Abstract

Glioblastoma multiforme is the most common and the most aggressive primary brain tumor. It is characterized by a high degree of hypoxia and also by a remarkable resistance to therapy because of its adaptation capabilities that include autophagy. This degradation process allows the recycling of cellular components, leading to the formation of metabolic precursors and production of adenosine triphosphate. Hypoxia can induce autophagy through the activation of several autophagy-related proteins such as BNIP3, AMPK, REDD1, PML, and the unfolded protein response-related transcription factors ATF4 and CHOP. This review summarizes the most recent data about induction of autophagy under hypoxic condition and the role of autophagy in glioblastoma.

Facts

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most aggressive brain tumor. Despite its high degree of hypoxia, it can survive and resist anticancer treatments. Thus, it is important to study the main GBM adaptive strategies.

Autophagy is a catabolic process that can be induced by hypoxia. In most cancer cases, it leads to cell survival and resistance to anticancer treatments.

The only study about hypoxia-induced autophagy in GBM highlighted its role in cell protection against stress and in the resistance to the antiangiogenic drug bevacizumab.

Owing to its autophagy inhibition properties, chloroquine is currently used for its antitumoral effects in GBM. Indeed, phase III clinical trials have shown an increase in median survival for patients with GBM following surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Open Questions

Which signaling molecules induced by hypoxia are able to trigger autophagy?

Why autophagy has a dual role in cancer: tumor suppression and tumor facilitation?

Given the apparently contradictory effects of autophagy in the response of GBM to treatment (i.e., tumor cell invasiveness and senescence), how autophagy inhibition could be efficient in cancer therapy?

Gliomas originate from an uncontrolled proliferation of glial cells, and consist mainly of primary central nervous system tumors derived from astrocytes or oligodendrocytes. Several authors have successively tried to build a classification of gliomas and the scientific community currently recognizes the World Health Organization (WHO) classification1 that has recently been updated.2 This classification defines the tumor histological type according to the predominant cytological type; the tumor grade, from I to IV depends on the following criteria: increase in cell density, nuclear atypia, mitosis number, vascular hyperplasia and necrosis.3 Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), a grade IV glioma,1 is the most common and most aggressive malignant primary brain tumor4 whose cell type of origin has not yet established. GBM accounts for 60–70% of all glial tumors5 with an incidence of 3–4 cases per 100 000 individuals per year.6 Palliative treatment ensures 6–9 months as median survival, which is extended to 12 months after radiotherapy and 16 months after radio-chemotherapy. Postoperative survival varies from 12 months (50%) to 24 months (20%) and reaches 36 months in 2% of cases. GBM occurs at all ages,7 but is more frequent between 45 and 70 years (70% of cases).8 It constitutes the second leading cause of cancer death in children after leukemia and the third one in adults. Death is usually due to cerebral edema, which causes an increase in intracranial pressure, and a reduced level of vigilance.9 GBM is a highly hypoxic tumor; deep and remote areas of the tumor suffer from a low dioxygen (O2) partial pressure, which can drop down to 1%. Although one would expect that this condition should slow tumor growth, cancer cells eventually develop processes allowing them not only to survive hypoxia, but also to become more aggressive. Among these adaptive responses, autophagy, a catabolic process, leads in most cases to the survival of tumor cells. This survival pathway allows the degradation of different cell components with the production of energy (adenosine triphosphate (ATP)) and metabolic precursors further recycled by the cellular anabolism.

Glioblastoma: Molecular Alterations and Histology

GBM can appear ‘de novo' and quickly evolve without any prior injury; it is then called primary GBM. It can also develop slowly (5–10 years) from a low-grade astrocytoma (grade II or III), and then is called secondary GBM.10 Primary GBM represent over 90% of these tumors. They develop most often in patients aged over 60 years and are characterized by a brief clinical history (about 1 year after diagnosis).10 Secondary GBM are rare (10% of them) and occur in younger patients (average age 45). They are characterized by a longer clinical history and have a better prognosis than primary GBM.10 These two types of GBM are morphologically similar but present different genetic alterations (Table 1). Indeed, primary GBM are essentially characterized by an amplification of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) (36%), a deletion of p16InK4a (p16 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 4a) (31%) and a mutated PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) (25%). In contrast, TP53 (gene encoding p53) mutations are rare (30%).11 On the opposite, secondary GBM are primarily characterized by TP53 mutations (65%), amplification of EGFR is not so frequent (8%) as well as p16INK4a deletion (19%) and PTEN mutation (4%). Monosomy 10 is observed in almost 70% of GBM, whether primary or secondary.10 This monosomy can affect the whole chromosome 10 or only the long arm (loss of heterozygosity 10q) especially in primary GBM.12 Genetic alterations have been recently discovered in IDH genes, encoding isocitrate dehydrogenases 1 (IDH1) and 2 (IDH2).13 IDH1 alterations are present in secondary GBM, but are rarely found in primary GBM; this difference allowed to discriminate between these two tumors types.14, 15 Mutations in IDH1/IDH2 are of real diagnostic value because they also allow the confirmation of a glial tumor, and the distinction between grade II gliomas and pilocytic astrocytomas (grade I).15 Indeed, these mutations have not been detected in any pilocytic astrocytoma, suggesting that these tumors proceed from another mechanism. Over 70% of low-grade gliomas present mutations in IDH1 or IDH2.15 On the contrary, only 5% of primary GBM are affected and 80% of secondary GBM have a mutated IDH1.16 The last WHO classification version incorporates new entities to divide GBM into IDH-wild-type GBM (90% of cases that corresponds to primary GBM) and IDH-mutant GBM (10% of cases that corresponds to secondary GBM).2

Table 1. Percentage of mutations of particular genes in primary and secondary glioblastomas.

| Mutated genes | Primary glioblastoma | Secondary glioblastoma | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | 36% | 8% | 11 |

| p16INK4a | 31% | 19% | 11 |

| PTEN | 25% | 4% | 11 |

| TP53 | 30% | 50% | 11 |

| IDH1 | 5% | 80% | 14, 15, 16 |

The difference in the occurrence of certain mutations between the two types of glioblastomas allowed its molecular classification. Whereas primary glioblastoma is mainly characterized by mutations in EGFR, p16INK4a and PTEN, secondary glioblastoma harbors TP53 and IDH1 mutations.

As for histological characteristics, GBM consists of two distinct tumor areas:

A very high cell density area associated with atypical nuclei and a high mitotic index. The tissue consists only of tumor cells with the presence of newly formed blood vessels (micro-angiogenesis).

