Abstract

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century with far-reaching and enduring adverse consequences for health outcomes. Over 42 million children <5 years worldwide are estimated to be overweight (OW) or obese (OB), and if current trends continue, then an estimated 70 million children will be OW or OB by 2025. The purpose of this review was to focus on psychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial consequences of childhood obesity (OBy) to include a broad range of international studies. The aim was to establish what has recently changed in relation to the common psychological consequences associated with childhood OBy. A systematic search was conducted in MEDLINE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library for articles presenting information on the identification or prevention of psychiatric morbidity in childhood obesity. Relevant data were extracted and narratively reviewed. Findings established childhood OW/OBy was negatively associated with psychological comorbidities, such as depression, poorer perceived lower scores on health-related quality of life, emotional and behavioral disorders, and self-esteem during childhood. Evidence related to the association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and OBy remains unconvincing because of various findings from studies. OW children were more likely to experience multiple associated psychosocial problems than their healthy-weight peers, which may be adversely influenced by OBy stigma, teasing, and bullying. OBy stigma, teasing, and bullying are pervasive and can have serious consequences for emotional and physical health and performance. It remains unclear as to whether psychiatric disorders and psychological problems are a cause or a consequence of childhood obesity or whether common factors promote both obesity and psychiatric disturbances in susceptible children and adolescents. A cohesive and strategic approach to tackle this current obesity epidemic is necessary to combat this increasing trend which is compromising the health and well-being of the young generation and seriously impinging on resources and economic costs.

Keywords: pediatric obesity, psychological comorbidity, mental health, ADHD, depression, anxiety, obesity stigma, teasing, bullying

Introduction

Childhood obesity is one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century. Over 42 million children <5 years worldwide are estimated to be overweight (OW) or obese (OB).1,2 OW and obesity (OBy), an established problem in high-income countries, is also an increasing problem in low- to middle-income countries (Table 1). More alarmingly, the increasing rate of childhood OW and OBy in developing countries is now >30% higher than that in developed countries. If current trends continue, then an estimated 70 million children will be OW or OB by 2025, making this a leading health problem.2

Table 1.

Global incidence of overweight and obesity in childhood

| • Of the 42 million overweight children worldwide, ~31 million live in developing countries1 |

| • In the United States, childhood obesity incidence has more than doubled in children and quadrupled in adolescents in the past 30 years. One-third of the US children/adolescents in the general population are currently overweight/obese86,87 |

| • Overweight/obesity in children aged 11–13 years across 36 countries in WHO European region ranges from 5% to >25%88 |

| • Australia, with the sixth highest prevalence of the population being overweight or obese among OECD countries89, has ~25% of overweight children aged 2–16 years with 6% being classified as obese2,90 |

| • In the last 25 years, the number of overweight or obese children living in the African continent has surged from 5.4 million to 10.3 million. This means 25% of all overweight or obese preschool age children live in the WHO African regions1 |

Abbreviations: OECD, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; WHO, World Health Organization.

Childhood and adolescent OBy has far-reaching and enduring adverse consequences for health outcomes.3,4 In particular, the onset of psychiatric and psychological symptoms and disorders is more prevalent in OB children and young adults. Research has confirmed an association between childhood OW and OBy, psychiatric and psychological disorders, and onward detrimental effects on the psychosocial domain5–7 and overall quality of life (QoL).8,9 In turn, these can also compound their physical and medical health outcomes.3,4 Emerging research might strengthen the current body of knowledge in this area. Further review is required to explore the extent and implications of psychological comorbidities as well as identify important gaps for future research.

This review focuses on psychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial consequences of childhood OBy. It is the most recent review of this type and includes a broad range of studies involving numerous countries with varying methodologies. The aim was to establish what has recently changed in relation to the common psychological consequences associated with childhood OBy.

Methods

Data sources and searches

Three databases were searched, including MEDLINE (PubMed), Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. Search terms were developed with input from an subject expert librarian (Table 2). The search terms and strategy attempted to capture new information not included in previous reviews, including both prevention and treatment options, and findings from multiple countries. The full search was undertaken by one reviewer (JR). Then, another reviewer (LM) independently examined the titles and abstracts to identify suitable publications matching the selection criteria. Later, full texts were obtained for relevant articles and examined for inclusion in the final collection of review literature.

Table 2.

Complete list of search terms

| (childhood obesity or pediatric obesity or obese children or obese child) and (comorbidity or comorbidities or co-morbidity or co-morbidities) and (identification or diagnosis) and (prevention or treatment or treatments or therapy or therapies or intervention or interventions) and (psychiatric or psychological or cognitherapy or cognitive behavio?r therapy or motivational enhancement or antipsychotics or body image or body image disturbance or body dissatisfaction or body shape discontent or self-esteem or depression or anxiety or disordered eating or weight stigmatization or weight bias or bullying or stress or cognitive impairment or attention-deficit disorder or low health-related quality of life or self-perception or long-term effects or school performance) |

Study selection

All publications presenting information on the identification or prevention of psychiatric morbidity in childhood obesity were included. Articles for review were excluded if published before 2006, were unavailable in English, focused on medical/physiological outcomes or on obesity in adulthood (the cutoff age for adulthood varied and was determined by the authors of individual papers).

Preliminary search results

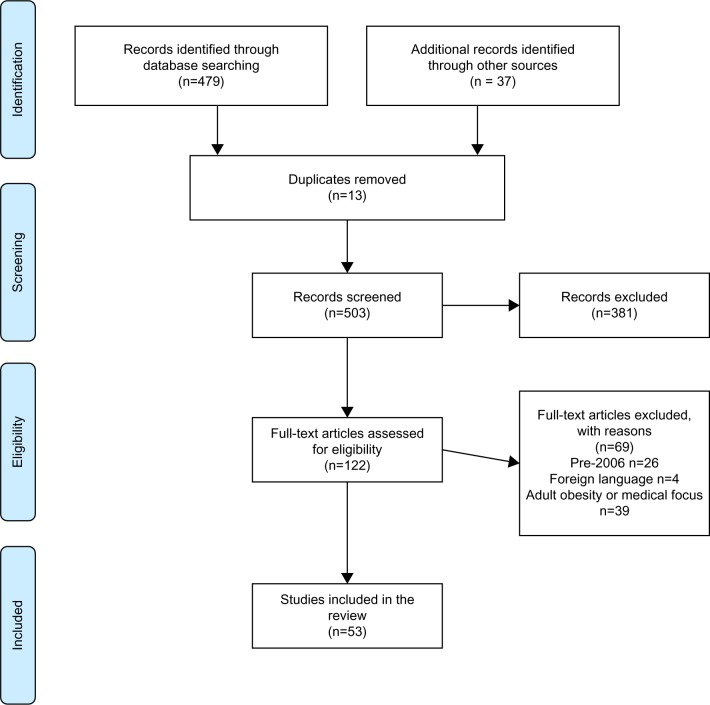

Databases were searched between June 13 and 17, 2016. Initial search results are presented in Figure 1. Of 53 studies, 16 explored depression and anxiety, 17 investigated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorders (of which one also explored depression and anxiety), and 30 focused on other psychological comorbidities (of which 9 also included depression, anxiety, and/or ADHD).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of search results.

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Results

The reviewed 53 studies are summarized in Tables 3–5 and are presented narratively below in relation to: 1) depression and anxiety, 2) ADHD, and 3) other psychological comorbidities including self-esteem, QoL, stigmatization, and eating disorders. Abbreviations for all outcome measures are detailed in Table 6.

Table 3.

