Abstract

Background:

Plantar fasciitis (PF) is a common foot complaint, affects both active sportsmen and physically inactive middle age group. It is believed that PF results from degenerative changes rather than inflammation. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy has been introduced as an alternative therapy for PF. This study is aimed to systematically review to the effectiveness and relevant factors of PRP treatment in managing PF.

Materials and Methods:

A search was conducted in electronic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar using different keywords. Publications in English-language from 2010 to 2015 were included. Two reviewers extracted data from selected articles after the quality assessment was done.

Results:

A total of 1126 articles were retrieved, but only 12 articles met inclusion and exclusion criteria. With a total of 455 patients, a number of potentially influencing factors on the effectiveness of PRP for PF was identified. In all these studies, PRP had been injected directly into the plantar fascia, with or without ultrasound guidance. Steps from preparation to injection were found equally crucial. Amount of collected blood, types of blood anti-coagulant, methods in preparing PRP, speed, and numbers of time the blood samples were centrifuged, activating agent added to the PRP and techniques of injection, were varied between different studies. Regardless of these variations, superiority of PRP treatment compared to steroid was reported in all studies.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, PRP therapy might provide an effective alternative to conservative management of PF with no obvious side effect or complication. The onset of action after PRP injection also greatly depended on the degree of degeneration.

Keywords: Plantar fasciitis, platelet-rich plasma, treatment

INTRODUCTION

Plantar fascia is a connective tissue on the bottom of the foot which connects heel bone to toes. It functions to maintain the medial arch of the foot and help in absorbing shocks, in addition, to keep tract with the windlass mechanism during walking.[1,2] Heel pain is commonly due to a condition known as plantar fasciitis (PF) which involves plantar fascia. PF affects not only sport participants, but also those middle-aged individuals who are physically inactive, however, age, obesity, excessive weight bearing, and tight Achilles tendon are the common predisposing factors.[3,4] The peak incidence occurs between 40 and 60-year-old in both gender.[5] Diagnosis of PF is usually made based on history and clinical finding. Generally, patients with PF tend to have worsening of pain when they first step on the floor in the early morning. However, the pain gradually improves with subsequent physical activity. The pain deteriorates when one dorsiflex the toes, as this action pulls the plantar fascia together.[6,7,8] It was previously assumed that PF occurs as a result of inflammation. Until recent decade, it is accepted that the underlying pathology is actually a degenerative process.[9,10,11] This degenerative condition takes place near the origin of the plantar fascia at the medial tuberosity of the calcaneus.[11,12]

The main-stay of treatments is conservative therapies, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physiotherapy which include the plantar fascia stretching exercises, activities modification, use of shoe insoles, corticosteroids injection, and[11] extracorporeal shock wave therapy.[13,14,15,16] One of the known effective, but short-term treatment modality is a direct injection of steroid into the plantar fascia.[17,18,19,20,21,22]

New treatment regimens that stimulate a healing response instead of suppressing the inflammatory process should be regarded as a more effective treatment options. This has prompted to the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) which is well-known to induce cell growth and subsequently tissue healing. The rationale for using PRP is to increase tendon regenerative abilities with a high content of cytokines and cells, in hyperphysiologic doses, which should promote cellular chemotaxis, matrix synthesis, and proliferation. Centrifugation functions to mechanically concentrate the level of platelets to levels 7–25 times more than the baseline of whole blood. These have prompt the use of PRP as a vector to deliver growth factors to local muscle and tendon injury and repair zones to induce and accelerate healing.[23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]

The objective of this study is to systematically review available evidence from published articles to assess the effectiveness and relevant factors of PRP treatment in managing PF. The assessment also would encompass safety, side effect, and complications of this mode of treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection of literature

The searches were performed in the PubMed (2000–2015), Google Scholar (2000–2015), and Scopus (2000–2015) using a series of keywords, terms, and subject headings made from Pub-Med's medical subject headings (MeSH). The search of MeSH included: PF, plantar fasciopathy, heel pain, PRP, and PRP.

Inclusion criteria

Selected articles were limited to human studies, publications in English-language and all kind of studies, including clinical trial, case series, and case report. This study did not proceed with meta-analysis thus no specific statistical test was done. Inclusion criteria for target population comprised subjects that were diagnosed to have suffered from PF and received PRP treatment. Studies should have clear details of clinical assessments which might be any of the following methods, i.e., evaluation of pain using visual analog scale (VAS), evaluation of function using Roles–Maudsley (RM) scores, evaluation with American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) scale and ultrasonography evaluation.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if the patients in the study received local steroid injection within 6 months, have previous surgery of the foot, previous fracture to calcaneus or having other associated diseases of lower limb (vascular insufficiency, Diabetic, neuropathy, and ankle joint disorder). Furthermore, studies with insufficient follow-up during the study were excluded.

