Abstract

Objectives

To explore what it means for patients to live with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as an incurable and constantly progressing disease.

Design

Qualitative longitudinal study using narrative and semistructured interviews. This paper presents findings of the initial interviews. Analysis using grounded theory.

Setting

Lung care clinics and community care in Lower Saxony, Germany.

Participants

17 patients with advanced-stage COPD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) III/IV).

Findings

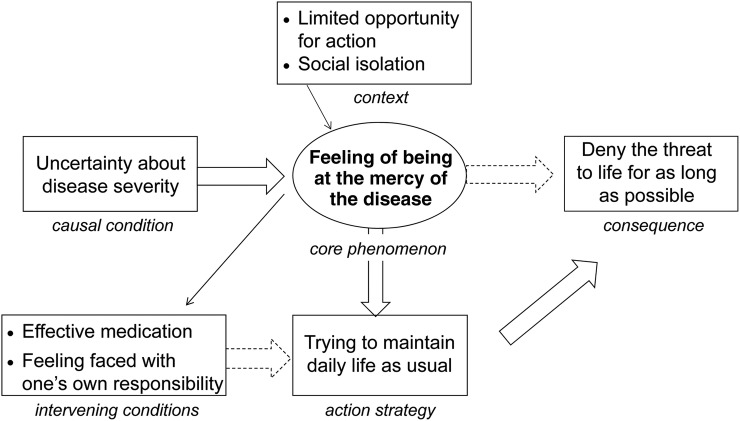

Analysis shows that these patients have difficulties accepting their life situation and feel at the mercy of the disease, which could be identified as a core-experienced phenomenon. Over a long period of time, patients have only a vague feeling of being ill, caused by uncertain knowledge, slow progress and doubtful attribution of clinical symptoms of the disease (causal conditions). As an action strategy, patients try to maintain daily routines for as long as possible after diagnosis. Both effective standard and rescue medication, which helps to reduce breathlessness and other symptoms, and the feeling of being faced with one's own responsibility (intervening conditions) support this strategy, whereby patients' own responsibility is too painful to acknowledge. As a consequence, patients try to deny the threat to life for a long period of time. Frequently, they need to experience facing their own limits, often in the form of an acute crisis, to realise their health situation. The experience of the illness is contextualised by a continuous increase in limited mobility and social isolation.

Conclusion

In order to help patients to improve disease awareness, to accept their life situation and to improve their reduced quality of life, patients may benefit from the early integration of palliative care (PC), considering its multiprofessional patient-centred and team-centred approach. Psychological support and volunteer work, which are relevant aspects of PC, should be appropriate to address psychosocial needs. More research is needed to evaluate how patients could benefit from early PC.

Keywords: QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, Patients' Perspectives, General Practice

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The narrative approach for data collection and analysis enabled the reconstruction of an in-depth view of individual experiences using grounded theory and provided new insights into details of the relevant subject of end-of-life care.

Conducting most of the interviews at the participants' homes made it possible to get a deeper insight into their home and life situation, which was a valuable addition for data analysis, as it enriched the material and enabled a better understanding of the data collected.

Recruitment turned out to be difficult and led to a rather heterogeneous range of physical distress.

Study results are based on a sample of patients living in the middle of Germany. Therefore, patients' experiences in other German regions might be different in some aspects.

In order to help patients cope with their illness and to address their psychosocial needs, providing multiprofessional palliative care early in the disease trajectory might be appropriate.

Background

The increasing prevalence and mortality of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is of high relevance, as this disease is expected to become the third leading cause of death in 2030 worldwide.1 In Germany, 3% of all deaths are caused by COPD,2 whereby the estimated prevalence is about 10–15%.3 COPD is defined as ‘a preventable and treatable disease with some significant extrapulmonary effects that may contribute to the severity in individual patients’.4 Usually, the duration of the disease covers many years or sometimes decades, and even a progressive stage may continue for months or years and differs between patients. The main common symptoms are breathlessness, wheezing, chest tightness and chronic (productive) cough.4

