Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE:

An increasing number of children are born after assisted reproductive technology (ART), and monitoring their long-term health effects is of interest. This study compares cancer risk in children conceived by ART to that in children conceived without.

METHODS:

The Medical Birth Registry of Norway contains individual information on all children born in Norway (including information of ART conceptions). All children born between 1984 and 2011 constituted the study cohort, and cancer data were obtained from the Cancer Registry of Norway. Follow-up started at date of birth and ended on the date of the first cancer diagnosis, death, emigration, or December 31, 2011. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of overall cancer risk between children conceived by ART and those not. Cancer risk was also assessed separately for all childhood cancer types.

RESULTS:

The study cohort comprised 1 628 658 children, of which 25 782 were conceived by ART. Of the total 4554 cancers, 51 occurred in ART-conceived children. Risk of overall cancer was not significantly elevated (HR 1.21; 95% CI 0.90–1.63). However, increased risk of leukemia was observed for children conceived by ART compared with those who were not (HR 1.67; 95% CI 1.02–2.73). Elevated risk of Hodgkin's lymphoma was also found for ART-conceived children (HR 3.63; 95% CI 1.12–11.72), although this was based on small numbers.

CONCLUSIONS:

This population-based cohort study found elevated risks of leukemia and Hodgkin's lymphoma in children conceived by ART.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Several epidemiologic studies concerning fertility treatment and childhood cancer have found no increase in overall cancer risk. However, some studies report elevated risks for individual cancer types, especially for hematologic cancers.

What This Study Adds:

The current study found elevated risks of leukemia in assisted reproductive technology (ART)-conceived children. It contributes data to the existing knowledge on cancer risk in ART offspring, by using a large, complete, nationwide cohort of >25 000 children conceived by ART.

More than 5 million children worldwide have been conceived by assisted reproductive technology (ART),1 and as these children advance into adulthood, monitoring their long-term health effects is important. Several studies have shown that children conceived by ART have increased risks of perinatal complications,2 congenital malformations,3–6 and somatic morbidity.7

Initial case reports of cancer risk in children born after ART concerned hepatoblastomas,8 neuroectodermal tumors,9 and malignant lymphomas.10 It was hypothesized that development of these tumors was influenced by factors related to conception or pregnancy because they are embryonic in type and appear early in life.11,12 In addition, children conceived by ART may have an increased incidence of imprinting disorders,13,14 some of which also are associated with elevated cancer risks.

Several epidemiologic studies concerning fertility treatment and cancer in the offspring have also been conducted, but only 2 have been nationwide and population-based.15,16 A recent meta-analysis, including the first of the 2 studies and several other smaller investigations, found an elevated risk of cancer overall as well as increased risks of several specific cancer types in children conceived by ART,17 in line with other studies reporting elevated risks of overall cancer.15,16 Specifically, some researchers have found increased risks of leukemia,16,18,19 central nervous system (CNS) tumors,20 hepatoblastomas,21 retinoblastomas,22 and neuroblastomas.23 On the other hand, many studies fail to detect an association between ART treatment and childhood cancer risk.24–27 Because childhood cancer is rare, many of the mentioned studies are restricted by few cancer cases. Furthermore, because the use of ART is increasing, many studies are limited by short follow-up time because the majority of children conceived by ART have been born in recent years.

The aim of the current study was to compare cancer risk in children conceived by ART to those conceived without ART, by using a cohort comprising all children born in Norway between 1984 and 2011. The study assessed risk of overall cancer and of specific types of childhood cancer as classified by the International Classification of Childhood Cancer (ICCC), including leukemias and myeloproliferative diseases, lymphomas, CNS neoplasms, neuroblastomas, retinoblastomas, renal tumors, hepatic tumors, malignant bone tumors, soft tissue tumors, and germ cell tumors.

Methods

Study Subjects

The study included all children born in Norway between January 1, 1984, and December 31, 2011. This time period was chosen because 1984 was the first year a child was born after conception by ART in Norway. Cancer risk during childhood and adolescence in ART-conceived individuals was compared with the risk in those conceived without ART.

Setting

Data on all study subjects were extracted from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN). As mandated by Norwegian Legislation, all deliveries in Norway have been registered in the MBRN since 1967, and it comprises information on parental demographics, maternal pregnancy and health, the delivery and postpartum period, and infant perinatal health. As of 1984, all pregnancies initiated by ART have been registered in the MBRN, and by 1988, this registration also became mandatory by Norwegian Legislation.

A unique 11-digit personal identification number (PID) is assigned to all Norwegian inhabitants. The PID provides information on the status (alive at present, dead, emigrated, or missing, as well as the date these events occurred) from theNationalRegistryfor all study subjects.

The PID also enabled linkage with the Cancer Registry of Norway (CRN), which was established in 1952 and contains information on all persons diagnosed with cancer since 1953. The reporting of information on all cancer diagnoses of individuals living in Norway is also mandatory by Norwegian Legislation. Cancer data are reported from several independent sources, which ensures high completeness and validity.28

Follow-up

Study subjects were followed from their date of birth to their first cancer, death, emigration, or December 31, 2011, whichever occurred first. When a study subject had ≥2 cancers of different types, each cancer case was counted separately, once for each diagnostic group. In the analyses of overall cancer, only the first cancer for each individual was counted.

At the time of linkage of the data, the latest complete update of the cancer data was December 31, 2011.

Exposure

ART is defined as “all treatments or procedures that include the in vitro handling of human oocytes and sperm or embryos for the purpose of establishing a pregnancy.”29 In addition to keeping record of all pregnancies initiated by any ART, the MBRN also contains information on which type of ART was used (conventional in vitro fertilization [IVF], intracytoplasmic sperm injection [ICSI], or other forms of treatment [frozen embryo replacement or ART abroad]).

All individuals registered in the MBRN as having been conceived by ART are classified as ART-conceived children, and all those without a registered ART conception as unexposed to ART.

