Abstract

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represent a major health burden in industrialized countries. Although alcohol abuse and nutrition play a central role in disease pathogenesis, preclinical models support a contribution of the gut microbiota to ALD and NAFLD. This review describes changes in the intestinal microbiota compositions related to ALD and NAFLD. Findings from in vitro, animal, and human studies are used to explain how intestinal pathology contributes to disease progression. This review summarizes the effects of untargeted microbiome modifications using antibiotics and probiotics on liver disease in animals and humans. While both affect humoral inflammation, regression of advanced liver disease or mortality has not been demonstrated. This review further describes products secreted by Lactobacillus- and microbiota-derived metabolites, such as fatty acids and antioxidants, that could be used for precision medicine in the treatment of liver disease. A better understanding of host-microbial interactions is allowing discovery of novel therapeutic targets in the gut microbiota, enabling new treatment options that restore the intestinal ecosystem precisely and influence liver disease. The modulation options of the gut microbiota and precision medicine employing the gut microbiota presented in this review have excellent prospects to improve treatment of liver disease.

Keywords: alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, intestinal microbiome, precision medicine, probiotics

alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represent a major health burden in industrialized countries. ALD is caused by alcohol abuse, and NAFLD is closely related to obesity and the metabolic syndrome, although nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) has been reported in lean individuals (76, 105, 125, 160). Apart from poor diet, dysbiosis in the gut, i.e., a systematic pathological change in the microbiota, has been identified in ALD, NAFLD, and NASH (2, 85, 87, 122, 215, 223). This dysbiosis can lead to increased liver inflammation and fibrosis (30, 46, 121). Although diet and lifestyle changes remain cornerstones in the treatment of ALD and NAFLD, targeting dysbiosis might possibly complement therapy.

Gut bacteria and their derived metabolites (i.e., the gut metabolome) have moved from the focus of merely descriptive studies to possible targets in the treatment of diseases. Untargeted modification of the intestinal microbiota by antibiotics, prebiotics, and probiotics was the first attempt to influence dysbiosis and, thereby, disease outcomes. However, recent studies suggest that specific bacterial strains or their metabolites may be key targets in disease, prompting a more targeted approach and suggesting that the potential of whole-community modifications may be limited. Once modifiable key molecules, microbes, or pathways have been identified, they can be precisely targeted, with an overall goal to restore microbial eubiosis and intestinal homeostasis. This review describes microbiome changes and intestinal and hepatic pathobiology related to bacteria and discusses untargeted attempts (i.e., antibiotics and probiotics) undertaken to restore the healthy microbial community in both rodents and humans in ALD and NAFLD/NASH. Although a large body of literature on the interrelation of the microbiome and obesity/diabetes exists, this review summarizes data related to NAFLD/NASH. Finally, data on microbiota-derived molecules that could be utilized as therapeutic target and source for precision medicine to ameliorate liver disease are presented.

MICROBIOME CHANGES RELATED TO LIVER DISEASE

The term gut-liver axis, introduced in 1987 to link dietary antigens and liver cirrhosis, now comprises intestinal bacteria, the intestinal barrier, mucosal immunity, liver exposure to translocated bacterial pathogens, and resulting diseases (205). Excessive ethanol consumption and diets rich in saturated fat and cholesterol are associated with dysbiosis, i.e., changes in the intestinal microbiome that are associated with disease (2, 87). Poor nutrition and/or dysbiosis can further damage the intestinal epithelium, increase intestinal permeability, and expose the liver to harmful bacterial products. With the recent rise in 16S sequencing studies to investigate dysbiosis in-depth, microbiome studies have dramatically increased. Despite extensive data, it remains challenging to identify a core disease-related intestinal microbiome, because of great variations in study design, sequencing methods, and analysis tools/data presentation. However, as with other conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and obesity, it is likely that differences in cohorts and technical methods outweigh the effects of disease per se in published studies (127, 208). Consequently, method standardization is an important goal in identifying a core microbiota associated with each disease or consistent differences between cases and controls (9a).

In the following, this review summarizes current knowledge on endotoxemia and the generalizable microbiome changes associated with ALD and NAFLD.

Bacterial Endotoxemia in ALD and NAFLD

It has long been recognized that acute and chronic alcohol consumption increase gastrointestinal permeability (26, 103, 164). This likely facilitates the translocation of bacterial endotoxins, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), that originate from the cell wall of gram-negative bacteria. Elevated levels of endotoxins can be found in individuals who engage in acute binge alcohol consumption and in patients with any stage of ALD, such as steatosis, alcoholic hepatitis, and cirrhosis (14, 27). Cirrhotic patients with endotoxemia have higher 12- to 18-mo mortality (17, 74).

Patients with NAFLD have higher IgG antibody titers against commensal gut bacteria (Escherichia coli HA116, Bacteroides fragilis, Bifidobacterium thermophilium, and Klebsiella oxytoca) (15). Increased intestinal permeability is five times more likely in patients with NAFLD than healthy controls. This “risk” increases to >30 times in patients with NASH (128). Elevated intestinal permeability is associated with higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome and increased liver steatosis (79, 139). In the only prospective study relating permeability to liver pathology, increased levels of LPS-binding protein were found in subjects who developed NAFLD compared with those without NAFLD, whereas endotoxin levels were not elevated (217). Cross-sectional studies showed higher LPS-binding protein levels in patients with NASH than patients with simple steatosis (167, 177). In adolescents, studies investigating associations between endotoxin levels and liver phenotypes showed inconsistent results (8, 227). However, these studies reported no detailed dietary information. Diet is important, because fatty diet and fructose, consumed mainly in beverages that contain high-fructose corn syrup, drive endotoxemia and hepatic steatosis (22, 65, 152). Endotoxin levels were higher in adolescents with NAFLD after fructose consumption than after consumption of glucose-containing beverages and were also higher than in obese controls without NAFLD (100). Fructose-feeding studies in mice relate endotoxemia (and hepatic steatosis) to a serotonin-mediated downregulation of the intestinal tight junction protein occludin (89). Treatment with nonabsorbable antibiotics prevented endotoxemia in these mice, suggesting a mechanism of action of gram-negative bacteria (22).

Changes in the Microbiome

Gram-negative bacteria include the phyla Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria, both of which are common in the gut. Proteobacteria, which include E. coli, as well as other possibly pathogenic bacteria, such as Yersinia, Salmonella, and Campylobacter, are especially associated with inflammation (182).

Alcoholic liver disease.

Differences in the gut microbiome have been identified after alcohol consumption/feeding relative to controls (32, 45, 222). Stool samples of alcoholics with liver cirrhosis contain more Enterobactericeae (a family within the phylum Proteobacteria) than those of alcoholics without cirrhosis (46, 196). While the increase in Proteobacteria seems to be consistent across studies in cirrhotic patients and in cases of alcohol consumption/feeding, the increase in Bacteroidetes is not consistent. Another consistent finding is the decrease in Lactobacillus spp. in cases of alcohol consumption/feeding (32, 46, 196, 222). Lactobacilli have many beneficial functions in the gut. They produce antibiotics, or bacteriocins, that inhibit pathogens within the Enterobacteriacae, such as Salmonella or Shigella, and also have a peroxidase system that acts against other bacteria (69). Lactobacilli also adhere to intestinal cells, forming a protective layer against pathogenic and potential invasive bacteria (24, 35). The fermentation products of lactobacilli, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as lactic acid, propionic acid, or butyric acid, further contribute to intestinal epithelial integrity by providing nutrition to the epithelial cells (154). (The beneficial effects of butyrate, the conjugate base of butyric acid, are reviewed in more detail in Fatty acids.) Intestinal bacterial overgrowth, i.e., the increase in bacteria to >105 per milliliter in the small intestine, has also been found in precirrhotic stages and cirrhosis and has been linked to hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhotic patients with prolonged orocecal transit time (81). It is not known whether overgrowth is a result of decreased lactobacilli and their bactericidal properties or if lactobacilli are outnumbered by overgrowth of other bacteria. However, the presence of intestinal bacteria per se is protective, because germ-free mice exhibit more liver disease after acute binge alcohol consumption than conventionally raised mice. This effect is mediated by enhanced hepatic metabolism of alcohol in germ-free animals and, therefore, higher levels of toxic ethanol metabolites in the liver (43).

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Levels of gram-negative Bacteroides, a genus within the phylum Bacteroidetes and a possible source of endotoxin, are increased in NASH compared with NAFLD patients (30). The phylum Bacteroidetes, but not the genus Bacteroides, was also elevated in children with NASH (232). While differences in Bacteroidetes appear to be most consistent between studies, some other human studies found Bacteroidetes to be decreased (143, 157). However, findings in phyla such as Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and their constituent genera differ even more between studies (215). In contrast to ALD, lactobacilli may be increased in high-fat diet consumption, and this increase is associated with increased liver steatosis in mice and humans with NAFLD (compared with normal-weight, healthy controls) (97, 157, 230). An associated increase in Lactobacillus fermentation products suggests that food effects might override the beneficial effect on intestinal wall integrity in the host.

