Abstract

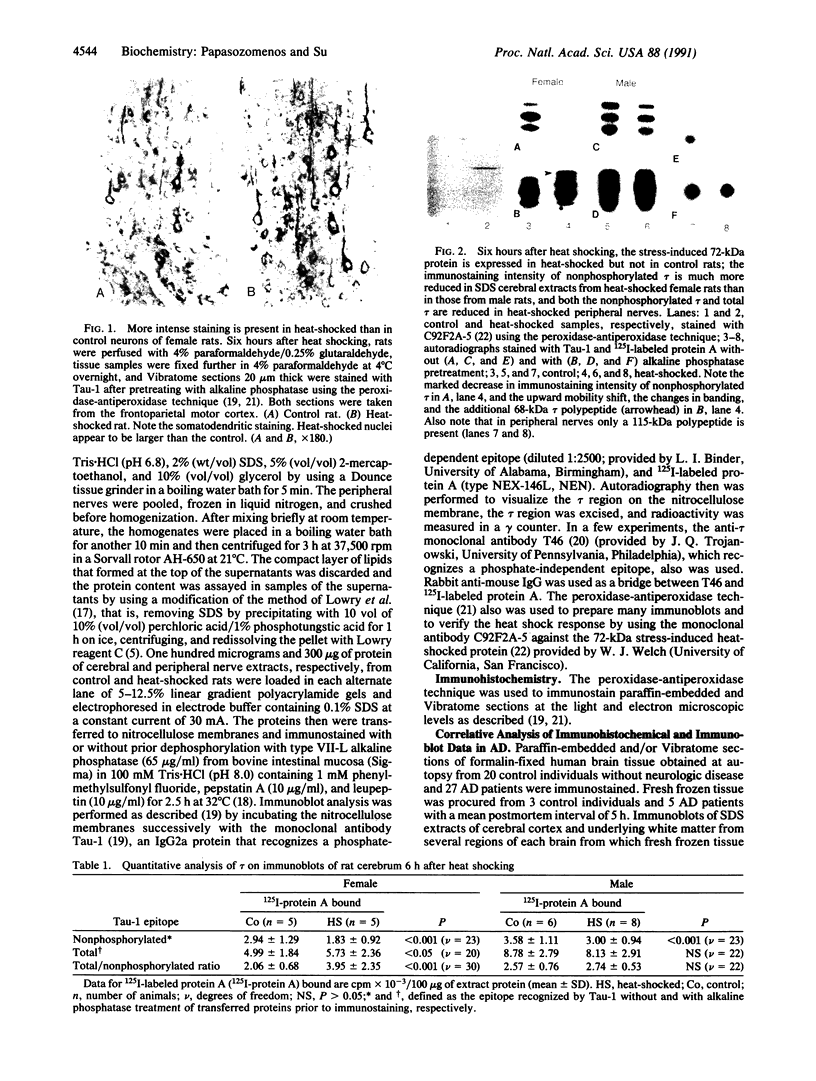

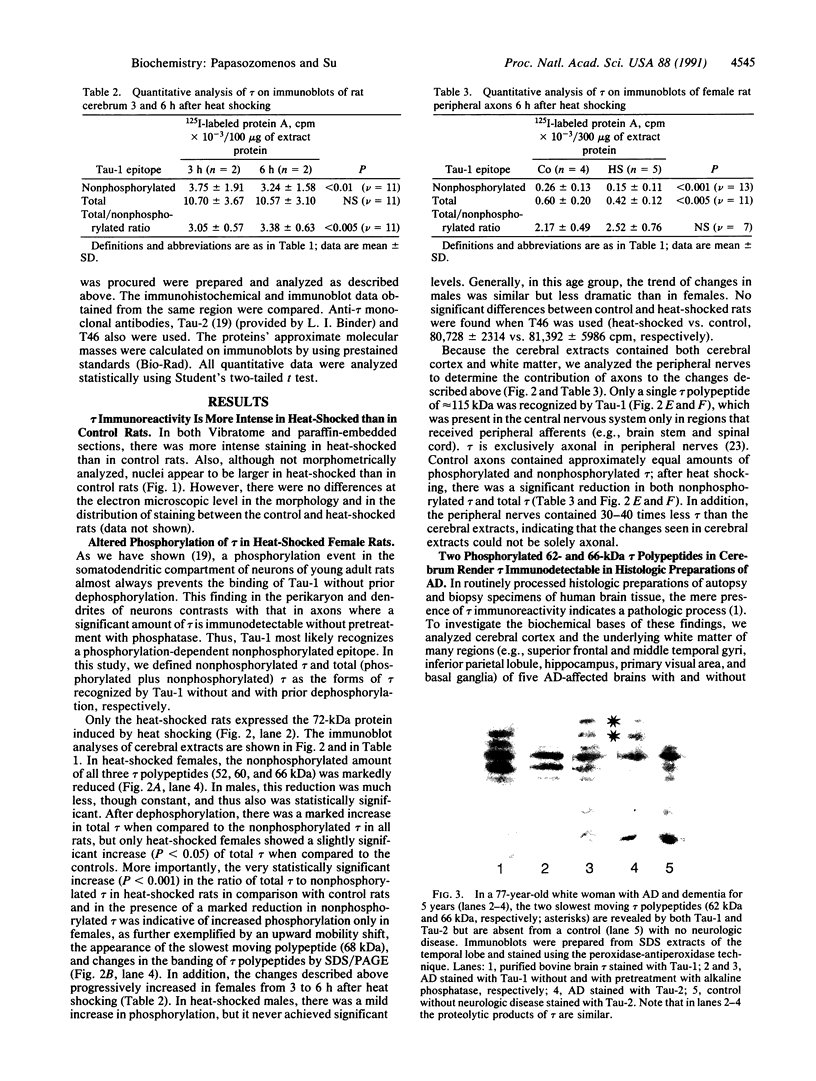

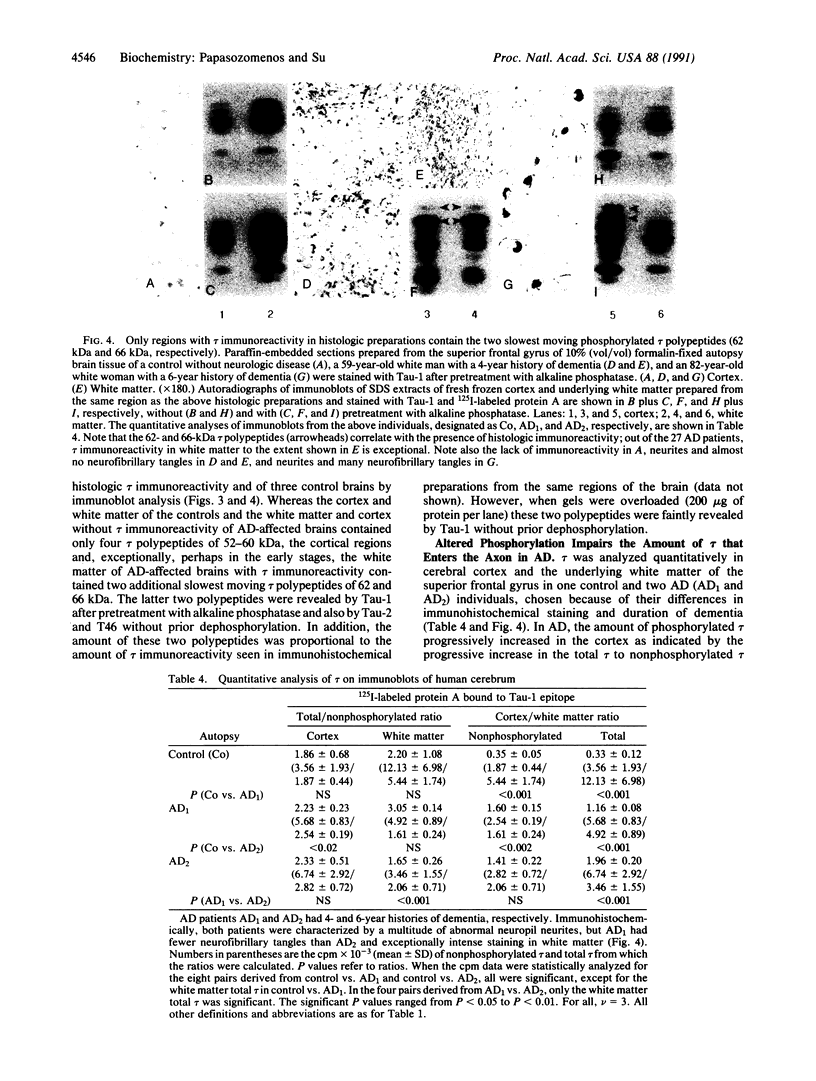

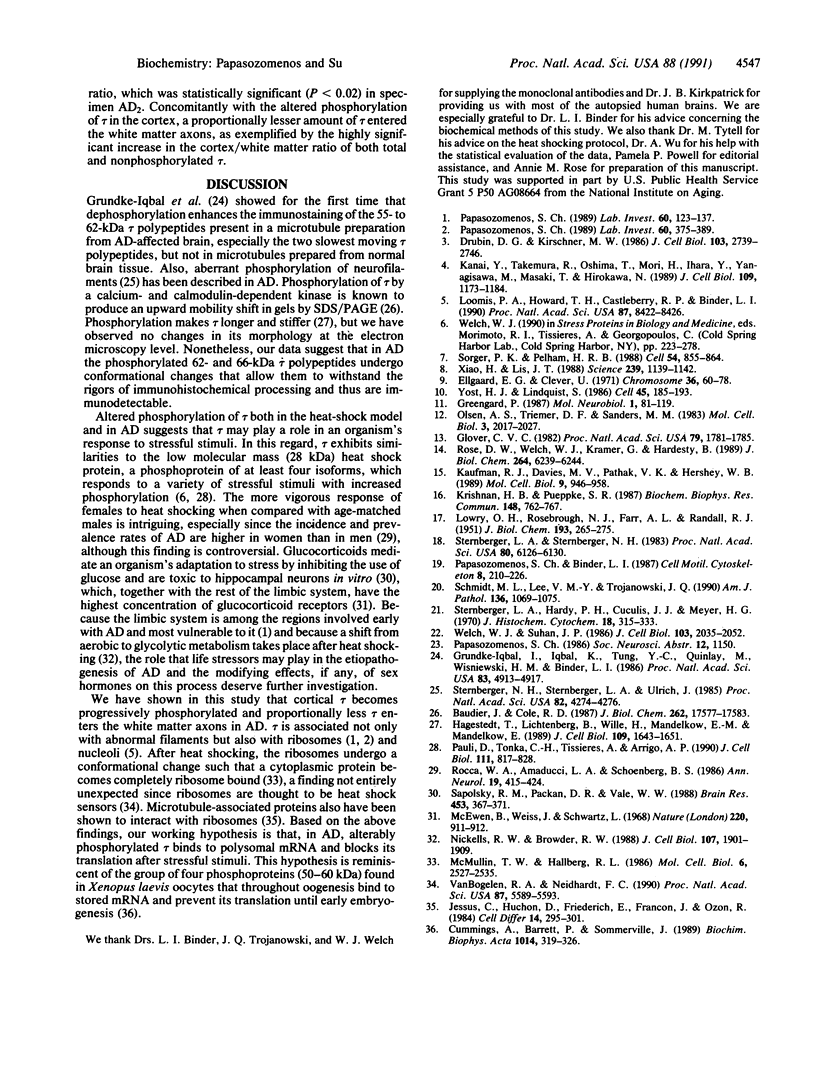

Six hours after heat shocking 2- to 3-month-old male and female Sprague-Dawley rats at 42 degrees C for 15 min, we analyzed tau protein immunoreactivity in SDS extracts of cerebrums and peripheral nerves by using immunoblot analysis and immunohistochemistry with the anti-tau monoclonal antibody Tau-1, which recognizes a phosphate-dependent non-phosphorylated epitope, and with 125I-labeled protein A. In the cerebral extracts, we found altered phosphorylation of tau in heat-shocked females, characterized by a marked reduction in the amount of nonphosphorylated tau, a doubling of the ratio of total (phosphorylated plus nonphosphorylated) tau to nonphosphorylated tau, and the appearance of the slowest moving phosphorylated tau polypeptide (68 kDa). Similar, but milder, changes were observed in male rats. These changes progressively increased in females from 3 to 6 h after heat shocking. In contrast, both phosphorylated tau and nonphosphorylated tau were reduced in peripheral nerves after heat shocking. In immunoblots of SDS extracts from Alzheimer disease-affected brain, the two slowest moving phosphorylated tau polypeptides (62 kDa and 66 kDa, respectively) were detected by Tau-1 after dephosphorylation and by Tau-2 (an anti-tau-monoclonal antibody that recognizes a phosphate-independent epitope) without prior dephosphorylation only in regions that contained tau immunoreactivity in histologic preparations. In addition, quantitative immunoblot analysis of cortex and the underlying white matter with Tau-1 and 125I-labeled protein A showed that the amount of phosphorylated tau progressively increased in the Alzheimer disease-affected cerebral cortex, while concurrently a proportionally lesser amount of tau entered the white matter axons. The similar findings for the rat heat-shock model and Alzheimer disease suggest that life stressors may play a role in the etiopathogenesis of Alzheimer disease.