Abstract

Phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF) is a form of hypoxia-induced spinal respiratory motor plasticity that requires new synthesis of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and activation of its high-affinity receptor, tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB). Since the cellular location of relevant TrkB receptors is not known, we utilized intrapleural siRNA injections to selectively knock down TrkB receptor protein within phrenic motor neurons. TrkB receptors within phrenic motor neurons are necessary for BDNF-dependent acute intermittent hypoxia-induced pLTF, demonstrating that phrenic motor neurons are a critical site of respiratory motor plasticity.

Keywords: phrenic, motor neuron, plasticity, intermittent hypoxia, RNA interference, TrkB

Introduction

Neuroplasticity has long been associated with conscious memory formation and motor learning in mammals (Ramón y Cajal, 1907; Hebb, 1949; Bliss and Lomo, 1973; Bailey et al., 1996), but has only recently been appreciated in the neural system controlling breathing (Mitchell and Johnson, 2003; Feldman et al., 2003). Although several examples of spinal motor neuron plasticity exist in invertebrate motor systems (Glanzman, 2009; Kandel and Tauc, 1965a,b), mammalian motor neurons have traditionally been portrayed as inflexible relays between the brain and muscles actuating movements (Eccles and Sherrington, 1930).

One stimulus for eliciting respiratory plasticity is low oxygen (hypoxia), such as the carotid body plasticity observed following sustained or intermittent hypoxia (Kumar and Prabhakar, 2012), and spinal motor plasticity following acute intermittent hypoxia (AIH; Bach and Mitchell, 1996; Baker and Mitchell, 2000). Although spinal respiratory motor plasticity is suspected to arise from cellular mechanisms within respiratory motor neurons (Baker-Herman and Mitchell, 2002; Mitchell et al., 2001; Feldman et al., 2003), this hypothesis has not been adequately tested. Previous work using adeno-associated viruses to deliver TrkB protein to phrenic motor neurons demonstrated that phrenic motor neuron TrkB expression promotes recovery following C2 spinal hemisection (Mantilla et al., 2013; Gransee et al., 2013), but this study did not evaluate other, non-injury related forms of phrenic motor plasticity.

Considerable effort has been focused on understanding cellular and synaptic mechanisms of AIH-induced phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF), and we know that it: 1) is initiated by spinal, serotonin type 2 receptor activation (Baker-Herman and Mitchell, 2002; Fuller et al., 2001; Kinkead et al., 1998; MacFarlane et al., 2011); 2) requires protein kinas C-θ activity within phrenic motor neurons (Devinney et al., 2015); 3) requires new synthesis of spinal brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; Baker-Herman et al., 2004); and 4) requires ERK/MAP kinase signaling (Hoffman et al., 2012). Although new BDNF synthesis is necessary and sufficient for AIH-induced pLTF (Baker-Herman et al., 2004), the involvement of its high affinity receptor, tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB), has not been conclusively demonstrated. Previous studies used a non-selective drug (K252a; Baker-Herman et al., 2004) to block tyrosine kinase activity throughout the cervical spinal region, and the cell type hosting the relevant BDNF/TrkB signaling could not be determined. Here, we tested the hypothesis that that phrenic motor neuron TrkB protein expression is necessary for BDNF-dependent phrenic long-term facilitation following AIH. We demonstrate that intrapleural administration of siRNAs targeting TrkB mRNA knocks down TrkB protein in the phrenic motor nucleus, but not in nearby spinal regions expected to contain pre-phrenic interneurons. Since, TrkB knock-down with intrapleural siRNAs abolishes AIH-induced pLTF, AIH-induced pLTF results from spinal motor neuron plasticity.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (2–5 months old; colony 218A, Harlan; Indianapolis, IN) were studied. Rats were double-housed with food and water ad libitum, a 12h light/dark cycle with controlled humidity and temperature. The University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal procedures/protocols.

siRNA and Cholera Toxin B fragment delivery

siRNAs were prepared per manufacturer instructions (Dharmacon Inc). Pools of four Accell-modified siRNA (21 base pairs) duplexes targeting different mRNA sequences were used; each duplex was either non-targeting (siNT) or targeting TrkB (siTrkB). siTrkB duplexes targeted the following sequences: GCUUAAAGUUUGUGGCUUA, CUAAUGGCCAAGAAUGAAU, GUAUCAGCUAUCAAACAAC, and GCACCAACCAUCACAUUUC. Accell-modified siRNAs were used because they preferentially transfect neurons (Nakajima et al., 2012).

Each pool was suspended in Dharmacon siRNA buffer at a concentration of 5μM, aliquotted and stored at −20°C. Prior to intrapleural injections, 20μl of siRNA was added to 6μl of 5X siRNA buffer (Dharmacon), 3.2μl of Oligofectamine Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen), 0.8 μl of RNAase free H2O (final siRNA concentration of 3.33 μM) and mixed for 20 min prior to injection, thus enabling siRNAs to complex with the transfection reagent.

