Abstract

Small RNAs of 20–30 nucleotides guide regulatory processes at the DNA or RNA level in a wide range of eukaryotic organisms. Many, although not all, small RNAs are processed from double-stranded RNAs or single-stranded RNAs with local hairpin structures by RNase III enzymes and are loaded into argonaute-protein-containing effector complexes. Many eukaryotic organisms have evolved multiple members of RNase III and the argonaute family of proteins to accommodate different classes of small RNAs with specialized molecular functions. Some small RNAs cause transcriptional gene silencing by guiding heterochromatin formation at homologous loci, whereas others lead to posttranscriptional gene silencing through mRNA degradation or translational inhibition. Small RNAs are not only made from and target foreign nucleic acids such as viruses and transgenes, but are also derived from endogenous loci and regulate a multitude of developmental and physiological processes. Here I review the biogenesis and function of three major classes of endogenous small RNAs in plants: microRNAs, transacting siRNAs, and heterochromatic siRNAs, with an emphasis on the roles of these small RNAs in developmental regulation.

Keywords: Dicer-like, argonaute, miRNA, siRNA, chromatin

INTRODUCTION

The diversity and widespread existence of small RNAs and the fundamental importance of small-RNA-mediated regulation were not appreciated until recent years. However, phenomena that can be at least partially attributed to small-RNA-mediated silencing were observed decades ago. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, numerous studies demonstrated that expression of pieces of a viral genome in plants protected these plants from infection by the virus and even related viruses (reviewed in Prins et al. 2008). It was also found that transgenes led to the silencing of endogenous genes in a homology-dependent manner (Napoli et al. 1990, van der Krol et al. 1990). The transgene-mediated gene silencing or viral protection exhibited sequence specificity, but the underlying mechanism was unknown. A breakthrough study by Fire and colleagues in Caenorhabditis elegans revealed that long double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) confer effective sequence-specific silencing of endogenous genes in a process named RNA interference or RNA silencing (Fire et al. 1998). Another breakthrough study, by Hamilton & Baulcombe, uncovered small RNAs derived from plant transgenes undergoing RNA silencing (Hamilton & Baulcombe 1999). These and biochemical studies performed in animals demonstrated that small RNAs, which are produced from long dsRNAs, guide the cleavage of complementary target mRNAs in RNA silencing (reviewed in Hannon 2002). The previously observed transgene-mediated silencing phenomena against viruses and endogenous genes are now understood to be manifestations of RNA silencing. Transcripts from the transgenes are converted into dsRNAs, which are processed into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (see sidebar Three Major Types of Small RNAs) that guide the cleavage of homologous RNAs to lead to gene silencing.

Small RNAs are not derived only from transgenes. As early as 1993, long before the mechanism of RNA silencing was uncovered, elegant molecular genetic studies in C. elegans identified the first endogenous small RNA, now known as microRNA (miRNA) (Lee et al. 1993) (see sidebar Three Major Types of Small RNAs). Mutations in this miRNA gene, lin-4, result in failure to undergo proper developmental transitions. The lin-4 miRNA base pairs with the 3′ untranslated region of its target gene lin-14 to result in translational inhibition of lin-14 mRNA. The identification of a second miRNA, also through forward genetics in C. elegans, let-7, which has homologs in all bilaterally symmetric animals, prompted the search for other such small RNAs (Pasquinelli et al. 2000, Reinhart et al. 2000). In 2001, tens of miRNAs were found in several animal species through direct cloning (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001, Lau et al. 2001, Lee & Ambros 2001). Since then, direct cloning efforts as well as bioinformatics prediction have revealed a large complement of miRNAs in diverse animal and plant species.

miRNAs only constitute one of several types of endogenous small RNAs. Endogenous siRNAs were first found in plants and C. elegans through small-scale cloning efforts (Ambros et al. 2003, Llave et al. 2002a). When high-throughput sequencing technology was first applied to sequence small RNA libraries, it became evident that miRNAs represent only a tiny fraction of the total complement of small RNAs in plants (Lu et al. 2005). For example, in Arabidopsis, which possesses fewer than 200 miRNAs, tens of thousands of distinct small RNAs are found in inflorescence tissue. The majority of endogenous small RNAs are siRNAs. Endogenous siRNAs (sometimes called endo-siRNAs) have also been found recently in flies and mammals through high-throughput sequencing (reviewed in Ghildiyal & Zamore 2009). In addition, animals have a third type of small RNA, known as piwi-interacting RNA or piRNA (reviewed in Ghildiyal & Zamore 2009) (see sidebar Three Major Types of Small RNAs).

The past 10 years have witnessed rapid progress in revealing small RNA diversity, uncovering their mechanisms of action, and understanding their biological functions. Here I review our current knowledge of small RNAs in plants, with an emphasis on the biogenesis and developmental roles of various types of small RNAs.

ARGONAUTE PROTEINS: EFFECTORS OF SMALL-RNA-MEDIATED REGULATION

Small RNAs are invariably bound by an argonaute protein, a member of an evolutionarily conserved family of proteins found in bacteria, archaea, fungi, plants, and animals. The RNA protein complex, which consists of a single-stranded small RNA and an argonaute protein, is commonly referred to as a RISC. Argonaute proteins contain several functional domains as revealed by structural studies: the PAZ, MID, and PIWI domains (reviewed in Hutvagner & Simard 2008). The PAZ domain binds the 2-nucleotide (nt) single-stranded overhang in a small RNA duplex and presumably plays a role in the loading of the duplex onto the protein. The duplex is then unwound such that only one strand is retained in the RISC. The MID-PIWI interface presents a binding pocket that anchors the 5′ phosphate of the single-stranded small RNA. The PIWI domain adopts an RNase H fold and possesses RNA endonucleolytic activity. This activity, sometimes referred to as the slicer (or slicing) activity, is responsible for small-RNA-guided cleavage of target mRNAs in RNA silencing.

Argonaute proteins can be divided into two phylogenetic groups based on their sequence relatedness: the argonaute subfamily and the piwi subfamily (reviewed in Hutvagner & Simard 2008). The argonaute subfamily proteins associate with miRNAs and siRNAs, whereas the piwi subfamily proteins bind piRNAs. Although plants lack the piwi subfamily of proteins as well as piRNAs, the expansion of the argonaute subfamily reflects extensive diversity in the functions of siRNAs and miRNAs. Among the 10 Arabidopsis argonaute (AGO) proteins, AGO1, AGO4, AGO6, AGO7, and AGO10 have been functionally associated with various classes of small RNAs (reviewed in Vaucheret 2008). AGO1 binds most miRNAs, trans-acting siRNAs (ta-siRNAs), and transgene siRNAs; possesses slicing activity; and mediates the functions of these small RNAs in vivo (Baumberger & Baulcombe 2005, Fagard et al. 2000, Qi et al. 2005, Vaucheret et al. 2004). AGO1 and AGO10 are most related to each other and are both implicated in miRNA-mediated translational repression of target mRNAs (Brodersen et al. 2008). AGO4 and AGO6, two closely related AGO proteins, act via endogenous siRNAs to silence transposons and repeated sequences (Zheng et al. 2007, Zilberman et al. 2003). AGO7 is unique in that it preferentially associates with a single miRNA, miR390, to trigger the production of ta-siRNAs (Montgomery et al. 2008a). The small RNAs that are associated with 5 of the 10 AGOs have been immunopurified and subjected to high-throughput sequencing (Mi et al. 2008, Montgomery et al. 2008a, Qi et al. 2006, Takeda et al. 2008). Distinct preferences for the 5′ nucleotide of a small RNA by AGO1, AGO2, AGO4, and AGO5 constitute one mechanism of sorting small RNAs into different complexes.

PROTEINS INVOLVED IN SMALL-RNA BIOGENESIS

DNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases

RNA polymerase II (Pol II) is responsible for transcribing MIR genes to produce miRNA precursors in plants and animals (Lee et al. 2004, Xie et al. 2005a). In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Pol II is essential for siRNA-directed pericentromeric heterochromatin formation (Djupedal et al. 2005, Kato et al. 2005). Pol II transcribes pericentromeric repeats to produce transcripts that give rise to siRNAs. These transcripts also recruit siRNAs, which in turn recruit histone methyltransferases to modify the chromatin (reviewed in Verdel & Moazed 2005). Plants, however, have evolved two other polymerases, Pol IV and Pol V, which specialize in siRNA biogenesis or function (Herr et al. 2005, Kanno et al. 2005, Onodera et al. 2005, Pontier et al. 2005). The subunit compositions of Pol IV and Pol V indicate that the two atypical polymerases have evolved from Pol II (Huang et al. 2009, Lahmy et al. 2009, Ream et al. 2008). Both share a number of subunits with Pol II, and the subunits that differ from Pol II have related counterparts in Pol II. Pol IV and Pol V differ from each other by the largest subunit and several other subunits. They share the same second-largest subunit and all subunits in common with Pol II.

Pol IV is responsible for the production of over 90% of all endogenous siRNAs (Mosher et al. 2008, Zhang et al. 2007). Pol IV–dependent siRNAs tend to originate from pericentromeric regions, transposable elements, and repeats (Herr et al. 2005, Kanno et al. 2005, Mosher et al. 2008, Onodera et al. 2005, Zhang et al. 2007). It is thought that Pol IV transcribes heterochromatic DNA to produce siRNA precursors, although DNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity has not been detected so far. A putative chromatin remodeling protein, CLASSY1, is also required for siRNA biogenesis and may act together with Pol IV (Smith et al. 2007).

Pol V is required for siRNA-mediated DNA methylation and histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methylation at heterochromatic loci (Kanno et al. 2005, Pontier et al. 2005). Although Pol V has not been demonstrated to have DNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity in vitro, Pol V–dependent transcripts originating outside of, and encompassing, loci silenced by siRNAs have been detected (Wierzbicki et al. 2008). It is thought that these transcripts recruit siRNAs to the genomic loci for chromatin modification (Wierzbicki et al. 2009). In addition, Pol V can physically interact with AGO4 through its GW-WG motifs (El-Shami et al. 2007, Li et al. 2006). Pol V may serve the dual function of generating transcripts targeted by AGO4-bound siRNAs and recruiting AGO4 (and associated siRNAs) through physical interaction.

RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases (RdRPs)

RdRPs use single-stranded RNAs as templates and generate dsRNAs, which are then processed into siRNAs by Dicer. Among the six Arabidopsis RDR genes, RDR1, RDR2, and RDR6 have all been implicated in the biogenesis of siRNAs from plant viruses (Diaz-Pendon et al. 2007, Donaire et al. 2008). RDR6 also acts in RNA silencing triggered by sense but not hairpin transgenes and in the biogenesis of ta-siRNAs (Dalmay et al. 2000, Mourrain et al. 2000, Peragine et al. 2004, Vazquez et al. 2004b). RDR2 is a crucial player in the biogenesis of heterochromatic siRNAs; over 90% of these siRNAs require RDR2 for their biogenesis (Kasschau et al. 2007, Lu et al. 2006, Xie et al. 2004). MOP1, the maize ortholog of RDR2, is required for paramutation, a phenomenon whereby one allele leads to heritable silencing of another allele at the same locus, and for the production of 24-nt endogenous siRNAs (Alleman et al. 2006, Nobuta et al. 2008).

Because the production of dsRNAs is one of the first steps in siRNA biogenesis, the substrate specificity or recruitment of RdRPs determines which transcripts undergo siRNA biogenesis in vivo. Genetic evidence indicates that aberrant RNAs, such as ones that lack a 5′ cap or 3′ polyA tail, tend to be channeled into RNA silencing pathways (Gazzani et al. 2004, Gregory et al. 2008, Herr et al. 2006). In vitro, however, RDR6 does not exhibit any preference for noncapped or nontailed RNAs (Curaba & Chen 2008). SGS3, an RNA-binding protein that is required for transgene silencing and ta-siRNA production and that is proposed to bind to the substrates of RDR6 in vivo, does not affect the activity of RDR6 in vitro (Fukunaga & Doudna 2009, Mourrain et al. 2000, Peragine et al. 2004, Vazquez et al. 2004b, Yoshikawa et al. 2005). Future challenges in small-RNA biology include the identification of in vivo substrates of RdRPs and understanding how RdRPs recognize their substrates.

RNase III Endonucleases

Arabidopsis has four Dicer-like (DCL) proteins with distinct, hierarchical, and overlapping functions in small-RNA biogenesis. The two processing steps in miRNA biogenesis are performed by two RNase III endonucleases, Drosha and Dicer, in animals and a single DCL protein in plants. Most miRNAs are produced by DCL1, although a few evolutionarily young miRNAs are generated by DCL4 (Park et al. 2002, Rajagopalan et al. 2006, Reinhart et al. 2002), which appears to prefer long dsRNA substrates such as hairpin RNAs, viral RNAs, and dsRNAs generated by RDR6 at transgene or ta-siRNA loci (Deleris et al. 2006, Fusaro et al. 2006, Gasciolli et al. 2005, Xie et al. 2005b, Yoshikawa et al. 2005). DCL3 produces 24-nt siRNAs at heterochromatic loci (Xie et al. 2004). Hierarchical DCL activities such that one DCL has priority at one substrate and surrogate DCLs access the substrate in the absence of the primary DCL have been documented in many instances, such as the production of viral, endogenous, and transgene siRNAs (Deleris et al. 2006, Fusaro et al. 2006, Kasschau et al. 2007).

RNA Methyltransferases

miRNAs and siRNAs from plants bear a 2′-O-methyl group, which protects the small RNAs from degradation and from a uridylation activity that adds a short U tail to the 3′ ends (Li et al. 2005, Yu et al. 2005). The methyl group is introduced by the RNA methyltransferase HEN1, which acts on small RNA duplexes with 2-nt 3′ overhangs, that is, products of Dicer (Yu et al. 2005). In animals, miRNAs are not methylated, but siRNAs and piRNAs are 2′-O-methylated by homologs of Arabidopsis HEN1 (reviewed in Ghildiyal & Zamore 2009). The animal homologs of HEN1 lack a dsRNA binding domain and act on single-stranded small RNAs.

Exonucleases

Two 3′-5′ exoribonucleases have been shown to degrade small RNAs. Eri-1 from C. elegans acts on small RNA duplexes to remove the 2-nt 3′ overhangs in vitro and limits the efficiency of RNAi in vivo (Kennedy et al. 2004). SDN1 and its paralogs in Arabidopsis act on single-stranded small RNAs in vitro and restrict the abundance of small RNAs in vivo (Ramachandran & Chen 2008a).

MECHANISMS OF miRNA BIOGENESIS AND FUNCTION

Metabolism

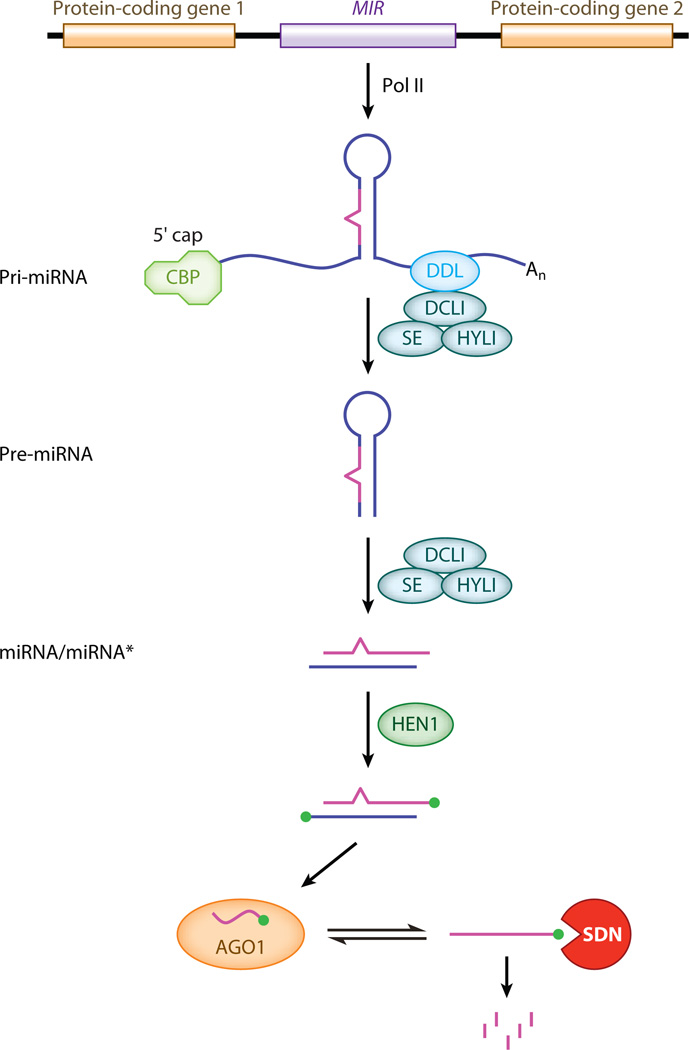

miRNA biogenesis is a multi-step process including transcription, processing, modification, and RISC loading (Figure 1). A MIR gene is transcribed by Pol II into a capped and polyadenylated pri-miRNA, which is processed into the stem-loop precursor, pre-miRNA, by a DCL protein, usually DCL1 in Arabidopsis (Park et al. 2002, Reinhart et al. 2002, Xie et al. 2005a). The pre-miRNA is further processed by DCL1 into a duplex of miRNA and miRNA*. DCL1 acts with two partner proteins: HYL1 (a double-stranded RNA binding protein) and SE (a zinc finger protein) (Han et al. 2004, Lobbes et al. 2006, Vazquez et al. 2004a, Yang et al. 2006). These three proteins colocalize in nuclear Dicing bodies in vivo (Fang & Spector 2007, Fujioka et al. 2007, Song et al. 2007). SE also localizes in numerous nuclear speckles and acts in the splicing of pre-mRNAs (Fang & Spector 2007, Fujioka et al. 2007, Laubinger et al. 2008). The nuclear heterodimeric cap-binding complex (CBP) promotes the accumulation of some but not all miRNAs (Gregory et al. 2008, Laubinger et al. 2008). A nuclear RNA-binding protein, DDL, which interacts with DCL1, promotes, but is not essential for, miRNA accumulation (Yu et al. 2008). The miRNA-miRNA* duplex is methylated on the 2′ OH of the 3′ terminal nucleotides by HEN1 (Yu et al. 2005). One strand of the duplex is loaded into an AGO1-containing miRISC (Baumberger & Baulcombe 2005, Qi et al. 2005). The miRNA is exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm through export factors including HASTY (Park et al. 2005). The SDN1 family of exonucleases degrades single-stranded miRNAs to limit their steady-state levels.

Figure 1.

miRNA biogenesis and degradation. A plant microRNA gene (MIR) is located between two protein-coding genes. The MIR gene is transcribed into a pri-miRNA, which is capped and polyadenylated. The pri-miRNA is processed into the pre-miRNA, which is further processed into the miRNA/miRNA* duplex. The duplex is methylated by HEN1 and the miRNA is loaded into an AGO1 complex. The heterodimeric cap-binding complex (CBP) and the RNA binding protein DDL promote miRNA biogenesis but are not essential. (See text for a more detailed description of the major steps in miRNA metabolism.) DDL, DAWDLE; DCL1, DICER-LIKE1; SE, SERRATE; HYL1, HYPONASTIC LEAVES1; AGO1, ARGONAUTE1; SDN, SMALL RNA DEGRADING NUCLEASE.