An area in which isolated cancer cells invade the parenchyma that remains morphologically and functionally intact and devoid of newly formed blood vessels. 17 The isolated cancer cells reflect the infiltrating nature of GBM; they are characterized by atypical and elongated nuclei. 3

Necrotic areas are found in GBM, which correspond to hypoxic regions surrounded by highly anaplastic cells.3

Hypoxia in GBM

Hypoxia means a low O2 partial pressure (1<pO2<10 mm Hg). It therefore constitutes a limitation on the availability of O2 in many diseases,18 such as brain and cardiovascular ischemia, diabetes and atherosclerosis. Hypoxia is also detected in solid cancers, particularly, in brain tumors such as GBM. In this type of tumors, hypoxic areas can be explained in different ways. First, the uncontrolled proliferation of cancer cells results in the formation of vessel-remote and highly hypoxic areas. Cancer cells react to this low partial pressure of O2 by stimulating neovascularization (from pre-existing blood vessels). Indeed, hypoxic cells secrete VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor). After binding to its receptor on the surface of endothelial cells, VEGF promotes the building of new vessels that help to provide the tumor cells with the required amount of O2 and nutrients, thus ensuring their survival.19 This also leads to their dissemination in the body via the newly formed blood vessels rendered permeable by the VEGF signaling.20 Nevertheless, this tumor vascular network can in turn contribute to the formation of hypoxic areas. In fact, neovascularization gives rise to abnormal, too small, occluded vessels, or capillaries or arteriovenous bifurcations (imperfect vascularization).21 The result is an insufficient supply of O2, which maintains the hypoxic areas, and constitute a selection pressure that favors the rise of highly aggressive cells. Indeed, hypoxia-resistant cells trigger highly conserved signaling pathways to overcome the stress. Not only can these cells adapt to low O2,22 but they also resist anticancer treatments.23

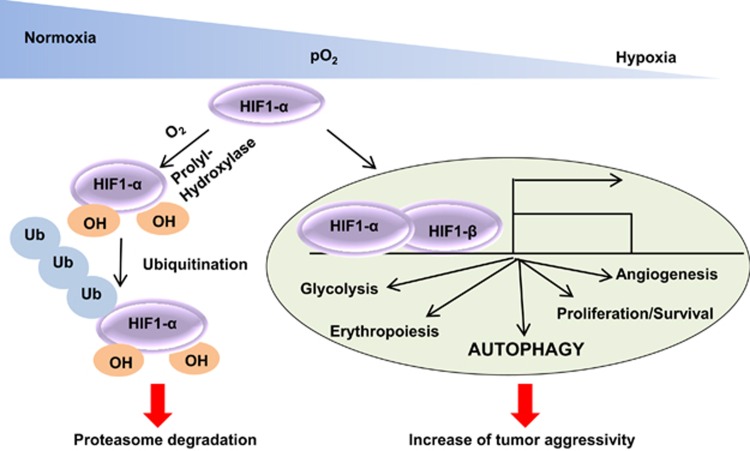

The response and the adaptation of cells to hypoxia are controlled by transcription factors activated by a low partial pressure of O2. The most important transcription factor in this homeostasis is the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 or HIF1 (Figure 1). It consists of a heterodimeric protein composed of one α and one β subunit, which present some sequence and structural domain homologies. These two subunits are differentially expressed.24, 25 HIF1β is constitutively expressed regardless of the availability of O2.26 In contrast, HIF1α has a short half-life (t½~5 min) and is highly regulated by O2.27 In normoxia, HIF1α is subjected to hydroxylation, which allows recruitment of the von Hippel–Lindau protein, polyubiquitination and further degradation by the proteasome.28 However, in hypoxia, HIF1α is stabilized and transferred from the cytosol to the nucleus, where it dimerizes with HIF1β. The HIF1α/HIF1-β assembly becomes transcriptionally active,26 and several coactivators may join this complex to target and refine the transcription of specific genes, such as p300/CBP (CREB (cAMP response element-binding)-binding protein), TIF2 (transcription intermediary factor 2) and SRC-1 (steroid receptor coactivator-1).29 It has also been reported that HIF1-α can be influenced by mutations in mitochondrial enzymes. Among these, IDH1 that is essentially mutated in secondary GBM,16 has been correlated with an increase in HIF1-α protein level and transcriptional activity in GBM cell lines.30 However, this positive link has to be considered in relation with the tumor grade. Indeed, a recent study showed that the expression of HIF1A, as well as its downstream targets, is significantly reduced in grade II (low-grade diffuse) and III (anaplastic) gliomas harboring mutated IDH1/IDH2.31

Figure 1.

Hypoxia stabilizes HIF1 and promotes cell survival. In normoxia, HIF1-α is hydroxylated and then degraded by the proteasome. However in hypoxia, the absence of dioxygen leads to HIF1-α stabilization and complexation with HIF1-β. The HIF1α/HIF1-β complex is transcriptionally active, and following the binding of various coactivators, can target specific genes including those involved in autophagy, survival, proliferation and angiogenesis

At present, >100 genes have been identified as targets of HIF1.32 When expressed, these genes allow the cells to cope with hypoxia,33 they promote angiogenesis (VEGF)34 and cell survival (insulin-like growth factor-2),35 they boost glucose metabolism (glucose transporter-1,3—GLUT1,3)36 and facilitate tumor invasion (matrix metalloproteinases—MMPs).37

Hypoxia may also induce an intracellular recycling mechanism, called autophagy, allowing cancer cells to resist the hypoxic stress.38, 39

Autophagy

Autophagy is a catabolic mechanism highly conserved during evolution. It is found in yeast, plants, worms, flies, mice and humans.40 Autophagy is currently a focus of major scientific interest.41, 42 Besides the proteasome, which mainly degrades short-lived proteins, autophagy eliminates, via lysosomes, altered organelles, long-lived and misfolded proteins. Autophagy occurs in response to nutrient starvation or oxidative stress, and leads to the formation of metabolic precursors (amino acids and fatty acids) and ATP, hence ensuring homeostasis and cell survival.43 However, inadequate repairs or major stress can lead to cell death, named autophagic death.44

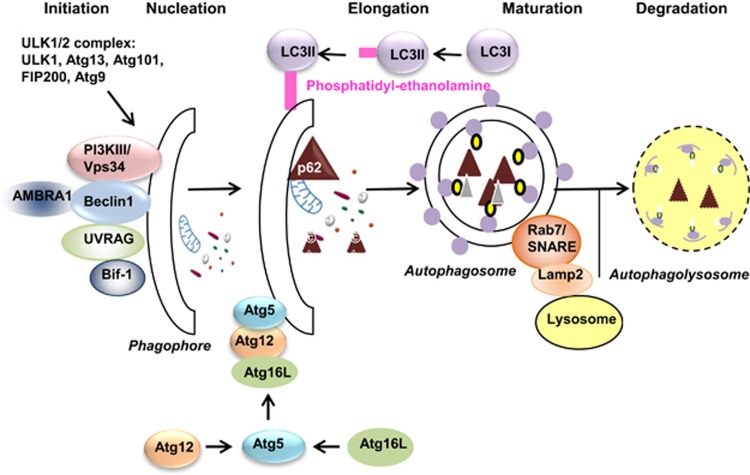

Different types of autophagy are currently described: microautophagy, macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy.45 Macroautophagy is the major recycling process of cytosolic components through the lysosomal pathway and is referred to as ‘autophagy' in the review (Figure 2). It appears from isolated membranes (or phagophore) that rearrange dynamically. This results in a double-membrane structure called autophagosome,46 which may include a portion of cytoplasm. The autophagosomal membrane probably originates from an infolding of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane.47 At the end of the process, the autophagosome fuses with a lysosome to form the autophagolysosome where the sequestered material is degraded by the lysosomal acid hydrolases.48, 49 The process provides metabolic precursors after their release into the cytosol by membrane permeases. The molecular machinery is orchestrated by the autophagy-related genes (ATG) family and autophagy-related proteins (Atg).50 These genes and proteins have been first characterized in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.51 In mammals, many genes (>30) are involved in the genetic control of autophagy. Proteins are classified into three subgroups: the ATG1/ULK1 (Unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1) complex and its regulators, the Beclin1/phosphatidyl-inositol-3 kinase class III complex, and the Atg5-Atg12 and LC3 (light chain 3) conjugation systems.

