Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the major microorganism colonizing the respiratory epithelium in cystic fibrosis (CF) sufferers. The widespread use of available antibiotics has drastically reduced their efficacy, and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are a promising alternative. Among them, the frog skin-derived AMPs, i.e., Esc(1-21) and its diastereomer, Esc(1-21)-1c, have recently shown potent activity against free-living and sessile forms of P. aeruginosa. Importantly, this pathogen also escapes antibiotics treatment by invading airway epithelial cells. Here, we demonstrate that both AMPs kill Pseudomonas once internalized into bronchial cells which express either the functional or the ΔF508 mutant of the CF transmembrane conductance regulator. A higher efficacy is displayed by Esc(1-21)-1c (90% killing at 15 μM in 1 h). We also show the peptides' ability to stimulate migration of these cells and restore the induction of cell migration that is inhibited by Pseudomonas lipopolysaccharide when used at concentrations mimicking lung infection. This property of AMPs was not investigated before. Our findings suggest new therapeutics that not only eliminate bacteria but also can promote reepithelialization of the injured infected tissue. Confocal microscopy indicated that both peptides are intracellularly localized with a different distribution. Biochemical analyses highlighted that Esc(1-21)-1c is significantly more resistant than the all-l peptide to bacterial and human elastase, which is abundant in CF lungs. Besides proposing a plausible mechanism underlying the properties of the two AMPs, we discuss the data with regard to differences between them and suggest Esc(1-21)-1c as a candidate for the development of a new multifunctional drug against Pseudomonas respiratory infections.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic Gram-negative bacterium characterized by an intrinsic high resistance to commonly used antimicrobials (1, 2) and by its ability to form sessile communities, named biofilms (3–5). In this scenario, P. aeruginosa infections can easily take over and affect multiple organ systems, such as the respiratory tract, particularly in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients (6–8). The most common mutation associated with the CF phenotype is phenylalanine deletion at position 508 (ΔF508) in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene (9), encoding an ABC transporter that functions as a chloride channel in the membrane of epithelial cells (10). As a result of this mutation, the secretion of chloride ions outside the cell is inhibited, resulting in the generation of a dehydrated and sticky mucus layer coating the airway epithelia (11, 12). This helps the accumulation of trapped microbes, including P. aeruginosa, with deterioration of lung tissue and impairment of respiratory functions (13–15).

Importantly, P. aeruginosa colonization of host tissues is triggered by an initial attachment of the bacterium to epithelial cells (7, 16) via a variety of surface appendages (e.g., flagella and pili) (17–19). This is then followed by cell internalization, presumably mediated by binding of the bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS; i.e., the major component of the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria) to the CFTR (20–24). Other mechanisms include, e.g., interaction with asialoganglioside 1 (25). Invasion of host cells is a common process used by different microbial pathogens to facilitate escape from immune factors and/or to assist systemic diffusion and infection (26, 27). Intracellular persistence of bacteria that spread into the respiratory tract of CF patients may be one of the reasons responsible for the chronic nature of P. aeruginosa lung infections (17). It protects the bacteria from the host defense mechanisms and from the killing action of conventional antibiotics that hardly enter epithelial cells (28). Hence, the discovery of new antibiotics with new modes of action is highly demanding, and naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) represent potential alternatives (29, 30). AMPs are produced by all living organisms as the first barrier against invading microorganisms (31), and the majority of them are characterized by having a net positive charge at neutral pH and the tendency to form an amphipathic structure in a hydrophobic environment (32, 33).

Recently, we studied a derivative of the frog skin AMP esculentin-1a, esculentin-1a(1-21)NH2 [Esc(1-21) GIFSKLAGKKIKNLLISGLKG-NH2] (34, 35), corresponding to the first 20 residues of esculentin-1a, as well as its diastereomer, Esc(1-21)-1c, containing two d-amino acids at positions 14 and 17 (i.e., d-Leu and d-Ser, respectively). The data revealed that the two peptides have strong bactericidal activity against both the planktonic and biofilm forms of P. aeruginosa, with the diastereomer being more active than the wild-type peptide on the sessile form of this pathogen (36). Furthermore, the diastereomer is more stable in human serum (36). However, there are no studies on the effect of these peptides on infected lung epithelial cells, and only limited information is available for other AMPs.

Importantly, the ability of a peptide to restore the integrity of damaged infected tissue, for example, by accelerating migration of epithelial cells in addition to potent antimicrobial activity, would make it a more promising candidate for the development of a new anti-infective agent. Another advantage is the ability to resist degradation by proteases. Here, we report on the effect of the two esculentin-derived AMPs on the viability of bronchial epithelial cells expressing a functional CFTR or a mutant form of CFTR (ΔF508-CFTR). Furthermore, we investigated the peptides' ability (i) to kill a clinical isolate of P. aeruginosa, once internalized in the two bronchial cell lines, and (ii) to stimulate migration of bronchial cells in the presence of concentrations of LPS that better simulate an infection condition by means of a pseudo-wound-healing assay. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of cell migration induced by AMPs in the presence of LPS. In addition, we studied the peptides' distribution within bronchial cells and their stability to elastase from P. aeruginosa and human neutrophils. The data are discussed with regard to the different biochemical properties of the two peptides, and a plausible mechanism for their antimicrobial and wound-healing properties is proposed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Minimal essential medium (MEM), heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), and penicillin-streptomycin were from Euroclone (Milan, Italy); puromycin, gentamicin, 3(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), Triton X-100, AG1478, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), rhodamine, Mowiol 4-88, LPS from P. aeruginosa serotype 10 (purified by phenol extraction), and elastase from human leukocytes were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Luis, MO). Elastase from P. aeruginosa was from Millipore Merck (Merck, Milan, Italy). All other chemicals were reagent grade.

Peptides synthesis.

Synthetic Esc(1-21) and its diastereomer, Esc(1-21)-1c, as well as rhodamine-labeled peptides [rho-Esc(1-21) and rho-Esc(1-21)-1c], were purchased from Chematek Spa (Milan, Italy). Briefly, each peptide was assembled by stepwise solid-phase synthesis using a standard F-moc strategy and purified via reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) to a purity of 98%, while the molecular mass was verified by mass spectrometry.

Cells and bacteria.

The following cell cultures were employed: immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells derived from a CF patient (CFBE41o-) transduced with a lentiviral system to stably express ΔF508-CFTR (ΔF508-CFBE) or functional CFTR (wt-CFBE) (37). Cells were cultured in MEM supplemented with 2 mM glutamine (MEMg) plus 10% FBS, antibiotics (0.1 mg/ml of penicillin and streptomycin), and puromycin (0.5 μg/ml or 2 μg/ml for wt-CFBE or ΔF508-CFBE, respectively) at 37°C and 5% CO2 in 75-cm2 flasks. The bacterial strain used was an invasive clinical isolate from the early stage of chronic lung infection, P. aeruginosa KK1, from the collection of the CF clinic Medizinische Hochschule of Hannover, Germany (38, 39).

Peptides' effect on the viability of airway epithelial cells.

