Abstract

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a re-emerging alphavirus that causes debilitating acute and chronic arthritis. Infection by CHIKV induces a robust immune response that is characterized by production of type I interferons, recruitment of innate and adaptive immune cells, and development of neutralizing antibodies. Despite this response, chronic arthritis can develop in some individuals, which may be due to a failure to eliminate viral RNA and antigen and/or persistent immune responses that cause chronic joint inflammation. In this review, based primarily on advances from recent studies in mice, we discuss the innate and adaptive immune factors that control CHIKV dissemination and clearance or contribute to pathogenesis.

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is a re-emerging mosquito-borne enveloped alphavirus in the Togaviridae family. CHIKV has a single-stranded positive sense RNA genome that encodes four non-structural proteins (nsP1, nsP2, nsP3, and nsP4) and five structural proteins (capsid, E3, E2, 6K and E1) from two open reading frames. CHIKV was first isolated in Tanzania in 1952 and has caused explosive outbreaks throughout Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and Polynesia (1, 2). CHIKV emerged in the Caribbean in 2013 and has spread throughout Central and South America with autochthonous transmission reported in Florida (3). The outbreak in the Americas has resulted in more than 1.8 million suspected cases (4). Historically, CHIKV was transmitted principally by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, but in 2006 the virus acquired a single mutation (A226V) in the E1 protein that facilitated enhanced replication and transmission in Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, which expanded its geographical range (5). There are three genotypes of CHIKV that are highly conserved, with 95.2% to 97% identity at the amino acid level: the East/Central/South African and Asian genotypes are more closely related than the more distantly related West African genotype (6, 7). Following a short incubation period after mosquito bite, CHIKV infection in humans can cause fever, rash, malaise, myalgia, and debilitating polyarthralgia and polyarthritis that usually lasts for one to four weeks (8). Depending on the study, approximately 10 to 60% of affected individuals develop chronic arthritis that lasts for months to years following infection (9–12). CHIKV infection rarely results in mortality, although it has been reported primarily in the elderly, infants, and immunocompromised (13–15). Currently there are no approved vaccines or therapeutics to prevent CHIKV infection or treat disease at the acute or chronic stages.

Over the past decade, the immunobiology of CHIKV infection and disease has been studied intensively in laboratory animal models primarily in mice but also in some non-human primate species. Experimental infection of different strains of immunocompetent mice (e.g., C57BL/6, CD1, IRC) results in an acute disease similar to humans including high viremia, viral replication in joint and muscle tissues, synovitis, and myositis (16–19). After inoculation of CHIKV into the skin, the virus likely replicates in fibroblasts, mesenchymal cells, and osteoblasts (20, 21). CHIKV induces a local cytokine and chemokine response that recruits natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, inflammatory monocytes, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (16, 17, 20). Damage from viral replication and immune cell infiltration results in local edema, extensive myofiber degeneration, and injury and loss of mesenchymal cells lining the synovium and periosteum (22). Moreover, CHIKV infection of osteoblasts elevates the ratio of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) to osteoprotegerin (OPG) in the ankle and knee, which increase osteoclast generation and can promote bone loss (23). In mice, CHIKV infection causes a biphasic pattern of swelling in the ipsilateral inoculated foot with a small peak between 2–3 days post-infection (dpi) and a second, larger peak at 6–7 dpi (17, 24). The first peak is most likely due to extensive viral replication in the foot which results in cell death, cytokine production, and tissue edema. The second peak occurs as infectious virus is cleared from the blood and within tissues, and is associated with the influx of inflammatory cells into joints of the foot and surrounding tissues, causing more edema, myositis, and synovitis. This histological observation suggests that the second, more prominent peak is driven by immune-mediated response and damage. Although infectious virus is cleared by 7 dpi, CHIKV RNA can be detected in joints (e.g. foot/ankles, and wrists) for at least 4 weeks post-infection. Mice infected with a CHIKV strain encoding firefly luciferase showed bioluminescent signal in the foot at 45 dpi (25). Using mice lacking specific factors of innate and adaptive immunity, some of the key immune correlates of CHIKV disease pathogenesis and protection have been identified (Table 1 and Fig 1) and related to observations from human cohort studies.

Table 1.

Clinical, immune, and viral phenotypes after CHIKV infection in mice

| Immune function and mouse strain (age)a,b |

Virus strain (genotype) |

Clinical/ Swelling/ Pathology |

Virological and immune characterizationb |

Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | ||||

| Neonatal (9–12 d) |

06.21 (ECSA); CHIKV-21 (ECSA) |

40–60% survival |

V- detectable in muscle, serum, brain, liver, lung I- robust cytokine and IFN response by 24 hpi |

(32, 34, 42) |

| Young (3–4 w) | SL15649 (ECSA); AF15561 (Asian) |

Inoculated foot swelling; edema, tenosynovitis, tendonitis |

V- detectable in foot, serum, muscle, liver, brain; persistent RNA in joints and spleen I- innate and adaptive cell infiltrations; IgM and IgG produced |

(16, 18, 63) |

| Adult (6–12 w) | Asian isolate; LR2006-OPY1 (ECSA) |

Inoculated foot swelling; edema, arthritis, tenosynovitis (ECSA > Asian) |

V- detectable in serum, foot, muscle, spleen, LN, liver; persistent RNA in joints I- pro-inflammatory cytokine induction; innate and adaptive cell infiltration; IgG2c dominant |

(17, 80) |

|

Antiviral Pathways | ||||

| Tlr3−/− (young) | SGPO11 (ECSA) |

↑ foot swelling | V- ↑ viremia and tissue titers I- ↑ Infiltration of macrophages, neutrophils; ↓ CD4+ T cells; ↓ IgG neutralization |

(30) |

| Tlr3−/− | CHIKV-21 | ND | V- no Δ in titers (1–3 dpi) | (20) |

| Trif−/− (adult) | LR2006-OPY1 | ↑ foot swelling | V- ↑ viremia I- ↓ type I IFNs |

(31) |

|

Rig-I−/− (ICR/129/C57B L/6) |

CHIKV-21 | ND | V- no Δ in tissue, slight increase in viremia |

(20) |

|

Mda5−/− (ICR/129/C57B L/6) |

CHIKV-21 | ND | V- no Δ in viremia or tissues (72hpi) |

(20) |

| Mavs−/−(adult) | CHIKV-21; LR2006-OPY1 |

↑ foot swelling | V- ↑ viremia I- no type I IFNs |

(20, 31) |

| Myd88−/−(adult) | CHIKV-21; LR2006-OPY1 |

No Δ in foot swelling |

V- ↑ viremia and tissue titers I- ↓ type I IFNs |

(20, 31) |

| Irf3/7−/−(adult) | LR2006-OPY1; CHIKV-21 |

↑ foot swelling; 100% lethal |

V- ↑ tissue burden I- ↑ IL-6, TNF-α, IFNγ; no type I IFNs; shock syndrome |

(31, 32) |

| Irf3−/−(adult) | LR2006-OPY1; CHIKV-21 |

↑ foot swelling | V- no Δ in foot titer or viremia I- no Δ type I IFNs or no type I IFNs |

(31, 32) |

| Irf7−/−(adult) | LR2006-OPY1; CHIKV-21 |

↑ foot swelling | V- ↑ viremia; no Δ in foot titer I- no type I IFNs |

(31, 32) |

| Stat1−/−(129/Sv) | CHIKV-21, LR2006-OPY1, 37997 (WA) |

↑ foot swelling in ips & contra (LR); 100% lethal |

V- ↑ tissue titers | (20, 35) |

|

Ifnar1−/− (C57BL6, 129/Sv) (adult) |

CHIKV-21 | 100% lethal | V- ↑ viremia and tissue titers | (32, 34, 35) |

|

Rsad2−/− (young) |

SGP 011 (Asian) |

↑ foot swelling | V-↑ viremia late; ↑ foot titer I- ↑ F4/80+ macrophages |

(38) |

|

Gadd34−/− (neonatal) |

CHIKV-21 | 100% lethal | V- ↑ tissue titers I- ↓ Type I IFNs |

(36) |

| Ifitm3−/− (young) | LR2006-OPY1 | ↑ foot swelling | V- ↑ tissue titers I- ↑ macrophage infection |

