Highlights

-

•

The elderly population in China is growing exponentially and this growth will last for decades.

-

•

The aging problem in China is expected to lead to a significant socioeconomic burden which will require a combined effort among gerontologists, healthcare professionals, policymakers, and social forces.

-

•

A research agenda on the collection of public health data, diet and food safety, physical exercise, pharmacological interventions in age associated diseases, the elderly and geriatric care, and policy dialogues are potential ways to relieve the aging problem.

-

•

Increased political and financial commitments from the Chinese government are critical for achieving a research agenda on aging in China for the 21st century.

Keywords: Aging, Public health, Chronic non-communicable diseases, Mental health, Geriatric care, Policy, Physical exercise, Pharmacological interventions

Abstract

China is encountering formidable healthcare challenges brought about by the problem of aging. By 2050, there will be 400 million Chinese citizens aged 65+, 150 million of whom will be 80+. The undesirable consequences of the one-child policy, rural-to-urban migration, and expansion of the population of ‘empty nest’ elders are eroding the traditional family care of the elders, further exacerbating the burden borne by the current public healthcare system. The challenges of geriatric care demand prompt attention by proposing strategies for improvement in several key areas. Major diseases of the elderly that need more attention include chronic non-communicable diseases and mental health disorders. We suggest the establishment of a home care-dominated geriatric care system, and a proactive role for researchers on aging in reforming geriatric care through policy dialogs. We propose ideas for preparation of the impending aging burden and the creation of a nurturing environment conducive to healthy aging in China.

1. Introduction

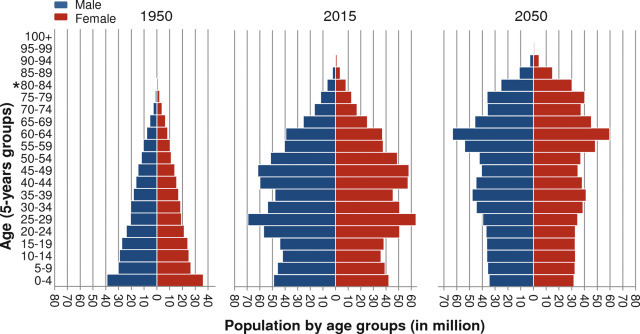

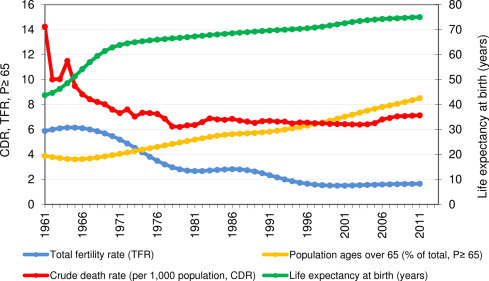

As the second largest global economy, China currently houses the world’s largest population of 1.4 billion (19.13% of the world population), and is rapidly transforming into an aging nation. In 2010, there were 111 million (8.2% of the country population) elderly aged 65+, among them 19.3 million were the oldest-old (aged 80+) (Zeng, 2012, Zeng and George, 2010). It is predicted that in 2050 there will be a large explosion in the elderly population, with up to 400 million aged 65+ (26.9% of the total population), and 150 million aged 80+ (Fig. 1 ) (Zeng, 2012, Zeng and George, 2010). When we scrutinize the trends of aging-associated demographic parameters in China (1961–2011), it appears that the pronounced expansion of the elderly population was caused by a decline in fertility due to the one-child policy, as well as a prolonged life expectancy (Fig. 2 ). In 2010, the total fertility rate was 1.7 (2.5 for global), with the life expectancy being 72 for males (67 years globally) and 76 for females (71 years globally, Table 1 ). In 2050, the elderly support ratio [the number of ‘working age’ people (15–64) divided by those aged 65+] will plummet from 9 in 2010 to 3, comparable to that of the US and Germany (Table 1). Thus, China will be one of the countries in the world with the highest percentage of aged people. This will inevitably give rise to a host of socioeconomical challenges.

Fig. 1.

The changing population demographics for China over time.

By 2050, 26.9% of the Chinese population will be over 65 years old putting a momentous strain on the Chinese healthcare system. Horizontal bars are proportional to number of men (blue) and women (red). *For 1950, data of 5-year groups over 80 are absent, thus are shown in 80+. Data source: Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

Aging-related demographic factors in China over time.

From 1961 to 2011, the Chinese aging population expanded due to increased life expectancy and decreased fertility and death rate. References used are listed in Supplementary data.

Table 1.

Comparison of aging-related demographic factors among China and other countries.

| Country (region) | Population in 2010 |

Age-standardized death rates per 100,000 population in 2010 |

TFRa (2010) |

Life expectancy (2010) |

ESRb |

Population densityc |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | Population ages ≥65 (%) | All causes | Communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional disorders (GBD group I) | Non-communicable diseases (GBD group II) | Cardiovascular diseases | Neoplasms | Injuries (GBD group III) | Male | Female | 2010 | 2050 | 2010 | 2050 | ||

| Global | 6,916,183,482 | 8.00 | 784.5 | 189.8 | 520.4 | 234.8 | 121.4 | 74.3 | 2.5 | 67 | 71 | 9 | 4 | – | – |

| China mainland (total) | 1,340,910,000 | 8.35 | 606.8 | 40.7 | 509.4 | 230.8 | 148.0 | 56.7 | 1.7 | 72 | 76 | 9 | 3 | 142 | 144 |

| Hong Kong (China) | 7,024,200 | 12.90 | 340.0 | 50.8 | 255.6 | 74.9 | 111.6 | 19.8 | 1.1 | 80 | 86 | 6 | 2 | 6414 | 7283 |

| USA | 309,326,295 | 13.06 | 515.5 | 30.2 | 436.6 | 161.7 | 128.8 | 48.7 | 1.9 | 75 | 80 | 5 | 3 | 32 | 42 |

| Germany | 81,751,602 | 20.60 | 433.5 | 19.5 | 386.0 | 160.6 | 132.2 | 28.0 | 1.4 | 77 | 82 | 3 | 2 | 233 | 203 |

References used are listed in Supplementary data.