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baudier J., Cole R. D. Phosphorylation of tau proteins to a state like that in Alzheimer's brain is catalyzed by a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase and modulated by phospholipids. J Biol Chem. 1987 Dec 25;262(36):17577–17583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings A., Barrett P., Sommerville J. Multiple modifications in the phosphoproteins bound to stored messenger RNA in Xenopus oocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989 Dec 14;1014(3):319–326. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(89)90229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drubin D. G., Kirschner M. W. Tau protein function in living cells. J Cell Biol. 1986 Dec;103(6 Pt 2):2739–2746. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard E. G., Clever U. RNA metabolism during puff induction in Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma. 1971;36(1):60–78. doi: 10.1007/BF00326422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover C. V. Heat shock induces rapid dephosphorylation of a ribosomal protein in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Mar;79(6):1781–1785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greengard P. Neuronal phosphoproteins. Mediators of signal transduction. Mol Neurobiol. 1987 Spring-Summer;1(1-2):81–119. doi: 10.1007/BF02935265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Tung Y. C., Quinlan M., Wisniewski H. M., Binder L. I. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jul;83(13):4913–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagestedt T., Lichtenberg B., Wille H., Mandelkow E. M., Mandelkow E. Tau protein becomes long and stiff upon phosphorylation: correlation between paracrystalline structure and degree of phosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 1989 Oct;109(4 Pt 1):1643–1651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessus C., Huchon D., Friederich E., Francon J., Ozon R. Interaction between rat brain microtubule associated proteins (MAPs) and free ribosomes from Xenopus oocyte: a possible mechanism for the in ovo distribution of MAPs. Cell Differ. 