Abstract

Background

Previous research suggested that single gene expression might be correlated with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) survival. Therefore, we conducted a systematical analysis for AML prognostic gene expressions.

Methods

We performed a microarray-based analysis for correlations between gene expression and adult AML overall survival (OS) using datasets GSE12417 and GSE8970. Positive findings were validated in an independent cohort of 50 newly diagnosed, non-acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) AML patients by quantitative RT-PCR and survival analysis.

Results

Microarray-based analysis suggested that expression of eight genes was each associated with 1-year and 3-year AML OS in both GSE12417 and GSE8970 datasets (p < 0.05). Next, we validated our findings in an independent cohort of AML samples collected in our hospital. We found that ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2E1 (UBE2E1) expression was adversely correlated with AML survival (p = 0.04). Multivariable analysis showed that UBE2E1 high patients had a significant shorter OS and shorter progression-free survival after adjusting other known prognostic factors (p = 0.03). At last, we found that UBE2E1 expression was negatively correlated with patients’ response to induction chemotherapy (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that UBE2E1 expression was a novel prognostic factor in adult, non-APL AML patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13045-016-0356-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, UBE2E1, Prognosis

Background

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), characterized by expansion of malignant myeloid precursor cells in peripheral blood and bone marrow, is the most prevalent acute leukemia in adults [1]. Several AML prognostic factors have been reported, including patient age and cytogenetic features [2, 3]. Interestingly, Metzeler et al showed that high expression of lymphoid enhancer binding factor-1 (LEF1) is a favorable AML prognostic factor in non-acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) AML [4]. This study provided insights on prognostic single gene expression in AML. Therefore, we performed a systematical microarray-based analysis to search gene expression that correlates with AML overall survival (OS).

Methods

Microarray datasets download and analysis

We selected AML microarray datasets from Oncomine (www.oncomine.com). Our selection criteria included (i) microarray examining adult AML patient samples; (ii) array data and patient survival data were both published; (iii) microarray data quality; and (iv) microarray used affymetrix array platform. Based on those selection criteria, we used GSE12417 and GSE8970 datasets for our analysis [5, 6]. GSE12417 had 2 independent cohort of samples, which were examined by affymetrix platforms GPL570 and GPL96, respectively. Specifically, GSE12417-GPL96 dataset included 163 adult AML patient gene expression profiles, while GSE12417-GPL570 dataset included 79 adult AML patient gene expression profiles. The patients were previously untreated and received cytarabine-based intensive induction and consolidation chemotherapy in the trial [4, 5]. GSE8970 dataset used affymetrix platform GPL96. GSE8970-GPL96 dataset included 34 adult AML patient samples. The patients were pretreated with tipifarnib [6]. The stem cell transplantation status of those patients was not available. The same probe ID system was used in all above datasets, enabling results to be cross-compared. Gene expression profiles of above datasets were downloaded from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus database. Clinic information of those patients was downloaded from Oncomine.

