Abstract

Latino parents can experience acculturation stressors, and according to the Family Stress Model, parent stress can influence youth mental health and substance use by negatively affecting family functioning. To understand how acculturation stressors come together and unfold over time to influence youth mental health and substance use outcomes, the current study investigated the trajectory of a latent parent acculturation stress factor and its influence on youth mental health and substance use via parent-and youth-reported family functioning. Data came from a six-wave, school-based survey with 302 recent (< 5 years) immigrant Latino parents (74% mothers, M age = 41.09 years) and their adolescents (47% female, M age = 14.51 years). Parents’ reports of discrimination, negative context of reception, and acculturative stress loaded onto a latent factor of acculturation stress at each of the first four time points. Earlier levels of and increases in parent acculturation stress predicted worse youth-reported family functioning. Additionally, earlier levels of parent acculturation stress predicted worse parent-reported family functioning and increases in parent acculturation stress predicted better parent-reported family functioning. While youth-reported positive family functioning predicted higher self-esteem, lower symptoms of depression, lower aggressive and rule-breaking behavior in youth, parent-reported family positive functioning predicted lower youth alcohol and cigarette use. Findings highlight the need for Latino youth preventive interventions to target parent acculturation stress and family functioning.

Keywords: Latino families, acculturation stress, youth mental health, substance use

Latino youth constitute a large and growing population in the United States (U.S.), and they report disproportionately higher rates of depressive symptoms and use of substances (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014; CDC, 2014). Specifically, national estimates indicate that, compared to non-Latino White and African American/Black youth, Latinos report elevated symptoms of depression (CDC, 2014), higher rates of suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts (CDC, 2014), greater likelihood of cigarette and alcohol use (Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2015), and higher prevalence of aggressive and delinquent behavior (Gibson & Miller, 2010). The majority of Latino children are first (11%) or second (52%) generation immigrants, and immigration is expected to be a significant driving force behind Latino population growth (Bernstein, 2013; Fry & Passel, 2009). Scholars and theory suggest that parents likely experience acculturation stress1 associated with immigration, a negative context of reception, and acculturative changes in language, identities, values (Leon, 2014; Schwartz et al., 2015; Tran, 2014). Moreover, according to the Family Stress Model, these sociocultural stressors may disrupt parenting and family relationships, thereby, negatively affecting youth mental health and substance use outcomes (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010).

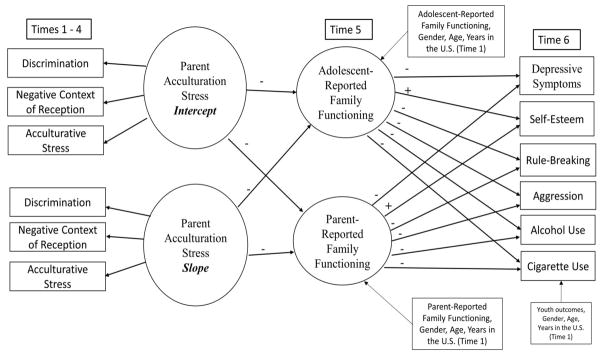

Many Latino parents decide to immigrate to the U.S. to improve their children’s future (Perreira, Chapman, & Stein, 2006). Unfortunately, once in the U.S., they may face anti-immigrant attitudes and policies, which may hinder families’ social mobility, thereby adversely affecting the health and well-being for their families (Halim, Yoshikawa, & Amodio, 2013; Pearlin, 1999; Schwartz et al., 2015; Tran, 2014). Indeed, acculturation stress in the form of discrimination, a negative context of reception, and acculturative stress among Latinos has been documented (Cano et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2014, 2015; Torres, Discoll, & Voell, 2012), and research supports a significant association between Latino youth-reported acculturation stressors and Latino youth mental health and substance use (e.g., Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2011; Schwartz et al., 2014, 2015). However, few studies have investigated how parent perceptions of acculturation stress may impact the mental health and substance use of their adolescent children (Leon, 2014; Tran, 2014). Accordingly, informed by the Family Stress Model (FSM), the present study investigates how trajectories of parent acculturation stress among recent immigrant Latino parents impact adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning. We further examine how adolescent-and parent-reported family functioning, in turn, influences youth mental health and substance use outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model.

Acculturation Stressors and Latino Youth Mental Health and Substance Use

Acculturation stressors relevant for U.S. Latino families include discrimination, a negative context of reception, and acculturative stress (Schwartz et al., 2015). These stressors have been linked with disrupted family functioning (Sarmiento & Cardemil, 2009; Trail, Goff, Bradbury, & Karney, 2012) and negative mental health and substance use outcomes among Latino youth (Schwartz et al., 2015). Discrimination refers to perceived daily experiences of unfair or differential treatment, such as receiving poor service in restaurants or being treated unfairly for having an accent when speaking English (Perez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008). A negative context of reception refers to the degree to which Latinos feel unwelcomed in their receiving context and include the opportunity structures available for immigrants in the U.S. such as having access to good employment and schools (Schwartz et al., 2014). Acculturative stress refers to stressors associated with the acculturation process, where acculturation refers to the changes that first or later generation immigrant Latino youth and parents experience when they come into continuous contact with their U.S. receiving culture (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). Acculturative stress can include the pressures of learning a new language, maintaining the native language, balancing differing cultural values, and brokering between American and Latino ways of behaving (Torres, Discoll, & Voell, 2012).

Among Latino youth, discrimination, a negative context of reception, and acculturative stress have been linked with elevated symptoms of depression (Cano et al., 2015), cigarette smoking (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2011), alcohol use (Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000), and lower self-esteem (Schwartz et al., 2015). Moreover, in cross-sectional research with ethnically diverse families, parents’ experiences with discrimination and acculturative stress were associated with more internalizing and externalizing behaviors in children (Leon, 2014; Tran, 2014). These findings suggest that Latino parents’ acculturation stressors may affect Latino youth well-being. Few longitudinal studies, however, have investigated how Latino parents’ acculturation stress experiences influence their children’s mental health and substance use.

