Abstract

Recent evidence suggests that the airway mucus gel layer may be impermeable to the viral and synthetic gene vectors used in past inhaled gene therapy clinical trials for diseases like cystic fibrosis. These findings support the logic that inhaled gene vectors that are incapable of penetrating the mucus barrier are unlikely to provide meaningful benefit to patients. In this review, we discuss the biochemical and biophysical features of mucus that contribute its barrier function, and how these barrier properties may be reinforced in patients with lung disease. We next review biophysical techniques used to assess the potential ability of gene vectors to penetrate airway mucus. Finally, we provide new data suggesting that fresh human airway mucus should be used to test the penetration rates of gene vectors. The physiological barrier properties of spontaneously expectorated CF sputum remained intact up to 24 hours after collection when refrigerated at 4 °C. Conversely, the barrier properties were significantly altered after freezing and thawing of sputum samples. Gene vectors capable of overcoming the airway mucus barrier hold promise as a means to provide the widespread gene transfer throughout the airway epithelium required to achieve meaningful patient outcomes in inhaled gene therapy clinical trials.

Introduction

Pulmonary disease affects millions of people worldwide, including those with cystic fibrosis (CF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), and asthma. Inhalation of DNA- or RNA-based therapeutics provides direct access to the organ of interest in these patients. Nevertheless, each of the more than 25 gene therapy clinical trials adopting this administration route have failed to reach their primary therapeutic endpoints.1 The airway mucus gel layer has been shown to be a key barrier to successful inhaled gene therapy.2,3,4,5 The mucus layer traps inhaled particulates and facilitates their removal from the airways via mucociliary clearance (MCC) and other clearance mechanisms.5,6,7 Likewise, many viral and nonviral gene vectors used in past inhaled gene therapy trials have recently been shown to be adhesive to human airway mucus8,9,10,11 and, thus, are likely incapable of efficiently penetrating the mucus gel layer to reach the targeted underlying epithelial cells prior to clearance.

Exclusion of inhaled gene vectors from the underlying airway epithelium by the mucus gel layer is a major concern that may help explain the disappointing clinical outcomes in inhaled gene therapy trials to date. We have proposed that inhaled gene vectors to be tested in patients in the future should, at a minimum, be limited to those shown capable of rapidly penetrating human airway mucus ex vivo. This review is focused on airway mucus as a critical obstacle to effective inhaled gene therapy. We first review the biochemical and biophysical properties of mucus in the airways and how they are altered in obstructive lung diseases in a manner that further enhances the barrier properties. Experimental methods to assess the transport of inhaled gene vectors within airway mucus are then reviewed, including analysis of the drawbacks and advantages of each approach. Finally, we discuss the importance of using mucus that has barrier properties similar to what is found in mucus freshly-obtained from the human airways, as well as best practices for handling airway mucus samples to ensure their physiological properties are preserved.

Mucus Barrier Properties

Mucus in individuals without lung disease

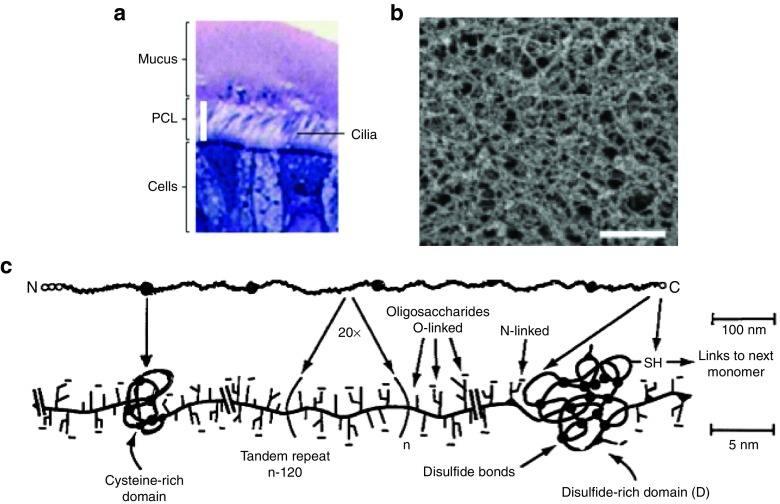

Airway surface liquid is composed of the mucus gel layer and the pericilary layer (PCL) (Figure 1a).12 Airway surface liquid height has been estimated to range from 10–20 µm in thickness based on measurements from in vitro primary human bronchial epithelial cultures and ex vivo fragments of human tracheas.12,13,14,15,16 The mucus gel lining the airways acts as a protective barrier for the underlying epithelium against inhaled particulates and pathogens.5,17,18 Airway mucus is a viscoelastic gel19,20 with a near neutral pH,21 and possesses a porous structure as shown by electron microscopy (Figure 1b).9,11,22,23 Mucins are continuously secreted into the airways where they form a gel layer that is continuously removed from the lungs to the throat via MCC, or is occasionally coughed out. Mucus cleared from the lungs via MCC is swallowed and its contents are sterilized in the stomach. MCC of the mucus gel is driven by high frequency coordinated beating of hair-like cilia that are tethered to the apical surface of ciliary airway epithelial cells and span the entire PCL.7,24 The mucus gel layer lining the human airways has been estimated to be replenished at a rate of 3–5 mm/min,25,26,27 and the clearance of inhaled foreign matter trapped within the mucus gel occurs in 15 minutes to 2 hours after inhalation.28 It should be noted that the clearance rate depends on several factors, including particle deposition pattern after inhalation (i.e., deposited in small versus large airways) and disease status (i.e., healthy individuals versus those with CF, COPD, and asthma).28 Consequently, inhaled gene vectors that do not rapidly penetrate the mucus gel also do not efficiently reach the underlying airway epithelium, and instead are cleared from the lungs and swallowed. We note that the PCL has recently been identified as another potentially critical barrier to inhaled gene therapy,12,29 but this has been described in a recent review.30

Figure 1.

Mucus in the airways of humans without lung disease. (a) Histological staining of human primary bronchial epithelial cell cultures showing the airway surface liquid (ASL) composed of the periciliary layer (PCL) and the airway mucus gel layer (mucus). Reproduced with permission from.12 (b) Scanning electron micrograph of human airway mucus collected from an individual without lung disease (Scale bar = 500 nm). Reproduced with permission from.23 (c) Schematic of mucin subunits connected via disulfide bonds between cysteine domains to form the airway mucus gel. Reproduced with permission from.5

The gel component of airway mucus secretions are primarily composed of mucin fibers, which are O-linked glycoproteins, a high proportion of which possesses a “bottle-brush” conformation with oligosaccharide side chains attached to a polypeptide backbone (Figure 1c).5,17,18 The glycosylated regions of mucin fibers, which carry a net negative charge, are separated by periodic hydrophobic protein domains (Figure 1c).5,17,18 Glycosylated regions make up ~70–80% of the total mucin mass and their oligosaccharide chains are usually terminated by sulfate, sialic acid or fucose.31 Sialylated and/or sulfated oligosaccharides are anionic and thus contribute to charge and hydrophilic barrier properties, while fucose-terminated oligosaccharides contribute to mucus hydrophobicity.32 The polypeptide backbone of mucins carries both positively and negatively charged amino acid sequences,33 which may aid in mucus trapping of charged particulates. There are at least 20 identified types of mucins, each with different biophysical properties, including different glycosylation patterns and molecular weights (MW).17,34 Several mucin types are secreted in the airways, but the airway mucus gel layer consists primarily of high MW (2–200 MDa) polymeric mucins.18,35,36 Airway mucin biopolymers are packaged within secretory cells via intramucin disulfide bonds between terminal cysteine domains prior to secretion (Figure 1c).37 Mucin biopolymers are dehydrated and further condensed in intracellular secretory granules by a high intragranular calcium ion concentration and acidic pH.37 Upon exocytosis from secretory cells, bicarbonate present in the airway lumen sequesters the calcium ions, leading to rapid expansion of mucin biopolymers.38 The expanding mucins combine with various proteins, lipids, and other molecules to form the airway mucus gel.

The most abundant gel-forming mucin types in the airway are MUC5AC and MUC5B.17,35,39,40 MUC5B is primarily excreted from submucosal glands, while a small fraction is secreted by epithelial goblet cells.41 On the other hand, MUC5AC is exclusively released from airway epithelial goblet cells.41 The amounts of MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA transcripts produced in airway epithelial cells are roughly equal in normal human airways.42 However, given the differences in the types of mucins primarily secreted by goblet cells and submucosal glands, the distribution of mucin subtypes along the airways may vary. MUC5AC has a lower mass to unit length ratio than MUC5B, suggesting that it possesses shorter oligosaccharide chains.18 Further, MUC5B may be present in human airway secretions in both low-charge and high-charge glycoforms.17,34 Given their differences, MUC5AC- and MUC5B-rich regions within mucus gels may possess distinct barrier functions.

Numerous soluble biomacromolecules, including globular proteins, antibodies and lipids, are present in the fluid that fills the pores of the mucus mesh, which we refer to as interstitial fluid. As a result, the viscosity of the interstitial fluid is ~ twofold to threefold greater than the viscosity of water.23 Viscous drag imposed by the interstitial fluid is unlikely to contribute significantly to barrier function since mucus gel at low shear rates has a viscosity that has orders of higher magnitude.43 The primary diffusion barrier to inhaled particulates is thought to arise from a combination of the mucus mesh structure, which excludes particles that are too large to pass through, and the adhesiveness of mucus that acts as a “sticky net” to trap particulate.4 The two primary mechanisms by which inhaled micro- and nanoscopic entities are trapped in airway mucus, namely steric and adhesive trapping, are discussed in the Section “Trapping mechanisms”. Contributions of soluble macromolecules, including antibodies, to airway mucus barrier function are also discussed in the Section “Trapping mechanisms”.