Cholera toxin B (CtB) fragment and siRNAs were injected intrapleurally similar to earlier reports to respectively back-label phrenic motor neurons (Mantilla et al., 2009) and induce RNA interference (Mantilla et al., 2013). Anesthesia was induced with 5% isoflurane in 100% O2, and then maintained via nose cone (3.5% isoflurane, 100% O2). 12.5μl of CtB (2μg/μl in sterile H2O) was loaded into a 25μl Hamilton syringe attached to a 6mm sterile needle before bilateral injections (2×12.5μL of 2μg/μL total) at the 5th intercostal space anterior axillary line 7 days prior to tissue harvest. Intrapleural siRNAs were delivered daily as 30μl injections bilaterally (2×30μL of 5μM siRNA) from a 50μl Hamilton syringe 3, 2 and 1 day prior to tissue harvest or neurophysiology experiments (outlined in Figure 1A). This technique was adapted from previous reports using intrapleural siRNA injections to knockdown gene expression within phrenic motor neurons (Mantilla et al., 2013; Devinney et al., 2015). After injections, isoflurane was discontinued and chest movements were monitored for signs of distress and/or pneumothorax (none observed). Rats were housed and monitored daily until used for neurophysiology or immunohistochemistry (IHC) experiments.

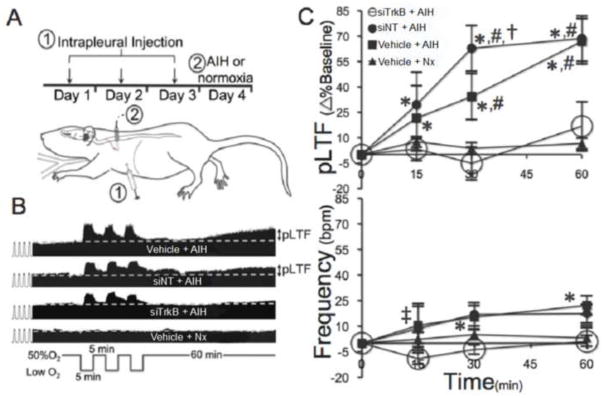

Figure 1.

Intrapleural siTrkB injections abolish pLTF. A) After siTrkB, siNT or vehicle injections (1), rats were given either Nx or AIH, and assessed for pLTF (2). B) In compressed phrenic neurograms, rats given vehicle (top) or siNT (second trace) exhibit pLTF following AIH; in contrast, rats receiving siTrkB (third trace) did not express pLTF following AIH. Control trace of rats receiving intrapleural vehicle injections without AIH (bottom) also did not exhibit pLTF. C) AIH increases phrenic burst amplitude in control (■; n=11) and siNT rats (●; n=5), but not siTrkB rats (○; n=7), relative to Nx (▲; n=9) controls 60-min post-AIH. D) AIH elicited small increases in frequency within vehicle (■) and siNT (●) rats (versus baseline), but not siTrkB rats (○). Mean values ± 1S.E.M. * vs baseline (p < 0.001); # vs vehicle + Nx at same time point (p<0.02); † vs vehicle + AIH at same time (p<0.001).

Experimental groups

Four rat groups were studied for neurophysiology experiments: 1) siTrkB + AIH (n=7); 2) siNT + AIH (n=5); 3) vehicle +AIH (n=11); 4) vehicle + normoxia (Nx). Normoxia control groups experienced persistent ventilation with normoxia air (50% O2 + 2% CO2 + 48% N2). 3 separate rat groups were used for IHC analysis. The IHC groups received intrapleural CtB and siRNA injections (outlined above) but did not undergo the neurophysiology protocol (outlined below). The IHC groups were: 1) siTrkB (n=6); 2) siNT (n=6); 3) vehicle (n=6). 50 total rats were used in this study.

Neurophysiology experiments

Anesthetic induction (5% isoflurane in 100% O2) occurred in a closed chamber, followed by maintenance with a nose cone (3.5% isoflurane in 50% O2; 2% CO2; 48% N2). Rats were tracheotomized and pump ventilated for the duration of experiments (2.5 ml, Rodent Ventilator, model 683; Harvard Apparatus; South Natick, MA, USA). Rats were bilaterally vagotomized to eliminate lung stretch-receptor feedback and ventilator entrainment, and the right femoral artery was catheterized for measurement of arterial blood pressure and to allow for sampling of arterial blood for blood gas analysis. The left phrenic nerve was isolated via a dorsal approach, cut distally, de-sheathed, submerged in mineral oil and placed on bipolar silver wire electrodes. After nerve dissection rats were slowly converted to urethane anesthesia (1.8g/kg, i.v. tail vein). Supplemental urethane was provided if rats showed a positive toe pinch response (any purposeful movement or cardiorespiratory response to toe pinch). After ensuring adequate anesthesia, rats were paralyzed with pancuronium bromide (2.5mg/kg, i.v.). Body temperature (measured via rectal probe; Traceable™, Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA, USA) was maintained within ± 0.3°C of baseline (37.5°C) with a custom temperature-controlled surgical table. A flow-through capnograph with sufficient response time to measure end-tidal CO2 in rats (Capnogard, Novametrix; Wallingford, CT; USA) was used to monitor CO2. A heparinized plastic capillary tube (Radiometer Medical Aps, Copenhagen, Denmark; 250×125μl cut in half) was used to monitor temperature corrected arterial blood gases (PaO2 and PaCO2), pH and base excess (ABL 800Flex, Radiometer; Copenhagen, Denmark). Intravenous fluid infusions (1:1.7:5 by volume of NaHCO3/Lactated Ringer’s/Hetastarch; 1.5–2.2ml/hr) were used to maintain blood pressure, acid/base and fluid balance.