Outcomes

Cancer data for all study subjects were obtained by linkage to the CRN. Cancer diagnoses were classified according to the third version of the ICCC.30 Analyses of cancer risk were made for overall cancer as well as for the 12 main diagnostic groups of the ICCC: leukemias and myeloproliferative diseases (I), lymphomas (II), CNS neoplasms (III), neuroblastomas and other peripheral nervous cell tumors (IV), retinoblastoma (V), renal tumors (VI), hepatic tumors (VII), malignant bone tumors (VIII), soft tissue and other extraosseous sarcomas (IX), and germ cell tumors (X); the last 2 diagnostic groups were considered together: other malignant epithelial neoplasms and malignant melanomas (XI) and other and unspecified malignant neoplasms (XII).

For leukemias, lymphomas, and CNS cancers, subanalyses were made for each of the subgroups in the ICCC classification; for leukemias: acute lymphoid leukemias (ALL; Ia), acute myeloid leukemias (AML; Ib), and other leukemias (Ic–e); for lymphomas: Hodgkin'slymphoma (IIa), non-Hodgkin'slymphoma (IIb), and Burkitt lymphoma (IIc); for CNS cancer: ependymoma (IIIa), astrocytoma (IIIb), embryonal CNS tumors (IIIc), other gliomas (IIId), and other CNS tumors (IIIe and IIIf).

Statistical Analyses

Cox proportional hazards models were used to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk of cancer in children conceived by ART compared with those not conceived by ART. The age of study subjects was used as the time scale. The proportional hazards assumption was met for all but 2 of 11 analytic groups (neuroblastoma, IV; other cancers, IIIe and IIIf). A nonparametric model was used to assess these 2 cancer types, and results were similar. Therefore, the simplest model was applied where proportionality was assumed throughout.

Stratified analyses by method of ART (IVF, ICSI, or other), gender, and maternal age (>30 years versus <30 years) were made for overall cancer risk, leukemia, lymphoma, and CNS tumors.

Estimates for Burkitt lymphoma, malignant bone tumors, and germ cell tumors were not possible because there were no cases in the ART group, and these were therefore omitted from the analyses. The same was done for estimates for 2 subgroups of CNS tumors: ependymoma (IIIa) and other CNS tumors (IIIe).

P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Confounder Adjustment

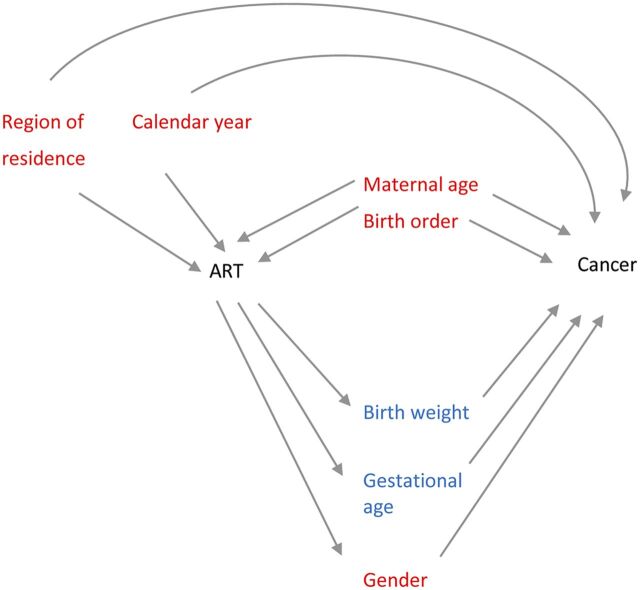

To establish a priori which covariates were potential confounders and which were to be considered intermediates, a directed acyclic graph was constructed using available literature (Fig 1). Two statistical models were constructed. The first, Model I, included variables that were considered confounders: calendar year at follow-up (categorized as 1983–1992, 1993–2002, 2003–2011) and region of residence (Southeast, Southwest, West, Middle, North, and the capital of Oslo separately) were included because they may influence both cancer incidence as well as likeliness of having been conceived by ART. Maternal age has been demonstrated to influence cancer risk in offspring31,32 and is also associated with ART,33 and so was also classified as a confounder (categorized: <25 years, 25–29 years, 30–35 years, and >35 years). Birth order has been shown to be associated with childhood malignancies (particularly low birth order with leukemias),34–36 and children conceived by ART are more likely to be first order, so birth order was included in Model I as a confounder (categorized: 1, 2, 3, and ≥4). Results from Model I are shown in Supplemental Table 4.

FIGURE 1.

A directed acyclic graph showing confounding and mediating factors in the current study associated with ART and childhood cancer. Covariates in red indicate that they have been classified as confounding factors; covariates in blue have been classified as intermediate factors.

Gestational age and birth weight were included in Model II because both have been shown to be associated with risk of childhood cancer, and children conceived by ART are known to have lower gestational age and birth weight than those not conceived by ART.37–39 These two were therefore considered intermediate factors and included in the second model, Model II (gestational length categorized as <24, 25–29, 30–34, and ≥35 weeks and birth weight categorized as <2900 g, 2900–4100 g, and >4100 g). Risk of certain cancers is different among males and females, and therefore gender was included as a covariate in Model II.40 No literature was found that could support an association between being born as a twin or higher-order multiple birth and childhood cancer, and it was therefore not included in the final model.

All analyses were made by using the software package Stata, version 13.0.

The Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, South Eastern Health Region of Norway, approved the study.

