Abstract

Confusion between panic and asthma symptoms can result in serious self-management errors. A cognitive behavior psychophysiological therapy (CBPT) intervention was culturally adapted for Latinos consisting of CBT for panic disorder (PD), asthma education, differentiation between panic and asthma symptoms, and heart rate variability biofeedback. An RCT compared CBPT to music and relaxation therapy (MRT), which included listening to relaxing music and paced breathing at resting respiration rates. Fifty-three Latino (primarily Puerto Rican) adults with asthma and PD were randomly assigned to CBPT or MRT for 8 weekly sessions. Both groups showed improvements in PD severity, asthma control, and several other anxiety and asthma outcome measures from baseline to post-treatment and 3-month follow-up. CBPT showed an advantage over MRT for improvement in adherence to inhaled corticosteroids. Improvements in PD severity were mediated by anxiety sensitivity in CBPT and by depression in MRT, although earlier levels of these mediators did not predict subsequent improvements. Attrition was high (40%) in both groups, albeit comparable to CBT studies targeting anxiety in Latinos. Additional strategies are needed to improve retention in this high-risk population. Both CBPT and MRT may be efficacious interventions for comorbid asthma-PD, and CBPT may offer additional benefits for improving medication adherence.

Keywords: asthma, panic, patient compliance, Latinos, cognitive behavior therapy, relaxation

Asthma and panic disorder (PD) share strikingly similar phenomenology. Respiratory related symptoms, such as dyspnea, dizziness, chest tightness, choking and smothering sensations are common in both disorders. The overlap in symptoms between asthma and panic may lead an individual to mistake a panic attack as an asthma attack. This confusion may then lead to excessive use of rescue medications and further worsen tremor, tachycardia, and anxiety, the common side effects of this medication (Horikawa, Udaka, Crow, Takayama, & Stein, 2014). This may trigger a maladaptive cycle of using rescue medications to treat respiratory anxiety symptoms, mistaken as asthma, thus further increasing feared bodily sensations and panic (Feldman, 2000; Rihmer, 1997). Alternatively, dismissing an asthma attack as a panic attack can have fatal consequences.

PD and asthma occur together in individuals at a high rate. A 20-year longitudinal, community-based study showed that adults with asthma were 4.5 times more likely to develop PD than adults without asthma (Hasler et al., 2005). Conversely, PD is also associated with later development of asthma (Alonso et al., 2014). Patients with asthma and PD have greater health care use related to asthma, poorer asthma quality of life, and greater report of rescue medications than asthma patients without PD, despite no differences on pulmonary function (Feldman, Lehrer, Borson, Hallstrand, & Siddique, 2005). PD in asthma patients is prospectively associated with worse asthma control (Favreau, Bacon, Labrecque, & Lavoie, 2014; Hasler et al., 2005). No prior studies have examined adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) for treatment of asthma in patients with PD. As patients increase adherence to ICS, asthma control should improve and, in turn, anxiety focused on asthma.

Puerto Ricans have the highest asthma prevalence, morbidity and mortality rates for asthma across all other ethnic groups (Akinbami LJ, 2011; NHLBI, 2013). Puerto Ricans with asthma have the highest rate (21%) of PD compared to other ethnic groups, and rates of PD are even higher among Spanish-speaking patients (Feldman et al., 2010). Therefore, Puerto Ricans are the group most at risk for asthma -PD comorbidity and in need of interventions to reduce morbidity of both conditions. However, Latinos and other ethnic minorities have been severely underrepresented in RCTs of PD (Mendoza, Williams, Chapman, & Powers, 2012). Given the unfeasibility of developing treatments that account for all of the cultural diversity in the United States, recommendations suggest drawing from the knowledge base of existing treatments and adapting them to meet the needs of specific racial/ethnic groups (Miranda, Nakamura, & Bernal, 2003).

Special care must be given when treating patients with asthma and PD because what may be therapeutic for one condition can, under some circumstances, worsen the other condition. Certain interoceptive exposure exercises, such as voluntary hyperventilation, may produce airway obstruction in those with asthma (Meuret & Ritz, 2010) due to increased airway cooling effects (Nielsen & Bisgaard, 2005). Patients with asthma are advised to avoid allergens and other airway irritants, whereas patients with PD are advised to expose themselves to triggers for panic, which may be confusing for patients without adequate instruction. The high rate of agoraphobia (Feldman, Lehrer, Borson, Hallstrand, & Siddique, 2005) and phobic avoidance (Yellowlees & Kalucy, 1990) in patients with PD and asthma may have started as appropriate attempts to eliminate asthma triggers (e.g., avoidance of places with cigarette smoke exposure), which then generalized to excessive avoidance behavior due to fear of panic attacks (e.g., avoidance of all public places). Cognitive restructuring for PD is also complicated by the frightening and life-threatening nature of asthma symptoms. For example, potentially catastrophic consequences can occur by mislabeling asthma symptoms as simply being panic-related and engaging in only cognitive restructuring.

Anxiety sensitivity, which measures fearful beliefs about the consequences of anxiety, may be a key construct to target in the treatment of this population. Patients with asthma and PD have greater anxiety sensitivity and fear of bodily sensations than asthma patients without PD (Carr, Lehrer, Rausch, & Hochron, 1994). The physical concerns domain of anxiety sensitivity is associated with worse asthma outcomes including asthma control, quality of life, and pulmonary function (Avallone, McLeish, Luberto, & Bernstein, 2012; McLeish, Luberto, & O’Bryan, 2016). Improvements in PD severity with CBT are mediated by reductions in catastrophic cognitions with the strongest effects linked to physical catastrophic cognitions (Hofmann et al., 2007). Anxiety sensitivity also mediates improvements in PD severity with cognitive therapy (Meuret, Rosenfield, Seidel, Bhaskara, & Hofmann, 2010). Both the physical and cognitive components of anxiety sensitivity are especially relevant to Caribbean Latinos with anxiety. Anxiety sensitivity of these types of experiences predicts the frequency of ataques de nervios, which is a well-known cultural idiom of distress that is more prevalent within this cultural group (Hinton, Lewis-Fernandez, & Pollack, 2009).

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) has shown promising results for the treatment of asthma and PD, although there are limited data in this area. We developed a combined treatment (Feldman, 2000; Lehrer et al., 2008) consisting of asthma education (Kotses et al., 1995; NHLBI, 2007), panic control therapy (Craske & Barlow, 2006), and progressive muscle relaxation (Jacobson, 1938). The treatment was adapted specifically for comorbid asthma-PD by training patients to discriminate between asthma and panic symptoms, aided by the use of a peak flow meter, to use the correct treatment strategy. Participants (n = 10) in an uncontrolled study who received 8 sessions of treatment showed decreases on PD severity and use of rescue medication for asthma, and improvements in asthma symptoms and asthma quality of life (Lehrer et al., 2008). A separate study found that combining group CBT (n = 15) with asthma education was associated with decreases in panic attacks, general anxiety, and anxiety sensitivity in comparison to a wait-list control group (n = 10) at 6-month follow-up, although improvements in asthma outcomes were not maintained (Ross, Davis, & MacDonald, 2005). Asthma patients who completed an individualized asthma program that included cognitive and behavioral techniques reported improvements in self-reported medication adherence across 3-month follow-up compared with a wait list control (Put, van den Bergh, Lemaigre, Demedts, & Verleden, 2003). CBT combined with asthma education has also been shown to reduce illness-specific panic-fear compared to treatment as usual in patients with asthma and high levels of anxiety symptoms (Parry et al., 2012).

In the current trial, we substituted heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback for progressive muscle relaxation due its large effects on improvements on pulmonary function (Lehrer et al., 2004). HRV biofeedback stimulates resonance characteristics of the cardiovascular system caused by a constant rhythm in heart rate and blood pressure due to baroreflex activity (Vaschillo, Lehrer, Rishe, & Konstantinov, 2002). When stimulated by breathing at the resonance frequency, which typically is reflected in oscillations with a frequency between 4.5 and 6.5 cycles per minute, the amplitude of both baroreflex activity and respiratory sinus arrhythmia are greatly increased, and heart rate oscillations move into perfect phase (0 degrees) with breathing (Vaschillo, Lehrer, Rishe, & Konstantinov, 2002). Frequent high-amplitude stimulation of the baroreflex increases baseline baroreflex gain (Lehrer, et al, 2003), thus improving activity in an important reflex that modulates blood pressure, with extension to all autonomic reactivity. Although the exact mechanism by which HRV biofeedback helps asthma has not been demonstrated, theoretical mechanisms include improved respiratory gas exchange efficiency (Hayano, Yasuma, Okada, Mukai, & Fujinami, 1996), stretching of the airways through slower and deeper breathing, decreased tendency to hyperventilate, and reduction of stress and attendant autonomic hyperreactivity (Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014). We will refer to this treatment arm as cognitive behavior psychophysiological therapy (CBPT).

