Abstract

BACKGROUND:

National health care policy recommends that patients and families be actively involved in discharge planning. Although children with medical complexity (CMC) account for more than half of pediatric readmissions, scalable, family-centered methods to effectively engage families of CMC in discharge planning are lacking. We aimed to systematically examine the scope of preferences, priorities, and goals of parents of CMC regarding planning for hospital-to-home transitions and to ascertain health care providers’ perceptions of families’ transitional care goals and needs.

METHODS:

We conducted semistructured interviews with parents and health care providers at a tertiary care hospital. Interviews were continued until thematic saturation was reached. Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed to identify emergent themes via a general inductive approach.

RESULTS:

Thirty-nine in-depth interviews were conducted, including 23 with family caregivers of CMC and 16 with health care providers. Families’ priorities, preferences, and goals for hospital-to-home transitions aligned with 7 domains: effective engagement with health care providers, respect for families’ discharge readiness, care coordination, timely and efficient discharge processes, pain and symptom control, self-efficacy to support recovery and ongoing child development, and normalization and routine. These domains also emerged in interviews with health care providers, although there were minor differences in themes discussed.

CONCLUSIONS:

Although CMC have diverse transitional care needs, their families’ priorities, preferences, and goals aligned with 7 domains that bridged their hospital admission with reestablishment of a home routine. This research provides essential foundational data to engage families in discharge planning, guiding the operationalization of national health policy recommendations.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Hospital-to-home transitions are risky times for children with medical complexity. Health care policy recommends that families be actively involved in transitional care planning, but we lack family-centered approaches to effectively engage families of children with medical complexity in their transitional care.

What This Study Adds:

Several priorities reported by families for their children’s transitions differed from those previously reported among adults, including goals for normalization and ongoing development. This research may guide operationalization of health policy recommendations regarding transitions of care for children with medical complexity.

Adolescents and children with medical complexity (CMC) make up a diverse population with complex chronic medical conditions and severe functional limitations, necessitating involvement of multiple health care providers and high resource utilization.1–3 Although CMC represent a small proportion of the pediatric population, they account for 10% of hospital admissions, one-quarter of hospital days, and more than half of hospital readmissions, underscoring the importance of optimizing their outcomes and experiences of care.2,4

Hospital-to-home transitions are established risk periods, particularly for CMC.5,6 Recognizing the potential of transitional care interventions to reduce adverse events, national physicians’ organizations developed a Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement to address quality gaps.7 Aligning with the Institute of Medicine’s guiding principles for improving health care, a defining principle of the policy statement is patient and family engagement.8 Knowledge about families’ priorities and goals is essential to effective family engagement in planning for transitions, yet little is known about the issues of greatest relevance to families of CMC. To this end, our objectives were to examine the scope of preferences, priorities, and goals of parents of CMC regarding planning for hospital-to-home transitions and to ascertain health care providers’ perceptions of families’ transitional care needs.

Methods

Study Design

Given the paucity of past research in this area, we used qualitative methods to provide rich descriptions of parents’ and providers’ perspectives and to develop a conceptual framework to inform subsequent research and clinical initiatives.9 We conducted semistructured interviews with parents of CMC hospitalized at a tertiary care hospital in 2013 to 2014. We then conducted semistructured interviews with hospital- and ambulatory-based health care providers to characterize their perspectives about discharge planning issues they perceived to be most important to CMC and their families. We evaluated how the perspectives of these groups were consistent with each other, a method of triangulation applied in qualitative research to increase the validity of a study’s findings.10 In addition, to evaluate the validity and transferability of our results, we sought feedback from complex care providers at other hospitals; our modified member-checking methods and results are detailed in the Appendix.10,11

Study Population and Sampling Plan

CMC were defined as children with complex chronic conditions, severe functional limitations, and involvement of multiple health care providers and services.1 Eligibility criteria for parents included parent or guardian of CMC, age >18 years, and English speaking. Participants were purposefully sampled to represent diverse types of medical complexity (cancers, noncancer multisystem disease, and technology dependence), age groups, and both native and nonnative English speakers.12 Health care provider participants were purposefully sampled to include nurses, nurse practitioners, and nonresident physicians who worked with CMC in inpatient and outpatient settings. The Tufts Medical Center institutional review board provided study approval.

Procedures

A research team member approached parents meeting eligibility criteria during their child’s hospitalization to explain the study, request participation, and receive consent from parents and assent from adolescents (when applicable). Health care providers were contacted by e-mail to request participation.

Interview guides were developed by the research team and pilot-tested with parents and providers, not included in the final sample, to ensure that the questions were clear and elucidated comprehensive responses. During the pilot phase, interviews were conducted with parents during hospitalization and 1 to 2 weeks after hospital discharge. Given the rich data shared by parents during the in-hospital interviews about current and past hospitalizations and transitions, coupled with difficulties of scheduling time with parents after discharge due to significant time pressures reported by parents at this time, we elected to continue interviews during the child’s hospitalization only.