The effect of both peptides on the viability of wt-CFBE or ΔF508-CFBE cells was evaluated by the MTT colorimetric method (40). MTT is a tetrazolium salt which is reduced to a colored formazan product by mitochondrial reductases in metabolically active cells. Briefly, about 4 × 104 cells suspended in MEMg supplemented with 2% FBS were seeded in wells of a 96-well microtiter plate. After overnight incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, the medium was removed and 100 μl of fresh serum-free MEMg or Hanks' buffer (136 mM NaCl, 4.2 mM Na2HPO4, 4.4 mM KH2PO4, 5.4 mM KCl, 4.1 mM NaHCO3, pH 7.2, supplemented with 20 mM d-glucose), with or without the peptide at different concentrations, was added to each well. After 2 h or 24 h, as indicated, at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, the medium was replaced with 100 μl of Hanks' buffer containing 0.5 mg/ml MTT. The plate was incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 4 h, and the formazan crystals were dissolved by adding 100 μl of acidified isopropanol according to reference 41. Absorption of each well was measured using a microplate reader (Infinite M200; Tecan, Salzburg, Austria) at 570 nm. The percentage of metabolically active cells compared to control samples (cells not treated with peptide) was calculated according to the formula (absorbancesample − absorbanceblank)/(absorbancecontrol − absorbanceblank) × 100, where the blank is given by samples without cells and not treated with the peptide.

Cell infection and peptide's effect on intracellular bacteria.

About 100,000 bronchial cells in MEMg supplemented with 10% FBS were seeded in 24-well plates and grown for 2 days at 37°C and 5% CO2. The clinical isolate KK1 was grown in Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C with mild shaking (125 rpm) to mid-log phase (optical density of 0.8 at 590 nm) and subsequently harvested by centrifugation. The pellet was then resuspended in MEMg and properly syringed using a 21-gauge needle to avoid clump formation before infecting cells. A multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100:1 (bacteria to cells) was used. Two hundred microliters of this bacterial suspension, containing about 1 × 107 CFU, was coincubated for 1 h with wt-CFBE/ΔF508-CFBE at 37°C and 5% CO2. After infection, the medium was removed and the cells were washed three times with MEMg and then incubated for 1 h with a gentamicin solution (200 μg/ml in MEMg) to remove extracellular bacteria. Afterwards, the medium was aspirated and the infected cells were washed three times as described above. Two hundred microliters of Hanks' solution with or without the peptide at different concentrations was added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. After peptide treatment, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with 300 μl of 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at 37°C and 5% CO2. Each sample was then sonicated in a water bath for 5 min to break up possible bacterial clumps, and appropriate aliquots were plated on agar plates for counting of CFU after 24 h at 37°C.

In vitro cell migration assay.

The ability of single peptides or P. aeruginosa LPS to stimulate migration of CF cells was evaluated by a modified scratch assay, as reported previously (36). Briefly, special cell culture inserts for live cell analysis (Ibidi, Munich, Germany) were placed into wells of a 12-well plate. About 35,000 cells suspended in MEMg supplemented with 10% FBS were seeded in each compartment of the culture insert and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for approximately 24 h to allow cells to grow to confluence. Afterwards, inserts were removed to create a cell-free area (pseudo-wound) of approximately 500 μm; 1 ml MEMg with or without the peptide or LPS at different concentrations was added to each well. Plates were incubated as described above to allow cells to migrate, and samples were visualized at different time intervals under an inverted microscope (Olympus CKX41) at ×4 magnification and photographed with a Color View II digital camera. The percentage of cell-covered area at each time was determined by the WIMASIS Image Analysis program.

In another set of experiments, cell migration was evaluated in the presence of both LPS and Esc(1-21) or Esc(1-21)-1c at the indicated concentration. Furthermore, the implication of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) in peptide-induced cell migration was analyzed by pretreating cells for 30 min with 5 μM tyrosine phosphorylation inhibitor tyrphostin (AG1478) (42).

Fluorescence studies.

About 2 × 105 bronchial cells in MEMg supplemented with 10% FBS were seeded on 0.13- to 0.17-mm-thick coverslips (properly put into 35-mm dish plates) and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, samples were washed with 1 ml PBS and treated with 4 μM rhodamine-labeled peptide or rhodamine (for control samples) in MEMg. After 30 min and 24 h of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, cells were washed four times with PBS and fixed with 700 μl of 4% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Afterwards, they were washed twice with PBS and stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml) for 5 min at room temperature to visualize the nuclei. After three additional washes, the coverslips were mounted on clean glass slides using Mowiol mounting medium and observed under an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope with a 60× objective lens (oil). Data analysis was done using Olympus Fluoview (version 4.1) and Image J. Results are reported as the ratio between the fluorescence intensity of rhodamine-labeled peptides in the cytoplasm versus that in the nucleus.

Peptides' stability to proteases.

Peptides were dissolved in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml; afterwards, 130 μl was incubated with 4 μg of human or bacterial elastase (final enzyme concentration equal to 1 μM). At the indicated time intervals, 30-μl aliquots were withdrawn, diluted with 770 μl of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)–water, and analyzed by RP-HPLC and mass spectrometry. Liquid chromatography was performed on a Phenomenex Jupiter C18 analytical column (300 Å, 5 μm, 250 by 4.6 mm) in a 30-min gradient, using 0.1% TFA in water as solvent A and methanol as solvent B. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed with a Bruker Daltonic ultraflex matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization tandem time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF/TOF) mass spectrometer on withdrawn samples as well as on HPLC-eluted peaks.

Statistical analyses.

Quantitative data, collected from independent experiments, were expressed as the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with PRISM software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Differences were considered to be statistically significant for a P value of <0.05. The levels of statistical significance are indicated in the legends to the figures.

RESULTS

Peptides' effect on the viability of lung epithelial cells.

In a previous study (36), it was reported that both Esc(1-21) and its diastereomer, Esc(1-21)-1c, are not toxic to A549 epithelial cells up to 64 μM, and that the diastereomer is substantially less toxic when used at higher concentrations (36). Although A549 cells possess morphological and biochemical properties of alveolar epithelial cells (type II pneumocytes) (17), they do not express CFTR (43, 44). Therefore, we studied the effect of both esculentin peptides on the viability of airway epithelial cells stably expressing the most common CFTR mutation (ΔF508) and the corresponding wild-type cell line expressing a functional CFTR.

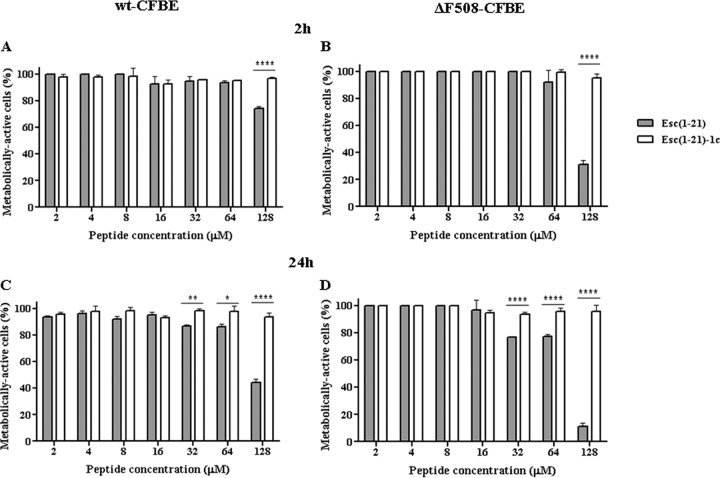

As indicated by the results of the viability assay performed in the cell culture medium, MEMg (Fig. 1), the two peptides were not toxic to either type of epithelial cells at a concentration range between 2 μM and 64 μM within 2 h. However, the wild-type peptide turned out to be toxic at 128 μM, causing approximately 25% and 70% reduction in the percentage of metabolically active wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE cells, respectively (Fig. 1A and B). Furthermore, after a long-term treatment (24 h), the cytotoxicity of Esc(1-21) became more pronounced, inducing about 20 to 25% reduction of metabolically active epithelial cells at 32 μM and 64 μM (Fig. 1C and D). A higher cytotoxicity was recorded at 128 μM, with ∼60% and 90% killing of wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE cells, respectively. Importantly, the diastereomer did not induce any reduction in the percentage of metabolically active cells (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Peptides' effect on the viability of bronchial epithelial cells. About 4 × 104 wt-CFBE (A and C) or ΔF508-CFBE (B and D) cells were plated in wells of a microtiter plate. After overnight incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, the medium was replaced with 100 μl fresh MEMg supplemented with the peptides at different concentrations. After 2 h or 24 h, cell viability was determined by MTT reduction to insoluble formazan. Cell viability is expressed as a percentage with respect to the control (cells not treated with the peptide). All data are the means from four independent experiments ± SEM. The levels of statistical significance between the two peptides are P values of <0.05 (*), <0.01 (**), and P <0.0001 (****).