TFR: Total fertility rate in 2010.

ESR: Elderly support ratio, the number of people of “working age” (15–64), divided by those ages 65 and above.

Population density (persons per square km).

A consequence of the substantial demographic change is a surge in the prevalence and incidence of age-associated diseases encompassing cancer, chronic non-communicable diseases (CNCDs), and mental health disorders, among others (Table 1) (Wang et al., 2005, Yang et al., 2008, Yang et al., 2013, Zhang and Li, 2011). Studies from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS) disclosed an age-dependent increase of disability in performing Activities of Daily Living (ADL) in the Chinese elderly, with <5% in 65–69 years of age, and 20% in 80–84 years old, rising to around 40% in 90–94 years old, indicating an urgent need for daily life assistance and geriatric care to the elderly (Zeng, 2012). China’s current healthcare system, however, is not ready for this population shift, and the government has not yet acted to prepare for these emerging challenges. Continued inaction by policymakers could potentially lead to a healthcare disaster. However, steps can be taken to avert this crisis. Evidence-based healthcare reform and social programs fueled by discoveries from the broad field of aging research can be implemented to greatly mitigate this pending crisis. Therefore, to facilitate action, lessen suffering, and improve quality of life, we propose an urgent agenda on aging to counter the emerging challenges attributed to the problem of aging in China. We hope that this strategy can attract public attention, discussion, support, and action. Research advances and government investments on issues mentioned below will be of prime importance for winning the imminent health battle.

2. Health challenges in the Chinese elderly

Despite outbreaks of various infectious diseases, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), H5N1 (bird influenza), and H1N1 in recent years in China, the country has experienced an epidemiological transition from infectious diseases to CNCDs (Peiris et al., 2012, Yang et al., 2008, Zhu et al., 2013). Although some progress has been made, attention from the public and government sectors in age-associated CNCDs is lagging behind. Erosion of the traditional family care of the elderly combined with insufficient geriatric care resources exacerbates the challenges caused by aging in China.

2.1. Chronic non-communicable diseases (CNCDs)

CNCDs are the leading disease burdens in China and they are reaching epidemic proportions. In China, CNCDs account for an estimated 80% of total deaths and 70% of total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost, with the leading causes of death in 2010 being stroke, ischaemic heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Wang et al., 2005, Yang et al., 2013). In China, there are more than 100 million adults with diabetes, and over 177 million adults with hypertension (Anon., 2014a; Yang et al., 2008). Major causes leading to severe CNCDs in China include unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, high rates of smoking and alcohol consumption (Yang et al., 2008). For instance, high sodium consumption is prevalent in the daily diet of the Chinese people. This salty diet is a risk factor for hypertension, and may further escalate the predisposition to metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases (Bi et al., 2014, Chen et al., 2009, Yang et al., 2008). In China, around 21% of the people smoke and 53% of the people are exposed to second-hand smoke, rendering a majority of the population vulnerable to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases as they age (Yang et al., 2008, Yang et al., 2015, Yang et al., 2013). Over 50% of men aged 15+ have consumed significant amounts of alcohol, which contributes to 13.8 million DALYs and over 0.31 million deaths every year (Evaluation, 2015, Jiang et al., 2015). Alcohol consumption is a risk factor in the development of hypertension and stroke in the elderly Chinese, with stroke ranking as the number one cause of death in China in 2010 (1.7 million deaths) (Liu et al., 2002, Yang et al., 2013). Thus, the burden of CNCDs and associated health-care costs are rising significantly for the elderly with chronic diseases requiring long-term medical services and support.

Current healthcare resources for elders with CNCDs in China may be insufficient to cover the emerging aging population. Indeed, CNCDs have received little attention from the Chinese government as evident from the fact that in 2008, around 35% CNDCs patients from the rural areas did not receive necessary healthcare services from the hospitals (Tang et al., 2013). Urgent action is needed for the government to develop associated policies to encourage research and prevention of CNCDs. In addition, further investments in healthcare resources focused on CNCDs should be made. Specifically, it has been suggested that possible procedures for reducing the incidence of CNCDs include: raising public awareness, enhancing economic, legal and environmental policies, modifying risk factors, and re-orientating healthcare systems (Daar et al., 2007). For example, heightening the public awareness of a healthy diet and abundant exercise can lower the prevalence of CNCDs (detailed below). Collectively, there is an urgent need for the government to develop a comprehensive evidence-based policy pertaining to CNCDs, while at the same time provide adequate funding for research and expansion of the health care system specific to CNCDs.

2.2. Mental health disorders

Mental health disorders, including dementia and depression, are another type of major, but less focused disorders in the Chinese elderly. There are more than 9 million elders in China afflicted with dementia, ranging from 3.2% to 9.9% among elders living in different areas of Mainland China (Pei et al., 2014). The incidence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI, a precursor for dementia), with regional prevalence ranging from 5.4% to 25.0% exacerbates the morbidity of dementia (Cheng and Xiao, 2014). These numbers will undoubtedly escalate as the demographic feature progresses to a large elderly population. Smoking, heavy alcohol consumption, and depression are among the major risk factors of dementia (Pei et al., 2014). However, many of the dementia sufferers in China, especially those residing in rural areas, have not been diagnosed or received professional care due to limited affordable access to the healthcare resources. Taking care of demented elders by their children and extended families brings considerable physical, psychological, and financial challenges to the families and raises the needs for government subsidy, as well as community care and institutional care (Cheng and Xiao, 2014, Pei et al., 2014, Peng and Wu, 2015). Indeed, with a yearly cost of $109 billion in the US, dementia remains the most costly of all diseases (Hurd et al., 2013). Considering that this is the price for the ∼5 million patients suffering from dementia in the US, the equivalent cost for the much more enormous Chinese population would be several-fold higher.

