Summary

Neutrophils, eosinophils and “classical” monocytes collectively account for ~70% of human blood leukocytes and are among the shortest-lived cells in the body1,2. Precise regulation of the lifespan of these myeloid cells is critical to maintain protective immune responses while minimizing the deleterious consequences of prolonged inflammation1,2. However, how the lifespan of these cells is strictly controlled remains largely unknown. Here, we identify a novel long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) that we termed Morrbid, which tightly controls the survival of neutrophils, eosinophils and “classical” monocytes in response to pro-survival cytokines. To control the lifespan of these cells, Morrbid regulates the transcription of its neighboring pro-apoptotic gene, Bcl2l11 (Bim), by promoting the enrichment of the PRC2 complex at the Bcl2l11 promoter to maintain this gene in a poised state. Notably, Morrbid regulates this process in cis, enabling allele-specific control of Bcl2l11 transcription. Thus, in these highly inflammatory cells, changes in Morrbid levels provide a locus-specific regulatory mechanism that allows for rapid control of apoptosis in response to extracellular pro-survival signals. As MORRBID is present in humans and dysregulated in patients with hypereosinophilic syndrome, this lncRNA may represent a potential therapeutic target for inflammatory disorders characterized by aberrant short-lived myeloid cell lifespan.

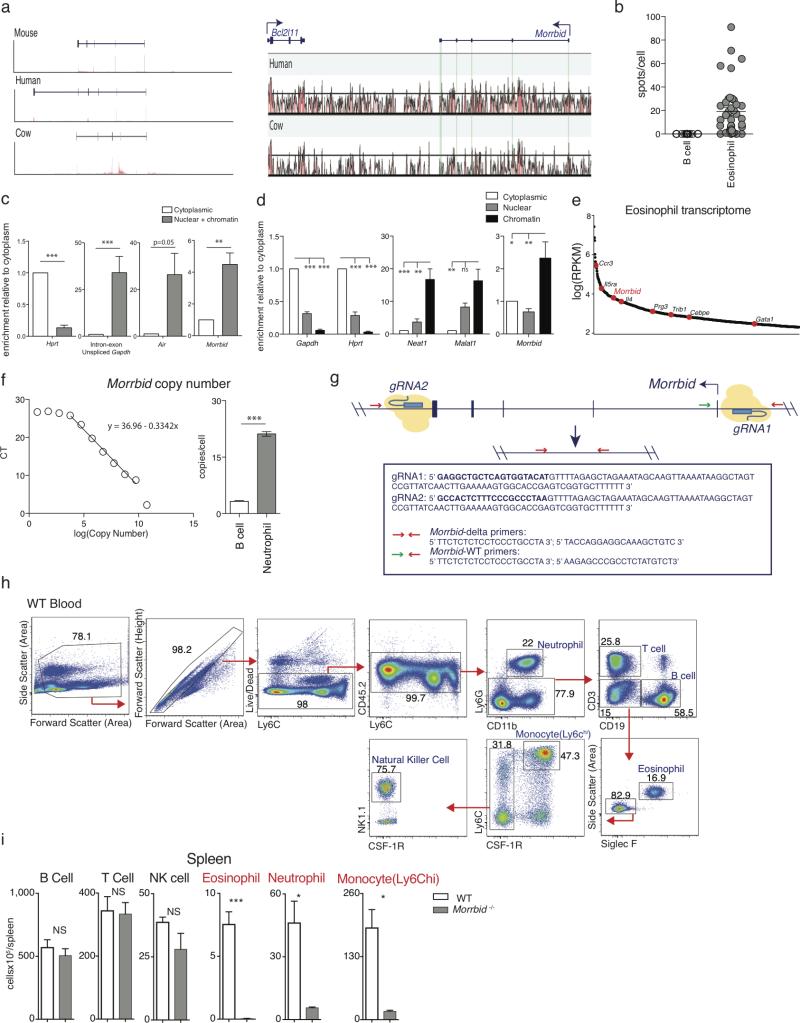

Neutrophils, eosinophils and Ly6Chi “classical” monocytes represent a first line of defense against nearly all pathogens1,2. Yet, these short-lived myeloid cells also contribute to the development of several inflammatory diseases1,2. Cytokines and metabolites tightly regulate the function and lifespan of these cells; however, how these cues are translated into an optimal cellular lifespan is largely unknown. Emerging evidence indicates that certain lncRNAs can integrate extracellular inputs with chromatin-modification pathways allowing cells to rapidly adapt to their environment3,4. As such, we investigated whether lncRNAs control the function or lifespan of short-lived myeloid cells in response to extracellular cues. We first analyzed multiple RNA-seq datasets for lncRNAs preferentially expressed by mature short-lived myeloid cells5,6. We identified an uncharacterized lncRNA (Gm14005) that we termed Morrbid (MyelOid Rna Regulator of Bim-Induced Death). Morrbid is conserved across species, contains 5 exons, is poly-adenylated, and localized predominately to the nucleus bound to chromatin (Fig. 1a-b, Extended Data Fig. 1a-d). Importantly, this lncRNA is highly and specifically expressed by mature eosinophils, neutrophils, and “classical” monocytes in both mice and humans (Fig. 1c-d, Extended Data Fig. 1e-f).

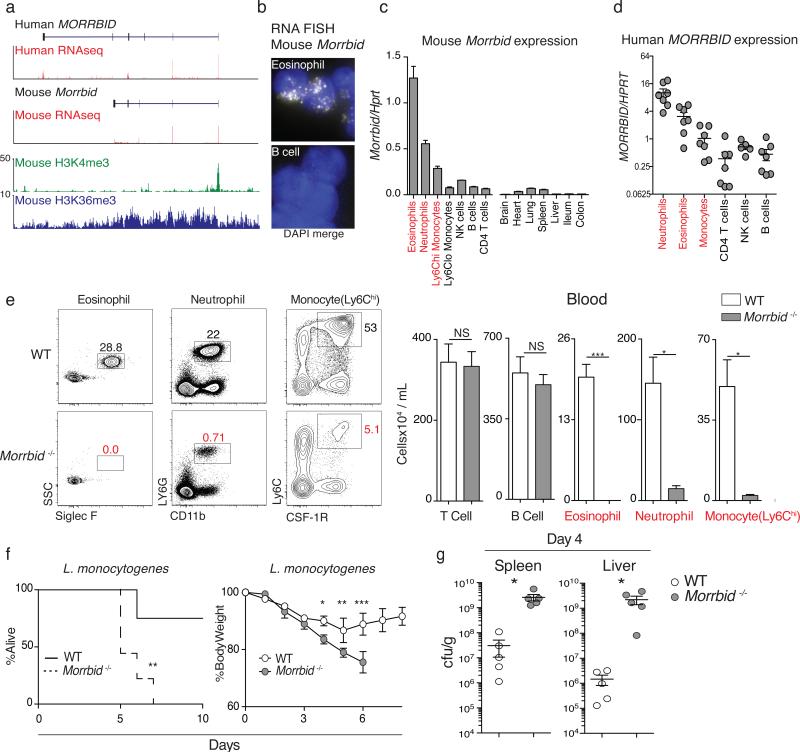

Figure 1. Long non-coding RNA Morrbid is a critical regulator of eosinophils, neutrophils, and Ly6Chi monocytes.

(a) Human neutrophil and mouse granulocyte normalized RNA-seq and ChIP-seq tracks at the Morrbid locus.

(b) Single molecule Morrbid RNA FISH.

(c) qPCR expression of mouse (n=3; representative of 3 independent experiments) and

(d) human Morrbid in indicated cell-types and tissues (n=7).

(e) WT and Morrbid-deficient flow-cytometry plots and absolute counts (n=3-5; representative of 7 independent experiments).

(f-g) L. monocytogenes infection of WT and Morrbid-deficient mice. (f) Survival and weight loss (n=9, representative of 3 independent experiments). (g) CFUs/g from indicated organs (n=5; representative of 3 independent experiments).

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test e,g, (right) f; Mantel-Cox test (left) f).

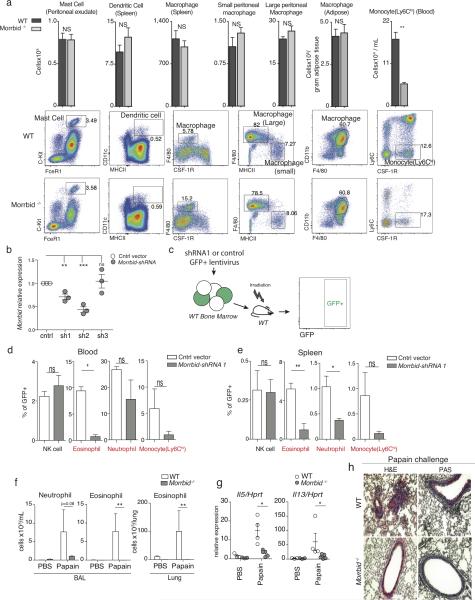

To investigate the role of Morrbid in vivo, we deleted the Morrbid locus to generate Morrbid-deficient mice (Extended Data Fig. 1g). Strikingly, and in accordance with the expression profile of Morrbid, we found that eosinophils, neutrophils, and Ly6Chi “classical” monocytes were drastically reduced in the blood and tissues of these mice (Fig. 1e, Extended Data Fig. 1h-i). This defect was highly specific to these three cell-types, as well as blood Ly6Clo monocytes (Extended Data Fig. 2a), which are suggested to be progeny of Ly6Chi monocytes7. All other lymphoid and myeloid cell types were unaffected (Extended Data Fig. 1i, 2a). Similarly, knockdown of Morrbid in vivo also led to a specific reduction in the frequency of short-lived myeloid cells in blood and spleen (Extended Data Fig. 2b-e). Finally, as these cells play a critical role in protective immunity and in the development of immunopathology, we found that Morrbid-deficent mice were highly susceptible to bacterial (L. monocytogenes) infection (Fig. 1f,g), and protected from eosinophil-driven allergic lung inflammation (Extended Data Fig. 2f-h). Altogether, these results support a critical and selective role for this lncRNA and potentially DNA elements within its locus in short-lived myeloid cell homeostasis.

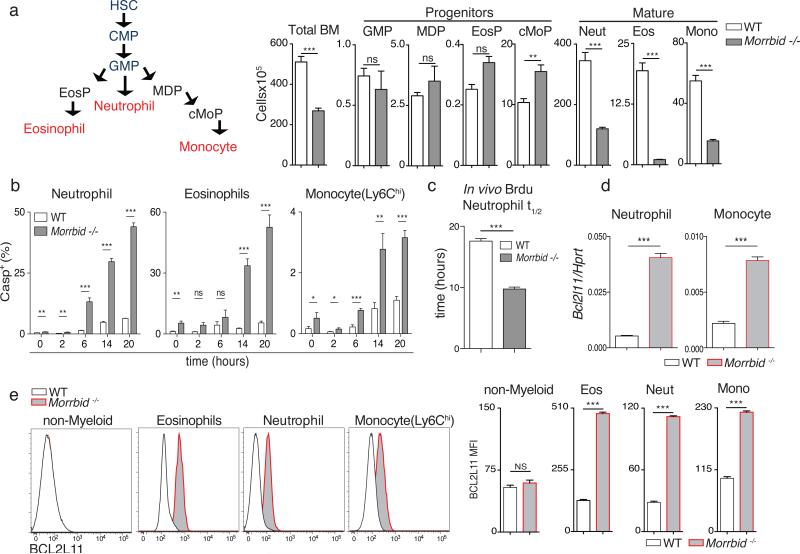

Figure 2. Morrbid controls eosinophil, neutrophil, and Ly6Chi monocyte lifespan.

(a) Schematic of short-lived myeloid cell development and absolute numbers of the indicated cell-types in bone marrow (BM) from WT and Morrbid-deficient mice (n=3-5; representative of 3 independent experiments).

(b) Frequency of Casp+ (Z-VAD-FMK+) in cultured BM cells (n=3 mice; representative of 2 independent experiments).

(c) Half-life of BrdU pulse-labeled neutrophils in blood in vivo (n=4 mice; representative of 3 independent experiments).

(d) Bcl2l11 qPCR expression in indicated cell-types sorted from BM (n=3; representative of 2 independent experiments).

(e) BCL2L11 protein expression assessed by flow-cytometry in indicated BM cell-types. (Left) Representative histograms. (Right) MFI quantification (n=3-5 mice, representative of 3 independent experiments).

