Abstract

The patS gene encodes a small peptide that is required for normal heterocyst pattern formation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. PatS is proposed to control the heterocyst pattern by lateral inhibition. patS minigenes were constructed and expressed by different developmentally regulated promoters to gain further insight into PatS signaling. patS minigenes patS4 to patS8 encode PatS C-terminal 4 (GSGR) to 8 (CDERGSGR) oligopeptides. When expressed by PpetE, PpatS, or PrbcL promoters, patS5 to patS8 inhibited heterocyst formation but patS4 did not. In contrast to the full-length patS gene, PhepA-patS5 failed to restore a wild-type pattern in a patS null mutant, indicating that PatS-5 cannot function in cell-to-cell signaling if it is expressed in proheterocysts. To establish the location of the PatS receptor, PatS-5 was confined within the cytoplasm as a gfp-patS5 fusion. The green fluorescent protein GFP-PatS-5 fusion protein inhibited heterocyst formation. Similarly, full-length PatS with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag inhibited heterocyst formation. These data indicate that the PatS receptor is located in the cytoplasm, which is consistent with recently published data indicating that HetR is a PatS target. We speculated that overexpression of other Anabaena strain PCC 7120 RGSGR-encoding genes might show heterocyst inhibition activity. In addition to patS and hetN, open reading frame (ORF) all3290 and an unannotated ORF, orf77, encode an RGSGR motif. Overexpression of all3290 and orf77 under the control of the petE promoter inhibited heterocyst formation, indicating that the RGSGR motif can inhibit heterocyst development in a variety of contexts.

The regulation of cellular differentiation and pattern formation are fundamental features of developmental biology that can be studied in heterocystous cyanobacteria. When combined nitrogen is depleted from the environment, 8 to 10% of vegetative cells in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena (Nostoc) sp. strain PCC 7120 differentiate into nitrogen-fixing heterocysts, which are distributed in a semiregular pattern along filaments (12, 25, 34). It is clear that cell-to-cell communication must be involved in the control of heterocyst pattern formation (6, 11, 35, 37).

The PatS peptide is proposed to control heterocyst pattern formation by lateral inhibition, such that a diffusible PatS signal produced by differentiating cells inhibits nearby cells in the same filament from differentiating (36). In Anabaena strain PCC 7120, the patS gene contains two potential ATG start codons and could encode 13- or 17-amino-acid polypeptides (36). The closely related species Anabaena variabilis contains an identical patS open reading frame (ORF) at the nucleotide level. However, the patS ortholog in Nostoc punctiforme lacks the upstream start codon and contains only 13 codons (26). patS overexpression inhibits heterocyst formation in Anabaena strain PCC 7120, and a patS null mutant forms heterocysts in nitrate-containing medium and forms multiple contiguous heterocysts (Mch phenotype) after a nitrogen step-down (36). The last five carboxy-terminal amino acid residues are important for the function of patS. Missense mutations affecting these residues fail to inhibit heterocyst formation, and a synthetic pentapeptide corresponding to these 5 amino acids (PatS-5, RGSGR) inhibits heterocyst development at submicromolar concentrations. A synthetic oligopeptide corresponding to the last four patS-encoded amino acids (PatS-4, GSGR) has much lower heterocyst inhibition activity (36).

After nitrogen step-down, wild-type filaments produce about 10% single heterocysts in a semiregular pattern, but a patS null mutant produces an Mch phenotype with about 30% heterocysts. From these data alone, PatS could either be directly responsible for producing a normal pattern by lateral inhibition or be required for a normal response to another, as yet unidentified, diffusible inhibitor produced by differentiating cells. This was tested by bathing filaments of a patS mutant with 60 nM PatS-5 pentapeptide, which reduced the number of heterocysts to about 10% but failed to restore a normal pattern (36). This experiment shows that exposure to uniform PatS concentrations cannot produce a normal pattern. However, expression of the patS gene from the heterocyst-specific hepA promoter complemented the patS null mutant and produced a nearly normal pattern (36). These data suggest that a gradient of PatS signal originating from differentiating cells is required to produce a normal pattern.

A patS-gfp transcriptional fusion showed that patS is expressed early during heterocyst development in differentiating cells (36, 37). The patS-gfp reporter strain showed that patS transcription was localized to individual cells or small groups of cells by 8 to 10 h after the nitrogen step-down. By 12 to 14 h, bright fluorescence was present in mostly single cells, with a pattern that resembled the wild-type heterocyst pattern. At 18 h after the nitrogen step-down, the green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence was almost exclusively from proheterocysts. The temporal and spatial pattern of patS expression strongly supports the lateral-inhibition model in which the patS product, possibly a processed C-terminal peptide, acts as an intercellular signal produced by differentiating heterocysts to inhibit the differentiation of neighboring cells. The differentiating PatS-producing cells must themselves be refractory to the PatS signal (36); however, the mechanism of this immunity to PatS inhibition is not yet known.

Diffusible signal molecules influence development in several prokaryotic organisms including Bacillus subtilis, Myxococcus xanthus, and Streptomyces spp. (17, 20). Receptor molecules for these signals may be present either outside the cell or within the cytoplasm. For example, ComX and PhrA are two well-characterized signal peptides regulating competence and sporulation in the gram-positive bacterium B. subtilis (13, 27, 28). The receptor for ComX is in the plasma membrane, while the receptor for PhrA is located inside the cytoplasm. ComX is a modified peptide pheromone used by B. subtilis to regulate the transcription of quorum-responsive genes. A 55-amino-acid ComX precursor is cleaved by ComQ to produce a 10-amino-acid peptide, which is modified at a tryptophan residue and exported as an active intercellular signal (1). The ComX receptor, ComP, is a membrane-bound histidine protein kinase (30). ComP and the ComA transcription factor form a two-component system that regulates competence development (13, 21).