(39) |

| Bst2−/− | 181/25 (Asian) | No swelling (attenuated virus) |

V- ↑ viremia and tissue titers I- ↓ type I IFNs and IFN-γ |

(40) |

|

Isg15−/− (neonatal) |

06.21 | 100% lethal | V- no Δ I- ↑ cytokines; shock syndrome |

(42) |

| Innate Cellular Responses | ||||

| Macrophage depletion (clodronate) (adult) |

LR2006-OPY1 | ↓ foot swelling | V- ↑ viremia (late) | (17) |

| Ccr2−/−(adult) | LR2006-OPY1 | ↑ foot swelling | V- no Δ I- ↑ neutrophils and eosinophils; ↑ inflammatory cytokines |

(53) |

| NK cell depletion (young) |

LR2006-OPY1; CNR20235 (Asian) |

↓ foot swelling early; no Δ (Asian) |

V-? | (59) |

| γδTCR−/− (young) |

SL15649 | ↑ foot swelling ↓ weight gain |

V- no Δ in viral burden or clearance I- ↑ inflammatory and regulatory monocytes; ↑ cytokines |

(61) |

| Adaptive Cellular Responses | ||||

|

Rag1−/−

or Rag2−/−(adult; young) |

LR2006-OPY1; SL15649, SGP11, AF15561 |

↓ foot swelling; chronic synovitis, tendonitis |

V- ↑ viremia (acute) and persistent virus in periphery and serum I- ↓ cellular infiltrates; ↑ in neutrophils (chronic) |

(18, 25, 62, 63) |

|

Cd8−/−or CD8 depletion (adult) |

SGP11; LR2006-OPY1- Fluc |

No Δ | V- no Δ | (25) |

| Cd4−/−(adult) | SGP11 | ↓ foot swelling | V- no Δ in viremia I- ↓ cellular infiltration in foot; ↓ antibody response |

(25, 80) |

| CD4+ T cell depletion (adult) |

SGP11; LR2006-OPY1- Fluc |

↓ foot swelling | V- no Δ in viremia I- ↓ recruitment of CD8+ T cells; no Δ in macrophages or neutrophils |

(25) |

| MhcII−/−(adult) | LR2006-OPY1 | ↓ foot swelling | V- no Δ in viremia I- no IgG1 produced; ↓ IgG2c; ↓cellular infiltrates |

(62) |

| Treg expansion (IL- 2/anti-IL-2 complex) (young) |

SGP011 | ↓ foot swelling | V- no Δ viremia I- ↓ pro-inflammatory cytokines; ↓ effector CD4+ T cells and proliferation |

(66) |

| Ifng−/−(adult) | SGP11 | Mild ↑ foot swelling |

V- ↑ viremia | (25) |

| µMT−/−(adult) | LR2006-OPY1; SGP11 |

↑ and prolonged foot swelling |

V- ↑ and chronic viremia I- No Δ in cellular infiltrates |

(62, 80) |

All mice are on the C57BL/6 background unless otherwise noted. The age of mice at time of infection is listed after genotype; if not, the age was not reported.

V, virologic; I, immune; ↑, increased; ↓, decreased; Δ, change; d, days; w, weeks; dpi, days post-infection; ND, no data

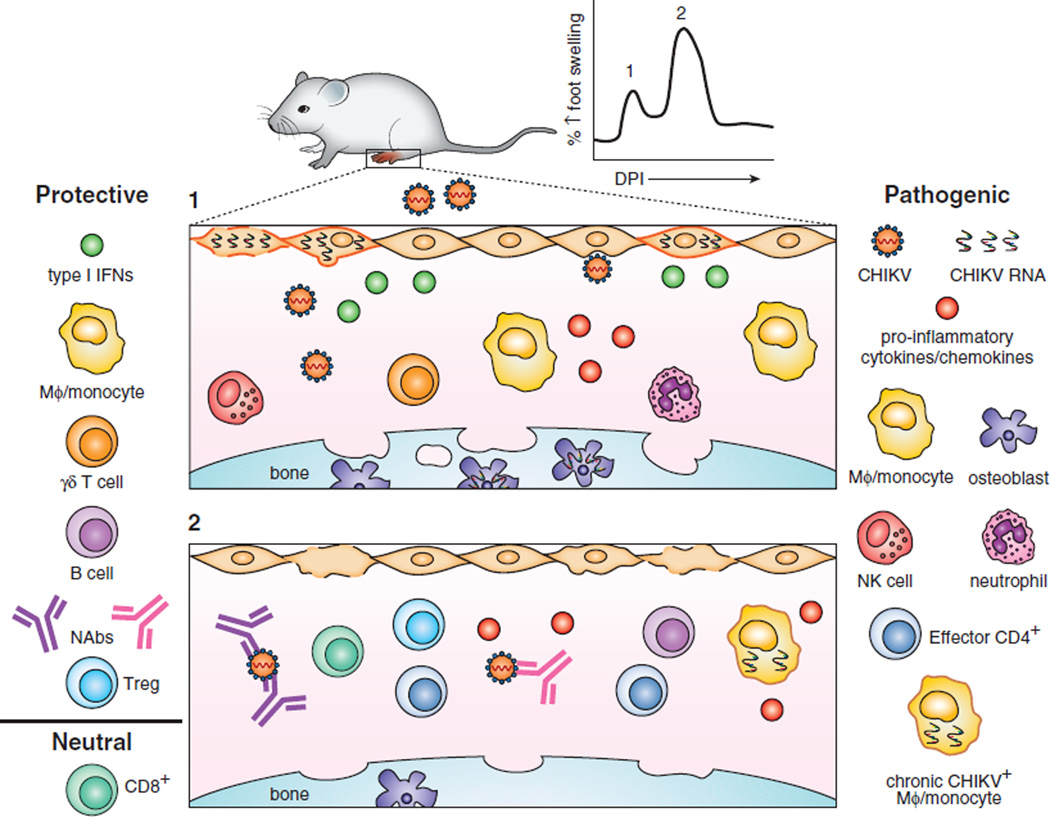

Figure 1.

Overview of CHIKV and immune-mediated pathogenesis in mice. CHIKV infection of the footpad results in edema and inflammation from viral infection, cell death, cytokine production, and immune cell infiltration. Foot swelling is biphasic with the first (1) peak occurring 2–3 dpi followed by a second (2) peak at 6–7 dpi. (1) CHIKV infects fibroblasts (orange cells), mesenchymal cells, and osteoblasts. In this figure, infection is indicated with viral RNA present inside a cell with a plasma membrane colored orange. PRRs are triggered during cellular infection resulting in activation of transcription factors, ultimately producing type I IFNs. Type I IFN and the ISG response are necessary to prevent severe disease. In addition, PRR and IFN signaling induce secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which recruit innate and adaptive immune cells to the site of infection driving inflammation. Depletion of NK cells reduces foot swelling suggesting a pathogenic role. Macrophages (MΦ) and inflammatory monocytes have dual protective and pathogenic roles in CHIKV arthritis. Depletion of macrophages reduces swelling, but also can result in a neutrophil-mediated immunopathogenesis. Osteoblasts can be infected by CHIKV, which promotes osteoclastogenesis and bone reabsorption. γδ+ T cells prevent monocyte recruitment and joint inflammation. (2) CHIKV infection induces a neutralizing antibody (NAb) response that eliminates infectious virus from circulation and tissues. Effector CD4+ T cells are recruited to musculoskeletal tissues and secrete IFN-γ. Depletion of CD4+ T cells results in reduced joint swelling. Enhancement of the FoxP3+ CD4+ Treg response results in reduced joint swelling, cytokine production, and effector CD4+ T cell activation. Surprisingly, CD8+ T cells do not seem to function in acute pathogenesis or viral clearance, at least in mice. CHIKV RNA and antigen persists in joint tissues for extended periods and may serve as pathogen-associated molecular patterns for chronic immune activation and inflammation. Macrophages and monocytes are suggested to be a reservoir for chronic infection.

