Abstract

Objective:

A small body of evidence supports targeting adolescents who are heavy users of cannabis with brief interventions, yet more research is needed to confirm the effectiveness of these studies. We conducted a secondary analysis of our Peer Network Counseling (PNC) study (Mason et al., 2015), focusing on 46 adolescents of the sample of 119 who reported heavy cannabis use at baseline.

Method:

Urban adolescents (91% African American) presenting for primary health care were randomized to intervention or control conditions and followed for 6 months. We selected cases (n = 46) to analyze based on heavy cannabis use reported at baseline (≥10 times in past month). The ordinal response data (cannabis use) were modeled using a mixed-effects proportional odds model, including fixed effects for treatment, time, and their interaction, and a subject-level random effect.

Results:

In the subsample of adolescents with heavy cannabis use, those assigned to PNC had a 35.9% probability of being abstinent at 6 months, compared with a 13.2% probability in the control condition. Adolescents in the PNC condition had a 16.6% probability of using cannabis 10 or more times per month, compared with a 38.1% probability in the control condition. This differs from results of the full sample (N = 119), where no significant effects on cannabis use were found.

Conclusions:

PNC increased the probability of abstinence and reduced heavy cannabis use. These results provide initial support for PNC as a model for brief treatment with non-treatment seeking adolescents who are heavy users of cannabis.

Cannabis remains the most widely used substance by adolescents, and there is growing evidence of negative effects associated with heavy, sustained, and early use. Heavy and persistent cannabis use has been associated with reduced educational attainment (MacLeod et al., 2004), neuropsychological decline (Meier et al., 2012), lower income, greater welfare dependence, unemployment, and criminal behavior (Brook et al., 2013; Fergusson & Boden, 2008). A recent review implicated adolescent cannabis use with vulnerability to the development of anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, personality disorders, and interpersonal violence (Copeland et al., 2013). Therefore, testing interventions that target heavy cannabis users is particularly important. Addressing this issue among underserved populations is crucial in reducing health disparities.

Approximately 9% of those who try cannabis will develop a disorder, with half of these cases developing within 5 years after the first use (Budney et al., 2007). Of those who develop cannabis use disorder, African Americans have the highest rates of transition from first use to cannabis disorder compared with other subgroups (Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011). African American youth with substance use disorders are less likely to receive specialty care compared with their White and Hispanic counterparts (Alegria et al., 2011). Even when they do engage in treatment, African American youth receive significantly fewer treatment sessions than their White peers (Becker et al., 2012), are more likely to leave treatment prematurely (Austin & Wagner, 2010), and are less likely to complete posttreatment assessment (Becker et al., 2012). Successfully engaging underserved youth in evidence-based treatments can address the gap in the research base about how to access hard-to-reach populations. One approach that may engage youth in treatment is to carefully consider their personal peer networks (close friends).

Peer relationships are known to be important mediators of substance use among adolescents (Black & Chung, 2014; Burk et al., 2012; Mason et al., 2011) and, therefore, are promising targets for interventions. Research supports the clinical effectiveness of targeting adolescent peer network characteristics with brief interventions (Chung et al., 2015). Peer context is a very robust predictor of cannabis use (Pollard et al., 2014); thus, integrating peer networks into cannabis use interventions is warranted.

Motivational interviewing

Research has demonstrated the efficacy of motivational interviewing on reducing substance use (Dennis, 2004; Jensen et al., 2011; Lundahl et al., 2010; VanBuskirk & Wetherell, 2014). Motivational interviewing fits well within pediatric health care settings (Erickson et al., 2005) and is considered an evidenced-based, frontline approach to reducing substance use through increased levels of patient-centered care, shared decision making, and improved clinician-patient relationships (Anstiss, 2009; Rollnick et al., 2008). Brief interventions targeting cannabis have shown favorable results, with single sessions reducing use among pediatric emergency department patients (Bernstein et al., 2009), and primary care patients using screening and brief advice (Harris et al., 2012). A study that compared computer-delivered brief interventions against therapist- delivered brief interventions found that computer-delivered brief interventions reduced cannabis-related consequences (e.g., interpersonal, financial problems), whereas therapist-delivered brief interventions reduced driving under the influence (Walton et al., 2013). However, when the evidence for motivational interviewing is taken together, the results are somewhat mixed. For example, there are concerns about the staying power of motivational interviewing interventions, as effect sizes tend to diminish over time (Smedslund et al., 2011).

