Abstract

BACKGROUND: An efficient team and a good organizational climate not only improve employee health but also the health and safety of the patients. Building up trust, a good organizational climate and a healthy workplace requires effective communication processes. In Sweden, workplace meetings as settings for communication processes are regulated by a collective labor agreement. However, little is known about how these meetings are organized in which communication processes can be strengthened.

OBJECTIVE: The aim of this study was to explore communication processes during workplace meetings in a Swedish healthcare organization.

METHODS: A qualitatively driven, mixed methods design was used with data collected by observations, interviews, focus group interviews and mirroring feedback seminars. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and conventional content analysis.

RESULTS: The communication flow and the organization of the observed meetings varied in terms of physical setting, frequency, time allocated and duration. The topics for the workplace meetings were mainly functional with a focus on clinical processes. Overall, the meetings were viewed not only as an opportunity to communicate information top down but also a means by which employees could influence decision-making and development at the workplace.

CONCLUSIONS: Workplace meetings have very distinct health-promoting value. It emerged that information and the opportunity to influence decisions related to workplace development are important to the workers. These aspects also affect the outcome of the care provided.

Keywords: Meeting, dialogue, workplace health promotion, qualitative method, hospital

1. Introduction

An efficient team and a good organizational climate not only improve employee health but also the health and safety of the patients [1]. Building up trust, and organizational climate and a healthy workplace [2] requires effective communication processes. In Sweden, workplace meetings as an opportunity for communication are regulated by a collective labor agreement. However, little is known about how these meetings are organized in which communication processes can be strengthened.

Communication has been described as a linear process, where a message passes from a sender through a medium to a receiver [3]. Communication can also be seen as a process that occurs between two or more people and where the aim is to share and exchange information in order to solve problems and sometimes to explore new ways of working [4]. In this sense, a communication process seems to be more than merely a way of conveying information. It includes a series of complex, creative processes where the content is constructed and interpreted through interaction between people at the workplace.

An open communication climate is characterized by a dialogue that requires unrestricted, honest and mutual interaction [5] for people to understand each other better, to promote tolerance and to minimize conflicts. An open communication climate is essential to achieve a better work environment [6] and it can therefore be regarded as health-promoting as it strengthens conditions for employee to exert influence and became involved [7].

In organizations, communication flows vertically and horizontally in the hierarchy [8] or it is free-flowing, with all the members of the organization communicating with each other [9]. An upward communication flow is the process of conveying information from the lower levels to the upper levels in the organization. This gives the employees the opportunity to speak out and provide critical feedback that could be important in the decision-making process [10]. Nevertheless, positive information is more likely to flow upwards than negative information, which could result in potential problems at lower levels in the organization failing to reach top management [11] thus impacting negatively on the decision-making processes.

In Sweden, formal workplace meetings are regulated by a collective labor agreement that was established to encourage communication [12]. The structure and format of these meetings have been assessed in several settings although to date the outcome in terms of the communication processes that are in place in healthcare organizations has not been studied. The aim of this study was to explore communication processes in workplace meetings in a Swedish healthcare organization. Specific research questions were: How were the workplace meetings organized? Which communication processes (topics and communication flow) prevailed during the workplace meetings? How did employees and managers view workplace meetings?

2. Methods

2.1. Design

The present study is part of a larger research project in which the overall aim is to investigate the process underlying the implementation of a workplace health promotion project in a healthcare organization. The present study focuses on the health-promoting value of communication processes in formal workplace meetings. The design of the present study is exploratory and a qualitatively driven mixed methods approach is applied [13]. Data was collected by observations, interviews, mirroring feedback seminars and focus group interviews.

2.2. Setting and study sample

This study was carried out at a Swedish hospital with approximately 4,500 employees. The organization is multi-professional and the largest professional groups are nurses (n = 1,700) and nursing assistants (n = 1,000). The hospital has around 140 wards where formal workplace meetings are mandatory under the collective labor agreement.

2.3. Data collection

2.3.1. Observations

A strategic selection of medical and surgical wards was used. The managers were contacted by the HR department, which provided them with information about the study and invited them to participate. Nine ward managers (seven females and two males) were enrolled from nine different wards, varying in terms of clinical tasks and location. The length, frequency and number of participants in workplace meetings are shown in Table 3. The observations were made between November 2010 and February 2011. The observer (CB) did not participate in the meetings. The observations were both semi-structured, using a predetermined protocol based on the labor agreement, and unstructured using field notes. The total observation time was approximately eighthours.

