Abstract

In this study, we demonstrate that the prototype B. breve strain UCC2003 possesses specific metabolic pathways for the utilisation of lacto-N-tetraose (LNT) and lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT), which represent the central moieties of Type I and Type II human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), respectively. Using a combination of experimental approaches, the enzymatic machinery involved in the metabolism of LNT and LNnT was identified and characterised. Homologs of the key genetic loci involved in the utilisation of these HMO substrates were identified in B. breve, B. bifidum, B. longum subsp. infantis and B. longum subsp. longum using bioinformatic analyses, and were shown to be variably present among other members of the Bifidobacterium genus, with a distinct pattern of conservation among human-associated bifidobacterial species.

Consumption of maternal breast milk, or the lack thereof, influences the gut microbiota composition of the neonate1,2,3. Incorrect development or disruption of this microbial community contributes to disorders such as Necrotising Enterocolitis, infantile diarrhoea and Group B streptococcal neonatal infection4,5,6,7,8. Strikingly, the faecal microbiota of healthy breastfed infants is enriched for certain species of the Bifidobacterium genus9, which are high-G+C Gram-positive anaerobes and members of the Actinobacteria phylum. Naturally found as symbionts of the mammalian, avian or insect digestive tract, bifidobacteria enjoy substantial scientific attention due to their purported beneficial properties2,10,11,12,13,14,15,16.

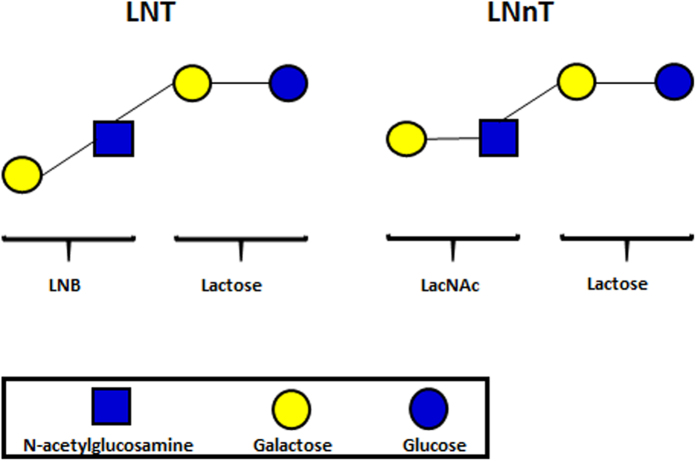

While lactose (Galβ1-4Glc) comprises the main carbohydrate component of human breast milk and colostrum (~90%), human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) constitute the next most significant carbohydrate fraction, ahead of glycolipids2,17, and are typically found at a concentration of ≥4 g/L (and as high as 15 g/L)2,18,19,20. HMOs represent a heterogeneous glycan mix, of which >200 distinct structures have been identified18. The majority of these HMO structures are classified into 2 types. The abundant Type I HMOs contain lacto-N-tetraose (LNT; Fig. 1) (Galβ1-3GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc), which is composed of a lactose coupled to lacto-N-biose (LNB) (Galβ1-3GlcNAc). Type II HMOs contain the LNT isomer lacto-N-neotetraose (LNnT; Fig. 1) (Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4Glc), which is composed of lactose linked to N-acetyllactosamine (LacNAc) (Galβ1-4GlcNAc), an isomer of LNB. Larger Type I and II HMOs may contain further LNB or LacNAc subunits, and can be fucosylated or sialylated2,18,21.

Figure 1. Schematic structures of Type I HMO moiety LNT, and Type II HMO moiety LNnT.

Despite the abundance of HMOs in breast milk, these glycans cannot be metabolised by the infant, and it is currently believed that they facilitate the establishment of an infant-specific gut microbiota, with bifidobacteria being particularly abundant16,22. Common among the latter are Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis and subsp. longum, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum and Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense9,23,24,25,26,27. Unsurprisingly, it has been shown that certain bifidobacterial species can metabolize (particular) HMOs18,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Previous studies have elucidated some of the metabolic pathways for HMO utilisation by B. bifidum and B. longum subsp. infantis, with particular focus on LNT and LNnT28. B. longum subsp. infantis internalises particular, intact small-mass HMOs, including (precursors of) LN(n)T18,28,35, which are in turn hydrolysed into lacto-N-triose and galactose, by two HMO type-specific β-galactosidases (i.e. one enzyme acting on LNT, the other on LNnT)29. Lacto-N-triose is further hydrolysed by an N-acetylhexosaminidase into N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) and lactose, the latter of which is then hydrolysed by a β-galactosidase30 into galactose and glucose, to enter the Leloir and fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) phosphoketolase pathways and amino-sugar metabolising pathway (for GlcNAc)28,31, all of which feed into the overall Bifidobacteriaceae-specific metabolic pathway known as the Bifid Shunt.

B. bifidum possesses two distinct, and apparently unique pathways for the metabolism of LN(n)T. Large type I and II HMOs are degraded by extracellular fucosidases, sialidases and glycoside hydrolases to release LNT and LNnT28. LNT is hydrolysed at its central β-1,3-link by an extracellular glycoside hydrolase into lactose and LNB, the latter being transported into the cell and then degraded by two distinct LNB phosphorylases (LNBP), releasing galactose 1-phosphate and GlcNAc32,33. The released lactose is either hydrolysed by an extracellular β-galactosidase into galactose and glucose (which are both internalized by the cell), or transported into the cell, where it is similarly hydrolysed by intracellular β-galactosidases28,32,36. These monosaccharides are then further metabolised by the same pathways as those described for B. longum subsp. infantis. This type I HMO metabolism has also been observed in some species of B. longum subsp. longum32,37. In addition, B. bifidum possesses a separate pathway to degrade and utilise LNnT. An extracellular β-galactosidase cleaves LNnT at its Galβ-1,4 residue, liberating galactose and lacto-N-triose34. The lacto-N-triose is then further hydrolysed by an extracellular N-acetylhexosaminidase, releasing GlcNAc and lactose, with the latter further hydrolysed by the aforementioned extracellular β-galactosidases into glucose and galactose (which are transported into the cell)36, or internalised and then degraded as described. Once within the cell, these monosaccharides are metabolised as mentioned above34.

It should be noted that a specific pathway exists for LNB metabolism, known as the GNB/LNB pathway. In B. bifidum, as mentioned above, LNB is phosphorolysed into monosaccharides by either of two different LNBP enzymes, while in B. infantis, LNB is phosphorolysed by a single LNBP enzyme, whose gene shares homology with both B. bifidum LNBP genes28,31. This GNB/LNB pathway appears to be present in bifidobacterial species commonly found in infant faeces28. The apparent absence of this GNB/LNB pathway and, specifically, the LNBP-encoding gene in adult-associated bifidobacteria (such as B. adolescentis) is manifested through their inability to utilise LNB or other HMOs as a carbon source for growth, and may therefore explain, at least in part, their absence or low abundance in the microbiota of breast-fed infants18.

Little information exists regarding HMO utilisation by B. breve, although it has been suggested that B. breve acts as a ‘scavenger’ through cross-feeding on HMO-derived monosaccharides that are released due to the extracellular hydrolytic activities produced by other infant gut microbiota members18. However, more recent studies have suggested that B. breve is able to utilise particular HMOs, such as fucosyllactose, LNT and sialyl-LNT, or derived structures such as LNB and sialic acid17,38,39,40.

In this study, we show that B. breve possesses the metabolic machinery for the degradation and utilisation of LNT and LNnT. Furthermore, we assess the presence and distribution of key gene loci involved in LNT and LNnT utilisation across members of the Bifidobacterium genus.

Results

Growth of B. breve strains on LNT and LNnT

In order to determine if B. breve strains are capable of LNT and/or LNnT metabolism, growth in modified MRS medium (mMRS) supplemented with either 1% (wt/vol) LNT, LNnT or lactose (as a positive control) was assessed for sixteen B. breve strains by measuring the OD600nm following 24 hours of anaerobic growth at 37 °C. All tested B. breve strains were generally observed to grow well (final OD600nm > 0.8) on both LNT and LNnT, with some variability between strains on one or both HMO substrates (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Transcriptome analysis of B. breve UCC2003 grown on LNT and LNB

In order to identify genes that are involved in the metabolism of the Type I HMO central moiety LNT and its constituent component LNB, global gene expression was determined by microarray analysis during growth of B. breve UCC2003 in mMRS supplemented with LNT or LNB, and compared to the transcriptome of the strain when grown in mMRS supplemented with ribose. Ribose was selected as a suitable transcriptomic reference, as the metabolic pathway and gene expression profile for growth of UCC2003 on ribose is known and has been employed previously as a reference39,41. Genes that were shown to be significantly upregulated in transcription above the designated cut-off (fold-change >2.5, P < 0.001) are shown in Table 1. The genes upregulated in expression included those corresponding to the loci Bbr_0526-530, Bbr_1551-1553, Bbr_1554-1560 and Bbr_1585-1590. The possible involvement of these genes in LNT/LNB metabolism will be further discussed below.

