Abstract

BACKGROUND

Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness and low mental health literacy have been found to be barriers to seeking help for mental health related issues in adolescents. Prior research has found that it is possible to improve these outcomes using school-based mental health interventions. The purpose of this study was to review empirical literature pertaining to universal interventions addressing mental health among students enrolled in US K-12 schools, especially related to health disparities in vulnerable populations.

METHODS

PsycINFO, Cochrane Library, PUBMED, and reference lists of relevant articles were searched for K-12 school-based mental health awareness interventions in the US. Universal studies that measured knowledge, attitudes, and/or help-seeking pertinent to mental health were included.

RESULTS

A total of 15 studies were selected to be part of the review. There were 7 pretest/posttest case series, 5 non-randomized experimental trial, 1 Solomon 4-groups, and 2 randomized controlled trial designs (RCT). Nine studies measuring knowledge, 8 studies measuring attitudes, and 4 studies measuring help-seeking, indicated statistically significant improvement.

CONCLUSIONS

Although results of all studies indicated some level of improvement, more research on implementation of universal school-based mental health awareness programs is needed using RCT study designs, and long-term follow up implementation.

Keywords: mental illness, mental health literacy, school-based mental health interventions, school health services, school mental health services

Mental health is a critical public health issue worldwide. The lifetime prevalence rate for any mental disorder in adults is 46.4%1, and 46.3% in adolescents2. Neuropsychiatric disorders such as alcohol addiction and depression are the leading contributors to Disability Adjusted Life Years in the United States (US).3 Adolescence is an opportune time to intervene on mental illness since many mental health conditions have their onset before the age of 20.1 For example, suicide is the third leading cause of death among individuals between the ages of 10 and 19.4 Considering that many young individuals with severe mental disorders have never received specialized mental health care,5 barriers to mental health treatment in youth such as mental illness stigma and mental health literacy must be addressed6 to improve their health trajectories and prevent disability later in life.

Stigma and mental health literacy play an important role in the trajectories of individuals with mental illness. Individuals with mental illnesses are often stigmatized and suffer adverse consequences, such as social isolation and limited life chances that result from this stigma.7 This is concerning given that stigma associated with mental illness interferes with seeking mental health care8 and adherence to mental health services.9 In fact, many adolescents report moderate to high levels of mental health stigma and low levels of mental health literacy,10 indicating the importance of mental health education in this population. Adolescents often fear friends, peers, and school teachers/staff discovering that they suffer from mental illness.11 Among adolescents who do enter mental health treatment, high mental illness stigma and low mental health literacy are 2 important factors that may play a role in premature termination of treatment.12–14

For adolescents, many of these poor mental health outcomes can be prevented by universal mental health interventions introduced early in life. Universal interventions have a focus on whole populations with the aim of reducing risk factors and/or enhancing protective ones. Schools are an obvious setting to implement universal mental health interventions targeting adolescents; socio-ecological models of health recognize the importance of school institutions in individual level health outcomes. There are a variety of school mental health interventions that can be adopted and implemented. However, universal school-based mental health interventions measuring knowledge, attitudes, and/or help-seeking in the US have not been considered within a single review. Prior systematic reviews in school-based settings have been published, but have tended to focus on more specific areas of mental health, such as depression, suicide, or violence, and have included studies that measured other outcomes, including conduct, academics, and social/emotional learning, among others. This systematic review synthesizes all US-based studies examining the effectiveness of universal interventions on mental health in K-12 school-based settings.

METHODS

The Principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines for data retrieval and reporting were used for this systematic review.15

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in March 2016 using PUBMED, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Library. The main aim of the search was to find studies examining the effectiveness of universal school-based mental health awareness interventions in US K-12 schools. Search terms included combinations of specific key words: mental health, school, prevention, awareness, stigma, promotion, educational, preventive, and program. These key words were selected based on the inclusion criteria of studies that were being searched for. Although search terms did not include specific mental illnesses such as depression, we did not disqualify universal awareness programs focusing on a specific area of mental health, such as depression, that were found using the search terms listed above. A second reviewer conducted a supplementary electronic literature search using similar methods.

Eligibility Criteria

Only English written studies conducted within the US in a school setting were included. Non-research or gray literature articles were not included. Participants had to be students enrolled in a K-12 school. The studies had to be universal in nature; selected or indicated interventions were not included in this review. For example, studies that focused solely on students diagnosed with mental illnesses were not included. Outcomes included change in knowledge, attitudes, and/or help-seeking (willingness, intentions, attitudes, likelihood, behaviors, and knowledge). Mental health studies that only measured other outcomes, such as behavior (not related to help-seeking), academic change, peer victimization, teacher/student relationship, coping, and decision making skills were not included. Studies involving parents beyond consenting for students to participate in a study were not included. No exclusion was placed on study design or age of publication.