A small body of research suggests that motivational interviewing may be particularly beneficial among heavier substance users. Motivational interviewing has been found to be effective among college students who are heavy users of cannabis (McCambridge & Strang, 2004) and heavy drinking college students (Samson & Tanner-Smith, 2015). Adolescents experiencing problematic alcohol use had significantly better outcomes after brief motivational interviewing than their peers who did not evidence alcohol problems (Spirito et al., 2004). We are aware of one study that examined this hypothesis among adolescents considered heavy cannabis users. Using WEED-CHECK, a Dutch translation of the Teen Marijuana Check-Up (Swan et al., 2008), de Gee and colleagues (2014) found that heavier cannabis users at baseline (defined as smoking more than 14 joints per week) had significantly greater reductions in cannabis use than controls, whereas a simple comparison of treatment and control groups showed no differences. These findings support further study of motivational interviewing treatments for adolescents who are heavy users of cannabis.

We conducted an exploratory, secondary analysis of a subsample of adolescents who were heavy users of cannabis, using data from our Peer Network Counseling (PNC) intervention study (Mason et al., 2015). PNC underwent rigorous motivational interviewing fidelity monitoring and testing. The parent study consisted of 119 adolescents determined to be at risk for substance use disorders, who were randomized to PNC versus an attention control condition. Self-reported substance use (abstinence/use) at the 6-month point was the primary outcome. We found PNC to be significantly more effective than attention control in reducing reported offers from peers to use alcohol, but it did not differ significantly from control in reducing self-reported cannabis use for the full randomized sample. Thus, we sought to test PNC with heavy users of cannabis. We examined the treatment effects of PNC in adolescents who used cannabis 10 or more times during the last 30 days, basing this classification on similar research (Cousijn et al., 2012; Pope et al., 2001). We hypothesized that adolescents allocated to PNC would exhibit reduced cannabis use at the 6-month follow-up compared with the control condition.

Method

Procedures and participants

Participants for the study were recruited between April 2013 and February 2014 from an adolescent medicine outpatient clinic at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Medical Center. The VCU Institutional Review Board approved the protocol. Adolescents were screened for substance use with the CRAFFT, a youth substance use screener with six yes/no questions to determine level of substance use risk (Knight et al., 1999). Participants with scores of two or three, indicating at-risk status for substance use disorder, were enrolled in the study; those with higher scores were referred to their physician and provided resource information. Following screening, parental consent, and adolescent assent, adolescents were randomized into either PNC or the attention control condition (a time-matched generic health information session). Participants completed the baseline assessment on a laptop computer and follow-up assessments at 1, 3, and 6 months after intervention by receiving an email or text message with an embedded URL (link) to complete the questionnaires on a secure website. Participants received payments as incentive for participation over 6 months.

For the parent study, we approached 1,109 patients, of which approximately 10% met eligibility and enrolled in the study. The majority (74%) did not meet substance use eligibility, with 33% using too much and the remainder not using enough. A total of 119 adolescents (71% female) with a mean age of 16.7 years (SD = 1.3) were enrolled in the parent study; 84% self-identified as African American, with the rest primarily mixed race, White, and Hispanic ethnicity. We maintained a 95% follow-up rate over 6 months. From the parent study sample of 119, a subsample of 46 adolescents who reported heavy cannabis use was selected for analysis in the current study. There were no significant demographic differences between the full sample and subgroup sample.

Intervention

Adolescents assigned to the intervention condition received a 20-minute intervention referred to as Peer Network Counseling (Mason et al., 2015). Five key motivational interviewing clinical issues guided the intervention: rapport, acceptance, collaboration, reflections, and nonconfrontation. The intervention followed Motivational Enhancement procedures with age-matched substance use normative data presented as feedback. The intervention was structured into four component parts, each lasting for 5 minutes: (a) rapport building and laptop presentation of substance use feedback in simple graphic form, (b) discussion of substance use likes/dislikes and discrepancies, (c) introduction of peer network information and graphical feedback, and (d) summary, change talk, and plans.