Interview questions focused on families’ priorities, preferences and goals related to planning for hospital-to-home transitions, potential barriers to successful discharge, social supports, and past hospital-to-home transition experiences (Table 1). After receipt of verbal consent, interviews were conducted in a private location in the hospital and audio recorded with permission. Participants received a $20 gift card to recognize their participation. Audio files were professionally transcribed and verified for accuracy.

TABLE 1.

Areas of Interview Inquiry

| Parent participants |

|---|

| 1. Was this hospital admission planned or unplanned? |

| 2. How has hospitalization affected your child and family? |

| 3. Do you feel as though you’ve participated in medical decision-making for your child during this hospitalization? |

| a. If yes, please tell me about this. |

| b. If no, would you like to be more involved in the medical decision-making for your child? |

| c. How would you like to be involved? |

| 4. When you’re admitted to hospital, when do you start thinking about going home? |

| 5. How would you like to be involved in planning your child’s discharge from the hospital? |

| 6. When you think about your child’s discharge from the hospital, what are your goals for your child and your family? |

| 7. We know that there are many changes that can happen when a child leaves the hospital to go home. What might prevent a smooth transition from the hospital to your home? |

| a. What things related to medical care might impact your transition home? |

| b. What family-related factors might impact your transition home? |

| c. Are there any factors related to home, school, or work that might impact your transition home? |

| 8. Who is available to provide support for you and your child when you go home? |

| 9. Does your child receive nursing services at home? If so, have you ever had a problem with home nursing services soon after you’ve been discharged from the hospital? |

| 10. In what ways might your child’s discharge impact the other people living in your home? (if applicable) |

| 11. What’s most important to you when you go home? |

| 12. Given that you know your child and your family the best, how would you plan their discharge from the hospital? |

| 13. Has your child ever had to be readmitted to the hospital shortly after you’ve gone home? If so, when you think back on this, could anything have been done prior to hospital discharge to prevent this? |

| 14. Has your child ever had a mistake in a medication at home that happened soon after their discharge from hospital? If so, when you think back on this, could anything have been done prior to hospital discharge to prevent this? |

| Health care provider participants |

| 1. What proportion of your practice time is spent working with CMC and their families? |

| 2. How would you describe your involvement with these children’s hospital-to-home transitions in the inpatient setting? Outpatient setting? |

| 3. Thinking about when these children are discharged from the hospital, what factors do you think have the greatest impact on their successful transition home from the hospital? |

| 4. In your experience, what is most difficult for families as they transition home from the hospital? |

| 5. What do you see as patients’ and families’ main goals for their hospital-to-home transitions? Are they unique to CMC? |

| 6. What could hospital-based health care providers do to improve families’ preparation for discharge and hospital-to-home transitions? |

| 7. How can hospital-based providers, including nurses, physicians, and other services, best support families in their hospital-to-home transitions? |

| 8. What resources provide support for families of CMC upon discharge? |

| 9. Thinking about the children and families that you care for, how do you think families should be involved in planning their discharge from the hospital? |

| 10. Is there anything else about discharge processes for CMC that you think would be helpful for us to hear? |

Analysis

Using open coding, an approach rooted in grounded theory, the research team reviewed transcripts to identify emergent concepts related to families’ priorities and goals for their hospital-to-home transitions. These concepts and associated definitions were summarized in a jointly developed codebook and coding framework.13,14 Two members of the research team then independently applied codes to one-quarter of the transcripts; areas of coding disagreement were resolved through in-depth discussions of the concepts, corresponding codes, and definitions. After assurance of coding agreement, transcripts were uploaded to Dedoose, a mixed-method data management and analysis program, and 1 member of the research team coded the transcripts, with coding audits performed by the principal investigator.15 Analysis was performed during the interview period, and interviews were continued until the research team agreed that no new relevant concepts or insights were emerging from the data (data saturation).10,12,16 This process was repeated for analysis of the provider interviews, beginning with the parent interview codebook and identifying additional emergent concepts. After open coding of all interviews, all codes and associated transcript excerpts were reviewed by the research team to group similar concepts into themes. Similar themes were then grouped into domains.

Results

After completion of 23 interviews with parents and 16 interviews with health care providers, the research team agreed that data saturation had been achieved; this sample size is within the range suggested by qualitative methods guidelines.12,16,17 The majority of family participants were mothers, and participants reported diverse race or ethnicity and educational attainment. Half of the health care provider participants worked primarily in inpatient settings and half worked primarily in outpatient settings, including primary care and specialty practices (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Parent Participants, Their Children, and Health Care Providers

