Abstract

Background

Obesity levels in the UK have reached a sustained high and ∼4% of the population would be candidates for bariatric surgery based upon current UK NICE guidelines, which has important implications for Clinical Commissioning Groups.

Sources of data

Summary data from Cochrane systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies.

Areas of agreement

Currently, the only treatment that offers significant and durable weight loss for those with severe and complex obesity is surgery. Three operations account for 95% of all bariatric surgery in the UK, but the NHS offers surgery to only a small fraction of those who could benefit. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (gastric banding) has potentially the lowest risk and up-front costs of the three procedures.

Areas of controversy

Reliable Level 1 evidence of the relative effectiveness of the operations is lacking.

Growing points

As a point intervention, weight loss surgery together with the chronic disease management strategy for obesity can prevent significant future disease and mortality, and the NHS should embrace both.

Areas timely for developing research

Better RCT evidence is needed including clinical effectiveness and economic analysis to answer the important question ‘which is the best of the three operations most frequently performed?’ This review considers the current evidence for gastric banding for the treatment of severe and complex obesity.

Keywords: obesity surgery, bariatric surgery, metabolic surgery, gastric banding, diabetes treatment

Introduction

Obesity is a major worldwide public health problem with significant implications for primary care, particularly where obesity prevalence in developed countries is as high as 32.5% in women in high-income North American countries, 29.8% in Australasia and 21.0% in Western Europe.1 Although obesity levels may have reached a plateau, the burden of the important obesity-related co-morbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, which was 382 million people worldwide in 2013, is predicted to rise to over 590 million in 2035.2 Both diabetes and obesity are independent risk factors for many important cancers.3,4 Obesity significantly increases many functional disorders and worsens overall health-related quality of life,5 which can be improved by weight loss and metabolic surgery.6 Overall, there is substantial evidence that obesity is a chronic disease that shortens life expectancy, even with the current best medical management of its co-morbidities.7

Bariatric surgery is the only reproducibly effective treatment for severe and complex obesity.8,9 UK NICE guidelines provide clear guidance for the delivery of health care and recommend that bariatric surgery is the first line of treatment for those with a BMI of ≥50 in whom lifestyle interventions have failed; and those with a BMI ≥ 40 or ≥35 with severe obesity-related co-morbidities, should be offered bariatric surgery.10 Weight loss and metabolic surgery procedures are among the most commonly performed elective general surgical operations in the world, with over 350 000 performed in 2011,11 but in 2013 in the UK, with government funded health care, only around 8000 operations were performed,12,13 of which around 4300 operations are recorded as being performed in the public sector.14

Bariatric surgery is a young surgical speciality, with increasing numbers of cases being performed over a relatively short time frame,11 and there is a lack of high-quality, long-term outcome data for the procedures. The most up-to-date, 2014, Cochrane collaboration systematic review of weight loss surgery in adults could only provide synthesizable evidence for 3 years of follow-up and commented that ‘the long-term effects of surgery remain unclear’.8 However, this Level 1 evidence for short- and medium-term results of surgery can be compared directly to results for non-surgical interventions and combined with some long-term cohort studies of bariatric surgery, albeit in smaller numbers, to show a pattern of long-term benefits from surgery. Given the established long-term benefit, it is important to have large-scale, pragmatic randomized controlled surgical trials to evaluate different techniques, to include economic evaluations, to give us the answer as to what is the best operation.15