Innate immune response to CHIKV infection

Recognition of CHIKV RNA and induction of antiviral pathways

The mammalian host response to CHIKV infection starts locally in the skin at the site of inoculation and also occurs in the underlying muscle and joint tissues (18, 26). The CHIKV RNA genome can trigger host pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) including endosomal Toll-like (TLR3 and TLR7) and cytoplasmic RIG-I-like (RIG-I and MDA5) receptors, which activate downstream adaptor molecules (e.g., TRIF, MyD88, and MAVS) to induce nuclear translocation of IRF3 and type I interferon (IFN)-dependent antiviral responses (27–29). While this scheme generally is accepted for many viruses, there are conflicting reports as to the necessity of individual PRRs in the antiviral response against CHIKV in mice. For example, one group showed a protective effect of TLR3, as Tlr3−/− mice sustained increased viremia and tissue viral burden with augmented foot swelling and edema, infiltration of CD11b+ F4/80+ macrophages and CD11b+ Ly6G+ neutrophils, and reduced numbers of CD4+ T cells (30). Depletion of the remaining CD4+ T cells in the Tlr3−/− mice diminished foot swelling but also reduced the number of infiltrating neutrophils; the authors suggested that the increased recruitment of neutrophils in the CHIKV-infected Tlr3−/− mice promotes the observed enhanced musculoskeletal inflammation (30). In this study, TLR3 stimulation in hematopoietic cells controlled CHIKV viremia, whereas TLR3 signaling in non-hematopoietic cells resulted in reduced clinical disease. Remarkably, a second group observed no virological differences between Tlr3−/− and WT mice (20). Potential reasons for the disparity in viral infection phenotype may be related to age of mice inoculated and method of virus detection. The first group used 3 week old mice and analyzed viral burden by qRT-PCR (30). The second group did not disclose the age of mice used and determined viral burden by TCID50 analysis (20). An antiviral role for TLR3 is supported by studies with Trif−/− mice, which showed increased foot swelling and viremia after CHIKV inoculation (31).

The RIG-I-like receptors also restrict CHIKV infection and pathogenesis, as a deficiency of MAVS resulted in enhanced viral replication and foot swelling; however, animals deficient in either RIG-I or MDA5 did not show these phenotypes suggesting a redundant role for these two PRRs in sensing of CHIKV RNA (20, 31). Additional studies need to be performed with mice lacking MAVS, RIG-I, and MDA5 to evaluate for effects on the composition and activation state of immune cell infiltrates. While no direct CHIKV infection studies have been reported in Tlr7−/− mice, Myd88−/− mice supported increased viremia and dissemination with relatively minor differences in foot swelling compared to WT mice (20, 31). Because MyD88 is an adaptor molecule downstream of multiple TLRs and other signaling receptors (e.g., IL-1R), direct infection and analysis of immune responses of other TLR deficient mice is required.

PRR signaling promotes nuclear translocation of interferon-regulatory (IRF1, IRF3, IRF5, and IRF7) and NF-κB transcription factors, which induce expression of type I IFNs, IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), and pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (28). In the absence of IRF7, no bioactive type I IFNs were produced in the serum of CHIKV-infected animals (31, 32). There are conflicting reports as to the role of IRF3 in the induction of type I IFNs after CHIKV infection. One group showed no type I IFNs produced in Irf3−/− mice whereas a second reported equivalent levels of type I IFNs compared to WT mice (31, 32). Variations in the results could be related to different CHIKV strains and route of inoculation. However, CHIKV infection of Irf3−/− Irf7−/− double knockout (DKO) mice resulted in a lethal shock syndrome characterized by massive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFNγ, CCL2, IL-6, and TNF-α), thrombocytopenia, and high tissue viral burden (31). The DKO mice also had severe edema, hemorrhaging in the foot, vasculitis, and exudative arthritis that resulted in pronounced swelling (31). In comparison, increased foot swelling was detected in Irf3−/− or Irf7−/− single knockout mice after CHIKV infection, but only the Irf7−/− mice showed increased viremia (31). Consistent with a protective effect of type I IFN signaling, mice lacking the type I IFN receptor (Ifnar1−/− C57BL/6 or 129/Sv animals) or downstream transcription factor STAT1 also succumbed to CHIKV infection, although the time to death was longer in Irf3−/− Irf7−/− DKO compared to Ifnar1−/− mice (20, 32–35). This suggests that additional transcription factors (e.g., IRF1 and IRF5) may contribute to the type I IFN response after CHIKV infection. Bone marrow reconstitution studies in WT, Irf3−/− Irf7−/− DKO, and Ifnar1−/− mice showed that while type I IFNs can be produced by both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells after CHIKV infection, IFN signaling in non-hematopoietic cells controls viral replication (20, 32). This result correlates with the preferential targeting of non-hematopoietic cells, such as fibroblasts, muscle cells, and osteoblasts by CHIKV (20, 21).

A limited set of ISGs have been described as inhibitors of CHIKV infection in vivo. Protein Kinase R (PKR) and OAS3 are ISGs activated during CHIKV replication that lead to translation inhibition, apoptosis, and degradation of single-stranded RNA (27, 36, 37). GADD34 and other proteins are up-regulated following PKR activation and promote type I IFN and IL-6 production. GADD34 deficient cells sustained increased CHIKV infection and minimal IFN-β production, which recapitulates the phenotype observed in Eif2ak1 (gene encoding PKR) deficient cells (36). Gadd34−/− neonatal mice succumbed to CHIKV infection more rapidly with reduced IFN-β production and increased viral burden in tissues (36). Induction of RSAD2, which encodes the protein viperin, was observed in CHIKV-infected CD14+ human monocytes (38). Rsad2−/− fibroblasts supported increased CHIKV replication, and Rsad2−/− mice sustained increased viremia, foot edema and inflammation, which was associated with infiltration of F4/80+ macrophages (38). As the endoplasmic targeting domain of Rsad2 is required to inhibit CHIKV infection in vitro, viperin likely is recruited to the ER where it induces a stress response that activates PKR and blocks CHIKV translation (38). A recent study reported that IFITM3 inhibits CHIKV infection by blocking viral fusion in cells (39). Ifitm3−/− mice sustained increased tissue viral burden, which was mediated in part by greater infection of CD11b+ F4/80lo and CD11blo F4/80hi macrophages (39). Another ISG, Bst2 (gene encoding tetherin), blocks CHIKV from budding from cell and correspondingly, Bst2−/− mice had enhanced viremia with reduced production of type I and II IFNs (40); the antiviral effect of Bst2 occurs even though CHIKV nsp1 suppresses expression of Bst2 mRNA and protein (41). ISG15 modulates CHIKV pathogenesis in neonatal mice. Isg15−/− mice have increased lethality without changes in viral burden (42). In the absence of Isg15, an uncontrolled cytokine response occurs with markedly increased production of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, resulting in a shock syndrome, similar to that observed in Ifnar1−/− neonatal mice (42). These results correlate with findings from human infants infected with CHIKV, who have higher serum cytokine levels (e.g., type I IFNs, IL-1Rα, CXCL10, and IL-12p40/70) than adults (42). Beyond these few studies that have established antiviral functions of individual ISGs against CHIKV in vivo, other ISGs (e.g., IRF1, C6orf150, HSPE, P2RY6, SLC15A3, and SLC25A28) have been suggested to have anti-CHIKV activity based on ectopic expression in cells (43). These ISGs require further study to confirm their inhibitory activity in vivo and determine their mechanism of action.

