Abstract

Objective

To compare the methods and baseline characteristics of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) and Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) studies.

Background

The AMPP and CaMEO studies are the largest longitudinal efforts designed to improve our understanding of episodic and chronic migraine in the United States. The studies have complementary strengths and weaknesses.

Methods

This analysis compares and contrasts the study methods and participation rates of the AMPP and CaMEO studies. We then compare and contrast baseline results in terms of demographic characteristics, headache features, and disability as measured by the Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS) among people with episodic and chronic migraine.

Results

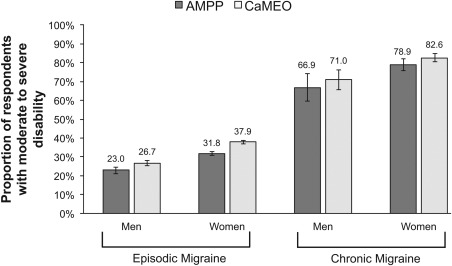

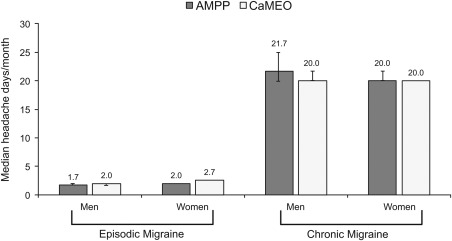

AMPP and CaMEO sampled from panels constructed to be representative of the US population. The AMPP Study collected data using a mailed questionnaire while CaMEO relied on a web survey methodology. Response rates were higher in AMPP (64.8%) than in CaMEO (16.5%). Both studies assessed headache features using the American Migraine Study/AMPP diagnostic module. Both identified persons with episodic (<15 headache days/month) and chronic migraine (≥15 headache days/month) based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders. AMPP collected data annually over 5 years, while CaMEO collected data quarterly over 15 months. Baseline demographic distribution was generally similar, indicating that each study was broadly representative of the US population. The proportion of persons with migraine who had chronic migraine was similar (AMPP, 6.6%; CaMEO, 8.8%). Respondents had similar median headache frequency (days/month) by sex for chronic migraine (AMPP: men = 21.7, women = 20.0; CaMEO: men = 20.0, women = 20.0) and episodic migraine (AMPP: men = 1.7, women = 2.0; CaMEO: men = 2.0, women = 3.0). Median MIDAS scores were substantially higher in both studies for chronic migraine (severe disability [Grade IV]; AMPP: men = 33.0, women = 45.0; CaMEO: men = 32.0, women = 38.0) than episodic migraine (little/mild disability [Grade I/II]; AMPP: men = 3.0, women = 6.0; CaMEO: men = 4.0, women = 7.0). Rates of moderate/severe disability (Grade III/IV) were substantially higher in both studies for chronic migraine (AMPP: men = 66.9%, women = 78.9%; CaMEO: men = 71.0%, women = 82.6%) than episodic migraine (AMPP: men = 23.0%, women = 31.8%; CaMEO: men = 26.7%, women = 37.9%). More women than men respondents in both studies experienced moderate/severe disability.

Conclusions

AMPP and CaMEO are longitudinal cohort studies that used different methods, but yielded similar results for demographic features, headache frequency, and headache‐related disability. Both studies found more severe headache‐related disability in those with chronic versus episodic migraine.

Keywords: episodic migraine, chronic migraine, epidemiology, headache‐related disability, headache‐day frequency, demographics

