Abstract

Malignant pleural effusion (PE) and ascites, common clinical manifestations in advanced cancer patients, are associated with a poor prognosis. However, the biological characteristics of malignant PE and ascites are not clarified. Here we report that malignant PE and ascites can induce a frequent epithelial-mesenchymal transition program and endow tumor cells with stem cell properties with high efficiency, which promotes tumor growth, chemoresistance, and immune evasion. We determine that this epithelial-mesenchymal transition process is mainly dependent on VEGF, one initiator of the PI3K/Akt/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. From the clinical observation, we define a therapeutic option with VEGF antibody for malignant PE and ascites. Taken together, our findings clarify a novel biological characteristic of malignant PE and ascites in cancer progression and provide a promising and available strategy for cancer patients with recurrent/refractory malignant PE and ascites.

Keywords: cancer biology, cancer stem cells, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), tumor therapy, VEGF, ascites, malignant pleural effusion

Introduction

Malignant PE/ascites3 occur frequently in common neoplasms, including lung, breast, ovarian, colorectal cancers, and so on, which not only indicate a poor prognosis but also make patients suffer troublesome symptoms like pain, dyspnea, nausea, and hypoalbuminemia (1, 2). Clinically, the primary reason for clinical symptoms is a large accumulation of exudates. However, the poor prognosis cannot be entirely attributed to the volume of malignant PE/ascites. Studies found that there was worse survival in non-small cell lung cancers patients even with minimal PE (3), and metastatic spread and relapse would increase when cancer cells are exposed to ascites in patients with early-stage ovarian cancer (4, 5). Malignant PE/ascites usually indicate metastatic disease. Extensive carcinomatosis can be frequently observed in the pleura or peritoneum by endoscopy (6, 7). A high level of lactate dehydrogenase is an important marker to differentiate malignant from benign PE and ascites, which may suggest rapid proliferation of cancer cells and rapid progression (7). Furthermore, it is difficult to control malignant PE/ascites using chemotherapy even with high doses, and repeated onset of relapse-accumulated exudates finally results in rapid disease deterioration. Therefore, cancer cells actually obtained more aggressive biological properties, including rapid proliferation, extensive implants, and treatment resistance, when they were exposed to the malignant PE/ascites microenvironment. Emerging investigations have suggested that cancer cells probably gain phenotypes of EMT and cancer stem cells (CSCs), which may account for a poor prognosis (7–9).

EMT is an important biological program that plays a pivotal role in cancer development, self-renewal, progression, and metastasis (10–13). Furthermore, EMT-associated gene expression shows strong associations with CSCs, and EMT endows cancer cells with stem cell-like properties, such as resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (13, 14). EMT seems to be regulated by contextual signals received from the microenvironment. Malignant exudates from cancer patients have elevated inflammation-related cytokines, including IL-6, TGF-β, VEGF, and so on, which are potential regulators for EMT (15–18). Thus, malignant PE/ascites actually establish a microenvironment to facilitate the processes of EMT and further the generation and maintenance of the CSC state. There are several investigations showing that cancer cells experience EMT and gain a stem cell phenotype within malignant PE/ascites (9, 19, 20). So far, however, there are no available strategies to inhibit these processes because the underlying mechanisms are barely understood. Finding the key mediator within malignant PE/ascites may be important to develop an available strategy to improve the prognosis of patients with malignant PE/ascites.

Here we confirmed that malignant PE/ascites could induce EMT in multiple tumors and help cancer cells to gain CSC properties with high frequency and efficiency. We found that malignant exudates showed universal induction activity regardless of tumor type and origin and that non-CSCs underwent EMT and got into a CSC state de novo when exposed to malignant PE/ascites. This process was associated with VEGF-mediating PI3K/mTOR pathway activation. Clinical observations further showed that anti-VEGF therapy could inhibit EMT and was effective for malignant PE/ascites management. Our data suggest that targeting VEGF-mediating mTOR activation in combination with conventional therapy could be an available strategy to better control malignant PE/ascites through inhibiting EMT and eliminating CSCs.

Results

Malignant PE/Ascites Induce EMT in Vivo and in Vitro

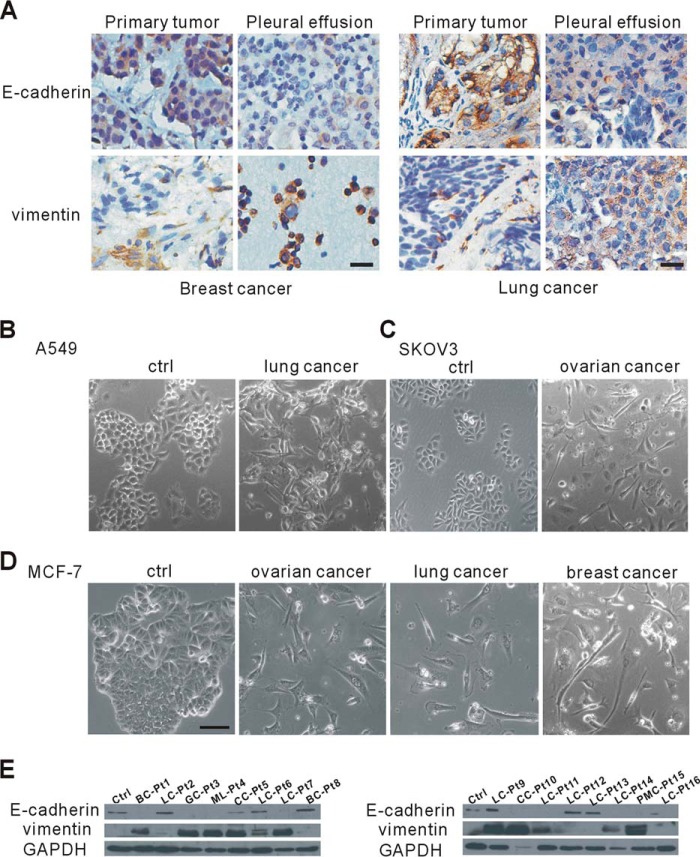

Cancer cells undergoing EMT lose epithelial characteristics and switch to a mesenchymal phenotype, which is required for further invasion and metastasis (21). Extensive and rapid spread are common in malignant PE/ascites (6, 7), which suggests that cancer cell EMT occurs in malignant PE/ascites. To confirm this, we first analyzed the differential expression of EMT markers in matched specimens of primary and exfoliative tumor cells from identical patients. In the primary sites of human breast cancer, the epithelial cell marker E-cadherin was highly expressed in tumor cells, whereas vimentin, a mesenchymal marker, was mainly expressed in the tumor stroma, with none or little in epithelial tumor cells (Fig. 1A). Then we compared the expression of E-cadherin and vimentin in primary lung cancer cells with that of exfoliative cancer cells in malignant PE. We also found that many tumor cells in the malignant PE lost E-cadherin but showed an increase in vimentin expression (Fig. 1A). To further confirm the universality of this phenomenon, we examined EMT marker expression in human lung tumor tissues and found that primary cancer cells in those malignant tissues all showed high E-cadherin and little vimentin expression. This phenomenon also existed in rectal and ovarian tumor tissues (data not shown). Our results indicated that there were a lot of EMT cancer cells in malignant PE/ascites but only a few EMT cancer cells in primary tumors. These results suggested that malignant PE/ascites significantly induced EMT in different types of tumors.