On a population level, the disease trajectory of COPD is characterised by ‘long-term limitations with intermittent serious episodes’.5 More specifically, Bausewein et al6 described four trajectories of breathlessness: fluctuating, increasing, stable and decreasing trajectories, ‘of which fluctuation was the most common’. The current clinical view is that COPD is accompanied by ‘increasing frequency and severity of crises over time’.7 Each of these exacerbations can lead to death, but in many cases do not; therefore, the end-of-life period, or the onset of the final phase, is uncertain and difficult to predict; moreover, patients themselves experience their illness and life story as chaotic, with ‘no clear beginning’.8 For this reason, death from COPD is often experienced as a sudden event. This clinical uncertainty, and patients' recurring recovery, has the effect that COPD is unpredictable and, especially at an advanced stage, must be seen as a tremendous challenge for patients as well as relatives, family carers and healthcare providers, that is, doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, social workers, etc. Moreover, the psychological and physical burden of the disease differs between patients with COPD, and it is now accepted that the burden of the disease goes beyond a purely pulmonary dysfunction.9 Against this background, the focus has shifted to COPD-related aspects of daily life besides medical treatment, such as quality of life or the effect of physiotherapy on deep breathing.9 10

It is known that patients suffering from progressive COPD have poor physical, social and emotional functioning.11–16 Nevertheless, specialised palliative care (PC), with its multiprofessional and patient-centred focus, does not yet seem to be common for these patients until now, as some studies have shown.17–19 In the light of the prospective growth in patient population, outpatient treatment and home care in particular need to be adapted within the individual context. In order to provide appropriate healthcare throughout the illness trajectory, but especially at an advanced stage of the disease, knowledge about individual needs is required. In this paper, we present the partial findings of phase 1 of a comprehensive study conducted in Lower Saxony, Germany, entitled ‘Understanding the Needs and Perspectives of Patients with Incurable Pulmonary Disease at the End of Life and their Relatives: a Qualitative Longitudinal Study’ (for details, see study protocol).20 To achieve a deeper insight on this subject, it is necessary to understand the patients' illness experiences and related needs. Therefore, this study aimed to explore what it means to live with COPD as an incurable and constantly progressing disease. By developing a theory of experiencing COPD, we further tried to describe and understand how single phenomena, which could be reconstructed from the patients' perspectives, are intertwined.

Methods

Design/sampling

To get a deeper insight into patients' experiences, a qualitative study design is appropriate. Since the design of the study is described in detail elsewhere,20 only the main aspects are briefly outlined in this paper. Over a period of 12 months, four serial semistructured interviews were conducted with patients four-monthly (t0–t3). In this paper, we present the findings of initial interviews (t0). At this point, participants were first asked to tell their illness story using narrative interview techniques. Additionally, an interview guide was used to address issues that were not been mentioned by the interviewee. For details of the interview guide, see the published study protocol.20

The study was guided by the principles of grounded theory introduced by Glaser and Strauss21 and further developed by Strauss and Corbin.22 These principles are: (1) data collection and analysis as inter-related processes, (2) the researcher as part of the process, where his or her view on the data needs to be reflected, (3) constant comparative analysis, that is, findings are repeatedly compared with previous concepts and categories (in this process, ‘concepts are grouped to form categories’, which are ‘higher level, more abstract concepts’23) and (4) sampling on theoretical grounds (ie, as an ongoing process on the basis of current findings).21 23 24 Grounded theory as a methodical approach means ‘learning something new about a topic and developing a theory’.24 In other words, developing data-based theoretical explanations (a conceptual framework) of social and psychosocial phenomena and processes in order to try to understand them.23 25

Regarding demographic variables (age, sex, social status, rural residency), we initially used a purposive sampling strategy, but during the process we attempted to follow a theoretical sampling strategy consistently in order to reach a saturated sample with regard to the theory we aimed to develop.21 Inclusion criteria were: diagnosed COPD stage III/IV according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), 20104 breathlessness at rest or under slight physical activity, frequent hospitalisation because of acute bronchopulmonary infection or breathlessness, ability to give informed consent and to participate in an interview in the German language.