Summary of depression and anxiety papers (by authors in alphabetical order) (n=16)

| Authors | Year | Study design | Age (years) | n | Population | Key measures | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al4 | 2006 | Prospective longitudinal 4 Waves between 1975 and 2003 | Wave1: 9–18 Wave2: 11–22 Wave3: 17–28 Wave4: 28–40 |

776 775 776 661 |

Community-based, US | BMI z-scores (age-sex centiles-CDCAP). DSM-III children/DSM-IV: anxiety/depressive disorders | Anxiety/depression were only associated with higher BMI z-scores in females |

| Anderson et al18 | 2007 | Prospective longitudinal 1983, 1985, 2003 | 12–17.99 | 701 | Community-based, US | BMI-OB (age-sex centiles-CDCAP) Diagnostic interview: MDD/anxiety disorder |

Females OB as adolescents possible at increased risk for depression or anxiety disorders |

| Anton et al19 | 2006 | Cross-sectional | 11–13 | 45 | Sixth-grade students, US | BMI OB (age–sex centiles–CDCAP) Behavioral measures SAPAC (activity/sedentary) CDI – depressed mood levels ChEAT – maladaptive eating attitudes |

Specific aspects of depression (ie, interpersonal problems/feelings of ineffectiveness) positively correlated with increased sedentary activity |

| Bell et al16 | 2011 | Cross-sectional | 6–13 | 283 | GAD (Growth and Development Study) | BMI z-scores (age–sex centiles–CDCAP) Structured medical interview: psychosocial symptoms, depression, anxiety + bullying |

Increased psychological symptoms reported in OW/OB individuals Increased teasing/bullying |

| Bell et al15 | 2007 | Cross-sectional Part of prospective “Growth and Development” (GAD) study | 6–13 | 177 n=73 n=53 n=51 |

OW/OB children seeking treatment Weight: Normal/OW/OW seeking treatment |

BMI z-scores (age–sex centiles–CDCAP) Structured medical interview: psychosocial symptoms, depression, anxiety + bullying | Increased depression with increased BMI z-score Proportion of children reporting bullying/teasing significantly increased with increasing BMI z-scores |

| Bjornelv et al20 | 2011 | Population-longitudinal | 13–18 | 8,090 | Young-HUNT-1 | BMI (international age/sex specific cutoffs) Physical/mental health questionnaire – eating problems, self-esteem, personality, anxiety/depression |

No sex differences: in psychological factors/weight problems Low self-esteem with OW/OB but no reports of anxiety/depression/emotional or personality traits |

| Eschenbeck et al17 | 2009 | Community-based | 6–14 | 156,948 | German national health insurance data | ICD-10: physician diagnosis of OB/psychiatric disorders (ie, external, eg, ADHD, conduct issues; internal, eg, depression/anxiety) | OB significantly associated external and internal disorders Increased OR higher in OB girls for both external and internal disorders No gender differences in OB/conduct Older OB children (12–14 years) increased OR of internal disorders |

| Gibson et al21 | 2008 | Cross-sectional | 8–13 | 262 | Population-based: Children: healthy weight (n= 158) OW (n=77) OB (n=27) |

BMIz-scores, (age–sex centiles–CDCAP) 118 self-report questionnaire: depression, QoL, self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, eating disorder, peer relationships, behavioral/emotional problems |

Increased BMI z-score associated with increasing levels of psychosocial distress significantly correlated with depression Interaction between increased BMI z-score and gender - girls having a significantly stronger increase in depression than boys |

| Goldstein et al11 | 2008 | Clinical-cohort | 7–17 | 348 | Diagnosed (bipolar disorder, BP), US | BMI (IOTF criteria). K-SADS-PL interview (child/parent) – comorbid diagnoses (eg, anxiety, conduct), clinical characteristics (eg, psychoses), mood symptoms/suicide tendencies SES |

OW/OB adolescents with BP: Prevalence modestly greater than general population May be associated with increased psychiatric burden |

| Hoare et al22 | 2014 | Cross-sectional | 11–14 | 800 | Schoolchildren, Australia | BMI (WHO criteria). Behaviors: ABAKQ for activity levels and diet. (PA measured against Australian Govt PA guidelines for adolescents; Diet using WHO guidelines-daily intake) SMFQ-D-Depressive symptomology/anxiety/behavior using SMFQ-D (high internal consistency). |

Higher odds of depressive symptoms in OW/OB males before/after adjusting for covariates (than normal-weight adolescents) PA did not show any association with OW/OB |

| Koch et al23 | 2008 | Cross-sectional/longitudinal | 1 (n=11,082) 2–3 (n=8,805) 5–6 (n=7,443) |

n=5,221 (at all age-points) | Swedish families All babies in Southeast Sweden project (ABIS) | BMI: obese/non-obese (IOTF criteria). Psychological-stress domains (family report): SPSQ. |

Children reporting stress (≥2 domains) have significantly higher OR for OB (cross-sectional and longitudinal) Psychological stress (in family) possible contributing factor for childhood OB |

| Marks et al5 | 2009 | Retrospective medical record review | 4–21 | 230 Weight only for 121 |

Individuals (psychiatric consultation), US | BMI (CNRC guidelines). Major psychiatric diagnosis recorded: BP, ADHD, Depression |

OW/OB children: No statistically significant difference in rates of most common psychiatric disorders (ie, ADHD, BP disorder/depression) Rates of depression/BP disorder higher than normal/UW children Trend to increasing rates of conduct disorders |

| Phillips et al24 | 2012 | Cohort | 6–17 | 249 | OB youths treatment clinic, US | BMI (age-sex centiles-CDCAP). Self-report questionnaire (children/parents): CDI PedQoL SAS |

Extremely OB youth – higher rates across all psychosocial variables with poorer QoL OB girls scored worse than OB boys only on social anxiety (SAS) |

| Roth et al12 | 2008 | Family-based behavioral/treatment | 8–12 | 59 | Clinical referral OB mother + children, Switzerland | BMI (IOTF criteria) SES Mental disorders: Mothers – Assessment of mental disorders – DSM-IV/BAI DSM-IV disorders in children (parent/child) Maternal BED – assessed DSM-IV EDE/BAI/BDI (by mother) Child completed: CDI, STAIc for children CBCL |

OB children (clinical sample): Higher rate of mental disorder compared with nonclinical Significant higher risk of internalizing problems (depression/anxiety) if mother had mental health disorders Mothers (BED) – children with increased probability of mental disorder Maternal anxiety/depression associated with child’s anxiety/depression Maternal BAI, child's total competence via CBCL were significant predictors of child well-being |

| Sanderson et al13 | 2011 | Cohort: 1985+20years |

7–15 26–36 |

2,243 | National Australian School survey | BMI z-scores (age/sex specific ≥85th centile; OB ≥30) Diagnosed mental disorders-—DSM-IV |

OW/OB in childhood associated with increased risk of diagnosed mood disorder (adulthood, OW girls becoming OB women) |

| van Wijnen et al25 | 2010 | Population-based | 13–14/15–16 | 21,730 | Dutch Schoolchildren | BMI (self-reported only)– (IOTF criteria) Internet questionnaire: MHI-5 | OB boys/girls more likely to be psychologically unhealthy/reported more suicide attempts/thoughts Moderately OW/UW girls more likely to report suicide thoughts/attempts but to a lesser extent than OB adolescents |

Note: Refer to Table 6 for abbreviations and outcome measures.

Table 4.

Summary of ADHD papers included in the review (by authors in alphabetical order) (n= 17)

| Authors | Year | Study design | Age (years) | n | Population | Key measures | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al30 | 2010 | Longitudinal | 2–12 | 1,237 | Child/youth development (SECCYD) | BMI (age–sex centiles–CDCAP) CBCL-23: externalizing behaviors (emotional/behavioral difficulties) |

Externalizing behaviors problems associated with higher BMI and OB (as young as 24 months) Behaviors associated (modest effect) in early childhood with weight/status in elementary school years |

| Anderson et al29 | 2006 | Prospective/longitudinal 1983 – T1 1985/6 – T2 |

T1 : ~9–16 T2: ~11–20 |

655 | General population (childhood-adulthood) | BMI z-scores (age–sex centiles–CDCAP) Diagnosis DISC-IV for children for ADHD, defiant disorder/conduct disorder | Subjects with ADHD have higher mean BMI z-scores (all ages) compared with subjects with no disruptive disorder Disruptive disorders associated with elevated weight-status (childhood into adulthood) Possible associations between behavior disorders and increased weight begin early in childhood - possible lifelong health effects |

| Byrd et al38 | 2013 | Survey (cohort: 2001–2004) | 8–15 | 3,050 | US children | BMI (≥percentile of US reference) ADHD status defined from Dl (DISC-V1) parent report Medication classification: ADHD medication/ADHD unmedicated |

Males (medication) had lower odds of OB than males without ADHD Unmedicated males (ADHD) as likely as males (no ADHD) to be OB No difference in odds of OB in females (medication for ADHD) did not differ statistically from females (no ADHD) Females (ADHD, no medication) had odds of OB 1.54× females without ADHD (not statistically significant) |

| Cortese et al33 | 2007 | Cross-sectional | 12–17 | 99 | Severely OB adolescents, France | OW >97th percentile (national BMI charts) Assessed pediatrician: Eating behaviors: Bulimic Inventory BDI, STAI: depression/anxiety CPRS: ADHD symptoms Tanner stages: puberty |

