Abstract

Objective

Hearing loss is a commonly unmet need among adults with dementia that may exacerbate common dementia-related behavioral symptoms. Accessing traditional audiology services for hearing loss is a challenge due to high cost and time commitment. To improve accessibility and affordability of hearing treatment for persons with dementia there is a need for unique service delivery models. The purpose of this study is to test a novel hearing intervention for persons with dementia and family caregivers delivered in outpatient settings.

Design and Methods

The Memory-HEARS pilot study delivered a 2 hour in-person intervention in an outpatient setting. A trained interventionist provided hearing screening, communication strategies, and provision of and instruction using a simple over-the-counter amplification device. Caregivers (n=20) responded to questionnaires related to depression, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and caregiver burden at baseline and 1-month post-intervention.

Results

Overall, caregivers felt the intervention was beneficial and a majority of the participants with dementia wore the amplification device daily. For the depression and neuropsychiatric outcome measures, participants with high symptom burden at baseline showed improvement at 1-month post-intervention. The intervention had no effect on caregiver burden. Qualitative responses from caregivers described improved engagement for their loved ones, such as laughing more, telling more stories, asking more questions, and having more patience.

Conclusions

The Memory-HEARS intervention is a low-cost, low-risk, non-pharmacological approach to addressing hearing loss and behavioral symptoms in patients with dementia. Improved communication has the potential to reduce symptom burden and improve quality of life.

Keywords: Age-related hearing loss, amplification, communication, dementia

Introduction

There are 46 million individuals living with dementia world-wide, and the costs associated with caring for these individuals are currently estimated to be at 818 billion dollars [1]. The risk of dementia increases with age, and due to the rising life expectancy around the world, the number of individuals with dementia is expected to rise up to 131.5 million by year 2050 [2]. Hearing loss is highly prevalent in older adults, and poor communication and reduced social engagement due to hearing loss pose challenges to dementia care and symptom management [3]. Symptoms commonly associated with dementia (e.g., depression, agitation, anxiety, apathy, and irritability) may be exacerbated by poor communication resulting from age-related hearing loss [4].

Treating hearing loss, which is prevalent in nearly two-thirds of adults over 70 years-old, may represent a low-cost, low-risk approach that could improve communication and potentially reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia. One study examining this issue measured caregiver-identified problem behaviors pre- and post-hearing aid fitting in individuals with Alzheimer's disease (AD), and found some improvements for all participants [5]. For persons with dementia, untreated hearing loss can masquerade as increased symptom burden due to communication difficulties inherent with hearing loss.

Despite potentially positive benefits, there are still inherent challenges obtaining specialized hearing care services for the person with dementia, as fewer than 20% of adults with hearing loss report using hearing aids, which are the most common form of treatment [6]. Currently, best practice hearing care typically involves 4-5 visits to an audiologist and/or ENT physician over the course of 3-4 months and requires ∼$3000-5000 in out-of-pocket costs [7]. This endeavor can be challenging for any older adult, but is particularly challenging and burdensome for individuals with dementia and their caregivers. In contrast, the intervention tested here relies on personal amplification devices that are available for ∼$100-350 direct to consumers. While these devices offer less customization than a professionally-fitted hearing aid, they can provide a basic level of amplification for individuals with age-related hearing loss.

We have developed a novel intervention that provides a basic level of hearing care to the individual with dementia and hearing loss that can be delivered in a regular clinical office setting by non-specialists. The purpose of this intervention project is to test the feasibility of a basic hearing intervention delivered during a single visit to participants with dementia followed at an academic medical center. The intervention is designed to teach communication strategies and provide a basic, over-the-counter amplification device to alleviate symptom burden through improved hearing and communication. The outcome measures used to examine the effect of intervention on behavioral symptoms associated with dementia.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Johns Hopkins Memory and Alzheimer's disease Treatment Center (i.e., Memory Clinic) and the Hopkins ElderPlus Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (i.e., PACE). As part of routine clinical care, patients were offered a hearing screening during their regular Memory Clinic or PACE appointment by a physician working in both clinical sites. A patient with hearing loss was invited to participate in the pilot intervention study based on whether the patient's physician felt the patient could benefit from the intervention (i.e., the patient was not too impaired or agitated to participate). Thirty dyads participated in the study, and ten withdrew before the intervention follow-up period was complete. Reasons for withdrawal included becoming ill during the one-month post-intervention (3 persons), being hospitalized during the follow-up period (2 persons), entering hospice care, being diagnosed with cancer, and being ineligible due to TBI rather than dementia diagnosis. One person withdrew because they felt the intervention was not working. One person did not wish to use the listening device after consideration and the family withdrew. (See Table 1 for descriptive characteristics of the twenty that completed the study.) All participants and caregivers provided consent in accordance with the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Participants and caregivers were provided with meal and parking vouchers for their time and were allowed to keep the amplification device at the completion of the study period.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the participants and caregivers.