Data collection

GM (sociologist, highly experienced in interviewing) and MN (medical student, trained by GM) conducted qualitative face-to-face interviews with patients at their home, during hospital stay or at our clinic, according to the patient's preference. None of them was involved in the care provided to the patients. The interviewers did not provide participants with any personal information. Relatives were not explicitly invited to be present, but if both the patient and the relative agreed, relatives' attendance and narratives were possible. No questions addressing the relatives' perspective had been prepared in advance. In the initial interviews, participants were encouraged to tell their illness story from the occurrence of first symptoms until the present. After these narratives were finished, immanent open-ended questions were asked to generate further illness narratives. The additional interview guide, a modified version of the guide developed by Pinnock et al8 was used and focused on care-related issues such as daily practical experiences, current problems, communication/information needs and suggestions/wishes. No repeat interviews were carried out. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim (transcription convention as online supplementary data); since we used abductive reasoning for data analysis, we decided that transcripts should not be returned to participants. Field notes (eg, interviewer's first interpretations, which had been verified or falsified during the abductive analysis process, impressions of the patient's living situation, or characteristics of the interview situation) were made during and after the interview and were used to enrich data analysis.

bmjopen-2016-011555supp1.pdf (13.8KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Interviews were analysed in German, using all steps of the grounded theory analysis process: open coding, selective coding and axial coding, whereby open coding and selective coding were conducted in an iterative process. Codes were developed open-mindedly by GM, MN, HS and SOB using abductive reasoning26 and discussed within the research team. The coding paradigm developed by Strauss and Corbin22 was used to structure the analysis process. Aspects of this paradigm are: causal conditions, which lead to the core phenomenon, attributes of the context of the phenomenon, additional intervening conditions, action strategies to handle the phenomenon and consequences of actions.27 28 We will present our findings referring to this coding paradigm. Data were analysed using MAXQDA. A professional translator translated the passages of the interviews cited in this paper.

Ethics approval

All participants had been informed about the study details and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the interview. Consent included, among others, the option to withdraw from the study at any time without giving reasons. To protect participants' confidentiality, interviews were transcribed and analysed using pseudonyms.

Findings

Sample

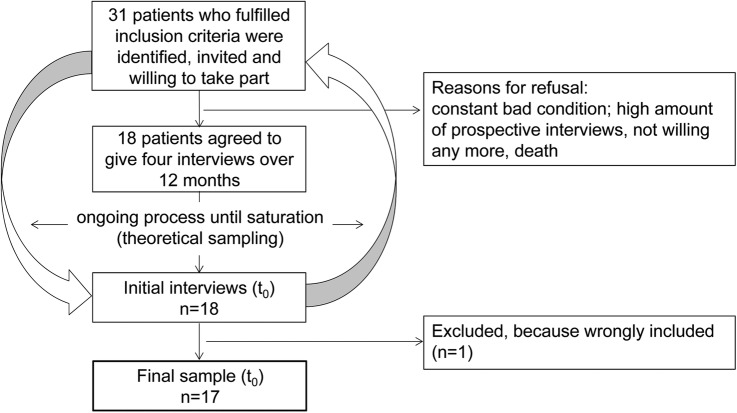

In total, 31 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were invited and willing to take part in the study, of whom 18 finally agreed to give the interviews. The main reason for refusal was the feeling of being overwhelmed by the thought of four interviews over a period of 12 months. Ten participants were included during a hospital stay because of an acute crisis; eight were recruited at a meeting of a COPD support group. Initial interviews lasted about 90 min each. Two interviews were conducted at the specialist hospital, two at the research division, while the others took place, at the patient's request, at their home. Only two of them wanted a relative to be at their side; in one interview, the patient's spouse was present, and in another the patient's daughter. The latter explained some of the patient's narratives, which were systematically taken into account during the interpretative analysis process, as they helped to better understand the patient's perspective. In all other cases, no other person was involved. One participant proved to be not eligible, because of less severe symptoms. This participant was excluded afterwards, so that our final sample comprises 17 participants at baseline (t0). Table 1 shows their characteristics to describe the sample; figure 1 shows the flow chart of sampling.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 18 patients with COPD who gave an initial interview (t0)

| Number of patients | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male/female) | 10/7 |

| Age (range) | 54–78 |

| Housing situation (living together with…) | |

| Solitary | 9 |

| Spouse/life partner | 6 |

| Child | 1 |

| Informal carer | 1 |

| Currently involved professionals | |

| Pulmonologist (outpatient) | 13 |

| Pulmonologist (inpatient) | 1 |

| General physician | 17 |

| Cardiology (outpatient) | 2 |

| Ambulatory specialised palliative care team (physicians and nurses) | 1 |

| Nursing service | 1 |

| Level of care | |

| None | 9 |

| Level 1 | 6 |

| Level 2 | 1 |

| Do not know | 1 |

Figure 1.