Abbreviations

- AMPP

American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study

- AMS

American Migraine Study

- CaMEO

Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes Study

- CM

chronic migraine

- EM

episodic migraine

- IBMS

International Burden of Migraine Study

- ICHD

International Classification of Headache Disorders

- MIDAS

Migraine Disability Assessment questionnaire

Many people with migraine do not consult clinicians or receive treatment with prescription drugs, and among those who do seek care, <15% consult neurologists or headache specialists.1, 2 As a consequence, clinic‐based studies that rely on clinician diagnosis miss a substantial proportion of people with migraine and identify a sample with more severe disease and better access to medical care.2 Therefore, studies that systematically ascertain disease‐state status in more representative non‐clinic samples are essential for increasing awareness and understanding of health conditions, such as migraine. Insights gained from these studies can document healthcare utilization and unmet diagnosis and treatment needs. Ultimately, these studies provide essential evidence for interventions designed to improve patient care and clinical outcomes.3‐11 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study,12 conducted from 2004 to 2009, provided benchmark data for describing migraine prevalence, sociodemographic profiles, burden, comorbidity patterns, and prognosis. The AMPP Study also reported health‐related outcomes from the perspective of the person with migraine. The more recent Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study,13 conducted from 2012 to 2013, expanded upon findings from the AMPP Study by providing a larger sample of persons with chronic migraine (CM), sampling headache frequency and disability every 3 months instead of annually, assessing impact of migraine on families from the perspective of different family members, and evaluating barriers to medical care for persons with migraine. Finally, the CaMEO Study sought to describe the relationship of migraine with underlying endophenotypes defined based on an expanded set of comorbidities and symptom profiles.

Differences in study methods, response rates, and sample sizes may raise questions about the representativeness of the CaMEO Study findings in comparison with findings from the more widely published AMPP Study. Because the AMPP Study had a much higher response rate (64.8% to the brief initial survey and 77.1% to the subsequent baseline longitudinal survey) and a large sample (162,576 respondents to the initial survey), data are more verifiably representative of the US migraine population. CaMEO had a lower response rate (16.5%), raising concerns about potential bias. We conducted this analysis to compare and contrast methodology and sample characteristics (sociodemographic, features, headache‐day frequency, headache‐related disability) in the AMPP and CaMEO studies. These results provide a context to better understand the results of the CaMEO Study.

METHODS

Study Design

Details of the methods used by the AMPP and CaMEO studies have been published previously12‐14 12, 13, 14 and are contrasted in Table 1. Briefly, the AMPP Study was based on the methods used in the American Migraine Study (AMS) and consisted of 2 phases; phase 1 began in 2004 and identified individuals with self‐reported severe headache in a stratified random sample of 120,000 households selected to be representative of the US population. Phase 2 began in 2005 and used mail surveys to determine headache features, treatment patterns, and comorbidities. The CaMEO Study was a web‐based study that used quota sampling to recruit a demographically representative sample of individuals in the United States. Cross‐sectional and longitudinal CaMEO Study modules were administered from September 2012 to November 2013. Both studies were approved by the institutional review board of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the AMPP and CaMEO Studies

| AMPP | CaMEO | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample source | Research panel of households | Research panel of individuals |

| Data collection method | Mailed questionnaire | Web‐based survey |

| Sampling method | Demographically representative panel | Quota sampling from a demographically representative panel |

| Study design | Longitudinal study with cross‐sectional surveys | Longitudinal study with cross‐sectional surveys |

| Baseline study year | 2005 | 2012 |

| Duration | Annually over 5 years | Quarterly over 15 months |

| Cases screened | Severe headache | Headache |

| Survey response rate, % | 64.8/77.1* | 16.5 |

| Diagnostic criteria | Modified ICHD‐2† | Modified ICHD‐3 beta |

| Diagnosis ascertained by | AMS/AMPP diagnostic module15, 16 | AMS/AMPP diagnostic module15, 16 |

| Baseline migraine sample size, n | 12,043 | 16,789 |

| CM, n (%) | 794 (6.6) | 1,476 (8.8) |

| EM, n (%) | 11,249 (93.4) | 15,313 (91.2) |

| Data focus | Headache‐day frequency | Headache‐day frequency |

| Disability | Disability | |

| Healthcare utilization | Healthcare utilization | |

| Medication use | Medication use | |

| Diagnosis rates | Treatment satisfaction | |

| Headache severity | Barriers to medical care | |

| Allodynia | Comorbidities | |

| Lost productivity | Quality of life | |

| Comorbidities | Family burden |

*The response rate to the initial household screening study was 64.8%, and response to the baseline longitudinal study was 77.1%.

