Abstract

A culture-based survey of staining fungi on oil-treated timber after outdoor exposure in Australia and the Netherlands uncovered new taxa in Pezizomycotina. Their taxonomic novelty was confirmed by phylogenetic analyses of multi-locus sequences (ITS, nrSSU, nrLSU, mitSSU, RPB1, RPB2, and EF-1α) using multiple reference data sets. These previously unknown taxa are recognised as part of a new order (Superstratomycetales) potentially closely related to Trypetheliales (Dothideomycetes), and as a new species of Cyanodermella, C. oleoligni in Stictidaceae (Ostropales) part of the mostly lichenised class Lecanoromycetes. Within Superstratomycetales a single genus named Superstratomyces with three putative species: S. flavomucosus, S. atroviridis, and S. albomucosus are formally described. Monophyly of each circumscribed Superstratomyces species was highly supported and the intraspecific genetic variation was substantially lower than interspecific differences detected among species based on the ITS, nrLSU, and EF-1α loci. Ribosomal loci for all members of Superstratomyces were noticeably different from all fungal sequences available in GenBank. All strains from this genus grow slowly in culture, have darkly pigmented mycelia and produce pycnidia. The strains of C. oleoligni form green colonies with slimy masses and develop green pycnidia on oatmeal agar. These new taxa could not be classified reliably at the class and lower taxonomic ranks by sequencing from the substrate directly or based solely on culture-dependent morphological investigations. Coupling phenotypic observations with multi-locus sequencing of fungi isolated in culture enabled these taxonomic discoveries. Outdoor situated timber provides a great potential for culturable undescribed fungal taxa, including higher rank lineages as revealed by this study, and therefore, should be further explored.

Key words: Classification of Pezizomycotina, Cyanodermella oleoligni, Dothideomycetes, Fungal cultures, Multi-locus phylogeny, Oil-treated wood, Ostropales, Superstratomycetales

Taxonomic novelties: New order:Superstratomycetales van Nieuwenhuijzen, Miadlikowska, Lutzoni & Samson; New family:Superstratomycetaceae van Nieuwenhuijzen, Miadlikowska, Lutzoni & Samson; New genus:Superstratomyces van Nieuwenhuijzen, Miadlikowska & Samson; New species:Cyanodermella oleoligni van Nieuwenhuijzen & Samson; Superstratomyces albomucosus van Nieuwenhuijzen & Samson; S. atroviridis van Nieuwenhuijzen & Samson; S. flavomucosus van Nieuwenhuijzen & Samson

Introduction

Microbial community composition can be an informative characteristic of an organism, substrate, or habitat. A distinction is made between desirable balanced microbial communities and unbalanced or disturbed communities, for example, in intestines (Roeselers et al., 2011, Gouba et al., 2013) and on skin (Findley et al., 2013, Lloyd-Price et al., 2016), as well as in tap water (Roeselers et al., 2015, Babič et al., 2016) soils (Barot et al., 2007, Creamer et al., 2016) or on wood (Sailer et al., 2010, Purahong et al., 2016). In order to broaden the understanding, and improve applications, of beneficial microbial communities, it is essential that all taxa in these communities are identified.

As part of a study on natural fungal-based wood finishes (biofinishes), fungal compositions on outdoor exposed wood samples were studied using a culture-based method. Fungi were sampled from untreated and oil-treated wood that contained dark fungal stains due to outdoor exposure. Several oil-treated wood samples had dense stained surfaces that met the desirable biofinish criteria of surface coverage and pigmentation (van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. 2015). DNA sequencing of the resulting fungal cultures showed that these biofinishes were composed of multiple genera, always containing the common wood staining fungus Aureobasidium (van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. 2016, unpubl. data). However, not all cultures, even if characterised with molecular data, could be identified taxonomically.

Among the predominant cultured fungal colonies obtained from fungal stained wood surfaces, two types of coelomycetes remained unclassified (van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. unpubl. data). One type involved isolates with darkly coloured pycnidia (referred here as the “dark” group) obtained from several oil-treated and untreated wood samples situated at an outdoor test site in the Netherlands. Isolates of the other type had green coloured pycnidia (referred here as the “green” group) and were obtained from a single oil-treated wood sample exposed to outdoor conditions at a selected site in Australia. Neither morphological nor molecular data for these two fungal groups matched currently known described species.

The aim of this study was to further investigate the phylogenetic affiliations and taxonomic identities of 26 pycnidia-producing fungi isolated from oil-treated wood exposed to outdoor conditions. We sequenced four ribosomal and three protein-coding loci of representative fungal strains and inferred their phylogenetic relationships using multiple data sets including kingdom-, subphylum-, class- and order-wide taxonomic contexts. Furthermore, we conducted a detailed morphological investigation of these fungal isolates. As a result, a new monogeneric order Superstratomycetales (Dothideomycetes) containing three newly proposed species, and a new species Cyanodermella oleoligni (Ostropales, Lecanoromycetes) are formally described here.

Materials and methods

Fungal-stained substrates

The substrates from which fungal isolates were obtained for this study consists of thirteen oil-treated wood samples that contained dark fungal stains due to outdoor exposure. The samples were prepared, exposed and handled as described in van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. (2015). Wood samples were impregnated with olive oil (Carbonel, iodine value 82 and 0,34 % free fatty acids), raw linseed oil (Vereenigde Oliefabrieken, iodine value 183 and 0,81 % free fatty acids), or stand linseed oil (Vliegenthart, viscosity P45). Fungi were sampled from the following oil-treated types of wood: pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) sapwood (sw), pine that mainly contained heartwood (hw), spruce (Picea abies) and ilomba (Pycnanthus angolensis). Information about the substrate (wood species and oil type used) and the geographical location of the outdoor exposure sites for each fungal isolate is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Fungal isolates included in this study with their CBS collection numbers, substrate types, geographic origins, and GenBank accession numbers for the sequenced loci.

| CBS no. | DTO no. | Phenotype | Substrate | Locality | GenBank accession numbers |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | nrLSU | EF-1α | nrSSU | mitSSU | RPB1 | RPB2 | |||||

| 353.84 | 305-C3 | “dark” group | Leaf of Hakea multilinearis | Australia, Perth | KX950411 | KX950438 | KX950470 | KX950466 | KX950462 | KX950493 | KX950497 |

| 140270 | 277-D2 | “dark” group | Ilomba treated with olive oil | The Netherlands | KX950412 | KX950439 | KX950471 | KX950467 | KX950463 | KX950494 | KX950498 |

| 140271 | 277-I3 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with raw linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950413 | KX950440 | KX950472 | KX950468 | KX950464 | KX950495 | KX950499 |

| 140272 | 305-E1 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with raw linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950414 | KX950441 | KX950473 | KX950469 | KX950465 | KX950496 | KX950500 |

| 140273 | 277-C8 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with stand linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950415 | KX950442 | KX950474 | – | – | – | – |

| 140274 | 277-C9 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with stand linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950416 | KX950443 | KX950475 | – | – | – | – |

| 140275 | 277-D3 | “dark” group | Ilomba treated with olive oil | The Netherlands | KX950417 | KX950444 | KX950476 | – | – | – | – |

| 140276 | 277-D4 | “dark” group | Ilomba treated with olive oil | The Netherlands | KX950418 | KX950445 | KX950477 | – | – | – | – |

| 140277 | 277-H6 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with raw linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950419 | KX950446 | KX950478 | – | – | – | – |

| 140278 | 277-H7 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with raw linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950420 | KX950447 | KX950479 | – | – | – | – |

| 140279 | 277-H8 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with stand linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950421 | KX950448 | KX950480 | – | – | – | – |

| 140280 | 277-I2 | “dark” group | Spruce treated with olive oil | The Netherlands | KX950422 | KX950449 | KX950481 | – | – | – | – |

| 140281 | 277-I4 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with stand linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950423 | KX950450 | KX950482 | – | – | – | – |

| 140282 | 277-I5 | “dark” group | Ilomba treated with raw linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950424 | KX950451 | KX950483 | – | – | – | – |

| 140283 | 277-I6 | “dark” group | Spruce treated with olive oil | The Netherlands | KX950425 | KX950452 | KX950484 | – | – | – | – |

| 140284 | 277-I7 | “dark” group | Spruce treated with olive oil | The Netherlands | KX950426 | KX950453 | KX950485 | – | – | – | – |

| 140285 | 277-I8 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with stand linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950427 | KX950454 | KX950486 | – | – | – | – |

| 140286 | 277-I9 | “dark” group | Spruce treated with olive oil | The Netherlands | KX950428 | KX950455 | KX950487 | – | – | – | – |

| 140343 | 278-A2 | “dark” group | Ilomba treated with raw linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950429 | KX950456 | KX950488 | – | – | – | – |

| 140287 | 278-A3 | “dark” group | Spruce treated with olive oil | The Netherlands | KX950430 | KX950457 | KX950489 | – | – | – | – |

| 140288 | 305-D9 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with raw linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950431 | KX950458 | KX950490 | – | – | – | – |

| 140289 | 305-E2 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with raw linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950432 | KX950459 | KX950491 | – | – | – | – |

| 140344 | 305-E3 | “dark” group | Pine sw treated with raw linseed oil | The Netherlands | KX950433 | KX950460 | KX950492 | – | – | – | – |

| 140290 | 301-G1 | “green” group | Pine hw treated with raw linseed oil | Australia | KX950434 | KX950461 | – | KX999145 | KX999144 | KX999146 | KX999147 |

| – | 301-G2 | “green” group | Pine hw treated with raw linseed oil | Australia | KX950435 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| – | 301-G3 | “green” group | Pine hw treated with raw linseed oil | Australia | KX950436 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| – | 301-G4 | “green” group | Pine hw treated with raw linseed oil | Australia | KX950437 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Fungal isolation

Wood staining fungi were collected using the swab sampling method as described in van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. (2015). After incubation on agar plates, the total number of colonies and the number of phenotypically predominant colonies were counted (van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. unpubl. data). Twenty-two colonies representing dark pycnidia producing fungi that originated from wood samples in the Netherlands (“dark” group) and four colonies representing green pycnidia producing fungi that originated from Australia (“green” group) were transferred to fresh malt extract agar (MEA) plates. These isolates were deposited in the CBS-KNAW Culture Collection and/or in the working collection of the Applied and Industrial Department (DTO) housed at the CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, The Netherlands (Table 1).