FIGURE 1.

Malignant pleural effusion and ascites induce EMT in vivo and in vitro. A, human breast tumor samples (left panel, n = 5) and lung tumor samples (right panel, n = 22) as well as their corresponding exfoliative cells in pleural effusion were immunostained for E-cadherin and vimentin and counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bars = 20 μm. B–D, representative phase-contrast images of human lung tumor cells (A549, B), human ovarian tumor cells (SKOV3, C) and human breast cancer MCF-7 cells (D) cultured in malignant pleural effusion or ascites from patients with the indicated cancers. Scale bar = 50 μm. Ctrl, control. E, altered expression of E-cadherin and vimentin in MCF-7 cells, as revealed by Western blotting analysis. GAPDH served as the loading control. Pt, patient; BC, breast cancer; LC, lung cancer; GC, gastric cancer; ML, malignant lymphoma; CC, colorectal cancer; PMC, peritoneal mesothelioma.

Given that tumor cells acquire a mesenchymal phenotype in malignant PE/ascites, we tested the possibility that patient-derived malignant PE/ascites could induce EMT in different cancer cell lines. We cultured human lung cancer cells (A549), ovarian cancer cells (SKOV3), and breast cancer cells (MCF-7) in PE and ascites from patients with lung, ovarian, and breast cancer, respectively. The clinical characteristics of PE and ascites are summarized in supplemental Table S1. After long-term culture (14–30 days) in malignant PE/ascites, most if not all cancer cells displayed a typical EMT phenotype and were scattered and changed from cuboidal to spindle shape (Fig. 1, B–D). Besides malignant PE from breast cancer patients, we also used malignant PE/ascites from patients with lung, ovarian, and colorectal cancers and lymphoma to culture MCF-7 tumor cells. We found that most of the malignant PE/ascites we collected could induce the EMT process in MCF-7 cells with high frequency, independent of the original cancer types (Fig. 1D), which indicated that some common ingredients probably existed in malignant PE/ascites. To further demonstrate the EMT process, we evaluated epithelial and mesenchymal marker expression on MCF-7 tumor cells. In the presence of malignant PE/ascites from different patients with lung, breast, gastric, and ovarian cancer, lymphoma, or mesothelioma, E-cadherin was lost, and the expression of vimentin was increased (Fig. 1E). These results further suggest that malignant PE/ascites can induce cancer cells to undergo EMT and acquire mesenchymal traits and that the induction capacities of malignant PE/ascites is universal for different types of cancer cells.

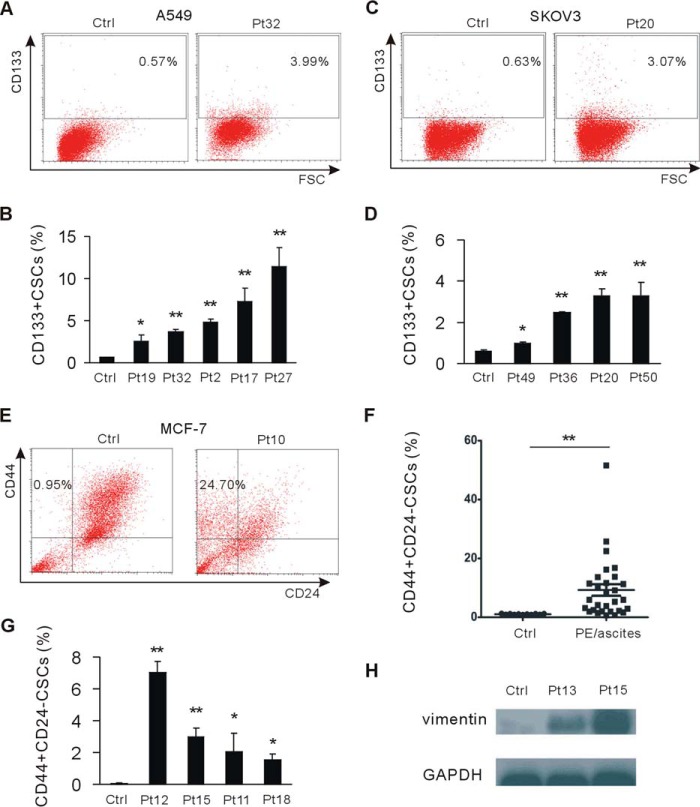

Cancer Cells Undergoing EMT Gain the Phenotype of Cancer Stem Cells

EMT cells express stem cell markers and gain stem cell-like characteristics (14). To investigate whether tumor cells in malignant PE/ascites gain the stem cell phenotype, we assessed the stem cell phenotype in A549 and SKOV3 tumor cells cultured in malignant PE/ascites. We observed the substantially increased CD133+ stem cell population in these two cell lines (Fig. 2, A–D). We further assessed the proportion of the CD44+/CD24− subpopulation, which is associated with human breast cancer stem cells (22). Upon exposure to malignant PE/ascites, the number of CD44+/CD24− CSCs was significantly increased (Fig. 2, E and F).

FIGURE 2.

Malignant pleural effusion and ascites endow cancer cells with a cancer stem cell phenotype. A and B, A549 tumor cells were cultured in malignant pleural effusion and stained with anti-CD133 antibody by direct staining, analyzed, and quantified by flow cytometry. CD133-positive stem cells were quantified. Ctrl, control; Pt, patient; FSC, forward scatter. C and D, flow cytometry analysis of SKOV3 tumor cells cultured in malignant ascites for CD133-positive stem cells. CD133-positive stem cells were quantified. E and F, flow cytometry analysis of MCF-7 cells cultured in malignant pleural effusion and ascites and their parental cells for CD44 and CD24. CD44+/CD24− stem cells were quantified. G, non-cancer stem cells were cell sorted from MCF-7 cells and cultured in malignant pleural effusion and ascites. The CD44+/CD24− cancer stem cell population was analyzed by flow cytometry. H, non-CSCs were cultured in malignant pleural effusion and ascites. The level of vimentin was measured by Western blotting. GAPDH served as the loading control. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Next we sought to determine whether malignant PE/ascites promote the breast CSCs phenotype by converting a subset of non-CD44+/CD24− CSCs (hereafter termed non-CSCs) into CSCs. We sorted non-CSCs by FACS and cultured them in malignant PE/ascites. The results showed that the CSC population was also significantly increased in malignant PE/ascites-treated groups compared with control groups (Fig. 2G). We then evaluated the expression of mesenchymal markers and showed that non-CSCs cells gained more vimentin expression when exposed to malignant PE/ascites (Fig. 2H), indicating that malignant PE/ascites promoted the CD44+/CD24− CSCs phenotype by inducing dedifferentiation in non-CSC cells. Collectively, these data suggest that malignant PE/ascites can strongly promote CSCs generation.

Malignant PE/Ascites Potentiate Tumor Growth and Therapy Resistance

Both the EMT and CSC phenotype show aggressive biological characteristics, including increased invasion, metastatic ability, and resistance to therapy (11, 13, 23). To test whether tumor cells cultured under conditions of malignant PE/ascites gain a growth advantage, ascites-cultured SKOV3 cells were implanted subcutaneously into the flank of immunodeficient BALB/c-nude mice; the same number of control parental cells was implanted into the contralateral flank. 23 days later, tumor volume and weight was assessed. SKOV3 cell cultured with malignant ascites generated significantly larger tumors relative to their paired controls (Fig. 3A), with a 2.5- to 4-fold increase in tumor weight compared with their paired control tumors on the contralateral flanks (Fig. 3A). The resulting tumors were examined by histopathology. Compared with their parental cell-derived tumors, tumors formed from ascites-cultured cells displayed a higher ki67 proliferation index and tumor vasculatures (Fig. 3, B and C), characteristics of aggressive growth, indicating that ascites confer a growth advantage on tumor cells in vivo.