Gastric banding and how it facilitates weight loss

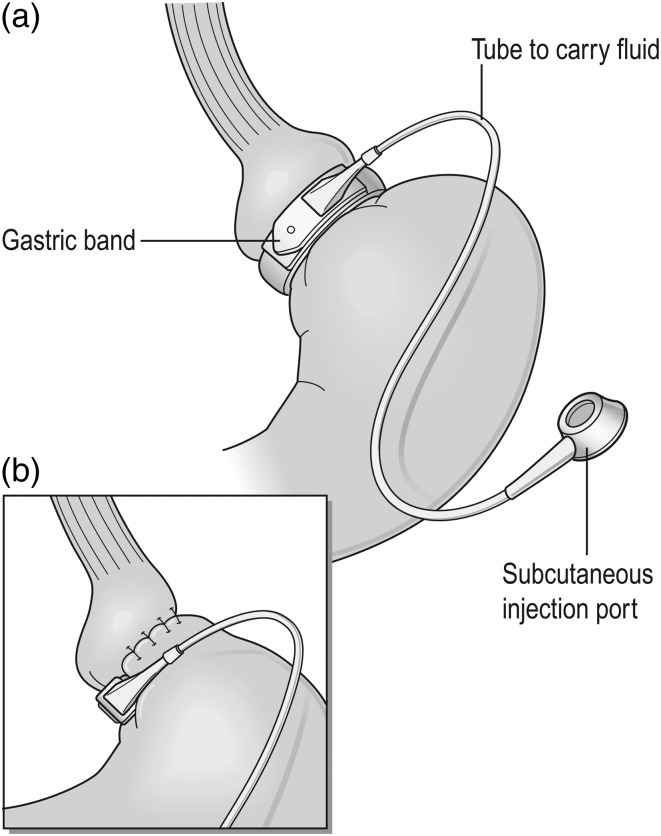

In the UK, >99% of gastric band procedures are performed laparoscopically and patients typically spend ≤1 day in hospital with very few early complications.12,13 The operation induces and sustains weight loss by activating a satiety mechanism. Adding or removing fluid from the band achieves optimal filling. Food is not retained above the optimally adjusted band, i.e. not physically restricted, but briefly delayed food bolus transit through the band and the continuous pressure of the optimally filled band on the stomach wall produces both early satiety and a lack of appetite.16 The effects of the band on oesophageal and proximal gastric function appear to activate a satiety signal, transmitted to CNS satiety centres via the vagus nerve, without physically restricting the meal size.16 Figure 1 shows the position of a gastric band with a small ‘virtual’ pouch of stomach below the gastro-oesophageal junction, above the final band position, held within gastro–gastro tunnelling sutures. Ideally patients are followed up every 1–3 months for the first 2 years by the bariatric multidisciplinary team (MDT) and then yearly in conjunction with GPs as part of a shared care model of chronic disease management (NICE CG189).10

Fig. 1.

The adjustable gastric band. (Images reproduced from Griffin et al.54).

Patients require lifelong follow-up for optimal weight control and co-morbidity resolution for gastric banding to work, especially as nutritional issues or complications can occur at any point after surgery.17,18 Symptoms of reflux, regurgitation or vomiting and especially nocturnal aspiration or dysphagia should alert the primary care GP to possible complications. Abdominal pain along with any of these symptoms may suggest an acute complication, but other causes of abdominal pain should always be considered. Lifelong care involves essential counselling about food choices and eating patterns, as well as adjustment of the band.18 Patients should therefore not be offered revisional surgery unless a process for continuing care is in place with the bariatric MDT and within primary care.

Weight loss effects of gastric bands and bariatric surgery

The 2014 Cochrane review into weight loss surgery for adults included 22 randomized trials with 1798 participants. The authors compared surgery with non-surgical interventions or different surgical procedures, and most studies followed participants for only 12–36 months.8 All of the trials that compared surgery with non-surgical interventions for weight loss found that surgery was significantly superior for weight loss at 1–2 years. This mirrored a 2013 systematic review and meta-analysis that directly compared surgery and medical therapy, using 11 randomized studies with 796 included patients, and a random-effect model, clearly favouring surgery.9 With study follow-up of up to 2 years, individuals undergoing bariatric surgery lost more body weight [mean difference −26 kg (95% confidence interval −31 to −21), P < 0.001] than those with medical therapy alone.

In the Cochrane review, no clinically significant differences between the three main techniques of gastric band, all types of gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy existed for the majority of time points within ‘multi-trial’ evidence. Although only three trials directly compared gastric banding with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (gastric bypass), the latter produced greater weight loss, with a mean difference in body mass index (BMI) reduction up to 5 years of −5.2 kg/m2 (95% confidence interval −6.4 to −4.0; P < 0.00001). However, this was only from a total of 265 patients when combined, and the quality of the evidence was described as moderate at best. In the seven included trials of gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy, there was no consistent picture as to which procedure was better or worse, but with a low quality of evidence.8 For the 2013 systematic review, the cumulative body weight loss was similar but not statistically significantly different between gastric banding and gastric bypass or other techniques combined (mean difference between 6 and 7 kg, P > 0.20).9 Effects on co-morbidities, complications and additional surgical procedures were neutral for the three main procedures in these reviews.8,9 Similarly, a large prospective database, the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative, concluded that there was comparable effectiveness of gastric banding, gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy for the treatment of severe obesity, when assessing weight loss and complications in three matched groups of nearly 3000 patients each over 3 years.19

