Abstract

Mutation accumulation (MA) experiments employ the strategy of minimizing the population size of evolving lineages to greatly reduce effects of selection on newly arising mutations. Thus, most mutations fix within MA lines independently of their fitness effects. This approach, more recently combined with genome sequencing, has detailed the rates, spectra, and biases of different mutational processes. However, a quantitative understanding of the fitness effects of mutations virtually unseen by selection has remained an untapped opportunity. Here, we analyzed the fitness of 43 sequenced MA lines of the multi-chromosome bacterium Burkholderia cenocepacia that had each undergone 5554 generations of MA and accumulated an average of 6.73 spontaneous mutations. Most lineages exhibited either neutral or deleterious fitness in three different environments in comparison with their common ancestor. The only mutational class that was significantly overrepresented in lineages with reduced fitness was the loss of the plasmid, though nonsense mutations, missense mutations, and coding insertion-deletions were also overrepresented in MA lineages whose fitness had significantly declined. Although the overall distribution of fitness effects was similar between the three environments, the magnitude and even the sign of the fitness of a number of lineages changed with the environment, demonstrating that the fitness of some genotypes was environmentally dependent. These results present an unprecedented picture of the fitness effects of spontaneous mutations in a bacterium with multiple chromosomes and provide greater quantitative support for the theory that the vast majority of spontaneous mutations are neutral or deleterious.

Keywords: fitness effects, deleterious mutation, pleiotropy, genetic drift, Burkholderia cenocepacia

THE extent to which spontaneous mutations contribute to evolutionary change largely depends on their rates and fitness effects. Both parameters are fundamental to several evolutionary problems, including the maintenance of genetic variation (Charlesworth et al. 1993, 2009; Charlesworth and Charlesworth 1998), the evolution of recombination (Muller 1964; Kondrashov 1988; Otto and Lenormand 2002; Roze and Blanckaert 2014), the evolution of mutator alleles (Sniegowski et al. 1997; Tenaillon et al. 1999), and deleterious mutation accumulation (MA) in small populations (Lande 1994; Lynch et al. 1995, 1999; Schwander and Crespi 2009). Many studies have now obtained direct and robust estimates of mutation rates and spectra across diverse organisms, but our understanding of the fitness effects of spontaneous mutations remains limited to mostly indirect estimates in classic model organisms (Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007).

MA experiments provide the opportunity to quantify properties of the fitness of spontaneous mutations that have not been exposed to the sieve of natural selection. Specifically, MA experiments limit the efficiency of natural selection by passaging replicate lineages through repeated single-cell bottlenecks. These lineages accumulate mutations independently over several thousand generations, and the magnitude and variance in fitness between lineages can be used to estimate several properties of the distribution of fitness effects (Halligan and Keightley 2009). MA studies have been used to characterize the fitness effects of spontaneous mutations in Drosophila melanogaster (Bateman 1959; Mukai 1964; Keightley 1994; Fry et al. 1999), Arabidopsis thaliana (Schultz et al. 1999; Shaw et al. 2000, 2002), Caenorhabditis elegans (Keightley and Caballero 1997; Vassilieva et al. 2000; Estes et al. 2004; Katju et al. 2015), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Wloch et al. 2001; Zeyl and de Visser 2001; Dickinson 2008; Jasmin and Lenormand 2015), Escherichia coli (Kibota and Lynch 1996; Trindade et al. 2010), and other microbes (Heilbron et al. 2014; Kraemer et al. 2015). Results from these studies have occasionally been inconsistent, but the majority of results suggest that most spontaneous mutations have mild effects (Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007; Halligan and Keightley 2009; Agrawal and Whitlock 2012; Heilbron et al. 2014), that deleterious mutations far outnumber beneficial mutations (Keightley and Lynch 2003; Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007; Silander et al. 2007), and that the distribution of effects of deleterious mutations is complex and multimodal (Zeyl and de Visser 2001; Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007).

A more powerful approach for studying the fitness effects of spontaneous mutations is to pair MA experiments with whole-genome sequencing (MA-WGS), so that both the genetic basis and fitness effects of a collection of mutations can be known. MA-WGS studies have been conducted in a diverse array of bacteria, generating a growing database of naturally accumulated mutations that has dramatically improved estimates of mutation rates and spectra (Lee et al. 2012; Sung et al. 2012, 2015; Heilbron et al. 2014; Long et al. 2014, 2015; Dillon et al. 2015; Foster et al. 2015; Dettman et al. 2016). Yet, only one of these studies has also characterized the fitness of MA-WGS lines (Heilbron et al. 2014), and this study was conducted with mutator lineages, which have altered base substitution and indel biases and produce hundreds of mutations per line (Lee et al. 2012; Sung et al. 2015). Our understanding of the fitness effects of spontaneous mutations would benefit greatly from more direct estimates of fitness derived from MA lineages that harbor fewer known mutations.

Here, we measured the relative fitness of 43 fully sequenced MA lineages derived from Burkholderia cenocepacia HI2424 in three laboratory environments after they had been evolved in the near absence of natural selection for 5554 generations. Following the MA experiment, each lineage harbored a total mutational load of 2–14 spontaneous mutations, including base substitution mutations (bpsms), insertion-deletion mutations (indels), and whole-plasmid deletions. By correlating the relative fitnesses of these MA lineages with the particular mutations that they harbor, we present a detailed picture of the fitness effects of spontaneous mutations, and precise estimates of deleterious mutation rates and fitness effects in a clinically important gamma-proteobacterium with multiple chromosomes.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

All MA experiments were founded from a single colony of B. cenocepacia HI2424, which was isolated from the soil and only passaged in the laboratory during isolation (Coenye and LiPuma 2003). As a member of the diverse B. cepacia complex, B. cenocepacia can form highly resistant biofilms and has been associated with persistent lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis (Mahenthiralingam et al. 2005; Traverse et al. 2013). The genome of B. cenocepacia HI2424 has been fully sequenced and is composed of three chromosomes (Chr1: 3.48 Mb, 3253 genes; Chr2: 3.00 Mb, 2709 genes; Chr3: 1.06 Mb, 929 genes) and a plasmid (0.164 Mb, 159 genes), though the third chromosome can be eliminated under some conditions in some strains (Agnoli et al. 2012). We obtained the whole-genome sequences of each of these chromosomes from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), and downloaded the codon usage information from the Codon Usage Database (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/). To facilitate relative fitness assays, we competed all B. cenocepacia HI2424 strains derived from the MA experiment with a B. cenocepacia HI2424 Lac+ strain that is isogenic to B. cenocepacia HI2424, except for the introduction of the lacZ gene at the attTn7 site which causes colonies to turn blue when exposed to 5-bromo-4-chloro-indolyl-β-galactopyranoside (X-gal) (Choi et al. 2005).

MA experiments were conducted on tryptic soy agar plates (TSA) [30 g/liter tryptic soy broth (TSOY) powder, 15 g/liter agar] and were incubated at 37°. At the conclusion of the MA experiment, frozen stocks were prepared by growing a single colony from each lineage overnight in 5 ml of TSOY (30 g/liter TSOY powder) at 37° and freezing at –80° in 8% DMSO. All relative fitness assays were conducted in 18 × 150 mm glass capped tubes with 5 ml of liquid medium and were maintained at 37° in a roller drum (30 rpm). Relative fitness of each lineage was assayed in three different environments. First, we conducted relative fitness assays in TSOY, a medium that mimics the conditions of the MA experiment and is expected to be very permissive. Second, we conducted relative fitness assays in M9 Minimal Medium supplemented with 0.3% casamino acids (M9MM+CAA) [3 g/liter CAA powder, 1 g/liter glucose, 6 g/liter sodium phosphate dibasic anhydrous (Na2HPO4 • 2H2O), 3 g/liter potassium phosphate monobasic (KH2PO4), 1 g/liter ammonium chloride, 0.5 g/liter sodium chloride (NaCl), 0.1204 g/liter magnesium sulfate, and 0.0147 g/liter calcium chloride], a medium that is more nutrient restrictive than TSOY but contains all essential amino acids except tryptophan. Lastly, we conducted relative fitness assays in M9MM (1 g/liter glucose, 6 g/liter Na2HPO4 • 2H2O, 3 g/liter KH2PO4, 1 g/liter ammonium chloride, 0.5 g/liter NaCl, 0.1204 g/liter magnesium sulfate, and 0.0147 g/liter calcium chloride), which is a fully defined medium that is more restrictive than either TSOY or M9MM+CAA. Serial passaging during fitness assays was performed using 100-fold dilutions, so all relative fitness assays were conducted over the same number of generations, despite the moderately different carrying capacities in these mediums. All dilutions were performed using PBS (80 g/liter NaCl, 2 g/liter KCl, 14.4 g/liter Na2HPO4 • 2H2O, 2.4 g/liter KH2PO4) in 96-well plates.

