10) | /81 | 59/224 | 14/699 | 1/911 |

| 3 c (Item 4,6,7,11,12,13) | /79 | 67/191 | 7/966 | 1/036 |

aFactor 1: Sleep-wake cycle behaviors.

bFactor 2: Bedroom factors.

cFactor 3: Behaviors that affect sleep.

5. Discussion

In this study, we translated the SHI to Persian language and assessed its reliability and validity. In test-retest analyses, we found that 89% of the participants had the same score after a four to six-week interval, which suggests that SHI has good temporal stability in our samples. Mastin et al. assessed the test–retest reliability of SHI, with 141 (55 males and 86 females, mean age of 23.9 years) participants repeating SHI, four to five weeks after the initial test. The authors found that SHI has good test–retest reliability (r = 0.71) (11). Furthermore, in a study of patients with chronic pain, Cho et al. reported higher test–retest reliability of SHI than the study by Mastin et al. (11). Additionally, Ozdemir et al. found acceptable three-week reliability in terms of intra-correlation coefficients (r = 0.62, P < 0.01) in a Turkish community sample (3). Thus, the reliability of SHI in our study and other studies shows that the sleep hygiene behaviors as measured by SHI are stable over time in nonclinical populations.

Both the subscale and total scores of SHI were positively correlated with sleep quality as measured by PSQI, which confirms findings from previous studies that showed sleep hygiene is strongly related to sleep quality (3, 11, 24). Some studies have found that sleep quality is strongly associated with sleep hygiene behaviors (25, 26). As expected, we found that poor sleep hygiene is related to perceptions of increased daytime sleepiness, which is consistent with the findings of other studies (3, 11). Our findings showed a positive correlation between sleep hygiene and insomnia severity as measured by ISI, which is also consistent with prior studies (3, 22). Associations of SHI scores with poor sleep quality, sleepiness and insomnia severity were all predictive of the construct validity of the scale. Our results show that the Persian version of SHI has adequate validity and reliability.

Our item analyses demonstrated that items one and nine had relatively low item reliability and validity. Limited research has been conducted on item analyses for SHI. However, Odzemir et al., has suggested that item four has relatively low item reliability and validity (3). Therefore, these items may need to be revised in future studies. As mentioned in the results, we found three factors with items significantly correlated with each other. These factors were similar to three factors that were extracted by Adan et al. from the Sleep Beliefs Scale (27). Odzemir et al., found that four pairs of items were significantly correlated with each other (3). Item analysis in these studies indicates that much shorter measure of the SHI may be designed with comparable psychometric features relative to this 13-item version.

5.1. Conclusion

The Persian version of SHI is an easy-to-use questionnaire that can be considered as a reliable and valid tool for evaluating sleep hygiene in nonclinical populations. Further research is needed to assess the reliability and validity of the Persian version of SHI in clinical settings.

5.2. Strengths and Limitations

The major strengths of this study are related to its large sample, and cluster random sampling. However, a number of possible limitations of this study should be considered. The major limitation of this study was the use of self-rating scales. Although our results suggest that the Persian version of SHI is a reliable and valid tool for evaluating sleep hygiene, objective evaluations will be necessary for clarifying sleep hygiene in future researches. Although polysomnography is the gold standard for sleep studies (28), actigraphy has become increasingly recognized as a useful method to study sleep/wake patterns and monitoring (29). Using actigraphy for objective evaluation of sleep hygiene is strongly suggested for further researches.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Alireza Kiamanes, Azita Chehri and Hassan Ahadi conceived and designed the evaluation; Azita Chehri and Habibolah Khazaie collected the clinical data; Azita Chehri and Habibolah Khazaie interpreted the clinical data; Azita Chehri, Hassan Ahadi and Habibolah Khazaie performed the statistical analysis; Azita Chehri, Alireza Kiamanesh, Hassan Ahadi and Habibolah Khazaie drafted the manuscript; Azita Chehri, Alireza Kiamanesh and Habibolah Khazaie revised the manuscript according to the reviewers’ comments; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interest:The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding/Support:There was no financial support.