Results

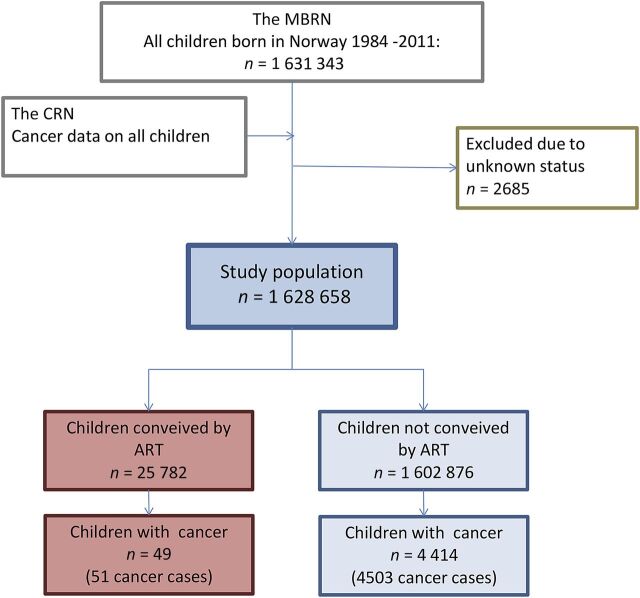

During the observational period, 1 631 343 children were born in Norway, of which 1 628 658 were eligible for study, with the remaining 2685 excluded because of missing data on either status or status date in theNational Registry. In the ART group (n = 25 782), there were 51 cancer cases among 49 study subjects. In the non-ART group (n = 1 602 876), there were 4503 cancer cases among 4414 study subjects (Fig 2). The total follow-up time was 205 529 person-years for the ART group (median 6.9, range 0–27 years) and 21 807 108 for the non-ART group (median 13.7, range 0–28 years; Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Description of the establishment of the study cohort. Children conceived by ART are those registered as conceived by ART in the MBRN; children not conceived by ART are those without a registered ART conception in the MBRN.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

| Characteristics | ART Children | Non-ART Children | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of persons | 25 782 | 1 602 876 | 1 628 658 |

| Persons with cancer, n | 49 | 4414 | 4463 |

| Age at cancer diagnosis, median (IQR) | 3.2 (1.9–7.7) | 8.8 (3.1–17.4) | 8.7 (3.0–17.3) |

| Follow-up time,a median (IQR) | 6.9 (3.1–12.0) | 13.7 (6.5–20.5) | 13.5 (6.5–20.5) |

| Total follow-up time, person-years | 205 529 | 21 807 108 | 22 012 552 |

| Birth year, n (%) | |||

| 1984–1993 | 2097 (8) | 562 833 (35) | 564 930 (35) |

| 1994–2003 | 9313 (36) | 577 093 (36) | 586 406 (36) |

| 2004–2011 | 14 372 (56) | 462 950 (29) | 477 322 (29) |

| Total | 25 782 (100) | 1 602 876 (100) | 1 628 658 (100) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 12 594 (49) | 823 300 (51) | 835 894 (51) |

| Female | 13 188 (51) | 779 576 (49) | 792 764 (49) |

| Total | 25 782 (100) | 1 602 876 (100) | 1 628 658 (100) |

| Multiple or singleton birth, n (%) | |||

| Multiple birth | 8432 (33) | 41 199 (3) | 49 631 (3) |

| Singleton | 17 350 (67) | 1 561 677 (97) | 1 579 027 (97) |

| Total | 25 782 (100) | 1 602 876 (100) | 1 628 658 (100) |

| Birth weight, g, median (IQR) | 3220 (2670–3670) | 3550 (3200–3900) | 3550 (3196–3900) |

| <2900, n (%) | 8739 (34) | 185 896 (12) | 194 635 (12) |

| 2900–4100, n (%) | 14 849 (58) | 1 177 308 (73) | 1 192 157 (73) |

| ≥4100, n (%) | 2167 (8) | 238 188 (15) | 240 355 (15) |

| Missing, n (%) | 27 (0) | 1484 (0) | 1511 (0) |

| Total, n (%) | 25 782 (100) | 1 602 876 (100) | 1 628 658 (100) |

| Gestational length, wk, median (IQR) | 39 (37–40) | 40 (39–41) | 40 (39–41) |

| <24, n (%) | 74 (0) | 642 (0) | 716 (0) |

| 24–30, n (%) | 516 (2) | 7055 (0) | 7571 (0) |

| 30–35, n (%) | 2110 (8) | 31 540 (2) | 33 650 (2) |

| 36–42, n (%) | 19 903 (77) | 1 323 206 (83) | 1 343 109 (82) |

| Over 42, n (%) | 1095 (4) | 158 513 (10) | 159 608 (10) |

| Missing | 2084 (8) | 81 920 (5) | 84 004 (5) |

| Total | 25 782 (100) | 1 602 876 (100) | 1 628 658 (100) |

| Method of ART, n (%) | |||

| Classic IVF | 15 170 (59) | — | — |

| ICSI | 7798 (30) | — | — |

| Other | 188 (1) | — | — |

| Missing | 2626 (10) | — | — |

| Total | 25 782(100) | — | — |

| Maternal age at delivery, median (IQR) | 33.0 (30.0–36.0) | 28.0 (25.0–32.0) | 28.0 (25.0–32.0) |

| <25, n (%) | 409 (2) | 369 653 (23) | 370 062 (23) |

| 25–29, n (%) | 4823 (19) | 563 005 (35) | 567 828 (35) |

| 30–35, n (%) | 11 397 (44) | 457 485 (29) | 468 882 (29) |

| >35, n (%) | 9152 (35) | 212 711 (13) | 221 863 (14) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (0) | 22 (0) | 23 (0) |

| Total, n (%) | 25 782 (100) | 1 602 876 (100) | 1 628 658 (102) |

| Birth order, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 16 792 (65) | 663 704 (41) | 680 496 (42) |

| 2 | 7371 (29) | 569 706 (36) | 577 077 (35) |

| 3 | 1254 (5) | 265 000 (17) | 266 254 (16) |

| 4 | 276 (1) | 72 999 (5) | 73 275 (4) |

| ≥5 | 89 (0) | 31 466 (2) | 31 555 (2) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Total | 25 782 (100) | 1 602 876 (100) | 1 628 658 (100) |

| Age at cancer diagnosis, y, n (%) | |||

| <5 | 29 (64) | 1637 (36) | 1666 (37) |

| 5–10 | 12(26) | 719 (16) | 731 (16) |

| 10–15 | 4 (8) | 598 (13) | 602 (13) |

| 15–20 | 4 (8) | 724 (16) | 728 (16) |

| >20 | 0 (0) | 736 (16) | 736 (16) |

| Total | 49 (106) | 4414 (97) | 4463 (100) |

| Birthplace (Health Region of Norway), n (%) | |||

| Southeast | 8493 (33) | 543 113 (34) | 551 606 (34) |

| Oslo | 3677 (14) | 217 945 (14) | 221 622 (14) |

| Southwest | 4744 (18) | 244 687 (15) | 249 431 (15) |

| West | 4243 (16) | 288 305 (18) | 292 548 (18) |

| Middle | 2700 (10) | 140 730 (9) | 143 430 (9) |

| North | 1917 (7) | 167 037 (10) | 168 954 (10) |

| Missing | 8 (0) | 1059 (0) | 1067 (0) |

| Total | 25 782 (100) | 1 602 876 (100) | 1 628 658 (100) |

ART children are those registered as conceived by ART in the MBRN; non-ART children are those registered as not conceived by ART. IQR, interquartile range.

