Abstract

Loss of Survival Motor Neuron-1 (SMN1) causes Spinal Muscular Atrophy, a devastating neurodegenerative disease. SMN2 is a nearly identical copy gene; however SMN2 cannot prevent disease development in the absence of SMN1 since the majority of SMN2-derived transcripts are alternatively spliced, encoding a truncated, unstable protein lacking exon 7. Nevertheless, SMN2 retains the ability to produce low levels of functional protein. Previously we have described a splice-switching Morpholino antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) sequence that targets a potent intronic repressor, Element1 (E1), located upstream of SMN2 exon 7. In this study, we have assessed a novel panel of Morpholino ASOs with the goal of optimizing E1 ASO activity. Screening for efficacy in the SMNΔ7 mouse model, a single ASO variant was more active in vivo compared with the original E1MO-ASO. Sequence variant eleven (E1MOv11) consistently showed greater efficacy by increasing the lifespan of severe Spinal Muscular Atrophy mice after a single intracerebroventricular injection in the central nervous system, exhibited a strong dose-response across an order of magnitude, and demonstrated excellent target engagement by partially reversing the pathogenic SMN2 splicing event. We conclude that Morpholino modified ASOs are effective in modifying SMN2 splicing and have the potential for future Spinal Muscular Atrophy clinical applications.

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is the most common inherited motor neuron disease and occurs in ~1:11,000 live births with a carrier frequency of ~1 in 40 worldwide.1 SMA is an autosomal recessive disorder and it is a leading genetic cause of infantile death. The gene responsible for SMA is called survival motor neuron-1 (SMN1). A nearly identical human-specific copy gene called SMN2 is present on the same region of chromosome 5q. Mutations in SMN2 have no clinical consequence if SMN1 is retained. However, SMN2 cannot prevent disease development in the absence of SMN1 because ~90% of SMN2-derived transcripts are alternatively spliced, resulting in a truncated and unstable protein lacking the final coding exon (exon 7). This splicing anomaly is the result of a silent C to T nucleotide mutation within exon 7.2,3 While a handful of nucleotide differences are present between SMN1 and SMN2, none of the SMN2 differences alter the coding capacity; hence, the small amount of full-length SMN protein that is produced from SMN2 is fully functional and otherwise indistinguishable from the full-length protein produced from SMN1. Due to the ability to encode fully functional SMN protein, strategies to increase SMN2-derived full-length SMN expression have accelerated translational studies and are the focus of several ongoing clinical trials.

Accurate SMN exon 7 pre-mRNA splicing is achieved through a complex interplay between positively and negatively acting regulatory factors.4 Several regulatory elements playing an important role in modulation of the alternative splicing of exon 7 have been described in the context of the SMN2 gene including element 1 (E1); intronic splice silencer N1; the SF2/ASF, Tra2-β1 and hnRNP-A1 binding sites within exon 7; and the intronic hnRNP-A1 binding sites.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 From a biological perspective, these elements are critical to understanding how SMN pre-mRNA splicing leads to disease development. From a therapeutic perspective, many of these regulatory elements have the potential to serve as potent therapeutic targets of small molecules or ASOs. Various ASO designs with distinct chemical backbone modifications have been validated in vitro and in vivo.7,14,15,16,17,18 Factors affecting the binding efficiency of ASOs to the target include the specific targeted motifs, the sequence length, base composition and the ASO's chemical backbone.

Targeting SMN2 will likely prove to be an important therapeutic opportunity for SMA patients. Several intronic regulatory elements that prevent SMN2 exon 7 inclusion have been previously investigated,2,5,6,8,10,19,20,21,22 and the most promising targets have been negative regulators of exon 7 inclusion found within introns flanking exon 7: intron 6 and E1; and intron 7 and intronic splice silencer-N1. ASOs can modify pre-mRNA splicing by functionally inhibiting intronic splicing regulatory elements such as E1 or intronic splice silencer-N1, or by inducing exon-skipping by sterically inhibiting the formation of critical splicing factors. ASOs have great potential for treating a broad range of genetic diseases and have shown some promising results in clinical trials to enhance exon skipping in Duchenne muscular dystrophy.23,24 Alternatively, ASOs can target binding sites for splicing repressors.8 This ASO function has been utilized by Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Biogen Idec in the development of their ASO, Nusinersen (formerly known as IONS-SMNRx), which is now in several ongoing clinical trials including two phase 3 clinical trials for SMA.15,25

Previously, we have targeted E1 by designing a Morpholino-based ASO (E1MO). E1MO was comprised of a sequence annealing to two separate regions flanking E1 on the SMN2 pre-mRNA. E1MO significantly extended survival in two important animal models of disease: the severe SMN▵7 mouse; and an intermediate model SMNRT.26 In this study, we have investigated the efficiency of a novel panel of E1-targeting Morpholino ASOs to identify an optimized sequence composition. The new variants were administered via a single intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection into SMN▵7 SMA model mice on postnatal day 1. In severe SMA mice, the lead candidate dramatically extended survival and exhibited a potent dose-response. Additionally, the lead candidate functioned effectively in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived SMA motor neurons and corrected the aberrant splicing of SMN2 at the pre-mRNA level. The current work identifies a lead ASO candidate that targets more efficiently the E1 region of the SMN2 pre-mRNA.

