Abstract

The Well London programme was launched across twenty boroughs in London during late 2007 to improve the health and well-being of residents living in some of the most deprived communities in London. Well London employed a multi-stage community engagement process which informed the overall project strategy for each intervention area. In this article we establish and describe the key principles that guided the design of this innovative community engagement process. Principles included building collaborative partnerships, working with whole-systems, privileging community knowledge and working with the deficit of experience in each area. The article then describes in detail how these principles were operationalised throughout the preparation and delivery of forty World Cafes, which were the first open community activities of the Well London community engagement process. Finally, this article reflects on and summarises the lessons learned when employing innovative, inclusive and transparent community engagement for health promotion.

Keywords: Health Improvement, Community Engagement, Whole-systems, Methodologies, World Café

1. Introduction

In 2006, the Big Lottery advertised a call for proposals for intervention programmes to promote wellbeing in communities, with a special focus on increasing the uptake of healthy eating choices, increasing levels of healthy physical activity, and enhancing mental health and wellbeing. The London Health Commission brought together a partnership (the Well London Alliance) which included six other organisations, including the University of East London (UEL), which prepared and delivered a proposal called Well London.

The aim of the Well London programme was to use community engagement and development approaches to design and deliver a three year programme of coordinated project interventions targeted at twenty of the most deprived Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs) across twenty London boroughs. The target LSOAs were matched with a control LSOA within each borough as part of a wider complex evaluation RCT (Wall et al, 2009).

In July 2007, funding of £9.4m was awarded. The first stage of the programme was to design and deliver the Well London Community Engagement Process (WLCEP) to involve the targeted communities in identifying the important challenges they faced in improving their wellbeing and in developing a portfolio of projects which would address these. The Institute for Health and Human Development at UEL, in partnership with Allison Trimble1, developed an approach which built on best practice, and the experience of key organisations with a reputation for effective models of engagement and relationship building including the Bromley-by-Bow centre in Tower Hamlets2. WLCEP used elements of Whole Systems thinking and Future Methods including the World Café (Brown and Isaacs, 2005) and Appreciative Inquiry (Cooperrider and Srivistva, 1987).

In this paper, we describe the principles which lay behind our approach and how these were elaborated into an effective community engagement process in practice. The paper then focuses on how the first component of WLCEP, a series of World Cafés was delivered and draws out some of the lessons learned.

2. Key Principles

2.1. Build a collaborative relationship with local communities

The phrase community ownership is often used by external providers who are funded to deliver community development in deprived communities. Sadly it is frequently a misnomer for simply involving local people in the activities, rather than offering any real power or control to the community. Conflict typically arises when a project has to be led by the external provider because they are accountable to the funder. Inevitably this locates ownership and balance of power with the external provider rather than the community particularly as issues around perceived lack of skill and capacity within the community often arise (Ansari, 2002). Accepting this pitfall, a more honest approach may be to work in partnership between the external provider and the community employing the principle of mutuality. The project then becomes a partnership led exploration of how to creatively meet the communities’ needs and at the same time meet unavoidable funding or research method constraints. Within this a working relationship can develop that implements partnership principles. Levy, Baldyga and Jurkowski (2003) describe these principles within a university and community organisation research context which includes a shared commitment to collective decision making and collective action.

A collaborative partnership with local communities can be developed through the direct engagement with locally based community organisations that have existing and long-term relations within the community. Building on existing social capital in this way provides access to trusted relationships and local intelligence. The partnering external organisation brings with it fresh ideas, skills, approaches and funding to complement the learning that already exists within the community.

