Abstract

A Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strain isolated from a patient hospitalized in a New Delhi, India, hospital was resistant to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, imipenem, and aztreonam. A blaVEB-1-like gene named blaVEB-1a, which codes for the extended-spectrum β-lactamase VEB-1a, was identified. The genetic environment of blaVEB-1a was peculiar: (i) no 5′ conserved sequence (5′-CS) region was present upstream of the β-lactamase gene, whereas blaVEB-1-like genes are usually associated with class 1 integrons; (ii) blaVEB-1a was inserted between two truncated 3′-CS regions in a direct repeat; and (iii) four 135-bp repeated DNA sequences (repeated elements) were located on each side of the blaVEB-1a gene. Expression of the blaVEB-1a gene was driven by a strong promoter located in one of these repeated sequences. In addition, cloning of the β-lactamase content of this P. aeruginosa isolate followed by expression in Escherichia coli identified the naturally occurring AmpC β-lactamase and a gene encoding an OXA-2-like β-lactamase located in a class 1 integron, In78, in which an insertion sequence, ISpa7, was inserted within its 5′-CS region.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa has intrinsic resistance to aminopenicillins and narrow-spectrum cephalosporins due to combined mechanisms, such as cephalosporinase (AmpC) production (4) and an outer membrane permeability defect. Resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins results mostly from overexpression of the cephalosporinase and from acquired β-lactamases (7). In addition to the TEM- and SHV-types β-lactamases, non-TEM, non-SHV (1, 35) extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) of Ambler class A have been detected in P. aeruginosa and in some cases have been shown to have a specific geographical distribution; e.g., PER-1 is widespread in Turkey, and VEB-1 is widespread in Southeast Asia (11, 12, 33).

The blaVEB-1 gene was reported first from an Escherichia coli isolate from a Vietnamese patient, in which it was located on a plasmid and an integron (26). Subsequently, it was detected in two P. aeruginosa isolates from Thailand, in which it was found to be located chromosomally and on an integron (19, 32). Then, β-lactamase VEB-1 was identified in a series of gram-negative rods, which underlines its interspecies spread. Several surveys in Thailand and Vietnam emphasized the widespread nature of VEB-1 in Southeast Asia (5, 6, 11, 12, 18). In addition, VEB-1 had been detected in Kuwait (27) and was recently identified in many Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in France (25).

Four VEB-1-like β-lactamases that share 99% amino acid identity with VEB-1 have been characterized: VEB-1a (11), VEB-1b (11), VEB-2 (27), and VEB-3 (GenBank accession number AAS48620; X. Jiang, unpublished data). Compared to VEB-1, VEB-1a has only one amino acid substitution (I18V), which occurs in the leader peptide. The β-lactamase specific activities determined for E. coli DH10B clones expressing VEB-1 and VEB-1a were similar for the β-lactams tested (P. Nordmann, unpublished data). The hydrolytic properties of the other variants have not been studied.

We analyzed the β-lactamase content of a multiresistant P. aeruginosa clinical isolate from India. We report on the identification in India of the VEB-1a β-lactamase, which had been detected in Kuwait (27), further underlining the spread of blaVEB-1-like genes in Asia. Until now, the blaVEB-1-like genes had always been found to be inserted within the variable regions of class 1 integrons and were mostly associated with the insertion sequence (IS) IS1999 in P. aeruginosa (2). In the present study, we characterize a blaVEB-1-like gene located in a novel and very peculiar genetic environment made up of repeated DNA sequences. These sequences that drive blaVEB-1-like expression likely represent a novel way for expression of antibiotic resistance genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, electroporation, and culture conditions.

Clinical strain P. aeruginosa 10.2 was isolated in 2000 from the infected urinary tract of a patient at the Batra Hospital and Medical Research Center in New Delhi, India. E. coli DH10B (Life Technologies, Eragny, France) was used as the bacterial host in electroporation experiments. Rifampin-resistant strains E. coli C600 and P. aeruginosa PU21 were used for the conjugation experiments. E. coli NCTC 50192 harboring 154-, 66-, 38-, and 7-kb plasmids (34) was used as a plasmid-containing reference strain for extraction by the method of Kieser (15). Recombinant plasmids pInt-Veb and pVeb (2), which possess the blaVEB-1 gene with and without the Pant promoter from class 1 integrons (8) cloned in the pBBR1MCS.3 vector in an orientation opposite that of the Plac promoter, were used for the promoter strength study. Low-copy-number cloning vector pBBR1MCS.3 (16) and phagemid pBK-CMV (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) were used for the cloning experiments. Electroporation into E. coli DH10B was performed as described previously (24). Bacterial cells were grown in Trypticase soy (TS) broth and on TS agar plates (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-La-Coquette, France).