The ATG1/ULK1 complex is also called the initiator complex of autophagy. It is regulated by the mTOR protein (mammalian target of rapamycin), a kinase forming two complexes, named mTORC (mTOR complex)1 and mTORC2. In nutrient-rich conditions, mTORC1 phosphorylates and inhibits the ATG1/ULK1 complex, thus preventing the initiation of autophagy. 52 In nutritional deficiency conditions or after the addition of rapamycin (mTORC1 inhibitor), mTORC1 dissociates from the complex, decreasing the phosphorylation level of the ATG1/ULK1 complex that becomes active 53 and initiates autophagy. 54 The mTORC2 complex (rapamycin insensitive) can also inhibit autophagy via activation of Akt. The latter activates mTORC1, but also phosphorylates and inhibits FoxO3 (forkhead box O3; reviewed in Hay 55 ) that normally activates the transcription of important autophagy genes, such as BNIP3 (B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2)/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3) and LC3 genes. 56

Formation of the Beclin1/class III phosphatidyl-inositide 3 kinase (PI3K) complex ensures autophagosome nucleation. 47 Beclin1 activation requires its release from Bcl-2 and/or Bcl-xL (Bcl-2 homolog X long protein). 57 Indeed, Beclin1 is inactive when it is bound to these proteins. 58 Other proteins such as UVRAG (UV radiation resistance-associated gene protein), 59 Bif-1 60 and AMBRA1 (activating molecule in Beclin1-regulated autophagy) 61 could interact with Beclin1 to participate in autophagy processing and/or regulation.

The ubiquitin-like Atg5-Atg12 and LC3 conjugation systems are necessary for autophagosome elongation. 62 After its conjugation in the cytosol, the Atg5-Atg12-Atg16L complex transiently binds to the pre-autophagosomal membrane 62 and facilitates the recruitment of the MAP-LC3 (microtubule-associated protein 1 (MAP1) LC3) protein or LC3. 63 The free form of the latter (LC3I) is transformed into the lipidated form LC3II by the covalent binding of a molecule of phosphatidyl ethanolamine. 64, 65

Figure 2.

Autophagy process and molecular actors. Several external stimuli activate the ULK1/2 complex, which initiates isolation membrane near material to be removed. After this initiation step, the nucleation relies on the association of Beclin1 with class III phosphatidyl-inositol 3 kinase (PI3K III) to initiate phagophore formation. Other proteins like UVRAG, Bif-1 and AMBRA1 can also join this complex. The Atg5-Atg12-Atg16L complex and LC3 are two conjugation systems promoting the elongation of the phagophore to form the autophagosome, a vesicle containing the autophagic cargos. Cytosolic-free LC3, named LC3I, is transformed into LC3II, which consists of LC3 covalently bound to a phosphatidyl-ethanolamine molecule. LC3II is then anchored to the pre-autophagosomal membrane. After the binding of certain cytosolic cargos, the p62 protein leads them to the autophagosome, facilitating their degradation by autophagy. Thereafter, the autophagosome fuses with a lysosome to form the autophagolysosome, then the autophagic cargos are degraded by the lysosomal enzymes. Until its degradation, the p62 protein remains associated with the autophagosome

This modification is needed to anchor LC3 to the pre-autophagosomal membrane.64, 66 LC3II remains bound to the autophagosome until its degradation (Figure 2).67 This conversion of LC3I to LC3II is a key marker of autophagy, more particularly when the autophagic flux is inhibited. Indeed, a functional autophagy must lead to the degradation of cargos, which can be evaluated in the presence of lysosomal inhibitors such as chloroquine (CQ) or bafilomycin A1. These inhibitors induce autophagosome and LC3II accumulation in the case of an efficient and functional autophagy. However, evidencing autophagy induction requires that autophagic flux is inhibited, otherwise LC3II would be rapidly degraded and recycled.41

The p53 protein is another important actor of the regulation of autophagy; according to its localization, it can activate or inhibit autophagy. The cytosolic p53 inhibits the formation of autophagic vacuoles68 by interaction with FIP200 (FAK (focal adhesion kinase) family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa), whereas nuclear p53 acts as a transcriptional factor of genes implied in autophagy regulation. For example, PTEN, which is an important negative regulator of the Akt/mTOR pathway.69 The p53-dependent expression of the lysosomal protein DRAM (damage-regulated autophagy modulator) activates macroautophagy.70, 71, 72 Moreover, we have already shown that the efficiency of the signaling is dependent on its genetic profile (wild type or mutated). Indeed, p53 does not always induce autophagy as we evidenced in neuroblastoma cell lines in response to cobalt chloride (CoCl2, a hypoxia-mimicking agent). In the wild-type TP53 neuroblastoma cell line (SHSY5Y), CoCl2 induced an apoptotic signaling involving p53, characterized by a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, and activation of cysteinyl aspartate-specific proteinases (caspases) 9 and 3. In the TP53-mutated neuroblastoma cell line or in the wild-type cells with invalidated TP53 expression (by small hairpin RNA (shRNA)), CoCl2 induced an autophagic signaling. It precedes cell death, occurring later in the absence of caspase activation, but with the release of the mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor, favoring an autophagic cell death.73 Another regulator example is AMPK (adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase), whose role will be detailed below in the section ‘Autophagy and Hypoxia', as this protein is being activated under hypoxia condition.74

Autophagy and GBM

Today, the data on the inhibition and/or the development of a tumor via autophagy seem contradictory. Autophagy presents a dual function in cancer.75, 76 In the early stages of tumorigenesis, it would limit cell proliferation, DNA damage and therefore tumor progression. When the tumor size increases, its blood supply is restricted, and autophagy may promote the survival of tumor cells in the nutrient-deficient and hypoxic tumor regions.77 Furthermore, autophagy, as already evoked, may lead to either cell survival or death.

In particular, it has been shown that BECN1, the gene encoding Beclin1, is deleted in 75%, 50% and 40% in ovarian, breast and prostate cancers, respectively.78 The mutation of a single allele of BECN1 increases the incidence of tumors.79 Deletion of ATG7 has also been reported in several cancers.80, 81 In metabolic stress conditions, autophagy inhibition realized by inactivation of BECN1 or ATG5 increases DNA damage and chromosomal instabilities.82 Thus, autophagy seems to prevent damage to DNA and limit the occurrence of cancers. Finally, the tumor suppressor protein, PTEN, induces an autophagic signaling, whereas it is inhibited by oncogenes.83 However, the autophagy ability to recycle the intracellular contents protects tumor cells from adverse environmental conditions. Thus, this signaling appears as an adaptive mechanism in poorly vascularized solid tumors. It ensures independence in nutrients and energy necessary for the survival of tumor cells in hypoxic regions.84 Indeed, as already described above, hypoxia causes the stabilization of HIF1α. This activates the transcription of several target genes such as VEGF, leading to tumor neovascularization34 and GLUT1-3, ensuring the transport of glucose.36

These contradictory aspects are also observed in the case of GBM. Indeed, autophagy can positively or negatively regulate both GBM invasion and resistance to therapy, the two hallmarks of GBM aggressiveness.85 Concerning invasion and cell motility, whereas Catalano et al.86 reported an impairment of migration and invasion of GBM cells after autophagy induction, Palumbo et al.87 noticed this impairment after autophagy inhibition, especially when EGFR was coinhibited, thus highlighting the importance of growth factor signaling.