The Family Stress Model (FSM)

The FSM provides a theoretical framework for understanding the pathways by which parent acculturation stress may influence youth mental health and substance use. FSM posits that over time parent acculturation stressors may lead to disruptions in family functioning, which, in turn, may be associated with more mental health and substance use problems in youth (Conger et al., 2010). Although FSM was originally developed to understand how financial hardships experienced by parents influence family processes and youth outcomes, it has since been extended to investigate how experiences of discrimination and neighborhood risk of Latino parents influences family functioning to affect youth development (e.g., Conger et al., 2012). Additionally, in research with Latino couples, discrimination (Trail et al., 2012) and acculturative stress (Sarmiento & Cardemil, 2009) negatively impacted marital relationships, suggesting that, for Latino families, acculturation stressors may lead to disrupted family functioning. Also, studies with Latino youth indicate that family functioning can affect their mental health (Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2012; Zayas, 2011). These studies suggest that FSM is a useful theoretical model for understanding the process by which parent acculturation stress influences family functioning to affect Latino youth mental health and substance use.

From Parent Acculturation Stress to Youth Outcomes

Based on the literature reviewed above, we developed the conceptual model depicted in Figure 1, in which parent acculturation stress (intercept and slope) predicts adolescent- and parent reported family functioning, which then predicts youth mental health and substance use. First, we investigated the degree to which family functioning mediated the effects of parent acculturation stress trajectories on a range of youth mental health and substance use outcomes among a sample of recent-immigrant Latino parents and their adolescents. Identifying mediating pathways from parent acculturation stress to youth mental health and substance use is important because it can provide information about areas for prevention and intervention efforts. Surveying recent immigrant Latino families longitudinally allows for the investigation of how acculturation stress develops as Latino immigrant families navigate the U.S. cultural context, and it provides insights into effective timing of interventions to prevent the negative consequences of acculturation stress. Second, we included reports of family functioning for adolescents and parents because parents and youth often differ in how they experience family relationships (Larson & Richards, 1994). Third, we examined the extent to which discrimination, a negative context of reception, and acculturative stress co-occurred in the lives of recent Latino immigrant parents. Although these three acculturation stressors are often treated as unique constructs, evidence indicates that they represent a larger construct of acculturation stress. For example, their conceptualization and measurement suggest that they are interrelated and likely all contribute to the overall stress experience of Latinos in the U.S. (Schwartz et al., 2015). Given Schwartz et al.’s (2015) finding that such a latent construct could be extracted for adolescents, we sought to determine whether it would also emerge among parents. As such, we investigated their co-occurrence and the stability of this co-occurrence over time.

We included a range of mental health and substance use outcomes, including self-esteem, symptoms of depression, aggressive and rule-breaking behavior, cigarette smoking, and alcohol use. The inclusion of a range of outcomes allows for a more comprehensive evaluation of the relationship between parent acculturation stress and adolescent outcomes – outcomes for which health disparities exist between Latino and non-Latino White adolescents. We propose the following hypotheses:

The three acculturation stressors will cluster onto a latent construct at each of the four time points.

Earlier levels of and increases in parent acculturation stress will predict lower youth- and parent-reported family functioning at Time 5.

Youth- and parent-reported family functioning at Time 5 will predict youth mental health and substance use outcomes at Time 6. Specifically, we expected low family functioning (for adolescent and parents) to predict higher levels of depressive symptoms, lower self-esteem, more aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors, and more cigarette and alcohol use.

Family functioning (Time 5) will mediate the effect of parent acculturation stress (earlier levels of and change in) on youth outcomes.

Method

Sample

Data came from a six-wave longitudinal study on acculturation, acculturation stress, family functioning, and health among recent Latino immigrant families (Schwartz et al., 2014). The sample consisted of 302 adolescent-caregiver dyads from Los Angeles (N = 150) and Miami (N = 152) who had resided in the U.S. for five years or less at baseline. Nine cases were removed from the analyses because different caregivers participated across time points (i.e., Father at times 1 to 4 and Mother at times 5 and 6). Among the remaining sample (N = 293), about half the adolescents (47%) were female, and the baseline mean adolescent age was 14.51 years (SD = 0.88). Each adolescent participated with a primary caregiver, which we refer to as parent for simplicity. Parents included mothers (74.0%), fathers (22.1%), stepparents (2.1%), and grandparents/other relatives (1.7%). The baseline mean parent age was 41.09 years (SD = 7.09). About 80% of parents reported annual incomes of less than $25,000, and 78.6% were high school graduates. Miami families were from predominantly from Cuba (61%), the Dominican Republic (8%), Nicaragua (7%), Honduras (6%), and Colombia (6%). Los Angeles families were predominantly from Mexico (70%), El Salvador (9%), and Guatemala (6%). Almost all of the adolescents (98%) and parents (98%) reported Spanish as their “first or usual language.”

Procedures

School selection and participant recruitment

Families were recruited from 23 randomly selected, predominantly Hispanic schools in Miami-Dade and Los Angeles Counties (10 in Miami and 13 in Los Angeles). Our goal was to recruit 25 students per school for a total of 150 families per site. In cases where a school did not provide at least 25 students, we recruited additional students from another nearby high school. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Miami and the University of Southern California, and by the Research Review Committees for each school district.

Latino students were recruited from English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes, as well as from the overall student body. Interested students provided their parent/guardian’s phone number. We obtained contact information for 632 students and their parents. Of these 632 families, 435 were reachable by phone, whereas the remaining 197 were unreachable due to incorrect or non-working telephone numbers. Of the 435 families reached by phone, 303 participated at baseline. The retention rate was 85% through all waves (92% in Miami and 77% in Los Angeles). A more detailed description of the school selection and participant recruitment is provided by Schwartz et al., 2014.

Assessment

Baseline (Time 1) data were gathered during the summer of 2010, and subsequent time points occurred during Spring 2011 (Time 2), Fall 2011 (Time 3), Spring 2012 (Time 4), Fall 2012 (Time 5), and Spring 2013 (Time 6). Participants completed assessments at the universities’ research centers, schools, community locations, or their homes. Assessments were available in Spanish and English, and participants completed assessments using an audio computer-assisted interviewing (A-CASI) system (Turner et al., 1998). Caregivers provided informed consent for themselves and their adolescents, and adolescents provided informed assent for themselves. As incentives, parents received $40 at baseline and an additional $5 at each subsequent time point. Adolescents received a voucher for a movie ticket at each time point.

Measures

Unless otherwise specified, 5-point Likert scales were used for all study measures, with response options ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Alpha coefficients presented are from the current sample at baseline. All scales were treated as sums.