| Demographics | Participants (n=20) | Caregivers (n=20) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, years (s.d.) | 76.9 (12.4) | 64.3 (12.4) |

|

| ||

| Sex, no. female (%) | 14 (70) | 11 (55) |

|

| ||

| Race, no. (%) | ||

| White | 10 (50) | 10 (50) |

| Black | 9 (45) | 8 (40) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1 (5) | 2 (10) |

|

| ||

| Education, no. (%) | ||

| Less than High School | 6 (30) | 3 (15) |

| High School or equivalent | 5 (25) | 6 (3) |

| Associates Degree | 5 (25) | 3 (15) |

| College Degree (and higher) | 4 (20) | 7 (35) |

|

| ||

| Annual Household Income1 | ||

| < $25,000 | 9 (45) | Did not collect |

| $25,000 - $50,000 | 4 (20) | |

| > $50,000 | 2 (10) | |

|

| ||

| Relationship (caregiver only) | ||

| Spouse | Not applicable | 8 (40) |

| Child | 5 (25) | |

| Other | 7 (35) | |

|

| ||

| Hearing Thresholds2, mean (s.d.) | 48.2 (15.2) | Not applicable |

|

| ||

| Degree of Hearing Loss, no. (%) | ||

| Mild Loss (25-40 dB HL) | 8 (40) | |

| Moderate (41-60 dB HL) | 7 (35) | |

| Severe (> 60 dB HL) | 5 (25) | |

|

| ||

| Mini-Mental Status Exam, mean (s.d.) | 19.2 (5.4) | |

|

| ||

| Degree of Cognitive Impairment3, no. (%) | ||

| MCI (MMSE = 24-28) | 6 (32) | |

| Moderate (MMSE = 18-23) | 7 (37) | |

| Severe (MMSE = 0-17) | 6 (32) | |

|

| ||

| Activities of Daily Living4, mean (s.d.) | 5.1 (5.3) | |

N=15 due to missing data on this item.

Hearing thresholds are defined as the averaged response at three test frequencies (1, 2, 4 kHz) in the better hearing ear for each participant.

N=19 due to missing data on this item. Dementia diagnosis was not based on MMSE score, but categories of degree of cognitive impairment are provided to describe the sample who participated in this intervention. MCI=Mild Cognitive Impairment.

Score based on sum of responses from all 6 questions. Range of score per question 0-4, with lower values for more independent function. Total score range 0-24.

HEARS Intervention

The intervention from which the current outpatient implementation was adapted is a community-delivered hearing care intervention: Hearing Equality through Accessible Research Solutions (HEARS). The HEARS intervention was developed through a community-based participatory research approach with community members from subsidized residential housing for older adults in Baltimore City [8]. The intervention session is comprised of hearing screening, education, communication strategies, and instruction on maintenance and use of an over-the-counter amplification device. The structure of the intervention draws upon principles of Social Cognitive Theory [9] and a Human Factors approach to design [10]. A shared aspect of these underlying theories is a focus on developing self-efficacy—that is, enhancing the end-users perception of being capable to adopt new communication behaviors and use new technologies. During the intervention a training workbook guides the discussion and interactive learning components of using communication strategies and amplification to ameliorate the negative effects of hearing loss. The training workbook and intervention structure for the current experiment were adapted to meet the needs of the dementia population.

Adaptations for the dementia population focused on making the intervention shorter and simpler compared to the community-delivered intervention. For the cognitively impaired population in this study, to the extent possible, the device was chosen in advance between the participant's physician and the research team in order to provide a device that was most appropriate for the participant's cognitive function. Communication strategies were discussed first, and the details of the device were discussed last so that the person with dementia could participate more fully in communication strategies portion of the intervention.

At the onset, the family set a goal for improved communication, and all of the age-related hearing loss education, communication strategies, and instruction on device use focused on meeting the goal set by the participant/caregiver at the beginning. Finally, there was a “Teach Back” moment for the caregiver to explain how, when, and why he/she would use the device and communication strategies during a routine day.

