Abstract

To evaluate immunity induced by a novel DNA prime-boost regimen, we constructed a DNA plasmid encoding the gag and pol genes from simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) (SIVgag/pol DNA), in addition to a replication-deficient vaccinia virus strain DIs recombinant expressing SIV gag and pol genes (rDIsSIVgag/pol). In mice, priming with SIVgag/pol DNA, followed by rDIsSIVgag/pol induced an SIV-specific lymphoproliferative response that was mediated by a CD4+-T-lymphocyte subset. Immunization with either vaccine alone was insufficient to induce high levels of proliferation or Th1 responses in the animals. The prime-boost regimen also induced SIV Gag-specific cellular responses based on gamma interferon secretion, as well as cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte responses. Thus, the regimen of DNA priming and recombinant DIs boosting induced Th1-type cell-mediated immunity, which was associated with resistance to viral challenge with wild-type vaccinia virus expressing SIVgag/pol, suggesting that this new regimen may hold promise as a safe and effective vaccine against human immunodeficiency virus type 1.

As human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) continues to spread throughout the world (16, 27, 51, 42), the need for a safe and effective prophylactic vaccine is more urgent now than ever (16, 27, 43, 51). A realistic goal for such a vaccine is to limit HIV-1 infection by eliciting immune responses that reduce the viral load and prevent disease progression. With other viral diseases, T-helper-cell type 1 (Th1)-mediated immune responses and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) have been reported to provide protection and reduce disease progression (11, 17, 23, 34, 45, 55, 77). Moreover, Th1/CD8+ T-cell responses have been shown to play an important role in controlling HIV-1 replication (9, 28, 41, 44, 50, 52, 56, 60, 61, 62). In previous studies, nonhuman primates and chimpanzees immunized with attenuated strains of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) or HIV-1 had strong antigen-specific immune responses and were protected from challenge with SIV, simian/human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV), or HIV-1 (1, 15, 66, 81). These studies demonstrate that an experimental immunogen is capable of mediating protection against intravenous and mucosal viral challenge in animal models of HIV and SIV, although attenuated HIV-1 vaccines are generally considered to be unsafe for use in humans (4, 21).

Recently, HIV-1 DNA-based vaccines have been shown to induce protective T-cell-mediated immune responses (12, 13, 33, 57, 75). To increase vaccine efficacy, DNA has also been modified by codon optimization, as well as by coinjection with cytokine-encoding plasmids, recombinant proteins, and other vaccine vectors (7, 10, 29, 32, 46). The immune response to DNA vaccines based on HIV-1 antigen genes was increased when innate and adaptive cytokine genes were combined (5, 14, 22). Furthermore, enhanced levels of protection were demonstrated with a combination regimen consisting of DNA priming (SIV gag, pol, vif, vpx, and vpr, and HIV-1 env, tat, and rev), followed by boosting with a recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA)-based vaccine (SIVgag and pol and HIV-1 env) (2).

Recombinant MVA has been used frequently as a booster vaccine in various combination regimens. In an effort to develop additional safe booster antigens, we generated a recombinant vaccine based on the vaccinia virus strain DIs, which has proven not to replicate in all mammalian cells tested (25). The virologic and immunologic properties of the DIs vector have been reported previously by our group (25, 26, 38, 70, 71). The vaccinia virus DIs vector expressing SIV Gag protein elicited immune responses able to suppress SHIV infection in macaques (26). In the present study, we have demonstrated enhanced Th1-type immune induction in mice primed with a plasmid DNA vaccine encoding SIVgag/pol, followed by boosting with a newly developed recombinant DIs strain that expresses SIVgag/pol (rDIsSIVgag/pol). Our result demonstrates that this new prime-boost regimen is both safe and effective at eliciting anti-immunodeficiency viral immunity, suggesting its promise as a potential vaccine against HIV-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Female BALB/c mice (H-2d) were obtained from Shizuoka Laboratory Center (Shizuoka, Japan) and were used at between 8 and 12 weeks of age.

Construction of SIVgag/pol encoding plasmid DNA.

Plasmid DNA encoding SIVgag/pol was prepared by standard procedures as previously described (47, 48, 64). Briefly, SIVgag/pol DNA was derived from the eucaryotic expression vector pcDNA3.1(−) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). pcDNA3.1(−) was digested with XhoI and EcoRI and ligated to SIVgag and pol genes that were amplified from SHIV-C2/1 DNA (GenBank no. AF217181) with the primers 5′-AACTCGAGAAGATAGAGTGGGAGATGGG and AAGAATTCAGGCTATGCCACCTCTCTA-3′. gag/pol genes were derived from the molecular clone SIVmac239. The correct insertion of SIVgag/pol DNA into the plasmid was confirmed by PCR.

Generation and propagation of rDIsSIVgag/pol.

rDIsSIVgag/pol was constructed based on the previously described protocol (25, 26). The SIVgag/pol gene was first amplified from SHIVNM-3rN DNA (24) by using primers SGP-5 (5′-AATACCCGGGATGGGCGTGAGAAACTC) and SGP-3 (AATAGAGCTCCTATGCCACCTCTCTAG-3′) and then subcloned into the pUCvvp7.5H vector (25, 26). A HindIII fragment encoding SIVgag/pol and the p7.5H promoter region were inserted into the HindIII site of a pUC/DIs transfer vector. rDIsSIVgag/pol and a control vector expressing the gene for LacZ (rDIsLacZ) were generated by homologous recombination and propagated in chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEF). Each virion preparation was purified by sucrose density ultracentrifugation and stored at −120°C. The expression of a 55-kDa protein corresponding to SIV Gag was confirmed by Western blotting with extracts from CEF infected with rDIsSIVgag/pol and anti-SIV Gag-specific monoclonal antibodies (IB6 or V10) (35).

SIV antigens.

Overlapping 15-mer peptides spanning SIV Gag (with 11-amino-acid overlaps) were provided from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (National Institutes of Health, Rockville, Md.). Peptides spanning Gag p27 and p15 regions were divided into eight pools and used as antigens. Purified native SIV p27 Gag protein (SIV Gag) was purchased from Advanced Biotechnologies, Inc. (Rockville, Mass.).

Lymphocyte proliferative assays.

Lymphocyte proliferative assays were performed as previously described (19). One week after the final vaccination, the mice in each of five groups (see Fig. 2) were sacrificed. The spleens were removed, and the tissue was disrupted by compression through a cell strainer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.). Isolated spleen cells were pooled and resuspended at 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin. The CD4+-T-cell, CD8+-T-cell, or CD4+/CD8+-T-cell fraction was then depleted by using magnetic cell sorting (MACS; Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) (20, 63). Aliquots of cells (100 μl) were transferred to 96-well round-bottom plates in triplicate. Either 1 μg of native purified SIV p27 Gag protein or pooled peptides (1 μg/peptide/105 cells) per ml was added to each well. The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 days before the addition of 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine. After an additional 24 h of incubation, the cells were harvested, and the uptake of 3H was determined. The results are expressed as the stimulation index (SI), which was calculated as a ratio of the counts per minute in the presence or absence of antigen.

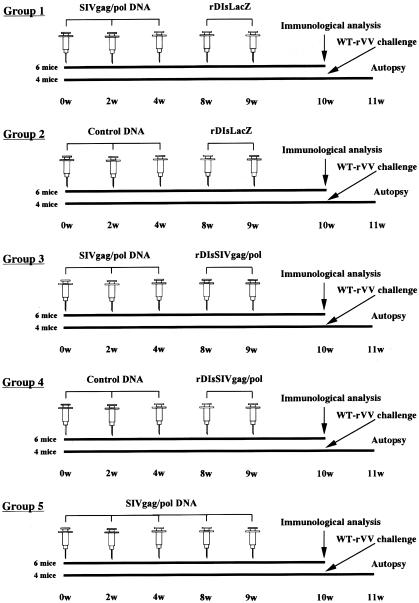

FIG. 2.