Molecular data acquisition

Isolates were grown on MEA plates, prepared according to Samson et al. (2010), for at least one week prior to DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted from cultures using the Ultraclean Microbial DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The first DNA amplifications and sequencing were done on the following two loci: the two nuclear internal transcribed spacers and 5.8S rRNA gene (ITS) for each of the 26 fungal wood-stain isolates, and the nuclear ribosomal large subunit (nrLSU) for 23 isolates. All ITS and nrLSU sequences of both types of pycnidia producing fungi (“dark” and “green” groups) were subjected to BLAST searches (Wheeler et al. 2007) using the NCBI database to confirm fungal origin of each sequence fragment and to reveal their putative taxonomy. Top hits based on both ‘maximum identity’ and ‘maximum query cover’ were recorded. Subsequently, ITS and nrLSU sequences were screened against the CBS-KNAW database. Based on this screening, strain CBS 353.84 was added to the 22 fungal isolates of the “dark” group, subjected to morphological examination, and DNA was extracted from a fresh culture (Table 1). Subsequently, the translation elongation factor 1 alpha (EF-1α) was obtained for all strains of the “dark” group. The nuclear ribosomal small subunit (nrSSU), the mitochondrial ribosomal small subunit (mitSSU), and two additional protein-coding genes, namely the largest and second largest subunits of RNA polymerase II (RPB1 and RPB2, respectively), were obtained for five strains (Table 1). Each of the selected strains represented either a group of isolates with identical ITS sequences (“green” group) or one of the resulting clades of the ITS single-locus phylogenetic analysis (“dark” group).

Primers and PCR conditions used for the amplification and the resulting amplicon lengths are provided in Table S1. PCR reactions were performed as described in van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. (2015), including 0.50 μL of each (forward/reverse) primer (10 μM) and 0.1 μL Taq polymerase per 25 μL reaction mixture. PCR-products were sequenced with the BigDye Terminator v. 3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) and the same primer sets as used for PCR amplification. Sequence products were analysed on an ABI PRISM 3730XL genetic analyser (Applied Biosystems, USA) and Seqman Pro v. 9.0.4 (DNAstar Inc.) was used to assemble bio-directional traces into sequence contigs.

Reference data sets and multi-locus phylogenetic analyses

To determine the phylogenetic affiliation and taxonomic identities of the two unknown fungal groups based on multi-locus sequences, we assembled seven different data sets. Phylogenies were inferred based on Maximum Likelihood (ML) using RAxML-HPC2 version 7.2.8 (Stamatakis, 2006, Stamatakis et al., 2008) as implemented on the CIPRES portal (Miller et al. 2010). Optimal tree and bootstrap searches were conducted with the rapid hill-climbing algorithm for 1 000 replicates with GTRGAMMA substitution model (Rodríguez et al. 1990). Five data sets were used to infer the phylogenetic placement of the “dark” group and three data sets were used for the “green” group (Table 2). Sequences of the unknown fungi were added to each reference data set and aligned manually with MacClade 4.08 (Maddison & Maddison 2005) using the “Nucleotide with AA color” option for guiding all alignments for protein-coding genes. Ambiguously aligned regions (Lutzoni et al. 2000) of the alignments were re-adjusted manually and excluded from subsequent phylogenetic analyses. Partition subsets for the RAxML searches and rooting of the resulting phylogenies were in accordance to the original studies that generated the reference data matrices (James et al. 2006 – Analysis 1; Carbone et al. unpubl. data – Analysis 2; Nelsen et al. 2014 and Ertz et al. 2015 – Analysis 5; Miadlikowska et al. 2014 – Analysis 6; Resl et al. 2015 – Analysis 7), except for Analyses 3 and 4, which were based on a newly assembled data set by restricting the Pezizomycotina (Carbone et al. unpubl. data) taxon sampling to Arthoniomycetes + Dothideomycetes only. For these two analyses, two members of Geoglossomycetes were used to root the trees. The data set for Analysis 3 was partitioned into seven subsets corresponding to each non-protein coding locus and each coding position, whereas for Analysis 4 the data set was partitioned into nine subsets (5.8S+nrLSU; mitSSU; nrSSU; 1st position RPB1, RPB2; 2nd position RPB1, RPB2; 3rd position RPB1, RPB2; 1st position EF-1α; 2nd position EF-1α; and 3rd position EF-1α). Data partitions were estimated with PartitionFinder (greedy algorithm to explore all the nucleotide substitution models under the BIC selection criterion; Lanfear et al. 2012).

Table 2.

Number of taxa, loci, and characters included in each data set. Sources of reference sequences for each analysis are cited. ML phylogenetic placements of the two unknown groups of pycnidia-producing fungi are reported with bootstrap support (BS).

| Analyses | Data set | Source of data set | No. of taxa | No. of loci | No. of char. | Phylogenetic placement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Dark” group | ||||||

| Analysis 1 (Fig. S1) | Fungi | James et al. (2006) | 219 | 6 | 8 482 | Arthoniomycetes + Dothideomycetes clade (BS = 80 %); Dothideomycetes (BS = 64 %); sister to Trypethelium (BS = 39 %) |

| Analysis 2 (Fig. S2) | Pezizomycotina | Carbone et al. (unpubl. data) | 986 | 6 | 7 269 | Arthoniomycetes + Dothideomycetes clade (BS = 58 %); Dothideomycetes (BS = 36 %); sister to Trypetheliales (BS = 37 %) |

| Analysis 2A | Pezizomycotina | Carbone et al. (unpubl. data) | 983 | 61 | 7 269 | Dothideomycetes (BS = 30 %); Botryosphaeriaceae (BS = 56 %) |

| Analysis 2B | Pezizomycotina | Carbone et al. (unpubl. data) | 986 | 62 | 7 269 | Dothideomycetes (BS = 40 %); related to Kirschsteiniotheliaceae and part of Phaeotrichiaceae (BS = 32 %) |

| Analysis 3 (Fig. 1, Table S3) | Dothideomycetes + Arthoniomycetes | Carbone et al. (unpubl. data) and Schoch & Grube (2015) | 236 | 7 | 7 072 | Dothideomycetes (BS = 68 %); sister to Trypetheliales (BS = 86 %) |

| Analysis 4 (Fig. S3, Table S3) | Dothideomycetes + Arthoniomycetes + additional Trypetheliales | Carbone et al. (unpubl. data) and Nelsen et al., 2009, Nelsen et al., 2011 | 260 | 7 | 7 072 | Dothideomycetes (BS = 75 %); sister to Trypetheliales (BS = 49 %) |

| Analysis 5 (Fig. S4) | Trypetheliales | Nelsen et al. (2014) and Ertz et al. (2015) | 95 | 2 | 1 011 | Outside of Trypetheliales |

| “Green” group: | ||||||

| Analysis 1 (Fig. S1) | Fungi | James et al. (2006) | 219 | 6 | 8 482 | Lecanoromycetes, Ostropomycetidae, Ostropales (BS = 80 %) |

| Analysis 6 (Fig. S5) | Lecanoromycetes | Miadlikowska et al. (2014) | 1 319 | 5 | 7 433 | Ostropales (BS = 21 %); sister to Cyanodermella viridula (BS = 100 %) |

| Analysis 7 (Fig. 3) | Ostropomycetidae | Resl et al. (2015) | 207 | 8 | 6 665 | Ostropales (BS = 76 %); Stictidaceae (BS = 43 %); sister to Cyanodermella viridula (BS = 100 %) |

“dark” group is represented by the ribosomal RNA loci only (ITS, nrLSU, and nrSSU).

“dark” group is represented by the protein-coding loci only (RPB1, RPB2 and EF-1α).

To infer the general phylogenetic placement (at the class level) of the two unknown pycnidia producing groups within the fungal kingdom, and to delineate the phylogenetic context for the next round of phylogenetic analyses, we added multi-locus sequences of five unknown strains to a data set which has been used to infer the phylogeny of the kingdom Fungi (Analysis 1). Based on these results, the subsequent data sets were restricted to Pezizomycotina (Analysis 2), “Dothideomyceta”: Dothideomycetes and Arthoniomycetes (Analyses 3), “Dothideomyceta” with additional Trypetheliales data (Analysis 4) and Trypetheliales (Analysis 5) for the phylogenetic placement of the “dark” group, and to Lecanoromycetes (Analyses 6) and Ostropomycetidae (Analysis 7) for the placement of the “green” group.

