Abstract

Objectives

Examine relationships of periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS) and incident atrial fibrillation/flutter (AF).

Methods

Prospective multicenter cohort (n=2,273: adjudicated AF group, n=843: self-reported AF group) of community-dwelling men without prevalent AF were followed an average of 8.3yr (adjudicated) and 6.5yr (self-reported). PLMS index (PLMI, <5 (ref), ≥5 to <30, ≥30) and PLM arousal index (PLMAI, <1 (ref), ≥1 to <5, ≥5) were measured by polysomnography. Incident adjudicated and self-reported AF were analyzed via Cox proportional hazards or logistic regression, respectively, and adjusted for age, clinic, race, body mass index, alcohol use, cholesterol level, cardiac medications, pacemaker, apnea-hypopnea index, renal function, and cardiac risk. The interaction of age and PLMS was examined.

Results

In this primarily Caucasian (89.8%) cohort of older men (mean age 76.1±5.5 years) with BMI of 27.2±3.7, there were 261 cases (11.5%) of adjudicated and 85 cases (10.1%) of self-reported incident AF. In the overall cohort, PLMI and PLMAI were not associated with adjudicated or self-reported AF. There was some evidence of an interaction of age and PLMI (p=0.08, adjudicated AF) and PLMAI (p≤0.06, both outcomes). Among men aged≥76, the highest PLMI tertile was at increased risk of adjudicated AF (≥30 vs. <5; HR=1.63, 1.01-2.63) and the middle PLMAI tertile predicted increased risk of both outcomes (1 to <5 vs. <1; adjudicated, HR=1.65, 1.05-2.58; self-reported HR=5.76, 1.76-18.84). No associations were found in men<76.

Conclusions

Although PLMS do not predict AF incidence in the overall cohort, findings suggest PLMS increases incident AF risk in the older subgroup.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, sleep, periodic limb movements during sleep, PLMS, PLMI

1. INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF)is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia worldwide and has notable negative effects on quality of life, healthcare costs, and even survival.[1–3] AF prevalence increases with age and is projected to more than double over the next forty years.[4] Action to mitigate established AF risk factors and identification of novel AF risk factors can lead to strategies to curb increasing rates of this disorder. Periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS) have been posited as one such risk factor. These movements are characterized by repetitive, brisk leg muscle activations during sleep that are often accompanied by arousals. Although the movements can cause arousals and sleep fragmentation, PLMS when not associated with daytime impairment are of unclear clinical importance. Previous studies have shown that limb movements are accompanied by sympathetic activation exhibited by discrete heart rate elevations.[5] This sympathetic activation is more pronounced when limb movements are associated with arousals.[6,7] In addition, several studies have shown increased heart rate variability associated with PLMS.[8–10]

Moreover, recent work has shown that PLMS portend worse cardiovascular outcomes.[11–13] Over 85% of patients with restless legs syndrome have increased PLMS.[14] In a retrospective longitudinal study which involved patients with restless legs syndrome divided into high-PLM and low-PLM burden groups, the high-PLM burden participants had significantly more left ventricular hypertrophy, a higher rate of heart failure development, and decreased survival over a 33 month follow-up.[13] A large-scale prospective longitudinal analysis of the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS) cohort found an increased risk of all cause cardiovascular and vascular disease in those with higher burden of PLMS.[11] Although data pertaining to PLMS and cardiac arrhythmia are sparse, these nocturnal movements have stronger associations with nocturnal cardiac arrhythmias in older men without reported use of atrioventricular nodal blockade medications and also in those with heart failure.[15] A growing body of research supports the role of PLMS in the provocation of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality; the sympathetic activation which likely underlies these relationships may contribute to arrhythmia generation or perpetuation.

Although prior cross sectional literature does not suggest an overall association of PLMS and cardiac arrhythmia, it does support the observation that certain subgroups such as those with cardiac disease and those not on protective cardiac medications are particularly vulnerable to arrhythmogenesis.[8] Prospective longitudinal data, however, are lacking. To characterize possible relationships we examined a large, prospective, multi-center, community-based cohort study of older adult males using both adjudicated and self-reported AF data. The adjudicated data represent AF resulting in symptomatic clinical presentation resulting in emergency department visit or hospitalization, cardiac procedure, or symptoms while the self-reported data only queries participants about past AF diagnosis and may represent both symptomatic and asymptomatic AF. We hypothesize that PLMS, particularly when occurring with arousals, are associated with increased AF incidence.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 PARTICIPANTS AND STUDY DESIGN

This prospective observational study involved participants of the Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men Study (MrOS Sleep Study), an ancillary study the MrOS study. The MrOS study enrolled 5994 community-living men aged 65 and older, able to ambulate without assistance from another person, and without history of bilateral hip replacement. Six centers (Birmingham, Alabama; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Monongahela Valley near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Palo Alto, California; Portland, Oregon; San Diego, California) recruited participants.[16,17] The MrOS study design, methods, and demographics have been previously published.[16–18] Each site and the study coordinating center received ethics approval from their institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