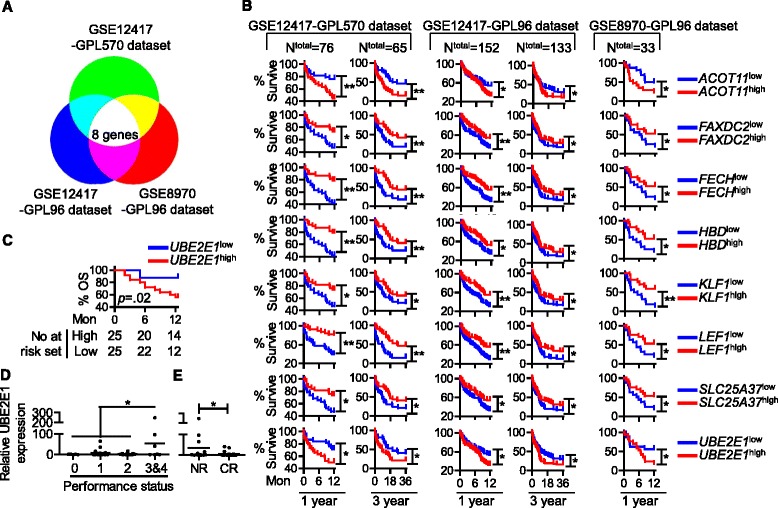

Our algorithm of prognostic genes identification was to identify prognostic genes in each microarray dataset and then find common prognostic genes across all tested datasets to avoid bias associated with single microarray dataset. In one dataset, single gene expression in each AML patient sample was presented by probe intensity. Patients with a probe intensity value above or below the median of all samples were categorized in probehigh and probelow groups, respectively. Survival (1 year and 3 years) of the two groups was compared by the Mantel-Cox test, and p < 0.05 was considered significant. Such calculation was repeated for all genes (probes) in the dataset by programming in R software to generate a list of prognostic genes. Common genes across both datasets were identified using the same probe ID (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

a Diagram showing the principal of microarray-based analysis. b OS according to high gene expression (genehigh, red) and low gene expression (genelow, blue), analyzed using microarray datasets GSE12417 and GSE8970. GSE12417 had two independent cohorts, examined by two microarray plateforms GPL570 and GPL96. c OS according to UBE2E1 high (red) and UBE2E1 low (blue) in validation cohort. d Relative UBE2E1 expression in patients with different performance status. e Relative UBE2E1 expression in patients with different responses to induction chemotherapy, no response (NR) vs. complete response (CR). (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01)

Patient samples

Our validation cohort had 50 newly diagnosed AML patient samples collected at West China Hospital, Sichuan University from 2010 to 2011. The inclusive criteria include (1) adult patients (age > 18); (2) patients with newly diagnosed AML except non-APL subtype; and (4) no chemotherapy was administered before the study. Bone marrow cell samples of the patients were collected as described previously [7]. All patients were treated based on the standard protocol including anthracyclines plus cytarabine. The study was reviewed and approved by the Central Ethics Committees of Institute of Hematology/Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and was filed in and permitted by the Ethics Committees of West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from patient bone marrow cells with RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The expression of target genes was analyzed by qPCR using SYBR green real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad). The expression of housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as an internal control. Primers used were described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Probes for quantitative RT-PCR

| Target gene | Primers | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Forward | GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG |

| Reverse | ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA | |

| LEF1 | Forward | TGCCAAATATGAATAACGACCCA |

| Reverse | GAGAAAAGTGCTCGTCACTGT | |

| FECH | Forward | GGAGATGTTCACGACTTCCTTC |

| Reverse | GAATGGTGCCAGCTTATTCTGA | |

| HBD | Forward | GAATGGTGCCAGCTTATTCTGA |

| Reverse | ACACCAGCCACCACCTTCTGAT | |

| ACOT11 | Forward | CATCGTGAACAATGCCTTCAAAC |

| Reverse | GTCCAGGACCACAAAGGTCAT | |

| KLF1 | Forward | GGTTGCGGCAAGAGCTACA |

| Reverse | GTCAGAGCGCGAAAAAGCAC | |

| FAXDC2 | Forward | ATTGGTGGTTGACACAACAGG |

| Reverse | AGAACTGTGCGGATAGACTGG | |

| SLC25A37 | Forward | AGAAAATCATGCGGACCGAAG |

| Reverse | TGGTGGTGGAAAACGTCATTTA | |

| UBE2E1 | Forward | CCTCCAAAGGTTACATTTCGGA |

| Reverse | GGTCGGCAGGATTACAGTCTG |

Statistical analysis

Patients’ characteristics between UBE2E1 high and UBE2E1 low groups were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. The association between UBE2E1 expression as well as other prognostic factors and patients’ survival was investigated using univariable Cox regression and multivariable logistic regression analysis. All above statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 22 software. Patient survival was graphed and analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software with Mantel-Cox test (a function of GraphPad Prism 5). A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Microarray-based analysis for AML prognostic gene expression