Critical Appraisal

Risk of bias and quality of evidence were assessed by 2 reviewers using The Joanna Briggs Institute Descriptive/Case-series and Randomized Control Pseudo-randomized Trial Critical Appraisal Tools.16

RESULTS

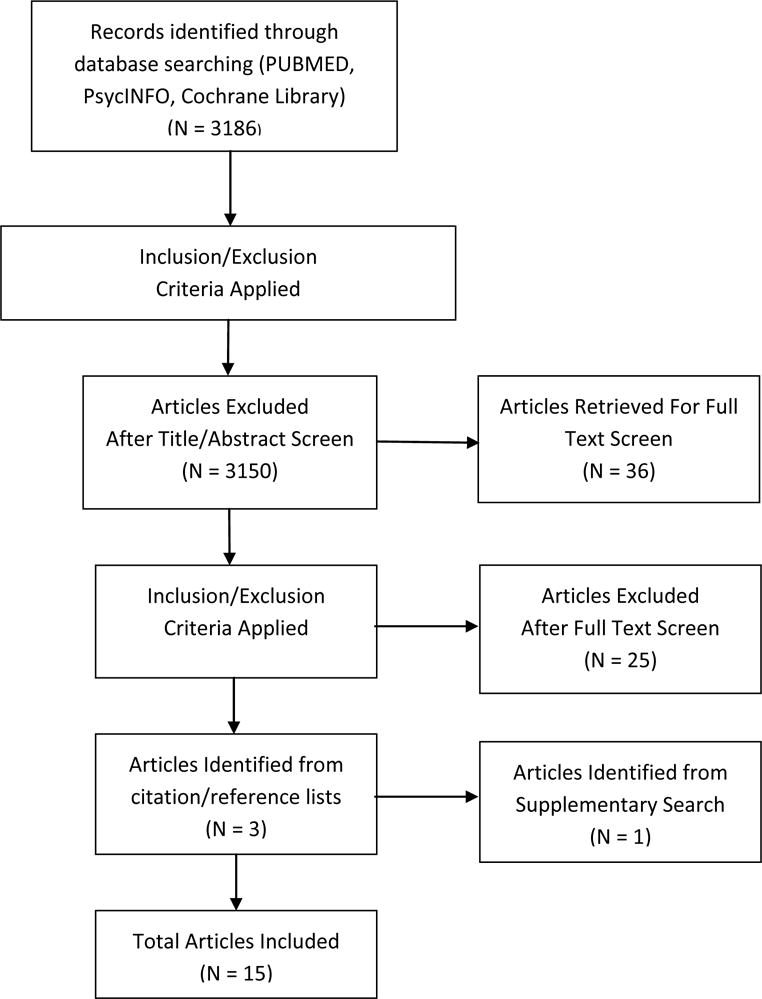

A total of 3186 articles were produced from the 3 databases. After title/abstract review, 36 were selected for full article review. After full review of these articles, 25 were eliminated17–41 because they did not meet the inclusion criteria that had been established for this systematic review. After reference lists of relevant articles were searched, an additional 3 articles were selected to be part of the study. One additional article was identified and selected for inclusion from the supplementary literature search. A total of 15 studies met the inclusion criteria for the review. A detailed description of the search is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart Summary of Search Results

Participants and Settings

All interventions took place in the US. Sample sizes ranged from 30 students42 to 5949 students43 and involved students from grades 5–12. Six out of 15 studies did not report on the race or ethnicity of participants;42,44–48 five out of 15 studies reported either being implemented in communities where white was the predominant race, or a sample that was predominantly white,43,49–52 and 4 out of 15 studies reported a sample that consisted of a high percentage (40% or higher) of minority individuals.53–56

Interventions

Studies were published between 198847 and 2015.54 The aims of the programs reviewed included improving mental health/illness knowledge,42,43,45,47,49–56 improving attitudes toward mental health or illness,44,46–53,55,56 and to increase help-seeking.43,44,46–48,51,53 The content of the programs included primarily instructor led traditional mental health education curriculums, some included one-time presentations or video components. Twelve out of 15 interventions consisted of mental health education curriculums varying in length, and implemented in the classroom.42,43,45–47,49,51–56 Length was defined as minutes, days, weeks, lessons, modules, and sessions. Three out of 15 programs were a one-time educational presentation.44,48,50 Interventions were delivered by a faculty advisor, counselor, teacher, nurse, researcher, clinician, mental health professional, staff member, or consumer. More details can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 15 Included Studies, Ordered by Date of Publication