Flow chart of sampling.

Categories

Feeling of being at the mercy of the disease

During the constant comparative analysis process using grounded theory, the feeling of being at the mercy of the disease emerged from the data and could be described as core phenomenon when asking what it means to live with advanced COPD. Apparently, the main reason for this is a diffuse feeling of being ill because of slow progress. Patients with COPD feel faced with their responsibility and have to cope with social isolation. As a main strategy, they try to maintain daily life as usual, with the consequence of denying the threat to life for as long as possible. The categories and their connections are shown in figure 2 (for details of the coding tree, see online supplementary file).

Figure 2.

Grounded theory of what it means to live with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

bmjopen-2016-011555supp2.pdf (69.5KB, pdf)

Uncertainty about disease severity

Analysis revealed that patients have limited knowledge about the definition, the cause, the process and the incurability of COPD. Apparently, physicians were not able to inform them sufficiently, that is, in a way that is understandable to the patients. Therefore, patients interpret the course of the disease and their disease situation on their own and, as a result of denial, tend to minimise its severity. They also alleviate clinical symptoms such as short periods of breathlessness or decreasing physical capability, and adapt their daily activities. Slow progress, as well as repeating phases of recovery, leads to a sense of hope that they can someday live their life as usual. ‘Usual’ in this context means as it was before the last crisis, or even before the COPD diagnosis. This uncertainty (vague feeling of being ill) may foster the experience of living with COPD as ‘having a disease’, that is, a feeling of being tainted with something that is not a part of their being, but instead something separate from them.

What I didn't expect was that this disease is not curable […] I thought well, try hard and you'll manage it, but not a bit of it, it's not the case […] but as it's there, yes now it's there now I must try to accept it, (3) I'm about to do so, (3) yes, (5) and hope that I'll get it soon…(CO-01w, female, 71 years).

Patients suffering from COPD obviously experience the feeling of a premature decline, which cannot be influenced and could be worked out during the analysis process as a core phenomenon of experiencing COPD (feeling of being at the mercy of the disease, see above).

Trying to maintain daily life as usual

The main action strategy for patients in coping with the disease-related life situation is to try to maintain normal daily life for as long as possible. The sense of daily ‘normality’ is obviously an appropriate way to cope with helplessness when faced with the feeling of being at the mercy of the disease. Analysis showed that in the case of phased well-being, or when sitting and relaxing, patients tend to minimise the threat and, simultaneously, hope to recover. ‘Normality’ is strongly associated with the need for independence and the avoidance of medical aids to provide functionality (eg, walker, wheelchair) as well as nursing care. As if to demonstrate the absence of their disease, patients tend to go to their physical limits until ‘nothing works anymore’.

At first I didn't take any of it all that seriously ((sniffle)) (3) until last year, when nothing more was possible…(CO-03m, male, 60 years)

Owing to this strategy, most of our study participants narrated that they have remained in employment until they were forced to quit after a severe crisis at a very much advanced level of their disease. It seems that living with COPD is too notional to allow one to feel the disease’s progress. Though they experience progress in attacks, these are followed by phases of recovery.

However, at an advanced stage of COPD, patients depend on help from other persons, as was true for all study participants. In all cases, this support was provided by relatives, some of them in the legal position of informal caregivers, that is, they received reimbursement from the nursing care insurance fund (Pflegekasse) according to the respective level of care.

Effective medication and feeling faced with one's own responsibility

Two intervening conditions could be revealed, which can facilitate and support the action strategies described above: effective medication (symptom control) and patients' feeling of being faced with one's own responsibility concerning the cause of COPD. Although we did not ask participants about their medication, all of them talked about positive experiences with their regular or rescue medication, as well as recovery by hospital care after an acute crisis. The use of physiotherapy and oxygen were seen as helpful interventions; none of them had serious therapy-related complaints. This conveyed the feeling of being healthy or at least not seriously ill. Even oxygen, if required, was adapted to everyday actions. However, the medical advancements support the patients' need to maintain normal life for a long time. Since they rate their own health status on the basis of daily activities, patients denied the severity of the disease by accepting changes in their daily life and nevertheless evaluating their daily life as ‘normal’.