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test)

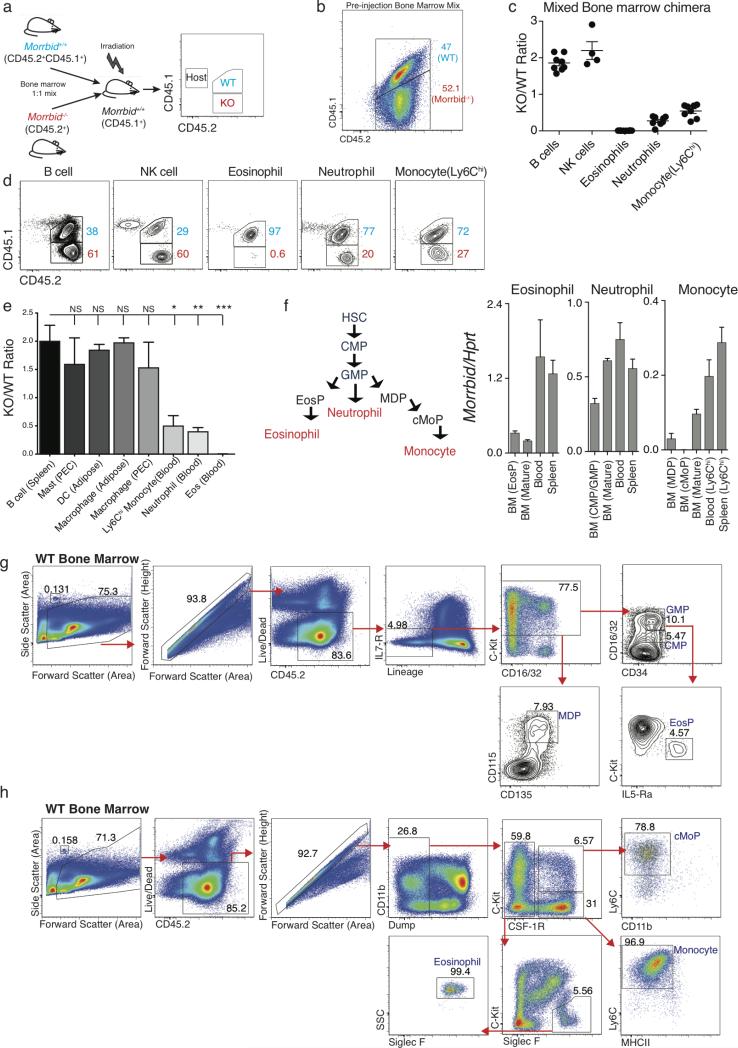

Eosinophils, neutrophils, and Ly6Chi monocytes originate from common progenitors in the bone marrow (BM)1,8, with extracellular cues driving the developmental programs needed to produce each of these cell types1,8. Using mixed BM chimeras, we found that Morrbid-deficient BM cells have a significant defect in the generation of short-lived myeloid cells (Extended Data Fig. 3a-e), indicating that Morrbid acts in a cell-intrinsic manner. We next sought to determine whether Morrbid regulates short-lived myeloid cell development. Early progenitors of each of these cell-types express low levels of Morrbid and its expression increases throughout development to reach maximal levels in fully mature eosinophils, neutrophils, and Ly6Chi monocytes (Extended Data Fig. 3f-h). In accordance with this pattern of expression, the progenitors of each of these cell-types were intact in Morrbid-deficient mice (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 3g-h). These results suggest that Morrbid regulates the frequency of mature eosinophils, neutrophils, and monocytes, but not their progenitors.

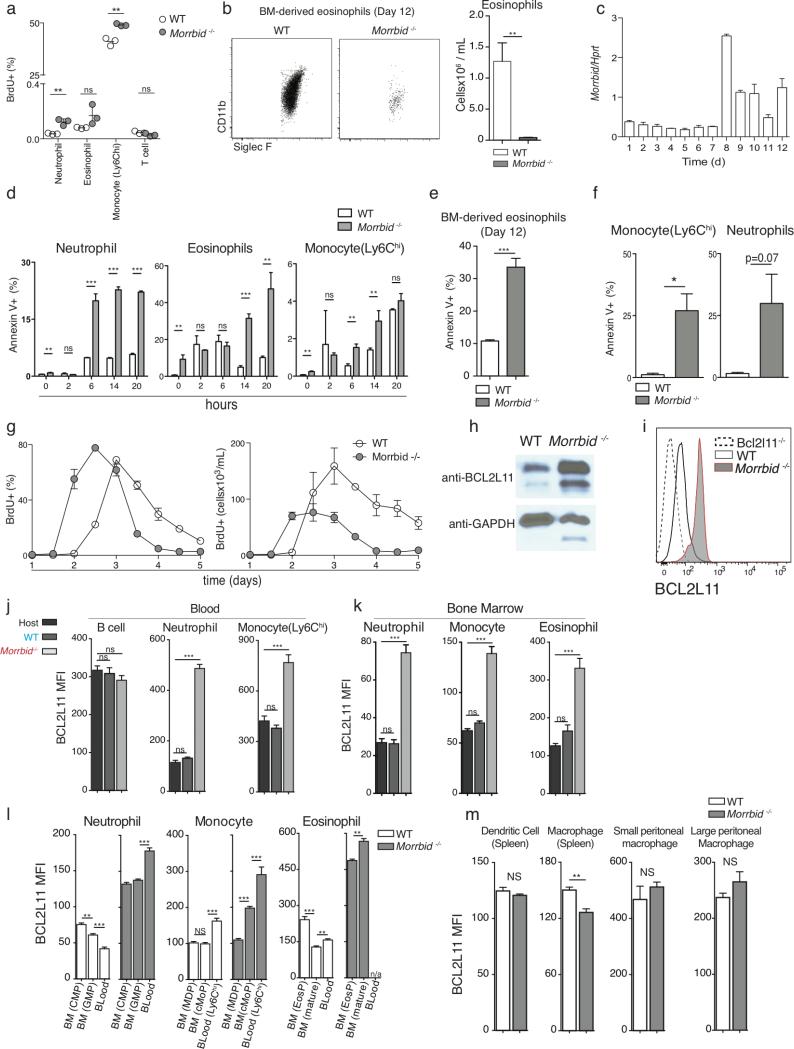

Mature populations of myeloid cells are controlled by several mechanisms, including homeostatic proliferation, trafficking, and cell death. We found no defects in homeostatic proliferation in Morrbid-deficient mice (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Mature short-lived myeloid cells are substantially reduced in the BM of Morrbid-deficient mice and there was a near absence of in vitro BM-differentiated eosinophils in the absence of this lncRNA9 (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Fig. 4b,c), suggesting that Morrbid controls a dominant process independent of cell trafficking. Strikingly, Morrbid-deficient eosinophils, neutrophils, and Ly6Chi monocytes were all highly prone to apoptosis in BM cultured ex vivo (Fig. 2b, Extended Data Fig. 4d). Furthermore, we observed significantly increased apoptosis in vitro in BM-derived eosinophils (Extended Data Fig. 4e), and in vivo during L. monocytogenes infection in the absence of Morrbid (Extended Data Fig. 4f). Given the close relationship between apoptosis and cellular lifespan, we hypothesized that Morrbid is a regulator of short-lived myeloid cell half-life. Using BrdU to label circulating neutrophils and determine their decay rate, we observed a ~2-fold decrease in the half-life of these cells (Fig. 2c, Extended Data Fig. 4g). These results indicate that Morrbid regulates short-lived myeloid cell lifespan through control of apoptosis.

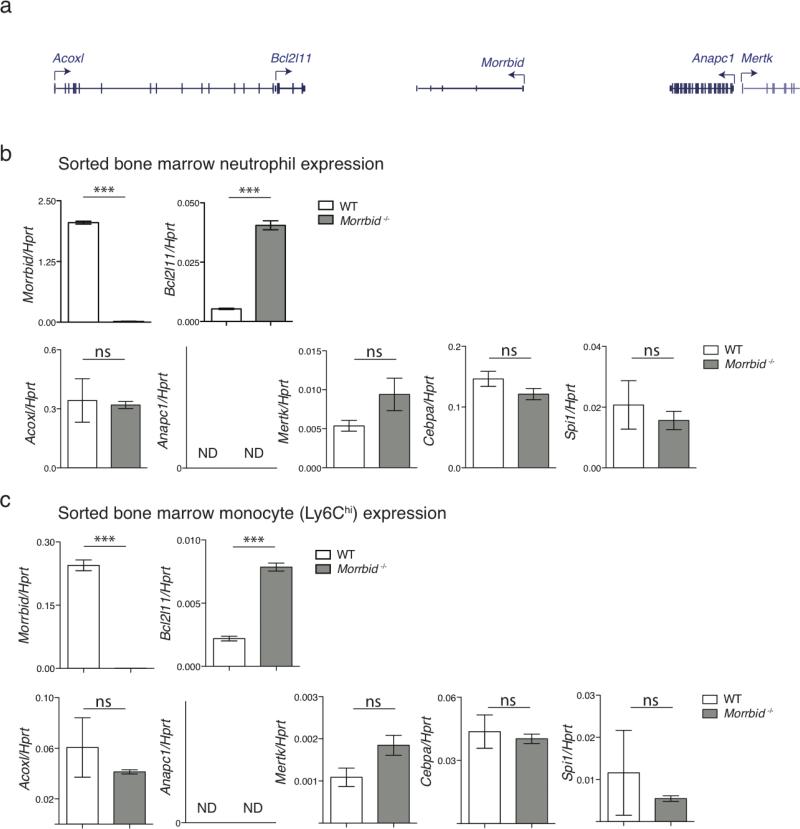

Some lncRNAs regulate the expression of neighboring genes10–13. The proapoptotic gene Bcl2l11 (Bim) is located ~150-kb downstream of Morrbid (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Bcl2l11 has been shown to be an important regulator of myeloid homeostasis14,15. Thus, we reasoned that Morrbid regulates short-lived myeloid cell lifespan through its control of Bcl2l11 expression. Indeed, the protein and mRNA levels of Bcl2l11 were dramatically elevated in eosinophils, neutrophils, and Ly6Chi monocytes from Morrbid-deficient mice (Fig. 2d-e, Extended Data Fig. 4h-k). In concordance with the pattern of Morrbid expression, Bcl2l11 was maximally elevated in the mature state of each of these cell lineages in Morrbid-deficient mice (Extended Data Fig. 4l), and was not dysregulated in other myeloid and lymphoid cell populations (Extended Data Fig. 4m). Importantly, key myeloid lineage transcription factors and other genes neighboring this lncRNA were largely unaffected in the absence of Morrbid (Extended Data Fig. 5a-c). These results suggest that Morrbid represses Bcl2l11 expression in short-lived myeloid cells.

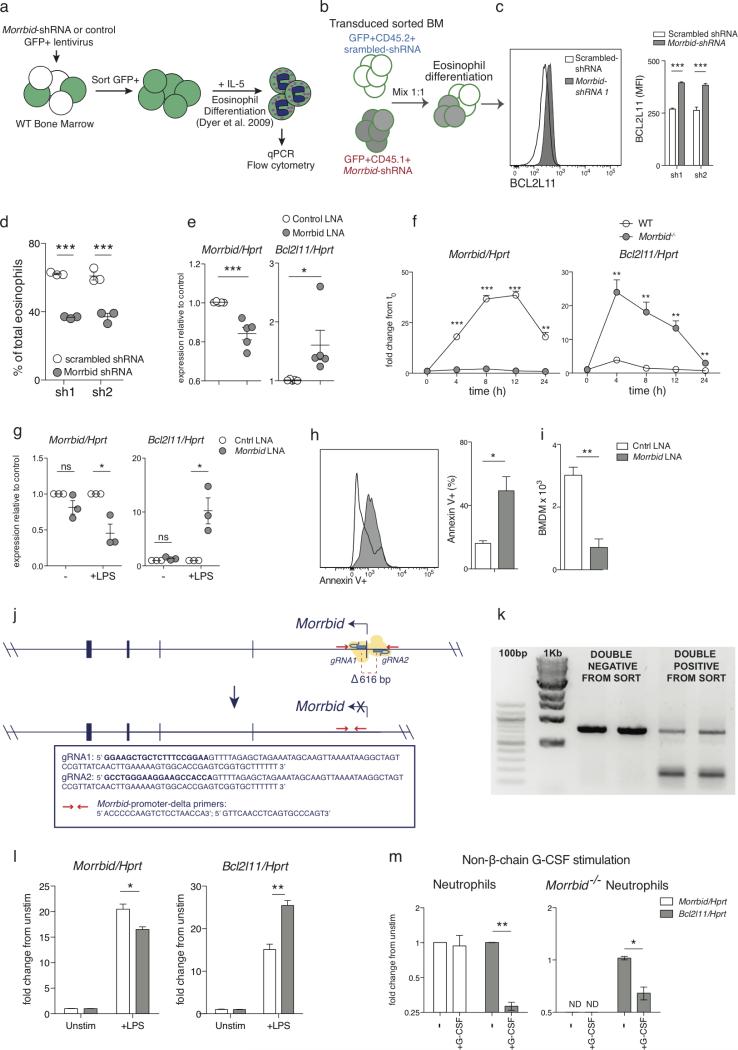

To specifically address the role of Morrbid RNA in the regulation of Bcl2l11 expression, we first established an in vitro eosinophil culture system in which we could study the function of Morrbid RNA in the absence of genetic disruptions (Extended Data Fig. 6a)9. Using this system, we found that shRNA-mediated knockdown of Morrbid RNA results in a significant elevation in BCL2L11, which was accompanied by a substantial decrease in eosinophil survival (Figure 3a-c, Extended Data Fig. 6b-d). We observed similar results using transfection of locked nucleic acids (LNAs) as an independent knockdown technique (Extended Data Fig. 6e). We next sought to corroborate these results in a different cell-type within the myeloid cell lineage. Interestingly, we found that lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated BM-derived macrophages (BMDMs) highly upregulated Morrbid (Extended Data Fig. 6f). Notably, LNA knockdown of Morrbid, deletion of Morrbid's promoter, or deletion of its locus in LPS stimulated BMDMs resulted in a striking increase in Bcl2l11 expression and apoptosis (Extended Data Fig. 6f-l). Altogether, these results indicate that Morrbid RNA is a critical regulator of Bcl2l11 expression and short-lived myeloid cell survival.