Results

Identification of a Morpholino antisense oligonucleotide lead candidate: E1MOv11

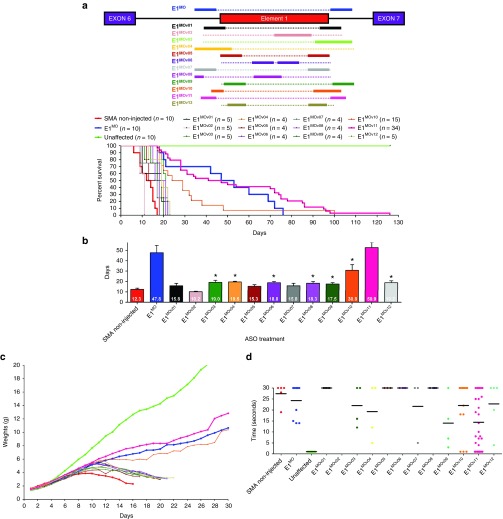

E1 is an intronic repressor motif of ~45 nucleotides in length, located upstream from exon 7. Previously, we developed a single antisense sequence and examined its efficacy in a variety of SMA contexts, demonstrating a significant extension in survival. However, additional sequences were not analyzed and the initial ASO responded poorly in a dose-response curve outside the initial concentration. To advance the Morpholino-based E1 ASO, a novel panel of 12 E1-targeting ASOs was developed. The initial ASO called E1MO, was a single continuous sequence comprised of two distinct annealing regions that flanked E1 ((Region A (65-51) and Region B (130-118)). The new ASOs, designated as E1MOv01 through E1MOv12, vary in length and anneal to regions in and around Element 1 (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Designing and identification of lead ASO variants targeting the intronic repressor Element1. (a) Schematic representation of the design of various Morpholino-modified ASO targeting the intronic repressor Element1 (E1MOv01 through E1MOv12ASO). The design of the previously published E1MO is illustrated above the E1 repressor region (blue). (b) Severe SMNΔ7 mice showed a range of longevity after injections with various E1MO oligonucleotides. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed from the various treatment groups following ICV delivery on P1 of each ASO (2 µl of a 40 nmol/l solution). Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) statistics were applied for comparisons between lead candidates (E1MOv10 and E1MOv11) where P < 0.0001 compared with SMA noninjected animals (top). Bar graph showing the mean survival for each treatment group where (*) indicates P < 0.05 (bottom). (c) Weight gain of SMNΔ7 mice injected with ASO variants (E1MOv01 – E1MOv12). Total body weight was measured daily for all animal groups postinjection. (d) Scatter plot of time-to-right (TTR) performance of mice injected with all the E1MO variants. A late-stage in disease progression, TTR values are shown for P12. ASO, antisense oligonucleotide; ICV, intracerebroventricular; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMN, survival motor neuron.

To assess the potential for phenotypic improvement and efficacy of the novel E1-targeting ASOs, severe SMA mice were treated at P1 with a single dose delivered via ICV injection. The SMA mice used in this study are the “SMN▵7” (SMNΔ7+/+; SMN2+/+; Smn–/–) model and, importantly, they express the human SMN2 gene. Using a standard “low dose” established during the characterization of the original E1MO and consistent with the low dose previously published16,26; 2 µl of a 40 nanomolar solution was delivered via an ICV injection. E1MOv02 was detrimental and decreased survival, while many of the new ASOs modestly extended survival compared with untreated SMA animals. However, E1MOv10 and E1MOv11 significantly outperformed the other novel variants (Figure 1b, Supplementary Figure S1). In particular, E1MOv11 treatment resulted in SMN▵7 mice that lived >120 days from a single ICV injection on P1. While the averages are similar between E1MO and E1MOv11, the longest lived animal was 82 days. In contrast, ~25% of E1MOv11 treated animals lived longer than 80 days (Figure 1b). Consistent with the life span data, ASO-treated mice exhibited a similar improvement in weight gain, with E1MOv10 and E1MOv11 resulting in the greatest weight gain among the new variants (Figure 1c). To analyze the impact on gross motor function following ASO administration, time-to-right assays were performed in which SMA mice are placed on their backs and the time to assume a prone position is recorded. In the graphical representation, a lower score indicates a faster time-to-right, demonstrating that untreated SMA mice are extremely weak and have difficulty righting themselves. In contrast, E1MOv10 and E1MOv11 treated animals were able to right significantly faster than the other treatment groups on P11 (Figure 1d).

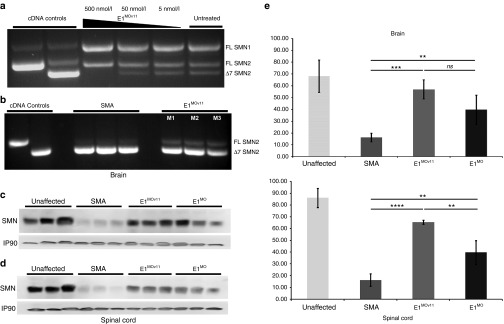

Based upon the aggregate of in vivo data, E1MOv11was selected as the lead candidate. Going forward, the further characterization and analysis focused upon E1MOv11. To examine the degree of molecular target engagement, human embryonic kidney (HEK)293T cells were transiently transfected with a range of E1MOv11 (500, 50, and 5 nmol/l) (Figure 2a). At the highest concentration, SMN▵7 mRNA is not detectable, while a robust full-length SMN mRNA product is observed. In the more complex in vivo context, SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing was examined following administration of a single dose of E1MOv11 (2 µl of a 100 nmol solution) via an ICV injection to SMN▵7 mice at P1. Consistent with the cell-based results, albeit to a lesser degree, E1MOv11 increased full-length expression with a concomitant decrease in the exon-skipping event (Figure 2b). Importantly, the increase in full-length SMN mRNA resulted in a significant increase in SMN protein in brain and spinal cord extracts derived from E1MOv11-treated animals when analyzed at P7 (Figure 2c,d). Quantitation of the SMN protein levels demonstrated that a significant increase was observed in the spinal cord of E1MOv11-treated animals compared with untreated as well as the original E1MO ASO (Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

Increase in full-length SMN transcript and SMN protein levels after E1MOv11 treatment. (a) RT-PCR image of endogenous SMN1/2-derived transcripts from HEK293T cells and (b) in spinal cord tissues from three SMNΔ7 mice. SMN2 and SMN1 transcripts are clearly distinguishable after reaction products of the cell culture extracts were digested with restriction enzyme DdeI. Plasmids containing the full-length or SMN▵7 products, pCI-▵7 and pCI-FL, respectively, were used in PCR reactions to generate size standards. Injection of the E1MOv11 variant targeting the Element1 repressor increases total SMN protein in brain (c) and spinal cord (d) tissues of SMNΔ7 mouse model. Western blots (n = 5) for each treatment group were performed on tissues harvested at P7. (e) Western blot quantification. Western blot (n = 3) from brain and spinal cord tissue of five (5) ICV injected animals with E1MO and E1MOv11. Bar graph showing significant percent increase in SMN protein induction compared to the non-injected SMA control group. Significance was calculated using Student's t-test, where ns = nonsignificance, ****P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; ICV, intracerebroventricular; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMN, survival motor neuron; HEK, human embryonic kidney.