2.2. Discover what is unheard

The needs of a community can be understood through collection and interpretation of information from multiple sources. Because statutory agencies typically own the power to define legitimate needs, needs assessment and the design of a response to those needs is often based on analysis of routine statistics, consultations among local professionals and partners, and technical information about the effectiveness of interventions (Stevens and Rafferty, 2004). In consequence the “unheard” knowledge of communities about their own needs remains “unknown” to those commissioning or delivering interventions. “Unheard” knowledge is often located in the experience of communities and individuals who have, for whatever reason, been excluded or have excluded themselves from the ongoing discussions and assessments. These are often communities and individuals which statutory bodies and third sector organisations find difficult to reach or hear. Services and interventions may as a result be inappropriate, inaccessible and underperform. More recently, and in recognition of this, the perspectives of members of the community concerned have been more widely recognised as representing another form of expert knowledge which may be key for understanding complex needs and for the design and delivery of effective services. This co-production approach is now advocated by Government including through the Duty to Involve (DCLG, 2007) and NICE Guidelines for Community Engagement (NICE, 2008), and also aligns with the Big Society agenda (Conservative, 2009).

A key principle, therefore, in the design of any community engagement approach is to ensure that this local knowledge is surfaced, and that hard-to-reach groups are engaged in way which teases out the most useful information, while avoiding consultation fatigue (Cropper et al, 2000).

2.3. Privilege community knowledge and experience

Once communities have been engaged with, it is necessary to privilege their knowledge and experience and to enable their free expression without the influence of existing power relationships or pre-existing knowledge.

Traditional methods of consultation such as focus groups, questionnaire surveys, or consultation events begin with professional knowledge. This is used to design the questionnaires, or set the tone of focus groups. This pre-existing knowledge, presented in various and sometimes subtle forms then requires a response from the target community. The tone of the consultation is, therefore, already set with the professional knowledge leading. It is necessary to counteract this by encouraging the exploration of individual and collective community perspectives before they are defined and assumed into professional agendas (Johnson, 2009) and without undue influence from those who have most power (usually professionals, experts or heroic leaders), even when those who have most power to define knowledge act in facilitative way (Hutton et al, 2003).

Clearly, professionals do have a legitimate perspective and often have critical expertise. An appropriate opportunity must be created to allow these perspectives to shape the work and to foster mutual understanding. In some cases this may require that the community are offered the chance to explore their own learning in a challenging but supportive environment. This enables community members to critique and practice articulating their needs before they share their understanding with professionals. Ideally community perspectives are further developed through ongoing and supportive dialogue with service and intervention providers, statutory agencies and others at later stages in the community engagement process. The key principle here is that local community knowledge is privileged – it sets the agenda.

2.4. Address the deficit of experience and generate aspiration

Good community engagement recognises the deficit of experience among many people in understanding and analysing need and in developing ideas for service improvement and intervention design. This is particularly relevant in underprivileged areas. Insensitive or ill-conceived consultations and needs assessment often leads to impoverished responses which relate only a community’s current experience of services and interventions and current capacity to imagine how these might be different, the opportunity to develop new ideas and creative solutions is thus frequently lost.

Traditional methods of consultation such as focus groups, questionnaire surveys, or consultation events begin with professional knowledge. This is used to design the questionnaires, or set the tone of the focus group. This pre-existing knowledge, presented in various and sometimes subtle forms then requires a response from the target community. The tone of the consultation is, therefore, already set with the professional knowledge leading.

Consultations which typically ask for a response to proposals or ideas, for example: “what do you think about homework support classes?”, or which ask people what they need; for example: “what activities do you want in the community room of the children’s centre”, will typically only get a response based on what people already know has been delivered elsewhere, rather than what they believe would really work. Unless the deficit of experience is explicitly recognised and addressed, then the community engagement process may fail to surface the “unheard”, and fail to bring into play the community’s expert knowledge of the nature and dynamic of its own needs, and its creativity in generating ways to meet these. The end result is services and interventions which are suboptimal in terms of relevance, accessibility and effectiveness.

