Abstract

Some prokaryotes are known to be specialized in the use of phytoplankton-derived dissolved organic carbon (DOCp) originated by exudation or cell lysis; however, direct quantification measurements are extremely rare. Several studies have described bacterial selectivity based on DOCp quality, but very few have focused on the quantity of DOCp, and the relative importance of each of these variables (for example, quantity versus quality) on prokaryote responses. We applied an adapted version of the MAR-FISH (microautoradiography coupled with catalyzed reporter deposition fluorescence in situ hybridization) protocol using radiolabelled exudates from axenic algal cultures to calculate a specialization index (d') for large bacterioplankton phylogenetic groups using DOCp from different phytoplankton species and at different concentrations to elucidate to what extent the bacterial response to DOCp is driven by resource quantity (different DOCp concentrations) or by quality (DOCp from different phytoplankton species). All bacterial phylogenetic groups studied had lower d' at higher DOCp concentration, indicating more generalist behavior at higher resource availabilities. Indeed, at increasing resource concentrations, most bacterial groups incorporated DOCp indiscriminately, regardless of its origin (or quality). At low resource concentrations, only some specialists were able to actively incorporate the various types of organic matter effectively. The variability of bacterial responses to different treatments was systematically higher at varying concentrations than at varying DOCp types, suggesting that, at least for this range of concentrations (10–100 μM), DOCp quantity affects bacterial responses more than quality does. Therefore, resource quantity may be more relevant than resource quality in the bacterial responses to DOCp and affect how bacterioplankton use phytoplankton-derived carbon.

Introduction

Oceanic dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is one of the largest organic carbon reservoirs on Earth, and is approximately equivalent to the atmospheric CO2 stock (Hedges, 1992). Marine heterotrophic bacteria are the major regulators of this DOC pool, incorporating it into biomass (bacterial secondary production), respiring it into inorganic carbon or degrading the labile fractions of this DOC into more refractory compounds (Jiao et al., 2010). Despite their importance in the global carbon cycle, DOC–microbe interactions, in particular bacterioplankton specialization in DOC utilization, are not yet fully understood (Azam and Malfatti, 2007; Kujawinski, 2011).

Most of the DOC found in the sea surface has marine origin (Opsahl and Benner, 1997). Phytoplankton exudation or cell lysis (DOCp) represents a primary source of labile organic carbon-supplying bacterial metabolism (Baines and Pace, 1991). Different phytoplankton species release a vast range of different molecules (Repeta et al., 2002; Romera-Castillo et al., 2010; Sarmento et al., 2013), and these organic compounds have different degrees of lability (Romera-Castillo et al., 2011). In nature, DOCp varies in quality (lability) and quantity in space and time, yet information on whether which of these two factors (quantity or quality) is more relevant to bacterial activity is scarce or absent.

Prokaryotic specialization in the use of DOCp is a recurrent topic in microbial ecology literature; however, quantitative direct measurements are extremely difficult to achieve, and the few attempts required sophisticated methods such as nanoscale secondary-ion mass spectrometry combined with halogen in situ hybridization (Alonso et al., 2012). Still, recent advances provided a new look at an old topic: our understanding of DOC–bacteria interaction has moved from an extreme specialization view, where few specific bacterioplankton strains responded to a particular phytoplankton species (for example, González et al., 2000; Schafer et al., 2002; Pinhassi et al., 2004; Grossart et al., 2005; Rooney-Varga et al., 2005; Sapp et al., 2007a) to a more moderate (generalist) and complex view where many types of bacteria are involved in the decomposition of different types of DOCp with differences in their uptake rates (Nelson and Carlson, 2012; Sarmento and Gasol, 2012; Landa et al., 2013; Paver et al., 2013; Morana et al., 2014).

Recent studies have demonstrated that different bacterial phylogenetic groups do not incorporate DOCp originated from different sources (that is, different phytoplankton species) in the same proportions (Nelson and Carlson, 2012; Sarmento and Gasol, 2012). Nelson and Carlson (2012) evaluated the performance of different bacterial clades growing on different DOC sources (namely, phytoplankton exudates and lysates) disregarding the particular DOC concentrations added. Other similar enrichment experiments have been performed with a fixed DOC concentration, varying only the quality (phytoplankton species origin) of the amendment (Sarmento and Gasol, 2012). However, the ‘resource allocation hypothesis' (Koch, 1985) predicts that microbial decomposition rates should be concentration-dependent, and that substrate decomposition might not be linear and decrease progressively once the concentration of a certain substrate falls below a certain threshold. Independent studies on soil (German et al., 2011) and aquatic microbial communities (Attermeyer et al., 2014) have found indications that the ‘resource allocation hypothesis' was accurate for some substrates but not for others, depending on the ubiquity or rarity of the specific microbial enzymes involved in those substrate's decomposition. The fact is that very few studies have evaluated the performance of specific bacterial phylogenetic groups at varying DOC sources (testing for quality) and quantities simultaneously (but see Eiler et al., 2003; Alonso and Pernthaler, 2006).

Various studies have used the network approach to illustrate the interactions among microbes, yet the interactions are usually defined by co-existence in a water sample or by co-variation throughout time series (for example, Barberan et al., 2011; Eiler et al., 2011; Steele et al., 2011; Lima-Mendez et al., 2015), yet rarely by a real quantification of the interaction strengths (ISs) in terms of carbon flow, for example. We previously developed a metric that captures the mutualistic interaction of several bacterioplankton phylogenetic groups and different phytoplankton species mediated by DOCp, applying an adapted version of the MAR-FISH (microautoradiography combined with fluorescent in situ hybridization) technique with radiolabeled exudates from axenic algal cultures (Sarmento and Gasol, 2012). This approach can be used to determine the specialization indices of various bacterioplankton phylogenetic groups in using DOCp from different phytoplankton species at different concentrations.

We set to evaluate the variation in the degree of specialization of each phylogenetic group as a function of resource availability, and to elucidate which factor is more determinant in the bacterial response to DOCp: either resource quantity (different DOCp concentrations) or quality (DOCp from different phytoplankton species, which we had showed before that was of different value).

Materials and methods

The experimental procedures are explained in detail in Sarmento and Gasol (2012), where similar experiments were performed but using only one fixed DOCp concentration.