FIGURE 3.

Malignant pleural effusion and ascites promote tumor growth and therapy resistance. A, SKOV3 cells cultured in ascites were subcutaneously injected into athymic nude BALB/C mice (n = 3–5). Shown are representative pictures of tumors and quantification of tumor weight. Ctrl, control; Pt, patient. B, representative images of ki-67 stains showing that cancer cells in the malignant ascites group had a higher proliferation index. Scale bar = 50 μm. C, immunofluorescent images showing that tumors in the malignant PE and ascites group had more tumor vasculature. Scale bar = 50 μm. D, MCF-7 and malignant PE and ascites-treated MCF-7 cells were exposed to the chemotherapeutic agents cisplatin and paclitaxel. Cell viability was determined by flow cytometry using Annexin V/PI staining. Shown is quantification of cell viability. E, the level of the multidrug resistance genes ABCB1 and ABCG2 was analyzed with an RT-PCR assay. F, IL-2/IL-15 activated NK cell cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells cultured in malignant PE and ascites at a range of E:T ratios compared with their parental cells. G, flow cytometry analysis of MHC-I expression on the surface of MCF-7 tumor cells. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

We then hypothesized that tumor cells pretreated with malignant PE/ascites would be resistant to chemotherapeutic drugs. MCF-7 cells were exposed to cisplatin or paclitaxel for 24 h, and chemosensitivity was determined by flow cytometry for the proportion of live cells. MCF-7 cells cultured in malignant PE exhibited a significantly higher survival rate after cisplatin or paclitaxel treatment (Fig. 3D). Moreover, malignant PE/ascites induced the expression of ABCB1 and ABCG2 (Fig. 3E), two putative CSC markers, protecting cancer stem cells from chemotherapeutic agents (24). On the other hand, recent reports show that allogeneic NK cells preferentially target cancer stem cells (25). To test whether malignant PE/ascites influence the susceptibility to cytotoxicity of NK cells, we analyzed malignant PE/ascites-cultured tumor cells for their susceptibility to IL-2/IL-15-activated NK cell populations derived from healthy donors. We found that malignant PE/ascites-cultured tumor cells were more resistant to NK cell cytotoxicity (Fig. 3F). NKG2D receptor-ligand interaction was required for NK cell killing activity (26). To test whether malignant PE/ascites influence NKG2D ligand expression, we evaluated the surface levels of ULBP1, ULBP2, and MICA on tumor cells. The expression of the NKG2D ligands ULBP1, ULBP2, and MICA was not significantly changed after malignant PE/ascites treatment (data not shown). However, MHC-I molecules were up-regulated by malignant PE/ascites from different patients (Fig. 3G). Those results demonstrate that cancer cells are resistant to chemotherapy and NK-mediated cytotoxicity in the microenvironment of malignant PE/ascites.

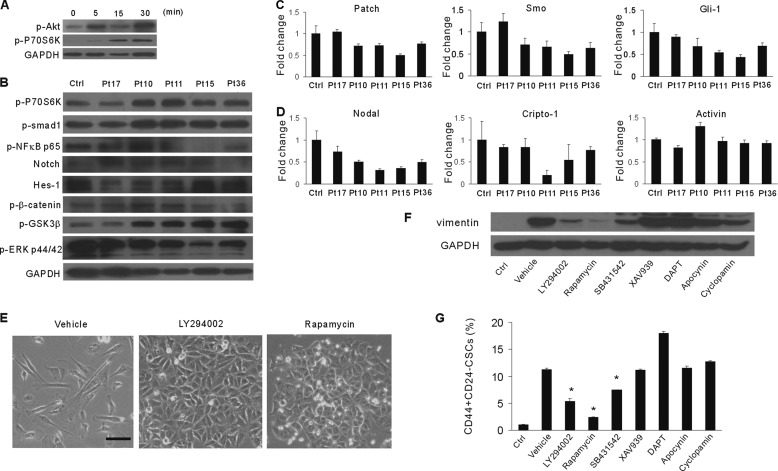

Malignant PE/Ascites Promote EMT through Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway

Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway plays a critical role in promoting EMT and stem-like properties in several tumors (27). We first investigated whether the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway was activated in cancer cells cultured within malignant PE/ascites. P70S6 kinase ribosomal protein is a downstream target of mTOR (28). Exposure of MCF-7 cells to malignant PE/ascites for 5, 15, and 30 min resulted in activation of Akt and P70S6K, as revealed by elevated phosphorylation levels (Fig. 4, A and B). Although malignant PE from patient 17 did not activate the mTOR pathway at 30 min, it obviously elevated the phosphorylation level of p70S6K when exposed for a longer time (1 and 2 h, data not shown). Glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) is a well characterized AKT substrate. Phosphorylation of GSK-3β on the Ser-9 site by Akt inactivates its kinase activity. MCF-7 cells treated with malignant PE/ascites had a significant increase in GSK-3β phosphorylation (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Malignant PE and ascites functionally activate the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. A, MCF-7 cells were treated with malignant PE and ascites at the indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against p-Akt and p-P70S6K. GAPDH served as the loading control. B, Western blotting for p-P70S6K, p-Smad1, p-NFκB p65, Notch, Hes-1, p-β-catenin, p-GSK3β, p-MAPK p44/p46, and GAPDH after stimulation with malignant PE and ascites for 30 min. GAPDH served as the loading control (Ctrl). Pt, patient. C and D, MCF-7 cells were treated with malignant PE and ascites for 30 min. Shown is quantitative PCR analysis of hedgehog (C) and nodal/activin (D) pathway-associated genes. Data were normalized to human GAPDH expression and are presented as -fold change relative to parental MCF-7 cells. E, representative images of the morphology of MCF-7 cells after treatment with malignant PE/ascites as well as antagonists of pan-PI3K (LY294002) and mTOR (rapamycin) inhibitors. Scale bar = 50 μm. F, Western blotting analysis of vimentin expression of MCF-7 cells after treatment with malignant PE/ascites as well as the indicated antagonists. G, flow cytometry analysis and quantification of CD44+/CD24− cancer stem cells in MCF-7 cells after treatment with malignant PE/ascites as well as the indicated antagonists. *, p < 0.05.

We further analyzed the effect of malignant PE/ascites on the Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways, known to regulate stem cell characteristics (13, 29, 30). We confirmed no obvious activation of the Notch pathway in MCF-7 tumor cells by Western blotting for Notch intracellular domains (NICDs) and Hes-1 protein. There was also no obvious increase in β-catenin Ser-552 phosphorylation (Fig. 4B), which was associated with enhanced transcription (29). Cancer cells cultured in malignant PE/ascites showed increased smad1 phosphorylation (Fig. 4B). Next, we analyzed the mRNA transcripts encoding components of the Hedgehog signaling pathway. There was no significant transcriptional elevation in the levels of components of the Hedgehog pathway, such as patch, smo, or gli-1 (Fig. 4C). Previous reports show that Nodal/Activin signaling regulates the self-renewal of cancer stem cells in several types of cancers (31). Here we showed that the gene expression levels for nodal, cripto-1, and activin were not obviously elevated (Fig. 4D).