Before the intervention, baseline data from the adolescents’ surveys were automatically abstracted (via computer programming) and uploaded to a project website. The counselor accessed this site via laptop, and graphic displays of substance use and peer network characteristics were automatically displayed for the counselor to use during the counseling session.

The rapport building and feedback components were used to establish a nonjudgmental relationship, review substance use history, and present the adolescents with a graphic of their substance use compared with national data. These components were intended to begin reflection and initial dialogue on the adolescents’ current substance use.

The session flowed into asking about likes/dislikes of their substance of choice. This portion of the intervention was intended to reduce resistance and demonstrate to the adolescent that the counselor was aware of both the negative and positive consequences of substance use. The adolescents’ baseline responses were then displayed back to the teens, highlighting motives to use, problems with use, and future plans. These data were used to have the adolescents identify and articulate discrepancies between current use and future plans and values. This portion sought to activate client- initiated reasons to change (change talk).

The peer network component began by introducing the role of peer network on health, mental health, and educa- tion/career using a PowerPoint slide. Next, the adolescent’s personal peer network was examined for protective and risk factors. Peer networks were reviewed for support, prosocial activities, and encouragement for healthful behavior as well as for substance use, influence/offers to use substances, and risky/dangerous activities. See Mason et al. (2015) for an illustration of the peer network feedback graphic. Adolescents were shown the composition of their peer network using bar graphs representing levels of risk and protection for their three closest peers. Teens were encouraged to reflect and to consider making small modifications, such as adjusting the amount of time spent with particular peers and time spent at particular locations, in order to support their goals. Handouts of all graphics were given to participants in a take-home packet.

In the last portion of the intervention, the counselor summarized the session and reflected on client-generated change talk. If the adolescent had articulated a change plan, this was reviewed, encouraged, and supported. If the teen had not made a specific change plan, the counselor encouraged reflection on what was discussed.

Attention control condition

To balance the amount of verbal contact with the counselor, adolescents randomized to the attention control group reviewed an informational handout with the counselor, covering topics related to health behaviors. These sessions lasted 20 minutes, matching the experimental condition in length.

Measures

All data were collected by participant self-report. Participants completed questions on age, race, ethnicity, and gender. We assessed cannabis use with an adapted version of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (2011) Youth Risk Behavior Survey cannabis use item. Participants were asked the number of times they have used cannabis within the last month, coded as 0 = 0 times, 1 = 1 or 2 times, 2 = 3–9 times, 3 = 10–19 times, 4 = 20–39 times, and 5 = 40 or more times.

Analytic approach

We selected cases defined as using cannabis on 10 or more times in the last month, producing a subgroup sample of 46 cases, 18 treatment and 28 control adolescents. Descriptive statistics were calculated on all variables in our models. We controlled for gender, race, and age and examined Condition x Time interactions. The ordinal response data (cannabis use responses coded as 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) were modeled using a mixed-effects proportional odds model (Hedeker, 2003). This model included the six-level ordinal outcome; fixed effects for treatment, time, and their interaction; and a subject-level random effect to account for dependence within subjects. A cumulative logit link function was incorporated, and four unique threshold parameters were also estimated. This combination of fixed effect and threshold estimates allowed for estimation of group- and time-specific cannabis use probabilities at each ordinal level. The NLMIXED procedure was used to estimate model parameters (SAS Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