Schematic of the experimental protocol for immunization and viral challenge. BALB/c mice were divided into five groups of 10 mice each (groups 1 to 5) and immunized three times consecutively with SIVgag/pol DNA and then twice with rDIsLacZ (group 1), three times with control DNA and then twice with rDIsLacZ (group 2), three times with SIVgag/pol DNA and then twice with rDIsSIVgag/pol (group 3), three times with control DNA and then twice with rDIsSIVgag/pol (group 4), or five times with SIVgag/pol DNA (group 5).

Analysis of antigen-specific cytokine production.

To further characterize the type of immune response induced in the vaccinated mice, CD4+ T cells were isolated from the total spleen cell population by using MACS as described above. The purity of the isolated CD4+ T cells was determined by flow cytometric analysis to be >98% (20, 63). The purified CD4+ T cells were cultured for 3 days at a density of 106 cells/ml in the presence of pooled peptides or SIV Gag protein at a concentration of 10 μg/ml, along with T-cell-depleted and irradiated feeder cells at a density of 106 cells/ml. Culture supernatants were collected, and the concentrations of gamma interferon (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10 were measured by using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.).

IFN-γ-specific ELISPOT assays.

SIV-specific IFN-γ-producing cells were enumerated by using an enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT) and a murine IFN-γ ELISPOT kit (Diaclone Research, Besacon, France). Aliquots (100 μl) of cell suspensions containing 105 spleen cells were transferred to 96-well plates that were coated with anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody. Then, 1 μg of either SIV Gag protein or pooled peptides (1 μg/peptide/105 cells) was added, and the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The plates were then washed three times and incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ antibody for 1 h at 37°C. IFN-γ-specific cells were detected by using streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate and BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) substrate (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Wells were imaged, and spot-forming cells (SFC) were counted by using a KS ELISPOT compact system (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). An SFC was defined as a large black spot with a fuzzy border (40). To determine significance levels, a baseline for each peptide pool was established by using the average and standard deviation (SD) of the number of SFC for each peptide. A threshold significance value, which corresponded to this average plus two SDs, was then determined. A response was considered positive if the number of SFC exceeded the threshold significance level of the control wells with no added peptide.

SIV Gag-specific CTL assays.

Lymphocytes from the vaccinated mice were evaluated for CTL activity by using 51Cr release assays as previously described by Takahashi et al. (72). In brief, spleen cells removed from red blood cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, l-glutamine, 2-mercaptoethanol, penicillin, and streptomycin. The cell suspensions containing 107 spleen cells were restimulated with 0.1 μg/peptide/107 cells of pooled peptides for 5 days. IL-2 containing rat T-cell-stimulated culture supernatant (T-STIM; Collaborative Res. Bedford, Mass.) was added 3 days after cell culture. Cells from the H-2d haplotype line, M12.4.5, were used as targets. M12.4.5 cells were incubated with Na251CrO4 (3.7 MBq/107 cells) for 90 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 before being pulsed with peptides (either 40 or 50 μg). After 1 h, the target cells were thoroughly washed with RPMI 1640 and then dispensed into 96-well V-bottom plates (104 cells/well). The in vitro-stimulated effector cells were added, and the plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C. To determine the spontaneous or maximum release of 51Cr, target cells were incubated with medium alone or treated with 2% Triton X-100, respectively. The percent specific lysis was calculated by using the following formula: (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release).

SIV Gag-specific humoral responses.

SIV Gag-specific antibody endpoint titer was measured by ELISA as previously described (67). ELISA plates were coated with 0.3 μg of SIV Gag protein (Advanced Biotechnologies) per well. Heat-inactivated pooled mice sera were serially diluted and then added to the ELISA plates. Gag-specific antibody bound to Gag protein was captured with alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, Ala.).

Evaluation of vaccine-induced immunity by virus challenge.

To address whether the immune responses induced by the vaccination were protective, mice were challenged with wild-type vaccinia virus recombinant expressing SIVgag/pol (vv9019; National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, Blanch Lane, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom). The viral challenge was performed by using the method set forth by Belyakov et al. (8) and Qiu et al. (54). At 6 days after final vaccination, four mice in each vaccinated group and four naive mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) challenged with 107 PFU of vv9019. One week after the challenge with the recombinant vaccinia virus expressing SIVgag/pol, the mice were sacrificed, and their ovaries were removed. The ovaries were homogenized, sonicated, and assayed for the challenge virus titer by plating serial 10-fold dilutions on a plate of CEF. After 3 days of culture, the plates were stained with 0.2% of crystal violet, and plaque were counted at each dilution. The results were expressed as the fold of the reduction in vaccinia virus titer in vaccinated mice versus the titer in naive mice.

ELISPOT assay for gag, pol, or whole vaccinia virus antigen-specific immunity.

The magnitude of T-cell responses against SIV Gag, Pol, and vaccinia virus antigens was also measured by ELISPOT assay based on the recombinant vaccinia virus stimulation method described previously (74, 80). Briefly, spleen cells isolated from normal mouse were infected with 10 PFU per cell of either SIV gag-expressing wild-type vaccinia virus (vvSIV gag; National Institute for Biological Standards and Control), SIV pol-expressing wild-type vaccinia virus (vvSIV pol; National Institute for Biological Standards and Control), or nonrecombinant wild-type vaccinia virus (Vaccinia WR; National Institutes of Health) for 16 h and then fixed with paraformaldehyde. The virus antigen-expressing cells were used as stimulator cells and cultured with spleen cells of vaccinated mice at a stimulator/responder ratio of 1:2, and each antigen-specific ELISPOT assay was performed by the method described above.

Statistical analysis.

Data are expressed as the mean ± the SD, and data analysis was carried out by using the StatView program (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. The comparative analysis of animal groups subjected to different vaccine regimens was performed by using the Kruskal-Wallis H-test, followed by the Student-Newman-Keul correction.

RESULTS

Construction and expression of SIVgag/pol DNA and rDIsSIVgag/pol.

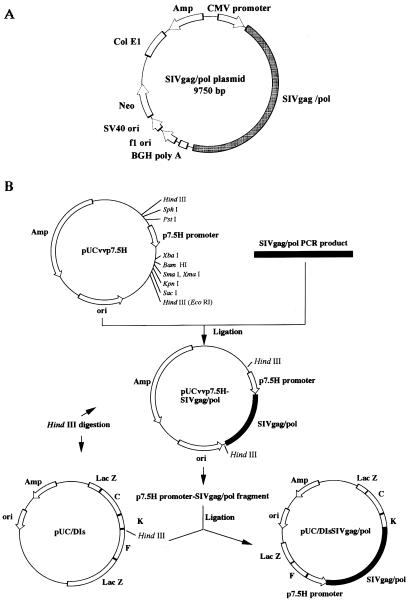

The gag/pol region of SIVmac239 was inserted into two selected vectors. The first, pcDNA3.1(−), a eukaryotic expression vector, was used as the backbone of the SIVgag/pol DNA vaccine (Fig. 1A), and the second, pUC/DIs, was used as a transfer vector to generate rDIsSIVgag/pol and the control vector, rDIsLacZ (Fig. 1B). PCR was used to confirm that the SIVgag/pol DNA had been correctly inserted into each vector and Gag-specific Western blots were used to verify in vitro expression of the SIV Gag protein (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Construction of SIVgag/pol expression vectors. (A) SIVgag/pol plasmid DNA; (B) construction and generation of recombinant DIsSIVgag/pol. The ampicillin resistance gene and vaccinia virus early/late promoter p7.5H are designated by Amp and p7.5H, respectively. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription. Hatched and white blocks represent the SIVgag/pol gene and HindIII fragments of vaccinia virus DNA, respectively.

Prime-boost regimen.