This is equal to the age of study subjects at end of follow-up or censoring.

More than 50% of children conceived by ART were born between 2004 and 2011, whereas the birth dates of children not conceived by ART were evenly distributed over the 3 time periods 1984–1993, 1994–2003, and 2004–2011 (Table 1). Children conceived by ART had lower median birth weight (3220 g) and gestational age (39 weeks) than those who were not conceived by ART (3550 g and 40 weeks; Table 1). Children conceived by ART had older mothers and were more frequently first-order siblings (Table 1). Of the children conceived by ART, 15 170 were a result of conventional IVF, 7798 of ICSI, and 188 of others treatments; 2626 had missing data on ART method. In children with cancer, median age at diagnosis was 3.2 years (range 0–19.2) for children conceived by ART and 8.8 years (range 0–26.4) for those not conceived by ART (Table 1).

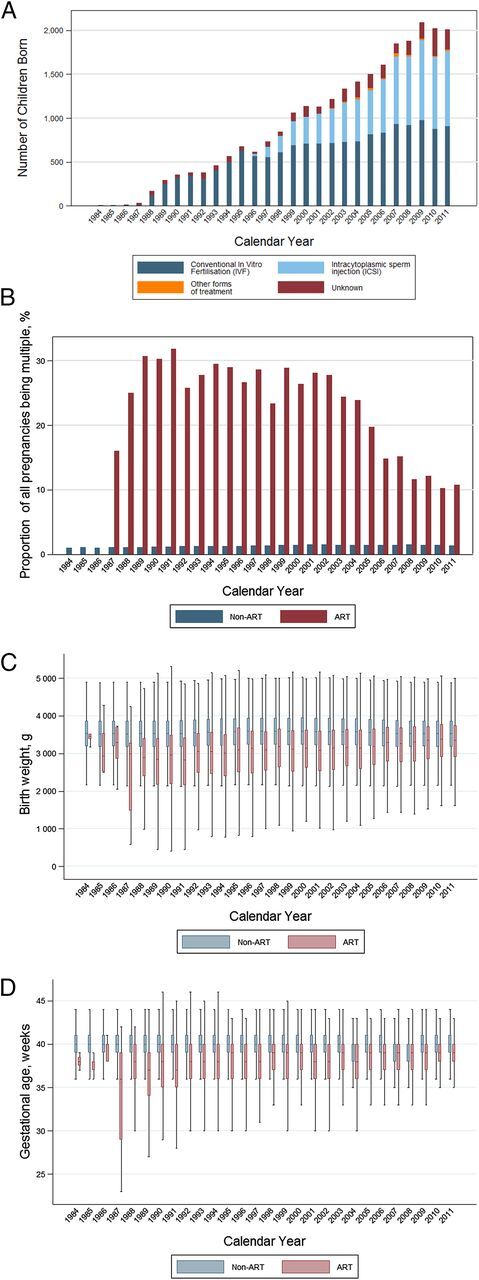

ART children made up an increasing proportion of all annual births and use of ICSI increased during the last decade of the study period(Fig 3A). Children conceived by ART were more often multiples (33% ART children and 3% non-ART children; Fig 3B). Differences in gestational weight and age appeared to lessen throughout the study period, although no significant trends were observed (Fig 3 C and D).

FIGURE 3.

Characteristics of ART offspring compared with non-ART offspring in Norway, changes over 28 years (1984–2011). A, Number of children born after being conceived by ART, by method, each year in Norway, 1984–2011. B, Number of children born as being part of a multiple birth (percent of all pregnancies), by mode of conception in Norway, 1984–2011. C, Birth weight of children born in Norway 1984–2011, by mode of conception and birth year. D, Gestational age of children born in Norway, 1984–2011, by mode of conception and birth year. In panels C and D, the length of the colored intervals indicates the values that lie between the 25th and 75th percentiles. The length of the black lines indicates the range.

The most common cancers were leukemias (33% of all cancers in the ART group and 23% in the non-ART group) and CNS cancers (24% and 23%, respectively; Table 2). Soft tissue tumors were the third most frequent cancer in children conceived by ART (10%), out of which 3 were rhabdomyosarcomas (data not shown). Seven percent (308) of the cancers in the non-ART group were soft tissue tumors (92 rhabdomyosarcomas). Lymphomas were the fourth most common cancer in the ART group, comprising8% of the total tumors, and the third most common cancer in the non-ART group (10%; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of Cancers by Diagnostic Groups in Children Conceived by ART and Children Conceived Without ART, Norway, 1984–2011

| Major Diagnostic Group | ICCC Site Groupa | ART | Non-ART | Total Tumors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Overall cancer | 49 | 4414 | 4463 | |