| Study Name | Focus Area | Design | Sample | Sample SES & Race/ethnicity | Program Length | Knowledge | Attitudes | Help-Seeking | Risk for Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirito et al. (1988) (unnamed) | Suicide | Solomon 4-groups design | CG: n=182, TG: n=291, Students from 5 high schools | Sample SES and race/ethnicity not reported | 6 week curriculum | TG increased knowledge, F(1,402) = 40.42, p < .001 | No statistically significant effect of intervention on attitudes | No statistically significant effect of intervention on help seeking | High |

| Petchers et al. (1988) (unnamed) | General Mental Health | Nonrandomized experimental trial | 102 students from two high schools | Sample from predominantly White suburban community | Six lesson curriculum supplement + video component | Knowledge and opinions about mental health questionnaire scores higher in TG at posttest. CG: 63.81, TG: 74.77, t (100) = 5.67, p < .001 | Knowledge and opinions about mental health questionnaire scores higher in TG at posttest CG: 63.81, TG: 74.77, t (100) = 5.67, p < .001 | N/A | High |

| Battaglia et al. (1990) - Mental Health Awareness Week | General Mental Health | Nonrandomized experimental trial | TG: n=1380 CG: n=282 From middle and high schools |

Sample SES and race/ethnicity not reported | 45 minute presentation | N/A | TG indicated a significantly greater desire to hear more about mental health issues, (χ2 = 29.5, df = 1, p < .001). Students’ attitudes towards psychiatrists was more positive in the TG compared to the CG, F (1, 1588) = 79.0, p < .001 | TG was more likely to seek psychiatric help when exposed to previous talks: about psychiatrists; F (1, 559) = 6.50, p < 0.05, about depression/suicide; F (1, 1569) = 6.20, p < 0.05, about drugs/alcohol; F (1, 571) = 6.00, p < 0.05. TG more often indicated that they would [tell family, a psychiatrist, a teacher (p < .05)], and a counselor (p < .005) about getting help as a first step. | High |

| Esters et al. (1998) (unnamed) | General Mental Health | Nonrandomized experimental trial | 40 students from one high school | Sample SES and race/ethnicity not reported | Instructional unit presented during 3 days of health class curriculum | N/A | Positive relationship between intervention and score on OMI questionnaire in TG (r =.83). OMI scores did not decrease significantly at 12-week posttest, t (19) = 2.01, p > .025 | Positive relationship between intervention and score on FTAS questionnaire in TG (r = .92). FTAS scores did not decrease significantly at 12-week posttest, t (19) = .47, p > .025 | High |

| Aseltine & DeMartine (2004) – Signs of Suicide (SOS) | Suicide | Randomized Controlled Trial | TG = 1027, CG = 1073, students from 5 high schools | Mixed, diverse SES and race/ethnicity in sample (large % minority) | Educational video, discussion guide, and screening over 2 days | Greater knowledge of depression and suicide seen in TG at posttest (p < .05) | More adaptive attitudes seen in TG at posttest (p < .05) | No statistically significant effect of intervention on help-seeking | Medium |

| Watson et al. (2004) - The Science of Mental Illness | General Mental Health | Pretest/posttest case series | 1566 students from middle schools | 70% White, 16% Hispanic | 5 lesson curriculum supplement,45 minute classroom time | Improvement in mental health knowledge score, t (1,249) −44.575, p = 0.000. | Significant improvement in stigmatizing attitudes, t (1,249) 2.821, p = 0.005. | N/A | High |

| DeSocio & Schrinsky (2006) (unnamed) | General Mental Health | Pretest/posttest case series | 370 elementary and middle school students | Sample SES and race/ethnicity not reported | Six modules taught in six 45 minute class periods | Mean student scores improved from pre to posttest (+1.5 mean increase, p = .000) | N/A | N/A | High |

| Tacker & Dobie (2008) – MasterMind: Empower Yourself With Mental Health | General Mental Health | Pretest/posttest case series | 30 eighth grade students from one middle school | Sample SES and race/ethnicity not reported | 6 week curriculum, 80 minutes per week | Increase seen in student knowledge of mental health issues, results did not achieve statistical significance. | N/A | N/A | High |

| Spagnolo et al. (2008) – Recovery from Serious Mental Illness is Possible | General Mental Health | Pretest/posttest case series | 277 high school students from 4 high schools | Sample SES and race/ethnicity not reported | 60–90 minute module | N/A | Significant improvement seen in stigmatizing attitudes (p ≤ .00) | Significant improvement seen in willingness to seek help (p ≤ .00) | High |

| Nikitopoulos et al. (2009) – Understanding Violence | Violence | Posttest case series | 224 students from an elementary school | 56% Black, 39% Latino, low SES | Six 60–90 minute modules yearly for 3 years | Moderate understanding of topics related of crime, violence, and law enforcement seen (78–86%). (No analysis beyond descriptive statistics specified) | Students’ indicated the importance of violence issues and community as a topic (>90% of respondents agreeing with all corresponding items). (No analysis beyond descriptive statistics specified) | N/A | High |

| Pinto-Foltz et al. (2011) – In Our Own Voice | General Mental Health | Randomized Controlled Trial | TG: n=95 CG: n=61 From 2 high schools |

