Abstract

Objective To determine the inherited factors associated with the ability to smell asparagus metabolites in urine.

Design Genome wide association study.

Setting Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study cohorts.

Participants 6909 men and women of European-American descent with available genetic data from genome wide association studies.

Main outcome measure Participants were characterized as asparagus smellers if they strongly agreed with the prompt “after eating asparagus, you notice a strong characteristic odor in your urine,” and anosmic if otherwise. We calculated per-allele estimates of asparagus anosmia for about nine million single nucleotide polymorphisms using logistic regression. P values <5×10-8 were considered as genome wide significant.

Results 58.0% of men (n=1449/2500) and 61.5% of women (n=2712/4409) had anosmia. 871 single nucleotide polymorphisms reached genome wide significance for asparagus anosmia, all in a region on chromosome 1 (1q44: 248139851-248595299) containing multiple genes in the olfactory receptor 2 (OR2) family. Conditional analyses revealed three independent markers associated with asparagus anosmia: rs13373863, rs71538191, and rs6689553.

Conclusion A large proportion of people have asparagus anosmia. Genetic variation near multiple olfactory receptor genes is associated with the ability of an individual to smell the metabolites of asparagus in urine. Future replication studies are necessary before considering targeted therapies to help anosmic people discover what they are missing.

Introduction

In 1781 Benjamin Franklin remarked, “a few stems of asparagus eaten, shall give our urine a disagreeable odour.”1 2 3 The consequence of asparagus consumption has been a topic of both public and private discussion, with Proust’s observation of asparagus spears perhaps the most poetic, “they played . . . at transforming my humble chamber into a bower of aromatic perfume.”4 For those who can detect the distinctive sulfurous odor it must seem, as the French botanist and chemist Louis Lémery wrote in 1702, “They [asparagus spears] cause a filthy and disagreeable smell in the urine, as everybody knows.”1

But not everybody does seem to know, as a subset of the population is unable to smell the methanethiol and S-methyl thioesters metabolites produced by asparagus consumption. It was uncertain whether this inability to detect the metabolites5 6 was related to a failure to produce the metabolites or to a specific anosmia. Foundational research found that the prevalence differs between people and across populations.6 7 8 Studies have shown that people who cannot smell the odor in their own urine are also unable to smell it in the urine of known producers,7 9 lending credence to the anosmia hypothesis. Regardless of whether the inability to detect the odor is a problem of perception or production, the phenotypic distribution suggests a potential genetic component.6 7

Few scientists have sought to examine the inherited factors associated with asparagus anosmia. In 2010 the results of a genome wide association study in 4727 participants was reported.10 The study found that a single nucleotide polymorphism—an individual genetic variation in DNA—rs4481887 located near olfactory receptor 2M7 (OR2M7) was statistically significantly associated with participant reported anosmia to asparagus.

Given the complexity of olfactory receptors it is likely that additional genetic variations contribute to the differences in humans’ ability to detect the odor of asparagus metabolites. We therefore carried out a genome wide association study of asparagus anosmia among two large and well characterized US based cohorts: the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study.

Methods

This study was conceived during a scientific meeting attended by several of the coauthors in bucolic Sweden, where it became apparent that some of us were unable to detect any unusual odor in our urine after consuming new spring asparagus. We subsequently sought epidemiological studies to further examine this phenomenon, and found the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (see supplementary file for details). The participants included in the current study included men and women of European descent with available genetic data from genome wide association studies from nested case-control studies.11 All participants gave informed consent, including consent for genetic analyses.

Definition of asparagus anosmia

The main outcome in our study was asparagus anosmia, which was collected in both the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study as part of a broader supplemental questionnaire sent to participants in 2010. They were asked to respond to the prompt: “After eating asparagus, you notice a strong characteristic odor in your urine.” For the primary analysis, participants who responded “Strongly agree” were categorized as being able to smell asparagus and those who responded “Moderately agree,” “Slightly agree,” “Slightly disagree,” “Moderately disagree,” and “Strongly disagree” were categorized as having asparagus anosmia. Those who responded “I don’t eat asparagus” were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

We carried out multivariable logistic regression analyses, modeling single nucleotide polymorphisms as ordinal variables and asparagus anosmia as the outcome. Models were adjusted for age, sex, smoking status (never, former, and current), and the first three principal components of genetic variation (to adjust for potential confounding by ethnicity). The analyses were conducted separately for each of the three genotyping platforms and the estimates were combined using a fixed effects meta-analysis. We considered P values <5×10-8 to indicate genome wide significance, and all tests were two sided.12

To further explore the association between genetic variation and asparagus anosmia, we performed sequential conditional analysis using GCTA-COJO, a tool for genome wide complex trait analysis.13 14 The supplementary file describes these analyses in detail. Briefly, this method allows adjustment for single nucleotide polymorphism-B when evaluating the association between single nucleotide polymorphism-A and anosmia to determine if they have independent effects or are both associated with the outcome through correlation.