Antimicrobial agents and susceptibility testing.

Routine antibiograms were determined by the disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur). The antimicrobial agents and their sources have been described elsewhere (17). The MICs of selected β-lactams were determined by an agar dilution method on MH plates with a Steers multiple inoculator (31) and an inoculum of 104 CFU/spot. MIC results were interpreted according to NCCLS guidelines (22). The double-disk synergy test was performed with cefepime and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid disks on MH agar plates. Double-disk tests were also performed on cloxacillin (250 μg/ml)-containing plates to inhibit the activity of the AmpC-type β-lactamase of P. aeruginosa (10).

Mating-out assay.

Conjugation experiments were attempted between isolate P. aeruginosa 10.2 as the donor and rifampin-resistant strains E. coli C600 and P. aeruginosa PU21 as the recipients in liquid and solid media at 37°C. The mating culture was plated onto TS agar plates containing ticarcillin (100 μg/ml) and rifampin (200 μg/ml).

Nucleic acid extractions.

Recombinant plasmids were extracted by use of Plasmid Mini-Midi kits (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France), whereas natural plasmids were extracted as described by Kieser (15). Whole-cell DNA from P. aeruginosa 10.2 was extracted as described elsewhere (24). Total RNAs were extracted with an RNeasy Maxi kit (Qiagen), according to the recommendations of the manufacturer.

PCR amplification, cloning experiments, and sequencing.

Taq and Pfu DNA polymerases were from Roche Diagnostics (Meylan, France) and Promega Corporation (Madison, Wis.), respectively. Standard PCR amplification experiments (30) were attempted with primers specific for the aadB, arr-2, cmlA5, and aadA1 genes and the genes coding for β-lactamases OXA-10, TEM, SHV, PER-1, VEB-1, and GES-1, as described previously (12). The PCR products were purified with Qiaquick columns (Qiagen).

T4 DNA ligase and restriction endonucleases were used according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Briefly, the cloning procedure resulted in the ligation of either PstI-, BamHI-, or HindIII-digested whole-cell DNA of P. aeruginosa 10.2 into the PstI-, BamHI-, or HindIII-restricted pBK-CMV vector, respectively. The ligation products were electroporated into E. coli DH10B, and selection was performed on TS agar plates containing amoxicillin (100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (30 μg/ml). Cloning of repeated element (Re) Re1, associated with the blaVEB-1a gene, was performed as follows: P. aeruginosa 10.2 whole-cell DNA and primer pair Re1F (5′-GCTTTGTCATGTCGACGCGCC-3′) and VebcasB (18) were used to amplify a 1.2-kb fragment that was cloned into SmaI-restricted vector pBBR1MCS.3. The ligation products were electroporated into E. coli DH10B, and selection was performed on TS agar plates containing amoxicillin (100 μg/ml) and tetracycline (30 μg/ml). One recombinant plasmid, pRe1-Veb, that possessed blaVEB-1a immediately downstream of element Re1 and in the orientation opposite that of Plac was retained for further analysis.

Sequencing was performed with laboratory-designed primers on an ABI PRISM 3100 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Les Ullis, France).

Transcription initiation.

Reverse transcription and rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) were performed with the 5′RACE system (version 2.0; Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Cergy Pontoise, France). Five micrograms of total RNA extracted from the culture of P. aeruginosa 10.2 and gene-specific primers blaVEB-1GSP1 (5′-TCAAAGTTGTTCCATTAGGGAATTCC-3′), blaVEB-1GSP2 (5′-GAAAGATTCCCTTTATCTATCTCAGACAA-3′), and blaVEB-1GSP3 (5′-TCAGTTTGAGCATTTGAATACAC-3′) were used to determine the blaVEB-1a transcription initiation site.

IEF analysis.

β-Lactamase extracts were prepared as described previously (11) and subjected to analytical isoelectric focusing (IEF) on a pH 3.5 to 9.5 ampholine polyacrylamide gel (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), as described elsewhere (17). The pI values of the β-lactamases extracted from P. aeruginosa 10.2 and the E. coli DH10B clones were determined by comparison with those of known β-lactamases (14).

Kinetic measurements.