To further validate the importance of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR/p70S6K pathway in EMT induction, we used a plethora of chemical inhibitors to antagonize associated signaling pathways. We cultured MCF-7 tumor cells in malignant PE/ascites together with pan-PI3K (LY294002), mTOR (rapamycin), TGF-β receptor (SB431542), notch (DAPT), Wnt (XAV939), Hedgehog (cyclopamine), or NADPH oxydase (apocynin) inhibitors. We found that LY294002 and rapamycin protected against the malignant PE/ascites-induced EMT process, as reflected by the cuboidal morphology (Fig. 4E), decreased vimentin expression, and reduced cancer stem cells (Fig. 4, F and G). Although the TGF-β receptor inhibitor SB431542 showed inhibition of the EMT and CSCs state, the inhibitory efficacy was significantly less than that of LY294002 and rapamycin. Moreover, no effect of DAPT, XAV939, cyclopamine, and apocynin was observed. These results indicate that the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway is essential for malignant PE/ascites-induced EMT and CSCs.

To further confirm the key role of mTOR and the potential application for malignant PE/ascites management by targeting mTOR, we tested whether the antitumor efficacy of the chemotherapeutical agent cisplatin could be enhanced by synergy with the commercial mTOR inhibitor rapamycin in a mouse model. We observed that both rapamycin and cisplatin are efficient at reducing abdomen circumference and tumor burden in the SKOV3 ovarian cancer xenograft model; however, either single agent is less effective than the combination therapy (supplemental Fig. S1). These findings indicate that targeting mTOR may be an effective strategy to sensitize intrapleural or intraperitoneal chemotherapy for malignant PE/ascites.

VEGF Is Associated Primarily with the EMT and CSC State and Is an Effective Target in Malignant PE/Ascites

The composition of malignant PE/ascites is highly diverse and forms a complicated microenvironment. To find the upstream factor for mTOR activation, we first assessed it on albumin, as it represents a universal component in exudates and was reported to activate the mTOR pathway and induce EMT in tubular epithelial cells (32). However, human albumin at various concentrations could not initiate the EMT process of cancer cells in malignant PE/ascites (supplemental Fig. S2A). Albumin could not change the EMT markers in MCF-7 tumor cells (supplemental Fig. S2B), although it slightly increased the proportion of CD44+/CD24− CSCs (supplemental Fig. S2C).

It is generally believed that several cytokines can induce EMT (33, 34). We examined the cytokine profile known to initiate EMT in malignant PE/ascites. Using ELISA and a luminex-based multiplex bead array system, we found that several cytokines, including VEGF, osteopontin (OPN), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-8, were abundant in the supernatant from malignant PE/ascites (supplemental Fig. S3). Notably, many of those factors were above the reported level in published data and were demonstrated to induce EMT in vitro through analysis of published data (35, 36). We also noted that, in most patients, several cytokines measured in the multiplex assay were below the detection limit, including IL-1β, IL-13, IL-17, PDGF, EGF, RANTES, FGF-2, Endothelin-1, and BMP-9 (supplemental Fig. S3 and data not shown).

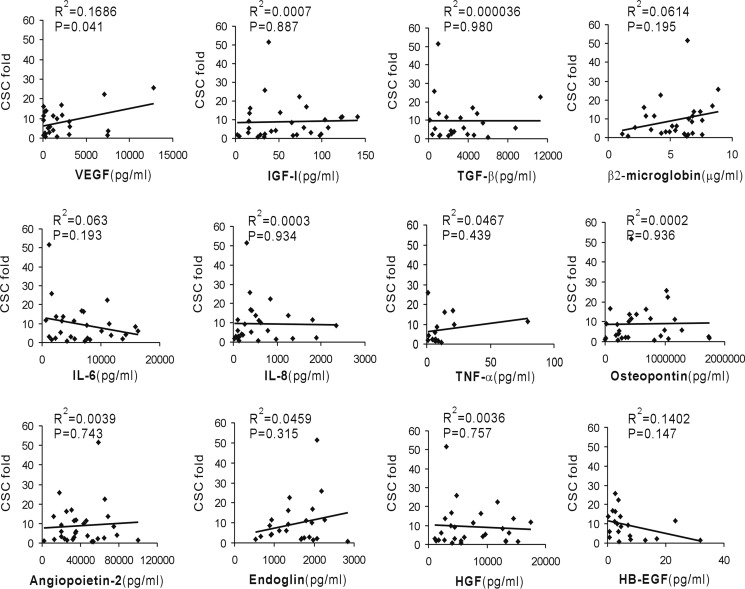

To investigate which cytokine is the primary mediator of EMT events induced by malignant PE/ascites, we analyzed the correlation between CSC increase and cytokine concentration. The increased CSCs positively correlated with VEGF concentration but not with other cytokine levels, including IGF-I, TGF-β, β2-macroglobin, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, OPN, HGF, angiopoietin-2, endoglin, and HB-EGF (Fig. 5). These results strongly imply that VEGF mediates, to a great extent, the EMT induction activity and cancer stem cell state in malignant PE/ascites. We also determined VEGF neutralization on mTOR activation. Treatment of PE/ascites with an anti-VEGF blocking antibody had an obvious effect in reverting mTOR activation, although it did not show a sharp drop (supplemental Fig. S4).

FIGURE 5.

VEGF correlates with cancer stem cell increase induced by malignant PE and ascites. The -fold increase in cancer stem cells was plotted against the concentration of VEGF, IGF-I, TGF-β, β2-microglobumin, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, osteopontin, angiopoietin-2, endoglin, HGF and HB-EGF. Linear regressions were traced according to the distribution of points.

