Abstract

Abscisic acid (ABA), a key plant stress-signaling hormone, is produced in response to drought and counteracts the effects of this stress. The accumulation of ABA is controlled by the enzyme 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED). In Arabidopsis, NCED3 is regulated by a positive feedback mechanism by ABA. In this study in peanut (Arachis hypogaea), we demonstrate that ABA biosynthesis is also controlled by negative feedback regulation, mediated by the inhibitory effect on AhNCED1 transcription of a protein complex between transcription factors AhNAC2 and AhAREB1. AhNCED1 was significantly down-regulated after PEG treatment for 10 h, at which time ABA content reached a peak. A ChIP-qPCR assay confirmed AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 binding to the AhNCED1 promoter in response to ABA. Moreover, the interaction between AhAREB1 and AhNAC2, and a transient expression assay showed that the protein complex could negatively regulate the expression of AhNCED1. The results also demonstrated that AhAREB1 was the key factor in AhNCED1 feedback regulation, while AhNAC2 played a subsidiary role. ABA reduced the rate of AhAREB1 degradation and enhanced both the synthesis and degradation rate of the AhNAC2 protein. In summary, the AhAREB1/AhNAC2 protein complex functions as a negative feedback regulator of drought-induced ABA biosynthesis in peanut.

Plants encounter various environmental stresses throughout life, of which drought is one of the most serious adverse factors restricting plant survival, growth and yield. Abscisic acid (ABA), a key plant stress-signaling hormone, is produced in response to drought and counteracts the effects of this stress1,2. The accumulation of ABA under drought stress conditions is primarily due to the induction of ABA biosynthetic genes3,4. The step involving 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED), which cleaves xanthoxin to produce 9-cis-violaxanthin and 9-cis-neoxanthin, is thought to be rate-limiting in the ABA biosynthesis pathway5,6. In the Arabidopsis genome, there are five NCED (AtNCED) genes. Among them, AtNCED3 plays a key role in ABA biosynthesis during water stress, when the corresponding NCED3 protein accumulates around leaf vascular tissues7. The nced3 mutant line exhibits reduced ABA content, which exacerbates water stress; in contrast, overexpression of NCED3 increases ABA content and enhances survival of water stress3. Genes from other species behave similarly: Zhang et al.8 transformed MhNCED3, the key ABA biosynthesis gene in Malus hupehensis, into Arabidopsis, and the resulting transgenic lines contained higher endogenous ABA levels and showed a higher drought resistance than wild-type.

The NAC (petunia NAM and Arabidopsis ATAF1, ATAF2 and CUC2) transcription factors (TFs) are plant-specific and form one of the largest TF families in plants9. NAC TFs function in multiple developmental processes, as well as in abiotic stress-responsive signaling. For example, NAC019, NAC055 and NAC072 are all induced by drought stress, and transgenic lines constructed with the corresponding genes show strong drought tolerance10. Similarly, overexpression of another NAC TF gene, ATAF1, results in improved drought tolerance; ChIP-qPCR (Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis of Chromatin Immunoprecipitation) shows that ATAF1 binding to the NCED3 promoter correlates with increased NCED3 expression and ABA hormone levels11,12. Several stress-inducible NAC TFs are also induced by ABA: levels of TaNAC29, a NAC TF from wheat, are increased by ABA treatment13. NAC072/RD26 regulates drought-responsive genes in the ABA-dependent pathway, as shown by upregulation of ABA-responsive genes in RD26 overexpression lines14. NAC TFs often target similar consensus sequences in promoter regions, including the NACRES [NAC recognition site, CGT(G/A)] and CDBS (core DNA-binding sequence, CACG) motifs10. NAC019 and NAC055 can interact with the CDBS element in the promoter of VSP1, a jasmonic acid-induced defense response gene15. However, ANAC016, a NAC TF affecting drought-responsive signaling, binds to a NAC016-specific binding motif that does not contain the CDBS NAC binding motif16.

The ABRE binding factor/ABRE binding protein (ABF/AREB) TFs, with nine examples encoded in the Arabidopsis genome, have pivotal functions in ABA-dependent regulation of gene expression under drought stress and represent a subfamily of the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) TF family17. In Arabidopsis, AREB1/ABF2, AREB2/ABF4 and ABF3 are highly induced by ABA and osmotic stress treatment, while ABF1 also controls the TFs downstream of ABA signaling, despite having a lower expression level than ABF2, ABF3 and ABF418. Transgenic plants overexpressing AREB1/ABF2, AREB2/ABF4 or ABF3 exhibit increased ABA sensitivity and improved drought tolerance19,20. The triple AREB/ABF mutant areb1 areb2 abf3 exhibits enhanced ABA insensitivity and reduced tolerance to drought compared with wild-type17. Promoter analysis reveals that most ABA-responsive genes are regulated by ABREs (PyACGTGG/TC), which contain a core ACGT sequence and belong to the G-box (CACGTG) family. Various ABRE-like sequences have been reported, including coupling element (CGCGTG), CE3, hex3 and motif III20,21,22.

A positive feedback mechanism regulates ABA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, where the ABA1, ABA2, ABA3, NCED3 and AAO3 genes are induced by NaCl and ABA; in particular, water stress is a major factor in the induction of NCED323. Exogenous ABA enhances the expression of NCED3 via a distal ABA responsive element (ABRE: GGCACGTG, −2372 to −2364 bp) in its promoter24. However, the positive feedback regulation of NCED3 expression by ABA raises the question of how the plant maintains ABA homeostasis during water stress. In previous work on peanut (Arachis hypogaea), an important cash crop, we cloned and identified NCED1 (AhNCED1), NAC2 (AhNAC2) and AREB1 (AhAREB1)4,25,26. Furthermore, we showed that both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 are induced by ABA in peanut, and that, in an Arabidopsis AhAREB1-overexpression line, transcription of AtNCED3 is significantly suppressed27,28. The AhNCED1 promoter was also cloned, and bioinformatics analysis showed that it contained one NACRE and four ABRE core sequence elements29. The ABRE element overlapped with or was located close to NACRE motifs in the −1500 to −300 bp region of the AhNCED1 promoter. To understand the possible mechanisms of negative feedback regulation of ABA biosynthesis, we decided to investigate whether AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 can coordinate negative control of AhNCED1 expression in peanut. In this study, we report that, during the response to ABA, AhAREB1 functions as a negative regulator of the ABA biosynthesis gene AhNCED1, acting synergistically with AhNAC2, with which it forms a protein complex. In addition, ABA plays an important role in water stress-induced feedback control of peanut ABA biosynthesis by affecting the stability of AhAREB1.