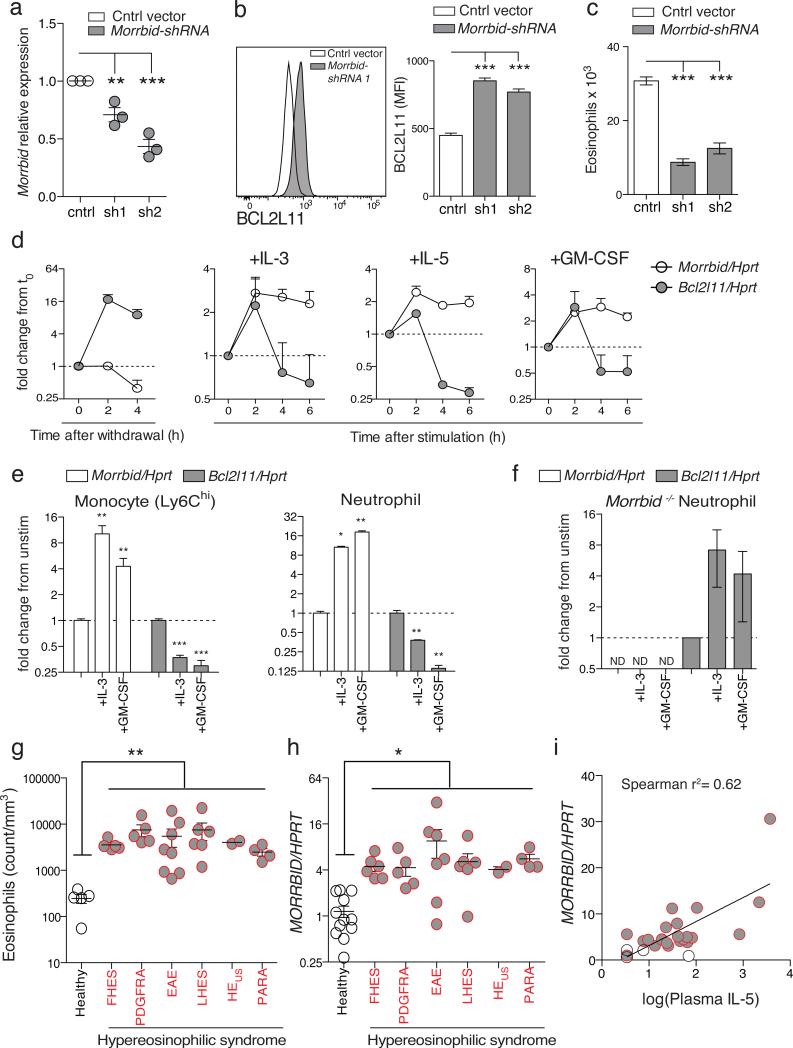

Figure 3. Pro-survival cytokines repress pro-apoptotic Bcl2l11 through induction of Morrbid RNA.

(a-c) Bone marrow (BM)-derived eosinophils transduced with control or Morrbid-specific shRNAs. (a) Morrbid qPCR expression. (b) BCL2L11 protein expression and (c) absolute eosinophil counts (n=3 mice per group, representative of 2 independent experiments).

(d) Morrbid and Bcl2l11 qPCR expression in BM-derived eosinophils following withdrawal/stimulation with indicated cytokines (n=3 mice, representative of 2 independent experiments).

(e-f) Morrbid and Bcl2l11 qPCR expression in (e) WT and (f) Morrbid-deficient sorted BM cell-types stimulated with indicated cytokines. (n=3-4 mice, representative of 3 independent experiments).

(g-i) MORRBID expression in human hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES). (g) Absolute eosinophil count, (h) purified eosinophil MORRBID qPCR expression, and (i) correlation between log(plasma IL-5) and MORRBID expression. (each dot represents one individual; n=2-12 per disease group). Familial HES (FHES), PDGFRA+ HES (PDGFRA), episodic angioedema and eosinophilia (EAE), lymphocytic variant HES (LHES), HES of undetermined significance (HEus), and parasitic infection (PARA).

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test a-h, Spearman's correlation i).

Pro-survival cytokines can potently influence the lifespan of immune cells. One well-described mechanism of this control is through the repression of Bcl2l1115,16. We hypothesized that cytokines from the common β-chain receptor family (IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF), which are known to promote the survival of eosinophils, neutrophils, and Ly6Chi monocytes, regulate Bcl2l11 expression through the induction of Morrbid. To test this hypothesis, we first withdrew cytokines from cultured BM-derived eosinophils and observed a loss of Morrbid expression and an increase in Bc2l11 levels (Fig. 3d). Subsequent addition of IL-5, IL-3, or GM-CSF induced Morrbid expression, which was accompanied by Bcl2l11 repression (Fig. 3d). Similarly, ex-vivo β-chain cytokine stimulation, but not G-CSF stimulation, significantly induced Morrbid and a corresponding repression of Bcl2l11 in neutrophils and Ly6Chi monocytes (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 6m). Importantly, Morrbid-deficient neutrophils were unable to inhibit Bcl2l11 expression upon addition of β-chain cytokines (Fig. 3f). These results suggest that β-chain cytokines repress Bcl2l11 expression in short-lived myeloid cells in a Morrbid-dependent manner.

Dysregulated immune cell survival is central to many human hematological and inflammatory diseases. Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is a group of disorders characterized by eosinophilia and a wide range of clinical manifestations17. Several HES subtypes have been associated with increased production or responsiveness to IL-517. We therefore reasoned that eosinophils from HES patients would overexpress MORRBID, and that this overexpression would positively correlate with IL-5 levels. We screened patients with varied subtypes of HES (Fig. 3g), and found that eosinophils from these patients expressed significantly higher levels of MORRBID than that of healthy controls (Fig. 3h). Additionally, we observed that MORRBID expression in eosinophils was positively correlated with plasma IL-5 levels (Fig. 3i). These results suggest a potential role for MORRBID in HES and other inflammatory diseases characterized by high levels of β-chain cytokines and altered short-lived myeloid cell lifespan.

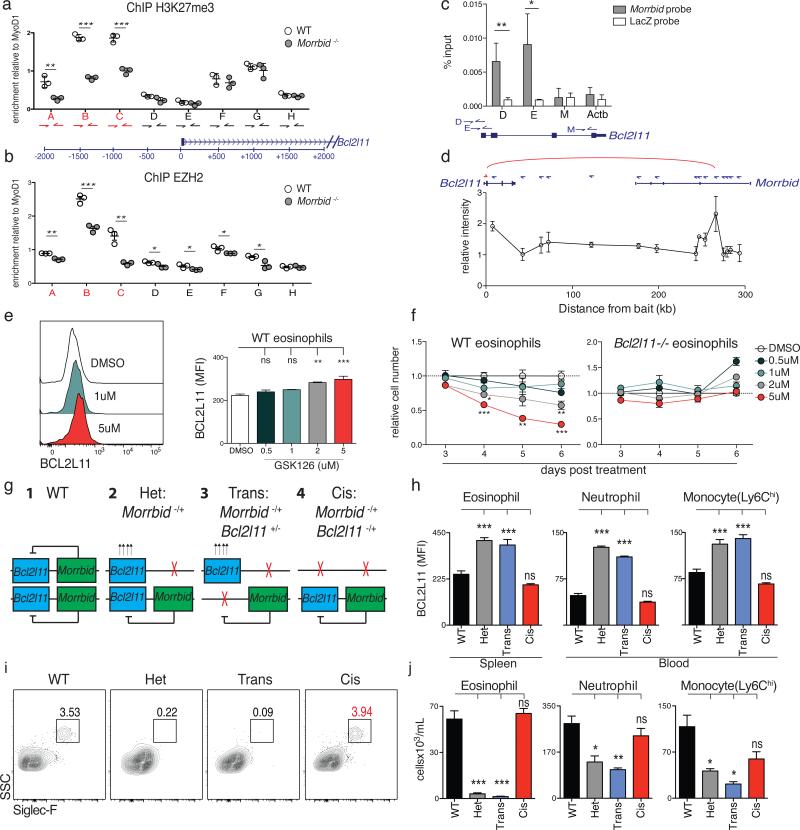

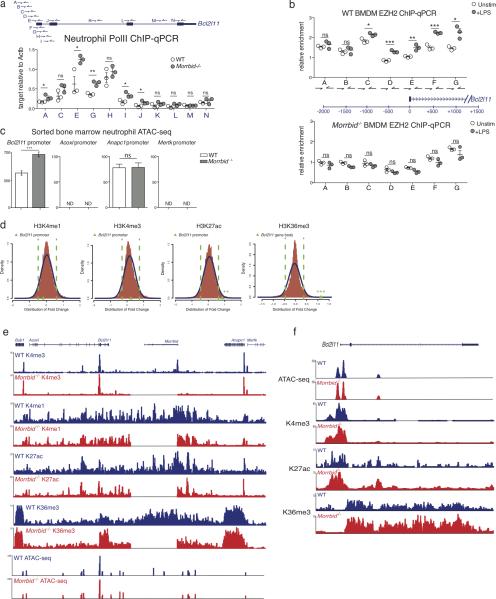

Genes that require both tight regulation and the ability to be rapidly activated frequently harbor activating (H3K4me3) and repressive (K3K27me3) histone marks in their promoters, termed bivalent promoters18. The Bcl2l11 gene has been previously described to have a bivalent promoter, which allows this pro-apoptotic gene to be maintained in a poised state19. A number of lncRNAs have been described to repress gene expression by promoting the enrichment of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) at target genes, which in turn catalyzes the deposition of H3K27me320,21. We therefore hypothesized that Morrbid represses Bcl2l11 expression and prevents short-lived myeloid cell apoptosis by promoting PRC2 enrichment and H3K27me3 deposition at the bivalent promoter of Bcl2l11.

To test this hypothesis, we first performed ChIP-qPCR for total polymerase II (Pol-II), H3K27me3, and the PRC2 subunit EZH2 in neutrophils from WT and Morrbid-deficient mice. In line with the elevated levels of Bcl2l11 in Morrbid-deficient cells, we found that Pol-II occupancy was significantly increased (Extended Data Fig. 7a), and the levels of H3K27me3 and EZH2 were drastically reduced at the promoter of Bcl2l11 in the absence of Morrbid (Fig. 4a-b). We next asked whether the induction of Morrbid expression promotes the accumulation of PRC2 at the Bcl2l11 promoter. Using the BMDM system in which Morrbid is induced upon LPS stimulation, we found that Morrbid levels and EZH2 occupancy at the Bcl2l11 promoter concurrently increase in a Morrbid-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Finally, using ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq, we did not detect changes in the activating histone marks H3K4me1 and H3K4me3, and only a modest increase in chromatin accessibility at the Bcl2l11 promoter in the absence of Morrbid (Extended Data Fig. 7c-f). Altogether, these results indicate that Morrbid represses Bcl2l11 expression in short-lived myeloid cells by promoting the deposition of H3K27me3 at the bivalent promoter of Bcl2l11.

Figure 4. Morrbid represses Bcl2l11 in cis by maintaining its bivalent promoter in a poised state.

(a-b) ChIP-qPCR for (a) H3K27me3 and (b) EZH2 at the Bcl2l11 promoter in sorted bone marrow (BM) neutrophils (dot represents 1-2 pooled mice).

(c) ChIRP-qPCR of Morrbid RNA occupancy (average of 3 independent experiments).