When considering therapy resistance, the interplay between classical chemotherapy and autophagy regulation seems to be complex. For example, it has been recently shown that curcurbitacin I, a potent anticancer molecule, induced an autophagy process in GBM cells and in a xenograft model, leading to cell survival and tumor protection.88 However, itraconazole was shown to inhibit the development of GBM through an autophagic signaling induction, whereas the blockage of autophagy significantly reverses the antiproliferative effects of this molecule, suggesting an antitumor role of autophagy in response to itraconazole.89 Temozolomide (TMZ) (Temodal, MERCK, Kirkland, Quebec, Canada) is the most used drug to treat GBM; it induces autophagy in GBM cell lines and provides them with resistance to the treatment. As early as 2004, Kanzawa et al.90 have reported an induction of survival autophagy in GBM cell lines, suppressing the antitumor effect of TMZ. The use of 3-MA (3-methyladenine, class III PI3K inhibitor) or bafilomycin A1 restored TMZ cytotoxicity, suggesting that autophagy inhibition, combined to TMZ in GBM treatment, could enhance the cytotoxicity of this chemotherapeutic agent.91 This twin treatment is currently the most promising strategy to limit tumor development.92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97 Indeed, CQ and its analog hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), which are the only autophagy flux inhibitors98 approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA),99 are in a phase III clinical trial in adjuvant settings, following surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. CQ-treated patients benefit from a clearly better median survival, compared with placebo-treated patients.100 Despite the promising effect of CQ,100 a recent phase I/II clinical trial combining HCQ with TMZ and radiation therapy, in patients with newly diagnosed GBM showed that the maximum tolerated dose of HCQ was unable to consistently inhibit autophagy and that dose-limiting toxicity prevented the possibility of moving to higher doses of HCQ.101 Such a study highlights the toxic side effect of this molecule, used in combination with classical chemotherapeutic agents.102 As a result, we are waiting for further development of novel autophagy inhibitors with less cytotoxicity.

In a contradictory way, another approach to GBM treatment could consist in targeting the autophagy inhibitor mTOR.42, 103 Indeed, dysregulation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway is common in human cancers, inducing uncontrolled cell proliferation, which can be targeted by rapamycin analogs. However, even if in GBM, the presence of autophagy inducers such as RAD001 (mTOR inhibitor) allowed TMZ to induce an autophagic death signaling,104 only few cancers responded to such treatment. It appears that mTOR inhibitors should be associated with other growth factor pathway inhibitors103, 105 or with autophagy inhibitors, considering they can also induce a survival autophagy. Thus, such twin treatment could counteract cell survival pathways, and at the same time, sensitize tumor cells to death. Furthermore, it has been shown that inhibition of mTOR could boost temozolomide-induced senescence, whereas autophagy inhibition triggered apoptosis and decreased senescence.106 Nevertheless, the link between autophagy and senescence needs to be clarified. Indeed, in a particular genetically engineered GBM mouse model in which autophagy was disrupted, gliomagenesis or GBM formation was significantly reduced or completely inhibited.107 In vitro studies showed an intact cellular growth, but a real senescence induction essentially characterized by activation of retinoblastoma 1 (RB1/p105) and an increase in CDKN1B/p27 level.107, 108, 109, 110 Thus, the induction of senescence, consecutively to autophagy dysregulation, needs to be investigated more thoroughly to constitute a hopeful therapy able to reduce GBM aggressiveness.

Finally, targeting autophagic process could also interfere with antiangiogenic therapy, frequently used in cancer. For example, the treatment of GBM cell lines with CQ in combination with 3-MA, ATG7 and BECN1 small interfering RNA (siRNA), blocked the autophagy induced by ZD6474, a small molecule that blocks the VEGF receptor (VEGFR) activity, thereby sensitizing GBM cells to ZD6474-induced apoptosis.111 Indeed, GBM are characterized by their high capacity of angiogenesis112 that is important for tumor growth, making antiangiogenic molecules crucial for GBM treatment.113 However, owing to their tumor devascularization capacity, these molecules cause increased intratumoral hypoxia, which in turn activates autophagy and finally help tumor cells to resist treatment.114 Thus, the antitumor effects of antiangiogenic agents seem to be enhanced when they are combined with autophagy inhibitors.115

Autophagy and Hypoxia

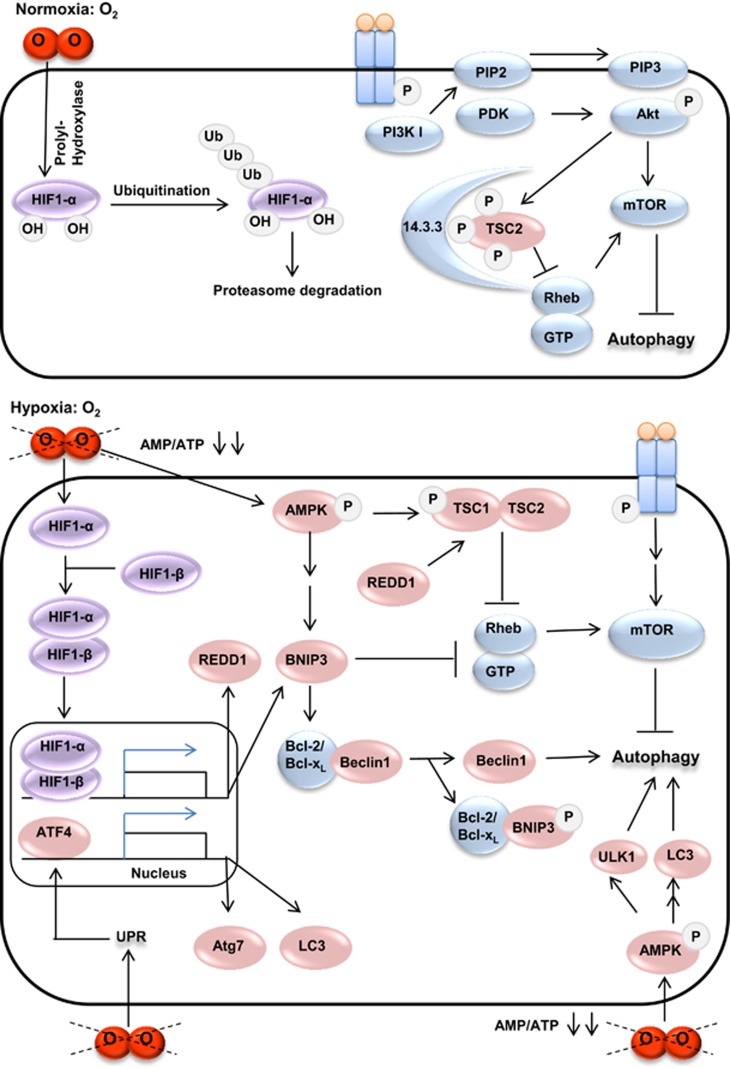

Several studies have reported a link between hypoxia and the induction of autophagy as summarized in Figure 3. In fact, the hypoxia factor HIF1 activates the transcription of the BNIP3 gene,116 encoding the BNIP3 protein, which can induce autophagy. Indeed, BNIP3 displaces Beclin1 from Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL by competing for the same binding site; free Beclin1 then induces autophagy.57 BNIP3 can also activate autophagy by inhibiting the RHEB (Ras homolog enriched in brain) protein, whose activity is required for mTORC1 activation.117

Figure 3.