Phrenic nerve activity was amplified (x10,000: A-M Systems, Everett, WA), band-pass filtered (100Hz to 10kHz), full-wave rectified, processed as a continuous moving average (CWE 821 filter; Paynter, Ardmore, PA: time constant 50 ms) and analyzed using a WINDAQ data-acquisition system (DATAQ Instruments, Akron, OH). Peak integrated phrenic burst frequency and amplitude were analyzed in 60sec bins prior to blood samples. Data were included only if PaCO2 was maintained within ± 1.5mmHg of baseline levels (set by recruitment threshold for each rat; see below), base excess was within ± 3mEq/L of 0.0, and MAP decreased less than 30mmHg of baseline (approx. 120mmHg) values. Physiological variables are summarized within Table 1. There were no consistent differences between groups within a single time point, or within a single group at different time points. Nerve burst amplitude is expressed as a percent change from baseline; frequency is expressed as an absolute change from baseline (bpm).

Table 1. Physiology variables.

There were no consistent differences of PaCO2, PaO2, standard base excess (SBE), temperature, or mean arterial pressure (MAP) within any individual group or amongst different groups. Differences between groups at a given time point (*) and differences from baseline within individual groups (#) are denoted within the table; p < 0.05. Values expressed as means ± SEM.

| Group | PCO2 (mmHg) | PO2 (mmHg) | SBE | Temp (°F) | MAP (mmHg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | siTrkB+AIH | 44.6 ± 0.932 | 315 ± 8.30 | 1.6 ± 0.54 | 36.5 ± 0.131 | 116 ± 2.92 |

| siNT+AIH | 42.1 ± 0.823 | 348 ± 5.57 | −0.88 ± 0.57 | 36.5 ± 0.156 | 111 ± 7.79 | |

| Vehicle + AIH | 44.6 ± 1.21 | 312 ± 14.2 | 0.47 ± 0.48 | 36.8 ± 0.157 | 122 ± 3.51 | |

| Vehicle + Nx | 43.5 ± 0.617 | 320 ± 6.82 | 0.33 ± 0.48 | 36.8 ± 0.137 | 115 ± 2.78 | |

| Post 15 min | siTrkB+AIH | 44.7 ± 0.911 | 259 ± 14.7 | 0.51 ± 0.44 | 36.7 ± 0.141 | 125 ± 1.49 |

| siNT+AIH | *41.7 ± 0.772 | #293 ± 38.1 | −1.7 ± 0.71 | 36.9 ± 0.333 | 105 ± 9.55 | |

| Vehicle + AIH | 44.2 ± 1.22 | 279 ± 13.3 | −0.96 ± 0.33 | 37.0 ± 0.133 | 122 ± 3.30 | |

| Vehicle + Nx | 43.8 ± 0.593 | 312 ± 9.43 | −0.056 ± 0.43 | 36.8 ± 0.157 | 111 ± 3.46 | |

| Post 30 min | siTrkB+AIH | 44.6 ± 1.06 | 292 ± 10.0 | 0.70 ± 0.49 | 36.4 ± 0.127 | 116 ± 2.33 |

| siNT+AIH | 42.1 ± 0.965 | 335 ± 19.2 | −1.7 ± 0.68 | 37.3 ± 0.344 | 104 ± 6.45 | |

| Vehicle + AIH | 44.9 ± 1.16 | 310 ± 7.18 | −0.85 ± 0.35 | 37.0 ± 0.176 | 120 ± 3.96 | |

| Vehicle + Nx | 43.7 ± 0.739 | 313 ± 10.8 | −0.033 ± 0.45 | 36.5 ± 0.211 | 106 ± 3.95 | |

| Post 60 min | siTrkB+AIH | 44.7 ± 0.942 | *265 ± 40.0 | 0.60 ± 0.54 | 36.5 ± 0.131 | 114 ± 2.67 |

| siNT+AIH | 42.5 ± 0.896 | 335 ± 19.9 | −1.7 ± 0.51 | 37.2 ± 0.107 | 94.8 ± 8.95 | |

| Vehicle + AIH | 44.6 ± 1.15 | 32 ± 6.302 | −1.1 ± 0.34 | 37.0 ± 0.169 | 115 ± 4.51 | |

| Vehicle + Nx | 42.9 ± 0.841 | 315 ± 9.98 | −0.54 ± 0.49 | 36.9 ± 0.137 | 112 ± 3.41 | |