Mucus in individuals with lung disease

The physicochemical properties of airway mucus are significantly altered in the lungs of individuals with obstructive lung diseases, including CF, COPD, and asthma.6 CF is a monogenic disorder caused by a mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR), a protein that is important to regulation of airway hydration.44,45 CFTR dysfunction initiates a cascade of events that include reduced MCC, airway obstruction, persistent infection, and chronic inflammation.46,47,48,49 COPD is triggered by continous exposure to environmental toxins, primarily cigarette smoke, that cause chronic inflammation, goblet cell metaplasia, mucus accumulation, and airway obstruction.50,51,52 Asthma is characterized by a hyperinflammatory response to allergen exposure that leads to immune cell infiltration and mucus hypersecretion in the airways.53,54,55 Studies have also demonstrated that viscoelasticity of airway mucus secretions is elevated in individuals at high risk of, or diagnosed with, lung cancer.56,57

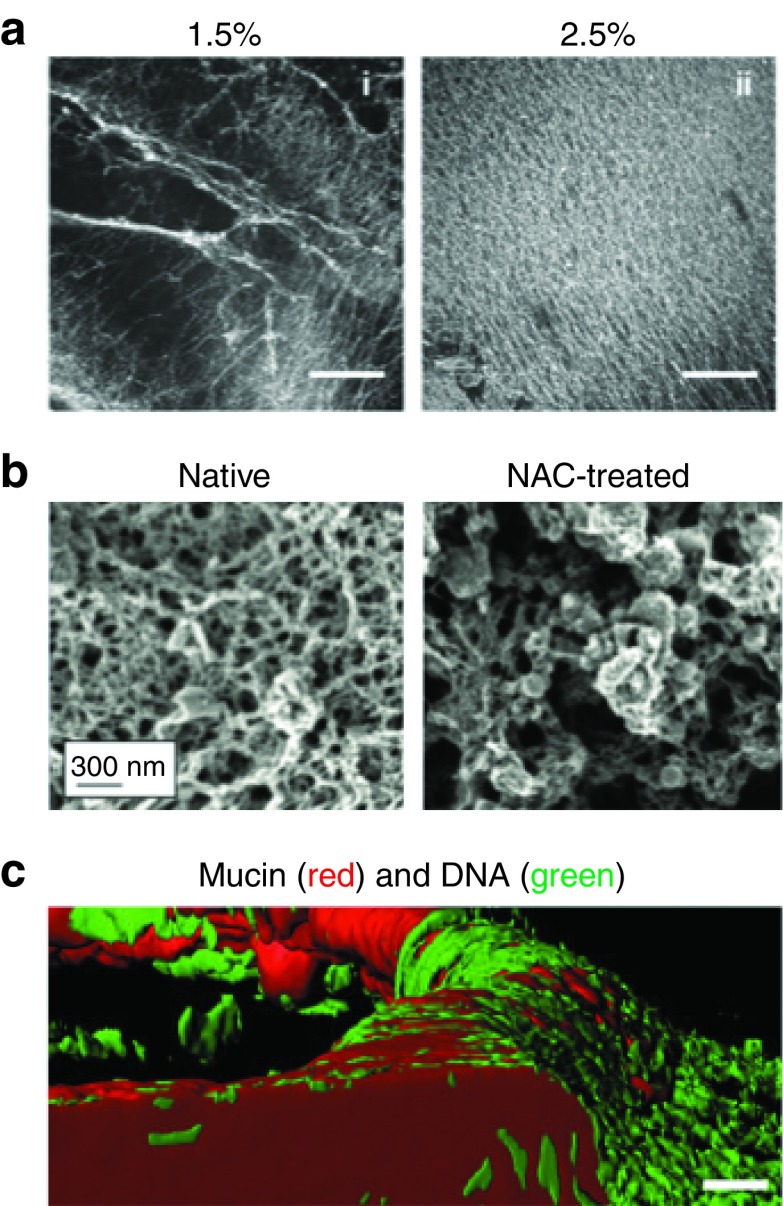

Airway mucus secretions produced by individuals with CF, COPD, and asthma have higher viscosity and elasticity (i.e., higher viscoelasticity) than mucus from individuals without lung disease.58,59 Build-up of mucus in the airways leads to obstruction and contributes to impaired lung function, particularly in CF and COPD.6 Airway dehydration occurs in both CF and COPD, leading to reduced airway surface liquid height and a hyperconcentrated airway mucus gel.24 Chronic and/or acute airway inflammation, often observed in CF, COPD, and asthma, may trigger mucin hypersecretion, thereby further increasing the overall mucin content in the airways (Figure 2a).53,60,61,62,63 Oxidative stress due to inflammation also increases inter and intramucin fiber disulfide bond density in mucus from individuals with CF.64 Cleavage of intra- and intermolecular disulfide bonds in mucin polymers using N-acetyl cysteine significantly increases the pore size of CF mucus (Figure 2b),65 underscoring the importance of the bonds to mucus microstructure. Enhanced disulfide bond formation is also likely to occur in COPD and asthma since these diseases are also characterized by high levels of oxidative stress.66,67 In CF and potentially COPD lung airways, impaired CFTR-mediated bicarbonate secretion leads to inefficient displacement of calcium ions from secreted mucin.68, 69, 70 As a result, mucins remain in a condensed form and may contribute to a tighter mesh structure compared to mucus from healthy individuals. Although it has yet to be tested, differential expression of mucin subtypes in CF, COPD, and asthma may also impact the barrier properties of the airway mucus gel layer. Furthermore, the respective levels of mucin glycoforms secreted in response to infection and inflammation may vary dependent upon the clinical status of individual patients.32,68

Figure 2.

Mucus in the airways of humans with obstructive lung diseases. (a) Confocal microscopy images of human bronchial epithelial-derived mucus hydrogels at 1.5 and 2.5% total mucus solid content (Scale bars = 500 µm). Mucins were fluorescently labeled with rhodamine-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin. Reproduced with permission from.63 (b) Scanning electron micrographs of cystic fibrosis (CF) airway mucus before (native) and after reduction of disulfide cross-links between mucin fibers by N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) treatment (Scale bar = 300 nm). Reproduced with permission from.65 (c) Confocal microscopy images of CF airway mucus composed of mucin (red; anti-MUC5AC/MUC5B) and DNA (green; YO-PRO I Iodide) (Scale bar = 20 µm). Reproduced with permission from.64

In addition to altered mucus properties, airway secretions in people with obstructive lung disease often contain abnormal levels of other large biomacromolecules due to infection and inflammation. Inflammatory responses initiated by infection lead to build-up of cellular debris, such as chromosomal DNA and actin microfilaments, particularly in CF.18,49 DNA found in CF mucus originates from the lysates of neutrophils rather than from bacteria found in chronically infected CF airways.69 Increased DNA levels may enhance the mucus barrier by elevating mucus adhesivity (due to increased negative charge density) and decreasing mucus mesh size (due to entanglement within the mucus mesh network) (Figure 2c).64 Recently, we have confirmed that increased DNA levels in CF mucus correlates with reduced mucus mesh size.71 Recombinant human DNase (Pulmozyme) is a commonly used mucolytic compound that reduces CF mucus viscoelasticity upon inhalation by cleaving DNA oligomer chains.70 Increased levels of actin may also enhance mucus barrier properties, as gelsolin treatment, which depolymerizes actin, greatly reduces the viscoelastic properties of CF airway secretions.72 However, the effects of actin levels on the diffusion of inhaled gene vectors within airway mucus have not been fully elucidated. Increased levels of biomacromolecules and other soluble factors, including proinflammatory cytokines, in the airways of patients with obstructive lung diseases can increase the viscosity of the interstitial fluid in the mucus mesh pores. However, the viscosity of interstitial fluid in CF airway mucus is only fourfold to sixfold greater than the viscosity of water73 and, thus, is unlikely to add significantly to the resistance of the penetration of gene vectors through the mucus gel layer.

Chronic bacterial infections commonly found in the lungs of individuals with CF are established through bacterial microcolonies and/or biofilms embedded within airway mucus secretions.71, 74, 75 The diffusion of polystyrene (PS) nanoparticles (NP) and antibiotic-loaded liposomes is greatly hindered within the extracellular matrix of biofilms produced by bacteria commonly found in the lungs of CF patients, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkhedia cepacia complex.76,77,78 As such, bacterial biofilms may represent an additional extracellular barrier component unique to CF airway mucus that must be overcome by inhaled gene vectors.