We selected music therapy and paced breathing at each participant’s average respiration rate for the comparison active treatment, hereafter called music relaxation therapy (MRT). The rationale for music therapy was to serve as a non-specific, general relaxation intervention. Paced breathing at participants’ average resting respiration rate provided an active control for HRV biofeedback in order to match the focus on breathing at specific rates in both groups. Listening to self-selected relaxing music following stressors reduces negative emotional states and physiological arousal (Labbe, Schmidt, Babin, & Pharr, 2007). Music therapy has resulted in lower depressive symptoms (Chan, Chan, Mok, Tse, & Yuk, 2009), although no studies have examined the efficacy of music therapy on PD specifically. There are limited data and mixed findings supporting music therapy as a complementary treatment for asthma (Sliwka, Wloch, Tynor, & Nowobilski, 2014).

We hypothesized that participants who received CBPT would display greater reductions in PD severity and improvements in asthma control and ICS adherence at post- treatment and 3-month follow-up. We predicted that improvements in PD severity in the CBPT group would be mediated by reductions in anxiety sensitivity (physical/cognitive concerns).

Methods

Participants

Latino participants with asthma age 18 years and over were recruited between 2010–2012 in the Bronx, NY, via mailings from providers (61.0%), outpatient clinics (15.3%), the emergency room (15.3%), and other sources (e.g., flyers; 8.5%). Inclusion criteria were: (i) DSM-IV criteria for current PD (with or without agoraphobia) and PD Severity Scale (PDSS) rating ≥ 8, which is the optimal cutoff for identification of PD patients while balancing sensitivity and specificity (Shear et al., 2001); (ii) fluency in spoken English or Spanish; and (iii) participants agreed not to make changes in prescribed levels of psychotropic medication for 2 months prior to the study and no changes during the 2 months of the active protocol. Changes to psychotropic medication were assessed at each interview, and no changes were reported. A diagnosis of asthma was confirmed by a board certified pulmonary physician (CS) on the basis of data from medical records and the baseline assessment, and in accordance with national guidelines (NHLBI, 2007). Inclusion criteria for asthma consisted of one of the following: (i) improvement in PEF of ≥ 20% (41.5% reached eligibility on this criterion); (ii) a positive bronchodilator test demonstrated by increase in FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in one second) of 12% or greater and at least 200 ml after inhaling a short acting bronchodilator (34%); (iii) documentation by provider of clinical improvement in asthma symptoms after initiation of anti-inflammatory medication (22.6%); or (iv) positive methacholine challenge test (1.9%).

Exclusion criteria were: (i) evidence of bipolar disorder, psychosis, mental retardation, or organic brain syndrome; (ii) current alcohol or substance abuse/dependence; (iii) history of smoking ≥ 20 pack-years to reduce the possibility of undiagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; (iv) other respiratory disorders; or (v) current participation in psychotherapy for anxiety for less than 6 months. Psychotherapy for more than 6 months was allowed based on the rationale that it was not effectively targeting PD if participants still met criteria.

Design

The study used a mixed design including one between-subjects variable (treatment group) and one within-subjects variable (time). Participants were assigned by a biostatistician (SL) to CBPT or MRT through stratified randomization using a computer generated sequence on the basis of age, gender, language, PD severity, and asthma severity. The assignment of assessors, therapists, and supervisors was balanced between the two groups. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Rutgers University, and CONSORT guidelines were followed. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01583296). Power analyses were based on pilot data (Lehrer et al., 2008) with medium effects estimated for primary outcome measures and a goal of 20 participants per group.

Measures

Translations

English-to-Spanish translation of measures was completed by the Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Einstein and Montefiore. The instruments were reviewed in order to select wording that is common across Latino ethnic groups included in this study. The resulting Spanish version was then translated back to English in order to ensure that all of the items retained their original meaning, repeating such steps if necessary. This process of translation and adaptation was specifically used for instruments that lacked existing Spanish translations with sufficient reliability and validity.

Demographics and asthma severity

Participants reported their ethnicity, nativity, household income, education, marital and employment status, health insurance, and cigarette smoking history. Asthma severity was rated by a pulmonary physician (CS), blinded to treatment group, according to the gold standard national guidelines: intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent (NHLBI, 2007). Asthma severity ratings were based on asthma symptoms, asthma medications, and pulmonary function from spirometry. Severity was based on the most severe level reached across these three categories. Asthma severity at baseline was inferred by the level of medication required to maintain control for participants regularly taking controller medication. Participants were permitted to change their asthma medications during the study, and a pulmonary physician rated the medication step according to national guidelines from each interview. No significant effects were found for group (p = .63), time (p = .57), or group x time (p = .99) on the step of asthma medications that participants were taking.

Panic disorder measures: primary outcomes

Diagnosis of PD was in accordance with DSM-IV criteria, as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Research/Bilingual Version, Patient Edition (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & WIlliams, 2002). Advanced clinical psychology graduate students conducted this semi-structured psychiatric interview and followed guidelines to carefully differentiate between asthma and PD (Feldman, 2000).

The Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS) assessed the severity of PD during the past month (Shear et al., 1997). The PDSS has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.88), good inter-rater and test-retest reliability, and well established convergent and discriminant validity (Shear et al., 2001). The PDSS has 7 clinician-rated items that range in severity from 0 (None) – 4 (Extreme), and the overall mean is reported.

The Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) provided a clinician-rated, categorical definition of treatment responders (Barlow, Gorman, Shear, & Woods, 2000). We used the same PD-based anchors and cutoffs as Barlow et al. (2000) to define a responder as being rated with a score of much improved or better compared with baseline and mild or less on PD severity.

The SCID, PDSS, and CGI interviews were conducted by advanced clinical psychology doctoral students who were blinded to treatment condition. All interviews were videotaped and reviewed by licensed clinical psychologists. Diagnosis of PD and ratings were conducted by interviewers and supervisors, and final ratings were determined by consensus. Inter-rater agreement on PDSS ratings was excellent (ICC = 0.91), and agreement on diagnosis of PD was 92.6% for CBPT and 92.3% for MRT.

The Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3 (ASI-3) is an 18-item measure of beliefs about the consequences of experiencing anxiety symptoms consisting of subscales for physical symptom, cognitive, and social concerns (Taylor et al., 2007). The subscales have good internal consistency (Wheaton, Deacon, McGrath, Berman, & Abramowitz, 2012) and the ASI-physical symptoms subscale is uniquely associated with PD (Olthuis, Watt, & Stewart, 2014). The questions range from 0 (very little) – 4 (very much) and a summary score is calculated for each subscale with higher scores indicating greater anxiety sensitivity. The ASI was examined as a mediator of change in PDSS in the CBPT group.

Asthma measures: primary outcomes

Adherence to ICS medication use was calculated by the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS), a 10-item self-report measure of adherence to controller medications. Both the English and Spanish versions of the MARS have good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity (Cohen et al., 2009). The items range from 1 (always) – 5 (never) with higher scores indicating greater adherence, and a score of ≥ 4.5 is considered good adherence.

The Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) consists of 6 questions assessing asthma symptoms, nighttime awakenings, and use of rescue medication for asthma (Juniper, O’Byrne, Ferrie, King, & Roberts, 2000). An objective measure of pulmonary function is also incorporated into the ACQ by including %FEV1, which was calculated from spirometry (nSpire Health, Longmont, CO) conducted at baseline. The items range from 0–6 with lower scores indicating better asthma control. The English and Spanish versions have excellent internal consistency and construct validity (Juniper, O’Byrne, Guyatt, Ferrie, & King, 1999; Picado et al., 2008). Asthma control was also rated by a pulmonary physician (CS) as well controlled, not well controlled, or very poorly controlled on the basis of asthma symptoms/impairment and pulmonary function.

Secondary measures

The Agoraphobia Cognitions Questionnaire (AGOR) consists of 14 items assessing physical concerns and loss of control during periods of anxiety (Chambless, Caputo, Bright, & Gallagher, 1984). The Body Sensations Questionnaire (BSQ) is a 17-item measure of physical symptoms experienced during anxiety (Chambless, Caputo, Bright, & Gallagher, 1984). Both measures have good reliability, discriminant, and construct validity (Chambless, Caputo, Bright, & Gallagher, 1984). The response scales range from 1 to 5 and the mean score is reported.

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI) is a 21-item scale and the most widely used measure of depression (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). Both the English (Dozois, Ahnberg, & Dobson, 1998) and Spanish versions (Wiebe & Penley, 2005) of the BDI have excellent internal consistency, test-retest reliability, construct validity, and the same factor structure. The items assess depressive symptoms during the past two weeks on a Likert scale ranging from 0–3.

The Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) was administered to assess the impact of asthma on the patient’s quality of life (Juniper, Guyatt, Cox, Ferrie, & King, 1999). Both the English and Spanish versions have high internal consistency and construct validity (Juniper, Guyatt, Cox, Ferrie, & King, 1999; Sanjuas et al., 2001). The response scale ranges from 1 (all the time) – 7 (none of the time) with higher scores indicating better quality of life.

Dosers (MediTrack Products, Hudson, MA) were attached to rescue medications for asthma to assess the frequency of as-needed medication use by participants. Data reduction steps eliminated puffs that reflected outlier values (>12 puffs/day). Use of rescue medication was coded as good asthma control (≤ 2 days/week) or poor control (> 2 days/week) in accordance with national guidelines (NHLBI, 2007). Data were available for 16 of 24 participants in each group.

The credibility/expectancy questionnaire (CEQ) was adapted to focus on treatment of asthma and PD. The CEQ has high internal consistency for both factors and good test-retest reliability (Devilly & Borkovec, 2000).

Physiological measures and devices

Data on heart rate, HRV, respiration rate, and end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) were recorded on a 6-channel I-330-C2+ physiograph device (J&J Engineering, Poulsbo, WA). ECG data were collected from sensors placed on the right and left wrists, and a strain gauge was attached to the participant’s abdominal area to measure respiration rate. ETCO2 was measured by a capnometer (Better Breathing, Boulder, CO) that sampled exhaled gas through a nasal cannula. HRV data were edited using Kubios software (Version 2.1, University of Eastern Finland, MATLAB). Inter-beat-interval (IBI) data were analyzed in the low frequency (LF) band (0.04–0.15 Hz), high frequency (HF) band (0.15–0.4 Hz), and as a ratio (LF/HF).

Procedures

The PD section of the Patient Health Questionnaire (Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999) was administered during recruitment as a brief screening to determine whether to invite participants to the baseline session of SCID interview and the measures described above. The interviews, medication data, and spirometry were collected at baseline, mid-treatment (4 weeks), post-treatment (8 weeks), and 3-month follow-up. Interviewers and therapists who administered the Spanish versions were fluent in Spanish. Participants were instructed to withhold asthma medications prior to spirometry unless medication was needed to treat symptoms, and then appointments were rescheduled.

Focus groups and cultural adaptation of CBPT

We modified our treatment to address cultural characteristics of the Latino population in the Bronx, NY. Five focus groups (3 in English and 2 in Spanish) were conducted with 20 participants with asthma and PD. The qualitative analyses were drawn from a grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The coding process relied on inductively identifying concepts that emerged from the data, involved several members of the research team, and utilized consensus to arrive at final codes and themes. The key themes that emerged included: intense emotional reactions elicited in response to asthma and death of a loved one due to asthma; positive (e.g., caring role, encouraging adherence behaviors) and negative influences (e.g., exposure to asthma triggers, encouraging safety behaviors) of family members on asthma; and mistrust and lack of communication with asthma providers. The culturally adapted treatment was piloted on 5 participants, who provided positive feedback on the intervention and showed improvements on all outcome measures. The next phase involved minor modifications to the manual, such as specific examples for vignettes, and then carrying out the RCT.

Treatment conditions

Therapist manuals and handbooks for participants were prepared for both CBPT and MRT conditions. Both treatments were administered on a weekly basis over 8 weeks. Session content for the original treatment manual for asthma and PD has been previously described (Lehrer et al., 2008). The importance of taking ICS medications was discussed with participants in order to improve asthma control. Medication adherence data were reviewed at the start of each session and feedback was given to participants in a non-judgmental manner with an emphasis on the connections between controller medication use and asthma control. The cultural adaptations included allowing the patient to discuss intense emotional reactions to asthma; vignettes to help patients distinguish between asthma and panic and adaptive versus maladaptive behaviors; a session with a key family member to provide psychoeducation and assistance with carrying out treatment at home; and increasing patient activation and empowerment by improving communication with the asthma provider and the patient’s role in health care decision-making. An electronic peak flow meter (Piko-1, nSpire, CO) was given to CBPT participants to provide a daily measure of peak expiratory flow (PEF) to help these participants distinguish between asthma and panic exacerbations. The StressEraser device was given to CBPT participants for home practice of HRV biofeedback. This device provides electronic monitoring of homework adherence and mastery by displaying more points for greater amplitudes of HRV.

Session content for MRT included supportive but non-directive counseling techniques about patients’ experiences with asthma and panic; listening to relaxing music each session; paced breathing at a respiration rate chosen by participants as being helpful for relaxation. Participants listened to progressively less preferred relaxing music across sessions as they mastered their skills to relax and increase resistance to stress. During the second half of treatment, music therapy and relaxation breathing occurred simultaneously. An MP3 player with musical selections was given to participants for home practice of music therapy.

Therapists and treatment integrity

The therapists included a clinical psychology post-doctoral fellow and advanced graduate students. Extensive training was provided on both treatment manuals as part of a 2-day workshop and followed by weekly 2-hour meetings over 1 month. Weekly supervision was conducted between therapist and supervisor, and all therapy sessions were videotaped. Treatment integrity ratings were conducted on all sessions and based on the treatment manuals to assess the extent to which items were covered during each session. Treatment adherence by participants was assessed at the start of each session by having therapists review whether homework was completed.

Physiological data recordings

Data were collected on physiological measures at 4 sessions. The first session was used to identify each participant’s unique resonance frequency (i.e., respiration rate at which maximum amplitudes in HRV occur) or designated frequency (i.e., respiration rate at which participant felt most relaxed) in the MRT group. Participants in both groups breathed for intervals of 2 minutes at various frequencies by following a pacer. Recordings began with an initial 5-minute plain vanilla baseline task (Jennings, Kamarck, Stewart, Eddy, & Johnson, 1992), followed by a 5-minute period of breathing at resonance or designated frequency. HRV biofeedback followed procedures previously described (Lehrer, Vaschillo, & Vaschillo, 2000). For the MRT group the therapist ensured that the frequency range was between 9 – 18 breaths/minute in order to avoid the low-frequency range of HRV biofeedback and higher respiratory rates at which dyspnea occurs in patients with PD (Wilhelm, Gerlach, & Roth, 2001). Both groups were instructed to practice for 20 minutes twice daily.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed on an intent-to-treat basis using generalized linear mixed model analyses (McCulloch & Searle, 2001) and included all participants who were randomized and started the intervention (n = 24/group). The assumption was that missing data were missing at random (Ibrahim & Molenberghs, 2009). Identity and logit links were used for continuous and categorical dependent measures, respectively. The analyses on psychological and asthma outcome measures included age, gender, and education as covariates. Asthma and PD severity at baseline were covariates except for analyses that included these variables as dependent measures since the baseline time points were already included in the repeated measure. Analyses on HRV data controlled for age, gender, and height. HRV variables and ACQ data were transformed using the natural logarithm. Statistical significance was defined by p-value <0.05. Effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d for continuous measures and (p2-p1)/p1*100% for binary outcomes where p represents the proportion of the sample in each group.

We next examined longitudinal mediational models to determine whether the changes in PDSS scores over time (i.e., the time effect on PDSS scores) were mediated by the time-matched mediators (ASI) and their longitudinal changes using mixed model analyses. The time points for variables included baseline, mid-treatment, post-treatment, and 3-month follow-up. All variables were z-scored to ease the interpretation of the path coefficients. We fitted the following three models following the methodology of Meuret et al. (Meuret, Rosenfield, Hofmann, Suvak, & Roth, 2009): Model 1: Yij= u1i+ μ10+ C1timeij+ C2 timeij2 +e1ij, Model 2: Mij= u2i+ μ20+ a1 timeij+ a2 timeij2 +e2ij, and Model 3: Yij= u3i+ μ30+ C1′timeij+ C2′timeij2 + b Mij+ e3ij; where Yij and Mij represent the outcome and mediation variables of the ith individual at time j, respectively. The coefficients μ’s, C’s, a’s and b represent the regression coefficients corresponding to the intercept, time, time2 and the mediator, respectively, as fixed effects, and u’s represent random effects to account for intra-subject correlations and e’s for random errors. We applied Bonferroni multiple testing: H01: a1b=0 vs. H11: a2b ≠0 and H02: a2b =0 vs. H12: a2b ≠0, each at alpha=2.5% (two-sided) (MacKinnon, Fritz, Williams, & Lockwood, 2007). If 0 was not included in either (or both) 97.5% CI, then we rejected H0 and established the mediation pathway.