Different actors involved in the induction of autophagy by hypoxia. In normoxia, HIF1-α is hydroxylated and degraded by proteasome. As the presence of dioxygen is favorable to cellular proliferation, receptor tyrosine kinases that promote proliferation are activated, leading to mTOR activation and autophagy inhibition. However, in hypoxia, HIF1-α is stabilized and it associates with HIF1-β to form HIF1 that activates the transcription of several genes whose encoded proteins activate autophagy. For example, REDD1 activates the mTOR inhibitors, thus removing the autophagy inhibition. BNIP3 can also activate autophagy by decreasing the RHEB/GTP level. Moreover, BNIP3 is a HIF1 target, and it competes with Beclin1 for binding to Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL, triggering the Beclin1 release and the induction of autophagy. BNIP3 can also be induced by AMPK that is activated in response to hypoxia. AMPK can also activate ULK1 and LC3, thus triggering autophagy. In hypoxic conditions, the unfolded protein response (UPR) activates the transcription factor, ATF4, which in turn activates Atg7 and LC3, two proteins involved in the autophagosome elongation

In addition, the energy depletion caused by hypoxia increases the intracellular AMP/ATP ratio, which stimulates the monophosphate-activated protein kinase or AMPK, an energy-sensing switch.118 AMPK indirectly inhibits mTOR by phosphorylation and activation of TSC2 (tuberous sclerosis complex 2) and Raptor, inhibiting the activity of mTORC1 and activating autophagy.119 Indeed, the TSC1–TSC2 complex contains a GTP (guanosine triphosphate)ase-activating protein domain, which stimulates the GTPase activity of RHEB and thereby preventing it to activate mTORC1.120 In addition, AMPK regulates autophagy by phosphorylating ULK1121, 122, 123 and thus inducing mTOR-independent autophagy. AMPK also promotes the accumulation of FoxO3 in the nucleus and the expression of its autophagy-associated target genes (LC3 and BNIP3).124 Moreover, AMPK has been shown to be an important regulator of the HIF1 activity and of the expression of its target genes in prostate cancer cells cultured in the presence of CoCl2.125 Not only is the TSC1–TSC2 complex maintained in its active form (phosphorylation of TSC1) by AMPK, but it is also activated by the REDD1 (regulated in development and DNA damage responses 1) protein, itself activated under hypoxic condition; then autophagy is induced by preventing TSC2 phosphorylation and sequestration by the 14-3-3 protein.126 An interesting study on GBM cell lines showed that hypoxia induced autophagy.115 This signaling was preceded by a stabilization of HIF1α and an increase in phospho-AMPK (active AMPK). The extinction of one of these proteins by siRNA significantly reduced the autophagic process. Hypoxia-induced autophagy was also dependent on BNIP3, whose expression increases under hypoxic condition in GBM cell lines and in xenograft-derived cells. Inhibition of autophagy with CQ induced caspase-dependent apoptotic death, without affecting BNIP3 expression. Moreover, this hypoxia-induced autophagy promoted the tumor resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. Indeed, when GBM xenografts were treated with bevacizumab alone, an increase in BNIP3 expression and hypoxia-associated growth were recorded. Addition of the autophagy inhibitor CQ blocked this process. In vivo, ATG7 extinction in athymic mice by shRNA, also disrupted tumor growth especially when combined with bevacizumab treatment.115 Another hypoxia-activated protein, the tumor suppressor protein PML (promyelocytic leukemia) activates autophagy by binding mTOR, thereby preventing its interaction with RHEB, causing its deactivation and its nuclear accumulation.127, 128

Furthermore, under hypoxic conditions, the protein trafficking (secretion or incorporation in the plasma membrane) is defected because O2 is required for protein maturation.129 Hypoxia initiates the unfolded protein response or UPR, which can in turn induce autophagy through ATF4 (activating transcription factor 4) activation.130 Indeed, ATF4, stabilized in hypoxia, is able to upregulate the LC3B protein, which is essential for the autophagic process. The inhibition of ATF4-activated autophagy significantly increases apoptosis and reduces cell viability in several hypoxic cancer cells.130 Another study carried out on other cancer cells, including U373 MG, a GBM cell line, the hypoxia-induced UPR activated PERK (protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase) in the ER. The latter activates ATF4 and another transcription factor, the C/EBP (CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein) homologous protein or CHOP, which increases the expression of the LC3B and ATG5 genes, thus inducing autophagy. Exposure to CQ sensitized cancer cells to hypoxia and xenografted tumors to irradiation.131

Conclusion

The impact of autophagy on GBM cell fate remains ambiguous. Autophagy could protect cancer cells from drastic environmental conditions such as hypoxia, and from chemo and radiotherapy, but can also inhibit the cell growth and induce senescence, depending on the context. Autophagy induced by chemotherapeutic agents may either promote or inhibit cell survival, depending on the drug used. As for the hypoxia-induced autophagy in this tumor, it has been shown that autophagy was able to protect cancer cells against hypoxia, but also could enhance their resistance to antiangiogenic therapy.115 Furthermore, recent clinical studies have been conducted with CQ, which inhibits autophagy, or with mTOR inhibitors, which activates this process; both kinds of therapies resulted in beneficial effects on GBM evolution.42, 102 These facts highlight the importance of autophagy modulation as a potent anti-GBM strategy that could improve the efficiency of chemotherapy.115 Thus, more studies are needed to elucidate the exact role of autophagy in GBM and to delineate the associated therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr M Guilloton for manuscript editing. SJ was supported by fellowships from the ‘Conseil Régional du Limousin'.