The microbiota may lead to fatty liver disease through interaction with host nutrient metabolism. This becomes especially clear from studies with germ-free mice. Germ-free mice have less liver steatosis and do not develop obesity when fed a Western-style diet (10, 11). This is most likely related to the ability of gut microbiota to cleave polysaccharides that are otherwise indigestible and not accessible to the host (221). Decreased liver steatosis in germ-free mice is, in addition, mediated by alterations in bacterial bile acid deconjugation in the intestine. Bile acid signaling through intestinal farnesoid X receptor (FXR) promotes NAFLD (96). In germ-free mice, FXR signaling is impaired by the increase in tauro-conjugated β-muricholic acid in the intestinal lumen. This conjugated bile acid acts as a FXR antagonist (171). Decreased body weight in germ-free mice might also be explained by higher levels of angiopoietin-like protein 4, also known as fasting-induced adipose factor in intestinal epithelial cells (10). Fasting-induced adipose factor impairs fat storage in adipocytes, muscle, and heart cells by inhibiting the lipoprotein lipase (102). A third explanation for why germ-free mice exhibit less liver steatosis is the higher amount of choline available to the germ-free host. In humans, members of the phyla Firmicutes and Proteobacteria (specifically, Anaerococcus hydrogenalis, Clostridium asparagiforme, Clostridium hathewayi, Clostridium sporogenes, Escherichia fergusonii, Proteus penneri, Providencia rettgeri, and Edwardsiella tarda) can metabolize choline to trimethylamine (6, 165). High metabolic rates lead to choline deficiency in the host, which results in liver steatosis, because the liver cannot secrete very-low-density lipoprotein without the membrane component phosphatidylcholine (60, 200). Trimethylamine, which also arises from bacterial metabolism of l-carnitine, can be metabolized by the host liver, mainly by flavin monooxygenase-3 to trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) (21, 107). TMAO plasma levels are associated with the severity of NAFLD in humans (47). However, the majority of the literature establishes a connection between TMAO and cardiovascular disease risk (191).

Endotoxemia seems to be associated with disease severity in ALD and NAFLD. However, the distribution of certain bacterial phyla is different between both diseases, and the role of single bacteria or bacterial communities in disease is not well understood. Several recent reviews have summarized compositional changes in the intestinal microbiota in ALD and NAFLD in more detail (2, 85, 87, 122, 215, 223).

CONNECTING MICROBIOTA, INTESTINAL PATHOLOGY, AND LIVER DISEASE

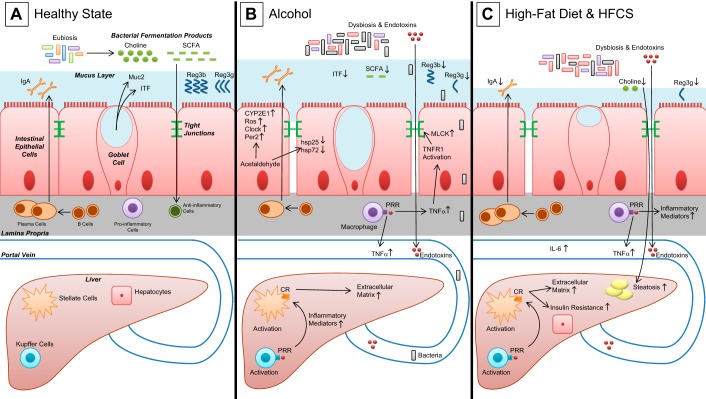

Intake of alcohol or a diet rich in saturated fatty acids, cholesterol, and fructose impairs the intestinal barrier by weakening the mucus-associated defense, impairing tight junction function and causing intestinal inflammation with subsequent translocation of bacterial pathogens into the bloodstream and to the liver (Fig. 1). Bacterial product-mediated inflammation is closely related to activation of the innate immune system via Toll-like receptors (TLRs). TLRs recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (138). TLR-2 may be activated by various membrane components of gram-positive bacteria. The lipid A portion of LPS binds to TLR-4, which forms a complex with CD14 on innate immune cells. TLR-5 may be activated by flagellin, and bacterial DNA activates TLR-9 (138, 140). Upon activation of TLR on macrophages, proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα, are released.

Fig. 1.

Gut homeostasis and liver disease. A: healthy state, characterized by eubiosis and gut microbiome-derived fermentation products, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) or choline. Luminal side of intestinal cells is protected by a mucus layer that contains various mucus-stabilizing proteins [mucin-2 (Muc2) and intestinal trefoil factor (ITF)] and defensive proteins (IgA). Anti-inflammatory immune cells are fortified by bacterial fermentation products. B: induction of dysbiosis, disruption of intestinal tight junctions, endotoxemia, and migration of bacteria in alcohol feeding/consumption lead to activation of hepatic Kupffer cells with subsequent stellate cell activation and increase in extracellular matrix. C: induction of dysbiosis and disruption of intestinal tight junctions in high-fat diet. Hepatic inflammation is linked to insulin resistance. CR, cytokine receptor; CYP2E1, cytochrome P-450 isoform 2E1; HFCS, high-fructose corn syrup; hsp25 and hsp72, heat shock protein 25 and 72; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; PRR, pattern recognition receptor; Reg3b and Reg3g, regenerating islet-derived protein 3β and 3γ; TNFR1, TNF receptor 1.

ALD and General Mechanisms in Liver Disease

Role of the mucus layer.

A mucus layer that contains defensive proteins protects the luminal side of intestinal cells against pathogens and keeps commensal bacteria at a distance from host epithelial cells. The mucus-stabilizing protein intestinal trefoil factor (ITF) is decreased in alcohol-fed mice (210). The most abundant secreted mucin is mucin-2 (Muc2). Muc2 deficiency was associated with increased colitis and colon cancer in a genetically susceptible host (198, 202). In ethanol-fed mice, however, Muc2 deficiency is protective (84). This is explained by compensatory increases in antimicrobial lectins, such as regenerating islet-derived protein 3β (Reg3b) and Reg3γ (Reg3g), and increases in other mucin proteins. Indeed, Reg3b and Reg3g deficiency increases bacterial translocation and liver injury in mice (Fig. 1B) (209). Germ-free mice do not express Reg3g, suggesting a role of lectins in the defense of bacterial translocation, in contrast to Muc2 and ITF, which are equally expressed in germ-free and conventional mice (19, 23, 40). Studies with mice further showed reduced intestinal immunoglobulin A (IgA) plasma cells with alcohol feeding (141, 210). This might contribute to a weakened mucosal defense.

Data from intestinal cell cultures.

Mechanisms of intestinal epithelial dysfunction following ethanol exposure have been further investigated using Caco-2 cells. Acetaldehyde, the first product of ethanol metabolism, lowers expression of tight and adherent junction proteins, such as occludin, zonula occludens protein-1 (ZO-1), claudin-1, and β-catenin (158). Ethanol exposure increases generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by the cytochrome P-450 isoform 2E1 (CYP2E1) and expression of Clock and Per2 proteins, all of which increase permeability in Caco-2 monolayers (72, 189). Clock and Per2 play a major role in circadian rhythmicity in the host. Circadian rhythms regulate gastrointestinal function, and disturbed rhythmicity facilitates intestinal damage and ALD (92, 108). Use of siRNA to impair CYP2E1 function restored permeability of Caco-2 monolayers, as well as Clock and Per2 (72). This suggests a close interrelation of ethanol metabolism, the circadian clock, and intestinal permeability.

Data from rodent studies on intestinal function.

Studies in rats show that ethanol induces expression of CYP2E1 along the entire intestinal tract (181). As in cell cultures, ROS levels are increased and can be reduced by impairment of CYP2E1 (1). Furthermore, ethanol feeding reduces the protective heat shock protein (Hsp) 25 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-2α in mice (172, 210). The resulting inflammation increases TLR-4 expression (116). Downstream activation of TNF-receptor type 1 (TNFR1) in enterocytes results in activation of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and other intracellular signaling mechanisms that disrupt tight junctions (44).

Alcohol disturbs the circadian rhythm in vivo by increasing Per2 in the duodenum and colon of rats (189). Via impaired occludin function in the colon, the disturbed circadian rhythm leads to increased intestinal permeability and ethanol-related liver damage (188). The circadian clock also regulates host-microbial interaction. The oscillation of mucus degradation pathways in microbial metabolomic pathways requires the cyclic host expression of Per2 (and Per1), i.e., a functioning host clock (194). Moreover, the circadian rhythm regulates the expression of TLRs (144). This suggests that dysregulated microbial mucus degradation and host immune function might add to epithelial damage.