The microarray-based analysis showed that eight probes’ (genes’) expression was each associated with AML OS in all datasets, from 1-year survival to 3-year OS (Fig. 1b). These genes were ACOT11, FAXDC2, FECH, HBD, KLF1, LEF1, SLC25A37, and UBE2E1 (Table 2 for chi-square and p value). As shown in Fig. 1b, the expression of FAXDC2, FECH, HBD, KLF1, LEF1, and SLC25A37 was a favorable prognostic factor for AML, while high expression of UBE2E1 and ACOT11 was associated with poor OS (p < 0.05). Furthermore, we compared the target genes’ expression in normal BM vs. AML BM. At least in two tested microarray datasets GSE13159 and GSE1159, all target genes were aberrantly expressed in AML: AML patients had averagely increased ACOT11 and UBE2E1 gene expression, while the patients had lower expression of the other genes (Additional file 1: Figure S1). In addition, we conducted multivariable analyses of the microarray datasets. The results revealed that only UBE2E1, LEF1, and FECH1 were independent prognostic factors in AML, despite the impact of the patient age, FAB subtype as well as other prognostic factors (Table 3). Interestingly, among those three identified prognostic-related single genes, high expression of LEF1 has already been reported as a favorable prognostic factor in cytogenetically normal adult AML [4].

Table 2.

Microarray-based analysis for AML overall survival related gene expression

| GSE12417-GPL570 | GSE12417-GPL96 | GSE8970-GPL96 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year | 3-year | 1-year | 3-year | 1-year | |||||||

| Gene name | Probe ID | Chi-square | p value | Chi-square | p value | Chi-square | p value | Chi-square | p value | Chi-square | p value |

| ACOT11 | 214763_at | 6.941523 | 0.00842 | 11.8655 | 0.00057 | 3.88562 | 0.0487 | 4.72131 | 0.02979 | 4.03782 | 0.04449 |

| KLF1 | 210504_at | 5.748149 | 0.01651 | 4.25163 | 0.03921 | 4.10844 | 0.04267 | 9.61817 | 0.00193 | 5.14706 | 0.02329 |

| LEF1 | 221558_s_at | 14.72791 | 0.00012 | 13.5199 | 0.00024 | 7.77776 | 0.00529 | 11.0276 | 0.0009 | 5.14706 | 0.02329 |

| FECH | 203115_at | 11.52174 | 0.00069 | 9.90671 | 0.00165 | 7.00522 | 0.00813 | 10.0492 | 0.00152 | 5.14706 | 0.02329 |

| FAXDC2 | 220751_s_at | 5.786984 | 0.01615 | 7.59189 | 0.00586 | 4.01214 | 0.04517 | 7.41339 | 0.00647 | 5.14706 | 0.02329 |

| HBD | 206834_at | 11.87311 | 0.00057 | 7.12887 | 0.00759 | 4.42625 | 0.03539 | 6.57289 | 0.01035 | 5.14706 | 0.02329 |

| SLC25A37 | 221920_s_at | 5.786984 | 0.01615 | 5.01703 | 0.0251 | 4.59061 | 0.03215 | 6.62943 | 0.01003 | 5.14706 | 0.02329 |

| UBE2E1 | 212519_at | 4.114544 | 0.04252 | 4.50706 | 0.03376 | 6.25573 | 0.01238 | 5.73031 | 0.01667 | 4.03782 | 0.04449 |

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of target genes in microarray datasets

| GSE8970-GPL96 | GSE12417-GPL96 | GSE12417-GPL570 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | PFS | OS | OS | ||||||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | ||

| ACOT11 | ACOT11 expression, high vs. low | 0.658(0.296,1.462) | 0.304 | 0.636(0.287,1.405) | 0.263 | 1.445(0.970,2.154) | 0.07 | 1.809(1.009,3.243) | 0.047 |

| Age, per 10-year increase | 1.201(0.704,2.048) | 0.501 | 1.212(0.716,2.053) | 0.474 | 1.295(1.126,1.490) | <0.001 | 1.400(1.088,1.800) | 0.009 | |

| Sex, male vs. female | 1.326(0.473,3.717) | 0.592 | 1.369(0.488,3.838) | 0.551 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Prior myelodysplastic syndrome | 0.685(0.270,1.741) | 0.427 | 0.711(0.281,1.795) | 0.470 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Organ dysfunction | 1.162(0.490,2.753) | 0.733 | 1.253(0.536,2.930) | 0.603 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FAB subtype | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.879(0.773,0.999) | 0.048 | 0.956(0.778,1.174) | 0.667 | |

| FAXDC2 | FAXDC2 expression, high vs. low | 0.922(0.420.2.023) | 0.839 | 1(0.462,2.166) | >0.99 | 0.869(0.590,1.280) | 0.477 | 0.791(0.444,1.406) | 0.424 |