Intervention Delivery

The intervention consisted of one 2-hour session between the participant, the caregiver, and the interventionist. During the session, the participant and caregiver were provided with information about the effects of age-related hearing loss, communication strategies, and instruction on the use and maintenance of an over-the-counter amplification device (Table 2). There was an option of two different devices: the Williams Sound Pocketalker® (Eden Prairie, MN) or the Sound World Solutions® CS-50 (Park Ridge, IL). The Pocketalker has headphones and a handheld device with a microphone and a volume control. The device can sit on a table or be worn around the user's neck on a lanyard. The CS-50 is a Bluetooth enabled device that is worn on one ear. The amplification provided by the device is programmed through a smart phone application, based on the user's responses to a hearing test administered through the device. Choice of device was made in partnership with the person with dementia, his/her caregiver, and/or his/her physician.

Table 2.

Components of the intervention, details, and associated rationale.

| Intervention Component | Details | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Set Communication Goal | The participant and/or caregiver set a communication goal at the onset. They were asked to describe a situation or challenge that created communication difficulties most often. | In order to keep the intervention session focused and patient/family-centered, all education and communication strategies and training were explained in the context of meeting the goal. |

| Hearing Loss Education | Help the participant and/or caregiver understand how age-related hearing loss affects communication and how common age-related hearing loss is. | Age-related hearing loss contributes to communication difficulties and may exacerbate dementia-related behavioral symptoms. |

| Communication Strategies | Simple strategies that reduce communication breakdowns are discussed in relation to the communication goal set by the participant/caregiver. | With or without amplification, improvements in communication rely on good use of communication strategies and behaviors |

| Provision of and Instruction on Use and Maintenance of an Over-the-Counter Amplification Device | Provide instruction and hands-on demonstration on how to use the listening device, with picture-based guidance and useful take-home guides. | Learning to use a device requires practice, and hands-on practical training is providing during the intervention session in order to build confidence for the participant and/or caregiver |

| Teach Back | The final component of the training session asks the caregiver to describe how he/she will use the communication strategies and listening device over the course of a typical day. | The teach-back is intended to improve use and retention of the material learned during the training session. The focus is on the caregiver because he/she will need to support the participant with dementia, who is less likely to independently learn the new information and skills. |

The pilot intervention was administered by three interventionists. The study audiologist (S.M.) performed the first three interventions and supervised the subsequent four interventions by two members of the research team—one of whom was a geriatrics fellow (O.N.) and the other was a research assistant (A.S.). Prior to interventions performed by the other two interventionists, the study audiologist provided a ½-day ‘train-the-trainer’ session designed to provide background information on the communication difficulties resultant from age-related hearing loss as well as provide supervised role play of providing the intervention to volunteers. The study audiologist continued to follow-up with the interventionists by phone and email regarding any challenges encountered during interventions. The interventionists provided a checklist of information covered and the amount of time each intervention required as a fidelity measure.

The interventionist followed-up with the participants ∼5 days post-intervention to ask if there were any questions or trouble-shooting needs. The 1-month post-intervention follow-up appointment was a brief session in which the participants and caregivers had an opportunity to provide feedback and the interventionist could provide trouble-shooting and support as needed. Interventions and follow-ups occurred at participants' homes if they could not come to the clinic (n=3).

Baseline Measures

Hearing was screened in a quiet office by a trained physician. Testing was performed under insert ear phone conditions using a screening audiometer (Interacoustics AD608; Eden Prairie, MN). The environmental noise was measured in all offices where hearing screening occurred and was determined to be sufficiently quiet to obtain reliable thresholds with insert earphones [11]. Hearing thresholds were estimated across the test frequencies important for hearing speech (0.5–8 kHz). Responses were provided by the patient by raising his/her hand each time a sound or tone was heard. Reliability of responses was checked by repeating one test frequency in each ear. In addition, participants subjectively rated their hearing difficulties and reported if they used or had ever used a hearing aid. Other baseline measures included Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) [12] and Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) [13] in order to characterize the cognitive and functional status of the participants. The ADLs were assigned a score of 0-4 for each of 6 questions, which resulted in a potential range of 0-24 points, with lower scores indicating more independent function.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures were related to the behaviors of the participant with dementia, burden of the informal caregiver, and communication. All measures were completed at baseline and 1-month follow-up by the caregivers. The Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory – Questionnaire (NPI-Q) assessed depressive and neuropsychiatric symptoms, and the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) assessed caregiver burden [14-16]. The CSDD has 19 questions related to depression symptoms with a possible responses of ‘Absent’, ‘Mild/Intermittent’, or ‘Severe’ and a range in scores from 0 to 38. The NPI-Q has the responder indicate ‘Absent’, ‘Mild’, ‘Moderate’, or ‘Severe’ for 12 different behaviors with a possible range in scores from 0 to 36. Finally, the ZBI provides a 5-point Likert scale from Never to Nearly Always for 22 questions. For all three measures, lower scores are better indicating less negative symptoms or burden.