Analysis 1: The multi-locus sequences of four strains from the “dark” group (CBS 353.84, CBS 140270, CBS 140271 and CBS 140272) and one strain from the “green” group (CBS 140290) were added to the James et al. (2006) data set containing six gene regions (three nuclear ribosomal loci: nrLSU, nrSSU, and 5.8S, and three protein-coding genes: EF-1α, RPB1 and RPB2). The maximum likelihood analyses were performed on 8 482 characters for 219 taxa (Table 2). Analysis 2: Sequences of the four representatives from the “dark” group were added to the six-locus supermatrix (5.8S, nrLSU, nrSSU, mitSSU, RPB1, RPB2) used to generate the most comprehensive phylogeny for Pezizomycotina (986 taxa) as part of the online T-BAS tool (http://tbas.hpc.ncsu.edu; Carbone et al. unpubl. data). We also completed analyses on the same data set but our fungal strains were represented by the ribosomal (Analysis 2A; 5.8S, nrLSU, and nrSSU) or protein-coding loci (Analysis 2B; RPB1, RPB2, and EF-1α) only. Analysis 3: Based on the placement of the unknown isolates resulting from Analyses 1 and 2 (inside of Dothideomycetes, sister to Trypetheliales), we restricted this data set to Dothideomycetes + Arthoniomycetes using the T-BAS function for downloading alignments of selected clades (http://tbas.hpc.ncsu.edu; Carbone et al. unpubl. data). We supplemented the six-locus supermatrix by sequences of another protein-coding locus, EF-1α available in GenBank (70 sequences; Schoch & Grube 2015) and completed a maximum likelihood analysis on 7 072 unambiguously aligned characters for 236 taxa. Analysis 4: For this set of analyses, we extended the seven-locus data set (5.8S, nrLSU, nrSSU, mitSSU, RPB1, RPB2, EF-1α) used in Analysis 3 by adding more members of Trypetheliales (24 taxa; Nelsen et al., 2009, Nelsen et al., 2011) for a total of 260 taxa (7 072 characters) to better infer the placement of the four fungal strains from the “dark” group within the Dothideomycetes. Analysis 5: To infer, more specifically, the phylogenetic placement of the unknown “dark” group fungi with regard to Trypetheliales, we used the two-locus (nrLSU and mitSSU) data set for the family Trypetheliaceae from Nelsen et al. (2014) supplemented by nrLSU sequences of six representatives from the recently described family Polycoccaceae (Ertz et al. 2015), for a total of 95 taxa and 1 011 characters. Analysis 6: Based on the placement of the single representative from the “green” group resulting from Analysis 1, we used the Lecanoromycetes data set generated by Miadlikowska et al. (2014) and added the same representative for a total of 1 319 taxa (7 433 characters). Analysis 7: Phylogenetic analyses for the “green” group was performed with the most recent data set (ITS, nrLSU, nrSSU, mitSSU, MCM7, RPB1, RPB2, EF-1α) available for Ostropomycetidae (Resl et al. 2015) and the addition of Cyanodermella viridula for a total of 207 taxa and 6 665 included characters (Table 2). Selected multi-locus matrices and the resulted RAxML trees are available in TreeBASE (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S20205).

Single-locus phylogenetic analyses

To delimit species (and to identify clades for which we obtained additional genes for selected representatives; Table 2) within the “dark” group, we followed the phylogenetic species concept relying on the monophyly criterion and the pattern of congruence among single-locus phylogenies. We assembled and completed ML analyses (as described above) on single-locus data sets of 23 strains: for the ITS (702 sites, one indel excluded), nrLSU (759 sites), and EF-1α (960 sites). Strain CBS 353.84 was used to root the trees based on the phylogenetic relationships among strains inferred with Analyses 1–4 (Table 2). Pairwise distances among 23 strains representing the “dark” pycnidia-containing fungal clade were calculated with PAUP 4.0a147 (Swofford 2003).

Morphological data

To characterise phenotypically the newly delimited taxa, the isolates of the “green” and the “dark” group were subjected to morphological observations. Strains were inoculated in a three point positions onto MEA, potato dextrose agar (PDA), oatmeal agar (OA) and synthetic nutrient-poor agar (SNA) plates. In addition, the strains of the “dark” group were inoculated on a sterilised nettle stem embedded in OA. All agar media were prepared as described by Samson et al. (2010). Strains were grown in dual sets and incubated at 25 °C. Isolates representing the “green” group were studied after seven days of incubation and the “dark” group strains were studied after two and five weeks of incubation. Culture images were captured with a Canon 400D digital camera and a Nikon SMZ25 stereomicroscope. Colony diameters, colony colours and other macroscopic features were recorded. Microscopic characteristics of cultures on OA were studied with an Axio Imager A2 light microscope.

Results

Taxonomic identity of fungal isolates based on BLAST

The results of BLAST searches against GenBank data using ITS and nrLSU sequences were highly inconclusive and varied considerably even at the class level. The top matches, depending on the locus, length of the entry sequence and sorting option of the GenBank hits, indicated that the newly sequenced strains represent two taxonomically different groups of fungi: the top hits for the “dark” group were mostly Dothideomycetes or Sordariomycetes (based on 22 isolates), whereas for the “green” group top hits represented Lecanoromycetes or Leotiomycetes (based on four isolates) (Table S2). Overall, the top BLAST matches, regardless of the locus, had relatively low maximum identity scores (≤85 % and 92 % for the “dark” and “green” groups, respectively) and most query coverages were low as well (≤91 % and 94 % for each group), except for the largest fragment of the nrLSU for the “green” isolate (100 %). The sequences of the “dark” fungi could represent Dothideomycetes based on top matches ranked by maximal identity score of ITS (top hit: Valsaria neotropica), nrLSU long fragment (LR0R-LR7 sequence top hits: Vermiconia calcicola and Preussia minima), and nrLSU short fragment (top hit LR0R-LR5: Cystocoleus ebeneus). However, some top BLAST matches with the higher query cover showed affiliation with other fungal classes, Leotiomycetes and Sordariomycetes (Table S2). The “green” isolates matched mostly the class Lecanoromycetes, subclass Ostropomycetidae when using ITS sequences (top hit Stictis radiata) or Umbilicariomycetidae when using nrLSU sequences (top hit Umbilicaria torrefacta). Only the top hit of the ITS based on maximum identity showed an affiliation with another class, Leotiomycetes (Leptodontidium elatius, Table S2).

After screening the ITS and nrLSU sequences from the CBS database, one strain (CBS 353.84) had a high LSU sequence similarity (more than 97 %) to isolates from the “dark” group. This strain was isolated from a leaf of Hakea multilinearis in Australia by W. Gams in 1984, however, it lacked a proper taxonomic name. The strain was included in the subsequent phylogenetic analyses and morphological examinations of the “dark” group (Table 1).

Because all four ITS sequences from the “green” group were identical, a single strain (CBS 140290) was selected to represent this group in all multi-locus phylogenies. The ITS sequences from the “dark” group were more variable. They contained ten different sequences in total. The ML phylogeny based on ITS showed at least four clades (Fig. 2) and strains CBS 353.84, CBS 140272, CBS 140271, and CBS 140270 were selected to represent these clades in the multi-locus phylogenies.

Fig. 2.

Single-locus ML phylogenies based on the ITS (701 characters), nrLSU (759 characters), and EF-1α (960 characters) for 23 dark pycnidia-forming fungal strains (indicated by CBS culture numbers) strongly supporting the monophyletic delimitation of clades recognized as putative species (sp. 2 and sp. 3) within the newly discovered order of Dothideomycetes (Fig. 1). The third putative species (sp. 1) represented by strain CBS 353.84 was used to root each tree based on the multi-locus phylogenies (Figs. 1, S2 and S3). Bootstrap support values ≥70 % are shown above internodes. The branch length units represent the number of substitutions per site.

Phylogenetic placement of the “dark” group of isolates within Dothideomycetes

The four strains representing the “dark” group formed monophyletic clades in all reconstructed multi-locus phylogenies (bootstrap support [BS] of 100 %; Figs 1, S1–S4). Based on the phylogenetic analysis of the James et al. (2006) data set that covered the fungal kingdom (Analysis 1; Fig. S1, Table 2), the “dark” group lineage was found sister to Trypethelium sp., a member of the family Trypetheliaceae in the order Trypetheliales (taxa from the family Polycoccaceae were not included in the multi-locus analyses 1–4 because only the nrLSU sequences were available in GenBank; Ertz et al. 2015). Although, this relationship, as well as the monophyly of the entire class Dothideomycetes where Trypetheliales are currently classified (e.g., Spatafora et al., 2006, Nelsen et al., 2009, Nelsen et al., 2011, Schoch et al., 2009a), received a low bootstrap support (of 39 % and 64 %, respectively), “Dothideomyceta” (a clade encompassing Arthoniomycetes and Dothideomycetes; Schoch et al., 2009b, Nelsen et al., 2009) was highly supported (80 %) in this phylogeny. Overall, the phylogenetic relationships and their stability in this tree are congruent with the phylogeny from James et al. (2006).

Fig. 1.