We then used the variant effect predictor tool to determine the effect of the variants on the amino acid sequence. Using the PolyPhen analysis tool (version 2.2.2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), we explored the possible impact of missense mutations (ie, a change in one DNA base pair that results in the change in one amino acid for another in the protein) on the structure and function of a protein. PolyPhen uses a set algorithm to predict the likelihood that the single nucleotide polymorphism will be “probably damaging” (that is, high confidence the single nucleotide polymorphism affects protein function or structure), “possibly damaging” (supposed to affect protein function or structure), or “benign” (most likely lacking any phenotypic effect).

Patient involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for recruitment, design, or implementation of the study. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Results

Among 6909 participants, 39.8% (n=2748) strongly agreed that they could perceive a distinct odor in their urine after eating asparagus and 60.3% (n=4161) said they could not and were classified as asparagus anosmic (table 1). The proportion of participants unable to detect the odor was slightly lower among men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study compared with women in the Nurses’ Health Study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population by ability to smell metabolites of asparagus in urine, 2010. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | HPFS (n=2500) | NHS (n=4409) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anosmic | Able to smell | Anosmic | Able to smell | ||

| Study sample | 1449 (58) | 1051 (42) | 2712 (62) | 1697 (38) | |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 76 (8) | 75 (8) | 78 (6) | 76 (6) | |

| Smoking status: | |||||

| Current smoker | 50 (2) | 25 (1) | 221 (5) | 132 (3) | |

| Former smoker | 1100 (44) | 1100 (44) | 2160 (49) | 2160 (49) | |

| Never smoker | 1350 (54) | 1375 (55) | 2028 (46) | 2116 (48) | |

HPFS=Health Professionals Follow-up Study; NHS=Nurses’ Health Study.

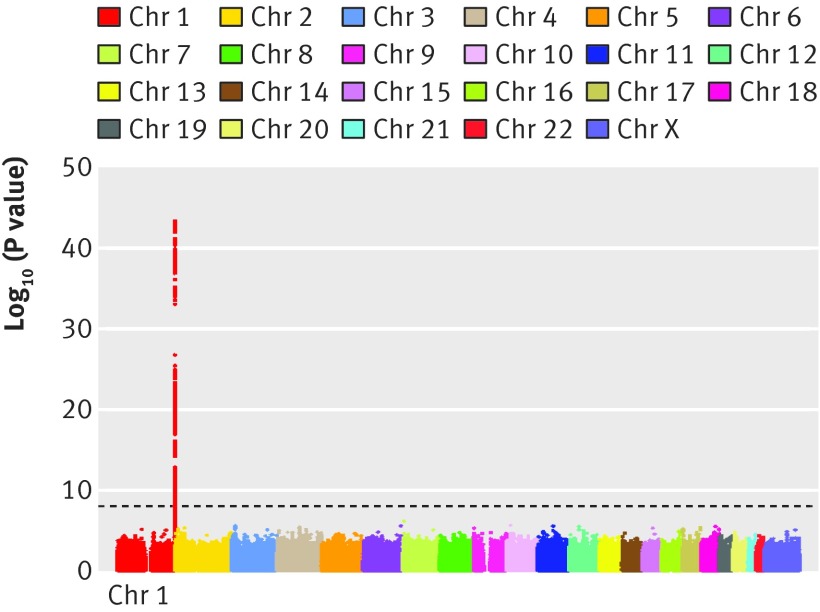

Overall, 871 single nucleotide polymorphisms reached genome wide significance (P<5×10-8) for asparagus anosmia (see supplementary table 1). Figure 1 displays a Manhattan plot in which each dot represents a single nucleotide polymorphism laid out across the chromosomes from left to right. The height of the peaks corresponds to the strength of association with asparagus anosmia. The large peak represents a 0.46 Mb region on chromosome 1 (248139851-248595299). This region was split into two subregions by a recombination hotspot (see supplementary figure 2) and contained multiple members of the olfactory receptor 2 (OR2) gene family. The single nucleotide polymorphism identified previously in one study10 and validated in another study9 (rs4481887) was also significantly associated with asparagus anosmia in this population (P=1.41×10-43) and is located in the same 1q44 region identified in this analysis.