†Only ICHD‐2 symptom criteria were available in 2005; however, ICHD‐2 and ICHD‐3 beta are similar with respect to symptom criteria and case selection for migraine. Inclusion criteria are considered a modification of ICHD‐3 beta because 2 criteria were not confirmed: ≥5 lifetime migraine events (criterion A) and duration of attack untreated from 4–72 hours (criterion B).

AMPP, American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention; CaMEO, Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes; CM, chronic migraine; EM, episodic migraine; ICHD, International Classification of Headache Disorders.

Study Population

The AMPP Study initially included adults and adolescents (age ≥12 years) with migraine and other headache types, and the CaMEO Study included only adults (age ≥18 years) with migraine. The present analysis includes only participants from both studies 18 years of age or older with migraine. We restricted the age of AMPP participants based on the age range in CaMEO. Both studies used the AMS/AMPP diagnostic module to assess the features of migraine.15, 16 The diagnostic criteria were a modification of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) migraine criteria (ICHD‐2 for the AMPP Study, ICHD‐3b for the CaMEO Study).17 Two criteria were not confirmed: ≥5 lifetime migraine events (criterion A) and duration of attack untreated from 4 to 72 hours (criterion B). In addition, alternative causes of headache were not excluded. CM classification was derived from Silberstein‐Lipton criteria18, 19 and ICHD‐3b criteria for CM. Respondents with CM were defined as those with ≥15 headache days per month averaged over the past 3 months but did not include assessment of ICHD‐3b CM criterion C (ie, ≥8 days per month fulfilled migraine criteria). This criterion was excluded because it is difficult to evaluate in a large, self‐report data‐collection paradigm and requires the use of a diary and physician interview to accurately diagnose. Although all CaMEO participants met diagnostic criteria for migraine, the AMPP Study also enrolled those with other severe headache. For comparability with the CaMEO Study, the AMPP Study data set was limited to migraine cases in this analysis.

Statistical Methods

Baseline data from the AMPP (2005) and CaMEO (2012) studies were used in this analysis.13, 14 Between‐study comparative analyses captured the sociodemographic features of age, sex, income, and race. Comparison data were also generated for headache‐related disability and headache‐day frequency.

Headache‐related disability was assessed using the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire, which categorized missed days of work, household chores, nonwork activity, and days with substantially reduced productivity (ie, >50% reduction in productivity) in the same domains over a 3‐month period.13, 14 Scores were classified by severity as Grade I (little/no disability; score 0–5), Grade II (mild disability; score 6–10), Grade III (moderate disability; score 11–20), or Grade IV (severe disability; score ≥21).20 MIDAS Grades III and IV were netted together and summarized for the purpose of this analysis. Headache‐day frequency was determined in both studies by asking respondents, “On how many days in the past 3 months (previous 90 days) did you have a headache?”13, 14 This number was then divided by 3 to estimate monthly headache‐day frequency.

Because MIDAS and headache‐day frequency are not normally distributed, median scores are presented as the measure of central tendency and interquartile range as the measure of dispersion for all comparisons. For this analysis, respondents from both studies were divided into episodic migraine (EM) and CM groups and further stratified by sex and age (18–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years). Descriptive statistics were generated to compare samples on key target measures. Statistical testing was not conducted because most of the between‐group comparisons involved very large samples. Large sample sizes increase the likelihood that statistical significance will be attributed to differences too small to be of clinical relevance.21 All descriptive statistics were generated with SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Study Design and Participants