Table 1. B. breve UCC2003 genes upregulated in expression during growth in mMRS medium supplemented with 1% LNT, LNnT, LNB, lactosamine-HCl, or lactose as the sole carbohydrate.

| Gene ID | Gene name | Function | Fold upregulationa,b during growth on: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNT | LNnT | LNB | Lactosamine-HCl | Lactose | |||

| Bbr_0417 | galC | Solute-binding protein of ABC transporter system for sugars | — | — | — | 10.93 | — |

| Bbr_0418 | galD | Permease protein of ABC transporter system for sugars | 3.23 | 5.18 | — | 6.98 | — |

| Bbr_0419 | galE | Permease protein of ABC transporter system for sugars | 3.10 | 7.88 | 3.18 | 9.80 | 3.07 |

| Bbr_0420 | galG | GH42 lacZ4 Beta-galactosidase | — | — | — | 3.85 | — |

| Bbr_0421 | galR | Transcriptional regulator, LacI family | — | — | — | — | — |

| Bbr_0422 | galA | GH53 galA Endogalactanase | — | — | — | 4.07 | — |

| Bbr_0490 | Bbr_0490 | Transcriptional regulator, DeoR family | — | 3.27 | — | 2.60 | — |

| Bbr_0491 | galT | Galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | — | — | 5.08 | — | — |

| Bbr_0492 | galK | Galactokinase | — | — | 3.57 | — | — |

| Bbr_0526 | lntR | Transcriptional regulator, LacI family | — | 3.95 | — | 10.16 | — |

| Bbr_0527 | lntP1 | Permease protein of ABC transporter system for sugars | 6.81 | 10.05 | — | 8.57 | 3.48 |

| Bbr_0528 | lntP2 | Permease protein of ABC transporter system for sugars | 3.23 | 10.64 | 3.03 | 11.15 | 3.35 |

| Bbr_0529 | lntA | GH42 Beta-galactosidase | 6.61 | 12.58 | — | 9.53 | 3.64 |

| Bbr_0530 | lntS | Solute-binding protein of ABC transporter system for sugars | 4.15 | 5.20 | 2.97 | 17.17 | 3.31 |

| Bbr_0845 | glgP2 | glgP2 Glycogen phosphorylase | — | — | — | 2.73 | — |

| Bbr_0846 | nagA1 | nagA1 N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase | — | — | — | 4.76 | — |

| Bbr_0847 | nagB2 | nagB2 Glucosamine-6-phosphate isomerase | — | — | — | 5.82 | — |

| Bbr_0848 | Bbr_0848 | Sugar kinase, ROK family | 3.30 | 5.12 | — | 10.69 | — |

| Bbr_0849 | Bbr_0849 | NagC/XylR-type transciptional regulator | — | 2.90 | — | 14.40 | — |

| Bbr_0850 | Bbr_0850 | Aldose 1-epimerase family protein | — | — | — | 7.39 | — |

| Bbr_0851 | Bbr_0851 | Glucose/fructose transport protein | 2.91 | 3.75 | — | 16.43 | — |

| Bbr_0852 | atsA2 | Sulfatase family protein | — | — | — | 4.18 | — |

| Bbr_0853 | atsB2 | atsB Arylsulfatase regulator (Fe-S oxidoreductase) | — | — | — | 2.70 | — |

| Bbr_0854 | Bbr_0854 | Conserved hypothetical membrane spanning protein with DUF81 domain | — | — | — | 4.03 | — |

| Bbr_0855 | Bbr_0855 | Hypothetical protein | — | — | — | 7.31 | — |

| Bbr_0856 | Bbr_0856 | Conserved hypothetical membrane spanning protein | — | — | — | 3.82 | — |

| Bbr_1247 | nagA2 | CE9 nagA2 N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase | 2.67 | 5.06 | 3.92 | — | — |

| Bbr_1248 | nagB3 | nagB3 Glucosamine-6-phosphate isomerase | 4.11 | 5.95 | 8.51 | — | — |

| Bbr_1249 | Bbr_1249 | Transcriptional regulator, ROK family | — | — | — | 3.84 | — |

| Bbr_1250 | Bbr_1250 | Sugar kinase, ROK family | 2.44 | 7.70 | — | 8.75 | — |

| Bbr_1251 | Bbr_1251 | N-acetylglucosamine repressor | — | — | — | 7.71 | — |

| Bbr_1252 | pfkB | Fructokinase | — | — | — | — | — |

| Bbr_1550 | Bbr_1550 | Hypothetical protein | — | 2.90 | — | 28.72 | 2.81 |

| Bbr_1551 | lacS | Galactoside symporter | 13.10 | 73.82 | — | 43.73 | 31.62 |

| Bbr_1552 | LacZ6 | GH2 Beta-galactosidase | 44.01 | 105.71 | — | 39.65 | 11.01 |

| Bbr_1553 | lacI | Transcriptional regulator, LacI family | — | 4.56 | — | 15.60 | — |

| Bbr_1554 | nahS | Solute-binding protein of ABC transporter system (lactose) | 5.71 | 15.05 | 9.91 | 13.10 | — |

| Bbr_1555 | nahR | NagC/XylR-type transciptional regulator | 4.86 | 12.53 | — | 21.74 | — |

| Bbr_1556 | nahA | GH20 nagZ Beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase | 2.65 | 3.74 | — | 2.90 | — |

| Bbr_1558 | nahP | Permease protein of ABC transporter system | — | — | 4.97 | — | — |

| Bbr_1559 | nahT1 | ATP-binding protein of ABC transporter system | — | — | — | 2.66 | — |

| Bbr_1560 | nahT2 | ATP-binding protein of ABC transporter system | — | — | 3.42 | 2.51 | — |

| Bbr_1585 | galE | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | — | 3.11 | 3.33 | 4.12 | — |

| Bbr_1586 | nahK | Phosphotransferase family protein | 4.55 | 10.69 | 3.19 | — | — |

| Bbr_1587 | lnbP | GH112 lacto-N-biose phorylase | — | 3.86 | 6.52 | — | — |

| Bbr_1588 | galP1 | Permease protein of ABC transporter system for sugars | 3.38 | 4.20 | 6.38 | — | — |

| Bbr_1589 | galP2 | Permease protein of ABC transporter system for sugars | 2.78 | 5.47 | 4.05 | — | — |

| Bbr_1590 | galS | Solute-binding protein of ABC transporter system for sugars | 4.41 | 4.45 | 16.49 | — | — |

The level of expression is shown as a fold-value of increase in expression on each carbohydrate, as compared to a ribose control, with a cut-off of a minimum 2.5-fold increase in expression. Genes within the 4 loci focused on in this study are shown in bold script.

aBased on comparative transcriptome analysis using B. breve UCC2003 grown on 1% LNT, LNnT, LNB, lactosamine-HCl or lactose compared to growth on ribose. Microarray data were obtained using B. breve UCC2003 grown on 1% LNT, LNnT, LNB, lactosamine-HCl or lactose and were compared with array data obtained when B. breve UCC2003 was grown on ribose as a control.

bThe cutoff point is 2.5-fold, with a P value of _0.001. —, value below the cutoff.

Genetic organisation of the genes involved in metabolism of LNT

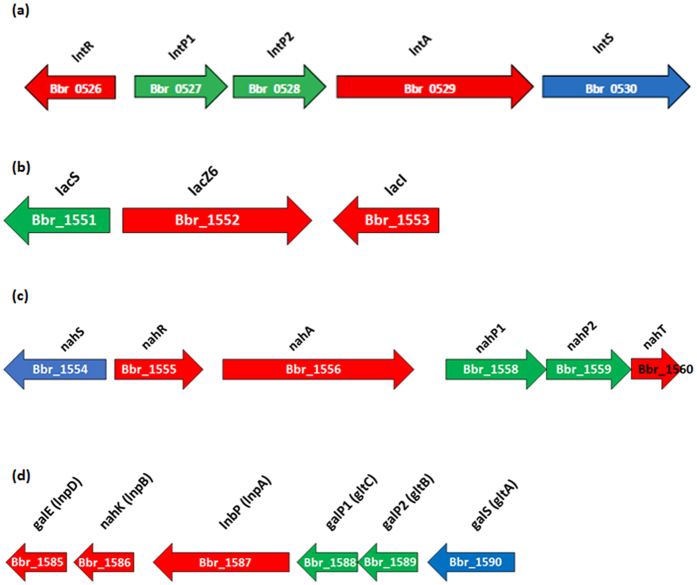

Based on the microarray results and functional prediction of these LNT (and LNB)-upregulated genes, we implicate the gene clusters Bbr_0526-0530, Bbr_1554-1560, Bbr_1585-1590 and possibly Bbr_1551-1553 (outlined in Fig. 2) in LNT and LNB metabolism in B. breve UCC2003.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the gene loci involved in the utilisation of LNT, LNnT and their substituents in B. breve UCC2003, as based on transcriptome analysis.

The length of the arrows is proportional to the size of the open reading frame and the gene locus name, which is indicative of its putative function, is given at the top. Genes shown in red are predicted to encode proteins with an intracellular localisation, genes shown in green are predicted to encode proteins with a transmembrane localisation, and genes shown in blue are predicted to encode proteins with an extracellular localisation and a signal peptide sequence.

Bbr_0527 and Bbr_0528 (designated here as lntP1 and lntP2, respectively) are both predicted to encode permease components of an ABC transporter system. Also located in this cluster (Fig. 2) is Bbr_0529 (designated lntA), which encodes a predicted β-galactosidase of the GH42 glycoside hydrolase family. Bbr_0530 (designated here as lntS) encodes a putative solute-binding protein of an ABC transporter system. Located immediately upstream of this cluster, Bbr_0526 (designated lntR) encodes a putative LacI-type transcriptional regulator. We have previously implicated the Bbr_0526-530 gene cluster, in the metabolism of galacto-oligosaccharides42, where the genes were designated gosR (lntR), gosD (lntP1), gosE (lntP2), gosG (lntA) and gosC (lntS). Here, we chose to re-designate this cluster as the lnt cluster, as its primary function appears to be in LNT and LNnT metabolism (see below).

Bbr_1551 (designated here as lacS) encodes a galactoside symporter, and is predicted to function in the transport of lactose and galacto-oligosaccharides into the cell. The lacS gene is located in a cluster that also contains genes Bbr_1552 (designated lacZ6), a β-galactosidase (GH2) previously shown to be involved in galacto-oligosaccharide metabolism42, and Bbr_1553 (designated lacI), a lacI-type regulator.

