Abstract

A novel entry mechanism has been proposed for the avian sarcoma and leukosis virus (ASLV), whereby interaction with specific cell surface receptors activates or primes the viral envelope glycoprotein (Env), rendering it sensitive to subsequent low-pH-dependent fusion triggering in acidic intracellular organelles. However, ASLV fusion seems to proceed to a lipid mixing stage at neutral pH, leading to the suggestion that low pH might instead be required for a later stage of viral entry such as uncoating (L. J. Earp, S. E. Delos, R. C. Netter, P. Bates, and J. M. White. J. Virol. 77:3058-3066, 2003). To address this possibility, hybrid virus particles were generated with the core of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), a known pH-independent virus, and with subgroups A or B ASLV Env proteins. Infection of cells by these pseudotyped virions was blocked by lysosomotropic agents, as judged by inhibition of HIV-1 DNA synthesis. Furthermore, by using HIV-1 cores that contain a Vpr-β-lactamase fusion protein (Vpr-BlaM) to monitor viral penetration into the cytosol, we demonstrated that virions bearing ASLV Env, but not HIV-1 Env, enter the cytosol in a low-pH-dependent manner. This effect was independent of the presence of the cytoplasmic tail of ASLV Env. These studies provide strong support for the model, indicating that low pH is required for ASLV Env-dependent viral penetration into the cytosol and not for viral uncoating.

For enveloped viruses, delivery of the viral nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm of infected cells occurs via fusion of viral and cellular membranes, after attachment of the virus to cognate receptor molecules at the cell surface. This process is mediated by viral fusion proteins anchored in the viral envelope which, after receipt of one or more triggers, elicit fusion via a series of conformational changes. For pH-dependent viruses, such as vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), fusion is triggered solely by low pH after internalization of the virus and trafficking to acidic intracellular compartments. Conversely, for pH-independent viruses, such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), fusion is triggered by interaction with cognate receptors and, in some cases coreceptors, often at the cell surface (for a detailed review of these pathways, see references 15, 22, and 37).

A third mode of viral entry has been proposed for the alpharetrovirus avian sarcoma and leukosis virus (ASLV) that combines aspects of both pH-independent and pH-dependent entry mechanisms (11, 29, 31, 34, 35, 38). In this case, interaction with cognate receptors at the cell surface is predicted to induce a conformational change in the viral fusion protein (Env), which renders it sensitive to subsequent low-pH-dependent triggering in intracellular acidic compartments (11, 29, 31, 34, 35, 38; for a review, see reference 2).

Several lines of evidence support this two-step model for ASLV entry. ASLV Env can efficiently trigger syncytium formation only with cells that express the cognate viral receptor and only under low-pH conditions (29, 31). Also, ASLV entry is inhibited by lysosomotropic agents and by dominant-negative dynamin-1 that blocks clathrin and caveolar-dependent endocytosis (11, 31, 34), observations that are consistent with viral entry via acidic endosomes. Previous experiments performed with hybrid murine leukemia virus (MLV)/ASLV-Env pseudotyped virions demonstrated that low pH is required for ASLV entry and is a function of the avian viral Env protein (31). That the combination of receptor priming and low pH is required to fully trigger the fusogenic potential of Env is further suggested by the fact that soluble receptor binding and low-pH treatment are both required to inhibit viral infectivity (3, 20, 31, 39).

Alternative models have been proposed to account for the role of low pH during ASLV entry (14). These models were based on the findings that ASLV particles associated with artificial membranes at neutral pH after interaction with receptor, most likely because the fusion peptides of Env were inserted into the target membrane. Also, lipid-mixing between pyrene-labeled ASLV and cell membranes was observed at neutral pH, which was inhibited by a C-terminal six-helix bundle (6HB) peptide. It was also suggested that a transient treatment with lysosomotropic agents had no effect upon ASLV entry, at least when its impact on viral entry was monitored 38 h later (14). Moreover, cell-cell fusion was observed at neutral pH when cells overexpressing ASLV Env were incubated with ASLV receptor-expressing cells for an extended time period at neutral pH (14). Based upon these results the authors of that study concluded that the ASLV Env-dependent membrane fusion reaction proceeded at least to the lipid-mixing stage at neutral pH. They also questioned a role for low pH to elicit complete fusion, which results in the delivery of ASLV particles into the cytosol. Instead, they suggested that lysosomotropic agent treatment might alter virus trafficking away from the site of fusion or, alternatively, that low pH may play a role in viral uncoating by a mechanism that is reminiscent of that seen with influenza A virus (21, 36).

In order to explore whether low pH could be required to initiate events subsequent to ASLV Env-driven fusion, we used an assay that monitors penetration into the cytosol by pH-independent HIV-1 viral cores that contain a Vpr-BlaM fusion protein (5, 32, 43). Vpr-BlaM delivery into the cytoplasm is independent of the required viral uncoating steps, since this recombinant enzyme is efficiently translocated in the context of HIV reporter particles (HIVRPs) that cannot undergo uncoating/reverse transcription because of altered capsid stabilities (16). Vpr-BlaM is also efficiently translocated into cells that do not support HIV uncoating/reverse transcription. Cytosolic delivery of Vpr-BlaM is monitored in this assay by cleavage of the cytoplasm-trapped fluorescent substrate (CCF2 or CCF4), which abolishes the internal fluorescence energy transfer of CCF2, resulting in a shift in the emission wavelength from 518 nm (green) to 447 nm (blue) after excitation at 409 nm. Therefore, viral penetration into the cytosol is readily quantitated in this assay by calculating the ratio of blue to green signal in the cells.