MA-WGS process

The MA experiment that generated the mutational load for this study has been reported previously (Dillon et al. 2015). Briefly, 75 independent lineages were founded from a single colony of B. cenocepacia HI2424 and independently propagated every 24 hr onto a fresh TSA plate for 217 days. Daily generations were estimated monthly by taking a single representative colony from each lineage following 24 hr of growth, placing it in 2 ml of PBS, then serially diluting and spread plating it on TSA. The number of viable cells in each colony was then used to calculate the number of generations elapsed between each transfer, and the average number of generations across all lineages was used as the number of generations per day for that entire month. By multiplying the number of generations per day for each month by the number of days in that month, then summing these totals over the course of the whole experiment, we calculated the total number of generations elapsed per MA lineage over the course of the MA experiment.

As we have described previously, genomic DNA was extracted from 1 ml of overnight TSB culture founded by 47 of the B. cenocepacia isolates that were stored at the conclusion of the MA experiment (Dillon et al. 2015). We used the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit for DNA extraction (Promega), all libraries were prepared using a modified Illumina Nextera protocol (Baym et al. 2015), and sequencing was performed with the 151-bp paired end platform on the Illumina HiSeq at the Hubbard Center for Genomic Studies at the University of New Hampshire. Following fastQC analysis, all reads were mapped to the B. cenocepacia HI2424 reference genome (LiPuma et al. 2002) with both the Burrows–Wheeler aligner (BWA) (Li and Durbin 2009) and Novoalign (http://www.novocraft.com). The average depth of coverage across all 47 lines was 43 ×, but the average depth of coverage in the 43 lines used in this study was 46 ×.

Spontaneous mutation identification

All bpsms were identified as described previously (Dillon et al. 2015). Briefly, after using a combination of SAMtools and in-house perl scripts to produce all read alignments for each position in each line (Li et al. 2009), a three-step process was used to detect putative bpsms. First, pooled reads across all lines were used to generate an ancestral consensus base at each site in the reference genome, allowing us to correct differences between the published reference genome and the ancestral colony of our MA experiment. Second, reads from the individual lines were used to generate a lineage-specific consensus base at each site in the reference genome for each lineage, as long as the site was covered by at least two forward and two reverse reads, and at least 80% of the reads identified the same base. Sites that did not meet these criteria were not analyzed in the respective lineage. Third, lineage-specific consensus bases for each lineage were compared to the ancestral consensus base at each site, and a putative bpsm was identified if they differed. This three-step process was carried out independently using both the BWA and Novoalign alignments, and putative bpsms were considered genuine only if both pipelines independently identified the bpsm. Despite these lenient criteria, all of the bpsms that were identified at analyzed sites in this study had considerably greater coverage and consensus than the minimal criteria (see Supplemental Material, File S1), demonstrating that these bpsms are not merely false positives in low coverage regions. Further, randomly selected bpsms identified in E. coli and Bacillus subtilus MA lines have been verified with Sanger sequencing at the Indiana Molecular Biology Institute, demonstrating that 88/88 bpsms identified using this pipeline were genuine (Lee et al. 2012; Sung et al. 2015). The frequency of sites that were not analyzed in each lineage varied from 0.005 to 0.177. Putative bpsms in these regions were estimated by multiplying the number of unanalyzed sites in each lineage by the overall bpsm rate calculated in this study [1.31 (0.08) × 10−10/bp/generation] and the number of generations of MA in each lineage (5554) (see Table S1).

Indels and large structural variants are inherently more difficult to identify than bpsms because gaps and SSRs reduce the accuracy of short-read alignment algorithms. To overcome these issues, we extracted all putative indels if at least 30% of the reads that covered the site identified the exact same indel (size and motif), and the site was covered by at least two forward and two reverse reads (Dillon et al. 2015). These putative indels were then subject to a series of more strenuous filters based on the complexity of the region in which they were identified and the consensus between the BWA and Novoalign alignments (see File S1). Specifically, all putative indels where more than 80% of the reads identified the exact same indel in both the BWA and Novoalign alignments were considered genuine indels. For putative indels, where only 30–80% of the reads identified the exact same indel, we parsed out only reads that had bases covering both the upstream and downstream region of the indel (if it was not in an SSR), and both the upstream and downstream region of the SSR (if it was in an SSR). Using this subset of reads, we reassessed the frequency of reads that identified the exact same indel, allowing us to more accurately identify indels involving the gain or loss of a single repeat within a SSR. These indels were considered genuine if more than 80% of the parsed reads identified the exact same indel and were discarded if they did not. Putative indels and other structural variants were also extracted using PINDEL, which uses paired-end information to identify insertions, deletions, inversions, tandem duplications, and other structural variants (Ye et al. 2009). Here, indels were considered genuine if they were covered by at least six forward and six reverse reads, and at least 80% of the reads identified the exact same indel. Lastly, we analyzed the distribution of coverage between chromosomes and the 0.164-Mb plasmid to detect any chromosomal copy number variants. As with bpsms, putative indels in regions that were not analyzed were estimated by multiplying the number of unanalyzed sites in each lineage by the overall indel rate calculated in this study [2.39 (0.34) × 10−11/bp/generation] and the number of generations of MA in each lineage (5554) (see Table S1). Randomly selected indels from B. subtilis identified with this pipeline were also verified by amplification of a 300- to 500-bp region surrounding the indel. For short indels (< 10 bp), 29/29 were confirmed to be genuine. For longer indels (> 10 bp), only 2/9 regions could be amplified, but both were confirmed to contain genuine long indels by PCR product sizing (Sung et al. 2015, 2016).

Quantifying relative fitness

To quantify the selection coefficients of each of the 43 derived MA lineages, we conducted 3-day competitions (over ≈19.93 generations) between each MA lineage and our B. cenocepacia HI2424 Lac+ strain. These competitions were carried out independently in TSOY, M9MM+CAA, and M9MM, with four replicates being conducted for each lineage in each environment. Our MA ancestral B. cenocepacia HI2424 strain was also competed against B. cenocepacia HI2424 Lac+ as a control, with four replicates for each environment. Selection coefficients were estimated as described previously, using the relative growth of the focal MA lineage and the B. cenocepacia HI2424 Lac+ reference strain, normalized by the number of generations elapsed by the reference strain () (Chevin 2011; Perfeito et al. 2014). First, the difference in growth () between the two strains was estimated as:

where and were the initial numbers of test and reference bacteria, respectively, and were the final numbers of test and reference bacteria, respectively. Selection coefficients () were then calculated as:

where , generations elapsed by the reference strain, is equal to:

For each replicate, all 43 derived MA lineages, B. cenocepacia HI2424, and B. cenocepacia Lac+ were resurrected from frozen culture by inoculating them into 5 ml of TSOY broth and incubating overnight in a roller drum at 30 rpm. Depending on which environment was being assayed, each strain was then transferred to fresh TSOY, M9MM+CAA, or M9MM via a 10,000-fold dilution and acclimated for 24 hr at 37° and 30 rpm. Following acclimation, 44 competitions (43 MA lineages + control) were generated in the appropriate fresh medium at a 1:1 ratio via 100-fold dilution, and 30 μl from each was extracted to quantify the initial frequency of each competitor (, ). Competitions were then incubated for 72 hr at 37° and 30 rpm, being transferred to fresh media every 24 hr via a 100-fold dilution. At the conclusion of the 72 hr competition, 30 μl of the final culture was extracted to quantify the final frequency of each competitor (, ).

To measure the initial frequency of each competitor, the extracted culture was diluted in PBS and 100 μl of the diluted sample was plated on a TSA + X-gal plate. Specifically, in the TSOY competitions the samples were diluted 30,000-fold, in the M9MM+CAA competitions the samples were diluted to 20,000-fold, and in the M9MM competitions the samples were diluted to 10,000-fold. Following a 48-hr incubation, the number of white and blue colonies were quantified and used to calculate and , respectively, after accounting for the dilutions. Final frequencies were measured in the same way, except that an additional 100-fold dilution was required for each competition because the cultures were at carrying capacity. In addition, to calculate and , we had to account for the dilutions that were conducted prior to plating and the two 100-fold dilutions that were conducted during the 3-day competition. Importantly, the selection coefficient of the B. cenocepacia HI2424 MA ancestor was not significantly different from 0 in any of environments [TSOY: s = –0.0002 (0.0020), M9MM+CAA: s = +0.0075 (0.0030), and M9MM: s = –0.0016 (0.0034) (SEM)].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R Version 0.98.1091 using the Stats analysis package (R Core Team 2014). For all data presented herein, Shapiro–Wilk tests were performed to test whether the data violate the assumption of a normal distribution. Unless otherwise noted, the data did not violate a normal distribution and the mean and SEM were presented. If the data were not normally distributed, the results of the Shapiro–Wilk test were reported and the mean and SD were presented.