Bbr_1555 (designated nahR) is predicted to encode a Nag-type transcriptional regulator. Bbr_1556 (designated nahA) encodes a putative β-N-acetylhexosaminidase (GH20). Upstream of nahR is a gene encoding a putative solute binding protein (Bbr_1554 and designated here as nahS), while located downstream of nahA are Bbr_1558 (nahP1), Bbr_1559 (nahP2) and Bbr_1560 (nahT), which are predicted to specify two permeases and an ATP-binding protein; respectively (Fig. 2).

Bbr_1587 (designated here as lnbP) encodes a clear homolog (89.84% similarity to BBPR_1055 of B. bifidum PRL2010, and 97.62% to Blon_2174 of B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697) of the previously characterised LNBP, which belongs to the 1,3-β-Galactosyl-N-acetylhexosamine phosphorylase family (GH112)31,43,44. The presumed function of this protein in UCC2003 is the cleavage and concomitant phosphorylation of LNB, and its passage into the GNB/LNB pathway43,44,45,46,47. The lnbP gene is located in the cluster Bbr_1585-1590, which also includes genes encoding a UDP-glucose 4-epimerase (Bbr_1585; galE), a phosphotransferase family protein (Bbr_1586; nahK), two permease proteins (Bbr_1588 and Bbr_1589; galP1 and galP2, respectively), and a solute-binding protein (Bbr_1590; galS) (Fig. 2), which are all predicted to function in the metabolism of GNB/LNB.

Heterologous expression, purification and biochemical characterisation of LntA and NahA, and enzymatic activity on LNT

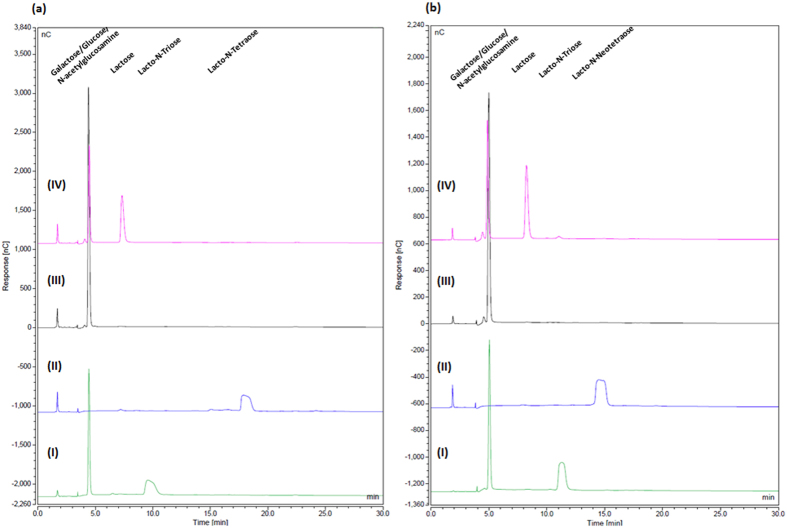

In order to investigate the predicted enzymatic activities encoded by lntA (Bbr_0529) and nahA (Bbr_1556) on core Type I HMO structure LNT, the corresponding LntA and NahA proteins were purified as His-tagged versions (LntAHis and NahAHis; see Materials and Methods). Biochemical and substrate specificity characterisations were performed by incubating LntAHis and NahAHis on their own or in combination with LNT, and analysing the reaction products by HPAEC-PAD. Purified LntAHis was shown to remove the galactose moiety at the non-reducing end of the substrate LNT (Fig. 3a), demonstrating hydrolytic activity towards Galβ-1,3GlcNAc in Type I HMO structures, and indicating a key role in the hydrolysis and utilisation of LNT.

Figure 3.

HPAEC chromatogram profiles of (a) LNT and (b) LNnT, when incubated in MOPS buffer (pH7) with: (I) LntA alone, (II) NahA alone, (III) LntA and NahA together, and (IV) LntA, followed by a denaturation step and the subsequent addition of NahA.

When NahAHis was incubated alone with LNT, no degradation of the tetrasaccharide structure was observed (Fig. 3a). However, when LntAHis, and NahAHis were together incubated with LNT, complete breakdown of LNT to the monosaccharide constituents was observed. When LNT was incubated first with LntAHis, followed by an enzymatic heat denaturation step, and then incubated with NahAHis, different reaction product profiles were observed. Samples taken following the initial denaturation prior to the addition of NahAHis showed the presence of lacto-N-triose and galactose. Samples then taken following subsequent incubation with NahAHis indicated the presence of galactose, GlcNAc and lactose.

These results show that LntA hydrolyses LNT, releasing galactose and lacto-N-triose. Lacto-N-triose is then hydrolysed by NahA, liberating Lactose and GlcNAc. The lactose is then further broken down by LntA (and probably other β-Galactosidases in vivo), releasing galactose and glucose.

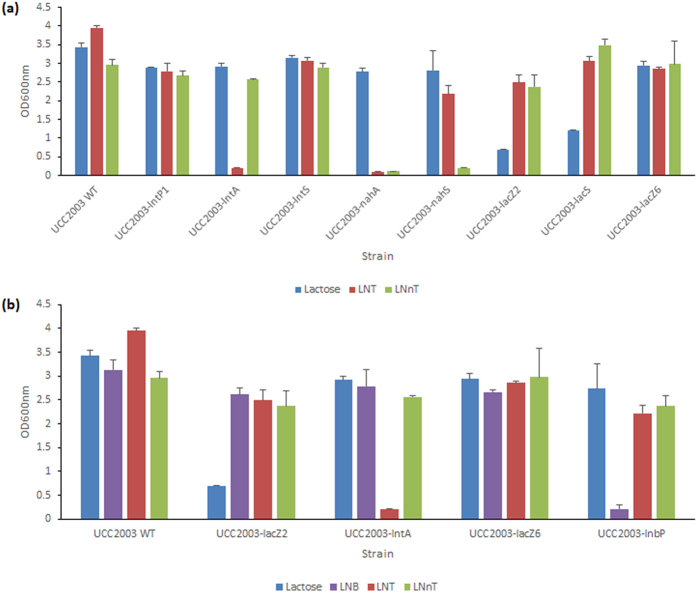

Phenotypic analysis of B. breve strains harbouring mutations of genes implicated in LNT metabolism

In order to investigate if disruption of individual genes of the lnt cluster affect the ability of UCC2003 to utilise LNT, a number of insertion mutants, which either had been generated previously, or which were constructed here, were assessed. An insertion mutant was constructed in lntS, resulting in strain B. breve UCC2003-lntS. Insertion mutants in lntP1 and lntA, generating strains B. breve UCC2003-lntP1 and B. breve UCC2003-lntA, respectively, had been generated in a previous study (then designated B. breve UCC2003-gosD and B. breve UCC2003-gosG, respectively)42. These strains were analysed for their ability to grow in mMRS supplemented with LNT or LNB, with lactose controls, as compared to B. breve UCC2003. A complete lack of growth was observed for B. breve UCC2003-lntA in media containing LNT, in contrast to normal growth by the wild type in the same media (Fig. 4a). Growth of this mutant strain was not impaired in media containing LNB (not shown). As expected, reintroduction of the lntA gene on plasmid pBC1.2 under the control of the constitutive p44 promoter48 (see Materials and Methods) in the UCC2003-lntA mutant restored the mutant’s ability to grow on LNT (Supplemental Fig. S3). Thus, transcriptome data, substrate hydrolysis profiles and mutant growth results demonstrate that this β-galactosidase is specifically required for the hydrolysis of the Type I HMO central moiety LNT at its Galβ1-3GlcNAc residue, liberating galactose and lacto-N-triose for further metabolic processing. Insertion mutants B. breve UCC2003-lntP1 and B. breve UCC2003-lntS were shown to reach the same final optical density as wild type strain UCC2003 during growth in mMRS supplemented with LNT(Fig. 4a), indicating that either these predicted transport components do not play a role in LNT metabolism, or that there are compensatory transport systems for this substrate.

Figure 4.

(a) Final OD600nm values after 24 hours of growth of wild type B. breve UCC2003 and mutants B. breve UCC2003-lntP1, B. breve UCC2003-lntA, B. breve UCC2003-lntS, B. breve UCC2003-nahA, B. breve UCC2003-nahS, B. breve UCC2003-lacZ2, B. breve UCC2003-lacS and B. breve UCC2003-lacZ6 in modified MRS containing 1% (wt/vol) lactose, 1% (wt/vol) LNT or 1% (wt/vol) LNnT as the sole carbon source. (b) Final OD600nm values after 24 hours of growth of wild type B. breve UCC2003, and mutants B. breve UCC2003-lacZ2, B. breve UCC2003-lntA, B. breve UCC2003-lacZ6, and B. breve UCC2003-lnbP in modified MRS containing 1% (wt/vol) lactose, 1% LNB, 1% (wt/vol) LNT, 1% (wt/vol) LNnT as the sole carbon source. The results are the mean values obtained manually from two separate experiments (due to the limited availability of certain carbohydrates). Error bars represent the standard deviation.

In order to investigate if disruption of lnbP affects the ability of UCC2003 to utilise LNT and/or LNB, a Tn5 transposon insertion mutant of lnbP (designated B. breve UCC2003-lnbP) was adopted from a previous study46 and compared to wild type B. breve UCC2003 for its ability to grow in mMRS broth supplemented with LNT or LNB, or lactose as control. As expected, and in contrast to the wild type control, B. breve UCC2003-lnbP displayed a near total inability to grow on LNB (Fig. 4b). This mutant reached final OD600nm levels on LNT and lactose that are comparable to the wild type strain (Fig. 4b), confirming the crucial role of lnbP in LNB metabolism, while it also shows that lntA plays no direct in vivo role in LNB metabolism.