Bacteria-associated liver damage.

After entering the portal vein blood, endotoxins reach the liver and mediate liver injury by activating Kupffer cells through TLRs and other pathogen recognition receptors (3). Ligand binding causes Kupffer cells to release the proinflammatory cytokines TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-18 and ROS. Release of TGFβ activates hepatic stellate cells, which increases extracellular matrix deposition, leading to hepatic fibrosis (173). Pathogen-associated molecular patterns might also damage hepatocytes directly (155).

Data from human studies.

Data from humans with ALD that confirm the above-mentioned mechanisms are scarce. Alcohol abuse increases intestinal TNFα levels, as well as activation of lamina propria monocytes and macrophages (44). In patients with alcohol- and obesity-related cirrhosis, these macrophages showed an activated phenotype [characterized by positivity for CD33, CD14, and triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (Trem)-1] that was related to increased levels of nitric oxide, IL-6, and IL-8 (59). A marker for gut vascular endothelial cell permeability was increased in patients with celiac disease and elevated transaminases (185). This suggests that, besides mucus, intestinal epithelial, and immune cells, the wall of blood vessels might control the systemic dissemination of bacteria or their products. The role of intestinal blood vessels in liver disease requires further investigation.

Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Role of the mucus layer.

As in ethanol feeding, mouse models show that Muc2 deficiency protects from high-fat diet-induced liver steatosis and obesity, accompanied by upregulation of intestinal Reg3g (86). In contrast, overfeeding of mice does not seem to reduce the number of intestinal plasma cells, while the luminal concentrations of IgA and Reg3g are reduced in mice fed a high-fat diet (Fig. 1C) (67, 68, 115, 207).

Data from rodent studies on intestinal epithelial function.

In mice with knockout of the junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A), intestinal mucosal inflammation, endotoxemia, and hepatic features of NASH occur (156). Intestinal deficiency of MyD88 (a downstream effector molecule of TLRs) reduces endotoxemia, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis (67). Whether this protection, similar to that in alcohol feeding, involves reduced activation of the downstream MLCK pathway and tight junction function remains to be determined. In contrast to defective defense in the host, the microbiota itself may lead to fatty liver disease through interaction with host metabolism, with transferability shown by fecal transplants (166). A high-fat diet disturbs circadian rhythms of the microbiota in mice, which was connected to overproduction of corticosterone in the ileum and a prediabetic state in the host (144, 228).

Bacteria-associated liver damage.

Some liver damage in NAFLD/NASH may follow the same pathological mechanisms as in ALD, because blood ethanol concentrations in obese mice are elevated even in the absence of ethanol intake (51). Treatment with neomycin reduces blood ethanol levels in mice, suggesting a contribution of gut bacteria to the production of ethanol (51).

Mice that lack CD14 are protected from high-fat diet- and LPS-mediated hepatic increase in TNFα and steatosis (37). Bacteria-induced liver inflammation in NAFLD involves LPS-mediated TLR-4 activation and release of TNFα in mice (80, 186). The subsequent activation of Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK), inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB kinase subunit β (IKKβ), and NF-κB increases energy storage and hepatic insulin resistance (34, 39). NF-κB activation was recently connected to increased hepatic gluconeogenesis, thus linking liver inflammation with peripheral insulin resistance (150). Conceivably, in mice treated with anti-TNFα antibodies, JNK and NF-κB activity is reduced and, thus, hepatic insulin resistance is reduced (117). Because antibodies have systemic effects, they might also decrease bacterial translocation by reducing TNFα-mediated intestinal inflammation. Studies that distinguish those effects are needed.

A high-fat diet also disturbs circadian rhythms in the liver, leading to overactivation of pathways involved in lipogenesis (61, 145). In addition, genetically modified animals that have a dysregulated circadian rhythm show features of NAFLD, and offspring of obese mice that develop NAFLD have a disturbed circadian rhythm with hypermethylation of the Per2 promoter (70, 142).

Data from human studies.

Patients with NAFLD have dysfunctional intestinal tight junctions and reduced levels of occludin and ZO-1 in the duodenum, as well as JAM-A in the colon (31, 97, 139, 156). Duodenal expression of TNFα and IL-6 is higher in NAFLD patients (97).

As in mouse studies, patients with NAFLD have elevated blood ethanol concentrations (206). The stool of these patients contains more Enterobacteriaceae, a family that produces ethanol as a result of mixed fermentation (233). The role of bacterial product-induced liver inflammation and damage in NAFLD is emphasized by increased hepatic expression of TLR-1, -2, -3, -4, and -5 and MyD88 compared with healthy controls (101). TLR-4 expression is elevated in NASH compared with NAFLD (177). Hepatic expression of TNFα and TNFR1 is higher in obese patients with advanced liver fibrosis than in patients with NAFLD or obese controls (53). In humans, treatment with pentoxifylline (an antagonist of TNFα action) reduced serum transaminases and histological features of NASH (169, 229). A disturbed circadian rhythm, as in shift workers, is related to prolonged elevation of transaminases in patients with NAFLD (120). Polymorphisms of the Clock gene have been identified in NAFLD patients (184).

TREATING INTESTINAL DYSBIOSIS WITH UNTARGETED AND PRECISION STRATEGIES

Endotoxemia has been connected to chronic liver disease since the 1970s and has been identified as a treatment target (104, 170). Gut bacteria are the source of endotoxins, so nonabsorbable antibiotics were used in the first attempts to engineer the microbiota, reduce endotoxemia, and improve liver disease (193). Because germ-free mice develop more liver injury after alcohol feeding and more fibrosis after administration of a liver toxin, the aim of the treatment can only be restoration of eubiosis, i.e., healthy microbiota, rather than complete bacterial decontamination (43, 136). Later, pre- and probiotics were used to improve liver disease by modulating dysbiosis. With the recent improved understanding of the gut microbiome, metabolome, and metagenome, more precise therapeutic opportunities (in contrast to approaches targeting dysbiosis in general) have unfolded in animal models.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics that act mainly within the intestinal lumen are especially thought to target dysbiosis without extraintestinal side effects. Traditionally, polymyxin B and neomycin have been studied in animal models of liver disease. In humans, paromomycin, norfloxacin, and rifaximin have also been studied (Table 1). For treatment of obesity and peripheral insulin resistance, numerous other antibiotics (ampicillin, vancomycin, bacitracin, norfloxacin, and metronidazole) have been investigated, but this is beyond the focus of this review (18, 38, 49, 93, 137, 146).

Table 1.

Human studies using poorly absorbable, enteral active antibiotics to treat dysbiosis and influence outcome of chronic liver disease or cirrhosis

| Liver Disease (diagnostic method) | Treatment | No. of Subjects | Trial Design | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALD (biopsy in 19 of 28 patients with cirrhosis and 21 of 21 patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis without cirrhosis; clinical and laboratory findings in 9 of 28 patients with cirrhosis) | Paromomycin sulfate (3× 1 g) or placebo daily for 21–28 days | 49 patients (25 antibiotics, 24 placebo) with cirrhosis (28 subjects) or acute alcoholic hepatitis without cirrhosis (21 subjects) | Double-blind RCT | Initial reduction of endotoxemia during treatment of patients with alcoholic hepatitis; no difference from placebo and no improvement in patients with cirrhosis No difference in improvement of transaminases, bilirubin, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, Quick test (INR) in either group | Bode et al. (28) |

| ALD (clinical and laboratory findings, ultrasound and/or CT and/or MRI) | Rifaximin (3× 400 mg) daily in perpetuity | 23 Patients with cirrhosis and improved hepatovenous pressure gradient after 28 days of Rifaximin pretreatment (=cases) vs. 46 patients with decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis (=controls) | Prospective case-control study | No long-term assessment of endotoxemia, laboratory findings or radiological liver appearance. After median (range) follow-up of 36 (5–60) mo in patients and 24 (4–60) mo in controls: •Improvement of 5-yr probability of survival (61% vs. 13.5%, P = 0.012) •Higher probability to remain free of hepatorenal syndrome (95.5% vs. 49%, P = 0.037) •Lower probability to develop spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (4.5% vs. 46%, P = 0.027) | Vlachogiannakos et al. (204) |

| Cause not specified (diagnostic method not specified) | Enteric-coated polymyxin B (3× 2 Mio U) daily, 5–32 days | 21 patients with liver cirrhosis | Open pilot study | Reduction of ammonemia and endotoxemia during treatment No improvement of plasma levels of bilirubin, albumin, and transaminases | Adachi et al. (4) |

| ALD, HBV, posthepatic cryptogenic (biopsy) | Paromomycin sulfate (4× 250 mg) or placebo daily for 28 days | 24 patients with liver cirrhosis and endotoxemia (13 antibiotics, 11 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Reduction of endotoxemia during treatment; improvement of creatinine clearance, but no improvement of liver function | Tarao et al. (193) |

| ALD, virus, AIH, cryptogenic (clinical or laboratory or radiological findings, eventually biopsy) | Norfloxacin (2× 400 mg) or placebo + propranolol daily for 60 days | 63 patients with cirrhosis and esophageal varices (31 antibiotics, 32 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Treatment reduced plasma TNFα Treatment had no effect on hepatovenous pressure gradient and plasma IL-6 | Gupta et al. (82) |

| NAFLD (biopsy) | Rifaximin (3× 400 mg) daily, 28 days | 15 patients with steatosis, 27 patients with NASH, no disease scores provided | Prospective, open-label, observational cohort study | NASH patients: reduction of endotoxin levels, serum IL-10, transaminases, LDL, and ferritin | Gangarapu et al. (75) |

| Steatosis patients: reduction of ALT and ferritin |

ALD, alcoholic liver disease; RCT, randomized-controlled trial; INR, international normalized ratio; HBV, hepatitis B virus; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Animal models in ALD.