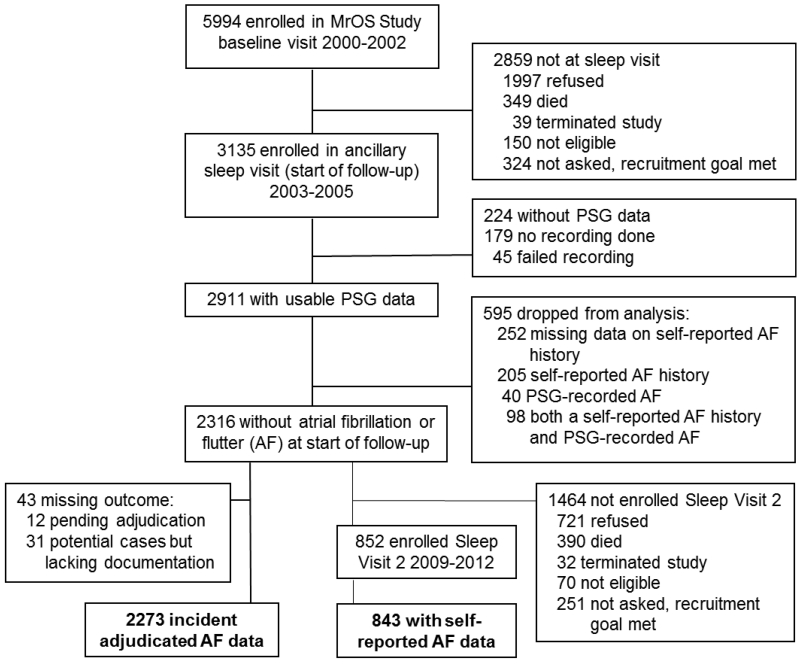

The MrOS Sleep Study recruited 3135 participants from December 2003 to March 2005 for a comprehensive sleep assessment. MrOS Sleep Study participants were screened for nightly use of mechanical devices during sleep including pressure mask for sleep apnea (continuous positive airway pressure or bilevel positive airway pressure), mouthpiece for snoring or sleep apnea, or oxygen therapy and were excluded if they could not forgo use of these devices during a polysomnography (PSG) recording. Of the 2859 men who did not participate in the MrOS Sleep Study, 349 died before the sleep visit, 39 had already terminated the study, 324 were not asked because recruitment goals had already been met, 150 were ineligible, and 1997 refused. Of the 3135 MrOS Sleep Study participants recruited, 179 did not participate in PSG secondary to refusal or contemporaneous treatment of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) and 45 men had a failed sleep study (1.5%), resulting in 2911 participants. Of these, 2316 did not have prevalent AF defined as either PSG-identified or self-reported AF at the first sleep visit. The adjudicated analysis sample consisted of 2273 men with complete data on incident adjudicated AF events (Figure 1). The self-reported AF sample was based upon a total of 1055 participants with usable PSG and actigraphy data who were assessed as part of this second sleep visit from November 2009 to March 2012 with a mean follow-up time of 6.5 ± 0.7 years (Figure 1). Of the 2316 men without prevalent AF, 852 were enrolled in this second sleep visit. Of these 852 men, 843 had data on incident self-reported AF data at this time point. There was overlap between the 843 men in the self-report group and the 2273 men in the adjudicated AF group since these samples were drawn from the same group of men, those without prevalent AF who completed the first sleep visit. Of the 840 there were n=50 with the adjudicated outcome, n=85 with the self-reported outcome. Of these, n=37 have both. Seventy four percent of those with the adjudicated AF outcome also self-reported AF. Forty four percent who self-reported AF also had the adjudicated outcome.

Figure 1.

Study flow: Recruitment, Attrition, and Retention

2.2 POLYSOMNOGRAPHY DATA

An unattended home PSG (Safiro, Compumedics, Inc.®, Melbourne, Australia) was obtained. The PSG recordings were to be collected within one month of the clinic visit (mean 6.9 ± 15.8 days from visit), with 78% of recordings were made within one week of the clinic visit. The recording montage consisted of C3/A2 and C4/A1 electroencephalograms, bilateral electrooculograms, a bipolar submental electromyogram, thoracic and abdominal respiratory inductance plethysmography, airflow, finger pulse oximetry, lead I EKG (250Hz), body position, and bilateral anterior tibialis piezoelectric movement sensors. Signal quality grade data was collected for each leg defined by percentage of sleep time with acceptable PLM signal. In our analytic sample, 90% of men had an acceptable signal on one or both legs for over 95% of sleep time, and 85% of men had an acceptable signal for both legs for over 95% of sleep time. Staff who performed home visits were centrally trained and used standardized protocols similar to those in the SHHS.[19,20] Scoring was performed by certified research polysomnologists. Arousals were scored according to American Sleep Disorders Association criteria.[21]

Apnea was defined as complete or near complete cessation of airflow for 10 or more seconds.[22] Hypopneas were scored if clear reductions in breathing amplitude (at least 30% below baseline breathing) occurred, and lasted 10 or more seconds with a drop in arterial saturation of 3% or more.[22] Severity of SDB was determined by the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) which was calculated as the total number of apneas and hypopneas associated with a ≥3% oxygen desaturation per hour of sleep.[23]

Leg movements were scored if there was an amplitude increase from baseline lasting 0.5 - 5.0 seconds; PLMS required 4 or more movements in succession 5-90 seconds apart. Leg movements after respiratory events were not included unless they were part of a four or more movement cluster with two or more leg movements occurring independent of respiratory events. PLMS were quantitated using the periodic limb movement index (PLMI) – PLMS per hour sleep – and the periodic limb movements of sleep associated with arousal index (PLMAI) – number of PLMS associated with arousals within 3 seconds of movement termination per hour of sleep.[24] In-laboratory validation of piezoelectric leg sensors and scoring rules used in this study compared to leg electromyography and 2013 American Academy of Sleep Medicine scoring rules on 51 subjects showed a correlation of r=0.81 for PLMI.[24,25]

2.3 OUTCOME MEASURES

AF was characterized in two ways: as adjudicated incident AF events with symptomatic presentation (hereby referred to as “adjudicated”) and incident participant self-reported AF (hereon referred to as “self-reported”) which could encompass either symptomatic or asymptomatic presentation.

2.3.1 Adjudicated Atrial Fibrillation

Adjudicated clinically-symptomatic AF was defined by emergency department visit or hospitalization, procedure, or symptoms. Duration of follow-up for the adjudicated AF was an average 8.3 ± 2.3 years. Possible adjudicated AF events were identified by surveying participants for incident cardiovascular events by postcard and/or phone every four months (>99% response rate). Participants were asked if they had visited the emergency department or been admitted to the hospital in the last 4 months, and if so, if the visit was due to cardiovascular causes. Medical records and supporting documentation from potential incident events were centrally adjudicated by a board-certified cardiologist using a pre-specified adjudication protocol. Specific documentation was required for adjudication of arrhythmias which were divided into subtypes. The following symptoms of arrhythmia were considered in adjudication: fatigue, palpitations, lightheadedness, pre-syncope, syncope, chest pain, or dyspnea. Documentation required for adjudicated AF event included one or more of the following: emergency medical services notes and/or rhythm strips, electrocardiography (including stress testing), in-hospital telemetry, ambulatory electrocardiography (Holter monitor and/or event monitor), pacemaker or defibrillator telemetry (for those patients with a device already implanted), or invasive cardiac electrophysiology testing. Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter events specifically include the pre-excited forms of either of these tachycardias as well as any cardioversion procedures to restore normal sinus rhythm.

2.3.2 Self-reported Atrial Fibrillation

Self-reported incident AF was assessed via questionnaire by asking participants of the MrOS Sleep Study both at the baseline visit and the follow-up second sleep visit (6.5 ± 0.7 years after baseline) “Have you ever been diagnosed with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter?”