(d) 3C of the Bcl2l11 promoter and indicated genomic regions. (average of 3 independent experiments).

(e-f) WT and Bcl2l11-deficient BM-derived eosinophils treated with the EZH2 inhibitor GSK126. (e) BCL2L11 protein expression on treatment day 5. (f) Number of cells relative to DMSO treatment control (n=3 mice per dose, representative of 2 independent experiments).

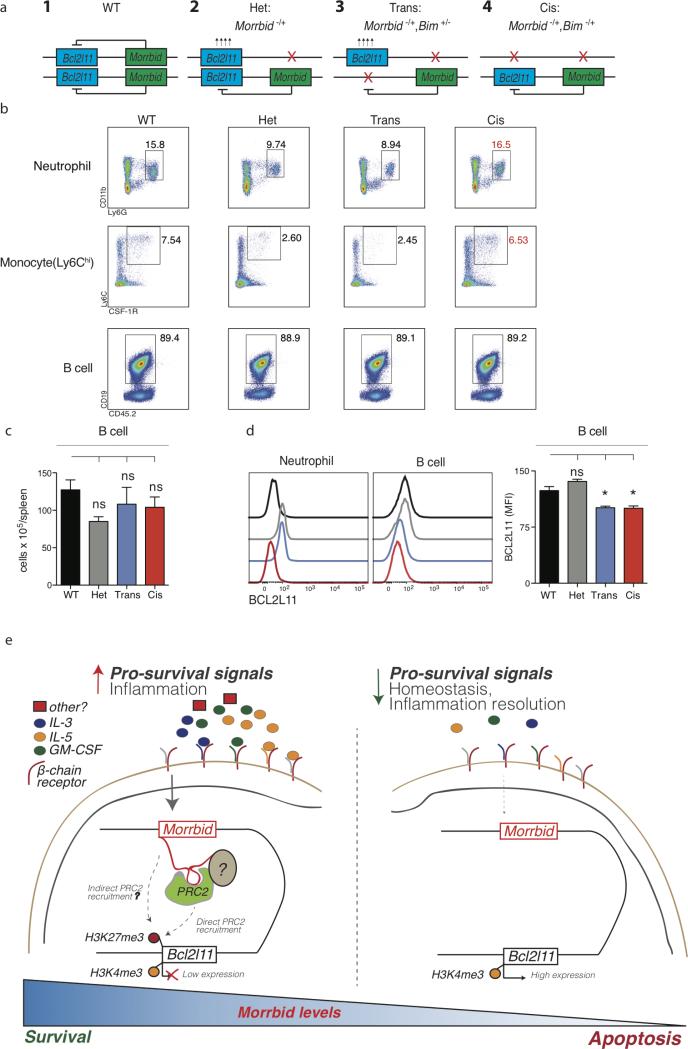

(g-j) Allele-specific combinations of Morrbid- and Bcl2l11-deficient mice. (g) Schema.

(h) BCL2L11 MFI of indicated cell-types. (i) Representative flow-cytometry of blood eosinophils. (j) Absolute counts of indicated splenic cell-types (n=3-9 mice per group).

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test a,b,c; oneway Anova with Tukey post hoc e,f,h,j).

LncRNAs have been suggested to promote the recruitment of PRC2 to target genes through direct lncRNA-PRC2 interactions or indirect mechanisms 11,20–24. To further understand the mechanism by which Morrbid promotes PRC2 enrichment at the Bcl2l11 promoter, we first examined whether Morrbid RNA associates with PRC2. Using a recently generated EZH2 PAR-CLIP dataset22, we found that Morrbid associates with EZH2 (Extended Data Fig. 8a). To further support this association, we performed RNA immunoprecipitation against EZH2 in myeloid cells and found that Morrbid significantly co-immunoprecipitates with this PRC2 subunit (Extended Data Fig. 8b). We next asked whether Morrbid RNA associates with chromatin regions within the Bcl2l11 promoter with which PRC2 also associates. We performed chromatin isolation by RNA purification (ChIRP)-qPCR in LPS-treated BMDMs. Using DNA probes that specifically and robustly retrieved Morrbid RNA (Extended Data Fig. 8c), we found that Morrbid association with chromatin was significantly enriched at the Bcl2l11 promoter (Fig. 4c). Finally, we asked how Morrbid RNA comes into proximity of the Bcl2l11 promoter. A number of lncRNA genes have been reported to loop into proximity with the genes that they regulate10–13,25; thus, we reasoned that the Morrbid and Bcl2l11 loci interact with one another through DNA looping. Using chromosome conformation capture (3C), we indeed observed a long-distance association between Bcl2l11 and the Morrbid locus in short-lived myeloid cells (Fig. 4d, Extended Data Fig. 8d). Altogether, these results suggest a model in which Morrbid proximity to Bcl2l11, mediated through DNA looping, enables Morrbid RNA to promote PRC2 enrichment within the Bcl2l11 promoter through direct Morrbid-PRC2 interactions and potentially through additional indirect mechanisms.

Our findings suggest an important role for PRC2 in Morrbid-dependent repression of Bcl2l11. Yet, whether short-lived myeloid cell survival depends on PRC2-mediated transcriptional repression of Bcl2l11 is not known. We cultured eosinophils in the presence of a specific inhibitor of EZH2, GSK126. We observed a dose-dependent increase in BCL2L11 and eosinophil apoptosis upon PRC2 inhibition (Fig. 4e, Extended Data Fig. 8e-f). Importantly, Bcl2l11-deficient eosinophils were resistant to cell death following abrogation of PRC2 activity (Fig. 4f, Extended Data Fig. 8e-f). Altogether, these results demonstrate that PRC2 regulates short-lived myeloid cell survival specifically through repression of Bcl2l11 expression, further supporting a critical role for Morrbid in the regulation of the lifespan of these highly inflammatory cells.

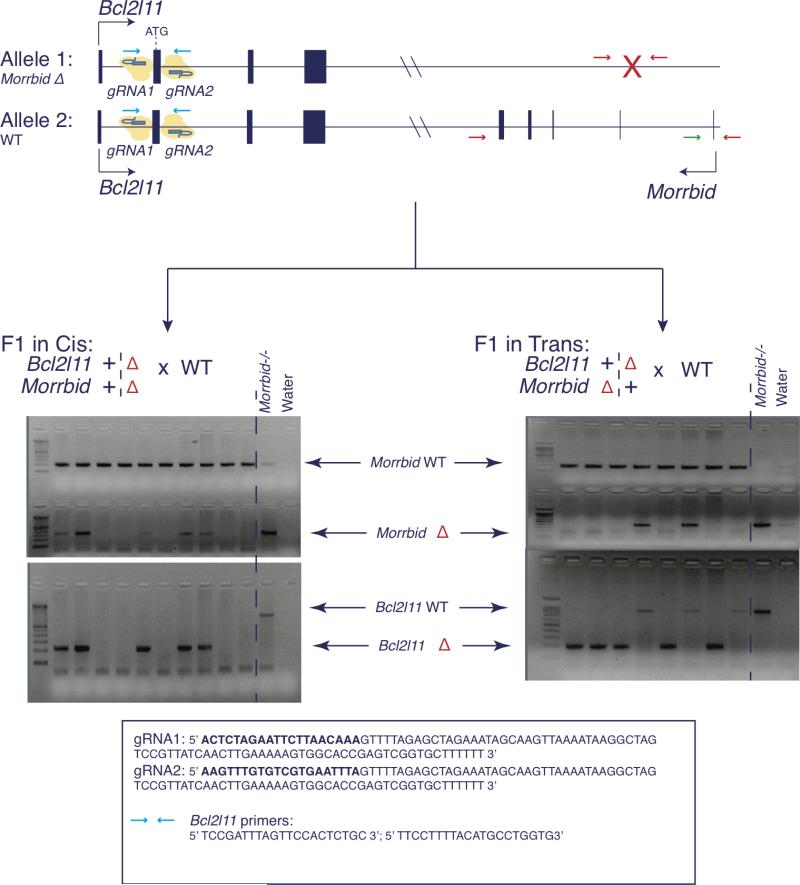

Finally, we found that Morrbid-heterozygous mice largely recapitulated the phenotype of mice lacking both alleles of Morrbid (Extended Data Fig. 8g). In light of this dominant heterozygous phenotype and the observed Morrbid-Bcl2l11 DNA loop, we hypothesized that Morrbid functions in cis to repress Bcl2l11. As such, we expected that deletion of Bcl2l11 on the same chromosome as that of the Morrbid-deficient allele will normalize Bcl2l11 expression in short-lived myeloid cells and rescue their numbers, but that deletion of Bcl2l11 on the opposite chromosome would not (Fig. 4g). We therefore generated all permutations of Morrbid and Bcl2l11 double-heterozygous mice (Extended Data Fig. 9). Strikingly, deletion of Bcl2l11 in cis but not in trans of the Morrbid-deficient allele normalized Bcl2l11 expression (Fig. 4h) and rescued short-lived myeloid cell numbers (Fig. 4i-j, Extended Data Fig. 10a-b). Other cell-types were largely unaltered in these genetic backgrounds (Extended Data Fig. 10b-d). This complete rescue in cis double-heterozygous mice indicates that Morrbid acts in an allele-specific manner to regulate Bcl2l11 expression and short-lived myeloid cell lifespan.

Here we show that Morrbid integrates extracellular signals to control the lifespan of eosinophils, neutrophils, and monocytes through allele-specific suppression of Bcl2l11 expression (Extended Data Fig. 10e). As this lncRNA is present in humans and dysregulated in patients with HES, a better understanding of how Morrbid RNA and potentially DNA elements within its locus regulate Bcl2l11 may provide new therapeutic approaches for several human inflammatory diseases. Finally, our results demonstrate that lncRNAs can function as highly cell-type specific local effectors of extracellular cues to control immunological processes that require rapid and strict regulation.

Methods

Mice

All mice were bred and maintained under pathogen-free conditions at an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited animal facility at the University of Pennsylvania or Yale University. Mice were housed in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under an animal study proposal approved by an institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male and female mice between 4 and 12 weeks of age were used for all experiments. Littermate controls were used whenever possible.

C57BL/6 (WT) and B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/Boy (B6.SJL) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. We generated Morrbid-deficient mice and the in cis and in trans double heterozygous mice (Morrbid+/−, Bcl2l11+/−) mice using the CRISPR/Cas9 system as previously described26. In brief, to generate Morrbid-deficient mice, single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) were designed against regions flanking the first and last exon of the Morrbid locus (Extended Data Fig. 1g). Cas9-mediated double-stranded DNA breaks resolved by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) ablated the intervening sequences containing Morrbid in C57BL/6N one-cell embryos. The resulting founder mice were Morrbid−/+, which were then bred to wild-type (WT) C57BL/6N and then intercrossed to obtain homozygous Morrbid−/− mice. One Morrbid-deficient line was generated. To control for potential off-target effects, mice were crossed for at least 5 generations to WT mice and then intercrossed to obtain homozygosity. Littermate controls were used when possible throughout all experiments.

To generate the in cis and in trans double heterozygous mice (Morrbid+/−, Bcl2l11+/−) mice, we first obtained mouse one-cell embryos from a mating between Morrbid−/− female mice and WT male mice. As such, the resulting one-cell embryos were heterozygous for Morrbid (Morrbid+/−). We then micro-injected sgRNAs designed against intronic sequences flanking the second exon of Bcl2l11, which contains the translational start site/codon, into Morrbid−/+ one-cell embryos (Extended Data Fig. Fig. 9). Cas9-mediated double-stranded DNA breaks resolved by NHEJ ablated the intervening sequences containing the second exon of Bcl2l11 in Morrbid+/− (C57BL/6N) one-cell embryos, generating founder mice that were heterozygous for both Bcl2l11 and Morrbid (Bcl2l11+/−; Morrbid−/+). Founder heterozygous mice were then bred to WT C57BL/6N to interrogate for the segregation of the Morrbid-deficient and Bcl2l11-defient alleles (Extended Data Fig. 9). Pups that segregated such alleles were named in trans and pups that did not segregate were labeled in cis. One line of in cis and in trans double heterozygous mice (Bcl2l11+/−; Morrbid−/+) lines were generated. To control for potential off-target effects, mice were crossed for at least 5 generations to WT (C57BL/6N) mice (for in cis) and to Morrbid−/− mice (for in trans) to maintain heterozygosity. To determine genetic rescue, samples from mice containing different permutations of Morrbid and Bcl2l11 alleles (Fig. 4g-j) were analyzed in a blinded manner by a single investigator not involved in the breeding or coding of these samples.