The International Outcome Inventory-Alternative Intervention-Significant Other (IOI-AI-SO) [17, 18] measure was collected at 1-month post-intervention to assess improvements in communication. The IOI-AI-SO includes seven questions that address use, satisfaction, and activity limitations/benefits; the questions can be asked to assess communication outcomes as a result of the intervention as a package (i.e., understanding hearing loss, using communication strategies, and the listening device) as well as with regards to using the listening device specifically. Text responses are tailored for each question, but equate to a 5-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating more positive responses.

During the 1-month period between the intervention and follow-up, the caregiver was asked to report daily the hours of use of the amplification device per categories: < 1 hr, 1-4 hrs, 4-8 hrs, and 8+ hrs. In addition to standardized questionnaires, qualitative feedback was solicited at the 1-month follow-up appointment. A program evaluation questionnaire was developed to assess caregiver perceptions of the intervention (e.g., length of training session, usefulness of take-home materials), and the questionnaire provided open-ended questions for caregivers to write comments.

Analysis

Analysis involved descriptive statistics, pre/post comparison of standardized scores, and qualitative reports. Listening device use was tracked using daily logs to report hours of use, and results are reported as percentage of participants per hours of use. Formal quantitative analysis for pre- and post-scores on the CSDD, NPI-Q, and ZBI scales was undertaken using paired t-tests. Descriptive statistics report the mean scores on the IOI-AI-SO Likert scale as well as the percentages of response per response item. Qualitative data collected in the form of written comments was thematically categorized.

Results

Participant and caregiver characteristics are displayed in Table 1. The average age of participants with dementia was 76.9 years-old (s.d. = 12.4) and of caregivers was 64.3 years (s.d. = 12.4). Caregivers were most often the spouse of the person with dementia (40%). Five caregivers (25%) were adult children of the participants with dementia. The hearing status for participants was defined by the average of three test frequencies or tones (1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz) that are important for hearing speech. Based on the better hearing ear 8 participants (40%) had mild hearing loss (25-40 dB Hearing Level (HL)), 7 participants (35%) had a moderate hearing loss (41-60 dB HL), and 5 participants (25%) had a severe hearing loss (>60 dB HL). Cognitive abilities were measured with the MMSE (mean = 19.2, s.d. = 5.4) and physical abilities were measured by ADLs (mean = 5.1 out of 24 points, s.d. = 5.3).

Listening Device Usage and Communication Outcomes

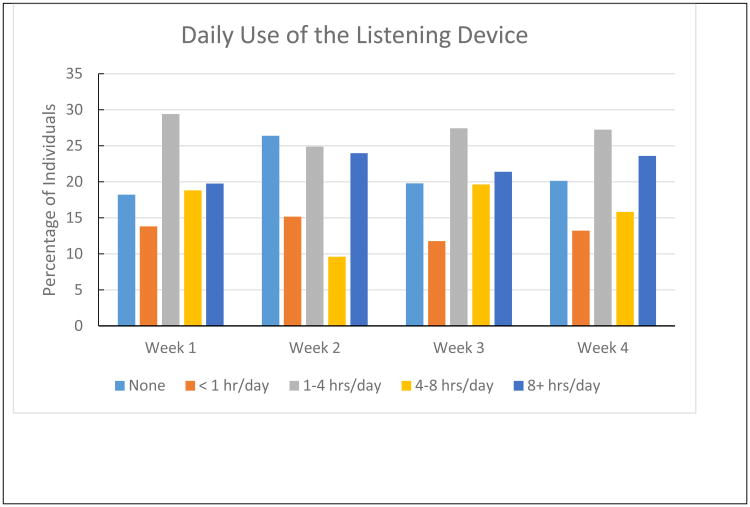

In order to assess the utility of the hearing intervention, caregivers were asked to report how often the participant used the amplification device as well as the extent to which the intervention as a whole impacted communication. Eighteen of the 20 participants returned the daily log forms for reporting hours of use at 1-month follow-up appointment. Results are reported per week to show the general stability of daily use across the entire follow-up period. By doing frequency counts of each response category (i.e., none, <1 hr/day, 1-4 hrs/day, 4-8 hrs/day, and 8+ hrs/day) across 7 day blocks of time, the results indicate that 65% of the participants wore the device at least 1 hour per day (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Daily use of the listening device per week for the first 30 days post-intervention. Results are based on caregiver report kept with a daily log entry. Frequency counts of response category per 7 day blocks were used to determine the percentage of individuals using the device in each category.