Trapping mechanisms

Adhesive trapping. Inhaled gene vectors can become trapped in the airway mucus gel layer via noncovalent adhesive interactions, including electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, depending on their surface chemistry (i.e., adhesive trapping). As mentioned previously, the polypeptide backbone of mucin fibers has both negatively and positively charged amino acids at physiological pH.33 However, it is unclear whether the charged groups on the mucin backbone are accessible to inhaled gene vectors due to the dense, negatively-charged glycan coating on mucin fibers. Thus, the negatively-charged glycosolated domains likely pose a significant hindrance to the penetration of positively-charged particulates. As discussed earlier, mucus in individuals with obstructive lung diseases may also contain abnormal levels of DNA and actin, which may also contribute to adhesive trapping of inhaled gene vectors.18,49

Most nonviral gene vectors are formulated with positively-charged carrier materials, including cationic polymers and lipids, that condense nucleic acids into NP with net positively-charged surfaces.79,80,81,82 Sanders et al., showed the diffusion of cationic 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammoniumpropane (DOTAP) lipoplexes was strongly hindered in CF mucus.79 This effect was also observed for some polymer-based gene delivery systems, including those made using polyethylenimine,80 polyamidoamine dendrimer,81 and poly-β-amino ester,82 each of which also carry positively-charged surfaces (>20 mV ζ-potential). In contrast, when the surface charge of NP made using these polymers was shielded by dense coatings with hydrophilic, neutrally-charged polyethylene glycol (PEG), the diffusion rate of each particle type in CF airway mucus was greatly enhanced.80,81,82 Dense PEGylation of these cationic polymer-based gene vectors also greatly improved the following after inhalation into the lungs of mice: (i) gene vector distribution uniformity within the airways, thereby allowing access of gene vectors to a much higher percentage of the underlying epithelium, (ii) gene vector retention within the airways owing to the deep penetration of the particles through the mucus gel layer and into the PCL, and (iii) transgene expression.80,82 These findings underscore the importance of rapid penetration of the airway mucus barrier to achieve high levels of airway gene transfer in vivo.

As previously described, mucin fibers possess periodic hydrophobic domains that can trap inhaled particulates via multivalent hydrophobic interactions. For example, hydrophobic PS NP with near-neutral surface charge (−5 mV) were immobilized in CF mucus, whereas similarly-sized PS NP with dense PEG coatings (PS-PEG NP) freely diffused in the same mucus samples.83 The diffusion of PS NP possessing highly negative surface charge (≈−50 mV) was also greatly hindered in airway mucus collected from people without lung disease23 and with CF.22,65,73 Trapping of strongly negatively-charged PS NP in mucus most likely occurs through adhesive interactions of hydrophobic patches on the PS NP with hydrophobic domains of mucins, since PS NP interactions with the negatively-charged glycosolated regions of mucins are repulsive. Likewise, hydrophobic trapping can occur with inhaled gene vectors formulated with materials with hydrophobic properties, including, but not limited to, lipids and polyesters such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid).

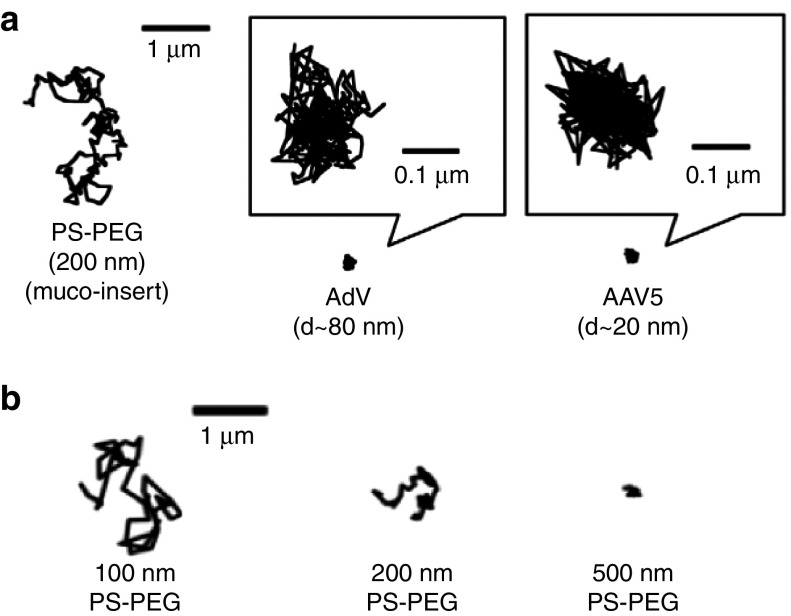

Specific adhesive interactions between gene vectors and mucus in the gel layer may also reduce gene vector penetration, distribution uniformity, and transfection efficiency. For example, proteins on many viruses bind specific sugars on cell surfaces in order to enter the cell, but soluble mucins found in abundance in the mucus gel layer may possess the same sugars. The result is virus trapping in the gel layer and, thus, rapid removal from the lung airways by MCC. Adenovirus serotype 5 and adeno-associated virus (AAV) serotype 1, 2, and 5 all strongly adhere to the CF mucus gel (Figure 3a).10,11 Adenovirus5 binds to heparan sulfate,84,85 which is highly prevalent on airway mucins in the gel layer. AAV of various serotypes bind to cell-surface associated glycans, such as heparan sulfate and/or α 2,3/2,6-linked sialic acids, to infect host cells.86,87,88 However, it should be noted that sialic acids are largely O-linked on airway mucins, whereas AAV1 and AAV5 preferentially bind to N-linked sialic acid glycoforms.86,88 Schuster et al., recently demonstrated that AAV2 adhesion to CF mucus may be partially mediated by specific binding to heparan sulfate on airway mucins.11 This effect was demonstrated using a mutated AAV2 wherein specific binding to heparan sulfate was abolished, leading to a twofold increase in transport in CF mucus compared with wild-type AAV2.11 Others have shown that the influenza virus is immobilized in airway mucus through adhesive interactions of the virus with sialic acid on mucins found in the gel layer, as influenza requires the same specific binding to sialic acid on cell-surface glycans to mediate epithelial cell entry.89 The influenza envelope contains a sialic-acid cleaving enzyme, neuraminidase, which was shown to facilitate its passage through the mucus gel layer.89

Figure 3.

Adhesive and steric trapping of nanoparticles and gene vectors in airway mucus. (a) Representative 20-second trajectories of 200 nm nonmucoadhesive, PEG-coated polystyrene nanoparticles (PS-PEG NP), adenovirus (AdV), and adeno-associated virus serotype 5 (AAV5) in cystic fibrosis (CF) airway mucus, as captured using multiple particle tracking (MPT). Reproduced with permission from.10 (b) Representative 3-second trajectories of 100, 200, and 500 nm PS-PEG NP in human airway mucus from individuals without lung disease, as captured using MPT. Reproduced with permission from.23

Neutralizing antibodies against inhaled gene vectors can also impair penetration through the airway mucus gel layer. Gene vectors coated with a sufficient number of antibodies are subject to multivalent adhesive trapping in mucus since the Fc region of antibodies binds, albeit with low affinity, to mucus.90 However, multiple low-affinity bonds are sufficient to trap a virus, as has been shown in a study where mice were protected against Herpes simplex virus infection via antibody-mediated virus adhesion to cervicovaginal mucus.91 A significant fraction of the CF population harbor active antibodies against AAV2 (~30%) and Adenovirus (~50%),92 which likely leads to antibody-mediated trapping of these viruses in airway mucus. Neutralizing antibodies against other AAV serotypes, including AAV1, 5, 6, 7, and 8, have also been found in the airways of individuals without lung disease and with CF.93,94 Neutralizing antibodies are also produced by inhalation of viral vectors in people who do not have a history of prior exposure.1 Given the extensive use of PEG in pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and everyday household products, anti-PEG antibodies are widely present in humans.95 However, it is unlikely that anti-PEG antibodies are present in sufficient quantities in human mucosal secretions to prevent penetration of PEG-coated gene vectors.

Steric (physical) trapping. Pores within airway mucus gels obtained from humans without lung disease were estimated, using electron microscopy, to have sizes ranging from 100–500 nm.23 Pore size in airway mucus gels from people with CF has been estimated to range from 100–400 nm using electron microscopy,9,11,22 and 160–1440 nm using atomic force microscopy.96 However, sample processing steps required for these techniques, including fixation and dehydration, may introduce artifacts that limit the accurate assessment of the native microstructure of airway mucus.5

Recently, the size of pores within fresh, undiluted, and unperturbed airway mucus gels was assessed using a method based on the transport rates of nonmucoadhesive PS-PEG NP within the mucus gel.43,97 In this method, the degree of hindrance in transport rates of PS-PEG NP of a given diameter can be related to the approximate mucus pore size. Note that particles that adhere to mucus cannot be used in the same way in this method, since their transport behavior is not solely governed by steric obstruction from the mucus mesh. In one study, PS-PEG NP as large as 200 nm were shown to efficiently penetrate CF airway mucus, whereas the transport of 500 nm PS-PEG NP was strongly hindered by steric obstruction.83 The average mucus mesh size was estimated to range between 100–200 nm.83 Significant patient-to-patient variation in mucus mesh size was observed in CF patients in another study, with some samples possessing average pore size <100 nm.11 Size dependent PS-PEG NP transport was also observed in airway mucus from individuals without lung disease (Figure 3b).23 As a result, inhaled gene vectors with sizes significantly above 100 nm are unlikely to efficiently penetrate the mucus gel layer in people with CF due to steric trapping. A recent study concluded that 200 nm PS NP, deposited by aerosol onto a layer of porcine airway mucus, were unable to penetrate into the mucus gel over an hour time period. In contrast, 50–60% of the same NP were diffusive when mechanically mixed into porcine airway mucus.98 This finding suggests that the mucus gel layer may possess smaller pores at the air-mucus interface compared with deeper within the mucus layer.