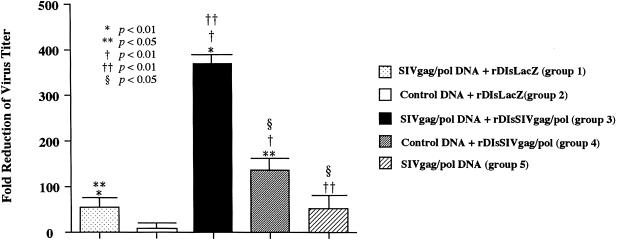

A total of 50 BALB/c mice were divided into five groups of 10 mice each. Group 1 received three intramuscular injections (50 μg of each) of SIVgag/pol DNA at 2-week intervals, followed by two injections of rDIsLacZ (106 PFU each) at with 1-week intervals. Similarly, group 2 mice received three injections with 50 μg of control DNA pcDNA3.1(−), followed by two injections of rDIsLacZ (106 PFU each) at 1-week intervals. Group 3 received three 50-μg intramuscular injections of SIVgag/pol DNA; 4 weeks later, the mice in group 3 were boosted with two intradermal injections of rDIsSIVgag/pol (106 PFU each) with a 1-week interval. The mice in group 4 received three injections of control DNA (50 μg of each), followed by two injections of rDIsSIVgag/pol (106 PFU each) (Fig. 2). In group 5, mice were immunized with SIVgag/pol DNA five times at the same intervals as described above. We confirmed the original data by the second run of the experiments with 50 additional animals and statistically summarized the challenge results (see Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

A second series immunization with the prime-boost regimen resulted in a similar augmentation of protective immune responses. Fifty animals were divided into five groups of 10 animals each, and the animales were immunized by the five different strategies, respectively, described in Fig. 8.

The prime-boost vaccine regimen generates antigen-specific CD4+-T-lymphocyte proliferative responses.

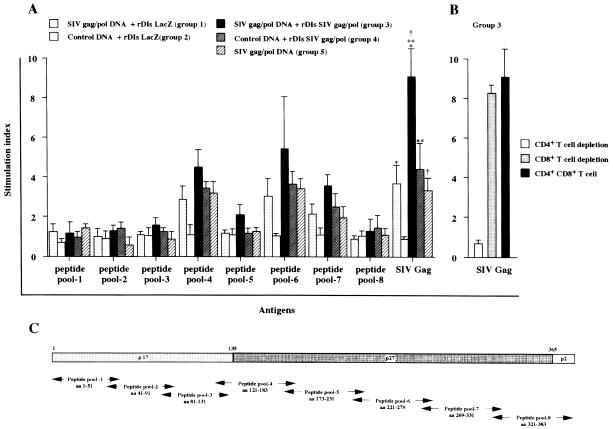

SIV Gag-specific T-lymphocyte proliferative responses were measured in splenocytes from immunized mice with either SIV Gag protein or peptides spanning the full-length Gag protein of SIVmac239. Spleen cells from mice in groups 1, 3, 4, and 5 showed significant levels of proliferation in response to stimulation with SIV Gag protein and peptide pools (Fig. 3), whereas no proliferative activity (SI < 3) was seen with splenocytes from control group 2. Among the five animal groups, splenocytes from the mice in group 3 (immunized with a prime-boost regimen) showed the highest levels of T-cell proliferative responses against SIV Gag proteins (P < 0.01). The mean SIs for each of the five groups were 3.6 ± 1.2, 0.8 ± 0.4, 9.3 ± 2.3, 4.4 ± 1.5, and 3.4 ± 0.96, respectively (SIV Gag protein-stimulated group in Fig. 3A). Depletion of the CD4+- or CD4+ CD8+-T-cell fraction from group 3's splenocytes dramatically reduced the proliferative responses to <10% (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the proliferative activity was not affected by the depletion of the CD8+ fraction from the cell suspensions.

FIG. 3.

Induction of SIV Gag-specific lymphocyte proliferative responses. (A) Spleen cells were cultured in the presence or absence of SIV Gag antigens, and [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Proliferative responses are expressed as the SI. (B) Aliquots of spleen cells from mice vaccinated with the prime-boost regimen were depleted of either the CD4+-T-cell, the CD8+-T-cell, or the CD4+ CD8+-T-cell subpopulation prior to measuring SIV Gag-specific proliferative responses (C). Set of 15-mer overlapping peptides spanning the full-length Gag protein of SIVmac239. The peptides were grouped into eight pools to evaluate cell-mediated immune responses. Values indicated by the single asterisk, double asterisks, and dagger symbol all showed a P value of <0.01, which were compared to give the indicated P values between groups 1 and 3, groups 3 and 4, and groups 3 and 5, respectively.

The splenocytes from the mice in group 3 also exhibited the highest proliferative responses against pooled peptides spanning the full-length SIV Gag protein (Fig. 3). Among the three positive peptide pools (4, 6, and 7), reactivity to pool 6 was the highest, with a mean SI of 5.4 ± 2.8 (Fig. 3A). Peptides in this pool correspond to the SIV p27 region and encode an SIV-specific CD4+-T-cell epitope, which is recognized by the H-2d allele. Splenocytes from mice in control group 2 were not reactive with any of the SIV antigens (SI < 1.0).

Immunization with the prime-boost regimen induces Gag-specific Th1-type responses.

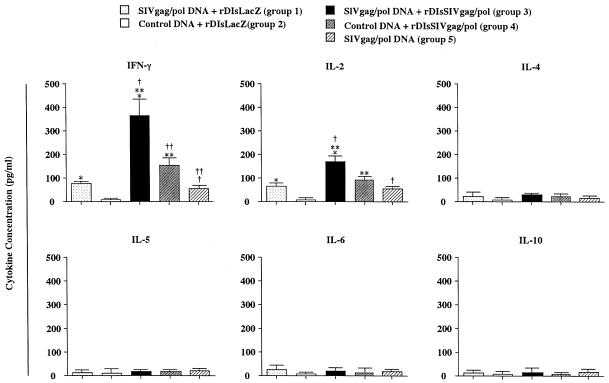

To further characterize the type of immune responses induced by a prime-boost vaccination with SIVgag/pol DNA and rDIsSIVgag/pol, efforts were made to identify distinct antigen-specific CD4+-T-helper-cell subsets. CD4+ T cells were isolated from splenocytes and restimulated in vitro with purified SIV Gag protein. Culture supernatants were then examined for evidence of antigen-specific Th1- or Th2-type cytokine secretion. CD4+ T cells from the immunized mice in group 3 (prime-boost regimen) generated the highest levels of Th1 cytokines, including IFN-γ and IL-2, whereas no evidence was found for the secretion of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, or IL-10 (Fig. 4). The levels of cytokines generated by CD4+ T cells from mice belonging to control group 2 were undetectable. These results demonstrate that priming with SIVgag/pol DNA, followed by boosting with rDIsSIVgag/pol, effectively induces predominantly Th1-type cytokine production in mice.

FIG. 4.

In vitro production of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10 from spleen cells of immunized mice. Spleen cells were stimulated with recombinant SIV Gag protein, and secreted cytokines were quantified by cytokine-specific ELISA. The single asterisk, double asterisks, and dagger symbol all indicate a P value of <0.01, and the double dagger symbol (‡) indicates a P value <0.05, compared to give the indicated P values between groups 1 and 3, groups 3 and 4, groups 3 and 5, and groups 4 and 5, respectively.

Characteristics of SIV-specific immunities in immunized animals at virus challenge.

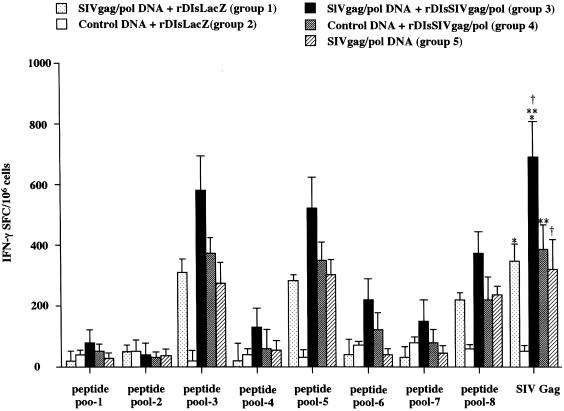

The induction of antigen-specific IFN-γ secretion and CTL was also evaluated in the immunized mice. ELISPOT assays were used to measure the number of SIV-specific SFC secreting IFN-γ in splenocytes from the immunized mice in each group (Fig. 5). Cells were restimulated in vitro with either SIV Gag p27 protein or pooled peptides spanning the full-length SIV Gag. SIV Gag-specific SFC were induced in mice receiving SIVgag/pol DNA alone, rDIsSIVgag/pol alone, or the combined prime-boost regimen. The number of SFC was higher in spleen cells from mice of group 3 immunized with the prime-boost regimen when stimulated with SIV Gag p27 than with Gag protein (735 ± 124 SFC per 106 splenocytes) than in those of mice immunized with either SIVgag/pol DNA or rDIsSIVgag/pol alone (P < 0.01). Stimulation of spleen cells of group 3 with whole Gag showed a stronger response than with Gag peptide pools 3, 5, and 8, with ELISPOT activities of 582 ± 121, 532 ± 117, and 394 ± 85 SFC per 106 splenocytes, respectively.