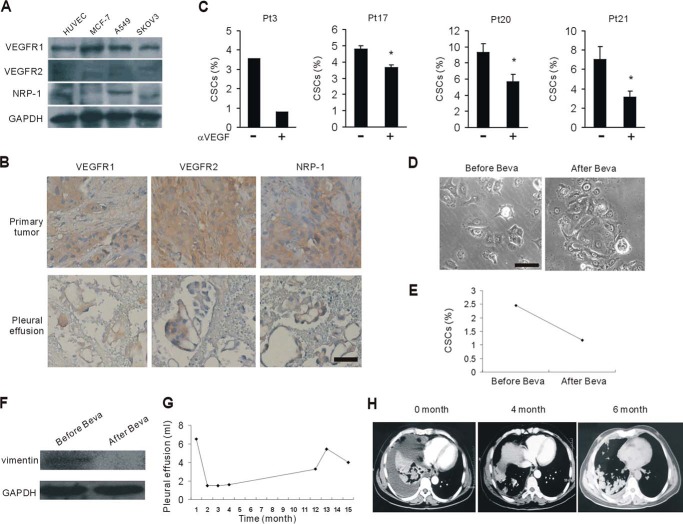

Next we assessed the VEGFRs, including VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and neuropilin-1 (NRP-1), on the cell lines we used. Almost all three receptors were expressed on MCF-7, A549, and SKOV3 cells (Fig. 6A). Then the expression pattern of VEGFRs was determined on primary tumor tissues and cancer cells in pleural effusion from the same patients with breast cancer. We found that VEGFR1, VEGFR2, or neuropilin-1 was expressed on cancer cells irrespective of their origin (Fig. 6B). To determine whether VEGF neutralization reduced cancer stem cells, we applied the blocking antibodies specific for VEGF to malignant PE and ascites prior to the culture. Specific blockade of VEGF showed various abrogations of the CSC induction properties of malignant PE and ascites (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Targeting VEGF effectively antagonizes protumor effects of malignant PE and ascites. A, Western blotting assessed the expression of VEGFRs on the MCF-7, A549, and SKOV3 cancer cell lines. HUVECs were the positive control. B, the expression of VEGFRs was evaluated in primary breast cancer samples and their corresponding exfoliative cells in pleural effusion (n = 5). Scale bar = 50 μm. C, flow cytometry analysis of CD44+/CD24− cancer stem cells in malignant PE/ascites-cultured MCF-7 cells in the presence of neutralizing VEGF antibodies. *, p < 0.05. Pt, patient. D–F, MCF-7 tumor cells were cultured in ascites before and after bevacizumab (Beva) therapy, respectively, from a 50-year-old male with a history of metastatic colorectal cancer. Cell morphology was photographed under a microscope (D). Scale bar = 50 μm. CD44+/CD24− cancer stem cells (E) and vimentin expression (F) in D was assessed by flow cytometry and Western blotting, respectively. G and H, a 57-year-old lung cancer patient with refractory malignant PE received intravenous bevacizumab therapy. The pleural effusion volume in G was tracked. Shown are representative images from computed tomography scans of the chest documenting responses to the bevacizumab therapies in H. Images revealed the massive right-sided PE on admission. PE was obviously reduced after treatment with two doses of bevacizumab.

Bevacizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody specifically targeting VEGF for advanced lung cancers and metastatic colorectal cancers (37, 38). To investigate whether the malignant PE/ascites from bevacizumab-treated patients can block the EMT process, we collected ascites before and after bevacizumab therapy from a patient with a history of metastatic colorectal cancer. Subsequently, we cultured MCF-7 tumor cells in those ascites. Interestingly, we observed that tumor cells cultured in the ascites after bevacizumab were not as scattered as those in the ascites before treatment (Fig. 6D). Consistent with the morphology changes, the tumor population cultured in ascites after bevacizumab therapy had less CD44+/CD24− CSCs (Fig. 6E) and decreased mesenchymal marker vimentin expression (Fig. 6F), suggesting that bevacizumab can partially, if not completely, prevent EMT events in malignant PE/ascites. We also observed the efficacy of bevacizumab in several lung cancer patients with malignant PE/ascites (data not shown).

From the clinical observation, we defined a therapeutic option with VEGF antibody for malignant PE and ascites. A 57-year-old male with lung adenocarcinoma had refractory malignant PE. Systemic cisplatin-based chemotherapy and intrapleural chemotherapy with cisplatin failed to control malignant PE. A computed tomography scan obtained upon his admission in June 2013 revealed massive right-sided PE. He had about 1000–1500 ml of bloody exudate every day for 6 continuous days. He received intravenous bevacizumab (7.5 mg/kg) 5 days before intrapleural chemotherapy with cisplatin (60 mg). Surprisingly, the malignant PE was controlled after the combination treatment. Then he received four cycles of docetaxel and another dose of bevacizumab during the second cycle. Then he underwent steady control of PE for more than 1 year, as revealed by iconography data (Fig. 6, G and H). These data indicate that anti-VEGF therapy may present an effective strategy for cancer patients with malignant PE/ascites.

Discussion

Cancer patients with malignant PE/ascites have an extremely poor prognosis not only because of the advanced stage but also because cancer cells in malignant PE/ascites could acquire more aggressive properties. Rapid growth, extensive spread, and enhanced resistance to treatment result in rapid relapse and disease progression. We found here, from clinical specimens and in vitro experiments, that cancer cells in malignant PE/ascites underwent EMT and displayed a cancer stem cells phenotype, which could account for the poor prognosis. Here, besides confirming the phenomena described previously (9, 19, 20), we also found that malignant exudates had universal induction activity regardless of tumor type and origin. More importantly, we noted that non-CSCs could undergo EMT process and be directly converted into the CSC state when exposed to malignant PE/ascites; therefore, blocking the process in combination with conventional chemotherapies is critical to better control malignant PE/ascites.

Prior studies have shown that when non-CSCs undergo EMT, they can dedifferentiate into CSC-like cells after acquiring characteristics of cells in EMT (14). The stem cell property endowed cancer cells with a growth advantage, which was confirmed in our SKOV3 cancer model. EMT and cancer stem cells also represent a major factor in chemotherapeutical resistance (13). We showed in vitro that cancer cells exposed to malignant PE/ascites were less responsive to chemotherapy, accompanied by increased expression of multidrug resistance genes. Besides, given that different immune cell populations are present in malignant PE/ascites, we also focused on the cytotoxicity of immune cells on cancer cells cultured with malignant exudates. Previous studies have shown that malignant PE/ascites foster immune privilege and facilitate tumor cell survival (39, 40). One of these reports shows that tumor cells in the peritoneal cavity express PD-L1 and escape from CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes (40). Previously, studies reported that NK cells can recognize and kill tumor cells in an MHC-independent manner and that allogeneic NK cells preferentially target cancer stem cells (25, 41). In this study, we found that cancer cells experienced EMT and acquired a CSC phenotype when exposed to malignant PE/ascites. Unexpectedly, these cancer cells were resistant to cytolysis mediated by NK cells, probably because of the high level of MHC-I expression induced by the cytokine milieu in malignant exudates (Fig. 3G). Notably, in the course of our experiment, we also observed some inconsistency between EMT and CSCs that challenged previous reports (14). We postulated that this might be due to the special microenvironment we used here, which was enriched with many cytokines, as we reported, and was a more complex microenvironment. Therefore, malignant PE/ascites represent a favorable microenvironment for tumor progression and treatment refraction because of perpetual EMT and CSC conversion, which, in turn, facilitate PE and ascites formation, forming a vicious cycle.

Many factors are reported to initiate cancer cell EMT through different pathways. In this study, we paid more attention to finding the critical mediator that impairs EMT and CSC processes. Notably, EMT induced by malignant PE/ascites was independent of the wnt, hedgehog, and nodal pathways. However, as we demonstrated, this process relies mainly on the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, which plays an important role in the process of EMT (27). Constitutive activation of Akt promotes the transcription of Snail and Zeb1, which is known to repress E-cadherin expression (21). We showed that EMT induced by malignant PE/ascites could be inhibited by the pan-PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin. We also confirmed the important role of mTOR in impairing EMT and reversing chemoresistance in a SKOV3 mouse model using the mTOR inhibitor. We further investigated the upstream initiator of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. A plethora of evidence suggests that inflammation promotes EMT (42). We considered that the malignant PE/ascites microenvironment may also represent an inflammatory microenvironment. We thus screened the cytokine profiles and found that those microenvironment enrich a variety of cytokines with abundant VEGF, IGF-I, HGF, OPN, TGF-β, IL-6, and IL-8. TNF-α, angiopoietin-2, endoglin, and HB-EGF were also enriched in many patients. However, IL-1β, IL-13, IL-17, PDGF, EGF, RANTES, FGF-2, Endothelin-1, and BMP-9 were not detectable in the majority of patients. Of those enriched cytokines, many can activate receptor tyrokinase, which subsequently activates the PI3K pathway (43, 44). However, our data indicated that VEGF was most relevant to EMT induction. Targeting VEGF was also demonstrated to obviously impair the EMT and CSC state both in vitro and in vivo. Indeed, VEGF was reported to induce EMT in human pancreatic cancer cells (35). Previous investigations reported that cancer cell EMT and gain of CSC properties in malignant PE/ascites depended on TrkB and TGF-β signaling, respectively (9, 45). TrkB is a well established regulator that promotes VEGF expression (46). Of course we cannot exclude additional factors inducing this effect, as we observed that VEGF neutralization substantially but not fully blocked mTOR activation and CSC increases. In our study, we also found that TGF-β signaling was involved in the EMT process but significantly weaker than VEGF signaling. Taken together, targeting VEGF could be an applicable strategy for impairing the process in malignant PE/ascites.