| Age, per 10-year increase | 1.185(0.685,2.051) | 0.544 | 1.182(0.688,2.030) | 0.545 | 1.278(1.114,1.466) | <0.001 | 1.382(1.074,1.778) | 0.012 | |

| Sex, male vs. female | 1.553(0.589,4.094) | 0.373 | 1.662(0.636,4.339) | 0.300 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Prior myelodysplastic syndrome | 0.681(0.265,1.753) | 0.426 | 0.698(0.273,1.783) | 0.452 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Organ dysfunction | 1.094(0.471,2.539) | 0.835 | 1.164(0.509,2.662) | 0.719 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FAB subtype | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.862(0.762,0.976) | 0.019 | 0.965(0.782,1.192) | 0.744 | |

| FECH | FECH expression, high vs. low | 0.363(0.149,0.883) | 0.025 | 0.390(0.163,0.934) | 0.034 | 0.566(0.382,0.838) | 0.005 | 0.424(0.235,0.764) | 0.004 |

| Age, per 10-year increase | 1.050(0.625,1.762) | 0.854 | 1.066(0.639,1.779) | 0.806 | 1.277(1.109,1.470) | 0.001 | 1.410(1.095,1.817) | 0.008 | |

| Sex, male vs. female | 1.932(0.734,5.089) | 0.183 | 1.988(0.763,5.181) | 0.160 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Prior myelodysplastic syndrome | 0.452(0.169,1.204) | 0.112 | 0.486(0.184,1.284) | 0.146 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Organ dysfunction | 1.684(0.653,4.343) | 0.281 | 1.781(0.697,4.554) | 0.228 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FAB subtype | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.855(0.757,0.967) | 0.013 | 0.978(0.790,1.210) | 0.837 | |

| HBD | HBD expression, high vs. low | 0.396(0.166,0.942) | 0.036 | 0.430(0.183,1.011) | 0.053 | 0.528(0.356,0.783) | 0.001 | 0.479(0.266,0.862) | 0.014 |

| Age, per 10-year increase | 1.015(0.594,1.732) | 0.957 | 1.035(0.610,1.756) | 0.898 | 1.294(1.126,1.487) | <0.001 | 1.363(1.070,1.738) | 0.012 | |

| Sex, male vs. female | 2.086(0.738,5.898) | 0.166 | 2.125(0.765,5.905) | 0.148 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Prior myelodysplastic syndrome | 0.595(0.221,1.605) | 0.305 | 0.627(0.236,1.666) | 0.349 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Organ dysfunction | 1.479(0.595,3.681) | 0.400 | 1.576(0.637,3.895) | 0.325 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FAB subtype | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.861(0.763,0.973) | 0.016 | 0.995(0.805,1.229) | 0.96 | |

| KLF1 | KLF1 expression, high vs. low | 0.457(0.208,1.000) | 0.050 | 0.429(0.198,0.927) | 0.031 | 0.560(0.379,0.829) | 0.004 | 0.581(0.325,1.037) | 0.066 |

| Age, per 10-year increase | 1.061(0.609,1.849) | 0.834 | 1.062(0.613,1.840) | 0.830 | 1.281(1.111,1.476) | 0.001 | 1.382(1.087,1.756) | 0.008 | |

| Sex, male vs. female | 1.928(0.693,5.362) | 0.209 | 2.064(0.742,5.738) | 0.165 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Prior myelodysplastic syndrome | 0.562(0.204,1.547) | 0.265 | 0.574(0.208,1.584) | 0.284 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Organ dysfunction | 1.184(0.492,2.845) | 0.706 | 1.259(0.530,2.994) | 0.602 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FAB subtype | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.853(0.755,0.963) | 0.011 | 0.976(0.791,1.204) | 0.821 | |

| LEF1 | LEF1 expression, high vs. low | 0.273(0.117,0.638) | 0.003 | 0.287(0.126,0.655) | 0.003 | 0.605(0.407,0.901) | 0.013 | 0.382(0.209,0.700) | 0.002 |

| Age, per 10-year increase | 1.328(0.789,2.236) | 0.285 | 1.342(0.802,2.245) | 0.263 | 1.259(1.094,1.449) | 0.001 | 1.423(1.099,1.843) | 0.007 | |