The PhrA precursor is a 44-amino-acid polypeptide that is processed to produce the C-terminal pentapeptide ARNQT, which is the active signal (31). In target cells, PhrA pentapeptide is imported by the oligopeptide permease system (Opp) (29). The PhrA receptor, RapA, is a phosphatase located in the cytoplasm. PhrA pentapeptide inhibits the phosphatase activity of RapA on Spo0F-P, which is a component of the phosphorelay controlling the initiation of sporulation (16, 27, 28).

Lazazzera et al. expressed the active PhrA pentapeptide inside cells from a minigene to establish that the PhrA receptor was in the cytoplasm (22). Expression of the phrA minigene was able to rescue the sporulation defect of a phrA mutant (22, 30). They also used minigenes to study CSF, the competence- and sporulation-stimulating factor. Expression of a phrC minigene encoding the mature CSF pentapeptide showed that CSF targets are intracellular (22).

In this study, we used patS minigenes and gene fusions in Anabaena strain PCC 7120 to show that the PatS receptor is likely to be located in the cytoplasm and that, unlike the wild-type PatS signal, the patS5 minigene product cannot function in cell-to-cell signaling. Our results are consistent with recent data indicating that HetR is likely to be the PatS receptor (15). HetR is a key activator of heterocyst development (5) that was previously shown to be positively autoregulated (2) and to have autoproteolytic activity (38). Zhao's laboratory has now shown that HetR forms a homodimer with DNA-binding activity and that this DNA-binding activity is inhibited in vitro by synthetic PatS pentapeptide (15).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Anabaena strain PCC 7120 and its derivatives were grown in BG-11 or BG-110 (which lacks sodium nitrate) medium at 30°C as previously described (10). For strains containing shuttle plasmids, cultures were supplemented with neomycin at 25 μg/ml for both liquid and solid media. The patS null mutant AMC451 (36) and its derivatives were grown in media supplemented with spectinomycin and streptomycin at 1 μg/ml each. For heterocyst inductions, filaments from actively growing cultures with an optical density at 750 nm of about 0.3 were collected by centrifugation and washed twice with water before being transferred to BG-110 as previously described (37).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Derivation and/or relevant feature(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Anabaena strains | ||

| PCC 7120 | Wild type | R. Haselkorn |

| AMC451 | ΔpatS | 36 |

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH10B | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 endA1 araD139 Δ(ara, leu)7697 galU galK λ−rpsL nupG Smr | GIBCO BRL Life Technologies |

| AM1359 | DH10B containing pRL623 and pRL443; conjugal donor strain | 8, 36 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAM504 | pDU1-based shuttle vector; Kmr Nmr | 32 |

| pAM505 | pDU1-based shuttle vector; Kmr Nmr | 36 |

| pAM1630 | 0.9-kb EcoRV-SalI fragment containing PhepA from pRL1905 cloned in pBluescript II KS(+); Apr | This study |

| pAM1690 | PrbcL-patS cloned in pAM504 | 23 |

| pAM1715 | PhepA-patS cloned in pAM504 | 36 |

| pAM1951 | PpatS-gfp cloned in pAM505 | 36 |

| pAM1954 | PrbcL-gfp cloned in pAM504 | 36 |

| pAM1956 | Promoterless gfp in pAM505 | 36 |

| pAM2269 | petE promoter in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2424 | PpetE-patS5 cloned in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2506 | PrbcL-patS5 cloned in pBluescript II SK(+) | This study |

| pAM2525 | PpetE-patS4 cloned in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2526 | PpetE-patS6 cloned in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2527 | PpetE-patS8 cloned in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2528 | PpatS-patS5 cloned in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2529 | PpetE-patS7 cloned in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2532 | PpatS-patS5 cloned in pBluescript II SK(+) | This study |

| pAM2537 | PrbcL-patS5 from pAM2506 cloned in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2600 | SapI-6His-ClaI sequence cloned in pUC18 downstream of lacZ | 23 |

| pAM2770 | Shuttle vector containing PpetE; Kmr Nmr | 23 |

| pAM2811 | PhepA-patS5 cloned in pBluescript II SK(+) | This study |

| pAM2814 | 0.8-kb SalI fragment containing PhepA-patS5 from pAM2811 cloned in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2816 | PhepA-patS5 from pAM2811 cloned in pAM1956 to form PhepA-patS5-gfp transcriptional fusion | This study |

| pAM2821 | 668-bp XhoI-SapI PCR fragment containing patS cloned in pAM2600 to form patS-6His | This study |

| pAM2826 | 688-bp XhoI-ClaI fragment carrying patS-6His from pAM2821 cloned in shuttle vector pAM2770 | This study |

| pAM2873 | 1.7-kb PCR fragment containing PrbcL-gfp-patS5 translational fusion cloned in pAM504 | This study |

| pAM2898 | PpetE-orf77 cloned in shuttle vector pAM2770 | This study |

| pAM2918 | PpetE-all3290 cloned in shuttle vector pAM2770 | This study |

| pRL1905 | hepA upstream region containing PhepA in pRL487 | 39 |

Escherichia coli strains were maintained in Lennox L broth liquid or agar-solidified medium. For plasmid preparation, strains were grown in 0.5× TB liquid medium as described previously (10). E. coli strain DH10B was used for plasmid maintenance, and the media were supplemented with appropriate antibiotics as required.

Copper-inducible expression from the petE promoter.

patS minigenes, all3290, and orf77 were expressed from the copper-inducible petE promoter (PpetE) derived from plasmid pPet1 (5). BG-11 medium, with CuSO4 omitted, was used for copper-deficient growth conditions. As a precaution to prevent copper contamination, disposable plasticware was used instead of glassware for medium preparation and during the assay (5). All solutions were filter sterilized instead of being autoclaved. To induce the PpetE promoter, dissolved CuSO4 was added to copper-deficient BG-11 medium at a final concentration of 0.4 μM CuSO4.

For heterocyst induction with or without copper, rapidly growing filaments from standard BG-11 were collected and washed twice with copper-deficient BG-110 medium. The filaments were then transferred into plastic culture tubes containing 3 ml of BG-110 with or without Cu2+ or into 24-well tissue culture plates (Falcon) containing 2 ml of BG-110 with or without Cu2+. The cultures were incubated for 48 h under standard growth conditions. Filaments were scored for heterocyst frequency; detached heterocysts were not scored (37).

