Short abstract

The current focus on quality and safety means most doctors have negative views about clinical governance. But done properly, clinical governance has the power to improve NHS performance

Clinical governance has been described as “by far the most high-profile vehicle for securing culture change in the new NHS.”1 However, the government's past preoccupation with delivery and top down performance management has undermined its developmental potential.2 To be effective, clinical governance should reach every level of a healthcare organisation. It requires structures and processes that integrate financial control, service performance, and clinical quality in ways that will engage clinicians and generate service improvements.3 We strongly endorse this view. Because clinicians are at the core of clinical work, they must be at the heart of clinical governance. Recognition of this fact by clinicians, managers, and policy makers is central to re-establishing “responsible autonomy” as a foundation principle in the performance and organisation of clinical work. We look at problems with the prevailing model of clinical governance and describe an alternative approach.

Improving quality from the top down or from the bottom up?

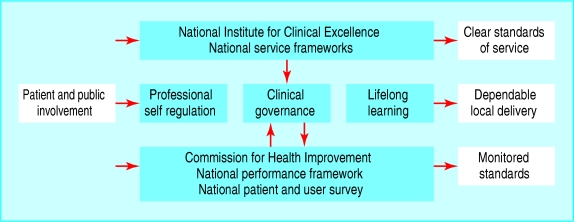

Clinical governance was conceived as being local in both its orientation and in its operation (fig 1). As a bottom-up mechanism, it was intended to inspire and enthuse and create a no-blame learning environment characterised by excellent leadership, highly valued staff, and active partnership between staff and patients.1

Fig 1.

Initial government model of clinical improvement structures4

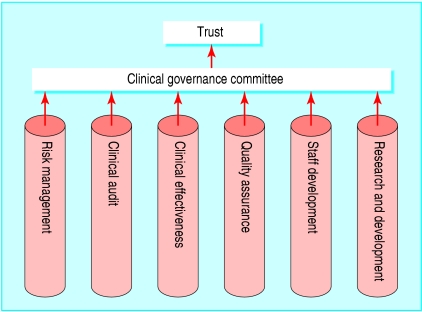

The reality in most trusts, however, is far removed from these high hopes. The clinical governance arrangements established meet the formal requirements of central bodies such as the Commission for Health Improvement (now the Healthcare Commission). They also reflect the government's past emphasis on inspection and performance management.5,6 Hence, in most trusts the operations of the stand alone “silos” (fig 2) are oriented to ensure that a trust's senior management can satisfy its accountability on centrally determined generic performance measures.

Fig 2.

“Silo” organisational structure of clinical governance

Given their focus on abstracted issues such as risk, safety, and quality, the people who staff these silos tend to treat clinical work as an undifferentiated aggregate. This means that they are neither disposed nor equipped to consider the full range of clinical, organisational, and interpersonal processes that are entailed in, for example, treating a fracture or supporting a patient in self managing a chronic disease.

Flawed model

The failure to take account of variations in clinical work has two main effects on clinical governance. Firstly, it is removed from the day to day concerns of clinical staff. For example, clinical governance is incapable of tackling questions such as: “How can we improve our procedures for a normal delivery?” or “how we provide a year of care for a patient with diabetes?” Secondly, by divorcing issues of risk and safety from the specifics of providing care to a nominated patient group, the prevailing model encourages clinicians to view clinical governance as a management driven exercise that has exploded their paperwork to the detriment of patient care.6,7 This perception has resulted in many staff rejecting clinical governance as yet another misconceived attempt by politicians to extend their control over frontline care.6,7

What needs to be done?

If clinical governance is going to work, its developmental focus needs to be strengthened. This requires implementation of a model which recognises clinicians' central role in the design, provision, and improvement of care. The model must also be structured to change how clinical work is conceived, performed, and organised. We therefore need to be clear about what can and needs to be done to encourage and support doctors, nurses, allied health workers, and managers to:

Accept the interconnections between the clinical and resource dimensions of care

Recognise the need to balance clinical autonomy with transparent accountability

Support the systematisation of clinical work

Subscribe to the power sharing implications of more integrated and team based approaches to clinical work and its evaluation.