| Leukemiab | I | 17 (33) | 1021 (23) | 1038 (23) |

| ALL | 1a | 9 (18) | 768 (17) | 777 (17) |

| AML | 1b | 5 (10) | 175 (4) | 180 (4) |

| Other leukemias | 1c–e | 3 (6) | 79 (2) | 81 (2) |

| Lymphoma (all)b | II | 4 (8) | 457 (10) | 461 (10) |

| Hodgkin's | IIa | 3 (6) | 258 (6) | 261 (6) |

| Non-Hodgkin's | IIb | 1 (2) | 147 (3) | 148 (3) |

| Burkitt | IIc | 0 (0) | 52 (1) | 52 (1) |

| CNSb | III | 12 (24) | 1020 (23) | 1032 (23) |

| Ependymoma | IIIa | 0 (0) | 92 (2) | 92 (2) |

| Astrocytoma | IIIb | 5 (12) | 362 (8) | 368 (8) |

| Embryonal CNS | IIIc | 4 (8) | 175 (4) | 179 (4) |

| Other gliomas | IIId | 1 (2) | 104 (2) | 105 (2) |

| Other CNS tumors | IIIe | 0 (0) | 146 (3) | 146 (3) |

| Unspecified CNS tumors | IIIf | 1 (2) | 132 (3) | 133 (3) |

| Neuroblastoma | IV | 4 (8) | 185 (4) | 189 (4) |

| Retinoblastoma | V | 1 (2) | 102 (2) | 103 (2) |

| Renal | VI | 3 (6) | 252 (6) | 255 (6) |

| Hepatic | VII | 2 (4) | 109 (2) | 111 (2) |

| Bone | VIII | 0 (0) | 169 (4) | 169 (4) |

| Soft tissue | IX | 5 (10) | 308 (7) | 313 (7) |

| Germ cell | X | 0 (0) | 387 (9) | 387 (8) |

| Others | XI–XII | 3 (6) | 493 (11) | 496 (11) |

| Totalc | 51 (100) | 4503 (100) | 4554 (100) |

Cancers are classified according to the third version of the ICCC.

In summing up the total number of cancers, each case of leukemia, lymphoma, and CNS cancer is counted only once.

A total of 4554 cancers were diagnosed among the 4473 children with cancer because some children experienced >1 cancer, in different diagnostic groups. Therefore, the total number of cancers by diagnostic group differs from the number of individuals with cancer.

No significant difference in overall cancer risk was found between children conceived by ART and those not conceived by ART (HR 1.21; 95% CI 0.90–1.63; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Risk of Cancer in Children Conceived by ART Compared With Children Conceived Without ART, Norway, 1984–2011

| Cancer Site | ICCC Site Group | Total Number of Tumors | Crude | Model IIa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART | Non-ART | Total | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | ||

| Leukemiab | I | 17 | 1012 | 1029 | 1.52 | 0.94–2.45 | 1.67* | 1.02–2.73 |

| ALL | 1a | 9 | 768 | 777 | 1.03 | 0.53–1.98 | 1.16 | 0.60–2.27 |

| AML | 1b | 5 | 173 | 178 | 2.65* | 1.09–6.46 | 2.63* | 1.04–6.64 |

| Other leukemias | 1c–e | 3 | 71 | 74 | 4.91* | 1.53–15.7 | 5.13* | 1.50–7.60 |

| Lymphomac | II | 4 | 456 | 460 | 1.52 | 0.57–4.08 | 1.79 | 0.66–4.90 |

| Hodgkin's | IIa | 3 | 258 | 261 | 2.62 | 0.84–8.21 | 3.63* | 1.12–11.72 |

| Non-Hodgkin's | IIb | 1 | 147 | 148 | 0.93 | 0.13–6.69 | 0.99 | 0.14–7.28 |

| CNSc | III | 12 | 1007 | 1019 | 1.25 | 0.71–2.21 | 0.92 | 0.47–1.79 |

| Astrocytomas | IIIb | 5 | 362 | 368 | 1.71 | 0.76–3.83 | 1.45 | 0.63–3.29 |

| Embryonal CNS tumors | IIIc | 3 | 175 | 179 | 2.13 | 0.79–5.74 | 1.70 | 0.62–4.69 |

| Other gliomas | IIId | 1 | 104 | 105 | 1.17 | 0.16–8.40 | 1.19 | 0.16–8.80 |

| Other CNS tumors | IIIf | 1 | 132 | 133 | 0.43 | 0.60–3.06 | 0.50 | 0.07–3.59 |

| Neuroblastoma | IV | 4 | 184 | 188 | 1.52 | 0.56–4.08 | 1.79 | 0.64–4.99 |

| Retinoblastoma | V | 1 | 90 | 91 | 0.75 | 0.10–5.38 | — | — |

| Renal | VI | 3 | 251 | 254 | 1.37 | 0.44–4.28 | 1.40 | 0.44–4.48 |

| Hepatic | VII | 2 | 108 | 110 | 2.22 | 0.54–9.07 | 1.76 | 0.41–7.46 |

| Soft tissue | IX | 5 | 307 | 312 | 1.69 | 0.70–4.09 | 1.33 | 0.54–3.30 |

| Others | XI–XII | 3 | 488 | 491 | 1.10 | 0.35–3.44 | 1.21 | 0.38–3.82 |

| All | 49 | 4414 | 4463 | 1.27 | 0.90–1.63 | 1.21 | 0.90–1.63 | |

Cancers are classified by the third version of the ICCC. The proportional hazards assumption was tested with the Schoenfeld residuals.

Adjusted for birth year, birth order, maternal age at delivery, place of birth, gender, birth weight, and gestational age.

In summing up the total number of cancers, each case of lymphoma and leukemia is counted only once.

Analyses for sites with no cancer cases in the ART group were not performed and are therefore omitted from Table 3.

Significant HRs.

Analyses by cancer type revealed an elevated risk of leukemia in children conceived by ART compared with children not conceived by ART (HR 1.67; 95% CI 1.02–2.73), when applying the fully adjusted model (Table 3). Subgroup analyses by type of leukemia showed that the risk was increased for AML (HR 2.63; 95% CI 1.04–6.64) and other leukemias (HR 5.13; 95% CI 1.50–7.60), with no increase noted for ALL (HR 1.16; 95% CI 0.60–2.27). The HR of lymphoma in children conceived by ART compared with non-ART children was 1.79 (95% CI 0.66–4.90). Separate analyses by subgroups of lymphoma revealed a significant increase in risk of Hodgkin's lymphoma in the ART group (HR 3.63; 95% CI 1.12–11.72), based on only 3 cases in the ART group (Table 3).

The risk of CNS cancer was the same for both comparison groups (HR 0.92; 95% CI 0.47–1.79; Table 3). No difference was seen when stratifying on type of CNS tumor (Table 3).