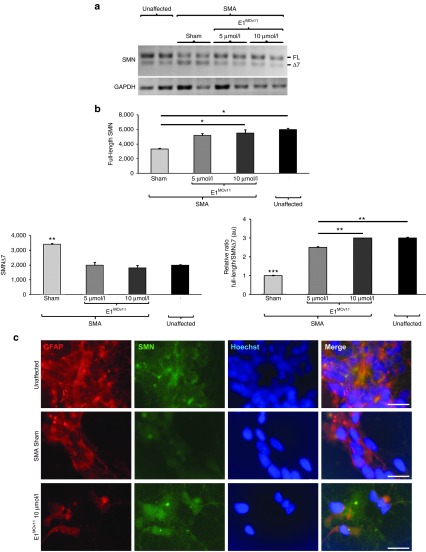

To determine the efficacy of E1MOv11 in an isolated disease relevant tissue, iPSCs derived motor neuron cultures were transiently transfected with E1MOv11. iPSC cultures are not as efficiently transfected compared with HEK293 cells, therefore, higher concentrations of E1MOv11 were used. Two doses of E1MOv11 were transfected into the cultures, resulting in a significant increase in full-length SMN mRNA expression and a concomitant decrease in SMN▵7 mRNA (Figure 3a,b). When examined by immunofluorescence using an anti-SMN antibody, iPSC motor neuron cultures exhibited higher SMN staining than sham-transfected cultures (Figure 3c), consistent with the increase in full-length SMN mRNA.

Figure 3.

E1MOv11 transient transfection results in a significant improvement in full-length SMN expression in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derived motor neuron cultures. (a) An increase in full-length SMN transcript after E1MOv11 treatment as measured by RT-PCR. (b) Quantification full-length SMN transcripts from iPSC derived motor neurons. Two concentrations of E1MOv11 resulted in significant increase of full-length SMN mRNA expression and a decrease in SMN▵7 mRNA when compared with sham-transfected cultures. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001. (c) Representative images of iPSC derived motor neuron cultures. Astrocytes within the cultures were stained for GFAP (red). Cytoplasmic expression and nuclear localization of SMN (green) was increased with E1MOv11 treatment. Nuclei were labeled with Hoechst (blue). Scale bar = 10 μm. RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction; SMN, survival motor neuron; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein.

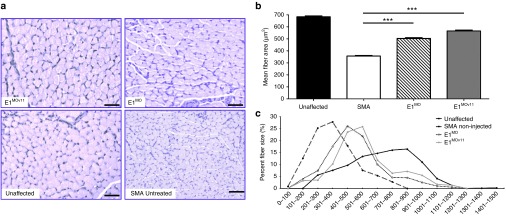

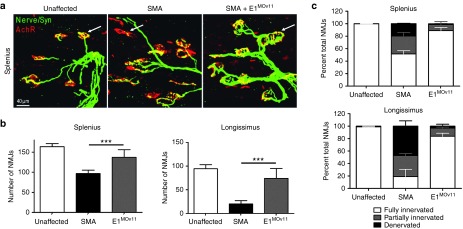

To examine the activity of the E1MOv11 in disease relevant tissue in vivo, the gastrocnemius was sectioned and stained (Figure 4a). Muscle pathology was improved in the ASO-treated samples, and when comparing E1MOv11 with the original E1MO ASO, the E1MOv11 further improved the average muscle fiber size (Figure 4b,c), approaching unaffected levels. In the SMN▵7 mice, a hallmark of disease is the pathology of the neuromuscular junctions (NMJs). To determine whether E1MOv11 administration improved the NMJ pathology from skeletal muscles that are particularly susceptible to SMN deficiency, the splenius capitis and the longissimus capitis were examined from unaffected mice as well as SMA mice with or without E1MOv11 treatment. NMJs from the splenius capitis and the longissimus capitis muscles of the untreated SMA mice were poorly developed and largely denervated, as evidenced by ~50% or 80% of the NMJs that were partially innervated or denervated (Figure 5a,b). In contrast, mice treated with E1MOv11 exhibited NMJs that were nearly fully restored and approaching unaffected levels as ~90% of NMJs in the same muscles were fully innervated (Figure 5a,b). In a comparison of the total number of NMJs present on each of the muscles, treatment with E1MOv11 significantly increased the number of NMJs above untreated SMA muscles (Figure 5c). While ASO treatment did not fully restore NMJ numbers to that of unaffected muscles, an increase of ~50 and 400% was observed between SMA and SMA treated with E1MOv11 (Figure 5c).

Figure 4.

Assessment of muscle pathology. (a) Representative pictures of gastrocnemius muscle cross-sections. Gastrocnemius muscles were dissected from P12 mice and cross-sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and analyzed by microscopy. (b) Mean fiber size was quantified using the Metamorph (Version 6.2r4) software. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (c) Muscle fiber distribution was analyzed for each group. Both E1MO and E1MOv11 had significantly fewer small fibers and significantly higher percent of larger fibers than the SMA noninjected controls. Significance was calculated using Student's t-test, where ***denotes P ≤ 0.001. SMA, spinal muscular atrophy.