69% White, moderate to high SES | 60 minute presentation | No statistically significant effect of intervention on knowledge at immediate posttest. At 4+8 week posttest, TG scored significantly higher on mental health literacy (95% CI = .71–3.53, p =.03) | No statistically significant effect of intervention on stigmatizing attitudes immediately after intervention and at 4+8 week posttest. | N/A | Medium |

| Wahl et al. (2011) – Breaking the Silence | General Mental Health | Nonrandomized experimental trial | TG = 106, CG = 87 7th and 8th graders from 4 middle schools | 45% Caucasian, 21% African American, 19% Hispanic, 5% mixed race | Three 40–50 minute classes held over 1 week during science/health/PE class | TG demonstrated improvement in knowledge at immediate posttest and follow-up, F (2, 382) = 34.6, p < .001 | TG demonstrated improvement in attitudes at immediate posttest and follow-up, F (2, 382) = 4.6, p =.012 | N/A | High |

| Strunk et al. (2014) – Surviving the Teens | Suicide | Nonrandomized experimental trial | TG: n=966 CG: n=581 Students from 9 high schools |

84% White | Four 50-minute sessions over 4 consecutive days. | TG demonstrated significant improvements in knowledge of depression risk factors, F (1, 624) = 9.70, p =.002, suicide risk factors, F (1, 624) = 9.24, p =.002, suicide warning signs, F (1, 624) = 9.66, p = .002, and suicide myths and facts, F (1, 624) = 23.264, p < .001. | TG demonstrated significant improvement in stigmatizing attitudes, F (1, 497) = 33.69, p < .001, and in perceived importance in knowing suicidal warning signs and steps to take with suicidal friends, F (1, 498) = 34.44, p < .001 | TG demonstrated significantly greater improvement in intention to help self or friends if suicidal, F (1, 498) = 102.32, p < .001. | Medium |

| Schmidt et al. (2015) – Yellow Ribbon Ask 4 Help | Suicide | Pretest/posttest case series | 5949 students from middle and high schools | 73% White, 20% African American | Training offered during individual classes for 4 years | Data suggest improvement in students’ knowledge about suicide (No analysis beyond descriptive statistics specified) | N/A | Data suggest improvement in students’ knowledge about help-seeking (No analysis beyond descriptive statistics specified) | High |

| Labouliere et al. (2015) – A Promise For Tomorrow | Suicide | Pretest/posttest case series | 1365 high school students from a school district | 45.1% Hispanic, 26.6% Caucasian, 13.3% mixed race | Three 45–50 minute sessions held during individual health classes within one-week | Significant improvement in suicide related knowledge (p < .001) | N/A | N/A | High |

Outcomes

Knowledge of mental health

Mental health knowledge was conceptualized in different ways. This included knowledge of mental health, mental illness, violence, mental health issues, mental health literacy, depression, depression risk factors, suicide, suicide risk factors, suicide warning signs, and suicide myths and facts. Twelve of the 15 selected studies measured students’ knowledge of mental health,42,43,45,47,49–56 and all found improvement in knowledge at posttest (Table 1). However, it is important to note that not all studies found statistical significance42 and/or specified statistical analysis beyond descriptive statistics.43,55

Attitudes toward mental health

Attitudes toward mental health were measured in multiple ways as well. These included attitudes toward suicide, opinions about mental health, desire to hear more about mental health issues, attitudes towards psychiatrists, opinions about mental illness, attitudes toward mental illness, stigma related attitudes, importance towards violence and community, and mental illness stigma, among others. Eleven out of the 15 selected studies measured attitudes toward mental health.44,46–53,55,56 Nine of these 11 studies found improvements in attitudes toward mental health at posttest.44,46–49,51,52,55,56 One of these 8 studies did not conduct statistical analysis beyond descriptive statistics.55 However, 2 of the 11 studies measuring attitudes did not find a significant effect of the intervention on improving attitudes toward mental health.50,53 A couple of distinct observations regarding these 2 studies are that they were 2 out of 3 studies in this systematic review that implemented a rigorous study design, and that both of these studies were 2 out of 5 that implemented a follow-up posttest beyond immediate posttest. Additionally, both of these studies had similar results in that there was a statistically significant increase found in mental health knowledge, but no significant effect of the intervention found on attitudes. Table 1 shows additional details.

