Abstract

Analysis of the A. tumefaciens genome revealed estC, which encodes an esterase located next to its transcriptional regulator estR, a regulator of esterase in the MarR family. Inactivation of estC results in a small increase in the resistance to organic hydroperoxides, whereas a high level of expression of estC from an expression vector leads to a reduction in the resistance to organic hydroperoxides and menadione. The estC gene is transcribed divergently from its regulator, estR. Expression analysis showed that only high concentrations of cumene hydroperoxide (CHP, 1 mM) induced expression of both genes in an EstR-dependent manner. The EstR protein acts as a CHP sensor and a transcriptional repressor of both genes. EstR specifically binds to the operator sites OI and OII overlapping the promoter elements of estC and estR. This binding is responsible for transcription repression of both genes. Exposure to organic hydroperoxide results in oxidation of the sensing cysteine (Cys16) residue of EstR, leading to a release of the oxidized repressor from the operator sites, thereby allowing transcription and high levels of expression of both genes. The estC is the first organic hydroperoxide-inducible esterase-encoding gene in alphaproteobacteria.

Introduction

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a Gram-negative soil bacterium that causes crown gall tumor in a wide variety of dicotyledonous plants worldwide. As a plant pathogen, A. tumefaciens is exposed to reactive oxygen species (ROS), including H2O2, superoxide anions, and lipid hydroperoxides that are generated by of active plant defense responses and from other microbes in the environment [1]. Oxidative stress protection systems in A. tumefaciens have been partially characterized. At least three oxidative stress sensors/transcriptional regulators, SoxR, OxyR, and OhrR that sense increased levels of superoxide anion, H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides, respectively, have been investigated [2–6]. SoxR directly regulates sodBII, which encodes iron containing superoxide dismutase, whereas OxyR controls the expression of the katA catalase gene [4–6]. OhrR regulates the expression of the organic hydroperoxide resistance protein Ohr [2]. OhrR is a transcriptional repressor classified in the MarR family. Under physiological conditions, the OhrR dimer binds the target promoter and represses transcription. When bacteria are exposed to organic hydroperoxides, OhrR is oxidized through the oxidation of a sensing reactive cysteine residue [7, 8]. Consequently, oxidized OhrR changes its structure and is released from the repressor binding site near the ohr promoter, thereby allowing the transcription of ohr. On the basis of cysteine residues involved in the oxidation step, bacterial OhrR proteins can be divided into two groups, 1-Cys and 2-Cys. The majority of the characterized OhrRs, including Xanthomonas campestris OhrR, belong to the 2-Cys group [7, 8]. Oxidation of X. campestris OhrR involves 2 cysteine residues. Upon exposure to organic hydroperoxides, a reactive sensing cysteine residue (Cys22) is oxidized, and reactive sulfenic acid intermediates react with a resolving cysteine residue (Cys127) forming an inter-subunit disulfide bond. Formation of the disulfide bond causes rotation of the winged helix-turn-helix motif leading to the repressor-DNA dissociation. Bacillus subtilis OhrR is a representative of 1-Cys group that contains a reactive cysteine residue corresponding to the Cys22 of the X. campestris OhrR [9]. Oxidation of the B. subtilis OhrR occurs through cysteine oxidation leading to formation of a mix-disulfide bond with a low-molecular-weight thiol molecule, bacillithiol [10, 11]. Experiments in vivo have demonstrated that OhrRs preferentially sense organic hydroperoxides ranging from synthetic alkyl hydroperoxide to fatty acid hydroperoxides. We have reported the characterization of A. tumefaciens OhrR, a member of the 2-Cys group OhrR that regulates a divergently transcribed gene ohr in an organic hydroperoxide-inducible fashion [2]. Currently, the only known OhrR target gene in A. tumefaciens is ohr.

In this communication, we functionally characterized estR, an ohrR paralog, as the transcriptional regulator of estC, a gene encoding a protein with esterase activity that belongs to the α/β hydrolase superfamily. The α/β hydrolases are one of the largest groups of structurally related enzymes containing an α/β hydrolase fold that consists of an eight-stranded, mostly parallel α/β structure and a Nucleophile-His-Acid catalytic triad [12]. The enzymes in this family catalyze diverse reactions and include acid ester hydrolase, haloperoxidase, haloalkane dehalogenase, and C-C bond breaking enzymes. We show here that estC expression is inducible by treatment with organic hydroperoxide.

Results and Discussion

The atu5211 gene encodes an OhrR paralog

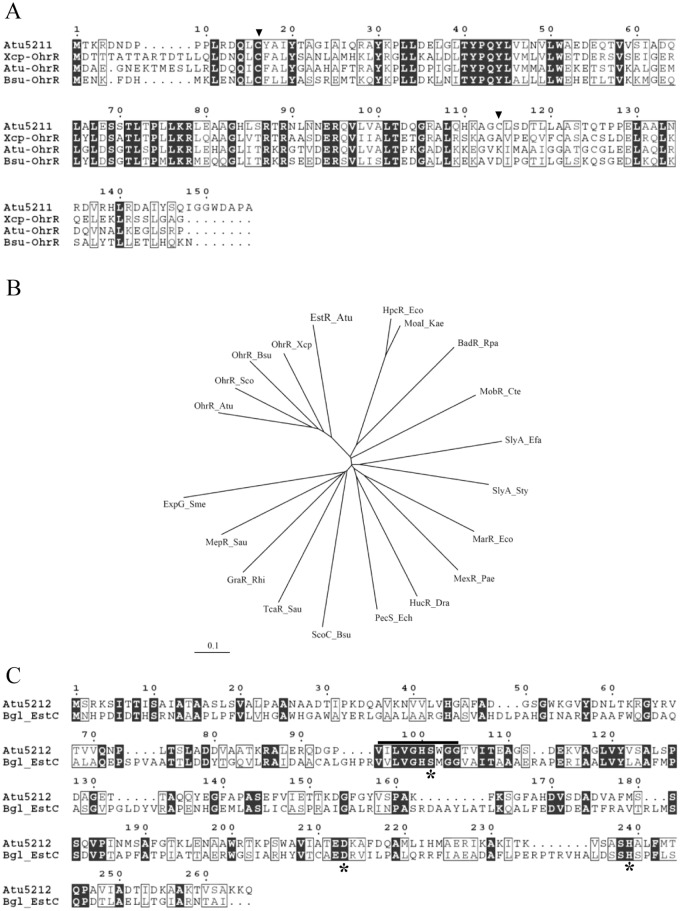

The Xanthomonas campestris OhrR sequence [13] was used to search the A. tumefaciens genome [14]. Five OhrR paralogs could be identified from 20 putative coding sequences (CDS) classified in MarR family. The results are atypical because most bacterial genomes have only one OhrR. We have previously characterized the OhrR (Atu0846) that regulates ohr (Atu0847) [2]. Here, an additional OhrR paralog, Atu5211 was identified. Multiple alignments of the Atu5211 sequence with other OhrRs revealed that key amino acid residues, particularly the peroxide sensing Cys16 residue that corresponds to Cys22 of X. campestris OhrR [13] and the Tyr30 and Tyr41 residues (Tyr36 and Tyr47 in X. campestris OhrR), which are important for sensing oxidized cysteine and forming a hydrogen bond network with Cys22 [8], are conserved (Fig 1A). The presence of an additional cysteine residue (Cys114) near the C-terminus suggests that Atu5211 belongs to the 2-Cys group of OhrRs [2, 13]. Phylogenetic analysis of selected regulators belonging to a MarR family strongly suggests that this Atu5211 is a transcription repressor (Fig 1B). However, Atu5211 is a distant member of other well characterized OhrRs (Fig 1B). This raises the question of whether mechanistically and functionally, Atu5211 is similar to other members of the OhrR group.

Fig 1. Multiple alignments of Atu5211 (EstR) and Atu5212 (EstC).