In addition to tracking device use, we used the IOI-AI-SO questionnaire to allow the caregiver to rate improvements in communication after the intervention; specifically, we asked the caregiver to think about the intervention as a whole—training session, communication strategies, and amplification device. This validated questionnaire asks the significant other about using the new strategies and device, satisfaction, activities/participation, and quality of life (Table 3). The results suggest that the intervention and the amplification device had a positive impact on communication and associated communication outcomes, and mean scores were consistent with previous literature that evaluated accessible aural rehabilitation and affordable hearing aid interventions [19-21].

Table 3.

Percent distribution to responses on the International Outcomes Inventory–Alternative Intervention–Significant Other. The caregiver was asked to think of the intervention as a whole (i.e., training session, communication strategies, and amplification device). The ordinal response scale for each item below is ordered vertically from least benefit to greatest benefit. The most commonly provided response is bolded for each category. (N=19 for Use, Benefit, Residual Activity Limitations; N=20 for Satisfaction, Residual Participation Restrictions, Impact on Others, Quality of Life)

| Use1 | Benefit2 | Residual Activity Limitations3 | Satisfaction4 | Residual Participation Restrictions5 | Impact on Others6 | Quality of Life7 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 0% | Not at all | 21% | Very much | 16% | Not at all | 5% | Very much | 5% | Very much | 5% | Worse | 0% |

| Rarely | 26% | Slightly | 11% | Quite a lot | 21% | Slightly | 25% | Quite a lot | 20% | Quite a lot | 20% | No change | 50% |

| Sometimes | 16% | Moderately | 21% | Moderate | 16% | Moderately | 15% | Moderate | 20% | Moderately | 5% | Slightly | 5% |

| Often | 37% | Quite a lot | 37% | Slight | 21% | Quite a lot | 25% | Slight | 25% | Slightly | 30% | Quite a lot | 35% |

| Almost always | 21% | Very much | 11% | None | 26% | Very much | 30% | None | 30% | Not at all | 40% | Very much | 10% |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Mean Score (Possible range = 1-5) | |||||||||||||

| 3.5 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.1 | |||||||

Use: Think about how much your partner used what he or she learned in the HEARS Intervention over the past two weeks. On an average day, how many hours did your partner use it?

Benefit: Think about the situation where you most wanted your partner to hear better, before doing the HEARS Intervention. Over the past two weeks, how much has the HEARS intervention helped in that situation?

Residual Activity Limitations: Think again about the situation where you most wanted your partner to hear better. When your partner uses what he or she learned during the HEARS Intervention, how much difficulty does he or she STILL have in that situation?

Satisfaction: Considering everything, do you think the HEARS Intervention was worth the trouble?

Residual Participation Restrictions: Over the past two weeks, using what he or she learned in the HEARS Intervention, how much have your partner's hearing difficulties affected the things YOU can do?

Impact on Others: Over the past two weeks, using what he or she learned in the HEARS Intervention, how much were YOU bothered by your partner's hearing difficulties?

Quality of Life: Considering everything, how much has the HEARS Intervention changed YOUR enjoyment of life?

Finally, results of qualitative data provided by caregivers and participants with dementia via a program evaluation questionnaire completed at the 1-month follow up appointment fit into three broad categories: Social Activity/Engagement, Functional Interactions, and Limitations of the Device (Table 4). In terms of social activity, some responses pertained directly to communication (e.g., ability to talk on the phone), but some addressed more global engagement, such as laughing more, telling more stories, and reading more often. The primary complaint provided in the written comments had to do with the headphones poorly fitting, especially on female participants.

Table 4.

Caregiver comments regarding use of the hearing device from the program evaluation survey.

| Category | Exemplars |

|---|---|

| Social Activity and Engagement |

“She began telling her historical stories more accurately. She asked questions in smoother sentences…Her willingness to make decisions is stronger. Such decisions have made more sense. Note: The dimensha [sic] is still there, but it seems to take more of a back seat in her life.” “Phone conversations!” “My mother listens to music more and when she's watching television she seems to understand what she's watching and laughs or smiles at appropriate times. She also speaks louder, asks more questions, and seems to follow the conversation better. She is reading more often.” |

| Functional Interactions | “I can work faster e.g. cleaning her, etc. since I don't have to repeat. Before, I lost 15-20 min.” |

| Limitations | “[The participant] needs a smaller headpiece. It doesn't fit right, especially with [her] glasses on.” |