In the clinical setting, intrapleural and intraperitoneal chemotherapy are common modalities for malignant PE/ascites management. So far, there are no reports that mTOR inhibitors were used for malignant PE/ascites management even though some of them are available clinically, whereas the efficacy of anti-VEGF therapy with bevacizumab, a VEGF antibody, by intrapleural or intraperitoneal administration for malignant PE/ascites has been frequently reported (47–49). One mechanism of bevacizumab is that it reduces vascular permeability induced by VEGF (50). Here we observed that malignant PE/ascites from patients treated with bevacizumab lost EMT and CSC induction activity. Therefore, our study clarified a novel role of anti-VEGF, which was associated with EMT process blockade and CSCs decrease in malignant PE/ascites. Our study also supported the rationality of local anti-VEGF antibody administration when used for malignant PE/ascites management. Inasmuch as VEGF blockade reduces EMT and CSCs, anti-VEGF therapy may be a reasonable option for patients with malignant exudates.

In summary, our study shows that EMT and CSCs induced by malignant PE/ascites are highly dependent on the VEGF/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Targeting VEGF or mTOR is an applicable strategy to impair the EMT and CSC process in combination with conventional chemotherapy for better malignant PE/ascites management.

Experimental Procedures

Clinical Specimens

Human cancer samples and exfoliative cell samples were obtained from the Department of Pathology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University. Human malignant peritoneal effusion and ascites were collected from voluntarily consenting patients at the Cancer Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University with written informed consent according to ethics committee approval. Malignant pleural effusion and ascites were stored in −20 °C and −80 °C. The clinical information is summarized in supplemental Table S1.

Cell Culture

The human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 was maintained in DMEM (Gibco) supplied with 10% FBS (Gibco) at 37 °C and a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The human ovarian cancer cell line SKOV3, the lung cancer cell line A549, and endothelial cell line human umbilic vein endothelial cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) supplied with 10% FBS (Gibco) at 37 °C and a 5% CO2 atmosphere. All tumor cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Human NK cells were obtained from the peripheral blood of healthy donors and isolated with a magnetic bead-based technique using the NK isolation kit (R&D Systems) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. NK cell purity was >85%. NK cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 200 units/ml IL-2, and 10 ng/ml IL-15.

Antibodies and Reagents

CD44-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD24-FITC, and MHC-I-FITC antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen. The CD133-APC antibody was from Miltenyi Biotec. Antibodies against ULBP1, ULBP2, and MICA were purchased from R&D Systems. E-cadherin, vimentin, ki-67, and VEGFR1 antibodies were obtained from Abcam. Neutralizing antibody against VEGF was purchased from R&D Systems. Human albumin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. FITC-conjugated CD31 was purchased from BioLegend. VEGFR2, NRP-1, GAPDH, p-Akt, p-P70S6K, p-Smad1, p-NF-κB p65, NICDs, Hes-1, p-β-catenin, p-GSK3 β, and p-MAPK p44/p46 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. The pan-PI3K (LY294002), mTOR (rapamycin), TGF-β receptor (SB431542), notch (DAPT), Wnt (XAV939), Hedgehog (cyclopamine), and NADPH oxydase (Apoycin) inhibitors were from Sigma-Aldrich. The VEGF, IL-6, TGF-β, IGF-I, TNFα, and β2-microglobumin ELISA kits were obtained from R&D Systems. The luminex-based multiplex bead array system for IL-8, osteopontin, HGF, angiopoietin-2, endoglin, HB-EGF, IL-1β, IL-13, IL-17, PDGF, EGF, RANTES, FGF-2, Endothelin-1, and BMP-9 were from Millipore Corp. The Annexin-V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) kit was from Roche.

Flow Cytometry

Human MCF-7, A549, HCT116, and SKOV3 tumor cells were cultured in malignant PE and ascites. MCF-7 cells were treated with 20 mg/ml and 40 mg/ml human albumin. For the blocking assay, MCF-7 cells cultured in malignant PE/ascites were simultaneously treated with VEGF antibody (10 μg/ml), DMSO, LY294002 (20 μm), rapamycin (100 nm), SB431542 (20 μm), XAV939 (1 μm), DAPT (3 μm), apocynin (200 μm), and cyclopamin (10 μm). Single cell suspensions were prepared and then stained with CD44 and CD24 or CD133 antibodies, respectively, at 4 °C for 30 min. For the chemotherapy assay, tumor cells were exposed to 12.5 nm paclitaxel and 25 μg/ml cisplatin for 24 h. Apoptotic cells were stained with Annexin-V and PI at room temperature for 15 min. Tumor cells were acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer, and data were analyzed using CellQuest software (BD Pharmingen). MCF-7 tumor cells were stained with antibodies against ULBP1, ULBP2, MICA, and MHC-I.

RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

RNA was prepared from MCF-7 tumor cells using an RNA isolation kit (Axygen) and reverse-transcribed (TaKaRa) according to the protocols of the manufacturer. cDNA was used to amplify ABCB1, ABCG2, SOX2, Patch, Smo, Gli-1, Nodal, Cripto-1, and Activin. Real-time PCR was performed on a CFX 96 real-time PCR thermocycler (Bio-Rad) using a kit (SYBR Premix EX Taq, TaKaRa) with GAPDH as a reference control. The primers used in PCR are shown in supplemental Table S2. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−▵▵Ct method with GAPDH as a reference.

Western Blotting Analysis

Human MCF7, A549, and SKOV3 tumor cells cultured with malignant PE/ascites in the presence or absence of VEGF antibody or signal inhibitors and MCF-7 cells treated with human albumin were lysed with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer, and cellular extracts were resolved on SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Membranes were probed with primary antibodies against E-cadherin (1: 500), vimentin (1:1000), VEGFR1 (1:1000), VEGFR2 (1:1000), NRP-1 (1:1000), p-Akt (1:1000), p-P70S6K (1:1000), p-Smad1 (1:1000), p-NFκB p65 (1:1000), NICDs (1:1000), Hes-1 (1:1000), p-β-catenin (1:1000), p-GSK3 β (1:1000), p-MAPK p44/p46 (1:1000), and GAPDH (1:1000), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10000). Probes were visualized by a chemiluminescent detection system.