In chronic alcohol feeding, polymyxin B and neomycin reduce endotoxemia and aspartate aminotransferase to control levels in rats (5). Hepatic inflammation also improves. A mouse model of chronic ALD that used the same antibiotics as a treatment intervention, rather than for prevention, restored alcohol-induced dysbiosis and reduced upregulated jejunal and monocytic TNFα expression (44). Intestinal occludin expression and permeability also improved. These effects were mediated by intestinal TNFR1 signaling and downstream signaling in enterocytes involving MLCK.

Animal models in NAFLD.

Human histological characteristics of NASH can be mimicked by fructose supplementation to a rodent diet that is otherwise high in cholesterol and saturated fatty acids (42). Polymyxin B and neomycin were tested in fructose-induced steatohepatitis in mice (22). This treatment reduced hepatic steatosis and portal endotoxin amounts to the levels of controls. In rats treated with the same antibiotics and fed a choline-deficient and amino acid-supplemented diet, liver fibrosis was reduced (58). In both animal models, the treatment benefits were attributed to decreased intestinal permeability and decreased LPS-induced hepatic TLR-4 expression (22, 58). However, serum transaminases did not reflect these improvements, suggesting a minor effect of treatment on liver inflammation.

Data from human trials.

Clinical trials in humans are summarized in Table 1. Consistent with data from the animal studies, endotoxemia and levels of related humoral inflammation markers such as TNFα were reduced in humans. Some studies found an improvement in liver disease-related complications, such as variceal bleeding and kidney function. However, this was not consistent across studies. A major drawback might be the short, typically 5- to 60-day, treatment periods. Compared with the time needed to develop liver disease, it is not surprising that all studies failed to demonstrate an improvement in liver function or morphology. In addition, no study investigated histological changes. On the other hand, antibiotic treatment in early life increases the risk for obesity (94). No epidemiological study has investigated the risk of antibiotic intake for the development of liver disease.

Probiotics

To target dysbiosis, probiotics typically lack side effects of antibiotic treatment, such as diarrhea, nausea, and severe complications such as Clostridium difficile diarrhea (see below). The beneficial effects of lactobacilli (reviewed in microbiome changes related to liver disease) make this bacterial family the most used probiotic supplement, and it is a component of many commercially available multispecies formulations such as VSL#3. Along with numerous Lactobacillus species (Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. paracasei, and L. bulgaricus), VSL#3 contains Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium infantis, and Bifidobacterium longum. In the rat gut, VSL#3 fortifies the intestinal barrier by increasing the amount of secreted mucus and upregulating Muc2 in the colon and occludin levels in the ileum (33).

Animal models in ALD.

In a rat model, alcohol feeding decreases intestinal lactobacilli and bifidobacteria, which can be increased by supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus spp. Gorbach-Goldin (LGG) and a synbiotic (containing L. acidophilus, L. bulgaricus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, B. longum, S. thermophilus, vitamins, and antioxidants), respectively (32, 48).

This synbiotic, VSL#3, and LGG may restore small intestinal epithelial function and permeability by increasing levels of occludin, claudin-1, ZO-1, ITF, VEGF, and HIF-2α or density of intestinal epithelial cell microvilli in rats or mice (32, 41, 71, 149, 210). LGG can also reduce ileal levels of ROS in mice (210).

Endotoxemia and plasma levels of TNFα in rats and mice can be reduced using VSL#3, LGG, and a combination of L. rhamnosus R0011, L. acidophilus R0052, ginseng, and urushiol (oil from the lacquer tree, traditional medicine in Korea, with anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and antimicrobial effects) (32, 41, 48, 71, 91, 149, 210). All three treatments also reduce hepatic levels of TNFα and histopathological liver inflammation in rats and mice (16, 32, 41, 48, 71, 91, 149, 211). Treatment of mice with the synbiotic containing uroshiol also reduced hepatic levels of TLR-4 (16, 91). LPS-induced hepatic TLR-5 upregulation can be reduced by LGG treatment in mice (211). Features of alcoholic liver injury in mice can even be reduced by administration of heat-inactivated Lactobacillus brevis SBC8803 (172). This suggests that live bacteria may not be required for some beneficial effects.

Animal models in NAFLD.

Some probiotics have shown efficiency in stabilization of the intestinal milieu in rodents fed a high-fat diet. The diet-induced increase in fecal Enterococcus was reduced with L. casei strain Shirota (151). Expression of tight junction proteins (occludin, ZO-1, and claudin-1) was increased by supplementation with L. rhamnosus, L. paracasei, and Bifidobacterium adolescentis in the colon, duodenum, and small intestine, respectively (159, 161, 163). Lactobacillus salivarius LI01 improved enterocyte architecture in the terminal ileum (129). L. paracasei and L. salivarius LI01 reduced intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation, respectively (129, 159).

Probiotics may also reduce liver inflammation in NAFLD rodent models. Hepatic generation of ROS was reduced by supplementation with L. plantarum NCU116 in rats fed a high-fat diet (114). In rats, B. longum and Clostridium butyricum MIYAIRI 588 also reduced hepatic steatosis and prevented liver fibrosis (64, 220). Clostridium even prevented carcinogenesis (64). In a mouse model, hepatic steatosis and fibrosis were reduced by L. casei strain Shirota and B. adolescentis (151, 161). Expression of various liver inflammation markers (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and TLR-4) was reduced by supplementation with VSL#3, L. rhamnosus, B. adolescentis, and B. animalis ssp. lactis 420 in mice (130, 159, 161, 163, 187). Increased hepatic TNFα expression following LPS injections in mice could be reduced by supplementation with Lactobacillus fermentum ZYL0401 (99). In rats, a synbiotic containing L. paracasei reduced expression of hepatic TNFα, IL-6, and TLR-4 (159).

Probiotics also influence hepatic insulin resistance. Even in ob/ob mice (which develop obesity from hyperphagia due to lack of leptin), VSL#3 treatment reduces hepatic markers for insulin resistance (NF-κB-binding activity and JNK expression) and decreases transaminases (117). In a rat model of high-fat diet-induced NAFLD, VSL#3, L. plantarum NCU116, B. adolescentis, C. butyricum MIYAIRI 588, and a synbiotic containing L. paracasei restore hepatic NF-κB, p65, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α, which enhances β-oxidation and prevents lipid storage (66, 114, 159, 161, 174). Obesity, NF-κB-binding activity, PPARα, and β-oxidation are also improved in mice after supplementation with VSL#3 and Lactobacillus johnsonii (130, 219). The preventive effect of VSL#3 for obesity in mice is mediated by hepatic CD1d tetramer-positive natural killer T cells, which can be restored by VSL#3 treatment (130). This effect seems to be caused by antigens of the lactobacilli, which stimulate natural killer T cells independent of TLR-4 (118).

L. acidophilus, a bacterium frequently added to probiotic dairy products, had no effect on hepatic steatosis or intestinal permeability in rats (220). This demonstrates that effects differ between bacterial species (131). In addition, when NASH was induced in mice by a choline-deficient diet, histopathological liver inflammation, liver levels of TNFα, and the degree of liver steatosis could not be reduced by supplementation with VSL#3 (201). This suggests that diet effects may override the possible benefit of probiotic bacteria.

In summary, supplementation with many different probiotics shows beneficial effects overall in animal models of alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver disease. However, the effects differ between bacterial species, and in all studies probiotics were applied to prevent, rather than treat, disease. Animal studies testing whether probiotics can reverse diet-induced liver disease are still lacking.

Data from human trials.

The safety of probiotics and their effect on gut microbiota and plasma endotoxin, as well as TNFα levels, in patients with cirrhosis have been proven in several studies (12, 13). Because they are inexpensive and well tolerated, probiotics are an appealing alternative for antibiotics to influence ALD or NAFLD. Consequently, more human studies have used probiotics than antibiotics to modify the microbiota in liver disease (Table 2).