We also examined reverse mediation using cross lag panel analyses to assess whether earlier levels of PDSS scores predicted subsequent scores on the mediator (ASI) and vice versa. Ruling out reverse mediation and establishing that changes in the mediator occur before changes in the outcome provide additional support for establishing mediation (Meuret, Rosenfield, Hofmann, Suvak, & Roth, 2009). All analyses were performed in SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

Results

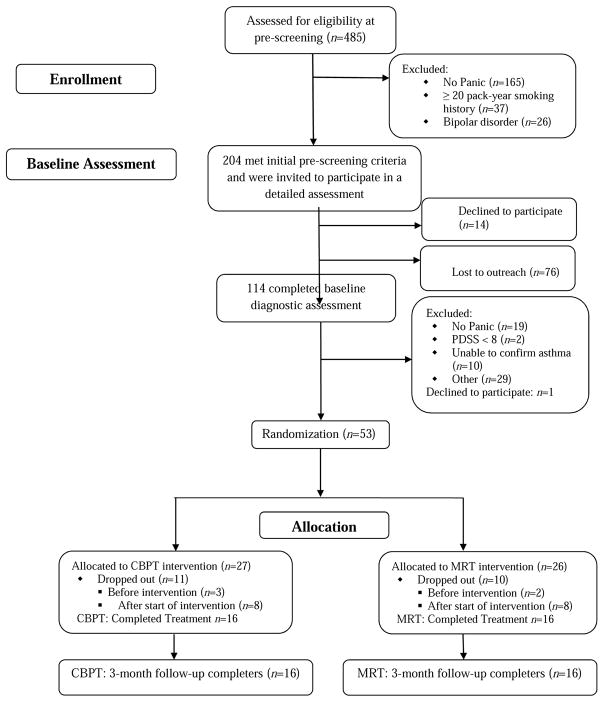

The CONSORT flow chart is presented in Figure 1. Baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The sample was primarily female, Puerto Rican, low-income, unemployed, and on Medicaid or Medicare. The majority of participants had moderate persistent asthma that was not well controlled. No significant differences were found between CBPT and MRT participants on any baseline characteristics. Baseline comparisons between participants who dropped out (n = 21) and completed the 3-month follow-up (n = 32) showed no differences on demographics, PD severity, asthma severity, or asthma control. The most common reason for drop-outs in both groups was due to cell phones being disconnected and back-up contact numbers were not able to be reached. Therefore, missing data are likely missing at random and not related to the intervention. No difference was found between CBPT (40.7%) and MRT (38.5%) groups on the percentage of participants who dropped out from the study,χ2 (1, N = 53) = 0.03, p = .87.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Participants

CBPT = Cognitive Behavior Psychophysiological Therapy; MRT = music relaxation therapy

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by treatment condition

| CBPT (n = 24) | MRT (n = 24) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (± SD) | 43.8 ± 11.8 | 42.6 ± 12.9 | .73 |

| Sex, % (n) female | 91.7 (22) | 95.8 (23) | .55 |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | .14 | ||

| Puerto Rican | 83.3 (20) | 79.2 (19) | |

| Other Latino | 16.7 (4) | 0.8 (5) | |

| Continental US-born,% (n) | .77 | ||

| Yes | 58.3 (14) | 54.2 (13) | |

| No | 41.7 (10) | 45.8 (11) | |

| Household income, % (n) | .31 | ||

| > $16000 | 41.7 (10) | 56.5 (13) | |

| ≤ $16000 | 58.3 (14) | 43.5 (10) | |

| Education, % (n) | .06 | ||

| At least some college | 33.3 (8) | 58.3 (14) | |

| High school | 25.0 (6) | 29.2 (7) | |

| Less than high school | 41.7 (10) | 12.5 (3) | |

| Language preference for treatment, % (n) | .30 | ||

| English | 83.3 (20) | 70.8 (17) | |

| Spanish | 16.7 (4) | 29.2 (7) | |

| Cigarette smoking, % (n) | .54 | ||

| Current smoker | 21.7 (5) | 26.1 (6) | |

| Ex-smoker | 26.1 (6) | 13.0 (3) | |

| Never smoked | 52.2 (12) | 60.9 (14) | |

| Marital status,% (n) | .92 | ||

| Married | 25.0 (6) | 20.8 (5) | |

| Never married | 45.8 (11) | 45.8 (11) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 29.2 (7) | 33.3 (8) | |

| Employment status, % (n) | .99 | ||

| Employed or student | 37.5 (9) | 37.5 (9) | |

| Unemployed | 62.5 (15) | 62.5 (15) | |

| Health Insurance, % (n) | .73 | ||

| Medicaid or Medicare | 87.0 (20) | 83.3 (20) | |

| Other | 13.0 (3) | 16.7 (4) | |

| Taking ICS medication, % (n) | 70.8 (17) | 79.2 (19) | .51 |

| Taking medication for anxiety/depression, % (n) | 52.4 (11) | 45.5 (10) | .65 |

| Asthma severity baseline, % (n) | .88 | ||

| Intermittent/mild persistent | 12.5 (3) | 16.7 (4) | |

| Moderate persistent | 79.2 (19) | 79.2 (19) | |

| Severe persistent | 8.3 (2) | 4.2 (1) | |

| Asthma control, % (n) | .68 | ||

| Well controlled | 12.5 (3) | 16.7 (4) | |

| Not well controlled/very poorly controlled | 87.5 (21) | 83.3 (20) | |

| Panic Disorder with agoraphobia, current % (n) | 87.5 (21) | 79.2 (19) | .44 |

| Major Depressive Disorder, current % (n) | 37.5 (9) | 37.5 (9) | .99 |

Treatment credibility and integrity

Both groups rated their interventions as highly credible (CBPT = 24.03 ± 0.75; MRT = 24.42 ± 0.81) with high expectations for improvement on asthma and panic symptoms (CBPT = 33.37 ± 1.27; MRT = 35.11 ± 1.38). No between-group differences were present. Credibility/expectancy remained high in both groups across mid-treatment and post-treatment with no effect of time. Treatment integrity ratings based on videotaped sessions were very high in both groups (range for CBPT: 88–98%; range for MRT: 91–96%) and no between-group difference was found, F (1, 295) =.42, p = .52.

Primary panic disorder outcome measures

Both groups showed within-group improvements in PDSS from baseline to post-treatment (CBPT, p = .001; MRT, p < .0001), and from baseline to 3-month follow-up (CBPT, p < .0001; MRT, p < .0001). Similar findings emerged on the CGI for treatment responders as both groups showed improvement by post-treatment (CBPT = 30%, MRT = 21%), and a large number were treatment responders by 3-month follow-up (CBPT = 76%, MRT = 62%). Effect size for the % change of responders on CGI from mid-treatment to 3-month follow-up was 898.1% (~ 9 fold increase) for CBPT and 100% for MRT. No between-group differences were found and the group x time interaction was not significant for either measure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Between-group comparisons on psychological measures

| Baseline | Mid | Post | Cohen’s d | 3 MFU | Cohen’s d | Group p | Time p | Group x time p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDSS | .86 | <.0001 | .14 | ||||||