Results

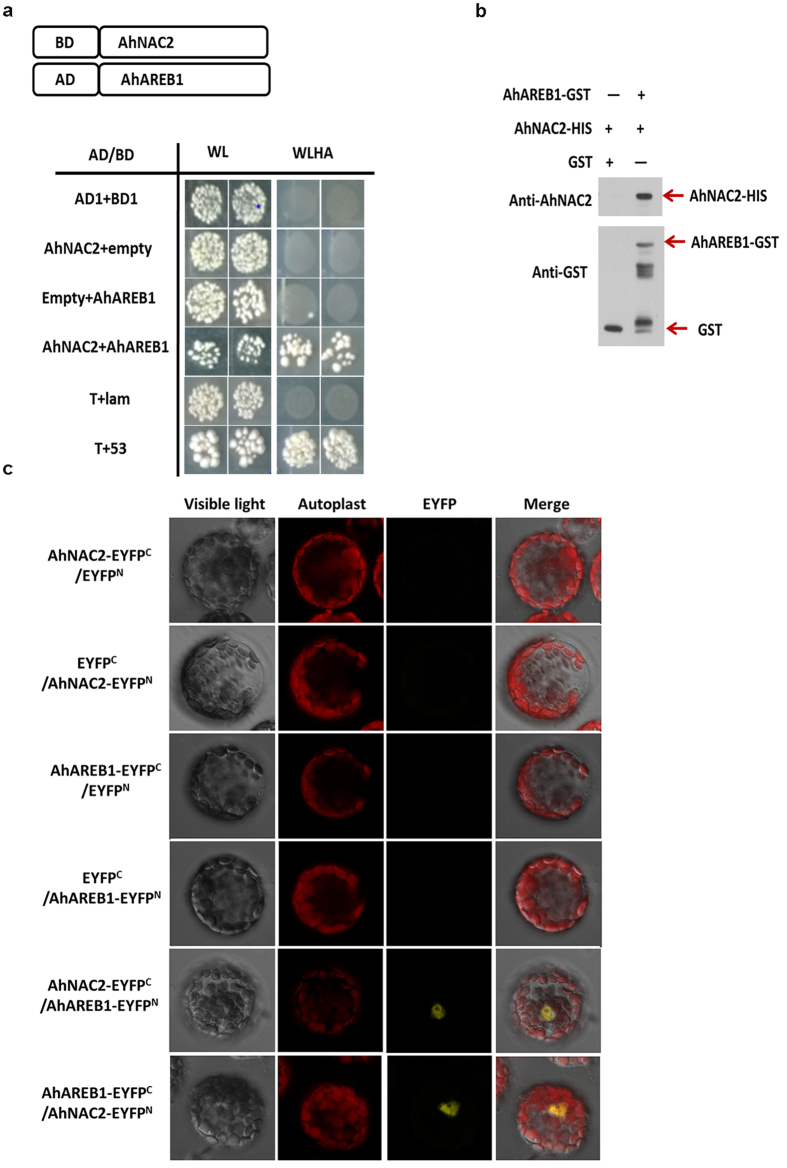

AhNAC2 physically interacts with AhAREB1

To investigate whether AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 physically bind to each other, yeast two-hybrid assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 1a, negative control combinations, such as AD/BD, AD-AhNAC2/BD, AD/BD-AhAREB1 and T/lam, did not interact, while co-expression of AD-AhNAC2 and BD-AhAREB1 showed strong interaction, as indicated by growth on SD W-L-H-A selective plates. In vitro pull-down assays, using His-AhNAC2 and GST-AhAREB1 fusion proteins, were performed to verify the interaction of AhNAC2 and AhAREB1, with GST protein alone acting as a negative control. These experiments showed that His-AhNAC2 binds to GST-AhAREB1, but not GST (Fig. 1b). To further confirm the interaction between AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 in vivo, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) was performed in A. thaliana protoplasts. A strong YFP fluorescence signal was observed when AhAREB1-EYFPC and AhNAC2-EYFPN or AhNAC2-EYFPC and AhAREB1-EYFPN were co-expressed in the same cells, while negative combinations, such as AhNAC2-EYFPC/EYFPN, EYFPC/AhNAC2-EYFPN, AhAREB1-EYFPC/EYFPN and EYFPC/AhAREB1-EYFPN, gave only background fluorescence (Fig. 1c). In all, these results indicate that AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 form a protein complex and thus might act together to regulate target genes.

Figure 1. AhNAC2 physically interacts with AhAREB1.

(a) The interaction of AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 was confirmed by yeast two-hybrid assays. Bait (AhAREB1) and prey (AhNAC2) were co-introduced by transformation into yeast strain AH109. The binding of the two TFs was confirmed by transferring the AH109 strain onto -Trp-Leu-His-Ade plus 5 mM 3-amino-1, 2, 4-triazole medium. WL: SD/-Trp/-Leu; WLHA: SD/-Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade. (b) The physical interaction of AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 was confirmed by pull-down assays. Equal amounts of either GST or GST-AhAREB1 proteins were incubated with glutathione beads and then His-AhNAC2 protein was added for 4 h. After washing, samples were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and identified by anti-AhNAC2 antibody. (c) AhNAC2 interacts with AhAREB1 in Arabidopsis protoplasts. AhAREB1 or AhNAC2 alone (AhNAC2-EYFPC/EYFPN, EYFPC/AhNAC2-EYFPN, AhAREB1-EYFPC/EYFPN and EYFPC/AhAREB1-EYFPN) were used as controls.