Well, everything got a bit slower and, naturally //mmm// the stairs also got harder to climb, the garden no longer got dug in two hours either, I needed a bit longer for it //mmm// it was all normal…(CO-01w, female, 71 years)

Physicians obviously confront their patients with the fact that smoking is the main cause for developing COPD. Hence, patients who were smokers felt especially responsible for their current health status, which is experienced as a tremendous psychological burden that must be played down or disproved by the patients. During the interviews, participants stated their own disease concepts and explanations (eg, severe bronchitis in their childhood) or other causes (eg, toxic exposure in their jobs).

Naw, I think=I, I=don't have asthma, the weather doesn't bother me at all //mmm// instead the lack of air, the lung //mmm// is so restricted by the scars from my childhood //mmm// em, so that=it just can't be managed anymore…(CO-09m, male, 78 years)

And then I thought you're stupid, you should have worked with a mask or something […] and that was, that was the reason I imagine, so it was all the dust I breathe in […] it's just the same with asphalt, I drove on asphalt, now the next slump comes from driving on asphalt, so whenever I buggered up I got something serious, eh //mmm// it's just the same when you spend 10 hours on the machine and you breathe in all the vapours all the time, it's clear that that can't be healthy […] but this government says or its trade association says it's smoking, the doctor says that too, ‘cause it's a good excuse…(CO-07m, male, 54 years)

However, it seems that the possibility to maintain a daily routine enables patients to deny or at least to weaken their responsibility for the cause of the disease.

Deny the threat to life for as long as possible

As a consequence of patients' attempts to continue daily life as usual, they aim to deny the threat to life for as long as possible. The fact that the COPD trajectory is characterised by sporadic serious episodes followed by recovery to just a little below the previous health status makes it easier to deny the degree and progress of the disease.

You forget the disease, when you feel so well…(CO-1w, female, 71 years)

In the postcrisis situation, patients continue to hope that they will reach at least the health status they had before the crisis, for example, to go to the toilet or to climb stairs without help, to go for a long walk, or to go on holidays, depending on the individual disease progress. The fact of gradual aggravation, that is, limited mobility, physical complaints, the necessity of daily support, or the need for affection and attention, in turn facilitates the slowness of perceiving and accepting the threat of the disease. It seems as if a serious crisis is needed to face one's own health situation and the illness progress, which was phrased by the informants as reaching one's own limits, or ‘nothing more’ being ‘possible’.

At first I didn't take any of it all that seriously ((sniffles)) (3) until last year, when nothing more was possible…(CO-03m, male, 60 years)

Against this background, talking about PC was experienced as talking about a speedy end to life and thus strongly rejected by patients, whereby experiences were extremely heterogeneous. It seems that interim clinical PC was either not addressed by physicians or even communicated with negative advice. Patients showed a negative attitude, as they compared PC with hospice care, thus assuming sudden death.

IP: I got wise to that only when I was lying there that they just leave us lying there and then when I saw the file with Palliative it all became clear because that's just how they were acting.

I: so what became clear?

IP: that I had only been sent there to die…(CO-09m, male, 78 years)

And then he came [the doctor] (here with palliative) and he said if I wanted his advice I should stay with my wife for as long as possible . in terms of life or in terms of help . as soon as a third person [a health carer] joins in- and that's why these tablets- I was prescribed them […] and I still have the tablets and she said Mr L. as soon as you notice that you are feeling better […] then we can first reduce them and then cease them and my fear is that if I go down that route that I will need outside help […] but palliative care is the last path or the last step before death…(CO-02m, male, 72 years)

However, the only patient who had previously received PC told of very positive experiences.

And palliative service- they are still coming around they came just yesterday- […] and asked if anything was wrong and look after me well I must say […] I can always talk about my distress and my worries then and they have- somehow they always have a good idea, and then it works- it [the washbasin] is placed in the bed and that works out really well…(CO-01w, female, 71 years)

Limited opportunity for action and social isolation

The increasing breathlessness and subsequent need for oxygen generates a feeling of being at the mercy of the disease and at least of one's own body, as it limits the opportunity for action. From the time when oxygen is needed, it determines movements with increasing restriction; initially, movements outside the home are affected; subsequently, movements at home also are determined by oxygen supply.