β-Lactamase extracts from cultures of E. coli DH10B harboring recombinant plasmid pRe1-Veb, pInt-Veb, or pVeb were prepared as described previously (21). Enzyme extracts were used for determination of β-lactamase activity with cefuroxime (a good substrate for measurement of hydrolysis by VEB-1) as the substrate, and kinetic measurements were performed at 30°C in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7). The initial rates of cefuroxime hydrolysis were determined with an ULTROSPEC 2000 UV spectrophotometer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and total protein contents were measured by the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad), as described previously (26).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the blaOXA-2a and the blaVEB-1a environments reported in this paper have been submitted to the EMBL/GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession numbers AY444814 and AY444815, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Susceptibility testing.

The MICs showed that P. aeruginosa 10.2 was resistant to amino-, carboxy-, and ureido-penicillins; restricted- and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins; and imipenem and aztreonam (Table 1). The resistance to several β-lactams was partially reduced by clavulanic acid addition. Furthermore, a routine antibiogram revealed that P. aeruginosa 10.2 was resistant to most non-β-lactam antibiotics, including tetracycline, gentamicin, tobramycin, netilmicin, amikacin, kanamycin, ciprofloxacin, spectinomycin, streptomycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; had a reduced susceptibility to rifampin; and was susceptible to colistin.

TABLE 1.

MICs of β-lactams for clinical isolate P. aeruginosa 10.2; E. coli DH10B harboring recombinant plasmids pInt-Veb, pVeb, and pReI-Veb; and reference strain E. coli DH10B

| β-Lactamb | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa 10.2 | E. coli DH10B(pInt-Veb) | E. coli DH10B(pVeb) | E. coli DH10B(pRe1-Veb) | E. coli DH10B | |

| Ticarcillin | >512 | >512 | 64 | >512 | 4 |

| Ticarcillin-CLA | 64 | 8 | 4 | 32 | 4 |

| Piperacillin | 256 | 256 | 4 | >512 | 2 |

| Piperacillin-TZB | 16 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| Cefotaxime | 512 | 128 | 0.12 | 512 | 0.06 |

| Cefotaxime-CLA | 64 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.06 |

| Ceftazidime | >512 | >512 | 16 | >512 | 0.5 |

| Ceftazidime-CLA | 8 | 2 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.25 |

| Cefuroxime | >512 | >512 | 16 | >512 | 4 |

| Cefepime | 256 | 128 | 0.25 | >512 | 0.06 |

| Cefpirome | >512 | 128 | 0.06 | >512 | 0.06 |

| Aztreonam | 32 | >512 | 1 | >512 | 0.12 |

| Moxalactam | 64 | 2 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.12 |

| Imipenem | 16 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

Recombinant plasmids pInt-Veb and pVeb contained blaVEB-1, and pRe1-Veb contained blaVEB-1a.

CLA, clavulanic acid at a fixed concentration of 2 μg/ml; TZB, tazobactam at a fixed concentration of 4 μg/ml.

A synergy image was found between cefepime- and clavulanate-containing disks, which was best shown by using cloxacillin-containing MH agar plates (which inhibit cephalosporinase activity), which suggested the presence of an ESBL.

Preliminary PCR screening.

PCR experiments with primers specific for blaTEM, blaSHV, blaGES-1, and blaPER-1 were negative. A PCR product of 650 bp was obtained by using blaVEB-1-specific internal primers. Sequencing of the PCR product revealed 100% identity with a blaVEB-1-like gene. The blaVEB-1 gene had been described (19) as a gene cassette located within the variable region of class 1 integrons and often associated with the aadB, arr-2 (rifampin resistance marker), cmlA5, blaOXA-10, and aadA1 gene cassettes. No PCR product was obtained by using a series of combinations of primers whose sequences are specific for regions located in class 1 integron structures and the antibiotic resistance genes, suggesting that the genetic environment of blaVEB-1 in P. aeruginosa 10.2 could be different from that of known blaVEB-1-containing integrons.

Cloning of β-lactamase genes.

Several E. coli transformants were obtained in each cloning experiment. Disk diffusion antibiograms revealed three distinct β-lactam resistance profiles. (i) The first phenotype showed resistance to amino-, carboxy-, and ureido-penicillins; restricted- and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins; and aztreonam. A synergy between clavulanic acid and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins suggested the presence of an ESBL that was consistent with the expression of the clavulanate-inhibited VEB-1 β-lactamase. (ii) The second phenotype showed resistance to amino-, carboxy-, and ureido-penicillins as well as to cephalothin, with a slight synergy between piperacillin and clavulanic acid that indicated the presence of an oxacillinase. (iii) The third phenotype was consistent with expression of a cephalosporinase, since it showed resistance to amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, and cephalothin and reduced susceptibility to cefuroxime.

