Abstract

Household members of cholera patients are at a 100 times higher risk of cholera than the general population. Despite this risk, there are only a handful of studies that have investigated the handwashing practices among hospitalized diarrhea patients and their accompanying household members. To investigate handwashing practices in a hospital setting among this high-risk population, 444 hours of structured observation was conducted in a hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, among 148 cholera patients and their household members. Handwashing with soap practices were observed at the following key events: after toileting, after cleaning the anus of a child, after removing child feces, during food preparation, before eating, and before feeding. Spot-checks were also conducted to observe the presence of soap at bathroom areas. Overall, 4% (4/103) of key events involved handwashing with soap among cholera patients and household members during the structured observation period. This was 3% (1/37) among cholera patients and 5% (3/66) for household members. For toileting events, observed handwashing with soap was 7% (3/46) overall, 7% (1/14) for cholera patients, and 6% (2/32) for household members. For food-related events, overall observed handwashing with soap was 2% (2/93 overall), and 0% (0/34) and 3% (2/59) for cholera patients and household members, respectively. Soap was observed at only 7% (4/55) of handwashing stations used by patients and household members during spot-checks. Observed handwashing with soap at key times among patients and accompanying household members was very low. These findings highlight the urgent need for interventions to target this high-risk population.

Introduction

Severe cholera without adequate rehydration can have a case fatality rate of up to 50%.1 The World Health Organization estimates 3–5 million cholera cases annually.2 Cholera is a waterborne disease and is closely linked to suboptimal environmental conditions.3–5 The causative agent for this disease, Vibrio cholerae, has been associated with crowded housing conditions, poor water and sanitation infrastructure, and poor hygiene practices.6–10 Cholera poses a substantial health burden in low-income countries.11 In Bangladesh, cholera is endemic with a high proportion of cholera cases occurring in the capital of Dhaka, during the spring (March–May) and fall (September–November).12–15

Previous studies in Bangladesh have demonstrated that household members of cholera cases are at a more than 100 times higher risk of a cholera infection than the general population, during the week post presentation of the index case at the hospital.8,10,11,16–18 In our most recent evaluation, we found that 40% of hospitalized cholera cases had at least one household member that developed a cholera infection during this 1-week window.19,20 However, little work has been done to develop interventions for this high-risk population.

For severely dehydrated cholera cases, hospitalization is required with intravenous rehydration and oral rehydration solution.1,21 These cholera patients are often accompanied by a household member that provides care to the patient while they are in the hospital.22,23 These caregivers are often responsible for bedside nursing and cleaning the ill patient, which includes cleaning feces and vomit, which is often done without gloves.5 Therefore, this hospital setting is a high-risk environment for the transmission of enteric infections to household members of patients that serve as caregivers.5,22 However, despite this high risk, there are only a handful of studies that have investigated the handwashing practices of hospitalized diarrhea patients and their family members in a health facility setting and developed interventions to increase this behavior.5,22,24

Handwashing with soap after toileting events and before eating and handling food is highly effective in reducing the risk of diarrheal disease, including enteric infections such as cholera.20,25,26 However, despite the extensive literature demonstrating that handwashing with soap substantially reduces this disease burden, only 19% of the world population is estimated to wash hands with soap after coming into contact with human excreta.24,27–29 The time patients and caregivers spend at a health facility for severe cholera presents the opportunity to deliver water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions. The objective of our study was to observe the handwashing behaviors of cholera patients and their accompanying household members in a health facility setting to inform the development of an intervention targeting this behavior.

Methods

Study site and population.