I can't do anything anymore I have a- now from the hospital I now have a wheelchair (2) bu- of course I don't use it, I certainly don't use it here in the village because I don't go around there at all now anymore I never did so if if we go anywhere we drive somewhere else […] (2) few kilometres with the car […] where I can pack my oxygen device in my wheelchair”…(CO-05w, female, 57 years)

So the spontaneity to simply say […] let's just go away for the weekend no it all has to be organised the oxygen has to be organised and there's a whole slew of other things that we have to take with us […] and=and=and all sorts of things (2) yes, the=restrictions to the quality of life in some cases I can't even take part in family celebrations…(CO-28w, female, 58 years)

On this basis, social isolation increases. Former activities with friends are no longer possible, the consequence being that either friends, or the patients themselves, withdraw from sociality. Some of them feel stigmatised because of the visibility of the disease and the helpless reaction of their environment.

As long as patients do not need permanent oxygen, driving seems to be the only possibility to go outside at all. Once they need oxygen, the oxygen tank limits the time frame, so that driving must be planned precisely. From that date, daily activities such as going to the hairdresser, shopping for daily necessities, or seeing the doctor are difficult to realise, if at all.

Discussion

This study explores the perspectives and needs of patients suffering from progressive COPD, and therefore provides new insights into details of the relevant subject of end-of-life care. Using a narrative approach for data collection and analysis, with a main focus on gathering and analysing the unaffected patient perspective, it was possible to reconstruct the individual experiences given in the interviews. This was possible because the informants were willing to talk frankly and in detail about their life and feelings during the inquiry period. Recruitment turned out to be more difficult than anticipated. Although all participants met the inclusion criteria, the range of physical distress was rather heterogeneous. However, this gave us the possibility to better understand illness experiences at an earlier stage of advanced COPD. Thus, for example, the relevance and connection of mobility and social isolation could be described as a relevant context that has an increasing influence on the core illness experience (being at the mercy of the disease) and the resulting action strategy (try to maintain daily life as usual) over time. By conducting most of the interviews at the participants' homes, they also afforded an insight into their home and life situation, a valuable addition for data analysis, as it enriched the material and enabled a better understanding of the data collected. Study results are based on a sample of patients living in the middle of Germany. Therefore, patients' experiences in other German regions might be different in some aspects.

The study shows that patients with advanced COPD find it difficult to accept their life-threatening situation and feel at the mercy of the disease (core-experienced phenomenon). Over a long period of time, patients have only a vague feeling of being ill, which is caused by uncertain knowledge, slow progress and the doubtful attribution of clinical symptoms of the disease, for example, shortness of breath, acute crisis (causal conditions). As an action strategy, patients try to maintain daily life for as long as possible compared with the time before diagnosis. Both effective medication, which helps to reduce breathlessness, and the feeling of being faced with one's own responsibility for the cause of the illness (intervening conditions) support this strategy, whereby the second is too painful to acknowledge. As a consequence, patients try to deny the threat to life for a long period of time. They often need the experience of facing their own limits to realise their health situation. The illness experience is contextualised by a continuous increase of limited opportunity for action and social isolation.

According to the patients' experiences, current medical COPD standard treatment and rescue medication appears to be appropriate and realisable in daily life and, as a result, from the patients' perspective there seems to be no need to improve existing therapies. Moreover, the high degree of effectiveness experienced enables patients to maintain daily life and work-related as well as social participation over a long period of time, with only moderate aggravation, until a sudden turning point of physical inability. COPD is defined as ‘a preventable and treatable disease with some significant extrapulmonary effects that may contribute to the severity in individual patients’.4 Together with the effective medication experienced, in particular the preventable and treatable aspects of COPD given in this definition might hinder patients' instant acceptance of the disease as a severe and life-limiting condition. Instead, it may foster patients' questions about the individual cause of the disease and lead to patients developing their own disease concepts. In line with the findings of our study, Disler et al29 showed that at the progressive stage of the disease, patients feel both increasing physical burden and social isolation, which are known as the basis for decreasing psychological and social well-being. Social isolation that contextualises illness experiences as a main aspect is a result of shameful breathlessness, as described by Gysels and Higginson,30 as well as also of the reduced range of motion, which in turn depends on the range of portable oxygen tanks and their low practicability. As is known, the illness progress is very slow and characterised by gradual decline,5 31 which means that the changing health situation can be adapted into daily routines for many years.