| n (%) or Median [Interquartile Range] | |

|---|---|

| Parent characteristics (n = 23) | |

| Relationship to child | |

| Mother | 19 (82.6%) |

| Father | 4 (17.4%) |

| Age, y | 38 [33–45] |

| Race or ethnicitya | |

| White | 11 (50.0%) |

| Hispanic | 8 (36.4%) |

| Other | 3 (13.6%) |

| Marital statusa | |

| Single | 10 (43.5%) |

| Married | 7 (31.8%) |

| Divorced or separated | 5 (22.7%) |

| Native languagea | |

| English | 17 (77.3%) |

| Other | 5 (22.7%) |

| Educational attainmenta | |

| High school completion or less | 3 (13.6%) |

| College initiated or completed | 17 (77.3%) |

| Postgraduate degree or higher | 2 (9.1%) |

| Child characteristics | |

| Age, y | 5.5 [1.3–13.5] |

| Sex (% female) | 10 (43.5%) |

| Technology dependentb | 15 (65.2%) |

| Primary payerc | |

| Private insurance | 5 (27.8%) |

| Public insurance | 13 (72.2%) |

| Had hospitalization in year preceding index hospitalization (yes) | 19 (82.6%) |

| Number of hospitalizations in year preceding index hospitalization | 2 [1–4] |

| Health care provider characteristics (n = 16) | |

| Profession | |

| Nurse | 4 (25%) |

| Nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant | 3 (19%) |

| Physician (specialty) | 9 (56%) |

| Primary care provider | 3 (33%) |

| Hospitalist | 2 (22%) |

| Specialist | 4 (44%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 13 (81%) |

| Primary practice setting | |

| Primarily inpatient-based | 8 (50%) |

| Primarily outpatient-based | 8 (50%) |

Missing for 1 participant.

Defined as home use of any of the following: gastrostomy tube, jejunostomy tube, central line, tracheostomy, ventilator, ventricular shunt, ostomies, or dialysis.

Missing for 5 participants.

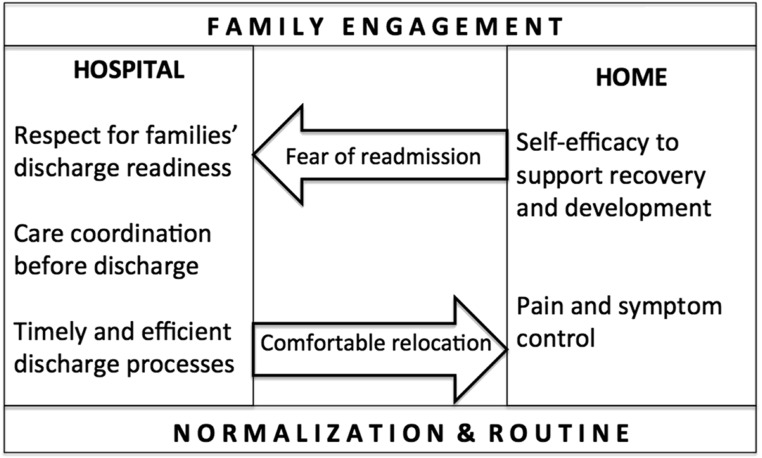

Families’ priorities, preferences, and goals for their hospital-to-home transitions aligned with 7 domains: family engagement, respect for families’ discharge readiness, care coordination before discharge, timely and efficient discharge processes, pain and symptom control, self-efficacy to support recovery and development, and normalization and routines. Figure 1 provides a conceptual framework illustrating how these domains bridged the hospital and home settings. Comfort during transport home was discussed in the context of pain and symptom control, and fear of readmission was discussed in the contexts of discharge readiness and self-efficacy to support recovery and development. Two domains, family engagement and families’ desire for normalization and routine, spanned both hospital and home settings. The perspectives of parents and providers were largely consistent with each other; all 7 domains emerged in analysis of both parent and provider interviews, with minor differences in some themes as detailed below. Table 3 summarizes themes associated with each domain and associated representative quotes. These results were endorsed as valid and transferable by providers working at other hospitals (Appendix).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework illustrating 7 domains regarding parents’ priorities and goals for their hospital-to-home transition.

TABLE 3.

Domains, Associated Themes, and Representative Quotes From Parents and Health Care Providers Regarding Transitional Care Priorities and Goals

| Domain and Themes | Representative Quotes From Parents | Representative Quotes From Health Care Providers |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1. Family engagement | “We’re the best advocates for her. Sometimes they’ll make decisions, and we’ll ask them either to wait a day, hold off on it, or slow down the amount of what they want to do.” | “My philosophy is that you involve them in all the decision making. . . . And I think that makes them feel a lot more participatory, that they have some power here, and then they pick up the ball and they take on more responsibility.” |

| Themes | “With my son’s condition, it’s a very lengthy process, so being involved is really—it’s really important. It’s not just a simple in and out and then he’s done and he’s going on with the rest of his life.” | “Sometimes it’s a challenge when the families have a very strong agenda . . . in medical recommendations and home goals.” |

| (a) Advocacy for their child | “I feel like they definitely could have talked to us more. We were literally just in the room alone like 90% of the day, just . . . waiting for answers, for anything.” | “It’s okay for a family to say, ‘I don’t agree with you.’ And to ask, ‘Okay, can you help me understand why you don’t agree with me?’ . . . In health care we hear that and automatically we’re guarded.” |

| (b) Parents’ role in decision-making | “We do a lot of work with the family . . . being part of the rounding in the mornings. But what happens the rest of the day? How do you keep that thread? We just do it in the morning. . . . All that time, you know, is sort of lost in between. . . . It’s just a very difficult place to be and I don’t know if I could do it. I don’t know if I could sit there and wait for hours for lab values that may change the plan.” | |