Parent acculturation stress

Acculturation stress was measured using discrimination, negative context of reception, and acculturative stress at each of the first four time points. Discrimination was measured using the 7-item Perceived Discrimination Scale (Phinney, Madden, & Santos, 1998; α = .87; Sample item: “How often do people your age treat you unfairly or negatively because of your ethnic background?”). This measure uses a 5- point Likert response format ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Almost always). The mean discrimination score at Times 1 to 4 were as follows: M = 6.81, SD = 5.21 at Time 1; M = 6.85, SD = 6.02 at Time 2; M = 6.53, SD = 5.57 at Time 3; and M = 6.16, SD = 5.46 at Time 4. Negative context of reception was measured using the 6-item (α = .83; Sample items: “I don’t have the same chances in life as people from other countries” and “People from my country are not welcome here”). This scale was developed for this study and validated by Schwartz and colleagues (2014) and assessed the degree to which parents felt unwelcomed in their receiving community. The mean negative context of reception score at Times 1 to 4 were as follows: M = 10.67, SD = 4.87 at Time 1; M = 10.44, SD = 5.20 at Time 2; M = 10.44, SD = 5.13 at Time 3; and M = 9.65, SD = 4.91 at Time 4. Acculturative Stress was measured with the Multidimensional Acculturative Stress Inventory (24 items), which assess stress that originates from U.S. (sample item: “It bothers me that I speak English with an accent”) and Latino sources (sample item: “I feel pressure to speak Spanish”) (MASI; Rodriguez, Myers, Mira, Flores, & Garcia-Hernandez, 2002). Parents indicated on a scale, ranging from 0 (Not at all stressful) to 4 (Extremely stressful), the degree to which they each item applied to them (α = .93). The mean acculturative stress score at Times 1 to 4 were as follows: M = 5.62, SD = 4.08 at Time 1; M = 5.54, SD = 4.35 at Time 2; M = 5.52, SD = 4.64 at Time 3; and M = 5.37, SD = 4.34 at Time 4.

Family functioning

We assessed both adolescent and parent reports of family functioning using parent-adolescent (e.g., parental involvement and positive parenting) and whole-family relational processes (e.g., family cohesion). Parental involvement and positive parenting were assessed using the Parenting Practices Scale (Gorman-Smith, Tolan, Zelli, & Huesmann, 1996). The parental involvement subscale consisted of 15 items for adolescents (α = .87; Sample item: “When was the last time that you talked with your parents about what you were going to do for the coming day?”) and 19 items for parents (α = .79; Sample item: “How many of your child’s friends do you know?”). The positive parenting subscale consisted of 9 items for adolescents (α = .87; Sample item: “When you have done something that your parents approve, how often do they say something nice about it?”) and 9 for parents (α = .70; Sample item: “When your child has done something that you like or approve of do you mention it to someone else?”). Family cohesion was measured using the corresponding 6-items subscale from the Family Relations Scale (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1997). A sample item is “Family members feel very close to each other” (α = .87 for adolescents and .76 for parents). .

Depressive symptoms

We assessed depressive symptoms with 20 items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977); α = .93, sample item: “I felt like crying this week”. Adolescents indicated on a scale ranging from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree), how depressed they have felt during the past week. Higher scores indicate greater depressive symptoms. The mean depressive symptoms score was 29.77 (SD = 15.94) at baseline and 29.25 (SD = 14.86) at Time 6. The CES-D has been translated into Spanish and used frequently with Latinos (e.g., Todorova, Falcón, Lincoln, & Price, 2010).

Self-esteem

Self-esteem was assessed with 10 items (α = .74; Sample item: “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”) from the Rosenberg (1968) Self-Esteem Scale. The mean adolescent self-esteem score was 28.62 (SD = 5.26) at baseline and 29.78 (SD = 6.89) at Time 6. This measure has been used widely with Spanish-speaking populations (Schmidt & Allik, 2005).

Aggressive and rule-breaking behavior

We assessed adolescent aggressive and rule-breaking behavior with 32 items from the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, Dumenci, & Rescorla, 2002). Seventeen items measured aggressive behavior (α = .93, sample item: “I am mean to others”) and 15 items measured rule-breaking behavior (α = .93, sample item: “I break rules at home, school, or elsewhere”). The means for aggressive and rule-breaking behavior at baseline were 4.89 (SD = 5.30) and 3.59 (SD = 4.42), respectively. At Time 6, the means for aggressive and rule-breaking behavior were 4.58 (SD = 6.30) and 3.62 (SD = 5.18), respectively. Adolescents rated, on a scale ranging from 0 (Not true) to 2 (Often or very often true), their behavior within the previous six months.

Substance use

We assessed cigarette and alcohol use with a modified version of the Monitoring the Future survey (Johnston et al., 2015). We asked about the frequency of adolescents’ lifetime and past 90 day cigarette and alcohol use. Although it is most common to analyze substance use in the 30 days prior to assessment (Johnston et al., 2015), base rates were low (2.0%, N = 6 for cigarette smoking and 4.0%, N = 12 for alcohol use). We, therefore, conducted analyses using past 90-day cigarette and alcohol use at Times 1 (2.6 %, N = 8 and 7%, N = 20, respectively) and 6 (5.0%, N = 12 and 9%, N = 28, respectively). Adolescents were asked to indicate the frequency of cigarette or alcohol use in the past 90 days. Because of low base rates and the need to control for prior levels of these behaviors, we dichotomized the responses to create binary variables (1 = Use vs. 0 = Nonuse) at Times 1 and 6.

Analytic Overview

All analyses were conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Mplus (version 7.2; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007) using Maximum Likelihood with Robust Standard Errors (MLR), which is robust to non-normality and non-independence of observations when used with nested data. Specifically, MLR standard errors are computed using a sandwich covariance estimator (Kauermann & Carroll, 2001) which adjust standard errors to account for nesting of participants within schools. We accounted for nesting of participants in schools because the design effect for study variables ranged from 1 to 2.91, suggesting that nesting was an issue. Our analyses proceeded in three steps. First, we established longitudinal invariance among the three indicators of acculturation stress (i.e., discrimination, negative context of reception, and acculturative stress) across Times 1–4 using confirmatory factor analysis (Brown, 2006). We did so because latent growth curve modeling (LGCM) assumes that the same construct is assessed over time (Little, 2013). It is also important to ensure that longitudinal change in a latent construct is a result of true change (rather than the latent construct measuring something different at each time point) (Brown, 2006; Little, 2013). As such, we evaluated configural (equal form), metric (equal factor loadings), and scalar (equal item intercepts) invariance prior to longitudinal analysis. Model fit was evaluated using the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). According to values suggested by Little (2013), good model fit is represented as CFI ≥ .95, RMSEA ≤ .05, and SRMR ≤ .06; and adequate fit is represented as CFI ≥ .90, RMSEA ≤ .08, and SRMR ≤ .08. We compared the configural, metric, and scalar invariance models using the CFI (ΔCFI < .010) and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA < .010; Little, 2013). The assumption of longitudinal metric and scalar invariance would be satisfied if the ΔCFI < .01 and ΔRMSEA < .01. We report the chi-square difference test results, but did not use this index to evaluate model fit because it tends to be overpowered, producing significant differences in fit even when such differences are small (Meade, Johnson, & Braddy, 2008).