For other cancers, no difference was found between children who were conceived by ART and those who were not (Table 3).

In analyses stratified by ART method, gender, and maternal age, no significant differences between the groups were detected (data not shown).

Discussion

In this population-based study, we have examined cancer risk during childhood and adolescence in individuals conceived by ART compared with those not conceived by ART. Risk of overall cancer was not elevated, but a significantly increased risk of leukemia was seen in children conceived by ART. Furthermore, subgroup analyses indicated significantly elevated risks of AML and Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Overall Cancer

The present finding of no increase in risk of overall cancer in children conceived by ART is in line with recent studies, including a Danish study assessing the association between fertility hormones and childhood cancer,18 a large British study,41 a Nordic collaborative study,20 and a study using data from the Danish infertility cohort.25 Earlier, smaller cohort studies also demonstrated no elevated risk of overall cancer.24,27,42–45 On the other hand, 1 large population-based study from Sweden comprising 26 692 children born after ART found a 42% risk increase for overall cancer in children conceived by ART.15 Although most studies report no risk increase, a recent meta-analysis from 2014 (based on 10 studies) concluded that there was an association between risk of overall cancer and fertility treatment.17

Hematological Cancers

We discovered an elevated risk of leukemia in children conceived by ART compared with those conceived without ART. The finding is consistent with the mentioned meta-analysis,17 as well as the 2 largest cohort studies to date, from Sweden15 and Denmark.18 The Swedish study reported increased numbers of hematologic cancers in a cohort of 26 692 children born after ART (18 observed vs 12.3 expected cases), and the Danish study demonstrated an elevated risk of leukemia (HR 4.96) in children whose mothers were treated with progesterone. Furthermore, 3 case-control studies4,19,46 reported an elevated risk of hematologic cancers among children conceived by ART. On the other hand, several studies report no increased risk of leukemia in children conceived by ART.20,25,26,41 We discovered an elevated risk of AML, although this estimate was based on few cancer cases and must therefore be interpreted with caution. Other researchers have found elevated risks of ALL, a much more common tumor histology in young children.4,19

Studies have assessed the possibility of an association between ART treatment and lymphoma, but no risk increase in children conceived by ART has been found,15,18,20,25,41 in line with our findings. Our observed increased risk of Hodgkin's lymphoma should be interpreted with caution because it was based on few cases and has not been described previously.

CNS Cancer

No elevated risk of CNS cancer was found in our study, in line with a large British study based on a cohort of 106 013 ART-conceived children in the United Kingdom.41 In line with this, a recent meta-analysis that reported an elevated risk of CNS/neural tumors after medically assisted reproduction found no risk increase once CNS tumors were assessed separately from neural tumors.17 However, a Nordic study found an increase in risk of CNS tumors after ART (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.01–2.05), based on 42 cases in the ART group.20 The current study (with only 12 cases of CNS tumors in the ART group) is underpowered to rule out such an increased risk.

Other Cancers

In contrast to 4 case-control studies,22,47–49 we found no increase in risk of retinoblastoma in children conceived by ART. There was only 1 retinoblastoma case in the ART group, but this is consistent with an incidence rate of 0.9 and 0 per 100 000 person-years in the age groups 0 to 4 and 5 to 9 years, respectively.50 Contrary to previous studies,21,41,51,52 we did not find any evidence of increased risks of hepatoblastomas or rhabdomyosarcomas.

Etiology of Childhood Cancers

Few known risk factors exist regarding childhood cancer, although there is some evidence that risks may increase after exposure to ionizing radiation53–55 or diethylstilbestrol.56 Some demographic factors (race, parental occupation, and socioeconomic status)57 and certain parental risk factors (such as advanced parental age) have also been implicated, especially for cancers that arise early in childhood.31,58 A case-control study from the Netherlands found that mothers of children with leukemia were more likely to report “problems with fertility.”59 Hargreave et al found elevated cancer risk in children born to mothers who were infertile and also found an increase in risk associated with progesterone use for infertility.18 Thus, it is difficult to disentangle whether it is the ART treatment, parental infertility, or both that are contributing to observed associations, as also discussed by Hargreave and colleagues.

Strengths and Limitations

The study has a number of strengths, including the fact that we were able to use an entire population of individuals born in 1 country to compare risks between those conceived by ART and those who were not. This, in addition to including all children conceived by ART since the first ART infant was born in Norway, means that the study is larger than most studies previously performed on this topic. The CRN has a high ascertainment of cancers, which enabled complete cancer data and negligible losses to follow-up. The use of a registry-based design allowed for unbiased collection of data about exposure, reducing the possibility of recall bias. Through the MBRN, we were able to obtain data on maternal age and could adjust for this, which is important given that advanced maternal age has been associated with the development of childhood cancers.31 The method of ART used is indicative of the kind of infertility the couple suffers; when male factor infertility is identified, a couple is often selected for ICSI. We were able to look at risk in children conceived by conventional IVF as well as those conceived by IVF with ICSI, which was a strength of our study, although no differences between these 2 groups were detected.

Imprinting disorders have been associated with both ART13,60 and certain cancers (such as hepatoblastoma and kidney tumors in Beckwith-Wiedemann patients)61 and may in the current study be mediating some of the observed effects, which unfortunately could not be measured. Indeed, a study using data from Norway and Sweden found elevated risk of cancer in children with congenital malformations, and the authors suggested that “cancer may be a complication of some birth defects.”62 If parental genetics leads to a couple’s infertility or congenital disorders in the offspring, then maternal and/or paternal genetics would represent a possible confounder that we were unable to account for in our study. Furthermore, although we were able to adjust for maternal age, we could not adjust for the paternal age. As discussed, the current study does not allow for distinction of whether an elevated cancer risk in ART offspring is associated with parental infertility or the processes involved in ART. The use of registry-based data poses a risk of misclassification bias because some children may have been conceived by ART but not registered as ART children in the MBRN. This limitation must be kept in mind because such misclassification is likely nondifferential concerning cancer outcome and may bias the estimates toward the null. Because the ART group is still young, the study may be underpowered to evaluate the risk of cancers arising later in childhood and adolescence. Children conceived by ART in the current study are younger and have shorter follow-up time than the children not conceived by ART, and because leukemia is more common in younger children, it is consequently the most frequent cancer in the ART group. Therefore, as children conceived by ART successively grow older, attention should also be paid to cancers with peak ages above the first few years of life.