2.4 OTHER MEASURES

All participants completed questionnaires at the sleep visit, which included demographics, medical history, smoking status, and alcohol use questions. Participants were asked to bring in all medications used within the preceding 30 days, which were entered into an electronic database and each medication was matched to its ingredient(s) based on the Iowa Drug Information Service Drug Vocabulary (College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA).[26] Cardiovascular medications were categorized by type as calcium channel blockers, non-ophthalmic beta-blockers, cardiac glycosides, or anti-arrhythmic medications – cardiac sodium channel blockers and potassium channel blockers. Dopamine antagonists were categorized as antipsychotics, domperidone, prochlorperazine, perphenazine, chlorpromazine, metoclopramide, or tricyclic antidepressants. Physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.[27] Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was defined by history of myocardial infarction, angina, angioplasty, and/or coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated from body weight, measured with standard balance beam or digital scale calibrated with standard weights, and height, measured with a wall-mounted Harpenden stadiometer. Presence of a pacemaker was determined by PSG EKG recording examination. Cholesterol was measured during the MrOS baseline visit 3 years prior using a Roche COBAS Integra 800 automated analyzer, which was calibrated daily (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN). Total cholesterol (mg/dl) was calculated: high-density lipoprotein (mg/dl) + low-density lipoprotein (mg/dl) + 0.5*triglycerides (mg/dl). Measures of renal function were performed on previously frozen (−70°C) stored serum samples obtained at the sleep visit. Serum creatinine was analyzed using the Roche Modular P chemistry analyzer (Enzymatic/Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN). Serum cystatin-C was measured using the Roche Modular P chemistry analyzer (Turbidimetric/Gentian AS, Moss, Norway). Glomerular filtration rate was estimated (eGFR) using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology (CKD-EPI) formula using both serum creatinine and cystatin-C.[28]

2.5 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The PLMS parameters were expressed as categorical variables informed by previous studies.[15] PLMI was categorized into three groups: (i) <5 (reference), (ii) 5 to <30, and (iii) ≥30. PLMAI was also categorized into three groups: (i) <1 (reference), (ii) 1 to <5, and (iii) ≥5. Participant characteristics were summarized as mean ± SD or n (%) and compared across categories of PLMI using chi-square tests for categorical variables, t-tests or ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables, and Wilcoxon rank sum or Kruskall-Wallis tests for continuous variables with skewed distributions.

The relationship of PLMS and subsequent AF risk was assessed by Cox proportional hazards regression for adjudicated AF and logistic regression for self-reported AF. Results are presented as hazard ratios (HR) or odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Men who died or were lost to follow-up (n=676 died, n=81 terminated) were censored after date of last follow-up contact for the Cox proportional hazards models. Models are presented as unadjusted and multivariable adjusted (adjusted for age, clinic, race, BMI, alcohol use, total cholesterol, AHI, hypertension, pacemaker placement, and self-reported history of CVD, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, stroke, eGFR, and use of CVD medications). eGFR was used as a marker of renal failure, a condition associated both with increased PLMS frequency and cardiovascular risk.

As the aged heart is predisposed to AF secondary to structural and electrical remodeling, PLMS sympathetic surges may lead to a positive interaction on AF generation particularly in the older population.[29] Therefore, we examined the possible interaction of age and PLMS in secondary analyses by examining age as both a continuous and a dichotomous variable based on median age (76 years).[30] We also examined interactions of PLMS and CVD medication use and as well as separate analyses for history of congestive heart failure or cardiovascular disease since these conditions may operate synergistically with PLMS to predispose to development of AF. Interaction terms were considered significant if p<0.10. If significant interactions were present, stratified analyses were conducted (age at median, <76 yrs, ≥76 yrs, CVD medication use and history of congestive heart failure or cardiovascular disease as yes/no). Sensitivity analyses excluding men on dopaminergic medications and dopamine antagonists (n=79) were also performed as dopaminergic pathways have been implicated in PLMS.[31–33] All significance levels reported are two-sided and all analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

3.1 STUDY POPULATION

The adjudicated AF cohort of 2273 elderly men had a mean age of 76.1±5.5 years, were primarily Caucasian (89.8%), were on average overweight (BMI of 27.2±3.7 kg/m2), and had a high prevalence of hypertension (49.4%), cardiovascular disease (27.8%), and heart failure (4.1%). Over half of the cohort was on antihypertensive medication and 35.8% were on cardiovascular medications. The average PLMI and PLMAI was 35.6 ± 37.6 and 4.0 ± 5.7, respectively. Only 3.5% of the population was on dopaminergic or dopamine antagonist medications.

Those 843 men in the self-report cohort were similar to the 1473 men who did not participate in Sleep Visit 2 who had acceptable PSG data and no history of AF in terms of AHI, BMI, and rates of, stroke, diabetes, pacemaker placement, use of dopaminergic medications or dopamine antagonists, and smoking (p>0.05). However, the men not included in the self-report analysis were on average older by 2.5 years, had a higher PLMI by 4.42 on average, and a higher disease prevalence of hypertension, CVD, CHF, hypertension, higher rate of use of anti-hypertensives and cardiac medication, less physical activity, lower eGFR, and lower alcohol intake (p<0.05).

When compared across PLMI categories, mean age and percentage of Caucasians increased as PLMI increased (Table 1). Participants in the lowest category of PLMI had better renal function as measured by eGFR. Further baseline characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by Periodic Limb Movement Index Category

| Characteristic | Overall (N= 2273) |

PLMI < 5 (N=663) |

PLMI 5 to <30 (N = 599) |

PLMI ≥30 (N = 1011) |

p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 76.1 +/− 5.5 | 75.4 +/− 5.0 | 75.8 +/− 5.5 | 76.8 +/− 5.7 | <.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 2041 (89.8) | 566 (85.4) | 527 (88.0) | 948 (93.8) | <.0001 |

| African American | 83 (3.7) | 44 (6.6) | 27 (4.5) | 12 (1.2) | |

| Asian | 72 (3.2) | 27 (4.1) | 19 (3.2) | 26 (2.6) | |

| Other | 77 (3.4) | 26 (3.9) | 26 (4.3) | 25 (2.5) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.2 +/− 3.7 | 27.2 +/− 3.9 | 27.0 +/− 3.8 | 27.2 +/− 3.6 | 0.65 |

| History of: | |||||

| Hypertension | 1122 (49.4) | 306 (46.2) | 302 (50.4) | 514 (50.8) | 0.15 |

| Cardiovascular disease* | 631 (27.8) | 164 (24.9) | 170 (28.4) | 297 (29.4) | 0.12 |

| Congestive heart failure | 94 (4.1) | 30 (4.5) | 28 (4.7) | 36 (3.6) | 0.46 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 310 (13.6) | 85 (12.8) | 71 (11.9) | 154 (15.2) | 0.13 |

| Stroke | 80 (3.5) | 25 (3.8) | 16 (2.7) | 39 (3.9) | 0.42 |

| Current medication use: | |||||

| Cardiovascular medications† | 813 (35.8) | 215 (32.4) | 215 (35.9) | 383 (37.9) | 0.08 |

| Antihypertensives | 1270 (55.9) | 353 (53.2) | 330 (55.1) | 587 (58.1) | 0.14 |

| Dopamenergics | 24 (1.1) | 3 (0.5) | 9 (1.5) | 12 (1.2) | 0.16 |

| Dopamine antagonists** | 58 (2.6) | 18 (2.7) | 13 (2.2) | 27 (2.7) | 0.79 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate, mL/min/1.73m2 |