| (c) Communication with health care team | ||

| Domain 2. Respect for families’ discharge readiness | “It’s not even on our radar right away. For him, he was probably here 4 days before I saw him improving and felt like then we could start thinking about it.” | “A lot of these families plan on discharge right when they walk in. How long? That’s the first question. How long am I going to be here? What do you think?” |

| Themes | “I don’t think home until she comes out of the PICU. Then the thoughts are like, okay, if we can go to the floor, I can do this at home. . . . When she comes to the floor is when I start thinking, okay, we’re getting ready.” | “I want families feeling like they’re being heard and . . . when they leave, that they are really feeling good about it, that they’re not leaving with reservations in their minds or concerns.” |

| (a) Varied readiness to discuss discharge | “I’m feeling like the issues that have concerned me during this admission are not resolved but then feeling like I’m being pushed out the door anyways.” | “I think they always want 1 more day and it is really hard to be like, ‘Okay you do have to go.’ A lot of them need respite.” |

| (b) Respect for families’ perspectives | “I feel like making sure that all the goals, as long as they’re attainable, are met so you’re not left going home with 1 thing not reached and then having a downfall and having to come back—it’s happened to us before” | |

| (c) Fear of readmission | ||

| Domain 3. Care coordination | “If there’s a question, who am I actually going to call? Is it the nurse that discharged me? Is it the cardiologist? Is it the intern?” | “Follow up with these chronic families. Make a call the next day. How are things going, how was your first night? Just to make them feel like you know . . . we’re still connected. I’m not doing this alone. I think that makes all the difference in the world. Making a follow-up just to make sure. Is there anything we should have done differently? What can we change to make tonight a better night? How can we help you more so you don’t wind up back in the hospital?” |

| Themes | “Usually, when you’re discharged from a hospital, you’re not up to par quite yet. You still take another day or 2, so any appointments that have been scheduled for the next 2 days after discharge, you usually cancel. . . . Or physical therapies or any of those, you have to cancel because she’s not up to par to getting out and doing that. I think that’s a disruptive piece.” | “Sometimes they find it very frustrating when they won’t get a phone call back or ‘Oh, it’s not our problem anymore, call your PCP.’ Some kids don’t have a PCP because they’re so complex that they don’t have one person that oversees everything.” |

| (a) Transportation | “But with the total parenteral nutrition company, which is really important, we didn’t have anything set up. . . . We were told that we had to just call the . . . 1 800 number we had to get orders like rushed to us. . . . That was probably 1 of the most stressful nights we’ve ever had. . . . It was crazy because it was our first night home and it’s like, what if something goes wrong? It was just a nightmare. Stuff didn’t even come until the next day. It was all late the next day. It was just a nightmare.” | “Many times they have a chronic illness, so there’s a slew of appointments, and they have competing demands. You’ve got parents who may have other children and have to be present for that. What’s realistic, you know, because to be in a hospital setting 3 or 4 times a week, or even 3 times a week, it’s demanding.” |

| (b) Medication, equipment, and supplies | “Make sure that the equipment and everything is there before that patient comes home. . . . Simple things like that I think would make a world of difference . . . just simple little basic things.” | “Initially everything is just so overwhelming. They don’t know who their home care company is; they just know that something shows up. They don’t know whom to call if they run out of formula or whatever, all those things are factors, major factors.” |

| (c) Follow-up after discharge | ||

| (d) Home environment | ||

| Domain 4. Timely and efficient discharge processes | “I would plan it for as early in the day as you could versus late afternoon, evening just because again, that whole window of getting reacclimated to home. It’s better if you have a better part of the day to kind of reestablish that before it’s just time to go to bed at night.” | “Everyone goes home at night, and anxiety is higher at night. . . . We don’t think of these things. They are running around filling prescriptions. When they get their child home it is 6:00, 7:00 at night and then they are paging everyone all night long. . . . Everybody wants to be out early, and I think having more daylight hours and knowing that they have still someone at home, a lifeline to help them. . . . Everyone always has a question.” |

| Themes | “I think the biggest thing for us because we’re so far from home is just going to be adequate time. I mean not finding out that morning that we’re going home that afternoon. That’s big. Just having time to plan and really sitting down with someone.” | “We never ask, Do you have a preference of when to be discharged? We do it around our schedule. When we get around to rounding and when the residents get around to writing the orders.” |

| (a) Time of day | “That kind of last hurdle stuff of actually physically leaving the building, that’s usually the . . . most frustrating. . . . Once you’re told you can go home, usually we’ve been here for a number of days. So we really want to go home and then it’s that last few hours where they say, ‘Okay, you’ll probably get released around noon’ and then it’s 2 o’clock or it’s 3 o’clock.” | “The discharge process . . . I’ve heard over and over again, is very . . . muddy, complicated, long. They just want to get out, you know what I mean?” |