For independent two-tailed t-tests, all P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using a Benjamini–Hochberg correction (Table S2), which ensures that our false positive rate remains below 5%, despite testing whether the selection coefficient differed significantly from 0 for 43 lineages in each environment (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). Corrected P-values that were below a threshold of 0.05 were considered significant. Nonparametric Spearman’s Rank correlations were used to evaluate the correlation between the number of mutations in a lineage and its selection coefficient, as well as the correlation between the selection coefficients of lineages in different environments. Lastly, to test for effects of replicate, genotype, environment, and genotype×environment interaction on the fitness of each lineage, we performed an ANOVA on the cumulative data set.

Data availability

Illumina DNA sequences for the B. cenocepacia MA lines used in this study are available under the PRJNA326274 bioproject. File S1 contains all the information on the location and criteria used to identify each bpsm and indel identified in this study. All strains are available upon request.

Results

We previously reported the rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in wild-type B. cenocepacia, as determined from the cumulative results of a MA-WGS experiment involving 47 replicate lineages derived from B. cenocepacia HI2424 (Dillon et al. 2015). Each lineage was passaged through daily single-cell bottlenecks for 217 days, resulting in approximately 5554 generations of MA per lineage. The average number of generations of growth per day within a colony declined from 26.16 ± 0.06 (SEM) to 24.92 ± 0.07 (SEM) over the course of the experiment, suggesting that some of the accumulated mutations had deleterious fitness effects. However, reduction in colony size may be influenced by factors unrelated to fitness, such as the density of surrounding colonies, and fail to reflect cumulative changes in the many stages of bacterial growth. In contrast, direct competitions of these isolates with their ancestor can yield robust estimates of the fitness effects of their mutational load, incorporating all facets of bacterial growth. Here, we present a detailed picture of the fitness effects of the spontaneous mutations accumulated at the conclusion of this MA-WGS experiment using 43 replicate lineages, as the remaining four lineages were discarded because of a lack of sufficient coverage in the WGS data.

The properties of the mutations found in these 43 lineages are consistent with constant mutation rates and limited selection over the course of our experiment. Neither the distribution of bpsms or indels across lineages differed significantly from a Poisson distribution (bpsms: χ2 = 3.46, P = 0.94; indels: χ2 = 0.28, P = 0.96), signifying that mutation rates did not vary across the lineages. The ratio of synonymous to nonsynonymous bpsms (1:2.96) also did not differ from the expected ratio (1:2.74) based on the codon-usage and %GC content at synonymous and nonsynonymous sites in B. cenocepacia HI2424 (χ2 = 0.78, d.f. = 1, P = 0.38), which suggests minimal purifying selection. Further, the lack of genetic parallelism in the bpsm spectra across lineages (see File S1) is inconsistent with positive selection acting on these lines. Lastly, the genome of B. cenocepacia is composed of 6,787,380 bp (88.12%) coding DNA and 915,460 bp (11.88%) noncoding DNA. Although both bpsms and indels were observed more frequently than expected in noncoding DNA (bpsms: χ2 = 2.19, d.f. = 1, P = 0.14; indels: χ2 = 45.816, d.f. = 1, P < 0.0001), a pattern consistent with purifying selection, this pattern could be generated by selection against coding mutations, preferential mismatch repair in coding regions, or the mutation prone nature of repetitive DNA in noncoding regions (Lee et al. 2012; Heilbron et al. 2014; Dillon et al. 2015). In any event, we estimate that the threshold selection coefficient below which genetic drift will overpower natural selection, as determined by in haploid organisms, is 0.08 (Dillon et al. 2015). Thus, while a small class of adaptive or deleterious mutations with effects in excess of s = 0.08 will be subject to the biases of natural selection (Kimura 1983; Elena et al. 1998; Zeyl and de Visser 2001; Hall et al. 2008), the vast majority of mutations that were observed in this study are likely fixed irrespective of their fitness effects.

Genetic basis of spontaneous mutations

The spontaneous bpsms and indels reported here are similar to those reported previously (Dillon et al. 2015), with a few exceptions. First, we allowed for bpsms to be called in more than one lineage, resulting in the addition of two bpsms. These bpsms are assumed to have occurred in the ancestral colony, but their presence in each lineage must be documented to accurately quantify the relationship between the fitness of each lineage and its mutational load. Second, we were able to confidently identify nine additional indels that occurred in simple sequence repeats by using an approach that considers only reads anchored on both sides of the repeat (see Materials and Methods; File S1). These indels may contribute substantively to the mutational load of the lineages in which they occur, so they were important to include in this study. Lastly, we did not analyze four of the lineages from the previous study because < 80% of their genomes had sufficient coverage to be analyzed for the presence of bpsms and indels (see Materials and Methods). This low coverage would render us blind to a considerable portion of the mutational load in these lineages, which warranted their exclusion. Using this data set, we estimate a bpsm rate of 0.001 (6.02 × 10−5)/genome/generation, an indel rate of 0.0002 (2.62 × 10−5) /genome/generation, and a rate of plasmid loss of 1.67 × 10−5 (8.17 × 10−6)/genome/generation (SEM). which are similar to the rates that we reported previously but reflect the differences in our data sets described above (Dillon et al. 2015).

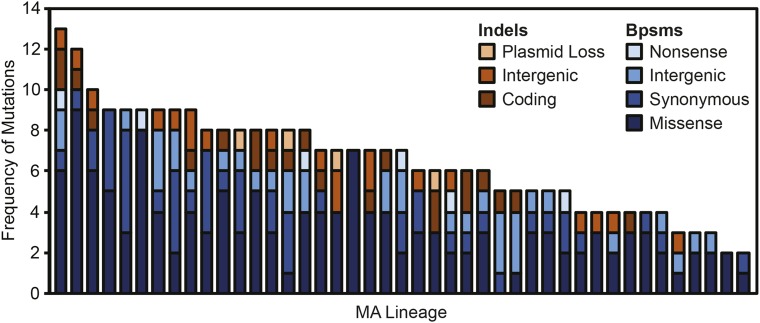

Among the 43 MA lineages, 233 bpsms, 42 short indels, and four plasmid loss events were identified. The most common class of bpsms was missense bpsms (141), followed by synonymous bpsms (49), intergenic bpsms (37), and nonsense bpsms (6). Among indels, coding indels involving only a single gene (22) were slightly more common than intergenic indels (20), while loss of the 0.16-Mb plasmid, which encodes 157 genes, was observed in four lineages (see Figure 1). False-negative rates were estimated in each lineage as the number of sites that were not analyzed for mutations, multiplied by the product of experiment-wide bpsm and indel rates per bp per generation and the number of generations experienced by each lineage. Given that an average of 95.20% of each genome was sequenced to sufficient depth to analyze both bpsms and indels, we estimate that an average of only 0.25 additional bpsms and 0.05 additional indels would have been identified per lineage if the entire genome was analyzed (see Table S1). Overall, mutations were not uniformly distributed across the 43 MA lineages, allowing us to analyze which mutation types are most likely to have fitness effects.

Figure 1.

Distribution of base substitution mutations (bpsms) and insertion-deletion mutations (indels) across the 43 mutation accumulation lineages derived from B. cenocepacia HI2424 analyzed in this study. MA, mutation accumulation.

Fitness effects of spontaneous mutations

Fitness of the final isolate from each lineage was measured by direct competition with the ancestral B. cenocepacia HI2424 strain in three different broth culture conditions. TSOY broth is a very permissive medium used to mimic the conditions of the MA experiment, M9MM+CAA is an amino acid-supplemented minimal medium that is less permissive than TSOY but more permissive than a strictly minimal medium, and M9MM is a fully defined minimal medium that is the least permissive of the three environments. We compared the carrying capacity of B. cenocepacia HI2424 in each environment to assess their relative permissiveness. As expected, TSOY broth had the highest carrying capacity [92.33 × 108 (12.02 × 108) CFU/ml], M9MM + CAA had the second highest carrying capacity [43.05 × 108 (2.68 × 108) CFU/ml], and M9MM had the lowest carrying capacity [17.98 × 108 (2.79 × 108) CFU/ml] (SEM) (Figure S1).