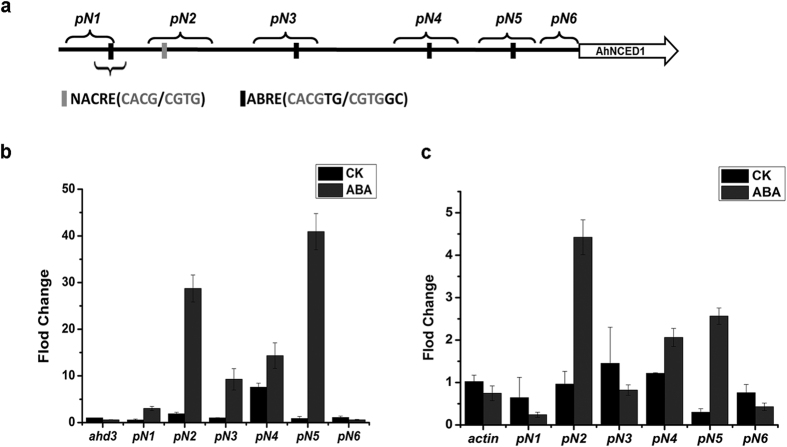

AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 directly target the AhNCED1 promoter region following ABA treatment

AhNCED1 contains one NACRE and four ABRE core sequences in the −1500 to −300 bp region of its promoter (Fig. 2a). To examine whether AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 execute their function by binding to the AhNCED1 promoter, a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed in peanut. We designed five pairs (pN1-pN6) of primers that correspond to regions within the AhNCED1 promoter and used PCR fragments generated from these in ChIP-qPCR assays. The results showed that, in the absence of ABA, AhAREB1 protein binding was enriched in the pN4 region of the AhNCED1 promoter, while AhNAC2 was not (Fig. 2b,c). However, both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 associated with the pN2, pN4, pN5 regions of the AhNCED1 promoter in response to ABA (Fig. 2b,c). In the pN1 region, which contains the most distal ABRE core sequence, only AhAREB1 was enriched in response to ABA (Fig. 2b,c). These results suggest that AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 might regulate AhNCED1 expression by binding to specific cis-acting elements in its promoter in response to ABA.

Figure 2. ABA promotes the binding of AhAREB1 or AhNAC2 protein with an AhNCED1 gene promoter DNA fragment.

(a) The positions of NACRE and ABRE elements in the AhNCE1 promoter and the regions examined by ChIP. (b) and (c) ChIP-qPCR analysis was performed to measure the relative levels of AhAREB1 (b) and AhNAC2 (c) binding to the AhNCED1 promoter in response to ABA (100 μM). AHD3 was used as the control gene to measure the DNA fragment enrichment by anti-AhAREB1 antibody, while ACTIN was used for the anti-AhNAC2 antibody.

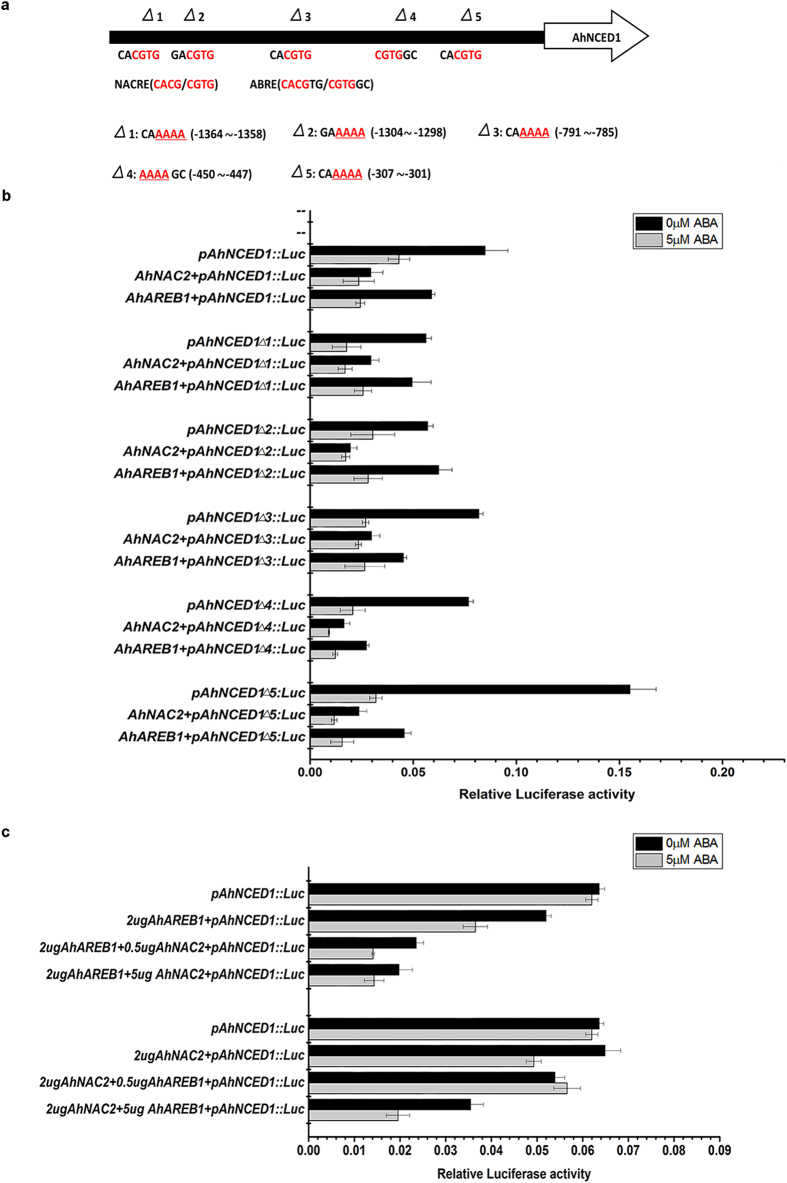

AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 co-regulate AhNCED1 expression by feedback inhibition in response to ABA

To test whether AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 regulate the expression of AhNCED1 by binding to the ABRE or NACRE cis-acting elements in its promoter, we co-expressed AhAREB1 or AhNAC2, and either pAhNCED1-Luc or pAhNCED1Δ-Luc (the latter has a mutation in the NACRE or ABRE motifs, where CACG/CGTG is changed to AAAA, in the AhNCED1 promoter; Fig. 3a) vectors in wild-type Arabidopsis protoplasts. As expected, the addition of AhNAC2 or AhAREB1 significantly down-regulated the expression of pAhNCED1-Luc, and ABA treatment enhanced this inhibition (Fig. 3b). When AhNAC2 and pAhNCED1Δ-Luc constructs were co-transfected into protoplasts, none of the individual mutations in the AhNCED1 promoter influenced AhNAC2 inhibition of pAhNCED1Δ-Luc expression (Fig. 3b). However, when we transfected the AhAREB1 construct together with pAhNCED1Δ1-Luc or pAhNCED1Δ2-Luc into protoplasts, the inhibition by AhAREB1 alone was dramatically reduced. This suggests that AhAREB1 negatively regulates AhNCED1 transcription by binding to the ABRE element located at −1367 bp or to the NACRE motif located at −1308 bp in the AhNCED1 promoter (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. Effect of AhNAC2 or AhAREB1 on pAhNCED1::LUC activity during ABA treatment.