The smallest recombinant plasmid for strains expressing each resistance profile was retained for further analysis. The plasmids were designated (i) p10.2-Veb, (ii) p10.2-Oxa, and (iii) p10.2-Ceph and contained a 4.5-kb PstI insert, a 4.6-kb BamHI insert, and a 9.3-kb HindIII insert, respectively.

IEF analysis.

IEF analysis with E. coli DH10B harboring p10.2-Veb, p10.2-Ceph, and p10.2-Oxa showed that each isolate expressed one β-lactamase with a pI value of 7.4 (consistent with the presence of VEB-1 [18]), 8.6 (consistent with AmpC from P. aeruginosa [11]), or 8.5 (a third β-lactamase expressed by p10.2-Oxa [data not shown]). The same pI values, 7.4, 8.5, and 8.6, were observed with the β-lactamase extract from P. aeruginosa 10.2 (data not shown).

Genetic locations of β-lactamase genes.

No plasmid DNA was detected in P. aeruginosa 10.2, despite repeated extraction attempts (15). Transfer of the β-lactam resistance markers from P. aeruginosa 10.2 to rifampin-resistant E. coli C600 and P. aeruginosa PU21 by mating-out experiments and electroporation of E. coli DH10B cells with the extracted DNA failed. Thus, the genetic support for the locations of the β-lactamase genes indicated that they are likely chromosomal.

Characterization of blaVEB-1-like gene and its genetic environment.