OB significantly associated (ADHD) symptoms (after controlling for depressive/anxiety) ADHD symptom/bulimic behaviors associated in OB adolescents may be accounted for by impulsivity/inattention rather than hyperactivity |

| Duarte et al31 | 2010 | Prospective/population-based (national) Recruited – R Assessed – A | R: 8 A: 18–23 |

2,209 | Military examination records, boys, Finland | BMI (military records). Child mental health (8 years) assessed through 3 sources: parents, teachers, and children Parent–teacher – psychopathy using Rutter scale: conduct, hyperkinetic (related to hyperactivity, inattentive behavior, etc) and emotional domains CDI: depression |

Childhood conduct problems (disobedience/defiance/aggression/cruelty to others/stealing/lying/destruction of property) prospectively associated with OW/OB young adults |

| Dubnov-Raz et al34 | 2011 | Cross-sectional Medical records analysis | 6–16 | 275 | Diagnosed ADHD treated (methylphenidate, per guidelines) with no neurological comorbidities, confirmed healthy controls, Israel | BMI, z-scores (OW as ≥85th percentile, OB as ≥95th percentile growth charts, CDCAP) Diagnosis – DSM-IV-TR Medication or no medication |

OW/OB prevalence was lower in ADHD-treated group compared with healthy controls, similar to national estimates Methylphenidate treatment did not significantly alter OW status |

| Erhart et al35 | 2012 | Cross-sectional/community-based survey | 11–17 | 2,863 | German parents/children | BMI (national age/sex-specific referencevalues) Diagnosis: DSMMD-based German ADHD scale |

Rate of ADHD significantly higher for OB than normal/UW children. OW/OB children 2× likely for ADHD diagnosis |

| Graziano et al39 | 2012 | Cohort | 4.5–18 | 80 | ADHD (diagnosed and clinical confirmation), hospital clinic, US | BMI, z-scores (age-sex centiles-CDCAP) ADHD: DSM-IV for diagnosis Treatment history: internalizing, hyperactivity/impulsivity/learning problems; externalizing factors – defiance, aggression, peer relations CPRS |

Children (ADHD): Performing poorly on neuropsychological battery had higher BMI z-scores and more likely to be classified as OW/OB compared with children with ADHD performing better on tests On stimulant medication, had lower BMI z-score EF more impaired and co-occurring weight problems |

| Khalife et al32 | 2014 | Prospective/Postal/questionnaire | 7–8 16 |

8,106 6,934 |

1986 birth-cohort, Finland | BMI (OB defined, IOTF cutoff points) Age 7–8: ADHD/CD symptoms (teacher)/Normal Behavior Scale, BMI/PA (parents) Age 16: ADHD symptoms (parents/SWAN)/PA index of binge eating (self) |

Children (ADHD/CD symptom) increased risk of OB and physically inactive adolescents PA may be beneficial for behavior problems/OB High comorbidity between inattention-hyperactivity/CD symptoms Variables significantly associated over-time until 16 years, for BMI/inattention symptoms 16 years slight negative association between BMI/PA BMI/eating-related |

| Kim et al36 | 2011 | Cross-sectional national survey | 6–17 | 66,707 | US children | BMI (as ≥95th percentile growth charts, CDCAP) Integrated telephone survey with parents (US Department of Health and Human Services) ADHD (assessed as parental response to ADHD questions) Depression/anxiety |

OB prevalence higher among children with ADHD ADHD medication had protection effect against weight gain Odds of being OB higher in girls than boys in nonmedicated ADHD compared with medicated ADHD Only health behaviors (sports and not sleeping) associated with OB in boys with ADHD (on medication) |

| *Marks et al5 | 2009 | Retrospective medical record review | 4–21 | 230 Weight only for 121 |

Individuals (psychiatric consultation), US | BMI (CNRC guidelines) Major psychiatric diagnosis recorded: BP, ADHD, depression |

OW/OB children No statistically significant difference in rates of most common psychiatric disorders (ie ADHD, BP disorder/depression) Rates of depression/BP disorder higher than normal/UW children Trend to increasing rates of conduct disorders |

| Pauli-Pott et al42 | 2014 | Documentary analysis | 6–12 | 360 | ADHD, ODD, CD, or adjustment disorder (n=257) and control group with adjustment disorder (n=103), Germany | BMI (OB classified ≥97th percentile national reference data) ICD-10: diagnosis disturbances of activity and attention, and hyperkinetic conduct disorder |

Nonsignificant links between ADHD/BMI-SDS or obesity Children with ODD/CD had highest body weight and highest rate of OB irrespective of ADHD diagnosis No independent link between ADHD and OB |

| Racicka et al43 | 2015 | Documentary analysis | 7–18 | 408 | ADHD patients, Poland | BMI (age/sex-growth references, Polish population) ADHD: diagnosis by child psychiatrists using DSM-IV |

Significantly higher frequency of OW/OB patients with ADHD than general population Higher incidence of OB with comorbidities of adjustment disorder |

| Rojo et al40 | 2006 | Community study | 13–15 | 35,403 | Obese adolescents | Self-reported (study limitation): BMI (OW 90%–97%; OB >97th percentile) SDQ ADHD characteristics, conduct, hyperactivity Depression/anxiety |

Slight increase only in comorbidity of ADHD characteristics in OB adolescents |

| Waring et al37 | 2008 | Cross-sectional national survey | 5–17 | 62,887 | ADHD (2004 national child health survey– using SLAITS), US | BMI (defined percentile growth charts, CDCAP) Diagnosis ADHD – trained interviewers Medication/no medication |

Children (ADHD) not using medication had 1.5× odds of being OW Children/adolescents (ADHD) on medication had 1.6× odds of being UW compared with children/adolescents without diagnosis |

| White et al44 | 2012 | Cohort-secondary analysis | 5/10/30 | > 12,400 | UK, 1970s/birth-cohort study | BMI (UK standards) Behavior over 5–10 years: RPS CPRS SDC Ml |

General psychological problems consistently associated in childhood particularly hyperactivity and attention problem with adult OB Further associations with disruptive behavior tapping into conduct problems/impulsivity/hyperactivity OB associated with persistent psychological problems across childhood (problems: early childhood at greater risk) No evidence: maternal psychological problems associated with OB risk in offspring |

| Yang et al41 | 2013 | Cohort | 6–16 | 158 | ADHD children (meeting DSM-IV criteria), People's Republic of China | BMI, z-scores (NGRCCA) Diagnosed ADHD, Dl CPTRS Physical assessment, eg, pubertal development |

Increased incidence of OB children with ADHD (higher in general population) Children (combined ADHD/onset of puberty) at higher risk of becoming OW/OB |

Table 5.

Summary of papers included in the review related to self-esteem, HRQoL, conduct, stigmatization, and eating disorders (by authors in alphabetical order) (n = 30)

| Authors | Year | Study design | Age (years) | n | Population | Key measures | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Bell et al16 | 2011 | Cross-sectional | 6–13 | 283 | Growth and Development (GAD) Study | BMI, z-score (age-sex centiles, CDCAP) Structured medical interview: psychosocial symptoms, depression, anxiety + bullying | OW/OB individuals: Increased psychological symptoms reported Increased teasing/bullying |

| *Bell et al15 | 2007 | Cross-sectional Part of prospective GAD study | 6–13 | 177 n=73 n=53 n=51 |

OW/OB children seeking-treatment Weight: Normal/OW/OW seeking treatment |

BMI, z-score (age-sex centiles, CDCAP) Structured medical interview: psychosocial symptoms, depression, anxiety + bullying | Increasing BMI, z-scores: Increased depression Proportion of children reporting bullying/teasing significantly increased |

| *Bjornelv et al20 | 2011 | Population, longitudinal | 13–18 | 8,090 | Young-HUNT-1 | BMI (international age/sex-specific cutoffs) Physical/mental health questionnaire: eating problems, self-esteem, personality, anxiety/depression | No sex differences: in psychological factors/weight problems Low self-esteem with OW/OB but no reports of anxiety/depression/emotional or personality traits |

| Bolton et al55 | 2014 | Cohort | 11–19.6 | 1,583 | Schoolchildren, Victoria, Australia | BMI (WHO reference data) Self-reported: AQoL-6D |