71.1 +/− 16.8 | 72.5 +/− 16.5 | 70.2 +/− 17.3 | 70.6 +/− 16.7 | 0.03 |

| Pacemaker placement | 62 (2.7) | 17 (2.6) | 16 (2.7) | 29 (2.9) | 0.93 |

| Current smoker | 46 (2.0) | 12 (1.8) | 13 (2.2) | 21 (2.1) | 0.89 |

| Alcohol use, drinks per week | |||||

| <1 | 1069 (47.3) | 299 (45.5) | 284 (47.5) | 486 (48.4) | 0.47 |

| 1 to 13 | 1070 (47.4) | 328 (49.9) | 277 (46.3) | 465 (46.3) | |

| 14+ | 121 (5.4) | 30 (4.6) | 37 (6.2) | 54 (5.4) | |

| PASE physical activity score | 147.9 +/− 71.6 | 153.7 +/− 76.1 | 141.9 +/− 70.7 | 147.6 +/− 68.8 | 0.01 |

| Total Cholesterol, mg/dL | 193.6 +/− 33.9 | 195.0 +/− 34.9 | 195.7 +/− 32.4 | 191.5 +/− 34.1 | 0.04 |

| Apnea-hypopnea index | 16.9 +/− 15.0 | 18.0 +/− 15.6 | 16.3 +/− 14.4 | 16.4 +/− 14.9 | 0.09 |

| Periodic limb movement index | 35.6 +/− 37.6 | 1.3 +/− 1.5 | 16.8 +/− 7.2 | 69.3 +/− 32.1 | <.0001 |

| Periodic limb movement with arousal index |

4.0 +/− 5.7 | 0.2 +/− 0.4 | 2.1 +/− 2.5 | 7.6 +/− 6.7 | <.0001 |

Data shown as mean +/− SD or N(%). P-values for continuous variables are from an ANOVA for normally distributed variables, a Kruskal Wallis test for skewed data. Categorical variable p-values are from a chi-square test for homogeneity.

Includes myocardial infarction, angina, coronary bypass surgery, and angioplasty.

Includes calcium channel blockers, non-ophthalmic beta-blockers, cardiac glycosides, and anti-arrhythmic medications – cardiac sodium channel blockers and potassium channel blockers

Includes antipsychotics, domperidone, prochlorperazine, perphenazine, chlorpromazine, 599 metoclopramide, or tricyclic antidepressants

asked of a subset of 843 men.

3.2 PERIODIC LIMB MOVEMENTS DURING SLEEP AND INCIDENT ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

There were 261 cases (11.5%) of incident adjudicated AF events and 85 cases (10.1%) of self-reported incident AF. In unadjusted and multivariable adjusted analyses, increasing PLMI or PLMAI category was not associated with incident adjudicated events or self-reported AF (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Associations between periodic limb movements and incident clinically-symptomatic atrial fibrillation

| Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | N(%) Events | Unadjusted | Multivariable Adjusted* |

| Periodic Limb Movement Index | |||

| <5 (n=663) | 63 (9.50) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5 to <30 (n=599) | 74 (12.35) | 1.29 (0.92, 1.81) | 1.26 (0.89, 1.78) |

| 30+ (n=1,011) | 124 (12.27) | 1.34 (0.99, 1.81) | 1.18 (0.85, 1.62) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.07 | 0.39 | |

| Periodic Limb Movement Arousal Index | |||

| <1 (n=892) | 92 (10.31) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1 to <5 (n=754) | 93 (12.33) | 1.24 (0.93, 1.66) | 1.16 (0.86, 1.57) |

| 5+ (n=599) | 75 (12.52) | 1.27 (0.93, 1.72) | 1.06 (0.77, 1.46) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.11 | 0.67 | |

Adjusted for clinic, age, race, body mass index, self-reported medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and heart failure), cardiovascular medication use, pacemaker placement, alcohol use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, cholesterol, and apnea-hypopnea index.

Table 3.

Associations between periodic limb movements and incident self-reported atrial fibrillation

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | N(%) Events | Unadjusted | Multivariable Adjusted* |

| Periodic Limb Movement Index | |||

| <5 (n=258) | 21 (8.14) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5 to <30 (n=237) | 22 (9.28) | 1.16 (0.62, 2.16) | 1.05 (0.53, 2.07) |

| 30+ (n=348) | 42 (12.07) | 1.55 (0.89, 2.69) | 1.55 (0.84, 2.84) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.11 | 0.13 | |

| Periodic Limb Movement Arousal Index | |||

| <1 (n=350) | 29 (8.29) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1 to <5 (n=273) | 33 (12.09) | 1.52 (0.90, 2.58) | 1.55 (0.88, 2.72) |

| 5+ (n=213) | 23 (10.80) | 1.34 (0.75, 2.38) | 1.02 (0.52, 1.97) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.26 | 0.78 | |

Adjusted for clinic, age, race, body mass index, self-reported medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and heart failure), cardiovascular medication use, pacemaker placement, alcohol use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, cholesterol, and apnea-hypopnea index.