It is therefore important to create an environment and processes for engagement which not only value the current knowledge and experience of participants but also raises their levels of aspiration and knowledge. Raising aspiration is a fundamental aspect of empowerment where relevant alternatives and novel approaches are shared with the target community to expand, challenge and support their current level of understanding (Mills, 2005). Incorporating an aspirational element broadens the thinking of the group and sparks a greater potential for generating creative insights and solutions. The outcome of such a community engagement process is then informed, aspirational and change focused.

2.5. Utilise a Dual Task approach

In any context where engagement of end users is a core task there is the opportunity to generate a range of integrated outcomes in addition to the primary outcome. These core tasks include, inter alia, needs assessments, consultations, designing and building community facilities, and development or redesign of service and intervention delivery. This is the Dual Task approach (Trimble, 2006) where processes are put in place to build the capacity of the community to participate in design and delivery of the core task as it is being delivered. This approach offers additional integrated outcomes for all those who participate as exemplified in White (2006) who describes an arts based participation fused with health promotion and community capacity building. Dual task outcomes might, for example, include personal development for community members or training and employment in the delivery of services interventions; thus maximising sustainable benefits for all involved.

2.6. Work with Whole Systems

A whole systems approach considers the interrelations among what is considered a living system. In this case a whole community, including the social, physical, economic and cultural environment, and the residents, service providers, strategic policy makers and businesses who are the actors within it. A whole systems approach does not focus on specific units or a specific outcome. Instead, it creates an environment for new thinking and ideas to emerge from interrelated components intelligently adapting together (Pratt, Gorden and Prampling, 1999). A whole systems approach encourages creativity and learning among its participants, using collaborative methods which place equal value on all knowledge and offer a vehicle for engaging diverse groups of people in a way which develops shared understanding of the issues and builds collective (rather than individual) knowledge. For instance, within an appreciative inquiry, the process relies on conversation and stories from personal experience to understand what principles were driving successful work in the community. These principles can then be brought together to build a picture of what actions, beliefs and drivers support and maintain the community when it is working well.

3. Overview of the Community Engagement Model

In order to operationalise the 6 principles elaborated above, the Well London community engagement team (CET) needed to build collaborative relationships with the communities in each of the Well London (WL) target areas within 20 London boroughs, and in doing this the team had to ensure that the so called ‘hard-to-reach’ could be included in the process. The team needed to “privilege” the knowledge of the target communities thus allowing these communities to set the agenda without pressure from professional service providers or elected politicians. Recognising the deficit of experience and opportunity of many people in the target areas, all of which fall within the most deprived 11% of LSOAs in London, the WLCEP needed to include work to raise aspirations. To maximise additional benefit and learning to participants – the Dual Task - the CET needed to involve community members in a range of activities involved in making the World Cafés a success.

The CET therefore developed a comprehensive community engagement process based on the principles described above and other practical considerations to engage residents in each of the 20 WL target communities in two staggered six month phases in 2008.