| CBPT | 2.17 (0.16) | 2.13 (0.17) | 1.64 (0.18)*** | −0.84 | 1.21 (0.17)*** | −1.27 | |||

| MRT | 2.40 (0.17) | 1.99 (0.19) | 1.52 (0.19)*** | −1.31 | 1.52 (0.19)*** | −1.19 | |||

| CGI Responder | .91 | .001 | .72 | ||||||

| CBPT (%) | 5.28 (5.13) | 29.97 (11.45) | 75.51 (10.43)** | ||||||

| MRT (%) | 21.93 (10.34) | 21.03 (10.19) | 62.36 (12.11) | ||||||

| ASI Physical | .34 | <.0001 | .33 | ||||||

| CBPT | 16.66 (1.21) | 14.46 (1.34) | 10.39 (1.39)*** | −1.15 | 9.66 (1.33)*** | −0.90 | |||

| MRT | 15.59 (1.29) | 10.88 (1.42) | 9.18 (1.50)*** | −1.05 | 9.29 (1.48)*** | −1.05 | |||

| ASI Cognitive | .005 | <.0001 | .33 | ||||||

| CBPT | 14.27 (1.37) | 13.71 (1.51) | 9.46 (1.58)** | −0.71 | 7.91 (1.51)*** | −0.89 | |||

| MRT | 10.86 (1.45) | 6.50 (1.60) | 4.45 (1.70)*** | −0.86 | 3.07 (1.67)*** | −1.11 | |||

| ASI Social | .12 | <.0001 | .83 | ||||||

| CBPT | 15.49 (1.34) | 14.10 (1.47) | 12.28 (1.52)* | −0.56 | 9.96 (1.46)*** | −0.94 | |||

| MRT | 13.04 (1.43) | 11.75 (1.56) | 8.31 (1.64)** | −0.78 | 7.36 (1.61)*** | −0.80 | |||

| BSQ | .68 | <.0001 | .82 | ||||||

| CBPT | 3.05 (0.18) | 2.67 (0.20) | 2.58 (0.21)* | −0.83 | 2.19 (0.20)*** | −1.20 | |||

| MRT | 2.91 (0.20) | 2.61 (0.21) | 2.35 (0.22)** | −0.68 | 2.21 (0.22)*** | −0.87 | |||

| AGOR | .48 | <.0001 | .34 | ||||||

| CBPT | 2.45 (0.16) | 2.30 (0.17) | 2.12 (0.17)* | −0.50 | 2.01 (0.17)** | −0.66 | |||

| MRT | 2.48 (0.17) | 2.12 (0.18) | 1.93 (0.19)*** | −0.85 | 1.71 (0.18)*** | −1.29 | |||

| BDI | .02 | <.0001 | .11 | ||||||

| CBPT | 24.50 (2.23) | 21.80 (2.46) | 20.09 (2.55) | −0.53 | 15.17 (2.44)*** | −1.09 | |||

| MRT | 21.49 (2.38) | 13.10 (2.61) | 9.35 (2.75)*** | −1.28 | 9.33 (2.71)*** | −1.22 |

Notes. Mean (SE), adjusted values reported

Within-group comparisons are denoted by * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001 and are reported for post-treatment and 3-month follow-up versus baseline except for CGI responder (versus mid-treatment)

Effect sizes reported for within-group change

Primary asthma outcome measures

A group x time interaction was present on ICS adherence measured by the MARS, F (3, 79) = 3.82, p = 0.01 (Table 3). A between-group difference was found when comparing the change in MARS from baseline to post-treatment in CBPT versus MRT (d = .76), p = .017 and from baseline to 3-month follow-up in CBPT versus MRT (d = 1.07), p = .006. The within-group increases on MARS in CBPT were significant from baseline to post-treatment (p < .001) and from baseline to 3-month follow-up (p < .001). The within-group changes on MARS in MRT were not significant. However, MRT reported better adherence at baseline than CBPT (p = .008). No other between-group comparisons on any baseline outcome variables were significant. Although the two groups began at different levels for ICS adherence, the rate of behavior change favored CBPT. These findings on the MARS reflect CBPT closing the gap in these initial baseline differences on adherence across time. The lack of improvement in MRT is not explained by a ceiling effect, as ICS adherence stayed below the cutoff of 4.5 for good adherence (Cohen et al., 2009). Therefore, CBPT appeared to offer an advantage over MRT on improving ICS adherence across time.

Table 3.

Between-group comparisons on asthma variables

| Baseline | Mid | Post | Cohen’s d | 3 MFU | Cohen’s d | Group p | Time p | Group x Time p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARS | .52 | <.0001 | .01 | ||||||

| CBPT | 3.51 (0.17) | 4.39 (0.18) | 4.38 (0.18)*** | 0.96 | 4.43 (0.17) *** | 1.17 | |||

| MRT | 4.15 (0.17) | 4.33 (0.19) | 4.40 (0.20) | 0.47 | 4.37 (0.19) | 0.52 | |||

| ACQ | .47 | <.0001 | .54 | ||||||

| CBPT | 0.85 (0.14) | 0.46 (0.16) | 0.22 (0.17)*** | −0.83 | 0.37 (0.16)** | −0.53 | |||

| MRT | 0.85 (0.15) | 0.73 (0.17) | 0.46 (0.18)* | −0.71 | 0.39 (0.18)** | −0.63 | |||

| %FEV1 | .59 | .0002 | .57 | ||||||

| CBPT | 70.90 (3.48) | 72.84 (3.59) | 75.44 (3.62)* | 0.45 | 73.27 (3.59) | 0.21 | |||

| MRT | 70.73 (3.71) | 76.12 (3.79) | 78.64 (3.86)*** | 0.82 | 77.10 (3.87)** | 0.86 | |||

| AQLQ | .67 | <.0001 | .57 | ||||||

| CBPT | 3.15 (0.27) | 3.96 (0.30) | 4.67 (0.32)*** | 0.93 | 4.69 (0.30)*** | 0.93 | |||

| MRT | 3.36 (0.28) | 3.82 (0.32) | 4.28 (0.34)** | 0.80 | 4.43 (0.33)** | 0.85 | |||

| %Good control, rescue medication | .72 | .19 | .80 | ||||||

| CBPT | 28.99 (10.69) | 49.72 (11.79) | 55.42 (12.83) | 65.15 (11.91)* | |||||

| MRT | 23.24 (9.69) | 55.09 (12.06) | 51.48 (13.36) | 40.02 (12.65) |

Notes. Mean (SE), adjusted values reported

ACQ data represent natural logarithm transformation and lower scores = better control

Within-group comparisons are denoted by * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001 and are reported for post-treatment and 3-month follow-up versus baseline

Effect sizes reported for within-group change

Both groups showed improvements in asthma control (ACQ) from baseline to post-treatment (CBPT, p < .001; MRT, p = .02), and from baseline to 3-month follow-up (CBPT, p = .004; MRT, p = .007). Both groups also showed improvements on %FEV1 from baseline to post-treatment (CBPT, p = .01; MRT, p < .001). However, no between-group differences were found and the group x time interaction was not significant for ACQ or %FEV1.

Secondary outcome measures

Both groups also showed improvements on all other anxiety measures from baseline to post-treatment and 3-month follow-up on the ASI subscales, BSQ, and AGOR (Table 2). Group x time interactions were not significant on any secondary measures. A group effect showed that MRT participants reported overall lower levels on ASI Cognitive and the BDI than CBPT. Both groups displayed significant within-group improvements on the BDI from baseline to 3-month follow-up, although the improvement for MRT participants from baseline to post-treatment was greater than CBPT participants (p = .02, d = .84). Both groups showed within-group improvements on the AQLQ at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up. The effect size for % change on good asthma control defined by rescue medication use at 3-month follow-up versus baseline was 69.1% for CBPT and 44.8% for MRT.

Mediational analyses

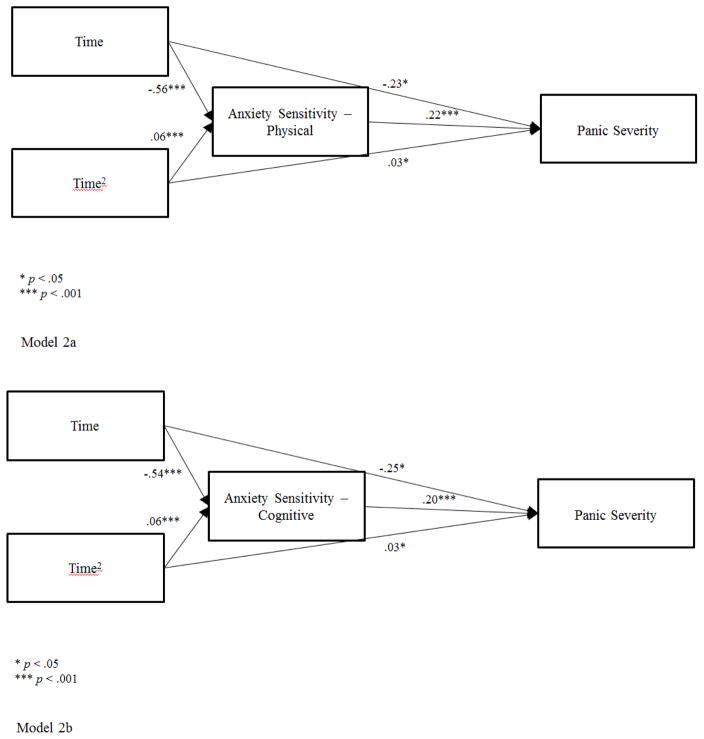

The mediated pathways from time to PDSS through ASI as a time-matched mediator were examined for each treatment group separately. Figure 2 shows that the ASI physical and cognitive scales mediated the changes in PDSS over time in the CBPT group. Consistent with our hypothesis, the mediated pathways over time to PDSS through ASI physical were significant for both the linear trend (Time), a1*b = −.123, 97.5% CI [−.219, −.049], PM (proportion mediated) = .35 and the quadratic trend (Time2), a2*b = .013, 97.5% CI [.005, .025], PM = .30. ASI cognitive was also a significant mediator of changes in PDSS over time in CBPT for the linear trend, a1*b = −.106, 97.5% CI [−.197, −.038], PM = .30 and the quadratic trend, a2*b = .013, 97.5% CI [.004, .024], PM = .28. Findings were not significant for these mediational pathways in MRT. The ASI social scale was not a significant mediator of PDSS for either CBPT or MRT.