Flow cytometry staining, analysis, and cell sorting

Cells were isolated from the indicated tissues (blood, spleen, bone marrow, peritoneal exudate, adipose tissue). Red blood cells were lysed with ACK. Single-cell suspensions were stained with CD16/32 and with indicated fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies. If run live, cells were stained with 7-AAD (7-amino-actinomycin D) to exclude non-viable cells. Otherwise, prior to fixation, Live/Dead Fixable Violet Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen) was used to exclude non-viable cells. Active caspase staining using Z-VAD-FMK (CaspGLOW, eBiosciences) was performed according to the manufacturer's specifications. Apoptosis staining by annexin V+ (Annexin V Apoptosis Detection kit) was performed according to the manufacturer's recommendations. BrdU staining was performed using BrdU Staining Kit (eBioscience) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. For BCL2L11 staining, cells were fixed for 15 min in 2% formaldehyde solution, and permeabilized with flow cytometry buffer supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100. All flow cytometry analysis and cell-sorting procedures were done at the University of Pennsylvania Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting Facility using BD LSRII cell analyzers and a BD FACSAria II sorter running FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). FlowJo software (v. 10 TreeStar) was used for data analysis and graphic rendering. All fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Western blotting

1 ×106 WT and Morrbid-deficient neutrophils sorted from mouse bone marrow were assayed for BCL2L11 protein expression by Western blotting (Bim C34C5 Rabbit mAb, Cell Signaling) as previously described.

ChIP-qPCR

2 ×106 WT and Morrbid-deficient neutrophils sorted from mouse bone marrow were cross-linked in a 1% Formaldehyde solution for 5 min at room temperature while rotating. Crosslinking was stopped by adding glycine (0.2M in 1x PBS) and incubating on ice for 2 min. Samples were spun at 2500g for 5 min at 4°C and washed 4 times with 1x PBS. The pellets were flash frozen and stored at −80°C. Cells were lysed, and nuclei were isolated and sonicated for 8 min using a Covaris S220 (105 Watts, 2% Duty Cycle, 200 cycles per burst) to obtain approximately 200–500 bp chromatin fragments. Chromatin fragments were precleared with protein G magnetic beads (New England BioLabs) and incubated with pre-bound anti-H3K27me3 (Qiagen), anti-EZH2 (eBiosciences), or Mouse IgG1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody-protein G magnetic beads overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed once in low-salt buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.1, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS), twice in high-salt buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.1, 2 mM EDTA, 500 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS), once in LiCl buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.1, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25 mM LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% deoxycholic acid) and twice in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8. 0, 1 mM EDTA). Washed beads were eluted twice with 100 μL of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3) and de-crosslinked (0.1 mg/ml RNase, 0.3 M NaCl and 0.3 mg/ml Proteinase K) overnight at 65°C. The DNA samples were purified with Qiaquick PCR columns (Qiagen). qPCR was carried out on a ViiA7 Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher) using the SYBR Green detection system and indicated primers. Expression values of target loci were directly normalized to indicated positive control loci, such as MyoD1 for H3K27me3 and EZH2 ChIP analysis, and Actb for Pol II ChIP analysis. ChIP-qPCR primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

ATAC-seq preparation, sequencing, and analysis

50,000 WT and KO cells, in triplicate, were spun at 500g for 5 min at 4°C, washed once with 50 μL of cold 1X PBS and centrifuged in the same conditions. Cells were resuspended in 50 μL of ice cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630). Cells were immediately spun at 500g for 10 min at 4°C. Lysis buffer was carefully pipetted away from the pellet, which was then resuspended in 50 μL of the transposition reaction mix (25ul 2x TD buffer, 2.5 μL Tn5 Transposase (Illumina), 22.5 μL nuclease-free water) and then incubated at 37°C for 30 min. DNA purification was performed using a Qiagen MinElute kit and eluted in 12 μL of Elution buffer (10mM Tris buffer, pH8.0). To amplify library fragments, 6 μL of the eluted DNA was mixed with NEBnext High-Fidelity 2x PCR Master Mix, 25uM of customized Nextera PCR primers 1 and 2 (Supplementary Table 1), 100x SYBR Green I and used in PCR as follow: 72°C for 5min; 98°C for 30s; and thermocycling 4 times at 98°C for 10 s; 63°C for 30 s; 72°C for 1 min. 5ul of the 5 cycles PCR amplified DNA was used in a qPCR reaction to estimate the additional number of amplification cycles. Libraries were amplified for a total of 10–11 cycles and were then purified using a Qiagen PCR Cleanup kit and eluted in 30ul of Elution buffer. The libraries were quantified using qPCR and bioanalyzer data, and then normalized and pooled to 2nM. Each 2nM pool was then denatured with a 0.1N NaOH solution in equal parts then further diluted to form a 20pM denatured pool. This pool was then further diluted down to 1.8 pM for sequencing using the NextSeq500 machine on V2 chemistry and sequenced on a 1 x 75 bp Illumina NextSeq flow cell.

ATAC sequencing cells was done on Illumina NextSeq at a sequencing depth of ~40-60 million reads per sample. Libraries were prepared in triplicates. Raw reads were deposited under GSE85073. 2×75 bp paired-end reads were mapped to the mouse mm9 genome using ‘bwa’ algorithm with ‘mem’ option. Only reads that uniquely mapped to the genome were used in subsequent analysis. Duplicate reads were eliminated to avoid potential PCR amplification artifacts and to eliminate the high numbers of mtDNA duplicates observed in ATAC-seq libraries. Post-alignment filtering resulted in ~26-40 million uniquely aligned singleton reads per library and the technical replicates were merged into one alignment BAM file to increase the power of open chromatin signal in downstream analysis. Depicted tracks were normalized to total read depth. ATAC-seq enriched regions (peaks) in each sample was identified using MACS2 using the below settings:

MACS2-2.1.0.20140616/bin/macs2 callpeak -t <input tag file> -f BED -n <output peak file> -g ‘mm’ --nomodel --shift -100 --extsize 200 -B --broad

ChIP-seq preparation, sequencing, and analysis

10 ×106 WT and KO mice Neutrophils were cross-linked in a 1% Formaldehyde solution for 10 min at room temperature while rotating. Crosslinking was stopped by adding glycine (0.2M in 1x PBS) and incubating on ice for 2 min. Samples were spun at 2500g for 5 min at 4°C and washed 4 times with 1x PBS. The pellets were flash frozen and stored at −80°C. Cells were lysed and sonicated (Branson Sonifier 250) for 9 cycles (30% amplitude, time: 20 s on, 1 min off). Lysates were spun at 14,000rpm for 10 min at 4°C and resuspended in 3ml of lysis buffer. A sample of 100 μL was kept aside as input and the rest of the samples were divided by the number of antibodies to test. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed with 10ug of antibody-bound beads (anti-H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K4me1, H3K36me3 (Abcam) and anti-rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz), Dynal Protein G magnetic beads (Invitrogen)) and incubated overnight at 4°C. Bead-bound DNA was washed, reverse cross-linked and eluted overnight at 65°C, shaking at 950rpm. Beads were removed using a magnetic stand and eluted DNA was treated with RNase A (0.2ug/μL) for 1h at 37°C shaking at 950rpm, then with proteinase K (0.2ug/μL) for 2 h at 55°C. 30ug of glycogen (Roche) and 5M of NaCl were adding to the samples. DNA was extracted with 1 volume of phenol:chlorofrom:isoamyl alcohol and washed out with 100% ethanol. Dried DNA pellets were resuspended in 30 μL of 10mM Tris HCl pH8.0, and DNA concentrations were quantified using Qubit. Starting with 10 ng of DNA, ChIP-seq libraries were prepared using the KAPA Hyper Prep Kit (Kapa Biosystems, Inc., Wilmington, MA) with 10 cycles of PCR. The libraries were quantified using qPCR and bioanalyzer data then normalized and pooled to 2nM. Each 2nM pool was then denatured with a 0.1N NaOH solution in equal parts then further diluted to form a 20pM denatured pool. This pool was then further diluted down to 1.8 pM for sequencing using the NextSeq500 machine on V2 chemistry and sequenced on a 1 × 75 bp Illumina NextSeq flow cell.

ChIP sequencing was done on an Illumina NextSeq at a sequencing depth of ~30-40 million reads per sample. Raw reads were deposited under GSE85073. 75 bp single end reads were mapped to the mouse mm9 genome using ‘bowtie2’ algorithm. Duplicate reads were eliminated to avoid potential PCR amplification artifacts and only reads that uniquely mapped to the genome were used in subsequent analysis. Depicted tracks were normalized to control IgG input sample. ChIP-seq enriched regions (peaks) in each sample was identified using MACS2 using the below settings:

MACS2-2.1.0.20140616/bin/macs2 callpeak -t <ChIP tag file> -c <control tag file> -f BED -g ‘mm’ --nomodel –extsize=250 --bdg –-broad -n <output peak file>

RIP-qPCR

107 immortalized bone marrow-derived macrophages (iBMDMs) were harvested by trypsinization and resuspended in 2 ml PBS, 2 ml nuclear isolation buffer (1.28 M sucrose; 40 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5; 20 mM MgCl2; 4% Triton X-100), and 6 ml water on ice for 20 min (with frequent mixing). Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation at 2,500 G for 15 min. Nuclear pellets were resuspended in 1 ml RIP buffer (150 mM Kcl, 25 mM Tris pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5% NP40; 100 U/ml SUPERaseIn, Ambion; cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor, Sigma). Resuspended nuclei were split into two fractions of 500 μl each (for Mock and IP) and were mechanically sheared using a dounce homogenizer. Nuclear membrane and debris were pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 RPM for 10 min. Antibody to EZH2 (Cell Signaling cat# 4905S; 1:30) or Normal Rabbit IgG (Mock IP, SantaCruz; 10 μg) were added to supernatant and incubated for 2 hours at 4°C with gentle rotation. 25 μL of protein G beads (New England BioLabs cat# S1430S) were added and incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with gentle rotation. Beads were pelleted by magnetic field, the supernatant was removed, and beads were resuspended in 500 μl RIP buffer and repeated for a total of three RIP washes, followed by one wash in PBS. Beads were resuspended in 1 ml of Trizol. Coprecipitated RNAs were isolated, reverse transcribed to cDNA, and assayed by qPCR for the Hprt and Morrbid-isoform1. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

PAR-CLIP analysis

EZH2 PAR-CLIP dataset (GSE49435) was analyzed as previously described22. Adapter sequences were removed from total reads and those longer than 17 bp were kept. The Fastx toolkit was used to remove duplicate sequences, and the resulting reads were mapped using BOWTIE allowing for two mismatches. The four independent replicates were pooled and analyzed using PARalyzer, requiring at least two T->C conversions per RCS. LncRNAs were annotated according to Ensemble release 67.

Chromosome Conformation Capture (3C)

13 ×106 WT bone marrow derived mouse eosinophils were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, and quenched with 0.2M glycine on ice. Eosinophils were lysed for 3-4 hours at 4°C (50mM Tris pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1% Triton X-100, 1X Roche complete protease inhibitor) and dounce homogenized. Lysis was monitored by Methyl-green pyronin staining (Sigma). Nuclei were pelleted and resuspended in 500ul 1.4X NEB3.1 buffer, treated with 0.3% SDS for one hour at 37°C, and 2% Triton X-100 for another hour at 37°C. Nuclei were digested with 800 units BglII (NEB) for 22 hours at 37°C, and treated with 1.6% SDS for 25 minutes at 65°C to inactivate the enzyme. Digested nuclei were suspended in 6.125mL of 1.25X ligation buffer (NEB), and were treated with 1% Triton X-100 for one hour at 37°C. Ligation was performed with 1000 units T4 DNA ligase (NEB) for 18 hours at 16°C, and crosslinks were reversed by proteinase K digestion (300 μg) overnight at 65°C. The 3C template was treated with RNase A (300 μg), and purified by phenol-chloroform extraction. Digested and undigested DNA were run on a 0.8% agarose gel to confirm digestion. To control for PCR efficiency, two BACs spanning the region of interest were combined in equimolar quantities and digested with 500 units BglII at 37°C overnight. Digested BACs were ligated with 100 units T4 Ligase HC (Promega) in 60ul overnight at 16°C. Both BAC and 3C ligation products were amplified by qPCR (Applied Biosystems ViiA7) using SYBR fast master mix (KAPA biosystems). Products were run side by side on a 2% gel, and images were quantified using ImageJ. Intensity of 3C ligation products was normalized to intensity of respective BAC PCR product.

Listeria monocytogenes infections

Mice were infected with 30,000 colony-forming units (CFUs) of Listeria monocytogenes (Strain 10403s) intravenously (i.v.). Mice were weighed and inspected daily. Mice were analyzed at day 4 of infection to determine the CFUs of L. monocytogenes present in the spleen and liver.