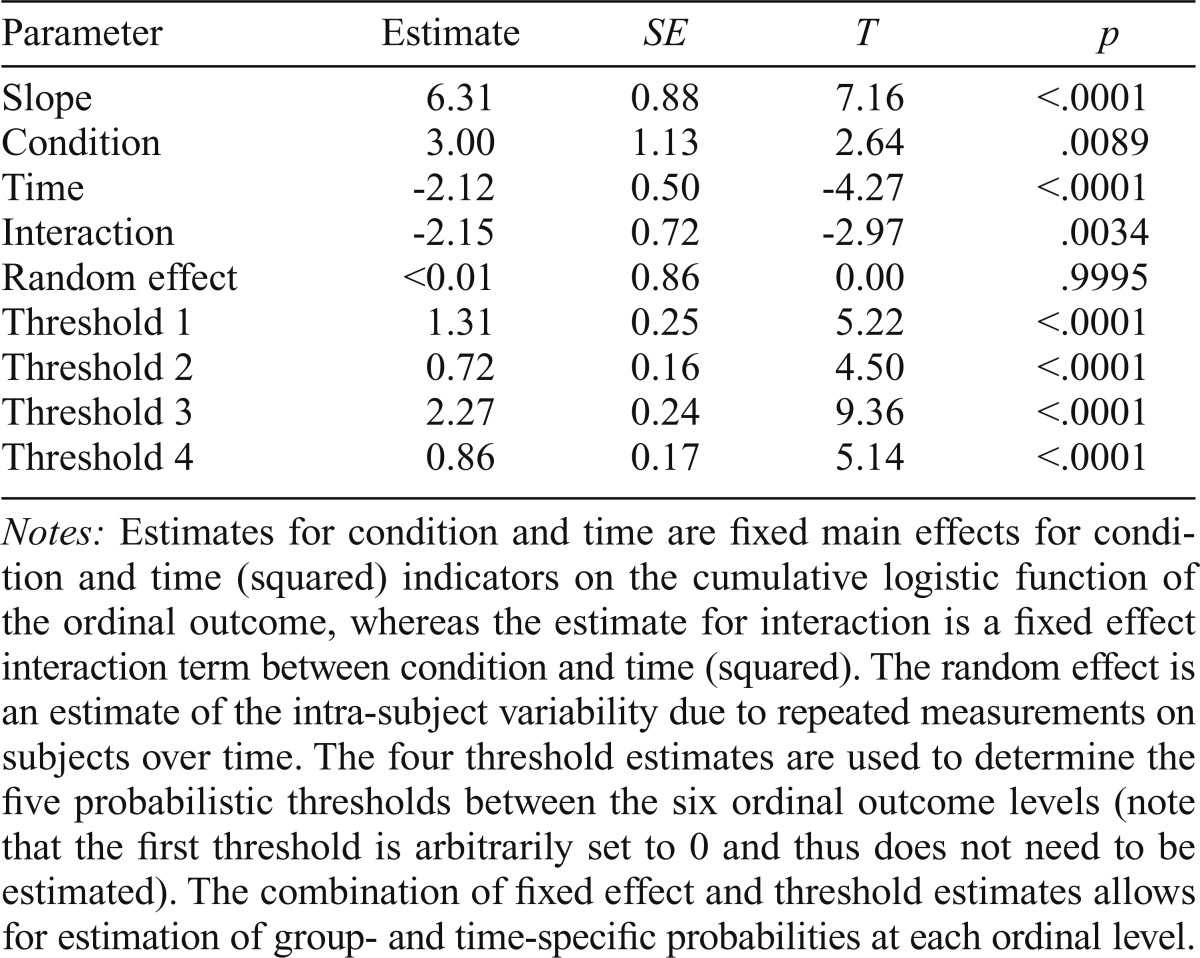

Descriptive statistics for the subsample of heavy cannabis users are shown in Table 1. The follow-up rate for the current study was 95% at 6 months. The estimated regression parameters are found in Table 2. There was significant evidence that all fixed effects were different from their null values; of note, the interaction term was significantly different from 0 (p = .0034). There was no evidence of within-subject dependence (p = .9995). Adjusting these estimates for subject age (p = .6235), gender (p = .1466), or race (p = .4317) did not meaningfully alter these estimates.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study variables by condition (n = 46)

| Variable | Control M (SD) or % (n = 28) | Treatment M (SD) or % (n = 18) |

| Age, in years | 16.7(1.35) | 16.6 (1.37) |

| % Female | 71.4% | 77.8% |

| % African American | 93% | 90% |

| Baseline cannabis usea | 3.42 (0.74) | 3.77 (0.80) |

| 1-month cannabis usea | 3.42 (0.74) | 3.77 (0.80) |

| 3-month cannabis usea | 2.85 (1.71) | 1.91 (1.30) |

| 6-month cannabis usea | 2.00(1.57) | 1.07 (1.04) |

Cannabis use: 1 = 1 or 2 times, 2 = 3–9 times, 3 = 10–19 times, 4 = 20–39 times, 5 = 40 or more times.

Table 2.