Table 3.

Organization of the observed workplace meeting (WM)

| WM1 | WM2 | WM3 | WM4 | WM5 | WM6 | WM7 | WM8 | WM9 | |

| Clinical setting | Medicine | Surgery | Medicine | Medicine | Medicine | Medicine | Medicine | Surgery | Medicine |

| Venue for WM | Break room | Break room | Break room | Break room | Conference room | Conference room | Office | Break room | Break room |

| Time of day | Afternoon | Afternoon | Afternoon | Afternoon | Afternoon | Afternoon | Morning | Afternoon | Afternoon |

| Scheduled duration (hours) | 01:15 | 0:45 | 01:30 | 00:30 | 01:00 | 01:00 | 01:00 | 02:30 | 00:30 |

| Frequency | Once a month | Every second week | Once a month | Once a week | Once amonth | Once a week | Once a week | Once a month | Once a month |

| Number of participants (percentage of all employees) | 9 (18%) | 23 (38%) | 15 (50%) | 15 (30%) | 12 (30–34%) | 9 (36%) | 3 (–) | 11 (29%) | 11 (14%) |

2.3.2. Interviews with managers

A semi-structured interview guide was used and notes were taken from interviews conducted with each of the ward managers responsible for the observed meetings in order to obtain information about the way the meetings were organized.

2.3.3. Focus group interviews with employees

Ward managers from 44 wards were asked to invite or select one to three employees to participate in focus group interviews dealing with the employees’ views on workplace meetings. It was not a requirement that they should have participated in the observed workplace meeting. The total sample consisted of eight groups with 50 employees from 44 different wards and varying in terms of profession, length of employment, sex and age (Table 1). The focus group interviews took place in conference rooms at the hospital between November 2011 and January 2012. Each interview lasted approximately one hour and a semi-structured questionnaire with open-ended questions was used. One of the researchers (CB/KS) conducted the focus group interviews and a research assistant took field notes to supplement the audio recordings. The recordings were transcribed verbatim by a person experienced in this type ofwork.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample for the focus group interviews

| Focus group | Participants | Profession | Length of | Sex | Age |

| (n) | employment (years) | Women/Men | |||

| 1 | 5 | Nurses | 6–42 | 5/0 | 30–62 |

| 2 | 8 | Assistant nurses | 10–34 | 8/0 | 41–55 |

| 3 | 7 | Nurses | 3.5–37 | 7/0 | 35–58 |

| 4 | 4 | Nurses | 7–35 | 4/0 | 35–60 |

| 5 | 5 | Assistant nurses | 3–38 | 4/1 | 38–59 |

| 6 | 6 | Nurses | 5–31 | 4/2 | 28–57 |

| 7 | 8 | Assistant nurses | 5–38 | 7/1 | 29–59 |

| 8 | 7 | Nurses | 1–36 | 6/1 | 28–59 |

| Total: 8 | Total: 50 | Total: 45/5 |

2.3.4. Mirroring feedback seminars

A seminar was organized with the participating ward managers where preliminary findings from the observations and interviews were presented in order to ascertain the views held by the managers. Seven managers participated in the seminar, during which they verified the findings and expended on their opinions about workplace meetings.

A similar mirroring feedback seminar was arranged for employees who had participated in the focus group interviews. Twenty employees attended the seminar, during which they verified the findings and provided additional data that were helpful in the analysis.

2.4. Data analysis

2.4.1. Quantitative data

The observation scheme was used to collect data and place it into predefined categories (Table 2). The registered time in minutes for each of the predefined categories is shown in the Results section as a fraction of the total time taken for the observedmeetings.

Table 2.

The predefined categories used in the semi-structured observation scheme

| Topics | Communication flow |

| Physical work environment | One-way communication flow downwards |

| Psychosocial work environment | One-way communication flow upwards |

| Structural organizational changes | Two-way/multi-way communication flow |

| Economy | |

| Clinical work | |

| Quality and organizational development | |

| Planning and organization of workplace meetings | |

| Employment, staffing, schedules | |

| Health and illness among employees | |

| Competence development | |

| Cooperation | |

| Technology |

The observation scheme had not been used for observations of meetings before but similar observation schemes with other predefined categories have been used in similar studies dealing with managers’ use of time [14, 15].