Second, we used LGCM to examine change in parent acculturation stress. Third, we tested a structural model to examine the effects of parent acculturation stress (i.e, intercept and slope using Times 1–4) on adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning at Time 5 and adolescent outcomes at Time 6. This model also examined the relationships of adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning at Time 5 with adolescent outcomes at Time 6. We centered the parent acculturation stress latent growth curve at Time 4, the time point closest to the mediator and outcome variables. We controlled for baseline age, years in the U.S., income, gender, adolescent outcomes, and parent-and youth-reported family functioning. Missing data were handled using MLR, which includes all available data and has been demonstrated to be superior to other missing data techniques (Muthen & Asparouhov, 2002).

Results

Longitudinal Invariance in Parent Acculturation Stress

Table 1 shows results of the longitudinal invariance testing. As shown in Table 2, the configural invariance model, according to Little’s (2013) criteria described above, fit the data well [χ2 (30) = 65.59, p < .001; CFI = .977; RMSEA = .064; SRMR = .043]. We then examined metric invariance by constraining factor loadings to equality across time and comparing this model with the configural invariance model. The assumption of metric variance was satisfied [Δχ2 (6) = 15.61, p < .05; ΔCFI = .006; ΔRMSEA = .001]. Next, we examined scalar invariance by constraining intercepts and factor loadings to equality across time and comparing this model against the metric invariance model. The assumption of scalar invariance was supported [Δχ2 (9) =11.58, p = .25; ΔCFI =.001; ΔRMSEA =.005]. Standardized factor loadings for discrimination, a negative context of reception, and acculturative stress were 0.829, 0.607, and 0.415, respectively. According to Brown (2006), standardized factor loadings of at least 0.30 or higher are acceptable in survey research, indicating acceptable factor loadings in this study. The squared standardized factor loadings or the “communality” represent the proportion of variance of each acculturation stressor accounted for by the acculturation stress latent factor. As such, it represents the common (versus unique) variance accounted for by the acculturation stress latent factor. Thus, the parent acculturation stress latent factor accounted for 69%, 37%, and 17% of the variance for discrimination, negative context of reception, and acculturative stress, respectively.

Table 1.

Model Fit and Comparison for Longitudinal Invariance Models

| χ2 (df) | Δχ2 (df) | CFI | ΔCFI | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal Form | 65.59 (30) | .977 | .064 | .043 | |||

| Equal Loading | 80.95 (36) | 15.61 (6)* | .971 | .006 | .065 | −.001 | .053 |

| Equal Intercept | 92.34 (45) | 11.58 (9) | .970 | .001 | .060 | .005 | .055 |

Note:

p < .05;

p < .001

Table 2.

Structural Path Estimates (Step 3)

| Effects of Parent Acculturation Stress on Family Functioning

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Predictor | Estimate | p-value | 95% CI |

| Parent Family Functioning T5 (57.1%) | Acculturation Stress (T4) | −0.21 | <.001 | −0.30, −0.11 |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | 0.08 | .022 | 0.01, 0.14 | |

| Parent Family Functioning T1 | 0.73 | <.001 | 0.70, 0.77 | |

| Adolescent Family Functioning T5 (51.5%) | Acculturation Stress (T4) | −0.12 | .005 | −0.20, −0.04 |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | −0.31 | <.001 | −0.39, −0.23 | |

| Adolescent Family Functioning T1 | 0.61 | <.001 | 0.53, 0.69 | |

|

| ||||

|

Effects of Parent Acculturation Stress and Family Functioning on Youth Outcomes

| ||||

| Outcome | Predictor | Estimate | p-value | 95% CI |

|

| ||||

| Self Esteem T6 (10.2%) | Self Esteem T1 | 0.21 | <.001 | .010, 0.31 |

| Acculturation Stress (T4) | −0.09 | .246 | −0.25, 0.06 | |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | 0.00 | .945 | −0.12, 0.13 | |

| Parent Family Functioning T5 | −0.04 | .384 | −0.12, 0.05 | |

| Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | 0.21 | .033 | 0.02, 0.39 | |

| Depression T6 (3.0%) | Depression T1 | 0.12 | .048 | 0.00, 0.23 |

| Acculturation Stress (T4) | −0.02 | .776 | −0.18, 0.13 | |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | −0.05 | .477 | −0.20, 0.09 | |

| Parent Family Functioning T5 | 0.01 | .895 | −0.10, 0.12 | |

| Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | −0.15 | .064 | −0.30, 0.01 | |

| Rule Break T6 (5.4%) | Rule Break T1 | 0.16 | .004 | 0.05, 0.27 |

| Acculturation Stress (T4) | 0.03 | .646 | −0.10, 0.16 | |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | −0.02 | .797 | −0.15, 0.11 | |

| Parent Family Functioning T5 | −0.10 | .144 | −0.23, 0.03 | |

| Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | −0.09 | .162 | −0.21, 0.03 | |

| Aggression T6 (5.5%) | Aggression T1 | 0.19 | <.001 | 0.08, 0.29 |

| Acculturation Stress (T4) | 0.07 | .451 | −0.10, 0.23 | |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | −0.09 | .121 | −0.19, 0.02 | |

| Parent Family Functioning T5 | −0.01 | .809 | −0.09, 0.07 | |

| Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | −0.11 | .034 | −0.22, −0.01 | |

| Cigarette Use T61 (17.8%) | Cigarette Use T1 | 15.20 | <.001 | 3.88, 59.45 |

| Acculturation Stress (T4) | 1.06 | .621 | 0.83, 1.4 | |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | 0.98 | .979 | 0.27, 3.60 | |

| Parent Family Functioning T5 | 0.62 | .036 | 0.40, 0.97 | |

| Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | 1.05 | .869 | 0.59, 1.88 | |

| Alcohol Use T61 (16.5%) | Alcohol Use T1 | 5.24 | .003 | 1.75, 15.72 |

| Acculturation Stress (T4) | 0.76 | .490 | 0.64, 0.90 | |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | 0.88 | .289 | 0.36, 2.14 | |

| Parent Family Functioning T5 | 0.94 | .027 | 0.74, 1.20 | |

| Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | 1.62 | .417 | 1.17, 2.24 | |

Notes.