A, The deduced amino acid sequence of Atu5211 (EstR) was aligned with OhrR from Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli (OhrR_Xcp), A. tumefaciens (OhrR_Atu) and Bacillus subtilis (OhrR_Bsu). Cysteine residues are marked by arrow heads. B, A phylogenetic tree constructed from the amino acid sequences of transcriptional regulators belonging to MarR super family. EstR_Atu, A. tumefaciens EstR; OhrR_Xcp, Xanthomonas campestris pv. phaseoli OhrR (AAK62673); OhrR_Bsu, Bacillus subtilis OhrR (NP_389198); OhrR_Sco, Streptomyces coelicolor OhrR (CAB87337); OhrR_Atu, Agrobacterium tumefaciens OhrR (AAK86653); ExpG_Sme, Sinorhizobium meliloti ExpG (CAB01941); MepR_Sau, Staphylococcus aureus MepR (AAU95767), GraR_Rhi, Rhizobium sp GraR (BAF44528); TcaR_Sau, Staphylococcus aureus TcaR (AAG23887); ScoC_Bsu, Bacillus subtilis ScoC (NP_388880); PecS_Ech, Erwinia chrysanthemi PecS (CAA52427); HucR_Dra, Deinococcus radiodurans HucR (NP_294883); MexR_Pae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa MexR (AAO40258); MarR_Eco, Escherichia coli MarR (ABE11597); SlyA_Sty, Salmonella typhimurium SlyA (NP_460407); SlyA_Efa, Enterococcus faecalis SlyA (NP_816617); MobR_Cte, Comamonas testosterone MobR (BAF34929); BadR_Rpa, Rhodopseudomonas palustris BadR (NP_946008); MoaI_Kae, Klebsiella aerogenes MoaI (BAA09790); and HpcR_Eco, Escherichia coli HpcR (AAB25801). C, The deduced amino acid sequence of Atu5212 (EstC) was aligned with EstC from Burkholderia gladioli EstC [38]. The Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad residues are indicated by asterisks. The bar above the sequences represents the esterase-lipase active domain. Alignment was performed using ClustalW [32].

Atu5211 is a transcriptional repressor of atu5212

One of the characteristics of the OhrR group of regulators is that they act as transcriptional repressors of the nearby target genes [2, 9, 13, 15, 16]. An analysis of the genes in proximity to atu5211 revealed that it located and transcribed divergently from atu5212, which encodes a conserved hypothetical protein of 229 amino acids. In addition, atu5211 is arranged head to tail with the atu5210-5209 operon [14]. If Atu5211 regulates the expression of atu5212 or atu5210-5209 operon, we would expect that inactivation of atu5211 should lead to an increase in its basal expression level. Thus, the expression levels of atu5212 and atu5210-5209 were determined in an atu5211 mutant and in its parent, NTL4 (data not shown). Only the atu5212 basal expression levels were increased more than 10-fold in the atu5211 mutant. The expression of atu5210 did not significantly increase in the mutant compared to NTL4. This indicates that Atu5211 acts as a transcription repressor of atu5212 expression.

atu5210, atu5211 and atu5212 are designated scd, estR and estC

A KEGG SSDB search [17] for orthologous proteins of Atu5212 in closely related bacteria revealed that this putative protein was an N-terminally truncated protein compared to other orthologous proteins that share high scores of identity. Analysis of nucleotide sequences upstream of the putative translation initiation (GTG) suggested a new potential ATG codon located 105 nucleotides from the original annotated GTG. This places the start codon in a good position from the transcription start site of atu5212 determined in the estR-estC promoter characterization section. The re-annotated Atu5212 ORF encodes a 265-amino-acid protein. The NCBI conserved domain search [18] of the deduced amino acid sequence of Atu5212 identified two domains of the esterase-lipase superfamily and the C-C hydrolase MhpC. Scanning for the active domain using InterProScan [19] demonstrated a lipase serine active site domain (IPR008262) located at amino acid residues 95–104 (VILVGHSWGG), which consists of a catalytic triad of nucleophile-His-acid amino acid [12] as Ser101-Asp213-His239 (Fig 1C). The nucleophilic serine is situated in a highly conserved GXSXG pentapeptide motif that corresponds to the sequence motif GHSWG in Atu5212. In addition, the conserved CGHWA/T motif of the MhpC family was absent from the Atu5212 sequence [20]. These features, together with the amino acid sequence surrounding the active His239, ASH239AL, suggests that Atu5212 belongs to an esterase-lipase family rather than an MhpC family. Henceforth, the Atu5212 is designated as EstC. The data from the expression pattern of estC indicated that Atu5211 acts as a transcriptional repressor of estC; hence, atu5211 is designated estR for "regulator of an esterase gene". The BLAST search of the Atu5210 sequence indicates it has homology to a family of short chain dehydrogenases and thus is designated Scd.

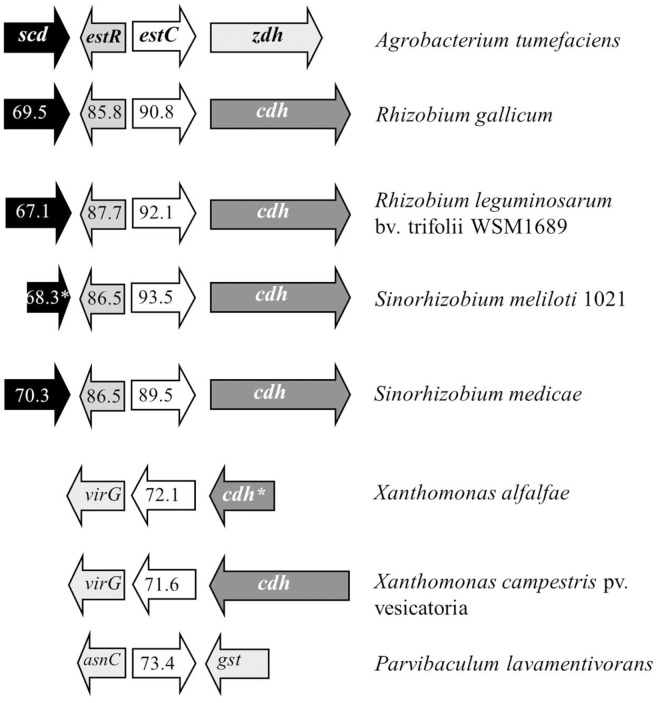

Genome organization of scd-estR-estC

Analysis of the genome organization of these genes in different bacteria revealed a conserved organization that showed estC homologous genes located next to the ORFs that shared roughly 90% identity to estR (Fig 2). The gene arrangement consisting of scd (short chain dehydrogenase)-estR-estC-zdh or cdh (zinc or choline dehydrogenase) is well conserved in Rhizobium and Agrobacterium bacteria. The genes within this arrangement also shared a high percent identity within the bacterial groups. This conserved gene organization in these bacteria raised the possibility that it could arise from horizontal gene transfer among alphaproteobacteria living in soil.

Fig 2. Gene organization of the estC locus in various bacteria.

The arrow indicates the orientation of the transcription. The number in the arrows represents percentage of identity of each sequence to the corresponding A. tumefaciens genes. The asterisk indicates a truncated gene. scd, short chain dehydrogenase; zdh, zinc dehydrogenase; cdh, choline dehydrogenase; and gst, glutathione S-transferase.

Nevertheless, ORFs sharing greater than 70% amino acid sequence identity to A. tumefaciens EstC are found in non-alphaproteobacteria, including Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria (XCV2148), Xanthomonas alfalfa and Parvibaculum lavamentivorans (Fig 2). In these phylogenetically distant bacteria, the estC homologs are not always located next to EstR homologs (Fig 2). In Xanthomonas spp., estC is organized in head-to-tail fashion with the cdh genes.

estC encodes an esterase

Analysis of the EstC sequence suggests that it encodes an esterase/lipase enzyme. The observation was extended by investigating the enzymatic activity of EstC. The C-terminal 6×His-tagged EstC fusion protein was purified from E. coli using Ni-NTA affinity column chromatography. The purity of EstC was greater than 95% as estimated by densitometric scanning of the Coomassie blue stained protein in polyacrylamide gels (as shown in S1 Fig). The esterase activity of purified EstC was measured using several p-nitrophenyl ester substrates including p-nitrophenyl butyrate (C4), p-nitrophenyl decanoate (C10), and p-nitrophenyl palmitate (C16) in assay reactions performed as previously described [21] and in the Methods section. EstC had minimal activity when p-nitrophenyl decanoate (C10, 3,446 ± 301 U mg-1 protein) and p-nitrophenyl palmitate (C16, 295 ± 86 U mg-1 protein) were used as substrates. The results suggest, based on the EstC enzymatic efficiency towards different chain length substrates, that EstC is an esterase rather than a lipase.