(a) Schematic of NACRE and ABRE mutations. The triangle represents mutation of the core element. The core sequences of the NACRE and ABRE elements were mutated to AAAA. (b) LUC activity was measured by transient expression of pAhNCED1::LUC and p35S::AhNAC2 or p35S::AhAREB1 vectors in Arabidopsis protoplasts. A 5 μg quantity of purified vector was used per transfection. Protoplasts were incubated overnight in W5 buffer. After transfection, protoplasts were incubated overnight. (c) Coordinate regulation of pAhNCED1::LUC activity by co-expression of AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 with and without ABA treatment. Error bars indicate SEM (n = 3).

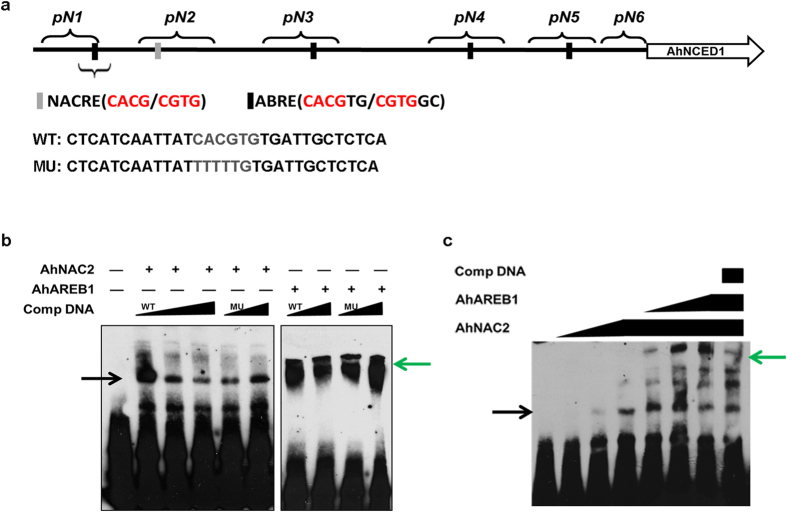

To further examine whether AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 coordinately regulate AhNCED1 transcription, AhAREB1, AhNAC2 and pAhNCED1-Luc vectors were co-transfected into Arabidopsis protoplasts. We fixed the plasmid concentration of one TF, and gradually increased the concentration of the other one to identify its function in coordinate regulation. The results showed that when 2 μg AhAREB1, 0.5 μg AhNAC2 and pAhNCED1-Luc vectors were co-transfected, Luc activity decreased to 37% of the control. When 2 μg AhNAC2, 0.5 μg AhAREB1 and pAhNCED1-Luc vectors were used, Luc activity decreased to 84.8% of controls. Importantly, even when the amount of AhAREB1 vector transfected was increased to 5 μg, Luc activity was reduced to 55.8%, meaning that the negative regulation of AhNCED1 depends on the amount of AhAREB1 protein present. In brief, the relative luciferase activities were much lower when treated with both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 (Fig. 3c). The inhibition of AhNCED1 promoter activity by AhNAC2 or AhAREB1 was enhanced by ABA treatment (Fig. 3c). In addition, to examine whether AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 bind directly to the core ABRE sequence, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) using recombinant GST-AhAREB1 and His-AhNAC2 proteins and a biotinylated probe containing the ABRE cis-acting element from the −1367 locus of the AhNCED1 promoter (Fig. 2a). A nonlabeled probe with mutated ABRE was also used as cold competitor (Fig. 2a). Both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 were able to bind to the ABRE cis-acting element (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, the binding of AhNAC2 to the ABRE motif could be reduced by adding AhAREB1 protein into the reaction (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4. EMSA of AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 protein binding to the core NACRE element in the AhNCED1 promoter.

(a) Schematic of the position of the probes in the AhNCED1 promoter. A 30 bp DNA fragment containing CACGTG was designed. WT: probe containing CACGTG; MU: probe changing CACG to AAAA. (b) Both AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 can bind to the same NACRE element. (c) Sequential addition of the two TFs into the reaction system. The black arrow indicates binding of AhNAC2 and the green arrow indicates binding of AhAREB1 to the promoter of AhNCED1; ‘Comp DNA’ indicates addition of competitor DNA.

Taken together, these findings strongly support the idea that AhNCED1 transcription is inhibited by an AhNAC2-AhAREB1 protein complex. AhAREB1 plays the key role in this negative feedback regulation, while AhNAC2 is subsidiary.

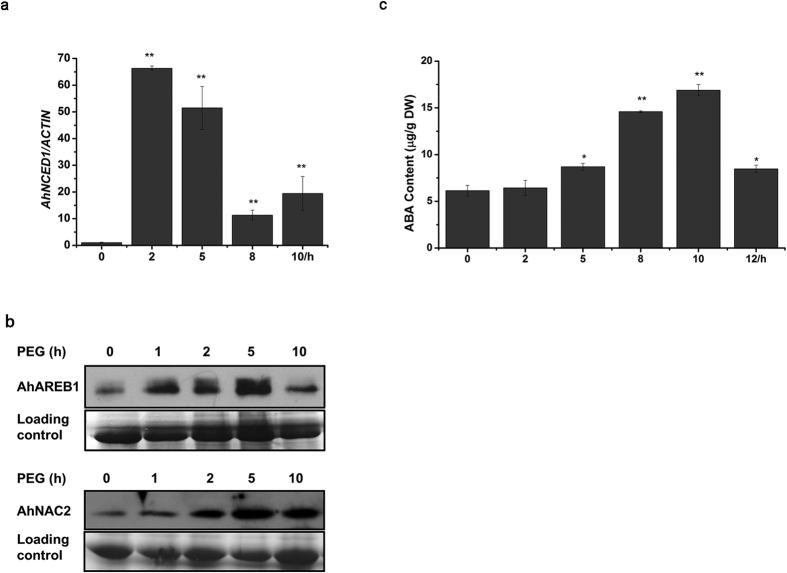

ABA plays an important role in water stress-induced feedback control of ABA biosynthesis in the leaves of peanut

To investigate the relationship between the negative feedback regulation of AhNCED1 and ABA homeostasis during water stress, quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed. A rapid 67-fold increase in the expression of AhNCED1 was observed after 2 h PEG treatment (Fig. 5a). However, perhaps more interesting is the subsequent significant downregulation of the AhNCED1 gene after 8 h PEG treatment (Fig. 5a). To determine whether AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 are involved in this down regulation, immunoblotting assays were performed to assess the respective protein levels during water stress. We found that both AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 accumulated in response to PEG treatment (Fig. 5b). An HPLC assay showed that, as expected, ABA levels increased to a maximum after 10 h PEG treatment (Fig. 5c). Together with the ChIP analysis for AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 described above (Fig. 2), which showed that ABA promotes the binding of both TFs to the AhNCED1 promoter, these results suggest that an AhAREB1/AhNAC2 protein complex is involved in the water stress-induced feedback control of AhNCED1 expression.