|

| |

| Comments from participants with hearing loss and dementia | |

| |

Neuropsychiatric and Behavioral Outcomes

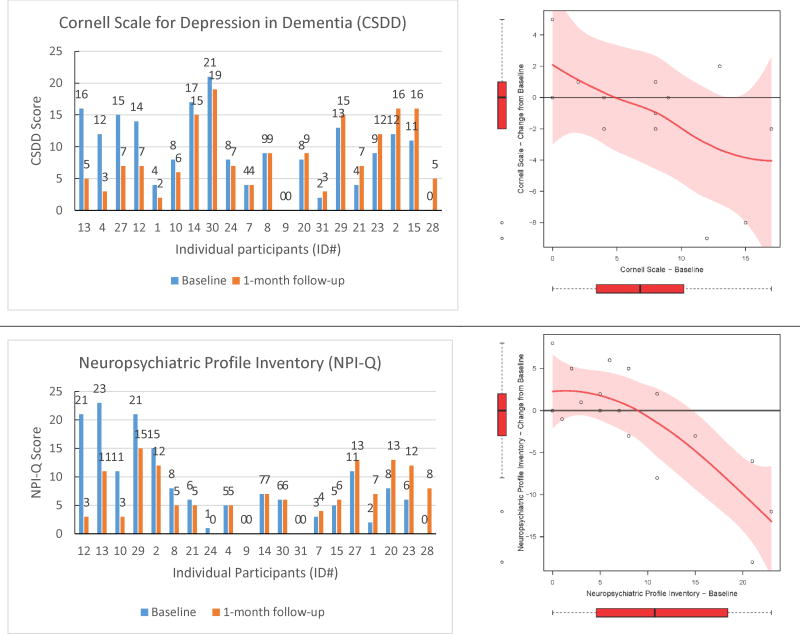

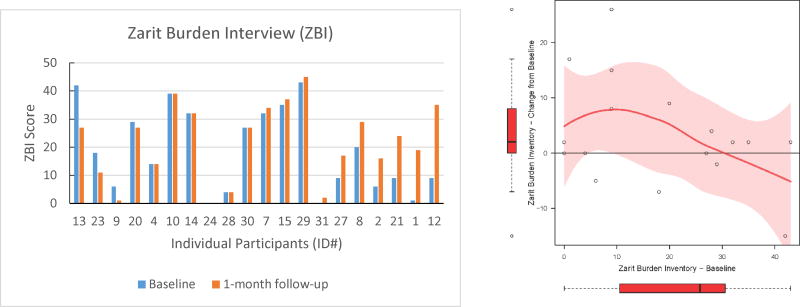

In this feasibility study, we also explored the effect of the hearing intervention on behavioral symptoms and caregiver burden associated with dementia. All caregivers provided proxy responses at baseline and 1-month follow-up on depression (CSDD) and neuropsychiatric (NPI-Q) symptoms of the participants as well as caregiver burden ratings (ZBI). Figure 2 shows the pre- and post-intervention scores for all individuals arranged by greatest to least improvement (left panels) as well as change in score as a function of the individual's baseline score (right panels). Using paired t-tests, we observed no significant mean change between the pre- and post-intervention scores for CSDD (mean difference = 1.15 (95% CI: -1.13, 3.44), df = 12, p = 0.29), NPI-Q (mean difference = 1.22 (95% CI: -2.01, 4.46), df = 17, p = 0.44), or ZBI (mean difference = -3.41 (95% CI: -8.34, 1.52), df = 16, p = 0.16). However, change scores for CSDD, NPI-Q, and ZBI as a function of pre-intervention score, suggest that those individuals with the greatest scores before intervention on CSDD and NPI-Q demonstrated the greatest improvement after treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Individual data for each pre- and post-intervention outcome measure. The left panels show pre-and post-scores for each individual arranged from greatest to least improved participant. The right panels show the change score from pre- to post-intervention as a function of baseline score. The change score figure was restricted to participants who had no missing data on the pre- or post-intervention questionnaires (CSDD: n=13; NPI-Q: n=18; ZBI: n=17). The data trends are shown with lowess curves and 95% confidence interval shading. Box plots reflect the variability of change scores and baseline scores in the sample.

Qualitative Feedback

Program evaluation was an important component in order to assess the feasibility of this intervention. Results regarding satisfaction with the intervention session, the training materials, and communication after the intervention are provided in Table 5. Overall, caregivers reported at least some benefit from the program (90%), that the training session was useful (89%), and that they thought others would benefit from the program (94%). Additionally, representative comments related to the listening device are shown in Table 4.

Table 5.