Evolution

As miRNAs are identified by high-throughput sequencing from many plant species, it has become evident that miRNA genes are evolving rapidly. Each plant species has miRNAs that are not present in other, even closely related species. Among the ~100 miRNA families from Arabidopsis, only 21 are present in the monocot rice, which suggests that many miRNAs evolved after the dicot-monocot split (reviewed in Axtell & Bowman 2008). In fact, at least 29 miRNAs from Arabidopsis thaliana were not detectable in the preliminary assembly of the Arabidopsis lyrata genome (A. thaliana and A. lyrata diverged about five million years ago) (de Felippes et al. 2008). One model of miRNA origin posits that MIR genes arise from the inverted duplication of target genes (Allen et al. 2004). This hypothesis is based on the fact that one or both arms of the precursors to some of the young miRNAs show extensive similarity to their targets located elsewhere in the genome. This model predicts a stepwise evolutionary process whereby transcription through the initial inverted repeat results in a hairpin RNA that generates many small RNAs through DCL4 processing, and subsequent mutations in the inverted repeat accumulate bulges in the stem region to render DCL1 specificity in processing and production of a single predominant small-RNA species. Based on the fact that the precursor arms of many young miRNAs in Arabidopsis do not show sequence similarity to any other sequences in the genome, a second model of miRNA origin was proposed (de Felippes et al. 2008). This model postulates that MIR genes are born randomly from the numerous inverted repeats in the genome. Fortuitous new miRNA-target interactions would be selected in evolution to determine whether the new miRNAs are retained or lost.

Once a MIR gene is born, it is subjected to evolutionary forces that shape the genome. One such evolutionary event is gene duplication. miRNAs that are conserved among diverse species tend to belong to gene families with more than one member (Fahlgren et al. 2007). Young miRNAs belong to families with a single or small number of members and tend to be expressed at lower levels relative to conserved miRNAs (Fahlgren et al. 2007).

One question that arises is to what extent functional overlap or distinction among members of a conserved miRNA family exists. For most conserved miRNA families, functions have not been ascribed to individual members of the family using loss-of-function alleles in each family member. For the three-member miR164 family, however, loss (or reduction)-of-function alleles of individual family members have been studied (Baker et al. 2005, Guo et al. 2005, Mallory et al. 2004a, Nikovics et al. 2006, Sieber et al. 2007). This family targets a group of genes encoding NAC domain transcription factors, such as NAC1, CUC1, and CUC2 (Baker et al. 2005, Guo et al. 2005, Laufs et al. 2004, Sieber et al. 2007). Single mutants in MIR164a and MIR164b genes show elevated NAC1 mRNA levels and have roots with more branches (Guo et al. 2005). Although the two genes have similar functions, the fact that each single mutant displays a root phenotype indicates that each has a function that cannot be replaced by the other. Whereas a miR164b mutant has no developmental abnormalities in the aerial portion, a mir164c mutant named eep has extra petals in early flowers (Baker et al. 2005, Mallory et al. 2004a). Mutations in MIR164a and MIR164b enhance the floral defects of eep, which suggests that miR164a and miR164b also act in floral patterning (Sieber et al. 2007). In addition, a mir164a mutant exhibits enhanced leaf serration (Nikovics et al. 2006). Therefore, the three MIR164 genes have over-lapping as well as distinct functions. For the three-member miR159 family, a single mutant in MIR159a or MIR159b does not have obvious developmental phenotypes, but the double mutant exhibits severe developmental defects, which indicates redundancy between the two genes (Allen et al. 2007).

Modes of Action: At the Molecular Level

Plant miRNAs regulate target mRNAs by two major mechanisms: transcript cleavage and translational inhibition. Plant miRNAs guide the cleavage of their target mRNAs at the phosphodiester bond opposite to the 10th and 11th nucleotides of the miRNA in the miRNA-mRNA duplex (Llave et al. 2002b). The cleavage is mediated by the endonuclease activity of AGO1 (Baumberger & Baulcombe 2005, Qi et al. 2005). Most miRNAs are associated with AGO1 in vivo, and target mRNAs accumulate to a higher level in ago1 mutants (Qi et al. 2006, Vaucheret et al. 2004), which indicates that AGO1 executes the cleavage of miRNA targets.

Plant miRNAs also cause translational inhibition of target mRNAs, as evidenced by disproportionate effects on mRNA and protein levels of their targets. Although the lack of antibodies precluded determination of protein levels for most plant miRNA target genes, in all instances where target genes have been examined at the protein level using antibodies, a discrepancy in mRNA and protein levels has been documented, which indicates that these miRNAs cause translational inhibition of their target mRNAs in addition to cleavage (Aukerman & Sakai 2003, Bari et al. 2006, Chen 2004, Gandikota et al. 2007). The isolation of mutants that specifically abolish miRNA-mediated translational inhibition further establishes the notion that translational inhibition is a widespread mode of action for plant miRNAs (Brodersen et al. 2008). AGO1, AGO10, a microtubule-severing enzyme, and P-body components are all required for miRNA-mediated translational inhibition (Brodersen et al. 2008). One possibility is that miRNAs trigger the sequestration of miRNA target mRNAs in P-bodies, thus preventing their translation.

Modes of Action: At the Cell or Tissue Level

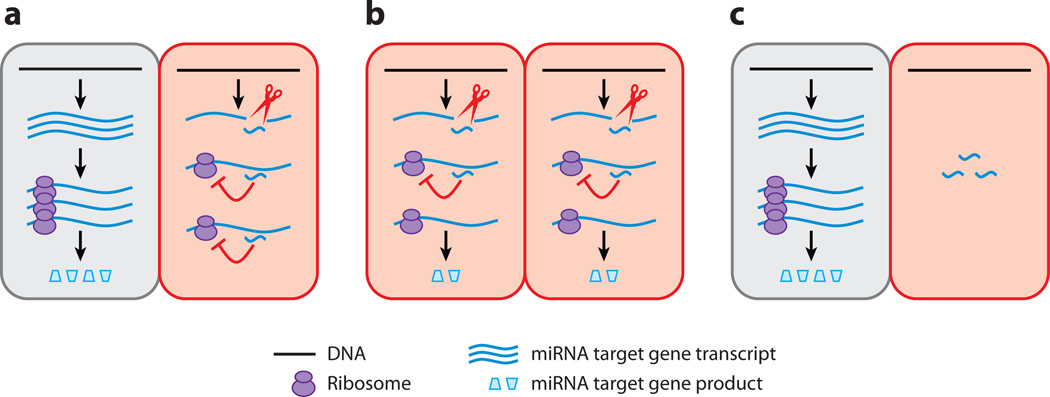

Several strategies have been employed to refine gene expression through miRNA-mediated repression in plants (Figure 2). The first, and perhaps the most publicized, mode of action of a miRNA is the restriction of target gene expression to regions where the miRNA is not present. This can be achieved not only by clearing the target mRNA through cleavage, but also through translational inhibition. Second, several miRNAs, such as miR169 in petunia and Antirrhinum and miR172 in Arabidopsis, are present in the same domains as their target mRNAs (Cartolano et al. 2007, Chen 2004, Jofuku et al. 1994). These miRNAs dampen the expression of their target genes in their natural domain of expression. Quantitative differences in target gene expression resulting from miRNA-mediated regulation can translate into qualitative differences in developmental outputs. Finally, miRNAs may serve as a backup to ensure highly specific patterns of target gene expression conferred primarily through regulated transcription. For example, sulfur starvation induces the expression of miR395 and one of its target genes, SULTR2;1, in different cell types in the vascular system (Kawashima et al. 2009). The miRNA probably does not affect the expression of this target gene in its native domain but ensures its lack of expression outside of the native domain.

Figure 2.

Modes of action of plant miRNAs at the tissue level. (a) A miRNA restricts the domain of expression of its target gene. The target gene is transcribed in two adjacent domains, but the miRNA restricts the products of the target gene to one of them. (b) A miRNA reduces target gene expression in its native domain. (c) miRNA serves as an insurance mechanism to limit target gene expression to a domain conferred largely by transcriptional regulation. The rectangles represent two adjacent tissue domains; the ones with the miRNA are shaded red.

Regulation of General miRNA Homeostasis

miRNA biogenesis as well as the function of miRNAs is under feedback regulation. DCL1 is under negative regulation by two mechanisms. First, DCL1 mRNA is a target of miR162 and undergoes miR162-mediated cleavage (Xie et al. 2003). Second, DCL1 pre-mRNA harbors the pre-miR838 hairpin, and DCL1-mediated processing of DCL1 pre-mRNA to release pre-miR838 results in nonproductive fragments of DCL1 pre-mRNA (Rajagopalan et al. 2006). Both mechanisms result in posttranscriptional repression of DCL1 expression, but they sense different inputs. The first mechanism requires miRNA activity and probably monitors the overall functional levels of miRNAs in the cell. The second mechanism does not require miRNA function and probably monitors the level of DCL1 activity in the nucleus. Intriguingly, a similar feedback mechanism to regulate Drosha activity has been uncovered in animals. Two conserved hairpins resembling pre-miRNAs are present in the mRNA of DGCR8, the partner of Drosha, in mammals. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex cleaves DGCR8 mRNA as if it were a pri-miRNA to control the homeostasis of miRNA biogenesis (Han et al. 2009). AGO1, which encodes the major effector protein in the miRISC, is itself under the control of miR168 (Vaucheret et al. 2004).

Regulation of Abundance or Activity of Specific miRNAs

The biogenesis of miRNAs must be highly regulated, as suggested by the fact that many miRNAs accumulate in a spatiotemporally regulated manner or in response to environmental stimuli. For example, miR172, which promotes floral transition in Arabidopsis and vegetative phase transition in maize, gradually increases in abundance as the plant develops (Lauter et al. 2005, Park et al. 2002). In flowers, miR172 is not present in the inflorescence meristem but is present throughout stage 1 floral meristem adjacent to the inflorescence meristem, and is enriched in the inner two whorls later in flower development (Chen 2004). Other examples include miR395 and miR399, which are induced by sulfur- and phosphate-limiting conditions, respectively (Chiou et al. 2006, Fujii et al. 2005, Kawashima et al. 2009).