| Sex, male vs. female | 2.475(0.793,7.723) | 0.119 | 2.511(0.821,7.673) | 0.106 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Prior myelodysplastic syndrome | 0.554(0.208,1.479) | 0.239 | 0.595(0.225,1.573) | 0.295 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Organ dysfunction | 1.021(0.406,2.586) | 0.966 | 1.109(0.450,2.733) | 0.823 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FAB subtype | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.870(0.766,0.988) | 0.031 | 1.031(0.829,1.282) | 0.785 | |

| SLC25A37 | SLC25A37 expression, high vs. low | 0.312(0.117,0.827) | 0.019 | 0.294(0.111,0.782) | 0.014 | 0.540(0.360,0.808) | 0.003 | 0.616(0.345,1.101) | 0.102 |

| Age, per 10-year increase | 0.963(0.554,1.674) | 0.894 | 0.961(0.557,1.661) | 0.888 | 1.292(1.122,1.488) | <0.001 | 1.389(1.084,1.778) | 0.009 | |

| Sex, male vs. female | 1.431(0.548,3.737) | 0.465 | 1.474(0.568,3.828) | 0.425 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Prior myelodysplastic syndrome | 0.336(0.106,1.065) | 0.064 | 0.332(0.105,1.058) | 0.062 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Organ dysfunction | 1.377(0.573,3.310) | 0.475 | 1.494(0.629,3.552) | 0.363 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FAB subtype | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.897(0.792,1.015) | 0.086 | 0.983(0.796,1.214) | 0.872 | |

| UBE2E1 | UBE2E1 expression, high vs. low | 3.5(1.08,11.33) | 0.04 | 3.9(1.27,11.98) | 0.02 | 1.28(0.77,2.12) | 0.04 | 2.02(1.8,3.79) | 0.03 |

| Age, per 10-year increase | 1.04(0.96,1.13) | 0.32 | 1.04(0.96,1.12) | 0.35 | 1.02(1.00,1.04) | 0.03 | 1.36(1.07,1.73) | 0.01 | |

| Sex, male vs. female | 1.22(0.39,3.81) | 0.74 | 1.51(0.52,4.42) | 0.45 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Prior myelodysplastic syndrome | 0.83(0.25,2.72) | 0.75 | 0.88(0.29,2.71) | 0.83 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Organ dysfunction | 0.96(0.33,2.81) | 0.94 | 0.99(0.37,2.6) | 0.98 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FAB subtype | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.87(0.74,1.0) | 0.1 | 1.06(0.85,1.32) | 0.61 | |

NA not available

High expression of UBE2E1 is a poor prognostic factor in AML

We validated our findings in an independent cohort of 50 AML patients (median age 43). Target gene expression was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Based on median gene expression, we divided our patients into two study groups, genehigh and genelow groups. The survival analysis showed that out of eight genes identified by microarray studies, the expression of only one gene UBE2E1 (ubuquitin-conjugating enzyme E2E1) was associated with AML OS in our validation cohort, and this gene was one of the three genes with independent prognostic value on multivariable analysis in the training set. The UBE2E1 high group had a markedly shorter OS compared with UBE2E1 low group (p = 0.02; Fig. 1c). Expression of the other seven genes was not associated with AML prognosis in our study (p > 0.05; Additional file 1: Figure S2). We could not detect KLF1 expression in AML patient samples, although the qPCR primers for this gene were validated.

Next, we performed multivariable analysis to verify the prognostic significance of UBE2E1 expression in our validation cohort. The patient characteristics of UBE2E1 high and UBE2E1 low groups are shown in Table 4. No significant difference in patient characteristics, such as age, FAB subtypes, WBC count, BM blast percentages, gene mutations, was found between the two groups. We found no difference in patients’ treatment between those two groups (Table 5). UBE2E1 high patients had a short OS (p = 0.04) as well as a short progression-free survival (p = 0.03) compared with UBE2E1 low patients after adjusting for the impact of other prognostic factors including patient age, gender, performance status, and response to induction chemotherapy (Table 6).

Table 4.