One hour after conversion to urethane anesthesia the CO2 apneic threshold was determined by reducing inspired CO2 and/or increasing ventilator frequency until phrenic nerve activity ceased. Baseline was then established by maintaining end-tidal PACO2 1–2mmHg above the subsequent recruitment threshold – the PACO2 at which phrenic inspiratory activity resumes following apnea (Bach and Mitchell, 1996). Rats were exposed to normoxia gas levels to establish 20min of stable baseline nerve recordings. A blood sample was drawn to establish baseline blood gas values, and the rats were then exposed to either continuous normoxia or AIH (3, 5min episodes of 10% FIO2, 5min intervals). Subsequent arterial blood samples were taken at 15, 30 and 60min post-AIH. Electrophysiological data were analyzed using a 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures design and a Fisher LSD post-hoc analysis (SigmaStat 2.03).

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Following siRNA and CtB injections, 18 rats (n=6 per group; siTrkB, siNT, and vehicle) were euthanized and perfused transcardially with 1mL/g chilled 0.01M PBS followed by 1mL/g chilled 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at a pH of 7.4. The rats were shelf rats that did not receive any surgery related to neurophysiology experiments. The spinal cords were harvested and placed into 4% PFA for 8 hours at 4°C. The tissues were then transferred to 20% sucrose followed by 30% sucrose until sinking. 40μm transverse slices were cut using a microtome (SM2000R Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) from C3–C5 and placed into antifreeze solution (30% glycerol; 30% ethylene glycol; 40% 0.1M PBS). For each group, 8 slices from 6 rats (46 total slices per group) were selected for staining (slices were at least 200μm apart). Slices were washed with 0.05M tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Triton-X (TBS-Tx) and blocked with 1.0% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1hour. The tissues were stained with rabbit anti-TrkB (Santa Cruz Biotech) and goat anti-CtB (Millipore) at room temperature for 16hours. Using western blot and IHC, a previous study has confirmed the selectivity of the TrkB antibody (Krause et al. 2008). Slices were washed with TBS-Tx and subsequently stained with conjugated donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 595 (Invitrogen) and conjugated donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) for 2hours at room temperature. Tissue slices were washed a final time with TBS and mounted with coverslip and an anti-fade solution (Invitrogen). Slices were imaged on an epifluorescence confocal microscope at 20x using Nikon EZ-C1 software. The images were localized onto the phrenic nuclei cluster bilaterally via CtB identification and a reference control region (area immediately lateral to the central canal of C3–C6) for each slice. Since TrkB is often concentrated in dendrites versus the cell soma (Kovalchuk et al., 2002), and CtB retrograde tracer does not reach the peripheral dendrites, we quantified TrkB immunofluorescence (optical density) in a region of interest (diameter: 100 μm; area: 7.85 mm2; circumference: 314 μm) encompassing CtB labeled phrenic motor neurons at C3–C5. The same dimensions were used for the medio-dorsal region of interest as well. While the total number of CtB labeled neurons was consistent among groups, CtB immunofluorescence within individual motor neurons decreased in rats treated with siRNA targeting TrkB mRNA, consistent with other studies showing that functional siRNAs can interrupt transport of retrograde tracers (Murashov et al., 2007). Thus, we did not attempt to normalize TrkB immunofluorescence to CtB staining, but relied on an “area of interest” measurement centered on CtB labeled cells, restricting analysis to the phrenic motor nucleus.

TrkB quantification was done with NIH Image J Software. The siNT rat group was used as a reference (control); thus, changes in TrkB immunofluorescence in other groups were expressed relative to siNT rats. Staining was completed in 2 batches with equal representation of samples from each group in each batch (vehicle, siNT and siTrkB); changes in TrkB immunofluorescence were adjusted relative to the average optical density in siNT rats included in each batch. One way ANOVA was used, with a Fisher’s LSD post hoc test to compare individual groups.

Results

Intrapleural siRNAs targeting TrkB abolish phrenic long-term facilitation

To confirm that TrkB is necessary for pLTF, and to test the hypothesis that the relevant TrkB is within phrenic motor neurons (versus pre-synaptic neurons or nearby glia), we utilized intrapleural injections of small interfering RNAs targeting TrkB mRNA (siTrkB) to selectively knock down TrkB within phrenic motor neurons (Mantilla et al., 2013).