Path estimates represent Odds Ratios. Percent of Variance Explained in Model provided in Parenthesis

Change in Parent Acculturation Stress

Next, we evaluated change in parent acculturation stress using LGCM. Because statistical tests of model fit in Mplus for LGCM apply the incorrect null model (Widaman & Thompson, 2003), we began with an intercept-only model (the correct null model). We then estimated a linear growth model. Models were compared against each other using the likelihood ratio test. Although both the intercept-only [χ2 (50) = 105.86, p < .001; CFI = .974; RMSEA = .054; SRMR = .056] and linear growth [χ2 (47) = 87.70, p = .003; CFI = .974; RMSEA = .054; SRMR = .056] models were associated with good fit, there was a significant difference between the linear curve model and the intercept model [Δ-2LL (3) = 18.43 p < .001]. As such, we retained the linear growth model. The model accounted for 84%, 79%, 71% and 98% of the variance observed in Parents’ Cultural Stress at Time 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively.

Results indicated a significant linear slope (x̄Slope = −0.185, p < .01), indicating that at each time point, there was an average decrease of 0.185 in parent acculturation stress. In addition, results indicated significant variability around the slope (SD = 0.70, p < .05, range: −1.43 – 1.48), suggesting that acculturation stress increased for some parents, decreased for other parents, or may have stayed the same. This variability around the slope permitted us to examine individual differences in how change in parent acculturation stress predicted family functioning and youth outcomes.

Effects of Parent Acculturation Stress on Family Functioning and Adolescent Outcomes & Effects of Family Functioning on Adolescent Outcomes

Next, we examined whether parent acculturation stress influenced adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning at Time 5 and adolescent outcomes at Time 6. We also investigated the effects of adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning at Time 5 on adolescent outcomes at Time 6. Adolescent- and parent-reported family functioning were operationalized as two separate latent variables consisting of parental involvement, positive parenting, and family cohesion. Because modeling categorical outcomes in MLR requires numerical integration and often leads to model nonconvergence, we saved the latent variable factor scores in Mplus and used them as observed variables in subsequent model tests. Moreover, because MLR does not provide fit indices when modeling categorical outcomes (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), we first estimated our structural model without the dichotomous outcomes to ascertain adequate model fit, before proceeding to include the categorical health risk outcomes. Consistent with Little’s (2013) suggested criteria, model fit indices indicated adequate fit: χ2 (80) = 197.53, p < .001; CFI = .908; RMSEA = .071; SRMR = .081. We then added the categorical outcomes.

Standardized path estimates for continuous and odds ratios for categorical outcome variables are displayed in Table 2. Additionally, as an indicator of effect size, the percent of variance accounted for each outcome in the model is provided in parenthesis. Values ranged from 3.0% to 57.1%. Higher parent acculturation stress at Time 4 (i.e., the intercept) predicted lower parent-reported family functioning at Time 5 (β = −0.21 p < .001, 95% CI [−0.30, −0.11]). In addition, change in parent acculturation stress (i.e., the slope) predicted greater parent-reported family functioning at Time 5 (β = 0.08, p < .05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.14]). That is, more positive change in parent acculturation stress predicted higher parent-reported family functioning. Moreover, higher parent-reported family functioning at Time 5, in turn, predicted lower likelihood of Time 6 adolescent smoking (OR = 0.62, p < .05, 95% CI [0.40, 0.98]) and drinking (OR = 0.94, p < .05, 95% CI [0.74, 0.98]). Additionally, higher parent acculturation stress at Time 4 (β = −0.12, p < .05, 95% CI [−0.20, −0.04]) and increases in parent acculturation stress (β = −0.31, p < .01, 95% CI [−0.39, −0.23]) predicted lower adolescent-reported family functioning at Time 5. Higher adolescent-reported family functioning, in turn, predicted higher adolescent self-esteem (β = 0.21, p < .05, 95% CI [0.02, 0.39]) and lower aggressive behavior (β = −0.11, p < .05, 95% CI [−0.22, −0.01] at Time 6. Higher adolescent-reported family functioning also predicted lower adolescent depressive symptoms at Time 6 (β = −0.14, p = .064, 95% CI [−0.30, 0.01]), but this effect was marginally significant. Parent acculturation stress did not directly predict any adolescent outcomes at Time 6.

Mediation Analyses

Consistent with hypothesis 4, we tested whether adolescent-and parent-reported family functioning mediated the effects of parent acculturation stress on youth mental health and substance use outcomes. We calculated 95% indirect confidence intervals and coefficients using the RMediation package (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011), which is based on the asymmetric distribution of products test (MacKinnon, 2008). As displayed in Table 3 (rows 1 and 2), higher parent acculturation stress at Time 4 predicted lower adolescent self-esteem (β = −0.02, p < .05, 95% CI [−0.046, −0.007] and more aggression (β = 0.01, p < .05, 95% CI [0.00, 0.032] at Time 6 through lower adolescent-reported family functioning at Time 5. Moreover, higher parent acculturation stress at Time 4 predicted greater odds of adolescent cigarette (OR = 1.1, p < .05, 95% CI [1.001, 1.240]) and alcohol use (OR = 1.06, p < .05, 95% CI [1.006, 1.123]) at Time 6, through lower parent-reported family functioning (Table 3, rows 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Significant Indirect Effects of Parents Acculturation Stress on Adolescent Outcomes

| Predictor | Mediator | Outcome | Lower | Middle | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acculturation Stress T4 | Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | Self Esteem T6 | −0.046 | −0.024 | −0.007 |

| Acculturation Stress T4 | Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | Aggression T6 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.03 |

| Acculturation Stress T4 | Parent Family Functioning T5 | Cigarette Use T61 | 1.001 | 1.103 | 1.240 |

| Acculturation Stress T4 | Parent Family Functioning T5 | Alcohol Use T61 | 1.006 | 1.059 | 1.123 |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | Self Esteem T6 | −0.096 | −0.063 | −0.035 |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | Depression T6 | 0.001 | 0.045 | 0.096 |

| Acculturation Stress (Change) | Adolescent Family Functioning T5 | Aggression T6 | 0.002 | 0.035 | 0.07 |

Notes.