This assay was adapted for the study of ASLV Env-dependent viral entry by generating hybrid viral particles with either subgroup A or B ASLV Env and HIV-1 cores containing Vpr-BlaM. In contrast to HIV-1, which entered cells in a pH-independent manner, the hybrid viral particles with ASLV Env proteins required low pH to penetrate cellular membranes and enter the cytosol. Thus, low pH is required at the level of ASLV Env-dependent membrane fusion to deliver the viral core into the cytoplasm and is unlikely to be required instead for subsequent steps after viral penetration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

293 cells expressing TVA800 (34) or TVBS1(ΔDD) (1) were produced as described previously (34). Cells were sorted for high expression of TVA or TVBS1(ΔDD) by using fluorescence activated cell sorting as described previously (49) after incubation with subgroup A and B SU-immunoadhesin fusion proteins SUArIgG or SUBrIgG, respectively (4) and a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary antibody. 293 cells expressing TVA800, CXCR4, and CD4 (293TVA800/CXCR4/CD4 cells) were produced by retroviral transduction. MLV particles were produced that contained the VSV spike protein (VSV-G) with either pMX.T4 (27) (CD4) or pBABE-CXCR4 (10) (CXCR4) derived genomes. These viral particles were produced from 293 cells transfected with 2.5 μg of pMD.old.gagpol (encoding MLV Gag and Gag-Pol proteins), 3 μg of pMD.G (encoding VSV-G), and 2.5 μg of either pMX.CD4 or pBABE-CXCR4 by using Lipofectamine2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). The viral supernatants were collected 48 and 72 h after transfection, spun at 1,250 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter. These viral stocks were then used to infect 293T TVA800 cells. Cells were then sorted for high expression of CD4 by flow cytometry by using a phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody (Leu3A-PE; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). Expression of TVA800, CXCR4, and CD4 on 293 cells was confirmed by flow cytometry with Leu3a-PE, a PE-conjugated anti-CXCR4 antibody (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.), or SUArIgG (49) for CD4, CXCR4, and TVA800, respectively.

Production of HIVRP-pseudotyped particles.

To make HIV-1 pseudotyped viruses, a population of 107 293 cells was cultured in a 10-cm tissue culture dish and transfected by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions, with 2.5 μg of pMM310 (Vpr-BlaM vector), 2.5 μg of pR9ΔEnv (replication-incompetent HIV virus), and 3 μg of either pMD.G (VSV-G), pAB6 (ASLV-A), pAB7 (ASLV-B), or pCB6WTAΔ513 (ASLV-A Δ513) (26). After transfection, the cells were incubated with fresh medium, and the virus-containing supernatants were harvested 24, 48, and 72 h later. These supernatants were pooled, centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and then filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter. The viral preparations were then concentrated by ultracentrifugation through a 15% sucrose cushion at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C and resuspended in HMS buffer (25 mM HEPES, 25 mM MES [morpholineethanesulfonic acid; pH 7.0], 150 mM NaCl) at 4°C for 16 h with gentle agitation. Each virus stock was then divided into aliquots and stored at −80°C until use. Wild-type HIVRPs were generated by transfecting 293T cells in T75 flasks with 5 μg each of pMM310 and proviral DNA (R8 for CXCR4-tropic virus or R8.BaL for R5-tropic virus) by using Fugene 6 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche). Supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection and clarified by centrifugation, and aliquots were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

β-Lactamase entry assay.

A population of 1.6 × 106 293 receptor-expressing cells was harvested from a tissue culture plate with EDTA-Hanks buffered salt solution (HBSS; Gibco, Carlsbad, Calif.), washed in 10 ml of ice-cold HBSS, and collected by centrifugation at 200 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The cells were resuspended in 3 ml of ice-cold medium, and the indicated amount of the different HIVRP-pseudotyped virions were added. Polybrene was added to infections with HIVRP VSV-G virus at a final concentration of 8 μg/ml. Virions were bound to cells at 4°C for 1 h, and the cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 200 × g for 5 min at 4°C and washed with 5 ml of ice-cold HBSS. The cells were then split into two equal aliquots, harvested by centrifugation at 200 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and resuspended in ice-cold medium containing 30 mM NH4Cl or regular medium supplemented with the equivalent amount of water (vehicle control) or 3.4 μM R99 peptide (a concentration shown to maximally inhibit ASLV-A infection in cells expressing TVA [data not shown]). Cells were then plated at 1.5 × 105 cells/well in an opaque 96-well dish, and infection was allowed to proceed for 6 h at 37°C. After infection, the plate was cooled to room temperature for 5 min, and the medium was replaced with serum-free/phenol red-free medium (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) supplemented with 30 mM NH4Cl. The fluorescent substrate CCF2/AM (Panvera, Madison, Wis.) was then added from a 6× stock solution prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells were incubated in the dark at room temperature for 12 to 16 h and photographed with an Axiovert 25 microscope (Zeiss, Calif.) equipped with an AxioCam HRc digital camera attachment (Zeiss) with a β-lactamase cube (part number 41031; Chroma Technologies, Bethesda, Md.). Alternatively, the blue/green ratio of the cells was quantitated with a Cytofluor 4000 plate reader (Applied Biosystems) by excitation at 409 nm, using a 409/20-nm band-pass filter, and emission was detected with 460/40-nm and 530/25-nm band-pass filters. Experiments performed with HIV virus containing either X4 or R5 HIV Env were performed as described above with the following modifications. First, 30 mM NH4Cl or 1 μM T20 was added to SupT1 cells (105/well) expressing CCR5 or 293TVA/CXCR4/CD4 cells during the virus-cell binding step at room temperature for 1 h, and the cells were then warmed to 37°C for 4 h in the continued presence or absence of these inhibitors. Cells were loaded with CCF4/AM (a commercially available analogue of CCF2/AM), and the CCF4/AM fluorescence signal was quantified by using a BMG FluoStar plate reader (BMG, Durham, N.C.) by using a 410/24-nm excitation band-pass filter, and emission was detected via band-pass filters at 460/12 nm and 530/12 nm. Viral penetration was then calculated either by the ratio of fluorescence at 460 and 530 nm, and the results were normalized to the amount of Vpr-BlaM delivery observed for each virus in the absence of inhibitors.

For estimation of virus titer, β-lactamase experiments were performed as described above, and the number of blue cells was quantitated with a FACScalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson) after excitation at 409 nm, with monitoring of the fluorescence by using 550/30- and 450/50-nm filter sets. Virus titer was expressed as Vpr-BlaM transducing units (VTU)/milliliter.

Quantitation of early HIV reverse transcription products by quantitative PCR.