Figure 5. Expression of the AhNCED1 gene, accumulation of AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 proteins, and ABA content during water stress.

Peanut plants were treated with 20% PEG 6000. (a) Quantitative assessment of AhNCED1 gene expression by qRT-PCR. (b) AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 protein levels were measured by immunoblotting using anti-AhAREB1 and anti-AhNAC2 antibodies. (c) The ABA content was determined by HPLC.

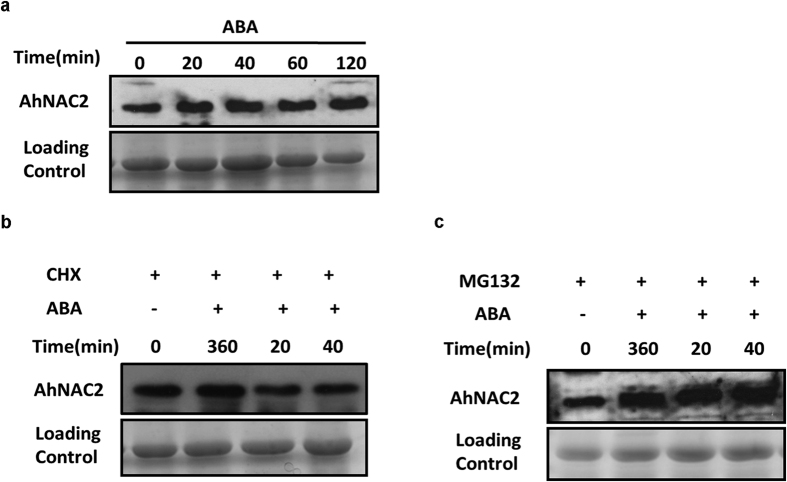

ABA influences the accumulation of both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1

To further confirm the role of ABA in this feedback regulation, we investigated the accumulation of AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 proteins in response to ABA. Both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 genes are induced by ABA, but the protein expression pattern of the respective TFs is still unknown26,27. The AhNAC2 mRNA level increased 3.5 times after 2 h ABA treatment (Supplementary Figure S1). However, the overall AhNAC2 protein levels remained stable, despite ABA treatment (Fig. 6a). Intriguingly, when peanut seedlings were pretreated with CHX (cycloheximide) for 6 h to inhibit translation, AhNAC2 protein content was rapidly reduced in the presence of ABA (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6. AhNAC2 protein is rapidly degraded in response to ABA in peanut. Immunoblotting of AhNAC2 protein levels in ten-day-old seedlings.

(a) Ten-day-old seedlings were treated with 100 μM ABA and harvested at the indicated times. (b) and (c) Ten-day-old seedlings were treated with 100 μM CHX or MG132, respectively, for 6 h and then treated with 100 μM ABA and harvested at the indicated times.

The proteasome provides the major proteolytic activity in plants, and MG132 inhibits this activity. MG132 pretreatment for 6 h stabilized AhNAC2 protein content during ABA treatment, suggesting that AhNAC2 is degraded via the proteasome (Fig. 6c). To verify this, we transferred a p35S::AhNAC2-GFP construct into Arabidopsis (the 35 S promoter does not respond to ABA treatment)30. Almost all AhNAC2-GFP protein was degraded after 3 h ABA treatment, while MG132 pretreatment prevented this (Supplementary Figure S2a). In contrast, when p35S::AhAREB1-GFP was transformed into Arabidopsis, AhAREB1 protein clearly accumulated in the presence of ABA, suggesting that ABA inhibits AhAREB1 breakdown (Supplementary Figure S2b).

In summary, these results demonstrate that ABA enhances both the synthesis and degradation rates of AhNAC2, but reduces the AhAREB1 degradation rate.

Discussion

The key regulatory step in ABA biosynthesis is catalyzed by NCED, which cleaves 9-cis-epoxycarotenoids to xanthoxin5,6,31. In peanut, like in other plants, ABA content is markedly enhanced during water stress, in parallel with a significant increase in AhNCED1 protein levels; AhNCED1 has been identified as the key enzyme in ABA biosynthesis under water stress32. Previous studies demonstrated that the NCED gene can be induced by exogenous ABA25,33. DREB2C, ATHB and ATAF1 TFs are known to be activators of NCED transcription, but the negative regulation of NCED is still unclear12,34,35. However, ABA is likely to be involved, probably as part of a negative feedback mechanism, because such regulation by the product (s) of a biosynthetic pathway is ubiquitous in plants. For example, bioactive gibberellin (GA), involved in stem elongation, seed germination and root elongation, provides feedback regulation of GA 2-oxidase biosynthesis genes36,37. Here, we identified two TFs, AhAREB1 and AhNAC2, which form a protein complex in peanut to mediate ABA-dependent negative feedback regulation of AhNCED1 transcription (Figs 1 and 3). AhAREB1 plays a central role in this process, while AhNAC2 functions as an enhancer (Fig. 3). What is noteworthy is that ABA increases the inhibitory effect of AhNAC2 or AhAREB1 on AhNCED1 promoter activity (Fig. 3), and affects the accumulation of both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 TFs (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figure S2). ABA achieves this by enhancing both the synthesis and degradation rate of AhNAC2 to maintain stable protein levels, while levels of AhAREB1 are increased by reducing its degradation rate (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figure S2).

The relationship between NAC and AREB TFs, which has mostly been researched in Arabidopsis, is complex. The expression of three Arabidopsis NAC TFs, ANAC072, ANAC019 and ANAC055, is induced in response to ABA, and a yeast one-hybrid assay revealed that key AREBs (ABF3, ABF4) bind to the promoters of all three of the corresponding genes via the ABRE core cis-acting element, which occurs several times within each NAC promoter10,38. NAC016 is also involved in drought stress responses: overexpression of NAC016 results in low drought tolerance, while nac016 mutants have high drought tolerance, suggesting that NAC016 works as a negative regulatory factor in drought stress. Furthermore, both NAC016 and the product of its target gene NAC-like, activated by AP3/PI (NAP) directly bind to the promoter of AREB1 and repress its transcription16. AREB1 encodes a TF with a central role in the stress-responsive ABA signaling pathway.