Path estimates represent Odds Ratios

Additionally, as shown in Table 3 (rows 5, 6, and 7), greater increases in parent acculturation stress predicted lower adolescent self-esteem (β = −0.06, p < .05, 95% CI [−0.096, −0.035]), higher depressive symptoms (β = 0.045, p < .050, 95% CI [0.001, 0.096]) and higher aggression (β = 0.035, p < .050, 95% CI [0.002, 0.070] at Time 6 through lower adolescent-reported family functioning. Overall, mediation analyses suggest that higher parent acculturation stress may lead to lower adolescent self-esteem, higher depressive symptoms and higher aggressive behavior by compromising adolescent-reported family functioning. Additionally, compromised parent-reported family functioning seems to explain the relationships between higher parent acculturation stress and higher youth cigarette and alcohol use.

Discussion

Immigration to the U.S. is often motivated by parents’ desire to improve their children’s future (Perreira, Chapman, & Stein, 2006). However, once in the U.S., Latino parents can face acculturation stressors in the form of discrimination, acculturative stress, and a negative context of reception, which may compromise their family lives, thereby negatively influence the well-being of their children (Leo, 2014; Trail et al., 2012; Tran, 2014). To evaluate this theorized sequence of events, we utilized the Family Stress Model (FSM) to examine whether parent acculturation stress trajectories predict youth mental health and substance use outcomes through their effects on parent- and youth-reported family functioning. Consistent with the FSM, parent acculturation stress led to disruptions in positive family functioning (as reported by youth and their parents), which, in turn, negatively impacted the mental health and substance use of their adolescent children. Generally, our findings suggest that preventive interventions to improve the health of Latino youth need to consider the acculturation stress experiences of parents. Such efforts may also benefit from attending to youth and parent perceptions of family functioning. We now discuss in more detail the key findings and their implications.

We first evaluated the over-time latent structure of a parent acculturation stress construct. As hypothesized, discrimination, a negative context of reception, and acculturative stress loaded onto a latent parent acculturation stress variable, and the structure of this acculturation stress variable was consistent over the first four waves of the study. These findings suggested that the three parent acculturation stressors overlap, and this construct may have a consistent meaning over time. Prior studies have reported a parallel acculturation stress construct among Latino youth (Schwartz et al., 2015). We extend this work to recent immigrant Latino parents.

Longitudinal data allowed us to investigate the development of parent acculturation stress. Our data suggest that, on average, parent acculturation stress was highest within the first five years that parents settled into their receiving communities and decreased over time. These findings corroborate research on the development of acculturation stress in recent immigrant Latino youth, in which acculturation stress also decreased over time (Schwartz et al., 2015). Although earlier levels of and change in acculturation stress negatively influenced family functioning and Latino youth mental health and substance use, our data suggests that preventive interventions that focus on acculturation stress and/or family functioning may be especially beneficial during the first five years following immigration (when acculturation stress was highest), but can also be beneficial later in the settlement process.

Consistent with our hypothesis that parent acculturation stress would predict lower youth- and parent-reported family functioning, earlier levels of parent acculturation stress predicted lower youth- and parent-reported family functioning. These findings highlight a need to identify ways to reduce sources of acculturation stress for recent immigrant parents within the first five years of arriving to the U.S. and to work with parents to identify effective coping strategies before acculturation stressors negatively impact their families. Some parents may even benefit from learning how to cope with acculturation stress before they arrive in the U.S.

Although on average parent acculturation stress decreased over time, there was significant variance around the slope, suggesting that acculturation stress may have increased among some parents. Our results indicate that increases in parent acculturation stress can negatively impact youth-reported family functioning. These findings reinforce the need for intervention efforts to reduce acculturation stressors and to help Latino immigrant parents learn to cope with these stressors in ways that do not negatively impact the family. This finding is consistent with prior work on the negative impact of acculturation stressors on relationship functioning among Latino couples (Sarmiento & Cardemil, 2009; Trail et al., 2012), and this study documents the influence of parents’ acculturation stress on family functioning.

Surprisingly, increases in parent acculturation stress predicted more positive parent-reported family functioning. This finding is surprising because the FSM proposes that parent stress will lead to decreases in parent family functioning. It is possible that Latino immigrant parents actively respond to acculturation stressors by being more engaged in their parenting and family relationships as a way to protect their children from the harmful effects of acculturation stress. In a qualitative study with low-income Latina mothers, mothers reported responding to neighborhood poverty and violence by strictly monitoring their children, fostering strong parent-child communication, and always being aware of their children’s physical and emotional well-being (Ceballo, Kennedy, Bregman, & Epstein-Ngo, 2012). Similarly, in another qualitative study with Latino immigrant parents, parents discussed coping with discrimination their adolescents experienced by actively talking about these experiences with their adolescents, thereby fostering strong communication between parents and adolescents (Perreira et al., 2006). Thus, increases in parent acculturation stress may have resulted in more positive parent-reported family functioning because parents may actively respond to acculturation stress by investing in their parenting and family relationships.

Identifying ways to reduce acculturation stress and help parents cope with these stressors may be one way to promote higher self-esteem, and to reduce or prevent symptoms of depression and aggressive behavior among Latino youth. Parent acculturation stress was associated with worse adolescent-reported family functioning, which in turn, predicted lower symptoms of depression, lower aggressive behavior, and higher self-esteem in youth. These results reinforce and extend prior research on the harmful effects of acculturation stress on Latino youth well-being when youth themselves experience these stressors (Schwartz et al., 2015).

Parent-reported family functioning predicted lower youth alcohol use and cigarette smoking. Moreover, mediation analyses suggest that parent acculturation stress predicted cigarette and alcohol use by way of parent-reported family functioning. Thus, substance use preventive interventions may benefit from reducing sources of parent acculturation stress and/or helping parents cope with these stressors in ways that do not compromise their family lives.