FIG. 5.

Frequency of SIV Gag-specific IFN-γ-producing cells in immunized mice. Spleen cells were stimulated with either SIV Gag protein or pooled SIV Gag peptides. IFN-γ-producing cells were detected by IFN-γ-specific ELISPOT assays, and data are expressed as the number of SFC per 106 splenocytes. The single asterisk, double asterisks, and dagger symbol all showed a P value of <0.01, which were compared to give the indicated P values between groups 1 and 3, groups 3 and 4, and groups 3 and 5, respectively.

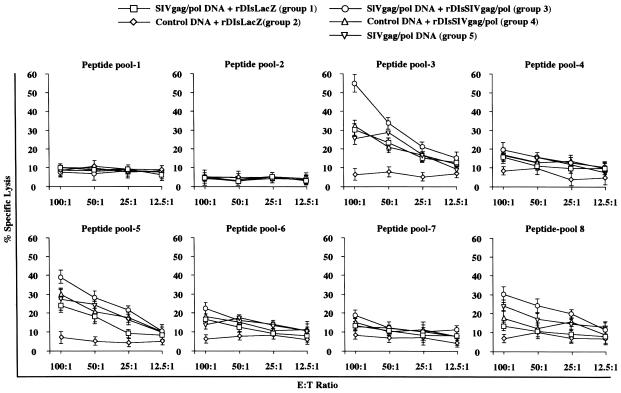

To determine whether the prime-boost regimen was able to induce antigen-specific CTL, 51Cr-release assays were performed 1 week after the final inoculation. Spleen cells were isolated and restimulated in vitro for 7 days with each of eight different peptide pools. Cytotoxic activity was evaluated at effector/target (E:T) ratios of 100:1 to 12.5:1. SIV Gag-specific CTL activity was detected after stimulation with peptide pools 3, 5, and 8 (Fig. 6). The highest specific activity was induced by the prime-boost regimen after restimulation with peptide pool 3 (60% ± 11% specific lysis at an E:T ratio of 100:1). In contrast, spleen cells restimulated with peptides from pools 1, 2, 4, 6, and 7 showed little (<20%) or no specific lysis, as did cells from animals vaccinated with control DNA. CTL activity induction paralleled that of IFN-γ-secreting SFC (Fig. 5) and was dependent on the choice of immunizing and restimulating antigens.

FIG. 6.

Induction of SIV Gag-specific CTL in immunized mice. Spleen cells were stimulated with pooled SIV Gag peptides and tested in 51Cr release assays with peptide pulsed M12.4.4 cells as targets cells at E:T ratios ranging from 100:1 to 12.5:1.

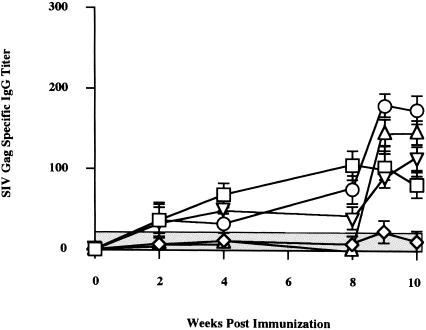

We studied whether this regimen also enhances specific antibody responses (Fig. 7). Three consecutive inoculations of SIVgag/pol DNA, followed by two of rDIsLacZ in group 1 and five consecutive SIVgag/pol DNA vaccinations in group 5, showed low levels of Gag-specific antibody responses, with ELISA titers of <120 throughout the immunization period. Group 4 animals receiving three control DNAs, followed by two rDIsSIVgag/pol vaccinations, and group 5 animals with the prime-boost vaccination also elicited low levels of SIV Gag-specific antibody responses with titers of <180, showing that the induction of SIV Gag-specific humoral responses are very low in these vaccination regimens.

FIG. 7.

Kinetics of binding antibody titer specific for SIV Gag in mice. The endpoint titers of immune sera were measured by the SIV Gag p27 antigen-ELISA at each time point. Bars represent the mean ± the SD value of four independent experiments. Symbols: □, SIVgag/pol DNA + rDIsLacZ (group 1); ◊, control DNA + rDIsLacZ (group 2); ○, SIVgag/pol DNA + rDIsSIVgag/pol (group 3); ▵, control DNA + rDIsSIVgag/pol (group 4); ▿, SIVgag/pol DNA (group 5).

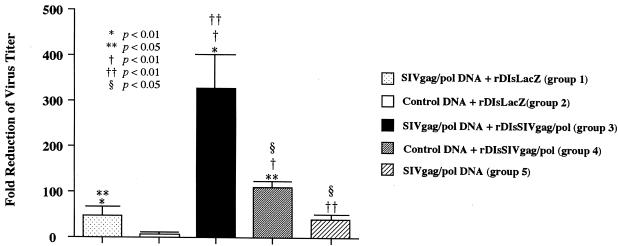

Elicitation of positive immunity by the prime-boost vaccine regimen against challenge with the wild-type SIVgag/pol-expressing vaccinia virus.

Seven days after final vaccination, immunized mice were challenged i.p. with 107 PFU of the wild-type vaccinia virus strain vv9019, which expressed SIVgag/pol. At 6 days after the viral challenge, the mice were sacrificed, and ovaries were harvested to determine the viral load of the challenge virus in the organs. Among the five vaccinated groups, group 3 mice immunized by the prime-boost vaccine regimen showed a striking inhibition of viral infection into ovaries, with a fold reduction as high as 322 ± 48 (dark column in Fig. 8). The mice immunized with other regimens of group 1, 2, 4, or 5 (Fig. 2) showed fold reductions of 52 ± 23, 4 ± 5, 112 ± 21, and 41 ± 10, respectively, in the virus titer. By comparing the different groups with each other and with naive mice, we defined that the prime-boost vaccine group 3 showed statistically the most significant reduction of the viral load of the wild-type virus in tissues (P < 0.01). However, although vaccinated with SIVgag/pol prime and rDIsSIVgag/pol boost, group 3 exhibited no protection when challenged with wild-type vaccinia virus. The comparable vaccine efficacy to these animal groups were achieved by a second-series immunization experiment with 50 more animals (Fig. 9). These results suggest that vaccination with an SIVgag/pol DNA prime, followed by a rDIsSIVgag/pol boost, leads to a protective immunity against challenge with wild-type recombinant vaccinia virus in the immunized animals.

FIG. 8.

The prime-boost vaccine regimen augmented protective immune responses. The animals immunized with five different strategies were challenged i.p. with 107 PFU of wild-type vaccinia virus strain vv9019 recombinant expressing SIVgag/pol. The bar shows the fold reduction of vaccinia virus titer in the ovaries of vaccinated mice versus naive mice. Bars show the geometric mean values of four mice per group.