Fig 1 Manhattan plot showing results of genome wide association studies for asparagus anosmia. Chr=chromosome

Sequential conditional analysis revealed three loci independently associated with asparagus anosmia in this region (rs13373863, rs71538191, and rs6689553) (table 2). After conditioning on these three single nucleotide polymorphisms, no other single nucleotide polymorphism reached genome wide significance. Supplementary tables 2 and 3 and supplementary figures 2a and 2b present a more detailed analysis and visualization of this region.

Table 2.

Results of stepwise conditional analysis: single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that remained independently statistically significantly associated with asparagus anosmia after mutual adjustment

| SNP | Reference allele | Alternate allele | Frequency of reference allele | Marginal odds ratio (95% CI) | Marginal P value | Conditional odds ratio (95% CI) | Conditional P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs13373863 | A | G | 0.07 | 1.13 (1.08 to 1.17) | 4.11e-10 | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.20) | 5.51e-14 |

| rs71538191 | C | G | 0.60 | 0.85 (0.84 to 0.87) | 1.86e-41 | 0.90 (0.89 to 0.92) | 7.02e-13 |

| rs6689553 | T | C | 0.32 | 1.15 (1.13 to 1.17) | 4.26e-44 | 1.11 (1.08 to 1.13) | 7.51e-19 |

Overall, 35 missense single nucleotide polymorphisms were identified, 17 of which were marginally associated with asparagus anosmia. Of these, three single nucleotide polymorphisms were classified as “probably damaging,” with PolyPhen scores greater than 0.95 (rs6658227, rs28545014, and rs755310), and one (rs7555424) as “possibly damaging” (PolyPhen score 0.85) (table 3). Two of these missense single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs7555310 and rs7555424 in OR2M7) were in linkage disequilibrium with one of the single nucleotide polymorphisms identified in the conditional analysis, rs6689553 (r2=0.80).

Table 3.

Missense single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with asparagus anosmia at genome wide significance (P<5×10-8)

| SNP | Gene | Possible impact | PolyPhen score | Reference allele | Alternate allele | Marginal odds ratio (95% CI) | Marginal P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs6658227 | OR2L3 | Probably damaging | 0.97 | T | C | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.09) | 2.94e-9 |

| rs28545014 | OR14C36 | Probably damaging | 1 | T | G | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) | 3.53e-12 |

| rs7555310 | OR2M7 | Probably damaging | 0.97 | A | G | 1.14 (1.12 to 1.16) | 2.62e-43 |

| rs7555424 | OR2M7 | Possibly damaging | 0.85 | A | G | 1.14 (1.12 to 1.16) | 2.50e-43 |

Discussion

Anosmia for the urinary metabolites of asparagus is common. In this study of 6909 European-American men and women, three in five were unable to detect the odor in their urine. Linking information from genome wide association studies with the anosmia trait, we found 871 unique single nucleotide polymorphisms reaching genome wide significance. All were located on chromosome 1, containing multiple members of the olfactory receptor 2 gene family.

Our analyses included imputed single nucleotide polymorphisms from the 1000 Genomes Project, which allowed us to more thoroughly identify novel single nucleotide polymorphisms that might interact with the previously identified single nucleotide polymorphism to produce the anosmic phenotype. The previous genome wide association studies of asparagus anosmia identified an association with rs4481887, 8993 base pairs upstream of OR2M7. By incorporating comprehensive efforts to refine the signal, we identified three independent association signals in this region, tagged by rs13373863, rs71538191, and rs6689553. Although we did not conduct a further replication study of the genome wide signals, our findings validate and extend the previously reported associations between OR2 and asparagus anosmia. Both our study and a previous study10 were conducted on people of European descent; thus it is unclear whether results would differ in non-European populations.

Two “probably damaging” missense single nucleotide polymorphisms in OR2M7 in strong linkage disequilibrium with rs6689553 (rs7555310 and rs7555424) are intriguing candidate variants that might be responsible for this association. We also identified a missense variant in OR2L3 that could be responsible for the association signal tagged by rs13373863. OR2L3, OR14C36, and OR2M7 are thought to be involved in G-protein receptor and olfactory receptor activity, and OR14C36 in the binding of an odorant to its receptor. The molecular basis at the root of human olfaction is not fully understood. Research has investigated specific anosmias and hyperosmias as a key to understanding olfaction, often focusing on the genetic determinants of these phenomena to better understand the overall functional relation. Our findings present candidate genes of interest for future research on the structure and function of olfactory receptors and on the compounds responsible for the distinctive odor produced by asparagus metabolites. Answering these questions might shed light more generally on the relation between the molecular structure of an odorant and its perceived odor.