Depression is common and often neglected in the elderly Chinese. In recent years, rapid socioeconomic transition and the erosion of the traditional family may contribute to the morbidity of mental diseases in the Chinese elderly, especially depression (Zeng, 2012). A cross-sectional survey disclosed that over 39% of elders had self-reported depressive symptoms, which were associated with a lack of family support and a poor health status (Yu et al., 2012). This prevalence of depression increased to about 45% in the oldest old population (Yu et al., 2012). As an international challenge, depression aggravates the quality of life, brings burden to the health care system and increases the risk of death (Zhang and Li, 2011). Compared to other common aging diseases, depression may be underdiagnosed and people with depression are less likely to seek therapy due to the stigma of mental illness in some areas of China (Zhang and Li, 2011).

Much attention should be paid to challenges of mental disorders in the Chinese elderly. Elevating the public awareness of mental disorders should be prioritized as well as enhancing the medical support resources for early detection, intervention and treatment of mental illness in the elderly. Professional interventions, comprising psychotherapy and combined cognitive–psychological–physical intervention not only can mitigate subclinical depression, but can also delay age-related brain and cognitive deterioration and improve overall mental health (Cuijpers et al., 2014, Li et al., 2014, Yin et al., 2014). A recommendation to medical universities is to train more geriatric care professionals to meet the increasing demand. Further, family and community support are of paramount importance for the elderly with brain disorders. Accordingly, emerging evidence supports positive effects of social interventions such as playing mahjong and practicing Taichi, on brain health although further large-scale studies are warranted (Cheng et al., 2006, Wei et al., 2013).

2.3. Obesity and diabetes: expanding disease burdens in the younger generations

Major diseases that are emerging in the younger Chinese population may lead to new challenges to the geriatric care system over time. For instance, diabetes that was previously uncommon in the Chinese population, has over the last decades increased dramatically in prevalence especially in the younger generation (Blumenthal and Hsiao, 2015, Chen and Yang, 2014, Hu et al., 2011). The prevalence of diabetes increased from 2.5% in 1994 to 9.7% in 2007 (Chen and Yang, 2014). In 2013, 11.6% (over 100 million) adults had diabetes and 50.1% had prediabetes (Chan et al., 2014); 23% of males and 14% of females under the age of 20 were overweight or obese (Ng et al., 2014). One can foresee a further aggravation of this trend due to the heightened living standard, exaggerated caloric intake and infrequent exercise, as well as other unhealthy lifestyles (Hu et al., 2011). The healthcare system in China does not appear to be equipped to deal with the epidemic level of diabetes and the future cost of a lack of current interventions is likely to be exorbitant. Diabetes has a combined effect on productivity and healthcare, with an annual projected cost of 60 billion USD by 2030 Anon. (2014a). Thus, public education and behavioral intervention (healthy diet and exercise) should be applied to the young population as soon as possible (Anon., 2014a; Chen and Yang, 2014; Hu et al., 2011). In addition, the government should anticipate the adverse outcomes of diabetes when making long-term geriatric care policies.

2.4. Erosion of the traditional family care ensuing in phenomenon of ‘empty nest’ elderly

The Chinese tradition of taking care of the elders by their extended families, especially their children, is threatened by new socioeconomical changes, including urbanization, one-child policy, emigration, and new perceptions. In China, family support is an old tradition and is the prevailing way to take care of old people, which is executed by their children with filial piety [“ (xiào)” in Chinese]. In recent decades, the ‘4-2-1’ (four grandparents, two parents, and one child) family structure emanated from the one-child policy leading to a series of challenges (Hongwei et al., 2008). For people born in compliance with the one-child policy after 1980, it is likely that they have to care for two parents and four grandparents by themselves. The speedy economic growth in China over these years is rapidly inducing a series of socioeconomic changes, including the over 200 million rural-to-urban migrants who move to and temporarily live in cities with the intention to grasp better employment opportunities (Zou et al., 2014). This urban migration combined with an expanding trend in young couples of living separately from their parents, giving rise to the ‘empty nest’ phenomenon, is common not only in rural areas but also in urban cities, with a prevalence rate of 31.8% in 2010 (Liu et al., 2015, Liu and Guo, 2008, Zou et al., 2014). The ‘empty nest’ is negatively associated with life satisfaction, and ‘empty nest’ elders manifest a higher incidence of depression and loneliness, and have an urgent need for geriatric care services, especially home care (Liu et al., 2015, Liu and Guo, 2008). An inadequate geriatric care resource, including a deficiency of geriatric professionals (physicians, nurses, and geriatric care managers) and home care resources, makes it a daunting challenge to the society.

(xiào)” in Chinese]. In recent decades, the ‘4-2-1’ (four grandparents, two parents, and one child) family structure emanated from the one-child policy leading to a series of challenges (Hongwei et al., 2008). For people born in compliance with the one-child policy after 1980, it is likely that they have to care for two parents and four grandparents by themselves. The speedy economic growth in China over these years is rapidly inducing a series of socioeconomic changes, including the over 200 million rural-to-urban migrants who move to and temporarily live in cities with the intention to grasp better employment opportunities (Zou et al., 2014). This urban migration combined with an expanding trend in young couples of living separately from their parents, giving rise to the ‘empty nest’ phenomenon, is common not only in rural areas but also in urban cities, with a prevalence rate of 31.8% in 2010 (Liu et al., 2015, Liu and Guo, 2008, Zou et al., 2014). The ‘empty nest’ is negatively associated with life satisfaction, and ‘empty nest’ elders manifest a higher incidence of depression and loneliness, and have an urgent need for geriatric care services, especially home care (Liu et al., 2015, Liu and Guo, 2008). An inadequate geriatric care resource, including a deficiency of geriatric professionals (physicians, nurses, and geriatric care managers) and home care resources, makes it a daunting challenge to the society.