Papain challenge

Papain was purchased from Sigma Aldrich and resuspended in at 1mg/ml in Phosphate buffered Saline (PBS). Mice were intranasally challenged with 5 doses of 20 μg papain in 20 μl of PBS or PBS alone every 24 hours. Mice were sacrificed 12 hours after the last challenge. Bronchoalveolar lavage was collected in two 1 mL lavages of PBS. Cellular lung infiltrates were collected after 1 hour digestion in RPMI supplemented with 5% FCS, 1 mg/ml Collagenase D (Roche) and 10 μg/ml DNase I (Invitrogen) at 37°C. Homogenates were passed through a cell strainer and infiltrates separated with a 27.5%, Optiprep gradient (Axis-Shield) by centrifugation at 2750 rpm for 20 min. Cells were removed from the interface and treated with ACK lysis buffer.

Bone marrow chimeras

Congenic C57BL/6 (WT) bone marrow expressing CD45.1 and CD45.2 and Morrbid-deficient bone marrow expression CD45.2 was mixed in a 1:1 ratio and injected into C57BL/6 hosts irradiated twice with 5 Gy 3 hours apart that express CD45.1 (B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ). Mice were analyzed between 4-9 weeks after injection.

Bone marrow derived eosinophils

Bone marrow was isolated and cultured as previously described9. Briefly, unfractionated bone marrow cells were cultured with 100 ng/ml stem cell factor (SCF) and 100 ng/ml FLT3-Ligand (FLT3-L). At day 4, the media was replaced with media containing 10ng/ml interleukin (IL-5). Mature bone marrow derived eosinophils were analyzed between day 10-14.

Bone marrow derived macrophage cultures

Bone marrow cells were isolated and cultured in media containing recombinant murine M-CSF (10 ng/ml) for 7-8 days. On day 7-8, cells were re-plated for use in experimental assays. Bone marrow derived macrophages were stimulated with LPS (250 ng/mL) for the indicated periods of time.

ChIRP-qPCR

Briefly, 40 × 107 Immortalized bone marrow derived macrophages were fixed with 40 ml of 1% glutaraldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Crosslinking was quenched with 0.125M glycine for 5 min. Cells were rinsed with PBS, pelleted for 4 min at 2000g, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Cell pellets were thawed at room temperature and resuspended in 800 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 1 mM PMSF, cOmplete protease inhibitor (Roche), 0.1 U/ml Superase In (Life Technologies)). Cell suspension was sonicated using a Covaris S220 machine (Covaris; 100 W, duty factor 20%, 200 cycles/burst) for 60 minutes until DNA was in the size range of 100–500 bp. After centrifugation for 5 min at 16100g at 4°C, the supernatant was aliquoted, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. 1 mL of chromatin was diluted in 2 mL hybridization buffer (750 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 15% formamide) and input RNA and DNA aliquots were removed. 100 pmoles of probes (Supplementary Table 1) were added and mixed by rotation at 37°C for 4 hr. Streptavidin paramagnetic C1 beads (Invitrogen) were equilibrated with lysis buffer. 100 μl washed C1 beads were added, and the entire reaction was mixed for 30 min at 37°C. Samples were washed five times with 1 ml of washing buffer (SSC 2x, 0.5% SDS and fresh PMSF). 10% of each sample was removed from the last wash for RNA isolation. RNA aliquots were added to 85 μl RNA PK Buffer pH 7.0 ( 100mM NaCl, 10mM TrisCl pH 7.0, 1mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, 0.2U/ul Proteinase K) and incubated for 45 min with end-to-end shaking. Samples were spun down, and boiled for 10 min at 95°C. Samples were chilled on ice, added to 500uL TRizol, and RNA was extracted according to manufacturer's recommendations. Equal volume of RNA was reversed transcribed and assayed by qPCR using Hprt and Morrbid-exon1-1 primer sets (Supplementary Table 1). DNA was eluted from remaining bead fraction twice using 150 μL DNA elution buffer (50mM NaHCO3, 1%SDS, 200mM NaCl, 100 μg/mL RNase A, 100U/mL RNase H) incubated for 30 min at 37°C. DNA elutions were combined and treated with 15μL (20mg/mL) Proteinase K for 45min at 50°C. DNA was purified using Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl and assayed by qPCR using the indicated primer sequences (Supplementary Table 1).

shRNA generation and transduction

shRNAs of indicated sequences (Supplementary Table 1) were cloned into pGreen shRNA Cloning and Expression Lentivector. Psuedotyped lentivirus was generated as previously described, and 293T cells were transfected with a packaging plasmid, envelop plasmid, and the generated shRNA vector plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000. Virus was harvested 14-16hrs and 48hrs post transfection, combined, 0.4μm filtered, and stored at −80°C. For generation of in vivo bone marrow (BM) chimeras, virus was concentrated 6X by ultra centrifugation using a Optiprep gradient (Axis-Shield).

For transduced BM-derived eosinophils, cultured BM cells on day 3 of previously described culture conditions were mixed 1:1 with indicated lentivirus and spinfected for 2hrs at 260 x g at 25°C with 5 μg/mL polybrene. Cultures were incubated overnight at 37°C, and media was exchanged for IL-5 containing media at day 4 of culture as previously described9. Cells were sorted for GFP+ cells on day 5 of culture, and then cultured as previously described for eosinophil generation. Cells were assayed on day 11 of culture.

For transduced in vivo BM chimeras, BM cells were cultured at 2.5×106 cells/mL in mIL-3 (10 ng/mL) mIL-6 (5 ng/mL) and mSCF (100 ng/mL) overnight at 37°C. Culture was readjusted to 2 mL at 2.5×106 cells/mL in a 6 well plate, and spinfected for 2hrs at 260 x g at 25°C with 5 μg/mL polybrene. Cells were incubated overnight at 37°C. On the day prior to transfer, recipient hosts were irradiated twice with 5 Gy 3 hours apart. Mice were analyzed between 4 and 5 weeks following transfer.

Locked nucleic acid knock-down

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were transfected with pooled Morrbid or scrambled locked nucleic acid (LNA) antisense oligonucleotides of equivalent total concentrations using Lipofectamine 2000. Morrbid LNA pools contained Morrbid LNA 1-4 sequences at a total of 50 or 100 nM (Supplementary Table 1). After 24 hours, the transfection media was replaced. The BMDMs were incubated for an additional 24 hours and subsequently stimulated with LPS (250 ng/mL) for 8-12 hours.

Eosinophils were derived from mouse BM as previously described. On day 12 of culture, 1–2 × 106 eosinophils were transfected with 50 nm of Morrbid LNA 3 or scrambled LNA (Supplementary Table 1) using TransIT®-oligo according to manufacturer's protocol. RNA was extracted 48 hours post transfection.

Morrbid promoter deletion

Guide–RNAs targeting the 5’ and 3’ flanking regions of the Morrbid promoter were cloned into Cas9 vectors pSPCas9(BB)-2A-GFP(PX458) (Addgene plasmid #48138) and pSPCas9(BB)-2A-mCherry (a generous gift from Dr. Stitzel lab, JAX-GM) respectively. gRNA sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The cloned Cas9 plasmids were then transfected into RAW 264.7, a murine macrophage cell line using Lipofectamine 2000 according to manufacturer's protocol. Forty–eight hours post transfection the double positive cells expressing GFP and mcherry, and the double negative cells lacking GFP and mcherry were sorted. The bulk sorted cells were grown in a complete media containing 20% FBS, assayed for deletion by PCR, as well as for Morrbid and Bcl2l11 transcript expression by qPCR. RAW 264.7 cells were obtained from ATCC and were not authenticated, but were tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Ex vivo cytokine stimulation

Bone marrow (BM)-derived eosinophils, or neutrophils or Ly6Chi monocytes sorted from mouse BM, were rested for 4-6 hours at 37°C in complete media. Cells were subsequently stimulated with IL-3 (10ng/mL, Biolegend), IL-5 (10ng/mL, Biolegend), GM-CSF (10ng/mL, Biolegend), or G-CSF (10ng/mL, Biolegend) for 4-6 hours. RNA was collected at each timepoint using TRIzol (Life Technologies).

GSK126 treatment

WT and Bcl2l11−/− bone marrow (BM)-derived eosinophils were generated as previously described9. On day 8 of culture, the previously described IL-5 media was supplemented with the indicated concentrations of the EZH2 specific inhibitor, GSK126 (Toronto Research Chemicals). Media was exchanged for fresh IL-5 GSK126 containing media every other day. Cells were assayed for numbers and cell death by flow cytometry ever day for 6 days following GSK126 treatment.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from TRIzol (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Gycogen (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used as a carrier. Isolated RNA was quantified by spectophotemetry, and RNA concentrations were normalized. cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Resulting cDNA was analyzed by SYBR Green (KAPA SYBR Fast, KAPABiosystems) or Taqman based (KAPA Probe Fast, KAPABiosystems) using indicated primers. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. All reactions were performed in duplicate using a CFX96 Touch instrument (BioRad) or ViiA7 Real-Time PCR instrument (ThermoFischer Scientific).

RNA-seq and conservation analysis

Reads generated from mouse (Gr1+) granulocytes (previously published GSE53928), human neutrophils (previously published GSE70068), and bovine peripheral blood leukocytes (previously published GSE60265) were filtered, normalized, and aligned to the corresponding host genome. Reads mapping around the Morrbid locus were visualized. For visualization of Morrbid's high level of expression in short-lived myeloid cells, reads from sorted mouse eosinophils (previously published GSE69707), were filtered, aligned to mm9, normalized using RPKM, and gene expression was plotted in descending order. For each human sample corresponding to the indicated stimulation conditions, the number of reads mapping to the human MORRBID locus per total mapped reads was determined.

For conservation across species, the genomic loci and surrounding genomic regions for the species analyzed were aligned with mVista and visualized using the rankVista display generated with mouse as the reference sequence. Green highlights annotated mouse exonic regions and corresponding regions in other indicated species.

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization

Single molecule RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed as previously described. A pool of 44 oligonucleotides (Biosearch Technologies) were labeled with Atto647N (Atto-Tec). For validation purposes, we also labeled subsets consisting of odd and even numbered oligonucleotides with Atto647N and Atto700, respectively, and looked for colocalization of signal. We designed the oligonucleotides using the online Stellaris probe design software. Probe oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Thirty Z sections with a 0.3-μm spacing were taken for each field of view. We acquired all images using a Nikon Ti-E widefield microscope with a 100x 1.4NA objective and a Pixis 1024BR cooled CCD camera. We counted the mRNA in each cell by using custom image processing scripts written in MATLAB.

Cell fractionation

For nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation, 5 × 106 bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were generated as previously described and stimulated with 250 ng/mL LPS for 4 hours. Cells were harvested and washed once with cold PBS. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in 100 μL cold NAR A buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.9; 10mM KCl; 0.1 mM EDTA; 1X cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor, Sigma; 1mM DTT, 20mM β-glycerophasphate; 0.1 U/μL SUPERaseIn, Life Technologies), and incubated at 4°C for 20 min. 10 μL 1% NP-40 was added, and cells were incubated for 3 min at room temperature. Cells were vortexed for 30 seconds, and centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 1.5 min at 4°C. Supernatant was removed, centrifuged at full speed for 90 min at 4°C, and remaining supernatant was added to 500 μL Trizol as the cytoplasmic fraction. The original pellet was washed 4 times in 100 μL NAR A with short spins of 8500 rpm for 1 min. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μL NAR C (20 mM HEPES pH 7.9; 400mM NaCl; 1mM EDTA, 1X cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor, Sigma; 1mM DTT, 20mM β-glycerophasphate; 0.1 U/μL SUPERaseIn, Life Technologies). Cells were vortexed every 3 min. for 10 sec for a total of 20 minutes at 4°C. The sample was centrifuged at maximum speed for 20 minutes at room temperature. Remaining supernatant was added to 500 μL Trizol as the nuclear fraction. Equivalent volumes of cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA were converted to cDNA using gene specific primers and Super Script II RT (Life Technologies). Fraction was assessed by qPCR for Morrbid-exon1-1 and other known cytoplasmic and nuclear transcripts. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