Viruses used in these experiments were produced as described above with the following modifications. After collection, the virus-containing supernatants from the different HIVRP-producing cells were treated with 40 U of DNase I/ml for 1 h at room temperature to digest the plasmid DNA used during transfection of the producer cells. The pseudotyped HIVRP virus were then concentrated by ultracentrifugation and stored as described above. The infection protocol used to monitor early HIV reverse transcription products was as described above for the β-lactamase experiments. However, after infection, the early HIV DNA products were quantitated in quantitative PCR experiments as described previously for ASLV and MLV (34), with the primers ert2f, ert2r (32), and a FAM-labeled probe ERT2 (FAM TaqMan probe; Perkin-Elmer). A dilution series of proviral DNA contained in a plasmid vector (pR9ΔEnv) was used to construct a standard curve to quantify viral DNA. Routinely, between 5 × 102 and 5 × 106 early HIV DNA molecules were accurately measured by this assay (data not shown).

RESULTS

Entry of HIV-1 cores pseudotyped with ASLV Env requires low pH.

To explore the possibility that low pH is required for ASLV uncoating instead of ASLV Env-dependent viral penetration into the cytosol, we generated a panel of hybrid viral particles that contained HIV-1 cores (designated HIVRPs) and ASLV Env proteins. It is widely accepted that HIV infection occurs by a pH-independent mechanism, proceeding in the presence of lysosomotropic agents (15, 28, 41). However, hybrid viral particles with the HIV-1 core and VSV-G, a pH-dependent viral glycoprotein, require low pH for fusion in intracellular acidic organelles (7, 11). Collectively, these data indicate that HIV-1 uncoating leading up to reverse transcription occurs by a pH-independent mechanism but that the virus can enter cells in a low-pH-dependent manner if it is assembled with a pH-dependent viral glycoprotein.

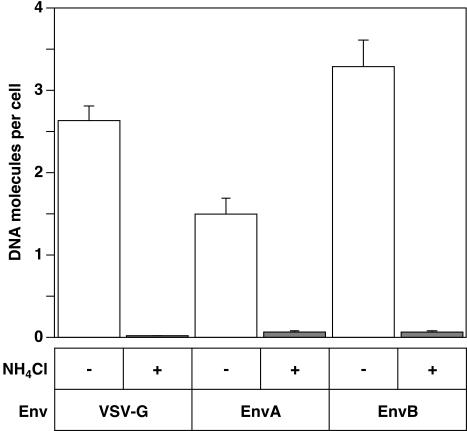

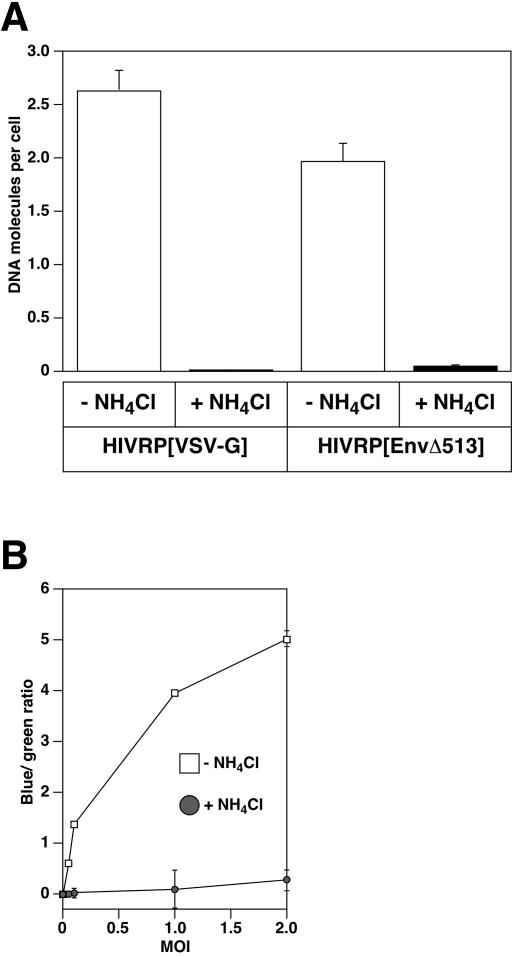

Pseudotyped HIV particles were produced with ASLV-A Env [EnvA], ASLV-B Env [EnvB] or for control purposes with VSV-G. These particles were bound to 293 cells expressing cognate ASLV receptors at 4°C, and the cells were then warmed to 37°C for 6 h, in the presence or absence of 30 mM ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) to neutralize acidic endosomal compartments. HIV-1 reverse transcription products were then quantified by using real-time PCR analysis with a primer probe set specific for minus strand strong-stop DNA, the earliest product of reverse transcription, as previously described (32). In the absence of NH4Cl, HIVRP[EnvA]-, HIVRP[EnvB]-, and HIVRP[VSV-G]-infected these cells efficiently (Fig. 1). However, addition of 30 mM NH4Cl to cells abolished infection by each of these viruses (Fig. 1). This latter result is consistent with a requirement for low pH to trigger ASLV Env-dependent entry in intracellular acidic compartments.

FIG. 1.

Infection of HIV particles bearing ASLV fusion proteins is pH dependent. For the present study we quantified the HIVRP virus titer in terms of VTU/milliliter (see Materials and Methods). HIVRP[VSV-G]-, HIVRP[EnvA]-, or HIVRP[EnvB]-pseudotyped particles were bound to 293 cells stably expressing ASLV receptors at an MOI of 1 (VTU) for 1 h at 4°C and then extensively washed to remove unbound virus. Cells were then warmed to 37°C for 6 h in the presence or absence of 30 mM NH4Cl, and DNA from these cells was prepared as described earlier (31). The number of early HIV reverse transcription products was quantitated by real-time PCR with an ABI 7000 machine (Applied Biosystems). HIV plasmid DNA was used to construct a standard curve for enumeration. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

ASLV Env-dependent viral penetration into the cytosol requires low pH.

Having established that HIV-1 particles bearing ASLV fusion proteins require low pH for infection, we next sought to determine whether low pH was required during viral penetration, defined as complete fusion of viral and cellular membranes and delivery of the viral nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm. To this end, we utilized an established HIV-based viral penetration assay that monitors delivery of the viral nucleocapsid containing an enzymatically active β-lactamase-Vpr fusion protein (Vpr-BlaM) into the cell cytoplasm, after fusion of HIVRPs (5, 32, 43).