3. To establish an aging friendly society

A 2008CLHLS report showed that around one fourth of the Chinese oldest old, 28% in rural and 22% in urban areas, had needs for assistance in personal activities during daily living which were not met (Peng et al., 2015). In view of the distinctiveness of China’s culture, demographic structure, and other associated socioeconomical concerns, it is likely that establishment of a home care-dominated, supported by community care, and supplemented with institutional care (such as nursing home) as well as other alternatives may help to meet the escalating burden of the aging society (Liu et al., 2015).

3.1. Establishing a home care-dominated, community care and institution care-supplemented geriatric care system in China

Establishment of a home care-dominated geriatric care system is in line with the domestic needs of the elderly in China. Some of the authors in this review have been closely involved in drafting the Five-year Plan (13th, 2016-2020) (the central government blueprint for China’s long-term socioeconomical policies) which suggest that geriatric care should be provided by home care (80%), community care (15%), and institutional care (5%). The elderly Chinese prefer to receive home-based care rather than institutional care since they are accustomed to their current lifestyles, enjoying freedom, comfort, and convenience (Liu et al., 2015). For physically active elders, staying with their children seems to be beneficial for improving the quality of life, enhancing self-satisfaction, and curtailing the incidence of psychological disorders of the elderly (Zeng, 2012, Zhang and Li, 2011). For ‘empty nest’ elders, home care is most appropriate for the physically active individuals, and also desirable for elderly with minor challenges in their daily lives, for the latter who can derive support from their extended families and the local community, or hiring a housemaid (or hourly worker) (Liu et al., 2015). Community care is cost-effective, with community participation and connectedness, and is needed for elderly with challenges in their daily living. However, in China, even in big cities, there is a lack of available social support services provided by the communities (Liu et al., 2015). Recently, the ‘aging-in-place’, a home and community care combined concept has been suggested as a good way to meet the aging challenges in China (Liu et al., 2015, Wu, 2009). To establish and expand this ‘aging-in-place’ system, we suggest that the government establishes an elderly-friendly community, including renovation of house facilities, recruitment of social work volunteers, establishing community medical service (family-doctor oriented primary care), and providing high-quality affordable home care services from both public and private sectors.

For elders with significant challenges in daily living, long-term care institutions (LTC) can provide them with daily professional healthcare (Wu et al., 2005). However, many Chinese elders do not like to go to institutions due to the concerns of low acceptance rate, high price, uncontrolled service, and a concern of family reputation (parents living in a nursing home may reflect that the children are impious) (Liu et al., 2015). Even with a significant expansion of LTC in China, e.g., by increasing the number of beds from 0.735 million in 1990 to 4.2 million in 2012, it is still far in excess of the requirements in view of a scarcity of qualified frontline healthcare professionals in LTC (Peng and Wu, 2015). Thus, the recommendation for the Chinese government is to expand the number of LTC with high-quality service at an affordable price for the elderly.

There is an emerging requirement for institutional care in China, especially in the urban areas. For disabled and frail elders in the urban areas, there is a challenge to find their adult children to take care of them due to the one-child policy as well as the geographic migration in the younger generation, and a major option for them is institutional elder care (Zhan et al., 2006). It should be noticed that elders have an increased expectation of the service provided by institutions, including service, financing, workforce, and care management (Wu et al., 2005). To establish a healthy development of institutional elder care system in China, the following suggestions to address several issues are made: establishing an environment for fair competition between governmental and non-governmental elder care systems; enhancing regulatory oversight and quality assurance with information systems; and nurturing stable professionalized elder care specialists through systematic geriatric education and training (Feng et al., 2012, Zhan et al., 2006). In particular, increase in regional and national government funding, integration of long-term care with the acute health care system, and an establishment of multifunctional LTC facilities are encouraged (Wu et al., 2009). In summary, addressing the aging challenges is more than just geriatric care. We should include a broad array of social services—long-term services and supports to the disabled and frail elders.

3.2. Information technology (IT)-equipped mobile geriatric services

Uneven geographic distribution of population and unmatched geriatric services make it impossible to design a ‘one-for-all’ healthcare reform strategy in China. In contrast to a dense population in megacities, such as Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou, there is a sparse population in the countryside and the northwest regions accompanied with less geriatric care resources (Jahn et al., 2011). There are large disparities of geriatric care resources for senior citizens residing in the rural areas, where they have to be content with a lower quality of life associated with a lower income, inadequate care from their children who have employment in big cities, heightened incidence of depression, loneliness, and attenuated medical and social support measures (Dong and Simon, 2010). Thus, IT-equipped mobile geriatric services are useful for the rural areas, especially the northwest regions.

3.3. Diseases prevention and early diagnosis through primary care

Disease prevention is in most cases more cost-effective than disease treatment, and can be achieved through primary care (Chan et al., 2014, Wang et al., 2005). Establishment of the family doctor model may help to provide a better primary care, especially for elderly in the wide rural areas. The WHO recommends primary care systems to be universally accessible to individuals and families by means of acceptable and affordable ways (Europe). The predictable results of a well-established primary health care system are increased disease prevention, earlier diagnosis of diseases, and use of an appropriate regimen at an affordable price, while at the same time amelioration of the heavy workload in overcrowded big public hospitals. Experience from Hong Kong suggests public education to make people, especially elders, aware of the demand for primary care which should be affordable and quality-certified (Griffiths and Lee, 2012, Liu et al., 2013a). Primary care emphasizes stable and close communication between the elderly and their family doctors. Imbalance of the distribution of primary care between rural and urban areas should be changed. In 2008, the Chinese government launched the fourth health-care reform plan with one aim that proposes to establish a three-tier medical network at country, town, and village levels with emphasis on infrastructure and human-resource development (Chen, 2009). Many universities in China have established ‘family medicine’ disciplines to train family doctors aspiring to provide resources for the Chinese primary health care systems. Government policy supports are likely able to encourage more family doctors to work in rural areas.