Data extraction

Titles and abstracts of all the studies were reviewed by two reviewers to identify relevant studies. Any disagreement for inclusion or exclusion if an article was fixed by discussion with the third reviewer. Two reviewers extracted the data from eligible studies independently. These data were included author, year of publication, study design, sample size, and details of intervention in study and control group, finding of studies, mean age of patients, assessment method, duration of follow-up, any reported complication, duration of symptoms in patient at the beginning of the study, amount of blood collected for PRP, method of PRP preparation, details of PRP injection, method of confirmation/diagnosis for PF before recruiting participants and usage of ultrasound guidance for injection.

Quality assessment

JADAD score was used for the quality assessment of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used for nonrandomized studies. Studies achieving, at least, JADAD score of three or NOS of seven were considered to bequalify (good) to be included in this systematic review.

RESULTS

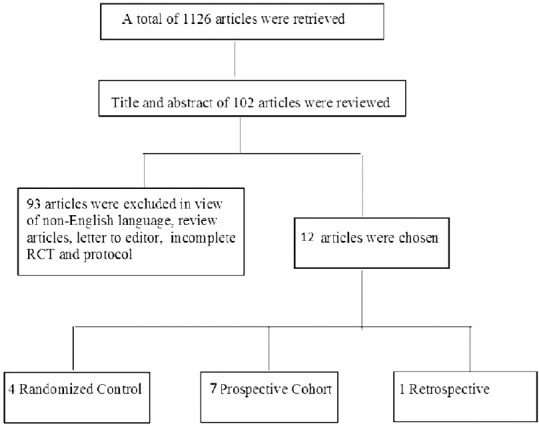

A total of 1126 articles were retrieved using different keywords (Google Scholar: 1012, PubMed: 21, Scopus: 93). By reviewing the titles and abstracts, only 102 articles were eligible to be reviewed based on their relevance to the aim of this systematic review. Finally, 12 articles were met all inclusion and exclusion criteria to be reviewed in this study.[32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] These were four RCTs, seven prospective cohort and one retrospective cohort studies. The rest of articles were excluded in view of non-English language, letter to editor, review articles, incomplete RCT, and protocol [Figure 1]. Tables 1–3 show details of the selected articles.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection

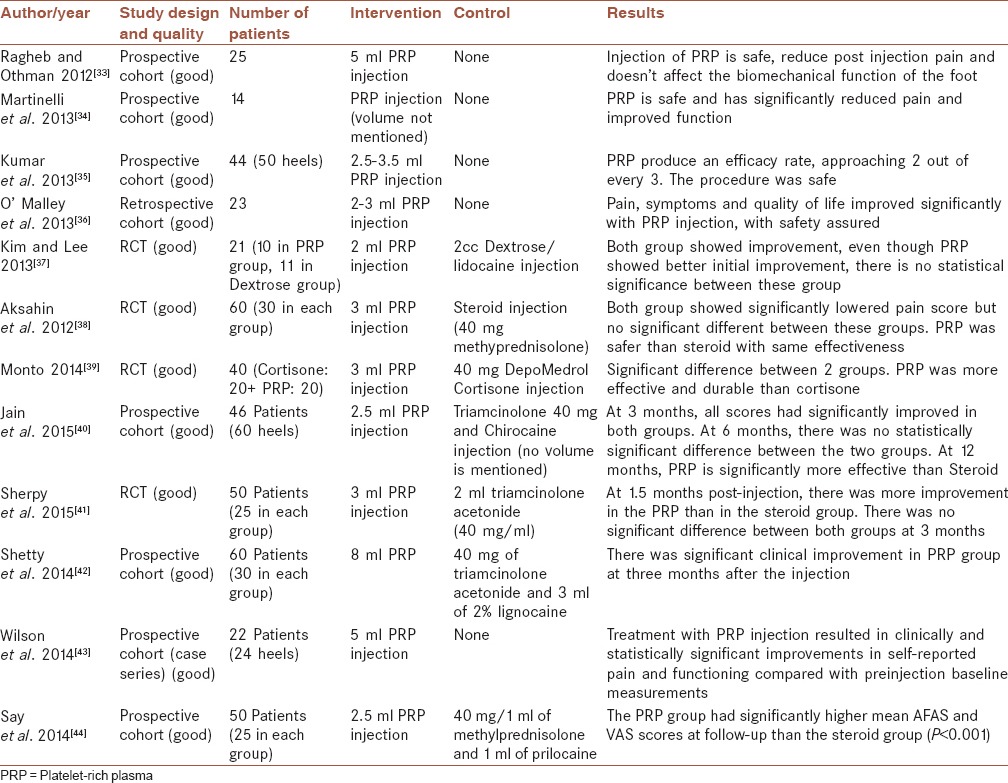

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of twelve studies on effectiveness of PRP

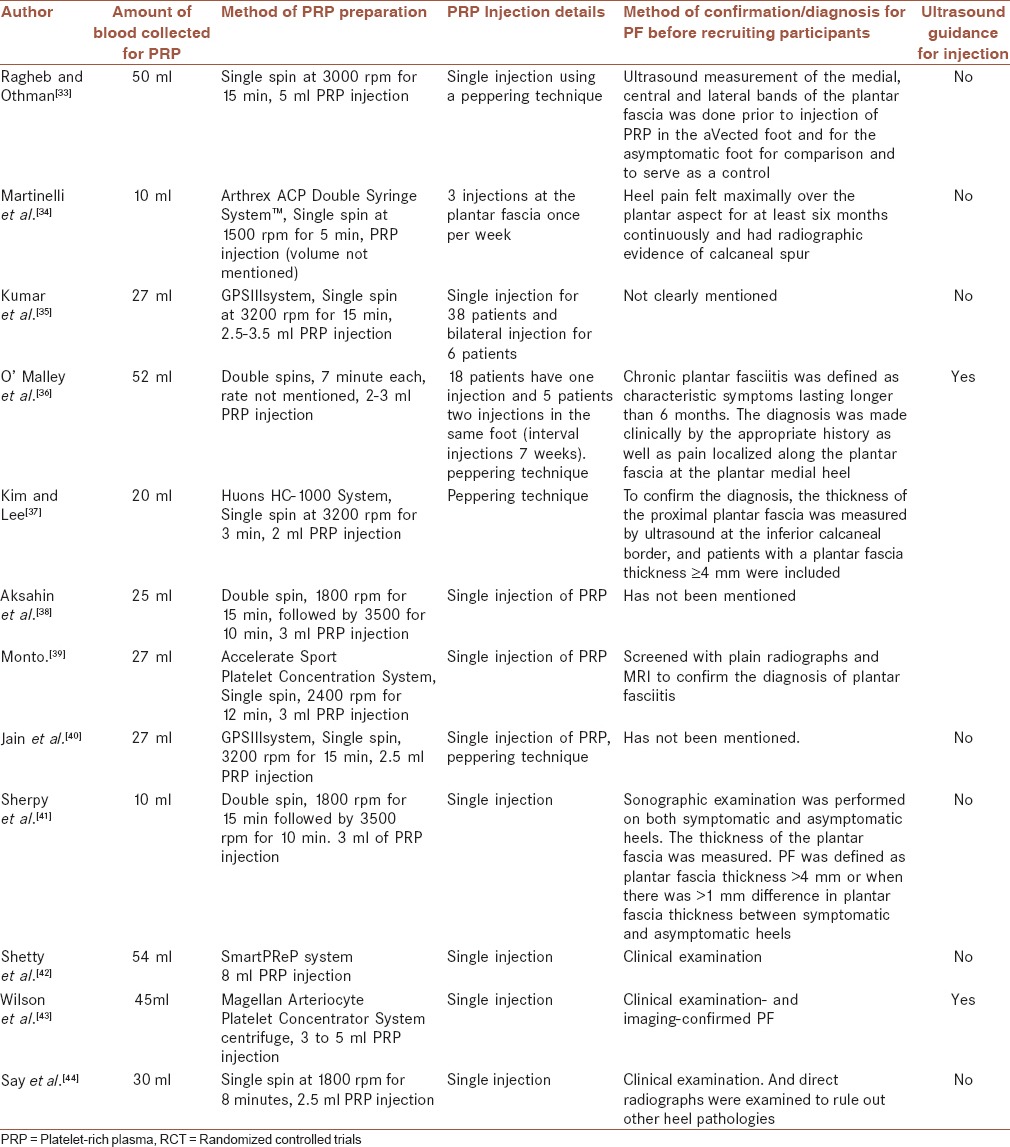

Table 3.