Peptides' activity on bronchial cells infected by the CF clinical isolate KK1.

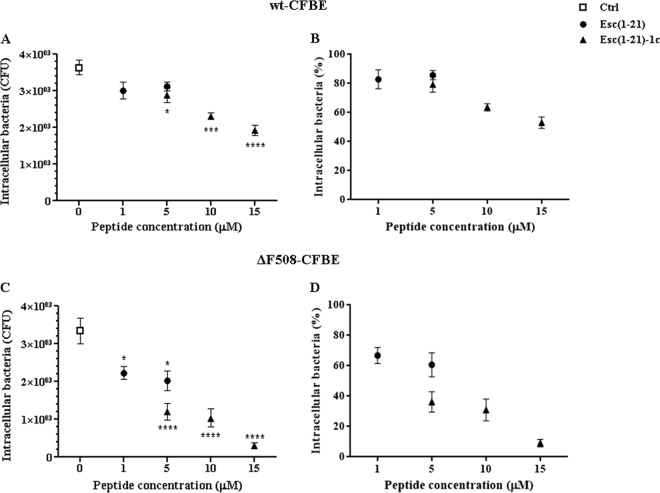

We monitored the effect of the two peptides on wt-CFBE (Fig. 2A and B) and ΔF508-CFBE cells (Fig. 2C and D) after infection with a clinical isolate of P. aeruginosa (KK1 strain). This strain was already shown to invade bronchial cells in vitro (38). According to the published literature (25), P. aeruginosa tends to target particular CF epithelial cells rather than making a concerted attack on the whole population of cells. Figure 2 shows the number of intracellular bacteria that were calculated either as CFU per sample (Fig. 2A and C) or as percentage (Fig. 2B and D) with respect to the peptide-untreated infected cells (control). Note that the number of internalized bacteria (∼3,500 CFU) in our control bronchial cells (Fig. 2A and C) was well correlated with the previously found uptake of different P. aeruginosa strains by CF airway epithelial cells (21).

FIG 2.

Effect of Esc(1-21) and its diastereomer, Esc(1-21)-1c, on the intracellular killing of P. aeruginosa KK1 in wt-CFBE (A and B) and ΔF508-CFBE (C and D) cells. About 1 × 105 cells were seeded in 24-well plates and grown to confluence. Afterwards, they were infected with the bacterium for 1 h; nonadherent extracellular bacteria were removed upon antibiotic treatment, and infected cells were left untreated or were treated for 1 h with the peptide at different concentrations, as indicated. Control samples (Ctrl) are peptide-untreated infected cells. The number of intracellular bacteria is expressed either as CFU per sample (A and C) or as a percentage with respect to the control (B and D). All data are the means from four independent experiments ± SEM. The levels of statistical significance between peptide-treated infected cells and control samples are P values of <0.05 (*), <0.001 (***), and <0.0001 (****).

The data shown in Fig. 2B reveal that the two peptides, at 5 μM, caused about 15 to 20% killing of intracellular bacteria 1 h after treatment. This is when they were used on wt-CFBE cells in Hanks' buffer. This condition was used to better simulate a physiological environment without the presence of cell culture medium components. However, the killing effect was more evident in ΔF508-CFBE cells (Fig. 2D), where 5 μM Esc(1-21) and its diastereomer caused an ∼40% and 60% decrease in the number of intracellular bacteria, respectively, compared to untreated infected cells. Due to the negligible cytotoxicity of the diastereomer Esc(1-21)-1c compared to the all-l isomer in Hanks' buffer (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), it was possible to use Esc(1-21)-1c at higher concentrations without damaging host epithelial cells. Interestingly, 10 μM and 15 μM Esc(1-21)-1c gave rise to about 70% and 90% reduction in the survival of intracellular bacteria in ΔF508-CFBE (Fig. 2D), whereas only ∼50% bacterial killing in wt-CFBE cells was obtained after exposure to 15 μM Esc(1-21)-1c (Fig. 2B). Note that the toxicity of Esc(1-21) to bronchial cells when tested in Hanks' buffer, compared to that in MEMg (Fig. 1), could be due to the absence of medium components that may affect its activity, resulting in lower cytotoxicity (Fig. 1).

Wound-healing assay in the presence of peptides, LPS, or their combination.

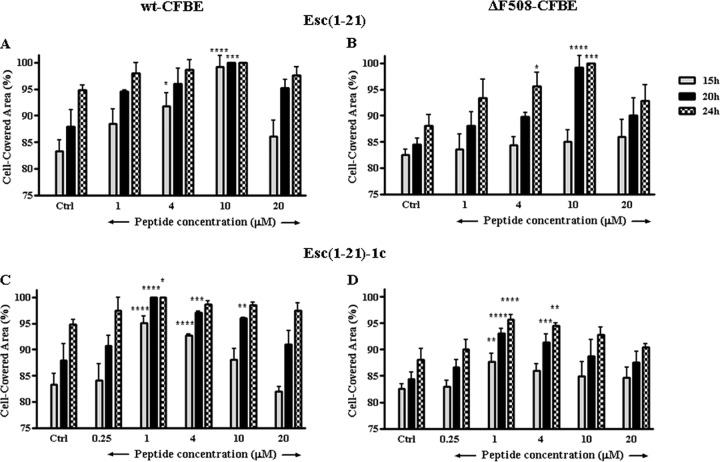

Since airway epithelium and CFTR have been shown to play a crucial role in maintaining lung function and wound repair (45), we investigated the effect of the two peptides on the migratory activity of the bronchial cells in the cell culture medium MEMg. Both AMPs were able to stimulate migration of wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE cells, as indicated by their ability to induce ∼100% coverage of the pseudo-wound field produced in the cell monolayer (by means of special cell culture inserts) within 20 h at optimal concentrations of 10 μM for Esc(1-21) (Fig. 3A and B) and 1 μM for its diastereomer (Fig. 3C and D). A slower cell migration speed was observed for the mutant ΔF508-CFBE, in agreement with a previous study (45) that showed how the defective function of CFTR caused a reduced lamellipodium area from the leading edge of airway epithelial cells (46).

FIG 3.