Characteristic of AML patients in validation cohort

| Variable | UBE2E1 high n = 25 | UBE2E1 low n = 25 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age | 43.08 | 43.25 | 0.567 |

| Female, no. (%) | 10(40) | 13(52) | 0.395 |

| Secondary or treatment-related AML, no. (%) | 2(8) | 2(8) | >0.99 |

| FAB subtype , no. | 0.838 | ||

| M1 | 3 | 3 | |

| M2 | 10 | 12 | |

| M4 | 7 | 5 | |

| M5 | 1 | 3 | |

| M6 | 2 | 0 | |

| NA | 2 | 2 | |

| Median WBC, 109/L (range) | 6.83(0.3–244.38) | 23.88(0.68–366) | 0.289 |

| Median BM plasts, %, (range) | 49.5(11–94) | 65.5(22–90.5) | 0.175 |

| Median platelet count, 109/L (range) | 39(4–151) | 35.5(4–180) | 0.918 |

| CEBPA mutated, no. (%) | 2(8) | 5(20) | 0.179 |

| Missing date | 1 | 3 | |

| NPM1 mutated, no. (%) | 2(8) | 4(16) | 0.327 |

| Missing date | 1 | 3 | |

| IDH1 mutated, no. (%) | 0 | 0 | >0.99 |

| Missing date | 1 | 3 | |

| FLT3-TKD mutated, no. (%) | 0 | 1(4) | 0.296 |

| Missing date | 1 | 3 | |

| FLT3-ITD mutated, no. (%) | 0 | 2(4) | 0.149 |

| Missing date | 1 | 3 | |

| AML1/ETO mutated, no. (%) | 4(16) | 6(24) | 0.389 |

| Missing date | 1 | 3 | |

| C-KIT D816V mutated, no. (%) | 1(4) | 2(8) | 0.504 |

| Missing date | 1 | 3 | |

| CBEB-MYH11 mutated, no. (%) | 2(8) | 3(12) | 0.568 |

| Missing date | 1 | 3 |

Table 5.

Characteristic of AML patients treatment in validation cohort

| Variable | UBE2E1 high | UBE2E1 low | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment, no.(%) | 25(100) | 25(100) | 0.422 |

| CAG | 2(8) | 1(4) | |

| DA | 9(36) | 11(44) | |

| QA | 1(4) | 0 | |

| HAD | 1(4) | 0 | |

| IDA | 6(24) | 11(44) | |

| D-CAG | 2(8) | 1(4) | |

| Allo-HSCT | 0(0) | 0(0) |

Table 6.

Multivariable analysis in validation cohort

| OS | PFS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| UBE2E1 expression, high vs. low | 3.227(1.05,9.852) | 0.040 | 3.818(1.616,12.553) | 0.027 |

| Age, per 10-year increase | 1.666(1.112,2.498) | 0.013 | 1.536(1.02,2.313) | 0.040 |

| Sex, male vs. female | 0.628(0.214,1.84) | 0.396 | 0.559(0.183,1.71) | 0.308 |

| Performance status | 0.727(0.374,1.41) | 0.345 | 0.683(0.344,1.358) | 0.277 |

| Induction chemo-response | 1.472(0.845,2.566) | 0.172 | 1.51(0.853,2.672) | 0.157 |

UBE2E1 expression and its association with chemotherapy response

Finally, in our validation cohort, low UBE2E1 expression was associated with a better performance status in the patients (Fig. 1d; p < 0.05). We also found that UBE2E1 expression was associated with response to induction chemotherapy. Patients who had relatively higher UBE2E1 expression were more likely to achieve no response (NR) to chemotherapy while patients who had lower UBE2E1 expression were more likely to enter complete remission (CR) (Fig. 1e; p < 0.05). This result suggests that UBE2E1 expression may be a possible predictor for chemotherapy response in AML patients.

Discussion

In this study, we performed a genome-wide screening to identify gene expression that correlate with adult AML OS. The gene expression profiles (GEPs) from 2 independent datasets of patient samples were used in our analysis. The correlation of each gene expression and AML OS was calculated by a program coded by R software. Only gene identified with statistical significance in both datasets was considered as positive results for further test. By this strategy of analysis, we identified 8 AML prognostic genes. Next, we tested our findings using an independent cohort of 50 AML samples. Our result suggested that although several genes, such as HBD and ACOT11, had trend correlation, only one gene, UBE2E1, was statistically correlated with AML OS in our validation cohort. The negative findings of other 7 genes in our validation cohort might be caused by the relatively small number of patients. In addition, we noticed that the patients in microarray-testing cohort and our validation cohort had different ethnic backgrounds. Further studies might be necessary to draw a more confirmative conclusion.