Key methodologic differences between the AMPP and CaMEO studies included the sampling unit (households vs individuals), method of data collection (mailed questionnaire vs web survey), and study duration (annually over 5 years vs quarterly over 15 months; Table 1). Of the 120,000 households (representing 257,339 individuals) receiving the AMPP screening survey in 2004, 77,879 households (64.9% response rate) provided data, representing a total of 162,765 individuals aged ≥12 years.22 Analysis of screening survey data identified 28,261 individuals who reported ≥1 severe headache in the past year. In 2005 (the baseline longitudinal year of phase 2 follow‐up), a longer postal survey was sent to 24,000 adults aged ≥18 years, 18,500 of whom returned valid surveys (77.1% response rate). Of these, 794 (6.6%) met criteria for CM and 11,249 (93.4%) met criteria for EM, for a total baseline sample of 12,043 respondents with migraine (Table 1). For the CaMEO Study, 489,537 individuals were invited to participate in the study, and 80,783 (16.5%) responded with demographic and headache‐related screening information. Of the respondents, 58,418 provided complete and valid surveys, 16,789 of whom met diagnostic criteria for migraine (CM, n = 1,476 [8.8%]; EM, n = 15,313 [91.2%]; Table 1).

Demographics

Demographic distributions for age, sex, income, and race were generally similar between studies, indicating a broad US population representation for CM and EM (Table 2). In comparison with the AMPP Study, the CaMEO Study had a higher proportion of young respondents (aged 18–29 years) and more people with higher incomes (≥$50,000) for both CM and EM groups. Sample sizes were adequate to fairly represent all sex and age subgroups, except for the low number of men with CM from the AMPP Study (n = 163). Stratifying by age reduced the subset of men with CM from the AMPP Study to only 17 respondents in the 18‐ to 29‐year age group. Despite the small sample size, results for this segment were consistent between studies for all age subset comparisons.

Table 2.

Comparative Demographics for Baseline AMPP (2005) and Baseline CaMEO (2012) Studies Among Respondents With Episodic and Chronic Migraine

| AMPP | CaMEO | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | EM (n = 11,249) | CM (n = 794) | EM (n = 15,313) | CM (n = 1476) |

| Age (years), n (%) | ||||

| 18–29 | 1,337 (11.9) | 88 (11.1) | 4,267 (27.9) | 364 (24.7) |

| 30–39 | 2,273 (20.2) | 135 (17.0) | 3,463 (22.6) | 330 (22.4) |

| 40–49 | 3,101 (27.6) | 217 (27.3) | 3,126 (20.4) | 350 (23.7) |

| 50–59 | 2,764 (24.6) | 223 (28.1) | 2,585 (16.9) | 282 (19.1) |

| >60 | 1,774 (15.8) | 131 (16.5) | 1,872 (12.2) | 150 (10.2) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Men | 2,254 (20.0) | 163* (20.5) | 4,015 (26.2) | 279 (18.9) |

| Women | 8,995 (80.0) | 631 (79.5) | 11,298 (73.8) | 1,197 (81.1) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 9,827 (88.6) | 720 (91.8) | 12,752 (83.6) | 1,292 (87.8) |

| Non‐white | 1,263 (11.4) | 64 (8.2) | 2,503 (16.4) | 179 (12.2) |

| Income, n (%) | ||||

| <$30,000 | 3,796 (33.7) | 312 (39.3) | 3,301 (21.7) | 441 (30.2) |

| $30,000–$49,999 | 2,424 (21.5) | 168 (21.2) | 2,694 (17.7) | 296 (20.2) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 2,118 (18.8) | 137 (17.3) | 3,457 (22.7) | 317 (21.7) |

| $≥75,000 | 2,911 (25.9) | 177 (22.3) | 5,750 (37.8) | 408 (27.9) |

| Median MIDAS score | ||||

| Men | 3 | 33 | 4 | 32 |

| Women | 6 | 45 | 7 | 38 |

*This N for AMPP Study men with CM is sufficiently large to provide reliable estimates for total sample comparisons but may not be reliable for comparisons stratified by age.