A previous study suggested that ABA affects ABF1 and ABF3 protein accumulation by post-translational regulation, while ABA can suppress the interaction between the ubiquitin E3 ligase KEEP ON GOING (KEG) and ABFs to slow their proteolysis39,40. Levels of NAC1, an Arabidopsis NAC TF with a role in the auxin signaling pathway, can be increased by treatment with MG132, indicating that NAC1 may be regulated by a post-translational mechanism41. Our results are consistent with the conclusion that AhAREB1 is the key negative regulator of AhNCED1 expression, while AhNAC2 is simply an enhancer of this inhibitory effect. Furthermore, both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 can improve the drought tolerance of the plant by inducing stress-related gene expression27,28, meaning that both TFs are activators of the ABA signaling pathway.

The negative feedback regulation of ABA biosynthesis in peanut, mediated by AhAREB1, contrasts with the situation in Arabidopsis, where a positive feedback mechanism of ABA biosynthesis regulation has been reported, with the cis-acting element ABRE playing a critical role24. In tomato, similarly to peanut, a negative feedback mechanism has been found42. Thus, water stress causes a rapid increase in endogenous ABA in WT tomato leaves, such that high levels are attained after 6 h, which continue to increase through until 24 h of the treatment. At the same time, the expression of NCED1 reaches a maximum at 6 h after imposition of the stress and then reduces until the 24 h time point. Similar observations were made in tomato root42. Bioinformatics analysis of the 2000-bp upstream region of NCED1 (GenBank Accession no. SGN-U577478) in tomato showed that it contains two cis-acting ABRE elements and three cis-acting NACRE core elements (Supplementary Figure S3). This might indicate that the negative feedback regulatory mechanism of ABA biosynthesis we observed in peanut is a more general phenomenon in plants, even though it has not yet been found in Arabidopsis. The regulation of ABA biosynthesis is likely to be complex, however, involving both positive and negative mechanisms. In this regard, we note that, although AhAREB1 acts on the AhNCED1 promoter as a negative transcription factor in response to ABA treatment (Fig. 2), only the cis-acting elements in the pN1 and pN2 regions are involved in this negative regulation. We predict that cis-acting elements in other regions of the AhNCED1 promoter might feature in other forms of regulation of AhNCED1 transcription.

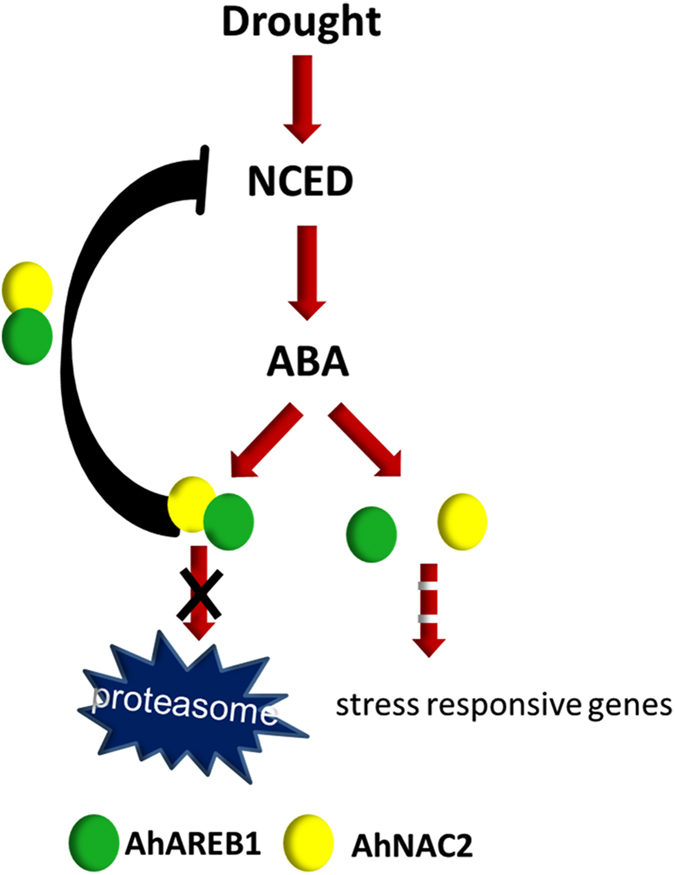

The results described in this paper are all consistent with the following description of events. After 2 h PEG treatment in peanut, the expression level of the AhNCED1 gene reaches a peak. The level of AhNAC2/AhAREB1 protein complex increases as both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 proteins accumulate, leading to partial inhibition of AhNCED1 expression. ABA improves both the synthesis and degradation rate of AhNAC2 protein and slows AhAREB1 protein degradation so that the latter accumulates within cells. AhAREB1 plays the key role in the feedback regulation of AhNCED1 transcription, while AhNAC2 is an enhancer of this process. Both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 are activators in the response to water stress and induce the expression of stress-responsive genes (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Model of the dual role of the AhAREB1/AhNAC2 protein complex in peanut. Drought induces AhNCED1 expression and ABA levels increase.

Levels of the AhNAC2/AhAREB1 protein complex also increase as both AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 accumulate. The protein complex binds to the AhNCED1 promoter to partially inhibit its transcription and maintain ABA homeostasis. The two TFs also activate the ABA signal pathway by upregulating downstream genes.

Materials and Methods

Plant growth and treatments

Seeds of peanut (Arachis hypogaea) were sown and grown as described43. Yueyou 7 is a line provided by the Crop Research Institute, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China. PEG 6000 (w/v) was used to simulate the effect of drought stress43. For ABA, cycloheximide (CHX) or MG132 treatments, four-leaf-stage (10–12 days after sowing) plants were carefully removed from the soil mixture and then grown hydroponically. ABA, CHX and MG132 were applied by uniformly spraying onto leaf surfaces at a concentration of 100 μM39. Peanut leaf samples (100 mg) were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately following the treatments and stored at −70 °C until further use.

Yeast two-hybrid assays

Yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assays were performed as previously described43. AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 cDNAs were transferred into the plasmids pGADT7 and pGBKT7, respectively. Yeast AH109 was cotransformed with special-purpose vectors (pGADT7, pGBKT7, pGADT7-AhNAC2/AhAREB1, pGBKT7-AhNAC2/AhAREB1). To avoid self-activation, yeast was treated with 5 mM 3-amino-1, 2, 4-triazole (3-AT; Wako) for Y2H screening.