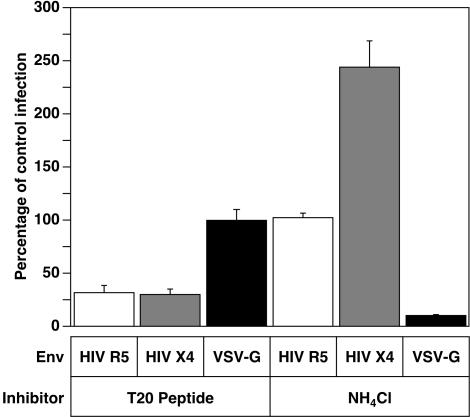

First, we established that HIV-1 particles can enter cells in a pH-dependent manner in this assay. For these experiments, HIVRP-pseudotyped particles bearing either pH-independent (X4 [NL4-3]- or R5 [BaL]-tropic HIV Env), or pH-dependent (VSV-G) fusion proteins were bound to SupT1 cells expressing CCR5, which permit infection by all three types of virus. Virus-cell complexes were formed in the presence or absence of either 30 mM NH4Cl or for control purposes with 1 μM T20 peptide, an HIV Env-dependent fusion inhibitory peptide (6, 25, 30). The cells were then incubated at 37°C for 4 h in the continued presence or absence of inhibitors, and viral penetration was quantified by analyzing the blue/green ratio of cells, after excitation at 410 nm. As expected, penetration of HIV particles bearing the pH-independent HIV X4 Env or R5 Env were resistant to inhibition by NH4Cl but were robustly inhibited in the presence of T20 inhibitory peptide (Fig. 2), demonstrating that viral fusion is required for delivery of Vpr-BlaM into the cell cytoplasm. In contrast, penetration of HIVRP[VSV-G]-pseudotyped particles was highly sensitive to inhibition by NH4Cl but was not affected by the T20 HIV-specific inhibitory peptide (Fig. 2). Interestingly, entry of HIV-tropic X4 virions was enhanced twofold in the presence of NH4Cl (Fig. 2). Given that the X4-tropic coreceptor CXCR4 is internalized rapidly, whereas the R5-tropic coreceptor CCR5 is internalized more slowly via a lipid raft pathway (44), it is possible that X4-tropic HIV particles can enter cells either from the plasma membrane or from intracellular compartment(s), but in the absence of lysosomotropic agents a fraction of the internalized particles are degraded by a low-pH-dependent mechanism. However, since the Vpr-BlaM delivery assay monitors only viral penetration, it is not possible to determine whether the HIV X4-tropic virions entering from such a putative intracellular compartment can lead to productive infection. In contrast, since CCR5 is internalized more slowly via a different endocytic pathway, R5-tropic HIV-1 entry is likely to occur solely at the plasma membrane.

FIG. 2.

The pH dependence of Vpr-BlaM delivery is dictated by the viral fusion protein. HIV X4 Env-, HIV R5 Env-, or HIV[VSV-G]-pseudotyped particles were bound to cells for 1 h at room temperature in the presence or absence of either 30 mM NH4Cl or 1 μM T20 inhibitory peptide and then warmed to 37°C for 4 h in the presence or absence of inhibitors. Cells were then loaded with CCF4/AM for 18 h at 25°C, and their fluorescence was then quantitated with a BMG FluoStar plate reader with excitation at 410/12 nm, and emission was detected by using band-pass filters at 460/12 nm and 530/12 nm. The ratio of fluorescence at 460 and 530 nm was calculated, and the results were normalized to the amount of Vpr-BlaM delivery observed for each virus in the absence of inhibitors. The results shown are mean values obtained from two independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