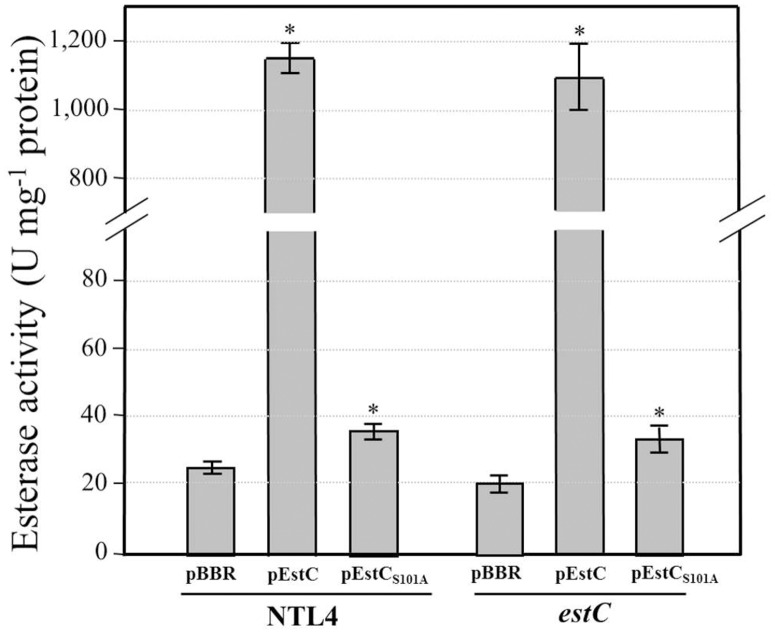

Esterase activity using p-nitrophenyl butyrate (C4) as the substrate was monitored in various A. tumefaciens strains. EstC mutant and estC high expression strains were constructed. The estC mutant strain showed 20% less esterase activity (19.8 ± 3.0 U mg-1 protein) than NTL4 (25.4± 1.9 U mg-1 protein). The complemented strain (estC/pEstC) produced 1,101 ± 94 U mg-1 protein, similar to the level, 1,149 ± 47 U mg-1 protein, attained in NTL4 harboring ectopic estC (NTL4/pEstC) (Fig 3). The finding that esterase activity was retained at relatively high levels in the estC mutant strongly suggested that A. tumefaciens produces other proteins with esterase activity. Analysis of the A. tumefaciens genome revealed the presence of an ORF (Atu5066) that shares 35% identity to EstC. Atu5066 is located on the pAT megaplasmid. Its function and gene regulation is being investigated. Analysis of the EstC primary amino acid sequence revealed a putative catalytic triad composed of Ser101-Asp213-His239. Ester hydrolysis is initiated by a nucleophilic attack of the catalytic site at a Ser residue, and the importance of Ser101 to the esterase activity was investigated by a site directed mutagenesis of estC that changed the active site Ser101 to Ala (S101A). The mutated estCS101A was cloned into an expression vector to generate pEstCS101A. This recombinant plasmid was transferred into NTL4, and the resulting esterase activity was determined. The NTL4 harboring pEstCS101A produced esterase activity of 35.6 ± 2.7 U mg-1 protein, whereas expression of wild-type estC expressed from the same plasmid vector (pEstC) generated 1,149 ± 47 U mg-1 protein esterase activity (Fig 3). This suggests that Ser101 plays a crucial role in the esterase activity of EstC.

Fig 3. Esterase activity in A. tumefaciens NTL4 and derivatives.

The esterase activity in NTL4 and the estC mutant strains harboring the pBBR1MCS-5 vector control (pBBR), pEstC or pEstCS101A was assayed in crude lysates prepared from exponential phase cultures. A unit of esterase activity is defined as the amount of enzyme capable of hydrolyzing p-nitrophenyl butyrate to generate 1 μmol of p-nitrophenol at 25°C. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05) from NTL4 or the estC mutant harboring vector control.

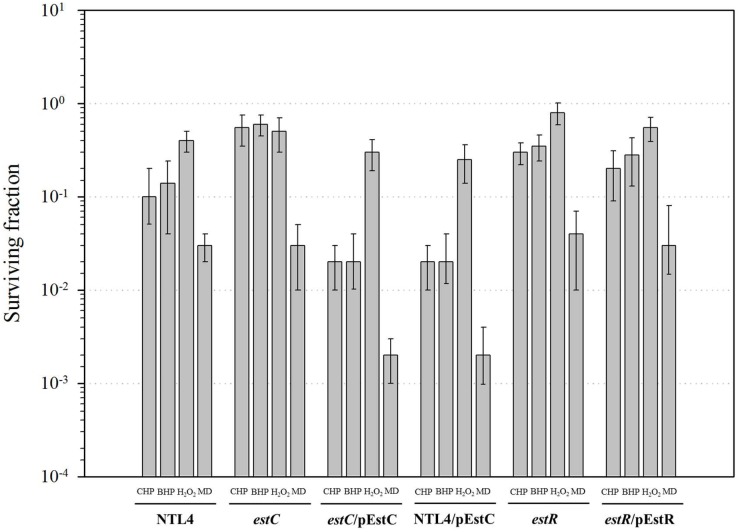

The phenotypes of estR and estC mutants

The finding that estC was regulated by estR, a putative organic hydroperoxide-inducible repressor, suggested that this gene system could have physiological roles in oxidative stress resistance. The resistance levels of A. tumefaciens NTL4 and the estC and estR mutants to oxidants were determined using plate sensitivity assays. The results showed that the estC mutant was 5-fold more resistant than NTL4 to cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) and t-butyl hydroperoxide (BHP), whereas the resistance levels toward H2O2 and superoxide generator menadione (MD) in NTL4 and the estC mutant were not significantly different (Fig 4). Moreover, we observed that in strains NTL4/pEstC and estC/pEstC, which highly expressed estC, were 10-fold less resistant to CHP, BHP and MD. An estR mutant had a small (less than 3-fold) decrease in the resistance levels to CHP, BHP and MD (Fig 4). The observations suggest that there are correlations between the expression levels of estC and the bacterial resistance levels to organic hydroperoxides.

Fig 4. Phenotypic analysis of A. tumefaciens NTL4 and derivatives.

The oxidant resistance levels of A. tumefaciens NTL4, the estC mutant, the complemented estC mutant (estC/pEstC), NTL4 harboring pEstC (NTL4/pEstC), the estR mutant, and the complemented estR mutant (estR/pEstR) were determined using plate sensitivity assays as described in the Methods. The concentrations of oxidant used are 0.25 mM CHP, 1.2 mM BHP, 0.35 mM H2O2, and 0.55 mM MD. The survival colonies were counted after 24 h incubation at 30°C. The surviving fraction is defined as the number of colony forming units (CFU) on plates containing oxidant divided by the number of CFU on plates without oxidant.

EstR regulates organic hydroperoxide-inducible estC and estR expression

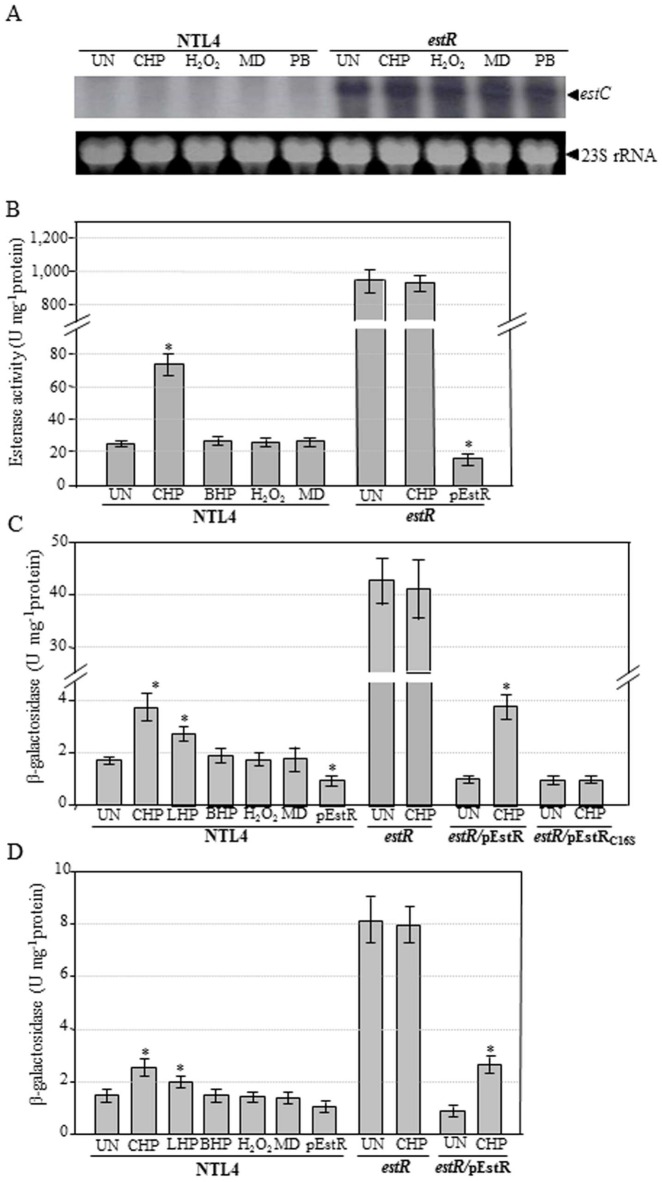

Transcriptional regulators of OhrR subgroup are involved in the regulation of organic hydroperoxide-inducible genes [22]. Previous findings in other bacteria indicate that OhrR homologs often regulate expression of genes in their close proximity. The Northern analysis of estC in RNA samples extracted from the NTL4 wild-type and an estR mutant cultivated under uninduced conditions and induced with oxidants was performed. In NTL4, the level of estC transcripts in the uninduced sample was too low to be detected by the Northern blot (Fig 5A). A barely detectable band of estC in the CHP induced RNA sample was observed, but not from other conditions (Fig 5A and S2 Fig). It was established that EstR was a repressor of estC. This notion was confirmed by Northern analysis of estC expression performed on RNA samples from the uninduced and oxidant induced cultures of the estR mutant. The results showed that in the mutant, estC expression was high in uninduced and in oxidant induced samples (Fig 5A).