Feedback provided by caregivers on the Program Evaluation survey.

| Not at all n (%) | Some or A great deal n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Overall, how much do you think you benefited from this program? | 2 (10) | 17 (90) |

| How much did the program help you understand how to communicate better? | 1 (5) | 19 (95) |

| How helpful was it to set a communication goal? | 3 (17) | 14 (82) |

| How useful was the training session? | 2 (11) | 16 (89) |

| Do you think the HEARS Intervention program would help others in similar situations? | 1 (5) | 17 (94) |

Conclusions

Our results from this pilot study suggest that some individuals with dementia and hearing loss and their caregivers may benefit from a basic hearing intervention that is low cost and accessible. The novel intervention can be delivered in a geriatric clinic setting and is tailored to the basic communication needs for persons with dementia and hearing loss and their caregivers. Importantly, pre/post intervention data in this feasibility study suggest that those participants with high symptom burden at baseline may show reductions in depressive and/or neuropsychiatric symptoms. Specifically, 43% of participants with clinically meaningful depressive symptoms at baseline (CSDD ≥ 8) showed improvement at follow-up, and 40% of participants showed improvement on the NPI-Q. These results suggest the potential to provide patients and families with a non-pharmacological, simple, low-risk, low-cost intervention that may alleviate symptom burden for dementia patients and their caregivers.

While group mean scores pre- and post-intervention did not indicate significant differences, the CSDD and NPI-Q showed the expected pattern of improvements post-intervention particularly for those participants with the more severe scores at baseline. This highlights the important issue of how to best target the individuals likely to benefit from a hearing intervention. If the main goal of the hearing intervention is to reduce depression and neuropsychiatric symptoms, then it follows that those individuals with high scores on depression and/or other neuropsychiatric measures would be the target audience for such an intervention. As such, the hearing intervention would be considered a preliminary approach to addressing symptoms that might otherwise be commonly addressed with medication.

Importantly, persons with dementia without substantive depression and neuropsychiatric symptoms would also likely benefit from a hearing loss intervention. Age-related hearing loss is associated with increased cognitive load due to the increased challenge of interpreting a degraded peripheral signal (i.e., speech) [22]. Because individuals with dementia already have cognitive deficits, they may be particularly inhibited when it comes to processing speech in the presence of even a mild hearing impairment. Moreover, given the treatment goal of maintaining social engagement for persons with dementia [23], not addressing hearing loss immediately disadvantages a person with both hearing loss and dementia. With these motivations in mind, intervening in people at the earliest stages of cognitive impairment or dementia may help maintain social engagement and communication and help reduce further decline.

We observed that our hearing intervention resulted in little improvement in caregiver burden. One explanation for this finding may be that adopting new communication strategies (i.e., behavior change) and learning to and remembering to use a new technology actually increased burden for some caregivers in the short term. Non-intervention-related factors may also coincidentally have increased caregiver burden. For example, two participants required hospitalization during the 1-month follow-up period. Future studies incorporating specific questions probing reason for caregiver burden and querying specific communication situations may indicate if the burden associated with poor communication was alleviated through the intervention. For example, one caregiver reported that the morning routine was sped up by 15-20 minutes because the participant was better able to hear and follow instructions after the intervention.

Finally, those caregivers who provided qualitative comments described improvements that went beyond improvements in basic communication. The broad range of improvements suggest that for some participants, the hearing intervention “lifted a veil” that allowed them to be connected with life in a renewed way. For example, according to caregiver comments, some participants laughed more, read more, asked more questions, told stories that made more sense, and were more willing to make decisions.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this small feasibility study. One limitation is the lack of control group; it is difficult to estimate what the typical variation in outcome measures would be from month to month with no treatment. Future investigations will rely on a delayed treatment control group and perhaps a factorial design to address the effects of the communication training and the amplification device independently. Another limitation has to do with the lack of statistical analyses of our preliminary findings due to the small sample tested in this feasibility study. Nevertheless, the data patterns of improvement in neuropsychiatric and depressive symptoms suggest an efficacy signal that will be tested in a future randomized control trial. Finally, our ability to measure how often the person is using the amplification device and whether use of the device continues after the study relies exclusively on caregiver-report. Traditional hearing aids do have the capability of tracking hours of use, however, as the nature of our project is to rely on low-cost solutions, the amplification devices issued in this study did not have this capability.

Summary

Novel approaches for reducing behavioral symptoms associated with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and other dementias are needed given the increasing prevalence of dementia and the limited efficacy and high costs and risks of pharmacologic approaches [24, 25]. Future investigation of this hearing care intervention will employ a randomized control trial approach and seek to identify the best target population (e.g., those individuals with higher symptom burden) and delivery method (e.g., home-based service). A critical component of future investigations will be formal cost analyses, including devices as well as personnel costs. One potential opportunity is to explore a team approach that includes clinicians, nurses, and rehabilitation professionals. Addressing hearing loss in older adults with dementia may represent a low-cost, low risk intervention to improve the daily functioning of individuals with dementia.