When the first three observations were completed, the relevance of the predefined categories was validated by the researchers (CB, LD, KS). This procedure resulted in a high level of agreement regarding relevance and the addition of a new category (planning and organization of workplace meetings).

After all the observations had been registered, the data collection process was validated by each researcher separately. They checked the categorization and then compared the results with the other researchers, which led to a high level of agreement within the research team.

2.4.2. Qualitative data

The qualitative data from the observations, interviews, focus group interviews and mirroring feedback seminars were analyzed stepwise using conventional content analysis [16]. Firstly, the open comments in the semi-structured observation scheme were analyzed to identify the content. Secondly, the field notes from the observations, individual interviews and mirroring feedback seminars were analyzed inductively through a process of coding and categorizing in line with conventional content analysis [16]. Thirdly, the transcribed material from the focus group interviews was read through, after which significant comments on the views of employees about workplace meetings were selected, coded and organized into categories.

2.5. Ethical aspects

The data in this study were collected, analyzed and presented at group level and it is not possible to trace data to a specific individual. Informed consent, including secrecy and voluntary participation, was applied. The overall research project was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg, Sweden (Ref. No. 433-10).

3. Results

The empirical findings are presented stepwise. The results from the observations and interviews with managers concerning the organization of workplace meetings and communication processes are presented first. These are followed by a presentation of the results from the interviews, focus group interviews and mirroring feedback seminars relating to the views of managers and employees.

3.1. Organization of workplace meetings

The organization of workplace meetings varied between the wards, thus making it possible to assess the significance of the format. Meetings were held in break rooms or conference rooms or in an office. The physical arrangement varied between the meetings. One meeting, for example, was held in a break room where some of the employees and the manager had their backs to each other. At other meetings the participants sat face to face.

It was usually the manager who chaired the meeting and who was responsible for the invitation and the agenda. Before each meeting, the employees had an opportunity to propose topics for the agenda. The duration of the meetings varied from half an hour to two and a half hours. The frequency varied from once a week to once a month. The number of participants varied between 3 and 23, representing between 14% and 50% of the employees eligible, i.e. those working in the wards (Table 3).

3.2. The communication process

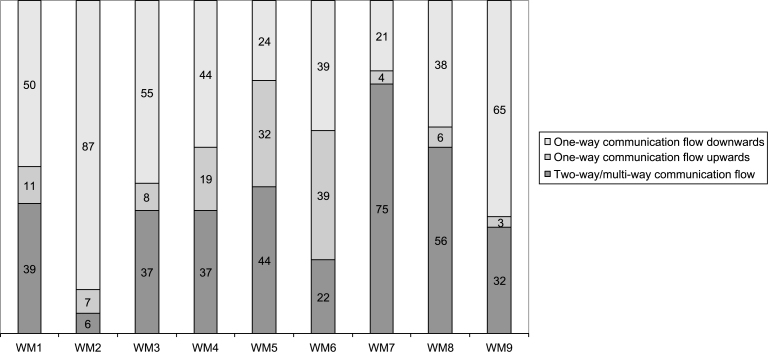

The communication flow was assessed as a vertical, one-way flow either downwards or upwards, or as a horizontal, two-way or multi-way communication flow. The one-way, downward communication flow with information from the managers took up almost half the time (46%) and the upward communication flow with information from the employees took up 13% of the time. Vertical and horizontal dialogue and discussions between employees and between managers and employees took up 41% of the time. There was considerable variation: one meeting was dominated by a downward communication flow that took up 87% of the time and another meeting was dominated by a two-way or multi-way communication flow that took up 75% of the time (Fig. 1).

Fig.1.

Variation in communication flow at the workplace meetings.

The meetings had a functional approach with half of the meeting time (49%) focusing on Clinical work dealing with guidelines, routines, tools and patient care. The communication flow during this major topic was for half of the time a one-way, downward communication flow (51%), for 16% of the time it was a one-way, upward communication flow. For 33% of the time it was a two-way or multi-way communication flow.