Alternative model of clinical governance

The self governance of clinical performance and organisation by multidisciplinary teams requires structures and practices that will encourage multidisciplinary teams to engage in conversations that are focused on the detailed composition of care for specific conditions. Such conversations would deal with questions such as:

Are we doing the right things? (Given assessed health needs and existing resource constraints, are we delivering value for money? For common conditions, how appropriate and effective are the services we offer?)

Are we doing things right? (Are we managing clinical performance according to national codes of clinical practice? For common conditions, how systematised are our care processes and how are we performing on risk, safety, quality, patient evaluation, and clinical outcomes?)

Are we keeping up with new developments and what are we doing to extend our capacity to undertake clinical work in these areas? (What strategies are in place for service and professional development for each condition? What are we doing about clinical mentoring, leadership development, and staff appraisal and review?)

Enabling these conversations requires action at the level of both clinical practice and organisational structure. At the practice level, it requires the development and implementation of integrated care pathways for high volume case types—for example, normal deliveries, hip replacements, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. These pathways describe the diagnostic and therapeutic events that will appreciably affect the quality, outcomes, and cost of care. Use of integrated care pathways for systematising care extends the evidence base, strengthens service integration, and improves clinical effectiveness, quality, and technical efficiency as well as patients' satisfaction and clinicians' work experience.8-12

Integrated care pathways are not immutable documents setting out inviolable treatment regimens. Variation remains an expected feature of clinical practice. What is at stake is the learning a clinical team can derive from these variations. When variation occurs, documentation of the variances can become part of structured interprofessional conversations. It is neither realistic nor useful to consider systematising all clinical work. Nevertheless, about half of a hospital's clinical workload is accounted for by a relatively small number of conditions that are amenable to systematisation (box)13.

Patient activity of four NHS trusts in England during 2000-213 categorised into 547 health related groups

30 health related groups accounted for 46% of all emergency inpatient episodes and 39% of all emergency generated bed days

30 groups accounted for 53% of inpatient elective episodes and 47% of elective bed days

30 groups accounted for 75% of day elective episodes

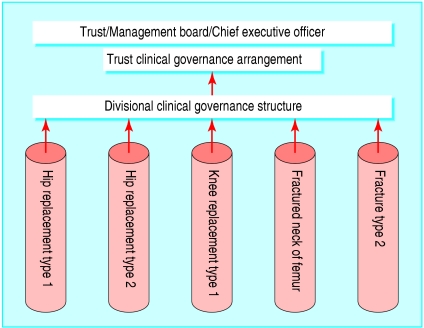

At the level of structure, we need to set in place clinical governance arrangements along the lines depicted in figure 3. In this model, clinical governance becomes a mechanism for encouraging and supporting clinicians in specialist units to systematically and routinely review their unit's performance on its high volume case types. For example, figure 3 depicts an orthopaedics unit reviewing its care for patients with fractured neck of femur. This review would involve surgeons, nurses, rehabilitation physicians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, mental health specialists, and social workers. The same structure could apply in primary care, with each clinical unit (a general practice or community nursing service) reporting on the year of care provided to patients with conditions such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or chronic heart disease. The reports for each clinical condition would include data on evidence, cost, outcomes, clinical effectiveness, quality, safety, adverse events, variance, and complaints.

Fig 3.

Pathway focused clinical governance in acute settings

Where we are and where we want to be

The existing and proposed clinical governance arrangements differ in the processes that each engender and the types of conversations they are structured to produce. In the existing model, the clinical work of the trust is conceived and talked about as an undifferentiated aggregation. Consequently, the detailed composition of clinical work is regarded as something that lies solely within the purview of the clinicians immediately involved. General acceptance of this opaque and ultimately privileged conception of clinical work reinforces the pernicious separation between clinicians and managers that continues to plague too many healthcare organisations.14-17

In contrast, a pathway based model of clinical governance goes beyond the issues that are the focus of risk managers and quality coordinators. Based in a condition-specific conception of clinical work, it invites the people who do the work to define, describe, assess, and manage what they do as teams. It explicitly recognises the centrality of clinicians to the performance and organisation of clinical work and provides clinicians with a medium for integrating the clinical, resource, and organisational aspects of care. In doing so it provides a way for ensuring the responsible autonomy of clinicians. As all professions jointly and routinely enact the methods, structures, and processes outlined above, they will enfold the authority of a system of clinical self governance “into the soul”18 and realise its developmental potential.