Transcriptional regulation contributes to regulated accumulation of individual miRNAs. Because MIR genes are transcribed by Pol II, the transcription is presumably controlled by the same mechanisms that govern the regulation of protein-coding genes. These mechanisms include, but are not limited to, activation or repression by transcription factors, chromatin remodeling proteins, or epigenetic marks such as histone modifications and DNA methylation. Indeed, several transcription factors have been demonstrated to promote miRNA accumulation in response to environmental stimuli. A Myb transcription factor, PHOSPHATE STARVATION RESPONSE 1 (PHR1), promotes the expression of MIR399 genes in response to Pi starvation (Bari et al. 2006). Another transcription factor, SLIM, is required for the activation of MIR395 under sulfur starvation (Kawashima et al. 2009). SPL7 (SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE7) binds to specific motifs in the promoters of MIR398 genes to activate their expression under low-copper conditions (Yamasaki et al. 2009).

The accumulation of individual miRNAs can presumably be regulated at any of the posttranscriptional processing, modification, or degradation steps. The accumulation of mouse let-7 miRNA is regulated by LIN-28 at a post-transcriptional step, either pri-let-7 processing or stability of pre-let-7, or both (Heo et al. 2008, Viswanathan et al. 2008).

The activities of individual miRNAs can also be modulated. In mammals, an RNA-binding protein, Dnd1, inhibits the access of a few miRNAs to their targets (Kedde et al. 2007). Target mimicry is a form of regulation of miRNA activity uncovered in Arabidopsis. The activity of miR399 is regulated by a class of noncoding RNAs that pairs with miR399, but with mismatches opposite to positions 10 and 11 in the miRNA (Franco-Zorrilla et al. 2007). These noncoding RNAs cannot be cleaved by miR399 but sequester it to negatively affect its function. Replacing the miR399-complementary region in the noncoding RNAs with noncleavable sequences that base pair with other miRNAs results in reduction of the activities of these miRNAs, which suggests that target mimicry can be used as a general strategy to downregulate the activities of miRNAs (Franco-Zorrilla et al. 2007, Wang et al. 2008).

TRANS-ACTING siRNAs

Biogenesis

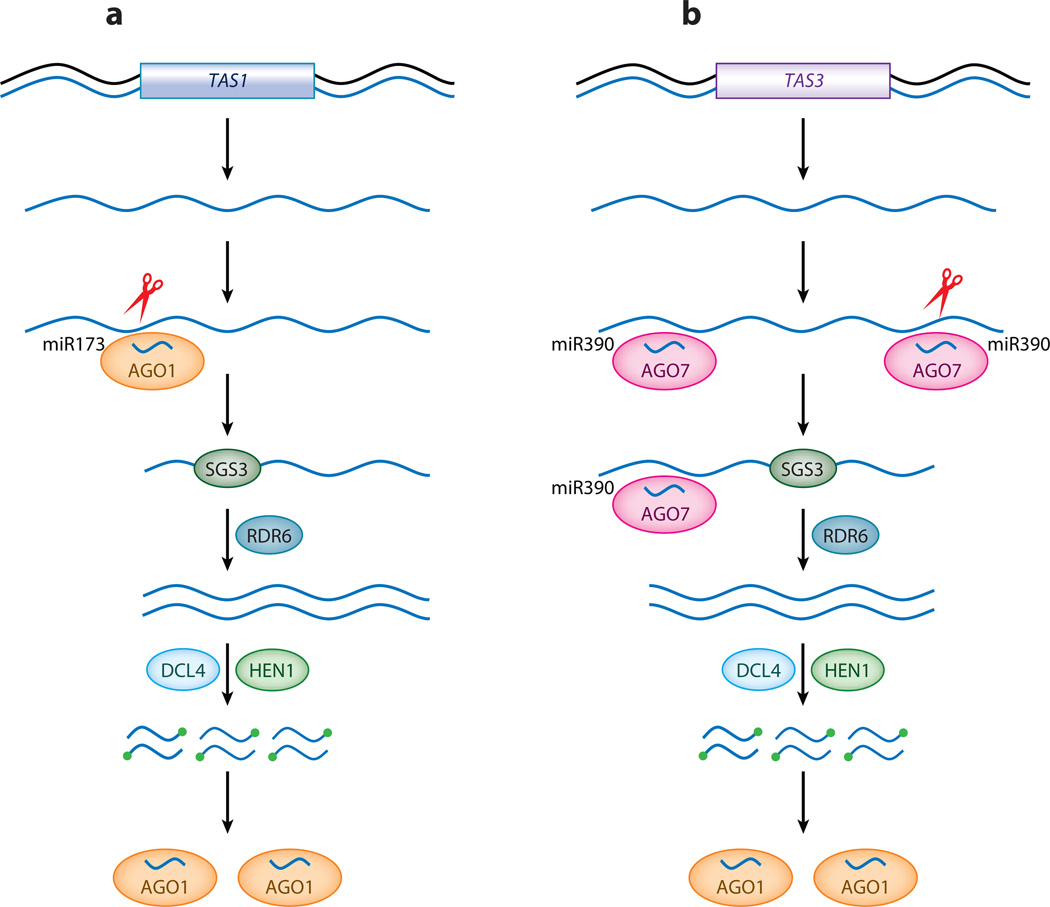

The biogenesis of ta-siRNAs is an example of crosstalk among different small RNA pathways (Figure 3). It is initiated by miRNA-mediated cleavage of noncoding transcripts from several TAS loci (miR173 for TAS1 and TAS2, miR390 for TAS3, and miR828 for TAS4) (Allen et al. 2005, Peragine et al. 2004, Rajagopalan et al. 2006, Vazquez et al. 2004b, Yoshikawa et al. 2005). The cleaved RNAs are probably bound and stabilized by SGS3 and copied into dsRNAs by RDR6. The dsRNAs are cleaved in multiple rounds by DCL4 from the end defined by miRNA-mediated cleavage such that the ta-siRNAs are in 21-nt register from the cleavage site. The ta-siRNAs are loaded into an effector complex that contains AGO1 (Baumberger & Baulcombe 2005).

Figure 3.

Biogenesis of ta-siRNAs. (a) At the TAS1 locus, long noncoding transcripts are cleaved by miR173/AGO1, and the 3′ cleavage products are presumably bound by SGS3 and copied into dsRNAs by RDR6. The dsRNAs are processed into siRNAs by DCL4 in a step-wise manner from the end defined by the initial cleavage. (b) At the TAS3 locus, long noncoding transcripts are recognized at two sites by miR390/AGO7, which cleaves the transcripts only at the 3′ site. The 5′ cleavage products are channeled into ta-siRNA production by SGS3, RDR6, and DCL4. TAS1, trans-acting siRNA locus 1; TAS3, trans-acting siRNA locus 3; AGO1, ARGONAUTE1; AGO7, ARGONAUTE7; SGS3, SUPPRESSOR OF GENE SILENCING 3; RDR6, RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE6; dsRNAs, double-stranded RNAs; siRNAs, small interfering RNAs; DCL4, DICER-LIKE4; HEN1, HUA ENHANCER1; ta-siRNA, trans-acting siRNA; miR173, microRNA173; miR390, microRNA390.

Although the framework of ta-siRNA biogenesis has been established, a major question that remains to be addressed is how the TAS transcripts are channeled to ta-siRNA production, whereas many transcripts targeted for cleavage by various miRNAs are not. Studies of synthetic ta-siRNAs based on the TAS1 and TAS3 loci have shown that miRNA-mediated cleavage alone is not sufficient to trigger ta-siRNA biogenesis (Montgomery et al. 2008a,b). For example, replacing the miR173 site in TAS1c with a miR171 site compromises efficient ta-siRNA production, although miR171 does lead to cleavage of the engineered TAS1c transcript. The TAS3 noncoding transcript harbors two sites that interact with miR390/AGO7 (Figure 3). Whereas the cleavage function of miR390-AGO7 at the 3′ site can be replaced by AGO1 if the 3′ miR390 site is engineered to be recognized by another miRNA, the function of miR390-AGO7 at the 5′ noncleavable site cannot be substituted by AGO1. Therefore, miR390 and miR173 have unique, currently unknown molecular functions in ta-siRNA biogenesis. Perhaps they recruit RDR6 to the cleaved TAS transcripts through proteins that are specific to their miRISCs.

Cell-to-Cell Movement

Like miRNAs, ta-siRNAs regulate target transcripts by causing their cleavage and, perhaps, translational inhibition. The only ta-siRNAs with well-defined biological functions are the tasiR-auxin response factors (ARFs) from the TAS3 locus (Adenot et al. 2006, Fahlgren et al. 2006, Garcia et al. 2006, Hunter et al. 2006). These siRNAs target transcripts of two auxin response factor genes, ARF3 and ARF4, which promote abaxial identity and the expression of adult traits in leaves.

Because ta-siRNAs and miRNAs have similar molecular and developmental functions, one wonders why ta-siRNAs, which require a complicated biogenesis pathway, are employed for functions that can theoretically be carried out by miRNAs. One possible advantage of ta-siRNAs over miRNAs is that ta-siRNAs may be able to move from cell to cell such that they have the potential to act as signaling molecules in development. A study in which the activity of miR171 was monitored with a reporter gene showed that miR171 acts in a cell autonomous manner (Parizotto et al. 2004). Studies with artificial miRNAs synthesized with pre-miRNA backbones in a spatially restricted manner also indicate that miRNAs act cell autonomously (Alvarez et al. 2006, Tretter et al. 2008). For example, when an artificial miRNA is produced in phloem companion cells, its effects in repression of its target PDS gene, loss of function which results in photobleaching, are not observed in mesophyll cells surrounding the phloem. On the other hand, DCL4-generated PDS siRNAs from a hairpin transgene expressed from the same phloem-specific promoter do exert their effects in a domain encompassing 5–15 cells away from the source of siRNA biogenesis (Dunoyer et al. 2005). In situ hybridization revealed that tasiR-ARFs are localized in a gradient along the adaxial-abaxial axis in leaf primordia despite strictly adaxial expression of TAS3 and the ta-siRNA biogenesis gene AGO7, which suggests that tasiR-ARFs, synthesized on the adaxial side dissipate along the adaxial-abaxial axis (Chitwood et al. 2009).