| (b) Discharge processes | ||

| Domain 5. Pain and symptom control | “I would just hope that the ride would be smooth and comfortable for her, and she’s not in any pain whatsoever, and that we can make it there safely.” | “Make sure they have a good pain management protocol and an expectation on how the pain should improve after the surgery or admission.” |

| Themes | “I know bumps in the road after surgery are very uncomfortable, especially where she had an operation on her neck.” | “I think they want the kids to be well—it’s the quality of their life, do you know what I mean? These are complicated kids. They don’t want their kids to be in pain, I’m sure. . . . They want their quality of life to return to baseline, to where it was. I think that’s their goal.” |

| (a) En route home | “You want to know and understand how they’re feeling, and a lot of times when they’re younger, they can’t communicate effectively to you what’s going on.” | |

| (b) At home | ||

| Domain 6. Self-efficacy to support recovery and development | “Like a couple years ago when she first got her central line, really making sure the parents going home were super comfortable with their new regimen. It was going to change everybody’s life, not just the patient’s. . . . Probably giving me a little more time and having the nurses oversee me do it in front of them instead of me watching them do it.” | “The most difficult thing for them is that they suddenly have gone from a very, very controlled environment where there’s lots of monitors and lots of people watching their baby, to them being all alone and feeling resource poor and vulnerable.” |

| Themes | “I’m a person who needs to know information. I will sit on Google for hours and try to find out information. So if that was in the discharge paperwork, I definitely would pay attention to it, and it’s usually not.” | “So knowing where they’re at and knowing what they can do independently for self-care, you know, the ability to have self-efficacy. . . . I think sometimes we assume too much, that they’re able to do too much.” |

| (a) Recovery from acute illness | “To be just tolerating her feeds, steadily maintaining and gaining her weight. . . . She’s slightly developmentally behind just because she’s been in a hospital all her life, but we can sense she’s so smart.” | “With the teenagers particularly, it’s getting them on board to buy into everything they need to do, just the whole learning curve with any child, getting the parents to understand . . . what are the side effects of treatment? What are you watching for? You have to have them really totally bought into that.” |

| (b) Ongoing development | ||

| Domain 7. Social reintegration and establishment of normal routines | “The transition home for him, it’s more of getting back into the at-home routine versus the hospital routine—bedtimes, baths, teeth brush. It’s very regimented at home and so for a reason, but that kind of all goes out the window when we come in here.” | “What is your normal routine at home, and how can we maintain it? Because that’s a goal they really have going into the hospital and transitioning home.” |

| Themes | “What’s important for me when we go home is just that he gets back into doing as much normal things that he can do as a kid his age.” | “When they are very well organized, they sort of have a mental model on how they manage things. . . . Their life came to a halt, they have other responsibilities, they just want to go to what they need to do and get back on the bandwagon.” |

| (a) Impact of hospitalization on routine | “We have to come together. Right now we’re in our 4 corners. So part of her coming home and getting back into our regular routine will help us come back and be together.” | “I think their goal is to get home and . . . have as normal a routine at home and get their child back into socially back to their baseline.” |

| (b) Return to activities | “Just a million and 1 kind of things that you, normally in everyday life, just take for granted as part of your normal day. . . . It’s hard to put into words. Everything is in the context of him and his illness, so it’s like everything else takes a back seat, and that’s fine, but there’s still things that have to be dealt with. You ultimately have to find time to prioritize right, if you can. A lot of times, mentally, you’re out of it.” | “Cultural competence is the most important thing. Because we take care of patients from all kinds of communities, and every community has some very different ways of handling this.” |

| (c) Hospital as a “second home” | “We are a small family of 4 . . . and we have no real family supports. . . So it’s been difficult trying to manage the schedule for my other son. . . . That’s been the biggest stress.” | “I think, some of the problems we have with families who come in and aren’t doing so well mentally anymore because they’ve just lost sight of who they are as an individual. We know that is part of compassion fatigue and caregiver fatigue. . . . There’s not enough respite care to really allow for that regeneration of the spirit.” |

| (d) Respite care | “It’s hard, but I mean at the same time, we’re used to it because [the hospital is] like a second home . . . right now for her. But I mean there’s really nothing you can do about it.” |

PCP, primary care provider.

Family Engagement

Themes in this domain included parents’ desire to advocate for their child, parents’ role in medical decision-making, and communication with the health care team (Table 3). Several parents indicated that although they entrusted medical decision-making to health care providers, they valued opportunities to share their own knowledge and perspectives. Parents described how their ability to participate in their child’s care varied across members of the health care team: “The attendings and senior [residents] are much more willing to let me make some choices. The first years are pretty tunnel-visioned as to the plan.” Providers also described how family engagement was central to transitional care, stating, “Families have a bigger picture of things.”