AMPP, American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention; CaMEO, Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes; CM, chronic migraine; EM, episodic migraine; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment.

Headache‐Related Disability

Median MIDAS score was substantially higher in both studies among those with CM (AMPP: men, score = 33; women, score = 45; CaMEO: men, score = 32; women, score = 38) than among those with EM (AMPP: men, score = 3; women, score = 6; CaMEO: men, score = 4; women, score = 7; Table 2). In both studies, women experienced greater disability than men for CM and EM.

Rates of moderate to severe migraine‐related disability (MIDAS Grades III/IV) were similar for the AMPP and CaMEO studies (Fig. 1). The percentage of respondents with Grade III/IV disability was higher in both studies for women compared with men for both CM and EM. In addition, rates of Grade III/IV disability were markedly higher in people with CM than EM, regardless of sex. The proportion of the CM and EM groups with Grade III/IV disability was higher in the CaMEO Study than in the AMPP Study, though differences were small.

Figure 1.

Baseline proportion of respondents with EM and CM with high disability (MIDAS Grade III/IV) in AMPP and CaMEO studies. AMPP, American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention; CaMEO, Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment questionnaire.

Headache‐Day Frequency

Median headache‐day frequencies over the past month for respondents with CM and EM were similar in the AMPP and CaMEO studies (Fig. 2). Median headache‐day frequencies were higher for respondents with CM than for those with EM, regardless of sex. Median headache‐day frequencies for respondents with EM ranged from 1.7 (men in the AMPP Study) to 3.0 (women in the CaMEO Study) headaches in the past month and were similar between studies.

Figure 2.

Baseline median headache‐day frequency for the past month for respondents with CM and EM in the AMPP and CaMEO studies. AMPP, American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention; CaMEO, Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes.

DISCUSSION

The AMPP and CaMEO studies were longitudinal studies that included a broad base of respondents with migraine, representative of the US population. Comparison of baseline demographic data demonstrated similar age, sex, income, and race distributions among EM and CM subsamples between studies, with the exception of slightly higher incomes and a somewhat younger population in the CaMEO Study than in the AMPP Study. The overall distribution of headache‐related disability and headache‐day frequency was also similar between AMPP and CaMEO study respondents. Both studies demonstrated that migraine‐related disability was more severe in women than men and for those with CM than those with EM. Neither study showed sex differences in headache‐day frequency within the CM or EM cohorts. Of note, one sex‐ and age‐stratified CM subgroup from the AMPP Study (men aged 18–29 years) was small (n = 17) but resembled the CaMEO Study; however, because of the small sample size, these results should be interpreted with caution.

The most noteworthy methodological differences between the AMPP and CaMEO studies were methods of data collection, sampling strategy, and survey response rates. This analysis limited the age range of the AMPP Study sample (“severe headache,” age ≥12 years) to that used in the CaMEO Study (“migraine,” age ≥18 years). The differences in survey response rates (77.1% for the AMPP Study vs 16.5% for the CaMEO Study) are noteworthy because survey nonrespondents may differ from respondents in important ways, leading to biased study results.23 To assess potential response bias in CaMEO, a follow‐up survey was sent to a random sample of CaMEO Study nonrespondents. A total of 88,451 individuals were sent study invitations and usable data were obtained from 8,225 (9.3% response rate). As expected for comparisons of large samples, some significant differences were observed in sample demographics between CaMEO respondents and nonrespondents, but the overall pattern of results and the positive case rates for migraine were comparable. However, the participation rate in the nonrespondent survey (9.3% of those invited) was too low to rule out response bias.13