3.3 SECONDARY ANALYSES

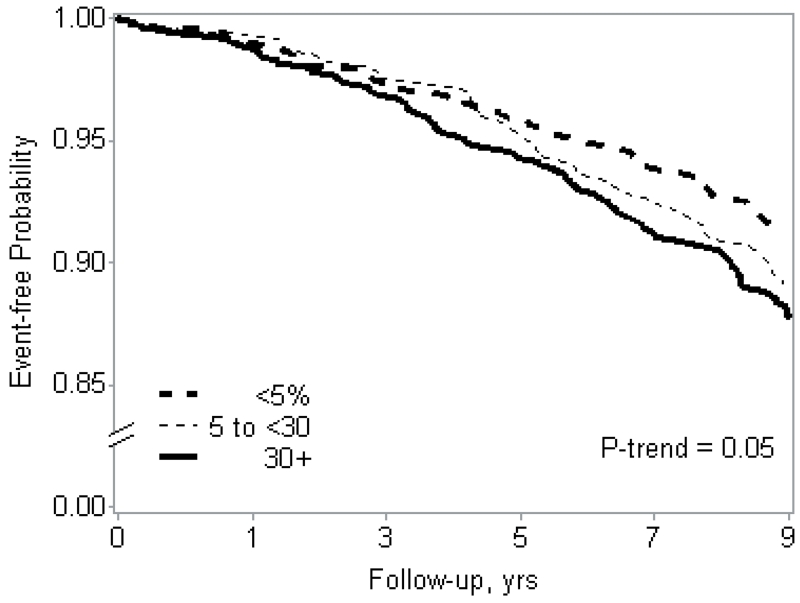

We observed some evidence of a statistical interaction between PLMI and PLMAI with age (p = 0.08 and p = 0.06, respectively) for the adjudicated AF outcome when age was examined categorically (Table 4) but only for PLMI when age was examined as a continuous variable (p=0.04). We observed some evidence of an interaction between PLMAI (p = 0.04 categorical age, p=0.02 continuous age) but not PLMI (p>=0.27) with age for the self-reported AF outcome (Table 5). When stratified by median age (<76 vs. ≥76), there were no associations between PLMS and AF in younger men. However, there was a significant association between higher levels of PLMI and incident adjudicated AF events (Table 4) and self-reported AF (Table 5) in men ≥76 years. We observed a significant linear trend in the association of PLMI categories and incident adjudicated AF events in the unadjusted model (p = 0.02), however results were slightly attenuated after adjustment (p-trend = 0.05, Figure 2). There was also a significant linear trend in the association of PLMI categories and incident self-reported AF in both unadjusted and adjusted models (p=0.01). A moderate increase in PLMAI was significantly associated with incident adjudicated AF events (Table 4) and self-reported (Table 5) AF in the older subgroup.

Table 4.

Associations of Periodic limb movements and incident clinically-symptomatic atrial fibrillation stratified by age

| Hazard Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | N(%) Events | Unadjusted | Multivariable adjusted* |

| Periodic Limb Movement Index † | |||

| Age < 76 (n = 1168) | |||

| <5 (n=374) | 36 (9.63) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5 to <30 (n=331) | 41 (12.39) | 1.29 (0.83, 2.02) | 1.21 (0.77, 1.90) |

| 30+ (n=463) | 44 (9.50) | 0.98 (0.63, 1.52) | 0.88 (0.56, 1.38) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.86 | 0.51 | |

| Age ≥ 76 (n = 1105) | |||

| <5 (n=289) | 27 (9.34) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5 to <30 (n=268) | 33 (12.31) | 1.29 (0.78, 2.15) | 1.49 (0.86, 2.60) |

| 30+ (n=548) | 80 (14.60) | 1.64 (1.06, 2.53) | 1.63 (1.01, 2.63) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.02 | 0.052 | |

| Periodic Limb Movement Arousal Index | |||

| Age < 76 (n = 1155)** | |||

| <1 (n=497) | 55 (11.07) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1 to <5 (n=400) | 40 (10.00) | 0.91 (0.61, 1.37) | 0.87 (0.58, 1.33) |

| 5+ (n=258) | 25 (9.69) | 0.88 (0.55, 1.41) | 0.76 (0.47, 1.24) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.57 | 0.26 | |

| Age ≥ 76 (n = 1090) | |||

| <1 (n=395) | 37 (9.37) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1 to <5 (n=354) | 53 (14.97) | 1.72 (1.13, 2.61) | 1.65 (1.05, 2.58) |

| 5+ (n=341) | 50 (14.66) | 1.62 (1.06, 2.48) | 1.41 (0.89, 2.23) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.03 | 0.15 | |

adjusted for clinic, age, race, body mass index, self-reported medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and heart failure), cardiovascular medication use, pacemaker placement, alcohol use, estimated glomerular filtration rate cholesterol, and apnea-hypopnea index.

Significant interaction term for both age as a continuous (p = 0.04) and categorical variable (p = 0.08)

Interaction term for age as a continuous (p = 0.37) and categorical variable (p = 0.06)

Table 5.

Associations of Periodic limb movements and incident self-reported atrial fibrillation stratified by age

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | N(%) Events | Unadjusted | Multivariable adjusted* |

| Periodic Limb Movement Index † | |||

| Age < 76 (n = 529) | |||

| <5 (n=172) | 16 (9.30) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5 to <30 (n=157) | 16 (10.19) | 1.11 (0.53, 2.30) | 0.94 (0.42, 2.10) |

| 30+ (n=200) | 18 (9.00) | 0.96 (0.48, 1.96) | 0.88 (0.39, 1.93) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.91 | 0.74 | |

| Age ≥ 76 (n = 314) | |||

| <5 (n=86) | 5 (5.81) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 5 to <30 (n=80) | 6 (7.50) | 1.31 (0.39, 4.48) | 1.27 (0.29, 5.52) |

| 30+ (n=148) | 24 (16.22) | 3.14 (1.15, 8.55) | 3.93 (1.17, 13.20) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Periodic Limb Movement Arousal Index | |||

| Age < 76 (n = 526)** | |||

| <1 (n=229) | 23 (10.04) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1 to <5 (n=179) | 16 (8.94) | 0.88 (0.45, 1.72) | 0.77 (0.37, 1.61) |

| 5+ (n=118) | 11 (9.32) | 0.92 (0.43, 1.96) | 0.70 (0.29, 1.69) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.78 | 0.38 | |

| Age ≥ 76 (n = 310) | |||

| <1 (n=121) | 6 (4.96) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| 1 to <5 (n=94) | 17 (18.09) | 4.23 (1.60, 11.21) | 5.76 (1.76, 18.84) |

| 5+ (n=95) | 12 (12.63) | 2.77 (1.00, 7.68) | 2.46 (0.68, 8.89) |

| p-trend across categories | 0.056 | 0.16 | |

adjusted for clinic, age, race, body mass index, self-reported medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and heart failure), cardiovascular medication use, pacemaker placement, alcohol use, estimated glomerular filtration rate cholesterol, and apnea-hypopnea index.

Interaction terms for both age as a continuous and categorical variable, p >=0.27

Interaction term for age as a continuous (p = 0.06) and categorical variable (p = 0.02)

Figure 2.

