Abstract

To contain autoimmunity, pathogenic T cells must be eliminated or diverted from reaching the target organ. Recently, we defined a novel form of T cell tolerance whereby treatment with antigen (Ag) downregulates expression of the chemokine receptor, CXCR3 and prevents diabetogenic Th1 cells from reaching the pancreas leading to suppression of Type 1 diabetes (T1D). This report defines the signaling events underlying Ag-induced chemokine receptor-mediated tolerance. Specifically, we show that the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) is a major target for induction of CXCR3 down-regulation and crippling of Th1 cells. Indeed, Ag administration induces up-regulation of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on dendritic cells (DCs) in a T cell-dependent manner. In return, PD-L1 interacts with the constitutively expressed PD-1 on the target T cells and stimulates docking of SHP-2 phosphatase to the cytoplasmic tail of programmed death-1 (PD-1). Active SHP-2 impairs the signaling function of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) pathway leading to functional defect of mTORC1, down regulation of CXCR3 expression and suppression of T1D. Thus, mTORC1 component of the metabolic pathway serves as a target for chemokine receptor-mediated T cell tolerance and suppression of T1D.

Introduction

Ag-driven T cell tolerance offers an attractive approach to contain T1D (1–4). Expansion of T regulatory cells (Tregs) (1, 4, 5), interference with the expression/function of costimulation activating molecules (6) and triggering of costimulation inhibiting ligands (7) represent the major basic cellular mechanisms by which Ag can restrain pathogenic T cells. The signaling pathways that bring about these events remain, however, largely undefined. Over the years, we employed genetic engineering to express self-peptides on Ig molecules (8) and used the resulting Ig-self-peptide chimeras to augment Ag-specific tolerance against experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (9, 10). The effectiveness of this Ag-delivery system proved broad and Ig chimeras carrying diabetogenic T cell epitopes were also able to shift pathogenicity into T cell tolerance against T1D both at early (5, 11, 12) and late stages of the disease (1, 2). More recently, the peptide library-derived p79 T cell epitope (13) which is reactive with the highly diabetogenic BDC2.5 TCR transgenic T cells (14) was expressed on an Ig molecule and the resulting Ig-p79 chimera was able to modulate BDC2.5 Th1-driven T1D (15). Fine analysis of the cellular mechanism underlying Ig-p79-driven Th1 tolerance pointed to downregulation of both the transcription factor T-bet and the chemokine receptor CXCR3 which led to retention of the Th1 cells in the spleen instead of migration to the pancreas resulting in suppression of T1D (15). While these findings highlight a new T cell trafficking form of tolerance, the signaling events that underlie CXCR3 downregulation and the consequent T cell crippling have not been defined. In this report we used the Ig-p79 delivery system and the BDC2.5 Th1 cell transfer model of T1D and examined the signaling events that translate Ag treatment into cell-trafficking T cell tolerance. The findings indicate that the process begins with a T cell-dependent up-regulation of PD-L1 on the APCs presenting Ig-p79. Subsequently, interaction of PD-L1 with PD-1 on T cells specifically leads to down-regulation of mTORC1 function through an SHP-2-phosphatase-mediated dephosphorylation of the AKTT308 kinase. These previously unrecognized findings highlight the role mTORC1 plays in this new form of Ag-induced chemokine receptor-mediated T cell tolerance and suppression of T1D.

Materials and Methods

Mice

NOD (H-2g7), NOD.scid, NOD.BDC2.5 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). NOD.BDC2.5.GFP was generated by breeding BDC2.5 mice to NOD mice expressing GFP under the β-actin promoter (16). All mice were used at the age of 6–8 weeks according to the guidelines of the University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee.

Peptides and Ig chimeras

The p79 peptide corresponds to a library defined mimotope (AVRPLWVRME) and HEL peptide corresponds to aa residues 11–25 of HEL were previously described (15). Ig-p79 expressing p79 mimotope and Ig-HEL incorporating HEL peptide within the heavy chain variable region have been previously described (15). Large cell culture production and affinity chromatography purification of Ig-p79 and Ig-HEL were accomplished as described (15).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: mTOR mAb (7C10), phospho-S6 (Ser235/236) (D57.2.2E)-APC, phospho-p70 S6 kinase (Thr389) (108D2) mAb, phosphor-AKT (Thr308) (C31E5E) mAb, phospho-Akt (Ser473) (D9E) mAb, GFP (D5.1) mAb, SHP-2 (D50F2) mAb (Cell Signaling Technology); APC-conjugated Donkey-anti-Rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch); CD3e (145-2C11)-FITC, CD4 (RM4-5)-PE-Cy7, Vβ4 (KT4)-PE, CD11c-APC, CD11b-PE-Cy7, B220-FITC, CD19-PE-Cy7 and PD-L1-PE (BD Biosciences); F4/80-PE and PD-1-PE-Cy7 (BioLegend); CD71-APC and CD98-PE, CD90.1 (Thy-1.1)-PE, CXCR3-APC, CD80-PE, CD86-PE and PD-L2-PE (eBioscience); PD-1 (J43) Ab (Novus); T-bet-FITC and SH-PTP2 (C-18) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

T cell polarization

Splenic cells from 4 to 6 week-old naïve NOD.BDC2.5 mice were polarized to Th1 cells as follows: The cells (2 x 106 cells/mL) were stimulated with p79 peptide (0.5μM) for 4 days in the presence of recombinant (r)IL-12 (10 ng/mL; PeproTech) and anti-IL-4 antibody (10 μg/mL).

Induction of T1D by adoptive transfer of polarized Th1 cells

Polarized CD4+ Th1 cells were purified by negative selection using CD4 T-cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec) and stimulated with phorbol myristic acid (PMA; 50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (500 ng/mL) for 2 h. The cells were then labeled using the mouse IFN-γ (allophycocyanin) detection kit from Miltenyi Biotec. Subsequently, the enriched Th1 cells (IFN-γ+) cells were sorted to at least to 98% purity on a Beckman Coulter MoFlo XDP sorter and transferred intravenously into NOD.scid (6 X 106 cells per mouse). Mice were monitored for T1D by measuring blood glucose level (BGL) daily. A mouse is considered diabetic when BGL is ≥ 300 mg/dL on two consecutive measurements.

Flow cytometry

For staining of surface antigens, cells (1x 107 cells per well) were incubated with mouse IgG (Sigma) to block FcγRs and stained with saturating concentrations of fluorochrome-labeled antibody in PBS containing 0.5% BSA. Dead cells were excluded using 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD) (EMD Biosciences). For intracellular staining, cells were stained for surface markers, treated with Fix/Perm buffer (eBioscience) and then incubated with conjugated antibody for intracellular staining, dead cells were excluded using fixable viability dye (eBioscience). Data were acquired on Beckman Coulter Cyan (Brea, CA) and analyzed using Flowjo 10.0.8 (Tree Star) or Summit software V5.2 (Dako).

Western Blot

Equal amounts of cell lysate proteins from sorted T cells were resolved on 12% SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto PVDF membranes using standard procedures. Primary antibodies were as follows: mTOR mAb (7C10), phospho-p70 S6 kinase (Thr389) (108D2) mAb, phospho-AKT (Ser473) (D9E) mAb, and GFP (D5.1) mAb (Cell Signaling Technology). The secondary antibody was HRP-conjugated Donkey-anti-Rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Data were imaged by Odyssey Fc (Li-Cor) and protein bands were analyzed by densitometry using Image Studio V3.1 (Li-Cor).