The differences in baseline income and age distributions between AMPP and CaMEO studies may reflect differences in survey design because the CaMEO Study relied on internet access, a methodology more widely used in younger individuals and persons of higher socioeconomic status.24, 25 Persons with CM might have been underrepresented in the CaMEO Study, as CM occurs with higher prevalence in older, lower income, and lower education subgroups.26 Additionally, lack of keyboard and internet literacy27 may limit web‐based study participation for some people, including the elderly or those with learning or physical disabilities. However, among people with migraine, the relative frequency of CM was higher in the CaMEO Study (8.8%) than in the AMPP Study (6.6%), mitigating this cause. In addition, internet access continues to increase, especially among older people, minorities, and individuals with lower incomes or levels of educational achievement.25 Despite potential drawbacks of internet‐based surveys, study designs are evolving, and use of web‐based surveys is expanding to include smartphones linked to the Internet. Smartphone use in the United States is widespread and growing,28 and smartphone applications and text messaging are emerging as methods of conducting research29, 30 and may represent the next generation of epidemiologic surveys.

Both studies had some similar limitations. As is common in epidemiologic studies, all data were self‐reported, and were not verified by healthcare professionals or medical records. The AMPP Study included fewer males and young people, and the CaMEO Study had a low response rate, making the sample populations somewhat different.

These findings also compare favorably with published data from the cross‐sectional International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS), a web‐based survey that collected data from 8,726 people with migraine in 9 countries.31 In IBMS, the proportion of participants with CM was 5.7% and EM was 94.3%; demographic characteristics were also consistent with the AMPP and CaMEO studies, with the majority of respondents being female (CM, 85.6%; EM, 83.4%) and white (CM, 89.4%; EM, 85.9%). In addition, respondents with CM reported greater disability (mean MIDAS score: CM = 72.6, EM = 14.5) and higher rates of moderate/severe disability (MIDAS grade III/IV: CM = 89.6%, EM = 47.4%) than those with EM. Differences in the study populations may account for some of the variability in the results between IBMS and the AMPP and CaMEO studies, since both AMPP and CaMEO were US‐based and only 13.8% of the IBMS population was from the United States.

In sum, the CaMEO Study was conducted to complement and extend previous findings from the AMPP Study. Despite different survey methods and response rates, the overall consistency of findings between studies demonstrates that CaMEO Study respondents are as representative of people with migraine in the United States as AMPP respondents. The implications of these findings are important. The CaMEO Study has generated a wealth of data on persons with migraine that can be used to gain a better understanding of the burden of illness, naturally occurring comorbidity endophenotypes, and barriers to achieving adequate medical care for people with migraine, especially CM. CaMEO data have contributed important information regarding familial burden of migraine from the perspectives of the person with migraine, their partner, and child(ren), providing a more complete picture of migraine's impact on the family than any previous study.32, 33 In addition, the CaMEO Study provides novel information regarding naturally occurring comorbidity endophenotypes among people with migraine, including the contribution of noncephalic pain to new‐onset or persistent CM.34 Although the AMPP Study explored barriers to adequate care for people with EM,35 the CaMEO Study is the first to analyze and report on these barriers for those with CM.2 Ultimately, the increased understanding of migraine garnered by CaMEO Study findings will help better identify individuals in need of care and inform improved disease management decisions for those who need it most.

CONCLUSIONS

The AMPP and CaMEO studies were longitudinal cohort studies of people with migraine that used different methods but yielded similar results for the distribution of demographic characteristics, headache‐related disability, and headache‐day frequency. Comparability of outcomes between the AMPP and CaMEO studies implies that data generated from the CaMEO Study are generalizable to the US migraine population. Future analyses will compare studies for differences in headache consulting, diagnosis, and treatment patterns.