Human cohort studies have characterized the pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine response during acute CHIKV infection. One group showed increased levels of IL-2R, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IL-15, IFN-α, CXCL9, CXCL10, HGF, FGF-basic, and VEGF and decreased levels of eotaxin, EGF, and IL-8 with CHIKV infection compared to healthy controls (44). Individuals with severe CHIKV disease had increased levels of IL-1β and IL-6 and decreased levels of RANTES compared to non-severe cases (44). A different study correlated increased levels of IL-6, IL-12, IL-15, CXCL10, CCL2, IFN-α, and IL-1Rα with higher viremia (45), and a separate study identified increased levels of CXCL10 and CXCL9 in the serum of patients with mild to severe disease compared to non-symptomatic patients (46). Individuals with persistent arthralgia had increased levels of IL-6 and GM-CSF (45). Collectively, these studies suggest that specific cytokines (e.g. IL-6) may be linked to CHIKV disease severity and pathogenesis.

Innate cellular immune responses

Soon after acute CHIKV infection, monocyte-derived macrophages migrate to the site of viral replication. This occurs in part because the macrophage chemoattractant CCL2 (MCP-1) is induced during CHIKV infection (17, 47), presumably by fibroblasts, monocytes, endothelial, and epithelial cells (48). Infiltrating and tissue resident macrophages produce IL-6, TNF-α, and GM-CSF, and may act as a reservoir for chronic CHIKV RNA and antigen (49–51). As clodronate treatment resulted in reduced foot swelling and increased viremia at late time points, macrophages appear to promote clinical disease while aiding in clearance of infectious virus (17). Consistent with this observation, blockade of macrophage recruitment using the small molecule bindarit, which modulates NF-κB signaling and CCL2 production (52), reduced clinical disease and inflammation in synovial and skeletal muscle tissues (47). However, Ccr2−/− mice showed an opposing phenotype with enhanced foot swelling and inflammation with cartilage erosion (53). In this genetic KO model, the lack of macrophage chemotaxis resulted in compensatory infiltration of neutrophils and eosinophils into the foot at early and late times after infection, respectively, and changes to the cytokine milieu (53).

By the second peak of foot swelling, F4/80+ CD11b+ macrophages increase expression of markers of M2 differentiation including arginase 1 and Ym1, which may aid in tissue repair but also could contribute to incomplete clearance of CHIKV leading to persistence of viral RNA (54). Whereas some macrophage recruitment is required to prevent an unbalanced immunological cellular composition and protect against pathological inflammation, excessive recruitment increases edema and inflammatory cytokines. Inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+ F4/80lo) also traffic to musculoskeletal tissues during infection in mice (17), and could serve as a secondary reservoir. Circulating CHIKV-infected CD14+ monocytes can be detected during acute illness in humans and the percentage of infected monocytes correlates with viremia (55).

Although natural killer (NK) cells accumulate in musculoskeletal tissues shortly after CHIKV infection (16, 17), their protective or pathological function remains uncertain. In one study evaluating NK (CD3− CD56+) and NKT-like (CD3+ CD56+) cells during acute and convalescent CHIKV infection in humans, NK cells were elevated during both phases and NKT-like cells were increased only during the chronic phase. During acute infection, a higher fraction of NK cells produced perforin with a trend toward enhanced cytotoxic activity compared to those from convalescent samples (56). Another study reported that NK cells during the acute stage have increased expression of CD69 and HLA-DR activation markers (57). These cells also had increased expression of NKp44, CD57, ILT2, CD8α, and NKG2C and decreased expression of NKp30, NKp46, NKG2A, and CD161 suggesting that a unique subset of NK cells may be activated after CHIKV infection (57). Another cohort of individuals in the late-acute to early-chronic stage of disease showed an increase in the percentage of NK cells (CD3− CD123− CD14− CD11c− CD19− CD45+ CD38+ CD16+) from isolated PBMCs (58). In mice, a recent study compared the immune responses after infection of strains of the ECSA and Asian genotypes; mice infected with an ECSA virus had increased foot edema and higher number of NK cells compared to animals infected with an Asian virus. Depletion of NK cells reduced foot swelling in animals infected with the ECSA but not Asian strain of CHIKV (59). These results suggest that NK cell-dependent immune mediated pathogenesis may vary among CHIKV genotypes.

Because CHIKV is inoculated into the skin by mosquitoes, γδ T cells have been speculated to have antiviral and/or immunomodulatory roles (60). Indeed, CHIKV infection increases the number of LCA+ CD3+ γδ T cells in the ipsilateral foot and draining lymph node. TCRγδ−/− mice have increased foot swelling during the second peak, myositis with loss of myocytes, enhanced numbers of inflammatory (LCA+ CD11b+ CD11c− Ly6C+) and regulatory (LCA+ CD11b+ CD11c− Ly6C−) monocytes, and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines with no change in viral burden (61). Thus, γδ T cells appear to have protective regulatory role of immune pathology primarily through their ability to modulate inflammatory cell composition in infected tissues.

Adaptive immune response to CHIKV infection

The adaptive immune response to CHIKV infection has a dual role in protection and pathogenesis. While it is absolutely required for the clearance of infectious virus and protection against subsequent infection, it also contributes to the pathology observed during the acute phase (Fig 1). Mice deficient in both B and T cells (Rag1−/− or Rag2−/−) had higher levels of viremia during the acute phase, and infectious virus was sustained in circulation and peripheral tissues for at least three months, which resulted in chronic arthritis and muscle inflammation (18, 25, 62, 63). While the absence of an adaptive immune response results in a failure to clear circulating infectious virus, these mice developed less peak foot swelling with reduced myositis and synovitis, implicating a role for T and/or B cells in the early stages of immune pathogenesis (18, 25).

T cell response

In humans, CHIKV infection results in the activation of CD8+ T cells (as judged by increased expression of CD69 and HLA-DR) with peak levels in peripheral blood detected soon after symptom onset (64). Individuals 7 to 10 weeks post infection still have a high percentage of activated CD38+ HLA-DR+ CD8+ T cells in circulation compared to healthy patients (58). In mice, CD8+ T cells are recruited to affected musculoskeletal tissue within the first week of infection (25). Surprisingly, genetic or acquired deficiencies of CD8+ T cells did not impact foot swelling, joint inflammation, or viremia compared to controls suggesting that CD8+ T cells do not contribute to disease or clearance of infectious virus during the acute phase (25). Many questions remain as to the functions (or lack thereof) of CD8+ T cells during acute and possibly chronic CHIKV infection, especially in regard to viral clearance and persistence. Possible explanations for their apparent lack of antiviral activity include lack of poly-functionality, cellular exhaustion, or viral antagonism of priming.

Large numbers of CD4+ T cells migrate into the joint capsule (synovium) within the first week of CHIKV infection, and these cells produce high levels of IFN-γ (25). Unlike that seen with CD8+ T cells, genetic or acquired deficiencies of CD4+ T cells (25) or MHC II molecules (62) had reduced foot swelling, decreased recruitment of CD8+ T cells without a significant effect on viremia (25). This phenotype is not due to lack of IFN-γ production, since Ifng−/− mice show increased viremia at late time points and a minimally increased foot swelling compared to WT controls after CHIKV infection (25). Depletion of CD4+ T cells with antibodies did not impact the numbers or kinetics of infiltrating CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G− monocytes/macrophages or CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6G+ neutrophils into the foot suggesting that acute clinical disease in the joint and adjacent muscle tissues is due preferentially to CD4+ T cells (25). The role of CD4+ T cells during chronic disease has not yet been elucidated in mice. A study examining synovial biopsies from humans with chronic CHIKV disease showed a high fraction of activated CD69+ CD4+ T cells, suggesting these cells may contribute to chronic disease although the mechanism remains unknown (65).