Help-seeking

Help-seeking was assessed by measuring help seeking behaviors, intentions to seek help, likelihood to seek help, attitudes toward seeking psychological help, willingness to seek help, and help seeking knowledge. Seven out of the 15 selected studies measured help seeking.43,44,46–48,51,53 Five out of these 7 studies demonstrated improvement in help seeking.43,44,46,48,51 One of these 4 studies did not specify statistical analysis beyond descriptive statistics.43 Two of the 7 studies measuring help seeking found no significant intervention effect on help seeking.47,53 Once again, the observable distinctions of these studies were that they were 2 of 3 that implemented a rigorous study design, and 2 of 5 that implemented a long-term follow up posttest. Additionally, both of these studies were 2 of 3 that measured all 3 outcomes; knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking. Table 1 shows additional details.

Risk of Bias and Quality of Evidence

The JBI Descriptive/Case-series and Randomized Control Pseudo-randomized Trial Critical Appraisal Tools16 have been previously validated to assess scientific quality of research studies. Among quasi-experimental and randomized controlled trials in this review, risk of bias was considered medium-high. Common themes found among experimental studies were lack of true random assignment, lack of allocator and outcome assessor blinding, and lack of reporting/analyzing study dropouts.

Among case-series design studies, risk of bias was considered to be high and quality of evidence was affected. Common themes found among case series studies were lack of true random sampling, not clearly defining inclusion criteria, not listing or dealing with confounding factors, not using objective criteria to assess outcomes, lack of long-term follow up, and lack of reporting/analyzing study drop outs.

In many instances, authors did not state information necessary to assess risk of bias and quality of evidence, in these instances it was assumed that a risk of bias was present and/or that quality of evidence was affected. All reasons for increased risk of bias and lowered quality of evidence listed above do not apply to all studies included in this review. This section is meant to provide a general overview of risk of bias and methodological quality found by reviewers among included studies. See Table 1 for specification by article.

These findings speak to the importance of future investigators conducting school-based mental health awareness trials to be more rigorous with regards to study procedures in order improve quality of evidence and lower risk of bias. Results of this systematic review should be interpreted with caution due to these findings.

Included Studies Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nine of the 15 included articles reported sources of funding and/or support.45,48–50,52–56 No apparent conflicts of interest were noted from these sources, and no additional conflicts were reported among these articles. One article declared no potential conflict of interest or financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication.51 All other articles did not report potential conflict of interests, funding sources, or sources of support.42–44,46,47

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this review was to identify and describe all mental health interventions in US school-based settings that adopted universal approaches. To my knowledge, this is the first systematic review to examine all universal school mental health studies in the US examining these outcomes (knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking). Prior systematic reviews have focused on more specialized mental health areas, such as suicide or depression prevention studies, and measured other outcomes such as academic, conduct, or symptom change. Because this review did not discriminate by specialized mental health area, age of publication, or study design type, we were able to conduct a more comprehensive assessment of the state of the science in universal school-based mental health stigma and literacy interventions.

The studies in this systematic review aimed to evaluate interventions in samples that represented whole school populations. As far as knowledge of mental health, all studies measuring this outcome demonstrated improvements. Most of the studies measuring attitudes and help seeking also demonstrated improvements. Although the majority of studies found positive results, a major fallback of the studies included in this systematic review is that only three of them used a randomized controlled50,53 or Solomon 4-groups study design;47 all others used nonrandomized experimental trial and pretest/posttest case series designs. This means that most of the universal mental health research studies conducted in schools are using study designs that lack strength in establishing true cause-effect relationships. Non-randomized experiments and case series studies lack strong internal validity and causal assessment. With this being said, it’s important to note that all studies that implemented a RCT or Solomon 4-groups design in this review had some unfavorable results. Spirito et al47 found that the intervention had a positive effect on knowledge at 10-week posttest, but no effects on attitudes and help seeking. Pinto-Foltz et al50 found that the intervention had a positive effect on knowledge at 4- and 8-week posttest, but not at immediate posttest, and no effect on stigma related attitudes at any time point. Aseltine and DeMartino53 found that the intervention had a positive effect on knowledge and attitudes at 3-month posttest, but no effect on help-seeking. This speaks to the importance of using rigorous study designs in order to make true causal assessments, and the possibility that results obtained by studies with non-rigorous designs were a result of other factors, rather than the intervention itself.

Help seeking was the least common outcome that was assessed among studies; only 7 of the 15 included studies measured help seeking,43,44,46–48,51,53 and 4 of these studies were focused on suicide awareness.43,47,51,53 Help seeking is a determinant of health for those who suffer from many mental health issues, not only risk of suicide. Given the current gap in mental health care use in adolescents, examining help seeking as a factor in school-based mental health interventions in conjunction with knowledge/attitudes is important and recommended. More research is needed measuring help seeking in universal school mental health programs.