Asparagus has long been recognized as a delicacy. Writings by the Roman scholar Cato the Elder around 200 BC provide a method of planting asparagus,15 and a recipe for cooking asparagus is found in Apicius’s De Re Coquinaria from the late 4th century AD.16 According to the United States Department of Agriculture food composition database, asparagus is rich in iron, fiber, zinc, folate, and vitamins A, E and C. Consumption of asparagus, as part of a diet high in vegetables, has been hypothesized to reduce the risk of cancer, cognitive impairment, and cardiovascular related diseases.17 18 19 20 21 Under the assumption that the urinary odor from asparagus consumption leads to avoidance of this vegetable, future work should consider Mendelian randomization studies using these identified single nucleotide polymorphisms to better understand how a lifetime of eating asparagus might protect people from developing chronic conditions. Furthermore, literature from the 15th century touts its aphrodisiac qualities.22 Studies could investigate assortative mating with respect to asparagus anosmia; however, differentiating choice of partner based on preference for flavor or odor would be challenging.

Interestingly, women in the Nurses’ Health Study were more likely to report asparagus anosmia than men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study, despite the fact that women have been shown to more accurately and consistently identify smells.23 24 We hypothesize that this unexpected result might be due to underreporting by a few modest women who are loathe to admit they can smell the distinctive odor in their urine. It is possible that women are less likely than men to notice an unusual odor in their urine because their position during urination might reduce their exposure to volatile odorants. This highlights a weakness of our study design that is shared by many studies of olfactory perception—namely, that we rely on self report of perception rather than on an objective measurement of olfactory stimulation. Our study is also limited by a one-time measure of anosmia; therefore, we do not have information on whether the ability to smell asparagus metabolites changes with age, and previous studies have shown that as humans age, their general olfactory function declines.

Outstanding questions on this topic remain; first and foremost perhaps is why a delicacy such as asparagus results in such a strong odor? Why does genetic variation across the olfactory receptor genes exist that leads to susceptibility to asparagus anosmia? What selective pressures—one way or the other—would drive different populations of people to have the ability to smell the metabolites of asparagus and others to not? And, will scientists take the results of our study and apply gene editing techniques to convert smellers to non-smellers?25

This holiday season, try Apicius’s asparagus recipe and generate a provocative discussion with your loved ones about the “filthy and disagreeable smell in the urine.”1 16 Asparagus is not all contentious: make sure to serve the leaves as well to protect the liver against toxic insults26 so that you can enjoy your holiday nights22 and potentially alleviate that hangover the next day.26

What is already known on this topic

Although asparagus is considered a delicacy, it tends to endow human urine with distinctive odor

The ability to smell the metabolites of asparagus consumption varies among people and across populations

What this study adds

This study provides important knowledge of the inheritance of asparagus anosmia, and genetic variation was identified near multiple olfactory receptor genes

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: supplemental methods

Supplementary table: supplemental tables 1-5

Supplementary figure: QQ plot to show distribution of the observed and expected P values of the different platforms used to generate the genetic data: (a) Affymetrix platform, (b) Illumina, and (c) combination of both platforms

Contributors: All authors conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript. SCM and EN contributed equally to this manuscript. PK and LAM share last authorship. LAM is guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (UM1 CA167552, R01 HL35464, UM1 CA186107, R01 CA49449, R01 HL034594, R01 HL088521); National Cancer Institute at the NIH training grant (NIH T32 CA09001 to SCM); and the Prostate Cancer Foundation (to LAM and JRR).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations, including asparagus growers, that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Furthermore, the authors do not avoid asparagus consumption. Some of the authors report asparagus anosmia; the non-anosmic wish to remain anonymous. However, the first and last authors admit they can both produce and detect the “filthy and disagreeable smell in the urine.”

Ethical approval: The study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health and Partners Healthcare.

Data sharing: Data from the genome wide association studies are provided on dbGAP (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gap), a database on genotypes and phenotypes.

Transparency: The lead author (LAM) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

We thank the participants of the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) for making this study possible and colleagues in the Transdisciplinary Prostate Cancer Partnership (www.topcapteam.org) for lively discussions around asparagus anosmia. The NHS Breast Cancer genome wide association study (GWAS) was performed as part of the cancer genetic markers of susceptibility initiative of the National Cancer Institute. The NHS/HPFS type 2 diabetes GWAS is a component of a collaborative project that includes 13 other GWAS funded as part of the Gene Environment-Association Studies under the National Institutes of Health genes, environment and health initiative. A special thanks to Sonja Swanson for her intellectual and humorous input.