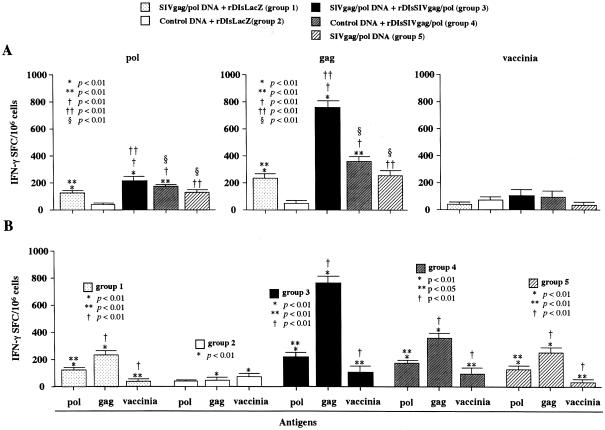

Gag-specific responses dominate in the positive immunity induced by the prime-boost regimen at the time of challenge.

We then studied the immune responses by differentiating the gag-, pol-, and vaccinia virus antigen-specific responses in respective antigen-specific ELISPOT assays (Fig. 10). At the time of vv9019 challenge, we defined not only SIV Gag- but also SIV Pol-specific T-cell responses in immunized animals in groups 1, 3, 4 and 5. However, the Gag response was remarkably higher than the Pol response in group 3 of the prime-boost regimen (P < 0.01) with a less pronounced but similar tendency seen in groups 1, 4, and 5 (P < 0.01). In contrast, vaccinia virus antigen-specific ELISPOT activities were all extremely low, and the positive spots numbered fewer than 80 per million of spleen cells among vaccinia virus- and recombinant vaccinia virus-inoculated groups 2, 3, and 4. The results were not significantly different among the three groups of animals tested, suggesting that the very low levels of vaccinia virus antigen-specific immunity do not significantly contribute to the induction of positive immunity in the prime-boost regimen. These findings demonstrate that the SIVGag-specific T-cell responses dominate in the elicitation of positive immunity induced by the prime-boost vaccine regimen with vaccines expressing SIVgag/pol.

FIG. 10.

Comparison of SIVgag-, SIVpol-, and vaccinia virus antigen-specific immunities in animals at the time of challenge. ELISPOT activities in vaccinated animals with different strategies. Each group of animals was immunized with different strategies and antigen-specific T-cell responses were analyzed by differentiating the SIVgag-, SIVpol-, and vaccinia virus antigen-specificities at the time of challenge infection by using protein antigen-specific ELISPOT assays. (A) SIVgag-, SIVpol-, and vaccinia virus antigen-specific analyses; (B) vaccine strategy-specific analysis of each group of five.

DISCUSSION

Previously, we demonstrated that DNA-based vaccination results in the induction of virus-specific immunity to several viral pathogens, including HIV-1 (3, 47, 48, 53, 64, 76). Furthermore, we recently established a system to express HIV-1 genes by inserting them into a deleted region of the attenuated vaccinia virus strain, DIs (25, 30, 71). Like the parental DIs strain, the recombinant DIs-HIV was shown to be completely replication deficient in mammalian cells. Moreover, the expression of SIVGag was sufficient to elicit positive immunity against pathogenic viral challenge in a SHIV-macaque model (26). In the present study, the prime-boost regimen with HIV-DNA and rDIs-HIV clearly enhanced the protective efficacy over that of rDIs-HIV alone or HIV-DNA alone. Although it is not possible to directly compare protective efficacy among different vector-based vaccine models, recombinant vaccinia virus strains (including MVA) (69), a substrain of Copenhagen (NYVAC) (73), and recombinant adenovirus-HIV strains (68), our results appear to be as effective for obtaining protective immunity as those achieved with vector-based vaccines. Taken together, these results suggest that a combination regimen of DNA and rDIs might be used as a safe and effective vaccine.

In the present study, we addressed whether a prime-boost regimen consisting of a plasmid DNA prime and rDIs boost could promote a strong Th1-type immune response capable of affecting the outcome of experimental challenge. It has been proposed that Th1-type responses are associated with protection against infection, including HIV-1 infection and AIDS. Individuals who control HIV-1 viremia in the absence of antiviral therapy respond to HIV-1 Gag protein and its helper epitopes with a Th1-like response, producing IFN-γ and β-chemokines (58). Moreover, a shift from Th1- to Th2-dominant cytokine production occurs during the course of HIV-1 disease progression (36, 39, 65), suggesting that the cytokine profile may be indicative of a T helper phenotype and represent a response to infection. Our results demonstrate that Th1-type cytokines, including IL-2 and IFN-γ, are secreted by CD4+ T cells from mice immunized with a prime-boost regimen targeting the SIVgag/pol region. These Th1-type responses were associated with SIV Gag protein- or peptide-specific SFC activity and CD8+ CTL. These observations are encouraging in light of the hypothesis that Th1-mediated immunity is associated with resistance to HIV infection and virus suppression (6, 31). In vitro restimulation of splenocytes from mice immunized with the prime-boost regimen generated high levels of Th1 cytokines, such as IL-2 (>100 pg/ml) and IFN-γ (>300 pg/ml), and lower levels of Th2 cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-10 (<30 pg/ml). In contrast, immunization with either SIVgag/pol DNA or rDIsSIVgag/pol alone led to lower levels of Th1-type cytokine production, suggesting that the prime-boost regimen is superior for the induction of SIV Gag-specific Th1-type T-cell responses.

Having observed an induction of SIV Gag-specific Th1-type responses in mice after immunization with the prime-boost regimen, we also detected significant levels of virus-specific proliferative responses in spleen cells from the immunized animals. Fractionation of the spleen cell population revealed that the SIV-specific lymphocyte responses were mediated by CD4+ T cells. Several reports have demonstrated that HIV-1-specific CD4+ T-cell proliferation inversely correlates with disease progression in infected individuals (37, 78). Moreover, HIV-1 Gag p24-specific CD4+-lymphocyte proliferation has been shown to be inversely correlated with the HIV-1 load in plasma (58, 59). Although SIV-specific T-cell proliferative responses were induced in mice immunized with either SIVgag/pol DNA or rDIsSIVgag/pol alone, the SI was generally not as high as that obtained by the combined prime-boost regimen. Our data showing the induction of CD4+-T-cell proliferative responses to SIV Gag in mice immunized with the prime-boost regimen suggests this vaccine approach may be effective at inducing strong virus-specific CD4+-T-cell responses capable of controlling viral load in the immunized animals.

The importance of T helper responses is highlighted in reports that antigen-specific CD4+ T helper cells may promote CTL activity either by a CD4-antigen-presenting cell-CD8 pathway and IL-2 secretion (18, 58, 79) or by an increased production of antiviral cytokines and chemokines. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells promote other types of cell-mediated immunity, including activation of macrophages and cytokine secretion, which may also contribute to the control of HIV-1 and other intracellular pathogens. Recent reports have documented that a vaccine regimen consisting of a DNA prime and a recombinant poxvirus boost generates pathogen-specific protective immune responses (2). The protective role of CTL is also well documented in HIV-1 infection (9, 28, 41, 44, 50, 52, 56, 60, 61, 62), and the induction of an HIV-1-specific CTL population is considered an important goal for most current vaccine strategies. HIV-1 Gag-specific CD8+ cytolysis has been highly correlated with IFN-γ synthesis by CD8+ spleen T cells (49). In the present study, the prime-boost regimen induced significant levels of SIV Gag-specific IFN-γ-producing cells (>700 SFC/106 splenocytes). These responses were higher than those induced by immunization with either SIVgag/pol DNA or rDIsSIVgag/pol alone.