Fig 5. Expression analysis of estC.

A, Northern analysis of estC in A. tumefaciens NTL4 wild-type and the estR mutant was performed using the [32P]-labeled estC probe. Equal amounts of RNA (10 μg) prepared from bacterial cultures grown under uninduced (UN) conditions or induced with 1 mM CHP, 250 μM H2O2, 200 μM MD or 250 μM plumbagin (PB) were used in the experiments. The 23S rRNA used as the amount control is shown below the hybridized autoradiograph. B, Esterase activity in A. tumefaciens NTL4 and the estR mutant strains was assayed in crude lysates prepared from cultures cultivated as described in A. BHP, culture induced with 500 μM t-butyl hydroperoxide. C and D show the estC and estR promoter activities in vivo, respectively, in NTL4, the estR mutant, and the complemented strain (estR/pEstR) carrying the plasmid either pPestC that contains the estC promoter-lacZ fusion (C) or pPestR that contains the estR promoter-lacZ fusion (D). The activities were monitored in samples of lysates prepared from uninduced (UN) and oxidant-induced cultures (1 mM CHP, 25 μM LHP, 500 μM BHP, 250 μM H2O2, and 250 μM MD). The β-galactosidase activity is expressed in international units. pEstR means harboring the estR expression plasmid. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (P < 0.05) from the uninduced control.

Because estC encodes an esterase, the total esterase activity of NTL4 uninduced and oxidant induced cultures was assayed. As expected, CHP treatment induced a 3-fold increase in the total esterase activity (73.0 ± 6.8 U mg-1 protein) compared with the uninduced level (25.4 ± 1.9 U mg-1 protein) in NTL4 (Fig 5B). Treatment of cultures with other oxidants, including BHP, H2O2 and MD, did not induce the esterase activity. The total esterase activity was determined in cultures of the estR mutant. The results showed that the estR mutant had 37-fold more total esterase activity compared to NTL4 (Fig 5B). No significant induction of esterase activity by CHP treatment of the mutant was observed.

Next, estC promoter activity was measured in vivo using the estC promoter-lacZ fusion. The plasmid pPestC carrying the estC promoter fragment fused to lacZ was introduced into NTL4 and the estR mutant. The level of β-galactosidase activity was monitored in uninduced and CHP induced NTL4/pPestC (Fig 5C). Significant induction of β-galactosidase activity was detected in NTL4/pPestC treated with CHP (3.7 ± 0.4 U mg-1 protein) compared with the uninduced sample (1.8 ± 0.3 U mg-1 protein) (Fig 5C). CHP-induced estC expression was abolished in the estR mutant. The level of β-galactosidase activity in estR/pPestC was constitutively high (Fig 5C). In the estR complemented strain (estR/pPestR), the estC promoter activity (1.0 ± 0.1 U mg-1 protein) dropped to a level below the NTL4 level (1.8 ± 0.3 U mg-1 protein) and 40-fold below the level attained in the estR mutant strain (43.0 ± 4.4 U mg-1 protein) (Fig 5C). CHP treatment was able to induce the expression of the estC promoter in estR complemented strain (Fig 5C). Taken together, the results support the role of EstR as an organic hydroperoxide sensor and repressor of estC.

Nonetheless, the inability of BHP treatment to induce estC expression even at a high concentration (1 mM) was unexpected. Together with the fact that the maximal level of estC promoter activity in NTL4 induced with CHP (3.7 ± 0.4 U mg-1 protein) was much lower than in the estR mutant (43.3 ± 4.4 U mg-1 protein), the question arose whether organic hydroperoxide is the preferred inducer of estC. A number of substances were tested for their ability to induce estC expression using pPestC, a lacZ fusion construct. The results indicated that cumyl alcohol (a compound structurally related to CHP and a metabolite of CHP metabolism), salicylic acid (a strong inducer of the MarR transcription regulator), perbenzoic acid, methyl jasmonate (an ester substance that plants produce as a signal molecule during plant-microbe interaction), the esterase substrates (p-nitrophenyl butyrate, p-nitrophenyl decanoate, and p-nitrophenyl palmitate), and linoleic acid failed to induce estC expression (data not shown). Moreover, oxidants, including H2O2 and MD, failed to induce the expression of lacZ from pPestC in NTL4 (Fig 5C). Treatment of NTL4/pPestC with 25 μM linoleic hydroperoxide (LHP) induced moderate levels of estC expression (2.7 ± 0.3 U mg-1 protein), while no induction was observed in BHP-treated cells (Fig 5C). The results suggest that EstR could be more readily oxidized by the hydrophobic organic hydroperoxides (CHP and LHP) leading to its structural alteration and subsequent inability to bind to operator sites. This allows inducible estC expression. A less hydrophobic organic hydroperoxide such as BHP could not efficiently oxidize the regulator and hence would be unable to induce the expression of the gene.

The expression of genes in the marR family is typically autoregulated [13, 23, 24]. To test whether estR regulates its own expression in vivo, a promoter analysis using a promoter-lacZ gene fusion was conducted. A pPestR plasmid that contains a putative estR promoter sequence transcriptionally fused to a promoterless lacZ was introduced into A. tumefaciens NTL4 and the estR mutant. The levels of β-galactosidase activity in lysates prepared from cultures of NTL4 and the estR mutant harboring pPestR grown under uninduced and oxidant induced conditions were monitored. The estR promoter activity in NTL4 was induced only in cells treated with CHP (Fig 5D). CHP induced a 1.6-fold increase in β-galactosidase activity relative to the uninduced sample. The estR promoter was constitutively active in the estR mutant compared to that in the wild-type (Fig 5D). The promoter activity of estR in the complemented strain (estR/pEstR) showed that pEstR could repress the constitutively high activity of the estR promoter in the estR mutant to the level attained in the NTL4 strain (Fig 5D). It is noteworthy that a high expression level of estR in the NTL4/pEstR lowered the level of estR promoter activity (Fig 5D). This is consistent with the notion that higher levels of the repressor lead to greater repression of target gene expression. The evidence supports the role of EstR as an autoregulated, organic hydroperoxide-inducible, transcriptional repressor.

We extended the investigation to determine whether EstR would cross regulate ohr expression using an estR mutant. The transcription activity of pPohr [2] that had the ohr promoter transcriptionally fused to a lacZ reporter gene in the mutant (estR/pPohr) and in NTL4 (NTL4/pPohr) was determined under uninduced and organic hydroperoxide induced conditions by monitoring β-galactosidase activity. As expected, β-galactosidase activities showed CHP induction in both estR and NTL4 suggesting that estR plays no role in ohr expression (data not shown). There is no cross-regulation between the two members of the MarR family.

EstR senses organic hydroperoxides through Cys16

EstR possesses a conserved sensing cysteine residue at position 16 (Cys16). We tested whether Cys16 of the EstR is involved in organic hydroperoxide sensing mechanism by constructing a site specific mutation changing Cys16 to serine (C16S). The plasmid pEstRC16S was introduced into the estR mutant harboring pPestC. As shown in Fig 5C, the basal level of estC promoter activity in estR/pEstRC16S/pPestC was similar to the level attained in the estR/pEstR/pPestC strain. Thus, the mutation C16S did not affect the ability of EstRC16S to bind to operator regions and repress estC gene expression. Nevertheless, no CHP-induced estC promoter activity was observed in the estR mutant expressing estRC16S, indicating that Cys16 of EstR has a crucial role in the organic hydroperoxide sensing process. The mutant complemented with wild type estR (estR/pPestC/pEstR) showed CHP induction of the promoter (Fig 5C). Other transcriptional regulators in the OhrR group, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa OspR [22] and Staphylococcus aureus AbfR [25], also show peroxide or oxidant sensing processes that occur through the initial oxidation of the sensing cysteine residue located near the N-terminus [26]. In the 2-Cys group of OhrR, after the initial oxidation of the sensing Cys by organic hydroperoxide, there are important amino acids residues, including Tyr36 and Tyr47, involved in sensing oxidized Cys and maintaining the hydrogen bond environment around the sensing Cys. These amino acids are important for the subsequent formation of a disulfide bond with a resolving Cys near the carboxyl terminus and for the accompanying structural changes. These conserved residues are also found in EstR.