The structural themes of Physical work environment, Psychosocial work environment and Health and illness among employees took up 16% of the time. The topic Physical work environment (7%) included occupational health and safety inspection, a fire protection review and physical conditions affecting the work environment. Psychosocial work environment (6%) included social activities, the coffee fund and the administrative burden. Health and illness among employees (3%) dealt with matters related to diseases, influenza vaccination, smoke cessation and wellness programs.

Staff-related topics, such as employment, staffing and schedules, took up 15% of the observed time. Technology (6%) was about cell phone use and computer-related information. Cooperation (6%) dealt with collaboration between wards and/or between professions. Structural organizational changes (2%) dealt with the rebuilding and merging of wards. Economy (2%) dealt with the cost of equipment and laundry and budget situations.Quality and organizational development (2%), including planning for Lean Processes and Balanced Scorecards, were only addressed occasionally. Planning and organization of workplace meetings (1%) and Competence development (1%), which addressed educational opportunities for employees and feedback from courses taken, were topics on which only a small amount of time was spent (Table 4).

Table 4.

Duration and proportion of time devoted to the various topics

| Topics | Duration | Proportion |

| (hours) | of time | |

| Clinical work | 03 : 49 | 49% |

| Employment, staffing, schedules | 01 : 08 | 15% |

| Physical work environment | 00 : 35 | 7% |

| Technology | 00 : 30 | 6% |

| Cooperation | 00 : 28 | 6% |

| Psychosocial work environment | 00 : 26 | 6% |

| Health and illness among employees | 00 : 16 | 3% |

| Structural organizational changes | 00 : 11 | 2% |

| Quality and organizational development | 00 : 09 | 2% |

| Economy | 00 : 09 | 2% |

| Planning and organization of workplace meeting | 00 : 07 | 1% |

| Competence development | 00 : 06 | 1% |

| Total time: 07 : 54 |

3.3. The views of managers and employees about workplace meetings

Managers and employees agreed that the aim of a workplace meeting is to offer a forum for communication of information, employee influence and decision-making. Employees also highlighted workplace meetings as an opportunity to share knowledge and to develop competence. There were different opportunities and motives for attending a workplace meeting.

3.3.1. Communication of information

For the managers, workplace meetings are a way of disseminating information. A possible strategy for informing the employees was to dedicate one meeting solely to information and another to discussions on predetermined topics. Further information strategies were also employed, such as information letters and emails. A common view among managers was that it was difficult to prioritize within the flow of information communicated from above.

The employees regarded information that dealt with their own ward and/or profession as relevant. Despite the amount of information communicated downwards, the employees requested more specific information about topics discussed at top management meetings and how decisions made at top management level would affect their particular working situation, such as management turnover and cutback demands:

It would be interesting to hear more about what has been discussed at top management meetings about my ward and not just be informed about decisions. It would be useful to know how they discuss where possible cost savings could be made and what their thoughts are about the savings proposal. [...] What should be cut? Are there any thoughts regarding care administration or about us, the nursing staff?

3.3.2. Opportunity for employee influence and decision-making

Both managers and employees regarded the workplace meeting as a decision-making forum. From the employees’ point of view, decision-making and the documentation of decisions seemed to be important ways of preventing issues from being pushed ahead, thus validating the decisions.

And then the decision will be made. Not just talk. The manager is very good at summarizing what we came up with and ensuring that everything is written down. [...] If we haven’t dealt with something, the matter in question is taken up at the next meeting. That way it won’t be missed.

The employees expressed the view that they had the opportunity to exert an influence and although they succeeded in doing so at workplace meetings in matters related directly to patient care this was not quite the case with regard to organizational issues. Part of each meeting was dedicated to the specific interests of the employees although this particular session was organized differently. At some of the workplace meetings there was a round table discussion where each employee was given an opportunity to speak:

We have workplace meetings every week [...] during which we have a round table discussion so that all of us can have a say, bring up something we feel is important, deal with something from our area of responsibility or present information that we want to share. It works.

Other workplace meetings had a specific item on the agenda that gave employees the opportunity to speak. This took place either at the beginning or at the end of the meeting. If this item was at the end, there could be a lack of time for every employee to speak:

[...] it is an information meeting. There are no exchanges regarding major problems, if you understand me. For us, the employees, there is time for questions at the end. First, the manager announces what information needs to be provided. Then it all depends on how much time we have because the reception opens at 8.50 and we need to be finished by then.