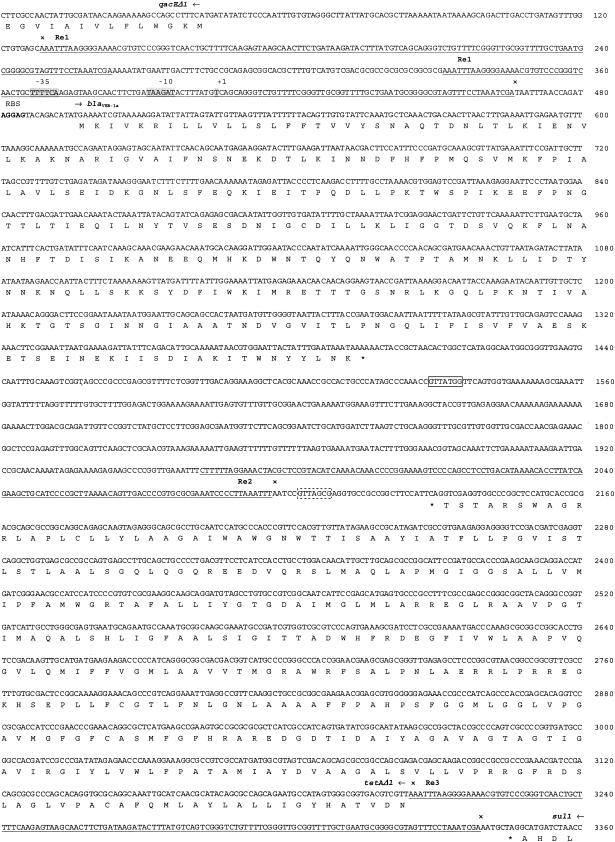

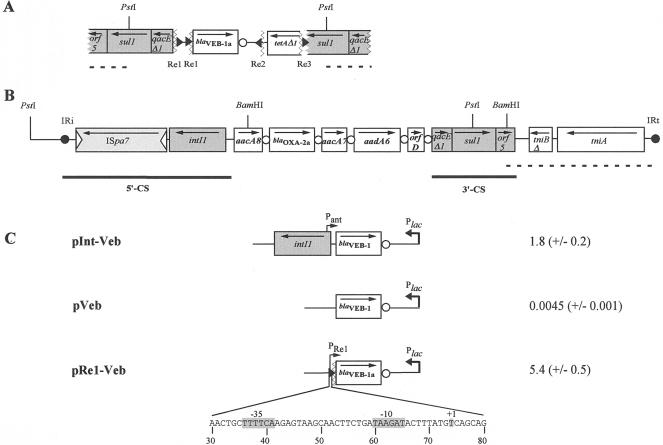

The sequence of the blaVEB-1-like gene from p10.2-Veb differed by 1 bp from that of the blaVEB-1 gene (26). This nucleotide substitution led to an amino acid change (I18V) in the putative leader peptide sequence, resulting in the VEB-1a enzyme that had been reported from a P. aeruginosa isolate in Kuwait (27). Sequence analysis of both sides of the blaVEB-1a gene revealed an atypical genetic environment. Whereas the blaVEB-1a gene was followed by a 59-base element (59-be) that shared 100% nucleotide sequence identity with that previously described for blaVEB-1 gene cassettes (11, 12, 18, 19), it was not preceded by the typical sequence for the recombination core site (Fig. 1) (28). This blaVEB-1a gene cassette was truncated at its left-hand side just before the cassette-specific ribosomal binding site, which was still present (Fig. 1 and 2A). Further upstream of blaVEB-1a a qacEΔ1 gene followed by a sul1 gene, both in the opposite orientations compared to that in blaVEB-1a, were found. The recombination core site of qacEΔ1 that is usually present at the beginning of a 3′ conserved sequence (3′-CS) region was absent due to truncation (Fig. 1 and 2A). Analysis of the sequence between the beginning of the truncated blaVEB-1a gene cassette and 3′-CS region revealed the presence of two identical 135-bp sequences in direct orientation, named Re1. This Re sequence did not share any sequence identity with any known DNA sequences available in the GenBank database. Thus, the blaVEB-1a gene cassette and the 3′-CS region were truncated and separated by a 336-bp DNA stretch that contained identical 135-bp DNA sequences at each end (Fig. 1 and 2A).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the blaVEB-1a genetic environment. Arrows indicate the transcriptional orientation of the gene. The deduced amino acid sequences of the genes are designated in single-letter code below the nucleotide sequence. The ribosomal binding site (RBS) of blaVEB-1a is in boldface, and the stop codons are shown by asterisks. The core and inverse core sites are indicated by boxes and dashed boxes, respectively. The Res are underlined, and the breakpoints are indicated by multiplication signs. Within Re1, the −10 and −35 promoter sequences of PRe1 as well as the +1 transcriptional initiation site are shown by shaded boxes.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of the constructs used in the study and of the blaVEB-1a and blaOXA-2-a environments found in P. aeruginosa 10.2. (A) The breakpoints and the Res in the blaVEB-1a environment are designated by broken lines and black triangles, respectively. (B) The ISpa7 inverted repeats are indicated by empty triangles; the terminal IRi and inverted repeat right (IRt) sequences are shown by black circles. The coding regions are shown as boxes, with arrows indicating the orientations of transcription and white circles indicating the 59-be. The restriction sites used for cloning are indicated. Boldface dashed lines indicate regions that were identified by PCR (the sequences of the primers used are available upon request). (C) Constructs pInt-Veb (2), pVeb (2), and pRe1-Veb (this study) were used for promoter strength and studies of the specific activities of the β-lactamases. The blaVEB-1 genes were inserted in an orientation opposite that of Plac, thus removing any contribution of this promoter to β-lactamase expression. Promoters Plac, PRe1, and Pant are indicated by broken arrows. The −10 and −35 promoter sequences of PRe1 as well as the +1 transcriptional initiation site are indicated by shaded boxes. The numbering is according to the 135-bp Re1 sequence. β-Lactamase specific activities (in units per milligram of protein) obtained with cefuroxime as the substrate are indicated to the right of the representation of each construct. Standard deviations calculated from five independent cultures are indicated in parentheses.