As the low quality of evidence in data synthesis studies is a recurrent issue, there still exists a need for long-term data from a well-conducted, methodologically sound, pragmatic, multicentre, randomized trial of gastric banding and other bariatric techniques. Two ongoing trials surgical randomized trials are the Swiss Multi-centre Bypass or Sleeve Study20 and the UK By-Band randomized controlled trial.15 In 2015, the latter has been converted to a three-arm trial of gastric banding, gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy (By-Band-Sleeve) and is the only such trial in the world comparing all three techniques. Importantly, these trials both include outcomes of weight and quality of life as primary outcome measures and will also provide secondary outcome data on weight-related co-morbidities and an economic evaluation of the study groups.

Longer term weight loss outcomes for gastric banding

In the absence of well-conducted randomized trials with funded long-term data collection, long-term data of bariatric surgery are only available from observational studies and a few small, randomized trials. Most individual studies that quote >10-year data report that obstacles to follow-up impede the collection of accurate long-term data.21 The longest follow-up data are from the Swedish Obesity Study (SOS)22 and have shown that bariatric surgery can reduce mortality, as well as cardiovascular and cancer risk over >10 years, in matched groups of over 2000 patients. While two-thirds of the patients in the SOS studies had a procedure that is no longer considered first line for weight loss (vertical banded gastroplasty), the study includes gastric bands with the longest follow-up data being up to 20 years. The SOS shows maintenance of weight loss (18% of total body weight) in the all surgery groups at this time point, compared with 1% weight loss in controls, with sustainable reduction in diabetes rates, cardiovascular and cancer risks.23

The only randomized trial with long-term results of 10 years compared a small cohort (n = 51) of Italian patients randomized to gastric banding or gastric bypass.24 The mean per cent excess weight loss achieved at 10 years was 46 ± 27% for gastric banding vs. 69 ± 29% for gastric bypass. With a mean BMI of patients in the two groups of 44, this equals a total body weight loss of 19–27%, comparable to that seen in the SOS study. A larger (n = 197) US randomized trial with 4-year follow-up to 2007 measured similar excess weight loss outcomes with 45 ± 28% for gastric band vs. 68 ± 19% for bypass in the medium term, but bypass was associated with more perioperative and late complications and a higher early readmission rate.25 A systematic review of randomized and prospective studies comparing gastric banding with gastric bypass, with >3–5 years follow-up (29 studies with 7971 patients), similarly showed that the mean sample size-weighted percentage of excess weight loss for gastric banding was 45.0% (n = 4109) vs. 65.7% for gastric bypass (n = 3544).26 In all of these studies, gastric band patients had a slower initial weight loss, which was typically maintained in the medium to long term. In contrast, bypass patients lost weight rapidly in the first year and then started to regain some weight.23–26 Additionally with gastric banding, there is a proportion of patients, up to 15% who do not tolerate the band and fail to achieve any meaningful weight loss.27

Gastric banding is the most predominant technique in Australia, and from there O'Brien et al. have reported on 15-year follow-up data from a large prospectively followed cohort of over 3200 patients. The reported mean per cent excess weight loss data are similar, 47% at 10 years (n = 714) and at 15 years (although in only 54 patients).28 This again equals 20.2% total body weight loss maintained at 10–15 years in the study population.

Other long-term studies are ongoing, such as the US Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery,29 which is prospectively following nearly 2500 patients after weight loss surgery, one quarter of whom had a gastric band. Three-year results published so far suggest average weight loss of 16% total body weight for those undergoing a gastric band, with most of the weight loss coming in the first year for all patients. However, compared with gastric bypass patients (who started to regain some weight), the trajectory of weight change in the gastric banding group was maintained. In summary, all of the studies with at least 10-year follow-up suggest that a clinically significant total body weight loss of 16–20% is maintained in the long term following bariatric surgery, including gastric banding.