Effect of Esc(1-21) and Esc(1-21)-1c on the closure of a pseudo-wound field produced in a monolayer of wt-CFBE (A and C) and ΔF508-CFBE (B and D). Cells were seeded in each side of an Ibidi culture insert and grown to confluence; afterwards, they were left untreated or were treated with the peptide. Cells were photographed at the time of insert removal and examined for cell migration after 15, 20, and 24 h from peptide addition. The percentage of cell-covered area at each time point is reported on the y axis. Peptide-untreated cells were used as a control (Ctrl). The data are the means from four independent experiments ± SEM. The levels of statistical significance between Ctrl and treated samples are P values of <0.05 (*), <0.01 (**), <0.001 (***), and <0.0001 (****).

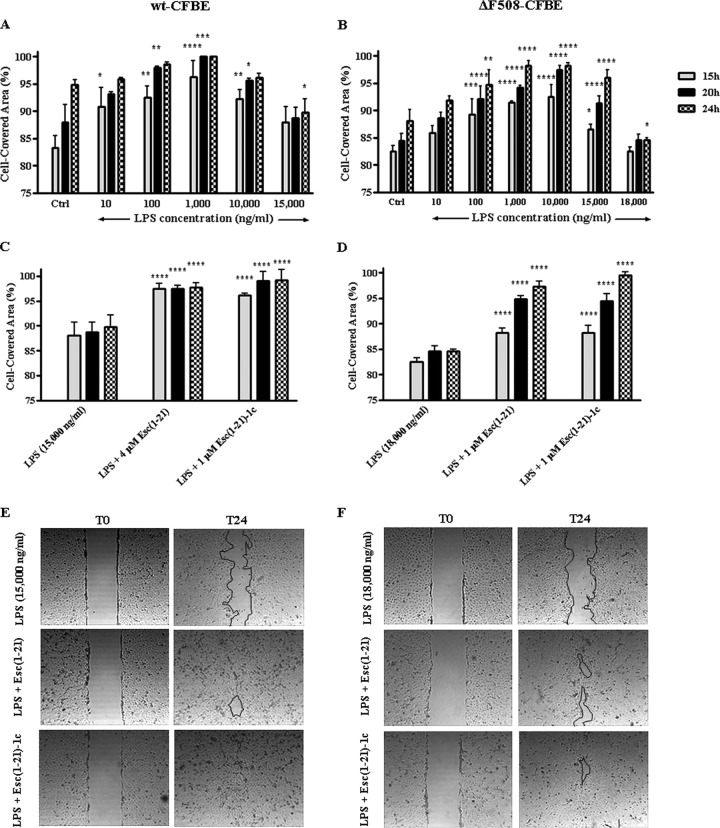

It is well known that following bacterial death or division, LPS (the major component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria) is released from the bacterial cell wall (6, 47). Recently, as described in reference 48, it was demonstrated that the presence of nontoxic levels of P. aeruginosa LPS accelerates wound repair in airway epithelial cells. We therefore analyzed the effect of different concentrations of P. aeruginosa LPS on the migratory activity of both wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE. As illustrated in Fig. 4A and B, within 20 h LPS promoted the closure of a 500-μm-wide gap created in a monolayer of wt-CFBE or ΔF508-CFBE cells at an optimal dose of 1,000 ng/ml or in the range of 1,000 to 10,000 ng/ml, respectively. Alternately, when LPS was used at higher concentrations (i.e., ≥15,000 ng/ml) that can be found in the sputum of CF patients with chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection (49), the coverage of the wounded area was significantly slackened (Fig. 4A and B). To verify whether this LPS concentration was lethal to the cells, a viability assay was carried out. However, no cell damage was observed up to 20 μg/ml LPS, as indicated by the percentage of metabolically active cells, which was comparable to that of control samples (data not shown). This correlates with the negligible toxicity already found for LPS on both normal human bronchial epithelial cells (48) and A549 cells (50).

FIG 4.

Effect of P. aeruginosa LPS alone (A and B) or in combination with Esc(1-21)/Esc(1-21)-1c (C to F) on the closure of a pseudo-wound field produced in a monolayer of wt-CFBE (A, C, and E) and ΔF508-CFBE (B, D, and F). Cells were seeded in each side of an Ibidi culture insert and grown to confluence; afterwards, they were left untreated or were treated with LPS or LPS plus peptide. Cells were photographed at the time of insert removal and examined for cell migration after 15, 20, and 24 h from addition of LPS or LPS plus peptide. The percentage of cell-covered area at each time point is reported on the y axis. The control (Ctrl) used was cells not treated with LPS or peptide. All data are the means from four independent experiments ± SEM. The levels of statistical significance of samples versus Ctrl (A and B) or LPS-treated (C and D) cells are P values of <0.05 (*), <0.01 (**), <0.001 (***), and <0.0001 (****). Micrographs showing representative results of wt-CFBE (E) or ΔF508-CFBE (F) before (T0) and 24 h after (T24) treatment with the combination of LPS and peptide (at the indicated concentrations in panels C or D) compared to samples treated with LPS are reported. The black line marks the cell-free area in samples after 24 h.

Interestingly, the induction of cell migration was clearly restored (Fig. 4C to F) when the LPS dosage that blocks the closure of the wounded field was used in combination with the optimal wound-healing concentration of Esc(1-21)-1c (1 μM). A similar effect was noted when the inhibitory concentration of LPS was mixed with a concentration of Esc(1-21) lower than its optimal dosage in promoting migration of wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE cells (4 μM and 1 μM, respectively) (Fig. 4C to F).

Mechanism of peptide-induced cell migration.

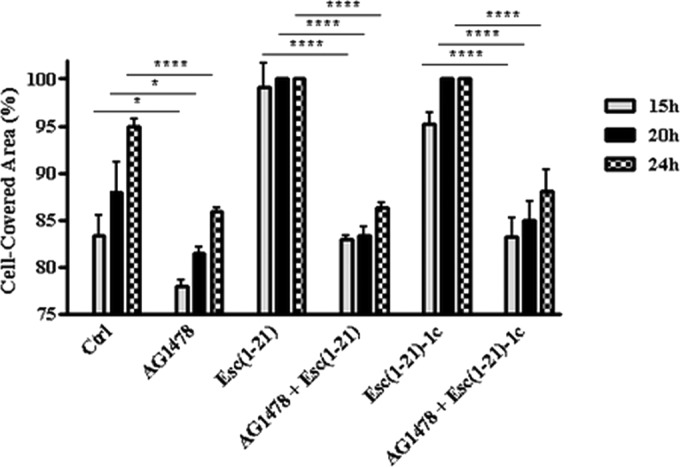

The airways of healthy or CF human subjects express EGFR (42), which is involved in the repair of damaged airway epithelium (51). Hence, we examined whether the peptide-promoted cell migration was a process mediated by the EGFR signaling pathway. For that purpose, we pretreated wt-CFBE cells with 5 μM AG1478, a selective inhibitor of EGFR tyrosine kinase (52), before adding each of the two peptides at their optimal concentrations in stimulating cell migration [10 μM and 1 μM for Esc(1-21) and Esc(1-21)-1c, respectively]. A clear inhibition of pseudo-wound closure was observed, as was shown by the significantly lower percentages of cell-covered area at all time intervals (15 h, 20 h, and 24 h), with respect to the results found when the bronchial cells were not preincubated with the inhibitor (Fig. 5). These results highlight the involvement of EGFR in the peptide-induced migration of bronchial cells. Similar results were obtained with the mutant ΔF508-CFBE (data not shown).

FIG 5.