3.4. Maintaining a vigorous lifestyle: tobacco-free, diet and exercise

A healthy diet and enough physical exercise are critical to healthy aging. A poor diet, together with hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and smoking are the top ranking risk factors for the contemporary Chinese population (Yang et al., 2013). Public education in conjunction with policy intervention is likely efficacious in undermining the disease risks. Through the promotion of several tobacco control policies, effective education and public engagement, there is a better awareness of the health hazards of smoking, which results in fewer smokers and has facilitated bans on smoking in most public areas (Yang et al., 2015). In Hong Kong, a youth-oriented smoking cessation hotline was able to accomplish a smoking cessation rate of 23.6% among participates in the last ten years (Kong, 2015). In November 2014, Beijing’s Municipal Government passed the new legislation of the national tobacco control guideline which prohibits smoking in all indoor and some outdoor public places Anon. (2014b). Another example is to combat hypertension through restriction in sodium intake. China has over 177 million adults with hypertension which is associated with excessive sodium intake, and strategies to diminish population-level dietary sodium consumption and hypertension have been implemented in some provinces of China (Bi et al., 2014, Chen et al., 2009, Yang et al., 2008). Reinforced efforts by the government to help people to establish a healthy lifestyle are necessary.

Although no amount of physical activity can halt the biological aging process, there are ample benefits of regular physical activity in older adults: regular exercise can minimize the physiological effects of an otherwise sedentary lifestyle and extend active life expectancy by inhibiting the development and progression of chronic disease and disabling conditions (AmericanCollegeofSportsMedicine, 2009). Furthermore, there is also emerging evidence for significant psychological and cognitive benefits accruing from participation in regular exercise by older adults. Meanwhile, an increasing number of China’s retirees, especially women, have organized themselves into morning exercise groups and dance groups, which can be easily spotted in China’s city parks or street corners. However, there have not been enough vigorous evaluation studies in China on the health benefits of regular physical activity among the older adults (Chang et al., 2013). China has an opportunity to contribute to this important body of knowledge.

3.5. Towards pharmacological interventions in aging

Pharmacological interventions provide a possibility of achieving both a healthy and long lifespan for the elderly. With the increasing socioeconomic burden of an aging Chinese population, interventions that may minimize the incidence of chronic diseases will become ever more important. In recent decades, great strides have been made in the understanding of the molecular etiology of aging, however, interventions that postpone age-related diseases have only recently been suggested (Longo et al., 2015). Importantly, all interventions that lengthen lifespan also appear to curtail the incidence of chronic diseases (Milne et al., 2007, Rubinsztein et al., 2011, Shepherd, 2009). Caloric restriction is the oldest known behavioral intervention that may extend life- and/or health-span in organisms ranging from yeasts to primates. However, it is extraordinarily difficult to achieve good compliance with this intervention. Alternatively, pharmacological interventions that target key regulators of longevity could prove beneficial in postponing age associated diseases. Molecular targets could include longevity factors such as the mTOR pathway, sirtuins, FOXOs and others that have shown promising results in model organisms (Longo et al., 2015). For instance, sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) has been associated with longevity in yeast, nematodes, and mice, and small bioactive SIRT1 activators can improve both lifespan and healthspan in mice (Longo et al., 2015, Mitchell et al., 2014). Results from these studies support a possibility of pharmacological interventions in human aging.

It appears clear that several pathways are now emerging that might target aging and thereby chronic diseases in a broad sense. An obstacle to these studies lies in the difficulty with which human trials in aging can be conducted. We suggest performing clinical trials on the anti-aging efficacy of some of the above mentioned targets and in the Chinese population. In view of the substantial socioeconomic burden of the aging Chinese society, it appears clear that these types of interventions could have a significant impact on many aspects of China’s future.

3.6. Centenarian studies

Even though aging is still a fundamental and unsolved mystery in biology, the population of centenarians has been increasing in China and around the world. It is expected that there will be an18-fold increase in the population of centenarians from 180,000 in 2000 to 3.2 million by 2050 (Wong et al., 2014). Thus, studies on centenarians have drawn special attention in recent years since they may provide valuable information pertaining to longevity. At the demographic level, centenarian studies furnish information on geographic distribution, gender difference, previous occupation, lifestyle, mortality, survival rate, etc. Taking the advantage of the current advanced biomedical techniques, we are also trying to decode the secrets of longevity of these centenarians by testing any changes in specific genes and proteins for biochemical, phenotypic, or genetic variations.

Scientists in China have made significant progress in centenarian studies. Studies on old people and centenarians of wide geographic distribution revealed that longevity is at least associated with a healthy diet, adequate exercise, active social activities, and a good social network (Liu et al., 2014, Ruan et al., 2013, Wang et al., 2014). An important database of the aging Chinese population is CLHLS which aims to uncover determinants of healthy longevity in China and is continually updated (Zeng, 2012). Hong Kong is also facing an immense pressure arising from an ever-increasing population of near-centenarians and centenarians, and plenty of social activity as well as a positive attitude are of prime importance for a high quality of life among them (Wong et al., 2014). Possible further directions of centenarian studies include unveiling the mechanisms of different environmental and genetic parameters in longevity.