Diabetic outcomes with gastric banding

Diabetes patients are an important group of those undergoing bariatric surgery, accounting for nearly one-third of UK NHS bariatric patients,12,13 and they have potentially the greatest benefits with a reduction in long-term diabetic complications. Early studies into bariatric surgery suggested that four-fifths of all diabetic bariatric patients had a ‘resolution’ of diabetes at 2 years following surgery.30 However, a 2014 meta-analysis of longer term effects of metabolic surgery for type 2 diabetes, with stricter definitions for remission, reported a 65% remission rate and 89% remission or improvement rate in studies with >2 years of follow-up.31 The large UK national registry of bariatric surgery showed a 60–70% improvement in all diabetic patients at 3 years following surgery, with a decrease in medication use.12,13

A systematic review in 2012 of 35 studies involving gastric banding to treat diabetes showed remission or improvement in diabetes from 53 to 70% over 2 years, and although there was considerable heterogeneity in study quality, the authors concluded that clinically relevant improvements in diabetes outcomes occurred in obese people with type 2 diabetes following LAGB surgery.32 The only randomized trial included in this review by Dixon et al. considered that participants randomized to surgical therapy were more likely to achieve remission of type 2 diabetes through greater weight loss.33 The 2014 systematic review of studies comparing gastric banding with gastric bypass, included nine studies that measured co-morbidity improvement, and for type 2 diabetes (glycated haemoglobin <6.5% without medication), sample size-weighted remission rates were 28.6% for gastric band (n = 96) and 66.7% for gastric bypass (n = 428).26

The interim analysis to assess the early control of type 2 diabetes (T2D), 1 year after gastric banding in the 5-year, prospective, observational Helping Evaluate Reduction in Obesity (HERO) study (n = 1106) showed that 72% achieved target control of diabetes compared with 42% at baseline.34 It is important to note that in these band studies, and many other studies of bariatric surgery, patients with shorter disease duration and not yet on insulin have the best likelihood of control of diabetes.12,24,31–34 Others have even performed studies of gastric banding in patients with lower BMIs and shown that remission of diabetes can be achieved in 50% of patients.35 Reflecting similar studies of all bariatric surgery in diabetics, the 2014 UK NICE guidelines reduced the BMI threshold to 30 for ‘newly diagnosed diabetics’ to access bariatric surgery.10

Bariatric surgery can also aid diabetes prevention. In an analysis of SOS patients without diabetes (n = 3429) and a BMI of 34–38 at the start, after 15 years the incident rates of diabetes was 28.4 per 1000 in the controls but only 6.8 per 1000 in those who had surgery.36

Complication rates

The major complications of gastric banding requiring re-operation or removal are infection of the band, slippage and erosion, plus a group of patients who have intolerance of the band and fail to achieve any meaningful weight loss. For complications, the large systematic reviews of weight loss surgery report re-operation rates as high as 40%,8,9 but this includes some very early studies. Indeed, studies of bands placed pre-2000 reported rates of re-operation or removal as high as 60%,37 and O'Brien's long-term Australian study also reported similar revision rates of nearly 40% in the first 10 years after band placement.28 However, because of the evolution of band construction and operative technique, this had dropped to 6.4% over the last 5 years.28

The overall risks of all bariatric surgery itself are small, given the complex nature and co-morbidity burden of the patients involved, with the composite complication rate of gastric bypass (3.4%), being similar to that of laparoscopic cholecystectomy or hysterectomy.38 However, the reporting of adverse events in the outcomes of clinical trials is highly variable.39 A 2014 systematic review of the risks of bariatric surgery indicated a cumulative lifetime complication rate of 17% and a re-operation rate of 7%, but there were significant differences between the techniques.27 Thus, there were more early complications with gastric bypass than gastric banding, but the overall re-operation rate for banding was higher (although this mainly related to minor re-operations to the subcutaneous access port).19,24–30 Typically perioperative complications occurred more frequently following gastric bypass than banding (8.0 vs. 0.5%), while gastric bands had more long-term complications requiring corrective procedures than gastric bypass (9 vs. 2%). However, large volume gastric band units have shown that low re-operation rates, comparable overall to other procedures long term, are achievable.28 Thus, it may be that at a population level, this operation provides the greatest access to the benefits of weight loss surgery for the largest number of patients.

In view of this, it is surprising that the proportion of patients in the UK having gastric banding has reduced over the last 5 years from 21% among NHS patients in 2009–10 to 14% in 2011–13.12,13 Several factors may account for this: the rise in popularity of the gastric sleeve operation (despite the paucity of long-term data); the perceived difficulty with arranging optimal long-term care for patients; and peer pressure among patients due to the quicker weight loss attained with gastric bypass, even though weight loss at 3 years is comparable between all three operations. In contrast, the proportion of self-funded patients having banding was 42% in 2011–13, suggesting that it still maintains sufficient popularity and attractiveness to patients, perhaps due to its affordability. Patients also commonly perceive it as being less invasive than either gastric bypass or sleeve gastrectomy surgery, and indeed it is technically less invasive than these stapling operations.