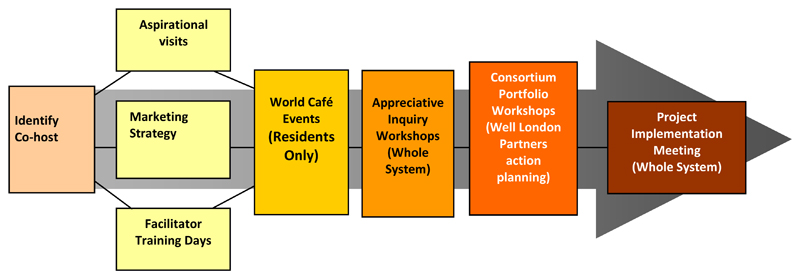

As illustrated in Figure 1, the community engagement model began by identifying and building relationships with a local community organisation (Co-host) in each LSOA. Co-hosts’ personnel attended facilitator training and aspirational visits and worked in partnership with the CET to develop a strategy to market WL and the WLCEP. Two Community Cafés were designed and delivered in each LSOA. These were for residents only, and other statutory and voluntary sector stakeholders were deliberately not invited to the Cafés in order to privilege communities’ knowledge and analytic frameworks in setting the agenda for the rest of the process. Findings from the Cafés were summarised in a written report which also incorporated summaries of routine health and socio-economic statistics and a description and mapping of relevant local services and amenities, both of which had been carried out by the CET in a separate work stream. This report was printed and distributed to local statutory sector stakeholders (Local Authorities and Primary Care Trusts), voluntary and community sector organisations, service providers and residents who had indicated a desire to be included in the next stage of the process. The report formed the point of departure for the next stage of the process: the Appreciative Inquiry Workshop (AIW).

Figure 1. Overview of the Well London Community Engagement Process.

In each LSOA, these organisations and residents were invited to an AIW which brought all stakeholders together. At this workshop, the findings from the Cafés were presented, principles and priorities for intervention were identified using the appreciative inquiry approach. Discussions were carefully recorded and summarised and a final report integrating these AIW findings with Café findings and service and amenity maps was prepared.

When all AIWs were complete, and integrated reports had been prepared, a two day-long action planning event involving all the WL partners was held. This used the integrated reports as a basis for setting priorities and intervention plans for each LSOA and to negotiate resource allocations across all LSOAs. Finally, Project Implementation Meetings were held in each LSOA with all stakeholders. These were events in each LSOA to feed-back and refine priorities and intervention plans. Afterwards a Project Implementation Document, setting out the priorities and plans and specifying the first year’s activities was distributed.

4. Designing and Delivering the Community Café Events

As described above the Community Café events were the first open community activities of the WLCEP and used the World Café method. As noted these events were for local residents in order to ensure that the knowledge and perspective of local people was foregrounded at the start of the process and that voices which are often not heard had an opportunity to be expressed without influence from others.

World Café events host informal, relaxed conversations about questions which participants identify as really mattering. The method is based on the realisation that the best ideas and solutions often emerge, not from formal processes but from informal ones; such as coffee breaks, over dinner, at the photocopying machine and so on. Café conversations aim to recreate such informal environments within which a structured conversation focused on one key question can take place. The participants are allowed to set their own direction in response to the main café question, therefore no perspective is privileged over any others. Cafés thus build a collective network of authentic knowledge amongst the participant community (Brown and Isaacs, 2005).

In what follows we consider how the underlying of principles and values of good community engagement facilitated the design and delivery of the WLCEP Community Café events.

4.1. Engage a co-host – building a collaborative relationship

WL identified potential co-hosts to ensure a partnership approach to delivery. This collaboration also enabled WL to build on what was already happening on the ground rather than duplicating it. Local stakeholders suggested possible organisations as co-hosts, and these were invited to apply for the role, which was to help facilitate the delivery of the WLCEP in their area. Co-hosts were paid, were given a guide book and were able to contact WL partners throughout the process for guidance and support. The co-host’s role was crucial in ensuring high turn-outs to and smooth running of the actual events. Where co-hosts had deep knowledge of and contacts in the target community, event attendance was stronger, and conversely where connections to the area were weaker, the corresponding participant numbers proved smaller. The lesson here is to ensure the right co-host is selected.

4.2. Marketing – finding the unheard voices

Co-hosts were asked to organise the marketing of the WLCEP events. A Mental Well-being Impact Assessment (Cooke and Stansfield, 2009) was carried out on WLCEP plans and this particularly identified the need to ensure inclusion of every section of the community. Thus the target communities were segmented by, for instance, age, gender, ethnicity, and physical and mental disability. The CET worked with co-hosts to develop an appropriate marketing strategy for each identified segment of the community.

Marketing included multiple methods including word of mouth, street interviews, advertising through local organisations and newsletters, area specific leaflets and posters, and multiple direct mailing close to the event dates. Leaflets were translated into ten of the top spoken community languages throughout the WL areas, as identified by the co-hosts, and incentives (or rather actions to remove barriers) to participation included free crèches, food and translators. The CET also used on the day opportunist marketing by speaking to people in the streets and outside schools to encourage them to come into the café.