DEVELOPMENTAL FUNCTIONS OF miRNAs AND ta-siRNAs

A large portion of the conserved miRNAs regulates target genes that encode transcription factors with roles in developmental patterning. Consistent with the role of many miRNAs in developmental regulation, miRNA biogenesis mutants such as dcl1, hyl1, se, hen1, ddl, and mutants in AGO1 have pleiotropic developmental defects (reviewed in Ramachandran & Chen 2008b).

Phase Transitions

miR156 is one of the most ancient miRNAs found in perhaps all land plant lineages (reviewed in Axtell & Bowman 2008). In Arabidopsis, miR156 targets 11 of the 17 SPL genes; among these genes, SPL3, 4, and 5 promote vegetative phase change as well as floral transition, and SPL9 and SPL15 regulate plastochron length (Schwab et al. 2005, Wang et al. 2008, Wu & Poethig 2006). Overexpression of miR156 results in prolonged expression of juvenile characters and extremely delayed flowering. In maize, the dominant Corngrass1 (Cg1) mutant has a prolonged vegetative phase due to overproduction of miR156 (Chuck et al. 2007).

miR172 regulates genes encoding AP2-domain transcription factors. In Arabidopsis, miR172 promotes flowering by repressing TOE1 and TOE2 (Aukerman & Sakai 2003). In maize, one of the miR172 targets is the Glossy15, a gene with a well-documented role in vegetative phase change (Lauter et al. 2005). Intriguingly, the maize Cg1 mutant that overexpresses miR156 has reduced miR172 levels, which suggests that miR156 and miR172 may act in a linear pathway that coordinates vegetative and floral transitions (Chuck et al. 2007).

Hormone Biosynthesis and Signaling

In Arabidopsis, miR159 targets MYB33, MYB65, and MYB101, genes related to GAMYB, a barley Myb gene that activates Gibberellin-responsive (GA) genes in the aleurone layer (Millar & Gubler 2005, Reyes & Chua 2007). Although these Myb genes have not been demonstrated to mediate GA signaling, they act in developmental processes that require GA, such as flowering under short days and male fertility. Overexpression of miR159 leads to reduced levels of MYB33 and MYB65 mRNAs and male sterility as well as delayed flowering under short days (Achard et al. 2004, Millar & Gubler 2005). During seed germination, miR159 represses the expression of MYB33 and MYB101, and overexpression of miR159 or mutations in MYB33 and MYB101 lead to abscisic acid hyposensitivity (Reyes & Chua 2007).

Several small RNAs target genes with roles in auxin signaling. miR160, miR167, and tasiR-ARFs all target ARF genes. The regulation of ARF10, ARF16, and ARF17 by miR160 appears to be important in many aspects of shoot and root development. Expression of miR160-resistant ARF10, ARF16, or ARF17 leads to pleiotropic developmental defects in all aerial organs and, when examined, in roots (Liu et al. 2007, Mallory et al. 2005, Wang et al. 2005). ARF6 and ARF8, targeted by miR167, act redundantly to regulate ovule and anther development. Expression of miR167-resistant ARF6 leads to arrested ovule development and indehiscent anthers (Wu et al. 2006). ta-siRNAs from the TAS3 locus target ARF3 and ARF4, which promote abaxial identity of lateral organs as well as the expression of adult vegetative traits in leaves (Adenot et al. 2006, Fahlgren et al. 2006, Garcia et al. 2006, Hunter et al. 2006). NAC1, regulated by miR164, mediates auxin signaling in lateral root emergence (Guo et al. 2005). miR393 targets TIR1, encoding an auxin receptor and related F-box genes (Jones-Rhoades & Bartel 2004).

miR319 represses the biosynthesis of the plant hormone jasmonic acid (Schommer et al. 2008). LIPOXYGENASE2 (LOX2), which encodes a chloroplast enzyme that catalyzes the first dedicated step in jasmonic acid biosynthesis, is likely a direct target of TCP4, which is in turn targeted by miR319.

Pattern Formation and Morphogenesis

miR164

miR164-mediated regulation of CUC1 and CUC2 is important for the proper establishment of organ boundaries throughout plant development, floral patterning, and leaf morphogenesis (Baker et al. 2005, Laufs et al. 2004, Mallory et al. 2004a, Nikovics et al. 2006, Sieber et al. 2007).

miR165/166 and tasiR-ARFs

In both Arabidopsis and maize, miR165/166 targets homeodomain-leucine zipper transcription factor genes to promote abaxial identity of lateral organs (Emery et al. 2003, Juarez et al. 2004, Mallory et al. 2004b, McConnell et al. 2001). miR165/166, enriched in the abaxial side of leaf primordia, causes the mRNAs of its target genes to be concentrated in the adaxial side where these genes specify adaxial characteristics. Point mutations in the miRNA target site of the Arabidopsis PHB and REV genes as well as the maize homolog of REV, rld, circumvent the cleavage of the mRNAs by miR165/166, are dominant, and lead to adaxialization of leaves.

tasiR-ARFs promote adaxial identity through repression of ARF3 and ARF4, although the extent to which tasiR-ARFs contribute to adaxial identity specification varies in different organisms. In Arabidopsis, mutants in the ta-siRNA biogenesis pathway genes do not exhibit obvious lateral organ polarity defects, probably owing to the existence of parallel mechanisms to control adaxial identity (Garcia et al. 2006). In maize, mutations in leafbladeless (lbl ), the homolog of Arabidopsis SGS3 required for ta-siRNA biogenesis, result in abaxialization of leaves (Nogueira et al. 2007). lbl and tasiR-ARFs are localized on the adaxial side of leaf primordia and probably promote adaxial fate by restricting the expression of MIR165/166, perhaps indirectly through the ARFs. Therefore, two small RNAs, tasiR-ARF and miR165/166, show opposite polar distribution in leaf primordia and establish the adaxial-abaxial axis in leaf development.

Adaxial-abaxial axis establishment is intimately linked to the formation of the shoot apical meristem during embryogenesis. Simultaneous loss of function of three homeodomain-leucine zipper genes (PHB, PHV, and REV) in Arabidopsis prevents the formation of the shoot apical meristem (Emery et al. 2003). In rice, mutations in ta-siRNA biogenesis genes (SHL2, SHO2, and SHO1, the homologs of Arabidopsis RDR6, AGO7, and DCL4, respectively) prevent the formation of the shoot apical meristem (Nagasaki et al. 2007).

miR169

miR169 in Petunia hybrida and Antirrhinum majus controls the spatial restriction of the homeotic class C genes that specify the identities of the reproductive organs in the flower (Cartolano et al. 2007). In the miR169 mutants, ectopic expression of the class C genes in the outer whorls transforms petals into stamens. miR169 targets NF-YA genes that are likely activators of class C gene expression. The localization patterns of miR169 in floral primordia coincide with those of the class C RNAs. This makes it unlikely that miR169 clears the transcripts of NF-YA in the outer floral whorls. Instead, it most likely dampens NF-YA expression in its natural domain. Although miR169 exists in Arabidopsis, the function of restricting class C gene expression appears to have been delegated to the transcription factor gene APETALA2 (AP2) (Drews et al. 1991), but a similar role for miR169 cannot be ruled out.

miR172

In Arabidopsis, one of the miR172 targets, AP2, specifies the identities of the perianth organs, sepals, and petals in the flower (Aukerman & Sakai 2003, Chen 2004). Intriguingly, AP2 mRNA is uniformly present in all four floral whorls ( Jofuku et al. 1994), unlike other floral homeotic genes whose RNAs are confined to two of the whorls in which they function. Because miR172-mediated regulation of AP2 occurs mainly at the translational level, it is possible that AP2 protein is more concentrated in the outer two floral whorls owing to the repression by miR172.

miR319

miR319 was first identified from an activation-tagging mutant in which a viral enhancer leads to overexpression of this miRNA, which results in crinkly leaves (Palatnik et al. 2003). miR319 targets five Arabidopsis TCP genes that presumably control cell divisions during leaf morphogenesis.

miR824

miR824 is a newly evolved miRNA found only in Brassicaceae, and it regulates pattern formation during stomatal development by targeting the MADS-box gene AGL16 (Kutter et al. 2007).

HETEROCHROMATIC siRNAs

Thousands of loci in Arabidopsis produce endogenous small RNAs that are not miRNAs or ta-siRNAs. Some of these endogenous siRNAs are produced from natural sense-antisense transcript pairs and are called nat-siRNAs (Borsani et al. 2005, Katiyar-Agarwal et al. 2006). The great majority of endogenous siRNAs identified so far constitute heterochromatic siRNAs that guide DNA methylation and histone methylation machineries to homologous loci for transcriptional gene silencing (Kasschau et al. 2007, Lu et al. 2005, Mosher et al. 2008, Xie et al. 2004, Zhang et al. 2007). These siRNAs are usually 24 nt in length and tend to be produced from repeats and transposable elements, although many are also found in intergenic regions.