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

Category 1

-

(a) Conception and Design

Richard B. Lipton, Aubrey Manack Adams, Dawn Buse, Michael Reed

-

(b) Acquisition of Data

Tina Fanning, Michael Reed

-

(c) Analysis and Interpretation of Data

Richard B. Lipton, Aubrey Manack Adams, Dawn Buse, Kristina Fanning, Michael Reed

Category 2

-

(a) Drafting the Manuscript

Richard B. Lipton, Dawn Buse

-

(b) Revising It for Intellectual Content

Richard B. Lipton, Aubrey Manack Adams, Dawn Buse, Kristina Fanning, Michael Reed

Category 3

-

(a) Final Approval of the Completed Manuscript

Richard B. Lipton, Aubrey Manack Adams, Dawn Buse, Kristina Fanning, Michael Reed

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial assistance was provided to the authors by Amanda M. Kelly, MPhil, MSHN, of Complete Healthcare Communications, LLC (Chadds Ford, PA), Dana Franznick, PharmD, and Sally K. Laden, MS, and was funded by Allergan plc (Dublin, Ireland). All authors met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors authorship criteria. Neither honoraria nor payments were made for authorship.

The Copyright line for this article was changed on November 29, 2016, after original online publication.

Conflicts of Interest: Richard B. Lipton, MD, has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund. He serves as consultant, serves as an advisory board member, or has received honoraria from Alder, Allergan, American Headache Society, Autonomic Technologies, Boston Scientific, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Cognimed, CoLucid, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Teva, Inc. Aubrey Manack Adams, PhD, is a full‐time employee of Allergan plc, and owns stock in the company. Dawn C. Buse, PhD, has received grant support and honoraria from Allergan, Avanir, Eli Lilly, MAP Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, and Zogenix. She is an employee of Montefiore Medical Center, which has received research support from Allergan, Alder, Avanir, CoLucid, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Labrys, MAP Pharmaceuticals, Merck, NuPathe, Novartis, Ortho‐McNeil, and Zogenix, via grants to the National Headache Foundation and/or Montefiore Medical Center. She is on the editorial board of Current Pain and Headache Reports, the Journal of Headache and Pain, Pain Medicine News, and Pain Pathways magazine. Kristina M. Fanning, PhD, is an employee of Vedanta Research, which has received research funding from Allergan, CoLucid, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck & Co., Inc., NuPathe, Novartis, and Ortho‐McNeil, via grants to the National Headache Foundation. Michael L. Reed, PhD, is Managing Director of Vedanta Research, which has received research funding from Allergan, CoLucid, Dr. Reddy's Laboratories, Endo Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck & Co., Inc., NuPathe, Novartis, and Ortho‐McNeil, via grants to the National Headache Foundation. Vedanta Research has received funding directly from Allergan for work on the CaMEO Study.

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01648530 (CaMEO)