4.3. The Dual Task Approach

As part of the dual task approach, WL invited all co-hosts to learn new skills and build networks of learning across the pan-London project. A Co-host introduction day was held at the start of the project to bring the whole WL team together. This event offered opportunities for long term networking and learning. Co-hosts, other known local organisations, and residents were also invited to attend training sessions in World Café facilitation, which was led by experienced facilitator Allison Trimble. This training is expensive and rarely offered outside of the private sector. As a result, WL was able to leave a legacy of group facilitation skills and whole-systems learning within each community. After completion of the training, co-hosts were invited to gain experience by co-facilitating the café events in their areas, though only a few of the more experienced co-hosts took this offer up. Further, residents were engaged in the marketing process, in providing food and crèche facilities or to act as translators or scribes at the café events.

4.4. Aspirational Visits – addressing the Deficit of Experience

The CET’s original plan to take residents on visits to sites of good practice, especially around health, wellbeing and community development practice, proved expensive and impractical. A visit was arranged to Bromley-by-Bow but was poorly attended. Building relationships in the LSOAs was still nascent and organising and gathering participants from across London proved too huge a task. Instead, acknowledging the deficit of experience, the CET brought the aspiration to the community. Good practice examples and stories were gathered from Well London partners and were designed into an exhibition as part of the community café events (see 5. below).

4.5. Designing and setting up the community cafés – bringing all the principles in practice

Achieving high levels of attendance at the cafés required a strong collaborative effort by the CET and the co-host. To begin with, the Community Cafés needed to take place in local venues. These venues needed to be known, welcoming, accessible and acceptable to all the community. We tried to avoid venues with religious affiliations, and those that were inaccessible to physically disabled members of the community. This wasn’t always possible. In several areas, venues that met all our criteria were impossible to identify. The least successful were those some distance from the target community. Venues came in all sorts of shapes, sizes and states of disrepair. Many were old dank community centres that had seen better days, and in order to follow the advice of creating a comfortable ambience3, the CET engaged Uscreates4, a social design agency, to create a back drop exhibition illustrating WL themes, good practice stories and visuals. The exhibition was designed to be easy to set up, striking and flexible in a number of settings. The large but light boards used, easily joined together, and transformed otherwise drab settings. The exhibition included interactive games, blackboards for comments, a space for videos, and a laptop mapping exercise, staffed by one of the team, where individuals could make comments about specific geographic locations. Welcome boards were placed outside the venue and at the entrance to the café to direct people.

Tables were set up in a higgledy-piggledy café style around the spaces, with 6 chairs around each table. The tables were dressed with colourful table cloths, covered themselves with paper table clothes to write on, coloured marker pens, flowers and electric candles, and a menu of café “etiquette” rules. Plentiful healthy hot and cold food and drinks were provided at all cafés, taking care to provide a variety of cultural styles, including Halal and vegetarian options. The food and refreshments were available throughout the cafés, and participants could help themselves as they pleased. This was a key element to helping participants feel relaxed and wanting to continue in conversations. Gentle ambient music was played throughout. Residents often expressed pleasant surprise when they entered the transformed environment and readily got involved.

Wherever possible a separate crèche area with local crèche assistants was provided. Where this was not possible an area of the café space was screened off for children. In one instance, so many children arrived that the crèche was soon full, and children overflowed into the main café area and “ran free”. This added to the social atmosphere and emphasised the need for flexibility. Where necessary, local interpreters were also invited to translate contemporaneously. In one example, a translator for a group of Eritrean women had a direct conversation with a translator for a group of Somali women thus joining the two groups in dialogue.