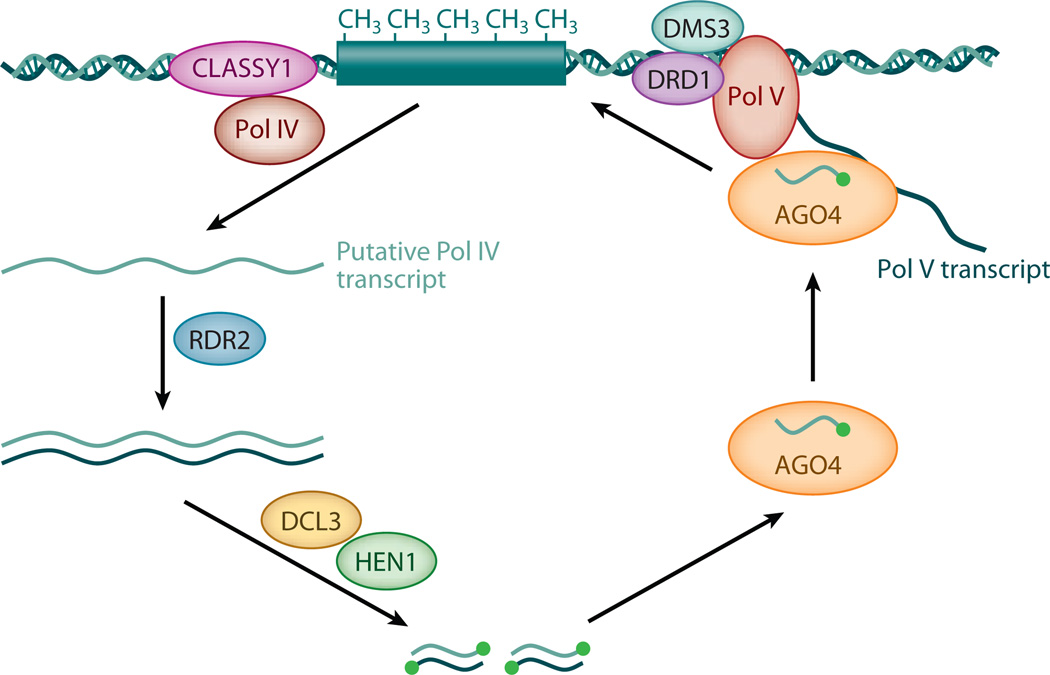

Biogenesis

The production of heterochromatic siRNAs requires a specialized polymerase, Pol IV, and a potential chromatin remodeling protein, CLASSY1 (Herr et al. 2005, Kanno et al. 2005, Onodera et al. 2005, Smith et al. 2007) (Figure 4). It is thought that Pol IV transcribes heterochromatic regions to produce transcripts that are channeled into siRNA production, although Pol IV–dependent transcripts have yet to be identified. RDR2 is another essential gene in the biogenesis of heterochromatic siRNAs (Xie et al. 2004), and it likely generates dsRNAs using Pol IV transcripts as templates. The dsRNAs are then processed into 24-nt siRNAs by DCL3 (Xie et al. 2004). In the absence of DCL3, other DCL proteins can process these dsRNAs into 21-nt and 22-nt siRNAs (Kasschau et al. 2007).

Figure 4.

Biogenesis and function of heterochromatic siRNAs. Heterochromatic loci are presumably transcribed by Pol IV into single-stranded noncoding transcripts that are copied into dsRNAs by RDR2. Twenty-four–nt siRNAs are processed from the dsRNAs by DCL3, methylated by HEN1, and loaded into AGO4-containing RISCs. The siRNAs are recruited to the source loci by transcripts generated by Pol V and perhaps by interaction between Pol V and AGO4. Through unknown mechanisms, DNA and/or histone methyltransferases are recruited by the RISCs to effect heterochromatin formation and subsequent siRNA production in a feed-forward loop. The transcription activities of Pol IV and Pol V are aided by chromatin remodeling proteins CLASSY1 and DRD1, respectively. Pol IV, DNA-dependent RNA polymerase IV; Pol V, DNA-dependent RNA polymerase V; CLASSY, a protein similar to chromatin remodeling proteins; AGO4, ARGONAUTE4; RDR2, RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE2; DCL3, DICER-LIKE3; HEN1, HUA ENHANCER1; dsRNAs, double-stranded RNAs; siRNAs, small interfering RNAs, RISCs, RNA-induced silencing complexes; DRD1, DEFECTIVE IN RNA-DIRECTED DNA METHYLATION1; DMS3, DEFECTIVE IN MERISTEM SILENCING3.

Another polymerase, Pol V, is essential for siRNA-mediated DNA methylation (Kanno et al. 2005, Pontier et al. 2005). It also promotes siRNA accumulation at some but not all loci (Kanno et al. 2005, Mosher et al. 2008, Pontier et al. 2005). It is thought that the main function of Pol V is to methylate DNA or histone at the siRNA-generating loci, and its role in promoting siRNA levels is an indirect effect because DNA and histone methylation may in turn mark these regions for siRNA production in a feed-forward loop.

Pol V generates noncoding transcripts that encompass heterochromatic loci, and these transcripts probably recruit heterochromatic siRNAs to these loci (Wierzbicki et al. 2008). DRD1, a potential chromatin remodeling protein, and DMS3, a structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) hinge-domain protein, are required for the production of Pol V transcripts and for siRNA-mediated heterochromatin formation (Kanno et al. 2004, 2008; Wierzbicki et al. 2008, 2009).

Whereas the great majority of endogenous siRNAs disappear in a Pol IV mutant, some still exist (Mosher et al. 2008). These siRNAs may be produced from other polymerases such as Pol I, II, and III.

Function

Genome integrity

The major function of heterochromatic siRNAs is to maintain genome integrity by silencing transposable elements. Heterochromatic siRNAs of 24 nt are bound by AGO4 (Qi et al. 2006). Loss-of-function mutations in AGO4 result in loss of DNA methylation, histone H3K9 methylation, and derepression of heterochromatic loci (Xie et al. 2004, Zilberman et al. 2003). AGO4 exhibits slicer activity, which is required for DNA methylation at some but not all loci (Qi et al. 2006). AGO6, a close homolog of AGO4, also plays a role in transcriptional gene silencing (Zheng et al. 2007). It is not known how DNA methyltransferases and histone H3K9 methyltransferases are recruited by AGO4/siRNAs.

Regulation of gene expression

Do heterochromatic siRNAs, which tend to be derived from repeats and transposable elements, regulate genes and play a role in development? siRNAs that match to the vicinity of protein-coding genes have been documented to control the expression of these genes with visible effects on plant development. In Arabidopsis, a transposable element inserted in an intron of the FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) gene results in small-RNA-triggered histone H3K9 methylation that spreads into the FLC coding region and reduces FLC expression and early flowering (Liu et al. 2004). The endosperm-specific FWA gene is silenced in other tissues by DNA methylation in the promoter (Soppe et al. 2000). Loss of promoter methylation results in FWA expression and late flowering. Two tandem repeats in the promoter of the FWA gene spawn siRNAs that trigger DNA methylation (Chan et al. 2006). SDC, a gene encoding an F-box protein, contains in its promoter seven tandem repeats, which spawn siRNAs that trigger DNA methylation and transcriptional gene silencing (Henderson & Jacobsen 2008). Loss of SDC silencing results in serrated leaves. Despite these examples of heterochromatic siRNAs regulating protein-coding genes with developmental consequences, loss-of-function mutations in key siRNA biogenesis genes, such as Pol IV subunits and RDR2, do not show obvious developmental defects. One explanation is that the heterochromatic marks triggered by siRNAs can be maintained in siRNA-independent ways. In fact, one should be mindful that siRNA-independent mechanisms that maintain heterochromatin, the initiation of which requires siRNAs, may mask the role of siRNAs in the regulation of gene expression when studying mutants compromised in siRNA pathways. Another explanation is that few repeats or transposons are sufficiently close to genes to influence nearby gene expression in Arabidopsis. In fact, in maize, the genome of which is loaded with repeats and transposons, heterochromatic siRNA pathway mutants show stochastic developmental defects (Alleman et al. 2006, Dorweiler et al. 2000, Erhard et al. 2009).

THREE MAJOR TYPES OF SMALL RNAs.

The three major types of small RNAs, miRNA, siRNA, and piRNA, are distinguished by their different modes of biogenesis. miRNAs and siRNAs are processed from precursors by the RNase III endonuclease Dicer, which acts on double-stranded substrates to release small RNA duplexes with 2-nt 3′ overhangs. The small RNA duplexes are then unwound to generate single-stranded miRNAs or siRNAs. siRNAs are generated from long dsRNAs, which usually give rise to multiple siRNA species from both strands. miRNAs are derived from single-stranded RNA precursors that form hairpin structures. The miRNA and the miRNA* are the most predominant species from a precursor. piRNAs are derived from presumably single-stranded precursors in a Dicer-independent manner. Despite different modes of biogenesis, the three types of small RNAs share similar molecular functions. For example, all three types can direct the cleavage of complementary RNAs. miRNAs and siRNAs can both result in translational inhibition of target mRNAs. siRNAs and piRNAs can both direct chromatin modifications.

SUMMARY POINTS.

Small RNAs are sequence-specific guides in nucleic acid–based processes, such as DNA and histone methylation and posttranscriptional regulation at the RNA level.

Small RNAs are invariably bound by argonaute proteins, some of which have endonuclease activity to effect small RNA–guided cleavage of target mRNAs. Argonaute proteins belong to at least two phylogenetic groups, the argonaute subfamily, which binds miRNAs and siRNAs, and the piwi subfamily, which binds piRNAs.

Plant miRNAs are generated from longer precursors in at least two sequential processing steps primarily through the activities of DCL1 and are bound primarily by AGO1. Exceptions exist where DCL4 and AGO7 synthesize and bind, respectively, certain miRNAs.

Plant miRNAs regulate target mRNAs through transcript cleavage and/or translational inhibition.

Plant miRNAs evolve rapidly such that nonbroadly conserved miRNAs represent the majority of miRNA species in any organism.

Conserved miRNAs play crucial roles in almost all aspects of plant development. Two major mechanisms of action have been revealed so far. Some miRNAs refine or restrict the expression patterns of the target mRNAs or proteins such that the target genes are only expressed in cells where the miRNAs are not. Other miRNAs are coexpressed with their target genes and dampen the expression of their targets.