Although relatively small numbers of regulatory FoxP3+ CD4+ T cells (Treg) migrate to the joint space after CHIKV infection, they appear to modify disease (66). Treg expansion after administration of an IL-2/anti-IL-2 complex reduced foot swelling, tissue edema, and cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression, including IL-6, IFNγ, CXCL10, and IL-10. Higher numbers of Tregs correlated with reduced numbers of IFN-γ+ producing CD4+ T cells in the foot and decreased proliferation of effector CD4+ T cells in the draining lymph node, presumably by down-regulating expression of co-stimulatory molecules on antigen presenting cells (66). Thus, pharmacological strategies to augment Treg expansion could limit the pathological CD4+ T cell response and minimize immune-mediated disease. However, the impact of such interventions on viral persistence and chronic disease warrants further study.

B cell response

Treatment of CHIKV-infected Rag1−/− mice with exogenous neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) eliminates infectious virus from circulation, but as the antibody levels wane infectious virus reemerges, highlighting the importance of antibodies in controlling but not completely clearing infection (18, 62, 63). Indeed, passive transfer of purified monoclonal or polyclonal anti-CHIKV antibodies can protect immunocompromised mice from lethal disease when administered prior to or shortly after infection (24, 67–72).

Many mouse and human anti-CHIKV MAbs neutralize CHIKV in vitro and protect in vivo against acute or chronic musculoskeletal disease in mice and non-human primates (72–75). Neutralizing antibodies target the envelope glycoproteins, which are displayed on the virion surface as trimers of E2/E1 heterodimers (76). Most strongly neutralizing antibodies target the A and B domains on the E2 protein, and antibodies against the B domain of CHIKV broadly inhibit infection against several arthritogenic alphaviruses (74). Neutralizing anti-CHIKV antibodies can inhibit at multiple steps of the virus lifecycle including blockade of virus attachment, entry, pH-dependent fusion in the endosome, new virion assembly, release of the virion from the plasma membrane, and cell-to-cell spread (24, 68,72, 74, 77–79). Apart from this, antibodies may protect against CHIKV infection through their effector functions including antibody mediated cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement activation, and virus opsinization.

In mice, anti-CHIKV IgM can be detected within a few days of infection and begins to wane during the second week (80). This coincides with the development of an IgG response, which increases through the acute phase and remains high during the chronic phase (80). High titers of neutralizing antibody are detected by the end of the second week of infection (80). In µMT mice lacking mature B cells, viremia is increased compared to WT mice and maintained essentially for the life of the animal; the enhanced infection of µMT mice also is associated with increased and prolonged foot swelling compared to WT mice (62, 80). In CHIKV infected humans, virus-specific IgM can be detected for months while isotype switching to IgG occurs within one week of infection (65, 81). One study using cohorts of CHIKV infected patients from acute and chronic phases of disease found that the IgG response was dominated by the IgG3 isotype (82). Individuals with an early IgG3 response paradoxically had higher levels of viremia and more severe acute clinical disease, but developed persistent arthralgia less often (82). The IgG3 neutralizing antibodies reportedly are directed at a single, linear peptide epitope (E2EP3; STKDNFNVYKATRPYLAH) that is located at the N-terminus of the E2 protein (83, 84). CHIKV infected non-human primates generated anti-E2EP3 antibodies, and mice vaccinated with the E2EP3 peptide had reduced viremia and foot swelling upon challenge (83).

Studies in mice have identified factors that modify the protective antibody response and control of CHIKV infection. In MHCII−/− mice, class switching to IgG occurs in the absence of T cell help; while an IgG2c response is generated, the levels are reduced compared to WT mice (62). CHIKV-infected Tlr3−/− mice showed increased IgG titers with reduced neutralization capacity indicating a qualitative defect of antibody function in the absence of signaling by this PRR (30). A recent study identified a mechanism of CHIKV RNA persistence in peripheral tissues through evasion of neutralizing antibody (63). An attenuated, non-persistent strain of CHIKV was neutralized more efficiently than a pathogenic, persistent strain by mouse or human CHIKV immune serum. A single amino acid (residue 82) in the E2 protein of the pathogenic strain affected neutralization by antibodies targeting the B domain and allowed for evasion (63).

Conclusions

Although acute CHIKV infection generates a robust immune response that eliminates circulating infectious virus questions remain regarding the immunobiology of chronic disease. Synovial biopsies from chronically infected humans showed CHIKV-infected perivascular macrophages, large numbers of CD14+ macrophages/monocytes, and activated CD56+ CD69+ NK cells (65). CHIKV-infected rhesus macaques or cynomolgus macaques also show persistence of CHIKV RNA in their spleens, muscle, and joint tissue and CHIKV antigen in CD68+ macrophages of lymphoid organs (49, 85). These results suggest that the chronic phase of disease may be sustained by immune activation from persistent viral RNA and antigen, which results in continuous production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in synovial and muscle tissue. It remains unclear if CHIKV RNA persists because of active viral replication or whether an ineffective immune response fails to eliminate infected cells. Regardless of the mechanism, persistent arthralgia and arthritis occur in a significant fraction of affected individuals. Because chronic CHIKV disease mimics seronegative rheumatoid arthritis (58, 86), drugs approved to treat rheumatoid arthritis have been reported anecdotally as possible treatments for chronic CHIKV arthritis. Retrospective studies in humans have described the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, methotrexate, and corticosteroids to treat chronic CHIKV arthritis with limited success (86, 87). As we generate a more sophisticated understanding of the interplay between immunity and chronic CHIKV disease, the development or repurposing of immune targeted therapies may be a realistic intervention in the near future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonathan Miner for critical review of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R01 AI073755, R01 AI104972, and R01 AI114816). J.M.F. was supported by T32 AI007172.