Pull-down assays

Full-length AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 cDNAs were cloned into pGEX-4T-1 (Pharmacia) and pPROEX-HTa vectors to allow production of GST-AhAREB1 and His-AhNAC2 fusion proteins after induction by isopropyl-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Expression of GST-AhAREB1 was induced in Escherichia coli BL21-Codon Plus-RP (Agilent Technologies) by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 0.5 mM at 30 °C for 4 h, after which the bacteria were transferred to 25 °C overnight. His-AhNAC2 was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Amersham Biosciences) by adding 0.5 mM IPTG at 37 °C for 4 h. GST pull-down assays were performed as described41. Glutathione Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) or Ni-NTA agarose beads (Millipore) were used to purify fusion proteins. Two μg His-AhNAC2 protein was incubated with immobilized GST or GST-AhAREB1 in binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA) at 4 °C overnight. Proteins retained on beads were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected with anti-GST (Millipore) or anti-His antibody (Sigma), as appropriate, by immunoblotting (see below).

BiFC experiments

For BiFC experiment assays, full-length AhAREB1 and AhNAC2 cDNAs were cloned into the pGreen binary vector HY105 containing C- or N-terminal fusions of EYFP to generate 35 S:AhAREB1-EYFPC and 35 S:AhNAC2-EYFPN, respectively, which were then cotransformed into Arabidopsis protoplasts as previously described4. AhNAC2-EYFPC/EYFPN, EYFPC/AhNAC2-EYFPN, AhAREB1-EYFPC/EYFPN and EYFPC/AhAREB1-EYFPN worked as negative control. YFP fluorescence signals were observed after 12–20 h incubation under a fluorescence microscope (Leica). All figures show representative images from three independent experiments.

Antibody preparation, protein extraction and immunoblotting

The AhAREB1 coding sequence was cloned in the pPROEX-HTa vector and the resulting fusion protein His-AhAREB1 was induced under the same conditions as GST-AhAREB1. His-AhAREB1 and His-AhNAC2 proteins were purified and used for antibody production (polyclonal, rabbit). Antibody specificity was tested using the respective purified recombinant protein and also total protein from peanut leaves. Protein was extracted from peanut leaves (100 mg) by grinding leaves in liquid nitrogen and 1 mL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.2, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche), 100 mM PMSF (Sigma)). Anti-GFP (abcam, ab290) was also used to test the accumulation of AhAREB1-GFP and AhNAC2-GFP fusion proteins in transgenic Arabidopsis.

Chromatin coimmunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

For the ChIP assay, leaves of four-leaf-stage (10–12 days after planting) peanuts (500 mg) were fixed with cold MC buffer (10 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 M sucrose, 1% formaldehyde) for 20 min by vacuum concentration. Nucleoproteins were isolated by the method published by Su42 and sonicated to produce DNA fragments on the order of 300 bp. Five μg anti-AhNAC2, anti-AhAREB1 and rabbit IgG (Millipore) were used for immunoprecipitation and antibody complexes were recovered by Protein G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Specifically precipitated DNA was recovered and analyzed by real-time PCR with SYBR Premix ExTaq Mix (Takara Bio). The peanut genes ACTIN and AHD3 (Genbank: DQ873525.1 and EE127230.1, respectively) were used to calculate the relative fold-enrichment of target DNA fragments. The primers used to measure the binding of the TFs to the AhNCED1 promoter are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA was extracted as described by Wan and Li25. Reverse transcription was carried out using PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (Takara). SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Tli RNaseH Plus) (Takara) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions with an ABI PRISM 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, UK). Primers for qRT-PCR are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Purified His-AhNAC2 and GST-AhAREB1 recombinant proteins were used for protein-DNA binding. The EMSA assay was performed using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce). A 30 bp DNA fragment containing CACGTG in the upstream of P1 region in the AhNCED1 promoter was used as probe. Nonlabeled probe contain the native core-sequence (CACGTG) or mutated core-sequence (TTTTTG) was used as cold competitor.

LUC complementation assay

The AhNCED1 promoter was amplified and cloned into the pGreenII 0800-LUC vector, while AhNAC2 and AhAREB1 cDNAs were cloned into pGreenII 62-SK, the effector vector in the LUC complementation assay. LUC luminescence of live protoplasts was measured as previously described; 5 mM ABA was added44,45.

Determination of ABA content

Leaves (0.5 g) were collected, frozen in liquid nitrogen and then ground with 8 ml methanol:glacial acetic acid (80:20), as described by Yue46. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used, with an ABA standard (Sigma) diluted to 10 mM, 1 mM, 100 nM and 10 nM as needed. ABA contents were measured in triplicate for each sample.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, S. et al. Negative feedback regulation of ABA biosynthesis in peanut (Arachis hypogaea): a transcription factor complex inhibits AhNCED1 expression during water stress. Sci. Rep. 6, 37943; doi: 10.1038/srep37943 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30971715 granted to LL). We thank Xuanqiang Liang fellows of the Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences for providing peanut seeds. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.L. and L.L. designed the experiments. L.C.S. performed the western blot. M.J.L. performed the Y2, BiFC and Pull-Down. L.C.S. performed the Luc and ChIP-qPCR assay. K.G. and L.M.L. performed the qPCR and the determination of ABA content. X.Y.L and X.L analyzed the data. L.M.L. provided reagents/materials/analysis tools.