Figure 5.

Improvement in neuromuscular junction (NMJ) pathology. The longissimus capitis (LC) and the splenius capitis (SC) muscles from ICV injected and control animals at P12 were immunostained for nerve terminals with antineurofilament/antisynaptophysin (Nerve/Syn) (in green) and motor endplates with α-bungarotoxin (in red). While the untreated SMNΔ7 mice displayed typical severe denervation, E1MOv11 treatment substantially restored NMJ's pretzel-like structures. (a) Selected high-magnification images of NMJs in splenius muscles of control and SMNΔ7 mice are shown. Arrows indicate occupied endplates in both treated and unaffected animals contrasting the empty endplate seen in untreated controls. (b) Quantification of the number of functional NMJs from LC and SC muscles from healthy unaffected mice, SMNΔ7 noninjected controls and E1MOv11-treated SMNΔ7 mice (n = 3 per group) where ∗∗∗indicates P ≤ 0.001). (c) Quantification of the percentage of fully and partially innervated NMJs in the LC and SC muscle groups (Unaffected n = 6; SMA noninjected n = 6; E1MOv11-treated n = 6). ICV, intracerebroventricular; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMN, survival motor neuron.

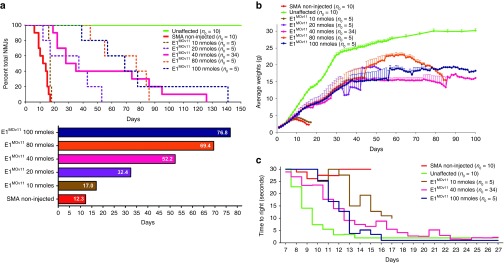

In the development of the original E1 ASO, a dose-response curve could not be established as only a single dose elicited a protective effect. To determine whether E1MOv11 responded in a drug-like manner by functioning over a range of concentrations, SMN▵7 mice were administered 2 µl of each of the following solutions of E1MOv11: 10, 20, 40, 80, and 100 nmol/l. Across the 10-fold dosing paradigm, average survival was increased consistent with an increase in the concentration of E1MOv11 (Figure 6a). While the lowest dose was only marginally effective compared with higher doses, it still resulted in ~50% increase in survival. With higher doses, life spans were improved to ~32, 52, 70, and 77 days, respectively (Figure 6a). There was a general dose-response trend in total body weight as higher E1MOv11 doses corresponded to higher body weight (Figure 6b); however, at any single point during development, many of these mice were statistically similar with respect to body weight. Similarly, while all E1MOv11 treatments resulted in faster time-to-right scores, the greatest improvement was observed with the highest dose of E1MOv11 (Figure 6c, Supplementary Figure S2). Collectively these results demonstrate that a novel lead candidate for E1-targeting Morpholino ASOs has been identified that displays important drug-like properties and significantly corrects all aspects of the severe SMA phenotype following a single ICV administration.

Figure 6.

Dose dependent phenotypic improvement of SMNΔ7 mice injected with E1MOv11. (a) The higher dose treated animals lived longer. All concentrations increased survival compared with the untreated mice. The Kaplan–Meier survival curve depicts the correlation between longevity and dose dependent E1MOv11 treatment (top). A bar graph showing the dose dependent increase in average survival of animals treated with E1MOv11 (bottom). Box within bar shows the average life span (days) per treatment group. (b) Significant increase in the average weight of SMNΔ7 animals after treatment with different concentrations of E1MOv11. (c) Time-to-right test results shows that SMNΔ7 mice treated with E1MOv11 at higher doses perform substantially better. Animals injected with suboptimal doses exhibit less muscle control and turn slower than mice injected with higher concentrations of E1MOv11(Two-way analysis of variance P = 0.0122 for lowest dose and noninjected SMA groups; P < 0.0001 for highest dose and noninjected SMA groups). SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; SMN, survival motor neuron.

Discussion

Recently, there has been significant progress in the development of therapeutic strategies for SMA, including clinical trials for AAV9-SMN gene therapy, small molecules that modulate SMN2 splicing, splice-switching ASOs that increase SMN2-derived full-length SMN, and neuroprotectants (NCT02633709; NCT02644668; NCT02122952; NCT02292537; NCT02386553; and NCT02268552). SMA is a multisystem disorder and the clinical spectrum is extremely broad, therefore, even though novel compounds are in the clinic, it is important to continue to push forward additional translational efforts that target distinct pathways that could be used individually or potentially as combinatorial therapeutics. To this end, we have designed and evaluated a panel of novel E1-targeting Morpholino ASOs, resulting in the identification of a lead candidate, E1MOv11. This compound enhances SMN full-length expression and significantly corrects the severe SMA phenotype in an important model of SMA. E1MOv11provides a distinct genetic target from ASOs that are currently in clinical trials as the sequence-specific target is the regulatory region E1. Additionally, it provides a means to push Morpholino-based chemistries closer to the clinic.

Interestingly, in the development of the original E1-targeting ASO, this molecule had an extremely narrow effective dose, as life span and splicing activity was largely undetectable at twofold up or down from the studied dose. One of the primary objectives in the analysis of the novel panel of E1-targeting ASOs was to identify a compound that demonstrated activity over a broad range of concentrations. Here we identified E1MOv11, which exhibits activity over an order of magnitude in dosage, and even at the highest concentrations tested, did not elicit any overt toxic effects. Going forward, it will be important to determine pharmacodynamic properties of the lead compound as well as potential impacts upon off-target genes through RNAseq analysis in E1MOv11-treated tissues.

In the screening of the 12 novel ASO variants, E1MOv10 and E1MOv11 resulted in the longest life span extensions, while the remaining ASOs extended survival by ~10–75%. However, not all of the ASOs resulted in extensions in survival, specifically E1MOv02, which resulted in premature death of the treated pups. At this time, it is unclear whether the sequence composition was toxic, or whether there were toxic off-targets effects related to gene expression patterns impacted by this ASO. Further follow-up will be required to identify the molecular interactions that ultimately lead to an effective E1 ASO or compounds with minimal activity and/or negative activity.