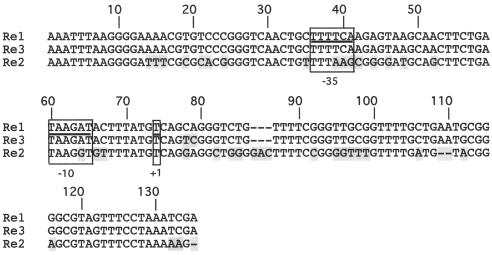

Sequencing of the region located downstream of the blaVEB-1a gene cassette revealed another gene cassette that was truncated at both ends. This gene cassette was made up of a part of a tetracycline resistance gene (tetA), named tetAΔ1, and part of its 59-be, which contained the inverse core site (Fig. 1 and 2A). The blaVEB-1a and tetAΔ1 gene cassettes were in opposite orientations and were separated by a 566-bp DNA sequence that did not contain any open reading frames (ORFs). Surprisingly, analysis of the sequences that immediately followed the breakpoints located on each side of the tetAΔ1 gene cassette identified two 135-bp DNA stretches in opposite orientations (Fig. 1 and 2A). These DNA sequences, named Re2 and Re3, respectively, shared 71 and 98% nucleotide identities with the Re1 sequence, respectively (Fig. 3). A second partial 3′-CS region containing a sul1 gene was also present at the outermost right hand (Fig. 1 and 2A).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the sequences of Res Re1, Re2, and Re3. Dashes indicate gaps introduced to optimize alignment, and the shaded boxes indicate different nucleotides. The promoter sequences of the PRe1 promoter that was characterized in this study are underlined. The −10 and −35 promoter regions in the Re sequences that are identical or related to PRe1 as well as the +1 transcriptional initiation site are boxed. Nucleotide numbering (nucleotides 1 to 135) is according to that of the Re1 sequence.

The presence of two truncated 3′-CSs has already been described in In34 by Partridge and Hall (23). The central region of In34 contained an ORF (orf513), designated conserved region 1 (CR1), and an antibiotic resistance gene (dfrA10) that may have been acquired by homologous recombination, generating two truncated 3′-CSs, called 3′-CS1 and 3′-CS2, one on each side (23). However, in In34, no Re-like sequences had been characterized between the 3′-CS1 and 3′-CS2, and no CR-like sequences were found in the vicinity of the blaVEB-1a gene in P. aeruginosa 10.2.

Characterization of other β-lactamase genes and their genetic environments.

Sequence analysis of inserts of recombinant plasmids p10.2-Oxa, p10.2-Oxa2 (a recombinant plasmid with a 10-kb PstI insert), and p10.2-Ceph was performed. Plasmid p10.2-Oxa2 contained five gene cassettes that were inserted into a class 1 integron named In78 (Fig. 2B): (i) aacA8, which codes for a protein sharing 85% amino acid identity with 6′-N-aminoglycoside acetyltransferase Ib; (ii) blaOXA-2a, which encodes a class D β-lactamase sharing 99% amino acid identity with OXA-2 (pI 8.5), with the amino acid change occurring in the putative leader peptide sequence (1, 9); (iii) aacA7, which encodes another 6′-N-aminoglycoside acetyltransferase type I; (iv) aadA6, which encodes an aminoglycoside adenylyltransferase (20); and (v) orfD, an ORF of unknown function. At the left hand, the 5′-CS of In78 was bounded by a 25-bp inverted repeat left (IRi) sequence identical to that associated with other integrons (13). However, the nucleotide sequence flanking IRi was different from those of other known integrons, and no similarity with sequences available in the GenBank database was found. Moreover, the recently identified IS ISpa7 of 1.6 kb was inserted within the 5′-CS region upstream of the integrase gene, as found in In70.2 (GenBank accession number AJ505012; M. L. Riccio, unpublished data) (Fig. 2B), indicating a possible spread of the ISpa7 sequence in P. aeruginosa. The 3′-CS of In78 contained a truncated tni module with no ISs in the 3′-CS-tniBΔ junction (Fig. 2B). Therefore, In78 is another member of the group of class 1 integrons associated with a defective transposon originating from Tn402-like elements and shares the closest ancestry with In70 and In70.2, which are members of the In0-In2 lineage (3, 29). PCR experiments with combinations of primers specific for the environments from blaVEB-1a and blaOXA-2a were attempted; however, no PCR product was obtained, which suggests that these genes are not located next to each other.

Finally, plasmid p10.2-Ceph contained a 1.2-kb ORF coding for a β-lactamase that shared 98% amino acid sequence identity with the naturally occurring AmpC-type cephalosporinase from P. aeruginosa reference strain PAO1.