Mental health knowledge or literacy was the most commonly studied outcome, followed by attitudes toward mental health. One specific attitude toward mental health that has been linked to multiple poor mental health outcomes is stigma. Of the 11 studies measuring attitudes, only 5 specifically addressed stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness.48,50–52,56 This indicates a gap in the literature with regards to the effects of universal school mental health interventions in improving stigma related attitudes. Considering that the literature indicates a link between stigma and poor mental health outcomes, more research is needed examining the effect of universal school mental health interventions on stigmatizing attitudes in adolescents.

Also worth noting is that only 3 of the 15 studies measured all three outcomes; knowledge, attitudes, and help seeking.47,51,53 This indicates a disparity in the literature regarding school mental health interventions and their effects on multiple individual level outcomes. It should not be assumed for example that an increase in mental health knowledge signifies an improvement in mental health attitudes or help seeking. In fact, results of three studies in this review demonstrate that improvement in mental health knowledge may not correlate well with changes in attitudes or help-seeking,47,50,53 indicating that there should be diversity in outcomes that are measured in mental health interventions. Mental health issues are caused by a multitude of interrelated factors, therefore interventions should be comprehensive and strive to address many of these interconnected factors, rather than single ones.

Lastly, it was disappointing to find that 7 out of 15 studies did not collect information on race/ethnicity from the sample.42,44–49 Additionally, only 4 out of 8 studies that did collect this information reported a sample with 40% or greater minority representation.53–56 Overall positive results were seen in these 4 studies; however, Aseltine and DeMartino53 found no effect of the intervention on help-seeking. This was the only study out of these 4 that implemented a rigorous study design. Future researchers should aim to collect race/ethnicity information from participants, and implement universal school-based mental health interventions in settings that include greater representation of minority and vulnerable populations in order to increase generalizability of findings to individuals that are at higher risk for health disparities.

Conclusions

This review on universal mental health intervention programs in US schools overall found improvements in mental health knowledge, attitudes, and help-seeking in adolescents. Nonetheless, internal validity, causal assessment, and quality of evidence were weakened since most studies did not use rigorous study designs and procedures. Most included studies did not examine all 3 outcomes even though the literature demonstrates that these 3 outcomes are highly interrelated. Future researchers should intend to implement these kinds of studies with rigorous procedures, RCT study designs, long-term follow up, and evaluating multiple outcomes that affect mental health. In addition, future researchers should more often consider implementing interventions in school settings that contain more minority/vulnerable population representation.

Limitations

A limitation of this work is that only a single individual conducted the systematic literature search, article selection, and data abstraction. Having multiple individuals involved in these steps of a systematic review can help strengthen the reliability, accuracy, and comprehensiveness of findings. The results of this review should be interpreted in light of this limitation.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

A common reason why articles were excluded from this review was because the outcomes focused solely on conduct and academic success. Whereas these outcomes are important factors, additional research is needed focusing more specifically on mental health outcomes. Studies focusing on mental health outcomes are important in order to prevent poor mental health in adolescence and in adulthood. Additionally, many school-based mental health interventions found in the initial search had an indicated or selected approach, such as those focusing on individuals at risk for suicide, or suffering from depression. Although selected and indicated interventions are important, universal interventions can address these issues as well from a primary prevention standpoint. Taking into consideration the current lack of universal mental health programs in schools, more of these kinds of interventions should be researched and implemented.

Additionally, there is a need for prospective school-based universal mental health interventions to determine long-term effects. Most of the studies in this review had a pre and immediate posttest design. Long-term follow up is important to examine the maintenance of results after an intervention has concluded, and the fact that results were mixed among the four studies46,47,50,53 that implemented long-term follow up components speaks to the importance of and need for continuing to study long-term effects in school-based interventions. Currently, many universal school-based mental health programs are not following up with participants after immediate posttest. This is a limitation since we cannot verify if the results are maintained at later time points. Future researchers should take this into consideration and aim to implement interventions with long-term follow up of participants in schools.

An additional gap in the literature exists on research exploring the barriers and challenges to implementing school-based mental health programs. Implementing mental health interventions in schools can be difficult for many different reasons. One possible reason is the historical controversial nature of teaching kids about mental illness; thinking that a mental health intervention will have negative effects on the child. However, researchers have demonstrated mostly positive effects of school-based mental health interventions, but this is not something that school teachers, staff, and parents are necessarily well versed in. Another challenge is the lack of education in research among school administration. For example, not being able to understand the importance of control groups or random assignment in research can make it difficult to implement a study with a randomized controlled trial design in a school. School administration may want all participating students to receive the intervention as an ultimatum to being able to implement the program, and dismiss the idea of control groups and random assignment. Twelve out of 15 studies in this review did not use a rigorous study design42–46,48,49,51,52,54–56; the potential barrier of lack of research education may have played a role here. A potential way to address the issue of control groups not receiving the intervention is to make arrangements to deliver the intervention to control group participants after the study has concluded; a method used by Strunk and Vidourek51 and Aseltine and DeMartino.53 Other reasons for potential difficulties in implementation are coordinating with the various stakeholders in schools, disruption of the current school curriculum, parental consent, and lack of incentives. It’s important for researchers to discuss these and other difficulties that they encounter when attempting to implement a program in a school; doing so would help facilitate future research in school settings.