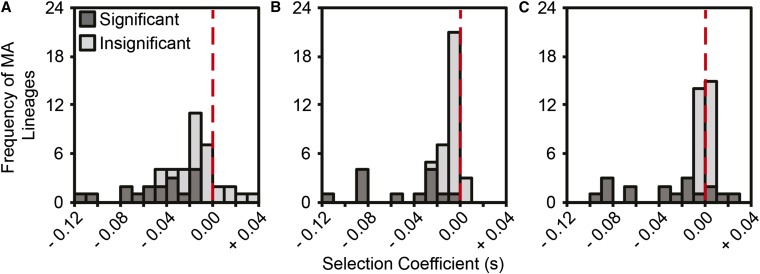

In TSOY, all lineages with selection coefficients > s = 0.05, and some lineages with selection coefficients between s = 0.01 and s = 0.05, could be statistically distinguished from the ancestral strain. In sum, a total of 17 lineages had significantly reduced fitness and no lineages had significantly increased fitness (see Figure 2A). The average fitness across all MA lineages in TSOY was –0.024 ± 0.030 (SD), with a range of –0.111 to +0.037, and was not normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk’s Test; W = 0.95, P = 0.04). Similarly, 13 lineages had significantly reduced fitness in M9MM+CAA and none had significantly increased fitness (see Figure 2B). However, in M9MM+CAA, all lineages with selection coefficients > s = 0.03 and some lineages with selection coefficients as low as s = 0.009 could be statistically distinguished from the ancestral strain. The average fitness decline and the range across all MA lineages in M9MM+CAA were similar to those observed in TSOY [average: –0.020 ± 0.030 (SD); range: –0.116 to +0.006; Shapiro–Wilk’s Test: W = 0.68, P = 2.02 × 10−8]. Lastly, the power of our fitness assays was greatest in M9MM, where some selection coefficients as low as s = 0.005 could be statistically distinguished from the ancestral strain. Here, we observed 13 lineages with significantly reduced fitness in M9MM, but also four lineages with significantly increased fitness (see Figure 2C). The average fitness decline of the MA lineages in M9MM was only –0.013 ± 0.030 (SD), and the fitness distribution was shifted toward more beneficial effects (–0.090 to +0.026) (Shapiro–Wilk’s Test; W = 0.73, P = 1.44 × 10−7). Because each lineage harbors multiple mutations, the distributions presented in Figure 2 cannot be used directly to elucidate the distribution of effects of individual spontaneous mutations, but all pairwise comparisons of these distributions confirm that the distribution of lineage fitnesses are distinct for each environment (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test; TSOY-M9MM+CAA: D = 0.3023, P = 0.0393; TSOY-M9MM: D = 0.5349, P = 9.082 × 10−6; M9MM+CAA-M9MM: D = 0.4186, P = 0.0011). In spite of these differences, the fitness distributions in all three environments demonstrate that the majority of lineages have neutral or moderately deleterious fitness and include an extended left tail with lineages whose fitnesses have declined more dramatically.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the selection coefficients of each B. cenocepacia MA lineage relative to the ancestral B. cenocepacia HI2424 strain in tryptic soy broth (A), M9 minimal medium supplemented with casamino acids (M9MM+CAA) (B), and M9MM (C). Significance was determined from independent two-tailed t-tests on four replicate fitness assays for each lineage. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using a Benjamini–Hochberg correction, and corrected P-values that remained below 0.05 were considered significant. MA, mutation accumulation.

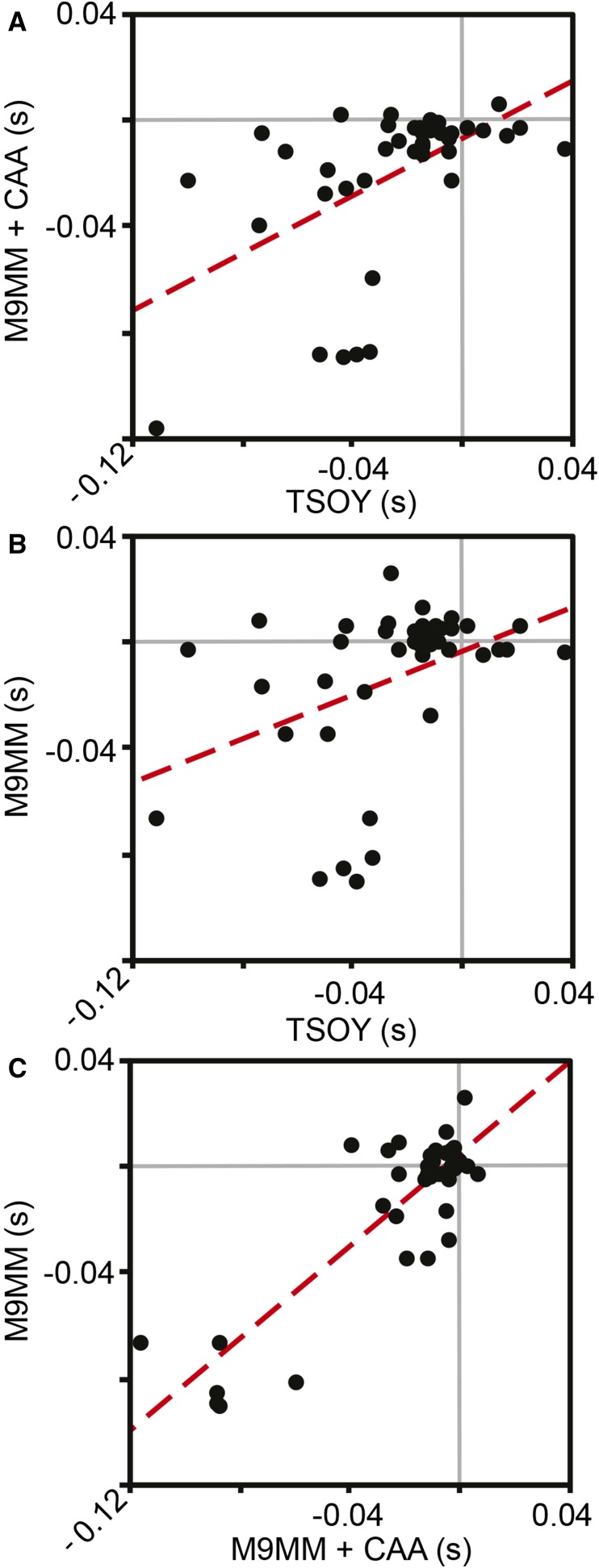

Significant positive correlations between the selection coefficients of individual MA lineages across environments suggest that effects of experiment-wide mutational load interacted with these external environments only modestly (see Figure 3). Specifically, the selection coefficients of each lineage in TSOY and both M9MM+CAA and M9MM were positively correlated (Spearman rank correlations: TSOY-M9MM+CAA: d.f. = 41, S = 6321, rho = 0.5228, P = 0.0003; TSOY-M9MM: d.f. = 41, S = 8402, rho = 0.3656, P = 0.0159). Selection coefficients in M9MM+CAA and M9MM were also significantly correlated (d.f. = 41, S = 6400, rho = 0.5167, P = 0.0004) (see Figure 3). However, the fitness of certain MA lineages declined significantly in one environment but not others, suggesting that some mutations in these lineages produced environment-dependent effects. A total of nine lineages were significantly less fit in a single environment (four TSOY, two M9MM+CAA, and three M9MM), eight MA lineages were significantly less fit in two of the environments, and six MA lineages were significantly less fit in all three environments. Overall, fitness was significantly influenced by replicate, genotype, environment, and genotype-by-environment interaction (see Table 1). Yet, as noted above, the general properties of the distribution of fitness effects of these MA lineages remained similar across the three tested environments (see Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Relationship between selection coefficients of all MA lineages in each of the different pairs of environments. All Spearman’s rank correlations are significant, but much of the variance is unexplained. (A): d.f. = 41, S = 6321, rho = 0.5228, P = 0.0003; (B): d.f. = 41, S = 8402, rho = 0.3656, P = 0.0159; and (C): d.f. = 41, S = 6400, rho = 0.5167, P = 0.0004. CAA, casamino acids; M9 minimal medium, M9MM; MA, mutation accumulation; TSOY, tryptic soy broth.

Table 1. An experiment-wide ANOVA of the fitness of the 43 final mutation accumulation lines in each of three environments, measured in four replicates per treatment.

| Effect | d.f. | SS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replicate | 3 | 0.0037 | 10.02 | < 0.0001 |

| Line | 42 | 0.3302 | 63.72 | < 0.0001 |

| Environment | 2 | 0.0190 | 76.90 | < 0.0001 |

| Genotype×environment | 84 | 0.1166 | 11.25 | < 0.0001 |

Despite acquiring multiple mutations, the fitness of a number of MA lineages did not differ significantly from the ancestral strain. Further, the number of spontaneous mutations in a line did not correlate with their absolute selection coefficients in any environment (Spearman’s rank correlation; TSOY: d.f. = 41, S = 15742, rho = –0.1886, P = 0.2257; M9MM+CAA: d.f. = 41, S = 13190, rho = 0.0041, P = 0.9793; and M9MM: d.f. = 41, S = 16293, rho = –0.2303, P = 0.1374) (see Figure S2). After adding the 11 additional mutations presumed to have been missed in the unanalyzed genomic regions across all lines, we estimate that a total of 290 spontaneous mutations occurred in the experiment, with an average of 6.73 ± 0.36 (SEM) mutations per lineage. In combination, these results suggest that the fitness effects of a majority of spontaneous mutations were near neutral, or at least undetectable, with plate-based laboratory fitness assays. Given the average selection coefficient of each line and the number of mutations that it harbors, we can estimate that the average fitness effect (s) of a single mutation was –0.0040 ± 0.0052 (SD) in TSOY, –0.0031 ± 0.0044 (SD) in M9MM+CAA, and –0.0017 ± 0.0043 (SD) in M9MM.