Effect of AG1478 inhibitor on the peptide-mediated migration of wt-CFBE cells. Before removing the Ibidi culture insert, cells were preincubated with 5 μM AG1478 for 30 min and subsequently treated with 10 μM Esc(1-21) or 1 μM Esc(1-21)-1c. Some samples were treated with the peptide alone at the same concentration or with 5 μM AG1478. Cells incubated with MEMg served as a control (Ctrl). Samples were photographed at different time intervals as indicated, and the percentage of cell-covered area was calculated and reported on the y axis. The data are the means from four independent experiments ± SEM. The levels of statistical significance between Ctrl and AG1478-treated samples or between samples pretreated with AG1478 before incubation with the peptide and those treated with the peptide alone at the corresponding time intervals are P values of <0.05 (*) and <0.0001 (****).

Peptide distribution within bronchial cells.

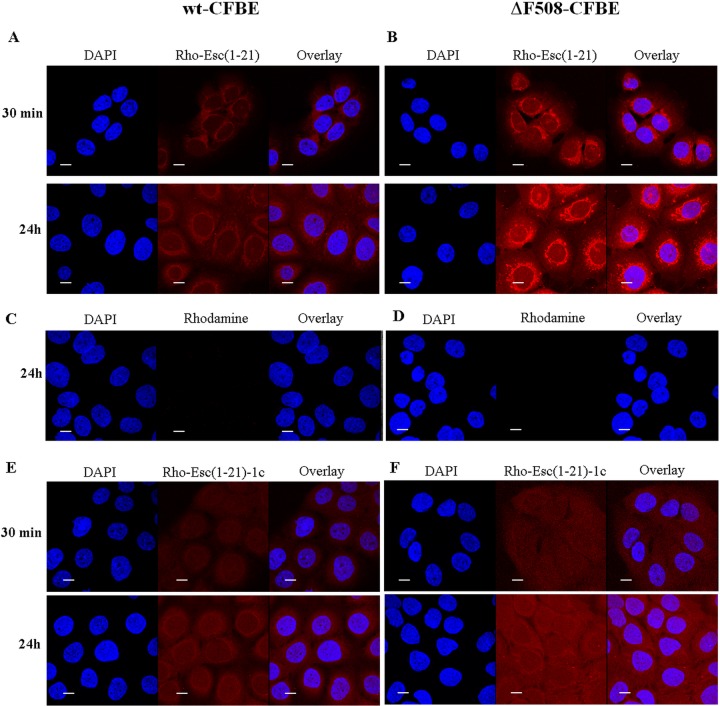

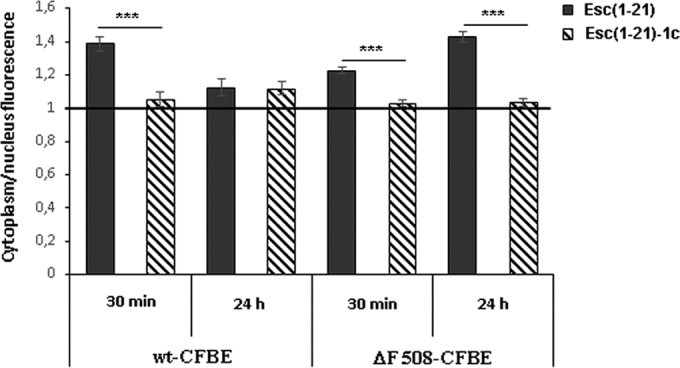

In order to know the peptides' distribution in wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE cells, we used confocal microscopy and rhodamine-labeled peptides. As reported in Fig. 6A and B, rho-Esc(1-21) was mainly aligned to the perinuclear region of the cell already after 30 min from its addition, as well as after 24 h. To address the possibility that rhodamine facilitated the uptake of the peptide, we also used the rhodamine dye not conjugated to the peptide. However, rhodamine was not observed in the bronchial cells, as revealed by the lack of fluorescence inside them (Fig. 6C and D). In comparison, in the case of rho-Esc(1-21)-1c, the fluorescence intensity appeared to be evenly distributed within the cytosol and nucleus (Fig. 6E and F). These findings were corroborated by the quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity of the two peptides between the cytoplasm and nucleus in both types of cells (Fig. 7).

FIG 6.

Confocal laser-scanning microscopy images of wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE cells treated with rho-Esc(1-21) (A and B), rhodamine alone (C and D), or rho-Esc(1-21)-1c (E and F) at different times. After treatment with the peptide (or rhodamine), cells were stained with DAPI for nucleus detection. DAPI fluorescence, rhodamine-labeled peptide (or rhodamine) signal, and the overlay of the two fluorescent probes are shown. All images are z sections taken from the mid-cell height. All bars represent 10 μm.

FIG 7.

Peptide distribution between cytoplasm and nucleus in wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE cells. Each peptide was tested on a minimum of 35 cells. The ratio between the fluorescence intensity of rhodamine-labeled peptides in the cytoplasm versus the nucleus was calculated for each cell, and the mean ± SEM value was reported on the y axis. If the ratio is equal to 1, this means that the peptide is evenly distributed all over the cell. When the ratio is higher than 1, the amount of fluorescent peptide is higher in the cytoplasm than the nucleus. The level of statistical significance between the calculated ratios of the two peptides at different time points is indicated as a P value of <0.001 (***).

Peptides' susceptibility to human and P. aeruginosa elastase.

One of the main drawbacks in using AMPs for treatment of P. aeruginosa lung infection is their susceptibility to enzymatic degradation (53, 54). In particular, the lung environment of CF patients is rich in proteases, i.e., elastase from host neutrophils and also from P. aeruginosa (55–57). Therefore, the stability of the two peptides in the presence of both enzymes was studied. When elastase from human leukocytes was used, Esc(1-21) was completely degraded within 5 h (Table 1; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast, the diastereomer was highly stable, with 78% and 13% of nondegraded peptide after 5 h and 24 h of incubation, respectively (Table 1). Mass spectrometry analysis confirmed the presence of one main peak at 2,185 Da corresponding to the calculated molecular mass of Esc(1-21)-1c (see Fig. S2). In comparison, when the human cathelicidin AMP LL-37 was used as a reference, 44% of the peptide remained after 5 h of treatment but nothing was found after 24 h (Table 1). When P. aeruginosa elastase was used, both LL-37 and Esc(1-21) were completely degraded within 5 h (Table 1), while in the case of Esc(1-21)-1c about 91% and 77% of nondegraded peptide was detected after 5 h and 24 h, respectively (33% after 48 h, data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Peptide amount after 5 and 24 h of incubation with human and P. aeruginosa elastase at 37°C

| Peptide designation | Peptide remaininga (%) by elastase type |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human |

P. aeruginosa

|

|||

| 5 h | 24 h | 5 h | 24 h | |

| Esc(1-21) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Esc(1-21)-1c | 78 | 13 | 91 | 77 |

| LL-37 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Peptide amounts were determined by the peak areas of the RP-HPLC relative to those of the control peptide (dissolved in buffer) at 0 min (set as 100%).

Interestingly, mass spectrometry analysis of the samples revealed the presence of peaks with different molecular masses than those found after treatment with human elastase (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), indicating different cleavage sites by the two elastases either in the two esculentin isoforms (see Fig. S2 and S3) or in LL-37 (see Fig. S4 and S5). Importantly, the main cleavage sites by human and bacterial elastase in Esc(1-21) were between Ile16 and Ser17 or between Asn13 and Leu14, respectively. Note that these two peptide bonds flank each of the two d-amino acids present in Esc(1-21)-1c (i.e., d-Leu14 and d-Ser17), thus preventing their proteolytic cleavage by both enzymes compared to the all-l peptide.