Lower HRQoL: Females compared to males Older compared to younger adolescents OW females compared to healthy-weight females |

| *Duarte et al31 | 2010 | Prospective/population-based (national) Recruited –R Assessed – A |

R: 8 A: 18–23 |

2,209 | Military examination records, boys, Finland | BMI (military records). Child mental health (8 years) assessed through 3 sources: parents, teachers, and children Parent-teacher: psychopathy using Rutter scale for: conduct, hyperkinetic (related to hyperactivity, inattentive behavior, etc) and emotional domains CDI (self-report): depression | Childhood conduct problems (disobedience/defiance/aggression/cruelty to others/stealing/lying/and destruction of property) prospectively associated with OW/OB young adults |

| *Eschenbeck et al17 | 2009 | Community-based | 6–14 | 156,948 | German national health insurance data | ICD-10: physician diagnosis of OB/psychiatric disorders (ie, external, eg, ADHD, conduct issues; internal, eg, depression/anxiety) | OB significantly associated external and internal disorders Increased OR higher in OB girls for both external and internal disorders No gender differences in OB/conduct Older OB children (12–14 years) increased OR of internal disorders |

| Franklin et al49 | 2006 | Cross-sectional | 9–13 | 2,749 | Schoolchildren (Australia) | Height/weight (BMI) Self-perception profile for children: Measure of body shape perception |

OW/OB children reported significantly poorer physical appearance, global self-worth |

| Gerke et al56 | 2013 | Cohort | 11–17 | 92 | OB African-Americans seeking treatment (TEENS) Criteria: ≥95th BMI percentiles for age/sex |

Personal/family information: POTS–teasing DHMS–daily hassles Coopersmith SEI, self-esteem CDI-depression ChEDE-Q, eating disorders |

Daily hassles, teasing, upset about teasing, depressive symptoms and self-esteem were all significantly correlated with eating pathology |

| *Gibson et al21 | 2008 | Cross-sectional | 8–13 | 262 | Population-based: children: healthy weight (n=158) OW (n=77) OB (n=27) |

BMI (z-scores), (age-sex centiles, CDCAP). 118 self-report questionnaire: depression, QoL, self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, eating disorder, peer relationships, behavioral/emotional problems |

Increase BMI z-score associated with increasing levels of psychosocial distress significantly correlated with depression Interaction between increased BMI z-score; and sex: girls having a significantly stronger increase in depression than boys |

| Guerdijkova et al64 | 2007 | Medical documentary analysis | <18 | 44 obese children |

Child/adult weight-management program, US 113 including 69 OB adults | BMI (NIH guidelines), weight history Diagnosis using SCI for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders CGI MDQ BDI |

Irrespective of age, very high prevalence rates of mood disorders Significantly higher lifetime prevalence of bulimia nervosa in weight-loss seeking patients with childhood OB onset compared with adult-onset OB |

| Halfon et al50 | 2013 | Cross-sectional National survey |

10–17 | 41,976–43,297 | Population-based, US | BMI (%age/sex 85th to <95th; ≥95th percentiles) Parent report Comorbid health issues (physical/psychological), Behavioral problem Index – ADHD, conduct issues (including school-related) |

OW/OB associated with poorer health status, lower emotional functioning, and school-related problems Greater weight associated with higher rates of ADHD, conduct disorders OB children with ADHD strong association (not taking stimulant medications) No associations for children taking stimulants Childhood OW with risk factors for development of psychosocial problems, including weight-based teasing, social stigmatization/peer rejection |

| Jansen et al51 | 2013 | Cross-sectional Longitudinal | Wave1: 4–5 Wave2: 10–1 1 |

3,898 | Australian children | BMI (IOTF cutoff points) PedQol Covariates, SAS, age |

High BMI, related to poorer HRQoL in late childhood Unique findings, this emerges in 6–7 years |

| Johnston et al57 | 2011 | Clinical evaluation trial | 6–18 | 48 | Treatment-seeking cohort: OB children, 10-week weight loss program + parent/s, US | BMI (age-sex centiles, CDCAP) Parental report Comorbidity psychiatric conditions: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorders, anxiety, depression and conduct disorder. |

Overall, significant reduction in BMI z-score: especially severely obese and children with comorbidity |

| *Khalife et al32 | 2014 | Prospective/postal/questionnaire | 7–8 16 |

8,106 6,934 |

1986 birth-cohort, Finland | BMI (OB defined, IOTF cutoff points) Age 7–8: ADHD/CD symptoms (teacher)/Normal Behavior Scale, BMI/PA (parents) Age 16: ADHD symptoms (parents/SWAN)/PA index of binge eating (self) |

Children with ADHD/CD symptoms, increased risk of OB and physically inactive adolescents PA may be beneficial for behavior problems/OB High comorbidity between inattention hyperactivity/CD symptoms Variables significantly associated over time until 16 years, for BMI/inattention symptoms 16 years, slight negative association between BMI/PA BMI/eating-related |

| Lebow et al65 | 2015 | Retrospective-cohort Medical record analysis |

10–20 | 179 | OW/OB treatment-seeking adolescents (diagnosed restrictive-eating disorders) | BMI (age-sex centiles, CDCAP). Clinical history (patient + parent) EDE-Q. |

36% adolescents (for treatment for a restrictive-eating disorder) had weight history >85th BMI percentile |

| Madowitz et al58 | 2012 | Cohort | 8–12 | 79 | Obese parent–child pairs referred to family-based treatment | BMI UWCBs: weight-related teasing, especially by other children Psychosocial measures |

OB children: Teased by other children having significantly higher levels of depression Are five times more likely to engage in UWCBs Children bothered by peer teasing by peers had significantly higher levels of depression Frequency of weight-related teasing significantly associated with depression Number of teasing sources (significantly associated with depression) No significant relationships between familial teasing/depression or UWCBs |

| ^Marks et al5 | 2009 | Retrospective medical record – review | 4–21 | 230 Weight only for 121 |

Individuals (psychiatric consultation), US | BMI (CNRC guidelines). Major psychiatric diagnosis recorded: BP, ADHD, depression |

OW/OB children: No statistically significant difference in rates of most common psychiatric disorders (ie, ADHD, BP disorder/depression) Rates of depression/BP disorder higher than normal/UW children Trend to increasing rates of conduct disorders |

| Neumark-Sztainer et al46 | 2007 | Longitudinal, survey | Mean age:-12.8 (T1: 1999), 17.2 (T2: 2004) | 2,516 | Adolescents (project EAT) | Weight status: (guidelines for cutoff criteria) Socio-environmental Body image/weight concerns Psychological well-being Depressive symptoms nutritional knowledge/attitudes Behavioral factors Weight-control practices |

Weight-specific socio-environmental, personal, and behavioral variables are strong and consistent predictors of OW status, binge eating/extreme weight-control behaviors in adolescence |

| *Phillips et al24 | 2012 | Cohort | 6–17 | 249 | OB youths, treatment clinic, US | BMI (age–sex centiles–CDCAP) Self-report questionnaire (children/parents): CDI PedQoL SAS |

Extremely OB youth, higher rates across all psychosocial variables with poorer QoL OB girls scored worse than OB boys only on social anxiety (SAS) |

| Quinlan et al59 | 2009 | Cohort study | 12–18 | 96 | Longitudinal weight loss program over summer camp, US | BMI (national cutoff criteria) Self-esteem: Rosenberg Scale Body esteem: body esteem scale Depression: centre for epidemiological studies depressions scale Antifat attitude Feelings/concerns Perceptions of teasing scale Participation/social involvement,camp staff Body concern |

More frequent and upsetting weight-related teasing experiences associated with worse psychological functioning Adolescents most distressed by weight-related teasing exhibited lower self-esteem and higher depressive symptoms Competence-related teasing associated with more worries about weight, greater depressive symptoms, and more negative anti-fat attitudes Weight-related teasing associated with lower levels of social involvement for heavier adolescents |

| Sawyer et al60 | 2011 | Cohort | 4–5 8–9 |

3,363 | Longitudinal study of Australian children | BMI (IOTF cutoff points) Mental health: SDQ completed by parents/teachers PedQoL |