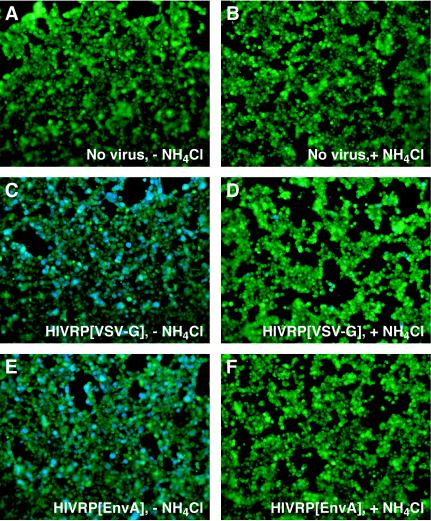

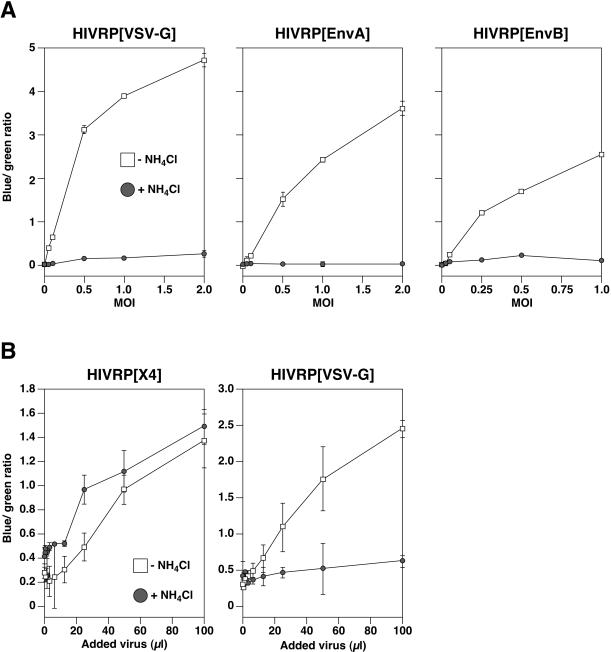

Having established that the assay can discriminate between pH-independent and pH-dependent modes of HIV-1 core delivery into the cytoplasm, we next sought to analyze the pH requirement of ASLV Env-dependent viral penetration. HIVRPs bearing EnvA, EnvB, or VSV-G were bound to 293 cells expressing cognate ASLV receptors, warmed to 37°C for 6 h in the presence or absence of 30 mM NH4Cl, and Vpr-BlaM delivery was quantitated as described above. As in SupT1 cells (Fig. 2), penetration of HIVRP [VSV]-pseudotyped particles into the cell cytosol of 293 cells was inhibited in the presence of NH4Cl (Fig. 3). Similarly, addition of NH4Cl to cells (Fig. 3 and 4A) or bafilomycin (data not shown) completely inhibited viral penetration of HIVRP[EnvA]- and HIVRP[EnvB]-pseudotyped particles. In control experiments, penetration of HIVRP-pseudotyped particles bearing ASLV Env was not observed in 293 cells lacking cognate ASLV receptors (data not shown). As expected, Vpr-BlaM delivery from HIVRPs occurred as a function of the amount of added virus, as monitored by the increase in blue/green ratio over a range of multiplicities of infection (MOIs) (Fig. 4A). However, at all MOIs tested, penetration of HIVRP[EnvA] and HIVRP[EnvB] particles into the cytosol was completely inhibited by NH4Cl addition (Fig. 4A). As a control for pH-independent viral penetration in 293 cells, we monitored X4-tropic HIV entry in 293 cells stably expressing the subgroup A ASLV receptor TVA800 and the X-4 tropic HIV receptors CXCR4 and CD4 (293TVA800/CXCR4/CD4 cells). In these cells, HIV Env-dependent penetration was slightly enhanced in the presence of 30 mM NH4Cl (Fig. 4B), similar to that observed in SupT1 cells (Fig. 2). In contrast, entry into these cell by HIVRPs pseudotyped with VSV-G (Fig. 4B) or EnvA (data not shown) remained strictly pH dependent. HIV Env-dependent viral penetration required expression of both CXCR4 and CD4 expression, since no viral entry was observed in 293 cells expressing TVA800 and CXCR4 but not CD4 (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

ASLV Env-dependent viral penetration is pH dependent. HIVRP-pseudotyped particles were bound to 293 cells stably expressing cognate ASLV receptors at an MOI of 1 (VTU) for 1 h at 4°C and then extensively washed to remove unbound virus. Cells were warmed to 37°C in the presence (B, D, and F) or absence (A, C, and E) of 30 mM NH4Cl for 6 h and then loaded with CCF2/AM for 8 to 12 h at 25°C. Cells were visualized by using an Axiovert 25 epifluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 20× objective using a β-lactamase filter set (part number 41031; Chroma Technologies). Images were captured with an AxioCam HRc camera (Carl Zeiss) and processed by using Openlab software (version 3.0.7) from Improvision, Lexington, Mass.

FIG. 4.

Quantitation of HIVRP[EnvA] and HIVRP[EnvB] viral penetration. (A) HIVRP-pseudotyped particles were bound to 293 cells stably expressing ASLV receptors at different MOIs (VTU) for 1 h at 4°C and then extensively washed to remove unbound virus. Cells were warmed to 37°C for 6 h in the presence or absence of 30 mM NH4Cl and then loaded with CCF2/AM for 8 to 12 h at 25°C. The ratio of fluorescence at 447 and 518 nm was calculated as described in Fig. 2 and was plotted against the MOI (VTU). The experiments shown are representative of three independent experiments performed in quadruplet. Error bars represent the standard deviation. (B) HIV Env-dependent viral penetration is pH independent in 293 cells. Different dilutions of a stock of HIVRPs bearing either VSV-G- or X4-tropic HIV fusion proteins were bound to 293 cells stably expressing TVA800, CXCR4, and CD4 for 1 h at room temperature in the presence or absence of either 30 mM NH4Cl and then warmed to 37°C for 4 h in the presence or absence of inhibitor. Cells were then loaded with CCF4/AM for 18 h at 25°C, their fluorescence was quantitated with a BMG FluoStar plate reader, and the blue/green ratio was calculated and plotted against the volume of virus added. The results shown are representative of data obtained in two independent experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

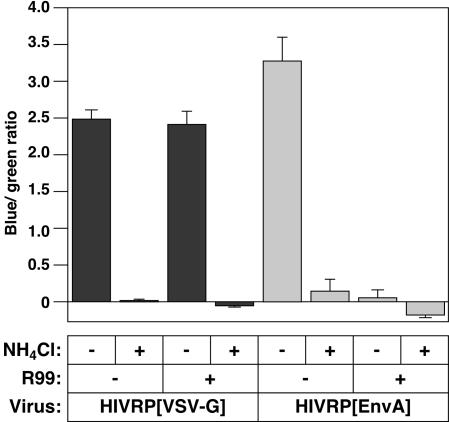

The 6HB inhibitory peptide, R99 (14), derived from ASLV Env was then used to determine whether delivery of Vpr-BlaM into the cytosol required the low-pH-dependent fusion activity of the avian viral glycoprotein. In these experiments HIVRP[EnvA]- or, for control purposes, HIVRP[VSV-G]-pseudotyped particles were bound to receptor expressing 293 cells at 4°C and then warmed to 37°C in the presence or absence of 30 mM NH4Cl or 3.4 μM R99 (a concentration of peptide that maximally inhibited ASLV-A infection [data not shown]). Penetration of HIVRP[EnvA] was completely abolished by addition of either the R99 inhibitory peptide or by addition of 30 mM NH4Cl (Fig. 5), indicating that ASLV Env-dependent fusion was required for delivery of Vpr-BlaM into the cytosol. In contrast, penetration of HIV[VSV-G] viral particles was not affected by the R99 peptide but was completely inhibited by 30 mM NH4Cl (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Fusion of HIV[EnvA] is required for Vpr-BlaM delivery. HIVRP[EnvA]- or HIVRP[VSV-G]-pseudotyped particles were bound to 293 cells stably expressing TVA at an MOI of 1 (VTU) for 1 h at 4°C. Cells were then extensively washed to remove unbound virus and warmed to 37°C for 6 h in the presence or absence of 30 mM NH4Cl or 3.4 μM R99 peptide. Cells were then loaded with CCF2/AM for 12 h at 25°C. The ratio of fluorescence at 447 and 518 nm was calculated, and the blue/green ratio of uninfected control cells was subtracted from each datum point. The experiments shown are representative of two independent experiments performed in quadruplet. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

The low pH dependence of ASLV entry is independent of the cytoplasmic tail of ASLV Env.