The data clearly show that the oxidation of the sensing residues of EstR is required to initiate structural modifications that prevent the repressor from binding to the operator sites. Hence, molecules that do not have a hydroperoxide moiety could not act as inducers of the EstR system. Interestingly, the pattern of induction of A. tumefaciens OhrR and EstR are clearly different. OhrR can be oxidized by simple BHP [2], whereas EstR can only be oxidized by higher concentrations and by more hydrophobic hydroperoxides, including CHP and LHP. Analysis of the structure of a 2-Cys member of OhrR reveals the sensing Cys residue (corresponding to Cys16 in EstR) buried down in a hydrophobic pocket [8]. This is thought to favor the hydrophobic organic hydroperoxide to move down the pocket and oxidize the sensing Cys residue, which accounts for the observation that organic hydroperoxides are more efficient inducers than H2O2. It is possible that in EstR the sensing Cys (C16) is less accessible and coupled with a regulator that might have a higher oxidation potential than A. tumefaciens OhrR so that it could be oxidized only by either relatively higher concentrations or more hydrophobic organic hydroperoxides.

Characterization of the estR-estC promoters

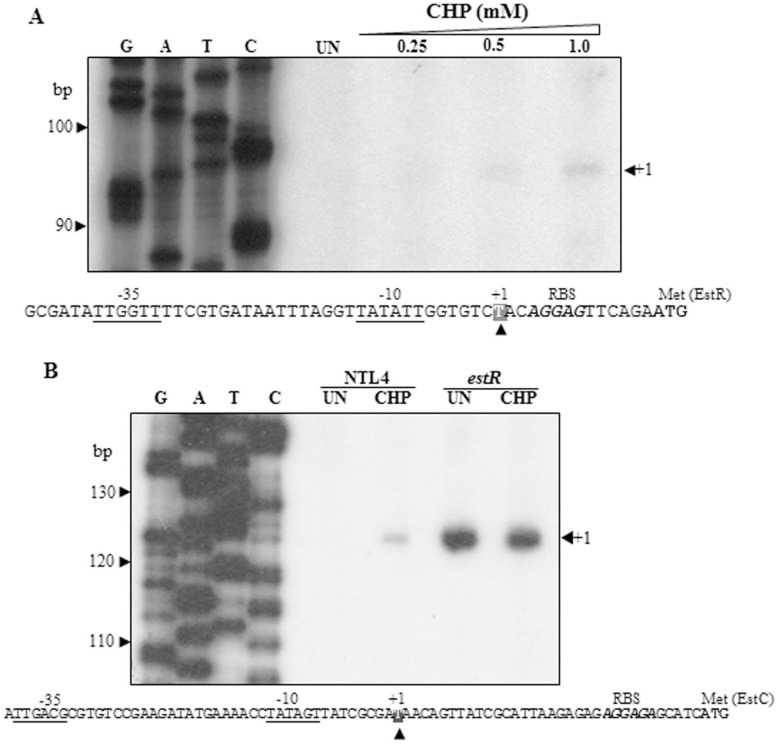

The 5’ end of the estR transcript was determined using primer extension with the [32P]-labeled BT1575 primer and total RNA extracted from NTL4 wild-type uninduced cultures and cultures induced with various concentrations of CHP. The extension products were separated by denaturing PAGE. As shown in Fig 6A, a principal primer extension product of 95 nucleotides was detected in RNA samples from the cultures induced with 0.5 and 1 mM CHP. No primer extension products could be detected in the RNA from uninduced cultures or cultures induced with 0.25 mM CHP. The size of the RNA product corresponded to transcription initiation at the T residue located 14 bases upstream of the ATG codon. The E. coli RNA polymerase σ 70-like -35 and -10 sequence elements, TTGGTT and TATATT, separated by 17 bases could be found upstream of the +1 site. The primer extension results are in good agreement with the results of the estR-lacZ promoter fusion (Fig 5D). Interestingly, the concentrations of CHP required to induce estR expression were relatively high (1 mM) compared with the concentration (50 μM) required for the induction of ohrR expression [2].

Fig 6. Characterization of the estR and estC promoters.

Primer extension experiments with estR (A) and estC (B) were conducted using mRNA from A. tumefaciens NTL4 and the estR mutant. The experiment was performed using the [32P]-labeled BT1575 primer for estR and the BT1574 primer for estC and 5 μg total RNA extracted from uninduced (UN) or CHP-induced cultures. G, A, T, C are sequence ladders of pGEM-3Zf (+) prepared using the pUC/M13 forward primer, and numbers represent the size in base pairs of the sequencing products. +1 indicates the transcription start site. The -10 and -35 regions are underlined. RBS and Met represent the ribosome binding site and the translation start site, respectively.

To characterize the estC regulatory elements, the transcription start site of estC was mapped using primer extension experiments performed with [32P]-labeled BT1574 and RNA samples prepared from the cultures of either NTL4 or the estR mutant. The extension product of 123 nucleotides corresponded to the putative +1 of estC located at T, 34 nucleotides upstream of the ATG translational start codon of estC. The putative -10 and -35 elements of the estC promoter were mapped as TATAGT and TTGACG, respectively, separated atypically by 20 bp (Fig 6B). The primer extension results showed that the RNA from CHP induced cultures produced much higher level primer extension products than the samples from uninduced cultures. This supported the results of the Northern blot analysis, the estC promoter fusion analysis and the total esterase assays showing that estC expression was inducible by CHP treatment. Experiments showed that the estR mutant exhibited constitutively high levels of estC primer extension products in RNA samples from both uninduced and CHP-induced cultures (Fig 6B). The levels were more than 30-fold higher than the level attained in NTL4, confirming the results of the Northern analysis of estC expression, the estC promoter fusion and the esterase activities in the estR mutant.