>BMI in 4–5 years higher – likelihood of peer problems/teacher reports of emotional issues (8–9 years) |

| Sawyer et al52 | 2006 | Cross-sectional | 4–5 | 4,983 | Longitudinal study of Australian children Random assignment | BMI (IOTF cutoff points) Mental health | OB children had more peer/conduct problems |

| Taner et al53 | 2009 | Cross-sectional | 7–16 | 54 | Obese children, Turkey | Diagnosed OB Psychiatric disorders: DSM-IV-TR Clinical interview, K-SADS-PL |

50% children/adolescents had comorbid psychiatric disorders Depression/sociophobia, two most common reported |

| Taylor et al54 | 2012 | Cross-sectional | 7–11 | 158 | Primary children, Australia (and primary caregiver) | BMI (IOTF cutoff points) Child: Authoritative Parenting Index Self-esteem (self descriptive) Child body image Parent covariates, body dissatisfaction and depression |

Increasing BMI negatively associated with self-esteem Child weight associated with negative psychological outcomes in young, non-treatment-seeking children Larger BMI negatively associated with child self-esteem and positively associated with child body dissatisfaction Parental responsiveness positively associated with child self-esteem Parenting not associated with child body dissatisfaction Higher child BMI associated with higher body dissatisfaction and lower self-esteem in a young, non-treatment-seeking sample |

| Wake et al48 | 2013 | Cross-sectional/longitudinal | 2–3 4–5 6–7 8–12 13–18 |

4,606 4,983 4,464 1,541 928 |

Two Australian populations HOYVS 2000–2006 | BMI (IOTF cutoff points) Parent/self-report: psychosocial/mental health Special health care needs |

Normal weight deviations associated with health differences (vary by morbidity/age) Promoting normal weight is central to improving health/well-being of young and with later-life lower risk for disease |

| Wake et al47 | 2010 | Cross-sectional School-based/longitudinal |

8.4–15.8 | 923/parents | HOYVS (1997, 2000, 2005): n=24 | BMI (IOTF cutoff points) SDQ PedQoL Parent/self-report: psychosocial/mental health Special health care needs |

OW/OB adolescents more likely to have poorer health/but not more likely to report specific health issues Morbidity mainly associated with concurrent rather than earlier OW/OB |

| Walders-Abramson et al61 | 2013 | Cohort | 11–18 | 166 | OB adolescents ≥95th percentile for age/sex (+1 or more metabolic syndrome), endocrinology clinic, US | BMI percentiles (using 99th percentile, extreme/morbid OB) SDQ |

Meet criteria for extreme OB alone were more predictive of psychological difficulties Degree of OB more relevant than number of associated comorbidities (psychological health) |

| Wille et al62 | 2010 | Multicentre, clinical | 8–16 | 1,916 | OW/OB children seeking treatment (patients) (Germany) | BMI (national standards, Germany age/sex-specific >90th percentile or >97th). Demographics HRQoL KIDSCREEN-27 KIDSCREEN-52 KINDL |

Presence of differences in HRQoL regarding sex, age, treatment modality, and treatment-seeking OW/OB patients Marked reduction in HRQoL, eg, impaired self-perception/physical well-being No change in KIDSCREEN-27 peer-dimension reports |

| Zeller et al66 | 2006 | Retrospective analysis, clinical data | 10–18 | 33 | Extremely morbidly obese (seeking treatment/bariatric surgery) | Child: PedQoL, HRQoL BDI Mother: PedQoL-parent-proxy CDI checklist |

Daily life for extreme OB adolescents (seeking treatment) is globally and severely impaired Some of these extreme OB adolescents demonstrated clinically significant levels of depressive symptomatology |

| Zeller & Modi 200663 | 2006 | Clinical cohort Mean =12.7 |

8–18 | 166 obese youth | 70% females, 57% African-American pediatric weight management program | BMI (≥95th percentile) SES PedQoL-HRQoL (Parent-proxy). Youth completed: CDI PedQoL Perceived Social Support Scale for Children |

HRQoL scores impaired relative to published norms on healthy youth (P<0.001) ~11% met criteria for clinically significant depressive symptoms Strong predictors of HRQoL included: Depressive symptoms, perceived social support from classmates, degree of OW and SES |

Table 6.

| ABAKQ | Adolescent Behaviours, Attitudes, and Knowledge Questionnaire |

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| AQoL-6D | Assessment of Quality of Life-6D scale |

| BAI | Becks Anxiety Inventory Scale (validated tool) |

| BDI | Becks Depression Inventory Scale (validated tool) |

| BED | Binge eating disorder |

| BMI | Body mass index: weight/height |

| BMI-SDS | BMI Standard Deviation Score |

| BP | Bipolar (mental health disorder) |

| CBCL | Child Behavior Checklist (validated tool) |

| CBCL-23 | Child Behavior Checklist 23 items |

| CDCAP | Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Using BMI centiles for age/sex-specific reference |

| CDI | Child Depression Inventory (validated tool) |

| CD | Conduct disorders |

| CDI | Children’s Depressive Symptoms Inventory (validated tool) |

| CES-DC | Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children |

| CGI | Clinical Global Impression (severity of mood and eating disorders) |

| ChEAT | The Children’s Eating Attitudes Test |

| ChEDE-Q | Children’s Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire |

| CNRC | Children’s Nutrition Research Center, US |

| CPRS | Connors Parenting Rating Scale |

| CPTRS | Connors Parent and Teacher Rating Scale |

| DHMS | Daily Hassle Microsystem Scale |

| DI | Diagnostic Interview |

| DISC–IV | Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children |

| DISC–V1 | Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children 6th Edition |

| DSM-III | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 3rd Edition |

| DSM-IV | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 4th Edition |

| DSM-IV-TR | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 4th Edition, text revision |

| DSMMD | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| EAT | Eating Amongst Teens |

| EDE | Eating Disorder Examination |

| EDE-Q | Eating Disorder Examination Self-Report Questionnaire |

| EF | Executive Functioning |

| HOYVS | Health of Young Victorians’ Study |

| HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| ICD-10 | ICD-10 is the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems by WHO |

| IOTF | International Obesity Task force (reference data with cutoff points for weight status) |

| K-SADS-PL | Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-age Children: present and lifetime version (validated tool) |

| KIDSCREEN-27 | Generic HRQoL for youths aged 8–18 years: subscales physical well-being, psychological well-being, autonomy and parents, social support and peers, school environment (validated tool) |

| KIDSCREEN-52 | Self-perception of security and satisfaction, eg, appearance (internal consistency) |

| KINDL | Measure HRQoL for children and adolescents – captures experiences associated with OW/OB children |

| MDD | Major depressive disorder |

| MDQ | Mood Disorder Questionnaire |

| MHI-5 | Mental Health Inventory-5 (validated tool). |

| MI | Malaise Inventory |

| NGRCCA | National Growth Reference for Chinese Children and Adolescents |

| NIH | National Institute of Health |

| OB | Obese |

| ODD | Oppositional Defiant Disorder |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| OW | Overweight |

| PA | Physical activity |

| PedQol | Pediatric Quality of Life inventory (validated tool) |

| POTS | Perceptions of Teasing Scale (validated tool) |

| QoL | Quality of life |

| RPS | Rutter Parent Scale |

| SAPAC | Self-Administered Physical Activity Checklist (validated tool) |

| SAS | Social Anxiety Scale (validated tool) |

| SCID | Structured Clinical Examination for DSM-IV (validated) |

| SDC | Social Development Scale |

| SDQ | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (validated tool) |

| SECCYD | Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development |

| SEI | Self-Esteem Inventory (validated tool) |

| SES | Socio-Economic Status |

| SLAITS | State and Local Area Telephone Survey |

| SMFQ-D | Short Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (high internal consistency) |

| SPSQ | Swedish Parenting Stress Questionnaire (4 domains-SPSQ: life-events/social support, frequency of exposure [validated tool]) |

| STAI/STAIc | State Trait Anxiety Inventory/for Children (validated tool) |

| SWAN | Strengths/Weaknesses of ADHD/Normal Behavior |

| SPSQ | Swedish Parenting Stress Questionnaire (validated tool) |

| TEENS | Teaching, Encouragement, Exercise, Nutrition, Support Program |

| UW | Underweight |

| UWCBs | Unhealthy Weight Control Behaviors |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Depression and anxiety

Previous research findings about the relationship between depression and childhood OW/OBy suggest that weight gain during adolescence may be related to depression, negative mood states, and poor self-esteem.7,10

In relation to depression and anxiety, Table 3 summarizes 16 studies that are currently reviewed. Diagnosis for depression and anxiety was confirmed either through diagnostic or clinical interview in 9 studies5,11–18 or through specifically focused validated questionnaires in 7 studies.19–25 Body mass index (BMI) was obtained through direct measurement, from documentation/clinical records or self-report, and body weight status was determined using national and international reference data and cutoff points criteria.5,11–25 Study designs included prospective longitudinal,13,14,18,20,23 cross-sectional,15,16,19,21,22 population-based,25 cohort,24 clinical cohort,11,12 and retrospective studies.5,17

Numerous studies continue to report an association between depression and childhood OBy.14–16,21,22,26 Anxiety disorders and stress associated with childhood OW/OBy are less well documented.14,16,24 To date, related research studies have reported mixed findings.