ML phylogeny based on a seven-locus data set (5.8S, nrSSU, nrLSU, mitSSU, RPB1, RPB2, and EF-1α) for 236 taxa representing “Dothideomyceta” (Analysis 3, Table 2): Arthoniomycetes (21 taxa) and Dothideomycetes (209 taxa) including four strains from the “dark” group, and two representatives of Geoglossomycetes (used to root the tree). Families and higher taxa in Arthoniomycetes were delimited following Ertz et al. (2014) and in Dothideomycetes according to Wijayawardene et al. (2014). Because of incomplete taxon sampling for Pleosporales, many families are underrepresented and not monophyletic and, consequently, are not annotated. Bootstrap support values above 70 % (with the exception for Dothideomycetes and Dothideomycetidae; BS = 68 % and 65 %, respectively) are shown for each internode. Taxon selection and alignments (except for EF-1α locus; Schoch & Grube 2015) were assembled using T-BAS (Carbone et al. unpubl. data). Arrow indicates the placement of “dark” group strains as a separate monophyletic lineage (BS = 100 %; a putative new order) sister to Trypetheliales (BS = 86 %).

For the subsequent phylogenetic analysis, we restricted the reference taxa to Pezizomycotina utilizing the most taxon-, and locus-comprehensive data set available (Analysis 2, 986 taxa; Carbone et al. unpubl. data). Based on this multi-locus analysis, the sister relationship of the “dark” group lineage with Trypetheliaceae (represented by five genera) was also recovered, but similar to the results from Analysis 1, with very low support (BS = 37 %). Both relationships, the monophyly of Dothideomycetes and its close affiliation with Arthoniomycetes, were poorly supported as well (Fig. S2, Table 2).

Because the ribosomal genes from the “dark” group were very different from fungal sequences available in GenBank, we performed additional analyses on the Pezizomycotina data set where isolates from the “dark” group lineage were represented exclusively by the ribosomal (Analysis 2A) versus the protein coding loci (Analysis 2B). Only the latter analysis showed an increased support (BS 40 %) compared to analysis 2, but still remained below 70 %. In all three analyses, the phylogenetic relationships of known taxa and their stability within Pezizomycotina were generally in agreement with published phylogenies (e.g., Schoch et al. 2009b, Carbone et al. unpubl. data).

Because the subphylum-wide context (Pezizomycotina) of this data set resulted in numerous and often large ambiguously aligned regions that had to be excluded from the phylogenetic analyses, we limited the taxon sampling to “Dothideomyceta” in order to increase the phylogenetic resolution and tree robustness for Analyses 3 and 4 (Tables 2 and S3). The phylogeny resulting from Analysis 3 confirmed for the first time the sister relationship of the “dark” fungal lineage to Trypetheliaceae with high confidence (BS = 86 %; Fig. 1, Table 2). Because in Analyses 2 and 3, the order Trypetheliales was represented by a few taxa only (five and four, respectively; Figs S2 and 1), in Analysis 4 we increased the number of individuals to 28 from twelve genera (Fig. S3, Tables 2, S3). Although the sister relationship of the unknown fungal lineage with Trypetheliaceae was recovered, bootstrap support went down from 86 % (Fig. 1) to 49 % (Fig. S3, Table 2). Clades representing Dothideomycetes received bootstrap support above 70 %, and the relationships among orders and families within both classes were in agreement with previous phylogenies (e.g., Schoch et al. 2009b). While the phylogenetic placement of Trypetheliales within Dothideomycetes remains unsettled (e.g., Schoch et al., 2009a, Nelsen et al., 2009, and this study), the order Trypetheliales was often recovered as one of the earliest evolutionary splits in the class Dothideomycetes, but always with low support. To better infer the phylogenetic placement of the “dark” fungal lineage in relation to Trypetheliales (i.e., outside versus nested within the order) we used a two-locus (nrLSU and mitSSU) data set (Nelsen et al. 2014) encompassing 79 members from Trypetheliaceae and six from Polycoccaceae (Analysis 5). The resulting phylogeny demonstrated that the unknown fungal lineage was placed outside of the order (its monophyly as well as the monophyly of each family was highly supported; >70 %), and therefore recognized as sister to Trypetheliales (Fig. S4, Table 2). Delimitations of the putative genera and informal groups, and their relationships in Trypetheliaceae and Polycoccaceae are in agreement with Ertz et al. (2015) and Nelsen et al. (2014), however, bootstrap support for many internodes went down compared to their phylogenies, most likely because we excluded broader ambiguously aligned regions.

Species delimitation within the unknown lineage of Dothideomycetes

All multi-locus phylogenies suggested the presence of multiple species in the “dark” group of fungi, which were phylogenetically placed in Dothideomycetes. Within this unknown lineage of Dothideomycetes, the sister relationship between strains CBS 140271 and CBS 140270, and their close affiliation with strain CBS 140272 was recovered in all (Figs 1, S1–S3) but one phylogeny (Fig. S4 shows the alternative arrangement involving sister relationship of the latter strain with CBS 353.84 based on two ribosomal loci, nrLSU and mitSSU with BS = 75 %). Using the relationships among strains in the multi-locus phylogenies, we chose CBS 353.84 (the only non-wood isolate) to root single-locus (ITS, nrLSU, and EF-1α) phylogenies inferred for 22 strains for which these three markers were sequenced (Fig. 2, Table 1). In all phylogenies the wood isolates were clustered in two highly supported (BS = 100 %) groups. We considered strain CBS 353.84 as putative species 1, while the two main clades were recognised as putative species 2 and 3. The ITS and EF-1α provided more phylogenetic structure than nrLSU within species 3, which was also represented by the greatest number of isolates (19 strains versus three in species 2, and one in species 1) and may include additional putative taxa. The recognition of three potential species, as shown in Fig. 2, is corroborated by the higher genetic distance observed among them in comparison to genetic variation found within each species (Table S4). The EF-1α sequence for CBS 140344 was very different from the remaining individuals in species 3 (differ by 15 nucleotides) and might represent another taxon. However, multiple copies of EF-1α in fungi have incidentally been reported (James et al., 2006, Henk and Fisher, 2012, Ekanayake et al., 2013) since the first evaluation of this gene as a phylogenetic marker in eukaryotes (Roger et al. 1999).

Phylogenetic placement of the “green” group of isolates within Ostropales

Based on the phylogeny spanning the fungal kingdom (James et al. 2006), the selected representative strain of the “green” group was placed within the order Ostropales (BS = 80 %), subclass Ostropomycetidae in the mostly lichenised class Lecanoromycetes (Fig. S1, Table 2). Analysis 6 on the data set restricted to Lecanoromycetes (Miadlikowska et al. 2014) confirmed the affiliation of these fungi with Ostropales, although with low bootstrap support (Fig. S5). More specifically, it showed a sister relationship with Cyanodermella viridula (BS = 100 %; Fig. S5), a member of the family Stictidaceae (Eriksson 1981). The large scale Ostropomycetidae data set for eight loci from the study by Resl et al. (2015) used in Analysis 7, enabled us to confirm the placement of the “green” group within Ostropales (BS = 76 %) (Fig. 3). However, the family Stictidaceae, including the highly supported clade containing Cyanodermella viridula and the unknown fungal lineage, was poorly supported (below 50 %). Ambiguously aligned regions in our reassembled alignments were more broadly delimited, and therefore more characters were excluded, compared to Resl et al. (2015), especially from the ITS1 and ITS2 regions (6 665 sites were included in our phylogenetic study versus 8 978 sites in Resl et al. 2015). Nevertheless, the overall delimitation of taxa and their relationships (with a few exceptions above the order level, but not well supported), as well as branch robustness, remained at a similar level (37 internodes supported above 70 %). We observed a decrease in bootstrap values (below 70 %) for eleven nodes, but also an increase in support for two internodes in Ostropales (Fig. 3) in comparison to the phylogeny from Resl et al. (2015).

Fig. 3.

ML phylogeny (Analysis 7, Table 2) based on an eight-locus data set (ITS, nrLSU, nrSSU, mitSSU, MCM7, RPB1, RPB2, EF-1α) for 207 taxa representing Ostropomycetidae, the outgroup species from Lecanoromycetes and Lichinomycetes, and one representative of Geoglossomycetes (used to root the tree). Sequences of the fungal strain CBS 140290 and Cyanodermella viridula were added to the concatenated matrix of the 205 reference taxa derived from Resl et al. (2015). Branches outside Ostropales represent genera and families (collapsed when monophyletic and represented as grey triangles). Families and higher taxa were delimited following Miadlikowska et al. (2014) and Resl et al. (2015). Boostrap support values above 50 % and its comparison to ML bootstrap support values obtained by Resl et al. (2015) are provided above each internode (see figure legend for symbol explanations).

Taxonomy of the newly discovered taxa

Superstratomycetales van Nieuwenhuijzen, Miadlikowska, Lutzoni & Samson, ord. nov. MycoBank MB819160.

Etymology: From Latin “super” = above/on the top, and “stratum” = layer of material and from Greek “myces” = organisms, referring to fungal stains forming a top layer or covering the surface of a material.

Diagnosis: Phylogenetically placed in the class Dothideomycetes and potentially affiliated with Trypetheliales, but outside all currently recognised orders of fungi (James et al. 2006, Carbone et al. unpubl. data; Schoch & Grube 2015).

Type genus: Superstratomyces van Nieuwenhuijzen, Miadlikowska & Samson

Includes a single family Superstratomycetaceae and a single genus Superstratomyces.

Superstratomycetaceae van Nieuwenhuijzen, Miadlikowska, Lutzoni & Samson, fam. nov. MycoBank MB819161.

Type genus: Superstratomyces van Nieuwenhuijzen, Miadlikowska & Samson

Diagnosis: Same as the order Superstratomycetales (see above).

Superstratomyces van Nieuwenhuijzen, Miadlikowska & Samson, gen. nov. MycoBank MB819162

Diagnosis: Same as the order Superstratomycetales (see above).