Ordinal logistic regression parameter estimates

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | T | p |

| Slope | 6.31 | 0.88 | 7.16 | <.0001 |

| Condition | 3.00 | 1.13 | 2.64 | .0089 |

| Time | -2.12 | 0.50 | -4.27 | <.0001 |

| Interaction | -2.15 | 0.72 | -2.97 | .0034 |

| Random effect | <0.01 | 0.86 | 0.00 | .9995 |

| Threshold 1 | 1.31 | 0.25 | 5.22 | <.0001 |

| Threshold 2 | 0.72 | 0.16 | 4.50 | <.0001 |

| Threshold 3 | 2.27 | 0.24 | 9.36 | <.0001 |

| Threshold 4 | 0.86 | 0.17 | 5.14 | <.0001 |

Notes: Estimates for condition and time are fixed main effects for condition and time (squared) indicators on the cumulative logistic function of the ordinal outcome, whereas the estimate for interaction is a fixed effect interaction term between condition and time (squared). The random effect is an estimate of the intra-subject variability due to repeated measurements on subjects over time. The four threshold estimates are used to determine the five probabilistic thresholds between the six ordinal outcome levels (note that the first threshold is arbitrarily set to 0 and thus does not need to be estimated). The combination of fixed effect and threshold estimates allows for estimation of group- and time-specific probabilities at each ordinal level.

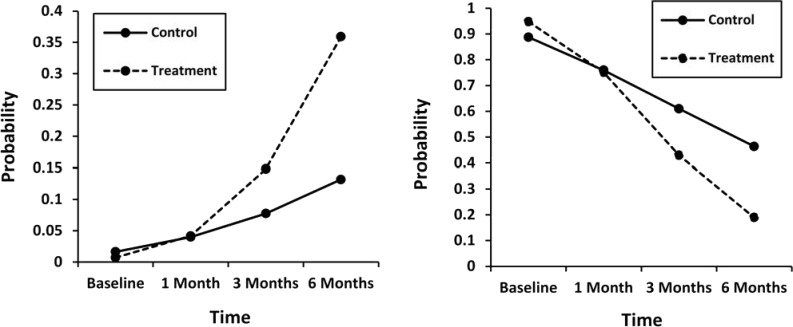

In the left panel of Figure 1, the estimated probabilities of the lowest level of cannabis use (0 times in past month) are presented. At baseline, both groups had zero probability of abstinence, and at 1 month the estimates were similar and low in both conditions. Beginning at Month 3 and continuing through Month 6, the estimated probabilities for PNC were larger than the estimates for the control condition. Adolescents receiving PNC had a .359 probability of being abstinent at Month 6, compared with a .132 probability in the control condition.

Figure 1.

Estimated probability of level of cannabis use by time and condition. The left panel displays the probability of outcome of 0 (no cannabis use in past 30 days). The right panel displays the probability of heavy cannabis use, defined as 10 or more times in the past 30 days. The baseline values for the right panel are not 100% as the values are estimates, not summaries of the observed values.

The right panel of Figure 1 shows a discrepancy in the temporal trends between conditions for the fourth outcome level (used cannabis 10 or more times in the past 30 days).The estimates between groups at baseline and at 1 month are similar; note that the estimated probabilities for both conditions are close to 100% at baseline, as these values are estimates and not summaries of the observed values. From Months 3 to 6 the trajectories change, with the treatment group steeply reducing the probability of using cannabis 10 or more times per month compared with the control group. At Month 6, adolescents in the PNC condition had a .189 probability of using cannabis 10 or more times per month compared with a .463 probability of use in the control condition.

Discussion

The results of this exploratory, secondary analysis study provide preliminary support for the initial efficacy of PNC to reduce cannabis use among adolescents who are heavy users (≥10 times per month). The results reinforce similar research demonstrating the effectiveness of motivational interviewing with a subgroup of heavy users (de Gee et al., 2014). Although the original intent of the parent study was to alter the trajectories of moderate substance-using adolescents (including cannabis, alcohol, and other substances), results from the current study appear promising in reducing cannabis use among adolescents who are heavy users of cannabis.

One interpretation of these results is that if an adolescent is not engaged in heavy cannabis use, brief interventions may have less relevance, and thus effectiveness. It may be that the heavier users became more engaged in the treatment because of personal relevance (e.g., they have experienced negative consequences), and thus decided to stop or reduce their cannabis use. This assumes that greater perceived harm will enhance the motivation of adolescents to change their cannabis use. More research is needed to understand mechanisms of change for PNC.