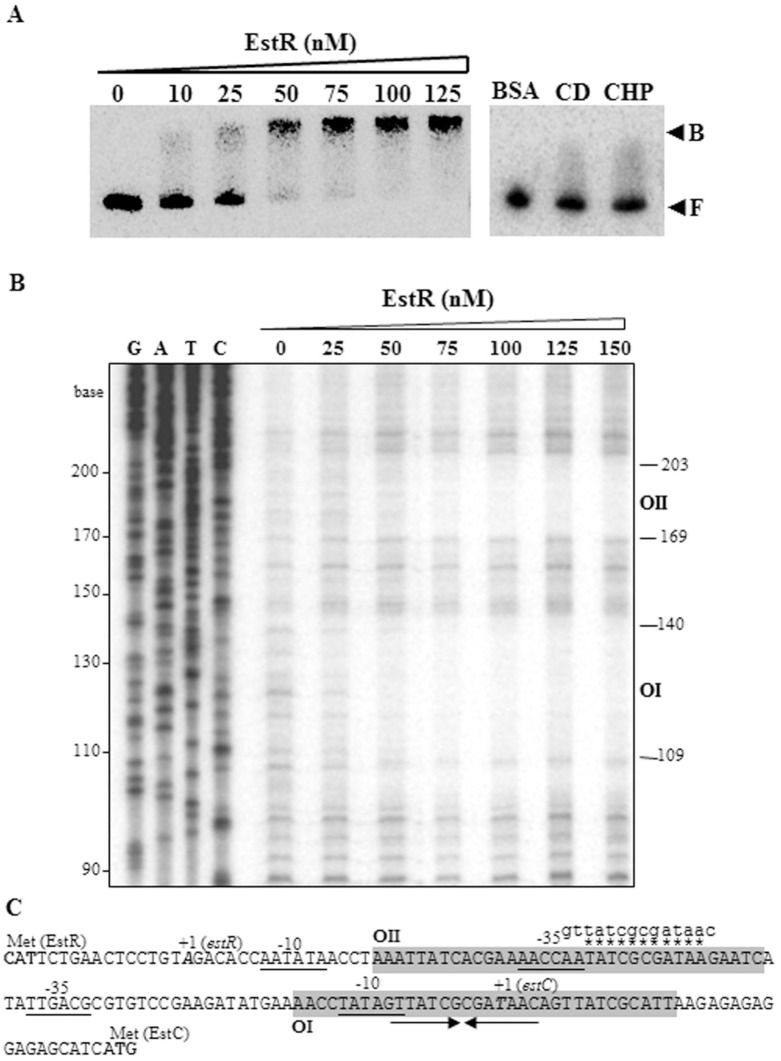

Binding of purified EstR to the estR and estC promoters

The expression profiles of estR and estC strongly suggest that these two promoters are under the control of EstR. To assess the ability of purified EstR protein to bind to the estR and estC promoter regions, DNA mobility shift assays were conducted. EstR protein was purified using a heparin column, and its purity was assessed to be greater than 90% (S3 Fig). With regard to the estC and estR promoter characterization, the -35 elements of estR and estC are separated by 19 bases, hence the 314-bp DNA sequence encompassing both promoters was used in the experiment. Purified EstR protein (10–125 nM) was incubated with the [32P]-labeled promoter fragment in a binding buffer. The protein-DNA complex was observed at an EstR concentration of 25 nM and was maximal at 100 nM (Fig 7A). The binding affinity of purified EstR is similar to previously characterized OhrR members binding to their operators [2, 27, 28]. The specificity of the EstR binding was evaluated, and the results illustrated that cold promoter fragments competed with the labeled fragment for binding to the EstR protein, whereas an unrelated protein (BSA) was unable to bind the promoter fragment (Fig 7A). The results indicate that purified EstR protein specifically binds to the estR-estC promoter fragment in vitro. Binding of EstR therefore represses the expression of estC as well as its own expression. To ascertain whether CHP treatment is able to release the EstR from the promoter, the complex was exposed to 1 mM CHP. As shown in Fig 7A, prior CHP treatment of EstR prevented the repressor from binding to the promoter fragment as shown by the absence of the complex. Thus, induction of estC and estR by CHP is a consequence of the oxidation and subsequent structural changes of EstR that prevent the repressor from binding to the promoters, thereby allowing transcription of estC and estR. The observation fits well with the model of OhrR transcriptional repressors that the reduced repressor binds to the operator and inhibits transcription of the target promoter. The precise location of the EstR operator sites within the estR-estC intergenic region was determined by DNaseI footprinting using purified EstR and the [32P]-314-bp estR-estC promoter fragment. Binding reactions containing various concentrations of purified EstR were digested with DNaseI. The results demonstrated that EstR bound to two sites in the intergenic region of the estR-estC promoter in a region of +16 to -18 (site OI) and -46 to -82 (site OII) of the estC promoter (Fig 7B). The EstR operator binding site OI covered the -10 motif of the estC promoter. The binding of EstR to the OI site would block the binding of RNA polymerase to the estC promoter (Fig 7C). The EstR operator site OII overlaps with the -35 region of the estR promoter (Fig 7C). Hence, binding of EstR to OII blocks the -35 region of the promoter and prevents RNA polymerase from binding to the promoter. The binding affinities of EstR to OI and OII were slightly different. The DNaseI protection was observed at EstR concentrations of 50 nM and 75 nM for binding at OI and OII, respectively. This suggests that EstR binds to OI at a higher affinity than OII. Analysis of OI and OII revealed the presence of a 14-base-pair palindromic sequence, GTTATCGCGATAAC, and a homologous sequence, AATATCGCGATAAG, respectively (Fig 7C). The palindromic EstR operators OI and OII are quite different from the OhrR OI binding site (TACAATT-AATTGTA) identified in A. tumefaciens [2]. This is likely to be responsible for the observed lack of cross regulation between OhrR and EstR (data not shown). The EstR dual operator sites model here is distinct from the previously characterized A. tumefaciens OhrR regulation of the ohrR-ohr promoter region where only a single OhrR operator site regulates transcription of both ohr and ohrR [2].

Fig 7. Gel mobility shift assays and DNase I footprinting of EstR bound to the estR-estC promoters.

A, Gel mobility shift assays of the [32P]-labeled 314-bp DNA fragment spanning the estR and estC promoters with purified EstR protein (0–125 nM) were performed. The complexes were separated on native PAGE. The specificity of the binding was validated by adding the cold DNA fragment (CD) to the binding mixture or adding bovine serum albumin (BSA) to the reaction instead of the EstR protein. CHP represents the bound complexes treated with 1 mM CHP. B and F indicate bound and free probes, respectively. B, DNase I protection assays were performed with the [32P]- labeled estR-estC promoter fragment and purified EstR protein at the indicated concentrations. The digested and protected DNA fragments were separated on 8% denaturing DNA sequencing gels beside the sequence ladders (G, A, T, C) generated from pGEM-3Zf (+) using the pUC/M13 forward primer. The numbers on the left side are the size in base pairs of the bands. C, The depicted sequence shows the estR-estC promoter region. +1 and Met indicate the transcription and translation start sites. The -10 and -35 regions are underlined. RBS represents the ribosome binding site. The sequences corresponding to the sites of OI and OII protection are shaded. Arrows indicate palindromic sequences. Small letters above the sequence line represent the putative EstR binding box derived from site OI protection. Identical nucleotides are marked by asterisks.

Taken together, the results suggest that under physiological and uninduced conditions, EstR binds to the operator sites, resulting in steric hindrance of RNA polymerase binding to both the estR and estC promoters and thereby repressing their transcription. Upon exposure to organic hydroperoxide, oxidation of EstR decreases the concentration of reduced EstR and the binding of reduced EstR to the estC operator site OI and the estR operator site OII. This allows expression of estC and estR. As the concentration of inducer declines and the concentration of reduced EstR concomitantly increases, the repressor separately binds to both operators, repressing the expression of both genes and returning the expression of both genes to the uninduced state.

Methods

Bacterial growth conditions

Agrobacterium tumefaciens NTL4, a pTiC58-cured derivative of C58, ΔtetC58 [29], and its mutant and complemented derivatives were cultivated in Lysogeny Broth (LB) medium and incubated aerobically at 28°C with continuous shaking at 150 rpm. The overnight cultures were inoculated into fresh LB medium to give an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1. Exponential phase cells (OD600 of 0.6 after 4 h of growth) were used in all experiments. The oxidant-induced experiments were performed by challenging the exponential phase cultures with 250 μM to 1.0 mM cumene hydroperoxide (CHP), 250 μM H2O2, 500 μM tert-butyl hydroperoxide (BHP) or 200 μM menadione (MD) for 15 min for Northern analysis and 30 min for enzymatic assays.

Molecular biology techniques

General molecular genetics techniques, including genomic and plasmid DNA preparation, RNA preparation, Southern and Northern blot analyses, PCR, cloning, transformation into Escherichia coli, and gel electrophoresis, were performed using standard protocols [30]. A. tumefaciens was transformed by electroporation [29].

Alignments and phylogenetic analyses

Amino acid sequences were retrieved from the GenBank database [31]. The alignments were performed by using the multiple alignment feature of ClustalW version 2.0.12 [32] with maximal fixed-gap and gap extension penalties and displayed using ESPript 3.0 (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/cgi-bin/ESPript.cgi). A phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method based on ClustalW analysis data and displayed using PHYLODENDRON, version 0.8d (D.G. Gilbert, Department of Biology, University of Indiana, USA at http://iubio.bio.indiana.edu).

Primer extension

Total RNA was extracted from wild-type A. tumefaciens and from the estR mutant cultivated under uninduced and cumene hydroperoxide-induced conditions. Primer extension experiments were performed using the primers [32P]-labeled BT1574 (for estC) or BT1575 (for estR) (see Table 1), 5 μg total RNA, and 200 U superscript III MMLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, USA). Extension products were analyzed on 8% acrylamide-7 M urea gels with sequencing ladders generated using a PCR sequencing kit with labeled M13F primer and pGem3Zf(+) plasmid as the template.

Table 1. List of primers.

| Primer | Sequence (5’→3’) |

|---|---|

| BT493 | CAGGAGTTCAGAATGACCA |

| BT494 | TACTCTTGCAGGTCAGGC |

| BT1505 | ATCGCTGAGACAGCCTGC |

| BT1506 | GGCGGAAGACGAGCAGAC |

| BT1507 | CTCCGGACGCCGGCGAGAC |

| BT1508 | CTTGGTGCCGAACGCAGAC |

| BT1559 | CCGATGGCGCGACGTCGATCATTGC |

| BT1574 | GTGTCGGCTGCATTCGCTGC |

| BT1575 | CTGGATAGCGATGCCTGCGG |

| BT1595 | CGCGTGTCCGAAGATATGAAAACCTA |

| BT1621 | TCAGGTACCCCAAACGCGAT |

| BT1622 | CTCTTCGAAGTCAGGCGGG |

| BT1632 | CACCATGGCACGCAAGTCCAT |

| BT1633 | GTGAGCTCTTGCTTTTTTGCTG |

| BT1662 | GCCCCAGGCATGTCCGACGAG |

| BT1663 | GTCGGACATGCCTGGGGCGGA |

| BT3859 | CTGCGCGACCAGCTCAGCTATGCT |

| BT3860 | TATAAATAGCATAGCTGAGCTGGT |

| M13F | GTAAAAGGACGCCCAGT |

Construction of A. tumefaciens estR and estC mutants

The A. tumefaciens estR mutant was constructed by insertional inactivation using the pKnock suicide vector [33]. An internal fragment of the estR gene was PCR amplified with the primers BT1505 and BT1506 (see Table 1) and A. tumefaciens genomic DNA as the template. The 199-bp PCR product was cloned into pDrive (Qiagen, France), and the nucleotide sequence of the insert was determined to assure it was indeed an estR fragment. Then, a BamHI-HincII fragment was subcloned into pKnock-Gm digested with the same enzymes to form pKnockestR. This recombinant plasmid was transferred into A. tumefaciens and selected for the gentamicin resistance (Gmr) phenotype. The estR mutant was confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

The estC mutant was constructed using the same protocol described for the estR mutant. The estC fragment was amplified with the BT1507 and BT1508 primers (see Table 1) and cloned into pDrive. An EcoRI fragment was then subcloned into pKnock-Km [33] at the EcoRI site. The estC mutant was selected for kanamycin resistance (Kmr) and verified by Southern blot analysis.