Plants are rich in endogenous siRNAs, which can be classified into several types, such as ta-siRNA, nat-siRNA, and heterochromatic siRNAs, although the distinctions can be blurry. ta-siRNAs require particular miRNAs for their biogenesis. tasiR-ARFs regulate auxin response factor genes and play crucial roles in adaxial-abaxial polarity specification and meristem initiation, especially in maize and rice.

Heterochromatic siRNAs derived from transposons and repeated sequences guide heterochromatin formation at the source loci to maintain genome stability. The role of these siRNAs in the regulation of protein-coding genes may be underestimated owing to the existence of siRNA-independent mechanisms that maintain heterochromatin.

FUTURE ISSUES.

The regulation of miRNA biogenesis or activity will be a major area of interest. Is the processing of specific miRNAs regulated? Are the activities of specific miRNAs regulated?

The molecular mechanisms underlying the activities of miRNAs are still poorly understood. For example, what determines when an miRNA inhibits the translation of its target mRNA rather than cleaving it? How does an miRNA inhibit the translation of its target mRNA?

The current strategies used to predict miRNA targets rely on extensive base pairing between miRNAs and their target mRNAs, a requirement for slicing. A recent study suggests that the pairing rules that govern translational inhibition may be different (Dugas & Bartel 2008). The repertoire of miRNA targets may be much broader if the base-pairing requirement for translational inhibition is looser, as in animal miRNA-target interactions.

The biological functions of the great majority of plant miRNAs, including almost all nonconserved miRNAs in Arabidopsis and almost all miRNAs in other plants, have yet to be uncovered. Even for many conserved miRNAs, their functions were inferred from phenotypes conferred by expression of miRNA-resistant targets. These studies do not address the functions of the miRNAs fully because (a) not all targets may be known for any miRNAs (especially when the base-pairing requirements for translational inhibition are unknown) and (b) the mutations may abolish only transcript cleavage but not translational inhibition, as has been demonstrated in one case (Dugas & Bartel 2008). Therefore, loss-of-function mutants in the MIR genes are necessary to garner a complete picture of their functions.

Is it true that miRNAs are immobile whereas ta-siRNAs are mobile? If so, what bestows the mobility differences?

It remains to be understood how miR173, miR390, and miR824 are uniquely able to trigger the biogenesis of ta-siRNAs.

Many mysteries lay in the biogenesis of heterochromatic siRNAs. Future investigations will address how only some loci spawn siRNAs, a question that is probably intimately linked to the enzymatic activity of Pol IV and the recruitment of Pol IV to specific loci. Future investigations will also address how siRNAs help recruit DNA methyltransferases and histone H3K9 methyltransferases to specific loci. The role of heterochromatic siRNAs in regulation of protein gene expression should be further examined.

Mechanisms underlying the inheritance and/or resetting of siRNA-triggered epigenetic modifications through meiosis need to be worked out.

Glossary

- dsRNA

double-stranded RNA

- RNA silencing

a broad term that refers to RNA-mediated sequence-specific silencing of genes

- Cleavage/slicing

small RNA-guided cleavage of the target mRNA in the middle of the small RNA/mRNA complementary region

- Small interfering RNA (siRNA)

a class of small RNAs derived from long double-stranded RNAs

- microRNA (miRNA)

a class of small RNAs processed from hairpin precursors in a precise manner as the most predominant species

- Translational inhibition

the phenomenon whereby a small RNA leads to disproportionate reduction in target protein and mRNA levels

- piRNA

piwi-interacting RNA

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex; usually refers to the RNA-protein complex in which an siRNA resides

- AGO

argonaute

- Trans-acting siRNA (ta-siRNA)

a class of endogenous siRNAs that regulates target genes bearing little resemblance to the ta-siRNA loci

- Pol II (IV or V)

DNA-dependent RNA polymerase II (IV or V)

- RdRP

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- Heterochromatic siRNA

a class of small RNAs that guides DNA and H3K9 methyation at homologous chromatin

- DCL

Dicer-like

- pri-miRNA

the primary miRNA precursor, which contains a local stem-loop structure with the miRNA embedded within the stem

- pre-miRNA

the stem-loop immediate precursor to a miRNA

- miRISC

the RISC containing an miRNA

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The author is not aware of any biases that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