Our findings suggest that youth-reported family functioning affects different youth outcomes than parent-reported family functioning. However, more research is needed to investigate the reasons for why youth-and parent-reported family functioning is differentially associated with youth mental health and substance use outcomes. This study relied on youth self-reports of mental health and substance use outcomes, and future research may benefit from also asking parents about their perceptions of their adolescent children’s mental health and substance use outcomes. Including measures of youth- and parent-reported youth outcomes may shed light into why youth-reported family functioning predicted youth depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and aggressive behavior while parent-reported family functioning predicted cigarette and alcohol use. Overall, our findings illustrate the need for gathering data from parents and adolescents to better understand how family functioning affects youth well-being (Larson & Richards, 1994).

Importantly, our findings indicate that preventive interventions to reduce adolescent health disparities need to target both parent acculturation stress and family functioning. Evidence-based and culturally tailored interventions that target family functioning to prevent health risk behaviors among Latino youth, such as Family Effectiveness Training (Szapocznik et al., 1989), Familias Unidas (Coatsworth, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2002), and culturally adapted Parent Management Training (Martinez & Eddy, 2005) exist, and they could benefit from including exercises to help Latino parents manage acculturation stressors more effectively.

In addition to parent-focused preventive interventions, structural-level strategies should be considered as well, because discrimination, a negative context of reception, and acculturative stress are embedded in a societal structure that immigrant Latino families cannot change (Yoshikawa et al., 2014). For example, many recent immigrant families do not qualify for or seek public support that could help them cope with acculturation stress because of immigration-related fears and mistrust of authorities, or because public support agencies do not have the experience, skills, and training to effectively assist Latino parents. Structural level efforts to reduce acculturation stress for parents could include strategies to promote positive views and acceptance of Latino families in community based settings such as work places, health care settings, schools, community settings, and government or state agencies (Yoshikawa et al., 2014). Additionally, professionals who work with immigrant Latino families could benefit from additional training so that these professionals do not inadvertently contribute to the acculturation stress experience of Latino parents (Yoshikawa et al., 2014). Latino parents may also benefit from assisted integration efforts that provide parents with language and literacy training, vocational training, and information about U.S. culture including their rights in the U.S., sources for public support, health insurance, the school system, as well as U.S. cultural norms and expectations (Valenta & Strabac, 2011; Yoshikawa et al., 2014).

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in light of a few limitations. First, results of the current study may not generalize to all Latino families in the United States. Data were collected in Miami and Los Angeles, which are relatively large and well-established Latino receiving communities with many ethnic enclaves that may buffer against negative context of reception and limit experiences of discrimination. Findings from this study may not reflect the experiences of Latino families who move into new settlement communities (e.g., the Midwest and Deep South) that have less experience interacting with newcomers (Barrington, Messias, & Weber, 2012) and where sources of support might not be available (Rodriguez, 2012).

Additionally, a majority of families in Miami were Cuban (61%), and the majority of families in Los Angeles were Mexican (70%). Much smaller numbers of other Latino groups were represented in this study. Our findings may not reflect the experiences of other Latino recent immigrant groups. Moreover, we did not assess documentation-related stress, and our findings may not fully capture the stress experiences of undocumented families (Cervantes, Fisher, Córdova, & Napper 2012). As such, future research on acculturation stressors, family functioning, and Latino youth mental health and substance use assess for documentation-related stress. Additionally, the majority of adolescents in the present study arrived in the U.S. at the same times as their primary caregiver and the majority of adolescents were born in the same country as their primary caregiver (Schwartz et al., 2014), and the results of this study may not generalize to adolescents and/or parents who come to the U.S. alone. Further, the current study focused on recent immigrant families whose experiences may differ from second or later generation Latino families. Moreover, almost 75% of the sample consisted of mothers whose experiences with and sources of acculturation stress may differ from those of fathers and other caregivers (Lorenzo-Blanco & Cortina, 2013). As such, our findings may not generalize to samples that largely consist of fathers and other caregivers or to samples that include an equal representation of a range of caregivers (fathers, mothers, grandparents or adoptive/foster parents). Thus, future research could benefit from investigating differences in experiences with and sources of acculturation stress with a range of caregivers.

This study contributes to the cultural and family stress literatures. It is one of the first to examine the effect of parent acculturation stress trajectories on youth-and parent-reported family functioning as well as youth mental health and substance use outcomes among recent immigrant Latino families. Consistent with the FSM, parent acculturation stress influenced family functioning to impact youth health and well-being. Clearly, our findings highlight the need for future preventive interventions to reduce health disparities among Latino by considering the influential roles of parent acculturation stress and family functioning.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by Grant DA025694 (National Institute of Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism).

Footnotes

We use the term “acculturation stress” to refer to a construct consisting of discrimination, acculturative stress, and a negative context of reception. Other labels have been used for this construct, including “cultural stress” (Cano et al., 2015; Schwartz et al., 2015) and “socio-cultural stress” (Lorenzo-Blanco et al., 2016).

All of the ideas reported in this article were presented at the 16th Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence.

Contributor Information

Elma I. Lorenzo-Blanco, University of South Carolina

Alan Meca, University of Miami.

Jennifer B. Unger, University of Southern California

Andrea Romero, University of Arizona.

Melinda Gonzales-Backen, Florida State University.

Brandy Piña-Watson, Texas Tech University.

Miguel A. Cano, Florida International University

Byron L. Zamboanga, Smith College

Sabrina E. Des Rosiers, Barry University

Daniel W. Soto, University of Southern California

Juan A. Villamar, Northwestern University

Karina M. Lizzi, University of Michigan

Monica Pattarroyo, University of Southern California.

Seth J. Schwartz, University of Miami

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA adult forms and profiles. Burlington: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, University of Vermont; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington C, Messias DKH, Weber L. Implications of racial and ethnic relations for health and well-being in new Latino communities: A case study of West Columbia, South Carolina. Latino Studies. 2012;10:155–178. doi: 10.1057/lst.2012.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein R. US Census Bureau projections show a slower growing, older, more diverse nation a half century from now. 2013 Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb12-243.html.