Figure 2.

Model 2a. Mediated Pathway for CBPT through Anxiety Sensitivity-Physical subscale

Model 2b. Mediated Pathway for CBPT through Anxiety Sensitivity-Cognitive subscale

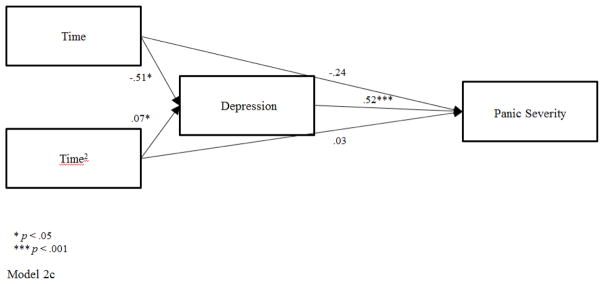

Model 2c. Mediated Pathway for MRT through Depression

Within subject cross lag panel analyses showed stability in the measures in that earlier levels of ASI physical were associated with later levels of ASI physical, bMM = .74, p < .001, and prior PDSS levels predicted later PDSS, bOO = .52, p < .01. Earlier levels of ASI physical were not related to subsequent PDSS scores, bMO = .02, p = .88. Prior levels of PDSS did not predict later levels of ASI physical, bOM = .17, p = .25 (reverse mediation). These analyses show that changes in the outcome (PDSS) did not cause changes in the mediator (ASI physical). However, these data do not support the notion that declines in ASI physical caused subsequent declines in PDSS in the CBPT group and thus, a third variable might explain this directional relationship. Similar findings emerged when examining the relationships between ASI cognitive and PDSS.

Exploratory mediational analyses were conducted for the MRT group and focused on the BDI as a general measure in contrast with the specificity of ASI as a mediator in CBPT. The BDI was selected as a mediator given the significant within group changes with large effects for the BDI in MRT (see Table 2), and based on prior literature showing improvements in depressive symptoms with music therapy (Chan, Chan, Mok, Tse, & Yuk, 2009). The mediated pathways over time to PDSS through BDI were significant for both the linear trend (Time), a1*b = −.263, 97.5% CI [−.576, −.015], PM = .52 and the quadratic trend (Time2), a2*b = .034, 97.5% CI [0, .008], PM = .50. These findings for BDI as a mediator were specific to MRT only, as BDI was not a mediator in CBPT analyses. Within-subject cross lag panel analyses in MRT showed that earlier levels of BDI were associated with later levels of BDI, bMM = .42, p < .05. Earlier levels of BDI were not related to later levels of PDSS, bMO = −.22, p = .12, and prior levels of PDSS did not predict subsequent levels of BDI, bOM = .12, p = .43 (reverse mediation). Although the BDI was a mediator of change across time in PDSS for the MRT group when examined as a time-matched mediator, the BDI did not predict later improvements in PD severity.

Psychophysiological measures

Analyses on psychophysiological data provided evidence of treatment fidelity for HRV biofeedback (Table 4). The CBPT group showed large increases within each biofeedback session on LF and the LF/HF ratio, and decreases in respiration rate from baseline to HRV biofeedback. No changes were seen on these measures in MRT during music/relaxation breathing, which confirms that CBPT participants were properly trained to alter these psychophysiological parameters during the sessions. ETCO2 was not specifically targeted in either group and, thus no within-group or between-group differences were seen.

Table 4.

Between-group comparisons on psychophysiological variables at first and last treatment sessions

| Baseline session | Session 7 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Baseline | HRV or MRT Breathing | Cohen’s d | Within Group p | Between Group p | Baseline | HRV or MRT breathing | Cohen’s d | Within Group p | Between Group p | Group x Task p | |

| LF | |||||||||||

| CBPT | 5.87 (0.54) | 7.53 (0.57) | 2.14 | .0001 | .003 | 6.33 (0.56) | 7.71 (0.56) | 1.03 | .0004 | .01 | <0.0001 |

| MRT | 5.87 (0.54) | 5.95 (0.55) | -0.07 | .81 | 6.15 (0.55) | 6.22 (0.55) | 0.06 | .82 | |||

| LF/HF Ratio | |||||||||||

| CBPT | 0.14 (0.37) | 1.76 (0.41) | 1.55 | .0002 | .008 | 0.35 (0.39) | 1.47 (0.40) | 0.71 | .003 | .17 | .003 |

| MRT | 0.09 (0.37) | 0.25 (0.39) | 0.06 | .62 | 0.31 (0.39) | 0.74 (0.39) | 0.35 | .23 | |||

| Respiration Rate | |||||||||||

| CBPT | 15.64 (0.95) | 8.80 (1.11) | −1.46 | .00001 | .0006 | 13.60 (1.01) | 9.10 (1.05) | −0.90 | .0003 | .02 | <.0001 |

| MRT | 16.43 (0.97) | 15.64 (1.05) | −0.29 | .42 | 15.71 (1.06) | 15.01 (1.06) | −0.26 | .49 | |||

| ETCO2 | |||||||||||

| CBPT | 36.55 (1.24) | 34.62 (1.54) | −0.60 | .23 | .93 | 35.23 (1.36) | 33.74 (1.42) | −0.20 | .33 | .53 | .60 |

| MRT | 33.40 (1.30) | 31.65 (1.35) | −0.35 | .21 | 33.59 (1.44) | 33.45 (1.44) | −0.05 | .93 | |||

Notes. Mean (SE)

Adjusted values and natural logarithm transformation reported

Effect sizes reported for within-group change

Discussion

Both CBPT and MRT improved on several measures of PD, anxiety, and asthma outcomes at post-treatment and 3-month follow-up. CBPT had an advantage over MRT on improvement in ICS medication adherence assessed by self-report, but did not outperform MRT on panic outcomes. Mediational analyses showed that the effect of CBPT on improvement in PD severity across time was mediated by time-matched anxiety sensitivity, and depression mediated improvements in PD severity in MRT. However, support was not found for earlier levels of these mediators predicting later points of PD severity. Overall these findings suggest that both interventions may hold promise in treating asthma-PD comorbidity in a high-risk, ethnic minority population.

The improvement in PD with large effects in the current study, in both conditions, contrasts with the very low natural recovery rate. A prospective, observational study showed that Latinos with PD and agoraphobia are unlikely to recover naturally (.03 probability) during a 2-year follow-up, which is much lower than rates previously reported for non-Latino Whites (Bjornsson et al., 2014). The fact that both CBPT and MRT showed improvement, during a much smaller observation period, points to the likely benefit of both treatments. One other CBT study of anxiety in Latinos reported a 63% treatment response rate at 6-month follow-up, although improvements on secondary measures of anxiety were not significant (Chavira et al., 2014). The rate of treatment responders in the present study was 76% at 3-month follow-up in CBPT, and medium-large effects were present on all secondary measures of anxiety. These improvements occurred despite this Latino sample’s high severity of PD symptoms, low functioning, and a psychosocial environment characterized by chronic stressors. The large changes across time may also reflect that there was much room for improvement on measures due to low levels reported at baseline. Agoraphobic avoidance has been identified as the most consistent predictor of poorer outcomes in response to CBT (Porter & Chambless, 2015) and our sample had a very high rate of agoraphobia (CBPT=87.5%, MRT=79.2%). Major depressive disorder was also highly comorbid (37.5%) with moderate depression levels on the BDI at baseline. In summary, the current improvements exceeded those observed in the natural course of illness among Latinos with PD, and occurred despite comorbidities that typically predict poorer outcomes, thereby supporting the value of both behavioral treatments.

The advantage of CBPT over MRT for improvements in adherence to ICS medications is consistent with other studies showing the potential for CBT to improve adherence with disease management across follow-up. A brief motivational interviewing intervention improved adherence to ICS across 6-month follow-up for individuals with poorly controlled asthma (Lavoie et al., 2014). CBT has also demonstrated improvements in medication adherence and disease markers among individuals with type 2 diabetes and depression (Safren et al., 2014) and HIV/AIDS and depression (Safren et al., 2009), including one study that culturally adapted CBT for Latinos (Simoni et al., 2013). The present study extends these findings to Latinos with asthma that CBT has a large effect size in improving and maintaining medication adherence across 3-month follow-up.