References

- 1.Lémery L. A treatise of all sorts of foods: both animal and vegetable: also of drinkables: giving an account how to chuse the best sort of all kinds; of the good and bad effects they produce; the principles they abound with; the time, age, and constitution they are adapted to. Wherin their nature and use is explain’d according to the sentiments of the most eminent physicians and naturalists, antient and modern. T Osborne, 1745. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin B. Letter to the Royal Academy of Brussels, c. 1781.

- 3.Franklin B.Fart Proudly: Writings of Benjamin Franklin You Never Read in School. North Atlantic Books, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Proust M. Swann’s Way.Henry Holt, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- 5.White RH. Occurrence of S-methyl thioesters in urines of humans after they have eaten asparagus. Science 1975;189:810-1. 10.1126/science.1162354 pmid:1162354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allison AC, McWhirter KG. Two unifactorial characters for which man is polymorphic. Nature 1956;178:748-9. 10.1038/178748c0 pmid:13369530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lison M, Blondheim SH, Melmed RN. A polymorphism of the ability to smell urinary metabolites of asparagus. BMJ 1980;281:1676-8. 10.1136/bmj.281.6256.1676 pmid:7448566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell SC. Food idiosyncrasies: beetroot and asparagus. Drug Metab Dispos 2001;29:539-43.pmid:11259347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelchat ML, Bykowski C, Duke FF, Reed DR. Excretion and perception of a characteristic odor in urine after asparagus ingestion: a psychophysical and genetic study. Chem Senses 2011;36:9-17. 10.1093/chemse/bjq081 pmid:20876394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eriksson N, Macpherson JM, Tung JY, et al. Web-based, participant-driven studies yield novel genetic associations for common traits. PLoS Genet 2010;6:e1000993 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000993 pmid:20585627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindstrom S, Loomis S, Turman C, et al. A comprehensive survey of genetic variation in 20,691 subjects from four large cohorts. 2016. http://biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2016/10/25/083030.full.pdf. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/083030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Pe’er I, Yelensky R, Altshuler D, Daly MJ. Estimation of the multiple testing burden for genomewide association studies of nearly all common variants. Genet Epidemiol 2008;32:381-5. 10.1002/gepi.20303 pmid:18348202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang J, Ferreira T, Morris AP, et alConditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat Genet 2012;44:369-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet 2011;88:76-82. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011 pmid:21167468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cato the Elder. De Agri Cultura, 160 BC.

- 16.Apicius. De Re Coquinaria of Apicius.

- 17.Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB, et al. Folate and vitamin B6 from diet and supplements in relation to risk of coronary heart disease among women. JAMA 1998;279:359-64. 10.1001/jama.279.5.359 pmid:9459468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women. JAMA 2009;302:401-11. 10.1001/jama.2009.1060 pmid:19622819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim DH, Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, et al. Pooled analyses of 13 prospective cohort studies on folate intake and colon cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:1919-30. 10.1007/s10552-010-9620-8 pmid:20820900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Multivitamin use, folate, and colon cancer in women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:517-24. 10.7326/0003-4819-129-7-199810010-00002 pmid:9758570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salemme A, Togna AR, Mastrofrancesco A, et alAnti-inflammatory effects and antioxidant activity of dihydroasparagusic acid in lipopolysaccharide-activated microglial cells. Brain Res Bull 2016;120:151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.al-Nafzawi M. The Perfumed Garden of Sensual Delight, 15th century.

- 23.Doty RL, Applebaum S, Zusho H, Settle RG. Sex differences in odor identification ability: a cross-cultural analysis. Neuropsychologia 1985;23:667-72. 10.1016/0028-3932(85)90067-3 pmid:4058710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert AN, Greenberg MS, Beauchamp GK. Sex, handedness and side of nose modulate human odor perception. Neuropsychologia 1989;27:505-11. 10.1016/0028-3932(89)90055-9 pmid:2733823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stromberg J. Why Asparagus Makes Your Urine Smell. Secondary Why Asparagus Makes Your Urine Smell 2013. www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/why-asparagus-makes-your-urine-smell-49961252/?no-ist.

- 26.Kim BY, Cui ZG, Lee SR, et al. Effects of Asparagus officinalis extracts on liver cell toxicity and ethanol metabolism. J Food Sci 2009;74:H204-8. 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01263.x pmid:19895471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: supplemental methods

Supplementary table: supplemental tables 1-5

Supplementary figure: QQ plot to show distribution of the observed and expected P values of the different platforms used to generate the genetic data: (a) Affymetrix platform, (b) Illumina, and (c) combination of both platforms