Cafés lasted around two hours and delivered four rounds of discussion. Round one posed the key question. Round two posed the same question but mixed table participants. Round three was an open plenary round where the facilitator asked questions to each table and provoked an open discussion. Round 4 returned to round table discussions to set priorities for actions. In some cases, residents trickled in over extended periods and it was impossible to have a “pure” café. In these instances, the CET got tables going and then added new tables as additional residents arrived. In some cases, the team had to run facilitated tables similar to focus groups.

The construction of the main question asked was key to the success of the discussions and to getting useful data to carry forward to the remainder of the WLCEP. Much thought was put into crafting an appropriate question. The final question decided on was “what do you understand as the health needs of your community?” The presentation of such an open ended question allowed participants a great deal of scope to surface their own theories and knowledge. In almost all Cafés, participants quickly linked health to issues of community cohesion, the physical environment, community safety, youth and others, driving conversations which truly addressed the whole system.

4.6. Record, Analyse and Report – Discover what is unknown

Scribes were present at each table to record the discussions. Scribes were provided by the co-host from local residents or members of staff, and from Well London partners. They were trained before the event. Scribes were encouraged to avoid directing discussions, although in some instances questions were asked to get participants to elaborate on a particular point or to encourage everyone at the table to contribute. Apart from this scribes didn’t take part but concentrated on recording everything that was said. Each line of recorded conversation was typed up electronically and numbered by the scribe. Raw data, carefully anonymised, was later included in appendices to reports so that recipients could trace back the origins of the interpreted findings, using the line numbering system, and this ensured transparency throughout.

The data from the street interviews and community cafés were analysed thematically within each LSOA in two stages. First, a pre-determined coding framework was applied to the textual data. This organised text into several categories according to its content pertaining to Well London themes: ‘healthy eating’, ‘physical activity’, ‘mental wellbeing’, ‘arts and culture’, ‘open space’, ‘cross cutting themes’ and ‘miscellaneous’. Using the Well London themes as an analysis framework allowed us to collate and compare the data across all twenty areas. New categories emerging during analysis included ‘community building’, ‘safety’, ‘communication’ and ‘youth’; again reflecting the natural tendency of people to understand how health is located in a whole system context (Adams-Eaton et al, 2010). To ensure coherence and consistency, the coding was reviewed by a second researcher and any disagreements were discussed and data re-coded as necessary.

Second, text coded under each theme was combined across all LSOAs. From this a narrative was written under each heading with tracked references back to original raw data. The narrative was added to existing mapping data to form a report for the next stage of the WLCEP, the Appreciative Inquiry Workshops, and the key findings were presented verbally at the start of each workshop. Thus data and priorities generated first from the residents were privileged and used to set the agenda for the following stages of the WLCEP, and could be tracked up to the final plans for intervention.

5. Overview of participation and learning

Forty Community Cafés were held across the twenty boroughs. Cafés averaged around 46 residents, ranging between 25 and 99 adults in attendance. In all, including street interviews used during the marketing phase, almost 1400 residents or circa 5% of all adults in the target LSOAs were engaged. Observations from research staff noted a broad range of demographic characteristics among the participants with an over-representation amongst women, less youth and older men.

Residents tended to remain throughout the Café process, and expressed pleasure at the chance to socialise, chat and eat with neighbours at the same time as conducting a useful exercise. Some residents asked “if they could have more of these”. The data collected from these events were, as discussed above, analysed and fed back to the communities throughout the process.