Regardless of the therapeutic, the temporal requirements for SMN remain an essential question in the field. Animal models have suggested that the earlier a therapeutic is delivered, the greater the phenotypic correct. This has been observed using gene therapy vectors, ASOs, small molecules, and genetically inducible models.27,28,29,30,31 To begin to address this from a clinical perspective, ongoing clinical trials from AveXis and Inonis/Biogen Idec are designed to investigate early or even presymptomatic delivery. Evidence for early administration in the clinic would provide further impetus for the inclusion of SMA on a universal newborn screening platform.

E1MOv11 has the potential to move toward the clinic as a stand-alone compound; however, it is also important to consider potential combinatorial therapeutics in which compounds target distinct SMA-related pathways. In these scenarios, there are two general approaches: (i) SMN-dependent strategies such as ASO-mediated E1 and intronic splice silencer-N1 inhibition; or (ii) SMN-dependent plus SMN-independent therapeutics, such as an ASO with a neuroprotectant, or an ASO with skeletal muscle activators. The likelihood that a single compound will address the multitude of symptoms and clinical forms of SMA is unfortunately low. Similarly, unexpected obstacles during clinical trials are an unfortunate reality, such as the clinical holds recently placed on two promising small molecules that modulate SMN2 exon 7 inclusion.32,33 While an enormous amount of promising translational and clinical work has been accomplished, it is essential to continue to press forward on the development of novel, effective therapeutics that address the breadth and complexity of SMA.

Materials and Methods

Animal procedures and ASO delivery. All animals were housed and treated in accordance with Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of the University of Missouri, Columbia, MO. The colony was maintained as heterozygote breeding pairs under specific pathogen free conditions. SMNΔ7 (SMNΔ7+/+;SMN2+/+;Smn–/–)34 were genotyped on the day of birth (P0) using standard polymerase chain reaction protocol (JAX Mice Resources) on tail tissue material. The following primer sets were used: for the mouse Smn gene, mSmn-WT forward (5′-tctgtgttcgtgcgtggtgacttt-3′) and mSmn-WT reverse (5′-cccaccacctaagaaagcctcaat-3′) and for the Smn knockout SMN1-KO forward (5′-ccaacttaatcgccttgcagcaca-3′) and SMN1-KO reverse (5′-aagcgagtggcaacatggaaatcg-3′). ICV injections were performed on P1, as previously described.35,36,37,38 Briefly, mice were immobilized via cryoanesthesia and injected using μl calibrated sterilized glass micropipettes. The injection site was ~0.25 mm lateral to the sagittal suture and 0.50–0.75 mm rostral to the neonatal coronary suture. The needles were inserted perpendicular to the skull surface using a fiber-optic light (Boyce Scientific) to aid in illuminating pertinent anatomical structures. Needles were removed after 10 seconds of discontinuation of plunger movement to prevent backflow. Treated animals were placed in a warmed container for recovery (5–10 minutes) until movement was restored. Single injections of 2 µl of the Morpholino modified E1MO-ASOs were delivered via ICV injections as described above for all mice. Time-to-right reflex tests were conducted as previously described.39 Each pup was placed onto its back and the time it takes to right itself on the ground was recorded. The test was terminated at 30 seconds and if an animal had not turned by this time, it was recorded as “Failure”. Righting reflex measurement were recorded daily starting at P7 since unaffected animals start to turn over at this time.

Element 1 antisense oligonucleotide variants (E1MO-ASOs). The following oligos were modified at every base with Morpholino chemistry groups (GeneTools, Philomath, OR):