Details of PRP preparation and injection

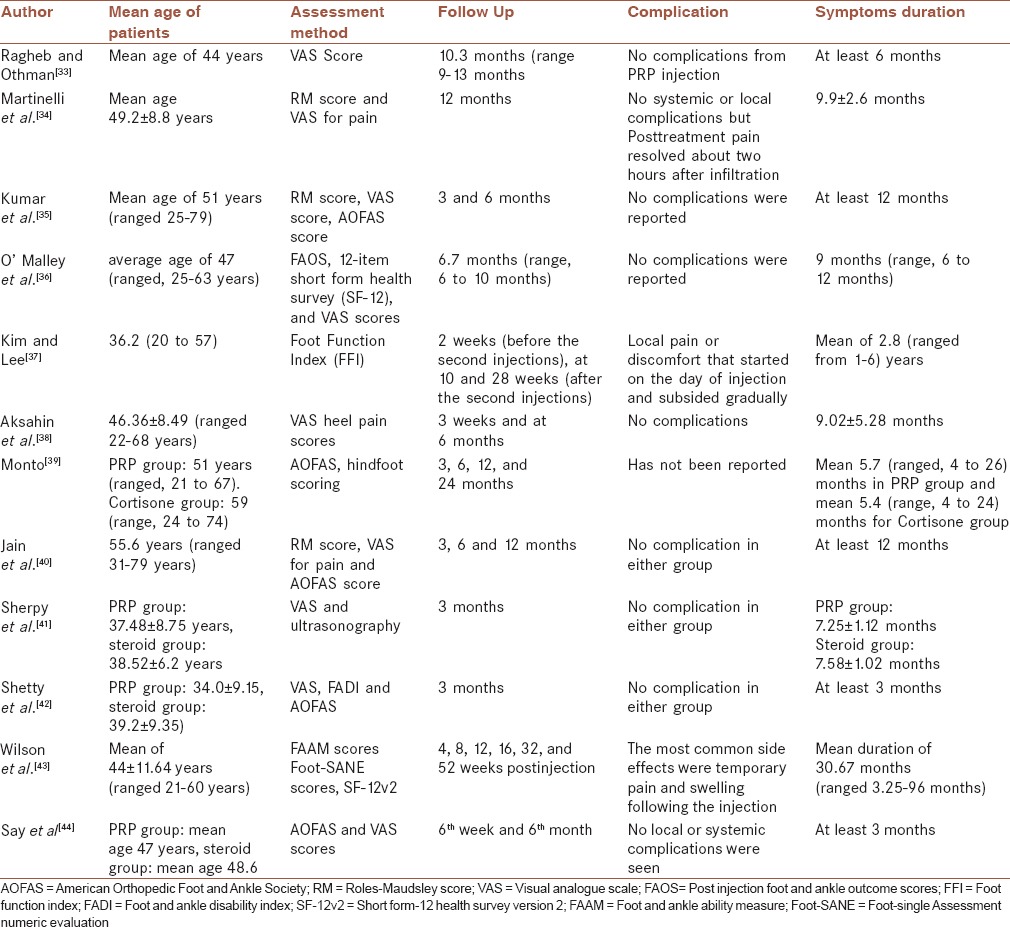

Table 2.

Characterizations of patients and study design

Descriptive characteristics of twelve studies

Both male and female patients were recruited in these 12 studies. Sample size of the twelve studies ranged from 14 to 60 with a total of 455 patients. The majority of patients have unilateral PF. However, a total of 22 patients from three studies have had bilateral PF. The duration of symptoms (PF) in patients at the beginning of interventions was from 3 to 24 months. Different assessments, including AOFAS, RM scores, visual analog scores (VAS), postinjection foot and ankle outcome scores, foot function index, and 12-item short form health survey (SF-12) were used to measure the outcome of treatments. Only three out of nine studies have used ultrasound guidance for injection of PRP. Seven studies have had a single injection of PRP while the other two studies have done more than one-time injection.

Blood collected for PRP preparation was ranged from 10 ml to 52 ml. Three studies used double spin centrifugation for PRP preparation and the rest of studies used single spin. Eight out of 12 studies used different commercial systems for the PRP preparation and the other four studies have used normal centrifuge. The injected volume of PRP was between 2 ml and 5 ml. Follow-up for monitoring the improvement or any complications of PRP or steroid was done from 2 weeks up to 24 months.