51Cr Release Cytotoxicity Assay

MCF-7 cells were labeled with 1 mCi of Na251CrO4 for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were then washed three times with complete medium and incubated with human IL-2/IL-15-activated NK cells at different effector:target ratios (40:1, 20:1, 10:1, and 5:1). After incubation for 4 h at 37 °C, cell-free supernatants were collected and counted on a scintillation counter. The percentage of cytolysis was calculated as follows: (sample release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release).

Animal Model

Animal experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sichuan University. 1 × 107 ascites-cultured SKOV3 cells were implanted subcutaneously into the flank of immunodeficient female BALB/c-nude mice (8–10 weeks old), with the same number of control SKOV3 cells implanted into the contralateral flank. 23 days later, tumor volume and weight were assessed. SKOV3 tumors were embedded in O.C.T. gel or formaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded and sectioned. For the combination therapy for the ascetic ovarian cancer model, SKOV3 tumor-bearing female BALB/c-nude mice were treated with 2 mg/kg cisplatin for 4 consecutive days (day 0–4, the first cycle), followed by a 10-day pause and subsequent treatment for another 4 consecutive days (days 15–18, the second cycle) and/or 4 mg/kg rapamycin daily, with DMSO vehicle as the control. Tumor burden was measured by tumor number and weight on day 19.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Human primary cancer samples and exfoliative cell samples were stained with E-cadherin (1:100), vimentin (1:100), VEGFR1 (1:100), VEGFR2 (1:100), and NRP-1 (1:100). SKOV3 tumor tissues from nude mice were stained with ki-67 (1:100), followed by biotin-conjugated secondary antibody and then streptavidin-HRP complex. Diaminobenzidine was used as the enzyme substrate. Samples were then counterstained with hematoxylin. CD31-FITC (1:100) was stained in frozen sections of SKOV3 tumor sections, and microvessel density was assessed.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted using two-tailed Student's t test, Mann Whitney test, one-way analysis of variance, and Pearson rank correlation test. Results were expressed as the mean ± S.D. p < 0.05 was designated as statistically significant.

Author Contributions

Y. Wang and T. Yin designed the research. T. Yin, G. W., S. H., G. S., C. S., Y. Z., X. W., T. Ye, L. L., D. L., F. G., P. A., X. Z., Z. M., Y. Wan., and Y. L. performed the research. Y. Wang, T. Yin, S. Y., and Y. Wei analyzed the data. T. Yin and G. W. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 81272523 and 81501609, National Basic Research Program of China Grant 2010CB529900, and Chinese Postdoctoral Special Funds Grant 2016T90856. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and Tables S1 and S2.

- PE

- pleural effusion(s)

- EMT

- epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- CSC

- cancer stem cell

- mTOR

- mechanistic target of rapamycin

- NK

- natural killer

- NICD

- Notch intracellular domain

- OPN

- osteopontin

- HGF

- hepatocyte growth factor

- IGF

- insulin-like growth factor

- VEGFR

- VEGF receptor

- PI

- propidium iodide

- HB-EGF

- heparin binding epithelial growth factor

- MICA

- MHC class I chain-related molecules A

- ULBP

- UL16-binding proteins.