Respect for Families’ Discharge Readiness

Themes in this domain included varied readiness to discuss discharge plans, respect for families’ perspectives, and fear of readmission (Table 3). In describing readiness to discuss discharge planning, 1 parent reported, “It’s not even on our radar right away,” stating that her priority was medical stabilization early in the hospitalization. Other parents described how their children’s changing clinical status made conversations about discharge planning challenging, with 1 parent stating, “Don’t tell me a date, because that date will come and go.” Some parents described feeling “pushed out the door” without their primary concerns being addressed. Although many described eagerness for discharge, they also described fear of readmission, with 1 parent stating, “I think it would be hard to go home and end up having to come right back.” Providers emphasized the importance of considering parents’ perspectives on discharge readiness, yet they acknowledged that this was done inconsistently.

Care Coordination Before Discharge

Themes in this domain included transportation arrangements; medication, equipment, and supplies; home environment; and follow-up after discharge (Table 3). Parents described their desire to have supplies and equipment appropriately set up in the home before discharge, describing missing supplies after discharge as “the most stressful experience of my life” and “a nightmare.” Parents also shared their challenges with knowing whom to call with questions after discharge, stating, “They always say, ‘If there’s any problem, call her primary care physician.’ She’s very complex . . . she’s only seen her one time in her life.” Health care providers emphasized the importance of ensuring that “the door was always open” after hospital discharge. Providers also discussed the relevance of the home environment to effective care coordination, a theme not discussed by parents. One provider stated, “In winter, I always ask them if they have heat because this is something we take for granted. . . . They may not have a phone to call their doctor.”

Timely and Efficient Discharge Processes

Themes in this domain included discharge time of day and discharge processes. Several parents described the value of discharge early in the day, allowing them to “have a better part of the day” to “get settled” at home. Parents also reported a desire to help plan their discharge time, and they reported examples of discharge times occurring several hours later than anticipated: “I know there’s never really a set time. But we were told that we’d probably be out of here by noon at the latest, hopefully 10:30 to 11:00. We didn’t leave until like 7:30 to 8:00 that night.” Parents also described fragmented and harried discharge processes, with 1 participant stating, “Everything felt rushed . . . we literally felt rushed out the door. The nurse came in, read the thing, ba-ba-bam, and then we were out. It’s like, ‘Okay, well I guess we’re going home now.’”

Similarly, providers discussed the relevance of discharge time of day to parents, stating, “Everyone goes home at night and anxiety is higher at night. . . . We don’t think of these things.” Another stated, “We never ask, ‘Do you have a preference of when to be discharged?’ We do it around our schedule. When we get around to rounding and when the residents get around to writing the orders.” Providers echoed the perspective of parents that discharge processes feel rushed, with 1 provider stating, “Everybody is rushed. Everyone has a place to be. And I think the families feel that.”

Pain and Symptom Control

Themes in this domain included pain and symptom control en route home from the hospital and pain and symptom control at home. In discussing pain control en route home, 1 parent stated, “I’m afraid. . . . I have a long way to go home.” Pain control at home was frequently discussed, with 1 parent stating, “I’m just praying that she’s not in a lot of pain all the time.” In contrast, health care providers discussed only the importance of pain and symptom control in the home environment.

Self-Efficacy to Support Recovery and Development

In this domain, participants discussed the importance of knowledge, skills, and support for acute illness recovery and ongoing child development. Parents described the importance of understanding how to administer feeds, assess feeding tolerance, and manage medical equipment. Specific, individualized written materials and teaching were described as integral to families’ transitions by both parents and providers; providers described the importance of “really helping parents understand what to expect and setting out a realistic course.” With respect to ongoing child development, parents prioritized their child’s growth, weight gain, and emotional and physical development (Table 3).

Normalization and Routine

Themes in this domain included impact of hospitalization on families’ routines, goals for social reintegration after discharge, the hospital as a “second home,” and respite care. The disruption to normal routine that resulted from hospitalization was a prominent theme, with 1 parent stating, “Routine . . . is critical. You lose a lot of the routine when you come in here because it’s not your routine. It’s the routine of the floor or the routine of the nurse.” Parents described specific challenges with monitors and alarms; 1 parent stated, “The alarms are probably my biggest nightmare here to be honest. . . . Sometimes when they go off, it seems like an eternity.” Parents reported challenges with schedules for feeding, medication, and activities of daily living, reporting, “I think it would make people feel better if they could say, ‘Hey, We’d like to do a bath around this time. We’d like to do this around that time’ and then take all that information . . . and plot out a plan.” Parents also discussed challenges with balancing the needs of their CMC and other job and family responsibilities (Table 3).

Health care providers also discussed the value families place on routine, describing families’ “loss of control” in the hospital and discharge as an opportunity to “get that control back.” Providers described the importance of discussing this topic with parents, recommending the probe, “What is your normal routine at home, and how can we maintain it?” Providers discussed respite care as a potential change in routine and opportunity for parents to focus on themselves and other family members, a theme not discussed by parents (Table 3).

Discussion

We found that families’ priorities and goals for planning their hospital-to-home transitions aligned with several domains that bridged the hospital and home settings, with family engagement and respect for families’ normal routines fundamental to family-centered transitional care. Several studies among adults have illustrated associations between patient engagement in planning for transitions and improved health outcomes.7,18–21 Recognizing that CMC account for a disproportionate share of pediatric hospitalizations and adverse outcomes after discharge, the results of this study may be used to inform analogous transitional care interventions for hospitalized children.