Immunoprecipitation

T cell lysates were pre-incubated with protein G-sepharose 4B (Invitrogen) for 30 mins at 4°C to clear non-specific binding. The supernatants were then incubated with anti-PD-1 mAb (Novus) or anti-SHP-2 mAb (Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C and protein G-sepharose 4B were added and incubation was continued for 3 hours. Antigen-antibody complexes were pulled down by centrifugation and suspended in 2 X Laemmli buffer. The samples were boiled, resolved on SDS-PAGE, transferred onto PVDF membranes and blotted with anti-SHP-2 mAb (Cell Signaling Technology).

Retroviral Transduction

DNA from naïve BDC2.5 T cells was used to amplify the CD3 promoter fragment (-401/+52 bp) by PCR using 5′-GTATTTGTACATGATCAGAAACAAGAG-3′ and 5′-GTATTAGATCTTGATCAGCCAGGGTTA-3′ primers. The amplified fragment was then cloned into the BsrGI and BglII restriction sites of the MSCV-IRES-Thy1.1 vector (15) and the sequence was confirmed by automated sequencing. MSCV-CD3p-IRES-Thy1.1 was used to insert mTOR gene (from pcDNA3-Flag mTOR, addgene) into NotI site and generated an MSCV-CD3p-mTOR-IRES-Thy1.1 carrying both Thy1.1 and mTOR under CD3 promoter.

In contrast, DNA from activated BDC2.5 Th1 cells was used to amplify the Akt1 gene by PCR with the following primers: 5′-CTATTGCGGCCGCGCCACCATGAAC and 5′-GTATTGTCGACTCAGGCTGTGCCACT. The amplified gene was then cloned into MSCV-CD3p-IRES-Thy1.1, as an EcoRI/BglII fragment. The DNA sequence of the resulting MSCV-CD3p-AKT-IRES-Thy1.1 vector, was verified by automated sequencing.

The vectors were transfected into 293FT cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and the culture supernatant containing the packaged retroviruses was used to transduce polarized Thy1.2 BDC2.5 Th1 cells. Transduced T cells were sorted on the basis of Thy1.1 expression and used for transfer experiment.

Quantitative PCR analysis

The total RNA of splenic Th1 cells was extracted using the TRI RNA isolation reagent (Sigma). Quantitative PCR with specific primers was performed using the Power SYBR Green kit and the StepOnePlus instrument (all from Applied Biosystems). The primers are as follows:

mTOR:

forward, 5′CTAGACTTCACTGACTACGC3′, reverse, 5′GAAGATCTGGTACTTCTTCC3′

GAPDH

forward, 5′AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG3′, reverse, 5′GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT3′

Measurement of cytokines by ELISA

Detection of IFN-γ was conducted by ELISA according to BD Pharmingen’s standard protocol. The capture antibody was rat-anti-mouse IFN-γ (R4-6A2) and the biotinylated detection antibody was rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (XMG1.2). The OD450 was read on a SpectraMax 190 counter (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and analyzed using SOFTmax PRO 5.4 software. Graded amounts of recombinant IFN-γ (PeproTech) were included for construction of standard curve. Cytokine concentration were extrapolated from the linear portion of the standard curve.

PD-L1 blockade

To inhibit PD-L1 interaction with PD-1 DC culture was supplemented with 20 mg/mL anti-PD-L1 (10F.9G2) (BioXcell) and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. The DCs were then washed twice with PBS and used for in vitro experiments. For blockade of PD-L1 in vivo the mice recipient of polarized BDC2.5 Th1 cells were given anti-PD-L1 antibody (200 μg/mouse) intraperitoneally on day 1, 3, 5, and 7 post T cell transfer.

SHP-2 inhibition

Naïve BDC2.5 CD4+CD25− T cells were cultured with p79-loaded splenic DCs in the presence of 50 μM NSC-87877 inhibitor (Tocris bioscience) for 72 hours.

Statistical analysis

p values were calculated using the unpaired two-tailed Student t test. ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-test was used to compare more than 2 groups. Prism Software v4.0c (Graphpad) was used in all statistical analyses. Data significance is denoted by one asterisk for p<0.05 two asterisks for p<0.01 and three asterisks for p<0.001.

Online Supplemental Material

Fig. S1 shows interference with trafficking of diabetogenic BDC2.5 Th1 cells and suppression of T1D by treatment with Ig-p79. Fig. S2 shows acceleration of the development of T1D upon overexpression of mTOR in pathogenic Th1 cells. Fig. S3 shows progressive decline of pAKTT308 in Th1 cells undergoing Ag-specific tolerance. Fig. S4 shows increased phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein and acceleration of T1D upon overexpression of AKT in pathogenic Th1 cells.

Results

Antigen-driven T cell tolerance targets mTOR complex 1 activation

As has been shown previously (15), non-obese diabetic (NOD).scid mice recipient of diabetogenic Th1 cells resist the development of T1D when treated with Ig-p79 tolerogen, an Ig molecule carrying p79 mimotope (15), but not the control Ig-HEL, an Ig incorporating hen egg lysozyme (HEL) peptide (15) (Fig. S1A). This likely reflects inability of the Th1 cells to traffic from the spleen to the pancreas (Fig. S1B) due to down-regulation of the transcription factor T-bet and the consequent loss of CXCR3 expression (Fig. S1C). In fact, the cell retained in the spleen which display diminished CXCR3 expression, are able to proliferate but not transfer disease indicating that tolerance in this case is due to interference with trafficking(15). Since expression of CXCR3 is controlled by T-bet and mTOR controls T cell programing by regulating the expression of T-bet, among other transcription factors (17–19), we sought to determine whether Ag-driven T cell tolerance targets mTOR to alter T-bet expression and affects the function of effector T cells. To test this premise, expression of mTOR and the activity of its complexes were analyzed in Th1 cells undergoing tolerance. Accordingly, Th1-polarized BDC2.5 cells were transferred into NOD.scid mice and the hosts were treated with Ig-p79 or the control Ig-HEL. One week later, the splenic and pancreatic T cells were harvested and assessed for mTOR expression and function. The results show that the level of mTOR protein was significantly reduced in the T cells from Ig-p79 treated mice relative to those originating from Ig-HEL recipient animals (Fig. 1A and 1B). Similarly, when the Th1 cells were derived from NOD.BDC2.5.GFP mice (expressing GFP under β-actin promoter), and the analysis was performed by Western blot, mTOR expression was again significantly reduced with Ig-p79 treatment relative to Ig-HEL (Fig. 1C). The decrease in total mTOR protein was not observed on day 1 or 4 post treatment as the MFI levels of mTOR expression in splenic Th1 cells were 33 and 56 for Ig-HEL compared to 30 and 60 for Ig-p79, respectively. Furthermore, mRNA quantification at days 1, 4, and 7 post treatment showed similar mTOR mRNA levels in splenic Th1cells from Ig-p79 and Ig-HEL treated mice as the ΔCT (relative to GAPDH housekeeping gene) was 6.82 on day 1; 8.99 on day 4; and 8.98 on day 7 for Ig-p79, and 6.82 on day 1; 8.95 on day 4; and 8.97 on day 7 for Ig-HEL. Thus the decrease in mTOR expression is at the protein rather than mRNA level and is prominent on day 7 posttreatment with Ig-p79.

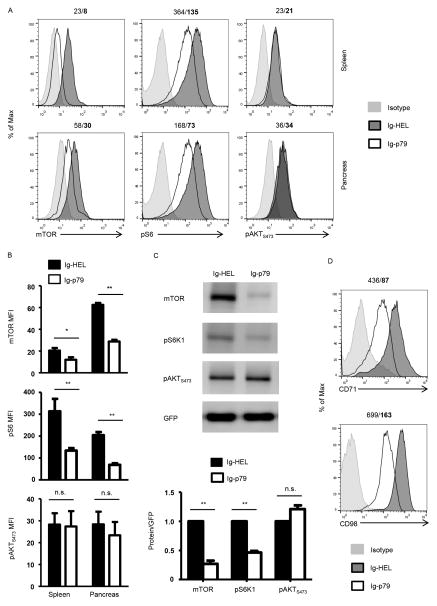

Figure 1. Th1 cells display impaired mTORC1 function upon induction of tolerance.