The cultural adaptations in the present study may have contributed to the improvements in medication adherence, including increasing patient empowerment in health care decision-making through a variety of elements. These included writing down questions to ask providers prior to visits, discussing all treatments with providers including complementary and alternative medications, and assertiveness training in communicating with providers who are typically viewed as being in a position of authority. An intervention study focused on minority patients from outpatient mental health clinics similarly found that these techniques increase patient activation (i.e., active participation in health care decision making) but not engagement or retention in care (Alegría et al., 2014). Mistrust and lack of communication with providers was identified as a key theme during the focus groups in the present study. Therefore, interactions with health care providers might be one module that is of particular utility to patients from racial/ethnic groups who experience disparities in the management of chronic disease. Nevertheless, this study did not directly compare culturally adapted and unadapted CBT, making it unclear if improvements in adherence would have occurred with the original CBT protocol (Lehrer et al., 2008).

The lack of significant group differences on most outcome measures may be attributed to the stringent comparison to another active treatment. There is evidence that music therapy and greater attention to breathing might offer therapeutic benefits. Patients with mild asthma who received music therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation showed greater improvements in pulmonary function compared with patients who only received pulmonary rehabilitation (Sliwka, Nowobilski, Polczyk, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka, & Szczeklik, 2012). A separate asthma study showed that listening to music led to reductions in tension ratings, but had no effect on pulmonary function, asthma symptoms, medication consumption, or health care use (Lehrer et al., 1994). Music therapy has been shown to reduce anxiety across several types of medical populations including patients with pulmonary conditions requiring mechanical ventilator support (Wong, Lopez-Nahas, & Molassiotis, 2001), cardiac patients (Buffum et al., 2006), and cancer patients (Mason & Silverman, 2014). Music may reduce anxiety by decreasing physiological arousal including respiration rate, blood pressure, and heart rate (White, 1999). Slow breathing in asthma patients with greater attention focused on the breath led to improvements in asthma control, lung function, and quality of life across 6-month follow-up (Ritz, Rosenfield, Steele, Millard, & Meuret, 2014). The paced breathing aspect of MRT deprived PD patients of the regulatory process of respiration, which may have inadvertently contributed to an element of exposure therapy for this group.

The mediators of change in this study were consistent with the expected pathways for achieving reductions in PD severity in CBPT. Large effects were found in the present study with anxiety sensitivity accounting for 28–35% of the proportion of change in PD severity. Even larger effects were found in MRT for depressive symptoms mediating change in PD severity with approximately 50% explained variance. MRT may operate through more nonspecific, general pathways of mood and negative affect. The music and relaxed breathing in this study may have allowed a highly stressed population to simply take a break from the multitude of life stressors and provided behavioral activation by engaging in an activity that provided positive reinforcement in the form of pleasure. However, both CBPT and MRT only met half of the requirements for establishing a directional and temporal sequence of mediational pathways. Further research is needed to establish multimediator models that take into account other variables.

The main limitations of this study were the small sample size and high drop-out rate (40%), although this rate was not different between the two groups and similar to the attrition rate (36%) reported in a separate CBT study for anxiety in Latinos (Chavira et al., 2014). Retention of participants in this high-risk, inner-city sample was challenging given the continuous stressors that interfered with participation. Nevertheless, all participants who completed the 8 weeks of treatment remained in the study across the 3-month follow-up. Medication adherence was targeted in the CBPT group and the significant findings that emerged on the MARS could be due to recall bias or social desirability effects. The MARS was not applicable to 25% of participants who were not taking ICS medications. Advances are needed to improve electronic monitoring devices that can track all ICS medications. The use of %FEV1 as the sole measure of pulmonary function was limited by its snapshot measure of asthma control at a particular moment in time, and future studies should include additional measures (e.g., daily PEF, exhaled nitric oxide). Finally, the findings of this study are specific to a narrow sample of Latinos (primarily Puerto Rican) with asthma and PD, and findings may not generalize to other Latino subgroups.

This is the first study of CBT for Latinos with asthma and PD. More research is needed with larger samples and longer follow-up to conclude which intervention is the most effective in treatment of PD in Latinos with asthma. In order to increase generalizability, studies are needed with other ethnic minority groups and a broader sample of anxiety patients with medical comorbidity. Future studies should examine whether CBPT can integrate interventions to increase ETCO2 given hypocapnic levels at times in the present sample, and demonstrated efficacy of capnometry-assisted respiratory training for improving asthma control (Ritz, Rosenfield, Steele, Millard, & Meuret, 2014) and PD symptom severity (Meuret, Rosenfield, Seidel, Bhaskara, & Hofmann, 2010). A key question for future research is whether combined approaches of medical disease self-management and CBT for anxiety disorders are necessary, or if current evidence-based treatments for anxiety disorders can be applied broadly across medical populations as well as ethnic minorities.

Latinos improved on panic disorder severity and asthma control in both groups.

CBT had greater improvements on asthma medication adherence than music-relaxation.

Improvements in panic disorder severity were mediated by anxiety sensitivity in CBT.