Original E1MO (26-mer) 5′-CUA UAU AUA GAU AGU UAU UCA ACA AA -3′

E1MOv01 (25-mer) 5′-UAG AUA GCU UUA CAU UUU ACU UAU U-3′

E1MOv02 (25-mer) 5′-UAU GGA UGU UAA AAA GCA UUU UGU U-3′

E1MOv03 (25-mer) 5′-CUA UAU AUA GAU AGC UUU AUA UGG A-3′

E1MOv04 (25-mer) 5′-CAU UUU ACU UAU UUU AUU CAA CAA A-3′

E1MOv05 (25-mer) 5′-GCU UUA UAU GGA CAU UUU ACU UAU U-3′

E1MOv06 (25-mer) 5′-GAU GUU AAA AAG CGU UUC ACA AGA C-3′

E1MOv07 (25-mer) 5′-UAU AUG GAU GUU AUU AUU CAA CAA A-3′

E1MOv08 (25-mer) 5′-GCA UUU UGU UUC ACA AGU UAU UCA A-3′

E1MOv09 (25-mer) 5′-CUA UAU AUA GAU AGC GAC AUU UUA C-3′

E1MOv10 (26-mer) 5′-AGA UAG CUU UAU AUG GAU UUA UUC AA-3′

E1MOv11 (20-mer) 5′-CUA UAU AUA GUU AUU CAA CA-3′

E1Mov12 (24-mer) 5′-UUU AUA UGG AUG AAG ACA UUU UAC-3′

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). Human control and SMA iPSCs40,41 were maintained as floating aggregates of neural progenitor cells as previously described in the neural progenitor growth medium Stemline (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 100 ng/ml human basic fibroblast growth factor (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA), 100 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (Miltenyi Biotec), and 5 μg/ml heparin (Sigma-Aldrich) in ultra-low attachment flasks.42 All stages of motor neuron differentiation were carried out in neural induction medium (NIM) composed of 1:1 Dulbecco's modified essential medium/F12 (Gibco, LifeTechnologies, Carlsbad, CA), 1 × N2 Supplement (Gibco, LifeTechnologies), 5 μg/ml Heparin in Dulbecco's modified essential medium (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 × Non-Essential Amino Acids (Gibco, LifeTechnologies), and 1 × Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco, LifeTechnologies). To induce motor neuron differentiation, spheres were floated in NIM + 0.1 μmol/l all-trans retinoic acid for 2 weeks. 1 μmol/l Purmorphamine (Stemgent, Lexington, MA) was added during the second week. Spheres were then dissociated with TrypLE Express (Gibco, LifeTechnologies) and plated onto Matrigel-coated 12 mm glass cover slips or 6-well plates in NIM supplemented with 1 μmol/l retinoic acid, 1 μmol/l Purmorphamine, 1 × B27 Supplement (Gibco, LifeTechnologies), 200 ng/ml Ascorbic Acid (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 μmol/l cAMP (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/ml BDNF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 10 ng/ml GDNF (PeproTech) and allowed to mature for an additional 4 weeks. After 2 weeks of plate-down, control and SMA iPSC motor neuron cultures were treated for 24 hours with oligonucleotide at a final concentration of either 5 μmol/l or 10 μmol/l using 6 μmol/l E1MOv11 Endo-Porter delivery reagent (GeneTools). Cells treated with Endo-Porter alone were used as a negative control. Half the cells were fixed for immunocytochemistry and the other half lysed and processed for polymerase chain reaction. Cover slips were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 minutes at room temperature and rinsed with PBS. Cells were blocked with 5% Normal Donkey Serum (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA) and/or 5% Normal Goat Serum (Merck Millipore) and permeabilized in 0.2% TritonX-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then incubated in primary antibody solution for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C (mouse anti-SMN (BD Bio 610646, 1:5,000), mouse anti-Tuj1 (Sigma T8660, 1:2,000), rabbit anti-GFAP (Dako Z0334, 1:1,000)), rinsed with PBS, and incubated in secondary antibody solution for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were labeled with Hoechst nuclear stain (Sigma-Aldrich) to label DNA and mounted onto glass slides using FluoroMount medium (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL). RNA was isolated from cell pellets using the RNeasy Mini Kit following manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, 74104, Valencia, CA) and quantified using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). RNA was then treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, M6101, Madison, WI) and converted to cDNA using the Promega Reverse Transcription System (Promega, A3500). DNA was amplified using ExTaq DNA Polymerase (TaKaRa, RR001A, Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions with a 60°C annealing temperature for all primer sets (GAPDH forward 5′-GTG GAC CTG ACC TGC CGT CT-3′, GAPDH reverse 5′-GGA GGA GTG GGT GTC GCT GT-3′, SMN forward 5′-CAT GGT ACA TGA GTG GCT ATC ATA CTG-3′, SMN reverse 5′- TGG TGT CAT TTA GTG CTG CTC TAT G-3′). Amplicon was run out on 1.5% agarose gel (GeneMate, BioExpress, Kaysville, UT) and separated by size using electrophoresis. Gel images were obtained using GelDoc XR+ Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Band intensities were measured using ImageJ image analysis software43 (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Immunohistochemistry of NMJs. Immunochemistry and NMJ analysis were performed following a modified protocol described in detail previously.44,45 Three animals from each treatment and control groups at age P12 were anaesthetized by anesthetic inhalant Isoflurane USP, VetOne (1-chloro-2, 2,2-trifluoroethyl difluoromethyl ether; 50 mg/kg) followed by transcardiac perfusion with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) solution (Dulbecco's, Gibco, LifeTechnologies), and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich). Whole-mount preparations were done by dissecting and examining the longissimus capitis and the splenius capitis muscles. Tissues were stained using specific antibodies including antineurofilament (1:2,000; Chemicon, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and antisynaptophysin (1:200, LifeTechnologies). Acetylcholine receptors were labeled with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated α-bungarotoxin (LifeTechnologies). Muscle preparations were viewed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (40× objective; 0.8NA; Zeiss LSM Model 510 META, Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany, EU). From the confocal microscopy, Z-series stack images of immunostained whole-mount muscles were obtained at sequential focal planes 1 μm apart and merged using microscope integrated software and despeckled by ImageJ Software, Fiji.43

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction assays. SMN▵7 mice were injected on P1 with 100 ng E1MOv11 and harvested on P12. HEK-293T cells were transfected with 50, 100, 500, and 1,000 ng/µl E1MOv11 using Endo-Porter (GeneTools) and harvested 48 hours post-transfection. Total RNA was isolated and homogenized using TRIzol reagent (LifeTechnologies). 2 µg of total RNA was used to generate first-strand cDNA by using 0.5 µg of Oligo(dT)12–18 using 100 ng of random primers, 2 µl deoxynucleotide (dNTP) solution (10 mmol/l) Mix; 4 µl of 5× first-strand buffer, 1.0 µl Dithiothreitol (DTT) (0.1 mol/l) and 1 µl SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (200U/µl) (LifeTechnologies) at 50°C/50 minutes followed by reaction inactivation at 70°C/15 minutes. Cycling conditions were an initial denaturation step (95°C/3 minutes), 30 cycles (94°C/30 seconds; 58°C/0.5 minutes; and 72°C/1 minute), and a final extension step (72°C/10 minutes). Reaction products of cell culture extracts were digested with restriction enzyme DdeI (New England Biolabs, Ipswitch, MA) to distinguish SMN2 from SMN1 transcripts.46 Reaction products were resolved by electrophoresis through a 2.0% agarose gel (GeneMate, BioExpress, Kaysville, UT) and visualized by ethidium bromide staining on FOTODYNE Imaging Systems (Hartland, WI). For cDNA controls specific plasmids pCI-ExSkip and pCI-FL were used.2