Mortality rates

The overall mortality rate for all primary bariatric surgery12–14 is one-tenth that of cardiac surgery and comparable to elective arthroscopy, with the risk of gastric banding reportedly being the lowest of the currently available surgical options (<0.01 vs. 0.07% for gastric bypass).12,19,26,40 Long term there is reportedly survival benefit compared with no surgery for gastric banding patients.26,28

Revisional bariatric surgery and re-operations for gastric banding

Bariatric surgery prevents and treats disease and disability, and improves quality of life, but the need for re-operation (revisional surgery) reduces the clinical and cost-effectiveness. In addition to operations for complications (as above), revisional surgery may be considered for later weight regain. However, the cumulative burden of revisional surgery on the patient and healthcare systems may be substantial, and revision surgery to the same or another bariatric operation (not including minor reoperations on the subcutaneous band access port) carries a 14 times increased mortality.12,13,40

Weight regain after bariatric surgery is seen in a small but significant group of patients of all surgical techniques. Unfortunately, it is not possible to predict before surgery which patients will fail to lose much weight or who will have later weight regain. A recent systematic review suggested multifactorial causes,41 dietary, behavioural, physical, as well as surgical factors (in <20% of cases) which vary for the different techniques at different follow-up time points. Clearly, for gastric banding, intensive input from all members of the MDT and frequent (monthly) follow-up intervals after surgery are particularly important in producing and maintaining weight loss.42–44 As dietary, psychological and physical inactivity were the main factors in up to 80% of weight regain, addressing these requires a clinical service with a systematic approach to assess and identify those patients who may have a surgical factor for weight regain which might benefit from revisional surgery. Importantly, current data suggest that every patient who has had a gastric band removed, for any reason, will have weight regain back to or near their baseline level.45

Cost-effectiveness of gastric banding

The long-term benefits of bariatric surgery for weight loss, co-morbidity resolution, lower cancer rates and improved mortality could be expected to lead to a healthcare cost saving, but results are not that clear cut. While a systematic review in 201146 suggested that weight loss surgery was cost-effective compared with non-surgical treatment, a 2014 study on insurance provider claim costs after bariatric surgery showed no reduction in actual costs of claims.47 However, the measure used for comparison is important, and many studies in different countries have shown that the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per quality- or disability-adjusted life year varied from about £1300 for gastric banding in Australia48 to £4000–£4500 for all laparoscopic weight loss surgery in the USA.49 Interestingly, while all these values are far below the cost-effectiveness threshold for the respective countries (and also for the UK), gastric banding may be the most cost saving treatment at a population level.

An analysis of data using a decision analytic model from the Scandinavian Registry, covering cardiovascular disease, diabetes and surgical complications, showed that bariatric surgery led to a cost saving compared with non-surgical management of weight loss.50 When the risk reduction of vascular events, reduction in diabetes and gain in quality-adjusted life years were extrapolated for the whole cohort, operated on in 1 year, the lifetime gains were over 32 000 quality-adjusted person years, and a net saving of £43 million in healthcare costs.

The very low volume of bariatric surgery in the UK represents much less than 1 in 100 of the 5%, or 2.1 million people,51 who meet UK NICE guidelines for surgery. In other developed countries, there are large differences in the prevalence of co-morbidities and socio-demographic status between surgery-eligible patients and bariatric surgery recipients.52 Clearly no healthcare system could provide capacity to treat such a potentially great demand, but the overwhelming evidence is that surgery is clinically beneficial and cost-effective. Thus, the RCT evidence in the NICE Guidance showed clear improvement in every aspect of diabetes control, and on this basis, increasing availability of bariatric surgery should be a clear aspiration for healthcare services. Alternatively, the availability of government funded weight loss surgery could be limited to the procedure with the lowest costs and shortest hospitalization requirements, to maximize the opportunity for delivery of a service. This strategy would favour gastric banding, although this does not take into account the longer term follow-up costs, and the provision of services required, for gastric band adjustments in the community or specialized clinics.