Depression was a mediator of change in panic disorder severity in music-relaxation.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health: 1R34MH087679, PI: Jonathan M. Feldman, Ph.D. Spanish translation of measures was funded by the Einstein-Montefiore ICTR 5UL-1TR001073-02. We would like to thank Dr. Melissa D. McKee, Ms. Claudia Lechuga, and the New York City Research and Improvement Networking Group for their assistance with recruitment of participants. We also acknowledge the cooperation from the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, Jacobi Medical Center, and Montefiore Medical Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akinbami LJ, MJ, Liu X. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005–2009. Hyattsville, MD: 2011. (National health statistics reports; no 32) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Carson N, Flores M, Li X, Shi P, Lessios AS, … Interian A. Activation, self-management, engagement, and retention in behavioral health care: a randomized clinical trial of the DECIDE intervention. JAMA psychiatry. 2014;71(5):557–565. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso J, de Jonge P, Lim CC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, … Scott KM. Association between mental disorders and subsequent adult onset asthma. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;59:179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avallone KM, McLeish AC, Luberto CM, Bernstein JA. Anxiety sensitivity, asthma control, and quality of life in adults with asthma. Journal of Asthma. 2012;49(1):57–62. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.641048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods SW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(19):2529–2536. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsson AS, Sibrava NJ, Beard C, Moitra E, Weisberg RB, Benitez CI, Keller MB. Two-year course of generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder with agoraphobia in a sample of Latino adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(6):1186–1192. doi: 10.1037/a0036565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffum MD, Sasso C, Sands LP, Lanier E, Yellen M, Hayes A. A music intervention to reduce anxiety before vascular angiography procedures. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 2006;24(3):68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr RE, Lehrer PM, Rausch LL, Hochron SM. Anxiety sensitivity and panic attacks in an asthmatic population. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1994;32(4):411–418. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Caputo GC, Bright P, Gallagher R. Assessment of fear of fear in agoraphobics: the body sensations questionnaire and the agoraphobic cognitions questionnaire. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984;52(6):1090–1097. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.6.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MF, Chan EA, Mok E, Tse K, Yuk F. Effect of music on depression levels and physiological responses in community-based older adults. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2009;18(4):285–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavira DA, Golinelli D, Sherbourne C, Stein MB, Sullivan G, Bystritsky A, … Craske M. Treatment engagement and response to CBT among Latinos with anxiety disorders in primary care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(3):392–403. doi: 10.1037/a0036365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JL, Mann DM, Wisnivesky JP, Home R, Leventhal H, Musumeci-Szabo TJ, Halm EA. Assessing the validity of self-reported medication adherence among inner-city asthmatic adults: the Medication Adherence Report Scale for Asthma. Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. 2009;103(4):325–331. doi: 10.1016/s1081-1206(10)60532-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of your anxiety and panic: Therapist guide. 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2000;31(2):73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Ahnberg JL, Dobson KS. Psychometric Evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10(2):83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Favreau H, Bacon SL, Labrecque M, Lavoie KL. Prospective impact of panic disorder and panic-anxiety on asthma control, health service use, and quality of life in adult patients with asthma over a 4-year follow-up. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2014;76(2):147–155. doi: 10.1097/psy.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JM, Giardino ND, Lehrer PM. Asthma and panic disorder. In: Mostofsky DI, Barlow DH, editors. The Management of Stress and Anxiety in Medical Disorders. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2000. pp. 220–239. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JM, Lehrer PM, Borson S, Hallstrand TS, Siddique MI. Health care use and quality of life among patients with asthma and panic disorder. Journal of Asthma. 2005;42(3):179–184. doi: 10.1081/JAS-200054633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JM, Mayefsky L, Beckmann L, Lehrer PM, Serebrisky D, Shim C. Ethnic differences in asthma-panic disorder comorbidity. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.002. S0091-6749(09)01639-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler G, Gergen PJ, Kleinbaum DG, Ajdacic V, Gamma A, Eich D, … Angst J. Asthma and panic in young adults: a 20-year prospective community study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;171(11):1224–1230. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1669OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayano J, Yasuma F, Okada A, Mukai S, Fujinami T. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia a phenomenon improving pulmonary gas exchange and circulatory efficiency. Circulation. 1996;94(4):842–847. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.4.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton DE, Lewis-Fernandez R, Pollack MH. A model of the generation of ataque de nervios: the role of fear of negative affect and fear of arousal symptoms. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009;15(3):264–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2009.00101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Meuret AE, Rosenfield D, Suvak MK, Barlow DH, Gorman JM, … Woods SW. Preliminary evidence for cognitive mediation during cognitive-behavioral therapy of panic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(3):374–379. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.374. 2007-07856-003 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikawa YT, Udaka TY, Crow JK, Takayama JI, Stein MT. Anxiety associated with asthma exacerbations and overuse of medication: the role of cultural competency. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2014;35(2):154–157. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0000000000000029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim JG, Molenberghs G. Missing data methods in longitudinal studies: a review. Test. 2009;18(1):1–43. doi: 10.1007/s11749-009-0138-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson E. Progressive relaxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings JR, Kamarck T, Stewart C, Eddy M, Johnson P. Alternate cardiovascular baseline assessment techniques: vanilla or resting baseline. Psychophysiology. 1992;29(6):742–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1992.tb02052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Cox FM, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of the Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. European Respiratory Journal. 1999;14(1):32–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14a08.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juniper EF, O’Byrne PM, Ferrie PJ, King DR, Roberts JN. Measuring asthma control. Clinic questionnaire or daily diary? American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2000;162(4 Pt 1):1330–1334. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9912138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juniper EF, O’Byrne PM, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, King DR. Development and validation of a questionnaire to measure asthma control. European Respiratory Journal. 1999;14(4):902–907. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d29.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotses H, Bernstein IL, Bernstein DI, Reynolds RV, Korbee L, Wigal JK, … Creer TL. A self-management program for adult asthma. Part I: Development and evaluation. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 1995;95(2):529–540. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe E, Schmidt N, Babin J, Pharr M. Coping with stress: the effectiveness of different types of music. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2007;32(3–4):163–168. doi: 10.1007/s10484-007-9043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie KL, Moullec G, Lemiere C, Blais L, Labrecque M, Beauchesne MF, … Bacon SL. Efficacy of brief motivational interviewing to improve adherence to inhaled corticosteroids among adult asthmatics: results from a randomized controlled pilot feasibility trial. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1555–1569. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s66966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer PM, Gevirtz R. Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Front Psychol. 2014;5:756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer PM, Hochron SM, Mayne T, Isenberg S, Carlson V, Lasoski AM, … Rausch L. Relaxation and music therapies for asthma among patients prestabilized on asthma medication. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;17(1):1–24. doi: 10.1007/BF01856879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer PM, Karavidas MK, Lu SE, Feldman J, Kranitz L, Abraham S, … Reynolds R. Psychological treatment of comorbid asthma and panic disorder: A pilot study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(4):671–683. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.07.001. S0887-6185(07)00152-1 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer PM, Vaschillo E, Vaschillo B. Resonant frequency biofeedback training to increase cardiac variability: rationale and manual for training. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2000;25(3):177–191. doi: 10.1023/a:1009554825745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer PM, Vaschillo E, Vaschillo B, Lu SE, Scardella A, Siddique M, Habib RH. Biofeedback treatment for asthma. Chest. 2004;126(2):352–361. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(3):384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason GJ, Silverman MJ. Immediate Effects of Single-Session Music Therapy on Affective State in Patients on a Post-Surgical Oncology Unit: A Randomized Effectiveness Study. The Arts in Psychotherapy 2014 [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch CE, Searle SR. Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York measures. In: Scheiner SM, Gurevitch J, editors. Design and Analysis of Ecological Experiments. Chapman & Hall; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McLeish AC, Luberto CM, O’Bryan EM. Anxiety Sensitivity and Reactivity to Asthma-Like Sensations Among Young Adults With Asthma. Behavior Modification. 2016;40(1–2):164–177. doi: 10.1177/0145445515607047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza DB, Williams MT, Chapman LK, Powers M. Minority inclusion in randomized clinical trials of panic disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26(5):574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuret AE, Ritz T. Hyperventilation in panic disorder and asthma: empirical evidence and clinical strategies. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2010;78(1):68–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuret AE, Rosenfield D, Hofmann SG, Suvak MK, Roth WT. Changes in respiration mediate changes in fear of bodily sensations in panic disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43(6):634–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuret AE, Rosenfield D, Seidel A, Bhaskara L, Hofmann SG. Respiratory and cognitive mediators of treatment change in panic disorder: evidence for intervention specificity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(5):691. doi: 10.1037/a0019552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Nakamura R, Bernal G. Including ethnic minorities in mental health intervention research: a practical approach to a long-standing problem. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2003;27(4):467–486. doi: 10.1023/b:medi.0000005484.26741.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHLBI. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MA: 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHLBI. Hispanic community health study data book: a report to the communities. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen KG, Bisgaard H. Hyperventilation with cold versus dry air in 2- to 5-year-old children with asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;171(3):238–241. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-528OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olthuis JV, Watt MC, Stewart SH. Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI-3) subscales predict unique variance in anxiety and depressive symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28(2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry GD, Cooper CL, Moore JM, Yadegarfar G, Campbell MJ, Esmonde L, … Hutchcroft BJ. Cognitive behavioural intervention for adults with anxiety complications of asthma: prospective randomised trial. Respiratory Medicine. 2012;106(6):802–810. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picado C, Badiola C, Perulero N, Sastre J, Olaguibel JM, Lopez Vina A, Vega JM. Validation of the Spanish version of the Asthma Control Questionnaire. Clinical Therapeutics. 2008;30(10):1918–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.10.005. S0149-2918(08)00326-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter E, Chambless DL. A systematic review of predictors and moderators of improvement in cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder and agoraphobia. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;42:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Put C, van den Bergh O, Lemaigre V, Demedts M, Verleden G. Evaluation of an individualised asthma programme directed at behavioural change. European Respiratory Journal. 2003;21(1):109–115. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00267003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihmer Z. Successful treatment of salbutamol-induced panic disorder with citalopram. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;7(3):241–242. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(97)00408-2. S0924-977X(97)00408-2 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz T, Rosenfield D, Steele AM, Millard MW, Meuret AE. Controlling asthma by training of capnometry-assisted hypoventilation (CATCH) vs slow breathing: a randomized controlled trial. CHEST Journal. 2014;146(5):1237–1247. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CJ, Davis TM, MacDonald GF. Cognitive-behavioral treatment combined with asthma education for adults with asthma and coexisting panic disorder. Clinical Nursing Research. 2005;14(2):131–157. doi: 10.1177/1054773804273863. 14/2/131 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Wexler DJ, Psaros C, Delahanty LM, Blashill AJ, … Cagliero E. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(3):625–633. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, Mayer KH. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychology. 2009;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjuas C, Alonso J, Ferrer M, Curull V, Broquetas JM, Anto JM. Adaptation of the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire to a second language preserves its critical properties: the Spanish version. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2001;54(2):182–189. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Money R, Sholomskas DE, Woods SW, … Papp LA. Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(11):1571–1575. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Rucci P, Williams J, Frank E, Grochocinski V, Vander Bilt J, … Wang T. Reliability and validity of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale: replication and extension. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2001;35(5):293–296. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(01)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Wiebe JS, Sauceda JA, Huh D, Sanchez G, Longoria V, … Safren SA. A preliminary RCT of CBT-AD for adherence and depression among HIV-positive Latinos on the U.S.-Mexico border: the Nuevo Dia study. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(8):2816–2829. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0538-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwka A, Nowobilski R, Polczyk R, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Szczeklik A. Mild asthmatics benefit from music therapy. Journal of Asthma. 2012;49(4):401–408. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.663031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwka A, Wloch T, Tynor D, Nowobilski R. Do asthmatics benefit from music therapy? A systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2014;22(4):756–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, Deacon B, Heimberg RG, Ledley DR, … Cardenas SJ. Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(2):176–188. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaschillo E, Lehrer P, Rishe N, Konstantinov M. Heart rate variability biofeedback as a method for assessing baroreflex function: a preliminary study of resonance in the cardiovascular system. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2002;27(1):1–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1014587304314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton MG, Deacon BJ, McGrath PB, Berman NC, Abramowitz JS. Dimensions of anxiety sensitivity in the anxiety disorders: evaluation of the ASI-3. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2012;26(3):401–408. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]