This study was conducted in a hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh, from October 2013 to November 2014, and was nested within a larger randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of a hospital-based handwashing with soap and water treatment intervention entitled Cholera Hospital-Based Intervention for 7 Days (CHoBI7).20 Suspected cholera cases, defined as patients presenting at the hospital with acute watery diarrhea (three or more loose stools over a 24-hour period) and moderate to severe dehydration using the World Health Organization definition, were screened for the presence of V. cholerae in their stool using the Crystal VC Rapid Dipstick test (Span Diagnostics, Surat, India).30,31 All positive findings by dipstick were confirmed by bacterial culture. All suspected cholera cases admitted to the hospital residing within a police thana (ward) of Dhaka city were eligible for the CHoBI7 trial. Cholera cases were defined as suspected cholera cases with a stool bacterial culture result positive for V. cholerae. Cholera cases were excluded from the study if they had a household member already enrolled (currently or previously), or if they had received cholera vaccine, to avoid confounding from an ongoing vaccine trial. Household members were defined as individuals sharing the same cooking pot as the index cholera case for the past 3 days. The exclusion criteria for all household members were if they had received cholera vaccine, or if the household was currently receiving a hygiene intervention. Only participants in the control arm of the larger randomized controlled trial were eligible to participate in the hospital structured observation study. This allowed us to assess handwashing with soap behaviors in a population not receiving a hygiene intervention. Eligible household members present in the hospital at the time of case enrollment were invited to participate.

Data collection and management.

To observe handwashing with soap practices among cholera patients and their corresponding household members in a health facility setting, we conducted a 3-hour structured observation substudy among control arm cholera patients and household members recruited from October 2013 to November 2014. These structured observations were conducted by trained field research assistants using netbook computers. The structured observation focused on observing handwashing with soap practices at the following key events: 1) after using the toilet, 2) after cleaning a child's anus, 3) after removing child's feces, 4) before eating, 5) before feeding a child, and 6) before preparing food. Only one patient household was observed at a time. Participants were informed that they were being observed to learn about their activities in the hospital; the assessment of handwashing practices was not mentioned. In addition, spot-checks were performed during observations to assess the presence of soap at bathroom areas, which were used by patients and household members and at nonstaff handwashing stations in the hospital. All datasets were reviewed daily by senior research staff (Tahmina Parvin and Sazzadul Islam Bhuyian) who supervised the field research assistants. Data cleaning was conducted in Microsoft Access.

Data analysis.

To assess handwashing with soap among cholera patients and their household members, the number of handwashing with soap events at key events (after using the toilet, after cleaning a child's anus and feces, before eating, and before preparing food) was divided by the total number of key events observed during the 3-hour structured observation period for all study participants. This analysis was also stratified by stool- and food-related events and by participant type (cholera patients or household members). To compare handwashing events between patients and household members, we conducted a Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. We also compared those individuals that washed their hands with water during a key event to those that did not wash hands during a key event. These analyses were performed using STATA 13 software (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Ethics.

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants (cholera patients and household members). This included adult participants (≥ 18 years of age) signing an informed consent form and/or parental consent form and children between 12 and 17 years of age signing an assent form. All study procedures were approved by the Research and Ethical Review Committee of the International Center for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) and the Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Results

Fifty-five cholera patients and 93 corresponding household members were observed during the 3-hour structured observation period (148 participants total and 444 total hours of structured observation). No patients or household members enrolled in the larger randomized controlled trial declined to participate in the hospital structured observation substudy. Sixty-nine percent of cholera patients and 63% of household members were female (Table 1). Nine percent of cholera patients (5/55) were less than 5 years of age, 22% (12/55) were between 5 and 14 years, and 69% (38/55) were 14 years of age or older. For household members, 4% (4/93) were children less than 5 years of age, 7% (6/93) were between 5 and 14 years, and 89% (83/93) were 14 years of age or older.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cholera patients and accompanying household members in a Dhaka hospital, 2013–2014

| Cholera patients | Household members | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | % (N) | % (N) |

| No. of participants | 55 | 93 |

| Female | 69 (38) | 63 (59) |

| Age (median ± SD [min–max]) | 26 ± 20 (1–59) | 32 ± 14 (2–85) |

| Age category (years) | ||

| 0–5 | 9 (5) | 4 (4) |

| 5–14 | 22 (12) | 7 (6) |

| > 14 | 69 (38) | 89 (83) |

| Educational level* | ||

| No formal education | 48 (26) | 67 (28) |

| At least primary school level | 39 (21) | 29 (12) |

| Greater than primary school level | 13 (7) | 4 (2) |

SD = standard deviation.