In order to investigate if disruption of lacS, nahS or nahA affects the ability of UCC2003 to utilise LNT, insertion mutants in these genes were assessed. The insertional mutant B. breve UCC2003-lacS42 did not show any significant difference in the final OD reached following growth on LNT as compared with the wild type (Fig. 4a). The insertional mutant in nahS (generated in this study), designated B. breve UCC2003-nahS, also did not exhibit a difference in final OD following growth in media containing LNT (as compared to the wild type, (Fig. 4a). This suggests that either nahS is not involved in LNT transport, or that while nahS and the other transport system components of the nah locus may be involved in the transport of LNT into the cell, their function is compensated by the activity of one or more other transport systems. The insertion mutant in nahA (generated in this study), designated B. breve UCC2003-nahA, was shown to exhibit a complete lack of growth in LNT-containing media (Fig. 4a). Reintroduction of the nahA gene in trans on plasmid pBC1.2, under the transcriptional control of its own promoter48 (see Materials and Methods), in the UCC2003-nahA mutant restored the ability to grow on LNT (Supplemental Fig. S3). These findings demonstrate that nahA is crucial for LNT metabolism, being responsible for the hydrolysis of lacto-N-triose, thereby liberating lactose and GlcNAc.

Transcriptome analysis of B. breve UCC2003 grown on LNnT, lactosamine and lactose

In order to investigate which genes are involved in the metabolism of Type II central moiety LNnT and its constituent component LacNAc, global gene expression was determined by microarray analysis during growth of B. breve UCC2003 in mMRS supplemented with each respective sugar, as well as lactose (which also possesses a Galβ-1,4 residue) as compared with gene expression during growth in mMRS supplemented with ribose (NB. We used a hydrochloride salt of lactosamine instead of LacNAc, as the latter was not commercially available in an affordable quantity). Genes that were shown to be significantly upregulated in transcription above the designated cut-off (fold-change >2.5, P < 0.001) are shown in Table 1. The genes upregulated in expression included those located in the loci Bbr_0526-530, Bbr_1551-1553, Bbr_1554-1560 and Bbr_1585-1590. Possible involvement of these genes in LNnT/LacNAc metabolism are assessed below.

Genetic organisation of the genes involved in metabolism of LNnT

Based on the results of the microarray analyses performed and functional annotation of LNnT/LacNAc-upregulated genes, we propose that the products of the gene clusters Bbr_0526-0530, Bbr_1551-1553 and Bbr_1554-1560 (schematically outlined in Fig. 2) are involved in the metabolism of LNnT and LacNAc (present as central moieties in Type II HMO) in B. breve UCC2003.

Heterologous expression, purification and biochemical characterisation of LntA, LacZ2, LacZ6, NahA, and enzymatic activity on Type II HMO structure LNnT

In order to investigate the predicted individual and combined enzymatic activities of the protein products lacZ2 (Bbr_0010), lntA (Bbr_0529), lacZ6 (Bbr_1552) and nahA (Bbr_1556) on core Type II HMO structure LNnT, the corresponding His-tagged protein products were overproduced and purified. Biochemical and substrate specificity characterisations were performed by incubating individual enzymes or combinations thereof with a particular substrate, and analysing the reaction products by HPAEC against a number of substrate standards and reaction controls. Purified LntAHis was capable of removing the galactose moiety at the non-reducing end of LNnT (Fig. 3b), as well as lactose (data not shown), demonstrating a triple specificity for Galβ-1,3GlcNAc, Galβ-1,4GlcNAc and Galβ-1,4Glc glycosidic linkages, and thus both Type I and Type II HMO central moieties and lactose. Purified LacZ2His and LacZ6His were, under the conditions applied, also capable of hydrolysing LNnT and lactose (data not shown).

When both LntAHis and NahAHis were incubated with LNnT, complete hydrolysis of LNnT to its constituent monosaccharides was observed. When LNnT was incubated first with LntAHis, followed by an enzymatic heat denaturation step, and then incubated with NahAHis, different reaction product profiles were observed. Samples taken following the initial denaturation prior to the addition of NahAHis showed the presence of lacto-N-triose and galactose. Samples taken following the addition of NahAHis and subsequent incubation showed the presence of galactose, GlcNAc and lactose (Fig. 3b).

Similar results from separate and combined reactions were obtained using LacZ2His or LacZ6His, together with NahAHis on the substrate LNnT (Supplemental Fig. S2).

These results agree with the model for Type II HMO metabolism proposed here; where LntA, LacZ2 and/or LacZ6 (and perhaps other β-galactosidases) hydrolyse LNnT, releasing galactose and lacto-N-triose, unlike LNT, which neither purified LacZ2 nor LacZ6 displayed the ability to hydrolyse (data not shown). Lacto-N-triose is then hydrolysed by NahA, liberating lactose and GlcNAc. Lactose is then further broken down by LntA (and other β-Galactosidases, including LacZ2 and LacZ6, in vivo), releasing galactose and glucose. Therefore, these two β-Galactosidases may carry out hydrolysis of Type II HMO central moieties (in conjunction with LntA).

Phenotypic analysis of B. breve strains harbouring mutations of genes implicated in LNnT metabolism

In order to investigate if disruption of individual genes of the lnt cluster affects the ability of UCC2003 to utilise LNnT, a number of insertion mutants were assessed. B. breve UCC2003-lntP1, B. breve UCC2003-lntS and B. breve UCC2003-lntA were analysed for their ability to grow in mMRS supplemented with LNnT with lactose controls, as compared to wild type B. breve UCC2003. B. breve UCC2003-lntA reached the same final optical density following growth in media containing LNnT compared to wild type UCC2003 (Fig. 4a). Transcriptome data and carbohydrate hydrolysis assays (see above) demonstrated that lntA is involved in LNnT metabolism, but its function can also be carried out by other glycoside hydrolases, as mentioned. The insertion mutants B. breve UCC2003-lntP1 and B. breve UCC2003-lntS did not show any significant impairment in growth on either LNnT or lactose, as compared with the wild type (Fig. 4a), indicating that either these predicted transport components do not play a role in LN(n)T metabolism or that there are additional transport systems that allow internalisation LNnT. It is most likely that lntP1, lntP2 and lntS do indeed also function in the transport of extracellular LNnT into the cytoplasm, but that their function can be supplemented or indeed supplanted by other cellular transport systems. The lnbP insertion mutant, B. breve UCC2003-lnbP, was shown to reach final OD600nm levels on either lactose or LNnT that were comparable to those of the wild type strain (Fig. 4b), suggesting lnbP plays no direct role in LNnT utilisation.

In order to investigate if disruption of each of the five individual genes lacZ2, lacZ6, lacS, nahS and nahA affects the ability of UCC2003 to utilise LNnT, mutants of these genes were assessed. The nahS and nahA insertion mutants mentioned above were used for this purpose, in addition to insertion mutants in the genes Bbr_1551 (lacS), Bbr_1552 (lacZ6), constructed in a previous study42, as well as a Tn5 transposon mutant in Bbr_0010 (lacZ2), from a separate study49. These mutant strains were analysed for their ability to grow in mMRS supplemented with LNnT with a lactose (and ribose, in the case of B. breve UCC2003-lacZ2 and B. breve UCC2003-lacS) control, as compared to B. breve UCC2003. The insertion mutants B. breve UCC2003-lacZ2 and B. breve UCC2003-lacZ6 did not show any significant impairment in growth on LNnT, as compared to the wild type, as neither did the insertional mutant B. breve UCC2003-lacS (Fig. 4a). While these growth analyses indicate that lacZ2 and lacZ6 are not essential for LNnT metabolism, the hydrolysis assay results and LNnT-dependent transcriptional induction of lacZ6 (described above) suggest that these two glycoside hydrolases play a role in LNnT hydrolysis, presumably in concert with lntA. The insertion mutant B. breve UCC2003-nahS was shown to exhibit a near total lack of growth in media supplemented with LNnT, as compared to the wild type grown in the same media (Fig. 4a). As expected, reintroduction of the nahS gene on plasmid pBC1.2, under the regulation of its own promoter48 (see Materials and Methods), in the UCC2003-nahS mutant reverted the mutant’s (near complete) inability to grow on LNnT (Supplemental Fig. S3). This indicates that nahS encodes the solute binding protein predominantly required for the uptake of LNnT, and that the nah locus-encoded transport system is of critical importance for the transport of the Type II central tetrasaccharide into the cell. In contrast to the wild type, B. breve UCC2003-nahA failed to grow in media containing LNnT (Fig. 4a). As expected, reintroduction of the nahA gene on plasmid pBC1.2, under the regulation of its own promoter48 (see Materials and Methods), in the UCC2003-nahA mutant reverted the mutant’s inability to grow on LNnT (Supplemental Fig. S3). This result demonstrates the essential role of the nahA product in LNnT metabolism, by hydrolysing lacto-N-triose at its GalNacβ1-3Gal linkage, liberating lactose and GlcNAc.

Growth of the insertion mutants was not impaired on lactose, where all strains reached final OD600nm levels comparable to that reached by UCC2003, except for B. breve UCC2003-lacZ2 and B. breve UCC2003-lacS, as the interrupted genes in these mutants are known to be crucial for lactose metabolism42,49 (Fig. 4a). B. breve UCC2003-lacZ2 and B. breve UCC2003-lacS did reach final OD600nm values similar to that of UCC2003 when grown on ribose (data not shown).