(A) Th1 polarized BDC2.5 T cells were transferred (6 x 106 cells per mouse) into NOD.scid mice (n = 6 mice per group) and 6 hours later the hosts were treated with 300 μg Ig-p79 or Ig-HEL. After one week, the CD4+Vβ+ SP and PN T cells were analyzed for expression of mTOR protein, and phosphorylation of S6 and AKT (Ser473) by flow cytometry. The histograms show a representative experiment for treatment with Ig-p79 or the control Ig-HEL. Staining for the indicated molecules is shown in comparison to isotype control. The numbers on top of the histograms indicate the MFI for Ig-HEL and Ig-p79 (bold), respectively. (B) Shows compiled results from 5 experiments including the representative one illustrated in (A). Each bar represents the mean MFI ± SEM. (C) Polarized Th1 cells from NOD.BDC2.5.GFP were transferred into NOD.scid mice and the hosts were treated with Ig-p79 or Ig-HEL mice (n = 18 mice per group). On day 7 after treatment BDC.2.5 T cells were sorted from the spleen on the basis of GFP expression. The top panel shows mTOR expression and phosphorylation of S6K1 and pAKTS473 as analyzed by Western blot. GFP was used as loading control. The bottom panel shows the relative expression of mTOR, phos-S6 and phos-AKT (Ser473) normalized to the expression of GFP as analyzed by densitometry of the Western blots from 3 different experiments. (D) Shows expression of CD71 and CD98 molecules on splenic T cells from panel (A). The results are representative of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n.s. not significant.

mTOR undertakes signaling function in the form of two different complexes referred to as mTORC1 and mTORC2 (20). We then sought to determine whether reduction in mTOR expression results in a decrease in the function of its complexes. The activity of mTORC1 can be measured by phosphorylation of either S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) or its substrate, the ribosomal S6 protein (S6), while phosphorylation of AKTS473 serves as a readout for mTORC2 function. As indicated in Figure 1, Th1 cells undergoing Ig-p79-mediated tolerance had significantly reduced mTORC1 activity relative to Ig-HEL treatment while the activity of mTORC2 is intact whether the T cells were subjected to Ig-p79 or Ig-HEL treatment. Indeed, in the spleen, pS6 level went down from 364 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) under Ig-HEL treatment to 135 MFI with Ig-p79 while pAKTS473 levels were comparable in both treatments (Fig. 1A). A similar decrease in pS6 was also observed in pancreatic T cells from mice treated with Ig-p79 relative to Ig-HEL (73 versus 168 MFI). No decrease in pAKTS473 was observed in pancreatic T cells with either treatment. Compiled results from several experiments confirm that the decrease in pS6 MFI observed in both splenic and pancreatic T cells upon treatment with Ig-p79 is statistically significant relative to T cells from mice recipient of the control Ig-HEL treatment (Fig. 1B). In contrast, no significant differences were observed in the phosphorylation of pAKTS473 (Fig. 1B). Western blot analysis using Th1 cells derived from NOD.BDC2.5.GFP again demonstrate the Ig-p79 treatment targets mTORC1 not mTORC2 (Fig. 1C). Indeed, phosphorylation of pS6K1 was decreased in a significant manner upon treatment with Ig-p79 relative to Ig-HEL. However, no significant decrease was observed in the phosphorylation of pAKTS473 (Fig. 1C). The targeting of mTORC1 by Ig-p79 is further confirmed by the downregulation of the expression of metabolic proteins that are under the control of mTORC1 (Fig. 1D). This conclusion is drawn from the observation that CD71, a transferrin receptor, and CD98, a subunit of L-amino acid transporter, which are controlled by mTORC1 (21, 22) are also affected by treatment with Ig-p79 but not Ig-HEL. It should be noted that mTORC2 activity was not significantly affected, perhaps due to the fact that under physiologic conditions mTORC1 keeps mTORC2 activity in check (23). Logically, under Ig-p79 treatment mTORC2 activity should be increased. However, the decrease in total mTOR offset this effect leading only to a slight increase in mTORC2 activity (Fig. 1C). Overall, antigen-specific tolerance of Th1 cells targets mTORC1 but not mTORC2.

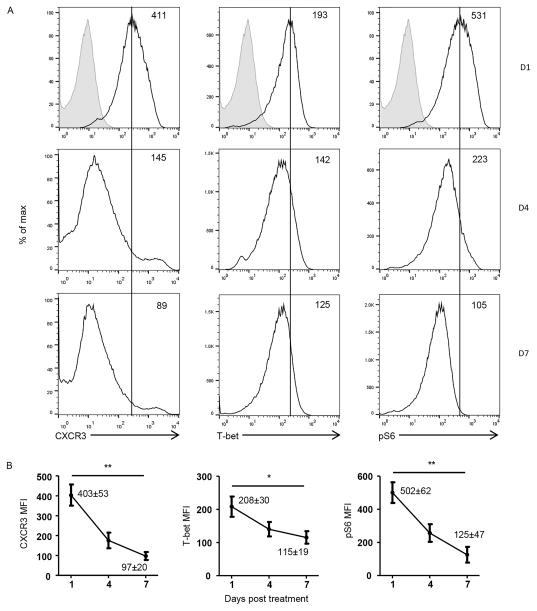

Th1 cells undergoing mTORC1-mediated tolerance display diminished expression of the transcription factor T-bet and the chemokine receptor CXCR3