4. Renovation of China’s health care system and policy dialogs

Establishment of a good health care system, which can cover affordable, high-quality health care for every individual, especially for the elderly, is the goal of the Chinese government, and this necessitates a close coordination with researchers of associated disciplines. Over the past 65 years, China experienced three phases of health care evolution and it is now in an ongoing fourth phase of evolution aiming at providing affordable basic health care for all Chinese people by 2020 (Blumenthal and Hsiao, 2015, Chen, 2009). Indeed, the Chinese health care system has made several accomplishments over the past decades, including significant elimination of infant mortality and age-old scourges (eg., schistosomiasis) for more than 1.3 billion people (Blumenthal and Hsiao, 2015). However, the Chinese health care system has been facing daunting challenges, such as insufficient doctors compared to the number of patients, unaffordable costs of care for the majority of the Chinese people and inequities of healthcare resources between rural areas and affluent cities. For example, China has 2.8 doctors and nurses/1000 population and 0.97 nurse-to-doctor ratio, compared with the corresponding values of 12.3 and 4.05, respectively in the US, and 9.6 and 2.1 in Europe (Crisp and Chen, 2014).

Thus, we suggest attention to the undermentioned points which may help to shore up China’s health care system. First, reduce the costs of comprehensive health coverage to an affordable level with the joint efforts of central/local government, public/private insurance companies, and healthcare providers. On 17 May 2015, the Chinese government released a directive promoting a comprehensive reform of public hospitals in cities, aiming at scrapping the profit-driven model of public hospitals in order to provide the public with good but affordable medical services (The state council, 2015). Second, recruit sufficient high-quality health professionals to provide equal and patient-oriented services, while at the same time providing the health professionals with competitive accommodation; Third, improvement of rural health care through increased health care investment by the government and the further development of the rural health insurance system. Furthermore, the government should provide satisfactory facilities and devising strategies to attract doctors to work in the rural areas. In addition, the health care system should be sensitive and flexible to demographic changes, and establish strategies to meet the aging society in China in the foreseeable future.

A special attention is the role of policy dialogs in the health care reforms. There has been some experience in improving health insurance in rural China, emphasizing the timely and effectively transition of research results to policy making (Liu, 2004, Liu et al., 2006, Liu and Rao, 2006). Policy makers play a key role in lessening the emerging aging burden in China. It is postulated that effective policy dialogs can positively regulate aging issues in China, both by increasing government funding for Chinese aging studies, and the involvement of private donors. The significance of policy dialogs between geriatric scientists, public health experts and policy makers needs to be stressed. A standard mechanism to translate research output from scientists to policy at the system level is not well-established, and hence translational bench-to-bedside studies may lack the momentum to generate useful societal changes (Jiang et al., 2013, Liu et al., 2013b). Channels to communicate first-hand scientific results to policy makers and to amplify the voice of geriatric and public health researchers in policy making are imperative to implement cost-effective and evidence-based policies.

5. Conclusions and perspectives

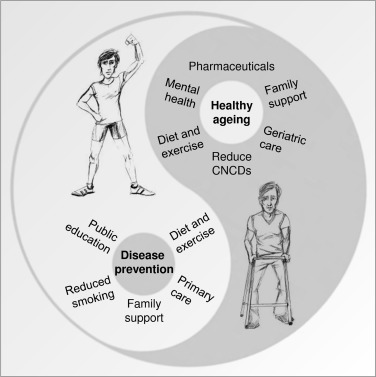

China has a fast growing elderly population, which brings and will continue to bring a series of socioeconomical challenges to the current health care system. Even though it is impossible to comprehensively portray the multitude of emerging challenges of aging in China, accumulating evidence indicates that CNCDs, geriatric care, and the other concerns as delineated above, are the priorities to address among the various emerging aging issues in China. One priority of the Chinese healthcare reform for the elderly is to establish home-care dominated geriatric care systems. In addition to the reform of public hospitals to provide affordable services, establishment of primary care services will likely facilitate general geriatric care, early diagnosis and intervention of common geriatric disorders, with both clinical and cost benefits. Other socioeconomical topics to address among the aging issues in China include pension benefits and retirement policy. A longitudinal perspective calls for an attention to disease burden in the young population when implementing a healthcare policy in the elders (Fig. 3 ). Close collaboration among researchers on different aspects of the Chinese aging studies, the government, international research institutions, research-funding agencies, and other associated health care sections is pivotal and should be encouraged. Increased allocation in research funding for aging studies in China should be given consideration of the top priority.

Fig. 3.

Possible interventions to promote healthy aging in China.

As exemplified in the old Chinese ‘Yin-Yang’ theory interventions that lead to healthy aging should not only be considered for the elderly population but should start at an early age. Thus, the importance of public health education and healthy behavioral interventions to the younger population, as a cost-effective way for health-care development, should be equally weighted. Sustainable scientific research, financial investments, and most powerfully political strategy should result in a positive environment for the elderly population in China, their family and the communities in which they reside.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

We sincerely apologize to colleagues whose work we could not include due to space limitations. This article was written in a personal capacity (EFF, MSK, HL, VB) and does not represent the opinions of the National Institute on Aging, the US Department of Health and Human Services, or the US Federal Government.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program (Grant number: Z01-AG000723-02) of the NIH, National Institute on Ageing, USA. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. We thank Drs. Peter Sykora and Joseph Hsu at NIA, NIH for reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.08.003.

Contributor Information

Evandro Fei Fang, Email: evandro.fang@nih.gov.

Morten Scheibye-Knudsen, Email: scheibyem@mail.nih.gov.

Heiko J. Jahn, Email: heiko.jahn@uni-bielefeld.de.

Juan Li, Email: lijuan@psych.ac.cn.

Li Ling, Email: lingli@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Hongwei Guo, Email: hwguo@shmu.edu.cn.

Xinqiang Zhu, Email: zhuxq@zju.edu.cn.

Victor Preedy, Email: victor.preedy@kcl.ac.uk.

Huiming Lu, Email: huiming.lu@nih.gov.

Vilhelm A. Bohr, Email: BohrV@grc.nia.nih.gov.

Wai Yee Chan, Email: chanwy@cuhk.edu.hk.