Mounting evidence has shown that AML is highly heterogeneous and dynamic [8]. The heterogeneous entity of AML emerges from the disease genetic basis, leukemogenesis, pathophysiology, and prognosis. However, cluster of gene expression signature [5], or even single gene expression [4], has been shown to correlate with AML prognosis. Therefore, what is the interpretation of prognostic single gene expression, such as UBE2E1 and LEF1, in AML? We hypothesized that different subgroups of AML, with discrete driver mutations, might have similar epigenetic effectors’ upregulation/downregulation, which correlate with patient’s survival. We also hypothesized that in different prognosis-relevant AML subgroups, the effectors have patterned expression. To test these hypotheses, we performed another microarray-based analysis for UBE2E1 expression in AML with complex karyotype vs. normal karyotype, FLT3 mutation vs. wildtypeFLT3, and NPM1 mutation vs. wildtypeNPM1. We selected those genetic abnormalities because they have high frequency of occurrence in AML and correlate with the patient clinical outcome: patients with complex karyotype or FLT3 mutation had poor treatment outcome, while patients with NPM1 mutation had good treatment outcome [8]. As shown in Additional file 1: Table S1, complex karyotype or FLT3-mutated AML had relatively high UBE2E1 expression, compared with normal karyotype or wildtype FLT3 AML, respectively. NPM1-mutated AML had relatively low UBE2E1 expression. These preliminary findings might indicate that UBE2E1 have patterned expressions, which was well matched with AML classification despite of different genetic basis.

Protein ubiquitination was accomplished by sequential action of enzymes E1, E2, and E3. Specifically, E2 transferred E1-activated ubiquitin to E3, an ubiquitin ligase, and formed an isopeptide bond between ubiquitin and protein substrate. UBE2E1 was a member of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 class. Zhu et al. showed that UBE2E1 regulated HOX gene expression by ubiquitinating histones [9]. Thus, UBE2E1 might play a regulatory role in cell by selectively ubiquitinating target proteins. The function of UBE2E1 in cell signaling is still largely unknown. However, the regulation of UBE2E1 on HOX gene might be a key to understand the prognostic role of UBE2E1 in AML. HOX gene is a family of highly conserved homeodomain transcription factor genes [10]. There are 39 HOX genes, belonging to 4 gene clusters, in human. Previous work has shown that HOX genes are aberrantly expressed in AML [11, 12]. Animal study indicated that overexpression HOX gene, HOXA10 and HOXA9, promoted AML leukemogenesis [13, 14]. To identify potential UBE2E1 downstream HOX genes, we started with microarray datasets. We found co-expression of UBE2E1 with HOXA11 in AML. We also examined HOXA11 and UBE2E1 co-expression in our validation cohort (Additional file 1: Figure S3). Interestingly, a recent publication suggested that HOXA11 expression correlated with glioblastoma patient treatment responses and prognosis [15]. Thus, it is highly possible that UBE2E1 regulates AML chemoresistance through HOXA11.

In our study, we found co-expression of UBE2E1 with HOX family gene, HOXA11, in AML. Therefore, we hypothesized that UBE2E1 regulates HOXA11 gene expression in AML, and HOXA11 transcription factor level might be relevant to AML treatment resistance. We are actively conducting more mechanistic studies to demonstrate the role of UBE2E1 in AML.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we performed a genome-wide, microarray-based analysis for gene expressions that correlated with AML survival, and found 8 candidate genes. We further tested these genes in an independent validation cohort of 50 AML samples, and identified that UBE2E1 expression adversely correlated with AML prognosis.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Leukemia Tissue Bank of the Department of Hematology, West China Hospital for providing patient samples and Dr. Qing Yi of Cleveland Clinic for editing this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Public Health Grand Research Foundation (No.201202017) to T.L.; National Science Foundation of China (81470363), Sichuan University Faculty Start Fund, and Sichuan University Outstanding Young Scholar Award (2082604184223) to Y.Z.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Authors’ contributions

YQ and FR initiated this study. HL performed majority of the experiments. SY and YZ performed the bioinformatics analysis. TL and ZX designed and guided the patients’ clinical study. YD, JH, FW, DZ, LP, HZ, YW, and TN collected patient samples and performed the clinical treatments. YQ, FR, and YZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was reviewed and approved by the Central Ethics Committees of Institute of Hematology / Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and was filed in and permitted by the Ethics Committees of West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Abbreviations

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- CR

Complete remission

- GEP

Gene expression profile

- NR

No response

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression-free survival.