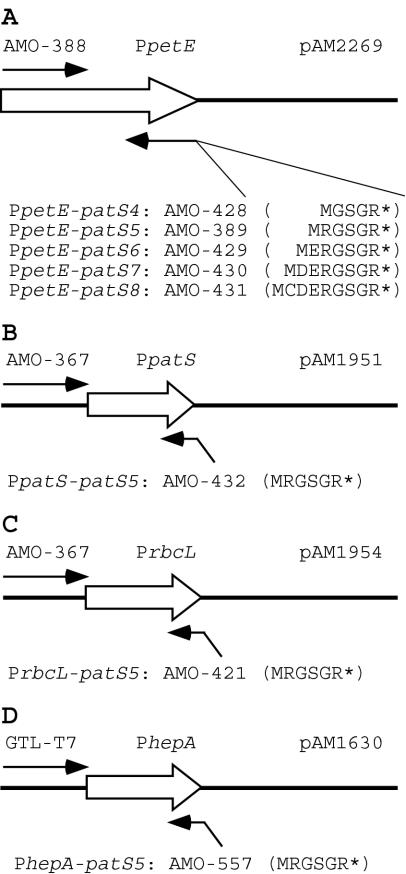

patS minigenes.

patS minigenes designated patS4 to patS8 encode PatS C-terminal oligopeptides from 4 (GSGR) to 8 (CDERGSGR) amino acids, respectively. patS minigenes were expressed from different promoters by being fused to the native start codon downstream of the promoter sequence (Fig. 1; Table 2). Each construct was generated by PCR with a forward primer complementary to the template containing the desired promoter. Each reverse primer consisted of two parts. The 5′ portion encoded the minigenes and a stop codon, and the 3′ portion (approximately 17 bases) was complementary to the promoter template such that the start codon was fused to the minigene sequences. The high-fidelity Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche) was used in the PCR to generate blunt-end products.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of patS minigene constructs. Each PCR product results in a promoter upstream region (open arrows) fused at the start codon to a patS minigene sequence, ending with a UAG stop codon encoded by the 5′ end of the reverse primer. The 3′ ends of the reverse primers are complementary to the promoter template. (A) Construction of PpetE-patS4 to PpetE-patS8. pAM2269 was used as the PCR template for PpetE. The forward primer was AMO-388 for all five constructions. The PatS peptides encoded by the reverse primers are shown. (B) To generate PpatS-patS5, pAM1951 was used as the PCR template for PpatS and the patS5 sequence was encoded on the reverse primer AMO-432. AMO-367 was the forward primer. (C) To generate PrbcL-patS5, pAM1954 was used as the PCR template for PrbcL and the patS5 sequence was encoded on the reverse primer AMO-421. AMO-367 was the forward primer. (D) To generate PhepA-patS5, pAM1630 was used as the PCR template for PhepA and the patS5 sequence was encoded on the reverse primer AMO-557. GTL-T7 was the forward primer. The closed arrows indicate PCR primers. *, stop codon. Diagrams are not to scale.

TABLE 2.

PCR primer sequences used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| GTL-T7 | aatacgactcactatag |

| AMO-367 | acccgtcgaactgcgcgcta |

| AMO-369 | cgctctgctgaagccag |

| AMO-388 | gatccccgggtaccgagctcga |

| AMO-389 | CTATCTACCACTACCGCGCATggcgttctccta |

| AMO-421 | CTATCTACCACTACCGCGCATatgtatatct |

| AMO-428 | CTATCTACCACTACCCATggcgttctccta |

| AMO-429 | CTATCTACCACTACCGCGCTCCATggcgttctccta |

| AMO-430 | CTATCTACCACTACCGCGCTCATCCATggcgttctccta |

| AMO-431 | CTATCTACCACTACCGCGCTCATCACACATggcgttctccta |

| AMO-432 | CTATCTACCACTACCGCGCATaatcttaaaatcggtg |

| AMO-557 | CTATCTACCACTACCGCGCATgtcaacccagctaat |

| AMO-569 | aggacctcgaggaaaagtagggttaagtaaacgggc |

| AMO-583 | gtcctggctcttccgcatctaccactaccgcgctc |

| AMO-617 | CTATCTACCACTACCGCGtttgtatagttcatc |

| AMO-659 | aaccaacatatggtgattcgtccttgtaaacc |

| AMO-660 | aaccaacccgggtcatggcttgactacctcc |

| AMO-661 | accaacatatggtgccaccattatcaaacacag |

| AMO-662 | aaccaacccgggttacctaacagaatcagttcttaagc |

Capital letters indicate patS minigene sequences.

Plasmid constructions.

DNA fragments (∼500 bp) containing PpetE-patS4 to PpetE-patS8 minigenes (Fig. 1A) were inserted into pBluescript II SK(+) at the EcoRV site, and the BamHI-SmaI fragments from the resulting plasmids were inserted into conjugal shuttle vector pAM504 (32) at the same sites to produce plasmids pAM2525, pAM2424, pAM2526, pAM2529, and pAM2527, respectively. The BamHI-digested PCR product PpatS-patS5 (∼750 bp) (Fig. 1B) was inserted into pAM504 between BamHI and SmaI sites, resulting in plasmid pAM2528. The blunt-ended PCR product PrbcL-patS5 (∼400 bp) (Fig. 1C) was inserted into the pBluescript II SK(+) EcoRV site, resulting in pAM2506. The PvuII fragment containing the PrbcL-patS5 construct from pAM2506 was inserted into pAM504 at the SmaI site, resulting in plasmid pAM2537. The BamHI-digested PCR product PhepA-patS5 (∼800 bp) (Fig. 1D) was inserted into pBluescript II SK(+) between BamHI and EcoRV sites, resulting in plasmid pAM2811. The SalI DNA fragment containing PhepA-patS5 from pAM2811 was inserted into the SalI sites of shuttle vectors pAM504 and pAM1956, resulting in plasmids pAM2814 (PhepA-patS5) and pAM2816 (PhepA-patS5-gfp), respectively. In pAM2816, gfp is downstream of patS5 as a transcriptional fusion.