Table 2.

Human studies using probiotics to treat dysbiosis and influence outcome of chronic liver disease or cirrhosis

| Liver Disease (diagnostic method) | Treatment | No. of Subjects | Trial Design | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALD (history of alcohol consumption, clinical and laboratory findings) | Bifidobacterium bifidum (9 × 107 CFU) and Lactobacillus plantarum 8PA3 (9 × 108 CFU) 1× daily, 5 days | 66 patients with alcohol consumption without signs of cirrhosis (34 standard therapy, 32 standard + probiotic), 24 controls | Open-label, randomized, prospective study | Patients drank heavily until 2 days prior to study entry Reduction of AST levels, but not ALT or γ-GT, with probiotics compared with standard therapy | Kirpich et al. (106) |

| Subgroup with biochemically defined alcoholic hepatitis had reduction only of ALT levels. | |||||

| Lower levels of stool bifidobacteria, bactobacilli, and enterococci in alcoholic subjects were restored to normal levels by probiotics | |||||

| ALD (biopsy and/or radiological findings) | Lactobacillus subtilis and Streptococcus faecium (3× 500 mg) or placebo daily, 7 days | 117 patients (60 probiotics, 57 placebo), 53% with cirrhosis (58% in probiotics and 47% in placebo group) | Double-blind RCT | Patients drank heavily until 2 days prior study entry No difference between groups in reduction of transaminases | Han et al. (83) |

| Treatment decreased serum TNFα levels | |||||

| Treatment stabilized LPS levels in cirrhosis patients (LPS increased with placebo) | |||||

| Treatment reduced gram-negative bacteria in stool culture | |||||

| ALD, NASH, HCV (biopsy) | Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. bifidus, L. rhamnosus, L. plantarum, L. salivarius, L. bulgaricus, L. lactis, L. casei, L. breve, various vitamins, and micronutrients (2× 2 capsules) daily, 60–90 days | 12 HCV (90 days treatment), 10 ALD (60 days treatment), 10 NASH (60 days treatment) | Open pilot study | During treatment, transaminases and plasma TNFα decreased in ALD and NASH | Loguercio et al. (123) |

| Treatment had no effect in HCV patients | |||||

| ALD, NAFLD, HCV (biopsy, ultrasound, laboratory findings) | VSL#3 (2× 2 sachets) daily, 90 days | 78 patients (22 NAFLD, 20 HCV hepatitis, 16 HCV cirrhosis, 20 alcoholic cirrhosis) | Open pilot study | Decrease in transaminases in all groups Improvement of serum albumin and bilirubin, as well as TNFα and IL-6, levels in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, who abstained from alcohol 6 mo prior to study entry | Loguercio et al. (124) |

| ALD, HCV, HBV, cryptogenic (diagnostic method not specified) | VSL#3 (2× 2 sachets) daily, 60 days | 8 patients with cirrhosis | Open pilot study | No effect on hepatovenous pressure gradient (primary outcome) | Tandon et al. (190) |

| Trend to reduced endotoxin levels, reduction of serum TNFα | |||||

| ALD, virus, AIH, cryptogenic (clinical or laboratory or radiological findings, eventually biopsy) | VSL#3 (1× 1 sachet) or placebo + propranolol daily, 60 days | 63 patients with cirrhosis and esophageal varices (31 probiotics, 32 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Probiotic treatment reduced hepatovenous pressure gradient and plasma TNFα | Gupta et al. (82) |

| No effect on plasma IL-6. | |||||

| ALD, HCV (biopsy or radiological findings) | VSL#3 (2× 2 sachets) or placebo daily, 60 days | 15 patients with cirrhosis, 11 with ALD, 4 with HCV (7 probiotics, 8 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Treatment had no effect on fecal microbiota, endotoxin levels, liver function, or hepatovenous pressure gradient (primary outcome) Treatment reduced plasma aldosterone but had no effect on plasma renin or blood pressure | Jayakumar et al. (95) |

| ALD, HCV, HBV, other (biopsy or ultrasound or clinical or laboratory findings) | VSL#3 (1× 1 sachet) or placebo daily, 180 days | 130 patients with cirrhosis and recovery from hepatic encephalopathy (66 probiotics, 64 placebo) | RCT | No difference in incidence of hepatic encephalopathy (primary end point), but more high-grade events with placebo that required hospitalization No difference in mortality Treatment reduced Child-Pugh and MELD score and plasma TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 | Dhiman et al. (55) |

| ALD, HCV, HBV, cryptogenic (diagnostic method not specified) | Bifidobacterium bifidum, B. lactis, B. longum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, Streptococcus thermophiles, 5 × 109 viable cells 2× 1 capsule or placebo daily, 28 days | 50 patients with chronic liver disease (mean Child-Pugh-Score 5.5; 25 probiotics, 25 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Decrease in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth with treatment (primary outcome) | Kwak et al. (110) |

| No difference in intestinal permeability; however, degree of permeability was inversely correlated with number of lactobacilli in the stool | |||||

| NAFLD (biopsy) | Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophiles (5 × 106 CFU) as tablet or placebo daily, 90 days | 28 patients with NAFLD (14 probiotics, 14 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Treatment group showed an improvement of transaminases | Aller et al. (9) |

| NAFLD (ultrasound) | Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG (12 billion CFU) or placebo daily, 60 days | 20 children with fatty liver (10 probiotic, 10 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Treatment reduced ALT levels No change in sonographically determined liver steatosis or plasma TNFα | Vajro et al. (197) |

| NASH (biopsy) | Bifidobacterium longum and fructooligosaccharides (2.5 g) + vitamins or placebo daily + lifestyle modifications, 180 days | 66 patients (34 probiotics (mean NASH activity 9.4), 32 placebo (mean NASH activity 8.4) | Double-blind RCT | Treatment reduced hepatic steatosis and histological NASH activity (mean value probiotics 3.2; mean value placebo 4.1) | Malaguarnera et al. (132) |

| Treatment reduced serum AST, CRP, TNFα and endotoxin levels | |||||

| Equal reduction of serum ALT, hepatic infammation, and fibrosis with probiotic and placebo treatment | |||||

| NASH (biopsy, follow-up with proton-magnetic resonance spectroscopy) | Lactobacillus plantarum, L delbrueckii spp. bulgaricus, L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidum (2 million CFU) + prebiotics daily or usual care, 180 days | 20 patients (10 probiotics (median NAFLD activity score 4), 10 controls receiving only usual care (median NAFLD activity score 5) | Open-label randomized trial | Treatment reduced hepatic triglyceride content (measured by proton-magnetic resonance spectroscopy) and AST levels | Wong et al. (216) |

| No difference in liver stiffness (measured by elastography), ALT levels, BMI reduction, metabolic serum markers | |||||

| NAFLD (diagnostic method not specified) | Lactobacillus and Lactococcus (6 × 1010), propionic bacterium (3 × 1010), Bifidobacterium (1 × 1010), acetic bacterium (1 × 106), and antidiabetic therapy, 30 days | 72 patients (45 probiotics, 27 controls receiving only antidiabetic therapy) | Open-label trial | Patients with NAFLD and elevated transaminases showed reduction of IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, TNFα, IFNγ Subjects with normal transaminases only had decreased levels of TNFα | Mykhal'chyshyn et al. (147) (abstract) |

| NASH (biopsy and ultrasound, follow-up with ultrasound) | Lactobacillus acidophilus (1 × 108 CFU), L. casei (5 × 108 CFU), L. rhamnosus (7.5 × 107 CFU), L. bulgaricus (1.5 × 108 CFU), Bifidobacterium breve (5 × 107 CFU), B. longum (2.5 × 107 CFU), Streptococcus thermophilus (5 × 107 CFU), and fructooligosaccharides (350 mg 2× 2 tablets) or placebo daily + metformin (2× 500 mg) daily, 180 days | 63 patients (∼67% with grade 2 steatosis in ultrasound; 32 probiotics, 31 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Probiotic treatment reduced transaminases and sonographically graded liver steatosis (>90% of patients with steatosis grade 0 and 1 after probiotics vs. >80% of patients with steatosis grade 1 and 2 after placebo) Probiotic treatment resulted in higher reduction of BMI, serum triglycerides, and cholesterol | Shavakhi et al. (178) |

| NAFLD in children (laboratory and clinical findings, ultrasound and biopsy) | VSL#3 (1 sachet) or placebo daily, 120 days | 44 children (mean NASH activity score ∼5.5; 22 probiotics, 22 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Treatment increased probability of lower sonographically determined fatty liver scores Probiotic treated had higher BMI reduction | Alisi et al. (7) |

| No difference in improvement of transaminases, bilirubin, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, INR | |||||

| NAFLD (ultrasound) | L. casei (3 × 109 CFU/g), L. acidophilus (3 × 1010 CFU/g), L. rhamnosus (7 × 109 CFU/g), L. bulgaricus (5 × 108 CFU), Bifidobacterium breve (2 × 1010 CFU), B. longum (109 CFU), and Streptococcus thermophilus (3 × 108 CFU), 1 capsule or placebo daily, 60 days | 42 patients (21 probiotics, 21 placebo) | Double-blind RCT | Treatment reduced serum IL-6 Treatment had no effect on serum TNFα | Sepideh et al. (175) |

| NAFLD (ultrasound) | Probiotic yogurt (containing Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus) enriched with Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 (4.42 × 106 CFU/g) and L. acidophilus La5 (3.85 106 CFU/g) or unenriched yogurt (300 g) daily, 60 days | 72 patients (mean steatosis grade 1.5; 36 probiotics, 36 unenriched yogurt-consuming controls) | Double-blind RCT | Reduction of transaminases and serum LDL | Nabavi et al. (148) |

| No change in hepatic steatosis |

HCV, hepatitis C, virus; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; γ-GT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; CFU, colony-forming units; CRP, C-reactive protein; BMI, body mass index.