Yuanli Liu, Email: yuanliu@hsph.harvard.edu, yliu@pumc.edu.cn.

Tzi Bun Ng, Email: b021770@mailserv.cuhk.edu.hk, tzibunng@cuhk.edu.hk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- AmericanCollegeofSportsMedicine. 2009. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Anon Diabetes in China: mapping the road ahead. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:923. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70189-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anon A step change for tobacco control in China? Lancet. 2014;384:2000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Z., Liang X., Xu A., Wang L., Shi X., Zhao W., Ma J., Guo X., Zhang X., Zhang J. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control and sodium intake in Shandong Province, China: baseline results from Shandong-Ministry of Health Action on Salt Reduction and Hypertension (SMASH), 2011. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E88. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal D., Hsiao W. Lessons from the East–China’s rapidly evolving health care system. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1281–1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1410425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J.C., Zhang Y., Ning G. Diabetes in China: a societal solution for a personal challenge. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:969–979. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.F., Lin M.H., Wang J., Fan J.Y., Chou L.N., Chen M.Y. The relationship between geriatric depression and health-promoting behaviors among community-dwelling seniors. J. Nurs. Res.: JNR. 2013;21:75–82. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0b013e3182921fc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Gu D., Huang J., Rao D.C., Jaquish C.E., Hixson J.E., Chen C.S., Chen J., Lu F., Hu D. Metabolic syndrome and salt sensitivity of blood pressure in non-diabetic people in China: a dietary intervention study. Lancet. 2009;373:829–835. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yang W. Epidemic trend of diabetes in China: for the Xiaoren Pan Distinguished Research Award in AASD. J. Diabetes Invest. 2014;5:478–481. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. Launch of the health-care reform plan in China. Lancet. 2009;373:1322–1324. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60753-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S.T., Chan A.C., Yu E.C. An exploratory study of the effect of mahjong on the cognitive functioning of persons with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2006;21:611–617. doi: 10.1002/gps.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Xiao S. Recent research about mild cognitive impairment in China. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry. 2014;26:4–14. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp N., Chen L. Global supply of health professionals. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:950–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1111610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., Koole S.L., van Dijke A., Roca M., Li J., Reynolds C.F. Psychotherapy for subclinical depression: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2014;205:268–274. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.138784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daar A.S., Singer P.A., Persad D.L., Pramming S.K., Matthews D.R., Beaglehole R., Bernstein A., Borysiewicz L.K., Colagiuri S., Ganguly N. Grand challenges in chronic non-communicable diseases. Nature. 2007;450:494–496. doi: 10.1038/450494a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X., Simon M.A. Health and aging in a Chinese population: urban and rural disparities. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2010;10:85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00563.x. Europe, W. Primary health care. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation, I.f.H.M.a. 2015. China Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 (GBD 2010) Results 1990–2010. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/china-global-burden-disease-study-2010-gbd-2010-results-1990-2010.

- Feng Z., Liu C., Guan X., Mor V. China’s rapidly aging population creates policy challenges in shaping a viable long-term care system. Health Aff. 2012;31:2764–2773. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths S.M., Lee J.P. Developing primary care in Hong Kong: evidence into practice and the development of reference frameworks. Hong Kong Med. J. 2012;18:429–434. Xianggang yi xue za zhi/Hong Kong Academy of Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongwei W., Fang Y., Kolanowski A. Caring for aging Chinese: lessons learned from the United States. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2008;19:114–120. doi: 10.1177/1043659607312971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F.B., Liu Y., Willett W.C. Preventing chronic diseases by promoting healthy diet and lifestyle: public policy implications for China. Obes. Rev. 2011;12:552–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd M.D., Martorell P., Delavande A., Mullen K.J., Langa K.M. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn H.J., Schneider A., Breitner S., Eissner R., Wendisch M., Kramer A. Particulate matter pollution in the megacities of the Pearl River Delta, China—a systematic literature review and health risk assessment. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2011;214:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F., Zhang J., Shen X. Towards evidence-based public health policy in China. Lancet. 2013;381:1962–1964. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Room R., Hao W. Alcohol and related health issues in China: action needed. Lancet Global Health. 2015;3:e190–e191. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong, T.U.o.H. 2015. HKU Youth Quitline appreciates peer smoking cessation counsellors in the 10th anniversary celebration ceremony http://www.hku.hk/press/press-releases/detail/12642.html.