Earp et al. suggested that low pH may play a role in viral uncoating and not penetration into the cytosol (14). If so, then Env might be expected to participate in uncoating by transmitting a low-pH-dependent signal from its cytoplasmic tail to the viral capsid proteins. Indeed, the cytoplasmic tail of HIV Env has been proposed to interact with proteins of the HIV nucleocapsid (17, 33, 47, 48). We considered this possibility unlikely since this would require ASLV Env to impart a low-pH-dependent effect on uncoating not only on its own core but also on those of MLV (31) and HIV-1 (11; the present study). Conversely, this suggested requirement of ASLV Env uncoating would also have to be relieved when the ASLV core is assembled with MLV Env (31). Nevertheless, to test whether the cytoplasmic domain of ASLV Env plays a role in transducing a low pH signal to viral capsid proteins, we performed experiments with HIVRPs pseudotyped with a truncated form of EnvA that lacks the cytoplasmic domain, termed EnvAΔ513 (26). Viral DNA synthesis and Vpr-BlaM delivery was measured in cells infected with HIVRP[EnvAΔ513]. These studies revealed that both viral infection (Fig. 6A) and penetration (Fig. 6B) of HIVRP[EnvAΔ513]-pseudotyped particles were strictly pH dependent, ruling out a role for the cytoplasmic domain of ASLV Env in transmitting a low-pH-dependent signal to the viral core.

FIG. 6.

HIVRP[EnvAΔ513] enters cells by a pH-dependent mechanism. HIV[EnvAΔ513] virus-cell complexes were formed at 4°C at an MOI of 1 (VTU/cell) for 1 h, and cells were washed to remove unbound virus. The cells were warmed to 37°C for 6 h in the presence or absence of NH4Cl, and the amount of early HIV DNA products (A) and Vpr-BlaM delivery (B) was quantitated as described in Fig. 1 and 4, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this report we set out to test the idea put forth by Earp et al. that low pH is required for ASLV uncoating and not for ASLV Env-driven membrane fusion. This idea was tested by monitoring the infection of cells by hybrid viral particles consisting of the cores of HIV-1, a known pH-independent virus, and subgroup A or B ASLV Env. Infection of cells by these viruses was robustly inhibited by lysosomotropic agents, a finding indicative of a requirement for low pH during infection in acidic intracellular compartments (Fig. 1). Furthermore, by using a Vpr-BlaM-based assay that specifically monitors viral penetration into the cytosol independently of uncoating and reverse transcription, we mapped the requirement for low pH to a stage during fusion and delivery of the viral nucleocapsid into the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 3). These results confirm and extend previous observations that low pH is required for ASLV Env-dependent entry and not for a subsequent uncoating stage (11, 29, 31, 34, 35, 38).

Prior to conducting the present study, we considered it unlikely that low pH would be required only for viral uncoating since this model would require that ASLV Env impose a low-pH-dependent uncoating phenotype not only on its own core but also upon that of MLV, a pH-independent virus (31). Also, the apparent low-pH dependence for ASLV uncoating would also have to be relieved when the ASLV core was coupled with MLV Env (31). The results of the present study make any model that invokes a role for low pH only in ASLV uncoating even less likely since ASLV Env would have to transmit the supposed low-pH signal for uncoating to the core of HIV-1 (another pH-independent virus) by a mechanism that is independent of the cytoplasmic tail of the viral glycoprotein. Moreover, it is difficult to reconcile how ASLV Env could be involved in transmitting a low-pH-dependent signal for uncoating to the viral core if pH-independent viral delivery to the cytosol had occurred at neutral pH, as has been suggested (9, 14, 20, 23), since the viral core and Env proteins would be separated spatially in the cell. We also consider it unlikely that lysosomotropic agents act to divert virions from required sites of entry into the cytosol (14), since ASLV infection proceeds rapidly (within seconds) after lysosomotropic agent withdrawal (34), demonstrating that ASLV particles most likely reside in an acidic fusion compartment.

Earp et al. have shown that ASLV Env-driven cell-cell fusion can occur at neutral pH, arguing against a role for low pH in ASLV entry (14). In contrast, we found that fusion between ASLV Env and receptor-expressing cells only occurs under low-pH conditions (29, 31). A possible explanation for the disparity between these results is that the cell-cell fusion experiments performed by Earp et al. involved an extended incubation period (16 h), whereas our experiments involved incubating the cells together for much shorter time periods (minutes) after the addition of low pH. It is possible that in the absence of a low-pH trigger, the small amount of cell-cell fusion at neutral pH observed by Earp et al. is due to a slow conversion of ASLV Env to a fusogenic form after receptor priming, detected only after an extended period of incubation. Indeed, in similar assays performed with hepatitis C virus fusion proteins, which require low pH to elicit fusion (24, 42), a significant amount of cell-cell fusion was observed at neutral pH, whereas low pH dramatically enhanced fusion (42). Since ASLV infection proceeds past the synthesis of late DNA products in 16 h (31, 34), whereas low-pH-dependent fusion is rapid and essentially complete within 2 min (29), it is more likely that low pH represents the physiological trigger for ASLV Env-dependent fusion.

Although ASLV Env-dependent virus-cell fusion proceeds to a lipid mixing stage, after interaction with receptor at neutral pH (14), it is possible that low pH is required to elicit full fusion and cytosolic delivery of the viral nucleocapsid. Indeed, our studies demonstrating that low pH is required for viral penetration (Fig. 3 to 6) and for infection (Fig. 1) are consistent with this model. However, recent data on ASLV Env-dependent cell-cell fusion revealed that low pH is strictly required to establish a restricted hemifusion intermediate (29). Therefore, more work needs to be done to establish precisely where low pH is required in the membrane fusion reaction that leads to complete membrane merger and viral core delivery into the cytosol.

Model for ASLV Env-dependent entry.