In ALD, probiotics in most studies decreased levels of transaminases and serum inflammation markers, such as TNFα. This is surprising, given the relatively short (<60-day) treatment period. Consequently, effects on endotoxin levels were inconsistent, and effects on mortality or liver histology were not present or not reported. Positive effects on long-term disease outcome are attributed to beneficial effects on liver disease-related complications, such as reduced encephalopathy or reduced hepatovenous pressure gradient (55, 82, 124). However, other studies did not confirm these effects (95, 190).

In NAFLD, most of the investigated regimens reduced transaminases, serum IL-6, and TNFα. Where liver morphology was assessed (mainly by ultrasound or MRI), steatosis was reduced by probiotic treatment. One study that used biopsies to monitor supplementation with B. longum plus antioxidants also showed a reduction of steatosis, but fibrosis levels were unchanged (132). Similar results were obtained using different Lactobacillus species and transient elastography (216). Of the nine studies presented in Table 2 focusing on NAFLD alone, only three tested the probiotics for a reasonable amount of time (6 mo). Future studies are required to assess whether a longer treatment period results in reduction of liver fibrosis.

Taken together, probiotics seem to reduce serum inflammation and hepatic steatosis in patients with NAFLD. However, evidence of effects on liver fibrosis or reduction of mortality in ALD is weak, and treatment response can hardly be monitored by changes in serum levels of transaminases or endotoxin. Sufficiently powered long-term clinical trials with probiotics are required to assess their effect on progression of liver disease and regression of liver fibrosis. There is a need for more standardization of probiotics in terms of their preparation and for definition of better clinical end points for clinical trials.

Precision Approach

Microbiome research is in its infancy, but a more comprehensive picture of the interaction between gut microbial communities and host is evolving. The broad spectrum of targets of antibiotics and probiotics prevents referral of treatment effects to a specific change in the microbiome or metabolome. Identification of beneficial bacteria and/or their products might lead to a precision medicine approach that treats intestinal permeability, endotoxemia, and liver disease. This would also overcome possible adverse effects or contraindications for patients with certain comorbidities (111, 162).

One example of a microbiome-guided therapy moving into precision medicine is the treatment of antibiotic-associated C. difficile diarrhea. Growth of the pathogen is facilitated by intestinal dysbiosis, as the disease mostly occurs in patients who received antibiotics for other reasons. Pathogenic clostridia release toxin A and (more commonly) toxin B, which destroy the epithelial cells in the colon (50). The resulting diarrhea may be life-threatening and bears high costs for the health sector, because it has high recurrence rates, despite treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics (113). Fecal microbiota transplantation, i.e., infusion of a healthy microbiome to replace the dysbiotic microbiota in the diseased gut, is more successful than antibiotic treatment (199) because of an overall shift of the microbial community from a dysbiotic to a eubiotic state (213). A more precise approach, colonization of the intestine with the nonpathogenic C. difficile strain M3, reduced diarrhea recurrence within 6 wk following antibiotic treatment compared with placebo (78). However, this remains a fairly untargeted approach. Recently, more precise strategies targeting the diarrhea-causing toxins directly have been introduced. Monoclonal antibodies, administered together with antibiotics, lowered the recurrence rate of the diarrhea within 3 mo of treatment (126). The small molecule ebselen inhibits the cysteine protease domain on toxins A and B and attenuates the damage of toxin-carrying clostridia in a mouse model (20).

A second, liver-related example of precision medicine is treatment of hyperammonemia in end-stage liver disease with urease-depleted bacteria to avoid ammonium-induced encephalopathy (179). Earlier treatment consisted of lactulose, a laxative that reduces ammonia concentrations by fecal excretion through acidification of intestinal contents and conversion of ammonia to a protonated form (NH4+) that is not reabsorbed. Antibiotics can be used to remove ammonia-producing bacteria from the intestine and treat hepatic encephalopathy. Rifaximin is recommended today to modify the gut microbiota and reduce ammonia-producing bacteria (63).

Precision medicine approaches that could be used to treat alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are reviewed and discussed below.

Supernatant of LGG cultures.

Experimental models of ALD and patients with alcohol dependence consistently show a decrease in intestinal Lactobacillus spp. (32, 46, 196, 222). Restoration of depleted lactobacilli offers a great opportunity for a precision approach. Instead of supplementation with live lactobacilli, attempts have been made to identify Lactobacillus-specific products and metabolites. The supernatant of LGG cultures reduces liver inflammation and hepatic levels of TNFα and TLR-4 in mice with ALD (212, 231). This is related to decreased intestinal permeability and increased expression of intestinal tight junction proteins, as well as expression of HIF-2α and HIF-regulated transcription of ITF, the cathelin-related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP), and P-glycoprotein (P-gp, which mediates the efflux of drugs and bacterial toxins from the intestinal mucosa into the lumen) (210, 212). In addition, LGG supernatant decreases levels of microRNA 122a (miR122a, a regulator of intestinal TNFα-mediated occludin expression) in mouse small intestine and activates the antiapoptotic MAP kinase Akt in colon cell cultures (192, 225, 226, 231).

Several active proteins, a protein smaller than 10 kDa and two larger proteins, p75 and p40, were identified in the LGG supernatant (192, 224). p75 and p40 have also been identified in L. casei 334 and L. casei 339, but not L. acidophilus, supernatants (224). p75 and p40 activate Akt. Both proteins inhibit TNF- and H2O2-induced enterocyte apoptosis and stabilize occludin, ZO-1, E-cadherin, and β-catenin at the intercellular junctions of primary mouse colon cells and Caco-2, T84, and HT29 cells (176, 224). The smaller protein increases transcription of Hsp25 and Hsp72 in young adult mouse colon cells, thus preserving intestinal barrier function (192). Precision manipulation by supplementation with LGG products might benefit the host.

Fatty acids.

Metabolomic studies demonstrate that luminal concentrations of butyrate and propionate decrease in the gastrointestinal tract following chronic alcohol feeding in rats (218). This offers an opportunity to replenish lower levels of intestinal SCFAs. The most extensively studied SCFA is butyrate. Among others, the major butyrate-producing strains belong to the phyla Firmicutes and Actinobacteria (203). The probiotics Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are members of the phyla Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, respectively, and both showed positive effects on intestinal epithelial function and liver disease. In humans, oral treatment with enteric-coated butyrate improves inflammation in mildly to moderately active Crohn's disease (56). Butyrate improves intestinal barrier function. Treatment of colon cell cultures with butyrate increases Muc2 expression and reduces paracellular permeability (88, 133). The colonization of germ-free mice with the butyrate producer Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens restored metabolic processes in mouse colonocytes (57). Feeding butyrylated high-amylose maize starches increased the number of colonic regulatory T cells in mice (73). In addition, oral sodium butyrate supplementation not only prevented, but also improved, obesity and insulin resistance in high-fat diet-fed mice (54, 77, 214). Moreover, the treatment improved hepatic β-oxidation (54, 77, 214). The effects of SCFAs occur after absorption, merely from the colonic lumen, by diffusion, anion exchange, or active transport by, e.g., monocarboxylate transporter isoform 1 (25, 195). The probiotic L. plantarum counteracts TNFα- and enteropathogenic E. coli-induced downregulation of monocarboxylate transporter isoform 1 expression (29, 109).