Study findings varied in relation to the strength of association between depression and childhood OBy.11,15–17,19,21 OW/OB children, compared with normal weight children, were found to be significantly more likely to experience depression as diagnosed by medical interview,15,16 with evidence that increasing weight in children was associated with increasing levels of psychosocial distress which is significantly correlated with depression, diagnosed by self-reported questionnaire.21 Other studies of childhood OW/OBy did not support these findings and reported the prevalence of depression (medical diagnosis) being only modestly greater than the general population,11 or having a weak association, as assessed by Child Depression Inventory (CDI) questionnaire.19 In OB children, no statistically significant difference was found in the rates of most common psychiatric disorders including medical diagnosed depression.5

Only a small number of studies have reported sex differences in OW/OB children/adolescents in relation to depression/anxiety.14,21,22 OW/OB girls were reported to have a significantly greater increase in depression than OW/OB boys,21 with greater odds of developing depression and anxiety with increasing weight.14 OB girls also demonstrated more social anxiety than OB boys.24 In contrast, OW/OB boys were found to be at higher odds of depressive symptoms than boys of normal weight.22

Other relevant findings of interest relate to the older OB child (12–14 years) having an increased chance of developing depression and other internalizing disorders such as anxiety and paranoia.17 Children also reporting stress on several levels have a significantly higher odds for becoming OB.23

Findings from studies suggest greater psychopathology among OW/OB adolescents than non-OB adolescents.11,25,27 OB children/adolescents are at more risk of diagnosed mood disorder in adulthood,13 with OW/OB children and adolescents seeking psychiatric treatment and being diagnosed with depression5 and diagnosed bipolar disorders.5,11 OW/OB children/adolescents have been commonly reported to cope with an increased psychiatric burden11 and, when psychologically unhealthy, also more likely to report thoughts and attempts of suicide.25

Family situations and influences also need to be considered while considering risk factors for childhood OBy and/or developing psychological disorders.12,23 Maternal mental health disorders predisposed OB children to a higher significant risk of anxiety,12 and increased psychological and psychosocial stress in families may be a contributing factor for childhood OBy.23

ADHD

ADHD is one of the most common childhood psychiatric disorders and is estimated to affect between 5% and 10% of young schoolchildren worldwide.28 In relation to ADHD and childhood OBy, Table 4 summarizes 17 studies that are currently reviewed. Study designs included longitudinal,29–32 cross-sectional,33–37 cohort,38–41 retrospective documentary analysis,5,42,43 and secondary analysis.44

ADHD diagnosis was confirmed through diagnostic/clinical interview in 11 studies5,29,31,33,34,37–39,41–43 and through ADHD-focused checklists and scales in 6 studies.30,32,35,36,40,44 Self-reporting was recognized to be a limitation in 1 study.40 Body weight status was determined using either national5,31,33,35,38,41–44 or international reference data and cutoff points criteria.29,30,32,36,37,39

Numerous studies have reported associations between ADHD and childhood OBy.14,30–32,35,37 The strength of association between ADHD and childhood OBy varies across research studies. When compared to the general population, only 2 studies reported a significant association between OBy and ADHD symptoms with children/adolescents as assessed by clinical diagnosis35,43 and CPRS.33 Other studies have reported an increased incidence of OB children with ADHD,36 increased risk of becoming OB,29,30,32 and increased odds of children with ADHD becoming OW when not using ADHD medication.37

Children with ADHD and children displaying childhood conduct problems such as disobedience, defiance, aggression, cruelty to others, and destruction of property were prospectively associated with OW/OB young adults.30,31 These behaviors in early childhood were also predictive of disproportionate increase in BMI by early adolescence30 or early adulthood.31

In contrast, a lower incidence of OW/OBy was noted in children with ADHD treatment34 while other studies did not find any association between ADHD and OW/OBy.5,40,42,45 Young OB adolescents are also reported to have lower rates of ADHD (self-reported) compared with healthy and underweight (UW) groups,40 and children diagnosed with ADHD were more likely to be normal-weight or UW than OB.5

Other psychological comorbidities

In relation to other psychological morbidities, Table 5 summarizes 30 studies currently that are reviewed. Study designs included prospective longitudinal,20,31,32,46–48 cross-sectional,15,16,21,49–54 cohort,24,55–63 and retrospective cohort/documentary analysis.5,17,64–66

Diagnosis of related psychological comorbidities was confirmed either through diagnostic or clinical interview in 6 studies5,15–17,53,64 or through specifically focused questionnaires in 24 studies.20,21,24,31,32,46–52,54–63,65,66 All the studies obtained BMI data and determined weight status using national and international reference data and cutoff points criteria.

Self-esteem

Study findings confirmed that OW/OB children had significantly lower self-esteem than normal-weight peers, as measured by various focused questionnaires.21,49,54 Findings confirmed that a clear negative impact on self-esteem was associated with OW/OB children49,54 who were more likely to have an increased child body dissatisfaction21,54 and lower perceived self-worth and self-competence than normal-weight peers.49

Findings are mixed in relation to gender issues.20,49 OB girls completing a self-perception profile, compared with OB boys, had significantly more negative perceptions of their physical appearance, self-worth, and how they felt they were accepted by social groups, including their peers.49 In contrast, no sex differences were found between psychological factors and weight problems with both sexes reporting the association with low self-esteem and OBy.20 Self-esteem of OB children also appears to decrease with age with older children reporting significant reduction in self-esteem related to physical appearance than younger children.21,67 It is interesting to note that parenting is not associated with child body dissatisfaction but parental responsiveness to OW/OBy is positively associated with child self-esteem.54

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

In research studies, childhood OBy is consistently associated with a poorer HRQoL when compared with lower-weight children.24,47,48,51,55,62,63,66 The findings for HRQoL tended to be consistent across the studies for both boys and girls. However, sex differences were noted in a study with OB treatment seeking patients with females reporting poorer HRQoL,62 and females also reported lower HRQoL compared with males and healthy-weight females.55 Severely OB children also reported depressive symptomology in the clinical range as assessed by Becks Depression Inventory Scale and marked impairments in both generic QoL66 and HRQoL.24,63,66 The association between increasing BMI and lower HRQoL being reported became stronger in later childhood.51

Conduct and stigmatization

OW/OB children were more likely to experience multiple and clinically significant associated psychosocial problems than their healthy-weight peers5,21 with increasing conduct issues/disorders (such as disobedience, disruptive aggressive and destructive behavior, physical and verbal abuse).5,17,31,52 Other issues include peer problems,51,52,60 inattention issues32 along with emotional symptoms.51,60 The association between symptoms and OW/OBy was found to be stronger with increasing age in childhood,51 with increasing weight at younger ages (4–5 years) and associated with peer relationship problems at age 8–9 years.61

Bullying and teasing, manifestations of OB stigma, were stressors associated with negative psychological outcomes and occurred more frequently in OW children.68 Studies reported that persistent intense teasing and bullying experienced from childhood influences psychological complications.15,16,58,59,69 OW/OB adolescents most distressed by weight-related teasing exhibited lower self-esteem56,59 and higher depressive disorders.56,58,59 Primary sources of stigma for children and adolescents were reported to include peers, teachers/educators, parents, and health care providers.58,69–71 OW/OB children being bullied and teased may also have less favorable conduct and poorer school performance, social circumstances, and social involvement when compared with normal-weight children.70 Research findings reported that OW/OB children between 6 and 13 years were 4–8 times more likely to be teased and bullied than normal-weight peers.21 OBy- and weight-related teasing is a significant risk factor for the development of psychosocial problems, including weight-based teasing, social stigmatization/peer rejection,50 and later eating disorders and unhealthy weight-control behaviors.58