Phytoplankton cultures and preparation of radiolabeled exudates

We prepared radiolabeled DOCp from three axenic cultures obtained from the Provasoli–Guillard National Center for Culture of Marine Phytoplankton (CCMP) and used it as a tracer in the MAR-FISH technique. The three axenic strains used were as follows: the prymnesiophyte Isochrysis galbana Parke (CCMP1323), the prasinophyte Micromonas pusilla (RW Butcher) I Manton and M Parke (CCMP1545) and the cyanobacteria Synechococcus sp. (CCMP1183).

The cultures were grown to exponential phase in 50-ml tissue-culture flasks in presence of 150 μCi of NaH14CO3, in F/2 culture medium elaborated with aged, filtered and autoclaved coastal Mediterranean seawater and incubated at 20 °C under an artificial radiation of 100 μmolphoton m−2 s−1, in a 16:8 h light:dark cycle, until cell density increased about one order of magnitude. Aliquots for phytoplankton counts were taken at the beginning and end of the growing period of 3 days. Bacterial contamination was checked in the same samples using epifluorescence microscope observations under blue and ultraviolet wavelength excitation, following 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (10 μg ml−1, final concentration). Parallel non-radioactive cultures were run simultaneously in the exact same conditions to measure DOC concentration in each culture. DOC analysis was performed using standard methods as described in Romera-Castillo et al. (2010).

Labeled DOCp stocks were prepared as described in Sarmento and Gasol (2012); 40 ml of cultures were gently filtered onto previously flushed 0.2-μm Sterivex filters to isolate the DOCp from cells. The filtrates were acidified with 3 ml of 6 M HCl and left open in an orbital shaker overnight for dissipation of unassimilated NaH14CO3. The pH of the exudates was then adjusted to ~8 with 6 M NaOH, and a 3-ml subsample was radioassyed (DO14C) in 15 ml of Ultima Gold liquid scintillation cocktail.

Microautoradiography coupled with catalyzed reporter deposition fluorescence in situ hybridization

MAR-FISH allows tracing the carbon transference through phytoplankton and its re-assimilation by heterotrophic prokaryotes, revealing how many and which kind of heterotrophic prokaryote incorporate each type of DOCp. Subsurface 150-μm pre-filtered seawater samples (20 ml each) taken on 22 March 2010 from a NW Mediterranean coastal site (Blanes Bay Microbial Observatory, http://www.icm.csic.es/bio/projects/icmicrobis/bbmo/) were incubated in controlled in situ temperature in the dark with addition of the different radiolabeled compounds at three different concentrations: 10, 30 and 100 μM DOC final concentration. The DOC concentration on that date at the Blanes Bay Microbial Observatory was 64.9 μM. DOC in Blanes Bay accumulates during summer, from an annual minimum by early March (less than 60 μM) to the annual maximum by early September (higher than 100 μM). The average value for the 2008–2010 period was 79.1 μM, with maxima reaching 140 μM (Romera-Castillo et al., 2013).

To determine the exact amounts of DOCp additions in each incubation flask, we varied the volume of exudate solution added that ranged from 200 μl to 4.5 ml. Dead control incubations were performed by fixing the sample with formaldehyde (1.8%) before (>5 min) the addition of the radiolabeled compounds. False positives obtained in these dead controls (always <0.5% of DAPI-stained cells) were subtracted.

A previous study tested the reproducibility of this technique and showed good agreement between incubation replicates (Sarmento and Gasol, 2012). In order to generate a complete matrix on our experimental design in a reasonable time and effort, we did not do replicated incubations, as processing MAR-FISH samples from end to end is a very time-consuming task.

After 5-h incubation, the samples were fixed overnight with formaldehyde (1.8%) at 4 ºC, gently filtered on 0.2-μm polycarbonate filters (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA, 25 mm diameter) and processed with the MAR-FISH protocol.

MAR-FISH was performed with the protocol initially described by Alonso and Pernthaler (2005), with some modifications detailed in Sarmento and Gasol (2012). After hybridization following the CARD-FISH (catalyzed reporter deposition fluorescence in situ hybridization) protocol (described hereafter), the filters were glued onto glass slides with an epoxy adhesive (UHU plus; UHU GmbH, Bühl, Germany). The slides were embedded in 46-°C-tempered photographic emulsion (KODAK NTB-2) containing 0.1% agarose (gel strength 1%, >1 kg cm−2) in a dark room and were placed on an ice-cold metal bar for ~5 min to allow the emulsion to solidify. They were subsequently placed inside black boxes at 4 °C until development. We found that the optimal exposure time was 9 days (data not presented). For development, we submerged the exposed slides for 3 min in the developer (KODAK D19), 30 s rinsing with distilled water and 3 min in fixer (KODAK Tmax), followed by 5 min of washing with tap water. The slides were then dried in a dessicator overnight, stained with DAPI (1 μg ml−1) and inspected in an Olympus BX61 epifluorescence microscope. CARD-FISH-positive cells (hybridized with the specific probe) appear in bright green under blue light excitation. MAR-FISH positives contain, additionally, dark silver grains accumulated above the bacterial cells on the photographic emulsion, resulting from radioactive decay of labeled DOCp, and are clearly visible under white light in the same microscope.

CARD-FISH was carried out following the protocol described previously (Pernthaler et al., 2004). Several horseradish peroxidase probes were used to characterize the composition of the bacterial community in the original water samples, using the same procedure as described in Alonso-Sáez and Gasol (2007). The horseradish peroxidase-labeled probes used were as follows: EUB-338, EUB-II and EUB-III (target most Eubacteria; Amann et al., 1990; Daims et al., 1999); GAM42a (targets most Gammaproteobacteria; Manz et al., 1992); ALF968 (targets most Alphaproteobacteria; Neef, 1997); CF319 (targets many groups belonging to the Bacteroidetes group; Manz et al., 1996); ROS537 (targets members of the Roseobacter–Sulfitobacter–Silicibacter group; Eilers et al., 2001); NOR5-730 (targets members of the NOR5 cluster; Eilers et al., 2001); Alt1413 (targets Alteromonas and Colwellia; Eilers et al., 2000b); and SAR11-441 R (targets the SAR11 cluster; Morris et al., 2002); EUB antisense probe NON338 (Wallner, 1993) was used as a negative control. All probes were purchased from biomers.net (Ulm, Germany). Specific hybridization conditions were established by addition of formamide to the hybridization buffers (20% formamide for the NON338 probe, 45% formamide for the ALF968 and SAR11-441 R probes, 50% for NOR5-730, 60% for Alt1413 and 55% for the other probes).