Distribution of HMO central moiety utilisation-associated genes across the Bifidobacterium genus

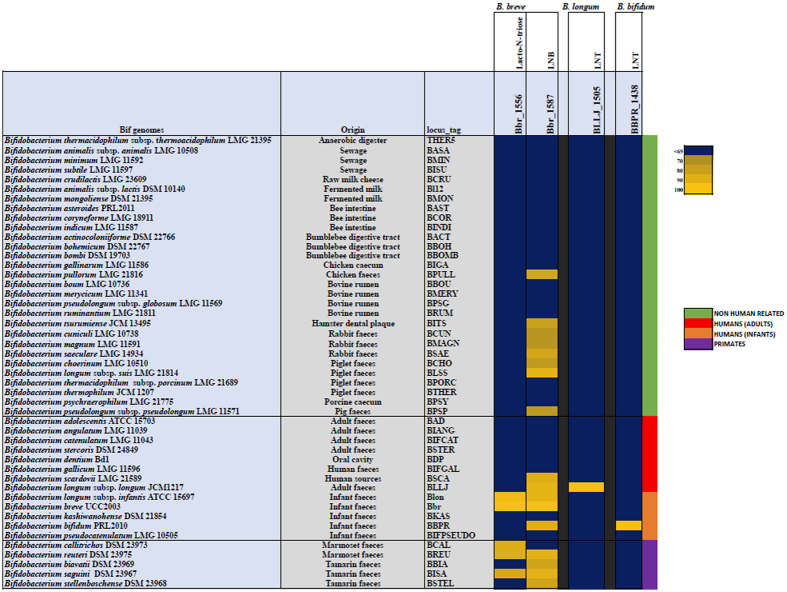

Two signature genes, encoding glycoside hydrolases essential to the catabolic pathways of HMO central moieties LNT, LNnT and LNB, in B. breve, were identified based on the above results for B. breve UCC2003 (Supplemental Table S3). The nahA gene was identified as being crucial for the degradation of both LNT and LNnT (through the hydrolysis of lacto-N-triose), and lnbP was identified as essential for the utilisation of LNB. Additionally, one signature gene, lnbB, was identified in B. bifidum as encoding the key glycoside hydrolase required for the metabolism of LNT, based on previous literature32 (Supplemental Table S3). Another distinct glycoside hydrolase required for the metabolism of LNT in this same way, lnbX, was identified in a strain of B. longum subsp. longum by Sakurama et al.37, and thus was also selected (Supplemental Table S3). No genes were selected from B. longum subsp. infantis, as this species and B. breve appear to share the same functional homologs and thus appear to utilize the same pathways for the metabolism of LN(n)T and LNB. The deduced amino acid sequences of these four genes were employed as the reference sequences in a multiple alignment of all available Bifidobacterium genomes retrieved from the NCBI database, as described, and represented in a heatmap, based on a cut-off of 70% iterative similarity over 50% protein length, and an e-value of <0.0001 (Fig. 5). The representation obtained, ordered by origin of isolation, reveals the distribution of these key genes, and thus the metabolic pathways, required for LN(n)T/LNB utilisation across the Bifidobacterium genus. The B. bifidum gene lnbB and B. longum subsp. longum gene lnbX (whose products are responsible for the hydrolysis of LNT into LNB and lactose) appear to be individually unique to B. bifidum and (this species of) B. longum subsp. longum, respectively, with no clear homologs in any other species of Bifidobacterium including each other. The two B. breve signature genes used in the search yielded multiple significant hits for homologs, but to differing degrees. The analysis identified a relatively small number, i.e. four homologous nahA genes across the genus: one in the infant-associated species B. longum subsp. infantis, two in marmoset-associated and one tamarin-associated species- B. callittrichos, B. ruteri, and B. saguini, respectively. On the other hand, lnbP yielded 16 significant matches to homologous genes in other Bifidobacterium species, isolated from both human and non-human-related sources. The significant differences in the conservation of these genes across the genus are indicative of the importance of specific glycan moiety-utilising pathways in bifidobacteria.

Figure 5. Heatmap representing the distribution of homologs of two genes from B. breve UCC2003, one gene from B. longum subsp. longum JCM1217 and one gene from B. bifidum PRL2010 across the Bifidobacterium genus.

Gene products from the representative strain genomes of all online-available Bifidobacterium species with a significant homology of 70% iterative similarity over 50% of protein length are represented in the matrix, which employs a code colour grading that represents the degree of sequence similarity, with species ordered by origin of isolation. Bbr_1556 (nahA) and Bbr_1587 (lnbP) were selected from B. breve UCC2003, BLLJ_1505 (lnbX) was selected from B. longum subsp. longum JCM1217, and BBPR_1438 (lnbB) was selected from B. bifidum PRL2010.

Discussion

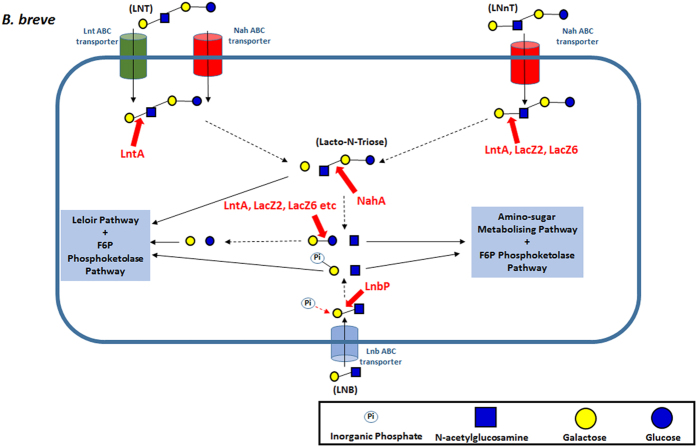

The role of HMOs as a selective substrate, for specific bacterial species in the neonatal gut, is now widely proposed as one of the key factors in the development of a healthy microbiota in early life. The high proportion of bifidobacteria, specifically the species B. breve, B. longum subsp. infantis and B. bifidum, in the microbiota of breastfed infants indicates their ability to utilise these carbohydrates as growth factors. Our findings allow us to propose a model for the utilisation of HMOs LN(n)T by B. breve (Fig. 6). In this model, LN(n)T is internalised by the cell and subsequently degraded by intracellular pathways into monosaccharides for energy production. While B. breve is able to metabolize smaller HMO components, such as fucose, fucosyllactose and sialic acid, which are released through extracellular hydrolysis of larger molecules16,17,22,39,40, our findings clearly show that B. breve can also utilise larger HMO structures. This expands our view of this gut commensal from being merely a scavenger, to an active and direct HMO utilizer.

Figure 6. Schematic representation of the proposed model for the metabolism of free LNT, LNnT and LNB by B. breve UCC2003.

Our multi-pronged approaches reveal the activities of individual components and thus the overall pathways that facilitate LNT and LNnT utilisation by B. breve UCC2003. LntA exhibits a triple specificity for the Galβ-1,3GlcNAc and Galβ-1,4GlcNAc linkages of LNT and LNnT, as well as the Galβ-1,4Glc moiety of lactose, as previously suggested42. However, the ability of UCC2003-lntA to grow on LNnT, but not on LNT, indicates that while LNT can only be intracellularly hydrolysed by LntA, the hydrolysis of LNnT is not exclusively attributable to this β-galactosidase, and can be degraded by other cellular glycoside hydrolases such as LacZ6 and LacZ2, releasing lacto-N-triose for hydrolysis by NahA, and galactose. It should be noted that both lacZ2 and lacZ6 have previously been shown to be involved in the metabolism of lactose and galacto-oligosaccharides42. Interestingly, these results mirror those previously shown by Yoshida et al.29, who, in B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC15697, demonstrated the preferential activities of one GH42 family glycoside hydrolase (Bga42A) in hydrolysing Type I HMOs and one GH2 family glycoside hydrolase (Bga2A) in hydrolysing Type II HMOs and lactose.

The transcriptomic results clearly implicate nahS, lntS, lntP1 and lntP2 in the utilisation on both LNT and LNnT, being involved in the internalisation of these sugars into the cell. The inability of the UCC2003-nahS mutant to grow on LNnT suggests the role of the nah locus-encoded transporter as the sole system responsible for LNnT internalisation by UCC2003. In contrast, since UCC2003-nahS displays growth on LNT comparable to that of the wild type strain, the nah transport system may not be involved in LNT transport, or may be, but with its function aided by one or more additional transport systems. The ability of the UCC2003-lntP1 and UCC2003-lntS to grow in mMRS supplemented with LNT demonstrates that the lnt transport system is also not exclusively, or potentially, at all, responsible for LNT internalisation. We therefore suggest that either these two transport systems may have at least partially overlapping substrate specificities, or that another yet undetermined transport system is partially, or wholly responsible for the internalisation of LNT.

While LNT and LNnT enter the B. breve cell as distinct isomers, their degradation products are identical and are shuttled through the same metabolic routes for energy production, i.e. two galactose molecules and one glucose to the Leloir and F6P phosphoketolase pathways and one GlcNAc to the amino-sugar metabolising pathway (thus both directly and indirectly feeding into the Bifid Shunt) (Fig. 6).

Although found within the molecular structure of LNT, free LNB is not released during the degradation of the Type I HMO central moiety by B. breve UCC2003. However, despite the relative low abundance of free LNB in human breast milk and thus the breastfed infant gut, B. breve UCC2003 possesses a distinct pathway for LNB utilisation. It has previously been suggested that LNB metabolism can be seen as a proxy for HMO utilisation by Bifidobacteria17,28, which explains the presence of this pathway in B. breve, which likely ‘sweeps up’ the free LNB released by the extracellular hydrolysis of larger HMO structures by other microbiota members, such as B. bifidum, and then utilise it via the GNB/LNB pathway.