As well as identifying key perceived proximal barriers to healthy eating, physical activity and mental well being such as cost or lack of understanding, the most significant findings from the Cafés across all WL target areas was the view that a lack of community spirit and cohesion had a strong negative effect on residents’ feelings of mental and physical wellbeing. Residents felt that their communities were fragmented across age and cultural lines, and between established residents and newcomers. There was a lack of communication, a gap in knowledge about what was going on, a lack of coordination between services, and a strong perception of lack of safety, particularly attributed to the anti-social behaviour of youth, who were perceived as having “nothing to do” (Bertotti et al, 2010). In short, residents expressed a desire to live in a community of which they felt part of and safe in. Residents welcomed the opportunities to take part in projects such as healthy eating, physical activities or arts as a way of bringing the community together across inter-generational and inter-cultural lines, and getting to know their neighbours better. The purpose of this paper is not to discuss the findings of the Community Cafés or overall WLCEP. But it is important to note that these were key in shaping intervention delivery and in bring together themes to make projects relevant and attractive on the ground. The WLCEP revealed a deeper understanding of how the interrelationship of the physical and social environment that the residents inhabited acted as barriers to health. This knowledge continues to be invaluable in building the WL project across all twenty LSOAs. Residents naturally understand health within a whole systems context and are able to describe in detail how that whole system works.

6. Conclusion

The WL programme has set out to promote healthier lifestyles among some of London’s poorest neighbourhoods through an intervention programme tailored to the needs and assets of each LSOA. In order to understand those needs and assets in a way that was to be truly effective in terms of community buy-in, it was necessary to design an inclusive and transparent community engagement process.

The CET used knowledge and experience from pathfinder organisations to identify principles that were essential to observe when engaging with communities. These included: building collaborative relationships with the community based on trust in order to hear and record the unheard; privileging the communities’ knowledge and experience to address the power imbalance in agenda setting, analysis and intervention design; building capacity to participate and raising aspiration; using methods that allowed the widest range of community voices to be heard; and adding legacy skills and resident involvement in the process itself. Further, to enhance trust and to ensure that the community voices were genuinely heard, the CET added the principles of transparency and inclusiveness as clear design criteria. The communities themselves drove an analysis within the context of the whole system without prompting from the team.

The CET worked to apply these principles to the WLCEP throughout, and, in particular to the Community Cafés, which formed the first open community activities of the WLCEP, and included the design of its marketing strategies.

Evidence of the success, although not perfect, is shown by the large numbers engaged compared with normal community events and subsequent numbers who have participated in the planned programmes, devised largely from knowledge surfaced from the WLCEP, where the Well London Alliance has more than met its planned targets.

Challenges included the expense of aspirational visits, the choice of the wrong Co-hosts and difficulty in finding appropriate venues in a few areas, the failure to engage some sections of the community, and some Café events having people trickling in and out, which prevented delivery of the ideal Café process. The first challenge was overcome by bringing the aspirational stories to the community through the design of the café back-drop exhibition. The second challenge taught the team how essential it was to find the right co-host and not always accept the first offer. Co-hosts must have genuine connections with their area. Perfect venues are not always possible to get for a host of reasons but the closer and more comfortable to the community the better the result. Certain sections of the community take more time to engage. In WL community engagement is ongoing and a community development approach is used throughout, and further efforts have been made in later stages to engage with those who may have initially been left out. The final challenge was overcome by remaining flexible with the team adapting its engagement style to circumstances.

The Community Cafés provided a safe and informal space for groups of residents to challenge and learn from each other, providing a communication environment that rarely exists in the everyday world. It was a space where people could move beyond their normal complaints to talk about what they really cared about without a fixed structure. This in turn enabled deep rooted issues to be surfaced and understood which in turn contributed to effective planning and intervention design.

The wider determinants of health and wellbeing are now understood to represent a dynamic arrangement of interrelated environmental, social and structural barriers and facilitators. Consequently, working in isolation to tackle a single health or wellbeing issue may not be the most effective approach. WL seeks to address, at the same time, the areas of physical activity, healthy eating and mental health and wellbeing by influencing the system of determinants and their interactions which are common across these areas. In order to understand this system, partnership, interdisciplinary and joined-up working across planning and delivery agencies and communities is required. A prerequisite of this approach is that everyone serves as equal and valued contributors.