References

- 1.Robinson MC. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–53. I. Clinical features. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1955;49:28–32. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staples JE, Breiman RF, Powers AM. Chikungunya fever: an epidemiological review of a re-emerging infectious disease. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009;49:942–948. doi: 10.1086/605496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendrick K, Stanek D, Blackmore C C. Centers for Disease, and Prevention. Notes from the field: Transmission of chikungunya virus in the continental United States--Florida, 2014. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2014;63:1137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.PAHO/WHO. Chikungunya: PAHO/WHO Data, Maps and Statistics. 2016 http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_topics&view=rdmore&cid=8379&Itemid=40931, ed. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsetsarkin KA, Vanlandingham DL, McGee CE, Higgs S. A single mutation in chikungunya virus affects vector specificity and epidemic potential. PLoS pathogens. 2007;3:e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powers AM, Brault AC, Tesh RB, Weaver SC. Re-emergence of Chikungunya and O'nyong-nyong viruses: evidence for distinct geographical lineages and distant evolutionary relationships. The Journal of general virology. 2000;81:471–479. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arankalle VA, Shrivastava S, Cherian S, Gunjikar RS, Walimbe AM, Jadhav SM, Sudeep AB, Mishra AC. Genetic divergence of Chikungunya viruses in India (1963–2006) with special reference to the 2005–2006 explosive epidemic. The Journal of general virology. 2007;88:1967–1976. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon F, Javelle E, Oliver M, Leparc-Goffart I, Marimoutou C. Chikungunya virus infection. Current infectious disease reports. 2011;13:218–228. doi: 10.1007/s11908-011-0180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schilte C, Staikowsky F, Couderc T, Madec Y, Carpentier F, Kassab S, Albert ML, Lecuit M, Michault A. Chikungunya virus-associated long-term arthralgia: a 36-month prospective longitudinal study. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013;7:e2137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borgherini G, Poubeau P, Jossaume A, Gouix A, Cotte L, Michault A, Arvin-Berod C, Paganin F. Persistent arthralgia associated with chikungunya virus: a study of 88 adult patients on reunion island. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008;47:469–475. doi: 10.1086/590003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pialoux G, Gauzere BA, Jaureguiberry S, Strobel M. Chikungunya, an epidemic arbovirosis. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2007;7:319–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70107-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy AC, Fleming J, Solomon L. Chikungunya viral arthropathy: a clinical description. J Rheumatol. 1980;7:231–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renault P, Solet JL, Sissoko D, Balleydier E, Larrieu S, Filleul L, Lassalle C, Thiria J, Rachou E, de Valk H, Ilef D, Ledrans M, Quatresous I, Quenel P, Pierre V. A major epidemic of chikungunya virus infection on Reunion Island, France, 2005–2006. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2007;77:727–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kee AC, Yang S, Tambyah P. Atypical chikungunya virus infections in immunocompromised patients. Emerging infectious diseases. 2010;16:1038–1040. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.091115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerardin P, Barau G, Michault A, Bintner M, Randrianaivo H, Choker G, Lenglet Y, Touret Y, Bouveret A, Grivard P, Le Roux K, Blanc S, Schuffenecker I, Couderc T, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Lecuit M, Robillard PY. Multidisciplinary prospective study of mother-to-child chikungunya virus infections on the island of La Reunion. PLoS medicine. 2008;5:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrison TE, Oko L, Montgomery SA, Whitmore AC, Lotstein AR, Gunn BM, Elmore SA, Heise MT. A mouse model of chikungunya virus-induced musculoskeletal inflammatory disease: evidence of arthritis, tenosynovitis, myositis, and persistence. The American journal of pathology. 2011;178:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner J, Anraku I, Le TT, Larcher T, Major L, Roques P, Schroder WA, Higgs S, Suhrbier A. Chikungunya virus arthritis in adult wild-type mice. Journal of virology. 2010;84:8021–8032. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02603-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawman DW, Stoermer KA, Montgomery SA, Pal P, Oko L, Diamond MS, Morrison TE. Chronic joint disease caused by persistent Chikungunya virus infection is controlled by the adaptive immune response. Journal of virology. 2013;87:13878–13888. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02666-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziegler SA, Lu L, da Rosa AP, Xiao SY, Tesh RB. An animal model for studying the pathogenesis of chikungunya virus infection. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2008;79:133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schilte C, Couderc T, Chretien F, Sourisseau M, Gangneux N, Guivel-Benhassine F, Kraxner A, Tschopp J, Higgs S, Michault A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Colonna M, Peduto L, Schwartz O, Lecuit M, Albert ML. Type I IFN controls chikungunya virus via its action on nonhematopoietic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:429–442. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noret M, Herrero L, Rulli N, Rolph M, Smith PN, Li RW, Roques P, Gras G, Mahalingam S. Interleukin 6, RANKL, and osteoprotegerin expression by chikungunya virus-infected human osteoblasts. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;206:455–457. 457–459. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goupil BA, McNulty MA, Martin MJ, McCracken MK, Christofferson RC, Mores CN. Novel Lesions of Bones and Joints Associated with Chikungunya Virus Infection in Two Mouse Models of Disease: New Insights into Disease Pathogenesis. PloS one. 2016;11:e0155243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen W, Foo SS, Taylor A, Lulla A, Merits A, Hueston L, Forwood MR, Walsh NC, Sims NA, Herrero LJ, Mahalingam S. Bindarit, an inhibitor of monocyte chemotactic protein synthesis, protects against bone loss induced by chikungunya virus infection. Journal of virology. 2015;89:581–593. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02034-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pal P, Dowd KA, Brien JD, Edeling MA, Gorlatov S, Johnson S, Lee I, Akahata W, Nabel GJ, Richter MK, Smit JM, Fremont DH, Pierson TC, Heise MT, Diamond MS. Development of a highly protective combination monoclonal antibody therapy against Chikungunya virus. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003312. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teo TH, Lum FM, Claser C, Lulla V, Lulla A, Merits A, Renia L, Ng LF. A pathogenic role for CD4+ T cells during Chikungunya virus infection in mice. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:259–269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Duijl-Richter MK, Hoornweg TE, Rodenhuis-Zybert IA, Smit JM. Early Events in Chikungunya Virus Infection-From Virus Cell Binding to Membrane Fusion. Viruses. 2015;7:3647–3674. doi: 10.3390/v7072792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White LK, Sali T, Alvarado D, Gatti E, Pierre P, Streblow D, Defilippis VR. Chikungunya virus induces IPS-1-dependent innate immune activation and protein kinase R-independent translational shutoff. Journal of virology. 2011;85:606–620. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00767-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D, Taniguchi T. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annual review of immunology. 2008;26:535–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez David RY, Combredet C, Sismeiro O, Dillies MA, Jagla B, Coppee JY, Mura M, Guerbois Galla M, Despres P, Tangy F, Komarova AV. Comparative analysis of viral RNA signatures on different RIG-I-like receptors. eLife. 2016;5:e11275. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Her Z, Teng TS, Tan JJ, Teo TH, Kam YW, Lum FM, Lee WW, Gabriel C, Melchiotti R, Andiappan AK, Lulla V, Lulla A, Win MK, Chow A, Biswas SK, Leo YS, Lecuit M, Merits A, Renia L, Ng LF. Loss of TLR3 aggravates CHIKV replication and pathology due to an altered virus-specific neutralizing antibody response. EMBO molecular medicine. 2015;7:24–41. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudd PA, Wilson J, Gardner J, Larcher T, Babarit C, Le TT, Anraku I, Kumagai Y, Loo YM, Gale M, Jr, Akira S, Khromykh AA, Suhrbier A. Interferon response factors 3 and 7 protect against Chikungunya virus hemorrhagic fever and shock. Journal of virology. 2012;86:9888–9898. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00956-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schilte C, Buckwalter MR, Laird ME, Diamond MS, Schwartz O, Albert ML. Cutting edge: independent roles for IRF-3 and IRF-7 in hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells during host response to Chikungunya infection. Journal of immunology. 