Because the fitness of many lineages with multiple mutations did not significantly differ from the ancestor, and because mutation number and fitness were not correlated, this study suggests that most of the significant losses and gains in fitness were caused by rare, single mutations with large fitness effects. Based on this conjecture, we can use the number of lineages that experienced significantly reduced fitness (17 in TSOY, 13 in M9MM+CAA, and 13 in M9MM) divided by the total generations of MA across all lines to estimate the deleterious mutation rate per genome per generation (UD) in each environment. Estimates of UD based on this approach are 7.12 10−5/genome/generation in TSOY, 5.44 10−5/genome/generation in M9MM+CAA, and 5.44 10−5/genome/generation in M9MM. The fitness effects of these single deleterious mutations (sD) in some lineages can also be estimated directly from the fitness of these select lineages relative to the B. cenocepacia HI2424 ancestor, and suggest an average sD of –0.048 ± 0.007 (SEM) in TSOY, –0.053 ± 0.011 (SEM) in M9MM+CAA, and –0.048 ± 0.009 in M9MM (SEM). Although we observe no significantly beneficial mutations in TSOY or M9MM+CAA, our data suggest that the beneficial mutation rate (UB) is 1.68 10−5/genome/generation and the average significantly beneficial mutation has a selection coefficient (sB) of 0.013 ± 0.005 (SEM) in M9MM. The primary caveats to these estimates are that they assume that only one of the mutations in each lineage determines its fitness, that none of the lineages that are statistically indistinguishable from the ancestral strain harbor deleterious mutations, and that they do not account for epistasis between the mutations accumulated in each lineage. To attain more precise estimates of UD, sD, UB, and sB, studying spontaneous mutations in different combinations and using more precise fitness assays based on flow cytometry and/or barcoded sequencing will be especially valuable.

Genetic basis of deleterious load

Without sequencing and measuring fitness at intermediate time-points or genetically engineering B. cenocepacia HI2424 strains that harbor only single spontaneous mutations, it is difficult to pinpoint which mutations generate the fitness declines in our MA lineages. However, we can examine relationships between the forms of mutational load harbored by each lineage and the fitness of those lineages (Figure 1). The only mutation type that was significantly overrepresented in lineages with reduced fitness in TSOY was the loss of the 0.164-Mb plasmid (χ2 = 6.12, d.f. = 1, P = 0.0130). All four lineages that lost the plasmid were significantly less fit in TSOY, with an average selection coefficient of –0.060 ± 0.007 (SEM). These same four lineages were also less fit in M9MM (χ2 = 9.23, d.f. = 1, P = 0.0020; mean s = –0.043 ± 0.018), but the deleterious effects of plasmid loss appear to be mitigated in M9MM+CAA, where only one of these lineages had significantly reduced fitness.

Although no other mutation types were significantly overrepresented among lineages that had reduced fitness, we note that there were more coding indels, nonsense bpsms, and missense bpsms than expected in the lineages with reduced fitness in all three environments, with the exception of coding indels in M9MM+CAA (see Table 2). In contrast, intergenic bpsms, synonymous bpsms, and intergenic indels appear to be more evenly distributed between lineages with significantly reduced fitness and those where s was not significantly different from 0, but because these forms of mutation were rarer overall, it is difficult to say whether this is because noncoding mutations with deleterious effects are less common (see Table 2). Overall, these results are suggestive that some coding indels, nonsense bpsms, and missense bpsms have deleterious effects, but we lack sufficient evidence to say whether the same is true for intergenic mutations and synonymous bpsms.

Table 2. Chi-tests comparing the observed number of mutations in lineages with significantly reduced fitness, relative to the expected amounts given the proportion of the total lineages that had significantly reduced fitness.

| Mutation Type | Environment | Observed | Expected | χ2 | d.f. | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intergenic bpsm | TSOY | 13 | 14.63 | 0.2996 | 1 | 0.5841 |

| Synonymous bpsm | TSOY | 16 | 19.37 | 0.9708 | 1 | 0.3245 |

| Missense bpsm | TSOY | 60 | 55.74 | 0.5374 | 1 | 0.4635 |

| Nonsense bpsm | TSOY | 4 | 2.37 | 1.8477 | 1 | 0.1741 |

| Intergenic indel | TSOY | 8 | 7.91 | 0.0018 | 1 | 0.9661 |

| Coding indel | TSOY | 12 | 8.70 | 2.0736 | 1 | 0.1499 |

| Plasmid loss | TSOY | 4 | 1.58 | 6.1176 | 1 | 0.0134 |

| Total mutations | TSOY | 117 | 110.30 | 0.6726 | 1 | 0.4121 |

| Intergenic bpsm | M9MM+CAA | 12 | 11.19 | 0.0849 | 1 | 0.7708 |

| Synonymous bpsm | M9MM+CAA | 15 | 14.81 | 0.0033 | 1 | 0.9539 |

| Missense bpsm | M9MM+CAA | 47 | 42.63 | 0.6427 | 1 | 0.4227 |

| Nonsense bpsm | M9MM+CAA | 3 | 1.81 | 1.1115 | 1 | 0.2917 |

| Intergenic indel | M9MM+CAA | 6 | 6.05 | 0.0005 | 1 | 0.9819 |

| Coding indel | M9MM+CAA | 6 | 6.65 | 0.0914 | 1 | 0.7624 |

| Plasmid loss | M9MM+CAA | 1 | 1.21 | 0.0519 | 1 | 0.8198 |

| Total mutations | M9MM+CAA | 90 | 84.35 | 0.5427 | 1 | 0.4613 |

| Intergenic bpsm | M9MM | 10 | 11.19 | 0.1803 | 1 | 0.6712 |

| Synonymous bpsm | M9MM | 15 | 14.81 | 0.0033 | 1 | 0.9539 |

| Missense bpsm | M9MM | 50 | 42.63 | 1.8274 | 1 | 0.1764 |

| Nonsense bpsm | M9MM | 2 | 1.81 | 0.0274 | 1 | 0.8686 |

| Intergenic indel | M9MM | 6 | 6.05 | 0.0005 | 1 | 0.9819 |

| Coding indel | M9MM | 8 | 6.65 | 0.3921 | 1 | 0.5312 |

| Plasmid loss | M9MM | 4 | 1.21 | 9.2308 | 1 | 0.0024 |

| Total mutations | M9MM | 95 | 84.35 | 1.9278 | 1 | 0.1650 |

bpsm, base substitution mutation; indels insertion-deletion mutation; TSOY, tryptic soy broth; M9MM+CAA, M9 minimal medium supplemented with casamino acids; M9MM, M9 minimal medium.

Discussion

Nearly all prior research on the fitness effects of mutations has studied mutants that have been screened by selection, which presumably purged deleterious variants and enriched beneficial ones. MA experiments are designed to minimize effects of selection to the greatest extent possible, thus capturing most mutations independent of the biases of natural selection. Combining this MA approach with WGS and fitness measurements provides the potential to dramatically advance our understanding of the fitness effects of spontaneous mutations in diverse organisms. Here, we analyzed the fitness effects of 43 lineages of B. cenocepacia that underwent 7 months or > 5500 generations of evolution under greatly limited selection. Direct competitions with the common ancestor were conducted in three environments to quantify effects of different forms of mutational load. Despite the duration of MA, many lineages evidently suffered no fitness decline, as they had selection coefficients that did not significantly differ from s = 0. Given that each lineage accumulated between 2–14 mutations, the most likely explanation for these findings is that the vast majority of spontaneous mutations have minimal effects on fitness across this range of environments. Under the assumption that the significant reductions in lineage fitness were driven mostly by single deleterious mutations (Davies et al. 1999; Heilbron et al. 2014), we also obtain new estimates of the deleterious mutation rate (UD) and the average effect of deleterious mutations (sD) in all three environments. These measures reveal that the general features of the distribution of fitness effects are similar between these conditions, even though the distribution of effects for the lineages are distinct in each environment. The most consistently deleterious mutational event involved loss of the 0.164-Mb plasmid, which reduced fitness in TSOY and M9MM but not M9MM+CAA. Further, nonsense bpsms, missense bpsms, and coding indels appear to be more likely to have contributed to the deleterious mutational load that synonymous bpsms, intergenic bpsms, and intergenic indels.

Although a few select studies have claimed that a substantial fraction of spontaneous mutations are beneficial under certain conditions (Shaw et al. 2002; Silander et al. 2007; Dickinson 2008), evidence from diverse sources strongly suggests that the effect of most spontaneous mutations is to reduce fitness (Kibota and Lynch 1996; Keightley and Caballero 1997; Fry et al. 1999; Vassilieva et al. 2000; Wloch et al. 2001; Zeyl and de Visser 2001; Keightley and Lynch 2003; Trindade et al. 2010; Heilbron et al. 2014). Our measurements of selection coefficients in TSOY also suggest that most spontaneous mutations are neutral or deleterious because all lineages whose fitness differs significantly from the ancestor are less fit (s = –0.112 to –0.014). The overall distribution of selection coefficients of our lineages in TSOY also has a clear mode near s = 0 and among lineages whose selection coefficients cannot be statistically distinguished from s = 0, most are clearly negative (Chi-square test; χ2 = 7.54, d.f. = 1, P = 0.0060) (see Figure 2). However, whether this is the only mode in the distribution, or stems from the inability of our MA experiments to fix deleterious mutations with fitness effects below the selection threshold of s = –0.078 remains uncertain.