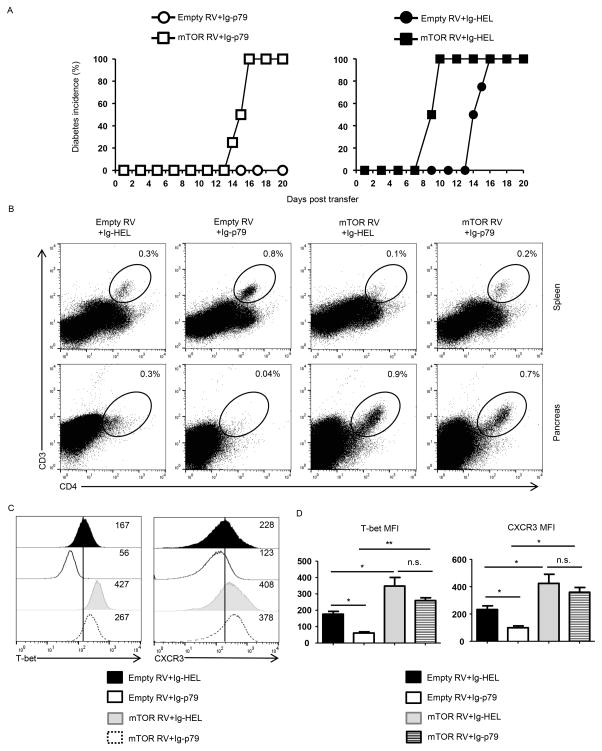

Th1 cells exposed to Ig-p79 in vivo downregulate both T-bet and CXCR3 expression leading to retention of the cell in the spleen with minimal migration to the pancreas (Fig. S1). Figure 2 shows that downregulation of T-bet and CXCR3 proceeds gradually after treatment with Ig-p79 and parallels with diminished phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein. Indeed, this parallel dynamic begins on day 1 after Ig-p79 treatment to reach minimal levels on day 7 (Fig. 2A), a point at which usually the disease begins to manifest. The decrease in CXCR3 MFI went down from 403 ± 53 on day 1 to 97 ± 20 on day 7 while T-bet decreased from 208 ± 30 to 115 ± 19 from day 1 to day 7 (Fig. 2B). The down-regulation for both molecules is statistically significant. Similarly, a significant gradual decrease was observed in the same Th1 cells for the phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein (compare 502 ± 62 to 125 ± 47) indicating a regulatory relationship between mTORC1 and T-bet/CXCR3 molecules. If this regulatory network was to be true then overexpression of mTOR would counter down-regulation of T-bet/CXCR3 expression and the Th1 cell would resist Ig-p79-mediated tolerance. To test this premise, we began by transducing the Th1 cells with mTOR retroviral vector and assayed for hyper phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein and exacerbation of T1D. Figure S2 shows that mouse stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviral vector (RV) engineered to co-express mTOR and the congenic marker Thy1.1 (mTOR RV) transduces Th1 cells like the empty vector (empty RV) carrying Thy1.1 gene without mTOR (Fig. S2). When the transduced Th1 cells were examined for mTORC1 activity, S6 phosphorylation was significantly increased relative to empty RV indicating that mTOR overexpression is functional (Fig. S2B). Furthermore, the transduced Th1 cells accelerated T1D manifestation when transferred into NOD.scid mice further confirming that mTORC1 activity is involved in T1D and transduction increases the activity of the complex (Fig. S2C). Since overexpression of mTOR increases the activity of complex 1, one would envision that the Th1 cells will resist Ig-p79-induced tolerance. This was indeed the case as mice recipient of Th1 cells transduced with mTOR RV resist Ig-p79 tolerance and develop T1D while those recipient of empty RV-transduced Th1 cells remain susceptible to Ig-p79 tolerance and do not develop T1D (Fig. 3A). The nullification of Ig-p79 tolerance by mTOR-RV is comparable to that driven by CXCR3-RV (15). Control mice treated with Ig-HEL also develop T1D whether the Th1 cells are transduced with mTOR or empty RV indicating that tolerance or the lack thereof, is Ag-specific (Fig. 3A). The resistance to Ig-p79 tolerance by Th1 cells overexpressing mTOR is reflected in their trafficking behavior as they are no longer retained in the spleen (compare 0.2% to 0.8%) but migrate efficiently to the pancreas (compare 0.7% to 0.04%) relative to T cells transduced with empty RV (Fig. 3B). This is comparable to overexpression of CXCR3 by transduction with CXCR3-RV (15). The Th1 cells whether transduced with mTOR RV or empty RV were not retained in the spleen but migrated to the pancreas when the treatment used Ig-HEL control (Fig. 3B), again indicating that overexpression interferes with tolerance in an Ag-specific manner. The loss of Ig-p79 ability to suppress migration of mTOR-overexpressing Th1 cells to the pancreas and the consequent disease manifestation correlate with the fact that Ig-p79 no longer induces downregulation of T-bet and CXCR3 efficiently (Fig. 3C). In fact, Ig-p79 treatment was able to down-regulate T-bet or CXCR3 expression slightly (compare 267 MFI to 427 MFI) (Fig. 3C) but data compiled from three independent experiments indicate that such down-regulation is not statistically significant (Fig. 3D). In contrast, Ig-p79 treatment was able to down-regulate T-bet and CXCR3 expression in a significant manner relative to Ig-HEL in Th1 cells transduced with empty RV (Fig. 3C and D). These results indicate that Ig-p79 is no longer able to induce down-regulation of T-bet and CXCR3, retain the cells in the spleen, or modulate the disease when the Th1 cells are overexpressing mTOR.

Figure 2. Progressive decline in mTORC1 signaling correlates with downregulation of T-bet and CXCR3 expression.

Polarized BDC2.5 T cells were transferred (6 x 106 cells per mouse) into NOD.scid mice (n = 4 mice per group) and 6 hours later the hosts were treated with 300 μg Ig-p79. On day 1, 4, and 7 after transfer, the CD4+Vβ+ SP T cells were analyzed for expression of surface CXCR3, intracellular T-bet as well as phosphorylation of S6 by flow cytometry. (A) Shows results from 1 representative experiment with shaded histograms representing staining with isotype control while the open histograms represent staining with specific antibodies. The number in the upper right corner indicates the MFI for the test molecules. (B) Shows MFI ± SEM from 3 independent experiments for day 1, 4, and 7 post treatment with Ig-p79. The number listed for day1 and day 7 represent the exact value of MFI ± SEM for comparison purpose. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01,

Figure 3. Overexpression of mTOR in pathogenic Th1 cells nullifies Ag-induced tolerance.

Th1 BDC2.5 cells transduced with mTOR RV or empty RV were transferred (1x 106 cells per mouse) into NOD.scid mice (n = 4 per group) and the hosts were treated with a defined Ig-p79 tolerogenic regimen. (A) Shows disease incidence in Ig-p79 (left panel) and Ig-HEL control (right panel) treated mice. (B) Shows the frequency of residual T cells in spleen and pancreas on day 21 after transfer. (C) Shows T-bet and CXCR3 expression by splenic T cells on day 21 after cell transfer. Results in (A–C) are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Shows MFI of CXCR3 and T-bet expression by splenic T cells of (C). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, as determined by ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-test.

Overall, Ag-induced tolerance of Th1 cells targets mTORC1 leading to down-regulation of T-bet and CXCR3 expression, retention of the cells in the spleen and resistance to T1D.

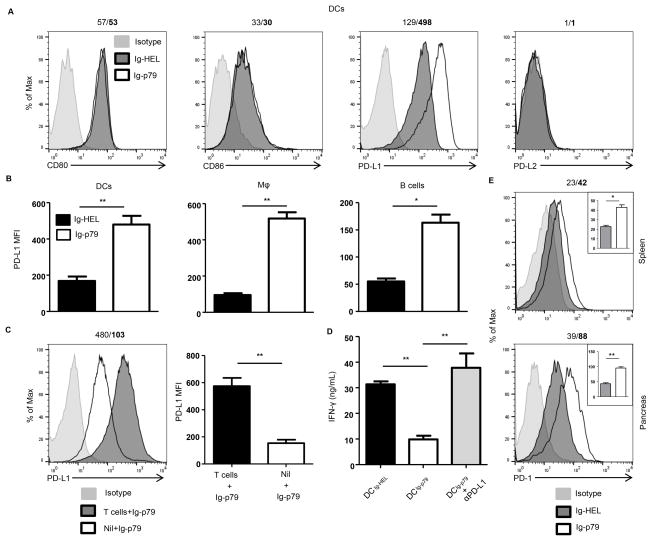

APCs up-regulate PD-L1 upon interaction with T cells undergoing mTOR-mediated Ag-specific tolerance