2012;188:2967–2971. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Partidos CD, Weger J, Brewoo J, Seymour R, Borland EM, Ledermann JP, Powers AM, Weaver SC, Stinchcomb DT, Osorio JE. Probing the attenuation and protective efficacy of a candidate chikungunya virus vaccine in mice with compromised interferon (IFN) signaling. Vaccine. 2011;29:3067–3073. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Couderc T, Chretien F, Schilte C, Disson O, Brigitte M, Guivel-Benhassine F, Touret Y, Barau G, Cayet N, Schuffenecker I, Despres P, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Michault A, Albert ML, Lecuit M. A mouse model for Chikungunya: young age and inefficient type-I interferon signaling are risk factors for severe disease. PLoS pathogens. 2008;4:e29. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner CL, Burke CW, Higgs ST, Klimstra WB, Ryman KD. Interferon-alpha/beta deficiency greatly exacerbates arthritogenic disease in mice infected with wild-type chikungunya virus but not with the cell culture-adapted live-attenuated 181/25 vaccine candidate. Virology. 2012;425:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clavarino G, Claudio N, Couderc T, Dalet A, Judith D, Camosseto V, Schmidt EK, Wenger T, Lecuit M, Gatti E, Pierre P. Induction of GADD34 is necessary for dsRNA-dependent interferon-beta production and participates in the control of Chikungunya virus infection. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8:e1002708. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brehin AC, Casademont I, Frenkiel MP, Julier C, Sakuntabhai A, Despres P. The large form of human 2',5'-Oligoadenylate Synthetase (OAS3) exerts antiviral effect against Chikungunya virus. Virology. 2009;384:216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teng TS, Foo SS, Simamarta D, Lum FM, Teo TH, Lulla A, Yeo NK, Koh EG, Chow A, Leo YS, Merits A, Chin KC, Ng LF. Viperin restricts chikungunya virus replication and pathology. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:4447–4460. doi: 10.1172/JCI63120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poddar S, Hyde JL, Gorman MJ, Farzan M, Diamond MS. The interferon-stimulated gene IFITM3 restricts infection and pathogenesis of arthritogenic and encephalitic alphaviruses. Journal of virology. 2016 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00655-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahauad-Fernandez WD, Jones PH, Okeoma CM. Critical role for bone marrow stromal antigen 2 in acute Chikungunya virus infection. The Journal of general virology. 2014;95:2450–2461. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.068643-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones PH, Maric M, Madison MN, Maury W, Roller RJ, Okeoma CM. BST-2/tetherin-mediated restriction of chikungunya (CHIKV) VLP budding is counteracted by CHIKV non-structural protein 1 (nsP1) Virology. 2013;438:37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Werneke SW, Schilte C, Rohatgi A, Monte KJ, Michault A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Vanlandingham DL, Higgs S, Fontanet A, Albert ML, Lenschow DJ. ISG15 is critical in the control of Chikungunya virus infection independent of UbE1L mediated conjugation. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1002322. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoggins JW, Wilson SJ, Panis M, Murphy MY, Jones CT, Bieniasz P, Rice CM. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011;472:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng LF, Chow A, Sun YJ, Kwek DJ, Lim PL, Dimatatac F, Ng LC, Ooi EE, Choo KH, Her Z, Kourilsky P, Leo YS. IL-1beta, IL-6, and RANTES as biomarkers of Chikungunya severity. PloS one. 2009;4:e4261. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chow A, Her Z, Ong EK, Chen JM, Dimatatac F, Kwek DJ, Barkham T, Yang H, Renia L, Leo YS, Ng LF. Persistent arthralgia induced by Chikungunya virus infection is associated with interleukin-6 and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;203:149–157. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelvin AA, Banner D, Silvi G, Moro ML, Spataro N, Gaibani P, Cavrini F, Pierro A, Rossini G, Cameron MJ, Bermejo-Martin JF, Paquette SG, Xu L, Danesh A, Farooqui A, Borghetto I, Kelvin DJ, Sambri V, Rubino S. Inflammatory cytokine expression is associated with chikungunya virus resolution and symptom severity. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2011;5:e1279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rulli NE, Rolph MS, Srikiatkhachorn A, Anantapreecha S, Guglielmotti A, Mahalingam S. Protection from arthritis and myositis in a mouse model of acute chikungunya virus disease by bindarit, an inhibitor of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 synthesis. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;204:1026–1030. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. Journal of interferon & cytokine research : the official journal of the International Society for Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2009;29:313–326. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Labadie K, Larcher T, Joubert C, Mannioui A, Delache B, Brochard P, Guigand L, Dubreil L, Lebon P, Verrier B, de Lamballerie X, Suhrbier A, Cherel Y, Le Grand R, Roques P. Chikungunya disease in nonhuman primates involves long-term viral persistence in macrophages. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:894–906. doi: 10.1172/JCI40104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sourisseau M, Schilte C, Casartelli N, Trouillet C, Guivel-Benhassine F, Rudnicka D, Sol-Foulon N, Le Roux K, Prevost MC, Fsihi H, Frenkiel MP, Blanchet F, Afonso PV, Ceccaldi PE, Ozden S, Gessain A, Schuffenecker I, Verhasselt B, Zamborlini A, Saib A, Rey FA, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Despres P, Michault A, Albert ML, Schwartz O. Characterization of reemerging chikungunya virus. PLoS pathogens. 2007;3:e89. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumar S, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Giry C, Connen de Kerillis L, Merits A, Gasque P, Hoarau JJ. Mouse macrophage innate immune response to Chikungunya virus infection. Virology journal. 2012;9:313. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mora E, Guglielmotti A, Biondi G, Sassone-Corsi P. Bindarit: an anti-inflammatory small molecule that modulates the NFkappaB pathway. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:159–169. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.1.18559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poo YS, Nakaya H, Gardner J, Larcher T, Schroder WA, Le TT, Major LD, Suhrbier A. CCR2 deficiency promotes exacerbated chronic erosive neutrophil-dominated chikungunya virus arthritis. Journal of virology. 2014;88:6862–6872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03364-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stoermer KA, Burrack A, Oko L, Montgomery SA, Borst LB, Gill RG, Morrison TE. Genetic ablation of arginase 1 in macrophages and neutrophils enhances clearance of an arthritogenic alphavirus. Journal of immunology. 2012;189:4047–4059. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Her Z, Malleret B, Chan M, Ong EK, Wong SC, Kwek DJ, Tolou H, Lin RT, Tambyah PA, Renia L, Ng LF. Active infection of human blood monocytes by Chikungunya virus triggers an innate immune response. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:5903–5913. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thanapati S, Das R, Tripathy AS. Phenotypic and functional analyses of NK and NKT-like populations during the early stages of chikungunya infection. Frontiers in microbiology. 2015;6:895. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petitdemange C, Becquart P, Wauquier N, Beziat V, Debre P, Leroy EM, Vieillard V. Unconventional repertoire profile is imprinted during acute chikungunya infection for natural killer cells polarization toward cytotoxicity. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1002268. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miner JJ, Aw Yeang HX, Fox JM, Taffner S, Malkova ON, Oh ST, Kim AH, Diamond MS, Lenschow DJ, Yokoyama WM. Chikungunya viral arthritis in the United States: a mimic of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & rheumatology. 2015;67:1214–1220. doi: 10.1002/art.39027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teo TH, Her Z, Tan JJ, Lum FM, Lee WW, Chan YH, Ong RY, Kam YW, Leparc-Goffart I, Gallian P, Renia L, de Lamballerie X, Ng LF. Caribbean and La Reunion Chikungunya Virus Isolates Differ in Their Capacity To Induce Proinflammatory Th1 and NK Cell Responses and Acute Joint Pathology. Journal of virology. 2015;89:7955–7969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00909-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vantourout P, Hayday A. Six-of-the-best: unique contributions of gammadelta T cells to immunology. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2013;13:88–100. doi: 10.1038/nri3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Long KM, Ferris MT, Whitmore AC, Montgomery SA, Thurlow LR, McGee CE, Rodriguez CA, Lim JK, Heise MT. gammadelta T Cells Play a Protective Role in Chikungunya Virus-Induced Disease. Journal of virology. 