Article Summary.

For older adults with dementia, age-related hearing loss may exacerbate negative behavioral symptoms. The purpose of this study is to test a low-cost, nonpharmacological approach to addressing hearing loss and behavioral symptoms in persons with dementia. Participants with dementia and a family caregiver attended a one-hour hearing care intervention with instruction in the use of and provision of an over-the-counter amplification device. For some participants, there were substantial improvements in depressive and/or neuropsychiatric symptom burden.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIDCD K23DC011279 (FRL), NIDCD/T32DC000027 (CLN), NIH/NIA K23AG043504 (ESO), the Roberts Fund (ESO), the Ossoff Family Fund (ESO) the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation (FRL, SKM), Johns Hopkins Alzheimer's Disease Research Center P50AG005146 (FRL, SKM). This publication was made possible, in part, by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, which is funded in part by UL1TR001079 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) a component of the NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS or NIH.

Funding Sources: This work was supported by NIH/NIDCD K23DC011279 and T32DC000027, NIH/NIA K23AG043504, the Roberts Fund, the Ossoff Family Fund, the Eleanor Schwartz Charitable Foundation, Johns Hopkins Alzheimer's Disease Research Center P50AG005146, and Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research UL1TR001079.

Footnotes

Previous Presentation: Portions of this work have been presented at the American Auditory Society Annual Scientific Meeting (Scottsdale, AZ; 2015) and the Alzheimer's Association International Conference (Washington, DC; 2015).

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Mamo reports that meeting expenses were paid for by the Oticon Foundation. Dr. Lin reports being a consultant to Cochlear, on the scientific advisory board for Autifony and Pfizer, and a speaker for Med El and Amplifon. For the remaining authors none were declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Prince M, W A, Guerchet M, Ali GC, Wu YT, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia. London: 2015. Alzheimer's Disease International. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duba AS, et al. Determinants of disability among the elderly population in a rural south Indian community: the need to study local issues and contexts. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(2):333–41. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin FR, Albert M. Hearing loss and dementia - who is listening? Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(6):671–3. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.915924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen-Mansfield J, Taylor JW. Hearing aid use in nursing homes. Part 1: Prevalence rates of hearing impairment and hearing aid use. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(5):283–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer CV, et al. Reduction in caregiver-identified problem behaviors in patients with Alzheimer disease post-hearing-aid fitting. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1999;42(2):312–328. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4202.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chien W, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):292–3. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strom KE. Hearing Review 2013 dispenser survey: Dispensing in the age of internet and big box retailers. Hearing Review. 2014;21(4):22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nieman CL, et al. The Gerontological Society of America: 67th Annual Scientific Meeting. Wasthington, D.C.: The Gerontologist; 2014. The Baltimore HEARS Study: A Novel Community-Based Hearing Health Care Intervention. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisk AD, et al. Human Factors & Aging Series. 2nd. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group; 2009. Designing for Older Adults: Principles and Creative Human Factors Approaches. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frank T. ANSI update: maximum permissible ambient noise levels for audiometric test rooms. Am J Audiol. 2000;9(1):3–8. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2000/003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz S, et al. Studies of Illness in the Aged. The Index of ADL: A Standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963;185:914–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexopoulos GS, et al. Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23(3):271–84. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufer DI, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–9. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649–55. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.6.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox RM, Alexander GC, Beyer CM. Norms for the international outcome inventory for hearing aids. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003;14(8):403–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noble W. Extending the IOI to significant others and to non-hearing-aid-based interventions. Int J Audiol. 2002;41(1):27–9. doi: 10.3109/14992020209101308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramer SE, et al. A home education program for older adults with hearing impairment and their significant others: a randomized trial evaluating short- and long-term effects. Int J Audiol. 2005;44(5):255–64. doi: 10.1080/14992020500060453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McPherson B, Wong ET. Effectiveness of an affordable hearing aid with elderly persons. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27(11):601–9. doi: 10.1080/09638280400019682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parving A, Christensen B. Clinical trial of a low-cost, solar-powered hearing aid. Acta Otolaryngol. 2004;124(4):416–20. doi: 10.1080/00016480310000638a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tun PA, McCoy S, Wingfield A. Aging, hearing acuity, and the attentional costs of effortful listening. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(3):761–766. doi: 10.1037/a0014802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):361–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salzman C, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(6):889–98. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]