PrbcL-gfp-patS5 was generated by PCR with primers AMO-367 and AMO-617 and pAM1954 as the template to produce a translational fusion between gfp and patS5. The 1.7-kb PCR fragment containing PrbcL-gfp-patS5 was inserted into pAM504 at the SmaI site, resulting in pAM2873.

A fusion of full-length PatS with a C-terminal His6 tag was constructed in two cloning steps. First, PCR primers AMO-569 and AMO-583 were used to produce patS and its upstream sequences with flanking XhoI and SapI sites. The resulting XhoI-SapI fragment was inserted into pAM2600, resulting in pAM2821, such that patS is translationally fused to six histidine codons. Second, an XhoI-ClaI fragment carrying patS-6His from pAM2821 was inserted into shuttle vector pAM2770 (23), resulting in plasmid pAM2826.

A DNA fragment containing ORF all3290 was produced by PCR with primers AMO-659 and AMO-660, digested with NdeI and XmaI, and then inserted into the same sites of pAM2770, resulting in pAM2918, such that all3290 is expressed by the petE promoter.

A DNA fragment containing ORF orf77 was produced by PCR with primers AMO-661 and AMO-662, digested with NdeI and XmaI, and then inserted into the same sites of pAM2770, resulting in pAM2898, such that orf77 is driven by the petE promoter.

For all constructs, the ribosome-binding site and start codon were derived from the promoters used. In all constructs, the inserts were downstream of a transcription terminator on shuttle vectors pAM504, pAM505, and pAM2770 (23, 32, 36). All plasmid constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Plasmid conjugations.

Shuttle plasmids were transferred into E. coli conjugal donor strain AM1359 (36) by electroporation and then transferred into Anabaena strain PCC 7120 by conjugation, using standard methods (8).

Heterocyst inhibition bioassay.

A bioassay, similar to that used in previous work (36), was used in an attempt to detect the presence of heterocyst inhibition activity in the culture supernatant of a strain overexpressing the patS5 minigene. A strain carrying PrbcL-patS5 on pAM2537 was grown in BG-110 medium to an optical density of 0.5 at 750 nm, and then the culture supernatant was collected after centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 7 min at room temperature. The culture supernatant was filtered through a sterile 0.45-μm-pore-size filter. The assay was performed with 100 μl of medium in a 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plate (Thermo LabSystems). Wild-type Anabaena strain PCC 7120 was used as the test strain for the heterocyst inhibition assay. Vegetative-cell filaments were grown in BG-11 medium to an optical density of about 0.3 at 750 nm, harvested by centrifugation, and washed twice with BG-110 medium. Heterocyst development was induced by resuspending the filaments in either 100 μl of BG-110 medium, 100 μl of conditioned culture supernatant, or a 0.5× dilution containing 50 μl of conditioned culture supernatant and 50 μl of BG-110 medium. As a positive control for inhibition, synthetic PatS-5 peptide at 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μM was added to 100 μl of both BG-110 medium and conditioned culture supernatant. The assay plates were incubated under standard conditions for 24 to 48 h, and then samples were scored microscopically for the frequency of heterocysts as described previously (36, 37).

Microscopy and scoring of the heterocyst pattern.

Microscopy, image processing, and scoring of the heterocyst pattern were performed as described previously (36, 37). Three or more samples were scored for each experimental condition. Images of GFP fluorescence with excitation wavelengths of 450 to 490 nm and emission wavelengths of 505 to 531 nm were recorded with a Hamamatsu color charge-coupled device camera.

RESULTS

Suppression of heterocyst development by patS minigenes driven by a copper-inducible promoter.

The patS gene product is thought to function as an intercellular signal produced by differentiating cells and possibly mature heterocysts to inhibit heterocyst formation of neighboring cells by lateral inhibition. Previous work showed that a full-length patS gene, driven by the copper-inducible promoter PpetE, suppressed heterocyst development (36). The PpetE promoter is expressed in vegetative cells (5) and is down-regulated in heterocysts (7). We found that a PpetE-gfp transcriptional reporter showed green fluorescence in both vegetative cells and heterocysts (data not shown), suggesting that the petE promoter is at least partially active in heterocysts. In an effort to determine the localization of the PatS receptor and the characteristics of its interaction with different PatS C-terminal peptides, we expressed patS minigenes from the PpetE promoter and measured the heterocyst inhibition activity of the gene products produced in the cytoplasm of vegetative cells. The patS minigenes contain an ATG translational start codon followed by sequences encoding PatS C-terminal oligopeptides from 4 (GSGR) to 8 (CDERGSGR) amino acids.

Plasmids pAM2525, pAM2424, pAM2526, pAM2529, and pAM2527 (Table 1), containing the PpetE-patS4 to PpetE-patS8 minigenes (Fig. 1A), respectively, were transferred into wild-type Anabaena strain PCC 7120 and the patS null mutant strain AMC451 by conjugation. The resulting strains were induced for heterocyst formation in copper-replete and copper-deficient conditions. Under copper-replete conditions, wild-type Anabaena strain PCC 7120 containing PpetE-patS5, PpetE-patS6, and PpetE-patS8 formed less than 1% heterocysts (Table 3) and a strain containing PpetE-patS7 formed 4% heterocysts. However, PpetE-patS4 failed to inhibit heterocyst formation or alter the heterocyst pattern. Heterocyst formation in the patS null mutant AMC451 was partially inhibited by minigenes PpetE-patS5, PpetE-patS6, PpetE-patS7, and PpetE-patS8, with PpetE-patS5 showing the strongest effect. PpetE-patS4 had no effect on heterocyst development in AMC451. Even under copper-deficient conditions, PpetE-patS5 to PpetE-patS8 were able to partially inhibit heterocyst formation, indicating that some expression from the petE promoter was occurring under our experimental conditions (Table 3). In an attempt to further deplete copper in the cells, we grew filaments in copper-free BG-11 medium for several days before induction, but we obtained similar results (data not shown). Although the minigene results fail to clearly identify the most likely candidate for the genuine PatS signal, it is interesting that patS5 produced the strongest heterocyst inhibition activity. Because the minigene peptide products all contain at least one polar and one charged amino acid and should be confined to the cytoplasm, these data support a cytoplasmic location for the PatS receptor.