Cumulative Event-Free Probability of Incident Clinically-Symptomatic Atrial Fibrillation by Periodic Limb Movement Index, Age ≥76 Strata, Multivariable Adjusted*

| No. at risk for first incident event: | ||||||

| <5 | 289 | 285 | 259 | 226 | 187 | 160 |

| 5 to <30 | 268 | 263 | 241 | 219 | 189 | 153 |

| 30+ | 548 | 529 | 477 | 411 | 343 | 272 |

* Adjusted for clinic, age, race, body mass index, self-reported medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, stroke and heart failure), cardiovascular medication use, pacemaker placement, alcohol use, estimated glomerular filtration rate, cholesterol, and apnea-hypopnea index.

We found no significant interactions between CVD medication use and PLMI or PLMAI (p>=0.21). There was no interaction between history of CVD/CHF and PLMI or PLMAI (p>=0.33). No appreciable difference in results was observed after exclusion of men on dopaminergic medications or dopamine antagonists.

4. DISCUSSION

In this prospective, multi-center, community-based cohort study of elderly men, we did not find a significant association of PLMI or PLMAI relative to either self-reported AF or adjudicated AF events in the overall cohort. There was some evidence of an interaction between PLMS and age. Age-stratified analyses revealed that in the older subgroup of this elderly male cohort, the highest levels of PLMI and moderate increases in PLMAI were associated with both incident adjudicated and self-reported AF. No significant relationships were found in analyses stratified by cardiovascular medication or self-reported history of heart failure and/or cardiovascular disease. Results were similar after excluding men on dopaminergic or dopamine antagonist medication. Our results suggest that periodic limb movements during sleep may be a associated with an increased incidence of AF risk in the older subgroup of men, a group who also may have a high prevalence of electrical or structural alterations in their atria.

Autonomic system dysregulation is implicated in AF triggering with adrenergic AF predominating in the elderly population which may provide the explanation of the stronger magnitude of association of PLMS and AF identified in the older subgroup of the aged cohort.[34] Sympathetic activation of cardiac neurons has been shown to potentiate atrial arrhythmias including AF.[34] PLMS are known to cause sympathetic activation manifested by tachycardia and hypertension.[35,36] Analyses of heart rate variability, that measure the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, have shown increased sympathetic tone and decreased variability with PLMS.[8,37,38] Sympathetic activation is a potential trigger for AF from PLMS in the elderly. In addition, the older heart is a fundamentally different substrate with a predisposition towards AF initiation.[39–44] Both effective refractory period, which primes the heart for atrial reentrant circuits, and percent maximum atrial fragmentation, a measure reflective of AF inducibility, correlated with age in participants with no risk factors for AF.[41,42,45,46] Other work showed significant pulmonary vein electroanatomic changes with age which may be secondary to age-related atrial fibrosis.[29,44,47,48] Previous work on this topic has not examined the effects of age on the PLMS-AF relationship.

Previous studies have associated PLMS with cardiovascular disease.[11–13] Some, but not all, studies have linked restless legs syndrome, a condition which often includes PLMS, with cardiovascular outcomes.[49–52] Several potential reasons may explain the lack of observation of an overall association of PLMS and incident AF in this study. First, potential mechanisms by which PLMS may increase risk for heart failure and stroke may not have a significant effect on arrhythmia generation. Second, it is possible that the sympathetic activation by PLMS is not sufficient to trigger AF in the overall cohort; however, the more aged subgroup may be more susceptible to these sympathetic surges. AF may be differentially induced in younger compared to older individuals by pathogenic mechanisms such as re-entry and triggered automaticity. Therefore, findings of this cohort may differ from studies with younger populations. Third, since no direct measures of sympathetic activation were used in our study, processes causing sympathetic activation which do not cause PLMS may confound the analysis. Fourth, although PLMS are associated with sympathetic activation, the extent of this activation may not be sufficient to serve as a relevant AF exposure. Fifth, it is possible that competing risk factors or increased PLMS prevalence in this elderly cohort preclude our ability to appreciate a significant relationship between PLMS and AF, or that the study was under-powered to detect small to modest associations. However, it is also possible that the subgroup associations are chance findings and do not represent increased risk.

Cross-sectional work in the MrOS cohort investigating prevalent arrhythmias in relation to PLMS found a significant interaction between prevalent AF and cardiovascular disease.[8] The results of this cross-sectional study emphasize that in limited subgroups of men PLMS may increase risk for AF. Our analysis is consistent in finding that PLMS does not appear to be a significant factor in AF development in older men. On the other hand, unlike the cross-sectional study, our analysis of incident AF found no significant interaction with either history of CVD/CHF or atrioventricular blockade medication use; the latter of which can mitigate AF development by inhibiting tachycardia and preventing adrenergic-mediated AF potentially confounding examination of PLMS influences. Moreover, heart failure predisposes to delayed after-depolarizations and triggered activity which lead to focal ectopic firing, and superimposed PLMS and accompanying autonomic alterations may serve as facilitators of arrhythmia development or perpetuation.[53,54] Differences in prospective and cross-sectional results in the MrOS cohort may be secondary to different pathophysiologic underpinnings of initiation versus perpetuation of AF. Our findings also contrast with those of a smaller cohort of 373 patients with known paroxysmal or persistent AF undergoing polysomnography. After a 33 month follow-up, those with elevated PLMI (≤35 vs. >35) had a higher probability of progression to persistent or chronic AF and treatment with a dopamine agonist decreased this risk three-fold.[8] Thus it is possible that once AF is present, PLMS may lead to arrhythmia perpetuation but not significantly increase the risk of arrhythmia origination.

Strengths of this study include the prospective design, large cohort, and high rate of follow-up completers (99%). Standardized protocols and procedures were used to maximize data integrity. Systematic consideration of several metrics of PLMS was conducted. Sensitivity analyses were performed to address confounding by age, cardiovascular medications, and dopaminergic or dopamine antagonist medications. Limitations of this study include possible residual confounding. Because this study focused on a cohort of community-dwelling elderly men, findings may not be generalizable to younger individuals or women. Although methods for excluding prevalent AF were not validated by chart review, we utilized two data sources to exclude baseline AF, i.e. subjective ascertainment and objective ECG data collected from the sleep study. Individuals most at risk of PLMS-related AF may have manifest AF early in the study and have thus been excluded from analyses potentially biasing the study towards the null hypothesis. Small AF event counts in age-stratified analyses led to large confidence intervals which may be secondary to small differences in AF incidence and potentially overestimate true risk. Although AHI was included in the multivariable model, residual confounding by SDB cannot be excluded. Because several secondary analyses were performed, they should be interpreted cautiously as they may be chance findings. Use of piezoelectric sensors for movement detection is not the current standard; however, a separate validation analysis has shown this approach yields PLMI with very good correlation (r=0.83) to electromyography and 2013 scoring rules. [24,55] Assessments were performed on a single night and may have misclassified some participants due to night-to-night variation. Although we accounted for AHI and performed visual inspection of a random sampling of PSG recordings, we did not perform specific testing for respiratory event related arousals associated with leg movements. We also did not have high quality information on restless legs syndrome, which may represent a clinically important aspect of the “at risk” phenotype. Measures of cardiac function such as echocardiography were not included, which precludes examination of cardiac structure and function mediation of PLMS and AF relationships.