T cells must recognize their cognate Ag presented by competent APCs expressing optimal costimulatory molecules in order to undergo activation (24). In contrast, when the Ag is delivered to APCs under non-inflammatory conditions that drive presentation with minimal costimulation, tolerance rather than activation ensues (9, 10). The costimulatory network is diverse and includes molecules on the surface of APCs and their ligands on T cells (25–27). To determine which of these costimulatory molecules on APCs target mTORC1 to drive T cell tolerance, we assessed the APCs for alteration in the expression of inhibitory (PD-L1 and PD-L2) as well as stimulatory (CD80, CD86) molecules. The findings indicate that only PD-L1 expression is up-regulated upon treatment with Ig-p79 relative to the control Ig-HEL (Fig. 4A). This was not restricted to DCs as other APCs such as macrophages and B cells also up-regulate PD-L1 in a significant manner relative to treatment with Ig-HEL (Fig. 4B). In addition, up-regulation of PD-L1 on APCs requires interaction with T cells as DCs from NOD.scid mice that were not given T cell transfer before treatment with Ig-p79 could not significantly up-regulate PD-L1 relative to DCs from mice given both T cell transfer and Ig-p79 treatment (Fig. 4C). The results also indicate that these interactions are Ag-specific because Ig-HEL could not induce PD-L1 up-regulation (Fig. 4A). The PD-L1-high (PD-L1hi) DCs from Ig-p79 treatment (DCIg-p79) display suppressive function as co-culture with naïve BDC2.5 T cells in the presence of p79 peptide could not induce IFN-γ production by the T cells (Fig. 4D). This suppression is dependent on PD-L1 as DC derived from Ig-HEL treatment (DCIg-HEL) which do not up-regulate PD-L1 could not drive suppression of BDC2.5 T cells (Fig. 4D). Similarly blockade of PD-L1 with anti-PD-L1 antibody during co-culture of naïve BDC2.5 T cells with p79-loaded DCIg-p79 could not drive suppression of IFN-γ production. Together, these findings indicate that up-regulation of PD-L1 on APCs requires interaction with T cells. In addition, the PD-L1hi DCs were able to inhibit activation of BDC2.5 T cells. Since PD-L1 usually carries out its inhibitory function through interaction with PD-1 (28), we sought to determine whether T cell undergoing Ig-p79-induced tolerance up-regulate PD-1 expression. This was indeed the case as both splenic and pancreatic BDC2.5 T cells significantly up-regulated PD-1 expression upon treatment with Ig-p79 relative to the control Ig-HEL (Fig. 4E). Moreover, administration of anti-PD-L1 antibody during treatment with Ig-p79 nullified suppression of T1D (Fig. 5A) and the T cells were able to reach the pancreas as their percentage increased from 0.2% during treatment with Ig-p79 alone to 2% when Ig-p79 was accompanied with anti-PD-L1 antibody (Fig. 5B). The return of the T cells to the pancreas during treatment with Ig-p79 and anti-PD-L1 antibody was significant when the percentage and absolute T cell number was compared to treatment with Ig-p79 alone (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, blockade of PD-L1 restores S6 phosphorylation and expression of T-bet and CXCR3 in both splenic and pancreatic T cells in the mice treated with Ig-p79 accompanied with anti-PD-L1 antibody but not in animals given Ig-p79 alone (Fig. 5D).

Figure 4. Ig-p79 induced mTOR-mediated T cell tolerance correlates with PD-L1 upregulation on splenic APCs.

(A, B) BDC2.5 Th1 cells were transferred into NOD.scid mice and the hosts were treated with Ig-p79 or Ig-HEL. (A) Shows expression of CD80, CD86, PD-L1 and PD-L2 on splenic CD3−F4/80−CD11c+ DCs 1 day after Ig chimera treatment. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Shows MFI of PD-L1 on splenic DCs, macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+) and B cells (CD19+B220+) from 3 independent experiments performed as described in (A). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of 3 experiments. (C) NOD.scid mice (Nil + Ig-p79) and NOD.scid mice recipient of BDC2.5 Th1 cells (T cells + Ig-p79) were treated with Ig-p79 and one day later PD-L1 expression was examined on CD3−F4/80−CD11c+ splenic DCs. The bar graph shows the mean ± SEM MFI from 4 independent experiments. (D) Splenic DCs from Ig-p79 (DCIg-p79) or Ig-HEL (DCIg-HEL) treated NOD.scid mice recipient of BDC2.5 Th1 cells, were sorted on the basis of CD11c expression with exclusion of CD3+ cells. The DCIg-p79 and DCIg-HEL cells were loaded with free p79 peptide and cultured with naïve BDC2.5 CD4+CD25− T cells for 72 hours. IFN-γ production was measured by ELISA. A group of p79-loaded DCIg-p79 coated with anti-PD-L1 antibody was included for control purposes. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. **p < 0.01. (E) NOD.scid mice recipient of BDC2.5 Th1 cells were treated with Ig-p79 or Ig-HEL and 7 days later the expression of PD-1 by splenic (upper panel) and pancreatic (lower panel) T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry. Results are representative of three independent experiments. The numbers on top of the panels represent the MFI obtained upon treatment with Ig-HEL/Ig-p79, respectively. The insets represent the mean ± SEM of MFI collected from 3 independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

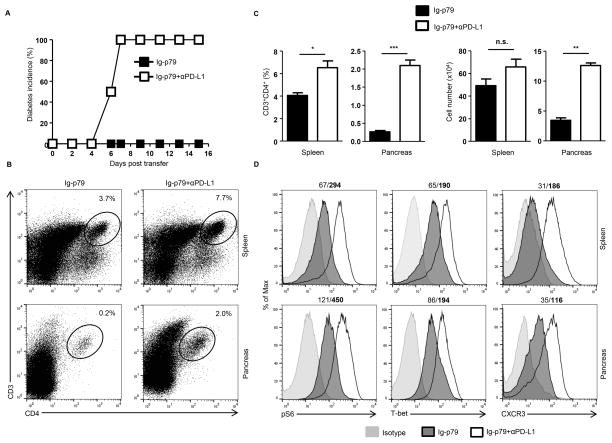

Figure 5. Blockade of PD-L1 restores mTORC1 activity and nullifies Ig-p79-induced tolerance.

NOD.scid mice (6 per group) were given BDC2.5 Th1 cells and treated with Ig-p79 alone or together with anti-PD-L1 antibody (200 μg/mouse, i.p.). Another injection of anti-PD-L1 antibody was give on day 3 and 5 after Ig-p79 treatment. (A) Shows diabetes incidence up to day 16 after BDC2.5 transfer (n = 6 per group). (B) Shows a representative plot of CD3+CD4+ T cells in spleens and pancreas on day 16 post BDC2.5 Th1 cell transfer. (C) Shows the mean ± SEM of the percentage (left panel) and absolute numbers (right panel) of CD3+CD4+ T cells compiled from 3 independent experiments. (D) Shows S6 phosphorylation (pS6), and CXCR3 and T-bet expression in splenic and pancreatic CD3+CD4+ T cells on day 16 post BDC2.5 Th1 transfer. Results are representative of three independent experiments. **p < 0.01.

Overall, treatment with Ig-p79 induces a T cell-dependent PD-L1 up-regulation on APCs which in turn interacts with PD-1 and drives mTOC1-mediated tolerance of the T cells.

T cells undergoing mTOR-mediated tolerance display reduced AKTT308 phosphorylation