TABLE 3.

Suppression of heterocyst formation by PpetE-patS minigenes in wild-type Anabaena strain PCC 7120 and the patS mutant AMC451

| patS minigene (plasmid) | Heterocyst frequencya (%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type

|

AMC451

|

|||

| −Cu2+ | +Cu2+ | −Cu2+ | +Cu2+ | |

| None (pAM504) | 10.9 ± 0.5 | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 18.1 ± 0.2 | 17.2 ± 0.9 |

| PpetE-patS4 (pAM2525) | 11 ± 0.2 | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 16.4 ± 1.7 | 16.9 ± 0.7 |

| PpetE-patS5 (pAM2424) | 4.3 ± 4.9 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 8.3 ± 3.5 | 0.5 ± 0.5 |

| PpetE-patS6 (pAM2526) | 1.8 ± 1.3 | 0 ± 0 | 12 ± 3.6 | 6.7 ± 4.7 |

| PpetE-patS7 (pAM2529) | 8.3 ± 2.9 | 4.0 ± 5.2 | 12 ± 2.5 | 8.2 ± 4.1 |

| PpetE-patS8 (pAM2527) | 4.0 ± 5.2 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 12 ± 2.5 | 2.2 ± 1.8 |

Frequencies measured 48 h after the nitrogen step-down. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Expression of the patS5 minigene in proheterocysts failed to inhibit multiple contiguous heterocysts in a patS null mutant.

To test the hypothesis that PatS-5 is confined to the cytoplasm, we determined if the minigene product could function as a cell-to-cell signal. The patS5 minigene was expressed from a proheterocyst-specific promoter in the patS null mutant AMC451 to determine if it could suppress the multiple-contiguous-heterocyst (Mch) phenotype. Failure to suppress the Mch phenotype would indicate that a cell-to-cell signal was not being produced. The patS5 minigene was used in these experiments because it produced the strongest heterocyst inhibition (Table 3).

Expression of full-length patS and the patS5 minigene from the rbcL promoter in constructs PrbcL-patS17 (pAM1690) (23) and PrbcL-patS5 (pAM2537) completely inhibited heterocyst formation in both the wild-type strain and the patS null mutant AMC451 (Table 4). PrbcL is strongly expressed in vegetative cells (7, 9). In BG-110 liquid medium, cultures of both strains turned yellow within a few days and no heterocyst formation was observed. These results show that PatS-5 pentapeptide can completely block heterocyst differentiation when it is produced in cells before they have become immune to PatS inhibition. PpatS-patS5 (pAM2528) only partially inhibited heterocyst formation in both strains (Table 4), reflecting the weak expression of the patS promoter in vegetative cells (36, 37).

TABLE 4.

Suppression of heterocyst formation by patS5 and patS17 in wild-type Anabaena strain PCC 7120 and the patS mutant AMC451

| patS minigene (plasmid) | Heterocyst frequencya (%)

|

% of Mch in AMC451b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | AMC451 | ||

| None (pAM504) | 12.2 ± 2.0 | 19.9 ± 2.1 | 11.5 |

| PrbcL-patS5 (pAM2537) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| PrbcL-patS17 (pAM1690) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0 |

| PpatS-patS5 (pAM2528) | 6.4 ± 4.4 | 4.0 ± 3.5 | NDc |

| PhepA-patS5 (pAM2814) | 12.1 ± 1.9 | 18.8 ± 2.1 | 11.2 |

| PhepA-patS17 (pAM1715) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 9.8 ± 0.2 | 0 |

| PhepA-patS5-gfp (pAM2816) | 0.7 ± 1.0 | 18.8 ± 1.9 | 12.3 |

Frequencies measured 24 h after the nitrogen step-down. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

The percentage of heterocysts that are multiple constitutive heterocysts (Mch).

ND, not determined.

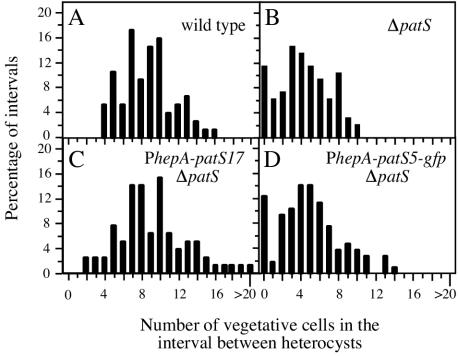

PhepA is expressed in developing proheterocysts and has much lower expression in vegetative cells (14, 33, 39). Consistent with previous results (36), PhepA-patS17 (pAM1715), which contains the full-length patS gene, complemented the patS deletion strain AMC451, suppressed the Mch phenotype, and restored a nearly wild-type heterocyst pattern (Fig. 2; Table 4). This shows that the hepA promoter is apparently turned on strongly only after differentiating cells have become immune to self-inhibition and shows that the wild-type PatS product can function in cell-to-cell signaling to prevent the formation of multiple contiguous heterocysts.

FIG. 2.

PatS-5 does not function as a cell-to-cell signal. Plasmids containing patS17 and patS5 expressed from the proheterocyst-specific promoter PhepA were used to complement the patS deletion strain AMC451. The heterocyst pattern was determined 24 h after nitrogen step-down for the wild type (A), strain AMC451 (B), AMC451 containing pAM1715 (PhepA-patS17) (C), and AMC451 containing pAM2816 (PhepA-patS5-gfp) (D).