Conclusions

The findings in this study, although reassuring for overall cancer, are indicative of an elevated risk of hematologic cancers in children conceived by ART. We observed not only an increased risk of leukemia, but also of Hodgkin's lymphoma.

These findings are in line with most previous studies showing no elevated risk of overall cancer among ART-conceived children but possible increases for certain cancer types. The most frequently noted increases have been hematologic cancers, although other cancers have been highlighted. Keeping in mind that the absolute risk of childhood cancer is low, it must be noted that the 60% increase found in this investigation is a significant increase. Because the children conceived by ART in this cohort are still young, continued observation should be pursued.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the MBRN and the CRN for supplying the data. The interpretation and reporting of the MBRN data are the sole responsibility of the authors, and no endorsement by the MNRB is intended nor should be inferred.

Glossary

- ALL

acute lymphoid leukemia

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- ART

assisted reproductive technology

- CI

confidence interval

- CNS

central nervous system

- CRN

Cancer Registry of Norway

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICCC

International Classification of Childhood Cancer

- ICSI

intracytoplasmic sperm injection

- IVF

in vitro fertilization

- MBRN

Medical Birth Registry of Norway

- PID

personal identification number

Footnotes

Dr Reigstad carried out the data analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Myklebust and Robsahm assisted in the data analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Larsen conceptualized and designed the study, aided in data analyses, and critically reviewed the manuscript; Drs Oldereid and Brinton assisted in study design and critically reviewed the manuscript; Dr Storeng conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised the study, and critically reviewed the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FUNDING: No external funding. Departmental funds were used to support the authors throughout the study period and manuscript preparation, specifically the Oslo University Hospital and the National Cancer Institute.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2015-4509.