It is shown above that PD-L1/PD-1 interactions are involved in mTOR-mediated Ag-induced T cell tolerance, we sought to determine whether signaling molecules upstream of mTOR whose activation is under the control of PD-1 signaling would also be implicated in this form of tolerance. AKTT308 which is targeted by PD-1 signaling (29) represents a potential candidate as it also serves to activate mTORC1 (20, 30). To test this premise, we assessed Ig-p79 for down-regulation of AKTT308 phosphorylation. The results show that pAKTT308 level in Th1 cells diminished gradually after Ig-p79 treatment (Fig. S3A). Such a decrease was significant as the MFI levels went down from 669 ± 59 on day 1 after treatment to 326 ± 61 on day 7 post treatment (Fig. S3B). Subsequently, we overexpressed AKT in the Th1 cells and tested for nullification of Ig-p79-induced mTOR-mediated tolerance. In an initial step, the Th1 cells were transduced with AKT retroviral vector, and assessed for increase in the phosphorylation of S6 ribosomal protein and exacerbation of T1D. The findings show that retroviral vector carrying AKT and Thy1.1 genes (AKT RV) transduces Th1 cells like the empty vector (empty RV) incorporating Thy1.1 gene alone (Fig. S4). When the transduced Th1 cells were examined for AKT activation of mTORC1 by means of S6 phosphorylation, there was enhanced level of pS6 that was significantly higher relative to transduction with empty RV, indicating that AKT overexpression is functional (Fig. S4B). In addition, the AKT RV-transduced Th1 cells accelerated T1D manifestation when transferred into NOD.scid mice further confirming that AKT and mTORC1 are involved in T1D (Fig. S4C). Since overexpression of AKT increases the activity of mTORC1, it is logical to foresee the Th1 cells resist Ig-p79-induced tolerance. This prediction proved correct as mice recipient of Th1 cells transduced with AKT RV resist Ig-p79 treatment and develop T1D while animals transferred with Th1 cells transduced with empty RV remain susceptible to Ig-p79 treatment and do not develop T1D (Fig. 6A). Control mice treated with Ig-HEL also develop T1D whether the Th1 cells are transduced with AKT RV or empty RV indicating that resistance to tolerance is Ag-specific (Fig. 6A). The resistance to Ig-p79 tolerance by Th1 cells overexpressing AKT is reflected in their trafficking behavior as they are no longer retained in the spleen (compare 0.9% with empty RV to 0.3% with AKT RV) but migrate efficiently to the pancreas (compare 0.06% with empty RV to 0.5% with AKT RV) (Fig. 6B). The Th1 cells, whether transduced with AKT RV or empty RV migrated to the pancreas when the treatment used Ig-HEL control, again, indicating that overexpression interferes with tolerance in an Ag-specific manner (Fig. 6B).

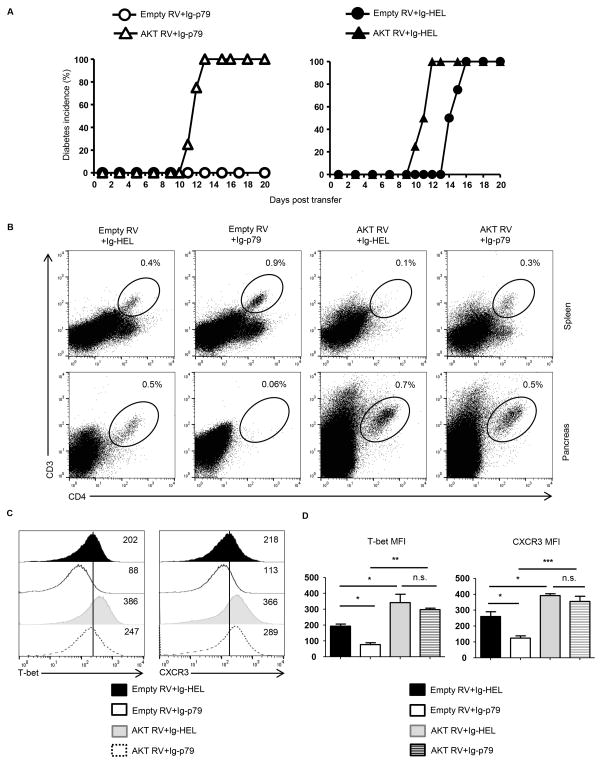

Figure 6. Overexpression of AKT in pathogenic Th1 cells nullifies Ag-induced tolerance.

Th1 BDC2.5 cells transduced with AKT RV or empty RV were transferred (1x 106 cells per mouse) into NOD.scid mice (n = 4 per group) and the hosts were treated with a defined Ig-p79 tolerogenic regimen. (A) Shows disease incidence in Ig-p79 (left panel) and Ig-HEL control (right panel) treated mice. (B) Shows the frequency of residual T cells in spleen and pancreas on day 21 after transfer. (C) Shows T-bet and CXCR3 expression by splenic T cells on day 21 after cell transfer. Results in (A–C) are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Shows MFI of CXCR3 and T-bet expression by splenic T cells of (C). Each bar represents the mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 as determined by ANOVA with a Bonferroni post-test.

The failure of Ig-p79 to block migration of AKT-overexpressing Th1 cells to the pancreas and its inability to suppress their diabetogenicity bodes well with its decreased effectiveness in downregulating T-bet and CXCR3 expression (Fig. 6C). Indeed, Ig-p79 effectively downregulated both T-bet (compare 88 MFI to 202 MFI) and CXCR3 (compare 113 MFI to 218 MFI) expression on empty RV-transduced Th1 cells relative to Ig-HEL and this was statistically significant (Fig. 6C). However, in the Th1 cells overexpressing AKT, the down-regulation of T-bet (compare 247 MFI to 386 MFI) and CXCR3 (289 MFI to 366 MFI) was neither effective nor statistically significant (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that Ig-p79 is no longer able to induce down-regulation of T-bet and CXCR3, retain the cells in the spleen, or modulate the disease when the Th1 cells are overexpressing AKT.

Overall, treatment with Ig-p79 reduces AKT phosphorylation in Th1 cells undergoing mTORC1 –mediated tolerance.

Recruitment of SHP-2 phosphatase by PD-1 is required for inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 pathway

Interaction of PD-L1 on APCs with PD-1 on T cells leads to docking of protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 to the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif (ITSM) of PD-1 which in turn can dephosphorylate a myriad of TCR proximal signaling molecules (29, 31, 32). Since the PI3K/AKTT308 pathway is one of such TCR proximal signaling targets (31), and the latter is involved in mTORC1 activation, we sought to determine whether SHP-2 plays a role in Ig-p79-mediated T cell tolerance. The results show that treatment with Ig-p79 did not alter the level of total SHP-2 expression by diabetogenic Th1 cells in vivo (Fig. 7A). However, docking of SHP-2 to PD-1 was significantly increased relative to treatment with control Ig-HEL (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, the Th1 cells displayed a gradual decrease in the level of pAKTT308 when the treatment with Ig-p79 is compared with the control Ig-HEL (Fig. 7C). This suggests that the increased SHP-2 docking to ITSM of PD-1 is perhaps promoting dephosphorylation of the mTORC1 activator, pAKTT308. In support of this statement is the observation that SHP-2 inhibition restores phosphorylation of both pAKTT308 and pS6 in T cells undergoing PD-L1hi DCIg-79-driven mTORC1-mediated tolerance (Fig. 7D). This could explain the decrease in total mTOR protein on day 7 posttreatment with Ig-p79 as reduced S6 activity would affect translation of mTOR. Overall, these findings indicate that PD-1 regulates the function of SHP-2 phosphatase to control Ag-specific mTORC1-mediated T cell tolerance.

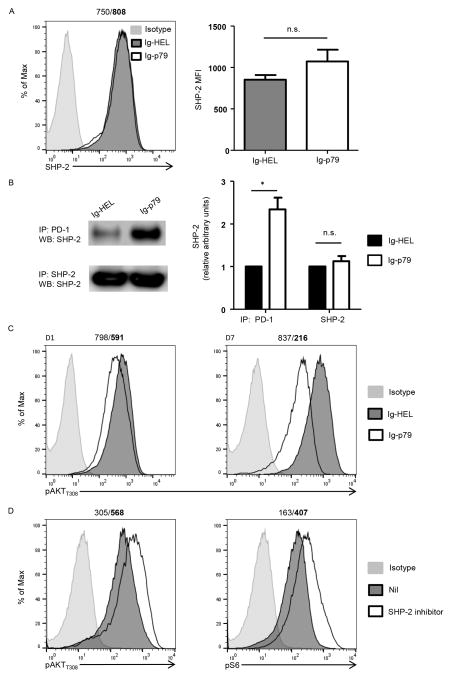

Figure 7. PD-1 utilizes SHP-2 phosphatase to inhibit PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 signaling during T cell tolerance.