Expression of the patS5 minigene in differentiating cells from PhepA-patS5 (pAM2814) did not suppress the Mch phenotype of AMC451 (Table 4). This result is consistent with the pentapeptide failing to function in cell-to-cell signaling when produced in proheterocysts. However, this construct may be producing less PatS heterocyst inhibition activity because it did not suppress heterocysts in the wild type. In an effort to monitor the expression of PhepA-patS5, a promoterless gfp reporter gene was placed downstream of the patS5 minigene such that the gfp gene contained its own start codon and ribosome-binding site. The PhepA-patS5-gfp construct (pAM2816) produced dim GFP fluorescence in differentiating cells, as expected, and had stronger heterocyst inhibition activity in the wild-type background, which reduced the heterocyst frequency to less than 1% (Table 4). The mechanism causing the stronger heterocyst inhibition activity is unknown, but it might be due to increased stability of the mRNA. In the presence of a wild-type copy of patS, both PhepA-patS17 and PhepA-patS5-gfp produced enough PatS heterocyst inhibition activity to overcome the immunity to self-inhibition and blocked heterocyst differentiation.

However, unlike the wild-type PatS produced from PhepA-patS17, the PatS-5 pentapeptide produced from PhepA-patS5-gfp failed to complement the patS deletion strain. AMC451 carrying PhepA-patS5-gfp had short vegetative-cell intervals and formed multiple contiguous heterocysts (Fig. 2; Table 4). These data show that the pentapeptide produced by the patS5 minigene expressed in proheterocysts cannot function in cell-to-cell signaling and therefore is apparently confined to the cytoplasm.

PatS-5 activity is not detectable in conditioned culture medium.

To determine if the patS5 minigene product was either leaking or being transported out of filaments at concentrations sufficient to inhibit heterocyst formation, we tested conditioned culture supernatant from a strain containing PrbcL-patS5 (pAM2537) for heterocyst inhibition activity. The supernatant from a culture of the strain grown in BG-110 medium failed to inhibit heterocyst formation. In a reconstruction experiment to verify that our assay could detect PatS-5 pentapeptide in conditioned medium, we added synthetic PatS-5 to conditioned culture supernatant and BG-110 medium at 0.1, 0.5, and 1 μM. Heterocyst formation was inhibited at each peptide concentration in both media. These results indicate that the patS5 minigene product is not exported or does not leak from filaments at concentrations capable of inhibiting heterocysts and are consistent with the PatS signal interacting with a receptor in the cytoplasm.

RGSGR fusion proteins inhibit heterocyst differentiation.

To further characterize the interaction between the PatS signaling molecule and the PatS receptor, we tested PatS fusion proteins for their ability to inhibit heterocyst formation. A gfp-patS5 translational fusion was constructed and expressed from the PrbcL promoter. The fusion of GFP to the N terminus of PatS-5 should confine the RGSGR motif to the cytoplasm. PrbcL-gfp-patS5 on pAM2873 completely inhibited heterocyst formation after the nitrogen step-down and, as expected, produced strong GFP fluorescence in the cytoplasm of vegetative cells (data not shown).

A six-histidine fusion at the C terminus of PatS produced similar results. A translational fusion was constructed in pAM2826 in which six histidine codons were added to the 3′ end of the full-length patS ORF. When expressed from the native patS promoter, patS-6His completely suppressed heterocyst development. These results show that neither the N-terminal GFP fusion nor the C-terminal His fusion interferes with the ability of the RGSGR motif to interact with its receptor and inhibit heterocyst differentiation. These results also are consistent with the hypothesis that the PatS receptor is located inside the cytoplasm of vegetative cells.

Proteins containing an RGSGR motif inhibit heterocyst differentiation.

We searched the Anabaena strain PCC 7120 genome for ORFs other than patS containing an RGSGR motif to determine if overexpression of any of these ORFs was able to inhibit heterocyst formation. The GeneMark program (4), set to the lowest stringency, was used to identify all possible ORFs in the Anabaena strain PCC 7120 genome (18). These ORF sequences were then searched with a text editor for those containing the RGSGR motif.

Four ORFs containing RGSGR were identified. One was patS itself. Another was hetN, which is known to inhibit heterocyst development when overexpressed (3, 6). However, HetN must have an independent heterocyst inhibition activity, because site-directed mutation of the RGSGR motif in HetN does not alter its heterocyst inhibition activity (24). The third gene encoding a RGSGR motif was all3290, which encodes an ortholog of an N. punctiforme protein annotated as the ATPase component of an ABC-type sugar transport system. The fourth RGSGR-encoding ORF was not documented in the annotated Anabaena strain PCC 7120 genome database (18). This ORF has only 77 codons and is located on the opposite strand from the much larger ORF cyaC (all4963), which encodes an adenylate cyclase (19). CyaC is a complex protein with motifs similar to those of adenylate cyclases, response regulators, and sensor kinases, and a cyaC mutant had much lower levels of cyclic AMP than the wild type did. Thus, it seemed unlikely that this short RGSGR-encoding ORF (termed orf77) is actually expressed; however, we tested both orf77 and all3290 for heterocyst-inhibition activity.

ORFs all3290 and orf77 were cloned into the expression vector pAM2770 downstream of the petE promoter, resulting in pAM2918 and pAM2898, respectively. On BG-110 plates, strains containing these constructs were completely suppressed for heterocyst development. Although we assume that the RGSGR motif is responsible for the inhibition, we cannot exclude the possibility that these proteins inhibit heterocyst differentiation by an unknown mechanism. Note that all3290 and orf77 in the wild-type chromosome normally must not inhibit heterocyst formation, or they would mask the phenotype of patS mutants. From these experiments and those with the patS fusion constructs, we conclude that the PatS receptor is located in the cytoplasm and can interact with the RGSGR motif embedded in different contexts. These conclusions are consistent with the recent data indicating that the cytoplasmic HetR protein may be the PatS receptor (15).