Last, the results also provide insight into PNC’s effects with a majority female sample, as more than 70% were female. Although majority female adolescent samples are common in primary care research, few studies have examined adolescent females who are heavy users of cannabis; thus, the current study adds to the literature in this area. Continued brief intervention research to study treatment effects by gender with larger samples is warranted.

These results should be tempered by the limitations of the study. First, these results are based on secondary analysis of a parent study and thus have a restricted sample size. Yet given the experimental design, the 6-month follow-up, and the treatment effects, it is reasonable that a larger sample size would follow a similar trend. Second, the study used self-report data and did not include biological verification of outcomes, possibly limiting the confidence in outcomes. However, there is evidence to support the validity of self report (Chan, 2008), even when assessing behavioral health issues such as substance use (Brener et al., 2003). Next, our study was conducted with a sample of non–intervention seeking, majority African American urban adolescents within a primary care setting. Thus, these findings may be harder to generalize to other populations or to suburban or rural settings. Finally, our sample was limited to those adolescents who scored 2 or 3 on the CRAFFT, placing them into the at-risk category and thereby limiting the generalizability of these results.

Taken together, these results are encouraging and add evidence to warrant further investigation of brief interventions targeting cannabis use within primary care settings. Focusing on heavy cannabis use would seem to have much utility as this substance continues to provide challenges in the changing landscape of legalization and medical cannabis use. Developing relevant, brief cannabis use interventions that target non–treatment-seeking, underserved adolescents is an important step in addressing this ongoing public health issue.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant 1R34DA032808 (to Michael J. Mason). The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alegria M., Carson N. J., Goncalves M., Keefe K. Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.005. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstiss T. Motivational interviewing in primary care. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2009;16:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9155-x. doi:10.1007/ s10880-009-9155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A., Wagner E. F. Treatment attrition among racial and ethnic minority youth. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2010;10:63–80. doi:10.1080/15332560903517167. [Google Scholar]

- Becker S. J., Stein G. L., Curry J. F., Hersh J. Ethnic differences among substance-abusing adolescents in a treatment dissemination project. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;42:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.08.007. doi:10.1016/j. jsat.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E., Edwards E., Dorfman D., Heeren T., Bliss C., Bernstein J. Screening and brief intervention to reduce marijuana use among youth and young adults in a pediatric emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2009;16:1174–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00490.x. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black J. J., Chung T. Mechanisms of change in adolescent substance use treatment: How does treatment work? Substance Abuse. 2014;35:344–351. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.925029. doi:10.1080/08897077.2014.925029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener N. D., Billy J. O., Grady W. R. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: Evidence from the scientific literature. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:436–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook J. S., Lee J. Y., Finch S. J., Seltzer N., Brook D. W. Adult work commitment, financial stability, and social environment as related to trajectories of marijuana use beginning in adolescence. Substance Abuse. 2013;34:298–305. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.775092. doi:10.1080/08897077.2013.775092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney A. J., Roffman R., Stephens R. S., Walker D. Marijuana dependence and its treatment. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2007;4:4–16. doi: 10.1151/ascp07414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk W. J., van der Vorst H., Kerr M., Stattin H. Alcohol use and friendship dynamics: Selection and socialization in early-, middle-, and late-adolescent peer networks. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:89–98. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.89. doi:10.15288/jsad.2012.73.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. 2011 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/questionnaires.htm.