Increasing mucin content, as is commonly observed in mucus gels from individuals with CF, COPD, and asthma, was shown to produce smaller mucus mesh pore size in a study that assessed particle transport rates in purified human mucin-based hydrogels (Figure 2a).99 As discussed earlier, enhanced mucin cross-linking found in these obstructive lung diseases64 is also likely to decrease mucus mesh pore size. We have recently shown that increased disulfide cross-linking reduces the mucus pore size.71 Furthermore, the treatment of CF mucus with a mucolytic that disrupts mucus cross-linking, N-acetyl cysteine, increased mucus mesh pore size (Figure 2b) and increased the diffusion rate of muco-inert PS-PEG NP.65 Increased DNA content may further tighten the mucus mesh by entangling with mucin fibers (Figure 2c).64 Taken together, these findings suggest airway mucus produced in individuals with obstructive lung diseases will possess smaller mesh pore sizes. However, previous studies of normal and CF mucus used different sample collection methods, making direct comparisons difficult.

The pore size of airway mucus can also have an impact on adhesive interactions of gene vectors with the mucus mesh. It has been reported that N-acetyl cysteine-mediated enlargement of CF mucus mesh spacings, from 50–300 nm to 50–1,300 nm,9 significantly increased the transport of mucoadhesive AAV1 through CF mucus.11 Given the markedly smaller size of AAV1 (~20 nm in diameter) compared with the average mucus mesh size, it is unlikely that decreased physical obstruction to AAV1 transport is responsible for this phenomenon. Instead, the probability of multivalent adhesive interactions between AAV capsid surfaces and the mucus network is expected to reduce when the relative size of the mesh pores compared with gene vectors is increased.

Methods to Assess Mucus Barrier Properties

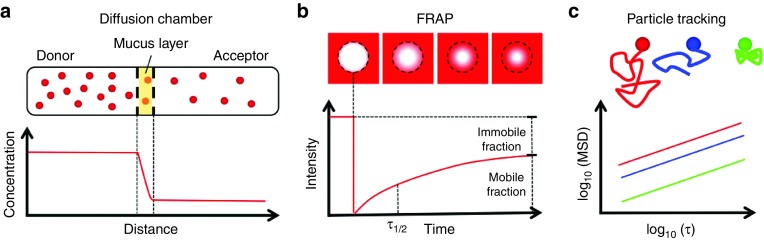

Diffusion chamber

Early investigations of natural compounds (e.g., small molecule, protein) and synthetic NP (e.g., PS, nonviral gene vectors) diffusion in mucus gels most often used diffusion chambers.22,79,100,101,102 In diffusion chamber measurements, mucus is placed between a donor compartment containing the nanoscale object of interest and an acceptor compartment containing a buffer solution. The object diffuses from the donor compartment into the acceptor compartment due to the concentration gradient. The diffusion coefficient of the specific object within mucus is determined based on its concentration profile at steady state (Figure 4a).103 The length and time scales probed with this method are adjusted by changing the distance between donor and acceptor compartments.103

Figure 4.

Biophysical techniques used to assess the barrier properties of airway mucus. (a) Schematic of a diffusion chamber experiment showing nanoparticle (NP) diffusion from the donor compartment, across a mucus layer, and into the acceptor compartment. NP concentrations in the donor and acceptor compartments are measured to assess the percentage of gene vectors that penetrate a mucus layer with a designated thickness. (b) Schematic of fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) experiments showing recovery of fluorescence into a rapidly photo-bleached region due to the diffusion of unbleached gene vectors through mucus. The time to 50% fluorescence recovery (τ1/2) in the bleached region is measured to assess gene vector diffusion rate. The mobile and immobile fraction is determined based on the fraction of fluorescence recovery compared with the prebleached fluorescence intensity. (c) Schematic of particle tracking experiments showing NP trajectories based on their tracked motion within mucus. Using these trajectories, the mean squared displacement (MSD) at designated timescale (τ) is determined for up to thousands of individual gene vectors.

Using this method, the diffusion of PS NP possessing highly negatively charged (≈−50 mV) surfaces22 was assessed. The percentages of 124, 270, and 560 nm PS NP capable of diffusing across a 220 µm thick CF mucus layer within 150 minutes were 0.24 ± 0.08, 0.022 ± 0.008, and 0.0017 ± 0.0009%, respectively.22 The trend of decreasing NP penetration was also observed in a COPD mucus sample.22 We should also note these mucus samples were collected by spontaneous expectoration from patients, frozen at −20ºC and thawed before experimentation. The percentages of these PS NP expected to diffuse across a 220 µm thick layer of pure water (or buffer) were only 0.32% (124 nm NP), 0.15% (270 nm NP) and 0.071% (560 nm NP), as calculated using Fick's first law of diffusion.22 These measurements were among the first demonstrations that NP diffusion rates through airway mucus are slowed as compared with their predicted diffusion rates in water, suggesting that adhesive and steric NP-mucus interactions can affect their transport.

The same group later used this method to show that ~0.05% of DOTAP lipoplexes, with an average diameter 280 nm and zeta potential +47 mV, penetrated a 220 µm thick CF mucus layer. This amounted to a roughly 2.5-fold greater amount of lipoplexes reaching the acceptor compartment compared with 270 nm PS NP.79 The authors suggested the difference may have arised from the broad size distribution of lipoplexes with a greater percentage of smaller lipoplexes reaching the acceptor compartment but, this hypothesis was not confirmed by measuring the size of lipoplexes that penetrated the mucus barrier. It was also shown in this same study that these lipoplexes were unstable in dilute solutions of CF mucus components due to interactions with negatively-charged biopolymers such as mucin and DNA.79

The diffusion chamber method of measuring particle diffusion though mucus gels is relatively simple to use and allows measurement of long-time effective diffusion coefficients. However, observations must be made over time periods of an hour or more, where endogenous protease activity can degrade freshly collected mucus samples significantly to reduce its viscoelasticity up to ~20%, particularly if kept at 37ºC.104 To limit this effect, addition of protease inhibitors such as phenylsulfonylfluoride and sodium azide have been used to slow degradation of mucus during the course of diffusion chamber experiments.22,79 NP may also adhere to the filter that separates the donor compartment from the acceptor compartment, which can be confirmed with control experiments with buffer only.22 There may also be an effect of the buffer in the acceptor compartment altering the overall concentration of mucus, as mucus components may partition into the donor and/or acceptor compartment due to the established osmotic pressure gradient.22 This would in effect reduce the barrier properties of mucus over time in diffusion chamber studies. Given these limitations, the artifacts potentially introduced with the use of the diffusion chamber method for characterizing NP diffusion through the mucus barrier must be carefully accounted for. The methods discussed in the following sections overcome many of the aforementioned limitations.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) has also been used to quantify the effective diffusion rate of NP in biological specimens, including airway mucus.73,90,105 In FRAP, the fluorescence within small area of a sample is rapidly bleached and the recovery of fluorescence within the bleached area is measured. An effective diffusion coefficient of the NP is calculated based on the time to 50% recovery of prebleach fluorescence. The fraction of immobile NP may also be determined based on the plateau of the FRAP intensity profile (Figure 4b).73 An advantage of FRAP over the diffusion chamber method is that NP may be added directly to mucus samples with minimal dilution to assess their transport behavior. Additionally, proteolytic degradation of mucus during the course of the experiment can be minimized since the measurements can be made within minutes.

FRAP has been used to measure the diffusion of fluorescently labeled (i.e., fluorescein isothiocyanate, or FITC) dextran in CF mucus. Braeckmans et al., found that the effective diffusion coefficients of FITC-labeled dextran molecules, with hydrodynamic radii of 9, 15, and 33 nm, were size-independent in CF mucus, with nearly complete fluorescence recovery (>90%) in all cases.73 This result suggested that dextran molecules of the sizes used were capable of diffusing relatively unhindered through pores within the mucus mesh. Based on the diffusion rates of dextran measured in CF mucus, the viscosity of the interstitial fluid of CF mucus was estimated to be only from fourfold to sixfold higher than that of water.73 Mucus interstitial fluid viscosities have also been measured by FRAP using 70 kDa fluorescent dextran (≈6 nm hydrodynamic radius73) in mucus samples collected from the airway surface liquid of a genetic CF pig model106 and in mucus secreted from air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures of CF human bronchial epithelium.106,107 These studies reported interstial fluid viscosities roughly fourfold to eightfold higher than water. FRAP studies using 37 and 89 nm PS NP in CF mucus revealed substantial fractions of immobile particles, 62 and 44% respectively, which was most likely due to PS NP adhesion to hydrophobic protein domains of mucins within the mucus mesh.73 Similarly, 76% of 100 nm, 46% of 200 nm, and 86% of 500 nm PS NP were immobilized in ex vivo porcine airway mucus collected from excised tracheas.98

FRAP is particularly useful in the assessment of the diffusion behavior of small NP with low fluorescence intensity and/or NP undergoing diffusion that is so rapid that reliable individual particle tracking (discussed in Section “Particle tracking”) is not feasible. In addition, diffusion over physiologically-relevant distances (i.e., several microns) can be assessed using FRAP. The percentage of gene vectors that are likely to penetrate the mucus gel layer and reach the PCL prior to removal by MCC can be estimated based on the measured mobile fraction (Figure 3b). In addition, analytical frameworks have been developed to further interpret FRAP experiments in systems with multiple diffusing species with distinct transport behaviors or species undergoing anomalous diffusion (i.e., subdiffusive and superdiffusive).108,109,110 A drawback in the use of FRAP is that NP of interest must be sufficiently concentrated within the mucus sample to produce a bright and uniform fluorescent background.72 Highly concentrated NP cause aggregation of mucin fibers if they are mucoadhesive,90 which causes significant alterations to the mucus microstructure including increased mesh size.111

Particle tracking

High-resolution multiple particle tracking (MPT) (Figure 4c), has been used to quantitatively describe the motions of hundreds of individual NP over short time periods within mucus obtained from the airways of humans and animals.8,9,10,11,23,65,78,80–83,112 The key features of particle tracking and important considerations for performing informative particle tracking studies were comprehensively reviewed recently.113 Briefly, this technique employs an epifluorescent or confocal microscope equipped with a high magnification objective and a high speed camera capable of obtaining snapshots on microsecond timescales. To track individual objects, NP must exhibit a fluorescence intensity that allows them to be reliably identified against background mucus autofluorescence which can be substantial in airway mucus samples collected from patients with obstructive lung diseases.113 As with FRAP, particle tracking experiments can be conducted rapidly to avoid proteolytic degradation of mucus samples during the course of the experiment. NP to be tracked can be added to the sample with minimal dilution (e.g., <3% v/v) of airway mucus, thereby preserving physiological mucus properties.83 Importantly, the relatively low final working concentrations of particles required for particle tracking minimize concerns over NP aggregation and/or mucus bundling.