Whether the environment affects the fitness effects of spontaneous mutations has also been the subject of considerable debate. Specifically, some studies have shown that larger declines in fitness are experienced in harsher environments, while others have not (Martin and Lenormand 2006; Halligan and Keightley 2009; Kraemer et al. 2015). In M9MM+CAA and M9MM, we can statistically distinguish fitness effects from s = 0 with greater precision (s < –0.03 in M9MM+CAA and s < –0.01 or s > 0.01 in M9MM), likely because the formulations for these media are more defined. These media are also expected to be more stringent for growth than TSOY because nutrients are more limited. Although all distributions have a mode of near s = 0 and contain mostly lineages with deleterious or neutral fitness, we show that the distribution of effects across lineages is distinct for each environment (see Figure 2). One important difference is that M9MM contains four lineages that are significantly more fit than the ancestor, and unlike in TSOY and M9MM+CAA, lineages whose selection coefficients are not significantly different from 0 in M9MM are no more likely to be negative than they are to be positive (Chi-square test; χ2 = 0, d.f. = 1, P = 1) (see Figure 2). This suggests that fewer spontaneous mutations are deleterious for fitness in M9MM, possibly because a greater proportion of genes are unused when metabolizing only a single carbon substrate. Furthermore, a number of lineages whose selection coefficients were significantly different from s = 0 in one environment were near neutral in other environments. Overall, these data suggest that the fitness effects of some individual spontaneous mutations interact with the growth environment, despite the similarities in the properties of the distribution of fitness effects among the three environments assayed in this study (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Quantitative estimates of the rates and fitness effects of spontaneous mutations have received considerable interest because of their fundamental importance for the population genetics of evolving systems (Keightley and Lynch 2003; Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007; Lynch 2008a,b, 2010; Halligan and Keightley 2009). Specifically, in an effort to unveil some general properties of the distribution of fitness effects of spontaneous mutations, estimates of the average selection coefficient of spontaneous mutations (s) (Lynch et al. 2008; Halligan and Keightley 2009; Trindade et al. 2010; Heilbron et al. 2014), the rate of deleterious mutations (UD) (Kibota and Lynch 1996; Trindade et al. 2010), and the average selection coefficient of deleterious mutations (sD) (Kibota and Lynch 1996; Trindade et al. 2010; Heilbron et al. 2014) have been derived using both direct and indirect approaches. Here, we estimate that s ≅ 0 in all three environments, largely because the vast majority of mutations appear to have near neutral effects on fitness. These estimates are remarkably similar to estimates from studies of MA lines with fully characterized mutational load in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. cerevisiae (Lynch et al. 2008; Heilbron et al. 2014), but are lower than estimates derived from unsequenced MA lineages (Halligan and Keightley 2009; Trindade et al. 2010). However, it is important to consider that, while our data suggest that the vast majority of spontaneous mutations in B. cenocepacia have very low selection coefficients in the laboratory, it should not imply that all of these mutations are effectively neutral in natural conditions. In fact, sequence analyses in enteric bacteria have revealed that < 2.8% of amino acid changing mutations are evolving neutrally, and this may be an overestimate due to the presence of adaptive mutations (Charlesworth and Eyre-Walker 2006; Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007).

From this study, we were also able to directly estimate the deleterious mutation rates (UD ≈ 5 × 10−5) and the mean fitness effects of deleterious mutations (sD ≈ –0.05) in each environment under the presumption that only one mutation is responsible for the fitness declines experienced by a subset of our lineages (TSOY: UD = 7.12× 10−5 /genome/generation, sD = –0.048; M9MM+CAA: UD = 5.44 × 10−5/genome/generation, sD = –0.053; and M9MM: UD = 5.44 × 10−5 /genome/generation, sD = –0.048). This assumption is warranted given that more than 5000 generations of MA had no significant effects on lineage fitness in the majority of our lineages, and that there was no significant correlation between the number of mutations in a lineage and its fitness. Further, time-series data from prior studies have supported that single, large-effect mutations disproportionately dictate the realized fitness in the majority of MA lineages (Davies et al. 1999; Heilbron et al. 2014).

Without knowledge of the genetic basis of all spontaneous mutations in each lineage, prior bacterial MA studies have used the Bateman–Mukai (BM) approach to estimate UD and sD (Kibota and Lynch 1996; Trindade et al. 2010). This method assumes that the number of newly arising deleterious mutations is Poisson distributed and that the effects of deleterious mutations are multiplicative, then uses the rate of fitness decline and increase in among line fitness variance to calculate UD and sD. Specifically, UD can be estimated as and sD is estimated as , where is the slope of the natural log of the mean fitness across all lines and is the slope of the natural log of (Trindade et al. 2010). Applying the BM method to our data yields UD estimates of 1.84 × 10−4, 1.35 × 10−4, and 6.91 × 10−5/genome/generation in TSOY, M9MM+CAA, and M9MM, respectively. These estimates are remarkably similar to the estimates from this study derived from genome sequencing and BM estimates from an earlier MA study in wild-type E. coli (1.35 × 10−4/genome/generation) (Kibota and Lynch 1996), but are considerably lower than estimates from a mutator E. coli MA study (5.00 × 10−3/genome/generation) (Trindade et al. 2010), as expected. The BM method also yields estimates of sD (TSOY: sD = –0.037; M9MM+CAA: sD = –0.045; and M9MM: sD = –0.070) that are similar to our sequencing-dependent estimates and estimates from both prior MA studies in E. coli (Kibota and Lynch 1996; Trindade et al. 2010).

It is likely that both the difficulty of resolving the fitness of mutations of small effects and the effects of selection in our MA experiments on mutations with s > 0.078 interfere with our estimates of UD and sD. While the latter selective bias is an inevitable consequence of the MA approach, future studies can enhance resolution of subtle fitness effects by employing flow cytometry and/or barcoding techniques (Gallet et al. 2012; Levy et al. 2015; Dillon et al. 2016). Furthermore, by extending these methods to a growing database of archived MA-WGS studies in diverse organisms and analyzing the effects of spontaneous mutations in different combinations, we will soon be able to evaluate the extent to which properties of the distribution of fitness effects vary between species and the epistatic deviation associated with mutations in different genetic backgrounds (Elena and Lenski 1997; Silander et al. 2007; Dickinson 2008; Schaack et al. 2013; Jasmin and Lenormand 2015; Behringer and Hall 2016).

Significantly, beneficial mutations were only observed in M9MM and in no lineage did the selective coefficient exceed s = 0.03. These limited observations prevent us from performing any detailed analyses on the rate and distribution of effects of beneficial mutations, but they support the notion that beneficial mutations are rare relative to deleterious mutations (Keightley and Lynch 2003). Furthermore, they suggest that most beneficial mutations likely provide only moderate benefits, even though the beneficial mutations that often fix in experimental populations can have large beneficial effects (Lenski et al. 1991; Ostrowski et al. 2005; Lang et al. 2013; Levy et al. 2015). As was the case for deleterious mutations, the number and average effects of beneficial mutations observed in this study are likely to be downwardly biased due to the impacts of other mutations in the same MA background that are mostly deleterious, which will further increase the value of sequencing and measuring the fitness of our lineages at intermediate time-points in future studies.

It is a well-established dogma in evolutionary biology that mutations that disrupt coding sequences are most likely to affect fitness, but this has never been quantitatively tested with naturally accumulated mutations. Specifically, mutations that frequently generate nonfunctional proteins, like nonsense bpsms or coding indels, are expected to have the most deleterious effects, followed by missense bpsms that mostly generate modified proteins, then synonymous and noncoding mutations that do not alter protein sequences. The fitness effects of plasmid gain and loss are less certain, as the size and genetic content of plasmids vary, but they may be energetically expensive to maintain (Smith and Bidochka 1998). Consequently, plasmids may be selectively lost in permissive laboratory environments where maintenance of the plasmid has a fitness cost (Lenski and Bouma 1987; Smith and Bidochka 1998). Our data suggest that although loss of the 0.164-Mb plasmid in B. cenocepacia occurs at an appreciable rate in the absence of selection during our MA experiments, it is universally deleterious to lose the plasmid in TSOY and M9MM. However, these effects appear to be mitigated in M9MM+CAA, signifying that these fitness losses are related to amino acid synthesis. Therefore, these data suggest that, in permissive laboratory conditions, the loss of some plasmids can be deleterious and not just advantageous for growth as is widely presumed. Other mutation types were not significantly overrepresented in lineages with significantly reduced fitness (see Table 2), but we do find that there are slightly more nonsense bpsms, missense bpsms, and coding indels than expected in lineages with significantly reduced fitness. This supports the expectation that protein-modifying mutations do affect fitness in some cases, but the relative rarity of synonymous and intergenic mutations in this study makes it difficult to say whether the same is true for these forms of mutation, which can also be under selective constraints (Eyre-Walker and Keightley 2007; Bailey et al. 2014).