Eating disorders

There is a clear overlap with OBy and eating disorders in several areas of psychosocial impairment with girls being more vulnerable to comorbid mood and eating problems.72 Research findings revealed that 25% of OB girls used extreme weight-control behaviors such as inducing vomiting, abusing laxatives, diet pills, fasting, or smoking.46 The relationship between OBy and eating behaviors in children/adolescents is evident with OB adolescents clearly at risk of developing a restrictive-eating disorder.64,65 There is a very high prevalence rate of mood disorders and significantly higher lifetime prevalence of bulimia nervosa in weight-loss-seeking patients with childhood OBy onset.64 Studies have reported that OW/OB children and adolescents were more likely to report higher body dissatisfaction,21,54 display extreme dieting behaviour47 and eating disorder symptoms, and clinically significant associated psychosocial problems than healthy-weight peers.21

Prevention and interventions

Available evidence confirms that obesity can be treated effectively in younger children73 and adolescents.74 Multicomponent interventions targeting physical activity and healthy diet could benefit OW/OB children specifically in overall school achievement,73 and family-based intervention with maintenance follow-up can improve psychosocial and physical QoL.74 Systematic attempts to manage and treat OW in the early years and pre-school years are required.47 A key focus on interventions should be on childhood/adolescent mental health, improving knowledge, and implementing high standard of treatment for OW children.75 This needs to involve psychological and social support from families with recommendations about changing lifestyle.23 In children with disruptive behavior disorders, secondary prevention and management strategies should include promoting healthy eating and physical activity to prevent adult OBy.19,44

Screening recommended

Routine screening of children with further comprehensive screening for high-risk populations.

Specific screening for various interrelated symptoms including OW/OBy, symptoms of impulsive eating behaviors, psychiatric disorders, psychological disturbances, and conduct-related issues.

Systematic screening for ADHD in OB adolescents with bulimic behaviors.33

Early identification and intervention

Treating children and female anxiety and depression may be an important effort in the prevention of obesity.14,71

Physicians, parents, and teachers should be informed of specific comorbidities associated with childhood OBy to target interventions that could enhance well-being.50

Interventions should recognize individual differences in terms of identifying motivating goals for accomplishing weight management.61 Follow-up support is essential to maintain any straying from the short-term effects gained.76

Family interventions need to focus on parenting/attachment issues, behavioral factors, or self-management interventions to implement healthy lifestyles.57

Stigma-reduction efforts are needed to improve attitudes toward OBy.

Motivational interviewing in the treatment of obesity provides a more guiding style encouraging individuals to explore and understand their own intrinsic barriers and incentives to change.61,77

Future research

Future research needs well-designed prospective and hypothesis-driven longitudinal studies to further investigate specific areas (with different populations) and psychiatric and psychological outcomes. Appropriate control groups of clinical or nonclinical populations need to be included. Examples of future research in childhood obesity include further investigation of:

ADHD: 1) causality in the relationship between ADHD and OBy, and psychopathological pathways linking the two conditions; 2) experimental designs to establish cause and effect for BMI and HRQoL;51 3) cause and effect of causal link between bulimic behaviors and ADHD and potential common neurobiological alterations;33 4) OBy risks of young adults who manifest conduct problems in early life.31

Body image: directional nature of relationships between body image and OBy as well as changes in psychosocial functioning.24

Family functioning: influencing role and extent of parental, family functioning, peer, educator, or societal-related factors in psychological consequences.12

Depression: 1) directional nature of sedentary behavior and onset of depression;19,78 2) moderating versus mediating roles of variables such as trait negative effect, depressive and anxiety symptoms, and low self-esteem and their influence on eating pathology.56

Psychosocial: 1) role of psychosocial factors and treatment interventions that target extremely OB individuals based on their BMI, and socio-demographic profiles; 2) eating patterns and the dynamic relationship between binge eating and BMI.

Lifestyle: 1) causal relationships between physical activity behavior, motivation to change, BMI change and development of comorbid health conditions;24 2) optimal strategies for encouraging lifestyle change and accomplishing weight management.61,77

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to focus on research findings related to psychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial consequences of childhood OBy from an international perspective. The precise extent of these complications remains uncertain due to the range of methodological approaches and methods used across studies. Causal mechanisms are not yet fully understood or convincing, but they are likely to involve a complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors.

Compared to healthy-weight children and adolescents, there seems to be a consistent heightened risk of psychological comorbidities including depression, compromised perceived QoL, depression and anxiety, self-esteem, and behavioral disorders. In turn, these disorders associated with OBy have a consistent adverse impact on their perceived HRQoL and psychiatric, psychological, and psychosocial disorders. These can be enduring in nature and may continue into adult life with the potential for lifelong health problems.

In general, consistent findings have established that childhood OW/OBy was negatively associated with psychological comorbidities, such as depression, poorer perceived HRQoL, emotional and behavioral disorders, and self-esteem during childhood. Findings are similar to other reviews in this period3,28,45,72,79–82 in that OW/OB children and adolescents were more likely to experience psychological problems than healthy-weight peers. Findings suggest a shared link between depression and obesity such that OBy increases the risk of depression in adult life, but also that depression predicts the development of obesity.26

Evidence related to the psychiatric disorder, ADHD, remains unconvincing because of various findings from studies. Many studies did report an association between ADHD and elevated weight status.14,30–32,35,37 Children presenting with early and persistent ADHD in early and mid-childhood are also at an increased risk of OBy in adult life.28 Therefore, the child with ADHD may be at risk of becoming OW or the OW child may be at risk for a diagnosis of ADHD. Some studies did not report any association between ADHD and OW/OBy.5,40,42,45 Other reviews also reported that the data were insufficient and inconsistent.3,4

This review found that OW children were more likely to experience multiple associated psychosocial problems than their healthy-weight peers. The strength of association between psychological disorders, psychosocial problems, and OW may also depend upon OBy stigma, teasing, and treatment-seeking children.66,71,82,83 This stigmatization is now a common event within society and may be evidenced in the form of negative stereotypes, victimization, and social marginalization.83 OBy stigma and teasing/bullying are pervasive and can have serious consequences for emotional and physical health. Stigma may be linked to obesity being the target of many public health campaigns that influence young OW/OB children and adolescents to control their weight, often through drastic measures.46,83 This means that psychiatric symptoms or disorders may be a consequence of being OB in a culture that stigmatizes OBy. Alternatively psychiatric disorders may contribute to the development of obesity in vulnerable individuals.84

Intervention and action are necessary to prevent childhood and adolescent OBy.1 Children are particularly vulnerable as both obesity and psychiatric conditions often have their origins during this crucial developmental period.79 If obesity remains in adolescence, then it is likely to persist into adult life.14,85

Conclusion

The aim of this review was to establish what has recently changed in relation to common psychological consequences associated with childhood OBy. Despite extensive research being undertaken over the previous decade, it remains unclear as to whether psychiatric disorders and psychological problems are a cause or a consequence of childhood obesity. The prevalence of both childhood OW/OBy and associated psychiatric and psychological disorders is increasing, and there is an acute heightened awareness of this serious public health issue in the society and health-related policy. However, it is also still not proven whether common factors promote both obesity and psychiatric disturbances in susceptible children and adolescents. This finding in itself reflects the challenge of researching and understanding the complex factors associated with childhood OBy and psychological well-being. This review has illustrated that OW/OB children are more likely to experience the burden of psychiatric and psychological disorders in childhood, adolescence, and possibly into adulthood. A cohesive and strategic approach to tackle the OBy epidemic is necessary to combat this increasing trend which is compromising the health and well-being of the young generation and seriously impinging on resources and economic costs. As a matter of urgency, further focused research is essential to identify the diverse range of mechanisms driving the current increasing trajectory. Reliable and convincing evidence is needed to inform policy, economic regulation interventions, and strategies to prevent OBy from affecting future generations.