Rats pretreated with siTrkB (n=7), siNT (n=5) or vehicle injections (n=11; Figure 1A), were exposed to AIH and assessed for pLTF expression (Devinney et al., 2013; Fuller et al., 2001; Baker-Herman and Mitchell, 2008). In both siNT and vehicle treated rats, pLTF was robust one-hour post-AIH (Figure 1B–C). In contrast, intrapleural siTrkB injections abolished pLTF (Figure 1B–C). While AIH elicited a small increase in phrenic burst frequency within siNT and vehicle rats, siTrkB rats did not express frequency LTF (Figure 1C). Typically after AIH, changes in respiratory motor output are expressed in burst amplitude with inconsistent and highly variable changes in burst frequency (Figure 1D). Since frequency LTF is small and inconsistent in this preparation (Baker-Herman and Mitchell, 2008), we did not explore it further. An additional group of Nx control rats received intrapleural vehicle injections without AIH (n=9; Figure 1B–D). Nx control rats demonstrated no significant drift in phrenic burst amplitude or frequency, confirming that pLTF results from AIH versus intrapleural injections, surgical procedures or other non-specific effects.

Intrapleural siTrkB selectively down-regulates TrkB protein in phrenic motor neurons

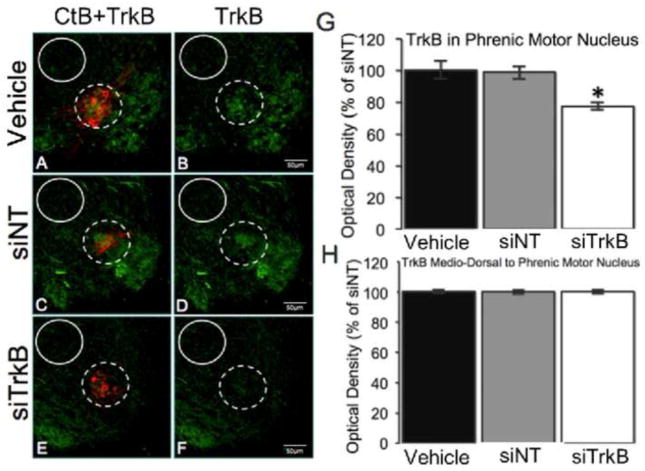

To confirm TrkB protein knockdown within identified phrenic motor neurons shelf rats received intrapleural injections of the CtB retrograde tracer (Mantilla et al., 2009) and either siTrkB, siNT, or vehicle. While TrkB immunofluorescence was abundant near CtB labeled phrenic motor neurons (Figure 2A–B) of siNT and vehicle treated rats (Figures 2C–D), siTrkB rats had relatively reduced TrkB expression (23% reduction relative to siNT and vehicle control groups; Figures 2E–F; 2G). Within the region medio-dorsal to the phrenic motor nucleus, TrkB immunofluorescence was the same between all groups (Figure 2H); this region contains at least some spinal phrenic interneurons (Lane, 2011), suggesting that trans-synaptic transmission of siTrkB did not occur.

Figure 2.

TrkB protein (green) expressed in CtB-labeled phrenic motor neurons (red) of shelf rats injected with vehicle control (A–B; n=6), siNT (C–D; n=6), or siTrkB (E–F; n=6). Phrenic motor nucleus (dashed circle) and medio-dorsal control (solid circle) regions are outlined as noted. siTrkB reduced TrkB immunofluorescence within the phrenic motor nucleus, relative to vehicle control rats (G). Immunofluorescence of TrkB in the phrenic motor nucleus (G) decreased 23% (77%±1.6% of siNT) within rats injected siTrkB, but not rats injected with vehicle. Despite a reduction of TrkB immunofluorescence near the phrenic motor nucleus of rats injected with siTrkB, TrkB immunofluorescence was unchanged in the control region (H). Means (normalized to average siNT TrkB immunofluorescence) ± SEM. * p < 0.001 versus siNT.

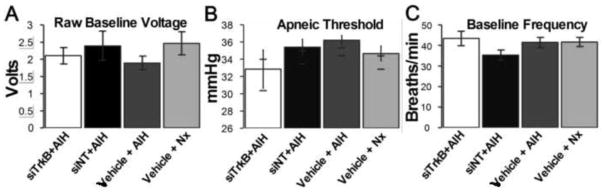

Consistent with a localized knockdown of protein expression within phrenic motor neurons, we show that intrapleural siTrkB: 1) decreases TrkB immunofluorescence within phrenic motor neurons but not nearby regions that contain phrenic interneurons; and 2) abolishes pLTF expression without affecting the short-term hypoxic response, CO2 apneic threshold or baseline nerve activity (Figure 3A–C).

Figure 3.

There were no significant differences among experimental groups (as described in Figure 1) in: A: non-normalized voltage of the integrated phrenic neurogram during baseline conditions; B: CO2 apneic or recruitment thresholds; or C: baseline frequency. Values expressed as means ± SEM. All p>0.05.

Discussion

Although there has been considerable research on cellular mechanisms of synaptic plasticity in the brain, far less attention has been given to spinal motor plasticity in mammals, particularly mechanisms of plasticity in spinal motor neurons. Here we confirm the hypothesis that the relevant TrkB receptors for AIH-induced pLTF are localized within phrenic motor neurons.