DISCUSSION

patS minigenes PpetE-patS5 to PpetE-patS8, but not PpetE-patS4, on shuttle plasmids were able to inhibit heterocyst formation. However, unlike the full-length patS gene, the patS5 minigene expressed from the heterocyst-specific promoter PhepA did not complement the pattern formation defect of a patS mutant. This result indicates that the PatS-5 pentapeptide produced within differentiating cells by the minigene cannot function in cell-to-cell signaling. Overall, overexpression of a variety of genes encoding a RGSGR motif suppressed heterocyst development, including patS itself, all3290, and orf77 and patS fusion protein genes gfp-patS5 and patS-6His. Taken together, these results strongly support the hypothesis that the PatS receptor is in the cytoplasm of cells and that the RGSGR motif is capable of inhibiting heterocyst differentiation even when embedded in different contexts.

PpetE-patS4 did not suppress heterocyst development in either the wild type or the patS null mutant AMC451. Previous work showed that the synthetic oligopeptide PatS-4 (GSGR) had much less heterocyst inhibition activity than did PatS-5 when added to the growth medium (36). These results show that PatS-4 cannot function as the PatS signal.

When expressed from the copper-inducible petE promoter, patS minigenes from patS5 to patS8 all inhibited heterocyst development. The patS5 minigene appeared to produce the strongest heterocyst inhibition, followed by patS6 and patS8; patS7 showed the weakest inhibition activity in both the wild type and the patS deletion strain AMC451. The basis for the differences in biological activities among the patS minigenes is unknown. Both full-length patS and the patS5 minigene strongly suppressed heterocyst development when expressed in vegetative cells under the control of PrbcL. The results of these minigene experiments are consistent with the possibility that the RGSGR pentapeptide may be the active signal molecule controlling the heterocyst pattern. Our attempts to detect the actual PatS signal molecule(s) by matrix-assisted laser desorption-ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry in wild-type and patS overexpression strains compared to the patS deletion mutant AMC451 have been unsuccessful thus far.

The patS5 minigene product cannot function in cell-to-cell signaling. Unlike full-length patS, expression of the patS5 minigene from the proheterocyst-specific PhepA promoter in pAM2816 failed to complement the patS deletion mutant AMC451 to produce a normal heterocyst pattern. pAM2816, which carries PhepA-patS5 and a downstream gfp ORF, suppressed heterocysts in the wild-type background, which indicates that this construct produces levels of PatS-5 pentapeptide sufficient to inhibit heterocysts. Since synthetic PatS-5 pentapeptide can inhibit heterocysts when added exogenously to filaments, the PatS-5 produced in proheterocysts from a minigene must not be able to get out of the differentiating cells to inhibit the neighboring cells. Because the full-length patS gene functions cell nonautonomously and the patS5 minigene does not, the C-terminal PatS-5 pentapeptide apparently lacks sequences required for cell-to-cell signaling.

The ability of ORF all3290 overexpression to inhibit heterocyst development might be due to only the overexpression of the RGSGR motif, or all3290 might be normally involved in the regulation of heterocyst development. However, an all3290 knockout mutant grew normally and showed normal heterocyst development and pattern formation (data not shown), indicating that it is not normally involved in heterocyst development. Although RNA blot analysis showed that all3290 was expressed in filaments grown in nitrate-containing medium, transcripts were undetectable after nitrogen step-down for 6, 12, and 18 h (data not shown), when its expression might otherwise have inhibited heterocyst differentiation. We conclude that the RGSGR motif in all3290 does not normally regulate heterocyst development but inhibits differentiation only when it is overexpressed.