Conclusions

Obesity, with nearly 30 million sufferers in the UK currently, and its treatment, is a huge problem for the NHS. Current evidence shows that only bariatric surgery gives clinically meaningful weight loss, although there is a paucity of high-quality, long-term evidence. Despite its effectiveness, <5000 bariatric procedures were performed in the NHS in 2013;12,13 thus, the NHS provides the life-saving and quality of life improving benefit of surgery to <1 in 4000 of the severely obese population in the UK. There would need to be a huge turn around in obesity service provision for any significant population health gains to be achieved. The nature of which operation would best deliver these gains is still unknown, more high-quality studies are needed, but with the lowest reported incremental cost-effectiveness ratio per quality-adjusted life year, gastric banding may provide the NHS with the most punch for its pound. However, unlike Australia, the UK NHS is not currently well set up to look after large number of gastric band patients and adjust the bands regularly in hospital (outside of clinical trials) or in the community. This issue of gastric band follow-up is probably the reason why many patients and surgeons do not choose gastric banding over other operations in the NHS. In addition, many bands are removed by surgeons in non-specialist centres if the patient develops a problem such as slippage, rather than having it rectified. It would also require a shift in the moral perspective of delivering treatments effective at improving quality of life to those with a significant need.53 Still a major unknown remains the costs associated with the management of the long-term complications of bariatric surgery, including that of modern gastric banding, which appear comparable for all techniques.

Conflict of interest statement

J.C.A.H., J.M.B. and C.A.R. declare no conflict of interest. R.W. received sponsorship for attending conference/educational workshops from Allergan and Ethicon Endo-Surgery and is a consultant for Novo Nordisk. Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton UK, also received grant funding for a bariatric surgery training fellowship from Ethicon Endo-Surgery.

References

- 1.Ng M, Fleming T, Robinson M et al. . Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014;384:766–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I et al. . Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;103:137–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Pergola G, Silvestris F. Obesity as a major risk factor for cancer. J Obes 2013;2013:291546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrigel DJ, Moss RA. Diabetes mellitus as a novel risk factor for gastrointestinal malignancies. Postgrad Med 2014;126:106–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korhonen PE, Seppälä T, Järvenpää S et al. . Body mass index and health-related quality of life in apparently healthy individuals. Qual Life Res 2014;23:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE et al. . Health benefits of gastric bypass surgery after 6 years. JAMA 2012;308:1122–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta T, Fontaine KR, Keith SW et al. . Obesity and mortality: are the risks declining? Evidence from multiple prospective studies in the United States. Obes Rev 2014;15:619–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E et al. . Surgery for weight loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;8:Cd003641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL et al. . Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2013;347:f5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Clinical Guideline CG189. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. Obesity: Identification, Assessment and Management of Overweight and Obesity in Children, Young People and Adults: Partial Update of CG43. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) Copyright (c) National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg 2013;23:427–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welbourn R, Small P, Finlay I et al. . The Second National Bariatric Surgery Registry Report to March 2013. Dendrite Clinical Systems, 2014. ISBN 978-0-9568154-8-4. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welbourn R, Fiennes A, Kinsman R et al. . The UK National Bariatric Surgery Registry. First Report to 2010. Henley-on-Thames UK: Dendrite Clinical Systems Ltd.

- 14.The United Kingdom National Bariatric Surgery Registry. Publication of surgeon-level data in the public domain for bariatric surgery in NHS England. http://www.bomss.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Bariatric_Surgery_Consultant_Outcomes_Publication_30_October_2014.pdf.