BDNF/TrkB signaling and pLTF

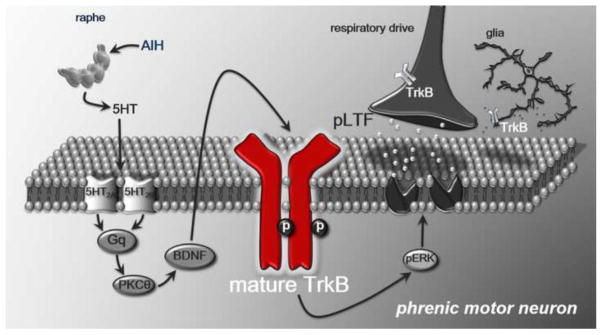

BDNF plays a key role in neurotransmission and activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (Lessmann et al., 1994; Kang and Schuman, 1995; Levine et al., 1995; Berninger and Poo, 1996; Korte et al., 1996; Patterson et al., 1996; Li et al., 1998). Interrupting signaling via the high-affinity BDNF receptor TrkB prevents breathing recovery following cervical spinal hemisection (Mantilla et al., 2013), suggesting an important role of spinal BDNF/TrkB in spontaneous functional recovery following injury. We now show that TrkB activation within phrenic motor neurons is necessary for a well-studied form of respiratory neuroplasticity, BDNF dependent AIH-induced pLTF. We postulate that AIH triggers serotonin release and 5HT2 receptor activation on phrenic motor neurons (Fuller et al. 2001; Baker-Herman and Mitchell, 2002), activating PKC-θ (Devinney et al., 2015) and ERK/MAP kinases (Hoffman et al., 2012), initating new BDNF synthesis (Baker-Herman et al., 2004) and release followed by autocrine TrkB activation (this study). The ultimate outcome of these signaling evnts is a long-term increase in phrenic motor output, possibly by enhancing glutamate receptor funtion (Figure 4; Fuller et al., 2000; McGuire et al., 2008).

Figure 4.

Working model of AIH-induced pLTF. During AIH, serotonin activates 5HT2 receptors on phrenic motor neurons, increasing protein kinase C-θ (PKC-θ) activity and initiating new BDNF synthesis. Here we show that TrkB activation is necessary for pLTF, and that the relevant TrkB (red) is localized within phrenic motor neurons. We propose that subsequent ERK/MAP kinase activation facilitates descending respiratory drive through unknown mechanisms that enhance glutamate-mediated excitation.

Intrapleural siRNAs selectively target phrenic motor neurons

It is difficult to completely rule out trans-synaptic siRNA exchange following intrapleural injections. In cultured cells, some reports suggest that neurons can regulate astrocyte gene expression via exosome mediated micro-RNA transfer (Morel et al., 2013). However, since intrapleural siTrkB down-regulates TrkB protein around CtB labeled phrenic motor neurons (23% reduction relative to siNT and vehicle control groups; Figure 2G), but not in dorsomedial regions (Figure 2H) known to contain synaptically-coupled phrenic interneurons (Lane, 2011), we find no support for the idea that effective trans-synaptic siRNA exchange occurred within this in vivo preparation. Our results are consistent with the report that intrapleural injections of fluorescent siRNAs result in fluorescence within identified phrenic motor neurons and not in adjacent neurons or glia (Mantilla et al., 2013).

Since intrapleural siTrkBs do not affect CO2 apneic threshold, baseline voltage or baseline frequency (Figure 3A–C), siTrkB does not appear to reach the brainstem with sufficient concentration to affect relevant BDNF/TrkB signaling in brainstem regions mediating chemoreflexes or respiratory rhythm generation (Thoby-Brisson et al., 2003). In a previous study from our laboratory, we used intrapleural siRNAs targeting PKC-Θ (Devinney et al., 2015). In this study, ventral spinal PKC-Θ was knocked down >50% and AIH-induced pLTF was abolished, yet this treatment had no effect on XII LTF (Devinney et al., 2015). These results provide additional evidence supporting the idea that intrapleural siRNA effects are localized to spinal motor neurons (or at least motor nuclei). Although other respiratory motor pools associated with the plural space (e.g. intercostal) may be affected by intrapleural siTrkB injections (Mantilla et al., 2009), there is no evidence that direct connections from intercostal to phrenic motor neurons exist and these motor neurons are unlikely to affect pLTF assessed directly in the phrenic nerve. Collectively, data presented here and relevant literature support the hypothesis that intrapleural siRNA injections target spinal respiratory motor neurons, and not pre-synaptic or peri-synaptic elements of the cellular network. Intrapleural siRNA injections appear to be a powerful and relatively non-invasive experimental tool to manipulate gene expression within spinal respiratory motor neurons per se.