Household members, N = 42.

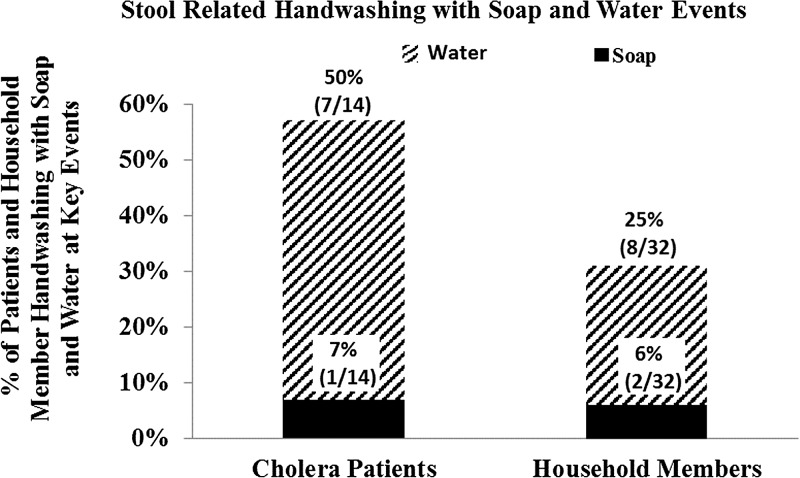

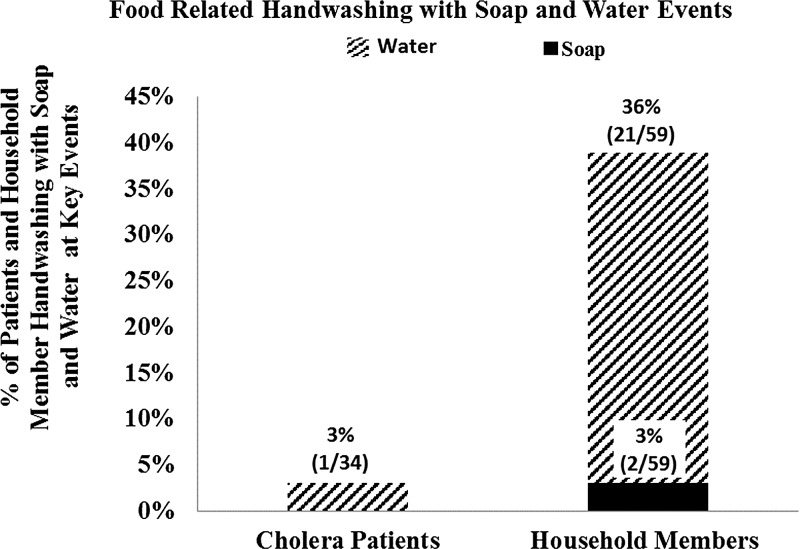

Soap was observed at only 7% (4/55) of handwashing stations used by patients and household members during structured observations (Table 1). All handwashing stations had running water. Overall, 4% (4/103) of key events involved handwashing with soap among cholera patients and household members during the structured observation period. Observed handwashing with soap at key events was 3% (1/37) for cholera patients and 5% (3/66) for household members (P = 0.68). For toileting events, observed handwashing with soap was 7% (3/46) overall, and 7% (1/14) and 6% (2/32) for cholera patients and household members, respectively (P = 1.0) (Figure 1 ). For food-related events, overall observed handwashing with soap was 2% (2/93), and 0% (0/34) and 3% (2/59) for cholera patients and household members, respectively (Figure 2 ).

Figure 1.