Two previous qualitative studies have explored hospital-to-home transitions in pediatric populations, with 1 concluding that high-quality transitions for CMC may require additional supports beyond those needed by otherwise healthy children.22,23 Our findings, focused specifically on CMC and reflecting the perspectives of both parents and health care providers, summarize the domains of greatest value to families of CMC. Similar to the qualitative research that has informed adult transitional care interventions, parents in our study reported the importance of engagement and empowerment to advocate for their child.24,25 Families’ desires for care coordination and discharge teaching tailored to their specific needs are consistent with the goals of individualized transitional care plans previously studied in adult populations.18,26 Though not typically included in transitional care bundles, the feasibility of hospital discharge early in the day, endorsed by parents in our study, has been demonstrated in adult populations through multidisciplinary efforts.27–29

In contrast, 2 domains emerging in our research, families’ prioritization of normal routines and their desire to support ongoing child development concurrent with acute illness recovery, differ from the results of previous studies in both general pediatric and adult populations. These findings may reflect the special health care needs of CMC and the unique challenges experienced by their families. Several previous studies conducted in outpatient populations of CMC have established the importance of normalization, defined as a family’s adjustments to meet their children’s special health care needs and other family responsibilities in ways that support as normal a family life as possible, in successful coping and parental mental health.30–32 Similarly, families’ desire to support ongoing child development concurrent with illness recovery is a pediatric-specific theme that aligns with parents’ goals in outpatient settings.33–35

The central themes of family engagement and normalization identified in this work have important implications for subsequent transitional care interventions. Although several studies in adult populations illustrate associations between family engagement and improved health outcomes, pediatric studies evaluating family engagement in hospital settings are limited.7,18–21 Future interventions to improve family engagement in pediatrics, informed by this research, could include education to improve communication with families regarding their transitional care priorities and structured evaluations of families’ needs and readiness for transitional care. Supporting families’ normal routines both during hospitalization and after hospital discharge may also improve hospital-to-home transitions for CMC. Such initiatives could include involvement of families in planning schedules for medications and other therapies and interventions to reduce the frequency of false-positive alarms and sleep disruptions.36,37

Our results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, our results reflect the perspectives of parents and providers at 1 hospital. However, several of our findings were consistent with previous research conducted in adult populations and outpatient settings, and the validity and transferability of our work are supported by the convergence of domains identified in the parent and provider interviews and by the results of member-checking with health care providers who care for CMC at other hospitals (Appendix). Second, although we purposefully oversampled parents who reported that English was not their native language (25% of our sample) by excluding parents who did not speak English, we may have missed themes of particular importance to non–English-speaking families. Finally, we conducted interviews with parents only during their child’s hospitalization and not in outpatient settings; during our pilot phase we found that postdischarge interviews in outpatient settings were more difficult for parents, reinforcing how stressful these transitions may be for families. Subsequent research to more fully characterize families’ perspectives during the postdischarge period may yield additional domains related to ambulatory care.

Conclusions

Although CMC have diverse transitional care needs, their families’ priorities, preferences, and goals aligned with domains that bridged their hospital admission with reestablishment of home routines. Families prioritized effective family engagement with the health care team and desired normalization both during hospitalization and after hospital discharge. This research provides a pediatric-specific framework to engage families in planning for hospital-to-home transitions and to inform operationalization of national health policy recommendations.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Academic Pediatric Association Research Scholars Program scholars and faculty for supporting this work, and particularly Dr Janice L Hanson, University of Colorado School of Medicine, for her thoughtful critique of this manuscript. We also acknowledge Dr Norah Emara, Tufts Medical Center, for conducting some of the family interviews.

Glossary

- CMC

children with medical complexity

APPENDIX: Modified Member Checking Procedures to Assess the Validity and Transferability of Results

Methods

Because our interviews were conducted at 1 hospital, we surveyed health care providers experienced in providing care to CMC at 3 other tertiary care hospitals regarding the validity and transferability of our findings. Member-checking is defined as a process of taking data and interpretations back to the participant group; we used a modified approach in which we brought the findings to an analogous group of providers working at other hospitals to evaluate transferability and validity.10,11

All participants had been previously nominated as experts in providing care to CMC to participate in an expert elicitation process to prioritize quality improvement interventions for CMC.36 Ten potential participants were contacted by e-mail to request participation; all agreed to participate. Participants were provided with the study abstract and the summary of domains, themes, and representative quotes from parents and health care providers (Table 3). They were asked to report whether the study findings rang true to them as health care providers working at other hospitals (“yes,” “no,” or “unsure”), to describe the ways that the results seemed transferable, and what components of families’ priorities and preferences regarding their hospital-to-home transitions were missing, from their perspectives. Participants were provided with a link to an online data collection tool to provide feedback in an anonymous, deidentified manner. Up to 2 e-mail reminders were sent to request completion of this survey. No incentives were provided. Responses to the free-text questions were analyzed via conventional qualitative content analysis, in which responses were categorized as confirming the validity and transferability of results as presented and additional considerations regarding families’ priorities and preferences across the 7 domains.37

Results

All 10 health care providers who were contacted to request participation completed the online data collection tool, including 4 physicians (1 pediatric hospitalist, 1 pediatric specialist, 1 outpatient complex care provider, 1 primary care provider), 3 nurses, 1 nurse practitioner, 1 social worker, and 1 family navigator. Five participants worked primarily in inpatient settings, and 5 participants worked primarily in outpatient settings.