2016;90:433–443. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02159-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Poo YS, Rudd PA, Gardner J, Wilson JA, Larcher T, Colle MA, Le TT, Nakaya HI, Warrilow D, Allcock R, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Schroder WA, Khromykh AA, Lopez JA, Suhrbier A. Multiple immune factors are involved in controlling acute and chronic chikungunya virus infection. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2014;8:e3354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hawman DW, Fox JM, Ashbrook AW, May NA, Schroeder KM, Torres RM, Crowe JE, Jr, Dermody TS, Diamond MS, Morrison TE. Pathogenic Chikungunya Virus Evades B Cell Responses to Establish Persistence. Cell reports. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.06.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wauquier N, Becquart P, Nkoghe D, Padilla C, Ndjoyi-Mbiguino A, Leroy EM. The acute phase of Chikungunya virus infection in humans is associated with strong innate immunity and T CD8 cell activation. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2011;204:115–123. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hoarau JJ, Jaffar Bandjee MC, Krejbich Trotot P, Das T, Li-Pat-Yuen G, Dassa B, Denizot M, Guichard E, Ribera A, Henni T, Tallet F, Moiton MP, Gauzere BA, Bruniquet S, Jaffar Bandjee Z, Morbidelli P, Martigny G, Jolivet M, Gay F, Grandadam M, Tolou H, Vieillard V, Debre P, Autran B, Gasque P. Persistent chronic inflammation and infection by Chikungunya arthritogenic alphavirus in spite of a robust host immune response. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:5914–5927. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee WW, Teo TH, Her Z, Lum FM, Kam YW, Haase D, Renia L, Rotzschke O, Ng LF. Expanding regulatory T cells alleviates chikungunya virus-induced pathology in mice. Journal of virology. 2015 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00998-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Couderc T, Khandoudi N, Grandadam M, Visse C, Gangneux N, Bagot S, Prost JF, Lecuit M. Prophylaxis and therapy for Chikungunya virus infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2009;200:516–523. doi: 10.1086/600381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith Scott A, Silva Laurie A, Fox Julie M, Flyak AI, Kose N, Sapparapu G, Khomadiak S, Ashbrook Alison W, Kahle Kristen M, Fong Rachel H, Swayne S, Doranz Benjamin J, McGee Charles E, Heise Mark T, Pal P, Brien James D, Austin SK, Diamond Michael S, Dermody Terence S, Crowe James E., Jr Isolation and Characterization of Broad and Ultrapotent Human Monoclonal Antibodies with Therapeutic Activity against Chikungunya Virus. Cell host & microbe. 2015;18:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fric J, Bertin-Maghit S, Wang CI, Nardin A, Warter L. Use of human monoclonal antibodies to treat Chikungunya virus infection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2013;207:319–322. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fong RH, Banik SS, Mattia K, Barnes T, Tucker D, Liss N, Lu K, Selvarajah S, Srinivasan S, Mabila M, Miller A, Muench MO, Michault A, Rucker JB, Paes C, Simmons G, Kahle KM, Doranz BJ. Exposure of epitope residues on the outer face of the chikungunya virus envelope trimer determines antibody neutralizing efficacy. Journal of virology. 2014;88:14364–14379. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01943-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Selvarajah S, Sexton NR, Kahle KM, Fong RH, Mattia KA, Gardner J, Lu K, Liss NM, Salvador B, Tucker DF, Barnes T, Mabila M, Zhou X, Rossini G, Rucker JB, Sanders DA, Suhrbier A, Sambri V, Michault A, Muench MO, Doranz BJ, Simmons G. A neutralizing monoclonal antibody targeting the acid-sensitive region in chikungunya virus E2 protects from disease. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013;7:e2423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jin J, Liss NM, Chen DH, Liao M, Fox JM, Shimak RM, Fong RH, Chafets D, Bakkour S, Keating S, Fomin ME, Muench MO, Sherman MB, Doranz BJ, Diamond MS, Simmons G. Neutralizing Monoclonal Antibodies Block Chikungunya Virus Entry and Release by Targeting an Epitope Critical to Viral Pathogenesis. Cell reports. 2015;13:2553–2564. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goh LY, Hobson-Peters J, Prow NA, Gardner J, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Pyke AT, Suhrbier A, Hall RA. Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to the E2 protein of chikungunya virus protects against disease in a mouse model. Clinical immunology. 2013;149:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fox JM, Long F, Edeling MA, Lin H, van Duijl-Richter MK, Fong RH, Kahle KM, Smit JM, Jin J, Simmons G, Doranz BJ, Crowe JE, Jr, Fremont DH, Rossmann MG, Diamond MS. Broadly Neutralizing Alphavirus Antibodies Bind an Epitope on E2 and Inhibit Entry and Egress. Cell. 2015;163:1095–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pal P, Fox JM, Hawman DW, Huang YJ, Messaoudi I, Kreklywich C, Denton M, Legasse AW, Smith PP, Johnson S, Axthelm MK, Vanlandingham DL, Streblow DN, Higgs S, Morrison TE, Diamond MS. Chikungunya viruses that escape monoclonal antibody therapy are clinically attenuated, stable, and not purified in mosquitoes. Journal of virology. 2014;88:8213–8226. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01032-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cheng RH, Kuhn RJ, Olson NH, Rossmann MG, Choi HK, Smith TJ, Baker TS. Nucleocapsid and glycoprotein organization in an enveloped virus. Cell. 1995;80:621–630. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90516-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee CY, Kam YW, Fric J, Malleret B, Koh EG, Prakash C, Huang W, Lee WW, Lin C, Lin RT, Renia L, Wang CI, Ng LF, Warter L. Chikungunya virus neutralization antigens and direct cell-to-cell transmission are revealed by human antibody-escape mutants. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1002390. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Porta J, Mangala Prasad V, Wang CI, Akahata W, Ng LF, Rossmann MG. Structural Studies of Chikungunya Virus-Like Particles Complexed with Human Antibodies: Neutralization and Cell-to-Cell Transmission. Journal of virology. 2016;90:1169–1177. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02364-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Masrinoul P, Puiprom O, Tanaka A, Kuwahara M, Chaichana P, Ikuta K, Ramasoota P, Okabayashi T. Monoclonal antibody targeting chikungunya virus envelope 1 protein inhibits virus release. Virology. 2014;464–465:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lum FM, Teo TH, Lee WW, Kam YW, Renia L, Ng LF. An essential role of antibodies in the control of Chikungunya virus infection. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:6295–6302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grivard P, Le Roux K, Laurent P, Fianu A, Perrau J, Gigan J, Hoarau G, Grondin N, Staikowsky F, Favier F, Michault A. Molecular and serological diagnosis of Chikungunya virus infection. Pathologie-biologie. 2007;55:490–494. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kam YW, Simarmata D, Chow A, Her Z, Teng TS, Ong EK, Renia L, Leo YS, Ng LF. Early appearance of neutralizing immunoglobulin G3 antibodies is associated with chikungunya virus clearance and long-term clinical protection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;205:1147–1154. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kam YW, Lum FM, Teo TH, Lee WW, Simarmata D, Harjanto S, Chua CL, Chan YF, Wee JK, Chow A, Lin RT, Leo YS, Le Grand R, Sam IC, Tong JC, Roques P, Wiesmuller KH, Renia L, Rotzschke O, Ng LF. Early neutralizing IgG response to Chikungunya virus in infected patients targets a dominant linear epitope on the E2 glycoprotein. EMBO molecular medicine. 2012;4:330–343. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201200213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kam YW, Pok KY, Eng KE, Tan LK, Kaur S, Lee WW, Leo YS, Ng LC, Ng LF. Sero-prevalence and cross-reactivity of chikungunya virus specific anti-E2EP3 antibodies in arbovirus-infected patients. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2015;9:e3445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Messaoudi I, Vomaske J, Totonchy T, Kreklywich CN, Haberthur K, Springgay L, Brien JD, Diamond MS, Defilippis VR, Streblow DN. Chikungunya virus infection results in higher and persistent viral replication in aged rhesus macaques due to defects in anti-viral immunity. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2013;7:e2343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Javelle E, Ribera A, Degasne I, Gauzere BA, Marimoutou C, Simon F. Specific management of post-chikungunya rheumatic disorders: a retrospective study of 159 cases in Reunion Island from 2006–2012. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2015;9:e0003603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ganu MA, Ganu AS. Post-chikungunya chronic arthritis--our experience with DMARDs over two year follow up. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]