Stool-related handwashing with soap and water assessed using structured observation.

Figure 2.

Food-related handwashing with soap and water assessed using structured observation.

Overall, 33% (34/103) of key events involved handwashing with water only among cholera patients and household members during the 3-hour structured observation period. Observed handwashing with water was 22% (8/37) among cholera patients, and 39% (26/66) for household members (P = 0.72). For toileting events, observed handwashing with water was 33% (15/46) overall, and 50% (7/14) for cholera patients and 25% (8/32) for household members (P = 0.05), respectively. For food-related events, overall observed handwashing with water was 24% (22/93), and 3% (1/34) for cholera patients and 36% (21/59) for household members (P = 0.002). Demographic characteristics were also compared for those individuals that washed their hands with water during a key event to those that did not. We observed no significant difference in gender (P = 0.51), age (P = 0.91), or educational level (P = 0.12) for individuals in these two categories.

Discussion

Observed handwashing with soap among cholera patients and household members at key events was very low (4%) in our hospital setting in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Furthermore, only 7% of handwashing stations used by study participants had soap present during the structured observation period. These findings highlight the urgent need for handwashing with soap interventions that target diarrhea patients and their accompanying household members, and improve access to soap in health facility settings.

The observed rates of handwashing with soap among cholera patients and their household members are alarmingly low given the frequent contact these individuals have with infectious bodily fluids such as diarrhea and vomit.5 Our findings are consistent with a recent study in Bangladesh, which found less than 1% observed handwashing with soap at key times in tertiary health facilities among patients, health workers, and caregivers.5 Family caregivers in crowded hospital settings in low-income countries are often responsible for beside nursing and cleaning the ill patient, which includes cleaning feces and vomit, which is often done using unprotected hands.5 In our study hospital, the cholera cots used by patients often had visible vomit and feces present (F. Zohura, personal communication). This environment puts caregivers at high risk for hospital-acquired infections because of their repeated exposure to infectious bodily fluids.5,22,32 Hospital-acquired infections are a major problem in health facilities in Bangladesh.3 This problem is intensified by inadequate hand hygiene practices in this settings.

Inadequate hand hygiene is estimated to result in nearly 300,000 deaths annually, with the majority of deaths being among children under 5 years of age.29 Hands can serve as vectors for disease-causing pathogens, either through direct contact or indirectly via surfaces, which is of particular concern in areas with high environmental contamination such as health facilities.5,22Handwashing with soap after toileting events and before eating and handling food can reduce rates of diarrheal disease by nearly a third.24 Therefore, interventions targeting improved hand hygiene in high-risk health facility settings are of critical public health importance.

Observed handwashing with soap was highest for feces-related events. This is consistent with household structured observation findings from our recent CHoBI7 trial, which included participants from the present study, and with a previous structured observation study conducted in Bangladesh.20,33 We observed handwashing with soap to be more than three times higher when participants were home compared to when they were in the hospital (14% versus 4%).20 In study participant households, soap was found in 16% of latrine areas and 12% of cooking areas compared to 7% of non-staff handwashing stations in the hospital. Therefore this finding likely highlights the difficulties of handwashing with soap in a health facility setting.

The vast majority of participants in our hospital setting used handwashing facilities that lacked soap (93%). Hospital staff at the facility where we conducted this study reported that patients and caregivers often used soap provided by the hospital for washing clothing which left little available for handwashing with soap (C. M. George, personal communication). Consistent with our findings, a study in Bangladesh of three tertiary health facilities found that none of the nonstaff handwashing stations had soap present and only 17% had running water.5 Without access to soap in health facilities, the burden is on patients and their caregivers to bring soap from home or buy soap. This hospital environment puts patients and caregiver at a high risk for hospital-acquired infections.