All participants reported that the study findings rang true to their experience working with CMC at other hospitals. Representative quotations from the free-text responses are shown in Supplemental Table 4, including comments about how the results seemed valid and transferable, and additional considerations not discussed in our original analysis. Participants’ free-text responses emphasized the importance of respect for families’ discharge readiness, care coordination, and timely and efficient discharge processes. Additional considerations raised by respondents as missing from our original results included balancing families’ needs with the hospital’s needs with respect to bed availability, acute care hospital-to-rehabilitation hospital transitions, and variation in postdischarge resources for pain management.

Footnotes

Dr Leyenaar conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the results, and drafted the initial manuscript; Ms O’Brien conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed the results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Leslie, Lindenauer, and Mangione-Smith conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to analysis of results, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Dr Leyenaar was supported by a grant from the Deborah Munroe Noonan Memorial Fund and the Tufts Pilot Studies Program, supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), award UL1TR001064. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Cohen E, Kuo DZ, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity: an emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simon TD, Berry J, Feudtner C, et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon TD, Cawthon ML, Stanford S, et al. ; Center of Excellence on Quality of Care Measures for Children with Complex Needs (COE4CCN) Medical Complexity Working Group . Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/6/e1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals [published correction appears in JAMA. 2013;309(10):986]. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh KE, Roblin DW, Weingart SN, et al. Medication errors in the home: a multisite study of children with cancer. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/131/5/e1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. ; American College of Physicians; Society of General Internal Medicine; Society of Hospital Medicine; American Geriatrics Society; American College of Emergency Physicians; Society of Academic Emergency Medicine . Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians–Society of General Internal Medicine–Society of Hospital Medicine–American Geriatrics Society–American College of Emergency Physicians–Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5 pt 2):1101–1118 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creswell JW, Miller DL. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract. 2000;39(3):124–130 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seltz LB, Preloger E, Hanson JL, Lane L. Ward rounds with or without an attending physician: how interns learn most successfully. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(7):638–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seidel JV. Qualitative data analysis. 1998. Colorado Springs, CO: Qualis Research; Available at: www.qualisresearch.com/DownLoads/qda.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dedoose Version 5.0.11, Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data. Los Angeles, CA: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morse JM. Determining sample size. Qual Health Res. 2000;10(1):3–5 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balaban RB, Weissman JS, Samuel PA, Woolhandler S. Redefining and redesigning hospital discharge to enhance patient care: a randomized controlled study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1228–1233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koehler BE, Richter KM, Youngblood L, et al. Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desai AD, Durkin LK, Jacob-Files EA, Mangione-Smith R. Caregiver perceptions of hospital to home transitions according to medical complexity: a qualitative study. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(2):136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solan LG, Beck AF, Brunswick SA, et al. ; H2O Study Group . The family perspective on hospital to home transitions: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/136/6/e1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimmer KA, Moss JR, Gill TK. Discharge planning quality from the carer perspective. Qual Life Res. 2000;9(9):1005–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Eilertsen TB, Thiare JN, Kramer AM. Development and testing of a measure designed to assess the quality of care transitions. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2(June):e02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(12):999–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kravet SJ, Levine RB, Rubin HR, Wright SM. Discharging patients earlier in the day: a concept worth evaluating. Health Care Manag (Frederick). 2007;26(2):142–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wertheimer B, Jacobs REA, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wertheimer B, Jacobs REA, Iturrate E, Bailey M, Hochman K. Discharge before noon: effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):664–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knafl KA, Deatrick JA. The challenge of normalization for families of children with chronic conditions. Pediatr Nurs. 2002;28(1):49–53 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toly VB, Musil CM, Carl JC. Families with children who are technology dependent: normalization and family functioning. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(1):52–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carnevale FA, Alexander E, Davis M, Rennick J, Troini R. Daily living with distress and enrichment: the moral experience of families with ventilator-assisted children at home. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/117/1/e48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sices L, Egbert L, Mercer MB. Sugar-coaters and straight talkers: communicating about developmental delays in primary care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/124/4/e705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiks AG, Mayne S, Hughes CC, et al. Development of an instrument to measure parents’ preferences and goals for the treatment of attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(5):445–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forsingdal S, St John W, Miller V, Harvey A, Wearne P. Goal setting with mothers in child development services. Child Care Health Dev. 2014;40(4):587–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stickland A, Clayton E, Sankey R, Hill CM. A qualitative study of sleep quality in children and their resident parents when in hospital. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(6):546–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karnik A, Bonafide CP. A framework for reducing alarm fatigue on pediatric inpatient units. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(3):160–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]