DISCUSSION

The airway epithelial surface represents an important place where the host breaks off signals from inhaled microbial pathogens and activates defense mechanisms to combat infections, especially in chronic diseases. However, administration of exogenous molecules endowed with anti-infective and/or immunomodulatory properties are highly needed to speed up the recovery process (58). Nevertheless, the challenge of treatment of respiratory infections has been compounded by the increasing resistance of pathogens to the commonly used drugs. Thus, new candidates are urgently needed, among which AMPs represent a promising alternative. With respect to this, Esc(1-21) and primarily its diastereomer Esc(1-21)-1c have several advantages that support their development as new antipseudomonal agents (6). However, no studies were reported on the ability of these two peptides to clear intracellular Pseudomonas, and only very limited information is documented for other AMPs with reference to this matter. Furthermore, the ability of AMPs to stimulate migration of lung epithelial cells in the context of a bacterial infection (e.g., in the presence of pathogen-associated molecular patterns, such as LPS) should be investigated in an attempt to develop a new drug that also has the ability to restore the normal architecture of the injured lung tissue. To the best of our knowledge, this has not yet been investigated for AMPs.

Here, we demonstrated the killing of intracellular Pseudomonas in bronchial cells with functional or mutated CFTR upon 1 h of exposure to the esculentin peptides. A significantly higher efficacy is displayed by the diastereomer Esc(1-21)-1c.

Note that conventional antibiotics (e.g., penicillins, cephalosporins, and aminoglycosides) are not ideal choices for treating invasive infections due to their inability to penetrate the plasma membrane (59, 60). An exception is fluoroquinolones, e.g., ciprofloxacin (61), which is currently used due to its strong activity against Gram-negative bacteria in spite of its toxicity (62) and the increasing number of bacteria that are resistant to it (63). Remarkably, the diastereomer had activity comparable to that of ciprofloxacin, which was found to cause ∼64%, 77%, and 98% killing of intracellular bacteria when tested under our conditions on infected ΔF508-CFBE at 1 μM, 5 μM, and 15 μM, respectively (data not shown).

By means of rhodamine-labeled peptides and confocal microscopy analysis, we visualized an intracellular localization of the two molecules in which Esc(1-21) has a prevalent perinuclear distribution. No vesicular pattern of fluorescence was observed, excluding an endocytotic mechanism of peptide uptake, which was shown in the case of Syn B peptides (64) and LL-37 in A549 cells after 30 min of incubation (65). A plausible explanation is that both esculentin isomers enter the cell by a self-translocation process through peptide-induced membrane lipid destabilization without affecting cell viability (66). Indeed, when tested at noncytotoxic concentrations, the peptides were able to perturb the membranes of both wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE cells, as indicated by the increased fluorescence intensity of the small-sized membrane-impermeable dye Sytox green, upon peptides' addition to the cells (data not shown). This reflects the intracellular influx of Sytox green, presumably due to a mild membrane destabilization caused by the peptides during their translocation across the cytoplasmic/nuclear membrane into the cytosol/nucleus, respectively. Overall, we can assume that the clearance of intracellular Pseudomonas is due mainly to the interaction of the internalized peptides with the bacterial cells. A possible reason for the weaker efficacy of the all-l peptide Esc(1-21) in killing intracellular bacteria compared to its diastereomer is related to a stereochemical binding of Esc(1-21), but not Esc(1-21)-1c, to intracellular components, making it less available. In addition, Esc(1-21) is expected to be more susceptible to virulence factors, i.e., proteases released from intracellular P. aeruginosa. It is worth mentioning that the fluorescence intensity cannot tell us if the peptide is intact or partially degraded or whether it is present in an inactive form. Furthermore, the intranuclear location of the peptides suggest additional mechanisms to boost their antimicrobial potency, e.g., by directly/indirectly upregulating the expression of genes involved in host cell protection from microbial pathogens.

Another important finding in this study is the pseudo-wound-healing activity of the two peptides in both wt-CFBE and ΔF508-CFBE cells. As reported for A549 cells (36), the diastereomer is more effective in inducing reepithelialization of the wounded area, with a mechanism that implies an EGFR-mediated signaling pathway. We think that the lower wound-healing efficacy of the more helical Esc(1-21) compared to its diastereomer is a consequence of a stronger alteration of the phospholipid membrane region where EGF receptors are located. This would impair the binding of ligands to EGFR with a resulting weaker EGFR activation (36). However, the discrepancy between the two peptides in the wound-healing activity may also be related to a difference in the binding affinity of the two AMPs to the target receptor (presumably EGFR or membrane-bound metalloproteases [42, 66]). Furthermore, we cannot rule out the participation of alternative processes in controlling migration of bronchial cells. One of them could imply CFTR (especially in mutant cells) via a yet-to-be-discovered mechanism.

Here, we also demonstrated for the first time that bronchial cell migration stimulated by both esculentin isomers is maintained in the presence of high concentrations of LPS, presumably found in CF sputum (49), and different plausible mechanisms underlying such events are discussed below. LPS has been found to regulate wound repair in airway epithelial cells through a signaling pathway triggered by its binding to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) (expressed on the airway epithelial cells) and implicating activation of EGFR (48, 67). Note that LPS binds TLR-4 in its monomeric form (68). However, in aqueous environments, micellar assemblies of LPS are formed above its critical micellar concentrations (≥14,000 ng/ml) (68, 69). This may hamper the binding of LPS to TLR-4, thus explaining the inhibitory pseudo-wound-healing effect of LPS when used at high concentrations (i.e., ≥15,000 ng/ml) (Fig. 4A and B). Note also that there is a reestablishment of the migratory activity of bronchial cells when LPS (at its inhibitory concentration) is combined with Esc(1-21)-1c (at the optimal wound-healing dosage of 1 μM) (Fig. 4C and D). This is presumably due to the diastereomer-induced reepithelialization process regardless of the presence of LPS. In contrast, a different mechanism would likely account for the increased pseudo-wound-healing activity of Esc(1-21) when combined with high concentrations of LPS (Fig. 4C and D) compared to the results found when the peptide is used alone at the same concentrations (Fig. 3A and B). As previously reported, Esc(1-21) is more efficient than its diastereomer in disrupting LPS micelles (36). Such LPS disaggregation might be sufficient to reset the availability of LPS monomers for an optimal binding to TLR-4 and retrieval/improvement of wound-healing activity.

Importantly, we also proved that the incorporation of two d-amino acids at specific positions in Esc(1-21) makes the peptide significantly more resistant to degradation by both human and bacterial elastases.

In conclusion, we have shown that (i) a derivative of a frog skin-derived AMP, and particularly its designed diastereomer, rapidly kills Pseudomonas cells once internalized in CF bronchial cells; (ii) the peptides accelerate bronchial cell migration under conditions that better simulate lung infection in CF (e.g., in the presence of LPS); and (iii) the diastereomer has an overall higher efficacy than the all-l parent isoform. These findings are very important for the generation of new antimicrobial drugs that not only eliminate microbial pathogens but also would recover the tissue's integrity.

In this specific case, the aforementioned properties of Esc(1-21)-1c, together with its higher biostability to elastases and undetectable cytotoxicity compared to wild-type Esc(1-21), support further studies toward the development and usage of the former peptide for local treatment of P. aeruginosa-induced lung infections.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alessandra Bragonzi (San Raffaele Institute, Milan, Italy) and Burkhard Tummler (Klinische Forschergruppe, OE 6710, Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Hannover, Germany) for the P. aeruginosa clinical isolate. We also thank the FFC Cell Culture Service.