Control of blaVEB-1a gene expression.

blaVEB-1 gene expression in P. aeruginosa has been shown to be driven either by the Pant promoter, located in the 5′-CS, or by the Pant promoter together with the Pout promoter located on IS1999 (2); IS1999 is mostly located upstream of blaVEB-1 in P. aeruginosa. The lack of a 5′-CS region upstream of blaVEB-1a in P. aeruginosa 10.2 and the lack of IS1999 raised the question of the means by which blaVEB-1a is expressed. In order to determine whether the Res were capable of driving blaVEB-1a gene expression, recombinant plasmid pRe1-Veb was constructed (Fig. 2C). Measurement of the specific β-lactamase activities of culture extracts of E. coli DH10B(pRe1-Veb) indicated that Re1 likely contained a promoter responsible for blaVEB-1a gene expression. Comparison of the specific activities of the β-lactamase extracts from E. coli DH10B(pRe1-Veb) and E. coli DH10B(pInt-Veb) (Fig. 2C) (2) showed that the Re1 promoter was threefold stronger than the Pant promoter (−35 [TGGACA] and −10 [TAAGCT]) located in the 5′-CSs of class 1 integrons (Fig. 2C). In contrast, pVeb (Fig. 2C) (2), which lacks any promoter sequence, did not provide detectable β-lactamase activity, suggesting that the activities measured with pRe1-Veb were not the result of the activities of nonspecific promoters located somewhere in the cloning vector. The strength of the Re1 promoter and its in vivo effect were confirmed by the MIC results. Indeed, the MICs of most β-lactams for E. coli DH10B(pRe1-Veb) were two- to threefold higher than those for E. coli DH10B(pInt-Veb) (Table 1). By using 5′RACE, PRe1, the promoter located on Re1, was precisely mapped in P. aeruginosa 10.2. Transcription initiation occurred at a thymidine (nucleotide position 405; Fig. 1). Upstream of base pair 405, a −35 promoter region (TTTTCA) separated by 18 bp from a −10 promoter region (TAAGAT) was found. This promoter sequence is also present in the first Re1 and Re3, whereas Re2 contained a related sequence (Fig. 2A and 3). It is likely that a second PRe1 located in the other Re1 sequence may also contribute to blaVEB-1a gene expression in P. aeruginosa 10.2; however it was not evidenced under our experimental conditions with 5′RACE (data not shown).

Conclusion.