Construction of the pEstR, pEstRC16S, pEstC and pEstCS101A expression plasmids

To construct the pEstR expression plasmid, the full-length gene was amplified from A. tumefaciens genomic DNA with the primers BT493 and BT494 corresponding to the Atu5211open reading frames [14]. The PCR product was cloned into the cloning vector pGemT-Easy (Promega, USA) before the nucleotide sequence was determined. The ApaI-SacI fragment was then subcloned into the broad-host-range plasmid pBBR1MCS-5 [34] digested with the same enzymes to yield pEstR.

The plasmid pEstRC16S that expresses the mutant EstRC16S in which Cys16 was exchanged to Ser, was constructed using PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis [7]. The mutagenic forward (BT3859) and reverse (BT3860) primers designed to change the Cys16 codon to Ser were used to amplify the pEstR plasmid. The PCR products were cut with ApaI-SacI and ligated with similarly digested pBBR1MCS-5 [34]. The sequence of the mutated bases was verified using DNA sequencing.

The pEstC plasmid was constructed by amplification of the full-length estC gene (Atu5212) with the primers BT1559 and BT1595. The PCR product was cloned into pDrive, sequenced, and finally, the ApaI-PstI fragment was subcloned into pBBR1MCS-3 [34] cut with the same enzymes to form pEstC.

The pEstCS101A plasmid containing mutated EstC, in which Ser-63 was changed to Ala, was constructed using site-directed mutagenesis as described for the pEstRC216S construction. The PCR products amplified from pEstC with the mutagenic forward (BT1663) and reverse (BT1662) primers were cut with ApaI-PstI and ligated with similarly digested pBBR1MCS-3 [34].

Construction of estC- and estR-promoter lacZ fusions

The estC and estR intergenic region, which contains putative estC and estR promoters located in opposite directions, was PCR amplified from NTL4 genomic DNA using the primers BT1574 and BT1575. The 314-bp PCR product was cloned into pGemT-Easy. The inserted DNA was sequenced to verify the correctness of the promoter. Then, an EcoRI fragment was cloned into EcoRI-cut pUFR047lacZ [4] containing a promoterless lacZ, yielding the pPestC and pPestR plasmids containing estC promoter-lacZ and estR promoter-lacZ fusions, respectively.

Purification of EstC and EstR

The C-terminal His-tagged EstC protein was purified using the pETBlue-2 system (Novagen, Germany). An 810-bp full-length estC was amplified with primers BT1632 and BT1633 (see Table 1), and the NcoI-XhoI cut fragment was cloned into pETBlue-2 digested with the same enzymes, resulting in pETestC. E. coli BL21 (DE3) harboring pETestR was grown to exponential phase before being induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 2 h. The bacteria were harvested and lysed by sonication. The clear lysate was loaded onto a Ni-NTA column (Qiagen, France). The EstC protein was eluted with a linear gradient of 0 to 100 mM imidazole.

To the purified, non-tagged EstR protein, a 483-bp PCR fragment containing the full-length estR amplified using the BT1621 and BT1622 primers was cut with NcoI and HindIII and cloned into the similarly digested pETBlue-2 (Novagen, Germany), yielding pETestR. An exponential phase culture of BL21 (DE3) harboring pETestR was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 18 h before being collected and lysed. Streptomycin sulfate (2.5% w/v) was added to the clear lysate to precipitate the nucleic acids prior to precipitating the protein with 70% saturated ammonium sulfate. The precipitated protein was resuspended in TED buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1 mM NaCl), loaded onto an Affi-Gel heparin column (Bio-Rad, USA), and washed extensively with TED buffer. Proteins were eluted from the column with a linear gradient of 0 to1.0 M NaCl. Fractions containing EstR were pooled and loaded onto a Q-Sepharose column (Amersham Bioscience, USA). Bound proteins were eluted a linear gradient of 0 to1.0 M NaCl. The eluted fraction containing EstR was dialyzed with TED buffer and concentrated by ultrafiltration (Amico Ultra-10K, Millipore, Germany). Purified protein was aliquoted and stored at -20°C. The purity of the purified protein was estimated from densitometric analysis of Coomassie blue stained gels after SDS-PAGE. Majority of the purified EstR presents in a reduced form as judged by nonreducing SDS-PAGE (data not shown).

Gel mobility shift assay

BT1574 was 5’ end-labeled with [γ-32P] dATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega, USA). The [32P]-labeled estR and estC promoter fragments were amplified with [32P]-labeled BT1574 and BT1575 primers (see Table 1) and with pPestC as the DNA template. Gel mobility shift reactions were performed in a 25 μl reaction mixture consisting of 3 fmol [32P]-labeled 314-bp PCR product, purified EstR (5–18 ng) and 1× binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 50 mM KCl, 50 μg ml-1 BSA, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT). The binding was allowed to proceed at 25°C for 15 min. Protein-DNA complexes were separated by electrophoresis on 5% native polyacrylamide gels in Tris borate EDTA buffer (TBE) at 4°C.

DNaseI foot printing

The DNaseI foot printing assay was performed in a 50 μl reaction mixture containing 1× binding buffer (20 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.0, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 50 μg ml-1 BSA, 5 μg ml-1 calf thymus DNA and 0.1 mM DTT), 500 ng poly(dI-dC), 20 ng [32P]-labeled estR and estC promoter fragments prepared as described for the gel mobility shift assay, and purified EstR at the indicated concentrations. The binding mixture was held at room temperature for 15 min. Fifty microliters of solution containing 5 M CaCl2 and 10 mM MgCl2 was added to the reaction prior to digesting it with 0.5 unit DNaseI for 30 s. Reactions were stopped by adding 700 μl stop solution (645 μl ethanol, 50 μl 3 M sodium acetate, and 5 μl 1 mg ml-1 yeast tRNA). The DNA was recovered by centrifugation for 15 min and resuspended in formamide loading buffer before being loaded onto 8% denaturing sequencing gels alongside the sequencing ladder created by PCR extension of the labeled M13F primer using pGem3ZF (+) as a template.

Plate sensitivity assay

The resistance levels against oxidants were measured using plate sensitivity assays [6]. Serial dilutions of exponential phase cultures were made in LB broth, and 10 μl of each dilution was spotted on LB agar plates containing various oxidants, including CHP, BHP, MD, and H2O2. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h before the colonies were counted. Experiments were performed in triplicate and the mean and standard deviation (SD) are shown.

Enzymatic assays

Crude bacterial lysates were prepared, and protein assays were performed as previously described [35]. The total protein concentration in the cleared lysates was determined by a dye binding method (BioRad, USA) prior to their use in enzyme assays. β-galactosidase assays were performed using o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactoside (ONPG) as a substrate, as previously described [36]. One international unit is the amount of enzyme generating 1 μmol of o-nitrophenol per min at 25°C [37]. Esterase activity was measured as previously described [21]. One esterase unit is defined as the amount of enzyme that liberates 1 μmol of p-nitrophenol per min at 25°C. Data shown are mean ± SD of triplicate experiments.

Statistical analysis

The significance of differences between strains or cultured conditions was statistically determined using Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 is considered significant difference.

Supporting Information

Purified EstC was separated by 15% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with coomassie blue. Lane 1, lysate from culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETBlue-2 vector; Lane 2, lysate from uninduced culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETestR; lane 3, lysate from IPTG-induced culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETestR; lane 4 and 5, washing column fractions; lane 6, purified EstC.

(EPS)

Northern analysis of estC in A. tumefaciens NTL4 wild-type was performed using the [32P]-labeled estC probe and 20 μg of total RNA. UN, uninduced; CHP, induction with 1 mM CHP. The 23S rRNA used as the amount control is shown below the hybridized autoradiograph.

(EPS)

Purified EstR was separated by 15% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with coomassie blue. Lane 1, lysate from uninduced culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETestR; lane 2, lysate from IPTG-induced culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETestR; lane 3, purified EstR.