- 15.Rogers CA, Welbourn R, Byrne J et al. . The By-Band study: gastric bypass or adjustable gastric band surgery to treat morbid obesity: study protocol for a multi-centre randomised controlled trial with an internal pilot phase. Trials 2014;15:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burton PR, Yap K, Brown WA et al. . Changes in satiety, supra- and infraband transit, and gastric emptying following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a prospective follow-up study. Obes Surg 2011;21:217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore M, Hopkins J, Wainwright P. Primary care management of patients after weight loss surgery. BMJ 2016;352:i945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown W, Korin A, Burton P et al. . Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Aust Fam Physician 2009;38:972–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlin AM, Zeni TM, English WJ et al. . The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg 2013;257:791–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peterli R, Borbely Y, Kern B et al. . Early results of the Swiss Multicentre Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS): a prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg 2013;258:690–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higa K, Ho T, Tercero F et al. . Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2011;7:516–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD et al. . Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007;357:741–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med 2013;273:219–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Angrisani L, Cutolo PP, Formisano G et al. . Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year results of a prospective, randomized trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nguyen NT, Slone JA, Nguyen XM et al. . A prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for the treatment of morbid obesity: outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg 2009;250:631–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puzziferri N, Roshek TB III, Mayo HG et al. . Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA 2014;312:934–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang S, Stoll CT, Song J et al. . The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003–2012. JAMA Surg 2014;149:275–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Brien PE, MacDonald L, Anderson M et al. . Long-term outcomes after bariatric surgery: fifteen-year follow-up of adjustable gastric banding and a systematic review of the bariatric surgical literature. Ann Surg 2013;257:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH et al. . Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA 2013;310:2416–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K et al. . Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 2009;122:248–56.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu J, Zhou X, Li L et al. . The long-term effects of bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized evidence. Obes Surg 2015;25:143–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixon JB, Murphy DK, Segel JE et al. . Impact of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding on type 2 diabetes. Obes Rev 2012;13:57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dixon JB, O'Brien PE, Playfair J et al. . Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008;299:316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edelman S, Ng-Mak DS, Fusco M et al. . Control of type 2 diabetes after 1 year of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the helping evaluate reduction in obesity (HERO) study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014;16:1009–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wentworth JM, Playfair J, Laurie C et al. . Multidisciplinary diabetes care with and without bariatric surgery in overweight people: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:545–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlsson LM, Peltonen M, Ahlin S et al. . Bariatric surgery and prevention of type 2 diabetes in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2012;367:695–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Himpens J, Cadière GB, Bazi M et al. . Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg 2011;146:802–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Kirwan JP et al. . How safe is metabolic/diabetes surgery. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015;17:198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hopkins JC, Howes N, Chalmers K et al. . Outcome reporting in bariatric surgery: an in-depth analysis to inform the development of a core outcome set, the BARIACT Study. Obes Rev 2015;16:88–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sudan R, Nguyen NT, Hutter MM et al. . Morbidity, mortality, and weight loss outcomes after reoperative bariatric surgery in the USA. J Gastrointest Surg 2015;19:171–8, discussion 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karmali S, Brar B, Shi X et al. . Weight recidivism post-bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg 2013;23:1922–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.te Riele WW, Boerma D, Wiezer MJ et al. . Long-term results of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in patients lost to follow-up. Br J Surg 2010;97:1535–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hochberg LS, Murphy KD, O'Brien PE et al. . Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) aftercare attendance and attrition. Obes Surg 2015;25:1693–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sysko R, Hildebrandt TB, Kaplan S et al. . Predictors and correlates of follow-up visit adherence among adolescents receiving laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014;10:914–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aarts EO, Dogan K, Koehestanie P et al. . What happens after gastric band removal without additional bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2014;10:1092–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Padwal R, Klarenbach S, Wiebe N et al. . Bariatric surgery: a systematic review of the clinical and economic evidence. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1183–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weiner JP, Goodwin SM, Chang HY et al. . Impact of bariatric surgery on health care costs of obese persons: a 6-year follow-up of surgical and comparison cohorts using health plan data. JAMA Surg 2013;148:555–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee YY, Veerman JL, Barendregt JJ. The cost-effectiveness of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the morbidly obese adult population of Australia. PLoS One 2013;8:e64965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang BC, Wong ES, Alfonso-Cristancho R et al. . Cost-effectiveness of bariatric surgical procedures for the treatment of severe obesity. Eur J Health Econ 2014;15:253–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borisenko O, Adam D, Funch-Jensen P et al. . Bariatric surgery can lead to net cost savings to health care systems: results from a comprehensive European decision analytic model. Obes Surg 2015;25:1559–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahmad A, Laverty AA, Aasheim E et al. . Eligibility for bariatric surgery among adults in England: analysis of a national cross-sectional survey. JRSM Open 2014;5:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Padwal RS, Chang HJ, Klarenbach S et al. . Characteristics of the population eligible for and receiving publicly funded bariatric surgery in Canada. Int J Equity Health 2012;11:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Persson K. Why Bariatric surgery should be given high priority: an argument from law and morality. Health Care Anal 2014;22:305–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Griffin SM, Raimes SA, Shenfine J. Oesophagogastric surgery. Chapter 20. 5th ed. Saunders Elsevier, 2013. ISBN: 9780702049620. [Google Scholar]