Although none of the participants believe that he or she will recover, this might be a reason why it is difficult for current patients at a progressive stage to face the life-limiting aspect of COPD. However, living with advanced COPD means being confronted with tremendous limitations regarding the health-related quality of life. Findings strongly suggest that patients may benefit from the early integration of PC as usual practice. The WHO defines PC as ‘an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual’.32 Among others, PC integrates ‘the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care’, ‘uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families’, and ‘will enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness’.33 With regard to the findings of this study, this means that the patient-centred and team-centred approaches could help to better inform patients about the progress of the disease, which data show to be lacking. It might further help to better understand and accept the life situation, and the resulting feeling of a hopeless situation, described in our findings as the feeling of being at the mercy of the disease. Psychosocial support could help to solve the question of responsibility and may influence the patients' action strategies in a positive manner, that is, to try to live daily life in accordance with their physical capacities. As shown in a review by Burbeck et al,34 in some cases, for example, the loss of social life and/or isolation, volunteer work, which is a relevant aspect of psychosocial support in PC, may be sufficient to compensate these needs and may mediate between patient and doctors, carers or therapists. It must be assumed that support from volunteers, as an aspect of early integration, might enhance or maintain psychosocial well-being (eg, reducing isolation), and perhaps also physical well-being (eg, reducing symptoms) as aspects of quality of life. The experiences of our study suggest that the possibility to talk to a non-medical person about one's own concerns (in an interview) may already strengthen this aspect. We know from the literature that volunteers carry out various activities, such as giving emotional care to patients and their families, sharing a hobby, or assisting with social outings.35 It has been shown that their work may have a positive impact on relatives' well-being 36 and that terminally ill patients who received volunteer support had a prolonged survival.37 The fact that volunteers define their role in social terms suggests a possibility to form relationships with respect to individual needs.34 Against this background, it seems reasonable to assume that volunteers might further help patients to accept their life situation, the disease progress and the incurability of the disease without them necessarily having to see professionals (social worker, psychologist).

Conclusion

Early integration of PC in the case of COPD might imply providing support after a severe turning point within the course of the disease, which must be identified individually. Further research is needed to evaluate how patients could benefit from the early integration of PC in general, and from volunteer work in particular.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating patients for being part of the study and for talking frankly about their experiences and feelings. Further, the authors would like to thank Marie-Luise Dierks for her methodical advice in the proposal, as well as Tobias Welte and Carl-Peter Criée for facilitating field access to the patients. We acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University.

Footnotes

Contributors: NS (director of the department of general practice, Hannover Medical School) was principal investigator of the study and led the study design and supervised the research process. FN (director of the department of palliative medicine, University Medical Center Göttingen) was co-investigator of the study and co-designed the study. GM (PhD, research associate) and HS (Dip, research associate) prepared the interview guide, recruitment and data collection. GM and MN (doctoral candidate) interviewed the participants. GM, MN, HS and SOB (MA, research associate) conducted the analysis and repeatedly discussed the findings. GM wrote the first draft. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Culture in Lower Saxony, Germany, grant number 74ZN1079.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study received approval from the Ethics Committees of Hannover Medical School (registration number 5896) and University Medical Centre Göttingen (registration number 19/11/12).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.WHO . Burden of COPD. Chronic respiratory diseases. (cited 5 January 2015). http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/

- 2. Sterbefälle insgesamt 2011 nach den 10 häufigsten Todesursachen der ICD-10 2011 [Mortality 2011]. (cited 27 February 2014). https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesellschaftStaat/Gesundheit/Todesursachen/Tabellen/SterbefaelleInsgesamt.html.

- 3.Vogelmeier C, Buhl R, Criée C et al. Leitlinie der Deutschen Atemwegsliga und der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Pneumologie und Beatmungsmedizin zur Diagnostik und Therapie von Patienten mit chronisch obstruktiver Bronchitis und Lungenemphysem (COPD). Pneumologie 2007;61:e1–40. 10.1055/s-2007-959200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.2010. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. . http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLDReport_April112011.pdf.