ASLV Env interaction with cognate cell surface receptors induces a conformational change in Env (19) that results in insertion of the Env fusion peptides into the target membrane (9, 14, 23, 29). For other viruses, exposure of the fusion peptide and insertion into lipid bilayers only occurs after receipt of the physiological trigger for fusion (12, 13, 40, 45). However, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that low pH is required to trigger ASLV Env to induce complete fusion (the present study) (11, 29, 31, 34). Therefore, ASLV Env-dependent fusion presumably pauses after receptor priming, prior to receipt of the low-pH trigger for fusion. Since the R99 inhibitory peptide inhibits ASLV Env-dependent viral penetration (Fig. 5), lipid mixing, and infection (14), it is likely that fusion requires association of N- and C-terminal heptad repeats in a manner similar to HIV fusion (30). Thus, after receptor priming, ASLV Env presumably exists in a conformation where the fusion peptide is inserted into the target membrane, but where the N- and C-terminal heptad repeats have not yet formed a tight 6HB. In this receptor-primed conformation, it is possible that fusion could proceed to a lipid mixing stage, as observed in ASLV virus-cell fusion experiments (14). As prolonged exposure of the heptad repeat domains could be energetically unfavorable, given their partial hydrophobic nature, it is possible that their exposure would be transient and would only occur briefly at receptor priming. Consistent with this notion, the R99 peptide inhibits ASLV infection when added at the cell surface (Fig. 5) (14), indicating that the N-terminal heptad repeat is exposed at the plasma membrane. It is possible that partial association of heptad repeats can occur after receptor priming, but a tight 6HB does not form until incubation at low pH, which could possibly allow the N- and C-terminal heptad repeats to zipper together in a manner similar to that proposed for formation of the four-helix bundle during SNARE-mediated fusion (8). However, it remains to be determined whether ASLV Env exists in such a pre-6HB conformation after receptor priming.

Since the Ebola virus GP2 fusion protein is highly related to ASLV Env (18) and low pH is also required for Ebola virus infection (46), we predict that Ebola virus entry may also proceed by a two-step mechanism that is similar to that used by ASLV.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Schell and members of the flow cytometry facility at the University of Wisconsin Comprehensive Cancer Center for technical assistance. We also thank Bonnie Hanson and Panvera (Madison, Wis.) for technical assistance in analyzing the Vpr-BlaM data. We thank Heather Scobie for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Sean McDermott for technical assistance with capturing images of cells and Roberto Mariani and Nathaniel Landau for assistance in producing the 293TVA800/CXCR4/CD4-expressing cells. The proviral plasmids R8, R8.BaL, and pR9ΔEnv were kindly provided by Chris Aiken.