Type species: Superstratomyces albomucosus van Nieuwenhuijzen & Samson

Includes three species.

Superstratomyces albomucosus van Nieuwenhuijzen & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB819163. Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Superstratomyces albomucosus. A–H. Colonies 2 wk old 25 °C; A. MEA obverse; B. OA obverse; C. PDA obverse; D. SNA obverse; E. MEA reverse; F. OA reverse; G. PDA reverse; H. SNA reverse; I. Macroscopic structure of colony on OA showing aerial hyphae and white coloured slimy masses; J. Pycnidia, hyphae and released conidia; K. Conidia; L. Macroscopic structure of a partly scratched colony on a nettle stem embedded in OA; M. Pycnidia and released conidia; N–O. Conidiogenous cells. Scale bars: I, L = 1 000 μm; J, K, M–O = 10 μm.

Etymology: From Latin “albus” = white, “mucosus” = slimy; refers to conidia in white slimy masses.

Diagnosis: Slow growing olive to light grey green colonies with thin white edge (MEA and OA), pycnidia forming aggregated masses (MEA and OA) and white coloured slimy masses (OA). Differs phylogenetically (based on the ITS, nrLSU and EF-1α loci) from the remaining two species in the genus.

Type: The Netherlands, Utrecht, outdoor exposed Pycnanthus angolensis impregnated with olive oil, collector E.J. van Nieuwenhuijzen, 09 Sept 2013 (holotype H-22668; culture ex type CBS 140270 = DTO 277-D2).

Colony characteristics: colony diameters, 2 wk, in mm, 25 °C: MEA 2–13; OA 4–13; PDA 4–12; SNA: 1–5, poor growth. MEA colony: obverse olive to grey-green or light grey-green with thin white edge; reverse dark green or dark green with thin white edge; knotted cone-shaped; slimy masses inconspicuous. OA colony: obverse olive to grey-green or light grey-green with thin white edge; reverse dark green; colony edge slightly elevated; white slimy masses containing abundant amounts of conidia. PDA colony: obverse light grey with thin white edge; reverse dark green or dark green with thin white edge or light brown with thin white edge, tufted colony with centre elevated; slimy masses absent.

Micromorphology OA, 25 °C, 2–5 wk: pycnidia forming brown to black aggregated masses, individual fruiting bodies not present; dark pigmented hyphae; conidia smooth walled, oval typically with blunt ends, length 2.8–6.0 μm, width 1.5–3.0 μm; aerial mycelium hyaline. Micromorphology nettle stem OA, 25 °C, 4–5 wk: pycnidia brown/black, spherical to subspherical, diameter 80–300 μm; conidiogenous cells phialidic.

Ecology and distribution: All strains were isolated from wood impregnated with olive or linseed oil that was exposed to the outdoors in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Additional cultures examined: The Netherlands, Utrecht, outdoor situated log of timber impregnated with oil (wood species and oil types specified in Table 1) 09 Sept 2013 (CBS 140273 = DTO 277-C8, CBS 140274 = DTO 277-C9, CBS 140275 = DTO 277-D3, CBS 140276 = DTO 277-D4), 13 Sept 2013 (CBS 140271 = DTO 277-I3, CBS 140277 = DTO 277-H6, CBS 140278 = DTO 277-H7, CBS 140279 = DTO 277-H8, CBS 140280 = DTO 277-I2, CBS 140281 = DTO 277-I4, CBS 140282 = DTO 277-I5, CBS 140283 = DTO 277-I6, CBS 140284 = DTO 277-I7, CBS 140285 = DTO 277-I8, CBS 140286 = DTO 277-I9, CBS 140287 = DTO 278-A3), 1 May 2014 (CBS 140289 = DTO 305-E2 and CBS 140344 = DTO 305-E3), E.J. van Nieuwenhuijzen.

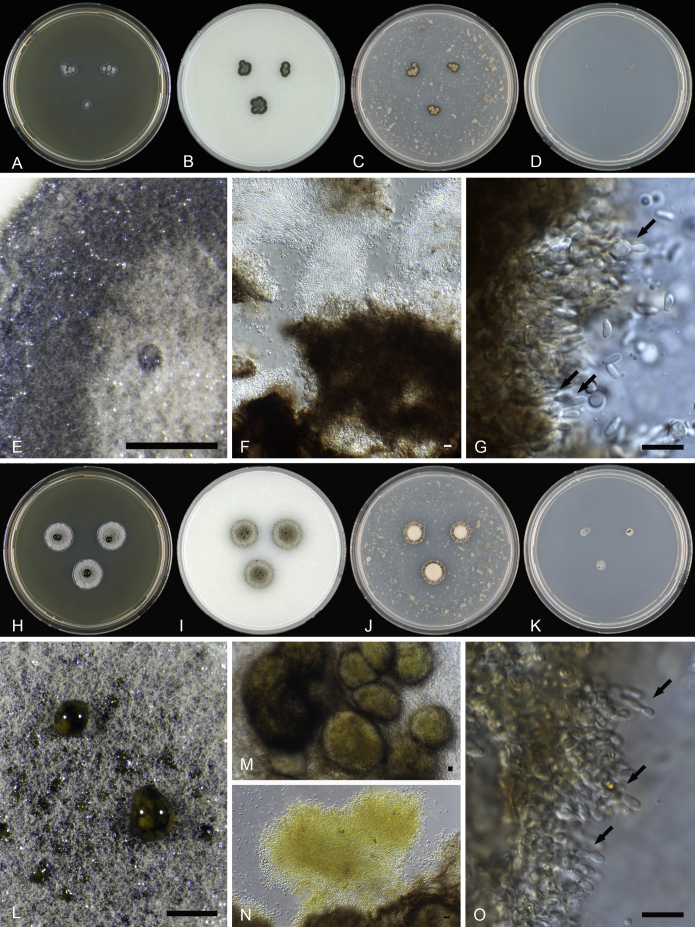

Superstratomyces atroviridis van Nieuwenhuijzen & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB819165. Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Superstratomyces atroviridis. A–D. Colonies 2 wk old 25 °C; A. MEA obverse; B. OA obverse; C. PDA obverse; D. SNA obverse; E. Macroscopic structure of colony on OA showing aerial hyphae and one spot of a white coloured slimy mass; F. Clusters of hyphae and conidia; G. Conidiogenous cells. Superstratomyces flavomucosus. H–K. Colonies 2 wk old 25 °C; H. MEA obverse; I. OA obverse; J. PDA obverse; K. SNA obverse; L. Macroscopic structure of colony on OA showing aerial hyphae and yellow coloured slimy masses; M. Pycnidia; N. Clusters of hyphae and conidia; O. Conidiogenous cells. Scale bars: E, L = 1 000 μm; F, G, M, N, O = 10 μm.

Etymology: From Latin “ater” = dark, black, “viride“ = green; referring to colonies coloured dark green/ black on agar plates.

Diagnosis: Slow growing grey/olive to dark green colonies, with pycnidia forming aggregated masses (MEA and OA) and little or no slimy masses up to five weeks (OA). Differs genetically (based on the ITS, nrLSU and EF-1α loci) from the remaining two species in the genus.

Type: Utrecht, The Netherlands, outdoor exposed Pinus sylvestris impregnated with raw linseed oil, collector E.J. van Nieuwenhuijzen, 01 May 2014 (holotype = H-22669; culture ex type = CBS 140272).

Colony characteristics: colony diameters, 2 wk, in mm, 25 °C: MEA 4–11; OA 7–13; PDA 6–9; SNA: 3–5, poor growth. MEA colony: obverse dark olive to grey green; reverse dark green; tufted colonies with centre elevated; slimy masses inconspicuous. OA colony: obverse dark green; reverse dark green; tufted colonies with centre elevated; incidentally small spots of superficial transparent slimy masses. PDA colony: obverse dark green or grey brown centre and dark green edge; reverse dark green; tufted colonies with centre elevated; slimy masses absent.

Micromorphology OA, 25 °C, 2–5 wk: aggregated mass of dark brown to black pycnidia, individual fruiting bodies not visible; dark pigmented hyphae; conidia smooth walled, oval typically with blunt ends, length (2 wk) 2.6–6.5 μm, width 1.6–2.8 μm; aerial mycelium hyaline. Micromorphology nettle stem OA, 25 °C, 4–5 wk: individual fruiting bodies inconspicuous; conidiogenous cells phialidic.

Ecology and distribution: All three strains were isolated from wood impregnated with linseed oil that was exposed to the outdoors in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Additional cultures examined: The Netherlands, Utrecht, outdoor situated log of Pinus sylvestris sapwood impregnated with raw linseed oil, 01 May 2014 (CBS 140288 = DTO 305-D9) and Pycnanthus angolensis impregnated with raw linseed oil, 13 Sept 2013 (CBS 140343 = DTO 278-A2), E.J. van Nieuwenhuijzen.

Superstratomyces flavomucosus van Nieuwenhuijzen & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB819164. Fig. 5.

Etymology: From Latin “flavus” = yellow, “mucosus” = slimy; refers to conidia in yellow slimy masses.

Diagnosis: Slow growing olive to grey green colonies with pycnidia forming aggregated masses and yellow coloured slimy masses (MEA and OA). Differs genetically (based on the ITS, nrLSU and EF-1α loci) from the remaining two species in the genus.

Type: Australia, Perth, leaf of Hakea multilinearis, collector W. Gams, 01 Aug 1983 (holotype H-22667; culture ex type CBS 353.84).