Summary points

Clinicians are at the core of clinical work and should also be at the heart of clinical governance

Many trusts' clinical governance arrangements treat clinical work as an undifferentiated aggregate

Failure to take account of the detailed composition of clinicians' work results in their disengagement from management

Integrated care pathways are needed for common (high volume) conditions

A mechanism is required to support all those involved in patient care in systematic evaluation of their overall performance

Contributors and sources: PJD has a disciplinary background of political science, policy studies and health services management. SM has a disciplinary background in health services management and economics. RI has experience in semiotics, linguistics, and organisational studies. DJH's background is political science, policy studies and medical sociology. The paper is based on ideas and concepts developed during research projects on the organisational preconditions for clinical work systematisation conducted over the past 15 years. This paper arose out of meta-level discussions about the findings of several of these projects conducted in Australia, England, and Wales. The chief investigator on all these projects was PJD. SM and RI were co-investigators on several projects. DJH has supported more recent, similar work in the UK by PJD and SM; he acted as a sounding board for the ideas presented.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Leatherman S, Sutherland K. The quest for quality in the NHS: a mid-term evaluation of the ten-year quality agenda. London: Nuffield Trust, 2003.

- 2.Gray A, Harrison S, eds. Governing medicine: theory and practice. Buckingham: Open University Press, 2004. (Chapters 2, 6, 8, 11, 12.)

- 3.Scally G, Donaldson LJ. Looking forward: clinical governance and the drive for quality improvement in the new NHS in England. BMJ 1998;317: 61-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Secretary of State for Health. A first class service. Quality in the new NHS. Leeds: NHS Executive, 1998. www.nhshistory.net/a_first_class_service.htm (accessed 3 Sep 2004).

- 5.Degeling P, Maxwell S, Macbeth F, Kennedy J, Coyle B. The impact of CHI: some evidence from Wales. Qual Primary Care 2003;11: 147-57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degeling P, Macbeth F, Kennedy J, Maxwell S, Coyle B, Telfer B. Professional subcultures and clinical governance implementation in NHS Wales: a report to the National Assembly for Wales. Durham: Centre for Clinical Management Development, University of Durham, and College of Medicine, University of Wales, 2002.

- 7.Degeling P, Kennedy J, Macbeth F, Telfer B, Maxwell S, Coyle B. Practitioner perspectives on objectives and outcomes of clinical governance: some evidence from Wales. In: Gray A, Harrison S, eds. Governing medicine: theory and practice. Buckingham: Open University Press, 2004: 60-77.

- 8.Gregory C, Pope S, Werry D, Dobek P. Reduced length of stay and improved appropriateness of care with a clinical path for total knee or hip arthroplasty. J Qual Improvement 1996;22: 617-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson S. Pathways of care: what and how? J Managed Care 1997;1: 15-7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flynn AM. Case management: a multidisciplinary approach to the evaluation of cost and quality standards. J Nurs Care Qual 1993;1: 58-66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guiliano KK, Poirier CE. Nursing care management: critical pathways to desirable outcomes. Nurs Manage 1991;22: 52-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poole DL. Care profiles, pathways and protocols. Physiotherapy 1994;80: 256-66. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Degeling P, Maxwell S, Kennedy J, Coyle B. Commissioning for performance—but what is the work? An analysis of the commissioning implications of activity data in four health economies in northern England. Public Manage Money (in press).

- 14.Edwards N, Marshall M. Doctors and managers. BMJ 2003;326: 116-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marnoch G. Doctors and management in the National Health Service. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1996.

- 16.Degeling P. Reconsidering clinical accountability. An examination of some dilemmas inherent in efforts to bolster clinician accountability. Int J Health Plann Manage 2000;15: 3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Degeling P, Kennedy J, Hill M. Mediating the cultural boundaries between medicine, nursing and management—the central challenge in hospital reform. Health Serv Manage Res 2001;14: 36-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rose N. Identity, genealogy, history. In: Hall S, du Gay P, eds. Questions of cultural identity. London: Sage, 1996: 128-50.