Footnotes

Disclosure

LM’s time on this research was funded by UK Medical Research Council core funding as part of the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit “Social Relationships and Health Improvement” program (MC_UU_12017/11) and “Complexity in Health Improvement” program (MC_ UU_12017/14). The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation . Obesity and overweight factsheet no. 311. Geneva: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9945):766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulgaron ER. Childhood obesity: a review of increased risk for physical and psychological comorbidities. Clin Ther. 2013;35(1):A18–A32. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders RH, Han A, Baker JS, Cobley S. Childhood obesity and its physical and psychological co-morbidities: a systematic review of Australian children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174:715–746. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2551-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marks S, Shaikh U, Hilty DM, Cole S. Weight status of children and adolescents in a telepsychiatry clinic. Telemed J E Health. 2009;15(10):970–974. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilfley DE, Vannucci A, White EK. Early intervention of eating- and weight-related problems. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17(4):285–300. doi: 10.1007/s10880-010-9209-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman E, Whitaker RC. A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2002;110:497–504. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescent. JAMA. 2003;289(14):1813–1819. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams J, Wake M, Hesketh K, Maher E, Walters E. Health-related quality of life of overweight and obese children. JAMA. 2005;293(1):70–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pine DS, Goldstein RB, Wolk S, Weissman MM. The associations between childhood depression and adulthood body mass index. Pediatrics. 2003;107:1049–1056. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.5.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein BI, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, et al. Preliminary findings regarding overweight and obesity in pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(12):1953–1959. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth B, Munsch S, Meyer A, Isler E, Schneider S. The association between mothers’ psychopathology, childrens’ competences and psychological well-being in obese children. Eat Weight Disord. 2008;13(3):129–136. doi: 10.1007/BF03327613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanderson K, Patton GC, MrKercher C, Dwyre T, Vem AJ. Overweight and obesity in childhood and risk of mental disorders: a 20-year cohort study. Aust N Z J Psych. 2011;45:384–392. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.570309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, Must A. Association of depression and anxiety disorders with weight change in a prospective community-based study of children followed up into adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(3):285–291. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bell LM, Byrne S, Thompson A, et al. Increasing BMI z-scores is continuously associated with complications of overweight children, even in healthy weight ranges. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:517–522. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell LM, Curran JA, Byrne S, et al. High incidence of obesity comorbidities in young children: a cross sectional study. J Pediatr Child health. 2011;47:911–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eschenbeck H, Kohlmann CW, Dudey S, Schurholz T. Physician-diagnosed obesity in German 6- to 14-year-olds. Prevalence and comorbidity of internalizing disorders, externalizing disorders, and sleep disorders. Obesity Facts. 2009;2(2):67–73. doi: 10.1159/000209987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, Jacques PF, Must A. Adolescent obesity and risk for subsequent major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder: prospective evidence. Psychosom Med. 2007;69(8):740–747. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815580b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anton SD, Newton RL, Jr, Sothern M, Martin CK, Stewart TM, Williamson DA. Association of depression with body mass index, sedentary behavior, and maladaptive eating attitudes and behaviors in 11 to 13-year old children. Eat Weight Disord. 2006;11(3):e102–e108. doi: 10.1007/BF03327566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjornelv S, Nordahl HM, Homen TL. Psychological factors and weight problems in adolescents. The role of eating problems, emotional problems and personality traits: the Young-HUNT study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatri Epidemiol. 2011;46(5):353–362. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0197-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson LY, Byrn SM, Blair E, Davies EA, Jakobi P, Zubrick SR. Clusters of psychological symptoms in overweight children. Aust N Z J Psych. 2008;42:118–125. doi: 10.1080/00048670701787560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoare E, Millar L, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, et al. Associations between obesogenic risk and depressive symptomatology in Australian adolescents: a cross sectional study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:767–772. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koch F, Sepa A, Ludvigsson J. Psychological stress and obesity. J Pediatr. 2008;153:839–844. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips BA, Gaudette S, McCracken A, et al. Psychosocial functioning in children and adolescents with extreme obesity. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19(3):277–284. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Wijnen LG, Bolujit PR, Hoeven-Mulder HB, Bernelmans WJ, Wndel-Vos GC. Weight status, psychological health, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts in Dutch adolescents: results from the 2003 E-MOVO project. Obesity. 2010;18:1059–1061. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychaitr. 2010;67:220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swanson SA, Crow S, Le Grange D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714–723. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cortese S, Angriman M, Maffeis C, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obesity: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2008;48(6):524–537. doi: 10.1080/10408390701540124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, Must A. Relationship of childhood behavior disorders to weight gain from childhood into adulthood. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6:297–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson SE, He X, Schoppe-Sullivan S, Must A. Externalizing behavior in early childhood and body mass index from age 2 to 12 years: longitudinal analyses of a prospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duarte CS, Sourander A, Nikolakaros G, et al. Child mental health problems and obesity in early adulthood. J Pediatr. 2010;156(1):93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khalife N, Kantomaa M, Glover V, et al. Childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms are risk factors for obesity and physical inactivity in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(4):425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cortese S, Isnard P, Frelut ML, et al. Association between symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and bulimic behaviors in a clinical sample of severely obese adolescents. Int J Obes. 2007;31(2):340–346. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubnov-Raz G, Perry A, Berger I. Body mass index of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Neurol. 2011;26(3):302–308. doi: 10.1177/0883073810380051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Erhart M, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Wille N, Sawitzky-Rose B, Hölling H, Ravens-Sieberer U. Examining the relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and overweight in children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21(1):39–49. doi: 10.1007/s00787-011-0230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J, Mutyala B, Agiovlasitis S, Fernhall B. Health behaviors and obesity among US children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by gender and medication use. Prev Med. 2011;52(3–4):218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waring ME, Lapane KL. Overweight in children and adolescents in relation to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from a national sample. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e1–e6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrd HCM, Curtin C, Anderson SE. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obesity in US males and females, age 8–15yrs: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2004. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8:445–453. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00124.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Graziano PA, Bagner DM, Waxmonsky JG, Reid A, McNamara JP, Geffken GR. Co-occurring weight problems among children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the role of executive functioning. Int J Obes. 2012;36(4):567–572. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rojo L, Ruiz E, Dominquez JA, Calaf M, Livianos L. Comorbdiity between obesity and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: population study with 13–15 year olds. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;3:519–522. doi: 10.1002/eat.20284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang R, Mao S, Zhang S, Li R, Zhao Z. Prevalence of obesity and overweight among Chinese children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a survey in Zhejiang province, China. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(133):13–133. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pauli-Pott U, Neidhard J, Heinzel-Gutenbrunner M, Becker K. On the link between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obesity: do comorbid oppositional defiant and conduct disorder matter? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(7):531–537. doi: 10.1007/s00787-013-0489-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Racicka E, Hanc T, Giertuga K, Brynska A, Wolanczyk T. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents with ADHD: the significance of comorbidities and pharmacotherapy. J Atten Disord. 2015 Apr 20; doi: 10.1177/1087054715578272. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White B, Nicholls D, Christie D, Cole TJ, Viner RM. Childhood psychological function and obesity risk across the lifecourse: findings from the 1970 British Cohort Study. Int J Obes. 2012;36(4):511–516. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nigg JT, Johnstone JM, Musser ED, Galloway Long H, Willoughby MT, Shannon J. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and being overweight/obesity: new data and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Haines J, Story M, Sherwood NE, van der Berg P. Shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating in adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wake M, Canterford L, Patton GC, et al. Comorbidities of overweight/obesity experienced in adolescence: longitudinal study. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(3):162–168. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.147439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wake M, Clifford SA, Patton GC, et al. Morbidity patterns among the underweight, overweight and obese between 2–18yrs: population-based cross-sectional analysis. Int J Obes. 2013;37:86–93. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franklin J, Denyer G, Steinbeck KS, Caterson ID, Hill AJ. Obesity and risk of low self-esteem: a statewide survey of Australian children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2481–2487. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halfon N, Larson K, Slusser W. Associations between obesity and comorbid mental health, developmental, and physical health conditions in a nationally representative sample of US children aged 10 to 17. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(1):6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jansen PW, Mensah FK, Clifford S. Bidirectional associations between overweight and health-related quality of life from 4–11 years: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37(10):1307–1313. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sawyer MG, Miller-Lewis L, Guy S, Wake M, Canterford L, Karlin JB. Is there a relationship between overweight and obesity and mental health problems in 4–5yr old Australian children. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taner Y, Torel-Ergur A, Bahcivan G, Gurdag M. Psychopathology and its effect on treatment compliance in pediatric obesity patients. Turkish J Pediatr. 2009;51(5):466–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor A, Wilson C, Slater A, Mohr P. Self-esteem and body dissatisfaction in young children and associations with weight and parenting style. Clin Psychol. 2012;16:25–35. [Google Scholar]