Counterstaining of CARD-FISH preparations was performed with DAPI (1 μg ml−1). Between 500 and 1000 DAPI-positive cells of each phylogenetic group were counted in a minimum of 10 fields, at least 50 MAR-FISH-positive cells.

Calculating IS and network properties

The MAR-FISH results can be presented in different ways, depending on which parameter is chosen to relate to the number of cells taking up the radiolabeled compounds. Hence, the number of MAR-positive cells belonging to a certain bacterial phylogenetic group (MAR+g) can be divided by the number of cells from that phylogenetic group (MAR+g/CARD-FISH+g), by MAR positives within Eubacteria-hybridized cells (MAR+g/MAR+Eub) or by the total bacterial abundance (MAR+g/DAPI counts). Here, we have calculated the IS between a phytoplankton strain and the different heterotrophic prokaryote groups mediated by the use of DOCp in two different ways: (1) the number of MAR-FISH positives (cells actively taking up the radiolabeled compounds) as a proportion of the total bacterial community (MAR+g/DAPI counts) and (2) as the number of MAR-FISH positives (cells actively taking up the radiolabeled compounds) as a proportion of the active community (MAR+g/MAR+Eub). Thus, in both cases, if all cells of a given bacterial group would use a particular DOCp, then that group and the corresponding algae would have a strong interaction, and both MAR+g/MAR+Eub and MAR+g/DAPI counts would approach 100%, whereas when no cells used the substrate, this interaction would be zero (no interaction). We also present the results as MAR+g/CARD-FISH+g, which reflects the number of active cells within each bacterial phylogenetic group. Although informative, this metric is not pertinent for IS calculation purposes.

Networks were built aggregating the results of the different treatments in one single network, and specialization indices (Blüthgen et al., 2006; Blüthgen et al., 2007) were calculated at the network level (H2') and at the bacterial phylogenetic group level (d') using H2fun and dfun functions from bipartite package (Dormann et al., 2008; Dormann et al., 2009; Dormann, 2011) in Software R (http://www.r-project.org), after multiplying IS values by 1000 and rounding them to integers, as calculations of specialization indices require absence of decimals. Specialization indices H2' and d' range from 0 for the most generalized to 1.0 for the most specialized case (Blüthgen et al., 2006).

Results

Bacterial community composition at the Blanes Bay Microbial Observatory on 22 March 2010 was dominated by members of the SAR11 clade (51.1%) and Bacteroidetes (22.7%). Gammaproteobacteria (5.5%) and Roseobacter (4.0%) had lower relative abundance. Other targeted groups, namely NOR5 and Alteromonas, represented less than 1% of the community in that particular sample, and were discarded from our further analyses. The probes targeting Eubacteria hybridized 88.2% of DAPI-stained cells, and no significant changes in the community structure were observed during the 5-h incubations (data not shown).

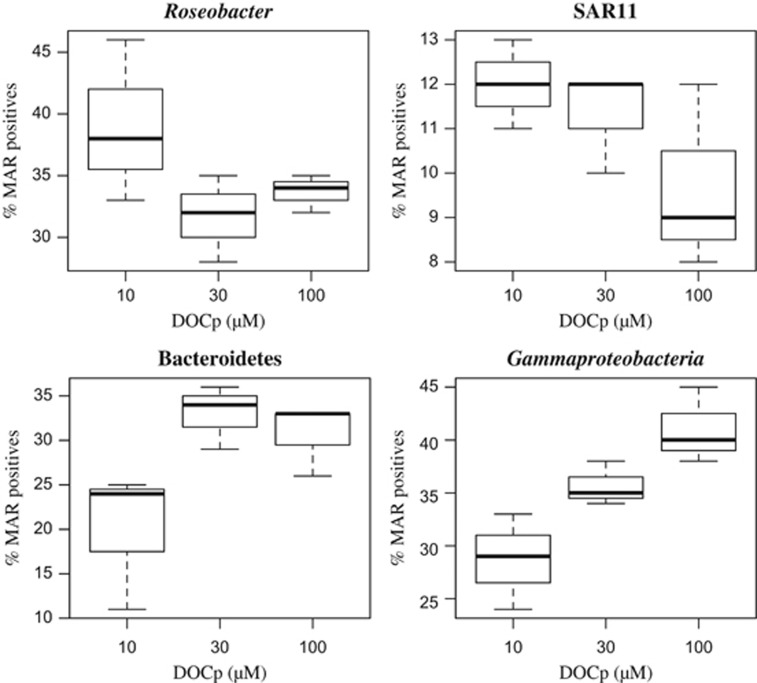

The results expressed as a percentage of active cells within each heterotrophic bacterial phylogenetic group (MAR+g/CARD-FISH+g) illustrate the variety of responses in processing the DOCp originated from different DOCp concentrations, independently of the phytoplankton species that originated that DOCp (Figure 1). The proportion of active cells belonging to Bacteroidetes or Gammaproteobacteria increased with increasing DOCp concentrations. On the contrary, within SAR11 and Roseobacter the percentage of active cells decreased with DOCp availability. Overall, the more active groups were Roseobacter (on average 38.7% of active cells) and Gammaproteobacteria (on average 30.2% of active cells), followed by Bacteroidetes (on average 23.3% of active cells) and SAR11 were the least active (only 10.2% of active cells, on average).

Figure 1.

Box plots presenting the percentage of MAR-FISH-positive (cells actively taking up the radiolabeled compounds) within each heterotrophic bacterial phylogenetic group (MAR+g/CARD-FISH+g, see text), for the different DOCp concentrations (grouping the results by the three different algal treatments). The central full line indicates the median value, the boxes indicate the lower and upper quartiles, and vertical lines indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles. Note the different scales on the y axes.