For cytoplasmic, nuclear, and chromatin fractionation, cell fractions were harvested as described previously, with a few modifications. Briefly, 5-10 × 106 immortalized macrophages were activated with 250 ng/mL LPS (Sigma) for 6 hours at 37°C. Cells were washed 2X with PBS, and then resuspended in 380 μl ice-cold HLB (50mM Tris-HCl pH7.4, 50mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40, 10% glycerol), supplemented with 100 U SUPERase In RNase Inhibitor (Life Technologies). Cells were vortexed 30 seconds and incubated on ice 30 minutes, followed by a final 30 second vortex and centrifugation at 4°C for 5 minutes x 1000g. Supernatant was collected as the cytoplasmic fraction. Nuclear pellets were resuspended by vortexing in 380 μl ice-cold MWS (50 mM Tris-HCl pH7.4, 4mM EDTA, 0.3M NaCl, 1M Urea, 1% NP-40) supplemented with 100 U SUPERase In RNase Inhibitor. Nuclei were lysed on ice for 10 minutes, vortexed for 30 seconds, and incubated on ice for 10 more minutes to complete lysis. Chromatin was pelleted by centrifugation at 4°C for 5 minutes x 1000g. Supernatant was collected as the nucleoplasmic fraction. RNA was harvested as described previously and cleaned up using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Equivalent volumes of cytoplasmic, nucleoplasmic, and chromatin-associated RNA were converted to cDNA using random hexamers and Super Script III RT (Life Technologies). Fraction was assessed by qPCR for Morrbid-exon1-2 and other known cytoplasmic and nuclear transcripts. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Copy number analysis

Morrbid cDNA was cloned into reference plasmid (pCDNA3.1) containing a T7 promoter. The plasmid was linearized and Morrbid RNA was in vitro transcribed using the MEGAshortscript T7 kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, and purified using the MEGAclear kit (Life Technologies). RNA was quantified using spectrophotometry and serial dilutions of Morrbid RNA of calculated copy number were spiked into Morrbid-deficient RNA isolated from Morrbid-deficient mouse spleen. Samples were reverse transcribed in parallel with WT sorted neutrophil RNA and B cell RNA isolated from known cell number using gene specific Morrbid primers, and the Morrbid standard curve and WT neutrophils and B cells were assayed using qPCR with Morrbid-exon 1 primer sets (Supplementary Table 1)

Bromodeoxyuridine incorporation assay

Cohorts of mice were given a total of 4 mg Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; purchased from Sigma Aldrich) in 2 separate intraperitoneal (I.P.) injections 3 hrs apart and monitored over the subsequent 5 days, unless otherwise noted. For analysis cells were stained according to manufacturer protocol (BrdU Staining Kit, ebioscience; anti-BrdU, Biolgend). A one-phase exponential curve was fitted from the peak labeling frequency to 36hrs post peak labeling within each genetic background, and the half-life was determined from this curve.

Human samples

Human subject cohort 1

Study subjects were recruited and consented in accordance with the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board. Peripheral blood was separated by Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation, and the mononuclear cell layer and erythrocyte/granulocyte pellet were isolated and stained for fluorescence-associated cell sorting as previously described. Neutrophils (Live, CD16+, F4/80int, CD3−, CD14−, CD19−), Eosinophils (Live, CD16−, F4/80hi, CD3−, CD14−, CD19−), T cells (Live, CD3+, CD16−), Monocytes (Live, CD14+, CD3−, CD16−, CD56−), NK cells (Live, CD56+, CD3−, CD16−, CD14−), B cells (Live, CD19+, CD3−, CD16−, CD14−, CD56−).

Human subject cohort 2

Samples from human subjects were collected on NIAID IRB-approved research protocols to study eosinophilic disorders (NCT00001406) or to provide controls for in vitro research (NCT00090662). All participants gave written informed consent. Eosinophils were purified from peripheral blood by negative selection and frozen at −80°C in TRIzol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Purity was >97% as assessed by cytospin. RNA was purified according to the manufacturer's instructions. Expression analysis by qPCR was performed in a blinded manner by an individual not involved in sample collection or coding of these of these samples. Plasma IL-5 levels were measured by suspension array in multiplex (Millipore, St. Charles, MO). The minimum detectable concentration was 0.1 pg/mL. Abbreviations for HES subtypes are Familial HES (FHES), PDGFRA+ positive HES (PDGFRA), episodic angioedema and eosinophilia (EAE), lymphocytic variant HES (LHES), HES of undetermined significance (HEus), and parasitic infection (PARA).

Statistics

Samples sizes were estimated based on our preliminary phenotyping of Morrbid-deficient mice. Preliminary cell number analysis of eosinophils, neutrophils, and Ly6Chi monocytes suggested that there were very large differences between WT and Morrbid-deficient samples, which would allow statistical interpretation with relatively small numbers. No animals were excluded from analysis. All experimental and control mice and human samples were run in parallel to control for experimental variability and were not randomized. Experiments corresponding to Fig. 3g-i and Fig. 4g-j were performed and analyzed in a single-blinded manner. All other experiments were not blinded. Correlation was determined by calculating the Spearman correlation coefficient. Half-life was estimated by calculating the one-phase exponential decay constant from the peak of labeling frequency to 36 hours post peak labeling. P values were calculated using a two-way t test, Mann-Whitney U test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis, Kaplan-Meier Mantel-Cox test, and FDR as indicated. FDR was calculated using TMM normalized read counts and the DiffBind R package as described in Extended Data Fig. 7c,d. All error bars indicate mean plus and minus the standard error of mean (SEM).

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Morrbid transcript expression, localization, and conservation across species.

(a) (Left) Mouse, human, and cow Morrbid transcripts. Human neutrophil, mouse granulocyte, and cow peripheral blood RNA-seq data are represented as read density around the Morrbid transcript of each species. (Right) The Morrbid loci and surrounding genomic regions of the indicated species were aligned with mVista and visualized using the rankVista display generated with mouse as the reference sequence. Green highlights annotated mouse exonic regions and corresponding regions in other indicated species.

(b) Quantification of Morrbid FISH spots per indicated cell population. Cells were stained with Morrbid RNA probes conjugated to 2 different fluorophores, and spots colocalizing in both fluorescent channels were quantified.

(c) Cytoplasmic and nuclear subcellular RNA fractionation of LPS stimulated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) with qPCR of indicated target transcripts (n=3 macrophages generated from independent mice).

(d) Cytoplasmic, nuclear, and chromatin subcellular RNA fractionation of LPS stimulated immortalized BMDMs with qPCR of indicated target transcripts (average of 4 independent experiments)

(e) Mature eosinophil transcriptome sorted in descending order of log(RPKM) gene expression, with annotated select reported eosinophil-associated genes.

(f) Average number of Morrbid RNA copies per cell in sorted neutrophils and B cells. (Left) Standard curve generated using in vitro transcribed Morrbid RNA spiked into Morrbid-deficient RNA isolated from spleen. (Right) calculated per cell Morrbid RNA copies (n=3 replicates from independent mice).

(g) Representation of CRISPR-Cas9 targeting of the Morrbid locus with indicated guide- RNA (gRNA) sequences and genotyping primer sets. Target gRNA sequences are bolded.

(h) Cells isolated from the blood of wild-type (WT) mice. Representative flow cytometry plots demonstrating the gating strategy for Neutrophils (CD45+, CD11b+, LY6G+), T cells (CD45+, Ly6G−, CD3+), B cells (CD45+, Ly6G−, CD3−, CD19+), Eosinophils (CD45+, CD3−, CD19−, Ly6G−, Siglec f+, SSChi), Ly6Chi Monoctyes (CD45+, CD3−, CD19−, Ly6G−, SSClo, Siglec f−, Ly6Chi, CSF-1R+), Natural Killer cells (CD45+, CD3−, CD19−, Ly6G−, SSClo, Siglec f−, CSF-1R−, NK1.1+).

(i) Total cell numbers of the indicated cell populations isolated from the spleen of WT and Morrbid-deficient mice (n=3-5 mice per group, results representative of 8 independent experiments).

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test c,f,i; oneway Anova with Tukey post hoc analysis d).

Extended Data Fig. 2. Myeloid cell populations in tissue following Morrbid deletion and blood and spleen following Morrbid knockdown in vivo.

(a) Representative flow-cytometry plots and absolute counts of the indicated cell populations in wild-type (WT) and Morrbid-deficient mice (n=3-5 mice per group, representative of 3-7 independent experiments).

(b) shRNA knockdown of Morrbid RNA relative to control vector in bone marrow (BM) transduced with the indicated GFP vector, sorted on GFP, differentiated into eosinophils and assessed by qPCR (each dot represents eosinophils generated from independent mice).

(c) Schematic of control and Morrbid shRNA1 BM chimera generation

(d-e) Frequency of indicated cell populations within total GFP+ transduced cells from (d) blood and (e) spleen. (n=3-4 mice per transduction group).

(f-h) WT and Morrbid-deficient mice challenged with papain or PBS. (f) Absolute numbers of indicated cell populations in lung tissue and BAL. (g) qPCR expression in lung tissue. (h) Representative H&E and PAS lung histology. (n=3-4 mice per group; representative of two independent experiments)

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test a,b,d,e; Mann-Whitney U-test f,g).

Extended Data Fig. 3. Morrbid regulation of mature neutrophils, eosinophils, and Ly6Chi monocytes is cell-intrinsic.

(a-e) Morrbid-deficient competitive bone marrow (BM) chimera generation. (a) Schematic of mixed-bone marrow (BM) chimera generation. Congenically labeled wild-type (WT) CD45.1+CD45.2+ and Morrbid-deficient CD45.2+ BM cells were mixed 1:1 and injected into an irradiated CD45.1+ host. (b) Ratio of mixed congenically labeled wild-type (WT) CD45.1+CD45.2+ and Morrbid-deficient CD45.2+ BM cells prior to injection into an irradiated CD45.1+ host. (c) Ratio of Morrbid-deficient to WT short-lived myeloid and control immune cells in blood and (d) representative flow-cytometry plots of these cell populations. (e) Morrbid-deficient to WT ratio of additional immune cell populations (n=4-8 mice per group; pooled from two independent experiments).

(f) Schematic of myeloid differentiation and Morrbid qPCR expression in the indicated sorted progenitor and mature cells (n=3-5 mice per group; representative of 3 independent experiments).

(g) Cells isolated from the BM of wild-type (WT) mice. Representative flow cytometry plots demonstrating the gating strategy for Common Myeloid Progenitor (CMP): Lineage-(Sca1,CD11b,GR-1,CD3, Ter-119, CD19, B220, NK1.1), IL7Ra−, C-kit+, CD34+, CD16/32lo/int; Granulocyte/Monocyte Progenitor (GMP): Lineage-, IL7Ra−, C-kit+, CD34+, CD16/32hi; Monocyte/Dendritic cell Progenitor (MDP): Lineage-, IL7Ra−, C-kit+, CD115+, CD135+; Eosinophil Progenitor (EosP): Lineage-, IL7Ra−, C-kit+, CD34+, CD16/32hi, IL-5Ra+. Flow cytometry count beads are visualized and gated by forward and side scatter area.

(h) Cells isolated from the BM of WT mice. Representative flow cytometry plots demonstrating the gating strategy for Eosinophils: Dump- (Dump: CD3, NKp46, Ter119, CD19, Ly6G, Sca1), CSF-1R-, C-kit neg/lo, SiglecF+, SSChi; Monocytes: Dump-, CSF- 1R+, C-kit-, MHCII-, Ly6Chi; Common Monocyte Progenitor (cMoP): Dump-, CSF-1R+, C-kit+, Ly6Chi, CD11blo. Flow cytometry count beads are visualized and gated by forward and side scatter area.

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (one-way Anova with Tukey post hoc analysis).

Extended Data Fig. 4. Morrbid regulates neutrophil, eosinophil, and Ly6Chi monocyte lifespan through cell-intrinsic regulation of Bcl2l11.

(a) Flow cytometric analysis of percentage of BrdU incorporation in the indicated wild-type (WT) and Morrbid-deficient immune cell populations from blood. Mice were analyzed 24 hours following one dose of 2 mg BrdU (n = 3 mice per group).

(b) Representative flow-cytometry plots and absolute counts of mature eosinophils (Live, CD45+, SSChi, CD11b+, Siglec F+) of bone-marrow (BM)-derived eosinophil culture on day 12 (D12) in WT and Morrbid-deficient mice (n=3 mice per group, results representative of 3 independent experiments).

(c) Morrbid expression of developing WT BM-derived eosinophils at indicated time points of in vitro culture (n=3 mice per group).

(d) Percentage of annexin V+ WT and Morrbid-deficient BM cell populations at indicated time points of ex vivo culture (n = 3 mice per group; data are representative of two independent experiments).

(e) Percentage of annexin V+ eosinophils (gated on annexin V+, CD45+, SSChi, CD11b+, Siglec F+) of BM-derived eosinophil culture on D12 in WT and Morrbid- deficient mice (n=3 mice per group, results representative of 3 independent experiments).

(f) Percentage of annexin V+ WT and Morrbid-deficient neutrophils and Ly6Chi monocytes 4 days following L. monocytogenes infection (n=3 mice per group, representative of 2 independent experiments).

(g) Flow cytometric analysis of percentage and absolute number of blood neutrophils from WT or Morrbid-deficient mice that were pulsed two times with 2 mg BrdU 3 hrs apart and monitored over 5 days. (n = 4 mice per group; data are representative of three independent experiments).