(A–C) BDC2.5 Th1 cells were transferred into NOD.scid mice and the hosts were then treated with Ig-p79 or Ig-HEL. (A) Shows expression of SHP2 by splenic CD4+Vβ4+ T cells one day after treatment with the Ig chimeras. The histogram graph (left panel) shows a representative experiment and the bar graph shows the mean ± SEM of MFI (right panel) from 3 independent experiments. (B) Shows co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of PD-1 and SHP-2 in lysates from splenic CD4+Vβ4+ T cells one day after treatment with the Ig chimeras. The top row shows IP with anti-PD-1 and blotting with anti-SHP-2. The bottom row shows total SHP-2 obtained by IP with anti-SHP-2 and blotting with anti-SHP-2 antibody. The right panel shows densitometry analysis from 3 independent experiments (normalized to T cells from Ig-HEL treated mice). *p < 0.05 (C) Shows phosphorylation of AKT (Thr308) in CD4+Vβ4+ T cells on day 1 and 7 after Ig treatment. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. The numbers on top of the panels represent the MFI obtained upon treatment with Ig-HEL/Ig-p79, respectively. (D) Splenic DCIg-p79 loaded with p79 peptide were cultured with naïve BDC2.5 CD4+CD25− T cells with or without (NIL) SHP-2 inhibitor, NSC-87877 (50 μM). Phosphorylation of AKT (Thr308) and S6 in T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry 3 days later. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Interestingly, the role of SHP-2 in regulating PI3K activity appeared to be convoluted. Some reports showed that SHP-2 was required for PI3K activation by growth factors (33), whereas others indicated that SHP-2 interfered with the PI3K pathway in a receptor-specific manner (34). In our treatment model, while PD-1-associated SHP-2 in transferred T cells was increased upon Ig-p79 treatment, phosphorylation of AKT at Thr308 decreased on day 1, and to a larger extent, on day 7 indicating that PI3K activity was continually inhibited following SHP-2 recruitment to PD-1 (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, DCs from Ig-p79 treated NOD.scid mice recipient of BDC2.5 T cells were cultured with naïve BDC2.5 T cells with or without NSC-87877 (35), a potent SHP-2 inhibitor, there was enhanced AKTT308 and S6 phosphorylation suggesting that SHP-2 negatively regulates the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 pathway. Collectively, Ig-p79 treatment escalates PD-L1 expression, which in turn promotes the recruitment of SHP-2 to PD-1 and consequently lead to the impaired PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 function.

Discussion

Ag-induced tolerance specifically targets pathogenic T cells while circumventing generalized immune suppression (3, 36). Mechanisms that tend to physiological peripheral tolerance, including interference with activating costimulation (9), induction of costimulation inhibitory molecules (37), and expansion of T regulatory cells (11, 12) constitute the major ingredients for Ag-specific tolerance. Recently, we reported that interference with cell trafficking and stimulation of apoptosis represent new cellular mechanisms of T cell tolerance that can be induced specifically by Ag treatment (15). APCs play a major role in initiating the tolerance process but the molecular events that incapacitate the T cells remain largely undefined. In this study, we used a robust Ag-specific Th1 tolerance model to delineate the signaling mechanism underlying interference with T cell trafficking and the consequent suppression of T1D. mTOR, a key serine-threonine protein kinase involved in T cell differentiation (20, 30) proved to be a master target for retention of effector Th1 cells in the spleen leading to inhibition of their migration to the pancreas. This new function is attributed to a faded activity of mTORC1 but not mTORC2 in Th1 cells undergoing Ag-induced CXCR3 down-regulation. It has previously been shown that mTORC1 controls trafficking of CD8 T cells through regulation of CD62L and CCR7 under activation regimens (38). Herein, it seems that mTORC1 regulates T-bet and CXCR3 expression under inactivation or tolerance regimen. This mechanism is brought about by APCs through up-regulation of PD-L1 but not PD-L2 costimulation inhibitory molecules during presentation of tolerance inducing Ag. Under these circumstances PD-L1 interacts specifically with PD-1 to trigger modulation of mTORC1 activity by interference with the PI3K pathway.

Indeed, phosphorylation of AKTT308 is reduced significantly during T cell tolerance and blockade of PD-L1/PD-1 interaction with anti-PD-L1 antibody restores AKTT308 phosphorylation, mTORC1 activation, CXCR3 expression and trafficking of the T cells to the pancreas leading to resistance to Ig-p79-induced tolerance. Thus, Ag-induced PD-L1/PD-1 interaction drives T cell tolerance through modulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTORC1 pathway. Although PD-L1 has been shown to control the development of iTregs through down-regulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway (39), our observation is the first instance where PD-L1 is shown to drive tolerance of effector T cells by interference with the PI3K/AKT pathway. Furthermore, we now demonstrate that SHP2 phosphatase serves as a link between PD-L1/PD-1 and modulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Indeed, T cells undergoing antigen-induced tolerance display increased docking of SHP2 phosphatase to PD-1 and inhibition of SHP2 function restores the PI3K/AKT pathways leading to nullification of T cell tolerance. The significance of these findings is two-fold as it demonstrates that the master target for T cell tolerance in this antigen-specific system is mTORC1 and the process is initiated through induction of PD-L1 on APCs. The use of BDC2.5 T cells adds relevance to Ag-induced therapy of T1D as the cells have been shown to react with β-cell-derived hybrid-insulin peptide (40). In addition, one would envision that PD-L1 triggered tolerance is restricted to mTORC1 as activation of mTORC2 remains operative in the T cells undergoing antigen-induced tolerance. The data also suggest that drugs that target mTORC1 could provide an approach to suppress T1D. Moreover, the findings open avenues for PD-L1 expressing DCs or even soluble PD-L1 protein as means to target the disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding. This work was supported by grant R01DK093515 from the National Institutes of Health (to HZ), by funds from the Leda J. Sears Trust and by the J. Lavenia Edwards endowment.