These studies increase our understanding of plasticity in an interesting and essential population of constitutively active motor neurons. In specific, they provide additional support or the idea that BDNF-dependent AIH-induced pLTF requires TrkB activation within phrenic motor neurons per se. Thus, phrenic motor neurons appear to “learn” from experience, and are a major site of plasticity in respiratory motor control. Beyond the immediate implications of this study, the efficacy of intrapleural siRNA injections suggests that this approach (Mantilla et al., 2013; Devinney et al., 2015) has powerful experimental advantages in the investigation of new molecules and their biological roles within phrenic and intercostal motor neurons. From a different perspective, intrapleural siRNAs may have potential as a therapeutic intervention to aid in the treatment of severe clinical disorders that cause respiratory and non-respiratory somatic motor deficits (see Mitchell, 2007; Dale et al., 2014; Devinney et al., 2015).

Highlights.

Acute intermittent hypoxia-induced respiratory motor plasticity requires BDNF signaling

Phrenic motor neurons express the high affinity BDNF receptor TrkB

Intrapleural siRNA targeting TrkB receptors decreased TrkB receptor expression selectively on phrenic motor neurons

Intrapleural siRNA targeting TrkB receptors abolished BDNF dependent, hypoxia-induced respiratory motor plasticity

Phrenic motor neurons are a critical site for spinal respiratory motor plasticity

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants HL080209 and HL69064. MJD was supported by institutional training grants (T32): GM86926, GM007507 and HL007654.

Abbreviations

- 5HT

serotonin

- AIH

acute intermittent hypoxia

- BDNF

Brain derived neurotrophic factor

- CtB

Choleratoxin B fragment

- ERK

extracellular regulated kinase

- LTP

long term potentiation

- Nx

normoxia (p)