In conclusion, our data show that a new vaccine regimen consisting of SIVgag/pol DNA priming and rDIsSIVgag/pol boosting induces strong SIV Gag-specific and Th1-type cellular immune responses, which were associated with the control of viral challenge. Since the magnitude and phenotype of the induced immunity are believed to be associated with protection against viral infection and disease progression, this new priming-boosting vaccine regimen may be useful for the development of an HIV-1 candidate vaccine. This strategy will be further evaluated to determine its efficacy against viral challenge in a nonhuman primate model.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hidemi Takahashi and Yohko Nakagawa, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Nippon Medical School, Tokyo, Japan, for sharing expertise in and for helpful discussions of the CTL experiments. We also thank Tomoko Takeishi, Department of Bacteriology, Nippon Medical School, Tokyo, Japan, for technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Almond, N., K. Kent, M. Cranage, E. Rud, B. Clarke, and E. J. Stott. 1995. Protection by attenuated immunodeficiency virus in macaques against challenge with virus-infected cells. Lancet 345:1342-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amara, R. R., F. Villinger, J. D. Altman, S. L. Lydy, S. P. O'Neil, S. I. Staprans, D. C. Montefiori, Y. Xu, J. G. Herndon, L. S. Wyatt, M. A. Candido, N. L. Kozyr, P. L. Earl, J. M. Smith, H. L. Ma, B. D. Grimm, M. L. Hulsey, J. Miller, H. M. McClure, J. M. McNicholl, B. Moss, and H. L. Robinson. 2001. Control of a mucosal challenge and prevention of AIDS by a multiprotein DNA/MVA vaccine. Science 292:69-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asakura, Y., P. Lundholm, A. Kjerrstrom, R. Benthin, E. Lucht, J. Fukushima, S. Schwartz, K. Okuda, B. Wahren, and J. Hinkula. 1999. DNA-plasmids of HIV-1 induce systemic and mucosal immune responses. Biol. Chem. 380:375-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baba, T. W., V. Liska, A. H. Khimani, N. B. Ray, P. J. Dailey, D. Penninck, R. Bronson, M. F. Greene, H. M. McClure, L. N. Martin, and R. M. Ruprecht. 1999. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nat. Med. 5:194-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baig, J., D. B. Levy, P. F. McKay, J. E. Schmitz, S. Santra, R. A. Subbramanian, M. J. Kuroda, M. A. Lifton, D. A. Gorgone, L. S. Wyatt, B. Moss, Y. Huang, B. K. Chakrabarti, L. Xu, W. P. Kong, Z. Y. Yang, J. R. Mascola, G. J. Nabel, A. Carville, A. A. Lackner, R. S. Veazey, and N. L. Letvin. 2002. Elicitation of simian immunodeficiency virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in mucosal compartments of rhesus monkeys by systemic vaccination. J. Virol. 76:11484-11490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailer, R. T., A. Holloway, J. Sun, J. B. Margolick, M. Martin, J. Kostman, and L. J. Montaner. 1999. IL-13 and IFN-γ secretion by activated T cells in HIV-1 infection associated with viral suppression and lack of disease progression. J. Immunol. 162:7534-7542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barouch, D. H., A. Craiu, M. J. Kuroda, J. E. Schmitz, X. X. Zheng, S. Santra, J. D. Frost, G. R. Krivulka, M. A. Lifton, C. L. Crabbs, G. Heidecker, H. C. Perry, M. E. Davies, H. Xie, C. E. Nickerson, T. D. Steenbeke, C. I. Lord, D. C. Montefiori, T. B. Strom, J. W. Shiver, M. G. Lewis, and N. L. Letvin. 2000. Augmentation of immune responses to HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus DNA vaccines by IL-12/Ig plasmid administration in rhesus monkeys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4192-4197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belyakov, I. M., M. A. Derby, J. D. Ahlers, B. L. Kelsall, P. Earl, B. Moss, W. Strober, and J. A. Berzofsky. 1998. Mucosal immunization with HIV-1 peptide vaccine induces mucosal and systemic cytotoxic T lymphocytes and protective immunity in mice against intrarectal recombinant HIV-vaccinia challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1709-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard, N. F., C. M. Yannakis, J. S. Lee, and C. M. Tsoukas. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity in HIV-exposed seronegative persons. J. Infect. Dis. 179:538-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billaut-Mulot, O., T. Idziorek, E. Ban, L. Kremer, L. Dupre, M. Loyens, G. Riveau, C. Locht, A. Capron, and G. M. Bahr. 2001. Interleukin-18 modulates immune responses induced by HIV-1 Nef DNA prime/protein boost vaccine. Vaccine 19:95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borrow, P. 1997. Mechanisms of viral clearance and persistence. J. Viral Hepatitis 4(Suppl. 2):16-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyer, J. D., B. Wang, K. E. Ugen, M. Agadjanyan, A. Javadian, P. Frost, K. Dang, R. A. Carrano, R. Ciccarelli, L. Coney, W. V. Williams, and D. B. Weiner. 1996. In vivo protective anti-HIV immune responses in non-human primate through DNA immunization. J. Med. Primatol. 25:242-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyer, J. D., K. E. Ugen, B. Wang, M. Agadjanyan, L. Gilbert, M. L. Bagarazzi, M. Chattergoon, P. Frost, A. Javadian, W. V. Williams, Y. Refaeli, R. B. Ciccarelli, D. McCallus, L. Coney, and D. B. Weiner. 1997. Protection of chimpanzees from high-dose heterologous HIV-1 challenge by DNA vaccination. Nat. Med. 3:526-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chakrabarti, B. K., W. P. Kong, B. Y. Wu, Z. Y. Yang, J. Friborg, X. Ling, S. R. King, D. C. Montefiori, and G. J. Nabel. 2002. Modifications of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein enhance immunogenicity for genetic immunization. J. Virol. 76:5357-5368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniel, M. D., F. Kirchhoff, S. C. Czajak, P. K. Sehgal, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1992. Protective effects of a live attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in nef gene. Science 258:1880-1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esparza, J., S. Osmanov, C. Pattou-Markovic, C. Toure, M. L. Chang, and S. Nixon. 2002. Past, present, and future of HIV vaccine trials in developing countries. Vaccine 20:1897-1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrari, C., A. Penna, A. Bertoletti, A. Cavalli, G. Missale, V. Lamonaca, C. Boni, A. Valli, R. Bertoni, S. Urbani, P. Scognamiglio, and F. Fiaccadori. 1998. Antiviral cell-mediated immune responses during hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection. Rec. Results Cancer Res. 154:330-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heeny, J. L. 2002. The critical role of CD4+ T-cell help in immunity to HIV. Vaccine 20:1961-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hel, Z., D. Venzon, M. Poudyal, W. P. Tsai, L. Giuliani, R. Woodward, C. Chougnet, G. Shearer, J. D. Altman, D. Watkins, N. Bischofberger, A. Abimiku, P. Markham, J. Tartaglia, and G. Franchini. 2000. Viremia control following antiretroviral treatment and therapeutic immunization during primary SIV251 infection of macaques. Nat. Med. 6:1140-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiroi, T., H. Goto, K. Someya, M. Yanagita, M. Honda, N. Yamanaka, and H. Kiyono. 2001. HIV mucosal vaccine: nasal immunization with rBCG-V3J1 induces a long-term V3J1 peptide-specific neutralizing immunity in Th1- and Th2-deficient conditions. J. Immunol. 167:5862-5867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann-Lehmann, R., J. Vlasak, A. L. Williams, A. L. Chenine, H. M. McClure, D. C. Anderson, S. O'Neil, and R. M. Ruprecht. 2003. Live attenuated, nef-deleted SIV is pathogenic in most adult macaques after prolonged observation. AIDS 17:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, Y., W. P. Kong, and G. J. Nabel. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific immunity after genetic immunization is enhanced by modification of Gag and Pol expression. J. Virol. 75:4947-4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hukkanen, V., E. Broberg, A. Salmi, and J. P. Eralinna. 2002. Cytokines in experimental herpes simplex virus infection. Int. Rev. Immunol. 21:355-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Igarashi, T., Y. Ami, H. Yamamoto, R. Shibata, T. Kuwata, R. Mukai, K. Shinohara, T. Komatsu, A. Adachi, and M. Hayami. 1997. Protection of monkeys vaccinated with vpr-and/or nef-defective simian immunodeficiency virus strain mac/human immunodeficiency virus type 1 chimeric viruses: a potential candidate live-attenuated human AIDS vaccine. J. Gen. Virol. 