Most handwashing with soap interventions in Bangladesh are community based.26,34 This is despite the growing evidence that inadequate hand hygiene can put caregivers and accompanying household members in health facilities at increased risk of hospital-acquired infection.5,22 The findings from this study demonstrate the need for infrastructure improvements in health facility settings to allow for the provision of soap for patients and caregivers. Future studies should evaluate the efficacy of theory-driven evidence-based approaches to promote handwashing with soap in health facility settings. Developed interventions should be concise because of the short duration patients and caregiver spend in the hospital, and because intervention programs would probably be integrated in the responsibilities of health-care workers already engaged in providing other services. These interventions should be piloted in hospitals before implementation to explore the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of the developed approaches.

A potential barrier to implementing health facility–based handwashing with soap interventions is the limited water, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructure often found in government health facilities in Bangladesh.32 However, in health facility settings without running water, the use of hand sanitizer could serve as a potential option. Hand sanitizer has been found to be effective in reducing pathogens and has the advantage of not requiring water.34 However, family caregivers in Bangladesh may be unfamiliar with this cleansing agent and would require training on its use.

This study has several limitations. First, we did not measure hand contamination among patients and household members in the hospital where we conducted the structured observation. Therefore, we cannot draw conclusions on whether handwashing with soap reduced hand contamination in this setting. Future work should include measurements of hand contamination. Second, this study focused on cholera patients and their household members, and therefore may not be generalizable to other patients and caregivers in health facility settings. Third, we only conducted our observations at a single urban health facility, and therefore cannot conclude on other health facilities in Bangladesh. Fourth, there is the potential for reactivity because participants knew they were being watched. However, since participants were not informed that their handwashing with soap practices were being observed and given the low rates of handwashing with soap observed, we suspect this impact was minimal.

Conclusions

Observed handwashing with soap during stool and food-related events among cholera patients and accompanying household members was very low. These findings highlight the urgent need for handwashing with soap interventions that target this high-risk population, and the need for future studies to evaluate handwashing with soap behaviors among caregivers and patients in other health facility settings in Bangladesh.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the study participants and the following research assistants who conducted the fieldwork for this study: Ismat Minhaz Uddin, Rafiqul Islam, Al-Mamun, Maynul Hasan, Kalpona Akhter, Khandokar Fazilatunnessa, Sadia Afrin Ananya, Akhi Sultana, Sohag Sarker, Jahed Masud, Abul Sikder, Shirin Akter, and Laki Das. icddr,b is thankful to the governments of Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden, and the United Kingdom for providing core/unrestricted support. icddr,b also acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of NIAID to its research efforts.We would like to express our gratitude to the cholera patients and their accompanying family members who shared their knowledge and time by participating in this study.

Footnotes

Financial support: This study was supported by Grant NIAID 3R01 AI039129-13S1.

Authors' addresses: Fatema Zohura, Sazzadul Islam Bhuyian, Farzana Begum, K. M. Saif-Ur-Rahman, Rumana Sharmin, and Munirul Alam, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dhaka, Bangladesh, E-mails: fzohura@icddrb.org, sazzadul.islam@icddrb.org, farzanab@icddrb.org, r.sharmin@icddrb.org, su.rahman@icddrb.org, and munirul@icddrb.org. Shirajum Monira and Mahamud-ur Rashid, International Health, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), Dhaka, Bangladesh, E-mails: smonira@icddrb.org and mahamudur@icddrb.org. Shwapon K. Biswas, Center for Communicable Diseases, International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), Dhaka, Bangladesh, E-mail: drskbiswas2004@yahoo.com. Tahmina Parvin, Centre for Nutrition and Food Security (CNFS), International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), Dhaka, Bangladesh, E-mail: tparvin@icddrb.org. David Sack, R. Bradley Sack, Elli Leontsini, Xiaotong Zhang, and Christine Marie George, Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, E-mails: dsack@jhsph.edu, rsack1@jhu.edu, eleontsi@jhu.edu, xzhang75@jhmi.edu, and cmgeorge@jhsph.edu.