Truly participative and transparent community engagement can, as in the example of Well London, bring significant improvements in health interventions and wider benefits to communities by supporting the development of unrecognised community assets. This can unleash communities’ energy and capacity to help themselves, dramatically reducing the burden for the original delivery organisation and therefore efficiency. Thus high quality, innovative and transparent community engagement is a critical task, if current health services are to adapt to the changing financial climate, rather than an optional add-on. As our understanding of health and well-being and their determinants continues to evolve, we suggest that the methods of engaging the community need to evolve alongside.

Footnotes

Allison Trimble was a founding member of the Bromley-by-Bow Centre team and worked with a group of local residents and members of the community care group to develop the distinctive model of participation which underpins the Centre’s approach to community engagement.. Allison worked as CEO of the Centre and developed this model of local engagement to inform participatory management and inclusive leadership development processes. She now works with Leading Room, a cross sector and leadership development organisation specialising in work with public and community based leaders.

References

- Adams-Eaton F, Bertotti M, Sheridan K, Renton A, Harden A. Promoting health in deprived communities: learning from residents’ views and experiences using a world café methodology. Institute for Health and Human Development; London: 2010. IHHD Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari W, Phillips C, Zwi A. Narrowing the gap between academic professional wisdom and community lay knowledge: perceptions from partnerships. Public Health. 2002;116:151–159. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertotti M, Adams-Eaton F, Sheridan K, Renton A. Key barriers to community cohesion: views from residents of 20 London deprived neighbourhoods. GeoJournal. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10708-009-9326-1. Online version available at [ http://www.springerlink.com/content/223l23w77j87um7r/] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Isaacs D. The World Café: Shaping Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter. San Francisco: Berrett Koehler; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Conservative. [accessed 21st November 2010];David Cameron: The Big Society. 2009 available at http://www.conservatives.com/News/Speeches/2009/11/David_Cameron_The_Big_Society.aspx. speech from Rt Hon David Cameron, Tuesday, November 10th 2009.

- Cooke A, Stansfield J. Improving Mental Well-being Through Impact Assessment: A summary of the development and application of a Mental Well-being Impact Assessment Tool. National Mental Health Development Unit. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Cooperrider D, Srivastva S. Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. In: Pasmore WA, Woodman RW, editors. Research in organizational change and development. Vol. 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1987. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cropper S, Porter A, Williams G, Carlisle S, Moore R, O’Neill M, Roberts C, Snooks H. Community Health and Wellbeing. Action Research on Health Inequalities. Policy Press; UK: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007. London: Department for Communities and Local Government; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton W, Fillingham D, Attwood M, Pedlar M, Wilkinson D. Leading Change: A Guide to Whole Systems Working. Policy Press; UK: 2003. [Illustrated] [Paperback] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PA. And the survey says: The case for Community Engagement. Journal of cases in Educational Leadership. 2009;12(3):9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Levy S, Baldyga W, Jurkowski J. Developing Community Health Promotion Interventions: Selecting partners and fostering collaboration. Health Promotion Practice. 2003;4:314–322. doi: 10.1177/1524839903004003016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills R. Sustainable Community Change. A New paradigm for Leadership in Community Revitalization Efforts. National Civic Review. 2005;94(11):9–16. [Google Scholar]

- NICE. NICE public health guidance 9: Community engagement to improve health. NHS National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt K, Gordon P, Plamping D, Wheatley MJ. Working Whole Systems: Putting Theory into Practice in Organisations. Radcliffe; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens A, Rafferty J, editors. Health care needs assessment. 2nd ed. 1 and 2. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Trimble A. Well London Alliance Guide To Community Engagement Process. Unpublished, Leading Room; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- White M. Establishing common ground in community-based arts in health. The Journal of the Royal Society for the promotion of Health. 2006;126(3):128–133. doi: 10.1177/1466424006064302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall M, Hayes R, Moore D, Petticrew M, Clow A, Schmidt E, Draper A, Lock K, Lynch R, Renton A. Evaluation of community level interventions to address social and structural determinants of health: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC. Public Health. 2009;9:207. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]