(h) Western blot analysis of BCL2L11 protein expression in WT and Morrbid-deficient sorted BM neutrophils.

(i) BCL2L11 protein expression measured by flow-cytometry in blood neutrophils from WT, Morrbid-deficient, and Bcl2l11-deficient mice (n=1-4 mice per group).

(j-k) BCL2L11 protein expression in mixed-BM chimera model. Quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of BCL2L11 protein expression in indicated cell populations from (j) blood and (k) BM (n=4-8 mice per group, results representative of two independent experiments).

(l) BCL2L11 protein expression in the indicated progenitors and mature cell-types from WT and Morrbid-deficient mice. n/a indicates that too few cells were present for MFI quantification (n=3-5 mice per group, results representative of 3 independent experiments).

(m) BCL2L11 expression measured in the indicated cell populations from wild-type (WT) and Morrbid-deficient mice (n=3, results representative of two independent experiments).

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Morrbid specifically controls Bcl2l11 expression.

(a) Schematic representation of genes surrounding the Morrbid locus.

(b-c) Expression of indicated transcripts assessed by qPCR in (b) neutrophils and (c) Ly6Chi monocytes sorted from wild-type (WT) and Morrbid-deficient mice. N.D. (not detected) indicates expression was below the limit of detection. (n=3 mice per group, representative of 2 independent experiments).

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Knockdown of Morrbid leads to Bcl2l11 upregulation and cell death.

(a) Schematic of shRNA transduced bone marrow (BM)-derived eosinophil system.

(b-d) In vitro shRNA BM-derived eosinophil competitive chimera. (b) Schematic of transduction of CD45.2+ and CD45.1+ BM cells transduced with GFP scrambled- shRNA or GFP Morrbid-specific shRNA lentiviral vectors, respectively. GFP+ cells were sorted, mixed 1:1, differentiated into eosinophils, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (c) Representative histogram and MFI quantification of BCL2L11 expression of mature eosinophils separated by congenic marker. (d) Percent contribution of each congenic BM to the total mature eosinophil pool (n=3 mice per group, each dot represents eosinophils differentiated from the BM of 1 mouse, representative of 2 independent experiments).

(e) Morrbid and Bcl2l11 expression of WT BM-derived eosinophils transfected with Morrbid-specific LNA 3 and control locked nucleic acids (LNAs). (each dot represents the average of 2-3 biological replicates, data pooled from 5 independent experiments).

(f) Morrbid and Bcl2l11 expression of wild-type (WT) and Morrbid-deficient BM-Derived Macrophages (BMDMs) at the indicated time points following LPS stimulation. Expression is represented as fold change from time 0 (t0) (n=3 mice per group, representative of 3 independent experiments).

(g-i) LPS-stimulated BM-derived macrophages transfected with pooled Morrbid-specific (LNA 1-4) or scrambled (Cntrl LNA) antisense locked nucleic acids (LNAs). (g) Morrbid and Bcl2l11 qPCR expression. (h) Annexin V+ expression and (i) absolute BM-derived macrophage numbers (n=3 mice per group, representative of 6 independent experiments).

(j-l) Morrbid promoter deletion in immortalized BMDMs. (j) Diagram of Morrbid promoter targeting in immortalized BMDMs using CRISPR-Cas9. Immortalized BMDMs were transfected with GFP expressing Cas9 and Cherry expressing gRNA vectors of the indicated sequences. GFP+/Cherry+ and GFP−/Cherry− expressing cells were sorted and assayed at the bulk level using (k) PCR for verification of promoter deletion using the indicated primers and (l) qPCR for Morrbid and Bcl2l11 expression following LPS stimulation for 6 hours. (n=3 LPS stimulated cultures, average of 3 independent experiments).

(m) Morrbid and Bcl2l11 transcript expression in WT and Morrbid-deficient sorted BM neutrophils stimulated with G-CSF for 4 hours. Expression is represented as fold change from unstimulated. (n=3 mice, representative of 2 independent experiments).

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Epigenetic impact of Morrbid deletion on its surrounding genomic region.

(a) ChIP-qPCR analysis of total Pol-II enrichment within the Bcl2l11 promoter and gene body in wild-type (WT) and Morrbid-deficient neutrophils. Results are represented as Bcl2l11 enrichment relative to control Actb enrichment within each sample. Each dot represents 1-2 pooled mice.

(b) ChIP-qPCR analysis of EZH2 enrichment within the Bcl2l11 promoter in WT and Morrbid-deficient bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) stimulated with LPS for 12 hours. Results are represented as Bcl2l11 enrichment relative to control MyOD1 enrichment within each sample. (n=3, each dot represents BMDMs generated from 1 mouse).

(c) Relative chromatin accessibility levels at the Bcl2l11, Acoxl, Anapc1, and Mertk promoters in Morrbid−/− and WT neutrophils as assessed by ATAC-seq. Chromatin accessibility levels were estimated as an average TMM (Trimmed mean of M-values) normalized read count across the replicates. Statistics were obtained by differential open chromatin analysis using the DiffBind R package. The Bcl2l11 promoter is more open in Morrbid−/− neutrophils with a 1.52 fold change with a FDR of < 0.1%. N.D. (not detected) indicates that no peak was present at the indicated promoter.

(d) Density plot of log2 fold change distribution for H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac and H3K36me3 levels between Morrbid−/− and WT neutrophils. Relative fold changes are estimated as the ratio of TMM normalized read counts within consensus peak regions and were obtained using the DiffBind R package. Positive and negative fold changes indicate higher levels of ChIP binding in Morrbid−/− and WT neutrophils, respectively. Dashed green lines show the 5th and 95th percentiles. The green triangles on the x-axis mark the change at the Bcl2l11 promoter or gene body between WT and Morrbid−/− neutrophils.

(e-f) ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq for H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K27ac, and H3K36me3 chromatin modifications were performed on neutrophils sorted from the bone marrow of wild-type (WT) and Morrbid-deficient mice. ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq are represented as read density (e) surrounding the Morrbid locus and (f) at the Bcl2l11 locus. ATAC-seq tracks are expressed as reads normalized to total reads, and chromatin modification tracks are expressed as reads normalized to input.

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test a,b; FDR of fold change as described above c,d).

Extended Data Fig. 8. Morrbid represses Bcl2l11 by maintaining its bivalent promoter in a poised state and Morrbid-haploinsufficiency.

(a) Venn diagram summary of EZH2 PAR-CLIP analysis, with representation of tags and RNA-protein contact sites (RCSs) as determined by PARalyzer mapping to Morrbid.

(b) Co-immunoprecipitation of the PRC2 family member EZH2 and Morrbid. Nuclear extracts of immortalized WT bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) stimulated with LPS for 6-12 hours were immunoprecipitated by IgG or anti-EZH2. Co-precipitation of indicated RNAs were assayed by qPCR. Data are represented as enrichment over IgG control (n=6 biological replicates pooled from 2 independent experiments, representative of 3 independent experiments).

(c) Validation of Morrbid RNA pull-down over other RNAs using pools of Morrbid capture probes and LacZ probes (n=3, average of 3 independent experiments).

(d) Visualized 3C PCR products from bait and indicated reverse primers using template from fixed and ligated bone marrow derived eosinophil DNA (S1, S2, and S3), BAC control (BAC), or water. The sequence of each reverse primer is listed in Supplementary Table 1.

(e-f) Bone marrow-derived eosinophils from wild-type (WT) and Bcl2l11−/− mice treated with EZH2 inhibitor GSK126 over time. (e) Frequency of non-viable (Aqua+) and (f) annexin V staining cells on day 5 following treatment with GSK126 (n=3 independently differentiated eosinophils per dose, results representative of 2 independent experiments).

(g) (Top) Total cell numbers and (Bottom) BCL2L11 protein expression of indicated cell populations from the blood of wild-type (WT), Morrbid-heterozygous, and Morrbid- deficient mice (n=3-5 mice per group, results representative of 3 independent experiments).

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (two-sided t-test c,g; one way Anova with Tukey post hoc analysis e,f; Mann-Whitney U-test b).

Extended Data Fig. 9. Generation of Morrbid-Bcl2l11 double heterozygous mice.

Diagram of allele specific CRISPR-Cas9 targeting of Bcl2l11. Bcl2l11 was targeted using indicated gRNA sequences in one cell embryos from a wild-type (WT) by Morrbid- deficient breeding. F1 mice with allele-specific Bcl2l11 deletions in cis or in trans of the Morrbid-deficient allele were bred to a WT background to demonstrate linkage or segregation of Bcl2l11 and Morrbid knock-out alleles. Second most right lanes of both gels contain Morrbid−/−; Bcl2l11+/+ DNA, and right most lanes contain water, as internal controls.

Extended Data Fig. 10. Morrbid regulates Bcl2l11 in an allele-specific manner and working model of the role of Morrbid.

(a) Diagram of the allele-specific combinations of Morrbid- and Bcl2l11-deficient heterozygous mice studied.

(b) Representative flow cytometry plots of indicated splenic cell populations in the specified allele-specific deletion genetic backgrounds. Neutrophils (CD45+, CD11b+, LY6G+), Monoctyes (CD45+, CD3−, CD19−, Ly6G−, SSClo, Siglec f−, Ly6Chi, CSF-1R+), and B cells (CD45+, Ly6G−, CD3−, CD19+). Wild type (WT), Morrbid heterozygote (Het), Bcl2l11 heterozygote and Morrbid heterozygote with deletions in trans (Trans), Bcl2l11 heterozygote and Morrbid heterozygote with deletions in cis (Cis).

(c) Absolute counts and (d) BCL2L11 protein expression of indicated splenic cell populations in the specified genetic backgrounds (n=3-9 mice per genetic background).

(e) Morrbid integrates extracellular signals to control the lifespan of eosinophils, neutrophils, and “classical” monocytes through the allele-specific regulation of Bcl2l11. Pro-survival cytokines induce Morrbid, which promotes enrichment of the PRC2 complex within the bivalent Bcl2l11 promoter through direct and potentially indirect mechanisms to maintain this gene in a poised state. Tight control of the turnover of these short-lived myeloid cells by Morrbid promotes a balance of host anti-pathogen immunity with host damage from excess inflammation.

Error bars show s.e.m. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (one-way Anova with Tukey post hoc analysis).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank several of our colleagues for critically reading our manuscript and their suggestions. J.H-M. was supported by the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, the IFI and IDOM pilot projects, and the COE at the University of Pennsylvania (J.H-M.); A.W. and R.A.F. by NIH NIAID 1R21AI110776-01; C.C.D.H. and R.A.F by Howard Hughes Medical Institute; J.J.K. by NIH NIDDK T32-DK00778017; S.P.S by NIH NRSA F30-DK094708; W.K.M by T32-AI05542803; A.R. and M.C.D. by New Innovator 1DP2OD008514, 1R33EB019767, NSF CAREER 1350601. This work was funded in part by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH (M.A.M. and A.D.K.)

Footnotes

Contributions:

J.J.K, S.P.S, A.W., R.A.F., and J.H-M. designed these experiments. J.J.K, S.P.S, J.H-M. wrote the manuscript. A.W. and R.A.F edited the manuscript. L.G. and J.R. performed the bioinformatic analysis of lncRNA identification. J.S. and C.H. for aiding in the generation novel mice. D.B.U.K performed in vitro promoter targeting and eosinophil LNA transfection. M.C. and A.U. prepared and analyzed the ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq. E.N.E. performed 3C. M.C.D and A.R. performed FISH. M.A.M and A.D.K collected and aided in the analysis of HES patient samples. All other experiments and analyses were performed by J.J.K, S.P.S., J.H-M., and A.W. with help from S.J.M, W.K.M, C.C.D.H, A.T.V., S.Z., and W.B.

Competing financial interests:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE85073.

Citations

- 1.Manz MG, Boettcher S. Emergency granulopoiesis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:302–314. doi: 10.1038/nri3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginhoux F, Jung S. Monocytes and macrophages: developmental pathways and tissue homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:392–404. doi: 10.1038/nri3671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heo JB, Sung S. Vernalization-mediated epigenetic silencing by a long intronic noncoding RNA. Science. 2011;331:76–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1197349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xing Z, et al. lncRNA directs cooperative epigenetic regulation downstream of chemokine signals. Cell. 2014;159:1110–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouffi C, et al. Transcription Factor Repertoire of Homeostatic Eosinophilopoiesis. J. Immunol. 2015;195:2683–2695. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo M, et al. Long non-coding RNAs control hematopoietic stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yona S, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geissmann F, et al. Development of Monocytes, Macrophages, and Dendritic Cells. Science. 2010;327:656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]