References

- Bartels D. & Sunkar R. Drought and salt tolerance in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 24, 23–58 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. & Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory networks in cellular responses and tolerance to dehydration and cold stresses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 781–803 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuchi S. et al. Regulation of drought tolerance by gene manipulation of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase, a key enzyme in abscisic acid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 27, 325–333 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. et al. Cloning and expression analysis of cDNAs encoding ABA 8′-Hydroxylase in peanut plants in response to osmotic stress. PLoS ONE. 9(5), e97025 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S. H., Tan B. C., Gage D. A., Zeevaart J. & McCarty D. Specific oxidative cleavage of carotenoids by VP14 of maize. Science. 276, 1872–1874 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B. C., Schwartz S.-H., Zeevaart J. & McCarty D.-R. Genetic control of abscisic acid biosynthesis in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 12235–12240 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo A. et al. Drought induction of Arabidopsis 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase occurs in vascular parenchyma cells. Plant Physiol. 147, 1984–1993 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. W., Yang H. Q., You S. Z. & Ran K. MhNCED3 in Malus hupehensis Rehd. Induces NO generation under osmotic stress by regulating ABA accumulation. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 96, 254–260 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann J. L. et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 290, 2105–2110 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran L. S. et al. Isolation and functional analysis of Arabidopsis stress-inducible NAC transcription factors that bind to a drought-responsive cis-element in the early responsive to dehydration stress 1 promoter. Plant Cell. 16, 2481–2498 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. et al. Dual function of Arabidopsis ATAF1 in abiotic and biotic stress responses. Cell Res. 19, 1279–1290 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M. K. et al. ATAF1 transcription factor directly regulates abscisic acid biosynthetic gene NCED3 in Arabidopsis thaliana. PPES Open Bio. 3, 321–327 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q. J. et al. TaNAC29, a NAC transcription factor from wheat, enhances salt and drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biology. 15, 268–283 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M. et al. A dehydration-induced NAC protein, RD26, is involved in a novel ABA-dependent stress-signaling pathway. Plant J. 39, 863–876 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Q. Y. et al. Role of the Arabidopsis thaliana NAC transcription factors ANAC019 and ANAC055 in regulating jasmonic acid-signaled defense responses. Cell Res. 18, 756–767 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuraba Y., Kim Y. S., Han S. H., Lee B. D. & Peak N. C. The Arabidopsis Transcription Factor NAC016 Promotes Drought Stress Responses by Repressing AREB1 Transcription through a Trifurcate Feed-Forward Regulatory Loop Involving NAP. The Plant Cell. 27(6), 1771–87 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T. et al. Four Arabidopsis AREB/ABF transcription factors function predominantly in gene expression downstream of SnRK2 kinases in abscisic acid signaling in response to osmotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 38, 35–49 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y., Fujita M., Shinozaki K. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. ABA-mediated transcriptional regulation in response to osmotic stress in plants. J. Plant Res. 124, 509–525 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. Y., Choi H. I., Im M. Y. & Kim S. Y. Arabidopsis basic leucine zipper proteins that mediate stress-responsive abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 14, 343–357 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y. et al. AREB1 is a transcription activator of novel ABRE-dependent ABA signaling that enhances drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell, 17, 3470–3488 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busk P.-K. & Pages M. Regulation of abscisic acid-induced transcription. Plant Mol. Biol. 37, 425–435 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q., Zhang P. & Ho T.-H. D. Modular nature of abscisic acid (ABA) response complexes: Composite promoter units that are necessary and sufficient for ABA induction of gene expression in barley. Plant Cell. 8, 1107–1119 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrero J. M. et al. Both abscisic acid (ABA)-dependent and ABA-independent pathways govern the induction of NCED3, AAO3 and ABA1 in response to salt stress. Plant Cell Environ. 29, 2000–2008 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. Z. & Tan B. C. A distal ABA responsive element in AtNCED3 promoter is required for positive feedback regulation of ABA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE, 9, e87283 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan X. & Li L. Molecular cloning and characterization of a dehydration- inducible cDNA encoding a putative 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase in Arachis hypogaea L. DNA. 16, 217–223 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L. et al. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of a new stress-related AREB gene from Arachis hypogaea. Biologia Plantarum. 1(57), 56–62 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. et al. Improved drought and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis overexpressing a NAC transcriptional factor from Arachis hypogaea. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 75(3), 443–50 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Y. et al. Overexpression of Arachis hypogaea AREB1 gene enhances drought tolerance by modulating ROS scavenging and maintaining endogenous ABA content. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 12827–12842 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J. et al. Cloning and characterization of the promoter of the 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene in Arachis hypogaea L. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 73, 2103–2106 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-T., Liu H.-X., Stone S. & Callis J. ABA and the ubiquitin E3 Ligase KEEP ON GOING affect proteolysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factor ABF1 and ABF3. The Plant J. 75, 966–976 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre V. et al. Functional analysis of Arabidopsis NCED6 and NCED9 genes indicates that ABA synthesized in the endosperm is involved in the induction of seed dormancy. Plant J. 45, 309–319 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B. et al. The higher expression and distribution of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase1 (AhNCED1) from Arachis hyopgaea L. contribute to tolerance to water stress in a drought-tolerant cultivar. Acta. Physiologiae Plantarum. 35, 1667–1674 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H., Lee, Ishitani M. & Zhu J. K. Regulation of osmotic stress responsive gene expression by the LOS6/ABA1 locus in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8588–8596 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Je J. Y., Chen H., Song C. & Lim C. O. Ahabidopsis DREB2C modulates ABA biosynthesis during germination. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 452(1), 91–98 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo M., Kanno Y., Frey A., North H.-M. & Marion-Poll A. Dissection of Arabidopsis NCED9 promoter regulatory regions reveals a role for ABA synthesized in embryos in the regulation of GA-dependent seed germination. Plant Science. 246, 91–97 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P. & Phillips A. L. Gibberellin metabolism: new insights revealed by the genes. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 523–530 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski N., Sun T. P. & Gubler F. Gibberellin signaling: biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. Plant Cell. 14, 61–80 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman R. et al. A local regulatory network around three NAC transcription factors in stress responses and senescence in Arabidopsis leaves. The Plant J. 75, 26–39 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. T., Liu H. X., Stone S. & Callis J. ABA and the ubiquitin E3 Ligase KEEP ON GOING affect proteolysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana transcription factor ABF1 and ABF3. The Plant J. 75, 966–976 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. SDIR1 is a RING finger E3 ligase that positively regulates stress-responsive abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 19, 1912–1929 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q. et al. SINAT5 promotes ubiquitin-related degradation of NAC1 to attenuate auxin signals. Nature. 419, 167–170 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Espinoza V. A. et al. Water Stress Responses of Tomato Mutants Impaired in Hormone Biosynthesis Reveal Abscisic Acid, Jasmonic Acid and Salicylic Acid Interactions. Frontiers in Plant Science, 6, 997 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L. C. et al. Isolation and characterization of an osmotic stress and ABA induced histone deacetylase in Arachis hygogaea. Fontiers in Plant Science. 6, 512–523 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellens P. R. et al. Transient expression vectors for functional genomics, quantification of promoter activity and RNA silencing in plants. Plant Methods. 1, 1–13 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. et al. The unique mode of action of a divergent member of the ABA-receptor protein family in ABA and stress signaling. Cell Res. 23(12), 1380–95 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y. S. et al. Over expression of the AtLOS5 gene increased abscisic acid level and drought tolerance in transgenic cotton. J. Exp. Bot. 63(2), 695–709 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.