The effect of ethanol on this transport mechanism has not been investigated. However, the dysbiosis in chronic alcohol feeding leads to a decrease in lactobacilli and a relative increase in E. coli and an increase in TNFα signaling in the small intestine of rodents (44, 232). In addition, butyrate concentrations are lower in the cecum, colon, and rectum of chronically alcohol-fed rats (218). This might be connected to a reduction of butyrate-producing Firmicutes that was found in the cecum of mice with ALD (222). However, in alcohol-dependent humans, the relative abundance of Firmicutes is increased (46). Oral supplementation with the prodrug glyceryl tributyrate increases alcohol-induced downregulation of tight junction proteins in the proximal colon of mice (52) but does not affect hepatic triglyceride levels after chronic alcohol feeding. Taken together, alcohol might decrease absorption and luminal concentrations of butyrate, but direct evidence is missing. Reduced butyrate concentrations might contribute to the alcohol-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction. In the studies presented here, butyrate alone was added to rodent chow. Because butyrate is mainly absorbed from the colonic lumen, it is doubtful if this supplementation reached the colon. Effects on liver pathology should be assessed using enteric-coated butyrate or butyrate-producing bacteria. Studies in humans are required to clarify whether screening for low intestinal levels of butyrate or butyrate-producing bacteria might provide a tailored and personalized approach to treatment of ALD.

Recent studies using butyrate in models of NAFLD suggest a protective effect. In hepatocyte cultures, sodium butyrate supplementation induces expression of cell signals (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and its targets HO-1, NQO1, and thioredoxin) that trigger induction of oxidative stress-related cytoprotective genes. Butyrate also improves cell signals that are hampered by insulin resistance (the 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase/sirtuin 1/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 pathway) (64). In mice and rats fed a Western-style diet, hepatic inflammation and steatosis were reduced by oral supplementation with sodium butyrate (98, 135). Hepatic expression of TLRs, PPARα, and PPARγ was also reduced in rats, but not in mice. The probiotic C. butyricum MIYAIRI 588 is a producer of butyrate. This probiotic reduced hepatic steatosis, fibrosis, and carcinogenesis and increased hepatic levels of PPARα in rats (64, 174). The role of butyrate and other SCFAs in reducing obesity and insulin resistance in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle has been studied extensively (36).

A second precision microbiome approach involves bacteria-derived saturated medium- and long-chain fatty acids. These were shown to maintain the gut barrier and reduce liver injury in alcohol-fed mice (45). A metabolomic approach revealed a relative deficiency in luminal saturated long-chain fatty acids after chronic ethanol administration in mice. Targeted supplementation with saturated long-chain fatty acids restored this deficiency, supported growth of LGG, and was beneficial for ethanol-induced liver disease in mice (45). In obese mice, the trans-10,cis-12-conjugated linoleic acid-producing L. plantarum PL62 reduces body fat mass (112, 153). These reports suggest how precision approaches can restore intestinal eubiosis and homeostasis and can be beneficial for a distant organ such as the liver.

Antioxidants.

Oxidative stress drives hepatic injury in alcoholic and nonalcoholic liver disease (119). The antioxidant vitamin E reduces hepatic steatosis and inflammation (but not fibrosis) in patients with NASH (168). The bacteria-derived antioxidant pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) reduced liver injury by counteracting the oxidative stress caused by acetaldehyde (183). PQQ is secreted by gram-negative bacteria and reduces blood levels of acetaldehyde in a rat model of alcohol feeding (90, 134). Oral supplementation with E. coli Nissle 1917 transfected with a PQQ-producing plasmid in a rat model of ALD led to a reduction of hepatic oxidative stress by restoring levels of glutathione, superoxide dismutase, and catalase (183). Furthermore, levels of fecal SCFAs, i.e., acetate, propionate, and butyrate, were increased in treated animals. This suggests that use of a microbiome approach and genetically engineered bacteria to precisely target acetaldehyde as one of the main mediators for ALD might be sufficient to decrease ALD.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Targeting alcohol consumption and overnutrition remains the most important treatment for ALD and NAFLD. More knowledge about the gut-liver axis is required to impede or even reverse ALD or NAFLD by targeting the gut microbiome. However, given the success of tailored approaches in modulating the gut microbiome in animal studies, characterizing the microbiome and metabolome in patients might become a routine diagnostic test to stratify patients for tailored microbiome treatment approaches. Therapies that change the entire gut microbiome by use of antibiotics, probiotics, or fecal transplants will be replaced by therapies involving more precise microbial communities, engineered individual bacterial strains, or drugs that inhibit or mimic specific bacterial enzymes. The introduction of urease-producing bacteria to prevent hepatic encephalopathy and the targeted inhibition of C. difficile's virulence factors are examples of the potential of precision microbiome therapies. Future therapeutics might even employ engineered bacteria (or carefully selected naturally occurring bacteria from the human gut) as “bio-power plants” that produce anti-inflammatory peptides, such as IL-10 or beneficial antioxidants (180, 183).