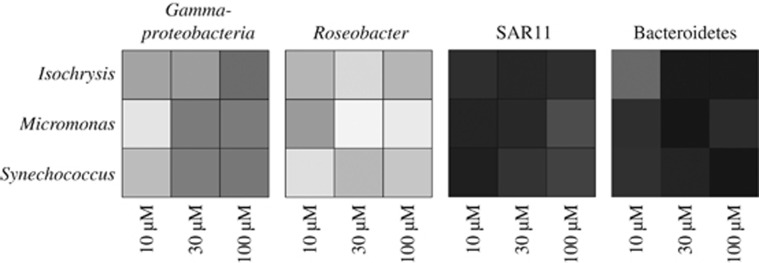

A bidimensional heat map of IS obtained aggregating the results of the different treatments, using the contribution of MAR-FISH-positive cells to the total community (MAR+g/DAPI counts), illustrates the different responses of the various bacterial phylogenetic groups to different DOC sources at different concentrations (Figure 2). In this figure, rows represent different DOC types and columns represent different DOC concentrations. Within different DOCp sources, some differences were observed. IS increased notably with DOCp concentration in Bacteroidetes and Gammaproteobacteria, whereas Roseobacter and SAR11 presented the opposite trend (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bidimensional heat map of the IS between marine heterotrophic bacteria phylogenetic groups and different DOC sources at different concentrations. Darker tones of gray indicate stronger IS (‘MAR+g/DAPI counts' data from Table 1 and Figure 2). Roseobacter and SAR11 are both subgroups of Alphaproteobacteria.

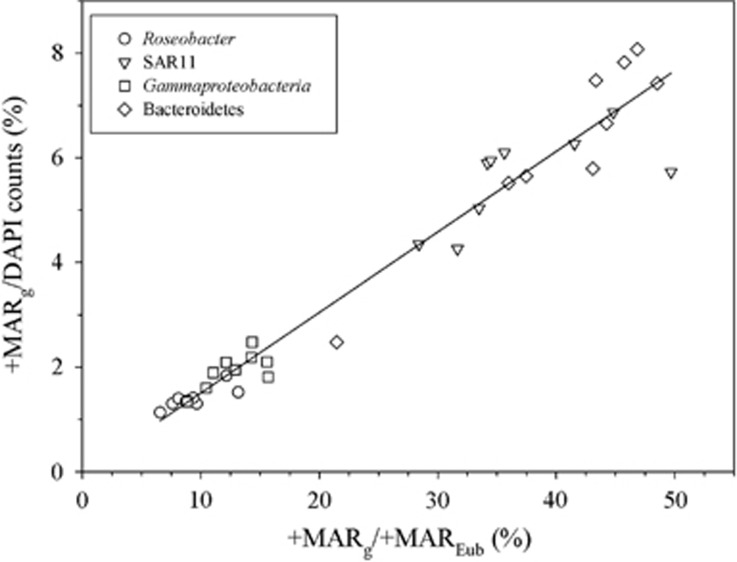

To explore which metric better expresses the IS between phytoplankton and the bacterial phylogenetic groups, we tested the different ways of presenting MAR-FISH results (Table 1): the number of MAR-positive cells belonging to a certain bacterial phylogenetic group (MAR+g) divided by the sum of the active cells from the different groups (MAR+g/MAR+Eub) or total bacterial abundance (MAR+g/DAPI counts). The coefficients of variation and specialization indices for results expressed both as MAR+g/MAR+Eub and MAR+g/DAPI counts (Tables 2 and 3) show differences in absolute values, but similar trends for both IS metrics (Figure 3).

Table 1. MAR-FISH results.

| DOC type | DOC conc. (μM) |

Alphaproteobacteria |

Gammaproteobacteria | Bacteroidetes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roseobacter | SAR11 | ||||

| MAR+g/DAPI counts (%) | |||||

| Isochrysis | 10 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 2.5 |

| 30 | 1.3 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 7.8 | |

| 100 | 1.4 | 5.9 | 2.5 | 7.5 | |

| Micromonas | 10 | 1.8 | 6.3 | 1.3 | 5.7 |

| 30 | 1.1 | 5.9 | 2.1 | 8.1 | |

| 100 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 2.1 | 5.8 | |

| Synechococcus | 10 | 1.3 | 6.9 | 1.6 | 5.5 |

| 30 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 1.9 | 6.7 | |

| 100 | 1.4 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 7.4 | |

| MAR+g/MAR+Eub (%) | |||||

| Isochrysis | 10 | 13.2 | 49.7 | 15.7 | 21.5 |

| 30 | 7.6 | 35.6 | 11.1 | 45.7 | |

| 100 | 8.1 | 34.2 | 14.3 | 43.4 | |

| Micromonas | 10 | 12.2 | 41.5 | 8.8 | 37.5 |

| 30 | 6.6 | 34.5 | 12.1 | 46.8 | |

| 100 | 9.7 | 31.7 | 15.6 | 43.1 | |

| Synechococcus | 10 | 8.8 | 44.8 | 10.4 | 36.0 |

| 30 | 9.4 | 33.5 | 12.9 | 44.2 | |

| 100 | 8.8 | 28.4 | 14.2 | 48.5 | |

Abbreviations: Conc., concentration; DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DOC, dissolved organic carbon; MAR-FISH, microautoradiography combined with fluorescent in situ hybridization.

Table results presented (1) as the number of MAR-FISH positives as a proportion of the total bacterial community (MAR+g/DAPI counts) and (2) number of MAR-FISH positives as a proportion of the interacting community (MAR+g/MAR+Eub); Roseobacter and SAR11 are both subgroups of Alphaproteobacteria.

Table 2. Coefficients of variation of the bacterial responses to different treatments.

|

Alphaproteobacteria |

Gammaproteobacteria | Bacteroidetes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roseobacter | SAR11 | |||

| MAR+g/DAPI counts (%) | ||||

| Same DOCp type at different conc. | ||||

| Isochrysis | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.51 |

| Micromonas | 0.26 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.21 |

| Synechococcus | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Average | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.29 |

| Same DOCp conc. (μM) from different sources | ||||

| 10 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.39 |

| 30 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| 100 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

| Average | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.21 |

| MAR+g/MAR+Eub (%) | ||||

| Same DOCp type at different conc. | ||||

| Isochrysis | 0.32 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.36 |

| Micromonas | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.11 |

| Synechococcus | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| Average | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| Same DOCp conc. (μM) from different sources | ||||

| 10 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.28 |

| 30 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.03 |

| 100 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Average | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

Abbreviations: Conc., concentration; DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DOCp, phytoplankton-derived dissolved organic carbon; IS, interaction strength; MAR, microautoradiography.