References

- 1.Lee SA, Paek JH, Han SH. Sleep hygiene and its association with daytime sleepiness, depressive symptoms, and quality of life in patients with mild obstructive sleep apnea. J Neurol Sci. 2015;359(1-2):445–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Storfer-Isser A, Lebourgeois MK, Harsh J, Tompsett CJ, Redline S. Psychometric properties of the Adolescent Sleep Hygiene Scale. J Sleep Res. 2013;22(6):707–16. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ozdemir PG, Boysan M, Selvi Y, Yildirim A, Yilmaz E. Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the Sleep Hygiene Index in clinical and non-clinical samples. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;59:135–40. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carskadon MA. Sleep in adolescents: the perfect storm. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2011;58(3):637–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeBourgeois MK, Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Wolfson AR, Harsh J. The relationship between reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in Italian and American adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1 Suppl):257–65. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0815H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carskadon MA. Factors influencing sleep patterns of adolescents. In: Carskadon MA, editor. Adolescent sleep patterns: Biological, social and psychological influences. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 4–26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Sleep Foundation . Technology use and sleep. Virginia: National Sleep Foundation; 2011. [cited 6 Apr 2012]. Available from: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/article/sleep-america-polls/2011-communications-technology-use-and-sleep. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagenauer MH, Perryman JI, Lee TM, Carskadon MA. Adolescent changes in the homeostatic and circadian regulation of sleep. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31(4):276–84. doi: 10.1159/000216538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen IG. Impact of insomnia on future functioning of adolescents. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(1):561–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Russo PM, Bruni O, Lucidi F, Ferri R, Violani C. Sleep habits and circadian preference in Italian children and adolescents. J Sleep Res. 2007;16(2):163–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mastin DF, Bryson J, Corwyn R. Assessment of sleep hygiene using the Sleep Hygiene Index. J Behav Med. 2006;29(3):223–7. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khazaie H, Chehri A, Sadeghi K, Heydarpour F, Soleimani A, Rezaei Z. Sleep Hygiene Pattern and Behaviors and Related Factors among General Population in West Of Iran. Glob J Health Sci. 2016;8(8):53434. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n8p114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Sleep Medicine . International classification of sleep disorders: Diagnostic and coding manual. 3 ed. Westchester, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacks P, Rotert M. Knowledge and practice of sleep hygiene techniques in insomniacs and good sleepers. Behav Res Ther. 1986;24(3):365–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blake DD, Gomez MH. A scale for assessing sleep hygiene: preliminary data. Psychol Rep. 1998;83(3 Pt 2):1175–8. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.83.3f.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho S, Kim GS, Lee JH. Psychometric evaluation of the sleep hygiene index: a sample of patients with chronic pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:213. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrahi Moghaddam J, Nakhaee N, Sheibani V, Garrusi B, Amirkafi A. Reliability and validity of the Persian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-P). Sleep Breath. 2012;16(1):79–82. doi: 10.1007/s11325-010-0478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sadeghniiat Haghighi K, Montazeri A, Khajeh Mehrizi A, Aminian O, Rahimi Golkhandan A, Saraei M, et al. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale: translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Sleep Breath. 2013;17(1):419–26. doi: 10.1007/s11325-012-0646-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gellis LA, Park A, Stotsky MT, Taylor DJ. Associations between sleep hygiene and insomnia severity in college students: cross-sectional and prospective analyses. Behav Ther. 2014;45(6):806–16. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yazdi Z, Sadeghniiat-Haghighi K, Zohal MA, Elmizadeh K. Validity and reliability of the Iranian version of the insomnia severity index. Malays J Med Sci. 2012;19(4):31–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown FC, Buboltz WCJ, Soper B. Relationship of sleep hygiene awareness, sleep hygiene practices, and sleep quality in university students. Behav Med. 2002;28(1):33–8. doi: 10.1080/08964280209596396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jefferson CD, Drake CL, Scofield HM, Myers E, McClure T, Roehrs T, et al. Sleep hygiene practices in a population-based sample of insomniacs. Sleep. 2005;28(5):611–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith S, Trinder J. Detecting insomnia: comparison of four self-report measures of sleep in a young adult population. J Sleep Res. 2001;10(3):229–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2001.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adan A, Fabbri M, Natale V, Prat G. Sleep Beliefs Scale (SBS) and circadian typology. J Sleep Res. 2006;15(2):125–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tahmasian M, Khazaie H, Golshani S, Avis KT. Clinical application of actigraphy in psychotic disorders: a systematic review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(6):359. doi: 10.1007/s11920-013-0359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tahmasian M, Khazaie H, Sepehry AA, Russo MB. Ambulatory monitoring of sleep disorders. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60(6):480–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]