This is the first report describing a blaVEB-1-like gene in a P. aeruginosa clinical isolate from the Indian subcontinent and thus further underlined its spread in Asia. In addition, this report indicated that a blaVEB-1-like gene may be located outside a class 1 integron structure. From a more general point of view, this work indicated that integrons may also constitute a reservoir for the spread of antibiotic resistance genes that may be located and expressed either inside or outside an integron structure. The presence of four 135-bp Re sequences surrounding this blaVEB-1a gene was very peculiar. The question of the origins of these Res and their functions in the mobilization of blaVEB-1a remain to be determined. These sequences might play a role in homologous recombination events. Finally, we have shown that these sequences carry active promoters for blaVEB-1a gene expression, which also seems to be a novel feature for expression of antibiotic resistance genes.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the Ministère de la Recherche (grant UPRES-EA 3539), Université Paris XI, Paris, France, and the European Community (6th PCRD, LSHM-CT-2003-503-335).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler, R. P. 1980. The structure of beta-lactamases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 289:321-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubert, D., T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 2003. IS1999 increases expression of the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase VEB-1 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 185:5314-5319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, H. J., H. W. Stokes, and R. M. Hall. 1996. The integrons In0, In2, and In5 are defective transposon derivatives. J. Bacteriol. 178:4429-4437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bush, K., G. A. Jacoby, and A. A. Medeiros. 1995. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1211-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao, V., T. Lambert, D. Q. Nhu, H. K. Loan, N. K. Hoang, G. Arlet, and P. Courvalin. 2002. Distribution of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in Vietnam. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3739-3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chanawong, A., F. H. M'Zali, J. Heritage, A. Lulitanond, and P. M. Hawkey. 2001. SHV-12, SHV-5, SHV-2a and VEB-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in gram-negative bacteria isolated in a university hospital in Thailand. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48:839-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, H. Y., M. Yuan, and D. M. Livermore. 1995. Mechanisms of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics amongst Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates collected in the UK in 1993. J. Med. Microbiol. 43:300-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collis, C. M., and R. M. Hall. 1995. Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in the integrated cassettes of integrons. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:155-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dale, J. W., D. Godwin, D. Mossakowska, P. Stephenson, and S. Wall. 1985. Sequence of the OXA2 beta-lactamase: comparison with other penicillin-reactive enzymes. FEBS Lett. 191:39-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Champs, C., L. Poirel, R. Bonnet, D. Sirot, C. Chanal, J. Sirot, and P. Nordmann. 2002. Prospective survey of beta-lactamases produced by ceftazidime-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated in a French hospital in 2000. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:3031-3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Girlich, D., T. Naas, A. Leelaporn, L. Poirel, M. Fennewald, and P. Nordmann. 2002. Nosocomial spread of the integron-located veb-1-like cassette encoding an extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Thailand. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:603-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girlich, D., L. Poirel, A. Leelaporn, A. Karim, C. Tribuddharat, M. Fennewald, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of the integron-located VEB-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase in nosocomial enterobacterial isolates in Bangkok, Thailand. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:175-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hall, R. M., H. J. Brown, D. E. Brookes, and H. W. Stokes. 1994. Integrons found in different locations have identical 5′ ends but variable 3′ ends. J. Bacteriol. 176:6286-6294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karim, A., L. Poirel, S. Nagarajan, and P. Nordmann. 2001. Plasmid-mediated extended-spectrum β-lactamase (CTX-M-3 like) from India and gene association with insertion sequence ISEcp1. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 201:237-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kieser, T. 1984. Factors affecting the isolation of cccDNA from Streptomyces lividans and Escherichia coli. Plasmid 12:19-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovach, M. E., R. W. Phillips, P. H. Elzer, R. M. Roop II, and K. M. Peterson. 1994. PBBR1MCS: a broad-host-range cloning vector. BioTechniques 16:800-802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naas, T., D. Aubert, N. Fortineau, and P. Nordmann. 2002. Cloning and sequencing of the beta-lactamase gene and surrounding DNA sequences of Citrobacter braakii, Citrobacter murliniae, Citrobacter werkmanii, Escherichia fergusonii and Enterobacter cancerogenus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 215:81-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naas, T., F. Benaoudia, S. Massuard, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Integron-located VEB-1 extended-spectrum β-lactamase gene in a Proteus mirabilis clinical isolate from Vietnam. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:703-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naas, T., L. Poirel, A. Karim, and P. Nordmann. 1999. Molecular characterization of In50, a class 1 integron encoding the gene for the extended-spectrum β-lactamase VEB-1 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 176:411-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naas, T., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 1999. Molecular characterisation of In51, a class 1 integron containing a novel aminoglycoside adenylyltransferase gene cassette, aadA6, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1489:445-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naas, T., W. Sougakoff, A. Casetta, and P. Nordmann. 1998. Molecular characterization of OXA-20, a novel class D β-lactamase, and its integron from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2074-2083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 23.Partridge, S. R., and R. M. Hall. 2003. In34, a complex In5 family class 1 integron containing orf513 and dfrA10. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:342-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philippon, L. N., T. Naas, A.-T. Bouthors, V. Barakett, and P. Nordmann. 1997. OXA-18, a class D clavulanic acid-inhibited extended-spectrum β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2188-2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poirel, L., O. Menuteau, N. Agoli, C. Cattoen, and P. Nordmann. 2003. Outbreak of extended-spectrum β-lactamase VEB-1-producing isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii in a French hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3542-3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poirel, L., T. Naas, M. Guibert, E. B. Chaibi, R. Labia, and P. Nordmann. 1999. Molecular and biochemical characterization of VEB-1, a novel class A extended-spectrum β-lactamase encoded by an Escherichia coli integron gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:573-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poirel, L., V. O. Rotimi, E. M. Mokaddas, A. Karim, and P. Nordmann. 2001. VEB-1-like extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Kuwait. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:468-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Recchia, G. D., and R. M. Hall. 1995. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile elements. Microbiology 141:3015-3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riccio, M. L., L. Pallecchi, R. Fontana, and G. M. Rossolini. 2001. In70 of plasmid pAX22, a blaVIM-1-containing integron carrying a new amino glycoside phosphotransferase gene cassette. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1249-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Steers, E., E. I. Foltz, B. S. Graves, and J. Riden. 1959. An inocula replicating apparatus for routine testing of bacterial susceptibility to antibiotics. Antibiot. Chemother. 9:307-311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tribuddharat, C., and M. Fennewald. 1999. Integron-mediated rifampin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:960-962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vahaboglu, H., R. Ozturk, G. Aygun, F. Coskunkan, A. Yaman, A. Kaygusuz, H. Leblebicioglu, I. Balik, K. Aydin, and M. Otkun. 1997. Widespread detection of PER-1-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases among nosocomial Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Turkey: a nationwide multicenter study. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2265-2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vivian, A. 1994. Plasmid expansion? Microbiology 140:2188-2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weldhagen, G. F., L. Poirel, and P. Nordmann. 2003. Ambler class A extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: novel developments and clinical impact. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2385-2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]