This study found no association between PLMS indices and AF in the overall cohort. Suggestion of an interaction with age and PLMS was observed; however, this finding should be interpreted with caution and requires further substantiation and reproducibility in future studies. Further work should examine PLMS relationships to arrhythmia in other populations including women and non-elderly adults to determine if PLMS are associated with AF in these subgroups since there may be differential pathophysiologic basis for AF development compared to elderly men. Further examination of the influence of PLMS on AF progression, patient-reported outcomes, and adverse events is warranted. Future investigation of the underlying pathways which may link PLMS and AF should focus on the temporal relationships of these events at a more granular scale, attempt to better define associated autonomic nervous system responses, and carefully examine for alterations in cardiac structure and function. Attempts to address the confounding by other etiologies of sympathetic activation could be approached by future studies employing direct measures of sympathetic activation. More study on whether PLMS are a product of an overactive sympathetic system or a driver of sympathetic activation would be key to the understanding of these events as either markers or potential instigators of cardiovascular sequalae.

Highlights.

Periodic limb movement during sleep (PLMS) are implicated in cardiovascular morbidity.

We investigated PLMS associations and incident atrial fibrillation (AF) in a large older male cohort.

No overall PLMS and AF association was identified.

Suggestion of interaction between age and PLMS was observed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Financial Support

The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study is supported by National Institutes of Health funding. The following institutes provide support: the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research under the following grant numbers: U01 AR45580, U01 AR45614, U01 AR45632, U01 AR45647, U01 AR45654, U01 AR45583, U01 AG18197, U01 AG027810, and UL1 TR000128.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) provides funding for the MrOS Sleep ancillary study “Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men” under the following grant numbers: R01 HL071194, R01 HL070848, R01 HL070847, R01 HL070842, R01 HL070841, R01 HL070837, R01 HL070838, and R01 HL070839.