78(Pt. 5):985-989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishii, K., Y. Ueda, K. Matsuo, Y. Matsuura, T. Kitamura, K. Kato, Y. Izumi, K. Someya, T. Ohsu, M. Honda, and T. Miyamura. 2002. Structural analysis of vaccinia virus DIs strain: application as a new replication-deficient viral vector. Virology 302:433-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izumi, Y., Y. Ami, K. Matsuo, K. Someya, T. Sata, N. Yamamoto, and M. Honda. 2003. Intravenous inoculation of replication-deficient recombinant Vaccinia DIs expressing SIV Gag controls highly pathogenic SHIV in monkeys. J. Virol. 77:13248-13256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.Katz, A. 2003. HIV update. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 32:86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaul, R., S. L. Rowland-Jones, J. Kimani, K. Fowke, T. Dong, P. Kiama, J. Rutherford, E. Njagi, F. Mwangi, T. Rostron, J. Onyango, J. Oyugi, K. S. MacDonald, J. J. Bwayo, and F. A. Plummer. 2001. New insights into HIV-1 specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in exposed, persistently seronegative sex workers. Immunol. Lett. 79:3-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kent, S. J., A. Zhao, S. J. Best, J. D. Chandler, D. B. Boyle, and I. A. Ramshaw. 1998. Enhanced T-cell immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a human immunodeficiency virus type-1 vaccine regimen consisting of consecutive priming with DNA and Boosting with recombinant fowlpox virus. J. Virol. 72:10180-10188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitamura, T., Y. Kitamura, and I. Tagaya. 1967. Immunogenicity of an attenuated strain of vaccinia virus on rabbits and monkeys. Nature 215:1187-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kostense, S., K. Vandenberghe, J. Joling, D. Van Baarle, N. Nanlohy, E. Manting, and F. Miedema. 2002. Persistent numbers of tetramer+ CD8+ T cells, but loss of interferon-γ+ HIV-specific T cells during progression to AIDS. Blood 99:2505-2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kusakabe, K., K. Q. Xin, H. Katoh, K. Sumino, E. Hagiwara, S. Kawamoto, K. Okuda, Y. Miyagi, I. Aoki, K. Nishioka, D. Klinman, and K. Okuda. 2000. The timing of GM-CSF expression plasmid administration influence the Th1/Th2 response induced by an HIV-1 specific DNA vaccine. J. Immunol. 164:3102-3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu, S., J. Arthos, D. C. Montefiori, Y. Yasutomi, K. Manson, F. Mustafa, E. Johnson, J. C. Santoro, J. Wissink, J. I. Mullins, J. R. Haynes, N. L. Letvin, M. Wyand, and H. L. Robinson. 1996. Simian immunodeficiency virus DNA vaccine trial in macaques. J. Virol. 70:3978-3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lusso, P. 2000. Chemokines and viruses: the dearest enemies. Virology 273:228-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuo, K., Y. Nishino, T. Kimura, R. Yamaguchi, A. Yamazaki, T. Mikami, and K. Ikuta. 1992. Highly conserved epitope domain in major core protein p24 is structurally similar among human, simian, and feline immunodeficiency viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 73(Pt. 9):2445-2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMichael, A. J., and S. L. Rowland-Jones. 2001. Cellular immune responses to HIV. Nature 410:980-987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McNeil, A. C., W. L. Shupert, C. A. Iyasere, C. W. Hallahan, J. A. Mican, R. T. Davey, Jr., and M. Connors. 2001. High-level HIV-1 viremia suppresses viral antigen-specific CD4+ T cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 20:13878-13883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morita, M., Y. Aoyama, M. Arita, H. Amona, H. Yoshizawa, S. Hashizume, T. Komatsu, and I. Tagaya. 1977. Comparative studies of several vaccinia virus strains by intrathalamic inoculation into cynomolgus monkeys. Arch. Virol. 53:197-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moss, R. B., E. Webb, W. K. Giermakowska, F. C. Jensen, J. R. Savary, M. R. Wallace, and D. J. Carlo. 2000. HIV-1-specific CD4 helper function in persons with chronic HIV-1 infection on antiviral drug therapy as measured by ELISPOT after treatment with an inactivated, gp120-depleted HIV-1 in incomplete Freund adjuvant. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 24:264-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mothe, B. R., H. Horton, D. K. Carter, T. M. Allen, M. E. Liebl, P. Skinner, T. U. Vogel, S. Fuenger, K. Vielhuber, W. Rehrauer, N. Wilson, G. Franchini, J. D. Altman, A. Haase, L. J. Picker, D. B. Allison, and D. I. Watkins. 2002. Dominance of CD8 responses specific for epitopes bound by a single major histocompatibility complex class I molecule during the acute phase of viral infection. J. Virol. 76:875-884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Musey, L., J. Huges, T. Schacker, T. Shea, L. Corey, and M. J. McElrath. 1997. Cytotoxic-T-cell response and disease progression in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:1267-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mwau, M., and A. J. McMichael. 2003. A review of vaccines for HIV prevention. J. Gene Med. 5:3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nabel, G. J. 2002. HIV vaccine strategies. Vaccine 20:1945-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogg, G. S., X. Jin, S. Bonhoeffer, P. R. Dunbar, M. A. Nowak, S. Monard, J. P. Segal, Y. Cao, S. L. Rowland-Jones, V. Cerundolo, A. Hurley, M. Markowitz, D. D. Ho, D. F. Nixon, and A. J. McMichael. 1998. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma viral RNA. Science 279:2103-2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohga, S., A. Nomura, H. Takada, and T. Hara. 2002. Immunological aspects of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 44:203-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okada, E., S. Sasaki, N. Ishii, I. Aoki, T. Yasuda, K. Nishioka, J. Fukushima, J. Miyazaki, B. Wahren, and K. Okuda. 1997. Intranasal immunization of a DNA vaccine with IL-12- and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-expressing plasmids in liposomes induces strong mucosal and cell-mediated immune responses against HIV-1 agents. J. Immunol. 159:3638-3647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Okuda, K., A. Ihata, S. Watabe, E. Okada, T. Yamakawa, K. Hamajima, J. Yang, N. Ishii, M. Nakazawa, K. Ohnari, K. Nakajima, and K. Q. Xin. 2001. Protective immunity against influenza A virus induced by immunization with DNA plasmid containing influenza M gene. Vaccine 19:3681-3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okuda, K., K. Q. Xin, A. Haruki, S. Kawamoto, Y. Kojima, F. Hirahara, H. Okada, D. Klinman, and K. Hamajima. 2001. Transplacental genetic immunization after intravenous delivery of plasmid DNA to pregnant mice. J. Immunol. 167:5478-5484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otten, G. R., M. Chen, B. Doe, J. zur Megede, S. Barnett, and J. Ulmer. 2003. Quantitative assessment of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the mouse: application to vaccine research. Immunol. Lett. 85:215-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinto, L. A., J. Sullivan, J. A. Berzofsky, M. Clerici, H. A. Kessler, A. L. Landay, and G. M. Shearer. 1995. ENV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses in HIV seronegative healthy care workers occupationally exposed to HIV-contaminated body fluid. J. Clin. Investig. 96:867-876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pisani, E., S. Lazzari, N. Walker, and B. Schwartlander. 2003. HIV surveillance: a global perspective. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 32(Suppl. 1):S3-S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pontesilli, O., M. R. Klein, S. R. Kerkhof-Garde, N. G. Pakker, F. de Wolf, H. Schuitemaker, and F. Miedema. 1998. Longitudinal analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses: a predominant gag-specific response in associated with nonprogressive infection. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1008-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Putkonen, P., M. Quesada-Rolander, A. C. Leandersson, S. Schwartz, R. Thorstensson, K. Okuda, B. Wahren, and J. Hinkula. 1998. Immune responses but no protection against SHIV by gene-gun delivery of HIV-1 DNA followed by recombinant subunit protein boosts. Virology 250:293-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qiu, J., R. Nayak, G. E. Tullis, and D. J. Pintel. 2002. Characterization of the transcription profile of adeno-associated virus type 5 reveals a number of unique features compared to previously characterized adeno-associated viruses. J. Virol. 