- LTF

(phrenic) long-term facilitation

- siNT

non-targeting siRNA

- siTrkB

siRNA targeting TrkB

- TrkB

Tropomyosin related kinase B

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bach KB, Mitchell GS. Hypoxia-induced long-term facilitation of respiratory activity is serotonin dependent. Respir Physiol. 1996;104:251–260. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(96)00017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CH, Bartsch D, Kandel ER. Toward a molecular definition of long-term memory storage. PNAS. 1996;93:13445–13452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TL, Mitchell GS. Episodic but not continuous hypoxia elicits long-term facilitation of phrenic motor output in rats. J Physiol. 2000;529:215–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman TL, Mitchell GS. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires spinal serotonin receptor activation and protein synthesis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6239–6246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-06239.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman TL, Fuller DD, Bavis RW, Zabka AG, Golder FJ, Doperalski NJ, Johnson RA, Watters JJ, Mitchell GS. BDNF is necessary and sufficient for spinal respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:48–55. doi: 10.1038/nn1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman TL, Mitchell GS. Determinants of frequency long-term facilitation following acute intermittent hypoxia in vagotomized rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;170:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger B, Poo M. Fast actions of neurotrophic factors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:324–330. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Lomo T. Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol. 1973;232:331–356. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale EA, Ben Mabrouk F, Mitchell GS. Unexpected benefits of intermittent hypoxia: enhanced respiratory and nonrespiratory motor function. J Physiol. 2014;29:39–48. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00012.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale-Nagle EA, Hoffman MS, Macfarlane PM, Mitchell GS. Multiple pathways to long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;669:225–230. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5692-7_45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinney MJ, Fields DP, Huxtable AG, Peterson TJ, Dale EA, Mitchell GS. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires PKCθ activity within phrenic motor neurons. J Neurosci. 2015;35:8107–8117. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5086-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devinney MJ, Huxtable AG, Nichols NL, Mitchell GS. Hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation: emergent properties. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2013;1279:143–153. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JC, Sherrington CS. Reflex summation in the ipsilateral spinal flexion reflex. J Physiol. 1930;69:1–28. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1930.sp002630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman JL, Mitchell GS, Nattie EE. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2003;26:239–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Zabka AG, Baker TL, Mitchell GS. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires 5-HT receptor activation during but not following episodic hypoxia. J App Physiol. 2001;90:2001–2006. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanzman DL. Habituation in Aplysia: the Chesire cat of neurobiology. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;92:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gransee HM, Zhan WC, Sieck GC, Mantilla CB. Targeted delivery of TrkB receptor to phrenic motoneurons enhances functional recovery of rhythmic phrenic activity after cervical spinal hemisection. Plos One. 2013;8:e64755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F, Coles SK, Bach KB, Mitchell GS, McCrimmon DR. Time-dependent phrenic nerve responses to carotid afferent activation: intact vs. decerebellate rats. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R811–R819. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.4.R811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb D. The Organization of Behavior. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman MS, Nichols NL, Macfarlane PM, Mitchell GS. Phrenic long-term facilitation after acute intermittent hypoxia requires spinal ERK activation but not TrkB synthesis. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:1184–1193. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00098.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Trk receptors: roles in neuronal signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:609–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER, Tauc L. Heterosynaptic facilitation in neurones of the abdominal ganglion of Aplysia depilans. J Physiol. 1965a;181:1–27. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER, Tauc L. Mechanism of heterosynaptic facilitation in the giant cell of the abdominal ganglion of the Aplysia depilans. J Physiol. 1965b;181:28–47. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Schuman EM. Long-lasting neurotrophin-induced enhancement of synaptic transmission in the adult hippocampus. Science. 1995;267:1658–1662. doi: 10.1126/science.7886457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkead R, Zhan WZ, Prakash YS, Bach KB, Sieck GC, Mitchell GS. Cervical dorsal rhizotomy enhances serotonergic innervation of phrenic motor neurons and serotonin-dependent long-term facilitation of respiratory motor output in rats. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8436–8443. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08436.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte M, Grisebeck O, Gravel C, Carroll P, Staiger V, Thoenen H, Bonhoeffer T. Virus-mediated gene transfer into hippocampal CA1 region restores long-term potentiation in brain derived neurotrophic factor mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12547–12552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalchuk Y, Hanse E, Kafitz W, Konnerth A. Postsynaptic induction of BDNF-mediated long-term potentiation. Science. 2002;295:1729–1734. doi: 10.1126/science.1067766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause S, Schindowski K, Zechel S, von Bohlen und Halbach O. Expression of TrkB and TrkC receptors and their ligands brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neurotrophin-3 in the murine amygdala. J of Neuro Res. 2008;86:411–421. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Prabhakar NR. Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:141–219. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA. Spinal respiratory motoneurons and interneurons. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;179:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YX, Xu Y, Ju D, Lester HA, Davidson N, Schuman EM. Expression of a dominant negative TrkB receptor, T1, reveals a requirement for presynaptic signaling in BDNF-induced synaptic potentiation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10884–10889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessmann V, Gottmann K, Heumann R. BDNF and NT-4/5 enhance glutamatergic synaptic transmission in cultured hippocampal neurones. Neuroreport. 1994;6:21–25. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412300-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine ES, Dreyfus CF, Black IB, Plummer MR. Brain derived neurotrophic factor rapidly enhances synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons via postsynaptic tyrosine kinase receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8074–8077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.8074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane PM, Vinit S, Mitchell GS. Serotonin 2A and 2B receptor-induced phrenic motor facilitation: differential requirement for spinal NADPH oxidase activity. Neuroscience. 2011;178:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC. Retrograde labeling of phrenic motoneurons by intrapleural injection. J Neurosci Methods. 2009;182:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla CB, Gransee HM, Zhan WZ, Sieck GC. Motoneuron BDNF/TrkB signaling enhances functional recovery after cervical spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;247:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire M, Liu C, Cao Y, Ling L. Formation and maintenance of ventilatory long-term facilitation require NMDA but not non-NMDA receptors in awake rats. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:942–950. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01274.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GS, Baker TL, Nanda SA, Fuller DD, Zabka AG, Hodgeman BA, Bavis RW, Mack KJ, Olson EB. Invited review: Intermittent hypoxia and respiratory plasticity. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2466–2475. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GS, Johnson SM. Neuroplasticity in respiratory motor control. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:358–374. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00523.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GS. Respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia: a guide for novel therapeutic approaches to ventilatory control disorders. In: Gaultier C, editor. Genetic Basis for Respiratory Control Disorders. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. pp. 291–311. [Google Scholar]

- Morel L, Regan M, Higashimori H, Ng SK, Esau C, Vidensky S, Rothstein J, Yang Y. Neuronal exosomal miRNA-dependent translational regulation of astroglial glutamate transporter GLT1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7105–7116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.410944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashov AK, Chintalgattu V, Islamov RR, Lever TE, Pak ES, Sierpinksi PL, Katwa LC, Van Scott MR. RNAi pathway is functional in peripheral nerve axons. FASEB J. 2007;21:656–670. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6155com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima H, Kubo T, Semi Y, Itakura M, Kuwamura M, Izawa T, Azuma YT, Takeuchi T. A rapid, targeted, neuron-selective, in vivo knockdown following a single intracerebroventricular injection of a novel chemically modified siRNA in the adult rat brain. J Biotechnol. 2012;157:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson SL, Abel T, Deuel TA, Martin KC, Rose JC, Kandel ER. Recombinant BDNF rescues deficits in basal synaptic transmission and hippocampal LTP in BDNF knockout mice. Neuron. 1996;16:1137–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramón y Cajal S. Regeneración de los Nervios. 1907. [Translation and edited by J. Bresler (1908) Studien über Nervenregeneration, Johann Ambrosius Barth] [Google Scholar]

- Ruegg UT, Burgess GM. Staurosporine, K-252 and UCN-01: potent but nonspecific inhibitors of protein kinases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1989;10:218–220. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoby-Brisson M, Cauli B, Champagnat J, Fortin G, Katz DM. Expression of functional tyrosine kinase B receptors by rhythmically active respiratory neurons in the pre-Bötzinger complex of neonatal mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7685–7689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07685.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]