This study was supported by NIH grant CA70810 (J.A.T.Y.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adkins, H. B., J. Brojatsch, and J. A. T. Young. 2000. Identification and characterization of a shared TNFR-related receptor for subgroup B, D, and E avian leukosis viruses reveal cysteine residues required specifically for subgroup E entry. J. Virol. 74:3572-3578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnard, R. J. O., and J. A. T. Young. 2003. Alpharetroviral receptor-envelope interactions. Curr. Top. Immunol. Microbiol. 281:107-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boerger, A. L., S. Snitkovsky, and J. A. T. Young. 1999. Retroviral vectors preloaded with a viral receptor-ligand bridge protein are targeted to specific cell types. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:9867-9872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brojatsch, J., J. Naughton, M. M. Rolls, K. Zingler, and J. A. T. Young. 1996. CAR1, a TNFR-related protein, is a cellular receptor for cytopathic avian leukosis-sarcoma viruses and mediates apoptosis. Cell 87:845-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cavrios, M., C. de Noronha, and W. C. Greene. 2002. A sensitive and specific enzyme-based assay detecting HIV-1 virion fusion in primary T lymphocytes. Nat. Biotechnol. 20:1151-1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan, D. C., C. T. Chutkowski, and P. S. Kim. 1998. Evidence that a prominent cavity in the coiled coil of HIV type 1 gp41 is an attractive drug target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:15613-15617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chazal, N., G. Singer, C. Aiken, M.-L. Hammarskjold, and D. Rekosh. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles pseudotyped with envelope proteins that fuse at low pH no longer require Nef for optimal infectivity. J. Virol. 75:4014-4018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, Y. A., S. J. Scales, S. M. Patel, Y.-C. Doung, and R. H. Scheller. 1999. SNARE complex formation is triggered by Ca2+ and drives membrane fusion. Cell 97:165-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damico, R. L., J. Crane, and P. Bates. 1998. Receptor-triggered membrane association of a model retroviral glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2580-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng, H., L. Rong, W. Ellmeier, S. Choe, D. Unutmaz, M. Burkhart, P. Di Marzio, S. Marmon, R. E. Sutton, C. Mark Hill, C. B. Davis, S. C. Peiper, T. J. Schall, D. R. Littman, and N. R. Landau. 1996. Identification of a major coreceptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature 381:661-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz-Griffero, F., S. A. Hoschander, and J. Brojatsch. 2002. Endocytosis is a critical step in entry of subgroup B avian leukosis viruses. J. Virol. 76:12866-12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durrer, P., C. Galli, S. Hoenke, C. Corti, and R. Gluck. 1996. H+-induced membrane insertion of influenza virus hemagglutinin involves the HA2 amino-terminal fusion peptide but not the coiled coil region. J. Biol. Chem. 271:13417-13421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durrer, P., Y. Gaudin, R. W. Ruigrok, R. Graf, and J. Brunner. 1995. Photolabeling identifies a putative fusion domain in the envelope glycoprotein of rabies and vesicular stomatitis viruses. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17575-17581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earp, L. J., S. E. Delos, R. C. Netter, P. Bates, and J. M. White. 2003. The avian retrovirus avian sarcoma/leukosis virus subtype A reaches the lipid mixing stage of fusion at neutral pH. J. Virol. 77:3058-3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckert, D. M., and P. S. Kim. 2001. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:777-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forshey, B. M., U. von Schwedler, W. I. Sundquist, and C. Aiken. 2002. Formation of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 core of optimal stability is crucial for viral replication. J. Virol. 76:5667-5677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freed, E., and M. Martin. 1996. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 70:341-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallaher, W. R. 1996. Similar structural models of the transmembrane proteins of Ebola and avian sarcoma virus. Cell 85:477-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert, J. M., L. D. Hernandez, J. W. Balliet, P. Bates, and J. M. White. 1995. Receptor-induced conformational changes in the subgroup A avian leukosis and sarcoma virus envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 69:7410-7415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert, J. M., D. Mason, and J. M. White. 1990. Fusion of Rous sarcoma virus with host cells does not require exposure to low pH. J. Virol. 64:5106-5113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helenius, A. 1992. Unpacking the incoming influenza virus. Cell 69:577-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernandez, L., L. Hoffman, T. Wolfsberg, and J. White. 1996. Virus-cell and cell-cell fusion. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 12:627-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez, L. D., R. J. Peters, S. E. Delos, J. A. T. Young, D. A. Agard, and J. M. White. 1997. Activation of a retroviral membrane fusion protein: soluble receptor-induced liposome binding of the ALSV envelope glycoprotein. J. Cell Biol. 139:1455-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu, M., J. Zhang, M. Flint, C. Logvinoff, C. Cheng-Mayer, C. M. Rice, and J. A. McKeating. 2003. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7271-7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joshi, S. B., R. E. Dutch, and R. A. Lamb. 1998. A core trimer of the paramyxovirus fusion protein: parallels to influenza virus hemagglutinin and HIV-1 gp-41. Virology 248:20-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis, B. C., N. Chinnasamy, R. A. Morgan, and H. E. Varmus. 2001. Development of an avian leukosis-sarcoma virus subgroup A pseudotyped lentiviral vector. J. Virol. 75:9339-9344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariani, R., G. Rutter, M. E. Harris, T. J. Hope, H.-G. Krausslich, and N. R. Landau. 2000. A block to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly in murine cells. J. Virol. 74:3859-3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McClure, M., M. Marsh, and R. Weiss. 1988. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of CD4-bearing cells occurs by a pH-independent mechanism. EMBO J. 7:513-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melikyan, G. B., R. J. O. Barnard, R. M. Markosyan, J. A. T. Young, and F. S. Cohen. 2004. Low pH is required for ASLV Env-induced hemifusion and fusion pore formation, but not for pore growth. J. Virol. 78:3753-3762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melikyan, G. B., R. M. Markosyan, H. Hemmati, M. K. Delmedico, D. M. Lambert, and F. S. Cohen. 2000. Evidence that the transition of HIV-1 gp41 into a six-helix bundle, not the bundle configuration, induces membrane fusion. J. Cell Biol. 151:413-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mothes, W., A. L. Boerger, S. Narayan, J. M. Cunningham, and J. A. T. Young. 2000. Retroviral entry mediated by receptor priming and low pH triggering of an envelope glycoprotein. Cell 103:679-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munk, C., S. M. Brandt, G. Lucero, and N. R. Landau. 2002. A dominant block to HIV-1 replication at reverse transcription in simian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:13843-13848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murakami, T., and E. O. Freed. 2000. Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and alpha-helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 74:3548-3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narayan, S., R. J. O. Barnard, and J. A. T. Young. 2003. Two retroviral entry pathways distinguished by lipid raft association of the viral receptor and differences in viral infectivity. J. Virol. 74:1977-1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narayan, S., and J. A. T. Young. 2004. Reconstitution of retroviral fusion and uncoating in a cell-free system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:7721-7726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinto, L. H., L. J. Holsinger, and R. A. Lamb. 1992. Influenza virus M2 protein has ion channel activity. Cell 69:517-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skehel, J. J., and D. C. Wiley. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:531-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith, J. G., W. Mothes, S. C. Blacklow, and J. M. Cunningham. 2004. The mature avian leukosis virus subgroup A envelope glycoprotein is metastable, and refolding induced by the synergistic effects of receptor binding and low pH is coupled to infection. J. Virol. 78:1403-1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snitkovsky, S., and J. A. T. Young. 1998. Cell-specific viral targeting mediated by a soluble retroviral receptor-ligand fusion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7063-7068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stegmann, T., J. M. Delfino, F. M. Richards, and A. Helenius. 1991. The HA2 subunit of influenza hemagglutinin inserts into the target membrane prior to fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 266:18404-18410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stein, B., S. Gowda, J. Lifson, R. Penhallow, K. Bensch, and E. Engleman. 1987. pH-independent HIV entry into CD4-positive T cells via virus envelope fusion to the plasma membrane. Cell 49:659-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takikawa, S., K. Ishii, H. Aizaki, T. Suzuki, H. Asakura, Y. Matsuura, and T. Miyamura. 2000. Cell fusion activity of hepatitis C virus envelope proteins. J. Virol. 74:5066-5074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tobiume, M., J. E. Lineberger, C. A. Lundquist, M. D. Miller, and C. Aiken. 2003. Nef does not affect the efficiency of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 fusion with target cells. J. Virol. 77:10645-10650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Venkatesan, S., J. J. Rose, R. Lodge, P. M. Murphy, and J. F. Foley. 2003. Distinct mechanisms of agonist-induced endocytosis for human chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:3305-3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wahlberg, J. M., R. Bron, J. Wilschut, and H. Garoff. 1992. Membrane fusion of Semliki Forest virus involves homotrimers of the fusion protein. J. Virol. 66:7309-7318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wool-Lewis. R., and P. Bates. 1998. Characterization of Ebola virus entry by using pseudotyped viruses: identification of receptor-deficient cell lines. J. Virol. 72:3155-3160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wyma, D. J., A. Kotov, and C. Aiken. 2000. Evidence for a stable interaction of gp41 with Pr55Gag in immature human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J. Virol. 74:9381-9387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu, X., X. Yuan, Z. Matsuda, T. Lee, and M. Essex. 1992. The matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is required for incorporation of viral envelope protein into mature virions. J. Virol. 66:4966-4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zingler, K., and J. A. T. Young. 1996. Residue Trp-48 if Tva is critical for viral entry but not for high-affinity binding to the SU glycoprotein of subgroup A avian leukosis and sarcoma virus. J. Virol. 70:7510-7516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]