76:12435-12447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rico, M. A., J. A. Quiroga, D. Subria, S. Castanon, J. M. Esteban, M. Pardo, and V. Carreno. 2001. Hepatitis B virus-specific T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion in chronic hepatitis B e antibody-positive patients treated with ribavirin and interferon alpha. Hepatology 33:295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rinaldo, C., X. L. Huang, Z. F. Fan, M. Ding, L. Beltz, A. Logar, D. Panicali, G. Mazzara, J. Liebmann, M. Cottrill, and P. Gupta. 1995. High levels of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) memory cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity and low viral load are associated with lack of disease in HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors. J. Virol. 69:5838-5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robinson, H. L., L. A. Hunt, and R. G. Webster. 1993. Protection against a lethal influenza virus challenge by immunization with a haemagglutine-expressing plasmid DNA. Vaccine 11:957-960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rosenberg, E. S., J. M. Billingsley, A. M. Caliendo, S. L. Boswell, P. E. Sax, S. A. Kalams, and B. D. Walker. 1997. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science 278:1447-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenberg, E. S., L. LaRosa, T. Flynn, G. Robbins, and B. D. Walker. 1999. Characterization of HIV-1-specific T-helper cells in acute and chronic infection. Immunol. Lett. 66:89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rowland-Jones, S. L., D. F. Nixon, M. C. Aldhous, F. Gotch, K. Ariyoshi, N. Hallam, J. S. Kroll, K. Froebel, and A. McMichael. 1993. HIV-specific cytotoxic T-cell activity in an HIV-exposed but uninfected infant. Lancet 341:860-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rowland-Jones, S. L., and A. McMichael. 1995. Immune responses in HIV-exposed seronegatives: have they repelled the virus? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 7:448-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rowland-Jones, S., J. Sutton, K. Ariyoshi, T. Dong, F. Gotch, S. McAdam, D. Whitby, S. Sabally, A. Gallimore, T. Corrah, M. Takiguchi, T. Schultz, A. McMichael, and H. Whittle. 1995. HIV-specific cytotoxic T cells in HIV-exposed but uninfected Gambian women. Nat. Med. 1:59-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sakaue, G., T. Hiroi, Y. Nakagawa, K. Someya, K. Iwatani, Y. Sawa, H. Takahashi, M. Honda, J. Kunisawa, and H. Kiyono. 2003. HIV mucosal vaccine: nasal immunization with gp160-encapsulated hemagglutinating virus of Japan-liposome induces antigen-specific CTLs and neutralizing antibody responses. J. Immunol. 170:495-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sasaki, S., K. Sumino, K. Hamajima, J. Fukushima, N. Ishii, S. Kawamoto, H. Mohri, C. R. Kensil, and K. Okuda. 1998. Induction of systemic and mucosal immune responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by a DNA vaccine formulated with QS-21 saponin adjuvant via intramuscular and intranasal routes. J. Virol. 72:4931-4939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shearer, G. M., M. Clerici, A. Sarin, J. A. Berzofsky, and P. A. Henkart. 1995. Cytokines in immune regulation/pathogenesis in HIV infection. Ciba Found. Symp. 195:142-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shibata, R., C. Siemon, S. C. Czajak, R. C. Desrosiers, and M. Martin. 1997. Live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccines elicit potent resistance against a challenge with a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 chimeric virus. J. Virol. 71:8141-8148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shinohara, K., K. Sakai, S. Ando, Y. Ami, N. Yoshino, E. Takahashi, K. Someya, Y. Suzaki, T. Nakasone, Y. Sasaki, M. Kaizu, Y. Lu, and M. Honda. 1999. A highly pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus with genetic changes in cynomolgus monkey. J. Gen. Virol. 80:1231-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shiver, J. W., T. M. Fu, L. Chen, D. R. Casimiro, M. E. Davies, R. K. Evans, Z. Q. Zhang, A. J. Simon, W. L. Trigona, S. A. Dubey, L. Huang, V. A. Harris, R. S. Long, X. Liang, L. Handt, W. A. Schleif, L. Zhu, D. C. Freed, N. V. Persaud, L. Guan, K. S. Punt, A. Tang, M. Chen, K. A. Wilson, K. B. Collins, G. J. Heidecker, V. R. Fernandez, H. C. Perry, J. G. Joyce, K. M. Grimm, J. C. Cook, P. M. Keller, D. S. Kresock, H. Mach, R. D. Troutman, L. A. Isopi, D. M. Williams, Z. Xu, K. E. Bohannon, D. B. Volkin, D. C. Montefiori, A. Miura, G. R. Krivulka, M. A. Lifton, M. J. Kuroda, J. E. Schmitz, N. L. Letvin, M. J. Caulfield, A. J. Bett, R. Youil, D. C. Kaslow, and E. A. Emini. 2002. Replication-incompetent adenoviral vaccine vector elicits effective anti-immunodeficiency virus immunity. Nature 415:331-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stickl, H., V. Hochstein-Mintzel, and H. C. Huber. 1973. Primary vaccination against smallpox after preliminary vaccination with the attenuated vaccinia virus strain MVA and the use of a new “vaccination stamp.” Munch. Med. Wochenschr. 115:1471-1473. (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tagaya, I., H. Amano, T. Komatu, N. Uchida, and H. Kodama. 1974. Supplement to the pathogenicity of an attenuated vaccinia virus, strain DIs, in cynomolgus monkeys. Jpn. J. Med. Sci. Biol. 27:215-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tagaya, I., T. Kitamura, and Y. Sano. 1961. A new mutant of dermovaccinia virus. Nature 192:381-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Takahashi, H., J. Cohen, A., Hosmalin, K. B. Cease, R. Houghten, J. L. Cornette, C. DeLis, B. Moss, R. N. Germain, and J. A. Berzofsky. 1988. An immunodominant epitope of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein gp160 recognized by class I major histocompatibility complex molecule-restricted murine cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85:3105-3109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tartaglia, J., M. E. Perkus, J. Taylor, E. K. Norton, J. C. Audonnet, W. I. Cox, S. W. Davis, J. van der Hoeven, B. Meignier, M. Riviere, B. Languet, and E. Paoletti. 1992. NYVAC: a highly attenuated strain of vaccinia virus. Virology 188:217-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Voss, G., J. Li, K. Manson, M. Wyand, J. Sodroski, and N. L. Letvin. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. Virology 208:770-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang, B., K. E. Ugen, V. Srikantan, M. G. Agadjanyan, K. Dang, Y. Refaeli, A. I. Sato, J. Boyer, W. V. Williams, and D. B. Weiner. 1993. Gene inoculation generates immune responses against human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:4156-4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Watabe, S., K. Q. Xin, A. Ihata, L. J. Liu, A. Honsho, I. Aoki, K. Hamajima, B. Wahren, and K. Okuda. 2001. Protection against influenza virus challenge by topical application of influenza DNA vaccine. Vaccine 19:4434-4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilson, A. D., J. C. Hopkins, and A. J. Morgan. 2001. In vitro cytokine production and growth inhibition of lymphoblastoid cell lines by CD4+ T cells from Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) seropositive donors. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 126:101-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wilson, J. D. K., N. Imami, A. Watkins, J. Gill, P. Hay, B. Gazzard, M. Westby, and F. M. Gotch. 2000. Loss of CD4+ T cell proliferative ability but not loss of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 specific equates with progression to disease. J. Infect. Dis. 182:792-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wodarz, D., and V. A. A. Jansen. 2001. The role of T cell help for antiviral CTL responses. J. Theor. Biol. 211:419-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yasutomi, Y., H. L. Robinson, S. Lu, F. Mustafa, C. Lekutis, J. Arthos, J. I. Mullins, G. Voss, K. Manson, M. Wyand, and N. L. Letvin. 1996. Simian immunodeficiency virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte induction through DNA vaccination of rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 70:678-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yoshino, N., Y. Ami, K. Someya, S. Ando, K. Shinohara, F. Tashiro, Y. Lu, and M. Honda. 2000. Protective immune responses induced by a non-pathogenic simian/human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) against a challenge of a pathogenic SHIV in monkeys. Microbiol. Immunol. 44:363-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]