Coefficient use two different IS metrics (MAR+g/DAPI counts and MAR+g/MAR+Eub, see text for details); Roseobacter and SAR11 are both subgroups of Alphaproteobacteria.

Note that these are not true replicates.

Table 3. Specialization indices.

| Subnetwork | d' ( × 10−2) |

H2' ( × 10−2) Entire network | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alphaproteobacteria |

Gammaproteobacteria | Bacteroidetes | |||

| Roseobacter | SAR11 | ||||

| MAR+g/DAPI counts (%) | |||||

| Isochrysis | 1.23 | 1.39 | 0.52 | 4.02 | 2.46 |

| Micromonas | 1.37 | 0.62 | 1.15 | 0.51 | 1.21 |

| Synechococcus | 0.02 | 1.78 | 0.39 | 0.89 | 1.36 |

| 10 μM | 0.67 | 0.32 | 1.31 | 2.13 | 1.69 |

| 30 μM | 0.41 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| 100 μM | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.23 |

| Altogether | 0.88 | 1.33 | 0.73 | 1.94 | 1.42 |

| MAR+g/MAR+Eub (%) | |||||

| Isochrysis | 1.39 | 1.62 | 0.52 | 4.82 | 3.50 |

| Micromonas | 1.27 | 0.64 | 1.22 | 0.49 | 1.29 |

| Synechococcus | 0.02 | 1.77 | 0.39 | 0.89 | 1.37 |

| 10 μM | 0.66 | 0.34 | 1.41 | 2.41 | 1.92 |

| 30 μM | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| 100 μM | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.24 |

| Altogether | 0.92 | 1.48 | 0.77 | 2.33 | 1.64 |

Abbreviations: DAPI, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; IS, interaction strength; MAR, microautoradiography.

Specialization indices use two different IS metrics (MAR+g/DAPI counts and MAR+g/MAR+Eub, see text for details), calculated for each bacterial phylogenetic group (d') and for the entire interaction networks (H2') as proposed by Blüthgen et al. (2007).

‘Altogether' refers to the results merging all treatments in a single network.

Figure 3.

Type II linear regression between two different IS metrics: %+MAR+g/DAPI counts=% +MAR+g/MAR+Eub × 0.154−0.036 (n=36, r=0.98; P<0.0001).

The average coefficients of variation of the bacterial responses to the different treatments were systematically higher at varying concentrations (in Table 2, ‘same DOCp type at different concentration') than at varying DOCp sources (in Table 2, ‘same DOCp concentration (μM) from different sources'). Moreover, higher coefficients of variation were always observed at lower DOCp concentrations (10 μM), except for SAR11 in the results expressed as MAR+g/DAPI counts that followed the opposite trend (Table 2).

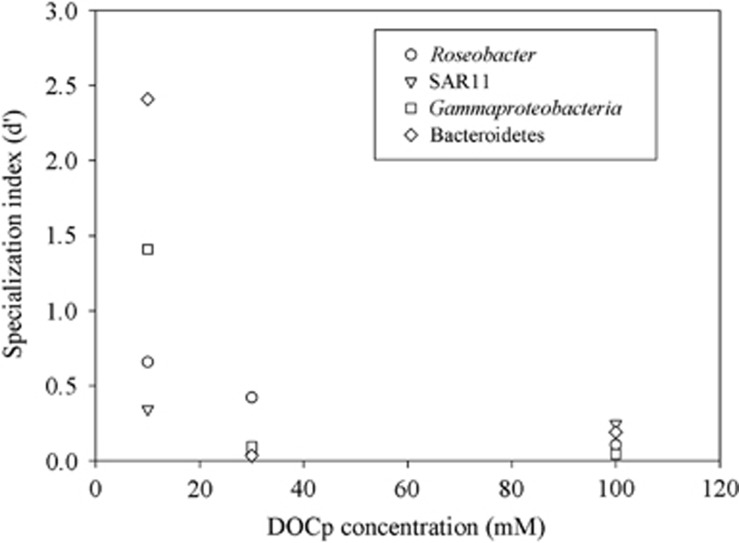

The construction of interaction networks allowed calculating specialization indices for each bacterial phylogenetic group (d') and for the entire network (H2'). These indices reflect how much the distribution of ISs deviates from that occurring by chance. Higher values indicate higher degree of specialization and lower values indicate higher generalism. The specialization index values obtained were relatively low (Table 3). Still, a comparative analysis between bacterial phylogenetic groups and between networks allows the identification of trends in the relative degrees of specialism. All bacterial phylogenetic groups had higher d' at lower DOCp concentration (10 μM), regardless of the DOCp source. Members of Gammaproteobacteria were more specialized when exposed to Micromonas exudates; SAR11 were more specialized in the Synechococcus treatment; and Bacteroidetes were more specialized using Isochrysis-derived DOCp. Roseobacter was the only group that showed some divergence between the two different IS metrics. Using MAR+g/DAPI counts, Roseobacter were more specialized with Micromonas exudates, whereas using MAR+g/MAR+Eub the Isochrysis treatment had higher d' (Table 3).

Comparing the results of the different bacterial groups in the use of algal-derived DOC merging all treatments in a single network, Bacteroidetes had higher d' (were more specialists), and Gammaproteobacteria were the most generalist group (‘altogether' in Table 3). Concerning the specialization indices for the entire networks (H2'), lower DOCp concentration (10 μM) had higher H2' values, and Isochrysis was the algae that induced higher specialization within the interaction network (Table 3).