The general model of LN(n)T and LNB utilisation in B. breve is mirrored by that found in B. longum subsp. infantis. The functional equivalent of lacZ2 and lacZ6 in B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC15697 is bga2a29. The ortholog of lntA is bga42a29, and the counterpart of nahA is nagZ30. A copy of lnbP is also found in B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC1569731. In contrast, HMO central moiety utilisation in B. bifidum diverges somewhat from the B. breve/B. longum subsp. infantis model. While B. bifidum possesses functionally equivalent orthologs of lacZ2/lacZ6 (bbgIII)50, and a nahA (bbhI and bbhII)34, all of these appear to be extracellular proteins, as opposed to the (predicted) intracellular localisation of their B. breve counterparts. However, the biggest defining factor separating the B. breve/B. longum subsp. infantis model and the B. bifidum model appears to be the hydrolysis pathway of Type I central moiety LNT. In B. bifidum PRL2010 LnbB hydrolyses LNT extracellularly at its GlcNAcβ1-3Gal linkage, releasing LNB, which is internalised, and phosphorolysed by lnbP1 and lnbP2; and lactose, which is hydrolysed by β-galactosidase activities.

The absence of B. bifidum lnbB (and B. longum subsp. longum JCM1217 lnbX) homologs in other Bifidobacterium species highlights its unique function in HMO metabolism. This agrees with previous knowledge, as already mentioned, of B. bifidum (and one strain of B. longum subsp. longum) utilizing a significantly different pathway for LNT utilisation, and of HMO metabolism as compared to B. breve and B. longum subsp. infantis. A similarity search for the two B. breve LN(n)T/LNB signature genes, nahA and lnbP, among bifidobacteria shows the presence of homologs in various species of Bifidobacterium, but the extent of their conservation differs considerably. The sixteen species of Bifidobacterium that were shown to possess an lnbP homolog, have been isolated from a range of environments, including faecal samples of (both infant and adult) humans, primates and other mammals. The conservation of this gene across various bifidobacterial species points toward the importance of this gene in the GNB/LNB pathway, which is common to many Bifidobacterium species, and has previously been shown to function in roles such as mucin metabolism28,46,51,52. Interestingly, clear homologs of the nahA gene are only found in four other bifidobacterial species, the human isolate B. longum subsp. infantis, and three other primate-associated species B. callitrichos and B. reuteri, originally isolated from marmoset faeces, and B. sanguini, originally isolated from tamarin faeces. As LNT and similar oligosaccharide structures can be found in the glycome of primate milk53, the nahA homologs are expected to play a similar role in Bifidobacterium species associated with these hosts. This suggests a common adaptation of the LNT/LNnT-utilisation pathway among bifidobacteria associated with the primate gut, using their respective milk oligosaccharides as substrates, thereby explaining co-evolution with and colonisation of this host.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S2. B. breve UCC2003 was routinely cultured in either de Man Rogosa and Sharpe medium (MRS medium; Difco, BD, Le Pont de Claix, France) supplemented with 0.05% cysteine-HCl or reinforced clostridial medium (RCM; Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, England). Carbohydrate utilization by bifidobacterial strains was examined in modified de Man Rogosa and Sharpe (mMRS) medium prepared from first principles54, and excluding a carbohydrate source. Prior to inoculation, the mMRS medium was supplemented with cysteine-HCl (0.05%, wt/vol) and a particular carbohydrate source (1%, wt/vol). It has previously been shown that mMRS does not support growth of B. breve UCC2003 in the absence of an added carbohydrate55. Carbohydrates used were lactose (Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany), LNB (Elicityl Oligotech, Crolles, France), lactosamine-hydrochloride (lactosamine-HCl) (Glycom, Lyngby, Denmark), LNT (Glycom, Lyngby, Denmark; Elicityl Oligotech, Crolles, France) and LNnT (Glycom, Lyngby, Denmark). A 1% wt/vol concentration of carbohydrate was considered sufficient to analyse the growth capabilities of a strain on a particular carbon source. The addition of these carbohydrates did not significantly alter the pH of the medium, and therefore subsequent pH adjustment was not required.

B. breve cultures were incubated under anaerobic conditions in a modular atmosphere-controlled system (Davidson and Hardy, Belfast, Ireland) at 37 °C. Lactococcus lactis strains were cultivated in M17 broth (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, England) containing 0.5% glucose56 at 30 °C. Escherichia coli strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth57 at 37 °C with agitation. Where appropriate, growth media contained tetracycline (Tet; 10 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (Cm; 5 μg ml−1 for L. lactis and E. coli, 2.5 μg ml−1 for B. breve), erythromycin (Em; 100 μg ml−1) or kanamycin (Kan; 50 μg ml−1). Recombinant E. coli cells containing (derivatives of) pORI19 were selected on LB agar containing Em and Kan, and supplemented with X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-galactopyranoside) (40 μg ml−1) and 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-D-galactopyranoside). In order to determine bacterial growth profiles and final optical densities, 5 ml of freshly prepared mMRS medium, including a particular carbohydrate (see above), was inoculated with 50 μl (1%) of a stationary phase culture of B. breve UCC2003. Uninoculated mMRS medium was used as a negative control. Cultures were incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 24 h, and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was determined manually, or using a PowerWave microplate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., USA) in conjunction with Gen5 microplate software for Windows, at the end of this period, as described previously55,58.

Bifidobacterium breve Growth Assays

Growth profiles of sixteen distinct Bifidobacterium breve strains from the UCC collection (listed in Supplemental Table S2) on LNT or LNnT, as the sole carbohydrate source, using lactose as a positive control, were determined in mMRS, using the microplate spectrophotometer, as described above. LNB and lactosamine-HCl were not included in these assays, as sufficient (and affordable) quantities of these carbohydrate substrates could not be obtained.

Growth profiles of insertion mutant, Tn5 transposon mutant, and complementation strains of B. breve UCC2003 generated in this and other studies, were determined, manually, as described above, adopting LNT, LNnT or LNB as carbohydrate source and in each case using lactose as a positive control.

Nucleotide sequence analysis

Sequence data were obtained from the Artemis-mediated59 genome annotations of B. breve UCC200360. Database searches were performed using non-redundant sequences accessible at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST)61,62. Sequences were verified and analysed using the SeqMan and SeqBuilder programs of the DNAStar software package (version 10.1.2; DNAStar, Madison, WI, USA). Gene product (protein) localisation and signal peptide predictions were made using the TMHMM, v. 2.0 and SignalP, v. 4.163 servers, respectively, available at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/.

DNA Manipulations

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from B. breve UCC2003 as previously described64. Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli, L. lactis and B. breve using the Roche High Pure Plasmid Isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). An initial lysis step was performed using 30 mg ml−1 of lysozyme for 30 minutes at 37 °C prior to plasmid isolation from L. lactis or B. breve. DNA manipulations were essentially performed as described previously57. All restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were used according to the supplier’s instructions (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Synthetic single stranded oligonucleotide primers used in this study (Supplemental Table S1) were synthesized by Eurofins (Ebersberg, Germany). Standard PCRs were performed using Taq PCRmaster mix (Qiagen) or Extensor Hi-Fidelity PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, United States) in a Life Technologies Proflex PCR System (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, United States). PCR products were visualized by ethidium bromide (EtBr) staining following agarose gel electrophoresis (1% agarose). B. breve colony PCR reactions were performed as described previously65. PCR fragments were purified using the Roche high Pure PCR purification kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Plasmid DNA was isolated using the Roche High Pure Plasmid Isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Plasmid DNA was introduced into E. coli by electroporation as described previously57. B. breve UCC200366 and L. lactis67 were transformed by electroporation according to published protocols. The correct orientation and integrity of all plasmid constructs (see also below) were verified by DNA sequencing, performed at Eurofins (Ebersberg, Germany).

Analysis of global gene expression using B. breve DNA microarrays

Global gene expression was determined during log-phase growth of B. breve UCC2003 in mMRS supplemented with either LNT, LNnT, LNB, lactosamine-HCl or lactose. The obtained transcriptome was compared to that determined for log-phase B. breve UCC2003 cells when grown in mMRS supplemented with ribose. DNA microarrays containing oligonucleotide primers representing each of the 1864 identified open reading frames on the genome of B. breve UCC2003 were designed and obtained from Agilent Technologies (Palo Alto, Ca., USA). Methods for cell disruption, RNA isolation, RNA quality control, complementary DNA synthesis and labelling were performed as described previously68. Labelled cDNA was hybridized using the Agilent Gene Expression hybridization kit (part number 5188-5242) as described in the Agilent Two-Colour Microarray-Based Gene Expression Analysis v4.0 manual (publication number G4140-90050). Following hybridization, microarrays were washed in accordance with Agilent’s standard procedures and scanned using an Agilent DNA microarray scanner (model G2565A). Generated scans were converted to data files with Agilent’s Feature Extraction software (Version 9.5). DNA-microarray data were processed as previously described69,70,71. Differential expression tests were performed with the Cyber-T implementation of a variant of the t-test72.

Construction of B. breve UCC2003 insertion mutants

An internal fragment of Bbr_0530 (designated here as lntS) (465 bp, representing codon numbers 61 through to 216 of the 420 codons of this gene), Bbr_1554 (designated here as nahS) (488 bp, representing codon numbers 92 through to 255 of the 442 codons of this gene), and Bbr_1556 (designated here as nahA) (443 bp, representing codon numbers 70 through to 218 of the 660 codons of this gene) were amplified by PCR using B. breve UCC2003 chromosomal DNA as a template and primer pairs IM530F and IM530R, IM1554F and IM1554R, or IM1556F and IM1556R, respectively (Supplemental Table S1). The insertion mutants were constructed using a previously described approach65. Site-specific recombination of potential tet-resistant mutant isolates was confirmed by colony PCR using primer combinations tetWFw and tetWRv to verify tetW gene integration, and primers 530confirm1 or 530confirm2, 1554Confirm1 or 1554Confirm2, and 1556confirm1 or 1556confirm2 (positioned upstream of the selected internal fragments of Bbr_0530, Bbr_1554 and Bbr_1556, respectively) in combination with primer tetWFw to confirm integration at the correct chromosomal location (Supplemental Table S1).