DISCUSSION

PRP has shown promise in the treatment of various musculoskeletal conditions including chronic lateral epicondylitis, osteoarthritis, muscle strain, ligament sprain, cartilage damage, fractures, and tendon injury and has been approved by the International Olympic Committee in the treatment of soft tissue injuries and tendon disorders.[26,27,44,45,46,47] Furthermore, PRP might be considered as an alternative treatment for plantar fascia. The steps from preparation to injection are equally crucial when we are assessing the effectiveness of PRP in the treatment of PF. In all the selected studies, PRP injection has been done directly into the plantar fascia. However four of these studies have used ultrasound guidance during injection.[35,36,38,42] It is arguable that ultrasound guidance may promise a more accurate placement of PRP and injection without ultrasound guidance may be considered as a shortcoming of a study. Nevertheless, no advantage of ultrasound guidance over direct palpation guidance was reported by Kane et al.[1] during steroid injection for PF.

The technique of injection may also indirectly affect the outcome of this study, for example, peppering or direct single injection. In peppering technique, the needle was placed into the target tissue and withdrawn slowly while maintaining the tip of the needle within the tissue. The needle was then angulated and reinserted to make another puncture onto the fascia at different sites. Peppering on the plantar fascia could possibly stimulate the release of endogenous growth factors that help in regeneration. Kalaci et al.[18] reported a superior effect in his study when peppering technique was used as compared to single direct injection.

Another potentially influencing factor in this assessment was the amount of collected blood and different methods are used in preparing PRP. After venous blood was drawn from the patients, centrifugation was done to separate the PRP and platelet-poor plasma. These studies reported various method and speed of centrifugation, and the number of time the blood samples were centrifuged (some single – spin, while others were double – spinning). Furthermore, the different types of anti-coagulant or activating agent added to the PRP may also affect the outcome of the effectiveness of PRP in treating PF.[17,48]

The main purpose of blood centrifugation is to concentrate the growth factors within the platelet. Some investigators believe that the action of growth factors is dose-dependent.[24] This means that only at certain concentration can it generate new cells growth. No data had been published to date to indicate the quantity of growth factors required to stimulate the healing process. However, there were studies which showed clinical efficacy could be expected when there is minimal 4- to 6-fold increase in platelet concentration from the whole blood baseline.[49,50] Thus, platelet concentration appears as an important factor in ensuring cell regeneration. Despite having achieved the desired concentration, the amount or volume of PRP may also play an important role in determining the effectiveness. Kumar et al.[34] found that three of his patients who had bilateral plantar fasciitis injections at the same setting failed to improve. The explanation for this can be attributed to the small amount of PRP that was injected into each heel (only 1.5 ml to each heel). During the subsequent injections to these three patients, improvement was noted after injection of 3 ml of PRP into each heel. This strongly suggested that tissue regeneration may take place only with adequate volume of PRP.

Diagnosis of PF is commonly made base on clinical examination and observations. It is, therefore, crucial to have a precise and accurate diagnosis. A wrong diagnosis could possibly be an important factor affecting the outcome of the effectiveness of PRP in the management of PF. This is because diseases respond differently according to their underlying pathophysiology. As in the prospective study done by Kumar et al.,[34] one patient with tarsal tunnel syndrome only showed improvement after surgical decompression. Therefore in resistant cases, it is important to exclude other conditions which sign and symptoms might resemble PF, such as tarsal tunnel syndrome and stress fractures. Further investigations may be necessary for us to arrive at correct diagnosis, such as magnetic resonance imaging scan or nerve conduction study.

The efficacy of PRP treatment should also take into account the onset of effect and the duration for the patient to remain symptoms free. Most patients would prefer something that offer instant pain relief with no recurrence of symptoms. In most of the studies, the improvement was observed during the first 3 months after injection. Significant improvement was also noted when the patient was followed up till 12 months postinjection. The onset of action after PRP injection also greatly depends on the degree of degeneration as the organ or tissue is in demand for longer recovery time for a complete regeneration. The coupled home therapy after the injection may affect the outcome of the effectiveness of PRP. Those patients who reported relief of pain and other improvement, believed on direct effect of PRP injection, although all patients were also recommended to remain under conventional treatment, including gel heel cups and stretching exercises.