Discussion

Resource availability and nutritional value determine competition and niche partitioning among coexisting species in a community. Optimal foraging models for consumer-prey interactions predict higher specialization in highly productive systems, and more generalist diets in low-resource regimes (for example, Werner and Hall, 1974; Gende et al., 2001). However, this applies only at the individual or population level. The picture might be different when scaling up to the community level, as indicated by our measures of DOCp incorporation by a bacterioplankton community. At the community level, specialization can be expressed as the mean specialization of the species present in that community (Devictor et al., 2010). Our observations suggest that higher resource availability actually enhanced generalism in the interaction network among bacterial large phylogenetic groups (Table 3; Figure 4). This is somehow expected at a community level perspective: communities that can survive in low-resource environments, such as deserts, for example, are usually composed of specialized species. Here, we provide experimental evidence that increasing resources enhance generalism in bacterioplankton communities.

Figure 4.

Specialization index d' (Blüthgen et al., 2007) of the different bacterial phylogenetic groups as a function of DOCp concentration. Roseobacter and SAR11 are both subgroups of Alphaproteobacteria.

The two different metrics used to express IS differed in absolute numbers (Table 1), but suggested similar trends regarding specialization among bacterial groups (d') and entire networks (H2' Table 3). Actually, both metrics were highly correlated (Figure 3), indicating that it does not make much difference whether we consider the proportion of active cells over the whole community or only over the interacting community, at least for the DOCp treatments. We conclude that both metrics are tenable and, at least for DOCp, provide similar results.

Within each different DOCp source, some differences were also observed among treatments. Bacteroidetes and SAR11 had the stronger interactions. IS increased notably with DOCp concentration in Bacteroidetes and Gammaproteobacteria, whereas Roseobacter and SAR11 presented the opposite trend (Figure 2). Despite the fact that the probes used target groups from different taxonomical ranks, most of these groups present ecological coherence (Philippot et al., 2010). Thus, our results provide valuable information concerning the auto-ecology of the most abundant bacterial large phylogenetic groups in the sea, sometimes difficult to discern in the huge amount of genomic data (for example, Lauro et al., 2009). For example, our observations reinforce previous reports that SAR11 can grow in culture only with low substrate concentration (Rappé et al., 2002).

Bacteroidetes had higher d' values, enhanced by Isochrysis DOCp, which was the alga that induced higher specialization within the interaction network (Table 3). Previous studies comparing bacterial communities associated to algal cultures in non-axenic conditions had already pointed out that Isochrysis had very specific bacterial associated taxa, namely isolates from the genera Flexibacter belonging to the Cytophaga–Flavobacterium–Bacteroides phylum (Schwenk et al., 2014). It is not uncommon to observe members of Bacteroidetes associated with phytoplankton (for example Schafer et al., 2002; Pinhassi et al., 2004; Grossart et al., 2005; Sapp et al., 2007b), and our results reinforce the relevance of this group in incorporating organic carbon derived from some phytoplankton species.

In contrast, Gammaproteobacteria were the most generalist group. Gammaproteobacteria have also many times been identified associated with particles, namely phytoplankton cells (for example, Sapp et al., 2007a, 2007b), but also in enrichment experiments or disturbances (that is, bottle effects, Eilers et al., 2000a; Pinhassi and Berman, 2003). As we observed the same generalistic behavior in a previous study using the same MAR-FISH technique with different algal strains (Sarmento and Gasol, 2012), we deduce that this bacterial group can respond to enrichment and confinement, independently of the type or quantity of DOCp added.

All bacterial phylogenetic groups had higher d' at lower DOCp concentration (Figure 4; Table 3). Lower DOCp concentration (10 μM) had also higher H2' values. In other words, the IS distribution of bacterial phylogenetic groups toward the different DOCps was more uneven when there was low DOCp concentration. With an increasing resource availability, IS distribution among DOCp sources became more even, indicating a more generalist network where various bacterial groups incorporated resources indiscriminately, regardless of the source (or quality). At low resource concentration, only few specialists were able to actively incorporate specific types of organic carbon effectively. A single-cell genome analysis (Swan et al., 2013) comparing the existing cultures with natural bacterioplankton from different oligotrophic surface oceans revealed extreme specialization and the prevalence of genome streamlining in low resource conditions, which supports our observations of inverse relationship between specialization and resource availability. The cost of genome streamlining in free-living bacteria would result in a reduction in physiological flexibility, leading to specialization in resource utilization (Swan et al., 2013). Conversely, large-genome copiotrophs would have higher genetic potential (more genes coding for a higher number of enzymes), allowing handling a wider range of molecules, which makes them more generalists (Lauro et al., 2009); however, they need a higher amount of energy to start the synthesis of such a complex enzymatic machinery.

The coefficients of variation of the bacterial responses to different treatments were systematically higher at varying concentrations (‘same DOCp type at different concentrations') than at varying DOCp sources (‘same DOCp concentration from different sources'), suggesting that, at least for these ranges of concentrations, DOCp quantity affects bacterial responses more than quality does. These results highlight the importance of DOC quantity in evaluating bacterial responses to DOC additions, as suggested by previous studies (Eiler et al., 2003; Alonso and Pernthaler, 2006; Attermeyer et al., 2014).

It has already been demonstrated that the organic matter excreted by different phytoplankton species do not stimulate all major phylogenetic groups of bacteria in the same way (Sarmento and Gasol, 2012). Indeed, it suggests that the diverse bacterial groups could coexist in seawater by utilizing different resources (that is, different types of organic molecules). Our results here indicate that the concentration of available substrate for bacteria could affect even more the strength of their interactions with phytoplankton species through DOCp. Moreover, it appears that different bacterial groups harbor diverse concentration-dependent patterns of DOCp uptake (Figure 1): some groups were more active with increasing DOCp concentrations (Bacteroidetes, Gammaproteobacteria), whereas some others followed an opposite pattern (SAR11, Roseobacter). This observation provides evidence for niche partitioning in the use of DOCp by bacterioplankton. Temporal fluctuations in biotic and abiotic factors, as well as microscale processes, provide a variety of substrate quantity and quality, creating numerous heterogeneous habitats that maintain the high diversity of heterotrophic bacteria in the sea (Stocker, 2012).