The rate and fitness effects of spontaneous mutations are fundamental quantities that will help explain a number of evolutionary phenomena, including the origin and maintenance of genetic variation in natural populations (Charlesworth et al. 1993, 2009; Charlesworth and Charlesworth 1998), the evolution of recombination (Muller 1964; Kondrashov 1988; Otto and Lenormand 2002; Roze and Blanckaert 2014), the evolution of mutator alleles (Sniegowski et al. 1997; Tenaillon et al. 1999), and the mutational meltdown of small populations (Lande 1994; Lynch et al. 1995, 1999; Schwander and Crespi 2009). Although our methods show that the majority of spontaneous mutations in B. cenocepacia do not produce detectable fitness effects in any of three laboratory environments, natural selection may be operating on many of these sites in natural populations (Charlesworth and Eyre-Walker 2006). Still, our data suggest that purifying selection may act weakly on much of the variation generated by spontaneous mutation, allowing mutation pressure to substantively influence the genetic variation in natural populations under some conditions. The low frequencies of highly deleterious or beneficial alleles observed in this study may also have implications for our understanding of the evolution of recombination and mutation rates. Specifically, the benefits of reassorting genomes to separate deleterious and beneficial mutations (to avoid Muller’s ratchet), or to combine beneficial mutations and accelerate adaptation (the Fisher–Muller hypothesis) might be reduced under conditions where both deleterious and beneficial mutations are rare (Zeyl and Bell 1997; Otto and Lenormand 2002; de Visser and Elena 2007), like those observed in this study. Mutator alleles may also be tolerated for longer periods if they fail to produce detectable deleterious load, thereby giving them more time to hitchhike to fixation by producing a highly beneficial allele. Indeed, mutator alleles have been frequently observed in experimental (Sniegowski et al. 1997), clinical (Mena et al. 2008; Oliver 2010; Silva et al. 2016), and environmental studies (Hall and Henderson-Begg 2006; Hazen et al. 2009). Lastly, the bias for spontaneous mutations to be deleterious rather than beneficial in B. cenocepacia is consistent with studies in a number of species (Kibota and Lynch 1996; Keightley and Caballero 1997; Fry et al. 1999; Vassilieva et al. 2000; Wloch et al. 2001; Zeyl and de Visser 2001; Keightley and Lynch 2003; Trindade et al. 2010; Heilbron et al. 2014), suggesting that gradual mutational meltdown may be inevitable for populations where the efficiency of natural selection is reduced (Sniegowski and Lenski 1995; Lynch et al. 1999).

By measuring the fitness effects of MA lineages with fully characterized mutational load, we have performed a uniquely systematic study of the rate and fitness effects of spontaneous mutations with known genetic bases, demonstrating that the vast majority of mutations accumulated in B. cenocepacia MA lines are neutral or deleterious for fitness, and that the fitness of individual mutations can be environmentally dependent, even though the general features of the distribution of fitness effects are similar in different environments. Furthermore, we have provided new estimates for several parameters of the distribution of fitness effects of spontaneous mutations derived from genotypes with known mutational load. Although considerable uncertainty remains with respect to the shape and parameters that define the distribution of fitness effects, by extending these methods to a growing database of MA studies, many of which have archived time-series data, we are now poised to dramatically enhance our understanding of the true nature of the distribution of fitness effects of spontaneous mutations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Science Foundation Career Award (DEB-0845851) to V.S.C.

Author contributions: M.M.D. and V.S.C. designed the research; M.M.D. performed the research; M.M.D. analyzed the data; and M.M.D. and V.S.C. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: L. M. Wahl

Supplemental material is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.116.193060/-/DC1.

Literature Cited

- Agnoli K., Schwager S., Uehlinger S., Vergunst A., Viteri D. F., et al. , 2012. Exposing the third chromosome of Burkholderia cepacia complex strains as a virulence plasmid. Mol. Microbiol. 83: 362–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal A. F., Whitlock M. C., 2012. Mutation load: the fitness of individuals in populations where deleterious alleles are abundant. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 43: 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey S. F., Hinz A., Kassen R., 2014. Adaptive synonymous mutations in an experimentally evolved Pseudomonas fluorescens population. Nat. Commun. 5: 4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A. J., 1959. The viability of near-normal irradiated chromosomes. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1: 170–180. [Google Scholar]