(EPS)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the Chulabhorn Research Institute, Mahidol University, and the Center of Excellence on Environmental Health and Toxicology (EHT), Ministry of Education, Thailand (EHT-R 1/2556-1). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Levine A, Tenhaken R, Dixon R, Lamb C. H2O2 from oxidative burst orchestrates the plant hypersensitive disease resistance response. Cell. 1994;79:583–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chuchue T, Tanboon W, Prapagdee B, Dubbs JM, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. ohrR and ohr are the primary sensor/regulator and protective genes against organic hydroperoxide stress in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(3):842–51. 10.1128/JB.188.3.842-851.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eiamphungporn W, Charoenlap N, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. Agrobacterium tumefaciens soxR is involved in superoxide stress protection and also directly regulates superoxide-inducible expression of itself and a target gene. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(24):8669–73. 10.1128/JB.00856-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakjarung K, Mongkolsuk S, Vattanaviboon P. The oxyR from Agrobacterium tumefaciens: evaluation of its role in the regulation of catalase and peroxide responses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304(1):41–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saenkham P, Eiamphungporn W, Farrand SK, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. Multiple superoxide dismutases in Agrobacterium tumefaciens: functional analysis, gene regulation, and influence on tumorigenesis. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(24):8807–17. 10.1128/JB.00960-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prapagdee B, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. The role of a bifunctional catalase-peroxidase KatA in protection of Agrobacterium tumefaciens from menadione toxicity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;232(2):217–23. 10.1016/S0378-1097(04)00075-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panmanee W, Vattanaviboon P, Poole LB, Mongkolsuk S. Novel organic hydroperoxide-sensing and responding mechanisms for OhrR, a major bacterial sensor and regulator of organic hydroperoxide stress. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(4):1389–95. 10.1128/JB.188.4.1389-1395.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Newberry KJ, Fuangthong M, Panmanee W, Mongkolsuk S, Brennan RG. Structural mechanism of organic hydroperoxide induction of the transcription regulator OhrR. Mol Cell. 2007;28(4):652–64. Epub 2007/11/29. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuangthong M, Atichartpongkul S, Mongkolsuk S, Helmann JD. OhrR is a repressor of ohrA, a key organic hydroperoxide resistance determinant in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(14):4134–41. 10.1128/JB.183.14.4134-4141.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmann JD. Bacillithiol, a new player in bacterial redox homeostasis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15(1):123–33. Epub 2010/08/18. 10.1089/ars.2010.3562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soonsanga S, Lee JW, Helmann JD. Conversion of Bacillus subtilis OhrR from a 1-Cys to a 2-Cys peroxide sensor. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(17):5738–45. Epub 2008/07/01. 10.1128/JB.00576-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmquist M. Alpha/Beta-hydrolase fold enzymes: structures, functions and mechanisms. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2000;1(2):209–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukchawalit R, Loprasert S, Atichartpongkul S, Mongkolsuk S. Complex regulation of the organic hydroperoxide resistance gene (ohr) from Xanthomonas involves OhrR, a novel organic peroxide-inducible negative regulator, and posttranscriptional modifications. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(15):4405–12. 10.1128/JB.183.15.4405-4412.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood DW, Setubal JC, Kaul R, Monks DE, Kitajima JP, Okura VK, et al. The genome of the natural genetic engineer Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science. 2001;294(5550):2317–23. 10.1126/science.1066804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh SY, Shin JH, Roe JH. Dual role of OhrR as a repressor and an activator in response to organic hydroperoxides in Streptomyces coelicolor. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(17):6284–92. 10.1128/JB.00632-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atichartpongkul S, Fuangthong M, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. Analyses of the regulatory mechanism and physiological roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa OhrR, a transcription regulator and a sensor of organic hydroperoxides. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(8):2093–101. Epub 2010/02/09. 10.1128/JB.01510-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Nakaya A. The KEGG databases at GenomeNet. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):42–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marchler-Bauer A, Anderson JB, Derbyshire MK, DeWeese-Scott C, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, et al. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D237–40. 10.1093/nar/gkl951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W116–20. 10.1093/nar/gki442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li C, Hassler M, Bugg TD. Catalytic promiscuity in the alpha/beta-hydrolase superfamily: hydroxamic acid formation, C—C bond formation, ester and thioester hydrolysis in the C—C hydrolase family. Chembiochem. 2008;9(1):71–6. 10.1002/cbic.200700428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ro HS, Hong HP, Kho BH, Kim S, Chung BH. Genome-wide cloning and characterization of microbial esterases. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;233(1):97–105. 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lan L, Murray TS, Kazmierczak BI, He C. Pseudomonas aeruginosa OspR is an oxidative stress sensing regulator that affects pigment production, antibiotic resistance and dissemination during infection. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75(1):76–91. Epub 2009/12/01. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06955.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gundogdu O, da Silva DT, Mohammad B, Elmi A, Mills DC, Wren BW, et al. The Campylobacter jejuni MarR-like transcriptional regulators RrpA and RrpB both influence bacterial responses to oxidative and aerobic stresses. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:724 Epub 2015/08/11. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sulavik MC, Gambino LF, Miller PF. The MarR repressor of the multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) operon in Escherichia coli: prototypic member of a family of bacterial regulatory proteins involved in sensing phenolic compounds. Mol Med. 1995;1(4):436–46. Epub 1995/05/01. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Sun X, Wu Y, Xie C, Zhang W, Wang D, et al. Oxidation-sensing regulator AbfR regulates oxidative stress responses, bacterial aggregation, and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(6):3739–52. Epub 2012/12/29. 10.1074/jbc.M112.426205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dubbs JM, Mongkolsuk S. Peroxide-sensing transcriptional regulators in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(20):5495–503. Epub 2012/07/17. 10.1128/JB.00304-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuangthong M, Helmann JD. The OhrR repressor senses organic hydroperoxides by reversible formation of a cysteine-sulfenic acid derivative. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(10):6690–5. 10.1073/pnas.102483199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mongkolsuk S, Panmanee W, Atichartpongkul S, Vattanaviboon P, Whangsuk W, Fuangthong M, et al. The repressor for an organic peroxide-inducible operon is uniquely regulated at multiple levels. Mol Microbiol. 2002;44(3):793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo ZQ, Clemente TE, Farrand SK. Construction of a derivative of Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 that does not mutate to tetracycline resistance. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2001;14(1):98–103. 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.1.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, et al. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D36–42. Epub 2012/11/30. 10.1093/nar/gks1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(21):2947–8. Epub 2007/09/12. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexeyev MF. The pKNOCK series of broad-host-range mobilizable suicide vectors for gene knockout and targeted DNA insertion into the chromosome of gram-negative bacteria. Biotechniques. 1999;26(5):824–6, 8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovach ME, Elzer PH, Hill DS, Robertson GT, Farris MA, Roop RM 2nd, et al. Four new derivatives of the broad-host-range cloning vector pBBR1MCS, carrying different antibiotic-resistance cassettes. Gene. 1995;166(1):175–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eiamphungporn W, Nakjarung K, Prapagdee B, Vattanaviboon P, Mongkolsuk S. Oxidant-inducible resistance to hydrogen peroxide killing in Agrobacterium tumefaciens requires the global peroxide sensor-regulator OxyR and KatA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;225(1):167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochsner UA, Vasil ML, Alsabbagh E, Parvatiyar K, Hassett DJ. Role of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxyR-recG operon in oxidative stress defense and DNA repair: OxyR-dependent regulation of katB-ankB, ahpB, and ahpC-ahpF. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(16):4533–44. Epub 2000/07/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ochsner UA, Hassett DJ, Vasil ML. Genetic and physiological characterization of ohr, encoding a protein involved in organic hydroperoxide resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(2):773–8. 10.1128/JB.183.2.773-778.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reiter B, Glieder A, Talker D, Schwab H. Cloning and characterization of EstC from Burkholderia gladioli, a novel-type esterase related to plant enzymes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;54(6):778–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Purified EstC was separated by 15% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with coomassie blue. Lane 1, lysate from culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETBlue-2 vector; Lane 2, lysate from uninduced culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETestR; lane 3, lysate from IPTG-induced culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETestR; lane 4 and 5, washing column fractions; lane 6, purified EstC.

(EPS)

Northern analysis of estC in A. tumefaciens NTL4 wild-type was performed using the [32P]-labeled estC probe and 20 μg of total RNA. UN, uninduced; CHP, induction with 1 mM CHP. The 23S rRNA used as the amount control is shown below the hybridized autoradiograph.

(EPS)

Purified EstR was separated by 15% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with coomassie blue. Lane 1, lysate from uninduced culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETestR; lane 2, lysate from IPTG-induced culture of BL21(DE3) harboring pETestR; lane 3, purified EstR.

(EPS)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.