Because overexpression of a wide variety of RGSGR-encoding genes suppressed heterocyst development, including patS, all3290, orf77, gfp-patS5, patS-6His, and the patS minigenes PpetE-patS5 to PpetE-patS8, the PatS receptor must be able to interact with the RGSGR motif flanked by a variety of amino acid sequences. This suggests that the PatS binding site on the receptor is relatively open and accessible to the various RGSGR-containing polypeptides. It is possible that some of the PatS fusion proteins are degraded such that various smaller peptides containing the RGSGR motif are produced. However, these putative peptides must still interact with the receptor to inhibit the differentiation of heterocysts. Because all of the RGSGR-fusion constructs and the ORFs containing an RGSGR motif strongly inhibit heterocyst differentiation and should be confined to the cytoplasm, the PatS receptor must be located in the cytoplasm of vegetative cells, which is consistent with PatS directly inhibiting HetR function. Together, the PatS inhibitor and the HetR activator could satisfy the primary requirements for regulation of the heterocyst pattern by lateral inhibition, as recently proposed by Huang et al. (15). However, other, more complex models of the regulation are possible, and the true mechanism cannot be fully understood until the actual molecule(s) that carries the inhibitory signal between cells has been identified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mohammad G. Ghalichi for determining the heterocyst pattern in strains carrying PpetE driving patS minigene fusions and strains carrying PrbcL-patS5, PhepA-patS5, and PpatS-patS5.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM36890 from the National Institutes of Health and by Texas Advanced Research Program grant 010366-0010-1999.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacon Schneider, K., T. M. Palmer, and A. D. Grossman. 2002. Characterization of comQ and comX, two genes required for production of ComX pheromone in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:410-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, T. A., Y. Cai, and C. P. Wolk. 1993. Spatial expression and autoregulation of hetR, a gene involved in the control of heterocyst development in Anabaena. Mol. Microbiol. 9:77-84. (Erratum, 10:1153, 1993.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black, T. A., and C. P. Wolk. 1994. Analysis of a Het- mutation in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 implicates a secondary metabolite in the regulation of heterocyst spacing. J. Bacteriol. 176:2282-2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borodovsky, M., and J. McIninch. 1993. GeneMark: parallel gene recognition for both DNA strands. Comput. Chem. 17:123-133. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buikema, W. J., and R. Haselkorn. 2001. Expression of the Anabaena hetR gene from a copper-regulated promoter leads to heterocyst differentiation under repressing conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:2729-2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callahan, S. M., and W. J. Buikema. 2001. The role of HetN in maintenance of the heterocyst pattern in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Mol. Microbiol. 40:941-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehira, S., M. Ohmori, and N. Sato. 2003. Genome-wide expression analysis of the responses to nitrogen deprivation in the heterocyst-forming cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. DNA Res. 10:97-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elhai, J., A. Vepritskiy, A. M. Muro-Pastor, E. Flores, and C. P. Wolk. 1997. Reduction of conjugal transfer efficiency by three restriction activities of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 179:1998-2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elhai, J., and C. P. Wolk. 1990. Developmental regulation and spatial pattern of expression of the structural genes for nitrogenase in the cyanobacterium Anabaena. EMBO J. 9:3379-3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golden, J. W., L. L. Whorff, and D. R. Wiest. 1991. Independent regulation of nifHDK operon transcription and DNA rearrangement during heterocyst differentiation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 173:7098-7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golden, J. W., and H. S. Yoon. 1998. Heterocyst formation in Anabaena. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:623-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golden, J. W., and H. S. Yoon. 2003. Heterocyst development in Anabaena. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:557-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossman, A. D. 1995. Genetic networks controlling the initiation of sporulation and the development of genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 29:477-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holland, D., and C. P. Wolk. 1990. Identification and characterization of hetA, a gene that acts early in the process of morphological differentiation of heterocysts. J. Bacteriol. 172:3131-3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang, X., Y. Dong, and J. Zhao. 2004. HetR homodimer is a DNA-binding protein required for heterocyst differentiation, and the DNA-binding activity is inhibited by PatS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4848-4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa, S., L. Core, and M. Perego. 2002. Biochemical characterization of aspartyl phosphate phosphatase interaction with a phosphorylated response regulator and its inhibition by a pentapeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 277:20483-20489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaiser, D. 2001. Building a multicellular organism. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:103-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko, T., Y. Nakamura, C. P. Wolk, T. Kuritz, S. Sasamoto, A. Watanabe, M. Iriguchi, A. Ishikawa, K. Kawashima, T. Kimura, Y. Kishida, M. Kohara, M. Matsumoto, A. Matsuno, A. Muraki, N. Nakazaki, S. Shimpo, M. Sugimoto, M. Takazawa, M. Yamada, M. Yasuda, and S. Tabata. 2001. Complete genomic sequence of the filamentous nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. DNA Res. 8:205-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katayama, M., and M. Ohmori. 1997. Isolation and characterization of multiple adenylate cyclase genes from the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 179:3588-3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroos, L., and J. R. Maddock. 2003. Prokaryotic development: emerging insights. J. Bacteriol. 185:1128-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazazzera, B. A., I. G. Kurtser, R. S. McQuade, and A. D. Grossman. 1999. An autoregulatory circuit affecting peptide signaling in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:5193-5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazazzera, B. A., J. M. Solomon, and A. D. Grossman. 1997. An exported peptide functions intracellularly to contribute to cell density signaling in B. subtilis. Cell 89:917-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, M. H., M. Scherer, S. Rigali, and J. W. Golden. 2003. PlmA, a new member of the GntR family, has plasmid maintenance functions in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J. Bacteriol. 185:4315-4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, B., X. Huang, and J. Zhao. 2002. Expression of hetN during heterocyst differentiation and its inhibition of hetR up-regulation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. FEBS Lett. 517:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meeks, J. C., and J. Elhai. 2002. Regulation of cellular differentiation in filamentous cyanobacteria in free-living and plant-associated symbiotic growth states. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:94-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meeks, J. C., J. Elhai, T. Thiel, M. Potts, F. Larimer, J. Lamerdin, P. Predki, and R. Atlas. 2001. An overview of the genome of Nostoc punctiforme, a multicellular, symbiotic cyanobacterium. Photosynth. Res. 70:85-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perego, M. 1997. A peptide export-import control circuit modulating bacterial development regulates protein phosphatases of the phosphorelay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8612-8617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perego, M. 1998. Kinase-phosphatase competition regulates Bacillus subtilis development. Trends Microbiol. 6:366-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perego, M., C. F. Higgins, S. R. Pearce, M. P. Gallagher, and J. A. Hoch. 1991. The oligopeptide transport system of Bacillus subtilis plays a role in the initiation of sporulation. Mol. Microbiol. 5:173-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon, J. M., R. Magnuson, A. Srivastava, and A. D. Grossman. 1995. Convergent sensing pathways mediate response to two extracellular competence factors in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 9:547-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stephenson, S., C. Mueller, M. Jiang, and M. Perego. 2003. Molecular analysis of Phr peptide processing in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 185:4861-4871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei, T. F., T. S. Ramasubramanian, and J. W. Golden. 1994. Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 ntcA gene required for growth on nitrate and heterocyst development. J. Bacteriol. 176:4473-4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolk, C. P., J. Elhai, T. Kuritz, and D. Holland. 1993. Amplified expression of a transcriptional pattern formed during development of Anabaena. Mol. Microbiol. 7:441-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolk, C. P., A. Ernst, and J. Elhai. 1994. Heterocyst metabolism and development, p. 769-823. In D. A. Bryant (ed.), The molecular biology of cyanobacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 35.Wolk, C. P., and M. P. Quine. 1975. Formation of one-dimensional patterns by stochastic processes and by filamentous blue-green algae. Dev. Biol. 46:370-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoon, H. S., and J. W. Golden. 1998. Heterocyst pattern formation controlled by a diffusible peptide. Science 282:935-938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoon, H. S., and J. W. Golden. 2001. PatS and products of nitrogen fixation control heterocyst pattern. J. Bacteriol. 183:2605-2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou, R., X. Wei, N. Jiang, H. Li, Y. Dong, K. L. Hsi, and J. Zhao. 1998. Evidence that HetR protein is an unusual serine-type protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:4959-4963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu, J., R. Kong, and C. P. Wolk. 1998. Regulation of hepA of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 by elements 5′ from the gene and by hepK. J. Bacteriol. 180:4233-4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]