GRANTS

S. Bluemel was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation Grant P2SKP3_158649. This work was also supported in part by National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01 AA-020703 and U01 AA-021856 and Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service Award I01BX002213.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.B. drafted the manuscript; S.B. and B.W. prepared the figure; S.B., R.K., and B.S. edited and revised the manuscript; S.B., B.W., R.K., and B.S. approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelmegeed MA, Banerjee A, Jang S, Yoo SH, Yun JW, Gonzalez FJ, Keshavarzian A, Song BJ. CYP2E1 potentiates binge alcohol-induced gut leakiness, steatohepatitis, and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med 65: 1238–1245, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdou RM, Zhu L, Baker RD, Baker SS. Gut microbiota of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis Sci 61: 1268–1281, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adachi Y, Bradford BU, Gao W, Bojes HK, Thurman RG. Inactivation of Kupffer cells prevents early alcohol-induced liver injury. Hepatology 20: 453–460, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adachi Y, Enomoto M, Adachi M, Suwa M, Nagamine Y, Nanno T, Hashimoto T, Inoue H, Yamamoto T. Enteric coated polymyxin B in the treatment of hyperammonemia and endotoxemia in liver cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Jpn 17: 550–557, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adachi Y, Moore LE, Bradford BU, Gao W, Thurman RG. Antibiotics prevent liver injury in rats following long-term exposure to ethanol. Gastroenterology 108: 218–224, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.al-Waiz M, Mikov M, Mitchell SC, Smith RL. The exogenous origin of trimethylamine in the mouse. Metab Clin Exp 41: 135–136, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alisi A, Bedogni G, Baviera G, Giorgio V, Porro E, Paris C, Giammaria P, Reali L, Anania F, Nobili V. Randomised clinical trial: the beneficial effects of VSL#3 in obese children with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 39: 1276–1285, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alisi A, Manco M, Devito R, Piemonte F, Nobili V. Endotoxin and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 serum levels associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 50: 645–649, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aller R, De Luis DA, Izaola O, Conde R, Gonzalez Sagrado M, Primo D, De La Fuente B, Gonzalez J. Effect of a probiotic on liver aminotransferases in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a double blind randomized clinical trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 15: 1090–1095, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Anonymous. Raising standards in microbiome research. Nat Microbiol 1: 16112, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Backhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 15718–15723, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Backhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 979–984, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, Sanyal AJ, Puri P, Sterling RK, Luketic V, Stravitz RT, Siddiqui MS, Fuchs M, Thacker LR, Wade JB, Daita K, Sistrun S, White MB, Noble NA, Thorpe C, Kakiyama G, Pandak WM, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. Randomised clinical trial: Lactobacillus GG modulates gut microbiome, metabolome and endotoxemia in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 39: 1113–1125, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Christensen KM, Hafeezullah M, Varma RR, Franco J, Pleuss JA, Krakower G, Hoffmann RG, Binion DG. Probiotic yogurt for the treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Gastroenterol 103: 1707–1715, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bala S, Marcos M, Gattu A, Catalano D, Szabo G. Acute binge drinking increases serum endotoxin and bacterial DNA levels in healthy individuals. PLos One 9: e96864, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balmer ML, Slack E, de Gottardi A, Lawson MA, Hapfelmeier S, Miele L, Grieco A, Van Vlierberghe H, Fahrner R, Patuto N, Bernsmeier C, Ronchi F, Wyss M, Stroka D, Dickgreber N, Heim MH, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ. The liver may act as a firewall mediating mutualism between the host and its gut commensal microbiota. Sci Transl Med 6: 237ra266, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bang CS, Hong SH, Suk KT, Kim JB, Han SH, Sung H, Kim EJ, Kim MJ, Kim MY, Baik SK, Kim DJ. Effects of Korean red ginseng (Panax ginseng), urushiol (Rhus vernicifera Stokes), and probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus R0011 and Lactobacillus acidophilus R0052) on the gut-liver axis of alcoholic liver disease. J Ginseng Res 38: 167–172, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer TM, Schwacha H, Steinbruckner B, Brinkmann FE, Ditzen AK, Aponte JJ, Pelz K, Berger D, Kist M, Blum HE. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in human cirrhosis is associated with systemic endotoxemia. Am J Gastroenterol 97: 2364–2370, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bech-Nielsen GV, Hansen CH, Hufeldt MR, Nielsen DS, Aasted B, Vogensen FK, Midtvedt T, Hansen AK. Manipulation of the gut microbiota in C57BL/6 mice changes glucose tolerance without affecting weight development and gut mucosal immunity. Res Vet Sci 92: 501–508, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker S, Oelschlaeger TA, Wullaert A, Vlantis K, Pasparakis M, Wehkamp J, Stange EF, Gersemann M. Bacteria regulate intestinal epithelial cell differentiation factors both in vitro and in vivo. PLos One 8: e55620, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bender KO, Garland M, Ferreyra JA, Hryckowian AJ, Child MA, Puri AW, Solow-Cordero DE, Higginbottom SK, Segal E, Banaei N, Shen A, Sonnenburg JL, Bogyo M. A small-molecule antivirulence agent for treating Clostridium difficile infection. Sci Transl Med 7: 306ra148, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett BJ, de Aguiar Vallim TQ, Wang Z, Shih DM, Meng Y, Gregory J, Allayee H, Lee R, Graham M, Crooke R, Edwards PA, Hazen SL, Lusis AJ. Trimethylamine-N-oxide, a metabolite associated with atherosclerosis, exhibits complex genetic and dietary regulation. Cell Metab 17: 49–60, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bergheim I, Weber S, Vos M, Kramer S, Volynets V, Kaserouni S, McClain CJ, Bischoff SC. Antibiotics protect against fructose-induced hepatic lipid accumulation in mice: role of endotoxin. J Hepatol 48: 983–992, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bergstrom A, Kristensen MB, Bahl MI, Metzdorff SB, Fink LN, Frokiaer H, Licht TR. Nature of bacterial colonization influences transcription of mucin genes in mice during the first week of life. BMC Res Notes 5: 402, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernet MF, Brassart D, Neeser JR, Servin AL. Lactobacillus acidophilus LA 1 binds to cultured human intestinal cell lines and inhibits cell attachment and cell invasion by enterovirulent bacteria. Gut 35: 483–489, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Binder HJ. Role of colonic short-chain fatty acid transport in diarrhea. Annu Rev Physiol 72: 297–313, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjarnason I, Peters TJ, Wise RJ. The leaky gut of alcoholism: possible route of entry for toxic compounds. Lancet 1: 179–182, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bode C, Kugler V, Bode JC. Endotoxemia in patients with alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis and in subjects with no evidence of chronic liver disease following acute alcohol excess. J Hepatol 4: 8–14, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bode C, Schafer C, Fukui H, Bode JC. Effect of treatment with paromomycin on endotoxemia in patients with alcoholic liver disease—a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 21: 1367–1373, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borthakur A, Anbazhagan AN, Kumar A, Raheja G, Singh V, Ramaswamy K, Dudeja PK. The probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum counteracts TNF-α-induced downregulation of SMCT1 expression and function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299: G928–G934, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boursier J, Mueller O, Barret M, Machado M, Fizanne L, Araujo-Perez F, Guy CD, Seed PC, Rawls JF, David LA, Hunault G, Oberti F, Cales P, Diehl AM. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology 63: 764–775, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brun P, Castagliuolo I, Di Leo V, Buda A, Pinzani M, Palu G, Martines D. Increased intestinal permeability in obese mice: new evidence in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G518–G525, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bull-Otterson L, Feng W, Kirpich I, Wang Y, Qin X, Liu Y, Gobejishvili L, Joshi-Barve S, Ayvaz T, Petrosino J, Kong M, Barker D, McClain C, Barve S. Metagenomic analyses of alcohol induced pathogenic alterations in the intestinal microbiome and the effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment. PLos One 8: e53028, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caballero-Franco C, Keller K, De Simone C, Chadee K. The VSL#3 probiotic formula induces mucin gene expression and secretion in colonic epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G315–G322, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai D, Yuan M, Frantz DF, Melendez PA, Hansen L, Lee J, Shoelson SE. Local and systemic insulin resistance resulting from hepatic activation of IKK-β and NF-κB. Nat Med 11: 183–190, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Candela M, Perna F, Carnevali P, Vitali B, Ciati R, Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Campieri M, Brigidi P. Interaction of probiotic Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains with human intestinal epithelial cells: adhesion properties, competition against enteropathogens and modulation of IL-8 production. Int J Food Microbiol 125: 286–292, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Canfora EE, Jocken JW, Blaak EE. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11: 577–591, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, Waget A, Delmee E, Cousin B, Sulpice T, Chamontin B, Ferrieres J, Tanti JF, Gibson GR, Casteilla L, Delzenne NM, Alessi MC, Burcelin R. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 56: 1761–1772, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carvalho BM, Guadagnini D, Tsukumo DM, Schenka AA, Latuf-Filho P, Vassallo J, Dias JC, Kubota LT, Carvalheira JB, Saad MJ. Modulation of gut microbiota by antibiotics improves insulin signalling in high-fat fed mice. Diabetologia 55: 2823–2834, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carvalho BM, Saad MJ. Influence of gut microbiota on subclinical inflammation and insulin resistance. Mediat Inflamm 2013: 986734, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cash HL, Whitham CV, Behrendt CL, Hooper LV. Symbiotic bacteria direct expression of an intestinal bactericidal lectin. Science 313: 1126–1130, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang B, Sang L, Wang Y, Tong J, Zhang D, Wang B. The protective effect of VSL#3 on intestinal permeability in a rat model of alcoholic intestinal injury. BMC Gastroenterol 13: 151, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Charlton M, Krishnan A, Viker K, Sanderson S, Cazanave S, McConico A, Masuoko H, Gores G. Fast food diet mouse: novel small animal model of NASH with ballooning, progressive fibrosis, and high physiological fidelity to the human condition. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 301: G825–G834, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen P, Miyamoto Y, Mazagova M, Lee KC, Eckmann L, Schnabl B. Microbiota protects mice against acute alcohol-induced liver injury. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39: 2313–2323, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen P, Starkel P, Turner JR, Ho SB, Schnabl B. Dysbiosis-induced intestinal inflammation activates tumor necrosis factor receptor I and mediates alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology 61: 883–894, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen P, Torralba M, Tan J, Embree M, Zengler K, Starkel P, van Pijkeren JP, DePew J, Loomba R, Ho SB, Bajaj JS, Mutlu EA, Keshavarzian A, Tsukamoto H, Nelson KE, Fouts DE, Schnabl B. Supplementation of saturated long-chain fatty acids maintains intestinal eubiosis and reduces ethanol-induced liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology 148: 203–214 e216, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y, Yang F, Lu H, Wang B, Chen Y, Lei D, Wang Y, Zhu B, Li L. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 54: 562–572, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen YM, Liu Y, Zhou RF, Chen XL, Wang C, Tan XY, Wang LJ, Zheng RD, Zhang HW, Ling WH, Zhu HL. Associations of gut-flora-dependent metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide, betaine and choline with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Sci Rep 6: 19076, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chiu WC, Huang YL, Chen YL, Peng HC, Liao WH, Chuang HL, Chen JR, Yang SC. Synbiotics reduce ethanol-induced hepatic steatosis and inflammation by improving intestinal permeability and microbiota in rats. Food Function 6: 1692–1700, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chou CJ, Membrez M, Blancher F. Gut decontamination with norfloxacin and ampicillin enhances insulin sensitivity in mice. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Paediatr Programme 62: 127–140, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chumbler NM, Farrow MA, Lapierre LA, Franklin JL, Haslam DB, Goldenring JR, Lacy DB. Clostridium difficile toxin B causes epithelial cell necrosis through an autoprocessing-independent mechanism. PLoS Pathog 8: e1003072, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cope K, Risby T, Diehl AM. Increased gastrointestinal ethanol production in obese mice: implications for fatty liver disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 119: 1340–1347, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cresci GA, Bush K, Nagy LE. Tributyrin supplementation protects mice from acute ethanol-induced gut injury. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38: 1489–1501, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crespo J, Cayon A, Fernandez-Gil P, Hernandez-Guerra M, Mayorga M, Dominguez-Diez A, Fernandez-Escalante JC, Pons-Romero F. Gene expression of tumor necrosis factor-α and TNF receptors, p55 and p75, in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients. Hepatology 34: 1158–1163, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.den Besten G, Bleeker A, Gerding A, van Eunen K, Havinga R, van Dijk TH, Oosterveer MH, Jonker JW, Groen AK, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. Short-chain fatty acids protect against high-fat diet-induced obesity via a PPARγ-dependent switch from lipogenesis to fat oxidation. Diabetes 64: 2398–2408, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]