Glossary

- AMP

adenosine monophosphate

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ATF4

activating transcription factor 4

- ATG

autophagy-related genes

- Atg

autophagy-related proteins

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- Bcl-xL

Bcl-2 homolog X long protein

- BECN1

gene encoding Beclin1

- BNIP3

Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3

- Caspase

cysteinyl aspartate-specific proteinase

- CHOP

C/EBP homologous protein

- CoCl2

cobalt chloride

- CQ

chloroquine

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FoxO3

forkhead box O3

- GBM

glioblastoma multiforme

- GLUT1,3

glucose transporter-1,3

- GTP

guanosine triphosphate

- HCQ

hydroxychloroquine

- HIF1

hypoxia-inducible factor 1

- IDH

isocitrate dehydrogenase

- LC3

light chain 3

- 3-MA

3-methyladenine

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- mTORC

mTOR complex

- O2

dioxygen

- p16InK4a

p16 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 4a

- PI3K

phosphatidyl-inositide 3 kinase

- PML

promyelocytic leukemia

- PTEN

phosphatase and tensin

- REDD1

regulated in development and DNA damage responses 1

- RHEB

Ras homolog enriched in brain

- shRNA

small hairpin RNA

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TP53

gene encoding p53

- TSC1/TSC2

tuberous sclerosis complex 1 and 2

- ULK1

Unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- UVRAG

UV radiation resistance-associated gene protein

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Edited by GM Fimia

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 2007; 114: 97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 131: 803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figarella-Branger D, Colin C, Coulibaly B, Quilichini B, Maues De Paula A, Fernandez C et al. [Histological and molecular classification of gliomas]. Rev Neurol 2008; 164: 505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari FB, Fenton T, Bachoo RM, Mukasa A, Stommel JM, Stegh A et al. Malignant astrocytic glioma: genetics, biology, and paths to treatment. Genes Dev 2007; 21: 2683–2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen PY, Kesari S. Malignant gliomas in adults. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 492–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polivka J, Polivka J, Rohan V, Pesta M, Repik T, Pitule P et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase-1 mutations as prognostic biomarker in glioblastoma multiforme patients in West Bohemia. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 735659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm D, Bender S, Jones DTW, Lichter P, Grill J, Becher O et al. Paediatric and adult glioblastoma: multiform (epi)genomic culprits emerge. Nat Rev Cancer 2014; 14: 92–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glioblastome, origine, causes, diagnostic, pronostic, traitements, vaccins. http://gfme.free.fr/maladie/glioblastome.html.