Colony characteristics: colony diameters, 2 wk, in mm, 25 °C: MEA 8–16; OA 13–16; PDA 10–13; SNA: 4–5, poor growth. MEA colony: obverse olive to grey green; reverse dark green; knotted cone-shaped; yellow slimy masses containing abundant amounts of conidia. OA colony: obverse olive to grey green; reverse dark green; colony edge slightly tufted; yellow slimy masses containing abundant amounts of conidia. PDA colony: light grey with dark green edge; reverse dark green; colony centre clearly tufted; slimy masses absent.

Micromorphology OA, 25 °C, 2 wk: pycnidia forming yellow to dark brown aggregated masses, individual fruiting bodies not visible; dark pigmented hyphae; conidia smooth walled and oval; conidia length 3.4–6.1 μm, width 2.0–3.4 μm; aerial mycelium hyaline. Nettle stem OA, 25 °C, 4–5 wk: pycnidia brown/yellow, spherical to subspherical, diameter 80–170 μm; conidiogenous cells phialidic.

Ecology and distribution: A single strain representing this species was isolated from a leaf of Hakea multilinearis, Perth, Australia.

Cyanodermella oleoligni van Nieuwenhuijzen & Samson, sp. nov. MycoBank MB819166. Fig. 6

Fig. 6.

Cyanodermella oleoligni. A–D. Colonies 1 wk old 25 °C; A. MEA obverse; B. OA obverse; C. PDA obverse; D. SNA obverse; E–H. Colonies 2 wk old 25 °C; E. MEA reverse; F. OA reverse; G. PDA reverse; H. SNA reverse; I. Macroscopic structure of colony on OA; J. Macroscopic structure of pycnidia on OA; K. Pycnidia, hyphae and conidia; L. Pycnidia; M. Macroscopic structure of colony on MEA; N. Cluster of hyphae and conidia; O. Conidia; P. Conidiogenous cells. Scale bars: I, M = 1 000 μm; J = 100 μm; L, N, K, O, P = 10 μm.

Etymology: From Latin “lignum” = wood, which is the main element of the substrate and “oleum” = oil, which is describing the special type of wood. The genitive of the noun is selected to refer to the isolation (of the fungus) from the substrate.

Diagnosis: Medium to slow growing grey green (MEA) and green colonies (OA) with transparent to white coloured slimy masses (MEA) or green spherical pycnidia, which are mostly solitary, but occasionally aggregated (OA). Phylogenetically placed in the order Ostropales (Ostropomycetidae, Lecanoromycetes), sister to Cyanodermella viridula.

Type: Australia, Adelaide, Pinus sylvestris impregnated with raw linseed oil, collector E.J. van Nieuwenhuijzen, 05 Feb 2014 (holotype H-22666; ex type = CBS 140290).

Colony characteristics: colony diameters, 1 wk, in mm, 25 °C: MEA 7–10; OA 6–10; PDA 6–10; SNA: 3–4, poor growth. MEA colony: obverse wrinkled and greenish white with white edge; reverse dark green with white edge; transparent to white coloured slimy masses. OA colony: obverse pattern of green to dark green pycnidia and a white edge without green pycnidia; reverse dark green with white edge; transparent slimy masses. PDA colony: obverse wrinkled and white to olive green with white edge; reverse white to olive green with white edge; slimy masses absent.

Micromorphology OA, 25 °C, 1 wk: pycnidia green, spherical, diameter 25–150 μm, typically solitary, occasionally aggregated. Separated or single layered hyphae and conidia hyaline, dense or double layered biomass dark green. Conidiogenous cells phialidic. Conidia smooth walled, oval typically with blunt ends, length 4.9–8.1 μm, width 1.9–3.0 μm. Aerial mycelium and teleomorphic structures absent.

Ecology and distribution: Four strains were isolated from the surface of a piece of wood (Pinus sylvestris) treated with raw linseed oil, located outdoors in Dover gardens, Adelaide, Australia.

Additional cultures examined: Australia, Adelaide, outdoor situated log of Pinus sylvestris impregnated with raw linseed oil (DTO 301-G2, DTO 301-G3, DTO 301-G4; deposited in culture collection of the Applied and Industrial Department [DTO] housed at the CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre), 05 Feb 2014, E.J. van Nieuwenhuijzen.

Discussion

All reconstructed phylogenies (Figs 1, S1–S4) were in agreement (although mostly with low support, except for analyses 3 and 4; see Tables 2, S3 and Fig. 1) for the placement of the fungal “dark” group as sister to Trypetheliales in Dothideomycetes. Although the order Trypetheliales, recently extended with two lichenicolous genera (Clypeococcum and Polycoccum; Ertz et al. 2015), also includes non-lichenised taxa, the fungal “dark” group is morphologically and phylogenetically distinct. We propose to recognise this new lineage at the order level – Superstratomycetales, with a single family Superstratomycetaceae and a single genus Superstratomyces containing three species (S. albomucosus, S. flavomucosus, and S. atroviridis), each representing a distinct monophyletic lineage based on multiple multi- and single-locus phylogenies (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, S2–S4). All three species are well defined by the barcoding gap approach based on three loci, including ITS (the official DNA barcode marker for fungi; Schoch et al. 2012). Morphological characteristics, mainly of the slimy masses produced on agar plates, support the classification of these three species within the genus Superstratomyces.

Molecular data are necessary for the reliable identification of species in the genus Superstratomyces and for distinguishing them from other pycnidia-producing coelomycetous fungi. To our knowledge, members of the newly described genus Superstratomyces lack unique characteristics and, therefore, cannot be identified based solely on their phenotypes. For example, the observed shapes of the conidiophores and conidia were also observed in pycnidia of species belonging to other genera. DNA sequencing facilitated numerous systematic revisions, and resulted in the addition of new genera to the long-standing coelomycetes such as Septoria, Mycosphaerella, Phoma, Coniothyrium and Phomopsis (Diaporthe) (Crous et al., 2001, de Gruyter et al., 2013, Gomes et al., 2013, Verkley et al., 2013, Verkley et al., 2014). Therefore, a comprehensive study was needed to place them with high confidence in the context of a phylogenetically-based classification. The ITS and nrLSU loci, which are the markers commonly used in molecular systematic studies of fungi, were particularly different for Superstratomyces compared to all available sequences in GenBank, when we conducted this study.

The 23 examined strains of the fungal “dark” group have enlightened the existence of a new order with at least three species. Nevertheless, it is likely that one can find other Superstratomyces taxa if a larger set of isolates is examined, especially when strains are included from other substrates or locations. For example, Superstratomyces was also abundant among the culturable fungi of untreated wood samples in Utrecht, The Netherlands (van Nieuwenhuijzen et al. unpubl. data), and might be present on other substrates at the same test site.

Based on the close phylogenetic relationship of the “green” group to Cyanodermella viridula (Figs 3 and S5), a species classified in Stictidaceae (Ostropales, Lecanoromycetes) (Lumbsch & Huhndorf 2010) we propose to recognise the green pycnidia-producing fungal strains as a new species within the genus Cyanodermella and provided a formal description for C. oleoligni. Our phylogenies (Figs 3 and S5) show a strong support for the placement of the genus Cyanodermella in Ostropales, however, its affiliation with the family Stictidaceae received a low bootstrap support (Table 2). Most phylogenetic studies on Stictidaceae did not include Cyanodermella (Wedin et al., 2005, Fernández-Brime et al., 2011, Baloch et al., 2013), however, the two phylogenies, which contain this taxon, showed similar results to ours (Winka, 2000, Baloch et al., 2010). The placement of Cyanodermella within Ostropales seems to be well established, but its affiliation at the family level remains to be confirmed with higher confidence. Currently, the genus Cyanodermella contains two species: C. viridula and C. candida. Both species were initially classified based on their teleomorph structure by Berkeley & Curtis in 1919 and Setchell in 1924 (Eriksson 1967), and were later renamed by Eriksson (Eriksson, 1967, Eriksson, 1981). Molecular data and herbarium samples (including old leaves of Leymus arenarius) are available for C. viridula only. Although descriptions of cultured isolates of C. viridula and C. candida are missing, their general characteristics include the presence of ascomata with a characteristic blue-green colour. Because the pycnidia of C. oleoligni clearly showed a blue-green colour, the classification of this species within Cyanodermella based on its phylogenetic relationship, is corroborated by this phenotypic trait. The order Ostropales includes mostly crustose taxa with high species richness in the tropics. This order is well known, especially Stictidaceae species, for their non-lichenised members in addition to mostly lichen-forming taxa (Lutzoni et al., 2001, Wedin et al., 2006, Cannon and Kirk, 2007, Schoch et al., 2009b, Baloch et al., 2010, Baloch et al., 2013, Spribille et al., 2014). The inclusion of another, most likely, saprotrophic wood-inhabiting species of Cyanodermella (C. oleoligni) in the order Ostropales fits well within the broad biological spectrum of life strategies of this order (and Ostropomycetidae) where multiple shifts from symbiotrophy (lichen-forming fungi) to saprotrophy (wood-inhabiting fungi), i.e., losses of lichenisation, have been reported (Lutzoni et al., 2001, Spribille et al., 2014).