- 5.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007–11. 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M et al. Individual breathlessness trajectories do not match summary trajectories in advanced cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from a longitudinal study. Palliat Med 2010;24:777–86. 10.1177/0269216310378785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giacomini M, DeJean D, Simeonov D et al. Experiences of living and dying with COPD: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 2012;12:1–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinnock H, Kendall M, Murray SA et al. Living and dying with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: multi-perspective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 2011;342:d142 10.1136/bmj.d142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsiligianni I, Kocks J, Tzanakis N et al. Factors that influence disease-specific quality of life or health status in patients with COPD: a review and meta-analysis of Pearson correlations. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20:257 10.4104/pcrj.2011.00029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saltnes SS, Storhaug K, Borge CR et al. Oral health-related quality-of-life and mental health in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Acta Odontol Scand 2015;73:14–20. 10.3109/00016357.2014.935952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gärtner J, Simon S, Voltz R. Palliativmedizin und fortgeschrittene, nicht heilbare Erkrankungen. Internist 2011;52:20–7. 10.1007/s00108-010-2690-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gore JM, Brophy CJ, Greenstone MA. How well do we care for patients with end stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)? A comparison of palliative care and quality of life in COPD and lung cancer. Thorax 55:1000–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edmonds P, Karlsen S, Khan S et al. A comparison of the palliative care needs of patients dying from chronic respiratory diseases and lung cancer. Palliat Med 2001;15:287–95. 10.1191/026921601678320278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habraken JM, van der Wal WM, ter Riet G et al. Health-related quality of life and functional status in end-stage COPD: a longitudinal study. Eur Respir J 2011;37:280–8. 10.1183/09031936.00149309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gysels MH, Higginson IJ. The lived experience of breathlessness and its implications for care: a qualitative comparison in cancer, COPD, heart failure and MND. BMC Palliat Care 2011;10:15 10.1186/1472-684X-10-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weingaertner V, Scheve C, Gerdes V et al. Breathlessness, functional status, distress and palliative care needs over time in patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or lung cancer: a cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:569–81.e1. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gysels M, Higginson IJ. The experience of breathlessness: the social course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:555–63. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M et al. Understanding breathlessness: cross-sectional comparison of symptom burden and palliative care needs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1109–18. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodridge D, Lawson J, Duggleby W et al. Health care utilization of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer in the last 12 months of life. Respir Med 2008;102:885–91. 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marx G, Stanze H, Nauck F, Schneider N. Understanding the Needs and Perspectives of Patients with Incurable Pulmonary Disease at the End of Life and their Relatives: Protocol of a Qualitative Longitudinal Study. J Palliat Care Med 2014;4:177. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine Pub., 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Grounded theory research: procedures, canons and evaluative criteria. ZfS 1990;19:418–27. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mruck K, Mey G. Grounded theory and reflexivity. In: Bryant A, Charmaz K, Eds. The sage handbook of grounded theory London: Sage, 2010:487–510. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker C, Wuest J, Stern PN. Method slurring: the grounded theory/phenomenology example. J Adv Nurs 1992;17:1355–60. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01859.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reichertz J. Abduction: the logic of discovery of grounded theory. Forum Qual Soc Res 2010;11:Art. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Weiterleben lernen: Verlauf und Bewältigung chronischer Krankheit. Bern: Huber, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelle U. “Emergence” vs. “forcing” of empirical data? A crucial problem of “grounded theory” reconsidered. Forum Qual Soc Res 2005 revised 2012;6:Art. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Disler RT, Currow DC, Phillips JL et al. Interventions to support a palliative care approach in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:1443–58. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Access to services for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the invisibility of breathlessness. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;36:451–60. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA 2003;289:2387–92. 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall S. World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Palliative care for older people: better practices. Copenhagen: World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization . WHO Definition of Palliative Care. (cited 17 June 2016). http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- 34.Burbeck R, Candy B, Low J et al. Understanding the role of the volunteer in specialist palliative care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:3 10.1186/1472-684X-13-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burbeck R, Low J, Sampson EL et al. Volunteers in specialist palliative care: a survey of adult services in the United Kingdom. J Palliat Med 2014;17:568–74. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weeks LE, Macquarrie C, Bryanton O. Hospice palliative care volunteers: a unique care link. J Palliat Care 2008;24:85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herbst-Damm KL, Kulik JA. Volunteer support, marital status, and the survival times of terminally ill patients. Health Psychol 2005;24:225–9. 10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011555supp1.pdf (13.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-011555supp2.pdf (69.5KB, pdf)