- Baym M., Kryazhimskiy S., Lieberman T. D., Chung H., Desai M. M., et al. , 2015. Inexpensive multiplexed library preparation for megabase-sized genomes. PLoS One 10: e0128036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behringer M. G., Hall D. W., 2016. The repeatability of genome-wide mutation rate and spectrum estimates. Curr. Genet. 1: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y., 1995. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J.R. Stat. Soc. 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B., Charlesworth D., 1998. Some evolutionary consequences of deleterious mutations. Genetica 102–103: 3–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth J., Eyre-Walker A., 2006. The rate of adaptive evolution in enteric bacteria. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23: 1348–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B., Morgan M. T., Charlesworth D., 1993. The effect of deleterious mutations on neutral molecular variation. Genetics 134: 1289–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B., Betancourt A. J., Kaiser V. B., Gordo I., 2009. Genetic recombination and molecular evolution, pp. 177–186 in Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevin L.-M., 2011. On measuring selection in experimental evolution. Biol. Lett. 7: 210–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K.-H., Gaynor J. B., White K. G., Lopez C., Bosio C. M., et al. , 2005. A Tn7-based broad-range bacterial cloning and expression system. Nat. Methods 2: 443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenye T., LiPuma J. J., 2003. Population structure analysis of Burkholderia cepacia genomovar III: varying degrees of genetic recombination characterize major clonal complexes. Microbiology 149: 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies E. K., Peters A. D., Keightley P. D., 1999. High frequency of cryptic deleterious mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 285: 1748–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman J. R., Sztepanacz J. L., Kassen R., 2016. The properties of spontaneous mutations in the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. BMC Genomics 17: 27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser J. A. G. M., Elena S. F., 2007. The evolution of sex: empirical insights into the roles of epistasis and drift. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson W. J., 2008. Synergistic fitness interactions and a high frequency of beneficial changes among mutations accumulated under relaxed selection in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 178: 1571–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon M. M., Sung W., Lynch M., Cooper V. S., 2015. The rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in the GC-rich multichromosome genome of Burkholderia cenocepacia. Genetics 200: 935–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon M. M., Rouillard N. P., Van Dam B., Gallet R., Cooper V. S., 2016. Diverse phenotypic and genetic responses to short-term selection in evolving Escherichia coli populations. Evolution (N. Y.) 70: 586–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elena S. F., Lenski R. E., 1997. Test of synergistic interactions among deleterious mutations in bacteria. Nature 390: 395–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elena S. F., Ekunwe L., Hajela N., Oden S. A., Lenski R. E., 1998. Distribution of fitness effects caused by random insertion mutations in Escherichia coli. Genetica 102: 349–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes S., Phillips P. C., Denver D. R., Thomas W. K., Lynch M., 2004. Mutation accumulation in populations of varying size: the distribution of mutational effects for fitness correlates in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 166: 1269–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A., Keightley P. D., 2007. The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster P. L., Lee H., Popodi E., Townes J. P., Tang H., 2015. Determinants of spontaneous mutation in the bacterium Escherichia coli as revealed by whole-genome sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112: E5990–E5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry J. D., Keightley P. D., Heinsohn S. L., Nuzhdin S. V., 1999. New estimates of the rates and effects of mildly deleterious mutation in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 574–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallet R., Cooper T. F., Elena S. F., Lenormand T., 2012. Measuring selection coefficients below 10(-3): method, questions, and prospects. Genetics 190: 175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall L. M. C., Henderson-Begg S. K., 2006. Hypermutable bacteria isolated from humans - a critical analysis. Microbiology 152: 2505–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall D. W., Mahmoudizad R., Hurd A. W., Joseph S. B., 2008. Spontaneous mutations in diploid Saccharomyces cerevisiae: another thousand cell generations. Genet. Res. 90: 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halligan D. L., Keightley P. D., 2009. Spontaneous mutation accumulation studies in evolutionary genetics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 40: 151–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hazen T. H., Kennedy K. D., Chen S., Yi S. V., Sobecky P. A., 2009. Inactivation of mismatch repair increases the diversity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Environ. Microbiol. 11: 1254–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbron K., Toll-Riera M., Kojadinovic M., Maclean R. C., 2014. Fitness is strongly influenced by rare mutations of large effect in a microbial mutation accumulation experiment. Genetics 197: 981–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasmin J., Lenormand T., 2016. Accelerating mutational load is not due to synergistic epistasis or mutator alleles in mutation accumulation lines of yeast. Genetics 202: 751–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katju V., Packard L. B., Bu L., Keightley P. D., Bergthorsson U., 2015. Fitness decline in spontaneous mutation accumulation lines of Caenorhabditis elegans with varying effective population sizes. Evolution (N. Y.) 69: 104–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley P. D., 1994. The distribution of mutation effects on viability in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 138: 1315–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley P. D., Caballero A., 1997. Genomic mutation rates for lifetime reproductive output and lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 3823–3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keightley P. D., Lynch M., 2003. Toward a realistic model of mutations affecting fitness. Evolution (N. Y.) 57: 683–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibota T. T., Lynch M., 1996. Estimate of the genomic mutation rate deleterious to overall fitness in E. coli. Nature 381: 694–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M., 1983. The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov A. S., 1988. Deleterious mutations and the evolution of sexual reproduction. Nature 336: 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer S. A., Morgan A. D., Ness R. W., Keightley P. D., Colegrave N., 2015. Fitness effects of new mutations in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii across two stress gradients. J. Evol. Biol. 29: 583–593 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande R., 1994. Risk of population extinction from fixation of new deleterious mutations. Evolution (N. Y.) 48: 1460–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang G. I., Rice D. P., Hickman M. J., Sodergren E., Weinstock G. M., et al. , 2013. Pervasive genetic hitchhiking and clonal interference in forty evolving yeast populations. Nature 500: 571–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Popodi E., Tang H. X., Foster P. L., 2012. Rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in the bacterium Escherichia coli as determined by whole-genome sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: E2774–E2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenski R. E., Bouma J. E., 1987. Effects of segregation and selection on instability of plasmid pACYC184 in Escherichia coli B. J. Bacteriol. 169: 5314–5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenski R. E., Rose M. R., Simpson S. C., Tadler S. C., 1991. Long-term experimental evolution in Escherichia coli. 1. Adaptation and divergence during 2,000 generations. Am. Nat. 138: 1315–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. F., Blundell J. R., Venkataram S., Petrov D. A., Fisher D. S., et al. , 2015. Quantitative evolutionary dynamics using high-resolution lineage tracking. Nature 519: 181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R., 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., et al. , 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LiPuma J. J., Spilker T., Coenye T., Gonzalez C. F., 2002. An epidemic Burkholderia cepacia complex strain identified in soil. Lancet 359: 2002–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long H., Sung W., Miller S. F., Ackerman M. S., Doak T. G., et al. , 2014. Mutation rate, spectrum, topology, and context-dependency in the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficient Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC948. Genome Biol. Evol. 7: 262–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long H., Kucukyildirim S., Sung W., Williams E., Lee H., et al. , 2015. Background mutational features of the radiation-resistant bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32: 2383–2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., 2008a Estimation of nucleotide diversity, disequilibrium coefficients, and mutation rates from high-coverage genome-sequencing projects. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25: 2409–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., 2008b The cellular, developmental and population-genetic determinants of mutation-rate evolution. Genetics 180: 933–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., 2010. Evolution of the mutation rate. Trends Genet. 26: 345–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., Conery J., Burger R., 1995. Mutation accumulation and the extinction of small populations. Am. Nat. 146: 489–518. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., Blanchard J., Houle D., Kibota T., Schultz S., et al. , 1999. Perspective: spontaneous deleterious mutation. Evolution (N. Y.) 53: 645–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., Sung W., Morris K., Coffey N., Landry C. R., et al. , 2008. A genome-wide view of the spectrum of spontaneous mutations in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 9272–9277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahenthiralingam E., Urban T. A., Goldberg J. B., 2005. The multifarious, multireplicon Burkholderia cepacia complex. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3: 144–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G., Lenormand T., 2006. The fitness effect of mutations across environments: a survey in light of fitness landscape models. Evolution 60: 2413–2427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena A., Smith E. E., Burns J. L., Speert D. P., Moskowitz S. M., et al. , 2008. Genetic adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to the airways of cystic fibrosis patients is catalyzed by hypermutation. J. Bacteriol. 190: 7910–7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukai T., 1964. Genetic structure of natural populations of Drosophila Melanogaster. 1. Spontaneous mutation rate of polygenes controlling viability. Genetics 50: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller H. J., 1964. The relation of recombination to mutational advance. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1: 2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver A., 2010. Mutators in cystic fibrosis chronic lung infection: prevalence, mechanisms, and consequences for antimicrobial therapy. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300: 563–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski E. A., Rozen D. E., Lenski R. E., 2005. Pleiotropic effects of beneficial mutations in Escherichia coli. Evolution (N. Y.) 59: 2343–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto S. P., Lenormand T., 2002. Resolving the paradox of sex and recombination. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3: 252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perfeito L., Sousa A., Bataillon T., Gordo I., 2014. Rates of fitness decline and rebound suggest pervasive epistasis. Evolution (N. Y.) 68: 150–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2014 R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at: http://www.R-project.org/.

- Roze D., Blanckaert A., 2014. Epistasis, pleiotropy, and the mutation load in sexual and asexual populations. Evolution (N. Y.) 68: 137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaack S., Allen D. E., Latta L. C., Morgan K. K., Lynch M., 2013. The effect of spontaneous mutations on competitive ability. J. Evol. Biol. 26: 451–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz S. T., Lynch M., Willis J. H., 1999. Spontaneous deleterious mutation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96: 11393–11398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwander T., Crespi B. J., 2009. Twigs on the tree of life? Neutral and selective models for integrating macroevolutionary patterns with microevolutionary processes in the analysis of asexuality. Mol. Ecol. 18: 28–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw R. G., Byers D. L., Darmo E., 2000. Spontaneous mutational effects on reproductive traits of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 155: 369–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw F. H., Geyer C. J., Shaw R. G., 2002. A comprehensive model of mutations affecting fitness and inferences for Arabidopsis thaliana. Evolution 56: 453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silander O. K., Tenaillon O., Chao L., 2007. Understanding the evolutionary fate of finite populations: the dynamics of mutational effects. PLoS Biol. 5: e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva I. N., P. M. Santos, M. R. Santos, J. E. A. Zlosnik, D. P. Speert, et al., 2016 Long-term evolution of Burkholderia multivorans during a chronic cystic fibrosis infection reveals shifting forces of selection. mSystems DOI: 10.1128/mSystems.00029-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Smith M. A., Bidochka M. J., 1998. Bacterial fitness and plasmid loss: the importance of culture conditions and plasmid size. Can. J. Microbiol. 44: 351–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniegowski P. D., Lenski R. E., 1995. Mutation and adaptation - the directed mutation controversy in evolutionary perspective. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 26: 553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Sniegowski P. D., Gerrish P. J., Lenski R. E., 1997. Evolution of high mutation rates in experimental populations of E. coli. Nature 387: 703–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung W., Ackerman M. S., Miller S. F., Doak T. G., Lynch M., 2012. Drift-barrier hypothesis and mutation-rate evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 18488–18492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung W., Ackerman M. S., Gout J.-F., Miller S. F., Williams E., et al. , 2015. Asymmetric context-dependent mutation patterns revealed through mutation-accumulation experiments. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32: 1672–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung W., Ackerman M. S., Dillon M. M., Platt T. G., Fuqua C., et al. , 2016. Evolution of the insertion-deletion mutation rate across the tree of life. G3 (Bethesda) 9: 2583–2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenaillon O., Toupance B., Le Nagard H., Taddei F., Godelle B., 1999. Mutators, population size, adaptive landscape and the adaptation of asexual populations of bacteria. Genetics 152: 485–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traverse C. C., Mayo-Smith L. M., Poltak S. R., Cooper V. S., 2013. Tangled bank of experimentally evolved Burkholderia biofilms reflects selection during chronic infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: E250–E259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trindade S., Perfeito L., Gordo I., 2010. Rate and effects of spontaneous mutations that affect fitness in mutator Escherichia coli. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365: 1177–1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilieva L. L., Hook A. M., Lynch M., 2000. The fitness effects of spontaneous mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Evolution (N. Y.) 54: 1234–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wloch D. M., Szafraniec K., Borts R. H., Korona R., 2001. Direct estimate of the mutation rate and the distribution of fitness effects in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 159: 441–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K., Schulz M. H., Long Q., Apweiler R., Ning Z. M., 2009. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics 25: 2865–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeyl C., Bell G., 1997. The advantage of sex in evolving yeast populations. Nature 388: 465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeyl C., de Visser J. A., 2001. Estimates of the rate and distribution of fitness effects of spontaneous mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 157: 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Illumina DNA sequences for the B. cenocepacia MA lines used in this study are available under the PRJNA326274 bioproject. File S1 contains all the information on the location and criteria used to identify each bpsm and indel identified in this study. All strains are available upon request.