A culture-based approach coupled with multi-locus phylogenetics is confirmed here as a powerful methodology to classify fungi that generate highly inconclusive BLAST searches. This strategy was implemented by Gazis et al. (2012) and Chen et al. (2015) and led to the discovery of a new class of Fungi – Xylonomycetes, and a new order – Phaeomoniellales – within Eurotiomycetes. ITS or nrLSU BLAST results from GenBank can be used to identify the taxonomic placement of fungal strains, but our study showed that for fungi with top hits below 92 % identity and low coverage (Table S2) BLAST results can be misleading. For example, the top hits based on maximum identity scores turned out to be accurate in predicting the class to which the unknown “dark” group belong (Dothideomycetes), while most of the hits based on highest query coverage were contradictory (Table S2). For the “green” group, the accuracy of the class assignment was the other way around, i.e., where the top hits based on the highest query coverage were correct (Lecanoromycetes), whereas the maximum identity score also suggested an affinity with Leotiomycetes (Table S2). The BLAST results obtained for lower taxonomic levels, such as family and genus, were even more scattered across various fungal taxa and inconsistent. In some cases, the contradictory results may be due to misidentifications or co-sequenced fungi submitted to GenBank.

A comprehensive understanding of microbial communities in time and space, relies on large-scale and robust phylogenies. Fungi, are among the most species-rich clades of the tree of life (Gazis et al. 2012). Estimations of their species number range from 1,5 million (Hawksworth 2001) to 5,1 million (O'Brien et al. 2005, Blackwell 2011). Only a small fraction of the fungal biodiversity has been taxonomically described (Blackwell, 2011, Bass and Richards, 2011), whereas the remaining diversity is known only from molecular data or remains to be discovered (e.g., Arnold et al., 2009, U’Ren et al., 2016). The number of newly described higher-level taxa, especially in the class Dothideomycetes, has been increasing substantially. For example, since the recognition of the Dothideomycetes as a supraordinal taxa of Ascomycota (Eriksson & Winka 1997), sixteen new orders have been added to this class and half of them in the last four years (according to the current information from GenBank). The increase of accessible DNA sequences for fungi across the fungal kingdom in the last ten years coupled with the application of multi-locus phylogenetic analyses facilitates the recognition of new families and orders. A recent phylogenetic treatment of the class Dothideomycetes based on a four-gene combined analysis provided support for 75 of 110 currently recognized families and 23 orders, including seven newly described taxa (Wijayawardene et al. 2014).

Exploration of unique habitats, such as sapwood in remote forests (Gazis et al., 2012, Gazis et al., 2014), cacti in tropical dry forest (Bezerra et al., 2013, Bezerra, 2016), marine borderline lichens (Pérez-Ortega et al. 2016), deep sea water (Jebaraj et al. 2010), and of the Antarctic (Stchigel et al. 2001), revealed new deep lineages in the fungal tree of life. This study, as part of a research project on fungal-based wood finishes, showed that mundane substrates modified by humans, are also a valuable potential source of hidden fungal taxonomic novelties.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Manon Timmermans (Life Without Barriers) for the outdoor exposure of wood samples, Martin Meijer (CBS-KNAW) for his technical assistance, Ove Eriksson (Umeå University) for providing information on Cyanodermella species and Konstanze Bensch (CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre) who kindly helped with the Latin naming. We thank C. Schoch, M. Nelsen, and P. Resl for providing unpublished versions of the alignments that we used as reference data sets for this study.

This research was supported by the Dutch Technology Foundation STW within the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) (Project number STW 11345/210-C81010 NWO) partly funded by the Ministry of Economic Affairs. Partners of this STW research project are CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Eindhoven University of Technology, TNO, Lambert van den Bosch, Stiho, Touchwood and Regge Hout. This project was also funded in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Grant DEB-0640956 and the Dimensions of Biodiversity (DoB) award DEB-1046065 to FL, as well as a GoLife award DEB-1541548 to FL and JM.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.simyco.2016.11.008.

Contributor Information

J.M. Miadlikowska, Email: jolantam@duke.edu.

J.A.M.P. Houbraken, Email: j.houbraken@cbs.knaw.nl.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

ML majority rule bootstrap tree (Analysis 1; Table 2) based on the six-locus data set (5.8S, nrLSU, nrSSU, RPB1, RPB2, EF-1α) for 219 taxa of which 204 represent the kingdom Fungi, including four strains from the “dark” group and one from the “green” group (indicated by arrows). Members of Viridiplantae were used to root the tree. Sequences of the unknown fungal strains were added to the concatenated matrix of the reference 214 taxa derived from the study by James et al. (2006). Taxonomic groups were delimited following James et al. (2006). Bootstrap support values for all topological bipartitions are shown above the internodes.

ML majority rule bootstrap tree (Analysis 2, Table 2) based on the six-locus data set (5.8S, nrLSU, nrSSU, mtSSU, RPB1, RPB2) for 986 taxa of which 963 represent Pezizomycotina, including four Dothideomycetes-related strains (indicated by an arrow) and 23 outgroup taxa (Taphrinomycotina and Saccharomycotina). The Taphrinomycotina clade was used to root the tree. Sequences of strains from the “dark” group were added to the concatenated matrix of the reference 959 taxa, part of the online T-BAS tool (http://tbas.hpc.ncsu.edu; Carbone et al. unpubl. data). Taxonomic groups were delimited following Carbone et al. unpubl. data. Bootstrap support values for all topological bipartitions are shown above the internodes.

ML majority rule bootstrap tree (Analysis 4, Table 2) based on the seven-locus data set (5.8S, nrLSU, nrSSU, mtSSU, RPB1, RPB2, EF-1α) for 260 taxa representing “Dothideomyceta”: Arthoniomycetes (21) and Dothideomycetes (237) including four strains from the “dark” group (indicated by an arrow) and two members of Geoglossomycetes used to root the tree. This is the data set used in Analysis 3 (Fig. 1) that was supplemented with additional members of Trypetheliales (24 taxa; Nelsen et al., 2009, Nelsen et al., 2011). Taxonomic groups in Arthoniomycetes were delimited following Ertz et al. (2014) and in Dothideomycetes according to Wijayawardene et al. (2014). Bootstrap support values for all topological bipartitions are shown above the internodes.

ML majority rule bootstrap tree (Analysis 5, Table 2) based on a two-locus data set (nrLSU and mitSSU) for 85 taxa representing Trypetheliales (79 taxa from Trypetheliaceae and six from Polycoccaceae), four strains from the “dark” group (indicated by an arrow) and six outgroup taxa used to root the tree. Sequences of Polycoccaceae (Ertz et al. 2015) and the strains from the “dark” group were added to the matrix from Nelsen et al. (2014). Taxa were delimited following Nelsen et al. (2014). Bootstrap support values for all topological bipartitions are shown above the internodes.

ML majority rule bootstrap tree (Analysis 6, Table 2) based on a five-locus data set (nrLSU, nrSSU, mtSSU, RPB1, RPB2,) for 1 319 taxa representing mostly Lecanoromycetes (cumulative supermatrix from Miadlikowska et al. 2014, but sequences representing potential contaminants were removed as suggested in that study) including the strain from the “green” group (indicated by an arrow). Taxonomic groups were delimited following Miadlikowska et al. (2014). Bootstrap support values for all topological bipartitions are shown above the internodes.

References

- Arnold A.E., Miadlikowska J., Higgins K.L. A phylogenetic estimation of trophic transition networks for ascomycetous fungi: are lichens cradles of symbiotrophic fungal diversification? Systematic Biology. 2009;58:283–297. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syp001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babič M.N., Zalar P., Ženko B. Yeasts and yeast-like fungi in tap water and groundwater, and their transmission to household appliances. Fungal Ecology. 2016;20:30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Baloch E., Gilenstam G., Wedin M. The relationships of Odontotrema (Odontotremataceae) and the resurrected Sphaeropezia (Stictidaceae)—new combinations and three new Sphaeropezia species. Mycologia. 2013;105:384–397. doi: 10.3852/12-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloch E., Lücking R., Lumbsch H.T. Major clades and phylogenetic relationships between lichenized and non-lichenized lineages in Ostropales (Ascomycota: Lecanoromycetes) Taxon. 2010;59:1483–1494. [Google Scholar]

- Barot S., Blouin M., Fontaine S. A tale of four stories: soil ecology, theory, evolution and the publication system. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass D., Richards T.A. Three reasons to re-evaluate fungal diversity ‘on Earth and in the ocean’. Fungal Biology Reviews. 2011;25:159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra J.D.P., Oliveira R.J.V., Paiva L.M. Bezerromycetales and Wiesneriomycetales ord. nov. (class Dothideomycetes), with two novel genera to accommodate endophytic fungi from Brazilian cactus. Mycological Progress. 2016 accepted Nov 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra J.D., Santos M.G., Barbosa R.N. Fungal endophytes from cactus Cereus jamacaru in Brazilian tropical dry forest: a first study. Symbiosis. 2013;60:53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell M. The fungi: 1, 2, 3…5.1 million species? American Journal of Botany. 2011;98:426–438. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon P.F., Kirk P.M. CABI; UK: 2007. Fungal families of the world. [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.H., Miadlikowska J., Molnár K. Phylogenetic analyses of eurotiomycetous endophytes reveal their close affinities to Chaetothyriales, Eurotiales and a new order – Phaeomoniellales. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2015;85:117–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creamer R.E., Hannula S.E., van Leeuwen J.P. Ecological network analysis reveals the inter-connection between soil biodiversity and ecosystem function as affected by land use across Europe. Applied Soil Ecology. 2016;97:112–124. [Google Scholar]

- Crous P.W., Kang J.C., Braun U. A phylogenetic redefinition of anamorph genera in Mycosphaerella based on ITS rDNA sequence and morphology. Mycologia. 2001;93:1081–1101. [Google Scholar]