Overall, we found that increasing resources enhance generalism in bacterioplankton communities, and that resource quantity may be more relevant than quality concerning bacterial responses to DOCp, at least at a large phylogenetic group level, and this should be taken into account when designing experiments and interpreting results of bacterioplankton use of phytoplankton-derived carbon.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Professor Dr Nico Blüthgen and Dr Adriano Caliman for enriching discussions that inspired this work. Work of HS was supported by the Spanish MCyI (Juan de la Cierva Fellowship JCI-2008-2727), by CNPq (Project: 474759/2013-0) and FAPESP (Process: 2014/14139-3). JMG was supported by Spanish MCyI grants DOREMI (CTM2012-34294) and HOTMIX (CTM2011-30010/MAR) and by Grup Consolidat de Recerca 2014SGR/1179 (Generalitat de Catalunya).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alonso C, Musat N, Adam B, Kuypers M, Amann R. (2012). HISH–SIMS analysis of bacterial uptake of algal-derived carbon in the Río de la Plata estuary. Syst Appl Microbiol 35: 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso C, Pernthaler J. (2005). Incorporation of glucose under anoxic conditions by bacterioplankton from coastal North sea surface waters. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 1709–1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso C, Pernthaler J. (2006). Concentration-dependent patterns of leucine incorporation by coastal picoplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 2141–2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Sáez L, Gasol JM. (2007). Seasonal variation in the contribution of different bacterial groups to the uptake of low molecular weight-compounds in NW Mediterranean coastal waters. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 3528–3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann RI, Binder BJ, Olson RJ, Chisholm SW, Devereux R, Stahl DA. (1990). Combination of 16 S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol 56: 1919–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attermeyer K, Hornick T, Kayler ZE, Bahr A, Zwirnmann E, Grossart H-P et al. (2014). Enhanced bacterial decomposition with increasing addition of autochthonous to allochthonous carbon without any effect on bacterial community composition. Biogeosciences 11: 1479–1489. [Google Scholar]

- Azam F, Malfatti F. (2007). Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat Rev Microbiol 5: 782–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baines SB, Pace ML. (1991). The production of dissolved organic-matter by phytoplankton and its importance to bacteria - patterns across marine and fresh-water systems. Limnol Oceanogr 36: 1078–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Barberan A, Bates ST, Casamayor EO, Fierer N. (2011). Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J 6: 343–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blüthgen N, Menzel F, Bluthgen N. (2006). Measuring specialization in species interaction networks. BMC Ecol 6: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blüthgen N, Menzel F, Hovestadt T, Fiala B, Blüthgen N. (2007). Specialization, constraints, and conflicting interests in mutualistic networks. Curr Biol 17: 341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daims H, Brüehl A, Amann R, Schleifer K-H, Wagner M. (1999). The domain-specific probe EUB338 is insufficient for the detection of all bacteria: development and evaluation of a more comprehensive probe set. Syst Appl Microbiol 22: 434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devictor V, Clavel J, Julliard R, Lavergne S, Mouillot D, Thuiller W et al. (2010). Defining and measuring ecological specialization. J Appl Ecol 47: 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann CF, B. G, Fruend J. (2008). Introducing the bipartite package: analysing ecological networks. R News 8: 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann CF, Fründ J, Blüthgen N, Gruber B. (2009). Indices, graphs and null models: analyzing bipartite ecological networks. Open Ecol J 2: 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann CF. (2011). How to be a specialist? Quantifying specialisation in pollination networks. Netw Biol 1: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Eiler A, Langenheder S, Bertilsson S, Tranvik LJ. (2003). Heterotrophic bacterial growth efficiency and community structure at different natural organic carbon concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 3701–3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiler A, Heinrich F, Bertilsson S. (2011). Coherent dynamics and association networks among lake bacterioplankton taxa. ISME J 6: 330–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers H, Pernthaler J, Amann R. (2000. a). Succession of pelagic marine bacteria during enrichment: a close look at cultivation-induced shifts. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 4634–4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers H, Pernthaler J, Glockner FO, Amann R. (2000. b). Culturability and in situ abundance of pelagic bacteria from the North Sea. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 3044–3051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers H, Pernthaler J, Peplies J, Glockner FO, Gerdts G, Amann R. (2001). Isolation of novel pelagic bacteria from the German bight and their seasonal contributions to surface picoplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 5134–5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gende SM, Quinn TP, Willson MF. (2001). Consumption choice by bears feeding on salmon. Oecologia 127: 372–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German DP, Chacon SS, Allison SD. (2011). Substrate concentration and enzyme allocation can affect rates of microbial decomposition. Ecology 92: 1471–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González JM, Simo R, Massana R, Covert JS, Casamayor EO, Pedrós-Alió C et al. (2000). Bacterial community structure associated with a dimethylsulfoniopropionate-producing North Atlantic algal bloom. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 4237–4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossart H-P, Levold F, Allgaier M, Simon M, Brinkhoff T. (2005). Marine diatom species harbour distinct bacterial communities. Environ Microbiol 7: 860–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges JI. (1992). Global biogeochemical cycles: progress and problems. Mar Chem 39: 67–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao N, Herndl GJ, Hansell DA, Benner R, Kattner G, Wilhelm SW et al. (2010). Microbial production of recalcitrant dissolved organic matter: long-term carbon storage in the global ocean. Nat Rev Microbiol 8: 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch AL. (1985) The macroeconomics of bacterial growth. In: Fletcher M Floodgate GD (eds), Special Publications of the Society for General Microbiology. Academic Press: London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kujawinski EB. (2011). The impact of microbial metabolism on marine dissolved organic matter. Annu Rev Mar Sci 3: 567–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa M, Cottrell MT, Kirchman DL, Kaiser K, Medeiros PM, Tremblay L et al. (2013). Phylogenetic and structural response of heterotrophic bacteria to dissolved organic matter of different chemical composition in a continuous culture study. Environ Microbiol 16: 1668–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauro FM, McDougald D, Thomas T, Williams TJ, Egan S, Rice S et al. (2009). The genomic basis of trophic strategy in marine bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 15527–15533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima-Mendez G, Faust K, Henry N, Decelle J, Colin S, Carcillo F et al. (2015). Determinants of community structure in the global plankton interactome. Science 348: 1262073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manz W, Amann R, Ludwig W, Wagner M, Schleifer KH. (1992). Phylogenetic oligodeoxynucleotide probes for the major subclasses of proteobacteria: problems and solutions. Syst Appl Microbiol 15: 593–600. [Google Scholar]