- Chan D. Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Received doctrine, verity, and fable in the organizational and social sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2009. So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad? pp. 309–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chung T., Sealy L., Abraham M., Ruglovsky C., Schall J., Maisto S. A. Personal network characteristics of youth in substance use treatment: Motivation for and perceived difficulty of positive network change. Substance Abuse. 2015;36:380–388. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.932319. doi:10.1080/08897077.2014. 932319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland J., Rooke S., Swift W. Changes in cannabis use among young people: Impact on mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2013;26:325–329. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328361eae5. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328361eae5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousijn J., Goudriaan A. E., Ridderinkhof K. R., van den Brink W., Velt-man D. J., Wiers R. W. Approach-bias predicts development of cannabis problem severity in heavy cannabis users: Results from a prospective FMRI study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042394. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0042394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gee E. A., Verdurmen J. E., Bransen E., de Jonge J. M., Schippers G. M. A randomized controlled trial of a brief motivational enhancement for non-treatment-seeking adolescent cannabis users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;47:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.05.001. doi:10.1016/j. jsat.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M., Godley S. H., Diamond G., Tims F. M., Babor T., Donaldson J., Funk R. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson S. J., Gerstle M., Feldstein S. W. Brief interventions and motivational interviewing with children, adolescents, and their parents in pediatric health care settings: A review. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1173. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D. M., Boden J. M. Cannabis use and later life outcomes. Addiction. 2008;103:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris S. K., Csémy L., Sherritt L., Starostova O., Van Hook S., Johnson J., Knight J. R. Computer-facilitated substance use screening and brief advice for teens in primary care: an international trial. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1072–1082. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1624. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D. A mixed-effects multinomial logistic regression model. Statistics in Medicine. 2003;22:1433–1446. doi: 10.1002/sim.1522. doi:10.1002/sim.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen C. D., Cushing C. C., Aylward B. S., Craig J. T., Sorell D. M., Steele R. G. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:433–40. doi: 10.1037/a0023992. doi:10.1037/a0023992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight J. R., Shrier L. A., Bravender T. D., Farrell M., Vander Bilt J., Shaffer H. J. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591. doi:10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, de los Cobos J. P., Hasin D. S., Okuda M., Wang S., Grant B. F., Blanco C. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: Results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;115:120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B. W., Kunz C., Brownell C., Tollefson D., Burke B. L. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2010;20:137–160. doi:10.1177/1049731509347850. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod J., Oakes R., Copello A., Crome I., Egger M, Hickman M., Smith , G. D. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: A systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. The Lancet. 2004;363:1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M., Light J., Campbell L., Keyser-Marcus L., Crewe S., Way T., McHenry C. Peer network counseling with urban adolescents: A randomized controlled trial with moderate substance users. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;58:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.013. doi:10.1016/j. jsat.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M. J., Mennis J., Schmidt C. D. A social operational model of urban adolescents’ tobacco and substance use: a mediational analysis. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:1055–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.11.002. doi:10.1016/j. adolescence.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J., Strang J. The efficacy of single-session motivational interviewing in reducing drug consumption and perceptions of drug-related risk and harm among young people: Results from a multi-site cluster randomized trial. Addiction. 2004;99:39–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00564.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier M. H., Caspi A., Ambler A., Harrington H., Houts R., Keefe R. S. E., Moffitt T. E. Persistent cannabis users show neuro-psychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E2657–E2664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206820109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206820109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard M. S., Tucker J. S., de la Haye K., Green H. D., Kennedy D. P. A prospective study of marijuana use change and cessation among adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;144:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.019. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope H. G., Jr, Gruber A. J., Hudson J. I., Huestis M. A., Yurgelun- Todd D. Neuropsychological performance in long-term cannabis users. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:909–915. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.909. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.10.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S., Miller W. R., Butler C. C. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. [Google Scholar]

- Samson J. E., Tanner-Smith E. E. Single-session alcohol interventions for heavy drinking college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:530–543. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.530. doi:10.15288/jsad.2015.76.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedslund G., Berg R. C., Hammerstram K., Steiro A., Leiknes K. A., Dahl H. M., Karlsen K. Motivational interviewing for substance abuse. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue. 2011;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008063.pub2. Article No. CD008063. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008063.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A., Monti P. M., Barnett N. P., Colby S. M., Sindelar H, Rohse-now D. J., Myers M. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;145:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan M., Schwartz S., Berg B., Walker D., Stephens R., Roffman R. The Teen Marijuana Check-Up: An in-school protocol for eliciting voluntary self-assessment of marijuana use. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2008;8:284–302. doi: 10.1080/15332560802223305. doi:10.1080/15332560802223305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBuskirk K. A., Wetherell J. L. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;37:768–780. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9527-4. doi:10.1007/ s10865-013-9527-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M. A., Bohnert K., Resko S., Barry K. L., Chermack S. T., Zucker R. A., Blow F. C. Computer and therapist based brief interventions among cannabis-using adolescents presenting to primary care: One year outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132:646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.020. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]