References

- 1. Runyon B. A. (1994) Care of patients with ascites. N. Engl. J. Med. 330, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shen-Gunther J., and Mannel R. S. (2002) Ascites as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. Gynecol. Oncol. 87, 77–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ryu J. S., Ryu H. J., Lee S. N., Memon A., Lee S. K., Nam H. S., Kim H. J., Lee K. H., Cho J. H., and Hwang S. S. (2014) Prognostic impact of minimal pleural effusion in non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 960–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tan D. S., Agarwal R., and Kaye S. B. (2006) Mechanisms of transcoelomic metastasis in ovarian cancer. Lancet Oncol. 7, 925–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kolomainen D. F., A'Hern R., Coxon F. Y., Fisher C., King D. M., Blake P. R., Barton D. P., Shepherd J. H., Kaye S. B., and Gore M. E. (2003) Can patients with relapsed, previously untreated, stage I epithelial ovarian cancer be successfully treated with salvage therapy? J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 3113–3118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sakr L., Maldonado F., Greillier L., Dutau H., Loundou A., and Astoul P. (2011) Thoracoscopic assessment of pleural tumor burden in patients with malignant pleural effusion: prognostic and therapeutic implications. J. Thorac. Oncol. 6, 592–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahmed N., and Stenvers K. L. (2013) Getting to know ovarian cancer ascites: opportunities for targeted therapy-based translational research. Front. Oncol. 3, 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giarnieri E., Bellipanni G., Macaluso M., Mancini R., Holstein A. C., Milanese C., Giovagnoli M. R., Giordano A., and Russo G. (2015) Review: cell dynamics in malignant pleural effusions. J. Cell Physiol. 230, 272–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ricci A., De Vitis C., Noto A., Fattore L., Mariotta S., Cherubini E., Roscilli G., Liguori G., Scognamiglio G., Rocco G., Botti G., Giarnieri E., Giovagnoli M. R., De Toma G., Ciliberto G., and Mancini R. (2013) TrkB is responsible for EMT transition in malignant pleural effusions derived cultures from adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cell Cycle 12, 1696–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thiery J. P., Acloque H., Huang R. Y., and Nieto M. A. (2009) Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 139, 871–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scheel C., and Weinberg R. A. (2012) Cancer stem cells and epithelial-mesenchymal transition: concepts and molecular links. Semin. Cancer Biol. 22, 396–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rhim A. D., Mirek E. T., Aiello N. M., Maitra A., Bailey J. M., McAllister F., Reichert M., Beatty G. L., Rustgi A. K., Vonderheide R. H., Leach S. D., and Stanger B. Z. (2012) EMT and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell 148, 349–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pattabiraman D. R., and Weinberg R. A. (2014) Tackling the cancer stem cells: what challenges do they pose? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 497–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mani S. A., Guo W., Liao M. J., Eaton E. N., Ayyanan A., Zhou A. Y., Brooks M., Reinhard F., Zhang C. C., Shipitsin M., Campbell L. L., Polyak K., Brisken C., Yang J., and Weinberg R. A. (2008) The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 133, 704–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scheel C., Eaton E. N., Li S. H., Chaffer C. L., Reinhardt F., Kah K. J., Bell G., Guo W., Rubin J., Richardson A. L., and Weinberg R. A. (2011) Paracrine and autocrine signals induce and maintain mesenchymal and stem cell states in the breast. Cell 145, 926–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Plante M., Rubin S. C., Wong G. Y., Federici M. G., Finstad C. L., and Gastl G. A. (1994) Interleukin-6 level in serum and ascites as a prognostic factor in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer 73, 1882–1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zebrowski B. K., Liu W., Ramirez K., Akagi Y., Mills G. B., and Ellis L. M. (1999) Markedly elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in malignant ascites. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 6, 373–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duysinx B. C., Corhay J. L., Hubin L., Nguyen D., Henket M., and Louis R. (2008) Diagnostic value of interleukine-6, transforming growth factor-β 1 and vascular endothelial growth factor in malignant pleural effusions. Respir. Med. 102, 1708–1714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Latifi A., Luwor R. B., Bilandzic M., Nazaretian S., Stenvers K., Pyman J., Zhu H., Thompson E. W., Quinn M. A., Findlay J. K., and Ahmed N. (2012) Isolation and characterization of tumor cells from the ascites of ovarian cancer patients: molecular phenotype of chemoresistant ovarian tumors. PLoS ONE 7, e46858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen S. F., Lin Y. S., Jao S. W., Chang Y. C., Liu C. L., Lin Y. J., and Nieh S. (2013) Pulmonary adenocarcinoma in malignant pleural effusion enriches cancer stem cell properties during metastatic cascade. PLoS ONE 8, e54659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thiery J. P., and Sleeman J. P. (2006) Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 131–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al-Hajj M., Wicha M. S., Benito-Hernandez A., Morrison S. J., and Clarke M. F. (2003) Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 3983–3988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brabletz T., Jung A., Spaderna S., Hlubek F., and Kirchner T. (2005) Opinion: migrating cancer stem cells: an integrated concept of malignant tumour progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 744–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dean M., Fojo T., and Bates S. (2005) Tumour stem cells and drug resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 275–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jewett A., Tseng H. C., Arasteh A., Saadat S., Christensen R. E., and Cacalano N. A. (2012) Natural killer cells preferentially target cancer stem cells: role of monocytes in protection against NK cell mediated lysis of cancer stem cells. Curr. Drug Deliv. 9, 5–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moretta L., and Moretta A. (2004) Unravelling natural killer cell function: triggering and inhibitory human NK receptors. EMBO J. 23, 255–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Larue L., and Bellacosa A. (2005) Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in development and cancer: role of phosphatidylinositol 3′ kinase/AKT pathways. Oncogene 24, 7443–7454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Procaccini C., De Rosa V., Galgani M., Abanni L., Calì G., Porcellini A., Carbone F., Fontana S., Horvath T. L., La Cava A., and Matarese G. (2010) An oscillatory switch in mTOR kinase activity sets regulatory T cell responsiveness. Immunity 33, 929–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Vermeulen L., De Sousa E Melo F., van der Heijden M., Cameron K., de Jong J. H., Borovski T., Tuynman J. B., Todaro M., Merz C., Rodermond H., Sprick M. R., Kemper K., Richel D. J., Stassi G., and Medema J. P. (2010) Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nat. Cell Biol. 12, 468–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu S., Dontu G., Mantle I. D., Patel S., Ahn N. S., Jackson K. W., Suri P., and Wicha M. S. (2006) Hedgehog signaling and Bmi-1 regulate self-renewal of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells. Cancer Res. 66, 6063–6071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lonardo E., Hermann P. C., Mueller M. T., Huber S., Balic A., Miranda-Lorenzo I., Zagorac S., Alcala S., Rodriguez-Arabaolaza I., Ramirez J. C., Torres-Ruíz R., Garcia E., Hidalgo M., Cebrián D. Á., Heuchel R., Löhr M., et al. (2011) Nodal/Activin signaling drives self-renewal and tumorigenicity of pancreatic cancer stem cells and provides a target for combined drug therapy. Cell Stem Cell 9, 433–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lee J. Y., Chang J. W., Yang W. S., Kim S. B., Park S. K., Park J. S., and Lee S. K. (2011) Albumin-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and ER stress are regulated through a common ROS-c-Src kinase-mTOR pathway: effect of imatinib mesylate. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 300, F1214–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sakuma K., Aoki M., and Kannagi R. (2012) Transcription factors c-Myc and CDX2 mediate E-selectin ligand expression in colon cancer cells undergoing EGF/bFGF-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7776–7781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shiota M., Zardan A., Takeuchi A., Kumano M., Beraldi E., Naito S., Zoubeidi A., and Gleave M. E. (2012) Clusterin mediates TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis via Twist1 in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 72, 5261–5272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yang A. D., Camp E. R., Fan F., Shen L., Gray M. J., Liu W., Somcio R., Bauer T. W., Wu Y., Hicklin D. J., and Ellis L. M. (2006) Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 activation mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transition in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 66, 46–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Labelle M., Begum S., and Hynes R. O. (2011) Direct signaling between platelets and cancer cells induces an epithelial-mesenchymal-like transition and promotes metastasis. Cancer Cell 20, 576–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hurwitz H., Fehrenbacher L., Novotny W., Cartwright T., Hainsworth J., Heim W., Berlin J., Baron A., Griffing S., Holmgren E., Ferrara N., Fyfe G., Rogers B., Ross R., and Kabbinavar F. (2004) Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 2335–2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sandler A., Gray R., Perry M. C., Brahmer J., Schiller J. H., Dowlati A., Lilenbaum R., and Johnson D. H. (2006) Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 2542–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sasada T., Kimura M., Yoshida Y., Kanai M., and Takabayashi A. (2003) CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: possible involvement of regulatory T cells in disease progression. Cancer 98, 1089–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abiko K., Mandai M., Hamanishi J., Yoshioka Y., Matsumura N., Baba T., Yamaguchi K., Murakami R., Yamamoto A., Kharma B., Kosaka K., and Konishi I. (2013) PD-L1 on tumor cells is induced in ascites and promotes peritoneal dissemination of ovarian cancer through CTL dysfunction. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 1363–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Raulet D. H., and Guerra N. (2009) Oncogenic stress sensed by the immune system: role of natural killer cell receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 568–580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. López-Novoa J. M., and Nieto M. A. (2009) Inflammation and EMT: an alliance towards organ fibrosis and cancer progression. EMBO Mol. Med. 1, 303–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Okano J., Shiota G., Matsumoto K., Yasui S., Kurimasa A., Hisatome I., Steinberg P., and Murawaki Y. (2003) Hepatocyte growth factor exerts a proliferative effect on oval cells through the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 309, 298–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Abid M. R., Guo S., Minami T., Spokes K. C., Ueki K., Skurk C., Walsh K., and Aird W. C. (2004) Vascular endothelial growth factor activates PI3K/Akt/forkhead signaling in endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 294–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rafehi S., Ramos Valdes Y., Bertrand M., McGee J., Préfontaine M., Sugimoto A., DiMattia G. E., and Shepherd T. G. (2016) TGFβ signaling regulates epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in ovarian cancer ascites-derived spheroids. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 23, 147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nakamura K., Martin K. C., Jackson J. K., Beppu K., Woo C. W., and Thiele C. J. (2006) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of TrkB induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression via hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in neuroblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 66, 4249–4255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kobold S., Hegewisch-Becker S., Oechsle K., Jordan K., Bokemeyer C., and Atanackovic D. (2009) Intraperitoneal VEGF inhibition using bevacizumab: a potential approach for the symptomatic treatment of malignant ascites? Oncologist 14, 1242–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Du N., Li X., Li F., Zhao H., Fan Z., Ma J., Fu Y., and Kang H. (2013) Intrapleural combination therapy with bevacizumab and cisplatin for non-small cell lung cancer-mediated malignant pleural effusion. Oncol. Rep. 29, 2332–2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhao H., Li X., Chen D., Cai J., Fu Y., Kang H., Gao J., Gao K., and Du N. (2015) Intraperitoneal administration of cisplatin plus bevacizumab for the management of malignant ascites in ovarian epithelial cancer: results of a phase III clinical trial. Med. Oncol. 32, 292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dvorak H. F. (2002) Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: a critical cytokine in tumor angiogenesis and a potential target for diagnosis and therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 20, 4368–4380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.