- Broudy R, Brondolo E, Coakley V, Brady N, Cassells A, Tobin JN, Sweeney M. Perceived ethnic discrimination in relation to daily moods and negative social interactions. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30:31–43. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cano MÁ, Schwartz SJ, Castillo LG, Romero AJ, Huang S, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Des Rosiers SE, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Lizzi KM, Soto DW, Oshri A, Villamar JA, Pattarroyo M, Szapocznik J. Depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors among Hispanic immigrant adolescents: examining longitudinal effects of cultural stress. Journal of Adolescence. 2015;42:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballo R, Kennedy TM, Bregman A, Epstein-Ngo Q. Always aware (Siempre pendiente): Latina mothers’ parenting in high-risk neighborhoods. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:805–815. doi: 10.1037/a00295584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States, 2014. MMWR. 2013;(SS 4):63. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Fisher DG, Córdova D, Jr, Napper LE. The Hispanic Stress Inventory—Adolescent Version: A culturally informed psychosocial assessment. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24:187. doi: 10.1037/a0025280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Song H, Stockdale GD, Ferrer E, Widaman KF, Cauce AM. Resilience and vulnerability of Mexican origin youth and their families: A test of a culturally informed model of family economic stress. In: Kerig PK, Schulz MS, Hauser ST, Kerig PK, Schulz MS, Hauser ST, editors. Adolescence and beyond: Family processes and development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 268–286. [Google Scholar]

- Fry R, Passel J. Latino children: A majority are US born-born offspring of immigrants. Washington, D.C: Pew Hispanic Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CL, Miller HV. A Final Report for the WEB Du Bois Fellowship Submitted to the National Institute of Justice. Washington: Department of Justice; 2010. Crime and victimization among Hispanic adolescents: A multilevel longitudinal study of acculturation and segmented assimilation. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:443–458. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(200007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Tolan PH, Zelli A, Huesmann LR. The relation of family functioning to violence among inner-city minority youths. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:115–129. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.10.2.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halim ML, Yoshikawa H, Amodio DM. Cross-generational effects of discrimination among immigrant mothers: Perceived discrimination predicts child’s healthcare visits for illness. Health Psychology. 2013;32:203–211. doi: 10.1037/a00227279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, O’Malley, Miech, Bachman, Schulenberg . Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014. Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kauermann G, Carroll RJ. A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:1387–1396. doi: 10.1198/016214501753382309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Richards MH. Divergent realities: The emotional lives of mothers, fathers, and adolescents. New, York: NY: Basic Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Leon AL. Immigration and stress: The relationship between parents’ acculturative stress and young children’s anxiety symptoms. Student Pulse. 2014;6 Retrieved from http:www.studentpulse.com/a?id=861. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Cortina LM. Latino/a depression and smoking: An analysis through the lenses of culture, gender, and ethnicity. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;51:332–346. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Romero AJ, Cano MÁ, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Cordova D, Oshri A, Santisteban DA, Des Rosiers SE, Huang S, Villamar JA, Soto D, Pattarroyo M. A process-oriented analysis of parent acculturation, parent socio-cultural stress, family processes, and Latina/o youth smoking and depressive symptoms. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2016;52:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Acculturation, gender, depression, and cigarette smoking among U.S. Hispanic youth: The mediating role of perceived discrimination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1519–1533. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9633-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D. Acculturation, enculturation, and symptoms of depression in Hispanic youth: The roles of gender, Hispanic cultural values, and family functioning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012;41:1350–1365. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9774-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Taylor Francis Group; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Using Mplus Monte Carlo simulations in practice: A note on non-normal missing data in latent variable models. 2002. Version 2, March 22, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegría M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Chapman MV, Stein GL. Becoming an American parent overcoming challenges and finding strength in a new immigrant Latino community. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1383–1414. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06290041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Madden T, Santos LJ. Psychological variables as predictors of perceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28:937–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01661.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez N. New Southern Neighbors: Latino immigration and prospects for intergroup relations between African-Americans and Latinos in the South. Latino Studies. 2012;10:18–40. doi: 10.1057/lst.2012.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Myers HF, Mira CB, Flores T, Garcia-Hernandez L. Development of the multidimensional acculturative stress inventory for adults of Mexican origin. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:451–461. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.14.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento IA, Cardemil EV. Family functioning and depression in low-income Latino couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2009;35:432–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.200901139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt DP, Allik J. Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:623–642. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, Villamar JA, Soto DW, Pattarroyo M, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Szapocznik J. Perceived context of reception among recent Hispanic immigrants: Conceptualization, instrument development, and preliminary validation. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;20:1–14. doi: 10.1037/a0033391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Zamboanga BL, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Des Rosiers SE, Romero AJ, Cano MA, Gonzales-Backen MA, Córdova D, Piña-Watson BM, Huang S, Villamar JA, Soto DW, Pattarroyo M, Szapocznik J. Trajectories of cultural stressors and effects on mental health and substance use among Hispanic immigrant adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;56:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorova IL, Falcón LM, Lincoln AK, Price LL. Perceived discrimination, psychological distress and health. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2010;32:843–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Huesmann LR, Zelli A. Assessment of family relationship characteristics: a measure to explain risk for antisocial behavior and depression among urban youth. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:212–223. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.212. [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Driscoll MW, Voell M. Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: a moderated mediational model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18:17–25. doi: 10.1037/a0026710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trail TE, Goff PA, Bradbury TN, Karney BR. The costs of racism for marriage how racial discrimination hurts, and ethnic identity protects, newlywed marriages among Latinos. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2012;38:454–465. doi: 10.1177/0146167211429450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran AG. Family contexts: Parental experiences of discrimination and child mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;53:37–46. doi: 10.1007/s1046-013-9607-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LB, Pleck JH, Sonsenstein LH. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic Heritage Month 2014. Facts for Features. 2014 (CB14-FF.22). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2014/cb14-ff22.html.

- Valenta M, Bunar N. State-assisted integration, but not for all: Norwegian welfare services and labour migration from the new EU member states. Internatnional Social Work. 2011;54:663–680. doi: 10.1177/0020872810392811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa H, Perreira KM, Weiland Ch, Crosnoe R, Ulvestad K, Chaudry A, Fortuny K, Pedroza JM. Improving access of low-income immigrant families to health and human services: The role of community-based organizations. The Urban Institute; 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.urban.org/research/publication/improving-access-low-income-immigrant-families-health-and-human-services. [Google Scholar]

- Widaman KF, Thompson JS. On specifying the null model for incremental fit indices in structural equation modeling. Psychological Methods. 2003;8:16–37. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.8.1.16. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.8.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]