Western blots. For the SMNΔ7 mouse Western blots, indicated tissues were collected at selected time points (P7) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue samples were placed at −80°C until ready for analysis. Roughly 100 mg of tissue was homogenized in Jurkat Lysis Buffer (50 mmol/l Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mmol/l NaCl, 20 mmol/l NaH2(PO4), 25 mmol/l NaF, 2 mmol/l ethylenediaminetetraacetate, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN)). Equal amounts of protein were separated on 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels. SMN immunoblots were performed using a mouse SMN specific monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) diluted 1:300 in TBST (Tris-buffered Saline Tween20 (10 mmol/l Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 150 mmol/l NaCl, 0.2% Tween20)) in 1.5% dry milk. Then blots were visualized by chemiluminescence on a Fujifilm imager LAS-3,000 (FujiFilmUSA, Hanover Park, IL) and the corresponding software. To verify equal loading the Westerns were reprobed with Anti-IP90 primary antibody, 1:2,000 (IP90, antiCalnexin) rabbit (Catalog #PA5-34665, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and antirabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) secondary antibody, 1:10,000 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Western blots were performed in quadruplicate or more and representative blots are shown.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Phenotypic improvements in the severe SMNΔ7 mouse models of SMA after E1MOv10, E1MOv11, and E1MOv12 treatment. Figure S2. Time-to-right data for individual doses of E1MOv11.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from CureSMA (C.L.L.), FightSMA and the Gwendolyn Strong Foundation (C.L.L. and E.Y.O), the SMA Foundation (C.P.K.), NIH R25GM064120 (C.W.W.III) and the Missouri Spinal Cord Injury/Disease Research Program (C.L.L.). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sugarman, EA, Nagan, N, Zhu, H, Akmaev, VR, Zhou, Z, Rohlfs, EM et al. (2012). Pan-ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: clinical laboratory analysis of >72,400 specimens. Eur J Hum Genet 20: 27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorson, CL, Hahnen, E, Androphy, EJ and Wirth, B (1999). A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 6307–6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monani, UR, Lorson, CL, Parsons, DW, Prior, TW, Androphy, EJ, Burghes, AH et al. (1999). A single nucleotide difference that alters splicing patterns distinguishes the SMA gene SMN1 from the copy gene SMN2. Hum Mol Genet 8: 1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coady, TH and Lorson, CL (2010). Trans-splicing-mediated improvement in a severe mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J Neurosci 30: 126–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyajima, H, Miyaso, H, Okumura, M, Kurisu, J and Imaizumi, K (2002). Identification of a cis-acting element for the regulation of SMN exon 7 splicing. J Biol Chem 277: 23271–23277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaso, H, Okumura, M, Kondo, S, Higashide, S, Miyajima, H and Imaizumi, K (2003). An intronic splicing enhancer element in survival motor neuron (SMN) pre-mRNA. J Biol Chem 278: 15825–15831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughan, TD, Dickson, A, Osman, EY and Lorson, CL (2009). Delivery of bifunctional RNAs that target an intronic repressor and increase SMN levels in an animal model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 18: 1600–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, NK, Singh, NN, Androphy, EJ and Singh, RN (2006). Splicing of a critical exon of human Survival Motor Neuron is regulated by a unique silencer element located in the last intron. Mol Cell Biol 26: 1333–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartegni, L and Krainer, AR (2002). Disruption of an SF2/ASF-dependent exonic splicing enhancer in SMN2 causes spinal muscular atrophy in the absence of SMN1. Nat Genet 30: 377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima, T and Manley, JL (2003). A negative element in SMN2 exon 7 inhibits splicing in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Genet 34: 460–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima, T, Rao, N, David, CJ and Manley, JL (2007). hnRNP A1 functions with specificity in repression of SMN2 exon 7 splicing. Hum Mol Genet 16: 3149–3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashima, T, Rao, N and Manley, JL (2007). An intronic element contributes to splicing repression in spinal muscular atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 3426–3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, Y, Lorson, CL, Stamm, S, Androphy, EJ and Wirth, B (2000). Htra2-beta 1 stimulates an exonic splicing enhancer and can restore full-length SMN expression to survival motor neuron 2 (SMN2). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 9618–9623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Y, Sahashi, K, Hung, G, Rigo, F, Passini, MA, Bennett, CF et al. (2010). Antisense correction of SMN2 splicing in the CNS rescues necrosis in a type III SMA mouse model. Genes Dev 24: 1634–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Y, Sahashi, K, Rigo, F, Hung, G, Horev, G, Bennett, CF et al. (2011). Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Nature 478: 123–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porensky, PN, Mitrpant, C, McGovern, VL, Bevan, AK, Foust, KD, Kaspar, BK et al. (2012). A single administration of morpholino antisense oligomer rescues spinal muscular atrophy in mouse. Hum Mol Genet 21: 1625–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H, Janghra, N, Mitrpant, C, Dickinson, RL, Anthony, K, Price, L et al. (2013). A novel morpholino oligomer targeting ISS-N1 improves rescue of severe spinal muscular atrophy transgenic mice. Hum Gene Ther 24: 331–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, JH, Schray, RC, Patterson, CA, Ayitey, SO, Tallent, MK and Lutz, GJ (2009). Oligonucleotide-mediated survival of motor neuron protein expression in CNS improves phenotype in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J Neurosci 29: 7633–7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, HH, Chang, JG, Lu, RM, Peng, TY and Tarn, WY (2008). The RNA binding protein hnRNP Q modulates the utilization of exon 7 in the survival motor neuron 2 (SMN2) gene. Mol Cell Biol 28: 6929–6938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, PJ, DiDonato, CJ, Hu, D, Kothary, R, Androphy, EJ and Lorson, CL (2002). SRp30c-dependent stimulation of survival motor neuron (SMN) exon 7 inclusion is facilitated by a direct interaction with hTra2 beta 1. Hum Mol Genet 11: 577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, Y and Wirth, B (2002). hnRNP-G promotes exon 7 inclusion of survival motor neuron (SMN) via direct interaction with Htra2-beta1. Hum Mol Genet 11: 2037–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorson, CL and Androphy, EJ (2000). An exonic enhancer is required for inclusion of an essential exon in the SMA-determining gene SMN. Hum Mol Genet 9: 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirak, S, Arechavala-Gomeza, V, Guglieri, M, Feng, L, Torelli, S, Anthony, K et al. (2011). Exon skipping and dystrophin restoration in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy after systemic phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomer treatment: an open-label, phase 2, dose-escalation study. Lancet 378: 595–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinali, M, Arechavala-Gomeza, V, Feng, L, Cirak, S, Hunt, D, Adkin, C et al. (2009). Local restoration of dystrophin expression with the morpholino oligomer AVI-4658 in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a single-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation, proof-of-concept study. Lancet Neurol 8: 918–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigo, F, Hua, Y, Krainer, AR and Bennett, CF (2012). Antisense-based therapy for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. J Cell Biol 199: 21–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman, EY, Miller, MR, Robbins, KL, Lombardi, AM, Atkinson, AK, Brehm, AJ et al. (2014). Morpholino antisense oligonucleotides targeting intronic repressor Element1 improve phenotype in SMA mouse models. Hum Mol Genet 23: 4832–4845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust, KD, Wang, X, McGovern, VL, Braun, L, Bevan, AK, Haidet, AM et al. (2010). Rescue of the spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in a mouse model by early postnatal delivery of SMN. Nat Biotechnol 28: 271–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Robbins, KL, Glascock, JJ, Osman, EY, Miller, MR and Lorson, CL (2014). Defining the therapeutic window in a severe animal model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 23: 4559–4568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrpant, C, Porensky, P, Zhou, H, Price, L, Muntoni, F, Fletcher, S et al. (2013). Improved antisense oligonucleotide design to suppress aberrant SMN2 gene transcript processing: towards a treatment for spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS One 8: e62114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, CM, Kariya, S, Patruni, S, Osborne, MA, Liu, D, Henderson, CE et al. (2011). Postsymptomatic restoration of SMN rescues the disease phenotype in a mouse model of severe spinal muscular atrophy. J Clin Invest 121: 3029–3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogliotti, RG, Cardona, H, Singh, J, Bail, S, Emery, C, Kuntz, N et al. (2013). The DcpS inhibitor RG3039 improves survival, function and motor unit pathologies in two SMA mouse models. Hum Mol Genet 22: 4084–4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacino, J, Swalley, SE, Song, C, Cheung, AK, Shu, L, Zhang, X et al. (2015). SMN2 splice modulators enhance U1-pre-mRNA association and rescue SMA mice. Nat Chem Biol 11: 511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naryshkin, NA, Weetall, M, Dakka, A, Narasimhan, J, Zhao, X, Feng, Z et al. (2014). Motor neuron disease. SMN2 splicing modifiers improve motor function and longevity in mice with spinal muscular atrophy. Science 345: 688–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le, TT, Pham, LT, Butchbach, ME, Zhang, HL, Monani, UR, Coovert, DD et al. (2005). SMNDelta7, the major product of the centromeric survival motor neuron (SMN2) gene, extends survival in mice with spinal muscular atrophy and associates with full-length SMN. Hum Mol Genet 14: 845–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coady, TH, Baughan, TD, Shababi, M, Passini, MA and Lorson, CL (2008). Development of a single vector system that enhances trans-splicing of SMN2 transcripts. PLoS One 3: e3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman, EY, Yen, PF and Lorson, CL (2012). Bifunctional RNAs targeting the intronic splicing silencer N1 increase SMN levels and reduce disease severity in an animal model of spinal muscular atrophy. Mol Ther 20: 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passini, MA, Bu, J, Richards, AM, Kinnecom, C, Sardi, SP, Stanek, LM et al. (2011). Antisense oligonucleotides delivered to the mouse CNS ameliorate symptoms of severe spinal muscular atrophy. Sci Transl Med 3: 72ra18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glascock, JJ, Osman, EY, Coady, TH, Rose, FF, Shababi, M and Lorson, CL (2011). Delivery of therapeutic agents through intracerebroventricular (ICV) and intravenous (IV) injection in mice. J Vis Exp. Issue 56; doi: 10.3791/2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Butchbach, ME, Edwards, JD and Burghes, AH (2007). Abnormal motor phenotype in the SMNDelta7 mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Neurobiol Dis 27: 207–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, AD, Yu, J, Rose, FF Jr, Mattis, VB, Lorson, CL, Thomson, JA et al. (2009). Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature 457: 277–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sareen, D, Ebert, AD, Heins, BM, McGivern, JV, Ornelas, L and Svendsen, CN (2012). Inhibition of apoptosis blocks human motor neuron cell death in a stem cell model of spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS One 7: e39113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, AD, Shelley, BC, Hurley, AM, Onorati, M, Castiglioni, V, Patitucci, TN et al. (2013). EZ spheres: a stable and expandable culture system for the generation of pre-rosette multipotent stem cells from human ESCs and iPSCs. Stem Cell Res 10: 417–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin, J, Arganda-Carreras, I, Frise, E, Kaynig, V, Longair, M, Pietzsch, T et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, MS, Rose, FF, Rindt, H, Glascock, JJ, Shababi, M, Miller, MR et al. (2013). Development and characterization of an SMN2-based intermediate mouse model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 22: 1843–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, KK, Gibbs, RM, Feng, Z and Ko, CP (2012). Severe neuromuscular denervation of clinically relevant muscles in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet 21: 185–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, DW, McAndrew, PE, Monani, UR, Mendell, JR, Burghes, AH and Prior, TW (1996). An 11 base pair duplication in exon 6 of the SMN gene produces a type I spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) phenotype: further evidence for SMN as the primary SMA-determining gene. Hum Mol Genet 5: 1727–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.