REFERENCES

- 1. Buse DC, Lipton RB, Reed ML, Serrano D, Fanning KM, Manack AN. Barriers to chronic migraine care: Results of the CaMEO (Chronic Migraine Epidemiology & Outcomes) study (Poster P65). Paper presented at the International Headache Congress (IHC) Boston, MA, USA, June 27‐30, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, et al. Assessing barriers to chronic migraine consultation, diagnosis, and treatment: Results from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache. 2016;56:821–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baptista T, Uzcategui E, Arape Y, et al. Migraine life‐time prevalence in mental disorders: Concurrent comparisons with first‐degree relatives and the general population. Invest Clin. 2012;53:38‐51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bigal ME, Kolodner KB, Lafata JE, Leotta C, Lipton RB. Patterns of medical diagnosis and treatment of migraine and probable migraine in a health plan. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:43‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lipton RB, Buse DC, Serrano D, Holland S, Reed ML. Examination of unmet treatment needs among persons with episodic migraine: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2013;53:1300‐1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. MacGregor EA, Brandes J, Eikermann A. Migraine prevalence and treatment patterns: The global Migraine and Zolmitriptan Evaluation survey. Headache. 2003;43:19‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Munakata J, Hazard E, Serrano D, et al. Economic burden of transformed migraine: Results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2009;49:498‐508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Russell MB, Iselius L, Olesen J. Migraine without aura and migraine with aura are inherited disorders. Cephalalgia. 1996;16:305‐309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Silberstein S, Loder E, Diamond S, Reed ML, Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Probable migraine in the United States: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:220‐229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tepper SJ, Dahlof CG, Dowson A, et al. Prevalence and diagnosis of migraine in patients consulting their physician with a complaint of headache: Data from the Landmark Study. Headache. 2004;44:856‐864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lipton RB, Scher AI, Kolodner K, Liberman J, Steiner TJ, Stewart WF. Migraine in the United States: Epidemiology and patterns of health care use. Neurology. 2002;58:885‐894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed ML, Stewart WF. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343‐349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manack Adams A, Serrano D, Buse DC, et al. The impact of chronic migraine: The chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study methods and baseline results. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:563‐578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lipton RB, Serrano D, Pavlovic JM, et al. Improving the classification of migraine subtypes: An empirical approach based on factor mixture models in the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2014;54:830‐849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: Data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:646‐657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Celentano DD, Reed ML. Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States. Relation to age, income, race, and other sociodemographic factors. JAMA. 1992;267:64‐69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Solomon S, Mathew N. Classification of daily and near‐daily headaches in the headache clinic. Proposed revisions to the International Headache Society criteria In: Olesen J, ed. Frontiers in Headache Research. New York: Raven Press, Ltd; 1994:117‐126. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M. Classification of daily and near‐daily headaches: Field trial of revised IHS criteria. Neurology. 1996;47:871‐875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, Tepper SJ, Sheftell FD. Assessment of migraine disability using the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire: A comparison of chronic migraine with episodic migraine. Headache. 2003;43:336‐342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Biau DJ, Kerneis S, Porcher R. Statistics in brief: The importance of sample size in the planning and interpretation of medical research. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2282‐2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buse DC, Loder EW, Gorman JA, et al. Sex differences in the prevalence, symptoms, and associated features of migraine, probable migraine and other severe headache: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache. 2013;53:1278‐1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ekholm O, Gundgaard J, Rasmussen NK, Hansen EH. The effect of health, socio‐economic position, and mode of data collection on non‐response in health interview surveys. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:699‐706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi NG, Dinitto DM. The digital divide among low‐income homebound older adults: Internet use patterns, eHealth literacy, and attitudes toward computer/Internet use. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zickuhr K, Smith A. Digital differences. Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project. Available at: http://pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Digital_differences_041312.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2015.

- 26. Buse DC, Manack Adams A, Serrano D, Turkel C, Lipton RB. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:428‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wyatt JC. When to use web‐based surveys. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7:426‐429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith AK, Page D. U.S. smartphone use in 2015. Pew Research Center. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015/. Accessed April 14, 2015.

- 29. Ainsworth J, Palmier‐Claus JE, Machin M, et al. A comparison of two delivery modalities of a mobile phone‐based assessment for serious mental illness: Native smartphone application vs text‐messaging only implementations. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Buller DB, Borland R, Bettinghaus EP, Shane JH, Zimmerman DE. Randomized trial of a smartphone mobile application compared to text messaging to support smoking cessation. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20:206‐214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: Results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31:301‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buse DC, Scher AI, Dodick DW, et al. Impact of migraine on the family: Perspectives of people with migraine and their spouse/domestic partner in the CaMEO study Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:596–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Buse DC, McGinley J, Fanning KM, Manack Adams A, Lipton RB. Parental Perspective of Migraine Burden on Children: Results from the CaMEO (Chronic Migraine Epidemiology & Outcomes) Study (OR1) Paper presented at the 57th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society (AHS), Washington, DC, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Scher AI, Manack Adams A, Fanning KM, Lipton RB. Pain Comorbidity and the Transition from Episodic to Chronic Migraine: Results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology & Outcomes (CaMEO) Study Paper presented at the 34th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Pain Society (APS), Palm Springs, CA, May 13‐16, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lipton RB, Serrano D, Holland S, Fanning KM, Reed ML, Buse DC. Barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of migraine: Effects of sex, income, and headache features. Headache. 2013;53:81‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]