Y. Shai is the holder of The Harold S. and Harriet B. Brady Professorial Chair in Cancer Research.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from Sapienza Università di Roma (Sapienza University of Rome) and the Italian Foundation for Cystic Fibrosis (project FFC#11/2014; adopted by FFC Delegations from Siena, Sondrio Valchiavenna, Cerea Il Sorriso di Jenny, and Pavia). Part of this work was also supported by FILAS Grant Prot. FILAS-RU-2014–1020.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00904-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hancock RE, Speert DP. 2000. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and impact on treatment. Drug Resist Updat 3:247–255. doi: 10.1054/drup.2000.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mah TF, Pitts B, Pellock B, Walker GC, Stewart PS, O'Toole GA. 2003. A genetic basis for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm antibiotic resistance. Nature 426:306–310. doi: 10.1038/nature02122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drenkard E, Ausubel FM. 2002. Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature 416:740–743. doi: 10.1038/416740a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart PS, Costerton JW. 2001. Antibiotic resistance of bacteria in biofilms. Lancet 358:135–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mangoni ML, Luca V, McDermott AM. 2015. Fighting microbial infections: a lesson from amphibian skin-derived esculentin-1 peptides. Peptides 71:286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larrosa M, Truchado P, Espin JC, Tomas-Barberan FA, Allende A, Garcia-Conesa MT. 2012. Evaluation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAO1) adhesion to human alveolar epithelial cells A549 using SYTO 9 dye. Mol Cell Probes 26:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millar FA, Simmonds NJ, Hodson ME. 2009. Trends in pathogens colonising the respiratory tract of adult patients with cystic fibrosis, 1985-2005. J Cyst Fibros 8:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerem B, Rommens JM, Buchanan JA, Markiewicz D, Cox TK, Chakravarti A, Buchwald M, Tsui LC. 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: genetic analysis. Science 245:1073–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.2570460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welsh M, Tsui L, Boat T, Beaudet A. 1995. Cystic fibrosis, p 3799–3863. In Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D (ed), The metabolic bases of inherited disease, 7th ed McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans CM, Koo JS. 2009. Airway mucus: the good, the bad, the sticky. Pharmacol Ther 121:332–348. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chace KV, Flux M, Sachdev GP. 1985. Comparison of physicochemical properties of purified mucus glycoproteins isolated from respiratory secretions of cystic fibrosis and asthmatic patients. Biochemistry 24:7334–7341. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreau-Marquis S, Stanton BA, O'Toole GA. 2008. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation in the cystic fibrosis airway. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 21:595–599. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bals R, Weiner DJ, Wilson JM. 1999. The innate immune system in cystic fibrosis lung disease. J Clin Investig 103:303–307. doi: 10.1172/JCI6277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiappini E, Taccetti G, de Martino M. 2014. Bacterial lung infections in cystic fibrosis patients: an update. Pediatr Infect Dis J 33:653–654. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirakata Y, Izumikawa K, Yamaguchi T, Igimi S, Furuya N, Maesaki S, Tomono K, Yamada Y, Kohno S, Yamaguchi K, Kamihira S. 1998. Adherence to and penetration of human intestinal Caco-2 epithelial cell monolayers by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun 66:1748–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chi E, Mehl T, Nunn D, Lory S. 1991. Interaction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with A549 pneumocyte cells. Infect Immun 59:822–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyczak JB, Cannon CL, Pier GB. 2000. Establishment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: lessons from a versatile opportunist. Microbes Infect 2:1051–1060. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hart CA, Winstanley C. 2002. Persistent and aggressive bacteria in the lungs of cystic fibrosis children. Br Med Bull 61:81–96. doi: 10.1093/bmb/61.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pier GB, Grout M, Zaidi TS. 1997. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is an epithelial cell receptor for clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 94:12088–12093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pier GB, Grout M, Zaidi TS, Olsen JC, Johnson LG, Yankaskas JR, Goldberg JB. 1996. Role of mutant CFTR in hypersusceptibility of cystic fibrosis patients to lung infections. Science 271:64–67. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5245.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esen M, Grassme H, Riethmuller J, Riehle A, Fassbender K, Gulbins E. 2001. Invasion of human epithelial cells by Pseudomonas aeruginosa involves src-like tyrosine kinases p60Src and p59Fyn. Infect Immun 69:281–287. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.281-287.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darling KE, Evans TJ. 2003. Effects of nitric oxide on Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection of epithelial cells from a human respiratory cell line derived from a patient with cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun 71:2341–2349. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2341-2349.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darling KE, Dewar A, Evans TJ. 2004. Role of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by polarized respiratory epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol 6:521–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ko YH, Delannoy M, Pedersen PL. 1997. Cystic fibrosis, lung infections, and a human tracheal antimicrobial peptide (hTAP). FEBS Lett 405:200–208. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben Haj Khalifa A, Moissenet D, Vu Thien H, Khedher M. 2011. Virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and modes of regulation. Ann Biol Clin 69:393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sana TG, Baumann C, Merdes A, Soscia C, Rattei T, Hachani A, Jones C, Bennett KL, Filloux A, Superti-Furga G, Voulhoux R, Bleves S. 2015. Internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO1 into epithelial cells is promoted by interaction of a T6SS effector with the microtubule network. mBio 6:e00712. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00712-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinch KS, Frimodt-Moller N, Hoiby N, Kristensen HH. 2009. Influence of antidrug antibodies on plectasin efficacy and pharmacokinetics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4794–4800. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00440-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haney EF, Hancock RB. 2013. Peptide design for antimicrobial and immunomodulatory applications. Biopolymers 100:572–583. doi: 10.1002/bip.22250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cruz J, Ortiz C, Guzman F, Fernandez-Lafuente R, Torres R. 2014. Antimicrobial peptides: promising compounds against pathogenic microorganisms. Curr Med Chem 21:2299–2321. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140217110155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansour SC, Pena OM, Hancock RE. 2014. Host defense peptides: front-line immunomodulators. Trends Immunol 35:443–450. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epand RM, Vogel HJ. 1999. Diversity of antimicrobial peptides and their mechanisms of action. Biochim Biophys Acta 1462:11–28. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(99)00198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shai Y. 2002. Mode of action of membrane active antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers 66:236–248. doi: 10.1002/bip.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Islas-Rodriguez AE, Marcellini L, Orioni B, Barra D, Stella L, Mangoni ML. 2009. Esculentin 1-21: a linear antimicrobial peptide from frog skin with inhibitory effect on bovine mastitis-causing bacteria. J Pept Sci 15:607–614. doi: 10.1002/psc.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luca V, Stringaro A, Colone M, Pini A, Mangoni ML. 2013. Esculentin(1-21), an amphibian skin membrane-active peptide with potent activity on both planktonic and biofilm cells of the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Mol Life Sci 70:2773–2786. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Di Grazia A, Cappiello F, Cohen H, Casciaro B, Luca V, Pini A, Di YP, Shai Y, Mangoni ML. 2015. d-Amino acids incorporation in the frog skin-derived peptide esculentin-1a(1-21)NH is beneficial for its multiple functions. Amino Acids 47:2505–2519. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-2041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bebok Z, Collawn JF, Wakefield J, Parker W, Li Y, Varga K, Sorscher EJ, Clancy JP. 2005. Failure of cAMP agonists to activate rescued deltaF508 CFTR in CFBE41o-airway epithelial monolayers. J Physiol 569:601–615. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.096669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lore NI, Cigana C, De Fino I, Riva C, Juhas M, Schwager S, Eberl L, Bragonzi A. 2012. Cystic fibrosis-niche adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa reduces virulence in multiple infection hosts. PLoS One 7:e35648. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bragonzi A, Paroni M, Nonis A, Cramer N, Montanari S, Rejman J, Di Serio C, Doring G, Tummler B. 2009. Pseudomonas aeruginosa microevolution during cystic fibrosis lung infection establishes clones with adapted virulence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180:138–145. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1943OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grieco P, Carotenuto A, Auriemma L, Limatola A, Di Maro S, Merlino F, Mangoni ML, Luca V, Di Grazia A, Gatti S, Campiglia P, Gomez-Monterrey I, Novellino E, Catania A. 2013. Novel alpha-MSH peptide analogues with broad spectrum antimicrobial activity. PLoS One 8:e61614. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Grazia A, Cappiello F, Imanishi A, Mastrofrancesco A, Picardo M, Paus R, Mangoni ML. 2015. The frog skin-derived antimicrobial peptide esculentin-1a(1-21)NH2 promotes the migration of human HaCaT keratinocytes in an EGF receptor-dependent manner: a novel promoter of human skin wound healing? PLoS One 10:e0128663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim S, Beyer BA, Lewis C, Nadel JA. 2013. Normal CFTR inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent pro-inflammatory chemokine production in human airway epithelial cells. PLoS One 8:e72981. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Renier M, Tamanini A, Nicolis E, Rolfini R, Imler JL, Pavirani A, Cabrini G. 1995. Use of a membrane potential-sensitive probe to assess biological expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Hum Gene Ther 6:1275–1283. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.10-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamai H, Keyserman F, Quittell LM, Worgall TS. 2009. Defective CFTR increases synthesis and mass of sphingolipids that modulate membrane composition and lipid signaling. J Lipid Res 50:1101–1108. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800427-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trinh NT, Bardou O, Prive A, Maille E, Adam D, Lingee S, Ferraro P, Desrosiers MY, Coraux C, Brochiero E. 2012. Improvement of defective cystic fibrosis airway epithelial wound repair after CFTR rescue. Eur Respir J 40:1390–1400. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00221711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schiller KR, Maniak PJ, O'Grady SM. 2010. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is involved in airway epithelial wound repair. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299:C912–C921. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00215.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rietschel ET, Kirikae T, Schade FU, Mamat U, Schmidt G, Loppnow H, Ulmer AJ, Zahringer U, Seydel U, Di Padova F, Schreier M, Brade H. 1994. Bacterial endotoxin: molecular relationships of structure to activity and function. FASEB J 8:217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koff JL, Shao MX, Kim S, Ueki IF, Nadel JA. 2006. Pseudomonas lipopolysaccharide accelerates wound repair via activation of a novel epithelial cell signaling cascade. J Immunol 177:8693–8700. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bucki R, Byfield FJ, Janmey PA. 2007. Release of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 from DNA/F-actin bundles in cystic fibrosis sputum. Eur Respir J 29:624–632. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Byfield FJ, Kowalski M, Cruz K, Leszczynska K, Namiot A, Savage PB, Bucki R, Janmey PA. 2011. Cathelicidin LL-37 increases lung epithelial cell stiffness, decreases transepithelial permeability, and prevents epithelial invasion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Immunol 187:6402–6409. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burgel PR, Nadel JA. 2004. Roles of epidermal growth factor receptor activation in epithelial cell repair and mucin production in airway epithelium. Thorax 59:992–996. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.018879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gan HK, Walker F, Burgess AW, Rigopoulos A, Scott AM, Johns TG. 2007. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 increases the formation of inactive untethered EGFR dimers. Implications for combination therapy with monoclonal antibody 806. J Biol Chem 282:2840–2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Midura-Nowaczek K, Markowska A. 2014. Antimicrobial peptides and their analogs: searching for new potential therapeutics. Perspect Medicin Chem 6:73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nguyen LT, Chau JK, Perry NA, de Boer L, Zaat SA, Vogel HJ. 2010. Serum stabilities of short tryptophan- and arginine-rich antimicrobial peptide analogs. PLoS One 5:e12684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu H, Lazarus SC, Caughey GH, Fahy JV. 1999. Neutrophil elastase and elastase-rich cystic fibrosis sputum degranulate human eosinophils in vitro. Am J Physiol 276:L28–L34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lovewell RR, Patankar YR, Berwin B. 2014. Mechanisms of phagocytosis and host clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 306:L591–L603. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00335.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mariencheck WI, Alcorn JF, Palmer SM, Wright JR. 2003. Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase degrades surfactant proteins A and D. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 28:528–537. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0141OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morris CJ, Beck K, Fox MA, Ulaeto D, Clark GC, Gumbleton M. 2012. Pegylation of antimicrobial peptides maintains the active peptide conformation, model membrane interactions, and antimicrobial activity while improving lung tissue biocompatibility following airway delivery. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:3298–3308. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06335-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brayton JJ, Yang Q, Nakkula RJ, Walters JD. 2002. An in vitro model of ciprofloxacin and minocycline transport by oral epithelial cells. J Periodontol 73:1267–1272. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.11.1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonventre PF, Hayes R, Imhoff J. 1967. Autoradiographic evidence for the impermeability of mouse peritoneal macrophages to tritiated streptomycin. J Bacteriol 93:445–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chadwick PR, Mellersh AR. 1987. The use of a tissue culture model to assess the penetration of antibiotics into epithelial cells. J Antimicrob Chemother 19:211–220. doi: 10.1093/jac/19.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ilgin S, Can OD, Atli O, Ucel UI, Sener E, Guven I. 2015. Ciprofloxacin-induced neurotoxicity: evaluation of possible underlying mechanisms. Toxicol Mech Methods 25:374–381. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2015.1026008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yayan J, Ghebremedhin B, Rasche K. 2015. No outbreak of vancomycin and linezolid resistance in Staphylococcal pneumonia over a 10-year period. PLoS One 10:e0138895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Drin G, Cottin S, Blanc E, Rees AR, Temsamani J. 2003. Studies on the internalization mechanism of cationic cell-penetrating peptides. J Biol Chem 278:31192–31201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lau YE, Rozek A, Scott MG, Goosney DL, Davidson DJ, Hancock RE. 2005. Interaction and cellular localization of the human host defense peptide LL-37 with lung epithelial cells. Infect Immun 73:583–591. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.1.583-591.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Reddy P, Stocking KL, Sunnarborg SW, Lee DC, Russell WE, Castner BJ, Johnson RS, Fitzner JN, Boyce RW, Nelson N, Kozlosky CJ, Wolfson MF, Rauch CT, Cerretti DP, Paxton RJ, March CJ, Black RA. 1998. An essential role for ectodomain shedding in mammalian development. Science 282:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shao MX, Ueki IF, Nadel JA. 2003. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-converting enzyme mediates MUC5AC mucin expression in cultured human airway epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:11618–11623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534804100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park BS, Lee JO. 2013. Recognition of lipopolysaccharide pattern by TLR4 complexes. Exp Mol Med 45:e66. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Santos NC, Silva AC, Castanho MA, Martins-Silva J, Saldanha C. 2003. Evaluation of lipopolysaccharide aggregation by light scattering spectroscopy. Chembiochem 4:96–100. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200390020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.