Additional file

Aberrant target gene expression in AML. AML patient samples microarray datasets GSE13159 and GSE1159 were downloaded from NCBI. Normal samples in those datasets were bone marrow cells or peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors. Target gene expression in normal samples vs. AML patient samples were plotted and compared by the Student’s t test (**p < 0.01). Figure S2. Target gene correlation with patient survival in validation cohort. Figure S3. Co-expression of UBE2E1 and HOXA11 in AML. Table S1. UBE2E1 expression in AML subgroups. (PPTX 202 kb)

Contributor Information

Yuhuan Zheng, Email: yuhuan_zheng@163.com.

Ting Liu, Email: liuting@scu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Thomas A, Murray T, Thun M. Cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:23–47. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estey EH. Prognostic factors in acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. 2001;15:670–2. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yohe S. Molecular genetic markers in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Med. 2015;4:460–78. doi: 10.3390/jcm4030460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metzeler KH, Heilmeier B, Edmaier KE, Rawat VP, Dufour A, Dohner K, Feuring-Buske M, Braess J, Spiekermann K, Buchner T, et al. High expression of lymphoid enhancer-binding factor-1 (LEF1) is a novel favorable prognostic factor in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:2118–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-411827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metzeler KH, Hummel M, Bloomfield CD, Spiekermann K, Braess J, Sauerland MC, Heinecke A, Radmacher M, Marcucci G, Whitman SP, et al. An 86-probe-set gene-expression signature predicts survival in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:4193–201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-134411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raponi M, Lancet JE, Fan H, Dossey L, Lee G, Gojo I, Feldman EJ, Gotlib J, Morris LE, Greenberg PL, et al. A 2-gene classifier for predicting response to the farnesyltransferase inhibitor tipifarnib in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:2589–96. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Y, Zheng Y, Li T, Wang Q, Qian J, Lu Y, Zhang M, Bi E, Yang M, Reu F, et al. Chemokines CCL2, 3, 14 stimulate macrophage bone marrow homing, proliferation, and polarization in multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:24218–29. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Roberts ND, Potter NE, Heuser M, Thol F, Bolli N, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2209–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu B, Zheng Y, Pham AD, Mandal SS, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Reinberg D. Monoubiquitination of human histone H2B: the factors involved and their roles in HOX gene regulation. Mol Cell. 2005;20:601–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alharbi RA, Pettengell R, Pandha HS, Morgan R. The role of HOX genes in normal hematopoiesis and acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2013;27:1000–8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eklund E. The role of Hox proteins in leukemogenesis: insights into key regulatory events in hematopoiesis. Crit Rev Oncog. 2011;16:65–76. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.v16.i1-2.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Braekeleer E, Douet-Guilbert N, Basinko A, Le Bris MJ, Morel F, De Braekeleer M. Hox gene dysregulation in acute myeloid leukemia. Future Oncol. 2014;10:475–95. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrence HJ, Helgason CD, Sauvageau G, Fong S, Izon DJ, Humphries RK, Largman C. Mice bearing a targeted interruption of the homeobox gene HOXA9 have defects in myeloid, erythroid, and lymphoid hematopoiesis. Blood. 1997;89:1922–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorsteinsdottir U, Sauvageau G, Hough MR, Dragowska W, Lansdorp PM, Lawrence HJ, Largman C, Humphries RK. Overexpression of HOXA10 in murine hematopoietic cells perturbs both myeloid and lymphoid differentiation and leads to acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:495–505. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.1.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.YB Se, SH Kim, JY Kim, JE Kim, YS Dho, JW Kim, YH Kim, HG Woo, SH Kang, HJ Kim, et al. Underexpression of HOXA11 is associated with treatment resistance and poor prognosis in glioblastoma. Cancer Res Treat. 2016. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.