Steroid injection has been a popular mode of treatment when conservative management failed. However, corticosteroid injection is effective only in the short-term and only to a limited degree.[51,52,53] There is also close association with a higher rate of relapse and recurrence. Moreover direct pain relief after injection results in a tendency to overuse the affected foot.[21,54] Besides, it also carries the risk of tendon rupture as mentioned earlier. There were few studies that compare the results of steroid and PRP injections in other chronic tendon disorder apart from PF.[55,56,57] Peerbooms et al.[56] found a positive effect of PRP injection for lateral epicondylitis. This was the first comparison of PRP with corticosteroid injection in patient with lateral epicondylitis. The results indicated that a single injection of PRP decreased pain and improves function better than a corticosteroid injection.

As direct injection onto a degenerative area of the plantar fascia, should not arise any adverse side effect or complication then theoretically PRP injection also should not have any side effect. As expected, none of the above studies reported any complication from PRP injection. In fact to date, study of PRP injection for musculoskeletal conditions has not revealed any serious adverse[58,59] events. PRP should thus be deemed as a safe procedure in treating PF.

CONCLUSION

PF is a common cause of foot complaints resulting from degeneration of planter fascia. Treatment that stimulates tissue regeneration should be deemed as a better alternative for conservative managements. All the selected and reviewed studies showed significant improvement with no evidence of side effect or complications when PRP was used in treating PF. This suggests that PRP could be an effective mode of treatment for PF with promised safety. It helps in stimulation of new cell growth and thus should be regarded as a suitable modality in treating a degenerative disease. Studies also showed the superiority of PRP when compared with steroid injection.