References

- 1.Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK. Cholera. Lancet. 2004;363:223–233. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Cholera, Fact Sheet N°107. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhuiyan MU, Luby SP, Zaman RU, Rahman MW, Sharker MY, Hossain MJ, Rasul CH, Ekram AS, Rahman M, Sturm-Ramirez K. Incidence of and risk factors for hospital-acquired diarrhea in three tertiary care public hospitals in Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91:165–172. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chikere C, Omoni V, Chikere B. Distribution of potential nosocomial pathogens in a hospital environment. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimi NA, Sultana R, Luby SP, Islam MS, Uddin M, Hossain MJ, Zaman RU, Nahar N, Gurley ES. Infrastructure and contamination of the physical environment in three Bangladeshi hospitals: putting infection control into context. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris JB, LaRocque RC, Chowdhury F, Khan AI, Logvinenko T, Faruque ASG, Ryan ET, Qadri F, Calderwood SB. Susceptibility to Vibrio cholerae infection in a cohort of household contacts of patients with cholera in Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acosta CJ, Galindo CM, Kimario J, Senkoro K, Urassa H, Casals C, Corachán M, Eseko N, Tanner M, Mshinda H. Cholera outbreak in southern Tanzania: risk factors and patterns of transmission. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7((Suppl)):583. doi: 10.3201/eid0707.010741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes JM, Boyce JM, Levine RJ, Khan M, Aziz K, Huq M, Curlin GT. Epidemiology of eltor cholera in rural Bangladesh: importance of surface water in transmission. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60:395. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutin Y, Luby S, Paquet C. A large cholera outbreak in Kano City, Nigeria: the importance of hand washing with soap and the danger of street-vended water. J Water Health. 2003;1:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weil AA, Khan AI, Chowdhury F, LaRocque RC, Faruque A, Ryan ET, Calderwood SB, Qadri F, Harris JB. Clinical outcomes in household contacts of patients with cholera in Bangladesh. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1473–1479. doi: 10.1086/644779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali M, Nelson AR, Lopez AL, Sack DA. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rashed SM, Mannan SB, F-t Johura, Islam MT, Sadique A, Watanabe H, Sack RB, Huq A, Colwell RR, Cravioto A. Genetic characteristics of drug-resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 causing endemic cholera in Dhaka, 2006–2011. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1736–1745. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.049635-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alam M, Hasan NA, Sadique A, Bhuiyan N, Ahmed KU, Nusrin S, Nair GB, Siddique A, Sack RB, Sack DA. Seasonal cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 in the coastal aquatic environment of Bangladesh. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:4096–4104. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00066-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faruque SM, Chowdhury N, Kamruzzaman M, Dziejman M, Rahman MH, Sack DA, Nair GB, Mekalanos JJ. Genetic diversity and virulence potential of environmental Vibrio cholerae population in a cholera-endemic area. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2123–2128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308485100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alam M, Islam A, Bhuiyan NA, Rahim N, Hossain A, Khan GY, Ahmed D, Watanabe H, Izumiya H, Faruque AS, Akanda AS, Islam S, Sack RB, Huq A, Colwell RR, Cravioto A. Clonal transmission, dual peak, and off-season cholera in Bangladesh. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2011;1 doi: 10.3402/iee.v1i0.7273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spira W, Khan MU, Saeed Y, Sattar M. Microbiological surveillance of intra-neighbourhood El Tor cholera transmission in rural Bangaldesh. Bull World Health Organ. 1980;58:731. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosley WH, Ahmad S, Benenson AS, Ahmed A. The relationship of vibriocidal antibody titre to susceptibility to cholera in family contacts of cholera patients. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;38:777–785. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glass RI, Svennerholm AM, Khan MR, Huda S, Huq MI, Holmgren J. Seroepidemiological studies of El Tor cholera in Bangladesh: association of serum antibody levels with protection. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:236–242. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.George CM, Jung DS, Saif-Ur-Rahman K, Monira S, Sack DA, M-u Rashid, Mahmud T, Mustafiz M, Rahman Z, Bhuyian SI, Winch PJ, Leontsini E, Perin J, Begum F, Zohura F, Biswas S, Parvin T, Sack RB, Alam M. Sustained uptake of a hospital-based handwashing with soap and water treatment intervention (Cholera-Hospital-Based Intervention for 7 days [CHoBI7]): a randomized controlled trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:428–436. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George CM, Monira S, Sack DA, Rashid MU, Saif-Ur-Rahman KM, Mahmud T, Rahman Z, Mustafiz M, Bhuyian SI, Winch PJ, Leontsini E, Perin J, Begum F, Zohura F, Biswas S, Parvin T, Zhang X, Jung D, Sack RB, Alam M. Randomized controlled trial of hospital-based hygiene and water treatment intervention (CHoBI7) to reduce cholera. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:233–241. doi: 10.3201/eid2202.151175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molla A, Ahmed S, Greenough W., 3rd Rice-based oral rehydration solution decreases the stool volume in acute diarrhoea. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63:751. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Islam MS, Luby SP, Sultana R, Rimi NA, Zaman RU, Uddin M, Nahar N, Rahman M, Hossain MJ, Gurley ES. Family caregivers in public tertiary care hospitals in Bangladesh: risks and opportunities for infection control. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hadley MB, Blum LS, Mujaddid S, Parveen S, Nuremowla S, Haque ME, Ullah M. Why Bangladeshi nurses avoid ‘nursing’: social and structural factors on hospital wards in Bangladesh. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1166–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fewtrell L, Kaufmann RB, Kay D, Enanoria W, Haller L, Colford JM., Jr Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:42–52. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis V, Cairncross S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:275–281. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00606-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luby SP, Halder AK, Huda T, Unicomb L, Johnston RB. The effect of handwashing at recommended times with water alone and with soap on child diarrhea in rural Bangladesh: an observational study. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luby SP, Agboatwalla M, Feikin DR, Painter J, Billhimer W, Altaf A, Hoekstra RM. Effect of handwashing on child health: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:225–233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66912-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman MC, Stocks ME, Cumming O, Jeandron A, Higgins JP, Wolf J, Pruss-Ustun A, Bonjour S, Hunter PR, Fewtrell L, Curtis V. Hygiene and health: systematic review of handwashing practices worldwide and update of health effects. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19:906–916. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pruss-Ustun A, Bartram J, Clasen T, Colford JM, Jr, Cumming O, Curtis V, Bonjour S, Dangour AD, De France J, Fewtrell L, Freeman MC, Gordon B, Hunter PR, Johnston RB, Mathers C, Mausezahl D, Medlicott K, Neira M, Stocks M, Wolf J, Cairncross S. Burden of disease from inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene in low- and middle-income settings: a retrospective analysis of data from 145 countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19:894–905. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.George CM, Rashid MU, Sack DA, Bradley Sack R, Saif-Ur-Rahman K, Azman AS, Monira S, Bhuyian SI, Zillur Rahman K, Toslim Mahmud M. Evaluation of enrichment method for the detection of Vibrio cholerae O1 using a rapid dipstick test in Bangladesh. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;19:301–307. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization (WHO) The Treatment of Diarrhoea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Unicomb L, Islam DK, Noor KA. Bangladesh National Hygiene Baseline Survey: Preliminary Report. 2014. BangladeshNationalHygieneBaselineSurveyPreliminaryReport.pdf Available at.

- 33.Halder A, Tronchet C, Akhter S, Bhuiya A, Johnston R, Luby S. Observed hand cleanliness and other measures of handwashing behavior in rural Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:545. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luby SP, Kadir MA, Sharker Y, Yeasmin F, Unicomb L, Sirajul Islam M. A community‐randomised controlled trial promoting waterless hand sanitizer and handwashing with soap, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:1508–1516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]