References

- 1.Sunderam S, Kissin DM, Crawford S, et al. ; Division of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC . Assisted reproductive technology surveillance—United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62(9):1–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Talaulikar VS, Arulkumaran S. Reproductive outcomes after assisted conception. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67(9):566–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tararbit K, Houyel L, Bonnet D, et al. Risk of congenital heart defects associated with assisted reproductive technologies: a population-based evaluation. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(4):500–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudant J, Amigou A, Orsi L, et al. Fertility treatments, congenital malformations, fetal loss, and childhood acute leukemia: the ESCALE study (SFCE). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(2):301–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayor S. Risk of congenital malformations in children born after assisted reproduction is higher than previously thought. BMJ. 2010;340:c3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen M, Kurinczuk JJ, Milne E, de Klerk N, Bower C. Assisted reproductive technology and birth defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(4):330–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kettner LO, Henriksen TB, Bay B, Ramlau-Hansen CH, Kesmodel US. Assisted reproductive technology and somatic morbidity in childhood: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(3):707–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melamed I, Bujanover Y, Hammer J, Spirer Z. Hepatoblastoma in an infant born to a mother after hormonal treatment for sterility. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(13):820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White L, Giri N, Vowels MR, Lancaster PA. Neuroectodermal tumours in children born after assisted conception. Lancet. 1990;336(8730):1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi N, Matsui I, Tanimura M, et al. Childhood neuroectodermal tumours and malignant lymphoma after maternal ovulation induction. Lancet. 1991;338(8772):955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toren A, Sharon N, Mandel M, et al. Two embryonal cancers after in vitro fertilization. Cancer. 1995;76(11):2372–2374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraumeni JF Jr, Miller RW, Hill JA. Primary carcinoma of the liver in childhood: an epidemiologic study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1968;40(5):1087–1099 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inbar-Feigenberg M, Choufani S, Butcher DT, Roifman M, Weksberg R. Basic concepts of epigenetics. Fertil Steril. 2013;99(3):607–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odom LN, Taylor HS. Environmental induction of the fetal epigenome. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(6):657–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Källén B, Finnström O, Lindam A, Nilsson E, Nygren KG, Olausson PO. Cancer risk in children and young adults conceived by in vitro fertilization. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):270–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hargreave M, Jensen A, Deltour I, Brinton LA, Andersen KK, Kjaer SK. Increased risk for cancer among offspring of women with fertility problems. Int J Cancer. 2013;133(5):1180–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hargreave M, Jensen A, Toender A, Andersen KK, Kjaer SK. Fertility treatment and childhood cancer risk: a systematic meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(1):150–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hargreave M, Jensen A, Nielsen TS, et al. Maternal use of fertility drugs and risk of cancer in children--a nationwide population-based cohort study in Denmark. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(8):1931–1939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petridou ET, Sergentanis TN, Panagopoulou P, et al. In vitro fertilization and risk of childhood leukemia in Greece and Sweden. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(6):930–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundh KJ, Henningsen AK, Källen K, et al. Cancer in children and young adults born after assisted reproductive technology: a Nordic cohort study from the Committee of Nordic ART and Safety (CoNARTaS). Hum Reprod. 2014;29(9):2050–2057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaughlin CC, Baptiste MS, Schymura MJ, Nasca PC, Zdeb MS. Maternal and infant birth characteristics and hepatoblastoma. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(9):818–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marees T, Dommering CJ, Imhof SM, et al. Incidence of retinoblastoma in Dutch children conceived by IVF: an expanded study. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(12):3220–3224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michalek AM, Buck GM, Nasca PC, Freedman AN, Baptiste MS, Mahoney MC. Gravid health status, medication use, and risk of neuroblastoma. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143(10):996–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klip H, Burger CW, de Kraker J, van Leeuwen FE; OMEGA-project group . Risk of cancer in the offspring of women who underwent ovarian stimulation for IVF. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(11):2451–2458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brinton LA, Krüger Kjaer S, Thomsen BL, et al. Childhood tumor risk after treatment with ovulation-stimulating drugs. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(4):1083–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puumala SE, Ross JA, Olshan AF, Robison LL, Smith FO, Spector LG. Reproductive history, infertility treatment, and the risk of acute leukemia in children with down syndrome: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer. 2007;110(9):2067–2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruinsma F, Venn A, Lancaster P, Speirs A, Healy D. Incidence of cancer in children born after in-vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(3):604–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen IK, Småstuen M, Johannesen TB, et al. Data quality at the Cancer Registry of Norway: an overview of comparability, completeness, validity and timeliness. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(7):1218–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, et al. ; International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology; World Health Organization . The International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary on ART terminology, 2009. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(11):2683–2687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Lacour B, Kaatsch P. International Classification of Childhood Cancer, Third Edition. Cancer. 2005;103(7):1457–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson KJ, Carozza SE, Chow EJ, et al. Parental age and risk of childhood cancer: a pooled analysis. Epidemiology. 2009;20(4):475–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson KJ, Soler JT, Puumala SE, Ross JA, Spector LG. Parental and infant characteristics and childhood leukemia in Minnesota. BMC Pediatr. 2008;8:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunson DB, Colombo B, Baird DD. Changes with age in the level and duration of fertility in the menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1399–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dockerty JD, Draper G, Vincent T, Rowan SD, Bunch KJ. Case-control study of parental age, parity and socioeconomic level in relation to childhood cancers. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(6):1428–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schüz J, Luta G, Erdmann F, et al. Birth order and risk of childhood cancer in the Danish birth cohort of 1973–2010. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26(11):1575–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oksuzyan S, Crespi CM, Cockburn M, Mezei G, Kheifets L. Birth weight and other perinatal characteristics and childhood leukemia in California. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(6):e359–e365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Neill KA, Murphy MF, Bunch KJ, et al. Infant birthweight and risk of childhood cancer: international population-based case control studies of 40 000 cases. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(1):153–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sieh W, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K. Perinatal and familial risk factors for brain tumors in childhood through young adulthood. Cancer Res. 2015;75(3):576–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bjørge T, Sørensen HT, Grotmol T, et al. Fetal growth and childhood cancer: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/132/5/e1265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petridou ET, Sergentanis TN, Skalkidou A, et al. Maternal and birth anthropometric characteristics in relation to the risk of childhood lymphomas: a Swedish nationwide cohort study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(6):535–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams CL, Bunch KJ, Stiller CA, et al. Cancer risk among children born after assisted conception. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1819–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ericson A, Nygren KG, Olausson PO, Källén B. Hospital care utilization of infants born after IVF. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(4):929–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bergh T, Ericson A, Hillensjö T, Nygren KG, Wennerholm UB. Deliveries and children born after in-vitro fertilisation in Sweden 1982–95: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 1999;354(9190):1579–1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doyle P, Bunch KJ, Beral V, Draper GJ. Cancer incidence in children conceived with assisted reproduction technology. Lancet. 1998;352(9126):452–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lerner-Geva L, Toren A, Chetrit A, et al. The risk for cancer among children of women who underwent in vitro fertilization. Cancer. 2000;88(12):2845–2847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schüz J, Kaatsch P, Kaletsch U, Meinert R, Michaelis J. Association of childhood cancer with factors related to pregnancy and birth. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(4):631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bradbury BD, Jick H. In vitro fertilization and childhood retinoblastoma. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58(2):209–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foix-L’Hélias L, Aerts I, Marchand L, et al. Are children born after infertility treatment at increased risk of retinoblastoma? Hum Reprod. 2012;27(7):2186–2192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moll AC, Imhof SM, Cruysberg JR, Schouten-van Meeteren AY, Boers M, van Leeuwen FE. Incidence of retinoblastoma in children born after in-vitro fertilisation. Lancet. 2003;361(9354):309–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cancer Registry of Norway, Institute of Population-Based Cancer Research. Cancer in Norway 2013—Cancer incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in Norway. Available at: http://www.kreftregisteret.no/en/General/Publications/Cancer-in-Norway/Cancer-in-Norway-2013/. Accessed August 1, 2016

- 51.Puumala SE, Ross JA, Feusner JH, et al. Parental infertility, infertility treatment and hepatoblastoma: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(6):1649–1656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heck JE, Lombardi CA, Cockburn M, Meyers TJ, Wilhelm M, Ritz B. Epidemiology of rhabdoid tumors of early childhood. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(1):77–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Belson M, Kingsley B, Holmes A. Risk factors for acute leukemia in children: a review. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(1):138–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spycher BD, Lupatsch JE, Zwahlen M, et al. Background ionizing radiation and the risk of childhood cancer: a census-based nationwide cohort study. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(6):622–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wrensch M, Minn Y, Chew T, Bondy M, Berger MS. Epidemiology of primary brain tumors: current concepts and review of the literature. Neuro-oncol. 2002;4(4):278–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herbst AL. Diethylstilbestrol and adenocarcinoma of the vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(6):1576–1578, discussion 1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keegan TJ, Bunch KJ, Vincent TJ, et al. Case-control study of paternal occupation and social class with risk of childhood central nervous system tumours in Great Britain, 1962–2006. Br J Cancer. 2013;108(9):1907–1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharma R, Agarwal A, Rohra VK, Assidi M, Abu-Elmagd M, Turki RF. Effects of increased paternal age on sperm quality, reproductive outcome and associated epigenetic risks to offspring. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13(1):35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Steensel-Moll HA, Valkenburg HA, Vandenbroucke JP, van Zanen GE. Are maternal fertility problems related to childhood leukaemia? Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14(4):555–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Odom LN, Segars J. Imprinting disorders and assisted reproductive technology. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2010;17(6):517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.DeBaun MR, Tucker MA. Risk of cancer during the first four years of life in children from the Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome Registry. J Pediatr. 1998;132(3 pt 1):398–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bjørge T, Cnattingius S, Lie RT, Tretli S, Engeland A. Cancer risk in children with birth defects and in their families: a population based cohort study of 5.2 million children from Norway and Sweden. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(3):500–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.