One of the limitations of these studies include the sample sizes which were frequently small, Absence of placebo, diagnosis of PF, and duration of follow-up might appear to be another limiting factors in the process of assessing the efficacy of PRP. Besides, when selecting a preparation system, many factors must be taken into account, such as volume of autologous blood drawn, centrifuge rate/time, leukocyte concentration, delivery method, activating agent, final PRP volume and final platelet and growth-factor concentration. Due to differences in PRP characteristics, reported evidence for the clinical effectiveness of PRP cannot be generalized to all of these systems. Furthermore, variation of hematologic parameters between patients may also affect the final PRP preparation. Controversies regarding the optimal quantity of platelets and growth factors required for muscle and tendon healing still persist. PRP 's effectiveness is demonstrated with less concentrated preparations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors contributed equally to this work. SKC developed the concept of the work, conducting the literature search, writing the first draft and approval of the final version of the manuscript. FA contributed in the conception of the study, literature search and drafting, revising and approving the manuscript. TSR contributed in, conducting the study, drafting and revising the draft, approval of the final version of the manuscript. All the authors agreed for all aspects of the work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kane D, Greaney T, Shanahan M, Duffy G, Bresnihan B, Gibney R, et al. The role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of idiopathic plantar fasciitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40:1002–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.9.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolgla LA, Malone TR. Plantar fasciitis and the windlass mechanism: A biomechanical link to clinical practice. J Athl Train. 2004;39:77–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis PF, Severud E, Baxter DE. Painful heel syndrome: Results of nonoperative treatment. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:531–5. doi: 10.1177/107110079401501002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin RL, Irrgang JJ, Conti SF. Outcome study of subjects with insertional plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:803–11. doi: 10.1177/107110079801901203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Lloyd-Smith DR, Zumbo BD. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:95–101. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.36.2.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roxas M. Plantar fasciitis: Diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Altern Med Rev. 2005;10:83–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill LH. Plantar Fasciitis: Diagnosis and Conservative Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5:109–117. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199703000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neufeld SK, Cerrato R. Plantar fasciitis: Evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:338–46. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200806000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarde O, Diebold P, Havet E, Boulu G, Vernois J. Degenerative lesions of the plantar fascia: Surgical treatment by fasciectomy and excision of the heel spur. A report on 38 cases. Acta Orthop Belg. 2003;69:267–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leach RE, Seavey MS, Salter DK. Results of surgery in athletes with plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle. 1986;7:156–61. doi: 10.1177/107110078600700305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemont H, Ammirati KM, Usen N. Plantar fasciitis: A degenerative process (fasciosis) without inflammation. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93:234–7. doi: 10.7547/87507315-93-3-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchbinder R. Clinical practice. Plantar fasciitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2159–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp032745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Shazly O, El Hilaly RA, Abou El Soud MM, El Sayed MN. Endoscopic plantar fascia release by hooked soft-tissue electrode after failed shock wave therapy. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:1241–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bordelon RL. Heel pain. In: Mann RA, editor. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1993. pp. 837–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landorf KB, Keenan AM, Herbert RD. Effectiveness of different types of foot orthoses for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2004;94:542–9. doi: 10.7547/0940542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin JE, Hosch JC, Goforth WP, Murff RT, Lynch DM, Odom RD. Mechanical treatment of plantar fasciitis. A prospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2001;91:55–62. doi: 10.7547/87507315-91-2-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acevedo JI, Beskin JL. Complications of plantar fascia rupture associated with corticosteroid injection. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:91–7. doi: 10.1177/107110079801900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalaci A, Cakici H, Hapa O, Yanat AN, Dogramaci Y, Sevinç TT. Treatment of plantar fasciitis using four different local injection modalities: A randomized prospective clinical trial. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2009;99:108–13. doi: 10.7547/0980108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim C, Cashdoallar MR, Mendicino RW, Catanzariti AR, Fuge L. Incidence of plantar fascia ruptures following corticosteroid injection. Foot Ankle Spec. 2010;3:335–7. doi: 10.1177/1938640010378530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leach R, Jones R, Silva T. Rupture of the plantar fascia in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:537–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatli YZ, Kapasi S. The real risks of steroid injection for plantar fasciitis, with a review of conservative therapies. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2009;2:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s12178-008-9036-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong MW, Tang YY, Lee SK, Fu BS. Glucocorticoids suppress proteoglycan production by human tenocytes. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:927–31. doi: 10.1080/17453670610046118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall MP, Band PA, Meislin RJ, Jazrawi LM, Cardone DA. Platelet-rich plasma: Current concepts and application in sports medicine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:602–8. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200910000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond JW, Hinton RY, Curl LA, Muriel JM, Lovering RM. Use of autologous platelet-rich plasma to treat muscle strain injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1135–42. doi: 10.1177/0363546508330974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCarrel T, Fornier L. Temporal growth factor release from platelet-rich plasma, trehalose lysophilized platelets, and bone marrow aspirate and their effect on tendon and ligament gene expression. J Orthop Res. 2009;27:1033–42. doi: 10.1002/jor.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anitua E, Andía I, Sanchez M, Azofra J, del Mar Zalduendo M, de la Fuente M, et al. Autologous preparations rich in growth factors promote proliferation and induce VEGF and HGF production by human tendon cells in culture. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engebretsen L, Steffen K, Alsousou J, Anitua E, Bachl N, Devilee R, et al. IOC consensus paper on the use of platelet-rich plasma in sports medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:1072–81. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.079822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fallouh L, Nakagawa K, Sasho T, Arai M, Kitahara S, Wada Y, et al. Effects of autologous platelet-rich plasma on cell viability and collagen synthesis in injured human anterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2909–16. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anitua E, Sanchez M, Nurden AT, Zalduendo M, de la Fuente M, Azofra J, et al. Reciprocal actions of platelet-secreted TGF-beta1 on the production of VEGF and HGF by human tendon cells. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:950–9. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000255543.43695.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfeffer G, Bacchetti P, Deland J, Lewis A, Anderson R, Davis W, et al. Comparison of custom and prefabricated orthoses in the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:214–21. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole C, Seto C, Gazewood J. Plantar fasciitis: Evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:2237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ragab EM, Othman AM. Platelets rich plasma for treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:1065–70. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1505-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinelli N, Marinozzi A, Carnì S, Trovato U, Bianchi A, Denaro V. Platelet-rich plasma injections for chronic plantar fasciitis. Int Orthop. 2013;37:839–42. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1741-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar V, Millar T, Murphy PN, Clough T. The treatment of intractable plantar fasciitis with platelet-rich plasma injection. Foot (Edinb) 2013;23:74–7. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Malley MJ, Vosseller JT, Gu Y. Successful use of platelet-rich plasma for chronic plantar fasciitis. HSS J. 2013;9:129–33. doi: 10.1007/s11420-012-9321-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim E, Lee JH. Autologous platelet-rich plasma versus dextrose prolotherapy for the treatment of chronic recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. PM R. 2013;6(2):152–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aksahin E, Dogruyol D, Yüksel HY, Hapa O, Dogan O, Celebi L, et al. The comparison of the effect of corticosteroids and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:781–5. doi: 10.1007/s00402-012-1488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monto RR. Platelet-rich plasma efficacy versus corticosteroid injection treatment for chronic severe plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35:313–8. doi: 10.1177/1071100713519778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jain K, Murphy PN, Clough TM. Platelet rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection for plantar fasciitis: A comparative study. Foot (Edinb) 2015;25:235–7. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherpy NA, Hammad MA, Hagrass HA, Samir H, Abu-ElMaaty SE, Mortad MA. Local injection of autologous platelet rich plasma compared to corticosteroid treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis patients: A clinical and ultrasonographic follow-up study. Egypt Rheumatologist. 2015 doi:10.1016/j.ejr.2015.09.008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shetty VD, Dhillon M, Hegde C, Jagtap P, Shetty S. A study to compare the efficacy of corticosteroid therapy with platelet-rich plasma therapy in recalcitrant plantar fasciitis: A preliminary report. Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;20:10–3. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson JJ, Lee KS, Miller AT, Wang S. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of chronic plantar fasciopathy in adults: A case series. Foot Ankle Spec. 2014;7:61–7. doi: 10.1177/1938640013509671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Say F, Gürler D, Inkaya E, Bülbül M. Comparison of platelet-rich plasma and steroid injection in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48:667–72. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2014.13.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Everts PA, Devilee RJ, Brown Mahoney C, van Erp A, Oosterbos CJ, Stellenboom M, et al. Exogenous application of platelet-leukocyte gel during open subacromial decompression contributes to improved patient outcome. A prospective randomized double-blind study. Eur Surg Res. 2008;40:203–10. doi: 10.1159/000110862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Griffin XL, Smith CM, Costa ML. The clinical use of platelet-rich plasma in the promotion of bone healing: A systematic review. Injury. 2009;40:158–62. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gumina S, Campagna V, Ferrazza G, Giannicola G, Fratalocchi F, Milani A, et al. Use of platelet-leukocyte membrane in arthroscopic repair of large rotator cuff tears: A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:1345–52. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Orrego M, Larrain C, Rosales J, Valenzuela L, Matas J, Durruty J, et al. Effects of platelet concentrate and a bone plug on the healing of hamstring tendons in a bone tunnel. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:1373–80. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gosens T, Den Oudsten BL, Fievez E, van ’t Spijker P, Fievez A. Pain and activity levels before and after platelet-rich plasma injection treatment of patellar tendinopathy: A prospective cohort study and the influence of previous treatments. Int Orthop. 2012;36:1941–6. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1540-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weibrich G, Hansen T, Kleis W, Buch R, Hitzler WE. Effect of platelet concentration in platelet-rich plasma on peri-implant bone regeneration. Bone. 2004;34:665–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Everts PA, Knape JT, Weibrich G, Schönberger JP, Hoffmann J, Overdevest EP, et al. Platelet-rich plasma and platelet gel: A review. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2006;38:174–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peerbooms JC, van Laar W, Faber F, Schuller HM, van der Hoeven H, Gosens T. Use of platelet rich plasma to treat plantar fasciitis: Design of a multi centre randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puttaswamaiah R, Chandran P. Degenerative plantar fasciitis: A review of current concepts. Foot. 2007;17:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goff JD, Crawford R. Diagnosis and treatment of plantar fasciitis. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:676–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Díaz-Llopis IV, Rodríguez-Ruíz CM, Mulet-Perry S, Mondéjar-Gómez FJ, Climent-Barberá JM, Cholbi-Llobel F. Randomized controlled study of the efficacy of the injection of botulinum toxin type A versus corticosteroids in chronic plantar fasciitis: Results at one and six months. Clin Rehabil. 2012;26:594–606. doi: 10.1177/0269215511426159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kiter E, Celikbas E, Akkaya S, Demirkan F, Kiliç BA. Comparison of injection modalities in the treatment of plantar heel pain: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:293–6. doi: 10.7547/0960293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peerbooms JC, Sluimer J, Bruijn DJ, Gosens T. Positive effect of an autologous platelet concentrate in lateral epicondylitis in a double-blind randomized controlled trial: Platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injection with a 1-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:255–62. doi: 10.1177/0363546509355445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee TG, Ahmad TS. Intralesional autologous blood injection compared to corticosteroid injection for treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:984–90. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ryan MB, Wong AD, Gillies JH, Wong J, Taunton JE. Sonographically guided intratendinous injections of hyperosmolar dextrose/lidocaine: A pilot study for the treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:303–6. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.050021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scioli MW. Platelet-rich plasma injection for proximal plantar fasciitis. Tech Foot Ankle. 2011;10:7–10. [Google Scholar]