Complementation of B. breve insertion mutants

DNA fragments encompassing Bbr_0529 (designated here as lntA), Bbr_1554 (nahS) and Bbr_1556 (nahA) were generated by PCR amplification from B. breve UCC2003 chromosomal DNA using Q5 High-Fidelity Polymerase (New England BioLabs, Herefordshire, United Kingdom) and primer pairs: 529pNZ44F and 529pNZ44R, 1554PCB1.2F and 1554PBC1.2R, and 1556PBC1.2F and 1556PBC1.2R, respectively (Supplemental Table S1).

The resulting lntA-encompassing fragment was digested with PstI and XbaI, and ligated to the similarly digested pNZ4473. The ligation mixture was introduced into L. lactis NZ9000 by electrotransformation and transformants were then selected based on chloramphenicol resistance. The plasmid content of a number of Cm-resistant transformants was screened by restriction analysis. The integrity of the cloned insert of one of the recombinant plasmids, designated pNZ44-lntA, was confirmed by sequencing. The lntA-coding sequence, together with the constitutive p44 lactococcal promoter, specified by pNZ44, was amplified by PCR from pNZ44-lntA using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA polymerase and primer combination P44 Forward and 529pNZ44R (Supplemental Table S1). The resulting DNA fragment was digested with EcoRV and XbaI, and ligated to the similarly digested pBC1.274, generating pBC1.2-lntA.

PCR-generated DNA fragments encompassing nahS and nahA, including their presumed promoter regions, were digested with BamHI and XbaI, and ligated to the similarly digested pBC1.2 to generate pBC1.2-nahS or pBC1.2-nahA, respectively. The ligation mixtures were introduced into E. coli XL1-blue by electrotransformation and transformants selected based on tetracycline and chloramphenicol resistance. Transformants were checked for plasmid content using colony PCR, restriction analysis of plasmid DNA, and verified by sequencing. Plasmids pBC1.2-lntA, pBC1.2-nahS or pBC1.2-nahA were introduced into the insertion mutant B. breve UCC2003-lntA, B. breve UCC2003-nahS and B. breve UCC2003-nahA42, respectively, by electrotransformation and transformants were selected based on tetracycline and chloramphenicol resistance.

Construction of overexpression vectors, protein overproduction and purification

For the construction of the plasmid pNZ-nahA, a DNA fragment encompassing the predicted N-acetylhexosaminidase-encoding gene nahA was generated by PCR amplification from chromosomal DNA of B. breve UCC2003 using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA polymerase and the primer combination 1556F and 1556R (Supplemental Table S1). An in-frame N-terminal His10-encoding sequence was incorporated into the forward primer 1556F to facilitate downstream protein purification. The generated amplicons were digested with PvuII and XbaI, and ligated into the ScaI and XbaI-digested, nisin-inducible translational fusion plasmid pNZ815075. The ligation mixtures were introduced into L. lactis NZ9000 by electrotransformation and transformants were then selected based on chloramphenicol resistance. The plasmid content of a number of Cm-resistant transformants was screened by restriction analysis and the integrity of positively identified clones was verified by sequencing.

Nisin-inducible gene expression and protein overproduction was performed as described previously76,77,78. In brief, 400 ml of M17 broth supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose was inoculated with a 2% inoculum of a particular L. lactis strain, followed by incubation at 30 °C until an OD600 of 0.5 was reached, at which point protein expression was induced by addition of cell-free supernatant of a nisin-producing strain79, followed by continued incubation for a further 2 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and protein purification achieved as described previously76. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford method80.

Assay of individual and combined β-Galactosidase activities

The individual or sequential hydrolytic activities specified by lntA (corresponding to Bbr_0529), nahA (corresponding to Bbr_1556), lacZ2 (corresponding to Bbr_0010) and lacZ6 (corrsponding to Bbr_1552) were determined essentially as described previously78, using LNT, LNnT or lactose as a substrate. Briefly, a 50-μl volume of each purified protein (protein concentration of 0.5 mg/ml) was added to 20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (pH 7.0) buffer and 1 mg ml−1 (wt/vol) of one of the above-mentioned sugars in a final volume of 1 ml, followed by incubation for 24 hours at 37 °C. When sequential activities were assessed, a sample was heated to 85 °C for 15 minutes following 12 hour incubation with the first enzyme and a given substrate, before the addition of the addition of a second enzyme, which was then followed by a further 12-hour incubation at 37 °C. All samples were subject to a final enzyme denaturation step at 85 °C for 15 minutes, before storage at −20 °C.

HPAEC-PAD analysis

For HPAEC-PAD analysis, a Dionex (Sunnyvale, CA) ICS-3000 system was used. Carbohydrate fractions from the above-mentioned hydrolysis assays (25 μl aliquots) were separated on a CarboPac PA1 analytical-exchange column (dimensions, 250 mm by 4 mm) with a CarboPac PA1 guard column (dimensions, 50 mm by 4 mm) and a pulsed electrochemical detector (ED40) in PAD mode (Dionex). Elution was performed at a constant flow-rate of 1.0 ml/min at 30 °C using the following eluents for the analysis: eluent A, 200 mM NaOH; eluent B, 100 mM NaOH plus 550 mM Na acetate; eluent C, Milli-Q water. The following linear gradient of sodium acetate was used with 100 mM NaOH: from 0 to 50 min, 0 mM; from 50 to 51 min, 16 mM; from 51 to 56 min, 100 mM; from 56 to 61 min, 0 mM. Chromatographic profiles of standard carbohydrates were used for comparison of the results of their breakdown by LntA, LacZ2, LacZ6 and NahA proteins. Chromeleon software (version 6.70; Dionex Corporation) was used for the integration and evaluation of the chromatograms obtained. A 1 mg/ml stock solution of each of the carbohydrates, as well as their putative breakdown products (where available) used as reference standards was prepared by dissolving the particular sugar in Milli-Q water.

Bioinformatic Analysis

Based on the analysis of the microarray results and functional characterisation of gene loci from B. breve UCC2003, as well as previously published data on HMO utilisation by B. longum subsp. infantis and B. bifidum and B. longum subsp. longum18,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37, four genes were identified as crucial for the utilisation of Type I central moieties LNT and LNB, and Type II HMO moiety LNnT. On-line available genomic data sets of bifidobacteria were first retrieved from the NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and aligned using an all-vs-all BLASTP approach61, using 70% of iterative similarity across all available Bifidobacterium species over 50% of protein length and a 0.0001 e-value as a significance cut-off. The resulting alignment was subsequently clustered in MCL families of orthologous genes using the mclblastline algorithm81. The resulting output was used to first build a presence/absence binary matrix, and then the genes of interest were selected and represented in a heatmap employing a code colour grading that represents the degree of sequence similarity, with species ordered by origin of isolation. Bbr_1556 (nahA) and Bbr_1587 (lnbP) were selected from B. breve UCC2003, BLLJ_1505 (lnbX) from B. longum subsp. longum JCM1217 and BBPR_1438 (lnbB) was selected from B. bifidum PRL2010.

Microarray data accession number

The microarray data obtained in this study have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE84710.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: James, K. et al. Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 metabolises the human milk oligosaccharides lacto-N-tetraose and lacto-N-neo-tetraose through overlapping, yet distinct pathways. Sci. Rep. 6, 38560; doi: 10.1038/srep38560 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank Glycom A/S (Lyngby, Denmark) for the provision of purified HMO samples used in this study under their donation program. This study was funded in part by the Irish Research Council, under the Postgraduate Research Project Award; Project ID GOIPG/2013/651. In addition, the authors are supported by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) (Grant No. SFI/12/RC/2273) and Mary O’Connell Motherway is a recipient of a HRB postdoctoral fellowship (Grant No. PDTM/20011/9).

Footnotes

Author Contributions D.v.S., K.J. and M.O.C.M. conceived the experiments. K.J. conducted the experiments. K.J. and F.B. conducted the bioinformatic analysis. All authors analysed the results and contributed to writing the manuscript.