3.3.3. Sharing knowledge and development of competence

A workplace meeting is also a means of developing competence, which is a function specifically requested by the employees. One approach is to share information and experiences from courses and seminars that people have attended. Another way is to bring in professionals from within or outside the organization to talk. Employees from other wards could also be invited to the meeting to inform and enlighten their colleagues.

3.3.4. Attendance opportunities and motives

As mentioned above, between 14% and 50% of the employees attended the observed workplace meetings. Two major factors prevented attendance: working with patients and work schedules. The workplace meetings were sometimes seen as disrupting the work with patients and consequently attendance was not always prioritized by the employees. Some of the meetings took place in inpatient wards and employees involved in the active care of patients came and went during the meeting. The managers pointed out that this is a normal phenomenon in wards of this kind.

Due to work schedules that covered activities at all times of the day and night, and which sometimes extended across different wards, it was generally a problem for all the employees to participate in the workplace meetings at the same time. To alleviate this, the meetings were mostly scheduled for the afternoons to enable employees on both the day and night shifts to attend.

4. Discussion

One important health-promoting action is open communication in a culture of free speech and discussion [6, 7]. In this study, vertical and horizontal communication in a large healthcare organization was evaluated from a European perspective, i.e. compulsory formal workplace meetings. Their mandatory nature is based on binding labor agreements [12] although the format and local realization are decided by the management.

The results from this study showed that although formal workplace meetings are mainly an opportunity for downward, one-way communication or information, they also permitted upward, two-way and multi-way communication where employees have the opportunity to influence the decisions that are being made. It was particularly clear that functional influence was associated with the everyday work of the employees. This was not only expressed by the employees but was also observed. The results are thus in line with the aims behind a collective labor agreement, which recognizes workplace meetings as an essential part of the concept of a healthy workplace [12].

Variations in the format and implementation of the formal requirements were observed, which made it possible to conclude that the physical arrangements, duration, agendas and local culture had an impact on the experienced value of the workplace meetings. Observations made by the research team supported the claim that multi-way communication in a small or medium-sized group worked well.

The results highlight certain factors that may hinder the communication process. Firstly, the number of participants at the meeting may affect the upward communication flow. Meetings with large numbers of employees may restrict the opportunity for employees to speak. Secondly, there was a lack of techniques for enhancing dialogue. No technique was apparently used to stimulate dialogue during the meetings, such as dividing large groups into smaller groups. Thirdly, there were few dedicated rooms for meetings. Meetings arranged in rooms within the ward could make it possible for more employees to participate as there is a constant flow of patients and the employees need to be present in ways that differ from an outpatient department. However, some of the rooms lacked optimal physical facilities for arranging meetings. An earlier study highlight that a lack of appropriate meeting facilities, such as suitable table arrangements, could impede meeting processes [17] and according to the present study it could impede the communication process. Apart from the meeting facilities, having the right meeting environment would appear to be crucial [18]. A written agenda prepared in advance appears to be associated with perceived effectiveness [17]. An agenda with predetermined topics can be seen both as a constraint, compelling the participants to introduce topics in accordance with what is specified in the agenda, and as a resource that allows the agenda for the meeting to be worked through efficiently [19].

The results from the present study highlight factors that prevent people from attending, such as scheduling and ongoing patient care during the meetings. Earlier studies also highlight the difficulty, particularly for physicians, to attend workplace meetings due to scheduling and operative work [20]. This was related to a feeling of being left on the outside and having limited opportunity to exert an influence through the healthcare organization’s formal decision-making processes [21].

4.1. Methodological considerations

Several data collection methods were used to explore the workplace meeting as a forum for communication. The mixed methods design contributed to descriptive statistics combined with qualitative data and by using this methodological design both managers’ and employees’ views of workplace meetings were highlighted, as was the way in which this forum was used in practice.

To the authors’ knowledge, the present study is one of the first to observe communication processes at workplace meetings by using this semi-structured observation scheme. However, there are limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results and these could be addressed in future scientific observation studies dealing with workplace meetings.