- Krex D, Klink B, Hartmann C, von Deimling A, Pietsch T, Simon M et al. Long-term survival with glioblastoma multiforme. Brain J Neurol 2007; 130: 2596–2606.. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Genetic pathways to primary and secondary glioblastoma. Am J Pathol 2007; 170: 1445–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgaki H, Dessen P, Jourde B, Horstmann S, Nishikawa T, Di Patre PL et al. Genetic pathways to glioblastoma: a population-based study. Cancer Res 2004; 64: 6892–6899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa H, Reis RM, Nakamura M, Colella S, Yonekawa Y, Kleihues P et al. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome 10 is more extensive in primary (de novo than in secondary glioblastomas. Lab Invest 2000; 80: 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanson M, Marie Y, Paris S, Idbaih A, Laffaire J, Ducray F et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 codon 132 mutation is an important prognostic biomarker in gliomas. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 4150–4154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science 2008; 321: 1807–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Bigner DD, Velculescu V, Parsons DW. Mutant metabolic enzymes are at the origin of gliomas. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 9157–9159v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobusawa S, Watanabe T, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H. IDH1 mutations as molecular signature and predictive factor of secondary glioblastomas. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 6002–6007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figarella-Branger D, Bouvier C. [Histological classification of human gliomas: state of art and controversies]. Bull Cancer 2005; 92: 301–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höckel M, Vaupel P. Biological consequences of tumor hypoxia. Semin Oncol 2001; 28: 36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. VEGF and the quest for tumour angiogenesis factors. Nat Rev Cancer 2002; 2: 795–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Box C, Rogers SJ, Mendiola M, Eccles SA. Tumour-microenvironmental interactions: paths to progression and targets for treatment. Semin Cancer Biol 2010; 20: 128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shchors K, Evan G. Tumor angiogenesis: cause or consequence of cancer? Cancer Res 2007; 67: 7059–7061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papandreou I, Powell A, Lim AL, Denko N. Cellular reaction to hypoxia: sensing and responding to an adverse environment. Mutat Res 2005; 569: 87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur B, Khwaja FW, Severson EA, Matheny SL, Brat DJ, Van Meir EG. Hypoxia and the hypoxia-inducible-factor pathway in glioma growth and angiogenesis. Neuro Oncol 2005; 7: 134–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Déry M-AC, Michaud MD, Richard DE. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: regulation by hypoxic and non-hypoxic activators. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2005; 37: 535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagórska A, Dulak J. HIF-1: the knowns and unknowns of hypoxia sensing. Acta Biochim Pol 2004; 51: 563–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallio PJ, Pongratz I, Gradin K, McGuire J, Poellinger L. Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha: posttranscriptional regulation and conformational change by recruitment of the Arnt transcription factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci US 1997; 94: 5667–5672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salceda S, Caro J. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) protein is rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system under normoxic conditions. Its stabilization by hypoxia depends on redox-induced changes. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 22642–22647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Jiang BH, Semenza GL. Effect of altered redox states on expression and DNA-binding activity of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995; 212: 550–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrero P, Okamoto K, Coumailleau P, O'Brien S, Tanaka H, Poellinger L. Redox-regulated recruitment of the transcriptional coactivators CREB-binding protein and SRC-1 to hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol Cell Biol 2000; 20: 402–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, Lin Y, Xu W, Jiang W, Zha Z, Wang P et al. Glioma-derived mutations in IDH1 dominantly inhibit IDH1 catalytic activity and induce HIF-1alpha. Science 2009; 324: 261–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickingereder P, Sahm F, Radbruch A, Wick W, Heiland S, Deimling Av et al. IDH mutation status is associated with a distinct hypoxia/angiogenesis transcriptome signature which is non-invasively predictable with rCBV imaging in human glioma. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 16238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke Q, Costa M. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1). Mol Pharmacol 2006; 70: 1469–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. HIF-1 mediates metabolic responses to intratumoral hypoxia and oncogenic mutations. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 3664–3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy AP, Levy NS, Wegner S, Goldberg MA. Transcriptional regulation of the rat vascular endothelial growth factor gene by hypoxia. J Biol Chem 1995; 270: 13333–13340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldser D, Agani F, Iyer NV, Pak B, Ferreira G, Semenza GL. Reciprocal positive regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and insulin-like growth factor 2. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 3915–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Pore N, Behrooz A, Ismail-Beigi F, Maity A. Regulation of glut1 mRNA by hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Interaction between H-ras and hypoxia. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 9519–9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yosef Y, Lahat N, Shapiro S, Bitterman H, Miller A. Regulation of endothelial matrix metalloproteinase-2 by hypoxia/reoxygenation. Circ Res 2002; 90: 784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieboes HB, Huang JS, Yin WC, McNally LR. Chloroquine-mediated cell death in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma through inhibition of autophagy. JOP 2014; 15: 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S, O'Prey J, Fricker M, Ryan KM. Hypoxia-selective macroautophagy and cell survival signaled by autocrine PDGFR activity. Genes Dev 2009; 23: 1283–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Yuan J. Autophagy in cell death: an innocent convict? J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 2679–2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, Abedin MJ, Abeliovich H, Acevedo Arozena A et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy 2016; 12: 1–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebecca VW, Amaravadi RK. Emerging strategies to effectively target autophagy in cancer. Oncogene 2016; 35: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codogno P, Meijer AJ. Autophagy and signaling: their role in cell survival and cell death. Cell Death Differ 2005; 12(Suppl 2): 1509–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad MB, Chen Y, Henson ES, Cizeau J, McMillan-Ward E, Israels SJ et al. Hypoxia induces autophagic cell death in apoptosis-competent cells through a mechanism involving BNIP3. Autophagy 2008; 4: 195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM, Stefanis L, Fredenburg R, Lansbury PT, Sulzer D. Impaired degradation of mutant alpha-synuclein by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Science 2004; 305: 1292–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz G, Neufeld TP. Autophagy: a forty-year search for a missing membrane source. PLoS Biol 2006; 4: e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axe EL, Walker SA, Manifava M, Chandra P, Roderick HL, Habermann A et al. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 2008; 182: 685–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell 2004; 6: 463–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma K, Suzuki K, Sugawara H. The Autophagy Database: an all-inclusive information resource on autophagy that provides nourishment for research. Nucleic Acids Res 2011; 39: D986–D990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Cregg JM, Dunn WA, Emr SD, Sakai Y, Sandoval IV et al. A unified nomenclature for yeast autophagy-related genes. Dev Cell 2003; 5: 539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. Autophagy: process and function. Genes Dev 2007; 21: 2861–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW et al. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 2010; 90: 1383–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa N, Hara T, Kaizuka T, Kishi C, Takamura A, Miura Y et al. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 2009; 20: 1981–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh Y-Y, Wrasman K, Herman PK. Autophosphorylation within the Atg1 activation loop is required for both kinase activity and the induction of autophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2010; 185: 871–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N. Interplay between FOXO, TOR, and Akt. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1813: 1965–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Ye M, Bucur O, Zhu S, Tanya Santos M, Rabinovitz I et al. Protein phosphatase 2A reactivates FOXO3a through a dynamic interplay with 14-3-3 and AKT. Mol Biol Cell 2010; 21: 1140–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan S, Jain K, Basu A. Regulation of autophagy by kinases. Cancers 2011; 3: 2630–2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, Garuti R, Liang XH, Mizushima N et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell 2005; 122: 927–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Feng P, Ku B, Oh B-H, Jung JU. UVRAG: a new player in autophagy and tumor cell growth. Autophagy 2007; 3: 69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Coppola D, Matsushita N, Cualing HD, Sun M, Sato Y et al. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol 2007; 9: 1142–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fimia GM, Stoykova A, Romagnoli A, Giunta L, Di Bartolomeo S, Nardacci R et al. Ambra1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature 2007; 447: 1121–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Kuma A, Kobayashi Y, Yamamoto A, Matsubae M, Takao T et al. Mouse Apg16L, a novel WD-repeat protein, targets to the autophagic isolation membrane with the Apg12-Apg5 conjugate. J Cell Sci 2003; 116: 1679–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada T, Noda NN, Satomi Y, Ichimura Y, Fujioka Y, Takao T et al. The Atg12-Atg5 conjugate has a novel E3-like activity for protein lipidation in autophagy. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 37298–37302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and autophagy. Methods Mol Biol 2008; 445: 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y-K, Lee J-A. Role of the mammalian ATG8/LC3 family in autophagy: differential and compensatory roles in the spatiotemporal regulation of autophagy. BMB Rep 2016; 49: 424–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisako T, Ichimura Y, Okada H, Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T et al. The reversible modification regulates the membrane-binding state of Apg8/Aut7 essential for autophagy and the cytoplasm to vacuole targeting pathway. J Cell Biol 2000; 151: 263–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J 2000; 19: 5720–5728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasdemir E, Chiara Maiuri M, Morselli E, Criollo A, D'Amelio M, Djavaheri-Mergny M et al. A dual role of p53 in the control of autophagy. Autophagy 2008; 4: 810–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Hu W, de Stanchina E, Teresky AK, Jin S, Lowe S et al. The regulation of AMPK beta1, TSC2, and PTEN expression by p53: stress, cell and tissue specificity, and the role of these gene products in modulating the IGF-1-AKT-mTOR pathways. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 3043–3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criollo A, Dessen P, Kroemer G. DRAM: a phylogenetically ancient regulator of autophagy. Cell Cycle 2009; 8: 2319–2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah LY, O'Prey J, Baudot AD, Hoekstra A, Ryan KM. DRAM-1 encodes multiple isoforms that regulate autophagy. Autophagy 2012; 8: 18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J-H, Her S, Kim M, Jang I-S, Park J. The expression of damage-regulated autophagy modulator 2 (DRAM2) contributes to autophagy induction. Mol Biol Rep 2012; 39: 1087–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naves T, Jawhari S, Jauberteau M-O, Ratinaud M-H, Verdier M. Autophagy takes place in mutated p53 neuroblastoma cells in response to hypoxia mimetic CoCl(2). Biochem Pharmacol 2013; 85: 1153–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Cash TP, Jones RG, Keith B, Thompson CB, Simon MC. Hypoxia-induced energy stress regulates mRNA translation and cell growth. Mol Cell 2006; 21: 521–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White E, DiPaola RS. The double-edged sword of autophagy modulation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15: 5308–5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z, Sanchez-Lopez E, Karin M. Autophagy, inflammation, and immunity: A Troika Governing Cancer and Its Treatment. Cell 2016; 166: 288–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu EY, Ryan KM. Autophagy and cancer–issues we need to digest. J Cell Sci 2012; 125: 2349–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aita VM, Liang XH, Murty VV, Pincus DL, Yu W, Cayanis E et al. Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics 1999; 59: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ, Heintz N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 15077–15082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaravadi R, Debnath J. Mouse models address key concerns regarding autophagy inhibition in cancer therapy. Cancer Discov 2014; 12: 873–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura A, Komatsu M, Hara T, Sakamoto A, Kishi C, Waguri S et al. Autophagy-deficient mice develop multiple liver tumors. Genes Dev 2011; 25: 795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchihara K, Fujii S, Esumi H. Autophagy and cancer: dynamism of the metabolism of tumor cells and tissues. Cancer Lett 2009; 278: 130–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri MC, Tasdemir E, Criollo A, Morselli E, Vicencio JM, Carnuccio R et al. Control of autophagy by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Cell Death Differ 2009; 16: 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S, White E. Role of autophagy in cancer: management of metabolic stress. Autophagy 2007; 3: 28–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galavotti S, Bartesaghi S, Faccenda D, Shaked-Rabi M, Sanzone S, McEvoy A et al. The autophagy-associated factors DRAM1 and p62 regulate cell migration and invasion in glioblastoma stem cells. Oncogene 2013; 32: 699–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano M, D'Alessandro G, Lepore F, Corazzari M, Caldarola S, Valacca C et al. Autophagy induction impairs migration and invasion by reversing EMT in glioblastoma cells. Mol Oncol 2015; 9: 1612–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo S, Tini P, Toscano M, Allavena G, Angeletti F, Manai F et al. Combined EGFR and autophagy modulation impairs cell migration and enhances radiosensitivity in human glioblastoma cells. J Cell Physiol 2014; 229: 1863–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Yan S-F, Xue H, Zhang P, Sun J-T, Li G. Cucurbitacin I induces protective autophagy in glioblastoma in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 10607–10619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, Li J, Zhang T, Zou L, Chen Y, Wang K et al. Itraconazole suppresses the growth of glioblastoma through induction of autophagy: involvement of abnormal cholesterol trafficking. Autophagy 2014; 10: 1241–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzawa T, Germano IM, Komata T, Ito H, Kondo Y, Kondo S. Role of autophagy in temozolomide-induced cytotoxicity for malignant glioma cells. Cell Death Differ 2004; 11: 448–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Wang Q, Li B, Xie B, Wang W. Temozolomide induces autophagy via ATM-AMPK-ULK1 pathways in glioma. Mol Med Rep 2014; 10: 411–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manic G, Obrist F, Kroemer G, Vitale I, Galluzzi L. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine for cancer therapy. Mol Cell Oncol 2014; 1: e29911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DS, Blanco E, Kim Y-S, Rodriguez AA, Zhao H, Huang TH-M et al. Chloroquine eliminates cancer stem cells through deregulation of Jak2 and DNMT1. Stem Cells 2014; 32: 2309–2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balic A, Sørensen MD, Trabulo SM, Sainz B, Cioffi M, Vieira CR et al. Chloroquine targets pancreatic cancer stem cells via inhibition of CXCR4 and hedgehog signaling. Mol Cancer Ther 2014; 13: 1758–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Sun R, Yang X, Liu D, Lei D, Jin T et al. Chloroquine-enhanced efficacy of cisplatin in the treatment of hypopharyngeal carcinoma in xenograft mice. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0126147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangwala R, Leone R, Chang YC, Fecher LA, Schuchter LM, Kramer A et al. Phase I trial of hydroxychloroquine with dose-intense temozolomide in patients with advanced solid tumors and melanoma. Autophagy 2014; 10: 1369–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sui X, Kong N, Wang X, Fang Y, Hu X, Xu Y et al. JNK confers 5-fluorouracil resistance in p53-deficient and mutant p53-expressing colon cancer cells by inducing survival autophagy. Sci Rep 2014; 4: 4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Gonzalez-Noriega A, Grubb JH, Talkad V, Sly WS. Chloroquine inhibits lysosomal enzyme pinocytosis and enhances lysosomal enzyme secretion by impairing receptor recycling. J Cell Biol 1980; 85: 839–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y-L, Jahangiri A, Delay M, Aghi MK. Tumor cell autophagy as an adaptive response mediating resistance to treatments such as antiangiogenic therapy. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 4294–4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo J, Briceño E, López-González MA. Adding chloroquine to conventional treatment for glioblastoma multiforme: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144: 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MR, Ye X, Supko JG, Desideri S, Grossman SA, Brem S et al. A phase I/II trial of hydroxychloroquine in conjunction with radiation therapy and concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Autophagy 2014; 10: 1359–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojton J, Meisen WH, Kaur B. How to train glioma cells to die: molecular challenges in cell death. J Neurooncol 2016; 126: 377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour M, Dormond-Meuwly A, Demartines N, Dormond O. Targeting the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in cancer therapy: lessons from past and future perspectives. Cancers 2011; 3: 2478–2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josset E, Burckel H, Noël G, Bischoff P. The mTOR inhibitor RAD001 potentiates autophagic cell death induced by temozolomide in a glioblastoma cell line. Anticancer Res 2013; 33: 1845–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nghiemphu PL, Lai A, Green RM, Reardon DA, Cloughesy T. A dose escalation trial for the combination of erlotinib and sirolimus for recurrent malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol 2012; 110: 245–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi-Chiela EC, Bueno e Silva MM, Thomé MP, Lenz G. Single-cell analysis challenges the connection between autophagy and senescence induced by DNA damage. Autophagy 2015; 11: 1099–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammoh N, Fraser J, Puente C, Syred HM, Kang H, Ozawa T et al. Suppression of autophagy impedes glioblastoma development and induces senescence. Autophagy 2016; 12: 1431–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta JC, Banito A, Wuestefeld T, Georgilis A, Janich P, Morton JP et al. A complex secretory program orchestrated by the inflammasome controls paracrine senescence. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15: 978–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander K, Hinds PW. Requirement for p27(KIP1) in retinoblastoma protein-mediated senescence. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21: 3616–3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Espín D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15: 482–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Zheng H, Ruan J, Fang W, Li A, Tian G et al. Autophagy inhibition induces enhanced proapoptotic effects of ZD6474 in glioblastoma. Br J Cancer 2013; 109: 164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagner J-P, Law M, Fischer I, Newcomb EW, Zagzag D. Angiogenesis in gliomas: imaging and experimental therapeutics. Brain Pathol 2005; 15: 342–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain MC. Bevacizumab for the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2011; 5: 117–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y-L, Jahangiri A, De Lay M, Aghi MK. Hypoxia-induced tumor cell autophagy mediates resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Autophagy 2012; 8: 979–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y-L, DeLay M, Jahangiri A, Molinaro AM, Rose SD, Carbonell WS et al. Hypoxia-induced autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and adaptation to antiangiogenic treatment in glioblastoma. Cancer Res 2012; 72: 1773–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azad MB, Gibson SB. Role of BNIP3 in proliferation and hypoxia-induced autophagy: implications for personalized cancer therapies. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1210: 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang Y, Kim E, Beemiller P, Wang C-Y, Swanson J et al. Bnip3 mediates the hypoxia-induced inhibition on mammalian target of rapamycin by interacting with Rheb. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 35803–35813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG. Sensing of energy and nutrients by AMP-activated protein kinase. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 93: 891S–896S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell 2008; 30: 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan K-L. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 2003; 115: 577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science 2011; 331: 456–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan K-L. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13: 132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Park S, Takahashi Y, Wang H-G. The association of AMPK with ULK1 regulates autophagy. PLoS One 2010; 5: e15394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiacchiera F, Simone C. Inhibition of p38alpha unveils an AMPK-FoxO3A axis linking autophagy to cancer-specific metabolism. Autophagy 2009; 5: 1030–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Hwang J-T, Lee H-J, Jung S-N, Kang I, Chi S-G et al. AMP-activated protein kinase activity is critical for hypoxia-inducible factor-1 transcriptional activity and its target gene expression under hypoxic conditions in DU145 cells. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 39653–39661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, Manning BD, Reiling JH, Hafen E et al. Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev 2004; 18: 2893–2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi R, Guernah I, Jin D, Grisendi S, Alimonti A, Teruya-Feldstein J et al. PML inhibits HIF-1alpha translation and neoangiogenesis through repression of mTOR. Nature 2006; 442: 779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi R, Papa A, Egia A, Coltella N, Teruya-Feldstein J, Signoretti S et al. Pml represses tumour progression through inhibition of mTOR. EMBO Mol Med 2011; 3: 249–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzymski T, Milani M, Singleton DC, Harris AL. Role of ATF4 in regulation of autophagy and resistance to drugs and hypoxia. Cell Cycle 2009; 8: 3838–3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rzymski T, Milani M, Pike L, Buffa F, Mellor HR, Winchester L et al. Regulation of autophagy by ATF4 in response to severe hypoxia. Oncogene 2010; 29: 4424–4435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouschop KMA, van den Beucken T, Dubois L, Niessen H, Bussink J, Savelkouls K et al. The unfolded protein response protects human tumor cells during hypoxia through regulation of the autophagy genes MAP1LC3B and ATG5. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 127–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]