- Li R., Zhu X., Yin S., Niu Y., Zheng Z., Huang X., Wang B., Li J. Multimodal intervention in older adults improves resting-state functional connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and medial temporal lobe. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:39. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.E., Tian J.Y., Yue P., Wang Y.L., Du X.P., Chen S.Q. Living experience and care needs of Chinese empty-nest elderly people in urban communities in Beijing, China: a qualiative study. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2015;2:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.J., Guo Q. Life satisfaction in a sample of empty-nest elderly: a survey in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Qual. Life Res. 2008;17:823–830. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.S., Chen M.Q., Zeng G.Y., Zhou B.F. A forty-year study on hypertension. Zhongguo yi xue ke xue yuan xue bao Acta Acad. Med. Sin. 2002;24:401–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Yam C.H., Huang O.H., Griffiths S.M. a). Willingness to pay for private primary care services in Hong Kong: are elderly ready to move from the public sector? Health Policy Plan. 2013;28:717–729. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Development of the rural health insurance system in China. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:159–165. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Berman P., Yip W., Liang H., Meng Q., Qu J., Li Z. Health care in China: the role of non-government providers. Health Policy. 2006;77:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Rao K. Providing health insurance in rural china: from research to policy. J. Health Polit. Policy Law. 2006;31:71–92. doi: 10.1215/03616878-31-1-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Yang G., Zeng Y., Horton R., Chen L. Policy dialogue on China’s changing burden of disease. Lancet. 2013;381:1961–1962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.L., Luo K.L., Lin X.X., Gao X., Ni R.X., Wang S.B., Tian X.L. Regional distribution of longevity population and chemical characteristics of natural water in Xinjiang, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;473–474:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.11.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo V.D., Antebi A., Bartke A., Barzilai N., Brown-Borg H.M., Caruso C., Curiel T.J., de Cabo R., Franceschi C., Gems D. Interventions to slow aging in humans: are we ready? Aging Cell. 2015 doi: 10.1111/acel.12338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne J.C., Lambert P.D., Schenk S., Carney D.P., Smith J.J., Gagne D.J., Jin L., Boss O., Perni R.B., Vu C.B. Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;450:712–716. doi: 10.1038/nature06261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S.J., Martin-Montalvo A., Mercken E.M., Palacios H.H., Ward T.M., Abulwerdi G., Minor R.K., Vlasuk G.P., Ellis J.L., Sinclair D.A. The SIRT1 activator SRT1720 extends lifespan and improves health of mice fed a standard diet. Cell Rep. 2014;6:836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng M., Fleming T., Robinson M., Thomson B., Graetz N., Margono C., Mullany E.C., Biryukov S., Abbafati C., Abera S.F. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:766–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J.J., Giron M.S., Jia J., Wang H.X. Dementia studies in Chinese populations. Neurosci. Bull. 2014;30:207–216. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1420-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris J.S., Poon L.L., Guan Y. Public health. Surveillance of animal influenza for pandemic preparedness. Science. 2012;335:1173–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1219936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R., Wu B. Changes of health status and institutionalization among older adults in China. J. Aging Health. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0898264315577779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng R., Wu B., Ling L. Undermet needs for assistance in personal activities of daily living among community-dwelling oldest old in China from 2005 to 2008. Res. Aging. 2015;37:148–170. doi: 10.1177/0164027514524257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan R., Feng L., Li J., Ng T.P., Zeng Y. Tea consumption and mortality in the oldest-old Chinese. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013;61:1937–1942. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein D.C., Marino G., Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011;146:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd A. Nutrition through the life span. Part 3: adults aged 65 years and over. Br. J. Nurs. 2009;18:301–302. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.5.40542. 304–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S., Ehiri J., Long Q. China’s biggest, most neglected health challenge: non-communicable diseases. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2013;2:7. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The state council, T.p.s.r.o.C. 2015. Directive on an comprehensive reform of public hospitals in cities (in Chinese). http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2015-05/17/content_9776.htm.

- Wang J., Chen T., Han B. Does co-residence with adult children associate with better psychological well-being among the oldest old in China? Aging Mental Health. 2014;18:232–239. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.837143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Kong L., Wu F., Bai Y., Burton R. Preventing chronic diseases in China. Lancet. 2005;366:1821–1824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G.X., Xu T., Fan F.M., Dong H.M., Jiang L.L., Li H.J., Yang Z., Luo J., Zuo X.N. Can Taichi reshape the brain? A brain morphometry study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong W.C., Lau H.P., Kwok C.F., Leung Y.M., Chan M.Y., Chan W.M., Cheung S.L. The well-being of community-dwelling near-centenarians and centenarians in Hong Kong: a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-14-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Carter M.W., Goins R.T., Cheng C. Emerging services for community-based long-term care in urban China: a systematic analysis of Shanghai’s community-based agencies. J. Aging Soc. Policy. 2005;17:37–60. doi: 10.1300/J031v17n04_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Mao Z.F., Zhong R. Long-term care arrangements in rural China: review of recent developments. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2009;10:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.S. Ageing-in-place in China: practices and experiences. International Federation on Ageing (IFA’s) 9th Global. Conference on Ageing. 2009:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Kong L., Zhao W., Wan X., Zhai Y., Chen L.C., Koplan J.P. Emergence of chronic non-communicable diseases in China. Lancet. 2008;372:1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Wang Y., Wu Y., Yang J., Wan X. The road to effective tobacco control in China. Lancet. 2015;385:1019–1028. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60174-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Wang Y., Zeng Y., Gao G.F., Liang X., Zhou M., Wan X., Yu S., Jiang Y., Naghavi M. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381:1987–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin S., Zhu X., Li R., Niu Y., Wang B., Zheng Z., Huang X., Huo L., Li J. Intervention-induced enhancement in intrinsic brain activity in healthy older adults. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:7309. doi: 10.1038/srep07309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Li J., Cuijpers P., Wu S., Wu Z. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms in Chinese older adults: a population-based study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2012;27:305–312. doi: 10.1002/gps.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y. Towards deeper research and better policy for healthy aging—using the unique data of Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. China Econ. J. 2012;5:131–149. doi: 10.1080/17538963.2013.764677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y., George L.K. Population aging and old-age care in China. In: Dannefer D., Phillipson C., editors. Sage Handbook of Social Gerontology. Sage publications; Thousand Oaks/CA/USA: 2010. pp. 420–429. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan H.J., Liu G., Guan X., Bai H.G. Recent developments in institutional elder care in China: changing concepts and attitudes. J. Aging Soc. Policy. 2006;18:85–108. doi: 10.1300/J031v18n02_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Li J. Gender and marital status differences in depressive symptoms among elderly adults: the roles of family support and friend support. Aging Mental Health. 2011;15:844–854. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.569481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu F.C., Meng F.Y., Li J.X., Li X.L., Mao Q.Y., Tao H., Zhang Y.T., Yao X., Chu K., Chen Q.H. Efficacy, safety, and immunology of an inactivated alum-adjuvant enterovirus 71 vaccine in children in China: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:2024–2032. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X., Chow E.P., Zhao P., Xu Y., Ling L., Zhang L. Rural-to-urban migrants are at high risk of sexually transmitted and viral hepatitis infections in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014;14:490. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.