- de Gruyter J., Woudenberg J.H.C., Aveskamp M.M. Redisposition of Phoma-like anamorphs in Pleosporales. Studies in Mycology. 2013;75:1–36. doi: 10.3114/sim0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekanayake P.N., Rabinovich M., Guthridge K.M. Phylogenomics of fescue grass-derived fungal endophytes based on selected nuclear genes and the mitochondrial gene complement. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson O.E. On graminicolous pyrenomycetes from Fennoscandia. Arkiv För Botanik Series. 1967;2:381–440. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson O.E. The families of bitunicate Ascomycetes. Opera Botanica. 1981;60:1–209. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson O.E., Winka K. Supraordinal taxa of Ascomycota. Myconet. 1997;1:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ertz D., Diederich P., Lawrey J.D. Phylogenetic insights resolve Dacampiaceae (Pleosporales) as polypheletic: Didymocyrtis (Pleosporales, Phaeosphaeriaceae) with Phoma-like anamorphs resurrected and segregated from Polycoccum (Trypetheliales, Polycoccaceae fam. nov.) Fungal Diversity. 2015;74:53–89. [Google Scholar]

- Ertz D., Lawrey J.D., Common R.S. Molecular data resolve a new order of Arthoniomycetes sister to the primarily lichenized Arthoniales and composed of black yeasts, lichenicolous and rock-inhabiting species. Fungal Diversity. 2014;66:113–137. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Brime S., Llimona X., Molnar Expansion of the Stictidaceae by the addition of the saxicolous lichen-forming genus Ingvariella. Mycologia. 2011;103:755–763. doi: 10.3852/10-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley K., Oh J., Yang J. Topographic diversity of fungal and bacterial communities in human skin. Nature. 2013;498:367–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazis R., Miadlikowska J., Lutzoni F. Culture-based study of endophytes associated with rubber trees in Peru reveals a new class of Pezizomycotina: Xylonomycetes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2012;65:294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazis R., Skaltsas D., Chaverri P. Novel endophytic lineages of Tolypocladium provide new insights into the ecology and evolution of Cordyceps-like fungi. Mycologia. 2014;106:1090–1105. doi: 10.3852/13-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes R.R., Glienke C., Videira S.I.R. Diaporthe: a genus of endophytic, saprobic and plant pathogenic fungi. Persoonia-Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2013;31:1–41. doi: 10.3767/003158513X666844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouba N., Raoult D., Drancourt M. Plant and fungal diversity in gut microbiota as revealed by molecular and culture investigations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth D.L. The magnitude of fungal diversity: the 1.5 million species estimate revisited. Mycological Research. 2001;105:1422–1432. [Google Scholar]

- Henk D.A., Fisher M.C. The gut fungus Basidiobolus ranarum has a large genome and different copy numbers of putatively functionally redundant elongation factor genes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James T.Y., Kauff F., Schoch C. Reconstructing the early evolution of Fungi using a six-gene phylogeny. Nature. 2006;443:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature05110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jebaraj C.S., Raghukumar C., Behnke A. Fungal diversity in oxygen-depleted regions of the Arabian Sea revealed by targeted environmental sequencing combined with cultivation. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2010;71:399–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfear R., Calcott B., Ho S.Y. Partitionfinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2012;29:1695–1701. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Price J., Abu-Ali G., Huttenhower C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Medicine. 2016;8 doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0307-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumbsch T., Huhndorf S. Myconet Vol 14. Fieldiana: Life and Earth Sciences. 2010;1:1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lutzoni F., Pagel M., Reeb V. Major fungal lineages are derived from lichen symbiotic ancestors. Nature. 2001;411:937–940. doi: 10.1038/35082053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzoni F., Wagner P., Reeb V. Integrating ambiguously aligned regions of DNA sequences in phylogenetic analyses without violating positional homology. Systematic Biology. 2000;49:628–651. doi: 10.1080/106351500750049743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison D., Maddison W. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, Massachusetts: 2005. MacClade v. 4.08. [Google Scholar]

- Miadlikowska J., Kauff F., Högnabba F. Multigene phylogenetic synthesis for the class Lecanoromycetes (Ascomycota): 1307 fungi representing 1139 infrageneric taxa, 312 genera and 66 families. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2014;79:132–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M.A., Pfeiffer W., Schwartz T. Proceedings Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), New Orleans, LA. 2010. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen M.P., Lücking R., Aptroot A. Elucidating phylogenetic relationships and genus-level classification within the fungal family Trypetheliaceae (Ascomycota: Dothideomycetes) Taxon. 2014;63:974–992. [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen M.P., Lücking R., Grube M. Unravelling the phylogenetic relationships of lichenised fungi in Dothideomyceta. Studies in Mycology. 2009;64:135–144. doi: 10.3114/sim.2009.64.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen M.P., Lücking R., Mbatchou J.S. New insights into relationships of lichen-forming Dothideomycetes. Fungal Diversity. 2011;51:155–162. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien H.E., Parrent J.L., Jackson J.A. Fungal community analysis by large-scale sequencing of environmental samples. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71:5544–5550. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5544-5550.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Ortega S., Garrido-Benavent I., Grube M. Hidden diversity of marine borderline lichens and a new order of fungi: Collemopsidiales (Dothideomyceta) Fungal Diversity. 2016;80:285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Purahong W., Arnstadt T., Kahl T. Are correlations between deadwood fungal community structure, wood physico-chemical properties and lignin-modifying enzymes stable across different geographical regions? Fungal Ecology. 2016;22:98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Resl Ph, Schneider K., Westberg M. Diagnostics for a troubled backbone: testing topological hypotheses of trapelioid lichenized fungi in a large-scale phylogeny of Ostropomycetidae (Lecanoromycetes) Fungal Diversity. 2015;73:239–258. doi: 10.1007/s13225-015-0332-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez F.J., Oliver J.L., Marín A. The general stochastic model of nucleotide substitution. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1990;142:485–501. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeselers G., Coolen J., Wielen P.W. Microbial biogeography of drinking water: patterns in phylogenetic diversity across space and time. Environmental Microbiology. 2015;17:2505–2514. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeselers G., Mittge E.K., Stephens W.Z. Evidence for a core gut microbiota in the zebrafish. The ISME Journal. 2011;5:1595–1608. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger A.J., Sandblom O., Doolittle W.F. An evaluation of elongation factor 1 alpha as a phylogenetic marker for eukaryotes. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1999;16:218–233. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sailer M.F., van Nieuwenhuijzen E.J., Knol W. Forming of a functional biofilm on wood surfaces. Ecological Engineering. 2010;36:163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Samson R.A., Houbraken J., Thrane U. CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre; The Netherlands: 2010. Food and Indoor fungi. [Google Scholar]

- Schoch C.L., Crous P.W., Groenewald J.Z. A class-wide phylogenetic assessment of Dothideomycetes. Studies in Mycology. 2009;64:1–15. doi: 10.3114/sim.2009.64.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch C.L., Grube M. Pezizomycotina: Dothideomycetes and Arthoniomycetes. In: McLaughlin D.J., Spatafora J.W., editors. vol. VII. Springer Verlag; Germany: 2015. pp. 143–176. (The mycota – systematics and evolution part B). [Google Scholar]

- Schoch C.L., Seifert K.A., Huhndorf S. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:6241–6246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch C.L., Sung G.-H., López-Giráldez F. The Ascomycota tree of life: a phylum wide phylogeny clarifies the origin and evolution of fundamental reproductive and ecological traits. Systematic Biology. 2009;58:224–239. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syp020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spatafora J.W., Johnson D., Sung G.H. A five-gene phylogenetic analysis of the Pezizomycotina. Mycologia. 2006;98:1020–1030. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.98.6.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spribille T., Resl P., Ahti T. Molecular systematics of the wood-inhabiting, lichen-forming genus Xylographa (Baeomycetales, Ostropomycetidae) with eight new species. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis Symbolae botanicae Upsalienses: Arbeten fran Botaniska institutionerna i Uppsala. 2014;37:1–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A., Hoover P., Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Systematic Biology. 2008;57:758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stchigel A.M., Josep C.A.N.O., Mac Cormack W. Antarctomyces psychrotrophicus gen. et sp. nov., a new ascomycete from Antarctica. Mycological Research. 2001;105:377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D.L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (* and other methods). Version 4. 2003. http://paup.csit.fsu.edu/

- U'Ren J., Miadlikowska J., Zimmerman N.B. Contributions of North American endophytes to the phylogeny, ecology, and taxonomy of Xylariaceae (Sordariomycetes, Ascomycota) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2016;98:210–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nieuwenhuijzen E.J., Houbraken J.A.M.P., Meijer M. Aureobasidium melanogenum: a native of dark biofinishes on wood. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2016;109:661–683. doi: 10.1007/s10482-016-0668-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nieuwenhuijzen E.J., Sailer M.F., Gobakken L.R. Detection of outdoor mould staining as biofinish on oil treated wood. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 2015;105:215–227. [Google Scholar]

- Verkley G.J.M., Dukik K., Renfurm R. Novel genera and species of coniothyrium-like fungi in Montagnulaceae (Ascomycota) Persoonia-Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution of Fungi. 2014;32:25–51. doi: 10.3767/003158514X679191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkley G.J.M., Quaedvlieg W., Shin H.D. A new approach to species delimitation in Septoria. Studies in Mycology. 2013;75:213–305. doi: 10.3114/sim0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]