To characterize the barrier properties of airway mucus, MPT has been used to quantify the diffusion of PS NP possessing various physicochemical properties in porcine airway mucus,98 as well as human airway mucus from healthy individuals23 and individuals with CF.65,78,83,112 These studies have collectively demonstrated the effects of NP size and surface chemistry on the extent of hindrance to mucus penetration where they have shown NP must possess diameters less than the characteristic mucus mesh size (100–200 nm) and be nonadhesive to mucus in order to efficiently penetrate through the mucus barrier. As described earlier, diffusion of leading viral10,11 and nonviral8,9,80,81,82 gene vectors in human airway mucus has been assessed using MPT, and these studies revealed that the mucus gel is a highly effective adhesive barrier even to particulates that are smaller than the mucus mesh size. In addition, MPT has been used to investigate strategies of modulating the airway mucus barrier9,11 and/or gene vectors characteristics8,9,80,81,82 to enhance mucus penetration.

The primary read-out of MPT experiments is the mean squared displacement of tracked particulates, which is a measure of distance traveled by a particle over a given time interval (i.e., timescale) (Figure 4c).43,113,114,115 Concerns have been raised related to the ability of MPT diffusion measurements made over a few seconds to predict the diffusion of particles over physiologically relevant times (which may take minutes or longer). A recent study, employing both FRAP and MPT assessments of PS NP transport in porcine airway mucus, found contrasting trends in particle mobility as a function of particle size. Using MPT, Murgia et al., showed that 100 and 200 nm PS exhibited similar mobile fractions, 43 and 51% respectively, but based on FRAP analysis, the mobile fraction of 100 nm PS NP was twofold less than that of 200 nm PS NP.98 These results suggest differences in short- versus long-time diffusion behavior of mucoadhesive PS NP in porcine airway mucus. Conversely, prior studies showed that nonmucoadhesive gene vectors that exhibited greater diffusion rates in human CF mucus, as assessed by MPT, also provided more widespread distribution in vivo throughout mouse airways following inhalation.80,82 The contrasting findings may be a result of the use of mucoadhesive versus nonmucoadhesive NP in the studies, as well as the source of airway mucus samples used. Ultimately, MPT and/or FRAP experiments in ex vivo airway mucus combined with in vivo evaluations in relevant animal models provides a thorough assessment of inhaled gene vectors that may more accurately predict their performance for inhaled gene therapy trials in humans.

Of note, FRAP and particle tracking require fluorescence labeling of gene vectors, which may alter their natural properties and affect their diffusion behavior in airway mucus. Internal labeling is unlikely to affect NP surface characteristics and is ideal for labeling of inhaled gene vectors for these studies. External labeling must be confirmed to not significantly impact the surface properties of NP, for example, by adjusting the type and/or degree of fluorescence dye conjugation. For example, Schuster et al., demonstrated that the external labeling strategy they used with an Alexa Fluor dye did not affect the natural ability of AAV2 to infect cells.11 In addition, the diffusion within CF mucus of muco-inert PS-PEG NP, externally labeled with this dye at a similar surface dye density, was unaffected and, thus, indirectly showed that it should not impact AAV diffusion.11

Mucus Samples Used to Assess Mucus Barrier Properties

Source of mucus

The potential of inhaled gene vectors to overcome the airway mucus gel barrier should be assessed in samples that possess barrier properties similar to those found in human airways. Thus, samples used should ideally be freshly-obtained from human airways or animals with similar airway physiology. Mucus produced in other tissues can have significantly different composition and, as a result, it may possess different barrier properties.5 For example, the average pore size of cervicovaginal mucus from healthy women has been estimated to be 340 ± 70 nm,116 which is significantly larger than estimates of the average pore size in human airway mucus.9,11,22,23 The pH of airway mucus is near neutral, whereas the pH of mucus at other mucosal surfaces of the body may vary substantially. For example, human cervicoginal mucus from women can vary from quite acidic (e.g., pH < 4) to neutral or even slightly basic in women with bacterial vaginosis, and gastric mucus generally has a pH ≤ 3.33 Differences in pH may cause variation in the biochemical and biophysical properties of mucus, specifically the net charge of mucin fibers, thereby potentially altering its barrier properties.33,97 It should also be noted that nasal and salivary mucus has quite different composition and rheological properties compared with airway mucus43 and, thus, these sources may not be ideal. Lastly, several prior studies investigating mucus penetration of NP have been carried out with artificially-reconstructed “mucus” that was composed of commercially available components, such as mucin, DNA, actin, lipids and albumin.117,118,119 However, commercially available, purified mucins do not readily form a viscoelastic gel with rheological properties comparable to native mucus samples at physiological concentrations.120 The processing of these purified mucins yields uncross-linked mucin fibers that do not readily form a gel. Thus, synthetic mucus gels may not possess the barrier properties of human airway mucus.

Freshly-obtained and minimally-manipulated human airway mucus is the most desirable material with which to evaluate mucus gel barrier properties to gene vectors. Human airway mucus can be directly collected during bronchoscopy,19 or from endotracheal tubes used during general anesthesia.20,23 However, sample collection in these cases requires access to individuals undergoing a surgical procedure. Alternatively, airway mucus samples can be collected from subjects who cough it out, and these samples are generally called sputum. For simplicity, we have used the term mucus to describe both mucus- and sputum-based studies to this point. Expectoration of sputum can be induced by inhalation of hypertonic saline. However, samples collected in this way may be diluted, which may alter mucus barrier properties.121 For example, a recent study found that the total solids content was reduced in induced versus bronchoscopy-derived (i.e., undiluted) samples from the same patients.122 In contrast, spontaneously expectorated sputum can be used with negligible concern of sample dilution. However, spontaneously expectorated samples are generally produced by patients who have a respiratory disease, such as CF, COPD or asthma.123 In all cases, sputum should be carefully collected to minimize contamination by saliva.58,59 A common limitation inherent to all human mucus samples is significant variation in biophysical properties of specimens obtained from individual subjects and/or patients.11,19,123 Thus, evaluation with multiple samples is generally required to allow reliable characterization of the barrier properties of human airway mucus.

Human mucus secretions obtained from in vitro human tissue cultures grown at the ALI have been shown to recapitulate native airway mucus bulk viscoelasticity at physiological concentrations.99 However, this method requires repeated collection of mucus by washing the apical side of human ALI tissue cultures with saline until sufficient mucus volumes are collected.124 It then requires extensive washing and dialysis steps to remove cellular debris and concentrate the mucus collected.124 In addition, these samples may not be suitable for investigating mucus barrier properties in people with obstructive lung diseases. Key components found in airway secretions in people with obstructive lung diseases, including DNA and actin, are not present in tissue culture-derived mucus samples.

Mucus obtained from laboratory animals is often more readily available than human sources. Mucus from rats125 and pigs98 has been collected by carefully scraping the surface of the larynx and/or trachea, which are excised following animal sacrifice. Airway mucus has also been directly collected from anesthetitized dogs,126 ferrets,127 and horses128 by placing a cytology brush in the trachea of animals onto which mucus accumulates as a result of MCC. Animals with larger airway dimensions share similar mucus properties129 and, thus, may be desirable as surrogates to human mucus collection. Genetically engineered CF lung disease models based on pigs have been extensively studied, as these models spontaneously develop CF-like respiratory complications similar to those seen in humans largely due to similarities in airway physiology.130,131 Normal pig airway mucus has bulk rheological properties that are similar to normal human airway mucus.98 Similarly, airway mucus collected from dogs has been found to share similar bulk rheological properties to that of humans with only a slightly increased viscoelasticity (+2%).129 In contrast, mucus bulk viscoelasticity greater than human mucus has been reported for airway mucus samples obtained from other animals, including ferrets (+17%), rats (+20%), and rabbits (+30%).129 It should also be noted that a careful comparison of animal versus human airway mucus barrier properties at the microscale level has not yet been performed to establish the relevance of the various laboratory animal mucus.