- Manz W, Amann R, Ludwig W, Vancanneyt M, Schleifer K-H. (1996). Application of a suite of 16 S rRNA-specific oligonucleotide probes designed to investigate bacteria of the phylum cytophaga-flavobacter-bacteroides in the natural environment. Microbiology 142: 1097–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morana C, Sarmento H, Descy J-P, Gasol JM, Borges AV, Bouillon S et al. (2014). Production of dissolved organic matter by phytoplankton and its uptake by heterotrophic prokaryotes in large tropical lakes. Limnol Oceanogr 59: 1364–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Morris RM, Rappe MS, Connon SA, Vergin KL, Siebold WA, Carlson CA et al. (2002). SAR11 clade dominates ocean surface bacterioplankton communities. Nature 420: 806–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef A. (1997). Anwendung der in situ Einzelzell-Identifizierung von Bakterien zur Populationsanalyse in Komplexen Mikrobiellen Biozönosen. PhD thesis, Technische Universität München: Munich, Germany.

- Nelson CE, Carlson CA. (2012). Tracking differential incorporation of dissolved organic carbon types among diverse lineages of Sargasso Sea bacterioplankton. Environ Microbiol 14: 1500–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opsahl S, Benner R. (1997). Distribution and cycling of terrigenous dissolved organic matter in the ocean. Nature 386: 480–482. [Google Scholar]

- Paver SF, Hayek KR, Gano KA, Fagen JR, Brown CT, Davis-Richardson AG et al. (2013). Interactions between specific phytoplankton and bacteria affect lake bacterial community succession. Environ Microbiol 15: 2489–2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernthaler A, Pernthaler J, Amann R. (2004) Section 3 update: Sensitive multi-color fluorescence in situ hybridization for the identification of environmental microorganisms. In: Kowalchuk GA, Bruijn FJ, Head IM, Akkermans AD, Elsas JD (eds) Molecular Microbial Ecology Manual. Springer: Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp 2613–2627. [Google Scholar]

- Philippot L, Andersson SGE, Battin TJ, Prosser JI, Schimel JP, Whitman WB et al. (2010). The ecological coherence of high bacterial taxonomic ranks. Nat Rev Micro 8: 523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhassi J, Berman T. (2003). Differential growth response of colony-forming alpha- and gamma-proteobacteria in dilution culture and nutrient addition experiments from Lake Kinneret (Israel), the eastern Mediterranean Sea, and the Gulf of Eilat. Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 199–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhassi J, Sala MM, Havskum H, Peters F, Guadayol O, Malits A et al. (2004). Changes in bacterioplankton composition under different phytoplankton regimens. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 6753–6766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappé MS, Connon SA, Vergin KL, Giovannoni SJ. (2002). Cultivation of the ubiquitous SAR11 marine bacterioplankton clade. Nature 418: 630–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repeta DJ, Quan TM, Aluwihare LI, Accardi A. (2002). Chemical characterization of high molecular weight dissolved organic matter in fresh and marine waters. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 66: 955–962. [Google Scholar]

- Romera-Castillo C, Sarmento H, Álvarez-Salgado XA, Gasol JM, Marrasé C. (2010). Production of chromophoric dissolved organic matter by marine phytoplankton. Limnol Oceanogr 55: 446–454. [Google Scholar]

- Romera-Castillo C, Sarmento H, Alvarez-Salgado XA, Gasol JM, Marrase C. (2011). Net production and consumption of fluorescent colored dissolved organic matter by natural bacterial assemblages growing on marine phytoplankton exudates. Appl Environ Microbiol 77: 7490–7498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romera-Castillo C, Álvarez-Salgado XA, Galí M, Gasol JM, Marrasé C. (2013). Combined effect of light exposure and microbial activity on distinct dissolved organic matter pools. A seasonal field study in an oligotrophic coastal system (Blanes Bay, NW Mediterranean). Mar Chem 148: 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney-Varga JN, Giewat MW, Savin MC, Sood S, LeGresley M, Martin JL. (2005). Links between phytoplankton and bacterial community dynamics in a coastal marine environment. Microb Ecol 49: 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapp M, Schwaderer AS, Wiltshire KH, Hoppe HG, Gerdts G, Wichels A. (2007. a). Species-specific bacterial communities in the phycosphere of microalgae? Microbial Ecol 53: 683–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapp M, Wichels A, Gerdts G. (2007. b). Impacts of cultivation of marine diatoms on the associated bacterial community. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 3117–3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento H, Gasol JM. (2012). Use of phytoplankton-derived dissolved organic carbon by different types of bacterioplankton. Environ Microbiol 14: 2348–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento H, Romera-Castillo C, Lindh M, Pinhassi J, Sala MM, Gasol JM et al. (2013). Phytoplankton species-specific release of dissolved free amino acids and their selective consumption by bacteria. Limnol Oceanogr 58: 1123–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer H, Abbas B, Witte H, Muyzer G. (2002). Genetic diversity of 'satellite' bacteria present in cultures of marine diatoms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 42: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk D, Nohynek L, Rischer H. (2014). Algae-bacteria association inferred by 16 S rDNA similarity in established microalgae cultures. MicrobiologyOpen 3: 356–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele JA, Countway PD, Xia L, Vigil PD, Beman JM, Kim DY et al. (2011). Marine bacterial, archaeal and protistan association networks reveal ecological linkages. ISME J 5: 1414–1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R. (2012). Marine microbes see a sea of gradients. Science 338: 628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan BK, Tupper B, Sczyrba A, Lauro FM, Martinez-Garcia M, González JM et al. (2013). Prevalent genome streamlining and latitudinal divergence of planktonic bacteria in the surface ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 11463–11468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner G. (1993). Optimizing fluorescent in situ hybridization with ribosomal-rna-targeted oligonucleotide probes for flow cytometric identification of microorganisms. Cytometry 14: 136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE, Hall DJ. (1974). Optimal foraging and the size selection of prey by the bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus. Ecology 55: 1042–1052. [Google Scholar]