References

- Engfer M. B., Stahl B., Finke B., Sawatzki G. & Daniel H. Human milk oligosaccharides are resistant to enzymatic hydrolysis in the upper gastrointestinal tract. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 71, 1589–1596 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz C., Rudloff S., Baier W., Klein N. & Strobel S. OLIGOSACCHARIDES IN HUMAN MILK: Structural, Functional, and Metabolic Aspects. Annual Review of Nutrition 20, 699–722, doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.699 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüssow H. Human microbiota: ‘The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways. The point, however, is to change it’. Microbial Biotechnology 8, 11–12, doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12259 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morowitz M. J., Poroyko V., Caplan M., Alverdy J. & Liu D. C. Redefining the Role of Intestinal Microbes in the Pathogenesis of Necrotizing Enterocolitis. Pediatrics 125, 777–785, doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3149 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim K. et al. Dysbiosis Anticipating Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Very Premature Infants. Clinical Infectious Diseases 60, 389–397, doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu822 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gioia D., Aloisio I., Mazzola G. & Biavati B. Bifidobacteria: their impact on gut microbiota composition and their applications as probiotics in infants. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 98, 563–577, doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5405-9 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amisano G. et al. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in acute gastroenteritis in infants in North-West Italy. The new microbiologica 34, 45–51 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matamoros S., Gras-Leguen C., Le Vacon F., Potel G. & de La Cochetiere M. F. Development of intestinal microbiota in infants and its impact on health. Trends in microbiology 21, 167–173, doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.12.001 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turroni F. et al. Diversity of Bifidobacteria within the Infant Gut Microbiota. PLoS ONE 7, e36957, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036957 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone M. et al. The Probiotic Bifidobacterium breve B632 Inhibited the Growth of Enterobacteriaceae within Colicky Infant Microbiota Cultures. BioMed Research International 2014, 301053, doi: 10.1155/2014/301053 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gioia D., Aloisio I., Mazzola G. & Biavati B. Bifidobacteria: their impact on gut microbiota composition and their applications as probiotics in infants. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98, 563–577, doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5405-9 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kau A. L., Ahern P. P., Griffin N. W., Goodman A. L. & Gordon J. I. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome, and immune system: envisioning the future. Nature 474, 327–336, doi: 10.1038/nature10213 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowski K. M. & Mackay C. R. Diet, gut microbiota and immune responses. Nature immunology 12, 5–9, doi: 10.1038/ni0111-5 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivan A. et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti–PD-L1 efficacy. Science 350, 1084–1089, doi: 10.1126/science.aac4255 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S. et al. Cultivating Healthy Growth and Nutrition through the Gut Microbiota. Cell 161, 36–48, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.013 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonneau Mark R. et al. Sialylated Milk Oligosaccharides Promote Microbiota-Dependent Growth in Models of Infant Undernutrition. Cell 164, 859–871, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.024 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakuma S. et al. Physiology of Consumption of Human Milk Oligosaccharides by Infant Gut-associated Bifidobacteria. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 286, 34583–34592, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.248138 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela D. A. & Mills D. A. Nursing our microbiota: molecular linkages between bifidobacteria and milk oligosaccharides. Trends in microbiology 18, 298–307, doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.03.008 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakuma S. et al. Variation of major neutral oligosaccharides levels in human colostrum. Eur J Clin Nutr 62, 488–494, doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602738 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantscher-Krenn E. & Bode L. Human milk oligosaccharides and their potential benefits for the breast-fed neonate. Minerva pediatrica 64, 83–99 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela D. A. Bifidobacterial utilization of human milk oligosaccharides. International Journal of Food Microbiology 149, 58–64, doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.01.025 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoCascio R. G. et al. Glycoprofiling of Bifidobacterial Consumption of Human Milk Oligosaccharides Demonstrates Strain Specific, Preferential Consumption of Small Chain Glycans Secreted in Early Human Lactation. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55, 8914–8919, doi: 10.1021/jf0710480 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benno Y., Sawada K. & Mitsuoka T. The intestinal microflora of infants: composition of fecal flora in breast-fed and bottle-fed infants. Microbiol Immunol 28, 975–986 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guaraldi F. & Salvatori G. Effect of Breast and Formula Feeding on Gut Microbiota Shaping in Newborns. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2, 94, doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00094 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solís G., de los Reyes-Gavilan C. G., Fernández N., Margolles A.& Gueimonde M. Establishment and development of lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria microbiota in breast-milk and the infant gut. Anaerobe 16, 307–310, doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.02.004 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H. et al. Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense sp. nov., isolated from healthy infant faeces. International journal of systematic and evolutionary microbiology 61, 2610–2615, doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.024521-0 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Gutierrez P. et al. Bifidobacteria strains isolated from stools of iron deficient infants can efficiently sequester iron. BMC microbiology 15, 3, doi: 10.1186/s12866-014-0334-z (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaoka M. Bifidobacterial enzymes involved in the metabolism of human milk oligosaccharides. Adv Nutr 3, 422s–429s, doi: 10.3945/an.111.001420 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida E. et al. Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis uses two different beta-galactosidases for selectively degrading type-1 and type-2 human milk oligosaccharides. Glycobiology 22, 361–368, doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr116 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido D., Ruiz-Moyano S. & Mills D. A. Release and utilization of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine from human milk oligosaccharides by Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis. Anaerobe 18, 430–435, doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2012.04.012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J. Z. et al. Distribution of in vitro fermentation ability of lacto-N-biose I, a major building block of human milk oligosaccharides, in bifidobacterial strains. Applied and environmental microbiology 76, 54–59, doi: 10.1128/aem.01683-09 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada J. et al. Bifidobacterium bifidum lacto-N-biosidase, a critical enzyme for the degradation of human milk oligosaccharides with a type 1 structure. Applied and environmental microbiology 74, 3996–4004, doi: 10.1128/aem.00149-08 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada J. et al. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of the galacto-N-biose-/lacto-N-biose I-binding protein (GL-BP) of the ABC transporter from Bifidobacterium longum JCM1217. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun 63, 751–753, doi: 10.1107/s1744309107036263 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa M. et al. Cooperation of beta-galactosidase and beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase from bifidobacteria in assimilation of human milk oligosaccharides with type 2 structure. Glycobiology 20, 1402–1409, doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwq101 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela D. A. et al. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis reveals adaptations for milk utilization within the infant microbiome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 18964–18969, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809584105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller P. L., Jørgensen F., Hansen O. C., Madsen S. M. & Stougaard P. Intra- and Extracellular β-Galactosidases from Bifidobacterium bifidum and B. infantis: Molecular Cloning, Heterologous Expression, and Comparative Characterization. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 67, 2276–2283, doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.5.2276-2283.2001 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurama H. et al. Lacto-N-biosidase Encoded by a Novel Gene of Bifidobacterium longum Subspecies longum Shows Unique Substrate Specificity and Requires a Designated Chaperone for Its Active Expression. The Journal of biological chemistry 288, 25194–25206, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.484733 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Moyano S. et al. Variation in consumption of human milk oligosaccharides by infant-gut associated strains of Bifidobacterium breve. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, doi: 10.1128/aem.01843-13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan M., O’Connell Motherway M., Ventura M. & van Sinderen D. Metabolism of sialic acid by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, doi: 10.1128/aem.01114-14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki T. et al. A key genetic factor for fucosyllactose utilization affects infant gut microbiota development. Nat Commun 7, doi: 10.1038/ncomms11939 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokusaeva K. et al. Ribose utilization by the human commensal Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Microb Biotechnol 3, 311–323, doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00152.x (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell Motherway M., Kinsella M., Fitzgerald G. F. & van Sinderen D. Transcriptional and functional characterization of genetic elements involved in galacto-oligosaccharide utilization by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Microb Biotechnol 6, 67–79, doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12011 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto M. & Kitaoka M. Identification of N-Acetylhexosamine 1-Kinase in the Complete Lacto-N-Biose I/Galacto-N-Biose Metabolic Pathway in Bifidobacterium longum. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 73, 6444–6449, doi: 10.1128/AEM.01425-07 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitaoka M., Tian J. & Nishimoto M. Novel Putative Galactose Operon Involving Lacto-N-Biose Phosphorylase in Bifidobacterium longum. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 71, 3158–3162, doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3158-3162.2005 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turroni F. et al. Ability of Bifidobacterium breve To Grow on Different Types of Milk: Exploring the Metabolism of Milk through Genome Analysis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 77, 7408–7417, doi: 10.1128/aem.05336-11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan M. et al. Cross-feeding by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 during co-cultivation with Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 in a mucin-based medium. BMC Microbiology 14, 282, doi: 10.1186/s12866-014-0282-7 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derensy-Dron D., Krzewinski F., Brassart C. & Bouquelet S. Beta-1,3-galactosyl-N-acetylhexosamine phosphorylase from Bifidobacterium bifidum DSM 20082: characterization, partial purification and relation to mucin degradation. Biotechnology and applied biochemistry 29 (Pt 1), 3–10 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Martin P. et al. A two-component regulatory system controls autoregulated serpin expression in Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Applied and environmental microbiology 78, 7032–7041, doi: 10.1128/aem.01776-12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz L., Motherway M. O., Lanigan N. & van Sinderen D. Transposon mutagenesis in Bifidobacterium breve: construction and characterization of a Tn5 transposon mutant library for Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. PLoS One 8, e64699, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064699 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulas T. K., Goulas A. K., Tzortzis G. & Gibson G. R. Molecular cloning and comparative analysis of four beta-galactosidase genes from Bifidobacterium bifidum NCIMB41171. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 76, 1365–1372, doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1099-1 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki R. et al. Crystallographic and mutational analyses of substrate recognition of endo-alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminidase from Bifidobacterium longum. Journal of biochemistry 146, 389–398, doi: 10.1093/jb/mvp086 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita K. et al. Identification and molecular cloning of a novel glycoside hydrolase family of core 1 type O-glycan-specific endo-alpha-N-acetylgalactosaminidase from Bifidobacterium longum. The Journal of biological chemistry 280, 37415–37422, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506874200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao N. et al. Evolutionary Glycomics: Characterization of Milk Oligosaccharides in Primates. Journal of proteome research 10, 1548–1557, doi: 10.1021/pr1009367 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Man J. C., Rogosa M. & Sharpe M. E. A medium for the cultivation of 688 lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 23, 130–135 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. et al. Selective carbohydrate utilization by lactobacilli and bifidobacteria. Journal of applied microbiology 114, 1132–1146, doi: 10.1111/jam.12105 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terzaghi B. E. & Sandine W. E. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Microbiol 29, 807–813 (1975). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J F. E. & Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin H. P. et al. Carbohydrate catabolic diversity of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli of human origin. International journal of food microbiology 203, 109–121, doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.03.008 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K. et al. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16, 944–945 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell Motherway M. et al. Functional genome analysis of Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 reveals type IVb tight adherence (Tad) pili as an essential and conserved host-colonization factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 11217–11222, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105380108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W. & Lipman D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215, 403–410, doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25, 3389–3402 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen T. N., Brunak S., von Heijne G. & Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Meth 8, 785–786, doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Riordan K. & Fitzgerald G. F. Molecular characterisation of a 5.75-kb cryptic plasmid from Bifidobacterium breve NCFB 2258 and determination of mode of replication. FEMS Microbiol Lett 174, 285–294 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]