1984 Oct;14(4):295–301. doi: 10.1016/0045-6039(84)90018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y., Takemura R., Oshima T., Mori H., Ihara Y., Yanagisawa M., Masaki T., Hirokawa N. Expression of multiple tau isoforms and microtubule bundle formation in fibroblasts transfected with a single tau cDNA. J Cell Biol. 1989 Sep;109(3):1173–1184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.3.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman R. J., Davies M. V., Pathak V. K., Hershey J. W. The phosphorylation state of eucaryotic initiation factor 2 alters translational efficiency of specific mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Mar;9(3):946–958. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan H. B., Pueppke S. G. Heat shock triggers rapid protein phosphorylation in soybean seedings. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987 Oct 29;148(2):762–767. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90941-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis P. A., Howard T. H., Castleberry R. P., Binder L. I. Identification of nuclear tau isoforms in human neuroblastoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Nov;87(21):8422–8426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S., Weiss J. M., Schwartz L. S. Selective retention of corticosterone by limbic structures in rat brain. Nature. 1968 Nov 30;220(5170):911–912. doi: 10.1038/220911a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullin T. W., Hallberg R. L. Effect of heat shock on ribosome structure: appearance of a new ribosome-associated protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jul;6(7):2527–2535. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickells R. W., Browder L. W. A role for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the development of thermotolerance in Xenopus laevis embryos. J Cell Biol. 1988 Nov;107(5):1901–1909. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen A. S., Triemer D. F., Sanders M. M. Dephosphorylation of S6 and expression of the heat shock response in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 1983 Nov;3(11):2017–2027. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.11.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasozomenos S. C., Binder L. I. Phosphorylation determines two distinct species of Tau in the central nervous system. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1987;8(3):210–226. doi: 10.1002/cm.970080303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasozomenos S. C. Tau protein immunoreactivity in dementia of the Alzheimer type: II. Electron microscopy and pathogenetic implications. Effects of fixation on the morphology of the Alzheimer's abnormal filaments. Lab Invest. 1989 Mar;60(3):375–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli D., Tonka C. H., Tissieres A., Arrigo A. P. Tissue-specific expression of the heat shock protein HSP27 during Drosophila melanogaster development. J Cell Biol. 1990 Sep;111(3):817–828. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca W. A., Amaducci L. A., Schoenberg B. S. Epidemiology of clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1986 May;19(5):415–424. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D. W., Welch W. J., Kramer G., Hardesty B. Possible involvement of the 90-kDa heat shock protein in the regulation of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1989 Apr 15;264(11):6239–6244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky R. M., Packan D. R., Vale W. W. Glucocorticoid toxicity in the hippocampus: in vitro demonstration. Brain Res. 1988 Jun 21;453(1-2):367–371. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M. L., Lee V. M., Trojanowski J. Q. Relative abundance of tau and neurofilament epitopes in hippocampal neurofibrillary tangles. Am J Pathol. 1990 May;136(5):1069–1075. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorger P. K., Pelham H. R. Yeast heat shock factor is an essential DNA-binding protein that exhibits temperature-dependent phosphorylation. Cell. 1988 Sep 9;54(6):855–864. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberger L. A., Hardy P. H., Jr, Cuculis J. J., Meyer H. G. The unlabeled antibody enzyme method of immunohistochemistry: preparation and properties of soluble antigen-antibody complex (horseradish peroxidase-antihorseradish peroxidase) and its use in identification of spirochetes. J Histochem Cytochem. 1970 May;18(5):315–333. doi: 10.1177/18.5.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberger L. A., Sternberger N. H. Monoclonal antibodies distinguish phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated forms of neurofilaments in situ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Oct;80(19):6126–6130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.19.6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberger N. H., Sternberger L. A., Ulrich J. Aberrant neurofilament phosphorylation in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jun;82(12):4274–4276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanBogelen R. A., Neidhardt F. C. Ribosomes as sensors of heat and cold shock in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Aug;87(15):5589–5593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch W. J., Suhan J. P. Cellular and biochemical events in mammalian cells during and after recovery from physiological stress. J Cell Biol. 1986 Nov;103(5):2035–2052. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.5.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Lis J. T. Germline transformation used to define key features of heat-shock response elements. Science. 1988 Mar 4;239(4844):1139–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.3125608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost H. J., Lindquist S. RNA splicing is interrupted by heat shock and is rescued by heat shock protein synthesis. Cell. 1986 Apr 25;45(2):185–193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90382-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]