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. There were no relationships with industry related to this work. There were no off-label or investigational use of drugs or devices used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lip GY, Tean KN, Dunn FG. Treatment of atrial fibrillation in a district general hospital. Br Heart J. 1994;71:92–5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.71.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98:946–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1449–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ferri R, Zucconi M, Rundo F, Spruyt K, Manconi M, Ferini-Strambi L. Heart rate and spectral EEG changes accompanying periodic and non-periodic leg movements during sleep. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:438–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.10.007. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Winkelman JW. The evoked heart rate response to periodic leg movements of sleep. Sleep. 1999;22:575–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.5.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lavoie S, de Bilbao F, Haba-Rubio J, Ibanez V, Sforza E. Influence of sleep stage and wakefulness on spectral EEG activity and heart rate variations around periodic leg movements. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:2236–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.04.024. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Guggisberg AG, Hess CW, Mathis J. The significance of the sympathetic nervous system in the pathophysiology of periodic leg movements in sleep. Sleep. 2007;30:755–66. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sforza E, Pichot V, Barthelemy JC, Haba-Rubio J, Roche F. Cardiovascular variability during periodic leg movements: a spectral analysis approach. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:1096–104. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.12.018. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Walter LM, Foster AM, Patterson RR, Anderson V, Davey MJ, Nixon GM, et al. Cardiovascular Variability During Periodic Leg Movements in Sleep in Children. Sleep. 2009;32:1093–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.8.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Koo BB, Blackwell T, Ancoli-Israel S, Stone KL, Stefanick ML, Redline S, et al. Association of Incident Cardiovascular Disease With Periodic Limb Movements During Sleep in Older Men: Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men (MrOS) Study. Circulation. 2011;124:1223–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.038968. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.038968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mirza M, Shen W-K, Sofi A, Tran C, Jahangir A, Sultan S, et al. Frequent Periodic Leg Movement During Sleep Is an Unrecognized Risk Factor for Progression of Atrial Fibrillation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078359. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mirza M, Shen W-K, Sofi A, Jahangir A, Mori N, Tajik AJ, et al. Frequent Periodic Leg Movement during Sleep Is Associated with Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:783–90. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.03.018. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rye DB, Trotti LM. Restless Legs Syndrome and Periodic Leg Movements of Sleep. Neurol Clin. 2012;30:1137–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2012.08.004. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Koo BB, Mehra R, Blackwell T, Ancoli-Israel S, Stone KL, Redline S. Periodic Limb Movements during Sleep and Cardiac Arrhythmia in Older Men (MrOS Sleep) J Clin Sleep Med. 2014 doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3346. doi:10.5664/jcsm.3346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Orwoll E, Blank JB, Barrett-Connor E, Cauley J, Cummings S, Ensrud K, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study--a large observational study of the determinants of fracture in older men. Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26:569–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.006. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Blank JB, Cawthon PM, Carrion-Petersen ML, Harper L, Johnson JP, Mitson E, et al. Overview of recruitment for the osteoporotic fractures in men study (MrOS) Contemp Clin Trials. 2005;26:557–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.005. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mehra R, Stone KL, Varosy PD, Hoffman AR, Marcus GM, Blackwell T, et al. Nocturnal Arrhythmias across a spectrum of obstructive and central sleep-disordered breathing in older men: outcomes of sleep disorders in older men (MrOS sleep) study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1147–55. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.138. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Redline S, Sanders MH, Lind BK, Quan SF, Iber C, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Sleep Heart Health Research Group Methods for obtaining and analyzing unattended polysomnography data for a multicenter study. Sleep. 1998;21:759–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. In: Rechtschaffen Allan, Kales Anthony., editors. U.S. National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness, Neurological Information Network; Bethesda, Md.: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- [21].American Sleep Disorders Association EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples: a preliminary report from the Sleep Disorders Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep. 1992;15:173–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, Gozal D, Iber C, Kapur VK, et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8:597–619. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2172. doi:10.5664/jcsm.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Quan SF, Howard BV, Iber C, Kiley JP, Nieto FJ, O’Connor GT, et al. The Sleep Heart Health Study: design, rationale, and methods. Sleep. 1997;20:1077–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Berry RB, Gamaldo CE, Harding SM, Lloyd RM, Marcus CL, Vaughn BV, et al. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Version 2.0.2. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Darien, IL: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Iber Conrad, Anconi-Israel Sonia, Chesson Andrew L., Quan Stuart F., for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine . The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; Westchester, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pahor M, Chrischilles EA, Guralnik JM, Brown SL, Wallace RB, Carbonin P. Drug data coding and analysis in epidemiologic studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:405–11. doi: 10.1007/BF01719664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–62. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Inker LA, Shaffi K, Levey AS. Estimating glomerular filtration rate using the chronic kidney disease-epidemiology collaboration creatinine equation: better risk predictions. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:303–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.968545. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.968545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Dun W, Boyden PA. Aged atria: electrical remodeling conducive to atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2009;25:9–18. doi: 10.1007/s10840-008-9358-3. doi:10.1007/s10840-008-9358-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, Gottlieb DJ, Nawabit R, Kirchner HL, et al. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:910–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1442OC. doi:10.1164/rccm.200509-1442OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hornyak M, Hundemer H-P, Quail D, Riemann D, Voderholzer U, Trenkwalder C. Relationship of periodic leg movements and severity of restless legs syndrome: A study in unmedicated and medicated patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:1532–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.001. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lee YA, Huynh P, Neher JO, Safranek S. Clinical Inquiry. What drugs are effective for periodic limb movement disorder? J Fam Pract. 2012;61:296–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Staedt J, Stoppe G, Kögler A, Munz D, Riemann H, Emrich D, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor alteration in patients with periodic movements in sleep (nocturnal myoclonus) J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1993;93:71–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01244940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chen P-S, Chen LS, Fishbein MC, Lin S-F, Nattel S. Role of the Autonomic Nervous System in Atrial Fibrillation: Pathophysiology and Therapy. Circ Res. 2014;114:1500–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303772. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Winkelman JW. The evoked heart rate response to periodic leg movements of sleep. Sleep. 1999;22:575–80. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.5.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sforza E, Pichot V, Barthelemy JC, Haba-Rubio J, Roche F. Cardiovascular variability during periodic leg movements: a spectral analysis approach. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:1096–104. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.12.018. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2004.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sforza E, Juony C, Ibanez V. Time-dependent variation in cerebral and autonomic activity during periodic leg movements in sleep: implications for arousal mechanisms. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:883–91. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lavoie S, de Bilbao F, Haba-Rubio J, Ibanez V, Sforza E. Influence of sleep stage and wakefulness on spectral EEG activity and heart rate variations around periodic leg movements. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:2236–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.04.024. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Li H, Scherlag BJ, Kem DC, Zillner C, Male S, Thirunavukkarasu S, et al. The Propensity for Inducing Atrial Fibrillation: A Comparative Study on Old versus Young Rabbits. J Aging Res. 2014;2014:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2014/684918. doi:10.1155/2014/684918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Rosenberg MA, Maziarz M, Tan AY, Glazer NL, Zieman SJ, Kizer JR, et al. Circulating fibrosis biomarkers and risk of atrial fibrillation: The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Am Heart J. 2014;167:723–728. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.01.010. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sakabe K, Fukuda N, Nada T, Shinohara H, Tamura Y, Wakatsuki T, et al. Age-related changes in the electrophysiologic properties of the atrium in patients with no history of atrial fibrillation. Jpn Heart J. 2003;44:385–393. doi: 10.1536/jhj.44.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sakabe K, Fukuda N, Soeki T, Shinohara H, Tamura Y, Wakatsuki T, et al. Relation of age and sex to atrial electrophysiological properties in patients with no history of atrial fibrillation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:1238–1244. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.t01-1-00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Spach MS, Heidlage JF, Dolber PC, Barr RC. Mechanism of origin of conduction disturbances in aging human atrial bundles: Experimental and model study. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:175–85. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.10.023. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Teh AW, Kalman JM, Lee G, Medi C, Heck PM, Ling L-H, et al. Electroanatomic remodelling of the pulmonary veins associated with age. Europace. 2012;14:46–51. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur275. doi:10.1093/europace/eur275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Boineau JP, Schuessler RB, Mooney CR, Miller CB, Wylds AC, Hudson RD, et al. Natural and evoked atrial flutter due to circus movement in dogs. Role of abnormal atrial pathways, slow conduction, nonuniform refractory period distribution and premature beats. Am J Cardiol. 1980;45:1167–81. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(80)90475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sato S, Yamauchi S, Schuessler RB, Boineau JP, Matsunaga Y, Cox JL. The effect of augmented atrial hypothermia on atrial refractory period, conduction, and atrial flutter/fibrillation in the canine heart. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;104:297–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hayashi H, Wang C, Miyauchi Y, Omichi C, PAK H-N, Zhou S, et al. Aging-Related Increase to Inducible Atrial Fibrillation in the Rat Model. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:801–808. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Anyukhovsky E, Sosunov E, Chandra P, Rosen T, Boyden P, Danilojr P, et al. Age-associated changes in electrophysiologic remodeling: a potential contributor to initiation of atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:353–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.033. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Winkelman JW, Shahar E, Sharief I, Gottlieb DJ. Association of restless legs syndrome and cardiovascular disease in the Sleep Heart Health Study. Neurology. 2008;70:35–42. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000287072.93277.c9. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000287072.93277.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Schlesinger I, Erikh I, Avizohar O, Sprecher E, Yarnitsky D. Cardiovascular risk factors in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2009;24:1587–92. doi: 10.1002/mds.22486. doi:10.1002/mds.22486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Li Y, Walters AS, Chiuve SE, Rimm EB, Winkelman JW, Gao X. Prospective study of restless legs syndrome and coronary heart disease among women. Circulation. 2012;126:1689–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.112698. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.112.112698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Winter AC, Schurks M, Glynn RJ, Buring JE, Gaziano JM, Berger K, et al. Vascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and restless legs syndrome in women. Am J Med. 2013;126:220–7. 227–2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.040. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Caldwell JC, Mamas MA. Heart failure, diastolic dysfunction and atrial fibrillation; mechanistic insight of a complex inter-relationship. Heart Fail Rev. 2012;17:27–33. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9204-4. doi:10.1007/s10741-010-9204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Andrade J, Khairy P, Dobrev D, Nattel S. The Clinical Profile and Pathophysiology of Atrial Fibrillation Relationships Among Clinical Features, Epidemiology, and Mechanisms. Circ Res. 2014;114:1453–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303211. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Claman DM, Ewing SK, Redline S, Ancoli-Israel S, Cauley JA, Stone KL. Periodic Leg Movements Are Associated with Reduced Sleep Quality in Older Men: The MrOS Sleep Study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013 doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3146. doi:10.5664/jcsm.3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]