LITERATURE CITED

- Achard P, Herr A, Baulcombe DC, Harberd NP. Modulation of floral development by a gibberellin-regulated microRNA. Development. 2004;131:3357–3365. doi: 10.1242/dev.01206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adenot X, Elmayan T, Lauressergues D, Boutet S, Bouche N, et al. DRB4-dependent TAS3 trans-acting siRNAs control leaf morphology through AGO7 . Curr. Biol. 2006;16:927–932. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleman M, Sidorenko L, McGinnis K, Seshadri V, Dorweiler JE, et al. An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is required for paramutation in maize. Nature. 2006;442:295–298. doi: 10.1038/nature04884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E, Xie Z, Gustafson AM, Carrington JC. microRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell. 2005;121:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E, Xie Z, Gustafson AM, Sung GH, Spatafora JW, Carrington JC. Evolution of microRNA genes by inverted duplication of target gene sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:1282–1290. doi: 10.1038/ng1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen RS, Li J, Stahle MI, Dubroue A, Gubler F, Millar AA. Genetic analysis reveals functional redundancy and the major target genes of the Arabidopsis miR159 family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:16371–16376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707653104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez JP, Pekker I, Goldshmidt A, Blum E, Amsellem Z, Eshed Y. Endogenous and synthetic microRNAs stimulate simultaneous, efficient, and localized regulation of multiple targets in diverse species. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1134–1151. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.040725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V, Lee RC, Lavanway A, Williams PT, Jewell D. MicroRNAs and other tiny endogenous RNAs in C. elegans . Curr. Biol. 2003;13:807–818. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aukerman MJ, Sakai H. Regulation of flowering time and floral organ identity by a microRNA and its APETALA2-like target genes. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2730–2741. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ, Bowman JL. Evolution of plant microRNAs and their targets. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CC, Sieber P, Wellmer F, Meyerowitz EM. The early extra petals1 mutant uncovers a role for microRNA miR164c in regulating petal number in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari R, Datt Pant B, Stitt M, Scheible WR. PHO2, microRNA399, and PHR1 define a phosphate-signaling pathway in plants. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:988–999. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.079707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumberger N, Baulcombe DC. Arabidopsis ARGONAUTE1 is an RNA slicer that selectively recruits microRNAs and short interfering RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11928–11933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505461102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsani O, Zhu J, Verslues PE, Sunkar R, Zhu JK. Endogenous siRNAs derived from a pair of natural cis-antisense transcripts regulate salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2005;123:1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen P, Sakvarelidze-Achard L, Bruun-Rasmussen M, Dunoyer P, Yamamoto YY, et al. Widespread translational inhibition by plant miRNAs and siRNAs. Science. 2008;320:1185–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.1159151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartolano M, Castillo R, Efremova N, Kuckenberg M, Zethof J, et al. A conserved microRNA module exerts homeotic control over Petunia hybrida and Antirrhinum majus floral organ identity. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:901–905. doi: 10.1038/ng2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SW, Zhang X, Bernatavichute YV, Jacobsen SE. Two-step recruitment of RNA-directed DNA methylation to tandem repeats. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. A microRNA as a translational repressor of APETALA2 in Arabidopsis flower development. Science. 2004;303:2022–2025. doi: 10.1126/science.1088060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou TJ, Aung K, Lin SI, Wu CC, Chiang SF, Su CL. Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by microRNA in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:412–421. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.038943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood DH, Nogueira FTS, Howell MD, Montgomery TA, Carrington JC, Timmermans MCP. Pattern formation via small RNA mobility. Genes Dev. 2009;23:549–554. doi: 10.1101/gad.1770009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuck G, Cigan AM, Saeteurn K, Hake S. The heterochronic maize mutant Corngrass1 results from overexpression of a tandem microRNA. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:544–549. doi: 10.1038/ng2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curaba J, Chen X. Biochemical activities of Arabidopsis RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 6. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:3059–3066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708983200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmay T, Hamilton A, Rudd S, Angell S, Baulcombe DC. An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene in Arabidopsis is required for posttranscriptional gene silencing mediated by a transgene but not by a virus. Cell. 2000;101:543–5453. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80864-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Felippes FF, Schneeberger K, Dezulian T, Huson DH, Weigel D. Evolution of Arabidopsis thaliana microRNAs from random sequences. RNA. 2008;14:2455–2459. doi: 10.1261/rna.1149408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deleris A, Gallego-Bartolome J, Bao J, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC, Voinnet O. Hierarchical action and inhibition of plant Dicer-like proteins in antiviral defense. Science. 2006;313:68–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1128214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Pendon JA, Li F, Li WX, Ding SW. Suppression of antiviral silencing by cucumber mosaic virus 2b protein in Arabidopsis is associated with drastically reduced accumulation of three classes of viral small interfering RNAs. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2053–2063. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.047449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djupedal I, Portoso M, Spahr H, Bonilla C, Gustafsson CM, et al. RNA Pol II subunit Rpb7 promotes centromeric transcription and RNAi-directed chromatin silencing. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2301–2306. doi: 10.1101/gad.344205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaire L, Barajas D, Martinez-Garcia B, Martinez-Priego L, Pagan I, Llave C. Structural and genetic requirements for the biogenesis of tobacco rattle virus-derived small interfering RNAs. J. Virol. 2008;82:5167–5177. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00272-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorweiler JE, Carey CC, Kubo KM, Hollick JB, Kermicle JL, Chandler VL. Mediator of paramutation1 is required for establishment and maintenance of paramutation at multiple maize loci. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2101–2118. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drews GN, Bowman JL, Meyerowitz EM. Negative regulation of the Arabidopsis homeotic gene AGAMOUS by the APETALA2 product. Cell. 1991;65:991–1002. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90551-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas DV, Bartel B. Sucrose induction of Arabidopsis miR398 represses two Cu/Zn superoxide dismutases. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008;67:403–417. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunoyer P, Himber C, Voinnet O. DICER-LIKE 4 is required for RNA interference and produces the 21-nucleotide small interfering RNA component of the plant cell-to-cell silencing signal. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1356–1360. doi: 10.1038/ng1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shami M, Pontier D, Lahmy S, Braun L, Picart C, et al. Reiterated WG/GW motifs form functionally and evolutionarily conserved ARGONAUTE-binding platforms in RNAi-related components. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2539–2544. doi: 10.1101/gad.451207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery JF, Floyd SK, Alvarez J, Eshed Y, Hawker NP, et al. Radial patterning of Arabidopsis shoots by class III HD-ZIP and KANADI genes. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1768–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhard KF, Jr, Stonaker JL, Parkinson SE, Lim JP, Hale CJ, Hollick JB. RNA polymerase IV functions in paramutation in Zea mays. Science. 2009;323:1201–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1164508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard M, Boutet S, Morel JB, Bellini C, Vaucheret H. AGO1, QDE-2, and RDE-1 are related proteins required for post-transcriptional gene silencing in plants, quelling in fungi, and RNA interference in animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000;97:11650–11654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200217597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlgren N, Howell MD, Kasschau KD, Chapman EJ, Sullivan CM, et al. High-throughput sequencing of Arabidopsis microRNAs: evidence for frequent birth and death of MIRNA genes. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlgren N, Montgomery TA, HowellM D, Allen E, Dvorak SK, et al. Regulation of AUXINRESPONSE FACTOR3 by TAS3 ta-siRNA affects developmental timing and patterning in Arabidopsis . Curr. Biol. 2006;16:939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Spector DL. Identification of nuclear dicing bodies containing proteins for microRNA biogenesis in living Arabidopsis plants. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans . Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco-Zorrilla JM, Valli A, Todesco M, Mateos I, Puga MI, et al. Target mimicry provides a new mechanism for regulation of microRNA activity. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1033–1037. doi: 10.1038/ng2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H, Chiou TJ, Lin SI, Aung K, Zhu JK. A miRNA involved in phosphate-starvation response in Arabidopsis . Curr. Biol. 2005;15:2038–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka Y, Utsumi M, Ohba Y, Watanabe Y. Location of a possible miRNA processing site in SmD3/SmB nuclear bodies in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:1243–1253. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga R, Doudna JA. dsRNA with 5′ overhangs contributes to endogenous and antiviral RNA silencing pathways in plants. EMBO J. 2009;28(5):545–555. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusaro AF, Matthew L, Smith NA, Curtin SJ, Dedic-Hagan J, et al. RNA interference-inducing hairpin RNAs in plants act through the viral defence pathway. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:1168–1175. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandikota M, Birkenbihl RP, Hohmann S, Cardon GH, Saedler H, Huijser P. The miRNA156/157 recognition element in the 3′ UTR of the Arabidopsis SBP box gene SPL3 prevents early flowering by translational inhibition in seedlings. Plant J. 2007;49:683–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D, Collier SA, Byrne ME, Martienssen RA. Specification of leaf polarity in Arabidopsis via the trans-acting siRNA pathway. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:933–938. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasciolli V, Mallory AC, Bartel DP, Vaucheret H. Partially redundant functions of Arabidopsis DICER-like enzymes and a role for DCL4 in producing trans-acting siRNAs. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1494–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzani S, Lawrenson T, Woodward C, Headon D, Sablowski R. A link between mRNA turnover and RNA interference in Arabidopsis . Science. 2004;306:1046–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.1101092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:94–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory BD, O’Malley RC, Lister R, Urich MA, Tonti-Filippini J, et al. A link between RNA metabolism and silencing affecting Arabidopsis development. Dev. Cell. 2008;14:854–866. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo HS, Xie Q, Fei JF, Chua NH. microRNA directs mRNA cleavage of the transcription factor NAC1 to downregulate auxin signals for Arabidopsis lateral root development. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1376–1386. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.030841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AJ, Baulcombe DC. A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science. 1999;286:950–952. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Pedersen JS, Kwon SC, Belair CD, Kim YK, et al. Posttranscriptional crossregulation between Drosha and DGCR8. Cell. 2009;136:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MH, Goud S, Song L, Fedoroff N. The Arabidopsis double-stranded RNA-binding protein HYL1 plays a role in microRNA-mediated gene regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:1093–1098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307969100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon GJ. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE. Tandem repeats upstream of the Arabidopsis endogene SDC recruit non-CG DNA methylation and initiate siRNA spreading. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1597–1606. doi: 10.1101/gad.1667808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo I, Joo C, Cho J, Ha M, Han J, Kim VN. Lin28 mediates the terminal uridylation of let-7 precursor microRNA. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr AJ, Jensen MB, Dalmay T, Baulcombe DC. RNA polymerase IV directs silencing of endogenous DNA. Science. 2005;308:118–120. doi: 10.1126/science.1106910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herr AJ, Molnar A, Jones A, Baulcombe DC. Defective RNA processing enhances RNA silencing and influences flowering of Arabidopsis . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14994–15001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606536103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Jones AM, Searle I, Patel K, Vogler H, et al. An atypical RNA polymerase involved in RNA silencing shares small subunits with RNA polymerase II. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:91–93. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C, Willmann MR, Wu G, Yoshikawa M, de la Luz Gutierrez-Nava M, Poethig SR. Transacting siRNA-mediated repression of ETTIN and ARF4 regulates heteroblasty in Arabidopsis . Development. 2006;133:2973–2981. doi: 10.1242/dev.02491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G, Simard MJ. Argonaute proteins: key players in RNA silencing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:22–32. doi: 10.1038/nrm2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jofuku KD, den Boer BG, Van Montagu M, Okamuro JK. Control of Arabidopsis flower and seed development by the homeotic gene APETALA2 . Plant Cell. 1994;6:1211–1225. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.9.1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP. Computational identification of plant microRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juarez MT, Kui JS, Thomas J, Heller BA, Timmermans MC. microRNA-mediated repression of rolled leaf1 specifies maize leaf polarity. Nature. 2004;428:84–88. doi: 10.1038/nature02363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T, Bucher E, Daxinger L, Huettel B, Bohmdorfer G, et al. A structural-maintenance-of-chromosomes hinge domain-containing protein is required for RNA-directed DNA methylation. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:670–675. doi: 10.1038/ng.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T, Huettel B, Mette MF, Aufsatz W, Jaligot E, et al. Atypical RNA polymerase subunits required for RNA-directed DNA methylation. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:761–765. doi: 10.1038/ng1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T, Mette MF, Kreil DP, Aufsatz W, Matzke M, Matzke AJ. Involvement of putative SNF2 chromatin remodeling protein DRD1 in RNA-directed DNA methylation. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:801–805. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasschau KD, Fahlgren N, Chapman EJ, Sullivan CM, Cumbie JS, et al. Genome-wide profiling and analysis of Arabidopsis siRNAs. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e57. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katiyar-Agarwal S, Morgan R, Dahlbeck D, Borsani O, Villegas A, Jr, et al. A pathogen-inducible endogenous siRNA in plant immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18002–18007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608258103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Goto DB, Martienssen RA, Urano T, Furukawa K, Murakami Y. RNA polymerase II is required for RNAi-dependent heterochromatin assembly. Science. 2005;309:467–469. doi: 10.1126/science.1114955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima CG, Yoshimoto N, Maruyama-Nakashita A, Tsuchiya YN, Saito K, et al. Sulphur starvation induces the expression of microRNA-395 and one of its target genes but in different cell types. Plant J. 2009;57:313–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedde M, Strasser MJ, Boldajipour B, Oude Vrielink JA, Slanchev K, et al. RNA-binding protein Dnd1 inhibits microRNA access to target mRNA. Cell. 2007;131:1273–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Wang D, Ruvkun G. A conserved siRNA-degrading RNase negatively regulates RNA interference in C. elegans . Nature. 2004;427:645–649. doi: 10.1038/nature02302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutter C, Schob H, Meins F, Jr, Si-Ammour A. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of stomatal development in Arabidopsis . Plant Cell. 2007;19:2417–2429. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294:853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahmy S, Pontier D, Cavel E, Vega D, El-Shami M, et al. PolV(PolIVb) function in RNA-directed DNA methylation requires the conserved active site and an additional plant-specific subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(3):941–946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810310106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans . Science. 2001;294:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1065062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubinger S, Sachsenberg T, Zeller G, Busch W, Lohmann JU, et al. Dual roles of the nuclear capbinding complex and SERRATE in pre-mRNA splicing and microRNA processing in Arabidopsis thaliana . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8795–8800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufs P, Peaucelle A, Morin H, Traas J. microRNA regulation of the CUC genes is required for boundary size control in Arabidopsis meristems. Development. 2004;131:4311–4322. doi: 10.1242/dev.01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauter N, Kampani A, Carlson S, Goebel M, Moose SP. microRNA172 down-regulates glossy15 to promote vegetative phase change in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9412–9417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503927102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14 . Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, et al. microRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CF, Pontes O, El-Shami M, HendersonI R, Bernatavichute YV, et al. An ARGONAUTE4-containing nuclear processing center colocalized with Cajal bodies in Arabidopsis thaliana . Cell. 2006;126:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Yang Z, Yu B, Liu J, Chen X. Methylation protects miRNAs and siRNAs from a 3′-end uridylation activity in Arabidopsis . Curr. Biol. 2005;15:1501–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, He Y, Amasino R, Chen X. siRNAs targeting an intronic transposon in the regulation of natural flowering behavior in Arabidopsis . Genes Dev. 2004;18:2873–2878. doi: 10.1101/gad.1217304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PP, Montgomery TA, Fahlgren N, Kasschau KD, Nonogaki H, Carrington JC. Repression of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR10 by microRNA160 is critical for seed germination and post-germination stages. Plant J. 2007;52:133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]