Abbreviations

- AKT

protein kinase B

- Ag

antigen

- CXCR3

CXC chemokine receptor 3

- HEL

hen egg lysosome

- MFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- mTORC1

mammalian target of Rapamycin complex 1

- NOD

non-obese diabetic

- PD-1

programmed death-1

- PD-L1

programmed death-ligand 1

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- RV

Retroviral vector

- S6

ribosomal protein S6

- S6K1

S6 kinase beta-1

- SHP-2

SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase 2

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

- T-bet

T-box protein expressed in T cells

- Tregs

T regulatory cells

References

- 1.Jain R, Tartar DM, Gregg RK, Divekar RD, Bell JJ, Lee HH, Yu P, Ellis JS, Hoeman CM, Franklin CL, Zaghouani H. Innocuous IFNgamma induced by adjuvant-free antigen restores normoglycemia in NOD mice through inhibition of IL-17 production. J Exp Med. 2008;205:207–218. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wan X, Guloglu FB, Vanmorlan AM, Rowland LM, Zaghouani S, Cascio JA, Dhakal M, Hoeman CM, Zaghouani H. Recovery from overt type 1 diabetes ensues when immune tolerance and beta-cell formation are coupled with regeneration of endothelial cells in the pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2013;62:2879–2889. doi: 10.2337/db12-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemente-Casares X, Tsai S, Huang C, Santamaria P. Antigen-specific therapeutic approaches in Type 1 diabetes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a007773. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clemente-Casares X, Blanco J, Ambalavanan P, Yamanouchi J, Singha S, Fandos C, Tsai S, Wang J, Garabatos N, Izquierdo C, Agrawal S, Keough MB, Yong VW, James E, Moore A, Yang Y, Stratmann T, Serra P, Santamaria P. Expanding antigen-specific regulatory networks to treat autoimmunity. Nature. 2016;530:434–440. doi: 10.1038/nature16962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tartar DM, VanMorlan AM, Wan X, Guloglu FB, Jain R, Haymaker CL, Ellis JS, Hoeman CM, Cascio JA, Dhakal M, Oukka M, Zaghouani H. FoxP3+RORgammat+ T helper intermediates display suppressive function against autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2010;184:3377–3385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carreno BM, Collins M. The B7 family of ligands and its receptors: new pathways for costimulation and inhibition of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:29–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.091101.091806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butte MJ, Keir ME, Phamduy TB, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;27:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legge KL, Min B, Potter NT, Zaghouani H. Presentation of a T cell receptor antagonist peptide by immunoglobulins ablates activation of T cells by a synthetic peptide or proteins requiring endocytic processing. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1043–1053. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.6.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legge KL, Min B, Bell JJ, Caprio JC, Li L, Gregg RK, Zaghouani H. Coupling of peripheral tolerance to endogenous interleukin 10 promotes effective modulation of myelin-activated T cells and ameliorates experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2000;191:2039–2052. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.12.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Legge KL, Gregg RK, Maldonado-Lopez R, Li L, Caprio JC, Moser M, Zaghouani H. On the role of dendritic cells in peripheral T cell tolerance and modulation of autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2002;196:217–227. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregg RK, Jain R, Schoenleber SJ, Divekar R, Bell JJ, Lee HH, Yu P, Zaghouani H. A sudden decline in active membrane-bound TGF-beta impairs both T regulatory cell function and protection against autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2004;173:7308–7316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gregg RK, Bell JJ, Lee HH, Jain R, Schoenleber SJ, Divekar R, Zaghouani H. IL-10 diminishes CTLA-4 expression on islet-resident T cells and sustains their activation rather than tolerance. J Immunol. 2005;174:662–670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Judkowski V, Pinilla C, Schroder K, Tucker L, Sarvetnick N, Wilson DB. Identification of MHC class II-restricted peptide ligands, including a glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 sequence, that stimulate diabetogenic T cells from transgenic BDC2.5 nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:908–917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz JD, Wang B, Haskins K, Benoist C, Mathis D. Following a diabetogenic T cell from genesis through pathogenesis. Cell. 1993;74:1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90730-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wan X, Guloglu FB, VanMorlan AM, Rowland LM, Jain R, Haymaker CL, Cascio JA, Dhakal M, Hoeman CM, Tartar DM, Zaghouani H. Mechanisms underlying antigen-specific tolerance of stable and convertible Th17 cells during suppression of autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:2054–2065. doi: 10.2337/db11-1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallet MA, Flores RR, Wang Y, Yi Z, Kroger CJ, Mathews CE, Earp HS, Matsushima G, Wang B, Tisch R. MerTK regulates thymic selection of autoreactive T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4810–4815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900683106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delgoffe GM, Kole TP, Zheng Y, Zarek PE, Matthews KL, Xiao B, Worley PF, Kozma SC, Powell JD. The mTOR kinase differentially regulates effector and regulatory T cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;30:832–844. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delgoffe GM, Pollizzi KN, Waickman AT, Heikamp E, Meyers DJ, Horton MR, Xiao B, Worley PF, Powell JD. The kinase mTOR regulates the differentiation of helper T cells through the selective activation of signaling by mTORC1 and mTORC2. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:295–303. doi: 10.1038/ni.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao RR, Li Q, Odunsi K, Shrikant PA. The mTOR kinase determines effector versus memory CD8+ T cell fate by regulating the expression of transcription factors T-bet and Eomesodermin. Immunity. 2010;32:67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powell JD, Pollizzi KN, Heikamp EB, Horton MR. Regulation of immune responses by mTOR. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:39–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly AP, Finlay DK, Hinton HJ, Clarke RG, Fiorini E, Radtke F, Cantrell DA. Notch-induced T cell development requires phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1. EMBO J. 2007;26:3441–3450. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mondino A, Mueller DL. mTOR at the crossroads of T cell proliferation and tolerance. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu P, Gan W, Inuzuka H, Lazorchak AS, Gao D, Arojo O, Liu D, Wan L, Zhai B, Yu Y, Yuan M, Kim BM, Shaik S, Menon S, Gygi SP, Lee TH, Asara JM, Manning BD, Blenis J, Su B, Wei W. Sin1 phosphorylation impairs mTORC2 complex integrity and inhibits downstream Akt signalling to suppress tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1340–1350. doi: 10.1038/ncb2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mueller DL, Jenkins MK, Schwartz RH. Clonal expansion versus functional clonal inactivation: a costimulatory signalling pathway determines the outcome of T cell antigen receptor occupancy. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:445–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fife BT, Bluestone JA. Control of peripheral T-cell tolerance and autoimmunity via the CTLA-4 and PD-1 pathways. Immunol Rev. 2008;224:166–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L. Co-inhibitory molecules of the B7-CD28 family in the control of T-cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:336–347. doi: 10.1038/nri1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keir ME, Liang SC, Guleria I, Latchman YE, Qipo A, Albacker LA, Koulmanda M, Freeman GJ, Sayegh MH, Sharpe AH. Tissue expression of PD-L1 mediates peripheral T cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2006;203:883–895. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chi H. Regulation and function of mTOR signalling in T cell fate decisions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:325–338. doi: 10.1038/nri3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yokosuka T, Takamatsu M, Kobayashi-Imanishi W, Hashimoto-Tane A, Azuma M, Saito T. Programmed cell death 1 forms negative costimulatory microclusters that directly inhibit T cell receptor signaling by recruiting phosphatase SHP2. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1201–1217. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chemnitz JM, Parry RV, Nichols KE, June CH, Riley JL. SHP-1 and SHP-2 associate with immunoreceptor tyrosine-based switch motif of programmed death 1 upon primary human T cell stimulation, but only receptor ligation prevents T cell activation. J Immunol. 2004;173:945–954. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu CJ, O’Rourke DM, Feng GS, Johnson GR, Wang Q, Greene MI. The tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 is required for mediating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt activation by growth factors. Oncogene. 2001;20:6018–6025. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang SQ, Tsiaras WG, Araki T, Wen G, Minichiello L, Klein R, Neel BG. Receptor-specific regulation of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase activation by the protein tyrosine phosphatase Shp2. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4062–4072. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4062-4072.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L, Sung SS, Yip ML, Lawrence HR, Ren Y, Guida WC, Sebti SM, Lawrence NJ, Wu J. Discovery of a novel shp2 protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:562–570. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoda LK, Young DL, Ramanujan S, Whiting CC, Atkinson MA, Bluestone JA, Eisenbarth GS, Mathis D, Rossini AA, Campbell SE, Kahn R, Kreuwel HT. A comprehensive review of interventions in the NOD mouse and implications for translation. Immunity. 2005;23:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenschow DJ, Zeng Y, Thistlethwaite JR, Montag A, Brady W, Gibson MG, Linsley PS, Bluestone JA. Long-term survival of xenogeneic pancreatic islet grafts induced by CTLA4lg. Science. 1992;257:789–792. doi: 10.1126/science.1323143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinclair LV, Finlay D, Feijoo C, Cornish GH, Gray A, Ager A, Okkenhaug K, Hagenbeek TJ, Spits H, Cantrell DA. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase and nutrient-sensing mTOR pathways control T lymphocyte trafficking. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:513–521. doi: 10.1038/ni.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Francisco LM, V, Salinas H, Brown KE, Vanguri VK, Freeman GJ, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2009;206:3015–3029. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delong T, Wiles TA, Baker RL, Bradley B, Barbour G, Reisdorph R, Armstrong M, Powell RL, Reisdorph N, Kumar N, Elso CM, DeNicola M, Bottino R, Powers AC, Harlan DM, Kent SC, Mannering SI, Haskins K. Pathogenic CD4 T cells in type 1 diabetes recognize epitopes formed by peptide fusion. Science. 2016;351:711–714. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.