Storage and processing of mucus

Proper handling of mucus is also important in order to reliably assess the relevant mucus barrier properties to gene vectors. In order to ensure that mucus samples retain their native barrier properties, freshly collected, undiluted mucus samples should be used. Storage or processing steps may significantly alter the physicochemical properties of mucus gels and, thus, change their physiological barrier properties. For example, diluting or concentrating mucus samples, by adding or removing fluid, changes the mucus solid concentrations and, thus, overall barrier properties. As discussed earlier, endogenous protease activity can significantly reduce mucus viscoelasticity when kept at 37ºC for 60 minutes due to degradation of mucins.104 While storage of samples at lower temperatures may reduce protease activity, it is important to ensure that the storage conditions used do not alter physiological mucus barrier properties. Frozen airway mucus samples have been found to retain their bulk viscoelastic properties.22,112 However, it has yet to be reported if the freezing and thawing process leads to the alteration of mucus properties at the microscale.

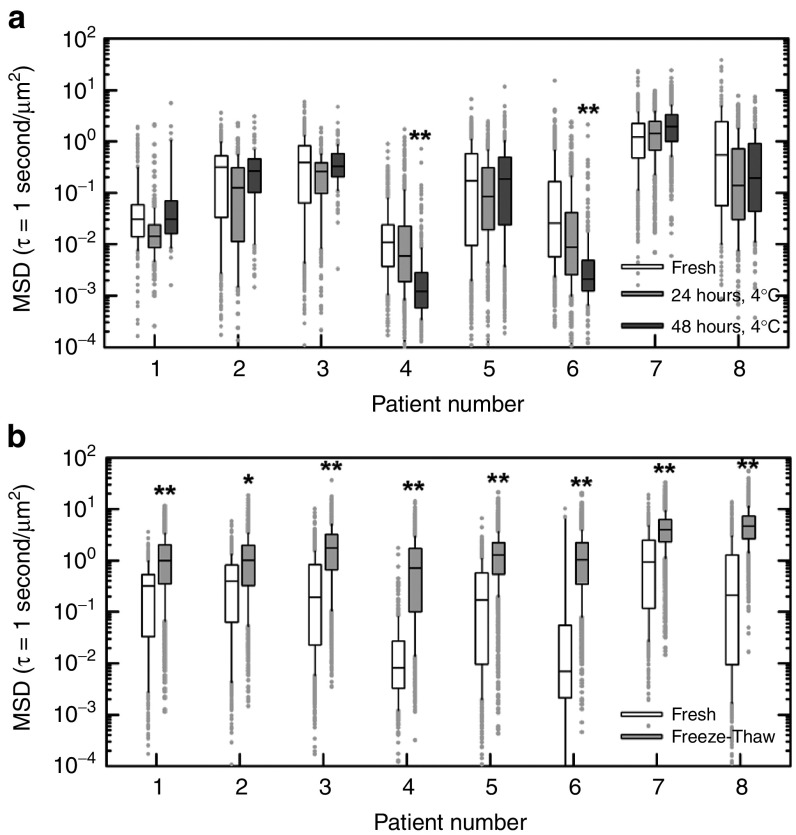

To examine the potential effects of refrigeration and freezing on mucus microstructure, we used MPT to measure the diffusion rates of nonmucoadhesive PS-PEG NP (NP diameter ~100 nm) in spontaneously expectorated CF sputum that was maintained under various storage conditions. We compared the barrier properties of fresh, undiluted CF sputum shortly after collection (“fresh mucus”) to those of the same samples after storage at 4ºC for 24 or 48 hours, or to the same samples after freezing at −80ºC followed by thawing on ice (Figure 5). Identical aliquots of individual samples were used to compare fresh mucus versus mucus stored at different conditions to avoid potential effects of intrasample variation. A Mann-Whitney test was performed to determine if mean-squared displacement at a timescale of 1 second of 100 nm PS-PEG NP in refrigerated or frozen CF sputum samples differed from that of the same PS-PEG NP in fresh samples. For all samples tested, we found that the mean-squared displacement of 100 nm PS-PEG was not altered in a statistically-significant manner in samples stored at 4ºC for 24 hours compared with freshly collected samples, suggesting that this storage condition does not significantly alter CF sputum barrier properties (Figure 5a). However, after storage at 4ºC for 48 hours, the diffusion rates of PS-PEG NP were significantly reduced in two out of eight CF sputum samples tested (Figure 5a). We also found that PS-PEG NP mean-squared displacement was significantly increased in all eight freeze-thawed CF sputum samples compared with the identical samples when they were fresh (Figure 5b), indicating that freezing altered the barrier properties of CF sputum.

Figure 5.

Effects of storage on cystic fibrosis (CF) sputum microstructural properties. (a–b) Box-and-whisker plots of measured mean squared displacement (MSD) in µm2 at time scale τ = 1 second of 100 nm PEG-coated polystyrene nanoparticles (PS-PEG NP) in spontaneously expectorated sputum samples from eight CF patients. (a) Transport rates of 100 nm PS-PEG NP in CF sputum samples immediately after collection (Fresh; white bars), after 24 hours storage at 4ºC (24 hours, 4ºC; light gray bar) and after 48 hours storage at 4ºC (48 hours, 4ºC; dark gray bar). (b) Transport rates of 100 nm PS-PEG NP in CF sputum samples immediately after collection (fresh; white bars) and after being frozen at −80ºC overnight and subsequently thawed on ice (freeze-thaw; light gray bar). A Mann-Whitney test was used to determine statistically significant differences in MSD values (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). The data presented in parts a and b were collected from two independent patient cohorts. To avoid a concern of potential intrasample variation, identical aliquots of individual samples were used to compare MSD of 100 nm PS-PEG NP in fresh mucus versus mucus stored at different conditions. Briefly, 0.5 µl solution of fluorescently labeled 100 nm PS-PEG NP was added to 30 µl of CF sputum in a custom-made microwell. Samples were imaged at room temperature using an Axio Observer inverted epifluorescence microscope equipped with 100x/1.46 NA oil-immersion objective. Movies were recorded over 20 seconds at an exposure time of 67 milliseconds (i.e., 15 frames per second) by an Evolve 512 EMCCD camera. Movies were analyzed using a custom-made MATLAB code to simultaneously extract x, y-coordinates of >500 NP per sample aliquot to calculate MSD values. One 30 µl aliquot of CF sputum from each patient was assessed following sample collection (i.e., fresh) and after storage at 4ºC for 24 and 48 hours. A second 30 µl aliquot was assessed following sample collection and after freezing at −80ºC overnight and thawing on ice. For evaluating the effect of freeze-thaw on CF sputum barrier properties, fresh yellow-green (505/515 nm) fluorescent 100 nm PS-PEG NP were added to the freeze-thawed aliquot due to concerns over of the effects of freezing on the red (580/605 nm) fluorescent 100 nm PS-PEG NP previously added to assess the fresh sample. To confirm the particle sets were comparable, the size and ζ-potential for each set of 100 nm PS-PEG were measured by dynamic light scattering and laser Doppler anemometry, respectively. Yellow-green and red PS-PEG NP had diameters of 104 ± 0.3 and 107 ± 1.3 nm; and ζ-potential of −4.4 ± 0.3 and −4.7 ± 0.2 mV, respectively.

The findings here suggest that the barrier properties of expectorated CF sputum samples may be altered after storage over long times (> 24 hours) at 4ºC or after a freeze-and-thaw cycle. However, we note that effects of different storage conditions on the barrier properties of airway mucus may vary depending on the collection method (i.e., direct collection via bronchoscopy/endotracheal tube, spontaneously expectorated or induced sputum) and/or source of mucus (i.e., human or animal sources). To ensure accurate characterization of physiological mucus barrier properties, investigators should carefully assess the effects of storage on the airway mucus and measurement techniques used in their studies.