Firstly, in the present study a two-way or multi-way communication flow consists of dialogue, discussion and debate and it may be more important to observe these categories separately. Secondly, one observer may not be sufficient to cover the whole communication process – to study both verbal and non-verbal communication for example – and two observers could be needed to cover each aspect of the communication process. Although there are certain methodological limitations, the present study indicates that the semi-structured observation method modified from studies of managerial work [14, 15] would appear to be relevant for future studies aimed at observing communication processes.

For further studies, workplace meetings within a ward should be studied over time to identify a pattern in the communication flow. Furthermore, interviews should be conducted with both the manager and employees who participated in the observed meeting to obtain their views about the communication processes.

4.2. Conclusions

Formal Swedish workplace meetings seem to offer potential as a setting for vertical as well as horizontal communication in the healthcare organization studied. However, a take-home message is that the outcome of the meetings is sensitive to the physical arrangements, the size of the group, lack of technique to stimulate dialogue and, above all, the culture within the unit. For obvious reasons functional rather than structural discussions dominate the kind of session in a healthcare organization where care of patients is in focus. Nevertheless, the health-promotion value of workplace meetings is very clear. Workers seem to regard information and the potential to influence decisions about the development of the workplace as important. This would also affect the outcome of the care provided.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the AFA insurance company for its financial support. They are also grateful to the managers and employees who participated in the study.

References

- [1]. Wheelan SA, Burchill CN, Tilin F. The link between teamwork and patients’ outcomes in intensive care units. American Journal of Critical Care: An Official Publication, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses 2003;12(6):527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Whitehead D. Workplace health promotion: The role and responsibility of health care managers. Journal of Nursing Management 2006;14(1):59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Shannon CE, Weaver W. The mathematical theory of communication Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Argyris C. Managers, workers, and organizations. Society 1998;35(2):343–6. [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Bokeno RM. Dialogue at work? What it is and isn’t. Development and Learning in Organizations 2007;21(1):9–11. [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Whitelaw S, Baxendale A, Bryce C, MacHardy L, Young I, Witney E. ‘Settings’ based health promotion: A review. Health Promotion International 2001;16(4):339–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Bringsén A, Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G, Troein M. Exploring workplace related health resources from a salutogenic perspective. Results from a focus group study among healthcare workers in Sweden. Work 2012;42(3):403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Bartels J, Peters O, de Jong M, Pruyn A, van der Molen M. Horizontal and vertical communication as determinants of professional and organizational identification. Personnel Review 2010;39(2):210–26. [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Miller K. Organizational communication: Approaches and processes Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Tourish D, Robson P. Critical upward feedback in organisations: Processes, problems and implications for communication management. Journal of Communication Management 2004;8(2):150–67. [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Milliken FJ, Morrison EW, Hewlin PF. An Exploratory Study of Employee Silence: Issues that Employees Don’t Communicate Upward and Why. Journal of Management Studies 2003;40(6):1453–76. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sveriges kommuner och landsting S. FAS 05 Förnyelse – Arbetsmiljö – Samverkan i kommuner, landsting och regioner. 2005.

- [13]. Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches Thousand Oaks, Calif: SAGE; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Arman R, Dellve L, Wikström E, Törnström L. What health care managers do: Applying Mintzberg’s structured observation method. Journal of Nursing Management 2009;17(6):718–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Tengelin E, Arman R, Wikström E, Dellve L. Regulating time commitments in healthcare organizations. Journal of Health Organization and Management 2011;25(5):578–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research 2005;15(9):1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Leach DJ, Rogelberg SG, Warr PB, Burnfield JL. Perceived meeting effectiveness: The role of design characteristics. Journal of Business and Psychology 2009;24(1):65–76. [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Cohen MA, Rogelberg SG, Allen JA, Luong A. Meeting design characteristics and attendee perceptions of staff/team meeting quality. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 2011;15(1):90–104. [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Svennevig J. The agenda as resource for topic introduction in workplace meetings. Discourse Studies 2012;14(1):53–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Bååthe F, Norbäck L. Engaging physicians in organisational improvement work. Journal of Health Organization and Management 2013;27(4):479–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Lindgren Å, Bååthe F, Dellve L. Why risk professional fulfilment: A grounded theory of physician engagement in healthcare development. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 2013;28(2):138–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]