Lastly, it’s important to discuss the implications for practice in schools beyond research. Common themes found among interventions demonstrating positive results were that they were implemented in the classroom, and had multi-lesson educational formats. This indicates the feasibility of including mental health education into current school curriculums. However, most of the interventions were not delivered by teachers. If the ultimate goal is for mental health education to be included in regular school curriculums, it makes sense for teachers to be deliverers of the interventions, as they would probably be the ones implementing this into real world practice. Future researchers should aim to train teachers to deliver universal school-based mental health interventions as a step toward practice implementation in real world school settings.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was received from the Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research: El Centro, National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant P60MD002266. There were no additional potential conflicts of interest. Additionally, I thank Dr. Rosa Gonzalez-Guarda and Dr. Jessica Roberts Williams for their expertise and guidance during this project. Lastly, special thanks to Ms. Dominique Hardy for her role as research assistant.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, He J-p, Burstein M, et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCSA) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJ, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading Causes of Death Reports, National and Regional, 1999–2010. 2013 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/leading_causes_death.html. Accessed August 31, 2016.

- 5.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Pathophysiology & Prevention of Adolescent & Adult Suicide. Programs for suicide prevention. In: Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE, editors. Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. pp. 273–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsao CIP, Tummala A, Roberts LW. Stigma in mental health care. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(2):70–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.2.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakellari E, Leino-Kilpi H, Kalokerinou-Anagnostopoulou A. Educational interventions in secondary education aiming to affect pupils’ attitudes towards mental illness: a review of the literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(2):166–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(12):1615–1620. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandra A, Minkovitz CS. Stigma starts early: gender differences in teen willingness to use mental health services. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(6):754.e751–e758. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moses T. Being treated differently: stigma experiences with family, peers, and school staff among adolescents with mental health disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):985–993. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda. Washington, DC: USDHHS; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satcher DS. Executive summary: a report of the Surgeon General on mental health. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(1):89–101. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Reviewer’s Manual. Adelaide, South Australia: JBI; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montañez E, Berger-Jenkins E, Rodriguez J, McCord M, Meyer D. Turn 2 us: outcomes of an urban elementary school–based mental health promotion and prevention program serving ethnic minority youths. Child Sch. 2015;37(2):100–107. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farie AM, Cowen EL, Smith M. The development and implementation of a rural consortium program to provide early, preventive school mental health services. Community Ment Health J. 1986;22(2):94–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00754548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durlak JA. Description and evaluation of a behaviorally oriented school-based preventive mental health program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1977;45(1):27–33. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.45.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowen EL, Izzo LD, Miles H, Telschow EF, Trost MA, Zax M. A preventive mental health program in the school setting: description and evaluation. J Psychol. 1963;56(2):307–356. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1963.9916650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone GL, Hinds WC, Schmidt GW. Teaching mental health behaviors to elementary school children. Prof Psychol. 1975;6(1):34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trudeau L, Spoth R, Mason WA, Randall GK, Redmond C, Schainker L. Effects of adolescent universal substance misuse preventive interventions on young adult depression symptoms: mediational modeling. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016;44(2):257–268. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-9995-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walrath C, Garraza LG, Reid H, Goldston DB, McKeon R. Impact of the Garrett Lee Smith youth suicide prevention program on suicide mortality. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):986–993. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibson JE, Flaspohler PD, Watts V. Engaging youth in bullying prevention through community-based participatory research. Fam Community Health. 2015;38(1):120–130. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biddle VS, Kern J, 3rd, Brent DA, Thurkettle MA, Puskar KR, Sekula LK. Student assistance program outcomes for students at risk for suicide. J Sch Nurs. 2014;30(3):173–186. doi: 10.1177/1059840514525968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melnyk BM, Kelly S, Jacobson D, et al. The COPE healthy lifestyles TEEN randomized controlled trial with culturally diverse high school adolescents: baseline characteristics and methods. Contem Clin Trials. 2013;36(1):41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calear AL, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Griffiths KM. Adherence to the MoodGYM program: outcomes and predictors for an adolescent school-based population. J Affect Disord. 2013;147(1–3):338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walter HJ, Gouze K, Cicchetti C, et al. A pilot demonstration of comprehensive mental health services in inner-city public schools. J Sch Health. 2011;81(4):185–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawyer MG, Harchak TF, Spence SH, et al. School-based prevention of depression: a 2-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of the beyondblue schools research initiative. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(3):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muehlenkamp JJ, Walsh BW, McDade M. Preventing non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: the signs of self-injury program. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(3):306–314. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9450-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noam GG, Hermann CA. Where education and mental health meet: developmental prevention and early intervention in schools. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;14(4):861–875. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Winther J, Carlsson A, Vance A. A pilot study of a school-based prevention and early intervention program to reduce oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2014;8(2):181–189. doi: 10.1111/eip.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bulanda JJ, Bruhn C, Byro-Johnson T, Zentmyer M. Addressing mental health stigma among young adolescents: evaluation of a youth-led approach. Health Soc Work. 2014;39(2):73–80. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlu008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sibinga EM, Perry-Parrish C, Chung SE, Johnson SB, Smith M, Ellen JM. School-based mindfulness instruction for urban male youth: a small randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2013;57(6):799–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zafiropoulou M, Thanou A. Laying the foundations of well being: a creative psycho-educational program for young children. Psychol Rep. 2007;100(1):136–146. doi: 10.2466/pr0.100.1.136-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.George MW, Trumpeter NN, Wilson DK, et al. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of an integrated health-mental health promotion program in school mental health services. Fam Community Health. 2014;37(1):19–30. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis KM, DuBois DL, Bavarian N, et al. Effects of positive action on the emotional health of urban youth: a cluster-randomized trial. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(6):706–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodder RK, Daly J, Freund M, Bowman J, Hazell T, Wiggers J. A school-based resilience intervention to decrease tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use in high school students. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:722. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia C, Pintor J, Vazquez G, Alvarez-Zumarraga E. Project Wings, a coping intervention for Latina adolescents: a pilot study. West J Nurs Res. 2013;35(4):434–458. doi: 10.1177/0193945911407524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Srikala B, Kishore KK. Empowering adolescents with life skills education in schools - School mental health program: does it work? Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(4):344–349. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.74310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ottolini F, Ruini C, Belaise C, et al. Promoting psychosocial well-being in adolescence. a controlled study. Rivista di psichiatria. 2012;47(5):432–439. doi: 10.1708/1175.13034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tacker KA, Dobie S. MasterMind: empower yourself with mental health. A program for adolescents. J Sch Health. 2008;78(1):54–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt RC, Iachini AL, George M, Koller J, Weist M. Integrating a suicide prevention program into a school mental health system: a case example from a rural school district. Child Sch. 2015;37(1):18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Battaglia J, Coverdale JH, Bushong CP. Evaluation of a mental illness awareness week program in public schools. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147(3):324–329. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Desocio J, Stember L, Schrinsky J. Teaching children about mental health and illness: a school nurse health education program. J Sch Nurs. 2006;22(2):81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Esters IG, Cooker PG, Ittenbach RF. Effects of a unit of instruction in mental health on rural adolescents’ conceptions of mental illness and attitudes about seeking help. Adolescence. 1998;33(130):469–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spirito A, Overholser J, Ashworth S, Morgan J, Benedict-Drew C. Evaluation of a suicide awareness curriculum for high school students. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1988;27(6):705–711. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spagnolo AB, Murphy AA, Librera LA. Reducing stigma by meeting and learning from people with mental illness. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31(3):186–193. doi: 10.2975/31.3.2008.186.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petchers MK, Biegel DE, Drescher R. A video-based program to educate high school students about serious mental illness. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1988;39(10):1102–1103. doi: 10.1176/ps.39.10.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinto-Foltz MD, Logsdon MC, Myers JA. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of a knowledge-contact program to reduce mental illness stigma and improve mental health literacy in adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(12):2011–2019. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strunk CM, King KA, Vidourek RA, Sorter MT. Effectiveness of the surviving the Teens(R) suicide prevention and depression awareness program: an impact evaluation utilizing a comparison group. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(6):605–613. doi: 10.1177/1090198114531774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watson AC, Otey E, Westbrook AL, et al. Changing middle schoolers’ attitudes about mental illness through education. Schizophr Bull (Bp) 2004;30(3):563–572. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aseltine RH, Jr, DeMartino R. An outcome evaluation of the SOS Suicide Prevention Program. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):446–451. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Labouliere CD, Tarquini SJ, Totura CM, Kutash K, Karver MS. Revisiting the concept of knowledge: how much is learned by students participating in suicide prevention gatekeeper training? Crisis. 2015;36(4):274–280. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nikitopoulos CE, Waters JS, Collins E, Watts CL. Understanding violence: a school initiative for violence prevention. J Prev Interv Community. 2009;37(4):275–288. doi: 10.1080/10852350903196282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wahl OF, Susin J, Kaplan L, Lax A, Zatina D. Changing knowledge and attitudes with a middle school mental health education curriculum. Stigma Res Action. 2011;1(1):44–53. doi: 10.5463/sra.v1i1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]