Conclusions

Localized gene therapy via inhalation is likely to provide the best chance for efficacy in various diseases that affect the lungs. However, physiological barriers to gene delivery in the airways have prevented success in human clinical trials thus far. In particular, the highly viscoelastic mucus gel layer within the airways has been shown to effectively trap, and facilitate removal of, inhaled gene vectors before they reach the underlying epithelium. Furthermore, the barrier properties of the mucus gel layer are markedly enhanced in patients suffering with respiratory diseases and, thus, present an even more challenging obstacle to successful inhaled gene therapy. As new gene vectors emerge, it is critical that they be carefully screened, using the most advanced methods available and using relevant mucus samples, for the ability to rapidly penetrate human airway mucus gels from the patient population for which they are intended.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (R01HL127413 and R01HL125169) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for funding of this work. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- Griesenbach, U and Alton, EW; UK Cystic Fibrosis Gene Therapy Consortium (2009). Gene transfer to the lung: lessons learned from more than 2 decades of CF gene therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 61: 128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, S, Geddes, DM and Alton, EW (2002). Barriers to and new approaches for gene therapy and gene delivery in cystic fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 54: 1373–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, N, Rudolph, C, Braeckmans, K, De Smedt, SC and Demeester, J (2009). Extracellular barriers in respiratory gene therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 61: 115–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, SK, Wang, YY and Hanes, J (2009). Mucus-penetrating nanoparticles for drug and gene delivery to mucosal tissues. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 61: 158–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone, RA (2009). Barrier properties of mucus. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 61: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy, JV and Dickey, BF (2010). Airway mucus function and dysfunction. N Engl J Med 363: 2233–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, MR and Boucher, RC (2002). Mucus clearance as a primary innate defense mechanism for mammalian airways. J Clin Invest 109: 571–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan, NJ, Suk, JS, Lai, SK, Jelinek, R, Boyle, MP, Cooper, MJ et al. (2012). Highly compacted DNA nanoparticles with low MW PEG coatings: in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo evaluation. J Control Release 157: 72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk, JS, Boylan, NJ, Trehan, K, Tang, BC, Schneider, CS, Lin, JM et al. (2011). N-acetylcysteine enhances cystic fibrosis sputum penetration and airway gene transfer by highly compacted DNA nanoparticles. Mol Ther 19: 1981–1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hida, K, Lai, SK, Suk, JS, Won, SY, Boyle, MP and Hanes, J (2011). Common gene therapy viral vectors do not efficiently penetrate sputum from cystic fibrosis patients. PLoS One 6: e19919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, BS, Kim, AJ, Kays, JC, Kanzawa, MM, Guggino, WB, Boyle, MP et al. (2014). Overcoming the cystic fibrosis sputum barrier to leading adeno-associated virus gene therapy vectors. Mol Ther 22: 1484–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button, B, Cai, LH, Ehre, C, Kesimer, M, Hill, DB, Sheehan, JK et al. (2012). A periciliary brush promotes the lung health by separating the mucus layer from airway epithelia. Science 337: 937–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher, RC (2004). Relationship of airway epithelial ion transport to chronic bronchitis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 1: 66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, H, Grubb, BR, Tarran, R, Randell, SH, Gatzy, JT, Davis, CW et al. (1998). Evidence for periciliary liquid layer depletion, not abnormal ion composition, in the pathogenesis of cystic fibrosis airways disease. Cell 95: 1005–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarran, R (2004). Regulation of airway surface liquid volume and mucus transport by active ion transport. Proc Am Thorac Soc 1: 42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y, Namkung, W, Nielson, DW, Lee, JW, Finkbeiner, WE and Verkman, AS (2009). Airway surface liquid depth measured in ex vivo fragments of pig and human trachea: dependence on Na+ and Cl- channel function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L1131–L1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, DJ and Sheehan, JK (2004). From mucins to mucus: toward a more coherent understanding of this essential barrier. Proc Am Thorac Soc 1: 54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voynow, JA and Rubin, BK (2009). Mucins, mucus, and sputum. Chest 135: 505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanneret-Grosjean, A, King, M, Michoud, MC, Liote, H and Amyot, R (1988). Sampling technique and rheology of human tracheobronchial mucus. Am Rev Respir Dis 137: 707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, BK, Ramirez, O, Zayas, JG, Finegan, B and King, M (1990). Collection and analysis of respiratory mucus from subjects without lung disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 141(4 Pt 1): 1040–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk, CK and Dulfano, MJ (1983). Effect of pH, viscosity and ionic-strength changes on ciliary beating frequency of human bronchial explants. Clin Sci (Lond) 64: 449–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, NN, De Smedt, SC, Van Rompaey, E, Simoens, P, De Baets, F and Demeester, J (2000). Cystic fibrosis sputum: a barrier to the transport of nanospheres. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 1905–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, BS, Suk, JS, Woodworth, GF and Hanes, J (2013). Nanoparticle diffusion in respiratory mucus from humans without lung disease. Biomaterials 34: 3439–3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randell, SH and Boucher, RC; University of North Carolina Virtual Lung Group (2006). Effective mucus clearance is essential for respiratory health. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 35: 20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeates, DB, Aspin, N, Levison, H, Jones, MT and Bryan, AC (1975). Mucociliary tracheal transport rates in man. J Appl Physiol 39: 487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster, WM, Langenback, E and Bergofsky, EH (1980). Measurement of tracheal and bronchial mucus velocities in man: relation to lung clearance. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 48: 965–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning, A, Schneider, M, Nafee, N, Muijs, L, Rytting, E, Wang, X et al. (2010). Influence of particle size and material properties on mucociliary clearance from the airways. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 23: 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, SH, Corcoran, TE, Laube, BL and Bennett, WD (2007). Mucociliary clearance as an outcome measure for cystic fibrosis clinical research. Proc Am Thorac Soc 4: 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesimer, M, Ehre, C, Burns, KA, Davis, CW, Sheehan, JK and Pickles, RJ (2013). Molecular organization of the mucins and glycocalyx underlying mucus transport over mucosal surfaces of the airways. Mucosal Immunol 6: 379–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N, Duncan, GA, Hanes, J and Suk, JS (2016). Barriers to inhaled gene therapy of obstructive lung diseases: a review. J Control Release 240: 465–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamblin, G, Degroote, S, Perini, JM, Delmotte, P, Scharfman, A, Davril, M et al. (2001). Human airway mucin glycosylation: a combinatory of carbohydrate determinants which vary in cystic fibrosis. Glycoconj J 18: 661–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, MC and Voynow, JA (2006). Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev 86: 245–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieleg, O, Vladescu, I and Ribbeck, K (2010). Characterization of particle translocation through mucin hydrogels. Biophys J 98: 1782–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, JK, Thornton, DJ, Somerville, M and Carlstedt, I (1991). Mucin structure. The structure and heterogeneity of respiratory mucus glycoproteins. Am Rev Respir Dis 144(3 Pt 2): S4–S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, DJ, Rousseau, K and McGuckin, MA (2008). Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu Rev Physiol 70: 459–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesimer, M, Kirkham, S, Pickles, RJ, Henderson, AG, Alexis, NE, Demaria, G et al. (2009). Tracheobronchial air-liquid interface cell culture: a model for innate mucosal defense of the upper airways? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L92–L100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler, KB, Tuvim, MJ and Dickey, BF (2013). Regulated mucin secretion from airway epithelial cells. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 4: 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, EY, Yang, N, Quinton, PM and Chin, WC (2010). A new role for bicarbonate in mucus formation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299: L542–L549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham, S, Sheehan, JK, Knight, D, Richardson, PS and Thornton, DJ (2002). Heterogeneity of airways mucus: variations in the amounts and glycoforms of the major oligomeric mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B. Biochem J 361(Pt 3): 537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, K, Kirkham, S, McKane, S, Newton, R, Clegg, P and Thornton, DJ (2007). Muc5b and Muc5ac are the major oligomeric mucins in equine airway mucus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L1396–L1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buisine, MP, Devisme, L, Copin, MC, Durand-Réville, M, Gosselin, B, Aubert, JP et al. (1999). Developmental mucin gene expression in the human respiratory tract. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 20: 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, AG, Ehre, C, Button, B, Abdullah, LH, Cai, LH, Leigh, MW et al. (2014). Cystic fibrosis airway secretions exhibit mucin hyperconcentration and increased osmotic pressure. J Clin Invest 124: 3047–3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, SK, Wang, YY, Wirtz, D and Hanes, J (2009). Micro- and macrorheology of mucus. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 61: 86–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collawn, JF, and Matalon, S (2014). CFTR and lung homeostasis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell and Mol Physiol 35294: ajplung.00326.02014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilewski, JM and Frizzell, RA (1999). Role of CFTR in airway disease. Physiol Rev 79(1 Suppl): S215–S255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, TS and Prince, A (2012). Cystic fibrosis: a mucosal immunodeficiency syndrome. Nat Med 18: 509–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl, D, Gaggar, A, Bruscia, E, Hector, A, Marcos, V, Jung, A et al. (2012). Innate immunity in cystic fibrosis lung disease. J Cyst Fibros 11: 363–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, AR, Jain, M, Bar-Meir, M and McColley, SA (2011). Clinical significance of microbial infection and adaptation in cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 24: 29–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, SM, Miller, S and Sorscher, EJ (2005). Cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med 352: 1992–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decramer, M, Janssens, W and Miravitlles, M (2012). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 379: 1341–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, AD, Shibuya, K, Rao, C, Mathers, CD, Hansell, AL, Held, LS et al. (2006). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J 27: 397–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuder, RM and Petrache, I (2012). Pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest 122: 2749–2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, CM, Kim, K, Tuvim, MJ and Dickey, BF (2009). Mucus hypersecretion in asthma: causes and effects. Curr Opin Pulm Med 15: 4–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izuhara, K, Ohta, S, Shiraishi, H, Suzuki, S, Taniguchi, K, Toda, S et al. (2009). The mechanism of mucus production in bronchial asthma. Curr Med Chem 16: 2867–2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcillo, EJ and Cortijo, J (2006). Mucus and MUC in asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 12: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas, JG, Rubin, BK, York, EL, Lien, DC and King, M (1999). Bronchial mucus properties in lung cancer: relationship with site of lesion. Can Respir J 6: 246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas, JG, Man, GC and King, M (1990). Tracheal mucus rheology in patients undergoing diagnostic bronchoscopy. Interrelations with smoking and cancer. Am Rev Respir Dis 141(5 Pt 1): 1107–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serisier, DJ, Carroll, MP, Shute, JK and Young, SA (2009). Macrorheology of cystic fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease & normal sputum. Respir Res 10: 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman, J and Reid, L (1972). Sputum viscosity in chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis, asthma and cystic fibrosis. Biorheology 9: 185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerveri, I and Brusasco, V (2010). Revisited role for mucus hypersecretion in the pathogenesis of COPD. Eur Respir Rev 19: 109–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, DF (2007). Physiology of airway mucus secretion and pathophysiology of hypersecretion. Respiratory Care 52: 1134–1146; discussion 1146–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, DF and Barnes, PJ (2006). Treatment of airway mucus hypersecretion. Ann Med 38: 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, H, Verghese, MW, Kesimer, M, Schwab, UE, Randell, SH, Sheehan, JK et al. (2005). Reduced three-dimensional motility in dehydrated airway mucus prevents neutrophil capture and killing bacteria on airway epithelial surfaces. J Immunol 175: 1090–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S, Hollinger, M, Lachowicz-Scroggins, ME, Kerr, SC, Dunican, EM, Daniel, BM et al. (2015). Oxidation increases mucin polymer cross-links to stiffen airway mucus gels. Sci Transl Med 7: 276ra27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk, JS, Lai, SK, Boylan, NJ, Dawson, MR, Boyle, MP and Hanes, J (2011). Rapid transport of muco-inert nanoparticles in cystic fibrosis sputum treated with N-acetyl cysteine. Nanomedicine (Lond) 6: 365–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham, PA and Barnes, PJ (2013). Oxidative stress in COPD. Chest 144: 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, YS and Moon, HB (2010). The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2: 183–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, EY, Yang, N, Quinton, PM and Chin, WC (2010). A new role for bicarbonate in mucus formation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299: L542–L549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton, PM (2008). Cystic fibrosis: impaired bicarbonate secretion and mucoviscidosis. The Lancet 372: 415– 417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rab, A, Rowe, SM, Raju, SV, Bebok, Z, Matalon, SandCollawn, JF (2013). Cigarette smoke and CFTR: implications in the pathogenesis of COPD. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 305: L530–L541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, GA, Jung, J, Joseph, A, Thaxton, AT, West, NE, Boyle, MP et al. (2016). Microstructural alterations of sputum in cystic fibrosis lung disease. JCI Insight (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vasconcellos, CA, Allen, PG, Wohl, ME, Drazen, JM, Janmey, PA and Stossel, TP (1994). Reduction in viscosity of cystic fibrosis sputum in vitro by gelsolin. Science 263: 969–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braeckmans, K, Peeters, L, Sanders, NN, De Smedt, SC and Demeester, J (2003). Three-dimensional fluorescence recovery after photobleaching with the confocal scanning laser microscope. Biophys J 85: 2240–2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton, JW, Stewart, PS and Greenberg, EP (1999). Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284: 1318–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau-Marquis, S, Stanton, BA and O'Toole, GA (2008). Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation in the cystic fibrosis airway. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 21: 595–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messiaen, AS, Forier, K, Nelis, H, Braeckmans, K and Coenye, T (2013). Transport of nanoparticles and tobramycin-loaded liposomes in Burkholderia cepacia complex biofilms. PLoS One 8: e79220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forier, K, Messiaen, AS, Raemdonck, K, Nelis, H, De Smedt, S, Demeester, J et al. (2014). Probing the size limit for nanomedicine penetration into Burkholderia multivorans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. J Control Release 195: 21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forier, K, Messiaen, AS, Raemdonck, K, Deschout, H, Rejman, J, De Baets, F et al. (2013). Transport of nanoparticles in cystic fibrosis sputum and bacterial biofilms by single-particle tracking microscopy. Nanomedicine (Lond) 8: 935–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, NN, De Smedt, SC and Demeester, J (2003). Mobility and stability of gene complexes in biogels. J Control Release 87: 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk, JS, Kim, AJ, Trehan, K, Schneider, CS, Cebotaru, L, Woodward, OM et al. (2014). Lung gene therapy with highly compacted DNA nanoparticles that overcome the mucus barrier. J Control Release 178: 8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, AJ, Boylan, NJ, Suk, JS, Hwangbo, M, Yu, T, Schuster, BS et al. (2013). Use of single-site-functionalized PEG dendrons to prepare gene vectors that penetrate human mucus barriers. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 52: 3985–3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastorakos, P, da Silva, AL, Chisholm, J, Song, E, Choi, WK, Boyle, MP et al. (2015). Highly compacted biodegradable DNA nanoparticles capable of overcoming the mucus barrier for inhaled lung gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 8720–8725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk, JS, Lai, SK, Wang, YY, Ensign, LM, Zeitlin, PL, Boyle, MP et al. (2009). The penetration of fresh undiluted sputum expectorated by cystic fibrosis patients by non-adhesive polymer nanoparticles. Biomaterials 30: 2591–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechecchi, MC, Melotti, P, Bonizzato, A, Santacatterina, M, Chilosi, M and Cabrini, G (2001). Heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans are receptors sufficient to mediate the initial binding of adenovirus types 2 and 5. J Virol 75: 8772–8780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechecchi, MC, Tamanini, A, Bonizzato, A and Cabrini, G (2000). Heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans are involved in adenovirus type 5 and 2-host cell interactions. Virology 268: 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters, RW, Yi, SM, Keshavjee, S, Brown, KE, Welsh, MJ, Chiorini, JA et al. (2001). Binding of adeno-associated virus type 5 to 2,3-linked sialic acid is required for gene transfer. J Biol Chem 276: 20610–20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerford, C and Samulski, RJ (1998). Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol 72: 1438–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z, Miller, E, Agbandje-McKenna, M and Samulski, RJ (2006). Alpha2,3 and alpha2,6 N-linked sialic acids facilitate efficient binding and transduction by adeno-associated virus types 1 and 6. J Virol 80: 9093–9103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X, Steukers, L, Forier, K, Xiong, R, Braeckmans, K, Van Reeth, K et al. (2014). A beneficiary role for neuraminidase in influenza virus penetration through the respiratory mucus. PLoS One 9: e110026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmsted, SS, Padgett, JL, Yudin, AI, Whaley, KJ, Moench, TR and Cone, RA (2001). Diffusion of macromolecules and virus-like particles in human cervical mucus. Biophys J 81: 1930–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, YY, Kannan, A, Nunn, KL, Murphy, MA, Subramani, DB, Moench, T, et al. (2014). IgG in cervicovaginal mucus traps HSV and prevents vaginal Herpes infections. Mucosal Immunology 7: 1036–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirmule, N, Propert, K, Magosin, S, Qian, Y, Qian, R and Wilson, J (1999). Immune responses to adenovirus and adeno-associated virus in humans. Gene Ther 6: 1574–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcedo, R, Vandenberghe, LH, Gao, G, Lin, J and Wilson, JM (2009). Worldwide epidemiology of neutralizing antibodies to adeno-associated viruses. J Infect Dis 199: 381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert, CL, Miller, AD, McNamara, S, Emerson, J, Gibson, RL, Ramsey, B et al. (2006). Prevalence of neutralizing antibodies against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 2, 5, and 6 in cystic fibrosis and normal populations: Implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum Gene Ther 17: 440–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q and Lai, SK (2015). Anti-PEG immunity: emergence, characteristics, and unaddressed questions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 7: 655–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton-Head, VJ, Smith, JR, Shur, J and Shute, JK (2007). Actin limits enhancement of nanoparticle diffusion through cystic fibrosis sputum by mucolytics. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 20: 708–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieleg, O and Ribbeck, K (2011). Biological hydrogels as selective diffusion barriers. Trends Cell Biol 21: 543–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgia, X, Pawelzyk, P, Schaefer, UF, Wagner, C, Willenbacher, N and Lehr, CM (2016). Size-limited penetration of nanoparticles into porcine respiratory mucus after aerosol deposition. Biomacromolecules 17: 1536–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, DB, Vasquez, PA, Mellnik, J, McKinley, SA, Vose, A, Mu, F et al. (2014). A biophysical basis for mucus solids concentration as a candidate biomarker for airways disease. PLoS One 9: e87681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanvilkar, K, Donovan, MD and Flanagan, DR (2001). Drug transfer through mucus. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 48: 173–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai, MA, Mutlu, M and Vadgama, P (1992). A study of macromolecular diffusion through native porcine mucus. Experientia 48: 22–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larhed, AW, Artursson, P, Gråsjö, J and Björk, E (1997). Diffusion of drugs in native and purified gastrointestinal mucus. J Pharm Sci 86: 660–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, NN, De Smedt, SC and Demeester, J (2000). The physical properties of biogels and their permeability for macromolecular drugs and colloidal drug carriers. J Pharm Sci 89: 835–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley, A, Rousseau, K, Ridley, C, Flight, W, Jones, A, Waigh, TA et al. (2014). Reassessment of the importance of mucins in determining sputum properties in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 13: 260–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman, WM, Radomsky, ML, Whaley, KJ and Cone, RA (1994). Antibody diffusion in human cervical mucus. Biophys J 66(2 Pt 1): 508–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, XX, Ostedgaard, LS, Hoegger, MJ, Moninger, TO, Karp, PH, McMenimen, JD et al. (2016). Acidic pH increases airway surface liquid viscosity in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest 126: 879–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derichs, N, Jin, BJ, Song, Y, Finkbeiner, WE and Verkman, AS (2011). Hyperviscous airway periciliary and mucous liquid layers in cystic fibrosis measured by confocal fluorescence photobleaching. FASEB J 25: 2325–2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, P, Garai, K, Balaji, J, Periasamy, N and Maiti, S (2003). Measuring size distribution in highly heterogeneous systems with fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys J 84: 1977–1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy, N and Verkman, AS (1998). Analysis of fluorophore diffusion by continuous distributions of diffusion coefficients: application to photobleaching measurements of multicomponent and anomalous diffusion. Biophys J 75: 557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorén, N, Hagman, J, Jonasson, JK, Deschout, H, Bernin, D, Cella-Zanacchi, F et al. (2015). Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching in material and life sciences: putting theory into practice. Q Rev Biophys 48: 323–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]